Abstract

The rapid growth of renewable energy sources (RES) and the increasing complexity of modern power systems (PSs) have introduced significant challenges for automatic load frequency control (LFC), including large uncertainties, disturbances, and reduced system inertia. These issues limit the effectiveness of conventional control strategies and may threaten system stability and reliability. To address these problems, this paper proposes a novel multi-stage sliding mode control (SMC) scheme integrated with an optimal state estimator (OSE) for LFC in multi-area hybrid PSs (HPSs) consisting of conventional thermal, hydro, and gas units together with battery and flywheel energy storage and renewable sources such as photovoltaic and wind power. The OSE is first designed to provide accurate state feedback under uncertain operating conditions, thereby improving control robustness. Based on these estimates, a new multi-term sliding surface is formulated to ensure fast dynamic response and strong resilience against system uncertainties. The stability of the proposed approach is mathematically validated, and extensive simulations are performed under various load changes, uncertainty scenarios, and communication delay in both isolated and interconnected HPSs. The results demonstrate that the proposed controller outperforms recently developed SMC-based approaches by reducing overshoot and undershoot by up to 46.4%, undershoot by up to 48.1%, and shortening settling time by up to 23.8%, while also eliminating chattering. These improvements highlight the robustness, reliability, and practical applicability of the proposed scheme for future complex PSs with high RES penetration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing integration of renewable energy sources (RES) such as photovoltaic (PV) and wind turbine generators (WTG) has introduced significant challenges to load frequency control (LFC) in modern power systems (PSs). These sources are inherently intermittent and uncertain, often leading to power imbalances and fluctuations in system frequency1,2. To address these issues and enhance grid flexibility, energy storage systems (ESS)—such as battery ESS (BESS) and flywheel ESS (FESS)—have emerged as key enablers for fast-response compensation3,4. At the same time, load demand has become more dynamic, and interconnection between multiple control areas has made LFC tasks more complex and critical. As a result, maintaining stable and reliable LFC in multi-area hybrid PSs (MHPSs) has become a priority in the operation of future smart grids5,6,7.

Over the past decade, diverse control strategies have been developed to address LFC in interconnected PSs. Classical proportional–integral–derivative (PID) controllers and their variants remain widely used due to their simplicity and ease of implementation8,9,10,11,12,13,14. For instance8,9 employed particle swarm optimization (PSO) and its variants to tune PID parameters for LFC in multi-source and islanded microgrids, while11 introduced a fractional-order PID controller optimized using the Aquila Optimizer. A hybrid 1PD-PI controller tuned via the Mountaineering Team-Based Optimization algorithm was proposed in13 for RES-based islanded systems. In14, A dragonfly-optimized tilt derivative–tilt integral derivative controller was proposed for hybrid microgrids, ensuring superior LFC under renewable variability. In15, a Walrus Optimization Algorithm-tuned FO-PID controller was proposed for two-area PS, achieving improvement in LFC, faster convergence and settling time, and enhanced tie-line stability under nonlinearities and disturbances. However, these methods often lack robustness under parameter variations and nonlinearities.

To address these limitations, Fuzzy logic controllers (FLC) and model predictive control (MPC) have been employed to enhance adaptability and constraint handling16,17,18,19,20. For example, in16, a decentralized periodic dynamic event-based FLC was proposed for multiarea nonlinear PSs with uncertainties, using an interval type-2 fuzzy model to reduce communication load while ensuring exponential stability. In18, an adaptive MPC was applied to a MHPSs to handle parameter uncertainties and load disturbances, ensuring minimal steady-state error and outperforming GA-PI, FA-PI, and traditional MPC. While20 introduced a centralized fuzzy-tuned MPC approach for isolated microgrids, where dynamic adjustment of the MPC cost function via fuzzy logic improved LFC compared to fixed-parameter MPC and PI control schemes. In21,22, Harris Hawks Optimization-based MPC schemes are proposed for renewable and deregulated PSs, demonstrating enhanced voltage and frequency stability, faster dynamics, and strong robustness under renewable integration, EV participation, and diverse market scenarios. But their performance heavily depends on model accuracy, and computational complexity increases with system size.

In parallel, artificial intelligence-based approaches, such as neural networks and reinforcement learning, as well as metaheuristic-tuned controllers, have shown promising results in certain scenarios23,24,25,26. Notably24, presented hybrid single-neuron PID controller enhanced by machine learning islanded microgrids. In26, a PSO-trained artificial neural network controller was proposed for LFC in microgrids with vehicle-to-grid integration, demonstrating superior accuracy, fast dynamic response, and improved stability under renewable variability and electric vehicle (EV) charging dynamics. However, these techniques often lack formal stability guarantees and generalization to unseen disturbances.

Among these, sliding mode control (SMC) has emerged as a robust alternative due to its inherent insensitivity to disturbances and modeling uncertainties27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36. For example, a decentralized LFC approach based on integral SMC (ISMC) was proposed in27, where a proportional–integral sliding surface and a reaching law method were employed to handle matched and unmatched uncertainties in a three-area PSs. In28, the ISMC strategy was further enhanced by optimizing controller parameters using a modified PSO algorithm to improve LFC in a multi-area PSs (MAPSs) with RES and EV integration under various dynamic conditions. In29, a decentralized single-phase double ISMC combined with a state observer was proposed to ensure finite-time frequency convergence and reduce chattering in MAPSs with solar integration. Building upon these developments in SMC, recent studies have explored further enhancements using proportional–derivative (PD) sliding surfaces. In30, a PD-based SMC approach was proposed for interconnected PSs, demonstrating improved robustness, reduced overshoot, faster dynamic response, and mitigated chattering compared to conventional SMCs and PID methods. Extending this direction, Huynh et al.31 introduced a PD-based SMC combined with an improved super-twisting algorithm and a reduced-order model to address LFC challenges in MAPSs with renewable energy and energy storage integration, achieving significant gains in dynamic performance and disturbance rejection. Further advancing SMC design, the study in32 introduced a PID-based sliding surface with an LMI-based stability analysis for MAPSs with hydropower, achieving enhanced robustness, reduced chattering, and faster response compared to PI, DPI, and PD-based SMC approaches. Recent efforts have further improved SMC-based frequency regulation by integrating observer structures and advanced optimization techniques. In33, a cascaded extended state observer SMC, combined with a novel osprey–dung beetle fusion algorithm, was proposed for wind–thermal coordinated systems, offering improved robustness, faster frequency response, and reduced emissions. In34, an observer-based decentralized higher-order SMC, tuned via the honey badger algorithm, was developed to minimize chattering and improve control accuracy in MAPSs, outperforming conventional controllers across multiple configurations. Additionally, in35, an event-triggered SMC was proposed for microgrid frequency stabilization, effectively reducing communication and computation burdens while ensuring robustness under disturbances and uncertainties. In36, a Teaching–Learning-based optimization approach is employed to optimally tune SMC parameters in microgrids, yielding improved frequency stability compared with several nature-inspired methods and demonstrating strong resilience against nonlinearities and parameter variations. However, most existing SMC-based designs assume full-state availability, which is impractical in real-world systems where only partial and noisy measurements are available27,28,29,30,31,32. While a few works have introduced basic observers for state estimation, these are rarely optimized or tightly integrated within the control structure29,33,34. Moreover, classical SMC schemes often focus on low-order or single-area systems and suffer from the chattering phenomenon, which can cause actuator wear and degraded performance. Furthermore, limited attention has been given to coordinated control in MAPSs with high RES penetration and ESS integration. These limitations reveal a clear gap: existing SMC-based LFC schemes are not fully suitable for realistic MHPSs that integrate RES, ESS, and inter-area dynamics. In practice, system states are only partially measurable and corrupted by noise, making state estimation essential. Furthermore, a practical controller must ensure chattering-free performance while maintaining robustness against matched uncertainties and renewable intermittency. Therefore, there is a pressing need for a unified framework that combines an advanced SMC design with an optimal observer to deliver accurate state estimation, robust LFC, and smooth control action in large-scale renewable-integrated MHPSs. Table 1 provides a comparative summary of existing SMC-based approaches for LFC in PSs, highlighting the type of controller, the adopted sliding surfaces, sensor requirements, and system models, thereby giving a comprehensive view of their design features, strengths, and limitations

To address this need, this paper proposes a novel LFC strategy that combines a multi-stage SMC with an optimal state estimator (OSE). The OSE is designed using Riccati function to produce accurate, noise-resilient state estimates in real time, even under parameter variations and limited measurements. These estimates are then used to construct a multi-stage sliding surface, which enables fast convergence, strong disturbance rejection, and elimination of chattering effects. The control structure incorporates both an equivalent control term to keep the system on the sliding surface and a switching control term to reject disturbances and uncertainties. The entire framework is formulated to operate in a realistic MHPS that includes three different conventional generators, RES units (PV, WTG), ESSs (BESS, FESS), local load variations, and tie-line coordination between regions.

The main contribution of this paper is summarized as follows:

-

Development of a comprehensive MHPS model: A detailed MHPS model is developed, incorporating conventional sources, RES, ESS, tie-line dynamics, and load variations, thus providing a realistic testbed for LFC design.

-

Design of an OSE: An observer-based estimator is developed using a Riccati design to provide robust and noise-resilient state estimation under partial observability, thereby enhancing the practicality and reliability of SMC-based LFC.

-

Proposal of a multi-stage SMC scheme: A novel multi-stage SMC structure is proposed, which leverages OSE-estimated states to ensure fast convergence, strong disturbance rejection, and effective mitigation of chattering in large-scale systems.

-

Extensive validation: The proposed controller is rigorously assessed under diverse operating conditions, demonstrating superior robustness, reduced overshoot/undershoot, shorter settling time, and smoother control action compared with recently published SMC schemes.

The remainder of the paper is listed as follows: Section II describes the modeling of the MHPSs, including detailed frequency response dynamics that incorporate conventional generators, RESs, ESSs, and inter-area tie-lines. Section III presents the proposed control approach, in which an OSE is designed and integrated into a novel multi-stage SMC framework. Section IV discusses the simulation results under various operating conditions to evaluate the effectiveness, robustness, and superiority of the proposed method compared to existing control strategies.

MPS frequency response model

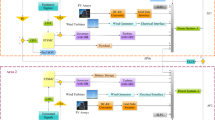

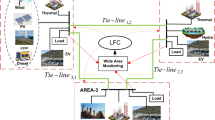

To illustrate the increasing complexity of modern PSs with high RES penetration, a new and practical MHPS model is developed as shown in Fig. 1. Each region includes conventional generators (reheat thermal, hydropower and gas thermal power plants), RESs (photovoltaic, wind power), and fast-response ESSs (battery, flywheel), reflecting a realistic mix of generation technologies. Local load demands are considered to capture actual system behavior. Interregional tie-lines enable power exchange between areas, while communication links facilitate coordinated control actions. The model represents practical operating conditions in modern PSs, including RES variability, system uncertainties, and inter-area interactions. The diversity of sources and inclusion of storage technologies enhance system flexibility and enable more accurate evaluation of control methods under dynamic conditions.

Furthermore, the inclusion of RES highlights critical challenges for LFC. The intermittent and weather-dependent nature of RES introduces considerable uncertainty and variability, while the predominance of inverter-based generation reduces overall system inertia, leading to larger and faster frequency deviations. These factors significantly increase the difficulty of achieving reliable and stable LFC. Therefore, the developed MHPS model not only provides a realistic testbed but also captures the pressing need for robust and resilient control strategies capable of handling high levels of RES penetration in modern MAPSs.

To capture the frequency dynamics of each area within the MHPSs, a detailed LFC model is developed, in which the aggregated effects of generation, storage, and load-side interactions are represented through transfer functions and dynamic equations. These models reflect the combined influence of control signals, system inertia, and inter-area power exchanges, and play a vital role in determining the overall frequency response and reliability. As shown in Fig. 2, the dynamic behavior of the xth control area can be formulated as follows:

where N is total number of areas.

Remark 1

In an isolated PS, there are no tie-line interconnections with other areas, which implies that the tie-line power deviation term vanishes in Eq. (13) (\(\Delta {P_{tie,xy}}=0\)). As a result, the ACE expression reduces to a form that depends solely on the local frequency deviation in Eq. (12) (\(AC{E_x}={\beta _x}\Delta {F_x}\)). This clearly indicates that, under isolated operating conditions, the evolution of ACE signal is governed solely by the frequency deviation, meaning that ACE dynamics are directly proportional to (\(\Delta {F_x}\)).

According to Eqs. (1)–(13), the state space model can be defined in state-space form

where \({z_x} \in {R^n}\)is the state vector of xth area and \({z_y} \in {R^n}\) is the state vector of neighboring control areas. Then, the SSVs of MHPS are given as below.

where.

From the above differential equations, we can determine the system matrices \({A_x},\,{B_x},\,{C_x}\) and \({D_x}\) under work as follows:

where.

and.

In practical MHPSs, system uncertainties and external disturbances are inevitable due to time-varying dynamics, parameter fluctuations, and nonlinear interactions among components. These may stem from variations in generator operating conditions, actuator delays, or unmodeled dynamics in turbine and governor systems. Additionally, control-induced effects such as chattering can introduce further instability. To account for these factors, the uncertainties are embedded into the system model through time-dependent perturbations in the state-space matrices and control input, as described below:

where \(\Delta {A_x}({z_x},t)\)is the time-varying parameter uncertainty in the state matrix; \(\Delta {H_{xy}}({z_y},t)\) is the interconnected matrix’s time varying parameter uncertainty; and \(\Delta {B_x}({z_x},t)\) is the disturbance input. Then, the global uncertainties of MHPSs can be presented as follows:

Then, dynamic state-space form of Eq. (15) can be re-written to:

where \({\theta _x}(t)\) is measurement disturbances.

An assumption is made and formulated coupled with a given Lemma in order to handle the aggregate uncertainties for the ALFC of MHPS as follows:

Assumption 1

It is assumed that aggregate uncertainties (17) are bounded. There exist positive scalars \({\varepsilon _x}\), such that be restricted \(\left\| {{N_x}({z_x},t)} \right\| \leqslant {\varepsilon _x}\). Then, total uncertainties within predefined acceptable limits to ensure that load disturbance, match and mismatch uncertainties do not exceed the allowable value.

Before ending this part, two important lemmas are presented to describe the stability and feasibility of the MHPS-based LFC strategies under certain conditions in the following section.

Design of a novel multi-stage SMC with OSE

In this section, a novel control structure is developed by combining a multi-stage SMC with an OSE. This hybrid design aims to improve the robustness and performance of LFC in MHPSs, which are characterized by uncertainties and external disturbances. The optimal state estimator provides accurate state information, even in the presence of various disturbances and parameter uncertainties, while the multi-stage SMC ensures fast convergence and high disturbance rejection. The following subsections present the design of the OSE and the structure of the proposed SMC based on the estimated states.

An OSE design

To enhance control performance in the presence of system uncertainties and external disturbances, an OSE is developed using a traditional observer structure. The estimator gain is determined through Riccati function, ensuring an optimal balance between estimation accuracy and robustness. By providing reliable state feedback, the designed estimator improves the effectiveness of the SMC scheme and contributes to overall system stability and dynamic response.

From state-space form of MHPSs in Eq. (17), the system disturbances \({N_x}({z_x},t)\) and measurement disturbances \({\theta _x}(t)\) is zero and their covariance matrices are respectively \({P_{SE}}\) and \({Q_{SE}}\) as follows:

The performance index of OSE is presented in following equation:

where \({\tilde {z}_x}(t)={z_x}(t) - {\hat {z}_x}(t)\) and \({\hat {z}_x}(t)\) denotes the estimated state obtained from \({z_x}(t)\).

Then, the OSE state-space form is structured as follows:

where \({\hat {z}_x}(t)\) is estimated state variable; \({L_x} \in {R^{13 \times 13}}\) is optimal gain which is designed as:

where \({R_{SE}}=R_{{SE}}^{T} \geqslant 0\) is obtained by addressing the following equation:

Proof 1

The stability of the optimal observer is analyzed to guarantee that all estimated system signals remain bounded. By combining Eq. (17) and Eq. (20), the dynamics of the state estimation error can be derived \({e_x}(t)={z_x}(t) - {\hat {z}_x}(t)\), and its time derivative is obtained as:

where \({\delta _x}(t)={H_{xy}}{e_y}(t)+{F_x}{N_x}({z_x},t)\) and \({\bar {A}_x}={A_x} - {L_x}{C_x}\).

Choose \({L_x}\) such that \({\bar {A}_x}\) is Hurwitz, we have:

Since \(\left\| {{e^{{{\bar {A}}_x}t}}} \right\| \leqslant {k_x}{e^{ - \lambda t}}\) for any \({k_x},{\lambda _x}>0\) and \({\delta _x}(t) \leqslant {\rho _x}\), it follows that

Therefore, the optimal observer ensures input-to-state stability, and all estimated signals remain bounded. Moreover, if \({\delta _x}(t) \to 0\) as \(t \to \infty\) then \({e_x}(t) \to 0\) and the estimation error is asymptotically stable.

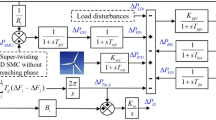

The proposed SMC based estimated state

This subsection presents the development of the proposed SMC scheme based on the estimated states obtained from the OSE. To enhance robustness and ensure system convergence despite uncertainties, a multi-stage sliding surface is constructed. This design allows the controller to shape a multi-stage sliding surface from the estimated states, which improves robustness against disturbances and enhances the system’s convergence characteristics and steady-state behavior.

The sliding surface has been chosen as a multi-stage form given by:

where \({S_x}\) is sliding matrix designed to secure that matrix \({S_x}{B_x}\) is invertible and matrix.

The main objective is to ensure that the sliding surface and its derivative are maintained at zero, guaranteeing that the system dynamics satisfy the desired performance and robustness requirements. Differentiate \({G_x}[{\hat {z}_x}(t)]\) in Eq. (26) following time, we have

Combining with dynamic equation of OSE in Eq. (20) and Assumption 1, we have

Establishing \({\dot {G}_x}[{\hat {z}_x}(t)]={G_x}[{\hat {z}_x}(t)]=0\), then equivalent controller is set as

To account for model uncertainties and external disturbances, a switching control component is also incorporated. Consequently, the overall control law is expressed as:

where.

\(u_{x}^{{sw}}(t)= - {({S_x}{B_x})^{ - 1}}{\chi _x}sign[{G_x}(t)]\) and \(u_{x}^{{eq}}(t)\) is the equivalent control term, designed to maintain the system trajectories on the sliding surface; \(u_{x}^{{sw}}(t)\) is the switching control term, designed to counteract the effects of disturbances and uncertainties.

Theorem 1

Considering the system dynamics given in Eq. (17), the control law constructed from an equivalent control input in Eq. (29) and switching control input \(u_{x}^{{sw}}(t)\), both derived based on the triple-integral sliding surface in Eq. (26), ensures that the closed-loop system is asymptotically stable.

Proof 2

To analyze the stability of the proposed control system, a Lyapunov function candidate is constructed as:

So, taking the derivative of \(V(t)\) in Eq. (31), that we have

By applying Eq. (28), we have

Substituting \(u_{x}^{{ov}}(t)\) in Eq. (30) into \(\dot {V}(t)\) in Eq. (33), we gain

The above inequality implies that the system trajectories of the proposed SMC law in Eq. (30) reach the sliding surface and keep it for later. This method aims to ensure that all relevant signals remain ultimately within a bounded region. By carefully tuning the control parameters, the ultimate bound can be established without requiring any prior information about the extent of system uncertainties.

It is clear that \(\dot {V}(t) \leqslant 0\). This implies that

Suppose there exists a positive constant \({\rho _x}\) such that

Then it follows that

Then we gain

Taking the time derivative of \(V(t)\) again yields

Taking that limit t reaches infinity on both sides of Eq. (39), it can be illustrated that

It is clear that \(\ddot {V}(t)\) is also bounded. Therefore, \(\dot {V}(t)\)is uniformly continuous. It can be seen that \(V(t)\)is bounded, \(\dot {V}(t)\)is negative semi-definite. By applying Barbalats lemma37, we have

According to Eq. (34), we have

It is clearly that \(\mathop {\lim }\limits_{{t \to \infty }} {G_x}[{\hat {z}_x}(t)]=0\). Therefore, by standard linear control argument, \(\mathop {\lim }\limits_{{t \to \infty }} {G_x}[{\hat {z}_x}(t)]=0\)is gain and the asymptotic stability of the MHPSs can be guaranteed.

Figure 3 shows the overall structure of the proposed scheme, where the OSE provides noise-resilient state estimates that are fed into the multi-stage SMC. Based on these estimates, the controller generates control signals for thermal, hydro, and gas units, ensuring robust frequency regulation under diverse operating conditions.

Remark 2

While conventional SMC guarantees stability and disturbance rejection, its direct application to complex MHPSs is hindered by limited scalability and reduced flexibility in shaping the closed-loop dynamics. The proposed multi-stage SMC fundamentally enhances the sliding surface structure by incorporating multiple error terms and auxiliary dynamics, which allow the controller to adapt more effectively to large-scale uncertainties and renewable variability. This design achieves markedly faster convergence, stronger disturbance rejection, and smoother control actions than traditional SMC, as validated by the performance indices and transient responses presented in the results. Therefore, the mathematical development of the multi-stage SMC is not a marginal refinement but a necessary step to deliver robust and practically viable frequency regulation in future complex PSs.

Simulated results

To evaluate the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed multi-stage SMC combined with OSE, comprehensive simulation studies were conducted on both isolated and multi-area HPSs under various operating scenarios. The performance was compared with integral SMC (PI-SMC)27,28, double ISMC (DI-SMC)29, proportional derivative SMC (PD-SMC)30,31, single-phase PI-SMC38 techniques and normal state estimator (NSE)34 in terms of frequency regulation, dynamic response, and robustness against disturbances and uncertainties.

Simulation 1: isolated HPS without renewable and ESS

The first set of simulations was conducted on an isolated HPS comprising different generation units such as thermal (reheat and gas turbines) and hydro power plants, alongside RES, including PV and wind power. To enhance frequency stability and support system inertia, ESS, specifically BESS and FESS, were also integrated into the system configuration. This isolated setup was selected to assess the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed control scheme in a standalone operating environment, where the absence of inter-area support makes frequency regulation more challenging. Two representative test cases were examined to evaluate the controller’s performance under step load disturbances, matched uncertainties, and communication delays. The parameters of MHPSs proposed in3,39 is shown in Appendix.

Figure 4 illustrates the Bode plots of the proposed scheme applied to the HPSs. The magnitude and phase responses corresponding to three input channels are shown (reheat, hydro, and gas turbines). It can be observed that the closed-loop system exhibits stable dynamics with negative slopes in the magnitude plots at high frequencies, ensuring asymptotic stability. The phase margins remain positive across the critical frequency ranges, indicating robustness of the proposed scheme against parameter variations and disturbances. Furthermore, the smooth magnitude bounded phase response confirms that the designed controller effectively suppresses oscillations and maintains reliable frequency regulation in practical HPSs.

Case 1: performance evaluation of OSE under step load disturbance

In the first case, a step load disturbance of 0.01 p.u is introduced at 0 s to evaluate the effectiveness of different state estimators, including the OSE and the NSE29, when applied within both the conventional PI–SMC22,23 and the proposed SMC schemes. Figure 5 illustrates the frequency deviation responses and their corresponding estimated values. It is evident that the OSE provides highly accurate estimation, with the estimated frequency trajectory nearly identical to the actual response, especially when used with the proposed SMC. This leads to a fast settling time, low overshoot, and smooth convergence to steady-state. In contrast, the NSE shows a significantly poorer estimation quality, especially under the PI–SMC configuration, where the estimated frequency deviates considerably from the actual signal, resulting in large oscillations and a longer recovery period. Figure 6 further reinforces this conclusion by comparing ACE signals and their estimates. The proposed SMC with OSE maintains the smallest ACE magnitude and fastest convergence, with the estimated ACE closely following the actual trajectory. These results confirm that the OSE significantly enhances the observability and estimation fidelity of system states, directly contributing to improved transient performance, whereas the NSE lacks robustness and precision under dynamic load disturbances. Overall, the combination of proposed SMC and OSE provides superior control and estimation synergy, which is critical for reliable LFC in HPS.

Case 2: performance evaluation of proposed SMC scheme under matched uncertainties

In the second case, matched uncertainties were introduced to assess the robustness of the proposed SMC scheme. System matrices were intentionally perturbed within known bounds, as illustrated by the uncertainty matrix (\(\Delta {A_x}\)) presented in27. It should be noted that in this study, the uncertainty structure is modeled as a bounded, time-varying perturbation to provide a tractable benchmark for robustness analysis. While real-world uncertainties can be nonlinear and affect multiple system matrices simultaneously, the chosen representation effectively validates the capability of the proposed SMC to preserve stability and performance under significant modeling deviations.

Figure 7a; Table 2 show the frequency error responses under four control strategies: the proposed SMC, PI–SMC27,28, DPI–SMC29, and PD–SMC31,32. The proposed SMC achieves the fastest settling time, lowest overshoot, smallest steady-state error, and the lowest ITAE value, reflecting superior dynamic performance and error suppression. In contrast, remaining methods exhibit larger frequency deviations, longer oscillation durations, and higher ITAE indices, indicating reduced robustness to modeling uncertainties.

Figure 7b presents the ACE signals, which further confirm the superior performance of the proposed SMC. The ACE trajectory under the proposed controller is smooth, rapidly converging to zero. Figure 8 illustrates the control signals applied to different turbine types. The proposed SMC ensures well-damped control efforts across all units, with smooth transitions and no excessive switching. PD–SMC shows slightly more aggressive initial control action, while PI– and DPI–SMC generate larger oscillations, particularly in the gas and reheat turbine responses. These results collectively demonstrate that the proposed SMC not only preserves control performance but also enhances system robustness under parameter uncertainties, outperforming classical and derivative-based SMC schemes.

Remark 3

As observed in Fig. 8, the proposed controller produces only small high-frequency components during the initial transient, while the control signals quickly converge to smooth trajectories. This indicates that chattering is effectively alleviated in practice, and the control actions remain bounded and feasible for all generating units.

Case 3: performance evaluation of proposed SMC scheme under communication delay

In this case, a representative communication delay of 1 s is introduced into the control loop to examine the effectiveness of the proposed method. As shown in Fig. 9, the proposed SMC maintains stable and well-damped frequency and ACE responses with only a slight increase in settling time. In contrast, single-phase PI–SMC presented in38 exhibits pronounced oscillations and slower recovery compared to the proposed scheme. Figure 10 further compares the control signals of the reheat, hydro, and gas turbines. Under the proposed SMC, the control efforts are smoother and better regulated, avoiding abrupt changes or excessive oscillations even under delayed feedback compared to the PI–SMC scheme.

These results demonstrate that the proposed SMC effectively preserves stability, damping, and control smoothness in the presence of significant delays, whereas the newly published single-phase PI–SMC scheme struggles to maintain satisfactory performance. Therefore, the proposed scheme is inherently robust against communication delays, ensuring reliable frequency regulation and coordinated turbine control in practical HPS.

Simulation 2: comprehensive multi-area HPS under random load demand and matched uncertainties

This case investigates the performance of the proposed SMC scheme in a realistic MHPS environment that includes conventional units (thermal, hydro, and gas turbines), BESS and FESS, and RES such as PV and wind turbines. The system is subjected to both random load variations and time-varying renewable generation profiles, as illustrated in Fig. 11. These disturbances reflect highly dynamic and uncertain grid conditions typical of modern renewable-integrated systems. Despite the stochastic nature of inputs, the proposed controller successfully maintains stable operation across all three areas.

Figure 12 shows the frequency responses under the proposed scheme, where all three areas remain within acceptable frequency deviation bounds with rapid correction and minimal overshoot. Notably, the controller mitigates inter-area oscillations and preserves system synchrony despite random disturbances. Figure 13a presents the ACE signals, demonstrating that the proposed SMC ensures fast convergence and minimal control error across all areas. The ESS output responses shown in Fig. 13b confirm the controller’s ability to coordinate ESS dynamically, with smooth and well-damped control signals that counteract power imbalances in real time. Overall, the results validate the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed SMC in a highly variable, MAPS, outperforming traditional control approaches in managing random disturbances and maintaining frequency stability under high renewable penetration.

Remark 4

The computational burden of the proposed multi-stage SMC with OSE has also been considered. Since the control law mainly involves matrix operations of relatively low order for observer gain and sliding surface updates, the overall complexity remains comparable to that of existing SMC methods. This confirms that the proposed approach can be feasibly implemented in real-time applications without imposing significant computational overhead.

Conclusion

This paper proposed a robust and efficient load frequency control (LFC) strategy for modern multi-area hybrid-source power systems (HPSs) with high penetration of renewable energy sources (RES) and the integration of various energy storage systems (ESS), including battery ESS (BESS) and flywheel ESS (FESS). The proposed control approach combines an optimal state estimator (OSE) with a novel multi-stage sliding mode controller (SMC) to enhance system stability, robustness, and dynamic performance under diverse operating conditions. The optimal state estimator was designed to deliver accurate state feedback despite the presence of disturbances and uncertainties, thereby enabling improved controller precision. The proposed multi-stage SMC, developed based on a multi-term sliding surface, ensures rapid dynamic response, strong damping characteristics, and robustness to system uncertainties while mitigating chattering effects. Comprehensive simulations were performed on both isolated and multi-area HPSs. Under various scenarios, including step and random load disturbances, matched uncertainties, and communication delay, the proposed controller consistently achieved superior frequency regulation performance compared to existing SMC methods. It significantly reduced overshoot and undershoot, shortened settling time, and ensured robust operation across different system configurations. In conclusion, the proposed OSE-based multi-stage SMC provides a reliable, scalable, and practical solution for frequency control in future complex PSs with high RES and ESS integration. It demonstrates strong potential for real-world implementation in ensuring stable and resilient grid operation under growing system complexity and uncertainty. Future research will focus on two main directions. First, real-time hardware-in-the-loop validation using platforms such as OPAL-RT will be conducted to further verify the feasibility of the proposed controller under realistic operating conditions. Second, the framework will be extended to incorporate time-varying uncertainties and system nonlinearities in order to more accurately capture real-world system dynamics.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are based on numerical simulations. No raw measurement data were used. Therefore, data sharing is not applicable to this article. Simulation codes and processed results that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding/first author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- \(\Delta F_{x}\) :

-

Frequency fluctuations (Hz)

- \(\Delta P_{PTx}\) :

-

Output power of the reheat thermal unit (p.u. MW)

- \(\Delta P_{GTx}\) :

-

Intermediate output of the thermal generator (p.u. MW)

- \(\Delta X_{ETx}\) :

-

Output of the thermal governor (p.u. MW)

- \(\Delta P_{GHx}\) :

-

Output power of the hydro turbine unit (p.u. MW)

- \(\Delta P_{RHx}\) :

-

Intermediate output power in the hydro turbine unit (p.u. MW)

- \(\Delta X_{EHx}\) :

-

Output of the hydro governor (p.u. MW)

- \(\Delta P_{GGx}\) :

-

Final output power of the gas turbine unit (p.u. MW)

- \(\Delta P_{RGx}\) :

-

Output after rotor dynamics in the gas turbine unit (p.u. MW)

- \(\Delta P_{VGx}\) :

-

Output of the valve position in the gas turbine unit (p.u. MW)

- \(\Delta X_{EGx}\) :

-

Output of the gas turbine governor (p.u. MW)

- \(\Delta P_{PVx}\) :

-

Output power of the PV generation unit (p.u. MW)

- \(\Delta P_{WTGx}\) :

-

Output power of the wind turbine generator (p.u. MW)

- \(\Delta P_{BEx}\) :

-

Output power of the BESS (p.u. MW)

- \(\Delta P_{FEx}\) :

-

Output power of the FESS (p.u. MW)

- \(\Delta P_{Tie,xy}\) :

-

Tie-line power flow deviation between area x and area y (p.u. MW)

- \(\Delta ACE_{x}\) :

-

Area control error, reflecting both frequency deviation and tie-line power imbalance

- \(u_{x1} ,\,u_{x2} ,\,u_{x3}\) :

-

Control signals applied to the thermal, hydro, and gas turbine units, respectively

- \(\alpha_{x1} ,\,\alpha_{x2} ,\,\alpha_{x3}\) :

-

Participation factors of thermal, hydro, and gas units, respectively

- \(\alpha_{xy}\) :

-

Participation factor associated with tie-line power between area x and area y

References

El-Hameed, M. A., Saeed, M., Kabbani, A. & Abd El-Hay, E. Efficient load frequency controller for a power system comprising renewable resources based on deep reinforcement learning. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 18379 (2025).

Ramesh, M., Yadav, A. K. & Pathak, P. K. An extensive review on load frequency control of solar-wind based hybrid renewable energy systems. Energy Sour. Part A Recover. Utilization Environ. Eff. 47(1), 8378–8402 (2025).

Davoudkhani, I. F., Zare, P., Abdelaziz, A. Y., Bajaj, M. & Tuka, M. B. Robust load-frequency control of islanded urban microgrid using 1PD-3DOF-PID controller including mobile EV energy storage. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 13962 (2024).

Tran, A. T., Van Huynh, V., Shim, J. W. & Lim, C. P. Optimized sliding mode frequency controller for power systems integrated energy storage system with droop control. IEEE Access. 13, 43749–43766 (2025).

Wadi, M., Shobole, A., Elmasry, W. & Kucuk, I. Load frequency control in smart grids: A review of recent developments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 189, 114013 (2024).

Yusuf, S. S., Kunya, A. B., Abubakar, A. S. & Salisu, S. Review of load frequency control in modern power systems: a state-of-the-art review and future trends. Electr. Eng. 1–26 (2024).

Dev, A. et al. Advancements and challenges in microgrid technology: A comprehensive review of control strategies, emerging technologies, and future directions. Energy Sci. Eng. 13(4), 2112–2134 (2025).

Qu, Z. et al. Optimized PID controller for load frequency control in multi-source and Dual-Area power systems using PSO and GA algorithms. IEEE Access. (2024).

Alayi, R. et al. Optimal load frequency control of Island microgrids via a PID controller in the presence of wind turbine and PV. Sustainability 13(19), 10728 (2021).

Hussain, J., Zou, R., Pathak, P. K., Karni, A. & Akhtar, S. Design of a novel cascade PI-(1 + FOPID) controller to enhance load frequency control performance in diverse electric power systems. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 243, 111488 (2025).

Gupta, D. K. et al. Fractional order PID controller for load frequency control in a deregulated hybrid power system using Aquila optimization. Results Eng. 23, 102442 (2024).

Ojha, S. K. & Maddela, C. O. Load frequency control of a two-area power system with renewable energy sources using brown bear optimization technique. Electr. Eng. 106(3), 3589–3613 (2024).

Davoudkhani, I. F. et al. Maiden application of mountaineering team-based optimization algorithm optimized 1PD-PI controller for load frequency control in islanded microgrid with renewable energy sources. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 22851 (2024).

Singh, K., Amir, M. & Arya, Y. Optimal dynamic frequency regulation of renewable energy based hybrid power system utilizing a novel TDF-TIDF controller. Energy sources. Part. A: Recovery Utilization Environ. Eff. 44(4), 10733–10754 (2022).

Dev, A. et al. Enhancing load frequency control and automatic voltage regulation in interconnected power systems using the Walrus optimization algorithm. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 27839 (2024).

Dong, S., Yang, G., Bian, Y., Wu, Z. G. & Liu, M. Decentralized periodic dynamic event-triggering fuzzy load frequency control for multi-area nonlinear power systems based on IT2 fuzzy model. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. (2024).

Nayak, P. C., Prusty, R. C. & Panda, S. Adaptive fuzzy approach for load frequency control using hybrid moth flame pattern search optimization with real time validation. Evol. Intel. 17(2), 1111–1126 (2024).

Gulzar, M. M. et al. An efficient design of adaptive model predictive controller for load frequency control in hybrid power system. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2022(1), 7894264 (2022).

Gulzar, M. M., Sibtain, D. & Khalid, M. Cascaded fractional model predictive controller for load frequency control in multiarea hybrid renewable energy system with uncertainties. Int. J. Energy Res. 2023(1), 5999997 (2023).

Kayalvizhi, S. & Kumar, D. V. Load frequency control of an isolated micro grid using fuzzy adaptive model predictive control. IEEE Access. 5, 16241–16251 (2017).

Kumar, V., Sharma, V., Arya, Y., Naresh, R. & Singh, A. Stochastic wind energy integrated multi source power system control via a novel model predictive controller based on Harris Hawks optimization. Energy Sour. Part A Recover. Utilization Environ. Eff. 44(4), 10694–10719 (2022).

Kumar, V., Kumar, V. & Dev, A. Voltage and frequency regulation in wind penetrated deregulated power system using an electric vehicle and IPFC assisted model predictive controller. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 31109 (2025).

Jabari, M. et al. A novel artificial intelligence based multistage controller for load frequency control in power systems. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 29571 (2024).

El Zoghby, H. M. et al. Islanded microgrids frequency support using green hydrogen energy storage with ai-based controllers. IEEE Access. (2024).

Chang, S. & Qi, S. Design and analysis of a load frequency control system based on improved artificial intelligence control algorithm. Alexandria Eng. J. 61(12), 11779–11786 (2022).

Irfan, M., Deilami, S., Huang, S., Tahir, T. & Veettil, B. P. Optimizing load frequency control in microgrid with vehicle-to-grid integration in australia: based on an enhanced control approach. Appl. Energy. 366, 123317 (2024).

Mi, Y., Fu, Y., Wang, C. & Wang, P. Decentralized sliding mode load frequency control for multi-area power systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 28(4), 4301–4309 (2013).

Alhelou, H. H., Nagpal, N., Kassarwani, N. & Siano, P. Decentralized optimized integral sliding mode-based load frequency control for interconnected multi-area power systems. IEEE Access. 11, 32296–32307 (2023).

Tran, A. T., Pham, N. T., Van Huynh, V. & Dang, D. N. M. Stabilizing and enhancing frequency control of power system using decentralized observer-based sliding mode control. J. Control Autom. Electr. Syst. 34(3), 541–553 (2023).

Guo, J. A novel proportional-derivative sliding mode for load frequency control. IEEE Access. (2024).

Huynh, V. V. et al. Robust super-twisting algorithm-based single-phase sliding mode frequency controller in power systems integrating wind turbines and energy storage systems. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 19740 (2025).

Tran, D. T., Tran, A. T., Van Huynh, V. & Do, T. D. Decentralized frequency regulation by using novel PID sliding mode structure in Multi-area power systems with hydropower turbines. IEEE Access. (2025).

Li, X. et al. Improving frequency regulation ability for a wind-thermal power system by multi-objective optimized sliding mode control design. Energy 300, 131535 (2024).

Tran, A. T., Duong, M. P., Pham, N. T. & Shim, J. W. Enhanced sliding mode controller design via meta-heuristic algorithm for robust and stable load frequency control in multi‐area power systems. IET Generation Transmission Distribution. 18(3), 460–478 (2024).

Dev, A., Anand, S., Chauhan, U., Verma, V. K. & Kumar, V. Frequency regulation in microgrid using sliding mode control with event-triggering mechanism. Electr. Eng. 106(3), 3381–3392 (2024).

Dev, A., Mondal, B., Verma, V. K. & Kumar, V. Teaching learning optimization-based sliding mode control for frequency regulation in microgrid. Electr. Eng. 106(6), 7009–7021 (2024).

Slotine, J. J. E. & Li, W. Applied Nonlinear Control, Vol. 199, No. 1, 705 (Prentice Hall, 1991).

Tuan, D. H., Pidanic, J., Van Huynh, V., Duy, V. H. & Nhan, N. H. K. Sliding mode without reaching phase design for automatic load frequency control of multi-time delays power system. IEEE Access. (2024).

Tavakoli, S., Zamani, A. A. & Khajehoddin, A. Efficient load frequency control in multi-source interconnected power systems using an innovative intelligent control framework. Energy Rep. 11, 2805–2817 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) grant funded by the Korea government (MOTIE) (No. RS-2025-02311040). This work was supported by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) grant funded by the Korea government (MOTIE) (No. RS-2024-00421642).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Anh-Tuan Tran: Conceptualization, Writing – orginal, Methodology, Software, Investigation. Van Van Huynh and BangLe-Huy Nguyen: Methodology, Investigation, Software, Jae Woong Shim: Supervisor, Writing – review and editing, funding acquisition; and Ton Duc Do: Supervisor, Writing – review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

-

PS parameters39: \({K_{PSx}}=68.9655\), \({T_{PSx}}=11.49s\), \({\beta _x}=0.4312\), \({K_{Ix}}=1\), \({\alpha _{xy}}=1\), \({T_{xy}}=0.0433\);

-

Reheat-turbine thermal power plant39: \({T_{Tx}}=0.3s\), \({K_{Rx}}=0.3\),\({T_{Rx}}=10.2s\), \({T_{SGx}}=0.06s\), \({R_{x1}}=2.4\), \({\alpha _{x1}}=0.9973\);

-

Hydro-turbine power plant39: \({T_{Wx}}=1.2s\), \({T_{RSx}}=4.9\), \({T_{RHx}}=28.749s\), \({T_{GHx}}=0.2s\), \({R_{x2}}=2.4\), \({\alpha _{x2}}=0.2210\);

-

Gas-turbine power plant39: \({T_{CDx}}=0.2s\), \({T_{CRx}}=0.01s\), \({T_{Fx}}=0.239s\),\({X_{Gx}}=0.6\), \({Y_{Gx}}=1.1\), \({c_{Gx}}=1\), \({b_{Gx}}=0.049\), \({R_{x3}}=2.4\), \({\alpha _{x3}}=0.1982\);

-

PV Generator3: \({T_{ICx}}=0.004s\), \({T_{INx}}=0.04\), \({K_{PVx}}=1\), \({T_{PVx}}=1.8\);

-

Wind turbine3: \({K_{TWGx}}=1\), \({T_{TWGx}}=1.5s\);

-

BESS and FESS3: \({T_{BESS}}=0.1s\), \({T_{FESS}}=0.1s\).

-

OSE parameters: The process and measurement noise covariance matrices in Eq. (18) are chosen as:

\({Q_{SE}}=diag[100,100,...,100] \in {R^{13 \times 13}}\) and \({P_{SE}}=[1]\).

and the resulting observer gain matrix in Eq. (21) is:

\({L_x}=\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {L_{{x1}}^{{13 \times 6}}}&{L_{{x2}}^{{13 \times 7}}} \end{array}} \right]\)

These values were tuned to balance estimation accuracy and robustness against measurement noise.

-

Multi-stage SMC parameter: Sliding matrix in Eq. (26) is selected as:

and control power in Eq. (30) is selected as \({\chi _x}=4.03\).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tran, AT., Van Huynh, V., Nguyen, B.LH. et al. Multi-stage sliding mode control design with optimal state estimator for load frequency regulation in hybrid-source power systems. Sci Rep 15, 43795 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27659-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27659-6