Abstract

Time-to-event (TTE) machine learning (ML) algorithms are increasingly utilized in prognostic models, but systematic evaluation is lacking to identify their strengths and limitations. We compared TTE ML algorithms — Oblique Random Survival Forest (ORSF) and Random Survival Forest (RSF) to statistical models (SMs) — Cox Proportional Hazards (Cox PH) and Penalized Cox PH, examining their predictive performance and computational time. Eighteen scenarios were generated with varying censoring rates, sample sizes, and predictor effects, assuming the PH assumption. Performance was evaluated using Harrell’s C-index and IBS, with differences assessed using One-Way Repeated Measures ANOVA. In the linear with additive effects scenario, SMs outperformed RSF in terms of C-indices and IBS scores, with negligible differences between ORSF variants and SMs. ORSF variants were slightly higher in C-indices and comparable in IBS scores to RSF. Under the non-linear scenario with interaction effects, SMs’ models consistently achieved higher C-indices than RSF, with minimal differences from ORSF. SMs were similar to RSF and ORSF in IBS scores, except at a high censoring rate of 90%. ORSF yielded significantly higher C-indices and lower IBS scores than RSF at censoring rates of 50–70%. Overall, differences between ORSF variants in discrimination and calibration were not significant; however, ORSF-net had the longest training time among all ML models. Conclusively, RSF showed inferior discrimination to SMs and ORSF. Traditional SMs outperform ML models in TTE prediction at higher censoring rates but match ORSF at lower rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Time-to-event analysis, also known as survival analysis, is a set of statistical methods used to model the time to the occurrence of an event of interest1,2. They are extensively used in the health field when the objective is to estimate the incidence of an event or to predict the risk of developing the event within a clinically meaningful period of time. Examples of applications include predicting the risk of death, cardiovascular disease (CVD) event, or cancer relapse3,4,5,6. One important characteristic of time-to-event data is right-censoring1. This occurs when the time to event is partially observed due to study discontinuation or loss to follow-up. More specifically, in right-censored subjects, only the minimum time-to-event is observed. A widely used statistical model (SM) to analyze right-censored data in clinical research is the semi-parametric Cox proportional hazards (Cox PH) model7, valued for its semiparametric flexibility and interpretability.

In recent years, machine learning (ML) algorithms have been increasingly applied to develop diagnostics and prognostics prediction models and have been recognized as a transformative innovation in healthcare3,8,9. However, many of the ML algorithms applied in most of these healthcare applications do not take into account the fact that observations might be right-censored10,11,12. According to a comprehensive survey conducted by Wang et al., a number of ML algorithms have now been adapted and developed in order to address the issue of censorship in survival analysis13. Random survival forest (RSF), an extension of Breiman’s random forest (RF)14, is one of the most frequently employed ML techniques that accommodate right censored time-to-event data15. Recently, the Oblique Random Survival Forest (ORSF), an extension of Ishwaran’s RSF, which is an ensemble of supervised learning methods for right-censored data, was introduced16,17. ORSF showed inferior prediction accuracy; nevertheless, evaluating several linear combinations of predictors incurred significant computational time16.

It is critical to assess and compare novel and existing methods in different scenarios to reveal their strengths and weaknesses. This systematic evaluation is frequently implemented using simulation studies18. A peculiar advantage of a simulation lies in its ability to allow the estimation of the “true” performance of the method being used, since the true data-generating mechanism distribution is known18. Smith et al.19, in their scoping review, highlighted the advantages of simulation studies in comparing ML to traditional SM in time-to-event data in terms of risk prediction. Moreover, the authors of the aforementioned review concluded that limited studies have compared statistical and ML methods using simulation studies. Furthermore, although several simulation studies have compared RSF with either the Cox PH or its penalized extension11,20,21,22,23, no independent simulation study has compared the performance of the novel ORSF with RSF, Cox PH, or Penalized Cox PH24. Therefore, the significance of this research lies primarily in its systematic, independent, and comprehensive evaluation of advanced ML models against traditional SM for time-to-event data, specifically addressing a notable gap in the existing literature and assessing the impact of various characteristics on predictive measures.

The aim of this study is to assess and compare, through extensive simulations, the predictive ability of several ML algorithms and SMs, including ORSF, standard RSF, Cox PH, and Penalized Cox PH models. Models are compared under various scenarios, including sample size, censoring rate, and the presence of interaction or non-linear effects. We also aim to investigate how sensitive the predictive accuracy of ORSF is to different specifications of the linear combination criteria. Additionally, we compare computational time between ORSF configurations and standard RSF.

This paper is structured into sections as follows: In Methods, the data-generating process, the selected algorithms, and additional methodological details are outlined. Following this, the Results detailed the outcomes of the simulation. Next, in the Discussion, findings are interpreted and discussed, the study’s strengths and limitations, directions for future work, and implications are presented. Finally, the paper concludes with a summary.

Methods

In this section, we describe a comprehensive simulation study comparing the predictive performance of SMs (Cox PH and Penalized Cox PH) and two ML algorithms (RSF and ORSF) in predicting the risk of developing the event of interest (CVD) when fitted to time-to-event data under varying conditions. We outline the primary procedures involved in executing our simulation, encompassing the algorithms for comparison, simulation parameters, performance indicators, and implementation specifics.

Description of the models

The cox proportional hazards model

The Cox PH model is among the most widely used models in survival analysis within medical research25. It provides a semi-parametric specification of the hazard function, allowing for the estimation of covariate effects without requiring specification of the baseline hazard. In this model, the hazard of developing an event at time t is defined as follows:

where \({h}_{0}(t)\) is a non-parametric baseline hazard, and \(exp({\beta }^{T} x)\) is the relative risk function. For each risk factor in the vector \(x\), the association with the incidence of the event is characterized by the hazard ratio exp(β). The Cox model is typically fitted in two steps. First, the parametric component is estimated by maximizing the partial likelihood, which is independent of the baseline hazard. Subsequently, the non-parametric baseline hazard is estimated based on the fitted covariate effects.

Two variations of Cox PH models are used in this paper: (i) the traditional model including all covariates (Cox PH), (ii) the Penalized Cox PH model that incorporates variable selection through regularization techniques26,27. Penalization shrinks the estimates of regression coefficients towards zero relative to maximum likelihood estimates. This shrinkage helps to prevent overfitting caused by collinearity of covariates or high dimensionality of the data. L1 (lasso) penalty applies an absolute value constraint to the coefficients, while L2 (ridge) penalty applies a quadratic constraint to the coefficients28,29. Here, we used a combination of both L1 and L2 penalties to obtain fewer coefficients set to zero than a pure L1 setting, and more shrinkage of other coefficients.

The random survival forest

The Random Survival Forest (RSF) implementation follows concepts similar to RF. The process involves drawing B bootstrap samples from the data. For each sample, a survival tree is constructed. During tree construction, at each node, a random subset of predictor variables is selected (mtry). Among these candidates, the best node split is chosen based on a splitting criterion that uses the log-rank test and hence accounts for right-censoring. This process is applied recursively to daughter nodes until a stopping criterion, such as the minimum number of unique cases in a terminal node, is satisfied. Finally, the cumulative hazard function (CHF) is calculated for each tree, and these are averaged over all trees to define the ensemble CHF15.

The oblique random survival forest

The Oblique Random Survival Forest (ORSF) is an ensemble method for right-censored survival data first proposed by Janger et al. in 201917. The main difference between Jaeger’s ORSF and standard RSF lies in the splitting strategy: ORSF uses linear combinations of multiple predictors to recursively partition the training data, while the standard RSF relies on univariate splits using a single predictor at each node.

The ORSF fits Cox PH or similar models into the non-terminal nodes of its survival trees. These models generate Linear Combinations of Input Variables (LCIVs) using their estimated coefficients, and these LCIVs are then employed as the variable for splitting non-leave nodes. Evaluating candidate solutions for the coefficients involves computing LCIVs for each observation in the current node and selecting random candidate cut-points from the unique LCIV values. For each chosen cut-point, a log-rank statistic is computed to compare the survival curves between observations in the potential child nodes resulting from the split. A node terminates early if the maximum log-rank statistic does not exceed a predetermined threshold; otherwise, the cut-point and the candidate solution that optimize the log-rank statistic are used to partition the node.

Three criteria (fast, cph, and net) are used in the current ORSF implementation to construct LCIVs. In the fast criterion, a single iteration of Newton–Raphson scoring on the Cox partial likelihood function is used to fit the LCIVs, the default method in ORSF. In the cph criterion, the coefficients acquired from fitting a Cox PH regression are used to determine the linear combinations of predictors. The last version (net) uses Penalized Cox PH regression at each node to construct LCIVs24.

Simulation settings

In this section, we describe in detail the settings for the simulations that we carried out. These include the data-generating process, the number of simulations, the different scenarios, and the performance metrics used.

The data-generating mechanism

Data were generated to mimic a real-world popular cohort study in CVD, namely the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA)30, as it is essential for the simulated data to conform to real-world data31. MESA is a large prospective cohort study based in the United States. The study was initiated in July 2000 to investigate the burden, associated factors, and progression of subclinical CVDs in a large sample of adults aged 45 to 84 years30. The study provides extensive longitudinal data, including clinical, imaging, biomarker, and lifestyle information, which has been extensively used for developing and validating CVD risk models32. Due to the multi-ethnic composition of the MESA cohort and highly standardized data collection protocols employed, MESA data is ideal for developing CVD prediction models that could be generalized to different populations30.

Continuous potential predictors were simulated from a truncated normal distribution, and binary predictors from a Bernoulli distribution. To ensure a reasonable correlation structure among the features (predictors), the means, and probabilities used in the simulation procedure were obtained from models fitted to the MESA data. Table 1 presents a detailed overview of the distribution parameters utilized for continuous (\({X}_{1}, {X}_{4}- {X}_{7}\)) and binary (\({X}_{2}, {X}_{3} and {X}_{8}\)) predictors. \({X}_{6}\), \({X}_{7}\) and \({X}_{8}\) are presented as non-informative variables in this simulation.

Survival times were generated from a parametric Cox PH model where the hazard function follows a Weibull distribution.

where \({\text{U}}\) follows a uniform distribution \({\text{U}}\sim Uniform\left(0,1\right)\), \(\lambda and \nu\) represent the scale and shape of the Weibull distribution. Non-informative right-censoring times were simulated from the Weibull distribution, where both \(\lambda and \nu\) were tuned manually to achieve approximately the desired censoring rate (e.g., 50%, 70% and 90%). These censoring rates were selected to evaluate the performance of the algorithms under low, medium, and high censoring scenarios, such as in CVD research. The parameters of the Weibull distribution for survival and censoring time are presented in Table S1.

We have examined two scenarios to define the underlying true relationships between the informative predictors (\({X}_{1},{X}_{2},{X}_{3},{X}_{4},{X}_{5}\)) and the hazard function. Table S1 outlines the specific mathematical forms of the linear predictors (βˊX) used in each scenario. In Scenario I, which favors SMs, predictors contribute in a linear and additive manner to the hazard function. This indicates that each predictor (\({X}_{1}\) through \({X}_{5}\)) has a constant, independent effect on the log-hazard. In contrast, Scenario II, which favors ML, introduces non-linear and interaction effects, reflecting greater complexity of associations between covariates and the hazard function. Key features of this scenario include non-linear transformations of predictors, such as (\({X}_{4}\)^2), as well as interaction terms wherein the effect of one predictor is conditional on the value of another (\(\text{e}.\text{g}., {X}_{2}* {X}_{3}\)).

We generated various sample sizes of N = 500, 1000, and 5000. The small-sized dataset (N = 500) was chosen since SMs usually outperform MLs in small sample sizes, due to their smaller number of hyperparameters, provided the data meets the model’s assumptions. Conversely, higher sample sizes were selected to determine whether ML performance enhances with an increase in dataset size.

Eighteen scenarios were investigated assuming different associations between the predictors and the hazard function (linear and additive/non-linear and interactions), sample sizes (500/1000/5000), and censoring rates (50%/70%/90%). Nine scenarios showed linear and additive effects, while nine showed non-linear and interaction effects between predictors and outcomes.

The number of replications in this simulation study was set to 40. This was based on the formula proposed by Burton et al.33, where the C-index and standard error were set to 0.66 and 0.02, respectively22. The number of replications specified takes into account the potential model failures during training and/or validation.

The performance metrics

The risks estimated in the validation dataset, along with the actual status, were used to estimate the predictive ability of each method using measures of discrimination and calibration. “Discrimination” refers to how well the predictive model can discriminate between individuals who developed an event and those who did not, whereas “calibration” refers to the agreement between observed and predicted risks34. Discrimination was assessed via Harrell’s concordance index (C-index)35, while model calibration was assessed using integrated Brier score (IBS)36.

Implementation details

During data preprocessing, only continuous variables were scaled. Fig S1 depicts an illustration of three-fold nested cross-validation with three-fold outer resampling for unbiased generalization performance estimates, and hold-out for inner resampling for parameter tuning. Each dataset was randomly split using a static seed into a threefold cross-validation stratified by the outcome event to maintain the original distribution of incidents, specifically in the case of high censoring (e.g., 90%). Then, optimal values of hyperparameters that maximized the performance on the training set were found through a randomized search and hold-out (70%-30%) and 30 repetitions.

For the Penalized Cox PH model, the hyperparameters tuned included L1 and L2 regularization terms. For RSF and ORSF models, the tuned hyperparameters included: the number of trees, the number of features considered for splitting in RSF or for constructing the linear combination in ORSF, and the minimum number of samples required to be at a leaf node. The splitting criteria used were a gradient-based score (global non-quantile) for RSF and C-index for ORSF. In addition, three LCIV-constructed methods (fast, cph, and net) were evaluated as part of the model comparison. Table S2 shows the search space of hyperparameters optimized using randomized search.

Our simulation experiments were conducted between August 2024 and January 2025 on the UAE University High Performance Computing Cluster (HPC) using a computing node with a maximum wall-time of 480 h (20 days). It has two physical CPU chips, which are Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6248 CPU @ 2.50 GHz with 20 cores per CPU and 384 GB RAM, running Red Hat Enterprise Linux. The study was implemented using R version 4.2.137, utilizing the mlr3 ecosystem38, along with mlr3proba39, and mlr3extralearners packages40. The R code used in this study includes the statistical and ML methods, training and validation programs, as well as the generated tabulated results and figures. This is publicly available in the first author’s GitHub repository (https://github.com/AbubakerSuliman/simulation_study_compare_predictive_performance/tree/main)41.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis of Harrell’s C-index, IBS, and training time estimates was conducted in each scenario utilizing boxplot visualization. Distribution of training time represented in median (IQR). In inferential statistics, we presented the mean (95% confidence interval) of Harrell’s C-index and IBS estimates. Additionally, we employed the one-way repeated measures ANOVA test to compare Harrell’s C-index and IBS estimates across the examined methods in each scenario. Following this, post-hoc analyses with a Benjamini & Hochberg adjustment were carried out for all the pairwise differences between the investigated methods. All statistical tests were two-sided; p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. This analysis utilized R version 4.3.1, tidyverse R package version 2.0.042, and rstatix R package version 0.7.243.

Results

Scenario I: comparison under proportional hazards with linear and additive effects

Harrell’s C-index comparison

Figure 1 provides box plots of the median C-index for the Cox PH, Penalized Cox PH, RSF, ORSF-fast, ORSF-cph, and ORSF-net models trained on 40 datasets simulated under the initial scenario. All the models exhibit satisfactory discrimination performance on the simulated dataset. However, the C-indices for the RSF model throughout the nine scenarios were lower than those of the statistical and ORSF models. This trend is more evident across all sample sizes when a 50% censoring rate is used.

The box plots of the C-index values for the three linear combinations of ORSF are almost symmetrical, indicating that the prediction ability of the three ORSF linear combinations is equivalent to the simulated time-to-event data.

The means (and 95% CIs) of the Harrell’s C-indices for Cox PH, Penalized Cox PH, RSF, ORSF-fast, ORSF-cph, and ORSF-net, averaged from 40 simulations over nine scenarios, are provided in Table 2. The impact of a growing censoring rate on statistical models is more pronounced in small (N = 500) than medium (N = 1000) and large (N = 5000) sample sizes. The average Harrell’s C-indices for Cox PH and Penalized Cox PH diminished from 0.675 to 0.657 and from 0.676 to 0.644, respectively, when censoring escalated from 50 to 90%. On the other hand, differences in censoring rates across medium and large sample sizes did not lead to substantial changes in the C-indices of the two statistical models.

Among ML algorithms, an increase in censoring had a minimal impact on predicted performance when the sample size remained constant. As the sample size expanded from 500 to 5000 participants, the mean Harrell’s C-index improved by about 2% across all machine learning models.

The C-indices for SMs were significantly higher than those for RSF models (mean difference [MD] = 0.01 to 0.02, p < 0.001) across all scenarios, except when the sample size was 500 and the censoring rate was 90%. SMs had statistically significantly higher C-indices than the two ORSF variants — ORSF-fast and ORSF-cph (MD = 0.01, p < 0.05) — except when the sample size was 5,000 and the censoring rates were 50% and 70%; and when the sample size was 500 at a censoring rate of 90%, where the differences were either negligible or not statistically significant. Similarly, ORSF-net was outperformed by Cox PH models across all scenarios of sample size and censoring rate, except when the sample size was 500, and the censoring rate was 90%, where the difference in C-index was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Table S3).

Across all scenarios of sample size and censoring rate, RSF models had statistically significantly lower C-indices than the ORSF variants (MD = -– 0.01 to – 0.02, p < 0.001), except when the sample size was 500 and the censoring rate was 90% where the differences were not statistically significant. The differences in C-indices between the various ORSF variants were generally negligible or not statistically significant (Table S3).

Integrated brier score comparison

The means (and 95% CIs) of the integrated Brier scores for the various models — Cox PH, Penalized Cox PH, RSF, ORSF-fast, ORSF-cph, and ORSF-net — averaged from 40 simulations over nine scenarios, are provided in Table 3 All the models exhibit satisfactory calibration performance on the simulated dataset, with IBS ranging from 0.085 to 0.185.

Across the different scenarios of sample sizes and censoring rates, the Cox PH and Penalized Cox PH had the best calibration, as indicated by the lowest IBS. On the other hand, the RSF recorded the worst calibration, as indicated by the highest IBS, except when the sample size was 500 and the censoring rate was 90%, in which case, the worst performing was the ORSF-net. This performance gap was increasingly evident with larger sample sizes and higher censoring rates. For instance, at a sample size of 5000 and a censoring rate of 90%, the IBS for Cox PH and RSF were 0.141 and 0.176, respectively.

Moreover, across all models, calibration generally deteriorated with increasing censoring rates, regardless of sample size, with RSF and ORSF appearing to be the most sensitive to censoring.

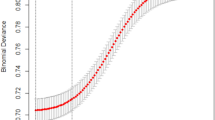

Additionally, the box plots of the IBS values for the three linear combinations of ORSF are almost symmetrical (Fig. 2), indicating that the prediction ability of the three oblique random survival linear combinations is equivalent in the simulated time-to-event data.

RSF models had significantly higher integrated Brier scores (IBS) than SMs across nearly all scenarios (MD = –0.01 to –0.04, p < 0.05), except when the sample size was 500 and the censoring rates were 70% or 90%, where the difference between Cox PH and RSF was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Additionally, larger differences were observed when the sample size was between 1,000 and 5,000 and the censoring rate was 90%. The ORSF variants yielded statistically higher IBS than the SMs in most cases, particularly when the sample sizes (1,000–5,000) were large and the censoring rate was high (90%). However, these differences were generally negligible when the censoring rate was 50%, regardless of sample size (Table S4).

RSF and ORSF were comparable in terms of IBS score in most of the scenarios, with differences being either negligible or not statistically significant. The only exceptions are when the sample size was 5,000 at 70% and 90% censoring rates, where the IBS scores for the RSF were significantly slightly higher than for ORSF-variants (MD = 0.01, p < 0.001). The pairwise differences in IBS among the ORSF variants were generally statistically not significant and/or negligible (Table S4).

Training time

The training time across RSF, ORSF-fast, and ORSF-cph was consistently minimal across all scenarios, with ORSF-fast and ORSF-cph generally taking shorter times to train than the RSF. On the other hand, ORSF-net was the most computationally extensive, requiring significantly longer duration to train across all scenarios of censoring and sample size (Fig S2, Table S5).

Scenario II: comparison of prediction models in proportional hazards with non-linearity and interaction

In the nine simulated situations involving non-linearity with interaction effects, all five models demonstrated a notable improvement in predictive ability compared to the linear additive relationship.

Harrell’s C-index comparison

All examined models attained a C-index of about 90% when the censoring rate and the sample size were set at 90% and 5000, respectively (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the variability in C-indices was greater for small and medium sample sizes.

Table 4 reports the mean (95% CI) of Harrell’s C-indices when modeling non-linearity with interaction for five competitive learning techniques, averaged across 40 simulations over nine scenarios. The C-indices for SMs and ML models improved with increased censoring across all sample sizes, except in ORSF algorithms. Despite the minor variations in SMs as the sample size grows at the same censoring rate, the ML models exhibited comparable patterns at 50% and 70% but not 90% censoring rates. The ORSF-fast exhibits a 1% rise in the C-index as the sample size increased from 500 to 5000 at 50% and 70% censoring rates; however, it shows a 5% increase at a 90% censoring rate with the same sample size expansion.

SMs consistently achieved higher C-indices than RSF models across all scenarios (MD = 0.01 to 0.03, p < 0.001), especially at smaller sample sizes (N = 500) and lower censoring rates (50%). The only exception was when the sample size was 1,000 and the censoring rate was 90%, in which case the C-indices for the Penalized Cox PH and Penalized Cox PH (NLI) models and the RSF model were not significantly different. However, with a sample size of 5,000 and censoring rates of 50% and 70%, the differences in C-index were minimal or non-significant. The differences in C-indices between SMs and ORSF models were mostly minimal, except at a sample size of 500 and a censoring rate of 90%, where the C-indices for SMs were significantly higher (MD = 0.03 to 0.04, p < 0.001) (Table S6).

At sample sizes of 500–1,000 and censoring rates of 50–70%, ORSF models yielded significantly higher C-indices than the RSF models (MD = –0.03 to –0.01, p < 0.001). Conversely, the RSF models showed significantly higher c-indices than the ORSF models at a sample size of 500 and a censoring rate of 90% (MD = 0.02, p < 0.01). The differences in C-indices among the ORSF variants were largely minimal or statistically not significant, except at sample sizes of 500–1,000 and a censoring rate of 90%, where ORSF-cph significantly outperformed ORSF-fast (MD = 0.01, p < 0.01) (Table S6).

Integrated brier score comparison

Under scenario II — involving interaction and non-linearity, all models demonstrated higher integrated Brier scores when the sample size was limited to 500 observations, indicating a decline in calibration. Furthermore, increasing the censoring rate from 70 to 90%, keeping medium-to-large sample sizes (1000 to 5000), led to a slightly higher increase in the IBS in the ML models compared to the SMs (Fig. 4, Table 5).

The models showed varying calibration performances across various conditions. Penalized Cox PH (NLI) had the best calibration at a censoring rate of 50% across all sample sizes, and at a censoring rate of 70% when the sample sizes were 500 or 1000. At a high censoring rate (90%), Cox PH had the best calibration when the sample sizes were 500 or 1000. RSF and ORSF-fast appeared to be the most frequently worst performing in terms of calibration under scenarios involving interaction and non-linearity.

While the SMs were mostly similar to the RSF model in terms of IBS, they showed significantly lower IBS at a high censoring rate of 90% (MD = –0.02 to –0.01, p < 0.05). Although the IBS scores for the SMs were generally similar to those of ORSF models, significantly lower IBS scores (up to a difference of -0.05, p < 0.05) were observed for SMs compared to the ORSF models at a high censoring rate (90%) (Table S7).

RSF models showed significantly higher IBS scores than the ORSF models (MD = 0.01, p < 0.05) in most of the scenarios with censoring rates of 50–70%. A notable switch was observed at a 90% censoring rate with sample sizes of 500 and 1,000, where the IBS scores were significantly lower for the RSF models than the ORSF models (MD = –0.01 to –0.02, p < 0.05). For most cases, there were no significant differences in IBS score between the ORSF variants. However, at a 90% censoring rate, ORSF-fast had statistically significantly higher IBS scores than ORSF-cph (at N = 1,000) and ORSF-net (at N = 1,000 and 5,000) (Table S7).

Training time

RSF, ORSF-fast, and ORSF-cph recorded significantly shorter training times than ORSF-net, as ORSF-net demonstrated a markedly extended duration, up to 53 min, with a larger sample size (N = 5,000). Moreover, while RSF, ORSF-fast, and ORSF-cph exhibited comparable training times at a smaller sample size (N = 500) and across all censoring scenarios, RSF models recorded significantly longer training times than ORSF-fast and ORSF-cph at larger sample sizes (N = 1,000 – 5,000) across all censoring rates (Fig S3, Table S8).

Discussion

In this study, we designed and implemented an innovative simulation framework to model the time-to-event of individuals with CVDs. This framework was subsequently used to evaluate the predominant predictive algorithms for time-to-event data affected by right-censoring. The comparison included classical SMs, including Cox PH and Penalized Cox PH, as well as ML models, including RSF, and the novel ML algorithm — ORSF. We conducted a comparison across many scenarios: varying sample sizes, varying censoring rates, diverse non-linear distributions of continuous variables, and risk heterogeneity (interaction) between two variables.

In all scenarios, when linear effects and additive relations are assumed, RSF achieved the lowest performance among all models considered. Omurlu et al.20 demonstrated that Cox PH performed slightly better than RSF, investigating only scenarios with sample size less than or equal to 500, while Baralou et al.11 reported that Cox PH outperformed all three splitting criteria of RSF under the linear assumption. Moreover, Billichová et al.22 reported that when the data follow the exponential distribution, the Cox PH model outperforms RSF in terms of predictive accuracy. Our findings are consistent with these studies, confirming that RSF is inferior to Cox PH. Moreover, the average relative performance differences between the two models increase when the sample size increases at a 90% censoring rate. On the other hand, all three ORSF linear combinations slightly outperformed RSF and performed similarly to Cox PH when censoring rates were 50% and 70%, with a sample size of 5,000. As expected, the Cox PH and its penalized variant performed slightly better than the ML algorithms in this scenario, given that the model assumptions are satisfied. Additionally, the Cox models require little to no hyperparameter tuning—unlike the ML models, which involve numerous tuning parameters and are therefore more data-intensive22.

When the simulated data exhibited heterogeneity with non-linearity of the risk relationship, performance varied notably depending on the sample size. In small sample sizes, the Cox PH model surpasses both the RSF and the ORSF; nevertheless, in medium and large sample sizes, the Cox PH model exhibits similar accuracy to that achieved by RSF and ORSF. These informative findings are similar to the findings of Billichová et al.22. It is worth mentioning that the effect of increasing the sample size is more apparent in the ML algorithms than the Cox PH models, especially in high censoring rate (90%) where the average difference between 500 and 5000 samples sizes ranges from 2.8% in RSF to 4.6% in ORSF-cph. Significant publications in ML examined the non-linearity of risks (e.g., quadratic); however, they used a linear Cox PH model, which predictably resulted in decreased accuracy, while ML models maintained their accuracy19,22. In this study, we found that if we use Penalized Cox PH, which accounts for interaction and non-linearity, the performance is better than that of RSF and ORSF in a small sample size and is comparable to both RSF and ORSF in a large sample size.

We investigated the predictive performance and computational efficiency of ORSF and its variants, as well as RSF, a neutral comparison (i.e., conducted by authors not affiliated with the authors who proposed the algorithms), which, to the best of our knowledge, has never been carried out. There was no difference in C-index and IBS across all investigated sample sizes and event rates in both scenarios of ORSF-fast and ORSF-cph against ORSF-net. This is similar to the findings of the ORSF authors’ study16. While the performance of ORSF is close to that of RSF in the case of linear and additive scenarios, ORSF algorithms significantly outperformed RSF in the case of interaction and non-linearity. These findings were similar to the original simulation study of ORSF17.

The main strength of our paper is in tuning the parameters of RSF and ORSF. Several existing studies in literature utilized the default, or even arbitrary values, for the ML and deep learning methods11,22. In this study, we used random search with 30 repetitions in the inner cross-validation to find the optimal hyperparameters, which maximized the C-index. The existing data-generating simulations show a lack of plausibility in the sense that they often use independent simulations of feature values, which is unrealistic in the case of biological data33. In this study, we generated correlated features based on the relation magnitude estimated from the MESA study. Furthermore, we calculated the required number of simulations in this study to achieve a certain accuracy, which was rarely conducted in previous simulation studies19.

A limitation of our study is in our data-generating mechanism, which assumes no missing values or outliers. In real medical data, atypical findings are often seen. Consequently, it is essential for future research to simulate 5% outliers and independent variables with missing values and examine the models’ performance in the presence of such anomalies. In our simulated data, we did assume the PH assumption. Although this assumption is often satisfied in real-life applications44, it may boost the performance of traditional methods and diminish the performance of ML models. It is, therefore, important in a future study to simulate data where the PH assumption is violated. Finally, the adaptation of neural networks to time-to-event data was introduced to ML at an early stage. We did not investigate in the current study the performance of a neural network with time-to-event data, such as a Cox PH deep neural network (DeepSurv)45, to allow for a reasonable computation time. However, we plan for such a comparison in our future studies.

Our findings have important implications for healthcare professionals, researchers, and policymakers, enabling them to make more informed decisions when selecting models in time-to-event CVD prediction, particularly in situations with different sample sizes, censoring rates, and effects of predictors on the outcome. The study confirms that a single model cannot fit all scenarios, meaning no one model consistently guarantees the best discrimination and calibration across all situations. For instance, the sample size and censoring rate have a substantial role in the model’s performance. Overall, SMs are credible alternatives to ML algorithms, with ORSF-fast and ORSF-cph emerging as prominent candidates in prognostic research. Finally, the ORSF-net model should be avoided as it offers no performance advantages and is less computationally efficient due to extended training durations.

Conclusion

This simulation study directly addresses the need for systematic evaluation, demonstrating the relative strengths and weaknesses of popular ML and SM approaches for time-to-event data. We showed that RSF had lower discrimination performance compared to Cox PH, Penalized Cox PH, and ORSF. In scenarios with low to moderate censoring rates, ORSF performed similarly to SMs, particularly regarding non-linearity and interactions. Therefore, ORSF would be advantageous for individual risk prediction in the event that the number of instances and variables increases significantly, hence the growing relationship complexity between several covariates. Finally, we observed no significant difference among the various ORSF variations for discrimination or calibration.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study and the code necessary to reproduce the reported results are publicly available in the first author’s GitHub repository (https://github.com/AbubakerSuliman/simulation_study_compare_predictive_performance/tree/main).

References

Collett, D. Modelling Survival Data in Medical Research (Taylor & Francis, 2023).

Kleinbaum, D. G. & Klein, M. Survival Analysis: A Self-Learning Text 3rd edn. (Springer, 2016).

Teshale, A. B., Htun, H. L., Vered, M., Owen, A. J. & Freak-Poli, R. A Systematic Review of Artificial Intelligence Models for Time-to-Event Outcome Applied in Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction. J. Med. Syst. 48, 68 (2024).

Huang, Y., Li, J., Li, M. & Aparasu, R. R. Application of machine learning in predicting survival outcomes involving real-world data: a scoping review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 23, 268 (2023).

Hippisley-Cox, J. & Coupland, C. Development and validation of risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of common cancers in men and women: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 5, e007825 (2015).

Hippisley-Cox, J., Coupland, C. & Brindle, P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ 357, j2099 (2017).

Cox, D. R. Regression Models and Life-Tables. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 34, 187–202 (1972).

Sidey-Gibbons, J. A. M. & Sidey-Gibbons, C. J. Machine learning in medicine: a practical introduction. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 19, 64 (2019).

Alowais, S. A. et al. Revolutionizing healthcare: the role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC Med. Educ. 23, 689 (2023).

Goldstein, B. A., Navar, A. M., Pencina, M. J. & Ioannidis, J. P. A. Opportunities and challenges in developing risk prediction models with electronic health records data: a systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 24, 198–208 (2017).

Baralou, V., Kalpourtzi, N. & Touloumi, G. Individual risk prediction: Comparing random forests with Cox proportional-hazards model by a simulation study. Biom. J. 65, 2100380 (2023).

Sulaiman, R. et al. Machine learning for predicting outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve implantation: A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inf. 197, 105840 (2025).

Wang, P., Li, Y. & Reddy, C. K. Machine Learning for Survival Analysis: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 51, 1–36 (2019).

Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Ishwaran, H., Kogalur, U. B., Blackstone, E. H. & Lauer, M. S. Random survival forests. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2, (2008).

Jaeger, B. C. et al. Accelerated and Interpretable Oblique Random Survival Forests. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 33, 192–207 (2024).

Jaeger, B. C. et al. Oblique random survival forests. Ann. Appl. Stat. 13, (2019).

Morris, T. P., White, I. R. & Crowther, M. J. Using simulation studies to evaluate statistical methods. Stat. Med. 38, 2074–2102 (2019).

Smith, H., Sweeting, M., Morris, T. & Crowther, M. J. A scoping methodological review of simulation studies comparing statistical and machine learning approaches to risk prediction for time-to-event data. Diagn. Progn. Res. 6, 10 (2022).

Kurt Omurlu, I., Ture, M. & Tokatli, F. The comparisons of random survival forests and Cox regression analysis with simulation and an application related to breast cancer. Expert Syst. Appl. 36, 8582–8588 (2009).

Wright, M. N., Dankowski, T. & Ziegler, A. Unbiased split variable selection for random survival forests using maximally selected rank statistics. Stat. Med. 36, 1272–1284 (2017).

Billichová, M. et al. Comparing the performance of statistical, machine learning, and deep learning algorithms to predict time-to-event: A simulation study for conversion to mild cognitive impairment. PLoS ONE 19, e0297190 (2024).

Gong, X., Hu, M. & Zhao, L. Big Data Toolsets to Pharmacometrics: Application of Machine Learning for Time-to-Event Analysis. Clin. Transl. Sci. 11, 305–311 (2018).

Simon, N., Friedman, J., Hastie, T. & Tibshirani, R. Regularization Paths for Cox’s Proportional Hazards Model via Coordinate Descent. J. Stat. Softw. 39, (2011).

Cox, D. R. Regression Models and Life-Tables. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 34, 187–202 (1972).

Goeman, J. J. L1 Penalized Estimation in the Cox Proportional Hazards Model. Biom. J. 52, 70–84 (2010).

Jelle Goeman, Rosa Meijer, Nimisha Chaturvedi, Matthew Lueder. penalized: L1 (Lasso and Fused Lasso) and L2 (Ridge) Penalized Estimation in GLMs and in the Cox Model. The R Foundation https://doi.org/10.32614/cran.package.penalized (2007).

Tibshirani, R. The Lasso Method for Variable Selection in the Cox Model. Stat. Med. 16, 385–395 (1997).

Hoerl, A. E. & Kennard, R. W. Ridge Regression: Biased Estimation for Nonorthogonal Problems. Technometrics 12, 55–67 (1970).

Bild, D. E. et al. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am. J. Epidemiol. 156, 871–881 (2002).

Austin, P. C., Harrell, F. E. & Steyerberg, E. W. Predictive performance of machine and statistical learning methods: Impact of data-generating processes on external validity in the “large N, small p” setting. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 30, 1465–1483 (2021).

McClelland, R. L. et al. 10-Year Coronary Heart Disease Risk Prediction Using Coronary Artery Calcium and Traditional Risk Factors. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 66, 1643–1653 (2015).

Burton, A., Altman, D. G., Royston, P. & Holder, R. L. The design of simulation studies in medical statistics. Stat. Med. 25, 4279–4292 (2006).

Efthimiou, O. et al. Developing clinical prediction models: a step-by-step guide. BMJ 386, e078276 (2024).

Harrell, F. E., Califf, R. M., Pryor, D. B., Lee, K. L. & Rosati, R. A. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. JAMA 247, 2543–2546 (1982).

Graf, E., Schmoor, C., Sauerbrei, W. & Schumacher, M. Assessment and comparison of prognostic classification schemes for survival data. Stat. Med. 18, 2529–2545 (1999).

R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2022).

Lang, M. et al. mlr3: A modern object-oriented machine learning framework in R. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1903 (2019).

Sonabend, R., Király, F. J., Bender, A., Bischl, B. & Lang, M. mlr3proba: an R package for machine learning in survival analysis. Bioinformatics 37, 2789–2791 (2021).

Sonabend R, Schratz P, & Fischer S. mlr3extralearners: Extra Learners For mlr3.

AbubakerSuliman/simulation_study_compare_predictive_performance. GitHub https://github.com/AbubakerSuliman/simulation_study_compare_predictive_performance.

Wickham, H. et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1686 (2019).

Kassambara, A. rstatix: Pipe-Friendly Framework for Basic Statistical Tests. The R Foundation https://doi.org/10.32614/cran.package.rstatix (2019).

Deng, Y. et al. Comparison of State-of-the-Art Neural Network Survival Models with the Pooled Cohort Equations for Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 23, 22 (2023).

Katzman, J. L. et al. DeepSurv: personalized treatment recommender system using a Cox proportional hazards deep neural network. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 18, 24 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: AS, MS, MAS, AO Data Analysis and interpretation: AS, ASA, AA Drafting of the manuscript: all authors Critical revisions of the manuscripts for important intellectual content: all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suliman, A., Abdullahi, A.S., Masud, M.M. et al. Comparison of oblique random survival forest, random survival forest, and statistical models for time-to-event data using simulation study. Sci Rep 15, 44005 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27747-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27747-7