Abstract

Assisted hatching (AH) is a reproductive technique that artificially thins or breaches the zona pellucida to facilitate hatching. Despite its widespread use, there is insufficient evidence to conclude that AH improves pregnancy outcomes, particularly when performed selectively. Here we conducted a retrospective study using the Japan Assisted Reproductive Technology Registry from January 2010 to December 2019. AH was performed in 55.0% of 1,678,872 single embryo transfers (SETs), with higher frequency in advanced age women, frozen-thawed ET cycles, blastocyst transfer cycles, and hormonal replacement cycles. After adjusting for these covariates, the propensity-weighted clinical pregnancy rate (29.6% vs. 31.3%) and live birth rate (21.2% vs. 22.4%) were marginally but significantly lower in the AH group compared to the without-AH group. Moreover, AH increased risks of miscarriage (0.82% increase), multiple pregnancy (0.23% increase), and placenta accreta spectrum (0.12% increase). Subgroup analysis indicated that AH was effective for frozen-thawed blastocyst ET cycles in women under 35 years but worsened pregnancy outcomes in many groups, especially those with fresh or cleavage-stage embryos and women older than 40 years. These findings suggest that the impact of AH on pregnancy outcomes varies based on the characteristics of patients and ET cycles, prompting further discussion of its indications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Assisted hatching (AH) is a technique used in assisted reproduction that facilitates the hatching process by artificially disrupting the zona pellucida, which is the outer layer of the embryo. Hatching failure due to an intrinsic abnormality in the blastocyst or zona pellucida could be a reason for unsuccessful conception. Therefore, AH may improve the chance of embryo hatching and implantation, leading to a successful pregnancy. Despite its widespread use since the 1990s1, there is insufficient evidence to conclude that AH improves pregnancy outcomes. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses reported that AH slightly improved the clinical pregnancy rate (CPR) but did not significantly affect the live birth rate (LBR), and there are concerns that it increases the risk of multiple pregnancy2,3. However, evidence regarding the effect and safety of AH is poor because of inadequate reporting of LBRs and adverse events and the use of different hatching methods. Consequently, major guidelines worldwide have proposed that there is insufficient evidence for the effectiveness of AH, and its implementation is not recommended4,5. On the other hand, AH may be effective for specific groups such as women with poor prognoses2, although there is insufficient evidence to recommend its use in selected groups. To evaluate the clinical significance of AH, a database containing a statistically robust sample size, comprehensive assisted reproductive technology (ART) details, and pregnancy outcomes, including live births, would be helpful.

Japan performs one of the highest numbers of ART cycles globally, with more than 543,000 cycles performed annually, and one in ten births in Japan is the result of such cycles6. In Japan, ART is characterized by the prevalent performance of frozen-thawed embryo transfer (ET) and single ET (SET) and by a high percentage of older patients.

The Japanese Reproductive Guidelines published in November 2021 state that it is permissible to perform AH depending on the case. The choice of whether to conduct AH is made based on the patient’s condition and the treatment policy of the ART center or physicians in Japan.

In this study, we evaluated the effectiveness of AH using the ART registration system and extracted factors that contribute to its treatment outcomes. These results will help to determine whether to implement AH and its indications.

Results

Basic description

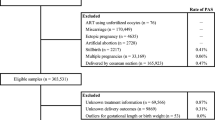

A flowchart of ET cycles is shown in Fig. 1. Of 1,678,872 SET cycles conducted between 2010 and 2019, AH was performed in 924,142 (55.0%). Figure 2 illustrates the trends in the number of SETs and the rate of AH in Japan from 2010 to 2019. With the increase in the number of SET cycles conducted, the rate of AH increased from 42.9% in 2010 to 65.2% in 2019. The rate of AH for frozen-thawed embryos increased from 60.9% in 2010 to 73.6% in 2019, while the rate of AH for fresh embryos remained stable from 2010 (19.2%) to 2019 (20.2%). The temporal change in the rate of AH did not differ according to maternal age, embryo stage at ET, or method of endometrial preparation (Supplementary Fig. S1).

To investigate preferences for performance of AH, the rate of AH was assessed at individual ART facilities (Supplementary Fig. S2). In 2010, of 552 registered ART facilities, 538 conducted ETs; 215 of these did not utilize AH, whereas 70 performed AH in more than 80% of SET cycles. Conversely, in 2019, of 597 registered ART facilities, 585 conducted ETs; 130 of these did not utilize AH, whereas 216 performed AH in more than 80% of SET cycles.

Table 1 delineates the characteristics of individuals whose embryos underwent AH and those whose embryos did not. According to a criterion of standardized mean difference (SMD) of 0.1 or above, the imbalanced variables prior to weighing were type of transferred embryo, embryo stage at ET, indication of unexplained infertility, and method of endometrial preparation. After weighing, all SMDs measured 0.01 or below. There was a trend toward performing AH when maternal age was older than 40 years and not performing it when maternal age was younger than 35 years. AH was more frequently performed in frozen-thawed ET cycles, blastocyst transfer cycles, and hormone replacement cycles. There was a slight tendency for AH not to be performed in patients diagnosed with unexplained infertility.

Impact of AH on pregnancy outcomes

In crude analysis of all SET cycles, the CPR and LBR were significantly higher in the AH group than in the non-AH group (Table 2). In the AH and non-AH groups, the CPR was 32.8% and 28.0%, respectively, while the LBR was 23.2% and 20.3%, respectively. The incidences of miscarriage, placenta accreta spectrum (PAS), and multiple pregnancy were slightly higher in the AH group than in the non-AH group. Conversely, the incidences of ectopic pregnancy and placenta previa were marginally lower in the AH group than in the non-AH group.

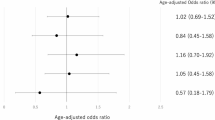

Subgroup analysis according to maternal age, type of transferred embryo (fresh or frozen-thawed), and embryo stage at ET (cleavage or blastocyst) was performed to identify the parameters that influence the outcome of AH (Fig. 3 for live birth and Supplementary Fig. S3 for clinical pregnancy). The LBR was slightly higher in the AH group (37.6%) than in the non-AH group (36.9%) for frozen-thawed blastocyst ET cycles in women younger than 35 years. Conversely, the CPR and LBR were lower in the AH group than in the non-AH group for fresh cleavage-stage ET cycles in women of all ages, frozen-thawed cleavage-stage ET cycles in women older than 35 years, frozen-thawed blastocyst ET cycles in women older than 40 years, and fresh blastocyst ET cycles in women younger than 35 years. For frozen-thawed cleavage-stage ET cycles in women younger than 35 years, the CPR was lower in the AH group than in the non-AH group, but the LBR did not significantly differ between the AH and non-AH groups.

Subgroup analysis of live births. Subgroup analysis was performed separately for subgroups categorized according to maternal age, type of transferred embryo (fresh or frozen-thawed), and embryo stage at embryo transfer (cleavage or blastocyst), which were particularly significant confounding variables. AH, assisted hatching.

In propensity score-weighted analysis of all SET cycles adjusted for five covariates, namely maternal age, type of transferred embryo (fresh or frozen-thawed), embryo stage at ET (cleavage or blastocyst), ART indication, and endometrial preparation, both the CPR (29.6% vs. 31.3%; difference − 1.64% [95% confidence interval: -1.80%, -1.48%]) and LBR (21.2% vs. 22.4%; difference − 1.20% [95% confidence interval: -1.34%, -1.06%]) were marginally lower in the AH group than in the non-AH group (Table 3). As secondary outcomes, AH elevated the risks of miscarriage (0.82% increase), multiple pregnancy (0.23% increase), and PAS (0.12% increase).

In propensity score-weighted subgroup analysis incorporating five variables, namely, maternal age, type of transferred embryo (fresh or frozen-thawed), embryo stage at ET (cleavage or blastocyst), indication for ART, and endometrial preparation, the AH group exhibited a positive risk difference for the LBR and a P-value less than 0.05 compared with the non-AH group for frozen-thawed blastocyst ET cycles in women younger than 35 years (37.7% versus 36.6%). However, AH reduced the LBR in most groups, including fresh cleavage-stage ET cycles in women aged < 35, 35–39, and ≥ 40 years (difference of -4.25%, -2.87%, and − 1.14%, respectively, and excess risk ratio of -17.67%, -17.33%, and − 23.85%, respectively), fresh blastocyst ET cycles in women younger than 35 and older than 40 years (difference of -2.10% and − 0.72%, respectively, and excess risk ratio of -6.80% and − 7.90%, respectively), frozen-thawed cleavage-stage ET cycles in women aged 35–39 years (difference of -0.88% and excess risk ratio of -5.25%), and frozen-thawed cleavage-stage or blastocyst ET cycles in women older than 40 years (difference of -0.76% and − 3.17%, respectively, and excess risk ratio of -12.44% and − 18.42%, respectively) (Table 4). The results of the subgroup analysis for the CPR were identical to those of the subgroup analysis for the LBR (Supplementary Table S1).

Discussion

Our large retrospective cohort study of more than 1.6 million SET cycles demonstrated that AH is not recommended in all cases because it may worsen pregnancy outcomes and increase the risk of complications. Subgroup analysis revealed that AH reduced the CPR and LBR in many groups classified by maternal age, type of transferred embryo (fresh or frozen-thawed), and embryo stage at ET (cleavage or blastocyst). Conversely, AH may be effective for certain groups of patients, e.g., women younger than 35 years who undergo frozen-thawed blastocyst ET cycles.

AH is offered as an add-on treatment in many ART facilities worldwide, but its utilization is not well understood. This study clarified the trends in AH utilization from 2010 to 2019 in Japan. AH was performed in more than half of all SET cycles, with a preference in women of advanced age, frozen-thawed embryo and blastocyst ET cycles, and hormone replacement cycles. Both the rate of AH and the number of facilities with an AH utilization rate higher than 60% have increased despite many unfavorable findings about the clinical significance of AH over the past decade.

To investigate the efficacy of AH, the CPR and LBR for all patients were assessed as primary outcomes. Crude analysis revealed that the CPR and LBR were higher in the AH group than in the non-AH group. It is possible that treatment selection bias, i.e., AH is more frequently used for frozen-thawed blastocysts with basically good treatment outcomes, affected the results as a confounding factor. In propensity score analysis adjusted for five covariates, namely, maternal age, type of transferred embryo (fresh or frozen-thawed), embryo stage at ET, ART indication, and endometrial preparation, the CPR and LBR were slightly lower in the AH group than in the non-AH group. The absolute risk differences are statistically significant but small, such as a -1.20% decrease in LBR. The clinical significance of such a small difference may be minimal for an individual patient; however, applying even a 1% absolute reduction in LBR to a population level translates to a substantial number of lost live births. Previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses reported that AH slightly improved the CPR, but did not significantly affect the LBR, while the quality of the evidence was low because of a serious risk of bias2,3. Many studies demonstrating the efficacy of AH employed hatching methods that are not used today, although laser AH has been the most widespread technique over the past few decades7. Additionally, the development of laboratory technologies, including in vitro culture and cryopreservation, may have diminished the advantages of AH.

Subsequently, the efficacy of AH was assessed based on the background of patients and ET cycles. Subgroup analysis according to three confounding variables, namely, maternal age, type of transferred embryo (fresh or frozen-thawed), and embryo stage at ET (cleavage or blastocyst), indicated that AH is effective for frozen-thawed blastocyst ET cycles in women younger than 35 years in terms of both the CPR and LBR. By contrast, AH negatively affected fresh and frozen-thawed cleavage-stage ET cycles in women of all ages, frozen-thawed blastocyst cycles in women older than 40 years, and fresh blastocyst cycles in women younger than 35 years. In another subgroup analysis of inverse probability weighting utilizing a propensity score model that included five variables, AH was only effective for frozen-thawed blastocyst ET cycles in women younger than 35 years. The risk difference manifests as a 1.07% increase in LBR, indicating a positive effect, but a relatively small one. On the other hand, AH was ineffective in most groups; in particular, the LBR was significantly decreased in the AH group for fresh cleavage-stage ET cycles in women of all ages. Interestingly, the LBR was decreased in the AH group for frozen-thawed blastocyst ET cycles in women older than 40 years, demonstrating that the impact of AH on frozen-thawed blastocysts differs according to maternal age. Furthermore, in women younger than 35 years, the LBR was decreased in the AH group for ET cycles using fresh cleavage-stage embryos (4.3% decrease) and fresh blastocysts (2.1% decrease). Considering that the LBR was increased in the AH group for frozen-thawed blastocyst ET cycles in women younger than 35 years, AH may ameliorate the changes caused by freezing and thawing in embryos of younger women, and its potential benefits may be more pronounced for blastocysts than for cleavage-stage embryos. LBR in fresh ET in women younger than 35 years declined more than in those aged 35–39 and over 40 years, suggesting that the disadvantages of AH for fresh embryos have a stronger impact on younger women.

There are several possible mechanisms by which AH may improve embryo implantation and pregnancy outcomes, including those involving hardening of the zona pellucida due to in vitro fertilization, cell culture, or cryopreservation, and exchange of metabolites, growth factors, and messages between the embryo and endometrium8. Previous reports indicate that AH is effective for specific groups, particularly women who have suffered repeated implantation failure(RIF)2,9, are of advanced age10, undergo transfer of frozen embryos11,12, and whose embryos have a thick zona pellucida8; however, the results are inconsistent13,14,15.

There is limited research regarding age-related differences in the effect of AH. Although some studies reported that AH is efficacious in women of advanced age, the inconsistency of the results and the differences in age categorization between studies make it difficult to assess the impact of AH according to age. It has also been reported that the thickness of the zona pellucida diminishes with age8,16,17, whereas other reports suggested that it is strongly influenced only by embryo quality not by maternal age18. The thick zona pellucida of embryos of young women may complicate hatching following the freeze-thaw procedure, and AH may improve pregnancy results.

Our study identified a notable decline in both the CPR and LBR attributable to AH in most groups, especially in women older than 40 years. The mechanism by which AH worsens pregnancy outcomes has not been elucidated. AH may directly or indirectly damage embryos, potentially having a stronger impact on aged women. In both the AH and non-AH groups, the CPR and LBR were significantly lower in women older than 40 years than in those younger than 35 years and aged 35–39 years, which is consistent with the previous finding that embryo quality declines with increasing age due to a reduction of euploid embryos and various factors19,20. Given that the zona pellucida can reflect embryo quality, even if AH resolves hatching failure, it may not lead to successful implantation and pregnancy.

Interestingly, a decrease in the CPR and LBR due to AH was observed in fresh ET cycles among women under 35 years. These findings are consistent with a previous report that AH reduces LBR in both good and poor prognosis patients undergoing fresh ETs and that in good prognosis patients, the reduction in LBR was greater with cleavage-stage embryos than with blastocysts21. Age-related differences have been reported in the mechanical properties of the zona pellucida, such as elasticity and stiffness, as well as its structure22,23. Fresh embryos from younger women do not require intervention, and unnecessary manipulation can hinder implantation success by causing the release of substances related to maintaining embryo quality and implantation success or by inducing an embryo-endometrial asynchrony.

Finally, the risk of complications with AH were examined as secondary outcomes. Crude analysis indicated that the incidences of miscarriage, PAS, and multiple pregnancy were marginally higher in the AH group than in the non-AH group, while the incidences of ectopic pregnancy and placenta previa were marginally lower. Propensity score analysis adjusted for five covariates suggested that AH may increase the risks of adverse events such as multiple pregnancy, miscarriage, and PAS. Given the initial low incidences of these complications, it is important to exercise caution when interpreting the clinical impact of the risk differences.

The possibility that AH increases the risk of multiple pregnancy has been recognized, but the relationship between AH and other perinatal complications remains unclear. Previous reviews and meta-analyses suggest that AH increases the risks of multiple pregnancy2,3,24 and monozygotic twinning21,24. It has also been suggested that manipulations of the zona pellucida, such as AH, are potential risk factors for herniation of blastomeres through the zona and embryo division during blastocyst expansion25.

In this study, the miscarriage rate after adjustment was 25.6% in the AH group and 24.8% in the non-AH group. Previous meta-analyses and systematic reviews consistently reported that the miscarriage rate does not significantly differ according to whether AH is performed, although the quality of evidence is low3,26. The risk of miscarriage is affected by various background factors, such as maternal age, history of miscarriage, obesity, and perinatal complications. In this study, the database did not include information on pregnancy, childbirth history, or maternal complications that could increase the risk of miscarriage; therefore, it is possible that these factors increased the miscarriage rate in the AH group.

The incidence of PAS after adjustment was 0.73% in the AH group and 0.62% in the non-AH group. The most important risk factor for PAS is previous cesarean section, whereas advanced maternal age, embryo stage, and frozen-thawed ET, particularly with hormone replacement cycles, are independent risk factors27. There are limited reports about the impact of AH on PAS28. Nonetheless, given the extremely low incidence of PAS, caution is needed when interpreting the clinical significance of this marginal rise in the incidence of PAS.

This study has some limitations. First, the database used did not include information on the history of RIF and embryo quality at ET. It is highly plausible that clinicians performed AH more frequently on poorer-quality embryos or for patients with a history of RIF, the residual confounding would bias the results against AH. However, the E-value for the estimated risk difference of − 1.64% was 1.3 (almost the same for the 95% confidence limit), indicating that this risk difference could be explained away by an unmeasured confounder associated with both the treatment and the outcome by a risk ratio of 1.3 beyond the measured confounders, whereas weaker confounding could not do so. We believe that our results are unlikely to be substantially altered by such unmeasured confounding29. Second, the database did not contain information regarding the method of AH. Various approaches employed for AH may have varying efficacies and safety profiles. Laser-assisted hatching is presumably the predominant technique utilized in Japan, similar to global trends; however, no survey has been conducted on its actual utilization. The inability to stratify by technique is a limitation of this study. Third, there were cases where data of the same patient who received multiple ETs overlapped for SET cycles.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first retrospective observational study to investigate the clinical significance of AH based on the entire population as well as various groups using the highest number of ET cycles.

In conclusion, AH should not be conducted routinely for all cycles. AH may be advantageous for young women who undergo transfer of frozen-thawed blastocysts, but may worsen pregnancy outcomes in other groups, particularly older women and women who undergo cycles with fresh embryos, indicating that its utilization should be carefully considered. Future research is required to investigate the mechanism underlying the variability in the effectiveness of AH.

Methods

Data source

The Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) established an ART registry system in 1986, which identifies authorized facilities for ART and mandates the reporting of treatment procedures and outcomes. Consequently, more than 99% of ART treatment cycles were recorded in this registry from around 600 participating facilities annually. The cycle-based registry form was previously described30. To evaluate the impact of AH on ART, the following data were extracted from the registered ART database: patient age at initiation of the ART cycle, indication for ART, type of transferred embryo (frozen-thawed or fresh), embryo stage at ET (cleavage or blastocyst), endometrial preparation, fertilization procedures, number of transferred embryos, application of AH, number of gestational sacs and fetuses, courses of pregnancy, and number and findings of live-born infants. The registration of items describing the presence or absence of AH began in 2010 and ended in 2019. Data concerning the methods of AH (e.g., laser, chemicals, or mechanical), history of RIF, and embryo quality were not available. The database also did not contain data on the implementation of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A). PGT-A was prohibited in Japan for a long time, and the only PGT performed within the period covered by this study was in a multi-centre, prospective pilot study conducted from 2017 to 2018. This study includes 21 cases where euploid embryos were acquired with PGT-A and subsequently transferred31. The inclusion of embryos that underwent PGT-A could lead to an underestimation of AH, but the sample size of PGT-A cases in this study is too small to affect the results.

Study population

The analytical population was limited to SET cycles conducted from January 2010 to December 2019. In total, 1,754,412 (80.6%) of 2,176,700 ET cycles were SETs (Fig. 1). Among them, cycles with absent or incomplete data concerning the following were excluded: type of transferred embryo (fresh or frozen-thawed), embryo stage at ET (cleavage or blastocyst), and application of AH. A total of 1,678,872 SET cycles were ultimately analyzed. The primary outcomes were clinical pregnancy and live birth, whereas the secondary outcomes included miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, placenta previa, PAS, and multiple pregnancy. Clinical pregnancy was defined by an intrauterine sac with or without a fetal heartbeat, and multiple pregnancy was defined by the presence of more than two fetuses visualized by ultrasound examination.

Statistical analyses

The number of SETs, implementation of AH, and characteristics of ART facilities in Japan were summarized graphically. The frequencies and proportions of background characteristics were calculated for both the AH and non-AH groups, and SMD was calculated. An SMD of 0.1 or higher indicated a significant difference between the groups32. Subsequently, three distinct analyses were performed.

The first analysis was a crude analysis involving the calculation of the frequencies and proportions of clinical outcomes in the AH and non-AH groups, which were compared using the chi-squared test. The CPR and LBR were calculated relative to the number of SET cycles. The rates of miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, and multiple pregnancy were calculated relative to the number of clinical pregnancies. The rates of placenta previa and PAS were calculated relative to the number of live births.

The second analysis focused on clinical pregnancy and live birth for subgroups categorized according to maternal age, type of transferred embryo (fresh or frozen-thawed), and embryo stage at ET (cleavage or blastocyst), which were particularly significant confounding variables.

The third analysis performed inverse probability weighting utilizing a propensity score model that incorporated five variables, namely, maternal age, type of transferred embryo (fresh or frozen-thawed), embryo stage at ET (cleavage or blastocyst), indication for ART, and endometrial preparation. These variables were selected by the common cause criterion33. The propensity score was estimated with a logistic regression model. Under several assumptions, including that the five variables were sufficient to control for confounding, the outcomes of the propensity score analysis could be utilized to investigate causation instead of mere association, specifically comparing the counterfactual situation in which all members of the population had received AH with the situation in which they had not34. Standard errors were calculated with a robust variance estimator, and Wald-type confidence intervals were determined.

Inverse probability weighting analysis was also performed using propensity scores by subgroup, i.e., conditional average treatment effects were also estimated. Missing data were not imputed and a complete case analysis was performed. All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Analysis System version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Data availability

The data supporting the results of this study are not accessible to the public due to confidentiality concerns. However, they are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Cohen, J. et al. Impairment of the hatching process following IVF in the human and improvement of implantation by assisting hatching using micromanipulation. Hum. Reprod. 5, 7–13 (1990).

Martins, W. P., Rocha, I. A., Ferriani, R. A. & Nastri, C. O. Assisted hatching of human embryos: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Hum. Reprod. Update. 17, 438–453 (2011).

Lacey, L., Hassan, S., Franik, S., Seif, M. W. & Akhtar, M. A. Assisted hatching on assisted conception (in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI)). Cochrane Libr. 2021 (2021).

Lundin, K. et al. Good practice recommendations on add-ons in reproductive medicine. Hum. Reprod. 38, 2062–2104 (2023).

Committee, P. & Society, A. The role of assisted hatching in in vitro fertilization: a guideline. Fertil. Steril. 117, 1177–1182 (2022).

Katagiri, Y. et al. Assisted reproductive technology in japan: A summary report for 2021 by the Ethics Committee of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reprod. Med. Biol. 23, 1–11 (2024).

Sciorio, R. et al. Exploring the benefit of different methods to perform assisted hatching in the ART laboratory: A narrative review. Reprod. Biol. 24, 100923 (2024).

Cohen, J., Alikani, M., Trowbridge, J. & Rosenwaks, Z. Implantation enhancement by selective assisted hatching using zona drilling of human embryos with poor prognosis. Hum. Reprod. 7, 685–691 (1992).

Balaban, B. et al. A comparison of four different techniques of assisted hatching. Hum. Reprod. 17, 1239–1243 (2002).

He, F., Zhang, C., Wang, L., si, Li, S. L. & Hu, L. na. Assisted hatching in couples with advanced maternal age: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Med. Sci. 38, 552–557 (2018).

Zeng, M. F., Su, S. Q. & Li, L. M. The effect of laser-assisted hatching on pregnancy outcomes of cryopreserved-thawed embryo transfer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Lasers Med. Sci. 33, 655–666 (2018).

Alteri, A. et al. Revisiting embryo assisted hatching approaches: a systematic review of the current protocols. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 35, 367–391 (2018).

Edi-Osagie, E., Hooper, L. & Seif, M. W. The impact of assisted hatching on live birth rates and outcomes of assisted conception: A systematic review. Hum. Reprod. 18, 1828–1835 (2003).

Curfs, M. H. J. M. et al. A multicentre double-blinded randomized controlled trial on the efficacy of laser-assisted hatching in patients with repeated implantation failure undergoing IVF or ICSI. Hum. Reprod. 38, 1952–1960 (2023).

Knudtson, J. F. et al. Assisted hatching and live births in first-cycle frozen embryo transfers. Fertil. Steril. 108, 628–634 (2017).

Garside, W. T., De Mola, L., Bucci, J. R., Tureck, J. A., Heyner, S. & R. W. & Sequential analysis of zona thickness during in vitro culture of human zygotes: correlation with embryo quality, age, and implantation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 47, 99–104 (1997).

Gabrielsen, A., Bhatnager, P. R., Petersen, K. & Lindenberg, S. Influence of zona pellucida thickness of human embryos on clinical pregnancy outcome following in vitro fertilization treatment. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 17, 323–328 (2000).

Balakier, H. et al. Is the zona pellucida thickness of human embryos influenced by women’s age and hormonal levels? Fertil. Steril. 98, 77–83 (2012).

Reig, A., Franasiak, J., Scott, R. T. Jr & Seli, E. The impact of age beyond ploidy: outcome data from 8175 euploid single embryo transfers. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 37, 595–602 (2020).

Navot, D. et al. Poor oocyte quality rather than implantation failure as a cause of age-related decline in female fertility. Lancet 337, 1375–1377 (1991).

McLaughlin, J. E. et al. Does assisted hatching affect live birth in fresh, first cycle in vitro fertilization in good and poor prognosis patients? J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 36, 2425–2433 (2019).

Schmitz, C. et al. The E-modulus of the oocyte is a non-destructive measure of zona pellucida hardening. J. Reprod. Fertil. 162, 259–266 (2021).

Ishikawa-Yamauchi, Y. et al. Age-associated aberrations of the cumulus-oocyte interaction and in the zona pellucida structure reduce fertility in female mice. Commun. Biol. 7, 1692 (2024).

Busnelli, A. et al. Risk factors for monozygotic twinning after in vitro fertilization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 111, 302–317 (2019).

Ikemoto, Y. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of zygotic splitting after 937 848 single embryo transfer cycles. Hum. Reprod. 33, 1984–1991 (2018).

Li, D. et al. Effect of assisted hatching on pregnancy outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–9 (2016).

Fujita, T. et al. Risk factors for placenta accreta spectrum in pregnancies conceived after frozen-thawed embryo transfer in a hormone replacement cycle. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 296, 194–199 (2024).

Pan, J. P. et al. Obstetric and neonatal outcomes after frozen–thawed embryos transfer with laser-assisted hatching: a retrospective cohort study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 305, 529–534 (2022).

VanderWeele, T. J. & Ding, P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann. Intern. Med. 167, 268–274 (2017).

Irahara, M. et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: a summary report of 1992–2014 by the Ethics Committee, Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reprod. Med. Biol. 16, 126–132 (2017).

Sato, T. et al. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy: a comparison of live birth rates in patients with recurrent pregnancy loss due to embryonic aneuploidy or recurrent implantation failure. Hum. Reprod. 34, 2340–2348 (2019).

Austin, P. C. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. 3038–3107 (2009).

VanderWeele, T. J. Principles of confounder selection. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 34, 211–219 (2019).

Hernan, M. A. & Robins, J. M. Causal Inference: What If April 26 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315374932 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to JSOG for their generosity in providing the data and acknowledge all the clinics that participated in the Japanese ART registry for their unwavering support with the data collection.

Funding

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (23K19667 and 25K20080 to A.K., 22K09614 to M.H., 23K08816 to Y.U., and 24K23506 to H.K.), by the Children and Families Agency (25DB0201 to M.H. and Y.O., and 23DB0101 to Y.O.), and by a grant from the National Center for Child Health and Development (2025B-10 to Y.U.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. contributed to study design, execution, analysis, manuscript drafting, and critical discussion. M.H. contributed to study conception and design, critical discussion, and manuscript drafting. T.K. participated in analysis, critical discussion, and manuscript drafting. H.K., C.K., Y.F., Y.S., N.T., M.M., T.M., Y.U., G.I., N.O., and O.H. participated in critical discussion. Y.O. and Y.H. participated in critical discussion and project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Registration and Research Subcommittee of the JSOG and the University of Tokyo Ethics Committee.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kusamoto, A., Harada, M., Kawahara, T. et al. Effect of assisted hatching on pregnancy outcomes following 1,678,872 single embryo transfers based on the Japan Assisted Reproductive Technology Registry. Sci Rep 15, 40508 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27867-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27867-0