Abstract

Irisin and adiponectin have been proposed as potential therapeutic targets due to their roles in enhancing energy expenditure and improving insulin sensitivity. However, their predictive value for metabolic syndrome (MetS) in middle-aged and older adults remains unclear. This prospective cohort study investigated cross-sectional and 3-year longitudinal associations between serum irisin and adiponectin levels and MetS in an aging population. A total of 348 participants from the Hallym Aging Study were analyzed cross-sectionally, and 188 individuals without MetS at baseline were followed longitudinally. Cross-sectionally, each 1-standard deviation (SD) increase in log-transformed irisin was associated with higher odds of MetS (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.02–1.80), while adiponectin showed an inverse association (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.54–0.94). Longitudinally, participants in the highest irisin tertile had increased risk of incident MetS (OR 3.85, 95% CI 1.20–13.64), and each 1-SD increase in irisin was associated with higher MetS incidence (OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.17–4.03). However, each 1-SD increase in adiponectin was not significantly associated with MetS after adjusting for confounders. While further studies should confirm our findings, the results presented here suggest that irisin may be a useful predictor of MetS in older adults, while adiponectin’s protective role is less clear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the global population ages, the burden of metabolic disorders continues to rise1. Metabolic syndrome (MetS)—a clinical cluster defined by abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia (low HDL-C and elevated triglycerides), hypertension, and impaired fasting glucose—is strongly associated with increased risks of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality2,3. Aging contributes to metabolic deterioration through progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass, accumulation of visceral adipose tissue, and chronic low-grade inflammation4. In Korea, the prevalence of MetS among adults aged 65 years and older increased from 53% in 2013 to 62% in 20225, warranting the need to identify reliable biomarkers that can predict MetS in older adults.

Irisin, an exerkine predominantly secreted by skeletal muscle during exercise, was first identified in 2012 and has since been investigated for its potential therapeutic effects on obesity and type 2 diabetes6. This novel myokine is cleaved from fibronectin type III domain-containing protein 5 (FNDC5), which is upregulated by PGC1-α in skeletal muscle. Irisin facilitates the browning of white adipose tissue, promoting thermogenesis, energy expenditure, and glucose homeostasis. Despite these metabolic effects, previous studies investigating the association between circulating irisin levels and MetS in humans remain controversial6,7,8,9,10. Some studies have reported that higher irisin levels were associated with increased risk of MetS and showed positive relationships with insulin resistance and MetS components7,8. In contrast, other studies have shown that individuals without MetS exhibited higher irisin levels, and increased irisin levels were associated with a lower risk of MetS, suggesting a potential protective role9,10. However, evidence from prospective studies assessing whether irisin predicts the onset of MetS remains limited.

Adiponectin, an adipokine primarily secreted from adipose tissue, contributes to metabolic health by improving insulin sensitivity, anti-inflammatory effects, lipid metabolism regulation, and fatty acid oxidation11. Previous prospective studies have consistently shown that low adiponectin levels were associated with an increased risk of MetS and its components12,13,14,15,16. However, in older adults, elevated adiponectin levels have paradoxically been associated with adverse outcomes, including increased disability, sarcopenia, and mortality, known as the “adiponectin paradox”17,18. This paradox may be attributed to age-related physiological changes, including compensatory adiponectin upregulation in response to vascular inflammation, elevated natriuretic peptides, cardiac stress, or catabolic conditions associated with frailty and weight loss17,18,19,20. Nevertheless, the longitudinal association between adiponectin and the development of MetS in older adults has not been well established.

Therefore, this study aims to investigate the cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between serum irisin and adiponectin levels and the presence and development of MetS over 3 years in a community-based cohort of middle-aged and older Korean adults. We hypothesized that higher irisin levels might be associated with an increased risk of MetS, whereas higher adiponectin levels might be associated with a decreased risk.

Methods

Study population

The Hallym Aging Study (HAS) is a prospective cohort initiated in 2003 to investigate quality of life among community-dwelling adults aged 45 and older in Chuncheon, South Korea. The study design and sampling procedures have been documented in prior studies21,22. In brief, according to the 2000 census data, the city was divided into 1,408 sections, and a random sample of 200 areas was selected. A total of 1,520 participants were recruited using systematic sampling, comprising 30% aged 45–64 years and 70% aged 65 years or older. The baseline survey conducted in 2004 involved 918 participants, followed by follow-up surveys conducted in 2007 (second wave, n = 702) and 2010 (third wave, n = 382).

Cross-sectional analyses were based on the second wave, and longitudinal analyses included data from both the second and third waves. Among the 382 participants who completed both waves, 19 with missing irisin data at both waves were excluded, yielding a final sample of 363 participants. For the cross-sectional analysis, participants with missing data for irisin (n = 4), adiponectin (n = 3), MetS components (n = 4), and hs-CRP (n = 4) were excluded from the 363 eligible individuals, resulting in a final analytic sample of 348 participants. For the longitudinal analysis, after excluding participants with baseline MetS (n = 163), missing data on MetS components at either baseline or follow-up (n = 8), missing adiponectin data (n = 2), and missing high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) data (n = 2), the final sample size was 188 participants. The participant flowchart is presented in Fig. 1.

All study procedures were conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later revisions and were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hallym University (IRB number: 2024-09-001). Prior to enrollment, written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection and anthropometric measurements

Baseline and follow-up assessments included standardized medical history, a lifestyle questionnaire, and a comprehensive health examination. Data were collected by trained interviewers, including age, sex, current drinking (non-drinker/current drinker), current smoking (non-smoker/current smoker), regular exercise (yes/no), and comorbidity status. Comorbidities were categorized as none, one, or two or more, based on the presence of chronic conditions including hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease (stroke, myocardial infarction), osteoporosis, arthritis, depression, and malignancy. Anthropometric measurements were performed with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes. Height and weight were measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg, respectively. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m²). Waist circumference (WC) was taken midway between the lower rib and iliac crest at the end of a normal expiration. Blood pressure was measured according to a standardized protocol. After the participants had rested in a seated position for at least 15 min in a quiet environment, systolic (Korotkoff phase I) and diastolic (Korotkoff phase V) blood pressures were measured in both upper arms using a mercury sphygmomanometer. The arm with the higher blood pressure reading was selected for subsequent measurements. Two additional measurements were then taken from the selected arm at intervals of at least 5 min. The mean of these two readings was used as the final blood pressure. If the difference between the first and second measurements was ≥ 20 mmHg for systolic blood pressure or ≥ 10 mmHg for diastolic blood pressure, a third measurement was performed, and the average of the second and third readings was used as the final value.

Biochemical measurements

Blood samples were collected after an overnight fast of at least 10 h. Fasting glucose, triglycerides, and HDL-C were measured using an auto-analyzer (Hitachi 747, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) was calculated using the Friedewald equation: LDL-C = total cholesterol - (HDL-C + triglycerides/5). Plasma insulin was measured with a gamma counter (Cobra II, Packard Bioscience, Meriden, CT), and insulin resistance was calculated by the homeostasis model assessment (HOMA-IR) formula: [fasting insulin (µU/mL) × fasting glucose (mg/dL)]/405. hs-CRP was analyzed using a particle-enhanced nephelometric immunoassay (Hitachi 7600 analyzer, Hitachi Ltd, Japan). Plasma adiponectin was measured using immunoassay (VersaMax, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Plasma irisin level was assessed using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (NBP3-08117; Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO, USA).

Definition of metabolic syndrome

MetS was identified based on the modified criteria of the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-ATP III)23. Individuals were classified as having MetS if they met at least three of the following criteria: (1) abdominal obesity, defined as a WC of ≥ 90 cm for men and ≥ 85 cm for women based on the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity Guidelines24; (2) elevated blood pressure, defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 85 mmHg or a self-reported physician diagnosis of hypertension; (3) elevated fasting glucose, defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or a self-reported physician diagnosis of diabetes mellitus; (4) elevated triglycerides, defined as serum triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL; (5) reduced HDL-C, defined as HDL-C < 40 mg/dL for men and < 50 mg/dL for women.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data and as median (25th–75th percentile) for skewed data. Differences between participants with and without MetS were assessed using the independent t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. Differences across irisin and adiponectin tertiles were evaluated using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for normally distributed variables, Kruskal-Wallis tests for non-normally distributed variables, and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine the association between circulating irisin, adiponectin levels, and the presence of MetS. Irisin and adiponectin serum levels were analyzed both as continuous and categorical variables based on sex-specific tertiles. For continuous analysis, odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for each 1-SD increase in log-transformed levels. For categorical analysis, tertile groups of each biomarker were used, based on the sex-specific distribution. The analysis included three models: Model 1 was unadjusted; Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, alcohol drinking, current smoking, regular exercise, LDL-C, BMI, and comorbidity; and Model 3 included further adjustment for HOMA-IR and hs-CRP. In the longitudinal analysis, individuals without baseline MetS were included, and the tertile classification of log-transformed irisin and adiponectin levels followed the same sex-specific tertiles as in the cross-sectional analysis. The logistic regression analysis in the longitudinal study included the same covariates as in the cross-sectional analysis. Additionally, Model 2 included the number of baseline metabolic components, while Model 3 further adjusted for follow-up BMI. Additional analyses were performed among participants aged ≥ 65 years using the same modeling strategy and covariate adjustments as in the main analyses (Tables S2 and S3). All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed p-value < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study participants according to MetS

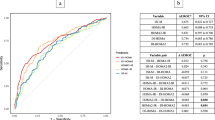

Baseline characteristics of the study participants in the cross-sectional analysis are presented in Table 1. Of the 348 individuals (54.6% women; median age 70 years; range, 52–87 years), MetS was present in 45.4% (n = 158). Participants with MetS had significantly higher BMI, waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, fasting glucose, triglycerides, HOMA-IR, and hs-CRP levels compared to those without MetS (all p < 0.05). In addition, irisin levels were significantly higher in individuals with MetS (p = 0.021), while adiponectin levels were significantly lower in the MetS group (p = 0.001). The geometric means of circulating irisin and adiponectin levels according to the number of MetS components are shown in Fig. 2. Circulating irisin levels increased significantly with a higher number of MetS components, whereas adiponectin levels decreased significantly as the number of components increased (all p for trend < 0.001).

Cross-sectional associations of serum Irisin and adiponectin with MetS

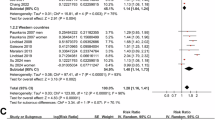

Among the 348 participants, 158 (45.4%) were classified as having MetS. Table 2 presents the cross-sectional associations of serum irisin and adiponectin with the presence of MetS. Each 1-SD increase in log-transformed irisin was significantly associated with higher odds of MetS in Model 1 (OR 1.34; 95% CI 1.08–1.69; p = 0.009) and Model 3 (OR 1.35; 95% CI 1.02–1.80; p = 0.04), while showing marginal significance in Model 2 (OR 1.32; 95% CI 1.00–1.74; p = 0.05). In the categorical analysis using sex-specific tertiles of irisin, the highest tertile was significantly associated with MetS in Model 1 (OR 1.87; 95% CI 1.11–3.17; p = 0.019), but the associations were not statistically significant in Model 2 (OR 1.60; 95% CI 0.88–2.95; p = 0.127) and Model 3 (OR 1.66; 95% CI 0.90–3.09; p = 0.107). In contrast, participants in the highest adiponectin tertile had significantly lower odds of MetS compared to those in the lowest tertile after full adjustment (OR 0.50; 95% CI 0.26–0.96; p = 0.037). Each 1-SD increase in log-transformed adiponectin was significantly associated with lower odds of MetS in fully adjusted model (OR 0.71; 95% CI 0.54–0.94; p = 0.017). Table S2 presents the cross-sectional results among adults aged ≥ 65 years (n = 278), showing similar associations to those observed in the total sample. The overall direction of associations was consistent with those observed in the total sample, although statistical significance was attenuated after full adjustment (irisin: OR 1.90; 95% CI 0.95–3.81; p = 0.069; adiponectin: OR 0.54; 95% CI 0.26–1.09; p = 0.087).

Baseline characteristics according to tertiles of baseline serum Irisin and adiponectin among participants without MetS

Table 3 shows baseline characteristics according to tertiles of baseline serum irisin and adiponectin among participants without MetS at baseline (n = 188). Participants in the highest irisin tertile had a higher proportion of current alcohol drinkers, higher triglycerides, and lower adiponectin levels (all p ≤ 0.01), compared to those in the lowest tertile. In contrast, participants in the highest adiponectin tertile had significantly lower BMI, WC, triglycerides, hs-CRP, and irisin levels (all p ≤ 0.001), compared to those in the lowest tertile. In addition, baseline and follow-up characteristics of participants without MetS at baseline according to the development of MetS over 3-year follow-up are shown in Table S1.

Longitudinal associations of baseline serum Irisin and adiponectin levels with incident MetS

After the 3-year follow-up, 40 of the 188 participants without MetS at baseline (21.3%) developed MetS. Table 4 shows results from the 3-year longitudinal analysis of serum irisin and adiponectin in relation to incident MetS. Each 1-SD increase in log-transformed irisin was significantly associated with higher odds of incident MetS in Model 3 (OR 2.10; 95% CI 1.17–4.03; p = 0.018). In the categorical analysis using sex-specific tertiles of irisin, participants in the highest tertile had significantly increased odds of incident MetS compared to the lowest tertile (OR 3.85; 95% CI 1.20–13.64; p = 0.028). In contrast, participants in the highest adiponectin tertile had significantly lower odds of incident MetS compared to the lowest tertile after full adjustment (OR 0.22; 95% CI 0.06–0.73; p = 0.018). When adiponectin was modeled as a continuous variable (per 1-SD increase in log-transformed levels), adiponectin was significantly associated with lower odds of incident MetS in Model 1 (OR 0.65; 95% CI 0.46–0.93; p = 0.018), but the association was attenuated and no longer statistically significant in Model 3 (OR 0.61; 95% CI 0.36–1.01; p = 0.057). Table S3 presents the longitudinal associations among participants aged 65 years and older (n = 145). Similar trends were observed in older adults, with a more pronounced association between irisin and MetS. Each 1-SD increase in log-transformed irisin remained significantly associated with higher odds of incident MetS after full adjustment (OR 3.49; 95% CI 1.57–8.98; p = 0.005), whereas adiponectin showed an inverse but attenuated association in the fully adjusted model (OR 0.61; 95% CI 0.34–1.09; p = 0.100).

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study of middle-aged and older adults, higher circulating irisin and lower adiponectin levels were consistently associated with both the presence and development of MetS. Cross-sectionally, individuals with MetS had significantly higher serum irisin and lower adiponectin concentrations than those without MetS. Moreover, there was a dose-response relationship between the number of MetS components and both biomarkers, with progressive increases in irisin and decreases in adiponectin. Longitudinally, higher baseline irisin levels were associated with an increased risk of incident MetS over three years, whereas higher adiponectin levels were associated with a lower risk of MetS development. The inverse association for adiponectin remained significant in the categorical data analysis, but it was attenuated when modeled as a continuous variable, particularly after adjustment for metabolic parameters and follow-up BMI.

Experimental research has demonstrated that the expression of irisin in mice fed a high-fat diet led to increased energy expenditure, reduced fat mass, and improved insulin sensitivity by inducing the browning of white adipose tissue6. Additionally, a recent review summarized that irisin may exert protective effects against vascular aging by attenuating endothelial inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction through AMPK-mediated pathways25. However, studies on the relationship between irisin and MetS in humans have yielded inconsistent results. For instance, a study of 1,115 obese Chinese adults reported significantly lower serum irisin levels among individuals with MetS and found an inverse association between log-transformed irisin levels and MetS risk9. In contrast, Park et al. demonstrated higher irisin levels in individuals with MetS and found that increased irisin was significantly associated with higher odds of MetS and each of its components8.

In our cross-sectional analysis, higher irisin levels were significantly associated with increased odds of MetS in the unadjusted model; however, this association was attenuated and became non-significant after adjusting for lifestyle factors, comorbidity, and BMI. This finding aligns with a study of 618 Korean adolescents, in which the association between higher irisin tertiles and MetS risk disappeared after BMI adjustment, and body fat mass was identified as the primary determinant of circulating irisin levels7. Additionally, most human studies have reported a positive association between serum irisin and BMI, WC, or body fat mass, suggesting that increased irisin levels may reflect increased adiposity and a compensatory response to underlying metabolic disturbances, rather than indicating favorable metabolic status8,26,27,28.

Evidence regarding the association between irisin and insulin resistance or lipid profiles is similarly conflicting. A meta-analysis of 14 studies in non-obese, non-diabetic adults reported positive associations between irisin and fasting glucose and HOMA-IR, but no significant associations with other metabolic factors (TC, HDL-C, TG, or LDL-C)29. In addition, subgroup analyses revealed that the association between irisin and insulin resistance was significant only in individuals with metabolic disorders, while no significant association was found in metabolically healthy individuals. This finding suggested that increased irisin levels in individuals with metabolic disorders may reflect a compensatory response to “irisin resistance,” similar to insulin resistance. In line with this, our study found that among participants without MetS at baseline, although those with higher irisin levels had higher triglyceride levels, no differences were observed in blood pressure, fasting glucose, HDL-C, or LDL-C. These findings suggest that the association between irisin and metabolic parameters may be attenuated in metabolically healthy individuals.

Importantly, our longitudinal analysis consistently demonstrated that higher baseline serum irisin levels were independently associated with an increased risk of incident MetS over three years. This association remained significant even after adjustment for lifestyle factors, number of metabolic components, metabolic variables, comorbidity, and both baseline and follow-up BMI. These findings suggest that irisin may function not only as a marker of current metabolic status but also as a predictive biomarker for future metabolic disorders. This observation supports the concept of irisin resistance, whereby elevated serum irisin levels reflect an inadequate compensatory response to maintain glucose and metabolic homeostasis8. In addition, analyses conducted in adults aged ≥ 65 years (Table S3) revealed a stronger association between irisin and incident MetS, suggesting that the compensatory response of irisin may be even more pronounced in older adults. However, little is known about whether age modifies these relationships. Further research is needed to clarify the causal mechanisms underlying baseline levels and longitudinal changes in irisin in relation to the development of metabolic disorders, and to determine whether these associations differ by age.

In contrast to irisin, adiponectin showed inverse associations with MetS in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Participants in the highest tertile of baseline adiponectin had significantly lower odds of MetS prevalence and incidence even after full adjustment, consistent with previous studies30,31. However, the association was attenuated when adiponectin was modeled as a continuous variable after additional adjustment for metabolic parameters (HOMA-IR and hs-CRP) and follow-up BMI. Among adults aged ≥ 65 years (Table S3), the direction of the association remained consistent, although statistical significance was not reached in the fully adjusted model. This attenuation should be interpreted with caution, as the older subgroup included a relatively small number of participants (n = 145) and incident cases (n = 32), which may have limited statistical power. Nonetheless, the consistently lower effect estimates observed across models suggest that adiponectin maintains clinical relevance as a protective biomarker, even when extensive adjustments may partly account for its metabolic pathways.

While consistent in direction with prior evidence, the statistical significance of the association was less pronounced in our cohort. A meta-analysis by Liu et al., which included data from more than 6,000 individuals, demonstrated a significant dose-response relationship in which lower adiponectin levels were linearly associated with a higher risk of incident MetS31. This analysis incorporated five major prospective cohort studies conducted in Japan15,16, Korea13, Finland12, and Denmark14 —all of which consistently reported a significant inverse association between adiponectin levels and MetS risk, even after full adjustment for confounding variables. However, four of the five studies included in the meta-analysis did not involve older adults, and the one Korean study that included individuals aged 40–70 years had a mean age in the mid-50s. In contrast, the median age in our study was 70 years, suggesting that the metabolic role of adiponectin may differ in older populations.

The attenuation of the protective association in older adults may reflect the phenomenon known as the “adiponectin paradox,” in which elevated adiponectin levels are paradoxically associated with adverse outcomes such as cardiovascular disease and mortality in older populations17,18. In general, low adiponectin levels are associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and increased cardiometabolic risk11, and early observational studies reported inverse associations with cardiovascular disease. For instance, Pischon et al. found that low adiponectin independently predicted myocardial infarction in healthy men32, and Kumada et al. demonstrated that hypoadiponectinemia (≤ 4.0 µg/mL) was associated with the presence of coronary artery disease after adjustment for metabolic diseases, smoking habit, and BMI33. Nevertheless, subsequent prospective studies have shown that higher adiponectin concentrations were associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, including heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and myocardial infarction, as well as mortality34,35,36. Elevated adiponectin levels have also been observed in individuals with frailty, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure37,38.

Taken together, these findings suggest that while our results do not clearly demonstrate an adiponectin paradox, the metabolic implications of adiponectin appear to vary across age and disease contexts. Elevated adiponectin in older adults may represent a compensatory “rescue hormone” response to chronic inflammation or catabolic stress rather than a simple indicator of metabolic protection18,19,20. Further longitudinal research is needed to clarify these context-dependent relationships and their clinical relevance in aging populations.

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to investigate the associations of both irisin and adiponectin with incident MetS in community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults. However, several limitations should be noted. First, the observational nature of this study limits causal inference, despite its prospective design and adjustment for confounders. Second, the longitudinal analysis included a relatively small number of cases, with 188 participants without MetS at baseline and only 40 (21.3%) developing MetS over three years. This may have limited the statistical power to detect significant associations, particularly in fully adjusted models. Third, potential biases should be considered. Because only participants who completed both the second and third survey waves were included, attrition bias due to loss to follow-up cannot be excluded. The analytic sample mainly comprised older adults and may not fully represent the broader population. However, subgroup analyses of participants aged ≥ 65 years showed results consistent with those in the overall sample (Tables S2 and S3), supporting internal consistency. Fourth, the exclusion of participants with missing data could have introduced selection bias. Nonetheless, comparisons between included and excluded participants showed no significant differences in key demographic or metabolic variables, except for smoking status and regular exercise (Table S4). This indicates that the baseline characteristics of included participants were generally comparable to those of the overall cohort. Finally, the study population consisted of middle-aged and older Korean adults, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other age groups or ethnic populations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that elevated baseline serum irisin levels independently predict the development of MetS over 3 years in middle-aged and older adults. In contrast, higher adiponectin levels showed a protective effect. The predictive value of irisin for MetS risk suggests its potential as a novel biomarker for identifying individuals at increased metabolic risk before the clinical onset of MetS. Although adiponectin may act as a protective marker, its association with MetS was less pronounced after controlling for metabolic variables and follow-up BMI, and should be interpreted with caution given the observational design and limited sample size. Further studies with larger and more diverse populations are warranted to validate these findings and determine whether the associations of irisin and adiponectin with metabolic risk differ according to age or disease status.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Collaborators, G. A. Global, regional, and national burden of diseases and injuries for adults 70 years and older: systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2019 Study. bmj 376 (2022).

Isomaa, B. et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 24, 683–689 (2001).

Lakka, H. M. et al. The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. Jama 288, 2709–2716 (2002).

Palmer, A. K. & Jensen, M. D. Metabolic changes in aging humans: current evidence and therapeutic strategies. The J. Clin. Investig. 132 (2022).

Rhee, E. J. Prevalence and current status of cardiometabolic risk factors in Korean adults based on fact sheets 2024. Endocrinol. Metab. 40, 174–184 (2025).

Boström, P. et al. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature 481, 463–468 (2012).

Jang, H. B. et al. Association of Circulating Irisin levels with metabolic and metabolite profiles of Korean adolescents. Metabolism 73, 100–108 (2017).

Hee Park, K. et al. Circulating Irisin in relation to insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 98, 4899–4907 (2013).

Shim, Y. S., Kang, M. J., Yang, S. & Hwang, I. T. Irisin is a biomarker for metabolic syndrome in prepubertal children. Endocr. J. 65, 23–31 (2018).

Yan, B. et al. Association of serum Irisin with metabolic syndrome in obese Chinese adults. PloS One. 9, e94235 (2014).

Whitehead, J., Richards, A., Hickman, I., Macdonald, G. & Prins, J. Adiponectin–a key adipokine in the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Obes. Metabolism. 8, 264–280 (2006).

Juonala, M. et al. A longitudinal analysis on associations of adiponectin levels with metabolic syndrome and carotid artery intima-media thickness. The cardiovascular risk in young Finns study. Atherosclerosis 217, 234–239 (2011).

Kim, J. Y. et al. Prospective study of serum adiponectin and incident metabolic syndrome: the ARIRANG study. Diabetes Care. 36, 1547–1553 (2013).

Lindberg, S. et al. Low adiponectin levels at baseline and decreasing adiponectin levels over 10 years of follow-up predict risk of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab. 43, 134–139 (2017).

Nakashima, R., Yamane, K., Kamei, N., Nakanishi, S. & Kohno, N. Low serum levels of total and high-molecular-weight adiponectin predict the development of metabolic syndrome in Japanese-Americans. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 34, 615–619 (2011).

Seino, Y., Hirose, H., Saito, I. & Itoh, H. High-molecular-weight adiponectin is a predictor of progression to metabolic syndrome: a population-based 6-year follow-up study in Japanese men. Metabolism 58, 355–360 (2009).

Baker, J. F. et al. The adiponectin paradox in the elderly: associations with body composition, physical functioning, and mortality. Journals Gerontology: Ser. A. 74, 247–253 (2019).

Menzaghi, C. & Trischitta, V. The adiponectin paradox for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Diabetes 67, 12–22 (2018).

Fantuzzi, G. Adiponectin and inflammation: consensus and controversy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 121, 326–330 (2008).

Kizer, J. R. Adiponectin, cardiovascular disease, and mortality: parsing the dual prognostic implications of a complex adipokine. Metabolism 63, 1079–1083 (2014).

Noh, H. M. et al. Relationships between cognitive function and body composition among community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 17, 1–9 (2017).

Song, H. J. et al. Gender differences in adiponectin levels and body composition in older adults: Hallym aging study. BMC Geriatr. 14, 1–8 (2014).

Grundy, S. M. et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American heart Association/National heart, Lung, and blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation 112, 2735–2752 (2005).

Seo, M. H. et al. 2018 Korean society for the study of obesity guideline for the management of obesity in Korea. J. Obes. Metabolic Syndrome. 28, 40 (2019).

Wang, Y., Wang, M., Wang, Y. & Irisin A potentially fresh insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying vascular aging. Aging Disease. 15, 2491 (2023).

Sahin-Efe, A. et al. Irisin and leptin concentrations in relation to obesity, and developing type 2 diabetes: A cross sectional and a prospective case-control study nested in the normative aging study. Metabolism 79, 24–32 (2018).

Huh, J. Y. et al. FNDC5 and Irisin in humans: I. Predictors of Circulating concentrations in serum and plasma and II. mRNA expression and Circulating concentrations in response to weight loss and exercise. Metabolism 61, 1725–1738 (2012).

Jia, J. et al. Relationship between Circulating Irisin levels and overweight/obesity: A meta-analysis. World J. Clin. Cases. 7, 1444 (2019).

Li, Y. & Xu, Z. Association between Irisin and metabolic parameters in nondiabetic, Nonobese adults: a meta-analysis. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 14, 152 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Adiponectin and metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. Obesity 16, 172–178 (2008).

Liu, Z. et al. Meta-analysis of adiponectin as a biomarker for the detection of metabolic syndrome. Front. Physiol. 9, 1238 (2018).

Pischon, T. et al. Plasma adiponectin levels and risk of myocardial infarction in men. JAMA 291, 1730–1737 (2004).

Kumada, M. et al. Association of hypoadiponectinemia with coronary artery disease in men. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 23, 85–89 (2003).

Beatty, A. L. et al. Adiponectin is associated with increased mortality and heart failure in patients with stable ischemic heart disease: data from the heart and soul study. Atherosclerosis 220, 587–592 (2012).

Cavusoglu, E. et al. Adiponectin is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality, cardiac mortality, and myocardial infarction in patients presenting with chest pain. Eur. Heart J. 27, 2300–2309 (2006).

Nielsen, M. B. et al. Plasma adiponectin levels and risk of heart failure, atrial fibrillation, aortic valve stenosis, and myocardial infarction: large-scale observational and Mendelian randomization evidence. Cardiovasc. Res. 120, 95–107 (2024).

Przybyciński, J., Dziedziejko, V., Puchałowicz, K., Domański, L. & Pawlik, A. Adiponectin in chronic kidney disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 9375 (2020).

Rafaqat, S. Adipokines and their role in heart failure: A literature review. J. Innovations Cardiac Rhythm Manage. 14, 5657 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all participants of the Hallym Aging Study. We also appreciate the contributions of the study coordinators and staff involved in data collection and management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, YJK and HMN; methodology, YJK and HMN; formal analysis, YJK; data curation, DHK and JYJ; writing—original draft preparation, YJK and HMN; writing—review and editing, HJS, KHP, and JKK; supervision, HJS and KHP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, Y., Song, H.J., Kim, DH. et al. Longitudinal associations of serum Irisin and adiponectin with incident metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and older adults over three years. Sci Rep 15, 44160 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27841-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27841-w