Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death worldwide, with rising mortality rates. This study aimed to identify serologic or blood markers associated with mortality prediction in patients with COPD. We analyzed 10-year follow-up cohort data from the Korea COPD Subgroup Study, which included patients from 54 university hospitals in South Korea. Baseline characteristics and blood samples were collected at enrollment. Data on all-cause mortality and death dates were retrieved from the National Health Information System as of June 11, 2024. Among 1,878 patients with COPD, 309 (16.5%) died over the 10-year follow-up period. Multiple Cox regression analysis identified hemoglobin (hazard ratio [HR], 0.879; P < 0.001), hematocrit (HR, 0.955; P < 0.001), basophils (HR, 0.655; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.472–0.908; P = 0.011), creatine (HR, 1.181; P = 0.038), albumin (HR, 0.465; 95% CI, 0.362–0.599; P < 0.001), and blood urea nitrogen (HR, 1.017; P = 0.046) as significant prognostic factors for mortality. Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated significant differences in survival probability based on albumin (cut-off 3.4 g/dL and 4.35 g/dL), basophils (cut-off 2%), and albumin*basophils levels (all P < 0.001). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis revealed that low albumin levels (area under curve [AUC] = 76.2; P < 0.001), low basophil levels (AUC = 71.8; P = 0.030), and low albumin*basophil levels (AUC = 72.2; P = 0.011) were significant predictors of mortality. Proportional HR was significantly associated with these three markers in a linear manner (all P < 0.001). These findings suggest that low serum albumin and blood basophil levels are independent predictors of 10-year mortality in patients with COPD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death worldwide, and COPD-related mortality rates are increasing1. Previous studies have found that patients with COPD who have severe symptoms, reduced exercise capacity, and impaired lung function face a greater risk of mortality. However, tests used to assess these factors typically require patient effort and cooperation. The results of these tests are influenced by the inspectors and patients. Identifying additional predictive factors for mortality in patients with COPD could enhance management strategies and patient education. Serologic and blood markers are objective tools that can be easily obtained and widely used in patients with COPD, as they are independent of inspector- and patient-related variability.

Albumin, the most abundant circulating protein in the blood, possesses anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. It is also widely recognized as a biochemical marker of nutritional status. Numerous studies have shown that serum albumin levels serve as an independent predictor of mortality risk and can be applied across a broad spectrum of clinical conditions to predict mortality, including renal disease, post-operative recovery, and critical illness2. Studies have revealed that low serum albumin levels predict mortality in acutely critically ill patients with COPD3. Recent studies further indicate that low albumin levels may be a predictive factor for long-term mortality in patients with COPD45.

Basophils originate in the bone marrow, developing from hematopoietic stem cells6. They are the rarest leukocytes in human peripheral blood and share several similarities with mast cells. They play a role in maintaining homeostasis and contribute to pathological processes in multiple tissues and organs, including the skin and lungs7. The activation and functions of basophils are facilitated by diverse stimuli such as stress, specific cytokine, and inflammation. Once activated, they release of potent mediators, including proteases, histamine, prostaglandins, and proinflammatory cytokines (particulary those associated with type 2 immune responses-associated mediators)8. The role of basophil in atopic dermatitis and asthma is well established, reflecting their importance in allergic and immune regulation9. Recent study have showed protective role of basophils in helminth-induced lung injury10. Conversely, basopenia can occur in chronic inflammatory disease, including autoimmune chronic spontaneous urticaria11. Glucocorticoid exposure also reduces circulating basophil level12. Several reports have suggested prognostic implications of basophil counts across diseases. Some studies have shown that a high blood basophil count is associated with an increased risk of mortality in various diseases1314. However, other studies have indicated that a low blood basophil count is associated with poor clinical prognoses1516. Especially, the absence of circulating basophil predicts poor prognosis and indicates immunosuppression in severe septic patients17. However, the relationship between basophil levels and mortality or disease prognosis has not been well established.

In particular, their role in COPD have rarely been investigated. Wei et al. reported that low basophil levels were significantly correlated with COPD severity, and served as an independent predictor for exacerbation18. However, one murine study demonstrated that basophil activation may contribute to emphysema development19. In addition, some studies have reported no significant association basophil levels and prognosis of COPD20. Further studies are needed to reveal association with level of basophil and prognosis of COPD.

Utilizing the largest cohort of patients with COPD in Korea, this study aimed to identify serologic and blood markers predictive of mortality (focused on albumin and baslophils) in these patients.

Methods

Ethics

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gangnam Severance Hospital (approval number: 3–2024-0395),and the requirement for patient informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Gangnam Severance Hospital due to the retrospective nature of the study. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Participants

We analyzed 10-year follow-up data from the Korean COPD Subgroup Study (KOCOSS), a cohort established in 2005 that includes patients from 54 university hospitals across South Korea. The KOCOSS cohort prospectively recruited patients with stable COPD from outpatient clinics. Inclusion criteria were: (1) a COPD diagnosis confirmed by a pulmonologist, (2) age ≥ 40 years, (3) symptoms, such as cough, sputum, or dyspnea, and (4) a post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio < 70%. Exclusion criteria were: COPD patients with missing data of serologic, blood markers and/or survival. Baseline clinical characteristics were recorded at the time of enrollment. Serologic and blood markers were measured on the day of enrollment. On the enrollment day, patients were clinically stable. We used cut-off values of 3.4 g/dL for albumin and 2% for basophil, which correspond to the lower limits (for albumin) and upper limits (for basophil) of their most widely used normal ranges21. Additional albumin cut-off value (4.35 g/dL) determined using the proportional HR curve.

Study scheme

The KOCOSS cohort consisted of 3,476 patients. We excluded 1,598 individuals who lacked serologic or blood markers and survival data. The remaining 1,878 patients were included in this study (Fig. 1).

Self-reported survey

A history of tuberculosis (TB), smoking status, and residential area were assessed using self-reported surveys. Participants responded “yes” or “no” to the question, “Have you ever had pulmonary tuberculosis?” Smoking status was classified as never smoked, ever smoked, or current smoker based on self-reported “yes” or “no” responses to the questions, “Have you ever smoked?” and “Do you currently smoke?”

Pulmonary function test

Pulmonary function tests were performed while patients were in stable condition, and the most recent results within 1 year of enrollment were used. Spirometry was performed following the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines2223. The absolute values of FEV1 and FVC were recorded. Predicted values for these parameters were calculated using Choi’s equation, predominantly used in Korea24.

Respiratory symptoms and quality of life

The modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Dyspnea Scale was used to assess dyspnea, where higher scores indicated greater severity25. The COPD Assessment Test (CAT) evaluated COPD symptoms through an 8-item questionnaire, with each item scored from 0 to 5, where higher scores indicated greater symptom severity26. The St. George’s respiratory questionnaire for COPD patients (SGRQ-C) total score assessed quality of life using a 14-item questionnaire that covered three components: symptoms, activities, and impact. The total score, calculated using the SGRQ-C algorithm27, reflected a poorer quality of life at higher values. These are measured on the day of enrollment.

Six-minute walk test

The six-minute walk test was conducted to assess exercise capacity following the standardized protocol28. Patients rested for at least 10 min before beginning the test. After 6 min, the total distance walked was measured and recorded. The six-miniute walk test was performed in stable condition, and the most recent results within 1 year of enrollment were used.

History of previous exacerbations and Charlson comorbidity index (CCI)

A history of previous exacerbations was determined using self-reported surveys, in which participants responded “yes” or “no” to the question, “Have you ever experienced a COPD exacerbation in the past year?” Medical records were reviewed to validate these responses, ensuring accuracy through a cross-verification process. The CCI, a tool for predicting prognosis and mortality, was calculated as previously described2930.

Mortality and date of death

Data on all-cause mortality and date of death were obtained from the National Health Information System (NHIS) on June 11, 2024. Survival time was calculated as the period between the date of consent and either the date of death or June 11, 2024, for survivors. The 10-year survival rate was also assessed. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation or percentage. Cox regression analyses were performed to identify mortality predictors. Multiple imputations were used to address missing data for CCI, the 6-minute walk test, and history of exacerbations (with 10 imputations performed). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to compare survival probabilities based on marker levels, and differences between groups were assessed using the log-rank test. Time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve estimation suitable for a survival setting was conducted. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 21.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA) and R software (version 4.2.2; http://www.R-project.org).

Results

Baseline characteristics of enrolled patients

Among 1,878 patients with COPD, 309 patients (16.5%) had died after a 10-year follow-up. The mean age was 68.8 years, and males were predominant (92.3%). A history of TB was reported in 22.7% of patients. Never smokers, ever smokers, and current smokers accounted for 10.5%, 63.6%, and 25.9%, respectively. The mean predicted values for FVC (%), FEV1 (%), and the FEV1/FVC ratio were 79.5%, 58.4%, and 51.7%, respectively. The mean mMRC score was 1.2. The total distance in the 6-minute walk test was 385.7 m (missing number = 436). A history of COPD exacerbation in the previous year was reported in 17.6% of patients (missing number = 737) (Table 1).

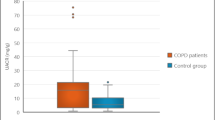

Serologic and blood markers obtained in this study

Various serologic and blood markers were obtained at the time of enrollment. The number of missing values and the minimum, maximum and mean values are described in Table 2. The mean basophil level (%) was 0.7 (missing number = 51), and the mean albumin level was 4.4 (missing number = 161) (Table 2).

Cox regression analysis for mortality

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses, adjusted for age, sex, smoking status, TB history, body mass index (BMI), FEV1, and mMRC, showed that hemoglobin, hematocrit, neutrophils, lymphocytes, basophils, creatine, albumin, and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) were significant predictors of mortality. After adjusting for additional factors, including the CCI, 6-minute walk test, and a history of exacerbations (using multiple imputation analyses), hemoglobin (hazard ratio [HR], 0.879; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.817–0.946; P < 0.001), hematocrit (HR, 0.955; 95% CI, 0.931–0.979; P < 0.001), basophils (HR, 0.655; 95% CI, 0.472–0.908; P = 0.011), creatine (HR, 1.181; 95% CI, 1.009–1.383; P = 0.038), albumin (HR, 0.465; 95% CI, 0.362–0.599; P < 0.001), and BUN (HR, 1.017, 95% CI, 1.000–1.033; P = 0.046) were significant predictors of mortality (Table 3).

Survival probability according to serum albumin, blood basophils, and albumin*basophils

We selected the most powerful predictors among the above markers: albumin and basophils. We classified participants based on marker cut-off values, including the lowest limit of the normal range (3.4 g/dL for albumin) and the upper limit of the normal range (2% for basophils) and an additional albumin cut-off value (4.35 g/dL) determined using the proportional HR curve. The cut-off value for albumin*basophils (6.8) was calculated by multiplying the previously mentioned values. The Kaplan–Meier graph showed a significant difference according to the levels of the three markers (all P < 0.001). Lower marker levels were associated with a higher mortality risk (Fig. 2).

ROC curve to predict mortality

ROC curves revealed that low albumin levels (ROC at time t = 365.25; area under curve [AUC] = 76.2; P < 0.001), low basophil levels (ROC at time t = 365.25; AUC = 71.8; P = 0.030), and low albumin*basophil levels (ROC at time t = 365.25; AUC = 72.2; P = 0.011) were significant predictors of mortality (Fig. 3).

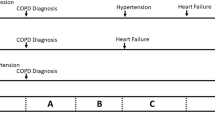

Proportional hazard ratio curve for mortality

HRs were significantly associated with serum albumin, blood basophil, and albumin*basophil levels in a linear manner (all P < 0.001). The threshold values for the three markers in the HR curve were 4.35, 0.65, and 2.98, respectively. The mortality rate was lower if marker levels were higher than the cut-off. Conversely, lower marker levels were associated with an increased mortality risk (Fig. 4).

Hazard ratio curve for mortality based on serum albumin (A), blood basophil (B), and albumin*basophil (C) TB, tuberculosis; CXR, chest X-ray; BMI, body mass index; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; SGRQ-C, St. George’s respiratory questionnaire for COPD patients; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

This large Korean COPD cohort study revealed that albumin and basophil levels could be independent prognostic factors predicting 10-year mortality in patients with COPD. Several other predictive factors for mortality were identified in this study. Among these factors, albumin and basophil showed superior predictive power compared to others. Low levels of albumin (< 3.4 g/dL) outside normal range and normal range of basophils (< 2%) were associated with a lower survival probability than other levels. Their predictive performance for mortality was acceptable (AUC: 71.8–76.2). The proportional HR graph for mortality showed a clear and linear correlation with their levels. These simple serologic or blood markers can indicate the 10-year survival probability in patients with COPD.

Table 3 presents several predictive factors for mortality. Anemia, characterized by chronically low levels of circulating hemoglobin and/or hematocrit, can exacerbate dyspnea and reduce exercise tolerance in COPD. Previous studies have shown that low hemoglobin and hematocrit are poor prognostic factors in COPD3132. BUN and creatinine are well-established markers of renal function. Elevated levels of these markers indicate renal impairment. Previous studies have demonstrated the adverse impact of renal disease on COPD prognosis, including an increased risk of mortality3334. We also confirmed that hemoglobin, hematocrit, BUN, and creatinine levels are predictive factors for mortality in COPD. However, their association with mortality appears weaker (HR, 0.879–1.181) compared to that of albumin (HR, 0.465) and basophils (HR, 0.655). Then, we further investigated these two factors.

This study confirmed that patients with COPD and serum albumin and/or blood basophil levels below the normal range had a lower survival probability than others. To compare survival probability based on marker levels, we used cutoff values of 3.4 g/dL for albumin and 2% for basophils, corresponding to the lower limit and upper limit of their most widely used normal ranges. The value of 6.8 for albumin*basophil was obtained by multiplying 3.4 g/dL by 2%. Although albumin was within the normal range, a significant difference in mortality was observed when patients were stratified using a cutoff of 4.35 g/dL, which was derived from the proportional HR curve in Fig. 3. Akirovo et al.. found that patients with hyperalbuminemia (> 4.5 mg/dL) had a higher survival rate than those with normal albuminemia (3.5–4.5 g/dL) and hypoalbuminemia (< 3.5 mg/dL) during hospitalization35. Thongprayoon et al.. reported significant differences in HR for mortality across detailed albumin subgroups (HR 8.10 for albumin < 2.4 g/dL, HR 3.69 for albumin 2.5–2.9 g/dL, HR 2.90 for albumin 3.0–3.4 g/dL, HR 2.53 for albumin 3.5–3.9 g/dL, and HR 0.75 for albumin > 4.5 g/dL, compared to albumin 4.0–4.4 g/dL)36. Although albumin levels fall within the normal range, higher levels are associated with better prognosis.

Basophils play a pathogenetic role in allergic, inflammatory, and autoimmune disorders37. Therefore active inflammatory status may elevate basophil count. Then, all blood samples in this study were collected when patients were clinically stable to minimize bias. Although prior studies have examined the association between basophil levels and COPD, definitive conclusions remain elusive. We speculate that relatively low basophil levels—even within the normal range—may reflect chronic stress, persistent inflammation, or prolonged glucocorticoid exposure, all of which could adversely affect COPD prognosis and mortality.

We employed additional statistical tools to examine the association between specific markers and mortality. Based on the ROC and AUC analysis, the predictive accuracy of albumin, basophil, and albumin*basophil was deemed acceptable. Generally, an AUC value between 0.7 and 0.8 is considered acceptable. The AUC values for these three markers ranged from 71.8 to 76.2, with all corresponding P-values being statistically significant. We also identified a clear linear correlation between proportional HRs and the markers. The threshold values for albumin, basophil, and albumin*basophil were 4.35, 0.6, and 2.98, respectively. This indicates that patients with COPD and albumin levels above 4.35 g/dL exhibit a lower mortality rate than those with levels at or below 4.35 g/dL. Lower marker levels are associated with higher mortality rates, whereas higher marker levels correspond to lower mortality rates.

We adjusted many parameters that are well-established factors affecting survival in COPD. Age and sex are inherited factors that influence the prognosis of COPD38. Patients with COPD and a history of TB and low BMI generally exhibit a poor prognosis3940. Low lung function, severe symptoms, limited exercise capacity, and a history of COPD exacerbations are also well-established predictive factors for mortality in COPD38. Additionally, the CCI is a strong predictive factor of mortality2930. This study accounted for these parameters to eliminate their confounding effects on mortality. After adjustment, we confirmed that albumin and basophil levels are independent mortality predictors.

Many predictive factors for mortality in COPD exist. However, many of these are inherited, heavily influenced by the patient’s subjective assessment, or require patient cooperation. In contrast, serologic and blood markers are objective parameters that can be measured with high precision using specialized equipment. These tests can be performed at any time, even in cases where patient cooperation is limited or the patient is mentally unstable. By simply measuring blood levels of albumin and basophils, we can predict 10-year mortality rates. We also used albumin*basophil as a predictive factor. This variable is not generated based on the pathophysiological relationship between the two values. It’s artificially created variable to define whether it serves as a better predictor of mortality. However, we speculated this new variable might represent systemic catabolic and chronic inflammatory burden.These prognostic predictions could provide significant clinical value in treating and educating patients with COPD.

This study has some limitations. First, several parameters—including CCI, history of exacerbations, and exercise capacity—had substantial missing data. We performed multiple imputation analyses to address this limitation. Second, we obtained blood samples only once at the time of enrollment. Repeated sampling may provide additional insights. Third, we analyzed all-cause mortality rather than COPD-specific mortality. Fourth, we could not adjust for medication history, which may affect COPD prognosis, due to variability in drug type, dosage, and duration. Fifth, AUCs (0.72–0.76) indicate acceptable yet modest discrimination suggesting potential benefit to find out multi-marker panel to improve predictive performance. Finally, further studies are needed to determine mechanism how basophil affect COPD mortality and whether supplementation with albumin or basophil-stimulating therapies could improve mortality outcomes. In addition, external validation in an independent COPD cohort will be helpful to confirm generalizability of potential roles of these biomarkers.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this large COPD cohort study in Korea employed multiple statistical tools and found that low serum albumin and blood basophil levels can be independent predictive factors for 10-year mortality in COPD patients.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CAT:

-

COPD assessment test

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- COPD:

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CXR:

-

chest X-ray

- FEV1 :

-

forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC:

-

forced vital capacity

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- KOCOSS:

-

Korea COPD Subgroup Study

- mMRC:

-

modified Medical Research Council dyspnea scale

- SGRQ-C:

-

St. George’s respiratory questionnaire for COPD patients

- TB:

-

tuberculosis

- WBC:

-

white blood cell

- ESR:

-

erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- AST:

-

aspartate aminotransferase

- ALT:

-

alanine aminotransferase

- ALP:

-

alkaline phosphatase

- BUN:

-

blood urea nitrogen

- NT-proBNP:

-

N-terminal pro-brain-natriuretic peptide

- ROC:

-

receiver operating characteristic

- AUC:

-

area under curve

- CCI:

-

Charlson comorbidity Index

- BMI:

-

body mass index

References Reference number 2 should be corrected. Reference number 1 and 2 are one reference. The reference number 3 is actually reference number 2.

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD. http://goldcopd.org. Date last accessed: 23 November 2024. (2023).

Papaioannou, A. I. et al. Mortality prevention as the centre of COPD management. ERJ Open. Res. 10 (3). https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00850-2023 (2024). [published Online First: 20240617].

Konigsbrugge, O. et al. Association between decreased serum albumin with risk of venous thromboembolism and mortality in cancer patients. Oncologist 21 (2), 252–257. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0284 (2016). [published Online First: 20160113].

Wang, Q. et al. Inflammatory markers as predictors of in-hospital mortality in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) patients with acute respiratory failure: insights from the MIMIC-IV database. J. Thorac. Dis. 16 (12), 8250–8261. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-24-1287 (2024). [published Online First: 20241216].

Shen, S., Xiao, Y., Association Between, C-R. & Protein Albumin ratios and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 18, 2289–2303. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S413912 (2023). [published Online First: 20231018].

Lan, C. C. et al. Predictive role of neutrophil-percentage-to-albumin, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratios for mortality in patients with COPD: evidence from NHANES 2011–2018. Respirology 28 (12), 1136–1146. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.14589 (2023). [published Online First: 20230901].

Drissen, R. et al. Distinct myeloid progenitor-differentiation pathways identified through single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat. Immunol. 17 (6), 666–676. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3412 (2016). [published Online First: 20160404].

Chen, Y. et al. Basophil differentiation, heterogeneity, and functional implications. Trends Immunol. 45 (7), 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2024.05.009 (2024). [published Online First: 20240628].

Chen, K. et al. Antibody-mediated regulation of basophils: emerging views and clinical implications. Trends Immunol. 44 (6), 408–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2023.04.003 (2023). [published Online First: 20230503].

Hammad, H. & Lambrecht, B. N. The basic immunology of asthma. Cell 184 (9), 2521–2522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.019 (2021).

Bird, L. Basophils balance ILC2s. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20 (10), 592–593. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-020-00437-3 (2020).

Larenas-Linnemann, D. Biomarkers of autoimmune chronic spontaneous urticaria. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 23 (12), 655–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-023-01117-7 (2023). [published Online First: 20231208].

Jia, W. Y. & Zhang, J. J. Effects of glucocorticoids on leukocytes: genomic and non-genomic mechanisms. World J. Clin. Cases. 10 (21), 7187–7194. https://doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i21.7187 (2022).

Pizzolo, F. et al. Basophil blood cell count is associated with enhanced factor II plasma coagulant activity and increased risk of mortality in patients with stable coronary artery disease: not only neutrophils as prognostic marker in ischemic heart disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 10 (5), e018243. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.018243 (2021). [published Online First: 20210224].

Lucijanic, M. et al. High absolute basophil count is a powerful independent predictor of inferior overall survival in patients with primary myelofibrosis. Hematology 23 (4), 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/10245332.2017.1376843 (2018). [published Online First: 20170914].

Kawano, M. et al. Association of Circulating basophil count with gastric cancer prognosis. J. Gastrointest. Cancer. 56 (1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-025-01171-6 (2025). [published Online First: 20250127].

Yang, C. et al. Prognostic value of platelet-to-basophil ratio (PBR) in patients with primary glioblastoma. Med. (Baltim). 102 (30), e34506. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000034506 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Basophils absence predicts poor prognosis and indicates immunosuppression of patients in intensive care units. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 18533. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-45865-y (2023). [published Online First: 20231028].

Xiong, W. et al. Can we predict the prognosis of COPD with a routine blood test? Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 12, 615–625. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S124041 (2017). [published Online First: 20170213].

Shibata, S. et al. Basophils trigger emphysema development in a murine model of COPD through IL-4-mediated generation of MMP-12-producing macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 115 (51), 13057–13062. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1813927115 (2018). [published Online First: 20181203].

Zhu, Y. et al. Development and validation of the machine learning model for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prediction based on inflammatory biomarkers. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 12, 1616712. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2025.1616712 (2025). [published Online First: 20250801].

Sonder, S. U. et al. Towards standardizing basophil identification by flow cytometry. Front. Allergy. 4, 1133378. https://doi.org/10.3389/falgy.2023.1133378 (2023). [published Online First: 20230303].

American Thoracic Society. Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 update. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 152 (3), 1107–1136. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792 (1995).

Miller, M. R. et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur. Respir J. 26 (2), 319–338. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 (2005).

Choi, J. K., Paek, D. & Lee, J. O. Normal predictive values of spirometry in Korean population. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 58 (3), 230–242 (2005).

Bestall, J. C. et al. Usefulness of the medical research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 54 (7), 581–586. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.54.7.581 (1999).

Jones, P. W. et al. Development and first validation of the COPD assessment test. Eur. Respir J. 34 (3), 648–654. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00102509 (2009).

Meguro, M. et al. Development and validation of an Improved, COPD-Specific version of the St. George respiratory questionnaire. Chest 132 (2), 456–463. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.06-0702 (2007). [published Online First: 20070723].

Laboratories ATSCoPSfCPF. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 166 (1), 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102 (2002).

Charlson, M. E. et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 40 (5), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 (1987).

Song, S. E. et al. The prognostic value of the charlson’s comorbidity index in patients with prolonged acute mechanical ventilation: A single center experience. Tuberc Respir Dis. (Seoul). 79 (4), 289–294. https://doi.org/10.4046/trd.2016.79.4.289 (2016). [published Online First: 20161005].

Koc, C. & Sahin, F. What are the most effective factors in determining future Exacerbations, morbidity Weight, and mortality in patients with COPD attack? Med. (Kaunas). 58 (2). https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58020163 (2022). [published Online First: 20220121].

Similowski, T. et al. The potential impact of anaemia of chronic disease in COPD. Eur. Respir J. 27 (2), 390–396. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.06.00143704 (2006).

Liu, Z., Ma, Z. & Ding, C. Association between COPD and CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1494291. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1494291 (2024). [published Online First: 20241216].

Zhang, J. et al. Elevated BUN upon admission as a predictor of in-Hospital mortality among patients with acute exacerbation of COPD: A secondary analysis of multicenter cohort study. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 18, 1445–1455. https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S412106 (2023). [published Online First: 20230713].

Akirov, A. et al. Low Albumin Levels Are Associated with Mortality Risk in Hospitalized Patients. Am. J. Med. 130 (12), 1465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.07.020 (2017). [published Online First: 20170809]e11-65 e19.

Thongprayoon, C. et al. Impacts of admission serum albumin levels on short-term and long-term mortality in hospitalized patients. QJM 113 (6), 393–398. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcz305 (2020).

Kabashima, K. et al. Biomarkers for evaluation of mast cell and basophil activation. Immunol. Rev. 282 (1), 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/imr.12639 (2018).

Halpin, D. M. G. Mortality of patients with COPD. Expert Rev. Respir Med. 18 (6), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/17476348.2024.2375416 (2024). [published Online First: 20240730].

Tenda, E. D. et al. The impact of body mass index on mortality in COPD: an updated dose-response meta-analysis. Eur. Respir Rev. 33 (174). https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0261-2023 (2024). [published Online First: 20241127].

Mattila, T. et al. Tuberculosis, Airway Obstruction and Mortality in a Finnish Population. COPD ;14(2):143 – 49. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/15412555.2016.1250253 [published Online First: 20161123].

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a research program funded by the Korea National Institute of Health (Fund Code: 2016ER670100, 2016ER670101, 2016ER670102, 2018ER67100, 2018ER67101, 2018ER67102, 2021ER120500, 2021ER120501, 2021ER120502, and 2024ER120500). Additionally, this study was supported by a faculty research grant from Yonsei University College of Medicine (6-2024-0108).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HJP contributed to Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, and approved the final manuscript. YK, JHA, CYL, DKK, JYM, WYL, and KHY were responsible for Data Curation, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, and approved the final manuscript. YS conducted Formal Analysis, Data Interpretation, and Statistical Analysis. MKB, as the corresponding author, contributed to Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Data Interpretation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, H.J., Song, Y., Kim, Y. et al. Low levels of serum albumin and blood basophils as 10-year mortality predictors in a nationwide Korean COPD cohort. Sci Rep 15, 43924 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27653-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27653-y