Abstract

Although sepsis-related mortality has declined with advances in care, the incidence of septic shock is rising by 1–8% annually. As life expectancy increases, the ≥ 90-year-old population is projected to reach 10 million in the U.S. by 2050, highlighting septic shock as a growing public health burden. Despite urinary tract infections being a common cause, non-urinary sources may carry higher mortality. However, outcome data in nonagenarians and centenarians are limited. This study compares outcomes by infection source in ICU patients aged 90 years or older with septic shock. This retrospective study, approved by the Alfred Ethics Committee (No. 253/24), used de-identified data from the ANZICS Adult Patient Database (2010–2023), including nonagenarian and centenarian ICU patients with septic shock. Variables included demographics, comorbidities, frailty, severity scores, and 24-h biomarkers. Outcomes were mortality by infection source and length of stay. Propensity score matching ensured covariate balance. Time-dependent Cox models and AUROC analysis were used. Complete case analysis was performed, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Among 1095 ICU patients aged ≥ 90 with septic shock, non-urinary tract infections were associated with significantly higher short-term mortality compared to urinary sources, even after propensity matching (300-day HR 1.348; p = 0.012). ICU mortality (15.7% vs. 8.6%) and hospital mortality (29.0% vs. 17.3%) were also higher in the non-urinary group. APACHE III score, but not age or SOFA score, predicted mortality. Urine output and arterial pH were the best mortality discriminators for non-urinary and urinary sources, respectively. Higher SOFA and APACHE III scores were linked to shorter hospital stays, but not ICU length of stay. In critically ill patients aged ≥ 90 with septic shock, infection source was an independent, time-dependent predictor of mortality. Non-urinary tract infections were associated with significantly higher mortality than urinary tract infections for the first 300 days, despite comparable illness severity. These findings underscore the prognostic importance of infection source and its role in early risk stratification, triage, and end-of-life planning. Simple physiological markers, including urine output and arterial pH, demonstrated additional discriminatory value. As the very elderly ICU population grows, integrating infection source and early physiological indicators into tailored prognostic tools is essential to guide individualized, efficient care in high-resource critical care settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although sepsis-related deaths have decreased as technological improvements have expedited diagnosis and advanced treatment, the incidence of septic shock has markedly increased, by 1–8% every year1. In particular, as health outcomes have improved2,3, the nonagenarian and centenarian population has rapidly grown and is projected to reach 10 million in America alone by 20504. Given the positive correlation between age and septic shock risk attributable to weakened immunity and common comorbidities in the geriatric population5, this demographic change highlights the increasing importance of septic shock as a global health burden.

Sepsis results from a dysregulated host inflammatory response to microbial infection and can progress to septic shock, which is characterized by the presence of sepsis accompanied by hyperlactataemia and persistent hypotension requiring vasopressor support. The in-hospital mortality rate for septic shock has been reported to be 30–50%6. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are a common causal factor for septic shock, yet infections can also occur in sites of non-urinary tract origin, such as the lungs or gastrointestinal system7. Despite nonagenarians’ and centenarians’ high susceptibility, literature on septic shock specific to this demographic is considerably lacking8,9,10. Comparative studies demonstrate that elderly patients with septic shock secondary to urinary tract infections exhibit lower mortality rates than those with pulmonary, abdominal, or other non-urinary sources11. While some studies, including Schertz et al.12, have examined differences in sepsis outcomes according to infection site, detailed data specifically evaluating this association in nonagenarians and centenarians admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with septic shock remain limited. Clinical management informed by such generalized conclusions largely overlooks the importance of age as an independent risk factor13. Awareness of the prognostic value of infection origin for nonagenarians and centenarians admitted to the ICU with sepsis is critical for timely risk stratification, resource planning, and appropriate clinical management.

Therefore, this study aimed to compare mortality, complications, and length of stay between septic shock of urinary and non-urinary tract origin in ICU patients aged 90 years or older. We hypothesized that non-urinary tract infections would be associated with higher mortality despite comparable illness severity. The primary outcome was hospital mortality, with secondary outcomes including ICU mortality and length of stay.

Methods

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Alfred Ethics Committee (project No. 253/24). The requirement for informed consent was waived because this study was retrospective and based on de-identified data. Data analysis commenced only after ethics approval was obtained.

Data sources, study population, and variables

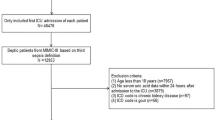

The study was conducted in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines14. De-identified patient-level data were sourced from the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS) Adult Patient Database, which captures information on demographics, clinical characteristics, interventions, and outcomes. This database covers approximately 98% of intensive care units (ICUs) in Australia and 68% of ICUs in New Zealand, and the data are collected by the ANZICS Centre for Outcome and Resource Evaluation15. This study included all nonagenarian and centenarian patients admitted to a participating ICU with a primary diagnosis of septic shock, defined according to the APACHE III–J system, between 2010 and 2023. The collected demographic variables comprised age, sex, admission type and source, discharge destination, and ICU and hospital admission dates. Biochemical markers were documented as peak and nadir values within the first 24 h of the ICU stay. Urine output was extracted from the ANZICS Adult Patient Database, which records total urine volume during the first 24 h of ICU admission. For patients with incomplete urine collection or an ICU stay shorter than 24 h, urine output was automatically extrapolated by the ANZICS data system to represent a 24-h equivalent using standardized internal algorithms. Clinical data encompassed frailty, assessed with the modified Clinical Frailty Scale, and illness severity, evaluated with the APACHE III–J score. Documented comorbidities included immunosuppression; malignancy; and chronic respiratory, cardiovascular, hepatic, and renal diseases.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was the difference in mortality risk between non-urinary tract and urinary tract sources of septic shock among nonagenarian and centenarian ICU patients. The secondary outcome was the difference in ICU and hospital lengths of stay between groups. In addition, physiological parameters and biomarker profiles at ICU admission were examined to characterize baseline differences between urinary tract and non-urinary tract septic shock presentations.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted in R version 4.4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). To minimize confounding and achieve covariate balance between patients with urinary tract versus non-urinary tract sources of septic shock, we performed 1:1 propensity score matching with the MatchIt package. Propensity scores were estimated with logistic regression models incorporating age, sex, APACHE III-J score, admission source and type, and relevant comorbidities. Balance diagnostics were evaluated with standardized mean differences and visualized with Love plots. Continuous variables were summarized as medians with interquartile ranges and compared with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical variables were compared with chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed with Schoenfeld residuals and was found to be violated. Consequently, time-dependent Cox proportional hazards models were used, stratified by follow-up period, to evaluate early (≤ 300 days) and late (> 300 days) mortality separately and met the proportional hazards assumption. ICU and hospital length of stay were treated as skewed continuous outcomes and log₁₀-transformed to approximate normality.

The results were back-transformed for interpretability and are reported as relative changes in geometric mean duration. In addition, the discriminative ability of key clinical scores and admission biomarkers for ICU and hospital mortality was assessed with area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) analysis, with 95% confidence intervals estimated via 2000 bootstrap replicates. All analyses were conducted on complete cases. The proportion of missing data was less than 5% for all variables, and no imputation was performed. All statistical tests were two-sided, and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons in secondary or exploratory outcomes.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 1095 nonagenarians and centenarians with ICU admission for septic shock were included in the study. The baseline characteristics before and after propensity score matching are presented in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively. Love plot of the propensity matching is illustrated in Fig. 1. In the unmatched cohort (Table 1), patients with septic shock of non-urinary tract origin (n = 721), compared with patients with septic shock of urinary tract origin (n = 374), had significantly higher APACHE III scores (median 79 vs. 76; p = 0.001); higher SOFA scores (6 vs. 5; p = 0.010); markedly lower survival days (median 22.96 vs. 71.32; p < 0.001); higher white blood cell counts, bilirubin, and urea levels; and lower urine output and hematocrit levels.

After 1:1 propensity score matching, 740 patients were included (370 in each group). No significant differences in age, illness severity, or frailty at ICU admission were observed between groups. The mean age was 92.3 years in both groups (p = 0.605), and comparable scores were observed for APACHE III (77.49 vs. 78.00, p = 0.706), SOFA (5.57 vs. 5.59, p = 0.899), and Glasgow Coma Scale (14.10 vs. 14.12, p = 0.883) scores between groups.

Several statistically significant differences in laboratory and physiological markers were observed between groups. Patients with septic shock of urinary tract origin had higher maximum white blood cell counts (19.88 [SD 11.93] × 10⁹/L vs. 16.55 [9.31], p < 0.001), lower maximum bilirubin levels (16.25 [13.10] μmol/L vs. 24.91 [27.92], p < 0.001), and greater urine output (1436.18 [894.25] mL vs. 1241.58 [891.73], p = 0.004) than patients with septic shock of non-urinary tract origin. Renal function markers also differed between groups, such that both the maximum and minimum creatinine levels were significantly higher in the urinary tract origin group (maximum: 184.51 [172.78] vs. 162.99 [85.50] μmol/L, p = 0.035; minimum: 160.84 [86.00] vs. 146.90 [77.84], p = 0.025). Hematological differences included lower maximum and minimum hematocrit levels and hemoglobin in the urinary tract origin group (e.g., maximum hematocrit: 0.33 vs. 0.34, p = 0.023; maximum hemoglobin: 10.82 vs. 11.17 g/dL, p = 0.008).

Analysis of sources of admission indicated that a higher proportion of patients in the urinary tract origin group were admitted from nursing homes or chronic/palliative care facilities (11.2% vs. 3.6%), whereas more patients in the non-urinary tract origin group were admitted from other acute hospitals (p = 0.001).

Crucially, patients with septic shock of urinary tract origin had significantly lower ICU mortality (8.6% vs. 15.7%, p = 0.005), hospital mortality (17.3% vs. 29.0%, p < 0.001), and 1-month mortality (20.5% vs. 30.6%, p = 0.002) than patients with septic shock of non-urinary tract origin. Differences in 6-month mortality also reached significance (31.4% vs. 40.1%, p = 0.016), whereas the 1-year and long-term mortality rates were similar between groups.

Mortality analyses

In the unmatched cohort, septic shock of non-urinary tract origin was associated with a 1.56-fold greater risk of death within 300 days than septic shock of urinary tract origin (Table 5; HR 1.563; 95% CI 1.280–1.908; p < 0.001). Beyond 300 days, we observed no statistically significant difference in mortality risk between groups (HR 0.943; 95% CI 0.683–1.302; p = 0.721).

In the matched cohort, up until 300 days, mortality risk remained significantly higher in the non-urinary tract origin group, with a hazard ratio of 1.348 (HR 1.348; 95% CI 1.068–1.700; p = 0.012). However, beyond 300 days, mortality risk between the two groups became statistically insignificant (HR 0.899; 95% CI 0.609–1.327; p = 0.592).

In the matched analysis, the APACHE III score was significantly associated with mortality, such that each one-point increase corresponded to a 2.7% increase in hazard (HR 1.027; 95% CI 1.019–1.034; p < 0.001). No significant associations were observed for age (HR 0.982; 95% CI 0.930–1.035; p = 0.496), sex (HR 0.900; 95% CI 0.734–1.103; p = 0.308), SOFA score (HR 0.992; 95% CI 0.952–1.034; p = 0.695), or elective admission (HR 0.699; 95% CI 0.253–1.930; p = 0.486).

Additionally, Kaplan–Meier analysis revealed a significant difference in survival between the two groups (Fig. 2). Patients with non-UTI septic shock exhibited lower survival probabilities compared with those with urinary septic shock (log-rank p = 0.035).

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was performed excluding patients transferred from other hospitals to assess the robustness of the primary findings (Supplementary Table 2). In the univariate Cox regression, non-UTI septic shock was associated with significantly higher mortality within 300 days compared with UTI septic shock in both the unmatched (HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.06–1.71; p = 0.017) and matched cohorts (HR 1.44, 95% CI 1.17–1.77; p = 0.001). Beyond 300 days, this association was no longer significant. Age, sex, SOFA score, and elective admission status were not significantly associated with survival, whereas higher APACHE III scores remained consistently predictive of mortality across cohorts.

Length of stay

Table 6 illustrates association between different covariates and length of ICU and hospital stay. No variables were significantly associated with ICU length of stay in either the unmatched or matched cohorts. By contrast, hospital length of stay was inversely associated with SOFA and APACHE III scores in both cohorts. In the unmatched cohort, higher SOFA (GMR 0.940, 95% CI 0.921–0.959; p < 0.001) and APACHE III scores (GMR 0.989, 95% CI 0.986–0.992; p < 0.001) were significantly associated with shorter hospital stay. These associations remained significant in the matched cohort (SOFA: GMR 0.954, 95% CI 0.926–0.982; p = 0.002; APACHE III: GMR 0.993, 95% CI 0.989–0.997; p = 0.001). No other covariates demonstrated statistically significant associations with hospital stay.

Discriminatory performance of clinical predictors

Table 7 presents the top five univariate predictors of ICU and hospital mortality, ranked by AUROC, and stratified by infection source. Among patients with septic shock of non-urinary tract origin, urine output demonstrated the highest discriminatory performance for ICU mortality (AUROC 0.834; 95% CI 0.798–0.870), and was followed by the APACHE III score (0.787; 95% CI 0.750–0.825) and lactate (0.756; 95% CI 0.695–0.817). In this group, urine output (AUROC 0.753; 95% CI 0.718–0.788) and APACHE III score (0.752; 95% CI 0.719–0.785) remained the strongest predictors of hospital mortality.

In the septic shock of urinary tract origin cohort, arterial pH was the best predictor of ICU mortality (AUROC 0.844; 95% CI 0.770–0.918), and was followed by the APACHE III score (0.784; 95% CI 0.694–0.875) and SOFA score (0.776; 95% CI 0.693–0.860). In this group, pH (0.728; 95% CI 0.652–0.803) and APACHE III score (0.720; 95% CI 0.640–0.801) again performed best in discriminating hospital mortality risk but had slightly lower discriminatory ability for ICU outcomes.

Discussion

Key findings

In this binational retrospective cohort of critically ill older adults with septic shock, patients exhibited high mortality in both the short and long term, regardless of infection source. Patients with sepsis of non-urinary tract origin had significantly higher short-term mortality than patients with sepsis of urinary tract origin, even after propensity score matching (300-day mortality: HR 1.348; 95% CI 1.068–1.700; p = 0.012). However, beyond approximately 300 days, the mortality difference between urinary and non-urinary sources was no longer statistically significant. Despite similar baseline severity between groups, as measured with the APACHE III and SOFA scores, several physiological and biochemical differences persisted after matching. Urine output, arterial pH, and the APACHE III score consistently emerged as the strongest individual risk discriminators of both ICU and hospital mortality, with AUROCs exceeding 0.75 in both infection source groups. No significant differences in ICU or hospital length of stay were observed between groups. These findings suggested that the infection source meaningfully influences early outcomes and prognostication in septic shock among patients of very advanced age, particularly during the acute phase of critical illness.

Relationship of findings to the literature

Our findings align with and extend existing evidence highlighting infection source as an important determinant of mortality in patients with septic shock, particularly among older critically ill populations. Previous systematic reviews have indicated substantial variability in septic shock mortality according to infection site. A large multicenter observational study in patients with septic shock has reported significantly lower mortality associated with urinary tract infections than respiratory or abdominal infections even after adjustment for illness severity16,17,18. These clinical observations align closely with our findings, thereby supporting that infection source is an independent prognostic indicator.

Mechanistically, evidence from host-response profiling studies has suggested differential inflammatory and coagulation responses depending on the anatomical source of infection. Chen et al. have demonstrated variations in biomarker expression and inflammatory cascade activation by infection site, which might potentially have contributed to the distinct clinical outcomes observed across sources19.

Our study addresses a notable gap by evaluating patients 90 years or older and using propensity score matching to rigorously assess the influence of infection source on mortality. Specifically, we observed a 35% greater hazard of 300-day mortality associated with septic shock of non-urinary tract origin rather than urinary tract origin, despite comparable baseline illness severity scores between groups.

Finally, our identification of urine output and arterial pH as robust individual predictors (AUROC > 0.75) supports ongoing calls to incorporate simple physiological measurements alongside traditional severity scores for prognostication in septic shock and sepsis20,21,22. Together, our findings reinforce the clinical and biological heterogeneity of septic shock, and emphasize infection source as an essential factor for accurate prognostic assessment, particularly in older ICU populations.

Clinical implications

Our findings have direct implications for ICU resource allocation, early risk stratification, and bedside decision-making by intensivists and anesthetists. The substantially higher early mortality risk in septic shock of non-urinary tract origin than of urinary tract origin, despite comparable severity scores between groups, suggests that infection source should potentially be integrated into initial triage algorithms and clinical deterioration pathways. This distinction is particularly relevant in older patients, for whom decisions regarding care escalation, ventilator support, and treatment limitation often rely on nuanced prognostic information. In parallel, the strong predictive performance of urine output, arterial pH, and APACHE III score provides a simple yet powerful tool to identify high-risk patients who might benefit from closer hemodynamic monitoring, early intervention, or prioritization for ICU beds. Given the increasing burden of sepsis in aging populations and the finite availability of critical care resources, incorporating infection source and key physiological markers into clinical workflows might improve both patient outcomes and hospital efficiency. These insights are particularly pertinent for anesthetists involved in perioperative optimization and for critical care teams making rapid decisions regarding admission and intervention thresholds.

Directions for future research

Future studies should explore the mechanisms underlying the differential short- and long-term mortality risks associated with infection source in septic shock, particularly in older adults. Prospective investigations incorporating microbiological profiles, pathogen virulence, host immune responses, and source control adequacy might aid in clarifying why non-urinary tract infections are associated with disproportionately higher early mortality. Additionally, external validation of infection source as an independent prognostic variable in larger and more diverse ICU populations is warranted. Research is also needed to determine whether integrating infection source into existing risk prediction models—alongside dynamic physiological variables such as urine output and arterial pH—might improve the calibration and clinical utility of early mortality prediction tools. Finally, implementation studies should assess whether infection-source-informed triage or treatment algorithms can improve patient-centered outcomes, guide more appropriate use of ICU resources, and support shared decision-making in frail or older populations.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several notable strengths. To our knowledge, it is the first to examine the prognostic effects of infection source in septic shock specifically among nonagenarian and centenarian ICU patients. The large sample size, derived from a comprehensive, binational intensive care database, allowed for robust statistical power and generalizability within this age group. The use of 1:1 propensity score matching helped mitigate confounding by indication and ensured balanced baseline characteristics across comparison groups. In addition, we applied time-split Cox models to account for violations of the proportional hazards assumption, and consequently were able to explore short- and long-term mortality patterns with enhanced temporal resolution. Our findings were further supported by AUROC-based analyses of physiologic discriminators, thus reinforcing the clinical applicability of simple bedside markers such as urine output and arterial pH.

However, several study limitations must be acknowledged. First, the observational design precludes definitive causal inference, and the possibility of residual confounding cannot be excluded despite propensity matching and multivariable adjustment. Second, infection source classification relied on clinician-entered diagnostic codes within the APACHE III and ANZICS data fields, as microbiological data were incomplete across sites. Consequently, some degree of misclassification is possible, and patients with multiple concurrent infections were categorized according to the predominant source recorded at ICU admission. Third, culture results, pathogen profiles, and antimicrobial resistance data were unavailable, preventing assessment of the influence of microbiological factors on disease severity and outcomes. Fourth, this analysis was limited to ICUs in Australia and New Zealand, which are characterized by well-resourced healthcare systems and comparatively low baseline mortality in older adults; therefore, extrapolation to resource-limited settings should be undertaken with caution. Furthermore, the registry does not reliably differentiate community-onset from hospital-onset sepsis, and inter-hospital transfers may have introduced variability in illness severity and pre-ICU management. Finally, although this study represents one of the largest cohorts of patients aged 90 years or older with septic shock, subgroup analyses were underpowered for less frequent infection sites and comorbidity clusters.

Conclusion

In critically ill patients 90 years or older with septic shock, infection source was found to be an independent and time-dependent determinant of mortality. Septic shock of non-urinary tract origin was associated with significantly higher 300-day mortality than septic shock of urinary tract origin, despite comparable illness severity between groups. These findings highlight the prognostic relevance of infection source and underscore the importance of incorporating this variable into early risk stratification, triage decisions, and end-of-life discussions. Simple physiological markers such as urine output and arterial pH offer additional discriminatory value and might assist clinicians in identifying high-risk patients. As the population of very old adults requiring intensive care continues to grow, tailored prognostic tools integrating infection source and early physiological indicators are needed to support more individualized and efficient care delivery in high-resource critical care settings.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Epidemiology of sepsis in Australia. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2020 [cited 2025 Jul 28]. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-05/epidemiology_of_sepsis_-_february_2020_002.pdf

UN. Global Issues: Ageing. United Nations. 2024.

Ismail, Z., Wan Ahmad, W. I., Hamjah, S. H. & Astina, I. K. The impact of population ageing: A review. Iran J. Public Health 50(12), 2451–2460. https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v50i12.7927 (2021).

Kawas, C. H. The oldest old and the 90+ study. Alzheimers Dement. 4(1), S56–S59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2007.11.007 (2008).

Nasa, P., Juneja, D. & Singh, O. Severe sepsis and septic shock in the elderly: An overview. World J. Crit. Care Med. 1(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v1.i1.23 (2012).

Hotchkiss, R. S. et al. Sepsis and septic shock. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2(2), 16045. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.45 (2016).

Kempker, J. A. & Martin, G. S. The changing epidemiology and definitions of sepsis. Clin. Chest Med. 37(2), 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2016.01.002 (2016).

Seymour, C. W. & Rosengart, M. R. Septic shock. JAMA 314(7), 708. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.7885 (2015).

Park, C. et al. Early management of adult sepsis and septic shock: Korean clinical practice guidelines. Acute Crit. Care 39(4), 445–472. https://doi.org/10.4266/acc.2024.00920 (2024).

Du, C. et al. Predicting patients with septic shock and sepsis through analyzing whole-blood expression of NK cell-related hub genes using an advanced machine learning framework. Front. Immunol. 28, 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1493895 (2024).

Artero, A. et al. Influence of sepsis on the middle-term outcomes for urinary tract infections in elderly people. Microorganisms 11(8), 1959. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11081959 (2023).

Schertz, A. R., Eisner, A. E., Smith, S. A., Lenoir, K. M. & Thomas, K. W. Clinical phenotypes of sepsis in a cohort of hospitalized patients according to infection site. Crit. Care Explor. 5(8), e0955. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCE.0000000000000955 (2023).

Juneja, D. Severe sepsis and septic shock in the elderly: An overview. World J. Crit. Care Med. 1(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v1.i1.23 (2012).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology 18(6), 800–804 (2007).

Secombe, P. et al. Thirty years of ANZICS CORE: A clinical quality success story. Crit. Care Resusc. 25(1), 43–46 (2023).

Bauer, M. et al. Mortality in sepsis and septic shock in Europe, North America and Australia between 2009 and 2019- results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 24(1), 239. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-02950-2 (2020).

Pieroni, M., Olier, I., Ortega-Martorell, S., Johnston, B. W. & Welters, I. D. In-hospital mortality of sepsis differs depending on the origin of infection: An investigation of predisposing factors. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 9, 915224. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.915224 (2022).

Abe, T. et al. Variations in infection sites and mortality rates among patients in intensive care units with severe sepsis and septic shock in Japan. J. Intensive Care 7, 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-019-0383-3 (2019).

Chen, L. et al. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 9(6), 7204–7218. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.23208 (2017).

Tandogdu, Z. et al. Urosepsis 30 day mortality, morbidity, and risk factors: SERPENS study. World J. Urol. 42, 314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-024-04979-2 (2024).

Hu, T., Qiao, Z. & Mei, Y. Urine output is associated with in-hospital mortality in intensive care patients with septic shock: A propensity score matching analysis. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 18(8), 737654. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.737654 (2021).

Wernly, B. et al. Acidosis predicts mortality independently from hyperlactatemia in patients with sepsis. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 76, 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2020.02.027 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JMS contributed to study conception, data analysis, interpretation of analysis, manuscript drafting and revisions; NR contributed to interpretation of analysis and manuscript revisions; JL and AY contributed to interpretation of analysis and manuscript drafting and revisions; DP contributed to study conception, interpretation of analysis and manuscript revisions; DKL provided oversight of statistical analysis and contributed to manuscript revisions; LW contributed to study conception, interpretation of analysis, manuscript drafting, revisions and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Alfred Hospital Ethics Committee approved this study (Project No. 253/24), waiving the requirement for informed consent because the study is retrospective and uses de-identified data. Data analysis only commenced once ethics approval had been obtained. The study was conducted in compliance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suh, J.M., Weinberg, L., Raykateeraroj, N. et al. Outcomes of septic shock from urinary and non-urinary sources in nonagenarians and centenarians admitted to intensive care units. Sci Rep 15, 43902 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27714-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27714-2