Abstract

To investigate the association between edentulism and frailty across nationally representative cohorts in China, the United Kingdom, and the United States. A harmonized analysis was conducted using longitudinal data from the CHARLS, ELSA, and HRS cohorts. This study examined the association between self-reported edentulism (exposure) and frailty (outcome), with adjustment for self-reported covariates including age, gender, lifestyle factors, and comorbidities. Multivariable linear and logistic regression models were applied to examine the associations of edentulism with the frailty index and frailty phenotype, respectively. To synthesize effect estimates across cohorts, fixed- and random-effects meta-analyses were conducted. Robustness was assessed through stratified analyses by age and gender, as well as through multiple imputation to address missing data. A total of 9,869 participants from CHARLS (female: 52.9%, mean age: 61.2 years), 5,083 from ELSA (female: 55.7%, mean age: 62.7 years), and 12,322 from HRS (female: 59.5%, mean age: 65.8 years) were included. Meta-analysis of the fully adjusted models across cohorts revealed that edentulous individuals exhibited significantly higher frailty index scores (pooled mean difference = 2.68; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.67–3.69) and increased odds of frailty status (pooled odds ratio = 1.38; 95% CI: 1.26–1.50) compared to dentate counterparts. These associations remained robust in stratified and sensitivity analyses. Edentulism is independently associated with frailty across aging populations. These findings underscore the clinical relevance of oral health in geriatric risk assessment and support the integration of dental evaluation into multidisciplinary strategies for frailty management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As human life expectancy continues to rise, population aging is accelerating worldwide, placing growing strain on healthcare systems and social infrastructure1. Frailty, a progressive clinical syndrome characterized by diminished physiological reserve and resilience, substantially increases the risk of falls, disability, hospitalization, and mortality among older adults2. Importantly, frailty is also recognized as a dynamic and potentially reversible condition, highlighting the critical importance of identifying modifiable risk factors to inform prevention and intervention strategies3. Given its significant clinical and societal burden, increasing attention is being directed toward identifying modifiable risk factors to inform prevention strategies4.

Edentulism, defined as the complete loss of all natural teeth, affects millions of older adults, but remains insufficiently acknowledged within the discourse of geriatric health5. Beyond its immediate impact on oral function, edentulism compromises masticatory efficiency, restricts dietary diversity, and contributes to malnutrition, systemic inflammation, and physical deterioration6. These multifaceted consequences position edentulism as a salient yet frequently overlooked indicator of systemic physiological decline in the elderly7.

The persistent belief that “tooth loss is an unavoidable aspect of aging” continues to influence public perception. However, this notion is increasingly at odds with a growing body of evidence emphasizing the integral role of oral health in overall well-being8. Edentulism should not be regarded as an inevitable outcome of aging but rather as the culmination of cumulative biological, behavioral, and social vulnerabilities9. As the concept of the oral-systemic connection gains traction within geriatric medicine, tooth loss is being reconceptualized not merely as a localized dental issue but as both a visible manifestation and a potential contributor to multisystem deterioration, including the development of frailty10.

A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that edentulous older adults are approximately 69% more likely to be frail compared to their dentate counterparts11. Existing aggregate evidence relies predominantly on summary-level meta-analyses of heterogeneous investigations. Variations in population characteristics, variable definitions, and analytical methods across original studies constrain the credibility and generalizability of the reported associations. To address this gap, the present study investigates the association between edentulism and frailty using harmonized analytical procedures across three large-scale, previously unexamined, population-based cohorts.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

We conducted a longitudinal analysis utilizing the most recent available wave of data from three nationally representative cohort studies: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS; waves 1–4, 2011–2018), the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA; waves 7–9, 2014–2019), and the Health and Retirement Study (HRS; waves 11–14, 2012–2018), conducted in China, the United Kingdom, and the United States, respectively12,13,14. The follow-up waves were intentionally chosen to maximize the comparability of the time span across cohorts and to ensure data completeness for a robust comparative analysis. Ethical approvals were obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Peking University (CHARLS), the London Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee (ELSA), and the University of Michigan (HRS). All participants provided written informed consent. Standardized exclusion criteria across the cohorts included: (1) age ≤ 50 years at baseline; and (2) missing data on edentulism, frailty, or any covariates.

Edentulism assessment

Edentulism was defined as the self-reported complete loss of all natural teeth, assessed through a structured questionnaire administered during the designated baseline wave for this study (CHARLS: wave 1, 2011; ELSA: wave 7, 2014; HRS: wave 11, 2012). Participants responded to a standardized and validated screening item: “Have you experienced complete loss of all natural teeth?” Responses were recorded as a dichotomous variable (yes/no).

Frailty assessment

The frailty index (FI) was constructed using 32 age-related variables encompassing chronic diseases, functional impairments, self-rated health, depressive symptoms, and cognitive function15. Items 1–31 were coded as binary variables, while Item 32 (cognitive score) was continuous (Supplementary Table 1). The FI was calculated as the ratio of present deficits to the total number of non-missing items, producing a score ranging from 0 to 100%, with higher scores indicating greater frailty. Based on established thresholds, participants were classified as frail (FI > 25%) or robust (FI ≤ 25%)16. Individuals with more than two missing items were excluded. Due to substantial missing data at baseline, the most recent wave with complete frailty information was used (CHARLS: wave 4, 2018; ELSA: wave 9, 2019; HRS: wave14, 2018).

Covariates

All covariates were ascertained from the baseline wave of each cohort: CHARLS, wave 1, 2011; ELSA, wave 7, 2014; HRS, wave 11, 2012. Baseline covariates included sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, educational attainment), lifestyle factors (smoking status, drinking status, physical activity), and clinical conditions (hypertension, diabetes). To ensure cross-cohort comparability, ethnicity was dichotomized as majority (Han ethnicity in CHARLS; White ethnicity in ELSA and HRS) versus non-majority. Educational attainment was categorized as below high school, high school, and college or above. Smoking and drinking status were each classified as never or ever. Physical activity was defined as engagement in regular moderate or vigorous exercise. Hypertension and diabetes were identified based on self-reported physician diagnoses.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics. Continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations (SD), and categorical variables as frequencies with percentages. Group differences across edentulism status were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Associations between edentulism and frailty outcomes were evaluated using multivariable linear regression for the frailty index and multivariable logistic regression for the frailty status. Effect estimates were expressed as mean differences (MDs) or odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Four sequential models were constructed: Model 1 was unadjusted; Model 2 adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, and education; Model 3 further adjusted for smoking status, alcohol status, and physical activity; and Model 4 additionally included hypertension and diabetes.

To synthesize effect estimates across the three cohorts, both fixed- and random-effects meta-analyses were conducted. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic; when I2 exceeded 50%, random-effects models were applied, otherwise fixed-effects models were used. Robustness was evaluated through stratified analyses by age and gender, and through multiple imputation for missing data using the missForest and Amelia algorithms.

All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.3.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The software is freely available at https://www.R-project.org/. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

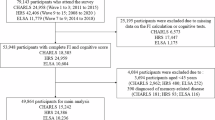

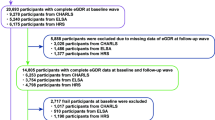

According to the exclusion criteria, a total of 9,869 participants from CHARLS (52.9% female; mean age, 61.2 years), 5,083 from ELSA (55.7% female; mean age, 62.7 years), and 12,322 from HRS (59.5% female; mean age, 65.8 years) were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Baseline characteristics of participants by edentulism status across cohorts are summarized in Table 1. In CHARLS, 9.17% of participants were edentulous; in ELSA, 8.42%; and in HRS, 14.62%. Across all three cohorts, edentulous individuals were significantly older and had higher frailty index scores compared to dentate participants. They were also more likely to be female, have lower educational attainment (e.g., below high school), and report never drinking alcohol. Additionally, edentulous participants had a higher prevalence of hypertension and diabetes in ELSA and HRS, though this difference was not statistically significant in CHARLS. Conversely, dentate individuals were more likely to engage in regular physical activity and had a lower prevalence of frailty. These patterns highlight consistent sociodemographic and health disparities associated with edentulism across diverse populations.

In the CHARLS, ELSA, and HRS cohorts, the frailty index of edentulous individuals was significantly higher than that of dentate individuals (Fig. 2).

In unadjusted models (Model 1), edentulous individuals were significantly more likely to be frail than their dentate counterparts, with ORs of 1.88 (95% CI: 1.64–2.15) in CHARLS, 2.93 (95% CI: 2.39–3.58) in ELSA, and 2.65 (95% CI: 2.39–2.93) in HRS. Edentulism was also associated with higher FI scores, with MDs of 5.66% (95% CI: 4.59%–6.72%), 9.49% (95% CI: 8.07%–10.91%), and 9.58% (95% CI: 8.78%–10.38%) in CHARLS, ELSA, and HRS, respectively.

In the fully adjusted model (Model 2), edentulous individuals had increased odds of frailty, with ORs of 1.24 (95% CI: 1.06–1.44) in CHARLS, 1.33 (95% CI: 1.05–1.68) in ELSA, and 1.48 (95% CI: 1.31–1.67) in HRS. Correspondingly, FI scores remained elevated by 1.82% (95% CI: 0.81%−2.84%) in CHARLS, 2.66% (95% CI: 1.39%−3.94%) in ELSA, and 3.40% (95% CI: 2.70%−4.10%) in HRS (Table 2).

To synthesize effect estimates and enhance statistical power, meta-analyses were conducted across the three cohorts. For the frailty phenotype, low heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 39.4%), and a fixed-effects model yielded a pooled OR of 1.38 (95% CI: 1.26–1.50), indicating significantly greater odds of frailty among edentulous individuals. In contrast, substantial heterogeneity was observed for FI scores (I2 = 68.7%); using a random-effects model, edentulism was associated with a pooled MD of 2.68 (95% CI: 1.67–3.69) in FI scores compared to dentate counterparts (Fig. 3).

In age-stratified analyses, significant heterogeneity was observed in the ELSA cohort, where the association between edentulism and frailty status was stronger among participants aged ≤ 65 years (Supplementary Table 2). Nevertheless, age-stratified associations remained statistically significant across all cohorts (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 3). Gender-stratified analyses didn’t reveal consistent heterogeneity; however, in the fully adjusted model (Model 4) for ELSA, the association between edentulism and frailty outcomes was no longer statistically significant among female participants (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 4).

To address potential bias from missing data, multiple imputation was performed using both the missForest and Amelia algorithms. Post-imputation analyses confirmed the robustness of the findings, with consistent associations observed between edentulism and frailty outcomes across all three cohorts (Supplementary Table 5). When analyzing only the baseline non-frail population, edentulism remained significantly associated with incident frailty in HRS after full adjustment, but showed attenuated associations in CHARLS and ELSA cohorts (Supplementary Table 6). Also, after adjusting for baseline frailty index, the association between edentulism and frailty was substantially attenuated and became non-significant in CHARLS and ELSA cohorts, but remained significant in HRS. (Supplementary Table 7).

Discussion

Using harmonized data from nationally representative cohorts in China, the United Kingdom, and the United States, this study provides compelling evidence that edentulism is independently associated with frailty in older adults, reinforcing the critical and generalizable role of oral health in the context of geriatric vulnerability.

Our findings consolidate and extend epidemiological evidence linking tooth loss to frailty. Single-nation studies across diverse populations, including China (CLHLS), Chile, and the UK, have consistently demonstrated elevated frailty risk associated with edentulism and partial tooth loss16,17,18. This association has been further corroborated by recent meta-analyses, which synthesized global evidence and confirmed that tooth loss, functional dentition absence, and lack of denture use significantly predict frailty11,19,20.

However, these previous investigations have been constrained by methodological heterogeneity, inconsistent frailty definitions, and limited generalizability21. To address these limitations, recent research has shifted toward harmonized, multi-cohort designs, as seen in studies using CHARLS, ELSA, HRS, SHARE, and MHAS22,23,24, to improve cross-national comparability and analytical robustness. This harmonized multinational approach strengthens the evidence for a potential causal relationship by eliminating methodological heterogeneity through standardized protocols. It ensures external validity by replicating findings across disparate populations, and establishes cross-cultural generalizability by demonstrating consistent effects despite varying socioeconomic contexts, healthcare systems, and cultural norms.

Following this paradigm, our study integrates data from three independent, methodologically harmonized cohorts. Our approach provides the first directly comparable evidence across three diverse national contexts (China, the UK, and the US), demonstrating that the edentulism-frailty link is robust and persists irrespective of major differences in socioeconomic contexts, healthcare systems, and cultural norms (including diet and aging cultures). By utilizing standardized models, stratified analyses, and rigorous sensitivity testing, we further establish that this relationship is not attributable to methodological artifact. Consequently, our findings substantially extend knowledge by confirming the universal nature of this association and providing a methodologically robust, generalizable evidence base for future research and policy.

The biological plausibility of the association between edentulism and frailty is supported by multiple converging pathways. Tooth loss may contribute to frailty through intertwined nutritional, psychosocial, and functional mechanisms that collectively accelerate physiological decline25. Impaired mastication restricts the intake of high-quality protein, fiber, and essential micronutrients that are critical components for maintaining muscle mass, immune function, and metabolic homeostasis26. Chronic nutritional deficiencies may subsequently lead to sarcopenia, energy imbalance, and immune dysregulation, all of which are hallmark features of frailty in later life27. Besides, the psychosocial consequences of edentulism are increasingly recognized. Aesthetic concerns, reduced self-esteem, and communication difficulties may contribute to social withdrawal and depressive symptoms—both of which are independently associated with elevated frailty risk28. These findings suggest that although tooth loss is anatomically localized, it may instigate systemic vulnerability through behavioral disengagement and biological dysregulation29.

Inflammatory and neurophysiological pathways further support the role of poor oral health in frailty development30. Periodontitis, the leading cause of adult tooth loss, triggers chronic low-grade inflammation, marked by elevated levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP), two biomarkers consistently linked to frailty, sarcopenia, and functional impairment31. Additionally, the loss of periodontal proprioceptors may compromise neuromuscular feedback essential for postural control, thereby increasing the risk of falls, a sentinel event in frailty progression32. These mechanisms are further exacerbated by comorbid conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, which amplify systemic inflammation and accelerate physical decline, collectively supporting a syndemic framework in which tooth loss serves both as a marker of underlying vulnerability and an active contributor to the onset and progression of frailty33.

It is important to note the substantial baseline differences in demographics and health status among CHARLS, ELSA, and HRS (Table 1), which reflect real-world disparities in aging experiences, healthcare systems, and socioeconomic contexts across China, the UK, and the US. Rather than undermining our findings, this diversity enhances their external validity. These population differences likely contributed to the substantial heterogeneity (I² > 60%) in the frailty index meta-analysis. Rather than a statistical limitation, this heterogeneity probably reflects genuine contextual variation in the association’s strength. Importantly, despite variations in baseline characteristics and effect size, the consistent direction of effect across all cohorts underscores a robust, transcultural relationship between edentulism and frailty. Furthermore, the heterogeneity observed in stratified analyses, such as the non-significant association among females in ELSA, suggests potential effect modification by unmeasured country- or gender-specific factors, such as denture quality or healthcare access34. These findings highlight the need to investigate social and clinical determinants underlying this varied risk.

Despite its strengths, our study has several limitations. First, due to variation in data availability across cohorts, we were unable to incorporate additional oral health indicators, such as the number of remaining teeth or denture use, into a unified analytical model. The use of a binary edentulism variable may therefore overlook clinically meaningful variation. For instance, well-fitted dentures might reduce frailty risk by improving nutrition, while poor oral health among dentate individuals could increase risk due to inflammation. So, the observed association likely reflects both historical inflammatory exposure and ongoing nutritional influences; however, distinguishing their relative contributions requires finer-grained data. Second, although our design incorporated a prospective component, with edentulism assessed at baseline and frailty measured at follow-up, the lack of individualized frailty trajectories limited our ability to conduct time-to-event analyses (e.g., Cox regression). Therefore, the strong association observed does not resolve issues of temporality, and a bidirectional relationship remains plausible. Third, while our sensitivity analyses addressed key confounding by baseline health status, residual confounding from unmeasured factors (e.g., dietary biomarkers, inflammatory mediators, and oral hygiene practices) may partially explain the attenuated associations observed after adjusting for baseline frailty and the inconsistencies across cohorts. This underscores the complex, multifactorial nature of the edentulism-frailty relationship. Finally, we relied on self-reported edentulism status. Although this measure has been validated in large-scale epidemiological studies due to its high specificity and acceptable sensitivity35,36, and is practically necessary in such population-based studies, it may still introduce misclassification bias37.

Despite these limitations, our findings highlight key clinical implications. While edentulism is irreversible, its sequelae can be managed. Clinicians should address inflammatory sources (e.g., residual roots)38 and provide functional dentures to restore mastication, improve nutrition, and enhance quality of life39. Edentulism should thus trigger comprehensive oral rehabilitation rather than signify an endpoint. Future research should incorporate multiple dimensions of oral health indicators, such as oral frailty, chewing ability and oral hygiene, in order to determine precise intervention targets and thereby alleviate the condition of frailty.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this multi-cohort analysis provides robust evidence that edentulism is independently associated with frailty in older adults. These findings underscore the role of oral health as a modifiable and clinically relevant factor within the multidimensional construct of frailty. From both clinical and public health perspectives, integrating dental assessments into routine geriatric evaluations may enable the early identification of at-risk individuals and inform more comprehensive frailty prevention strategies. Future research should clarify the causal mechanisms and biological mediators of this association, and assess the efficacy of targeted oral health interventions in modifying the course of frailty.

Data availability

The original datasets can also be accessed upon application through the official websites of the respective cohort studies. CHARLS (China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study): http://charls.pku.edu.cn. ELSA (English Longitudinal Study of Ageing): https://www.elsa-project.ac.uk. HRS (Health and Retirement Study): https://hrs.isr.umich.edu.

References

The Lancet Healthy. Longevity, N. Care for ageing populations globally. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2, e180 (2021).

Hoogendijk, E. O. et al. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet (lond Engl). 394, 1365–1375 (2019).

Deng, Y., Zhang, K., Zhu, J., Hu, X. & Liao, R. Healthy aging, early screening, and interventions for frailty in the elderly. BST 17, 252–261 (2023).

Kim, D. H. & Rockwood, K. Frailty in older adults. N Engl. J. Med. 391, 538–548 (2024).

Qin, X. et al. Projecting trends in the disease burden of adult edentulism in China between 2020 and 2030: a systematic study based on the global burden of disease. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1367138 (2024).

Hunter, E. et al. Impact of edentulism on community-dwelling adults in low-income, middle-income and high-income countries: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 14, e085479 (2024).

Chen, H. M., Shen, K., Ji, L., McGrath, C. & Chen, H. Global and regional patterns in edentulism (1990–2021) with predictions to 2040. Int. Dent. J. 75, 735–743 (2025).

Lipsky, M. S., Singh, T., Zakeri, G. & Hung, M. Oral health and older adults: a narrative review. Dent. J. 12, 30 (2024).

Azzolino, D. et al. Poor oral health as a determinant of malnutrition and sarcopenia. Nutrients 11, 2898 (2019).

Ye, X. et al. Causal effects of Circulating inflammatory proteins on oral phenotypes: Deciphering immune-mediated profiles in the host-oral axis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 144, 113642 (2025).

Tada, A. & Miura, H. The impact of the number of remaining teeth on the risk of frailty: A meta-analysis. Odontology https://doi.org/10.1007/s10266-025-01154-w (2025).

Sonnega, A. et al. Cohort profile: the health and retirement study (HRS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 576–585 (2014).

Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Smith, J. P., Strauss, J. & Yang, G. Cohort profile: the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Int. J. Epidemiol. 43, 61–68 (2014).

Steptoe, A., Breeze, E., Banks, J. & Nazroo, J. Cohort profile: the english longitudinal study of ageing. Int. J. Epidemiol. 42, 1640–1648 (2013).

Huang, H., Ni, L., Zhang, L., Zhou, J. & Peng, B. Longitudinal association between frailty and pain in three prospective cohorts of older population. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 29, 100537 (2025).

Zhang, J., Xu, G. & Xu, L. Number of teeth and denture use are associated with frailty among Chinese older adults: A cohort study based on the CLHLS from 2008 to 2018. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 27, 972–979 (2023).

Diaz-Toro, F. et al. Association between poor oral health and frailty in middle-aged and older individuals: A cross-sectional National study. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 26, 987–993 (2022).

Ramsay, S. E. et al. Influenceof poor oral health on physical frailty: A population-based cohort study of older British men. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 66, 473–479 (2018).

Huang, J., Zhang, Y., Xv, M., Sun, L. & Wang, M. Association between oral health status and frailty in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public. Health. 13, 1514623 (2025).

Zhang, X. M., Cao, S., Teng, L., Xie, X. & Wu, X. The association between the number of teeth and frailty among older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 37, 156 (2025).

Fierro-Marrero, J., Reina-Varona, Á. & Paris-Alemany, A. La Touche, R. Frailty in geriatrics: A critical review with content analysis of instruments, overlapping constructs, and challenges in diagnosis and prognostic precision. JCM 14, 1808 (2025).

Zhang, Z. et al. Frailty and depressive symptoms in relation to cardiovascular disease risk in middle-aged and older adults. Nat. Commun. 16, 6008 (2025).

Luo, B. et al. Machine learning-driven programmed cell death signature for prognosis and drug candidate discovery in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Multi-cohort study and experimental validation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 162, 115157 (2025).

He, D. et al. Changes in frailty and incident cardiovascular disease in three prospective cohorts. Eur. Heart J. 45, 1058–1068 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Explaining the association between number of teeth and frailty in older Chinese adults: the chain mediating effect of nutritional status and cognitive function. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 31, e70001 (2025).

Sallam, A. et al. The impact of dietary intake and nutritional status on the oral health of older adults living in care homes: a scoping review. Gerodontology https://doi.org/10.1111/ger.12821 (2025).

Yin, H. et al. The association between a dietary index for the gut microbiota and frailty in older adults: emphasising the mediating role of inflammatory indicators. Front. Nutr. 12, 1562278 (2025).

Hajek, A., Kretzler, B. & König, H. H. Oral health, loneliness and social isolation. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 26, 675–680 (2022).

Głuszek-Osuch, M., Cieśla, E. & Suliga, E. Relationship between the number of lost teeth and the occurrence of depressive symptoms in middle-aged adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 24, 559 (2024).

Kase, Y. et al. Multi-organ frailty is enhanced by periodontitis-induced inflammaging. Inflamm. Regen. 45, 3 (2025).

Ye, X. et al. Genetic associations between Circulating immune cells and periodontitis highlight the prospect of systemic immunoregulation in periodontal care. Elife 12, RP92895 (2024).

Clark, D., Kotronia, E. & Ramsay, S. E. Frailty, aging, and periodontal disease: basic biologic considerations. Periodontol 2000. 87, 143–156 (2021).

Ishii, M. et al. Influence of oral health on frailty in patients with type 2 diabetes aged 75 years or older. BMC Geriatr. 22, 145 (2022).

Chan, A. K. Diet, nutrition, and oral health in older adults: A review of the literature. Dentistry J. 11, 222 (2023).

Matsui, D. et al. Validity of self-reported number of teeth and oral health variables. BMC Oral Health. 17, 17 (2017).

Agustanti, A. et al. Validation of self-reported oral health among Indonesian adolescents. BMC Oral Health. 21, 586 (2021).

Machado, V. et al. Self-reported measures of periodontitis in a Portuguese population: A validation study. JPM 12, 1315 (2022).

Kapila, Y. L. Oral health’s inextricable connection to systemic health: special populations bring to bear multimodal relationships and factors connecting periodontal disease to systemic diseases and conditions. Periodontology 2000. 87, 11–16 (2021).

Borges, G. A. et al. Prognosis of removable complete dentures considering the level of mandibular residual ridge resorption: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Invest. 29, 307 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the efforts of the research teams responsible for the design and maintenance of the CHARLS, ELSA, and HRS studies, as well as all participants who contributed their time and information.

Funding

General project of the Traditional Chinese Medicine Administration of Zhejiang Province (2016ZA134); Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Health Science and Technology Project (No. 2026787060).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jun He conceived and designed the study; Jun He and Xun Xie conducted the data analysis and interpretation; Jun He and Ying Wang drafted the manuscript; Ying Wang supervised the study and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent statement

Ethical approval and informed consent were obtained from all participants in the three cohort studies. The CHARLS was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University, the ELSA by the London Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee, and the HRS by the University of Michigan Health Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

He, J., Xie, X. & Wang, Y. Multi-cohort evidence linking edentulism to frailty among older adults. Sci Rep 15, 43768 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27516-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27516-6