Abstract

Large language models (LLMs) show promise for clinical decision support but often struggle with case-specific reasoning. We present Ophtimus-V2-Tx, an 8-billion-parameter ophthalmology-specialized LLM fine-tuned on more than 10,000 case reports. Evaluation is conducted on a pre-collected dataset. Alongside text metrics (ROUGE-L, BLEU, METEOR) and a semantic similarity score, we use CliBench to map outputs to standardized codes (ICD-10-CM, ATC, ICD-10-PCS) and compute hierarchical F1 (L1–L4 and Full), with code mapping used strictly as an evaluation tool. Ophtimus-V2-Tx is competitive with a state-of-the-art general model and stronger in several settings. It improves text metrics (ROUGE-L 0.40 vs. 0.18; BLEU 0.26 vs. 0.05; METEOR 0.45 vs. 0.29) with comparable semantic similarity. On CliBench, it attains a higher full-code score for secondary diagnosis and ties or leads at selected granular levels for primary diagnosis, while medication and procedure results are close with overlapping confidence intervals. Relative to other ophthalmology-tuned baselines, it shows consistently higher text-generation scores. These findings indicate that a compact, domain-adapted model can approach-or in targeted settings, exceed-large general LLMs on clinically grounded outputs while remaining feasible for on-premise use. We also describe an auditable evaluation pipeline (frozen coding agent, identical prompts, hierarchical metrics) to support reproducibility and future benchmarking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Large language models (LLMs) show promise for diagnosis support, treatment planning, and patient communication1,2,3, but moving from general explanation to patient-specific reasoning is hard. Clinical use demands precise interpretation, consistent specialty terminology, and outputs aligned to standardized taxonomies. This is especially acute in ophthalmology, where laterality, quantitative measures, named exams, and longitudinal follow-up are central.

Small, domain-specific LM (small language model; SLM)-used interchangeably here with “compact LLM” to denote resource-efficient smaller models, whereas LLM denotes the general class of large language models-offer a practical path forward: they run on-premise with lower latency and cost while keeping data on site for privacy and compliance; and, with case-based fine-tuning, they more readily internalize fine-grained knowledge (terminology, laterality, code schemas) and support tighter output governance (guardrails, selective abstention, calibration). In practice, SLMs help bridge linguistic fluency to clinically reliable, code-aligned reasoning and improve workflow fit and deployability.

Ophthalmology exemplifies these demands. Clinicians must reason over domain-specific constructs such as laterality, quantitative measurements, named examinations, and longitudinal follow-up, and they must map conclusions to interoperable code systems used for reporting and downstream workflows. General-purpose LLMs, often trained on broad biomedical or encyclopedic text, may be fluent yet insufficiently grounded for these context-sensitive tasks.

To address these gaps, we introduce Ophtimus-V2-Tx, a compact, domain-specialized ophthalmology model adapted from a modern 8B-parameter foundation model4 via parameter-efficient fine-tuning. Rather than relying on loosely structured narratives, we fine-tune on schema-structured case reports that capture end-to-end clinical workflows-presentation, examinations, diagnostic interpretation, therapeutic decisions, and follow-up-preserving details such as laterality and quantitative values. This case-based approach aims to couple clinical specificity with computational efficiency suitable for on-premise settings.

We evaluate model outputs as clinicians would consume them: free-text rationales are mapped to standardized code systems (ICD-10-CM for diagnoses, ATC for medications, ICD-10-PCS for procedures) and scored hierarchically to reflect both exact matches and clinically proximate near-misses. In parallel, we assess the narrative alignment of the free-text itself using complementary text metrics (e.g., ROUGE-L, BLEU, METEOR) and a semantic-similarity measure. This dual perspective highlights cases where clinical reasoning is consistent even when exact codes differ, and provides a more complete picture of output quality beyond strict code identity. For fairness and reproducibility, the same frozen coding agent and prompt are applied to both reference labels and predictions, with deterministic normalization and clearly specified mapping rules.

In comparative studies, Ophtimus-V2-Tx is competitive with leading general-purpose models on clinically grounded outputs and shows advantages in targeted settings, while improving over prior ophthalmology-tuned baselines on narrative measures and structured reasoning. Taken together, these results point to a practical path for compact, domain-adapted models that combine clinical specificity with deployability.

Contributions

-

A case-report–based fine-tuning strategy that strengthens clinical specificity and preserves ophthalmology-relevant structure (e.g., laterality, measurements, named tests).

-

Ophtimus-V2-Tx, a compact ophthalmology model designed for realistic decision-support use and efficient on-premise operation.

-

A hierarchical, code-aligned evaluation spanning diagnoses, medications, and procedures, complemented by free-text similarity assessment to capture narrative alignment.

-

A reproducible and resource-efficient pipeline, including an auditable mapping procedure, intended to lower the barrier to safe, site-ready deployment and future benchmarking5,6.

Results

Comparative evaluation strategy

To rigorously assess the clinical utility of our proposed model, Ophtimus-V2-Tx, we conduct a multi-dimensional comparative evaluation against the following baseline models (Table 1):

Three of the models in this comparison-Ophtimus-V1-Inst6, Ophtimus-V2-Inst, and Ophtimus-V2-Tx-are our custom instruction-tuned models. Among them, Ophtimus-V2-Inst and Ophtimus-V2-Tx were both developed based on a common pretrained foundation: the Ophtimus-V2-Base7 model, with details of its pretraining corpus provided in the “Methods” section. (Removed redundant sentence: “which was pretrained on a large-scale ophthalmology corpus composed of domain-specific textbooks (4M) and PubMed ophthalmology articles (18.4M).”) These two models were then fine-tuned for different tasks. The Ophtimus-V2-Inst model was fine-tuned primarily on multiple-choice question answering (MCQA) and essay-style QA datasets, with a focus on clinical reasoning and medical knowledge comprehension. It retained a strong alignment with structured, educational-style questions commonly seen in medical board exams. In contrast, the Ophtimus-V2-Tx model extended the same base foundation through additional fine-tuning that combined the original instruction datasets with real-world clinical case reports, specifically curated to emphasize treatment planning, therapeutic decision-making, and post-treatment follow-up guidance. By incorporating case-based narratives into the fine-tuning data, Ophtimus-V2-Tx was optimized not only for diagnostic reasoning but also for generating contextually appropriate management plans grounded in ophthalmology practice.

The evaluation focuses on four key dimensions: (1) general performance on multiple-choice questions, (2) clinical accuracy based on text similarity, (3) clinical accuracy using the CliBench framework, and (4) keyword-specific MCQA accuracy. First, we conduct a general performance comparison using a medical multiple-choice question answering (MCQA) dataset that includes diagnostic, treatment, and procedural questions. This baseline comparison helps assess the models’ general reasoning capabilities under structured question formats. Second, we perform a text similarity evaluation to assess the linguistic alignment between model-generated outputs and human-written references. This includes the use of ROUGE-L, BLEU, METEOR, and SEMSCORE metrics8,9,10,11, which measure surface-level and semantic correspondence across generated sentences. Third, we adopt the CliBench framework to perform fine-grained, task-specific evaluation across three clinical dimensions: semantic similarity to ground-truth sentences, diagnostic classification accuracy, and treatment decision accuracy. CliBench is a clinically grounded benchmark that maps model outputs to standardized medical code systems (ICD-10-CM, ATC, ICD-10-PCS) and evaluates performance across multiple hierarchy levels (L1–L4 and Full code match). This enables hierarchical F1 score computation for each clinical task.

-

Diagnostic Accuracy: Model-generated primary and secondary diagnoses are automatically mapped to ICD-10-CM codes and evaluated using hierarchical F1 scores.

-

Treatment Accuracy: Medications are mapped to ATC codes and surgical procedures to ICD-10-PCS codes. Accuracy is again measured by hierarchical F1 scores, highlighting the model’s ability to generate valid therapeutic outputs.

This CliBench-based evaluation is the core of our analysis, as it directly measures the clinical validity of model-generated diagnoses and treatment plans using medically structured standards. It complements surface-level metrics by evaluating whether the outputs are clinically appropriate within a structured reasoning framework.

Finally, we analyze MCQA performance at the keyword level. Clinical topics such as macular degeneration, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy are used to cluster questions and compute model-wise accuracy within each topic. This allows us to identify domain-specific strengths and weaknesses and highlights the subfields where Ophtimus-V2-Tx provides the most substantial improvement.

Qualitative comparison of clinical outputs across models in case-based scenarios

Table 2 presents a comparative evaluation of diagnostic and treatment suggestions generated by GPT-4o, Ophtimus-V2-Inst, and Ophtimus-V2-Tx for four real-world ophthalmic cases. While GPT-4o and Ophtimus-V2-Inst generally provided partially correct or broad responses, Ophtimus-V2-Tx consistently produced more specific and clinically accurate outputs aligned with expert ground truth. These results underscore the effectiveness of case-based fine-tuning in enhancing complex treatment reasoning capabilities.

Sentence similarity analysis

Table 3 presents the performance comparison across four widely used automatic evaluation metrics for language generation: ROUGE-L, BLEU, METEOR, and SEMSCORE. Each metric captures a distinct aspect of text quality, providing a comprehensive view of model performance.

ROUGE-L measures the longest common subsequence between the generated and reference sentences, focusing on structural similarity and content overlap. BLEU evaluates precision over short n-grams, reflecting how accurately the generated output reproduces the lexical content of the reference. METEOR, in contrast, incorporates stemming and synonym matching to account for semantically equivalent expressions even when exact wording differs. Lastly, SEMSCORE leverages pre-trained sentence embedding models (e.g., SBERT) to compute semantic similarity, emphasizing the overall meaning conveyed rather than exact word usage.

Across aggregated generation metrics with 95% confidence intervals (Table 3), Ophtimus-V2-Tx exceeds OpenAI GPT-4o on ROUGE-L (0.40 [0.40, 0.41] vs. 0.18 [0.17, 0.18]), BLEU (0.26 [0.26, 0.27] vs. 0.05 [0.05, 0.05]), and METEOR (0.45 [0.45, 0.46] vs. 0.29 [0.29, 0.29]); the 95% CIs are non-overlapping, indicating robust improvements in structural and lexical alignment under our bootstrap protocol.

For SEMSCORE, OpenAI GPT-4o attains a slightly higher estimate (0.82 [0.81, 0.82]) than Ophtimus-V2-Tx (0.80 [0.80, 0.81]); because the 95% CIs overlap at 0.81, we characterize semantic similarity as comparable rather than conclusively different.

Taken together, these results suggest that domain-specific pretraining and targeted instruction tuning in Ophtimus-V2-Tx yield substantial gains in structural/lexical fidelity while maintaining high semantic adequacy. In line with best practice, we report effect directions alongside uncertainty quantification rather than blanket superiority claims.

Diagnosis analysis

Table 4 summarizes the hierarchical F1 scores for all CLIBENCH tasks—Primary and Secondary Diagnosis, Medication, andSurgical Procedure—along with their 95 percent confidence intervals. For each task, the best-performing scores at each hierarchicallevel (L1 to Full) are highlighted in bold.

Primary diagnosis results

Ophtimus-V2-Tx (8B) attains the best L2 score (0.58) and ties for the best L4 score (0.40). At L3 it is essentially on par with OpenAI API (0.51 vs. 0.52), while at Full it reaches 0.23 versus OpenAI’s 0.26. Overall, Tx shows strength at mid/fine levels (L2/L4) in terms of structural understanding and code concordance; most gaps fall within overlapping 95% CIs, underscoring its competitiveness despite the 8B parameter scale.

Secondary diagnosis results

Ophtimus-V2-Tx achieves the best Full (exact code) score (0.15) and ties for the best L4 (0.17) (cf. OpenAI Full 0.12, L4 0.17). OpenAI leads at L1–L3, but Tx is strongest in fine-grained, code-level alignment. Because clinical workflows such as billing, registry curation, and downstream decision support often require exact-code agreement, this pattern is practically meaningful.

Contributions and implications of Ophtimus-V2-Tx (8B)

In sum, the domain-tuned 8B Ophtimus-V2-Tx competes directly with a large proprietary system and shows consistent advantages at fine-grained levels (L4) and Full-metrics that matter in clinical use. We attribute this to (i) a schema-first (case-structured) input that preserves quantitative values, laterality (OD/OS/OU), test names (OCT/FA/OCTA), and explicit findings, and (ii) source-level evaluation in which reference labels from the original texts are normalized to ICD-10-CM for comparison. Moreover, the parameter efficiency (8B) enables on-premise/edge deployment and lower inference cost, supporting immediate workflows such as diagnosis code suggestion/verification, case-based differential diagnosis candidates, and documentation/registry quality control.

In addition to reporting confidence intervals for each model, we also examined confidence intervals for the pairwise differences in accuracy and F1 scores using bootstrap resampling across all evaluation tasks. This provides a conservative statistical test: if the 95% CI of the difference excludes zero, the performance gap can be considered statistically significant.

Treatment result analysis

CliBench imposes exact ICD-10-CM/ATC/ICD-10-PCS matching from free text, which is stricter than MCQA and can understate clinically reasonable outputs that miss a specific leaf code. To contextualize absolute scores, we additionally report hierarchical proximity (L1–L4 vs. Full) and text-level semantic similarity (e.g., ROUGE-L, BLEU, METEOR/semantic score). These complementary views decouple clinical alignment from exact-code identity and show that many errors are near-misses rather than clinically irrelevant.

On CliBench, treatments were evaluated as Medication (ATC) and Surgical Procedure (ICD-10-PCS) using hierarchical F1 at L1–L4 and Full (exact code), with 95% CIs reported.

Medication

OpenAI leads across levels, while Ophtimus-V2-Tx (8B) narrows the gap at fine granularity: at Full it reaches 0.31 versus OpenAI’s 0.32 with overlapping CIs, indicating practically comparable exact-code concordance despite the parameter gap.

Surgical procedure

The two models tie at L1 (0.75 each), showing similar recognition of broad procedure classes. OpenAI is stronger at L2–L3, but Full converges (0.13 for Tx vs. 0.16 for OpenAI; overlapping CIs), suggesting proximity at the exact-code level.

Implications

These results show that an 8B, schema-first model can deliver near state-of-the-art exact-code performance for medication and competitive surgical coding at the coarse level, supporting first-pass code suggestion/verification and treatment-option drafting with lower compute cost and on-prem/edge deployability.

Contributions and implications of Ophtimus-V2-Tx (8B)

As a compact, ophthalmology-tuned 8B model, Ophtimus-V2-Tx competes with much larger systems, with its strongest gains at deep taxonomy tiers and exact-code agreement. An evidence-anchored case template coupled with code-normalized evaluation yields auditable, easily integrated outputs and strong accuracy-per-compute. This enables on-prem/edge use for first-pass coding, differential candidate lists, and documentation QA. The shared schema/codebooks extend to treatment tasks and other subspecialties, providing a practical route to scalable, privacy-preserving clinical LLMs.

Benchmark-based performance comparison

Evaluation datasets

To evaluate and compare the performance of Ophtimus-V2-Tx against other medical language models, we employed three datasets, each representing different evaluation dimensions: domain-specific expertise, professional-level QA robustness, and literature-based inference (Table 5).

-

Ophtimus-Eval-V15: This dataset was independently constructed to benchmark ophthalmology-specific MCQA performance. All questions were curated from public educational resources and reviewed by medical experts to ensure quality. Notably, it allows topic-wise performance analysis across 19 ophthalmic subfields. Access is currently restricted to protect clinical validation integrity.

-

MedMCQA (Ophthalmology Subset)12: Extracted from a national medical exam dataset (NEET-PG), this subset contains thousands of ophthalmology-focused questions. It serves to test the transferability of general medical QA models to the ophthalmology domain and includes expert-reviewed explanations for some questions.

-

PubMedQA (Ophthalmology Subset)13: This subset targets biomedical inference by linking questions to PubMed abstracts with Yes/No/Maybe labels. Although limited in size, it evaluates a model’s ability to reason over real-world biomedical literature in ophthalmology.

General performance analysis

Table 6 shows the overall classification accuracy of each model across three multiple-choice question answering (MCQA) datasets: Ophtimus-Eval-V1 (ophthalmology-specific), MedMCQA (medical licensing-style questions), and PubMedQA (biomedical research questions).

Compared to other baselines, Ophtimus-V2-Inst achieved strong performance on Ophtimus-Eval-V1 (0.63) and competitive results on MedMCQA (0.71) and PubMedQA (0.72), showing a balanced understanding across domain-specific, clinical, and general biomedical contexts. Interestingly, Ophtimus-V2-Tx exhibited a distinctive pattern: while it showed lower accuracy on Ophtimus-Eval-V1 (0.43) and MedMCQA (0.53)-likely due to its focus on generative treatment tasks rather than QA fine-tuning-this trade-off will be further discussed in a later section.

On PubMedQA, Ophtimus-V2-Tx achieved an accuracy of 0.88, which is competitive with OpenAI GPT-4o (0.91) and higher than all other compared models. Given the relatively small sample size of the ophthalmology subset of PubMedQA (\(N=297\)), these results should be interpreted with caution. To reflect this uncertainty, we also report 95% confidence intervals and confusion matrices in Fig. 7. In contrast, many general-purpose LLMs such as LLaMA 3-8B Instruct and PMC-LLaMA-13B showed inconsistent or modest performance across the three benchmarks. OpenAI GPT-4o demonstrated the highest overall robustness but was still outperformed by Ophtimus-V2-Tx on PubMedQA. However, given that the ophthalmology-specific subset of PubMedQA is relatively small in size, further validation is needed to confirm the consistency of these results. Overall, these results illustrate the trade-offs between task specialization and QA generalization. The two instruction-tuned variants of Ophtimus-V2 exhibit complementary strengths: Ophtimus-V2-Inst excels in domain-specific and clinically structured MCQA, while Ophtimus-V2-Tx shows remarkable generalization to biomedical inference tasks despite limited MCQA fine-tuning.

Figure 1 shows the token distribution used in fine-tuning Ophtimus-V2-Tx, revealing that 29.1% of its training data was derived from ophthalmology case reports. In contrast, Ophtimus-V2-Inst was trained exclusively on QA-formatted data from PubMed and textbook sources. Despite sharing the same base model, fine-tuning objective, and loss function, Ophtimus-V2-Tx showed a notable drop in MCQA performance (e.g., 0.43 on Ophtimus-Eval-V1), likely due to a reduced proportion of QA-specific signals. The inclusion of narrative-style clinical cases may have diluted the model’s QA alignment, underscoring the trade-off between generalization to treatment reasoning and specialization in structured QA tasks.

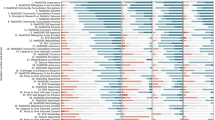

Topic-wise performance analysis

Figure 2 presents a comparative analysis of multiple-choice question answering (MCQA) accuracy across 20 ophthalmic subtopics. The number of questions per topic is indicated in parentheses, providing context for interpreting model performance. For this analysis, we used only the Ophtimus-Eval dataset, since it is the only benchmark among the three (Ophtimus-Eval, MedMCQA, PubMedQA) that provides explicit categorization by ophthalmic keywords (e.g., Uveitis, Glaucoma, AMD). This allowed us to assess performance variation across clinical subdomains. PubMedQA and MedMCQA lack topic-level annotations, and thus were not suitable for topic-wise comparison.

Overall, OpenAI GPT-4o demonstrated consistently strong performance across most topics, showing particularly high accuracy in general areas such as General Ophthalmology (986), Pharmacology (40), and Conjunctiva (21). However, it did not always achieve the top score, as certain specialized ophthalmic topics were better handled by the Ophtimus series models. Ophtimus-V2-Inst, trained on MCQA and essay-style reasoning questions, achieved competitive or even superior accuracy in domains such as Neuro-Ophthalmology (165), Ocular Trauma (28), and Systemic Diseases (8). Especially in Neuro-Ophthalmology, which requires reasoning across neurology and ophthalmology, the model showed strong task-specific inference capabilities. Interestingly, although Ophtimus-V2-Tx was fine-tuned for treatment planning and follow-up generation, it exhibited high accuracy in clinically reasoning-intensive domains such as Uveitis (40), Retina and Vitreous (13), and Oculoplastic (11).

We note, however, that this topic-wise result is presented as an exploratory observation rather than a definitive benchmark of complexity. Given the small sample size (N = 40) and the wide confidence interval, these findings should be interpreted with caution, serving only to illustrate potential trade-offs introduced by case-report fine-tuning.

Uveitis is a complex inflammatory condition with diverse etiologies that demands high-level clinical reasoning and differential diagnosis skills14. This suggests that the case-based learning approach used to train the Tx model effectively enhanced its domain understanding and therapeutic decision-making capabilities. In summary, GPT-4o achieved the highest overall average performance, but Ophtimus-V2-Inst proved to be a competitive domain-specialized model for medical QA, and Ophtimus-V2-Tx demonstrated strengths in clinically complex topics that require fine-grained therapeutic reasoning. These results highlight the complementary roles of general-purpose and task-specific medical language models and offer valuable guidance for model selection and design in clinical applications (Table 7).

Methods

Ophthalmic foundation model: Ophtimus-V2-base

Figure 3 illustrates the overall development pipeline for our ophthalmology-specialized language model. The process consists of four main stages: Source Data Gathering, Text Pre-processing and Pre-training, Instruction-based Fine-Tuning, and Evaluation.

In the source data collection stage, we restricted retrieval to the PubMed Central (PMC) Open Access subset and the English language, applying article-type filters to include case reports and closely related clinical report categories. Using ophthalmology-specific Boolean/MeSH queries—25 for the Base pretraining corpus and 29 for the case-report corpus (exact query lists, field tags, and access dates in Table 9 and the Supplement)—we retrieved candidate records. We then performed document-level deduplication using PMCID, removed near-duplicates, and conservatively removed any personally identifiable information (PII). Aggregating across sources yielded approximately 18.4M tokens from PMC and about 4.0M tokens from domain-specific textbooks (e.g.,15,16,17,18,19,20,21). Across the textbook subset used for pretraining, we count 18 volumes and 7962 pages in total, corresponding to an average of 442.3 pages per volume. Together these sources form the final Ophthalmology Corpus dataset.

This curated corpus was then used to pre-train a foundation model based on LLaMA 3.1, resulting in the creation of the Ophtimus-V2-Base model. This base model is optimized for general understanding and generation of ophthalmic text, such as clinical descriptions, diagnostic reasoning, and treatment explanations.

In the next stage, we performed instruction tuning to train the model on medical question-answering tasks. We constructed a domain-specific QA dataset using the OpenAI API, focusing on both multiple-choice and essay-style formats that reflect real-world clinical reasoning. Through supervised fine-tuning with LoRA techniques22, we derived the Ophtimus-V2-Inst model, which is tailored to handle complex medical queries and reasoning tasks effectively and efficiently.

Finally, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation using both external benchmarks and our own Ophtimus-Eval-V1 dataset-a carefully curated multiple-choice QA (MCQA) evaluation set based on ophthalmic case scenarios collected from Academia.edu. Ophtimus-Eval-V1 was designed to assess overall accuracy and keyword-specific performance. This allowed us to identify domain-specific strengths, such as performance variations across key ophthalmic topics like macular degeneration, glaucoma, and diabetic retinopathy.

Data Sources and Usage Policy

Domain textbooks (e.g., BCSC, Kanski) used in this work are copyrighted. We employed them exclusively for non-consumptive, research-only text mining to derive structured fields and aggregate statistics. The pretraining textbook subset comprises 18 volumes totaling 7962 pages (mean 442.3 pages per volume). No copyrighted text or images are redistributed; the released artifacts consist only of model weights, code, prompts, schema definitions, and aggregate metrics. For reproducibility, we provide an open-access–only retraining recipe and report ablations demonstrating similar performance trends without copyrighted sources.

Ophthalmic case report dataset construction

Figure 4 illustrates the overall process used to construct the ophthalmology case report dataset for fine-tuning the Ophtimus-V2-Tx model. The process consists of three main stages: Data Crawling, Data Filtering, and Formatting Data for Fine-tuning.

-

(1)

Data crawling

We first collected documents from two major sources: PubMed (PMC Open Access only, English, no date limit) and an ophthalmology case-report textbook. Using ophthalmology-specific keywords/MeSH (25 for Base; 29 for Case Report), we retrieved 10,377 case-report candidates from PubMed (initial retrieval), followed by screening and deduplication. After PMCID-based document-level deduplication and eligibility screening, 8261 articles remained; from these, we structured 10,815 individual patient cases. In parallel, we extracted and grouped case narratives from Clinical Cases in Medical Retina (1st ed.; 74 chapters). This source is copyrighted; materials were used strictly under the publisher’s terms for research-only text mining, and no original text or derivatives were redistributed. To prevent data leakage, textbook-derived content was used only for pretraining/fine-tuning and was excluded from evaluation.

-

(2)

Data filtering

We applied multi-stage filtering with the OpenAI API to both PubMed papers and textbook-based documents.

Before invoking the API, we applied rule-based gates (document type/language/length/keywords) with deduplication and near-duplicate removal. We then used a frozen OpenAI API strictly as a text classifier (no generation), with prompts limited to document-type decisions-we did not solicit subjective “paper relevance.” Prompt templates are provided verbatim in Appendix B.2.

In the first step, the classifier operated on PubMed papers only, checking ophthalmic domain membership, language, and the presence of experimental/control groups.

In the second step, both PubMed papers and textbook documents underwent privacy/irrelevance screening: residual identifiers (names/initials, institution names, contact lines, exact visit dates, addresses, image identifiers) were removed or normalized, while clinical signals (quantitative values, laterality tokens, test names, explicit findings) were preserved; the PHI policy and examples appear in Appendix B.1 and B.2.

Through this two-phase filtering, we selected a final set of 8261 PubMed documents and 74 textbook chapters as usable ophthalmology case-report documents for fine-tuning.

-

(3)

Formatting data for fine-tuning

The filtered documents were converted to a schema-first, programmatic format-not free-form summarization. A rule-based mapper populated a fixed template with two blocks (Patient Information; Diagnosis and Treatment). The OpenAI API was used only as a frozen fallback field router to disambiguate spans (e.g., findings vs. rationale), never to paraphrase or condense; ambiguous cases were flagged for spot-check. The routing prompt is given in Appendix B.3, and the schema in Table 8.

We utilized a total of 10,815 cases (one document may contain multiple patient cases) for training and evaluation. Among these, 9,193 cases were assigned to the training set and 1622 cases to the evaluation set through random splitting. The 76 cases collected from the textbook were included only in the training data. While a single case-report document may contain multiple patient cases-meaning that cases from the same document could be assigned separately to both training and evaluation sets-this does not pose a problem, as each case represents an independent patient.

Fine-tuning strategy

Figure 5 illustrates our fine-tuning strategy for the ophthalmology-specific adaptation of the Ophtimus-V2-Base model. To develop Ophtimus-V2-Tx, a domain-specialized language model tailored for ophthalmology, we began with the pretrained foundation model, Ophtimus-V2-Base (8B parameters), and further refined it using a combination of QA-based datasets and real-world clinical case reports.

To enhance the model’s clinical reasoning capabilities in real-world ophthalmic contexts, we incorporated 9193 structured case reports covering a wide range of ophthalmologic conditions, carefully formatted to capture end-to-end diagnostic workflows (patient presentation, symptom progression, relevant examinations, diagnostic interpretation, treatment decisions, and follow-up considerations). From the final pool of 10,891 structured cases, 9193 were used for fine-tuning, with the remainder allocated to evaluation (1622) or to textbook-based training only (76).

For efficient domain adaptation, we employed Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA), a parameter-efficient fine-tuning method. LoRA introduces lightweight trainable matrices into each transformer layer, enabling specialization to new domains without modifying the entire set of pretrained parameters. This strategy offers computational efficiency while retaining the base model’s general medical knowledge. The integration of general-domain QA data with LoRA-based fine-tuning on case report data resulted in the final model, Ophtimus-V2-Tx. Trained on a total of 95,157 QA and case examples, this model combines broad medical understanding with precise clinical reasoning abilities for ophthalmology-specific tasks.

Training setup

We fine-tuned Ophtimus-V2-Tx from Ophtimus-V2-Base using parameter-efficient Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) without applying quantization. The configuration was as follows:

-

LoRA: \(r=32\), \(\alpha =16\), dropout \(=0.05\); target_modules = {q_proj, v_proj, k_proj, o_proj, gate_proj, up_proj, down_proj}.

-

Optimizer and LR schedule: AdamW optimizer; learning rate = \(2{\times }10^{-4}\); weight decay = 0.01; warmup steps = 10; constant-with-warmup scheduler.

-

Batching: per-device train batch size = 8; gradient accumulation = 8; effective batch size across 3 GPUs = 192.

-

Training duration and hardware: 25 epochs on 3×NVIDIA A100 80GB GPUs, total training time 3 days.

-

Sequence length: maximum context length = 4096 tokens.

-

Evaluation/save: eval strategy = steps (every 25 steps), save strategy = epoch, logging steps = 1, seed = 42.

Inference settings

Unless otherwise noted, decoding used a maximum context of 4096 tokens and generation length up to 512 tokens, with temperature 0.7 and top-p 0.9. Greedy sampling was not used; no beam search was applied. We fix these parameters across evaluations to ensure comparability.

Scoring criteria

To quantitatively assess the quality of diagnosis and treatment sentence generation by Ophtimus-V2-Tx and baseline models, we employed four representative natural language generation (NLG) evaluation metrics: ROUGE-L, BLEU, METEOR, and SEMSCORE. These metrics jointly evaluate not only lexical overlap but also sentence structure, syntactic coherence, and semantic similarity-an essential consideration in clinical settings where the accurate and consistent conveyance of information directly influences patient care.

Confidence intervals For all key metrics (accuracy, F1, precision, recall), we report 95% confidence intervals estimated via a cheap subsampling bootstrap (m = 0.6N, B = 100 resamples)23.

-

ROUGE-L (Longest Common Subsequence). ROUGE-L evaluates structural similarity between the generated sentence C and the reference sentence R based on the length of their longest common subsequence (LCS). It reflects both the precision (how much of C matches R) and the recall (how much of R is preserved in C), using an F-score formulation:

$$\text {ROUGE-L} = \frac{(1 + \beta ^2) \cdot \text {LCS}\_\text {precision} \cdot \text {LCS}\_\text {recall}}{\text {LCS}\_\text {precision} + \beta ^2 \cdot \text {LCS}\_\text {recall}}$$where:

$$\text {LCS}\_\text {precision} = \frac{\text {LCS}(C, R)}{|C|}, \quad \text {LCS}\_\text {recall} = \frac{\text {LCS}(C, R)}{|R|}$$\(\beta\) is typically set to 1.2 to favor recall.

-

BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy). BLEU measures the precision of n-gram matches between the candidate and the reference sentences, with a brevity penalty to discourage overly short outputs. The overall score is computed as:

$$\text {BLEU} = \text {BP} \cdot \exp \left( \sum _{n=1}^N w_n \cdot \log p_n \right)$$where \(p_n\) is the modified n-gram precision, \(w_n\) is the weight for each n-gram (commonly \(w_n = \frac{1}{N}\)), and BP is the brevity penalty:

$$\text {BP} = {\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} 1, & \text {if } c > r \\ \exp \left( 1 - \frac{r}{c}\right) , & \text {if } c \le r \end{array}\right. }$$with c and r representing the lengths of the candidate and reference sentences, respectively.

-

METEOR (Metric for Evaluation of Translation with Explicit ORdering). METEOR addresses BLEU’s limitations by incorporating both unigram precision and recall, while also accounting for stemming, synonym matching, and word order alignment. The metric computes a harmonic mean (\(F_{mean}\)) and applies a penalty based on fragmentation:

$$\text {METEOR} = F_{mean} \cdot (1 - Penalty)$$where:

$$F_{mean} = \frac{10 \cdot P \cdot R}{R + 9P}, \quad Penalty = \gamma \cdot \left( \frac{ch}{m} \right) ^\theta$$Here, P and R are unigram precision and recall, ch is the number of matched chunks, m is the number of matches, and \(\gamma\), \(\theta\) are penalty parameters (e.g., \(\gamma = 0.5\), \(\theta = 3\)).

-

SEMSCORE (Sentence Embedding Similarity Score). SEMSCORE evaluates semantic similarity by computing the cosine similarity between dense sentence embeddings, such as those produced by Sentence-BERT:

$$\text {SEMSCORE}(C, R) = \cos (\textbf{e}_C, \textbf{e}_R) = \frac{\textbf{e}_C \cdot \textbf{e}_R}{\Vert \textbf{e}_C\Vert \cdot \Vert \textbf{e}_R\Vert }$$where \(\textbf{e}_C\) and \(\textbf{e}_R\) denote the embedding vectors of the candidate and reference sentences. This allows the metric to capture meaning equivalence even in the absence of direct lexical overlap.

Evaluation framework: CliBench

In this study, we adopted a structured evaluation framework based on the CliBench benchmark to quantitatively assess the clinical quality of diagnostic and treatment sentences generated by large language models24. CliBench goes beyond simple question–answering tasks by replicating the complex decision-making processes required in real-world clinical settings. It encompasses a diverse range of medical tasks-such as diagnosis, procedures, laboratory testing, and medication prescriptions—each of which is mapped to standardized medical code systems (ICD-10-CM, ICD-10-PCS, LOINC, ATC). This enables model-generated outputs to be evaluated in terms of their clinical fidelity at the level of medical coding granularity.

A core feature of CliBench is its use of hierarchical taxonomies within medical code systems. Diagnostic outputs are evaluated across progressively finer-grained levels of specificity, from broad disease categories (L1), to subgroups (L2–L4), and finally to full-code matches. Similarly, medication and surgical procedure outputs are scored based on the structured hierarchies of the ATC and ICD-10-PCS systems, respectively. This multi-level evaluation scheme enables fine-grained assessment of both the model’s clinical reasoning capabilities and its ability to generate terminology that aligns with standardized classification systems.

Table 10 presents an example of hierarchical medical coding applied to a clinical case involving diagnosis, medication, and surgical procedure. Each entry is mapped to standardized medical codes—ICD-10-CM for diagnosis, ATC for medication, and ICD-10-PCS for surgical procedure. The table also illustrates the hierarchical structure of each code across four levels (L1–L4), enabling fine-grained clinical evaluation.

As an illustrative example, the diagnosis Ophthalmomyiasis externa—a parasitic infestation of the external eye by fly larvae—is mapped to the ICD-10-CM code B87.81. This code belongs to a hierarchical classification system that allows for multi-level evaluation, as shown below:

-

L1-B: Infectious diseases

-

L2-87: Myiasis (infestation by fly larvae)

-

L3-8: Other myiasis

-

L4-1: External ocular involvement

This layered structure enables hierarchical evaluation of model-generated diagnoses. Even when the model fails to produce an exact full-code match, partial matches at higher levels (e.g., L1 or L2) still indicate meaningful clinical relevance. Such stratified evaluation is crucial in measuring not only exact correctness but also partial reasoning alignment

To apply the CliBench framework to the ophthalmology domain, we constructed an evaluation dataset based on 1622 ophthalmic case reports that were not used during model training. For each case, the Ophtimus-V2-Tx model was prompted to generate four types of responses: primary diagnosis, secondary diagnosis, medication, and surgical procedure. The generated sentences were automatically mapped to corresponding standardized medical codes using the Perplexity: ICD-10-CM for diagnoses, ATC for medications, and ICD-10-PCS for surgical procedures.

Ground-truth and evaluation (code-to-code)

From the curated set (10,891 cases = 10,815 PubMed + 76 textbook), we fine-tune on 9269 cases (9193 PubMed + 76 textbook) and hold out 1622 PubMed cases for evaluation. We extract atomic Diagnosis/Treatment sentences from the held-out cases with PHI masked and obtain reference labels by mapping them via a frozen coding agent to ICD-10-CM, ATC, and ICD-10-PCS. No clinician adjudication or generative rewriting is used; ambiguous mappings are spot-checked. For assessment, the same structured context is given to each LLM; model outputs are recoded by the same agent with an identical prompt to produce predicted codes. We compute precision, recall, and F1 at the code level with hierarchical scoring (L1–L4, Full), optimal matching for multi-code sets, and penalties for omissions/overcoding. This code-to-code design quantifies clinical fidelity, improves fairness with a single coder/prompt, and preserves privacy via PHI masking and standardized mapping (see Fig. 6).

Code Mapper analysis

Using code datasets (ATC: \(n=1000\); ICD-10-CM: \(n=198\); ICD-10-PCS: \(n=802\)) from Refs. 25 and 26, we compare four mappers-OpenAI, Claude, Gemini, and Perplexity-across the three systems. We report a composite Bias score (lower is better) built from abstention rate, error distance, close-miss rate, and system-specific under-specificity; accuracy is deliberately excluded (Table 18). The meta ranking is OpenAI (0.372) < Gemini (0.446) < Claude (0.479) < Perplexity (0.615) (Table 19). By system: ATC-Perplexity attains the lowest bias but shows the largest error distance when wrong; OpenAI exhibits higher abstention and close-miss. ICD-10-CM-OpenAI has the lowest bias (very low abstention, high specificity), while Perplexity is penalized by high abstention. ICD-10-PCS-Gemini achieves the lowest bias; Claude abstains least but has higher close-miss; Perplexity ranks worst due to abstention despite relatively low error distance. We did not use GPT-4o (or any LLM) to map or adjudicate predictions; each mapper’s raw code output was evaluated via deterministic normalization (upper-casing, dot/space removal), with ‘X’ treated as abstention. Prompts and post-processing were identical across mappers.

Because our operational goal is fine-grained correctness, L4-level accuracy favors Perplexity across systems (Table 20). We therefore adopt Perplexity as the default mapper and plan rule-based guardrails (triggers: abstention “X”, ATC “Other” L3/L4 = ‘X’, CM .9 unspecified, PCS Device/Qualifier = ‘Z’) with cross-checks using Gemini/Claude/OpenAI when triggered. See Appendix C.1 for details.

Inter-mapper agreement (Fleiss’/Cohen’s \(\kappa\)) was computed as an exploratory diagnostic and not used for scoring, ranking, or model selection (see Appendix C.1): Inter-mapper agreement is near-perfect for ATC at L2 (Fleiss’ \(\kappa =0.912\)) and moderate for ICD-10-CM/PCS (\(\kappa \approx 0.55\)) despite large label spaces, indicating consensus beyond chance. Pairwise \(\kappa\) shows the strongest concordance along the Claude–Perplexity axis (CM/PCS \(\kappa \approx 0.74\)), with Gemini–Perplexity and Claude–Gemini also strong; OpenAI agrees less in CM/PCS. See Appendix C.1 for full pairwise/Fleiss’ \(\kappa\) tables, methods, and caveats.

Discussion

Impact of case-based fine-tuning

As evidenced by the performance of Ophtimus-V2-Tx in Tables 3 and 4, case-based fine-tuning improves, on selected tasks under our evaluated setting, the clinical reasoning capacity of domain-specific language models by aligning outputs with real-world medical workflows. This approach outperformed GPT-4o and instruction-tuned baselines on specific structured tasks (e.g., surgical procedure generation and full-code diagnosis classification), with modest absolute gains in several categories. Performance was also comparable on the medication task. Improvements in sentence similarity and higher full-code accuracy on selected tasks, despite the comparatively small model size, suggest that fine-tuning on authentic clinical case reports can capture nuanced decision-making often missed by QA-only training. However, specialization introduces trade-offs: Ophtimus-V2-Tx showed reduced performance on MCQA-style benchmarks, indicating a potential dilution of structured QA capabilities-a limitation we attribute to domain specialization and model capacity rather than universal superiority, as discussed below.

Previous ophthalmology-specific LLMs-Optha-LLaMA2, EyeGPT, and LEME-show early progress but remain limited in scope. Optha-LLaMA2 focuses on MCQA-style benchmarks and demonstrates strong exam performance yet does not address real-world case-based reasoning. EyeGPT extends GPT architectures to ophthalmology QA tasks with broad coverage but lacks validation for treatment planning or structured code-based evaluation. LEME, an open-source model, provides domain alignment but omits standardized diagnostic/therapeutic coding. In contrast, Ophtimus-V2-Tx is, to our knowledge, the first ophthalmology-specific model fine-tuned on over 10,000 structured case reports and evaluated with the CliBench framework, helping bridge educational QA-style benchmarks and real-world clinical reasoning with code-aligned outputs.

Strengths and limitations of compact LLMs

The performance of Ophtimus-V2-Tx, built on a LLaMA-3.1 8B base model, achieves competitive results on our benchmarks when carefully fine-tuned for the target domain. This has implications for computational efficiency and deployment in resource-constrained, privacy-critical settings (e.g., hospitals). Despite smaller size, Ophtimus-V2-Tx matched-and in some cases exceeded-GPT-4o on selected structured tasks (medication/procedure full-code predictions); differences should be interpreted cautiously where absolute gains are modest. LoRA-based tuning enabled efficient adaptation without full model retraining.

That said, compact design imposes limitations in general-purpose reasoning, transfer, and language coverage. Compared with GPT-4o, Ophtimus-V2-Tx underperformed on general QA datasets such as MedMCQA and exhibited topic-specific variance across ophthalmic subfields (cf. Fig. 2). These patterns likely reflect distributional shifts in training tokens (Fig. 1) and limited capacity of smaller models. Overall, compact models are well-suited for targeted applications, but dataset design and training strategy should balance domain specialization with broader reasoning. A practical route is ensemble- or agent-based designs wherein several compact, sub-domain-specialized models collaborate to capture both specificity and generalization.

Data validation limitations

Although our preprocessing pipeline employed a fixed schema to preserve clinical details verbatim, we recognize that complete validation of textual fidelity across the full corpus remains a limitation of this study. The OpenAI API used in routing was strictly operated as a frozen, non-generative classifier intended only to disambiguate schema boundaries (e.g., findings vs. rationale) without rephrasing. Nevertheless, because this process still depends on LLM-based routing, there remains a possibility of minimal abstraction or paraphrasing that was not exhaustively ruled out. To partially assess fidelity, a subset of structured case reports underwent qualitative review by ophthalmologists. However, due to the scale of data, a systematic corpus-wide audit could not be performed, and we consider this an inherent methodological limitation of the present work.

Limitations

Our evaluation uses “ground truth” labels produced by a single frozen code-mapping agent (Perplexity), applied consistently to both references and predictions; we use a fixed prompt template and deterministic decoding to minimize variance. Accordingly, all reported scores quantify alignment with a consistent automated coding policy rather than clinician-adjudicated correctness. While this design improves reproducibility, reliance on a single policy introduces mapping bias, and-despite contamination precautions-data leakage from large public corpora cannot be fully excluded. Qualitative review indicates that some apparent errors stem from structural limitations of coding taxonomies (e.g., overlapping ICD-10 hierarchies; divergent ATC leaf mappings for semantically equivalent therapies), so hierarchical-F1 and sentence-similarity metrics may understate clinically acceptable near-misses. In addition, absolute gains are modest in several categories, and generalization remains limited beyond the evaluated ophthalmic tasks and datasets. We therefore interpret low full-code accuracies as the combined effect of model errors and taxonomy constraints, and we frame this work as a reproducible policy-alignment benchmark, not as evidence of clinical accuracy or deployment readiness. Appendix C reports sensitivity analyses with independent mappers and partial human coding. Future work will include multi-rater clinician adjudication on stratified samples (blinded review, consensus procedures, inter-rater agreement such as \(\kappa\)), prospective small-scale evaluations on external notes, and policy-sensitivity analyses across alternative coders and prompting policies.

CliBench utility and generalizability

Applying CliBench to four core tasks-primary/secondary diagnosis, medication, and surgical procedure prediction-revealed fine-grained strengths (e.g., higher surgical procedure accuracy and improved full-code matching) while also exposing areas for improvement. Its hierarchical structure (L1–L4, Full) supports nuanced assessment beyond surface-level correctness and better reflects clinical reasoning fidelity. CliBench also supported comparisons across model sizes and training paradigms, illustrating how Ophtimus-V2-Tx generalizes reasonably on inference-heavy tasks such as PubMedQA despite being tuned for treatment planning; however, these results should be viewed as exploratory rather than uniformly superior. To control mapping variance, we used a single frozen coding agent with an identical prompt for both references and predictions, ensuring a consistent policy across systems. We do not rely on GPT-4o for mapping. As a limitation, we did not include a clinician coding baseline in this submission; Appendix C reports sensitivity analyses (independent mapper and partial human coding), and future work will add multi-rater clinician annotations with inter-rater agreement (e.g., \(\kappa\)) and near-code error typology.

Deployment considerations and intended use

For deployment, the model is intended for decision support rather than autonomous coding. We recommend precision-first operating points with selective abstention, mandatory human review for low-confidence or high-impact codes, and site-specific calibration (reliability assessment/temperature scaling) prior to go-live. A small pre-deployment audit and post-deployment drift monitoring provide additional safeguards for safe integration into coding workflows.

Related works

Expansion of general-purpose and medical-specific LLMs

The recent emergence of various general-purpose Large Language Models (LLMs) has led to remarkable advancements in the field of natural language processing (NLP), demonstrating impressive performance across key tasks such as question answering, summarization, and code generation27,28,29,30. Building on these successes, the application of general-purpose LLMs has rapidly expanded into the medical domain, leading to growing interest in clinical language processing31.

In parallel, a variety of medical-specific LLMs have been developed to address the unique demands of clinical settings. These models have shown significant performance in medical question answering, chest X-ray report generation, and standardized medical examinations such as the USMLE32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. A comprehensive review of the development trends of medical LLMs can be found in Ref. 40.

While these general-purpose and medical-specific LLMs have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in broad medical NLP tasks, they often lack specialization in underrepresented yet clinically important domains such as ophthalmology. In contrast, our work focuses on the development of a lightweight, domain-specific model tailored for ophthalmology, addressing the gap in clinical reasoning performance for this specialty.

Ophthalmology-specific LLMs

In highly specialized medical fields such as ophthalmology, general-purpose LLMs often struggle to support domain-specific diagnostic reasoning or clinical decision making. In fact, degraded performance has been observed on ophthalmology-centered evaluations such as the OKAP, USMLE, and ophthalmology board exams41,42,43. To address these limitations, specialized models such as EyecareGPT44, LEME45, and RETFound46 have been developed for tasks including diagnostic generation, image interpretation, and analysis of long-form clinical case reports.

Unlike previous ophthalmology models that focus primarily on image interpretation or long-form summarization, Ophtimus-V2-Tx is designed to support structured diagnostic reasoning using real-world case reports. It generates multi-dimensional clinical outputs-including primary and secondary diagnoses, medications, and surgical procedures-and is evaluated through code-based frameworks, enabling fine-grained and semantically grounded performance assessment.

LLM-based clinical decision support

While LLMs have achieved strong performance in medical question answering and clinical reasoning tasks47,48, they still face limitations in effectively supporting the end-to-end, structured clinical decision-making process in real-world healthcare environments. To overcome this, instruction-tuned models tailored for the medical domain have been proposed. However, most are optimized for benchmark datasets such as MedQA, PubMedQA, and USMLE-style exams rather than real clinical workflows49,50,51.

Recently, various benchmark studies have been conducted to evaluate the architectures, fine-tuning strategies, and clinical applicability of such models, providing a foundation for their integration into real clinical decision support systems24,52,53,54,55. Comprehensive reviews of these clinical LLMs are available in Refs. 56 and 57.

While many instruction-tuned LLMs are optimized for benchmark datasets and question-answering formats, they often fall short of modeling the structured and sequential nature of real clinical decision-making. Our approach integrates instruction-tuning with a structured evaluation methodology based on the CliBench framework, enabling assessment of end-to-end reasoning through standardized coding systems (ICD-10-CM, ATC, ICD-10-PCS) that align with actual clinical workflows.

Practical value of compact LLM

Given the substantial computational and memory requirements of large language models, there has been increasing attention toward more lightweight alternatives known as compact LLM. These models leverage techniques such as knowledge distillation, pruning, model compression, and quantization to achieve high performance with significantly reduced resource demands. compact domain-specialized LLM are particularly valuable in resource-constrained environments, such as mobile devices, edge computing platforms, and on-premise hospital servers.

Notable examples of compact LLM include DistilBERT58, TinyBERT59, MobileBERT60, and TinyLlama61, which are actively used in clinical chatbot systems and medical information retrieval assistants. A detailed survey of these small models and optimization techniques can be found in Ref. 62, which systematically reviews recent advances in model compression strategies and evaluates their performance across various clinical NLP tasks.

Compared to existing general-purpose and domain-specific LLMs, our study introduces a novel ophthalmology-focused small language model that bridges performance and practicality. By leveraging real-world clinical narratives, multi-faceted output generation, and semantically grounded evaluation through standardized medical coding systems, Ophtimus-V2-Tx presents a scalable and clinically relevant alternative for intelligent decision support in specialty medicine.

Conclusion

Summary of findings

We present Ophtimus-V2-Tx, a small, domain-specific language model (SLM) for ophthalmology, tuned on schema-structured case reports and evaluated with automated diagnostic reasoning and standardized benchmarking tasks (ICD-10-CM/ATC/ICD-10-PCS; L1–L4 and Full) alongside narrative similarity metrics.

This study is positioned as a benchmarking comparison between a compact, ophthalmology-specific model (Ophtimus-V2-Tx) and large general-purpose LLMs, designed to assess how domain-specific fine-tuning and structured supervision influence diagnostic reasoning and representational alignment in ophthalmic narratives. The purpose of this work is to derive methodological insights into effective development choices for domain-specialized medical LLMs, not to claim clinical deployment readiness. The code-mapping tasks (ICD/ATC/PCS) are employed solely as standardized, quantifiable benchmarks for evaluating model reasoning, rather than as evidence of autonomous code-generation capability.

On our benchmarks, Ophtimus-V2-Tx achieves competitive performance on selected structured tasks, with fine-grained strengths at exact medication/procedure codes and certain hierarchical levels, while absolute gains are modest in several categories and statistical significance is not uniform.

In the context of prior ophthalmology-focused LLMs (Ophtha-LLaMA2, EyeGPT, LEME)-which emphasize MCQA or text QA and generally lack code-based evaluation-our case-based tuning and code-aligned assessment help bridge educational QA benchmarks and real-world clinical reasoning within a reproducible benchmarking framework that translates narrative reasoning into standardized, comparable metrics.

All reported metrics reflect alignment with a frozen automated coding policy rather than clinician-adjudicated correctness. Accordingly, the evaluation framework serves as a policy-alignment benchmarking environment to quantify reasoning alignment, not to infer clinical accuracy or deployment feasibility. To enhance reproducibility, the coding agent and prompts were version-locked during evaluation (see Methods). Future work will incorporate structured clinician review of model outputs to anchor automated results to clinically meaningful standards, alongside sensitivity analyses across alternative coding agents and prompting policies to quantify policy dependence, complementing multi-rater adjudication and prospective validation in subsequent iterations.

Future directions

Methodologically, we will expand clinician-adjudicated reference subsets and conduct structured, blinded multi-rater evaluations (with predefined consensus procedures and inter-rater agreement reporting, e.g., \(\kappa\)) to validate automated mapping outputs, characterize near-miss typologies, and ground benchmarking metrics in clinically interpretable standards. In parallel, targeted clinician review of representative model outputs will be introduced to qualitatively assess reasoning fidelity and contextual correctness, providing a bridge between automated evaluation and clinical relevance.

Beyond model evaluation, we will implement a structured program of data-fidelity verification to address current limitations in schema-level validation. Specifically, we will run a statistically powered, stratified sampling audit (stratified by diagnosis/procedure/medication and by document length/source) to quantify token- and field-level fidelity using predefined rubrics: exact-match rates for named tests, laterality agreement (OD/OS/OU rules), and numeric consistency with absolute/relative tolerances and unit checks, along with a structured error taxonomy (omission, substitution/paraphrase, numeric transformation, laterality inversion). We plan to report inter-rater agreement (e.g., \(\kappa\) or Gwet’s AC1) and, where applicable, 95% confidence intervals for the clinician-reviewed subset. In parallel, reinforcement-learning–based preference alignment (RLHF and related human-feedback methods) will be used to automatically detect and correct deviations from verbatim schema preservation. Collectively, these procedures will operate as a continuous data-governance loop, improving fidelity, quality control, and reproducibility across subsequent Ophtimus iterations.

We will also adopt precision-first operating points with selective abstention, site-specific calibration, and post-deployment drift monitoring to ensure safe experimental use in decision-support and research benchmarking contexts, rather than autonomous clinical coding.

Technically, we will explore multimodal inputs (e.g., OCT and fundus imaging) and agentic or ensemble architectures to enhance reasoning robustness and domain specificity, while extending evaluation to additional ophthalmic subspecialties and expanded QA datasets for broader benchmarking.

Continued mapper sensitivity analyses (including cross-mapper checks) will be maintained as code systems and data distributions evolve.

Data availability

The clinical case reports used to fine-tune Ophtimus-V2-Tx are available at: MCQA Dataset—https://huggingface.co/datasets/BaekSeungJu/Ophthalmology-MCQA-v3, EQA Dataset—https://huggingface.co/datasets/BaekSeungJu/Ophthalmology-EQA-v3, Case Report Dataset (Train)—https://huggingface.co/datasets/MinWook1125/Ophthalmology-Case-Report-Train, Case Report Dataset (Test)—https://huggingface.co/datasets/MinWook1125/Ophthalmology-Case-Report-Test. The model checkpoints used in this study are available at: Ophtimus-V2-Base: https://huggingface.co/BaekSeungJu/Ophtimus-8B-Base, Ophtumus-V2-Tx: https://huggingface.co/MinWook1125/Opthimus_MCQA_EQA_CR_2500. Currently, the Ophtimus-V2-Tx model and the Case Report Dataset (Train/Test) are set to private. These resources will be made publicly available following the publication of the manuscript.

References

Pressman, S. M. et al. Clinical and surgical applications of large language models: A systematic review. J. Clin. Med. 13, 3041 (2024).

Oniani, D. et al. Enhancing large language models for clinical decision support by incorporating clinical practice guidelines. In 2024 IEEE 12th International Conference on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI), 694–702 (IEEE, 2024).

Guo, E. et al. Automated paper screening for clinical reviews using large language models: Data analysis study. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e48996 (2024).

Meta. Llama-3.1-8B. https://huggingface.co/meta-llama/Llama-3.1-8B (2024). Hugging Face. Accessed 23 July 2024.

Banayot, R. Ophthalmic Trivia. https://huggingface.co/datasets/BaekSeungJu/OphtimusEval-Dataset (2025). Hugging Face. Accessed: 24 June 2025.

Baek, S. J. et al. Ophtimus-LLM: Development of a specialized large language model for ophthalmology. In Workshop on Large Language Models and Generative AI for Health at AAAI 2025 (2025).

Baek, S. J. et al. Ophtimus-V2-8B-Base. https://huggingface.co/BaekSeungJu/Ophtimus-8B-Base (2025). Hugging Face. Accessed 20 March 2025.

Lin, C.-Y. Rouge: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In Text summarization branches out, 74–81 (2004).

Papineni, K., Roukos, S., Ward, T. & Zhu, W.-J. BLEU: A method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 311–318 (2002).

Banerjee, S. & Lavie, A. Meteor: An automatic metric for MT evaluation with improved correlation with human judgments. In Proceedings of the ACL Workshop on Intrinsic and Extrinsic Evaluation Measures for Machine Translation and/or Summarization, 65–72 (2005).

Aynetdinov, A. & Akbik, A. Semscore: Automated evaluation of instruction-tuned LLMS based on semantic textual similarity. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2401.17072 (2024).

Pal, A., Umapathi, L. K. & Sankarasubbu, M. MedMCQA: A large-scale multi-subject multi-choice dataset for medical domain question answering. In Flores, G., Chen, G. H., Pollard, T., Ho, J. C. & Naumann, T. (eds.) Proceedings of the Conference on Health, Inference, and Learning, vol. 174 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, 248–260 (PMLR, 2022).

Jin, Q., Dhingra, B., Liu, Z., Cohen, W. W. & Lu, X. PubMedQA: A dataset for biomedical research question answering. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1909.06146 (2019).

Forrester, J. V., Dick, A. D., McMenamin, P. G., Roberts, F. & Pearlman, E. Uveitis: Fundamentals and Clinical Practice 4th edn. (Saunders Elsevier, Edinburgh, 2010).

Basic and clinical science course (BCSC) 2023–2024: Sections 2–13 (2024). Section 2: Fundamentals & Principles; 3: Clinical Optics & Vision Rehabilitation; 4: Ophthalmic Pathology & Intraocular Tumors; 5: Neuro-Ophthalmology; 6: Pediatric Ophthalmology & Strabismus; 7: Oculofacial Plastic & Orbital Surgery; 8: External Disease & Cornea; 9: Uveitis & Ocular Inflammation; 10: Glaucoma; 11: Lens & Cataract; 12: Retina & Vitreous; 13: Refractive Surgery.

Shukla, Y. & Saxena, R. Clinical Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus (Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers, New Delhi, 2023).

Salmon, J. F. Kanski’s Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach 10th edn. (Elsevier, London, 2024).

James, B., Bron, A. & Parulekar, M. V. Ophthalmology (Lecture Notes) 11th edn. (Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, 2017).

Root, T. OphthoBook (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, Scotts Valley, CA, 2009).

Jogi, R. Basic Ophthalmology 4th edn. (Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers, New Delhi, 2009).

Mittal, S. & Agarwal, R. Textbook of Ophthalmology 2nd edn. (Thieme Medical and Scientific Publishers, Bengaluru, 2025).

Hu, E. J. et al. LoRA: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 1, 3 (2022).

Ohlendorff, J. S., Munch, A., Sørensen, K. K. & Gerds, T. A. Cheap subsampling bootstrap confidence intervals for fast and robust inference. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2501.10289 (2025).

Ma, M. D. et al. CliBench: A multifaceted and multigranular evaluation of large language models for clinical decision making. https://openreview.net/forum?id=E3LDsbUSRZ (2025).

National Center for Biomedical Ontology. ATC Ontology—NCBO BioPortal. https://bioportal.bioontology.org/ontologies/ATC?utm_source=chatgpt.com (2025). Last uploaded: January 16, 2025. Accessed 08 Sept 2025.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. ICD-10 Codes. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/coding-billing/icd-10-codes (2025). Accessed 08 Sept 2025.

Achiam, J. et al. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2303.08774 (2023).

Anil, R. et al. Palm 2 technical report. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2305.10403 (2023).

Grattafiori, A. et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2407.21783 (2024).

Jiang, J., Wang, F., Shen, J., Kim, S. & Kim, S. A survey on large language models for code generation. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2406.00515 (2024).

Lehman, E. et al. Do we still need clinical language models? In Conference on health, inference, and learning, 578–597 (PMLR, 2023).

Yang, X. et al. A large language model for electronic health records. NPJ Digital Med. 5, 194 (2022).

Singhal, K. et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 620, 172–180 (2023).

Singhal, K. et al. Toward expert-level medical question answering with large language models. Nat. Med. 31(3), 943–950 (2025).

Kung, T. H. et al. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLoS Digital Health 2, e0000198 (2023).

Ayers, J. W. et al. Comparing physician and artificial intelligence chatbot responses to patient questions posted to a public social media forum. JAMA Intern. Med. 183, 589–596 (2023).

Tu, T. et al. Towards generalist biomedical AI. NEJM AI 1, AIoa2300138 (2024).

Han, T. et al. MedAlpaca—an open-source collection of medical conversational AI models and training data. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2304.08247 (2023).

Saab, K. et al. Capabilities of Gemini models in medicine. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2404.18416 (2024).

Thirunavukarasu, A. J. et al. Large language models in medicine. Nat. Med. 29, 1930–1940 (2023).

Antaki, F., Touma, S., Milad, D., El-Khoury, J. & Duval, R. Evaluating the performance of ChatGPT in ophthalmology: An analysis of its successes and shortcomings. Ophthalmol. Sci. 3, 100324 (2023).

Haddad, F. et al. Performance of ChatGPT on ophthalmology-related questions across various examination levels: Observational study. JMIR Med. Educ. 10, e50842 (2024).

Shemer, A. et al. Diagnostic capabilities of ChatGPT in ophthalmology. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 262, 2345–2352 (2024).

Li, S. et al. EyecareGPT: Boosting comprehensive ophthalmology understanding with tailored dataset, benchmark and model. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2504.13650 (2025).

Gilson, A. et al. Language Enhanced Model for Eye (LEME): An open-source ophthalmology-specific large language model. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2410.03740 (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. A foundation model for generalizable disease detection from retinal images. Nature 622, 156–163 (2023).

Hager, P. et al. Evaluation and mitigation of the limitations of large language models in clinical decision-making. Nat. Med. 30, 2613–2622 (2024).

Shool, S. et al. A systematic review of large language model (LLM) evaluations in clinical medicine. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 25, 117 (2025).

Kim, J. et al. Limitations of large language models in clinical problem-solving arising from inflexible reasoning. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2502.04381 (2025).

Bean, A. M. et al. Clinical knowledge in LLMS does not translate to human interactions. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2504.18919 (2025).

Vishwanath, K. et al. Medical large language models are easily distracted. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2504.01201 (2025).

Yang, Z., Mitra, A., Kwon, S. & Yu, H. ClinicalMamba: A generative clinical language model on longitudinal clinical notes. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2403.05795 (2024).

Jiang, S. et al. MedS3: Towards medical small language models with self-evolved slow thinking. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2501.12051 (2025).

Dada, A. et al. CLUE: A clinical language understanding evaluation for LLMS. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2404.04067 (2024).

Bedi, S. et al. MedHELM: Holistic evaluation of large language models for medical tasks. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2505.23802 (2025).

Liu, F. et al. Large language models in the clinic: A comprehensive benchmark. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2405.00716 (2024).

Artsi, Y. et al. Large language models in real-world clinical workflows: A systematic review of applications and implementation. medRxiv 2025-06 (2025).

Sanh, V., Debut, L., Chaumond, J. & Wolf, T. DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: Smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1910.01108 (2019).

Jiao, X. et al. TinyBERT: Distilling BERT for natural language understanding. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1909.10351 (2019).

Sun, Z. et al. MobileBERT: A compact task-agnostic BERT for resource-limited devices. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2004.02984 (2020).

Zhang, P., Zeng, G., Wang, T. & Lu, W. TinyLlama: An open-source small language model. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2401.02385 (2024).

Wang, F. et al. A comprehensive survey of small language models in the era of large language models: Techniques, enhancements, applications, collaboration with LLMS, and trustworthiness. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2411.03350 (2024).

Baek, S. J. Ophthalmology-PubMed-Corpus. https://huggingface.co/datasets/BaekSeungJu/Ophthalmology-PubMed-Corpus (2025). Accessed 14 July 2025.

Baek, S. J. Ophthalmology-Textbook-Corpus. https://huggingface.co/datasets/BaekSeungJu/Ophthalmology-Textbook-Corpus (2025). Accessed 14 July 2025.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Education, Science and Technology) (NRF-2023R1A2C1006639), and by the research grant of Gyeongsang National University in 2024, in part by the National Institutes of Health under Grant 1R01EY037101.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.K. conceived the main idea and conducted the overall experiments and data preparation. S.B. contributed to base model development and data collection. Y.H. supported medical data preprocessing and model evaluation. H.C. participated in data processing and AI model training. K.J.J. contributed to evaluation and presentation of the results. I.L. advised on project direction and revised the manuscript. J.H.K. supervised the project and coordinated the overall research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

A. Diagnosis and treatement evaluation: accuracy, precision, recall

B.1 PHI removal and preservation policy

Objective

Remove or de-identify protected health information (PHI) while preserving clinical signals required for modeling and evaluation.

Remove/replace

-

Personal/Institutional identifiers: patient/clinician names or initials; hospital/institution names; emails, phone/fax; social handles; signatures/watermarks; access tokens.

-

Fine-grained geographies: street address, ZIP/postal code, city/district, ward/room. (Preserve only country/region-level.)

-

Exact dates/times: admission, surgery, follow-up dates (YYYY-MM-DD) and clock times \(\rightarrow\) year only (YYYY) or relative intervals (e.g., “3 months after surgery”).

-

High-specificity codes/IDs: MRN, accession numbers, device serials, claim/insurance numbers, file/image IDs, URLs, IPs, document GUIDs \(\rightarrow\) neutral tokens (e.g., [ID], [URL]).

-

Contact/affiliation lines: “Correspondence to...”, full mailing addresses, departmental footers.

Preserve (verbatim)

-

Quantitative measurements: IOP (mmHg), BCVA, thicknesses, lab values, ranges.

-

Laterality tokens: OD/OS/OU.

-

Test modalities: OCT/FA/OCTA, fundus, VF, etc.

-

Explicit findings and interpretations.

-

Medications and procedures (generic/standard names) for code mapping (ATC, ICD-10-PCS).

-

Relative time expressions (e.g., “after 3 months,” “1-week follow-up”).

See also: Appendix B (Prompts for GPT-based Filtering/Formatting) for classifier prompts and examples.

B.2 Prompts for GPT-based filtering

B.3 GPT-based formatting: prompts

C.1 Code Mapper analysis

We evaluate four mappers (OpenAI, Claude, Gemini, Perplexity) across three coding systems (ATC, ICD-10-CM, ICD-10-PCS). Predictions marked “X” are treated as abstentions. For each system and mapper, we compute-per instance and then averaged-(i) Abstain rate; (ii) Error distance on non-abstaining errors (ATC/CM: hierarchical distance from the shared prefix-\(0\) exact, larger = farther; PCS: 7-axis Hamming distance, \(0{-}7\)); (iii) Close miss rate (ATC: same L2; CM: same 3-character category; PCS: same first three axes), indicating domain-level agreement but sub-level mismatch; and (iv) Under-specificity proxies (ATC: 1-L5 specificity; CM: 1-full specificity [7 characters]; PCS: not applicable).

To form the Bias score (lower = better) within each system, we min–max normalize the applicable components (Abstain, Error distance, Close miss, and Under-specificity when defined) across mappers and take their arithmetic mean; non-applicable components are omitted from the average. The Bias score intentionally excludes accuracy, focusing on behavioral bias (abstention, specificity, and error depth/patterns). Results are reported as system-level summaries per mapper. CS. Gemini achieves the lowest bias; Claude abstains least but has higher close-miss; Perplexity ranks worst due to high abstention despite low error distance.

The meta ranking is: OpenAI (0.372) < Gemini (0.446) < Claude (0.479) < Perplexity (0.615). ATC. Perplexity has the lowest bias but shows the largest error distance when wrong; OpenAI has higher abstention and close-miss. ICD-10-CM. OpenAI yields the lowest bias, combining very low abstention with high specificity; Perplexity is penalized by high abstention. ICD-10-PCS. Gemini achieves the lowest bias; Claude abstains least but exhibits higher close-miss; Perplexity ranks worst due to high abstention despite relatively low error distance. Overall, these system-level patterns are consistent with Table 18 and explain the meta ranking in Table 19, which excludes accuracy and focuses on behavioral bias (abstention, specificity, and error depth/patterns).

Summary and selection criteria Bias was assessed using a composite Bias score (lower is better), comprising abstention rate, error distance, close-miss rate, and system-specific under-specificity; accuracy is intentionally excluded. System-level results are shown in Table 18. At the L4 level, Perplexity achieved clearly superior accuracy across all three systems (Table 20; e.g., ATC 81.8%, CM 33.33%, PCS 28.80%). Accordingly, prioritizing the practical objective of fine-grained accuracy, we adopt Perplexity as the default code mapper in this study.

Future operational plan Perplexity can exhibit larger error distances when wrong in ATC and potentially higher abstention rates in CM/PCS. Hence, we will apply rule-based guardrails triggered by (i) abstention (“X”), (ii) ATC “Other” selections (L3/L4 = ‘X’), (iii) CM .9 unspecified, and (iv) PCS Device/Qualifier = ‘Z’; and, when necessary, will perform cross-checks with auxiliary mappers (Gemini/Claude/OpenAI). These procedures are introduced as complementary measures to retain the advantages of L4 accuracy while systematically mitigating risks arising from bias-related heuristics (Table 21).