Abstract

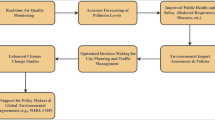

Air pollution, a major global health and environmental threat, necessitates accurate forecasting to support timely interventions and policy-making. Data-driven approaches, increasingly powered by artificial intelligence (AI), have gained traction in air quality prediction, leveraging their capacity to model complex, nonlinear patterns in environmental data. Deep learning models, such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, excel at capturing temporal dependencies but are hindered by their discrete-time framework, overlooking the continuous dynamics of air pollution driven by physical and chemical processes. This limitation compromises their performance, especially with irregular or sparse observations. Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (Neural ODEs), introduced in 2018, offer a continuous-time modeling paradigm by parameterizing derivatives with neural networks, yet their application to environmental sciences remains underexplored, with many implementations retaining single-scale latent dynamics and lacking calibrated uncertainty estimates. Here, we present a novel Multi-timescale Attention Neural ODE (MA-NODE) framework for multi-step air pollution forecasting, marking one of the first such efforts to our knowledge. Its continuous-time formulation reduces multi-step discretization error and natively accommodates irregular sampling, addressing key limitations of discrete-time deep models. Our model decomposes latent dynamics into fast, medium, and slow timescales, reflecting diverse temporal behaviors, and integrates an attention mechanism to enhance feature synthesis. Evaluated on real-world datasets encompassing PM2.5, O3, NO2, SO2, CO, and PM10, it achieves an R² exceeding 0.9 for three-step-ahead predictions, outperforming traditional and state-of-the-art methods, with 10–15% lower MAE/RMSE and well-calibrated 95% interval coverage (≈ 0.90). This work advances air quality forecasting by harnessing Neural ODEs’ continuous modeling capabilities, while operating directly on station observations without gridded meteorology, offering a robust tool for environmental management. By bridging computational innovation with ecological needs, it paves the way for broader Neural ODE applications in environmental science, strengthening public health and sustainability efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Air pollution remains a critical global challenge, with profound implications for public health, environmental sustainability, and economic stability1,2. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 99% of the global population breathes air exceeding its guideline limits, contributing to approximately 7 million premature deaths annually, primarily from exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO₂), and ozone (O₃) (WHO, 2023). These pollutants are linked to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, with significant socioeconomic costs, particularly in urban areas where air quality dynamics are complex and variable. Accurate forecasting of air pollutant concentrations is essential for enabling proactive measures, such as issuing health advisories, optimizing emission controls, and informing urban planning, thereby mitigating exposure risks and supporting sustainable development goals3,4.

Historically, air quality forecasting has relied on two primary methodologies: physics-based models and data-driven approaches, each with notable shortcomings. Physics-based models, such as Chemical Transport Models (CTMs), simulate atmospheric processes using differential equations to model pollutant dispersion via diffusion and advection5,6. These models offer interpretability by grounding predictions in physical principles, such as mass conservation and meteorological interactions. However, they are computationally intensive, often requiring significant resources for high-resolution, real-time predictions, and frequently assume closed-system dynamics, which fail to capture the open, boundary-influenced nature of real-world air quality systems7. For instance, CTMs may overlook the effects of external pollutant sources (e.g., industrial emissions) and sinks (e.g., natural absorption by forests), limiting their accuracy in open environments.

Data-driven models, particularly deep learning techniques like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), have gained prominence for their ability to uncover complex spatiotemporal patterns from historical data8. LSTMs excel at modeling temporal dependencies, while GNNs capture spatial correlations, making them suitable for air quality prediction in networked sensor systems9,10,11,12. However, these models treat air quality as a “black box,” lacking physical interpretability, which is crucial for understanding and trusting their predictions, especially in scenarios with sparse or irregular data13. Their performance can degrade in data-scarce regions or during sudden pollution events, and their discrete-time framework may miss the continuous evolution of pollutant concentrations, driven by physical and chemical processes.

Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (NODEs), first introduced by R. T. Q. Chen et al.14, provide a groundbreaking framework for modeling continuous-time dynamics by parameterizing the derivative of the hidden state with a neural network. Building on this, Deng et al.15,16 extended the framework by utilizing multiple Neural Ordinary Differential Equations to enhance dynamic message propagation, improving temporal dependency representation. Similarly, Xhonneux et al.17 proposed the Continuous Graph Neural Networks (CGNN) framework, employing Neural Ordinary Differential Equations to maintain continuous graph node states, overcoming limitations of discrete graph neural networks. This approach is particularly well-suited for environmental systems, where pollutant concentrations evolve smoothly over time under the influence of factors such as emission rates, meteorological conditions, and atmospheric chemistry. Unlike discrete-time models, NODEs adeptly handle irregular sampling intervals, a frequent challenge in air quality monitoring due to sensor failures or varying measurement frequencies, while also reducing memory usage through the adjoint method for gradient computation18. Furthermore, their capacity to embed physical constraints via differential equations enhances interpretability, effectively bridging the gap between data-driven and physics-based methods.

Recent efforts have sought to further bridge these paradigms through hybrid approaches, integrating physical knowledge into data-driven frameworks. For example, Tian et al.7 proposed a physics-informed dual Neural ODE model for air quality prediction in open systems, demonstrating improved accuracy by aligning neural network dynamics with physical equations. Similarly, Hettige et al.13 introduced AirPhyNet, a physics-guided neural network that incorporates diffusion and advection principles into graph-based learning, enhancing both prediction accuracy and interpretability. These studies highlight the potential of combining computational innovation with domain-specific knowledge, yet they often focus on specific aspects, such as spatial scales or short-term predictions, leaving room for advancements in multi-step, continuous-time forecasting.

In related domains like traffic forecasting, NODEs have also shown significant promise. Fang et al.19 pioneered the Spatio-Temporal Graph Ordinary Differential Equation (STGODE) model, which employs ordinary differential equation techniques on traffic networks to achieve continuous spatial propagation, though its temporal dimension remains discrete. Addressing this limitation, Jin et al.20 developed the Multi-Timescale Graph Ordinary Differential Equation (MTGODE) model, featuring a dynamic graph-based NODE structure for unified continuous message passing across both spatial and temporal dimensions, despite its high computational cost for long-term sequences. Liu et al.21 further advanced this domain with the Graph-based Recurrent Attention Mechanism with Ordinary Differential Equations (GRAM-ODE) model, utilizing coupled ordinary differential equation-graph neural network blocks to capture complex local and global spatiotemporal dependencies, improving long-term prediction accuracy at the expense of increased computational complexity. These traffic forecasting models underscore the importance of multi-level spatiotemporal features. K. Guo et al.22 highlight that global spatiotemporal features offer a superior macroscopic representation of transportation systems compared to local features alone. Models like STGODE and GRAM-ODE integrate local node-level dependencies with global semantic matrices to enhance predictive performance.

The versatility of NODEs has recently gained significant attention in diverse prediction and simulation tasks beyond environmental applications, including traffic, climate, and weather forecasting23,24,25,26,27,28,29. However, despite their promise, the application of Neural ODEs to short-term air pollution forecasting remains underexplored. While recent studies have demonstrated their efficacy in air pollution systems, but few have addressed the need for multi-step, multi-timescale predictions using daily observations. This gap is particularly significant given the diverse temporal patterns in air quality data, ranging from rapid fluctuations due to local emissions to gradual trends driven by seasonal cycles.

Summary of research gaps and study contributions

Conventional deep learning approaches to air quality forecasting—including LSTMs, Transformers, and CNNs—process temporal sequences through discrete-time updates with fixed resolution, introducing discretization errors that compound in multi-step predictions while providing limited physical interpretability. Recent hybrid physics-guided models have attempted to address interpretability through advection-diffusion integration, yet require computationally intensive PDE solvers and gridded meteorological inputs that constrain practical deployment.

Among continuous-time modeling frameworks, Neural ODEs (NODEs) have attracted attention for their potential alignment with atmospheric dynamics, yet four critical research gaps limit their operational application. First, while traffic-domain NODEs (STGODE, MTGODE, GRAM-ODE) have advanced continuous spatial propagation, their temporal integration remains discrete with predetermined step sizes, not fully leveraging adaptive ODE solvers for multi-scale pollutant evolution. Second, physics-guided NODE implementations7,13 rely on external gridded wind fields and explicit PDE solvers, creating deployment barriers for sparse station-based monitoring—the predominant scenario in urban environments. Third, existing NODE architectures encode temporal dynamics within a single latent representation, potentially causing spectral interference when simultaneously capturing rapid emission events, meteorological cycles, and seasonal patterns spanning orders of magnitude. Fourth, probabilistic forecasting capabilities remain limited, with most implementations producing point predictions without well-calibrated uncertainty intervals essential for risk-based public health decision-making.

Addressing these gaps requires a NODE framework that enables multi-scale temporal representation without spectral contamination, provides regime-aware forecasting adaptable to changing atmospheric conditions, delivers probabilistic uncertainty quantification with physically plausible trajectories, and operates directly on station observations without external meteorological grids. The advantages of continuous-time formulation over discrete architectures lie in adaptive numerical integration—where ODE solvers automatically adjust evaluation substeps during rapid concentration changes (e.g., morning traffic surges)—reducing multi-step error accumulation that fixed-timestep models exhibit, while memory-efficient adjoint gradients enable deeper temporal modeling within computational constraints. These design choices are anticipated to improve multi-step forecasting accuracy (particularly for pollutants with strong diurnal-seasonal superposition like PM2.5 and O₃) and provide well-calibrated uncertainty bounds critical for public health advisories. To systematically evaluate whether such continuous-time formulation provides measurable advantages, baseline models spanning complementary inductive biases—Transformer (global attention), LSTM/GRU (sequential gating), CNN (local convolution), FCNN (position-independent transformation)—serve as reference points against which NODE-specific contributions can be isolated.

This study introduces a novel multi-timescale Neural ODE architecture for multi-step air pollution forecasting, specifically designed to predict daily pollutant levels three steps ahead with high accuracy. Our approach decomposes the latent dynamics into fast, medium, and slow timescales, capturing phenomena such as sudden pollution spikes from traffic, medium-term variations due to weather changes, and slow seasonal shifts. This decomposition enhances interpretability by aligning with known physical processes: fast dynamics reflect short-term, localized emissions; medium dynamics capture meteorological influences like wind patterns; and slow dynamics model long-term trends, such as seasonal cycles. An attention-based fusion mechanism integrates these components, dynamically weighing their contributions to improve predictive precision, offering insights into the relative importance of each timescale for different pollutants.

The model’s interpretability is further supported by its continuous-time framework, which allows for visualization of how pollutant concentrations evolve over time, akin to solving differential equations. For instance, the rate of change in PM2.5 concentrations can be analyzed to understand the impact of emission sources versus natural dispersion, providing a transparent link to physical mechanisms. This interpretability is crucial for environmental scientists and policymakers, enabling trust in the model’s predictions for real-world applications.

Evaluated on comprehensive real-world datasets encompassing PM2.5, O₃, NO₂, SO₂, CO, and PM10, our model achieves a superior R² for three-step-ahead forecasts, significantly outperforming traditional statistical methods (e.g., ARIMA) and state-of-the-art deep learning approaches (e.g., LSTMs, Transformer). This high accuracy across all pollutants, combined with the model’s ability to handle irregular sampling intervals, positions it as a robust tool for air quality management. By leveraging Neural ODEs, we address the limitations of discrete-time models, offering a scalable, interpretable solution that supports timely interventions and evidence-based policymaking. This research contributes to the intersection of computational science and environmental research, providing a pioneering application of multi-timescale Neural ODEs to air pollution forecasting. It not only advances predictive accuracy but also fosters a deeper understanding of the complex systems governing air quality, with implications for public health initiatives and sustainable development goals.

Methods and material

Case study area

The study area. a) Map of Iran: the green area represents Iran’s capital, Tehran; b) Map of Tehran province: the red-coloured area represents the main urban area of the study. The map was created using ArcGIS Pro version 3.2 (Esri Inc., Redlands, CA, USA; https://www.esri.com), utilizing basemap imagery provided by Esri, Maxar, Earthstar Geographics, and the GIS User Community.

Located at 35°41′N, 51°26′E, Tehran stands as a major urban hub in the Middle East, covering an area of 730 km² and divided into 22 administrative districts. The city supports a population of 9.6 million, with an additional 7 million daily commuters contributing to its bustling activity. Situated at elevations ranging from 900 to 1800 m above sea level, Tehran experiences a cold semi-arid climate characterized by a wide temperature range, from − 15 °C in winter to 43 °C in summer. A consistent thermal gradient exists across the city, with the northern districts being 2–3 °C cooler than the southern ones. Annual climate averages include a temperature of 17 °C, precipitation of 270 mm, and relative humidity of 40%, which might suggest moderate conditions. However, Tehran’s air quality is severely compromised due to its topographic setting—flanked by mountains that, combined with prevailing westerly winds, create a basin effect, trapping atmospheric pollutants, especially during colder months. This environmental challenge is exacerbated by intense urban activity, including industrial operations and approximately 17 million daily vehicle trips, which significantly elevate pollutant levels30,31,32.

The study area, delineated in red on Fig. 1, encompasses segments of 10 districts and was selected following an extensive literature review. This region was chosen for its persistent air pollution patterns observed between 2009 and 2022, as well as the availability of comprehensive and reliable air quality and meteorological datasets with minimal missing entries33,34.

Data collection and preprocessing

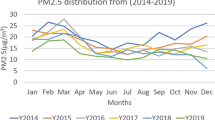

Data on air pollutants for this research were sourced from the Tehran Air Quality Control Company, spanning the period from 2015 to 2024, collected across 26 monitoring stations and aggregated into daily averages. The study concentrated on daily levels of critical pollutants, including PM10, PM2.5, NO₂, SO₂, CO, and O₃. Within the designated study area, 11 monitoring stations were utilized, and spatial interpolation was performed using a co-kriging method, with air quality data as the primary variable. Complementary meteorological data, obtained from the Iran Meteorological Organization, served as the secondary variable, encompassing parameters such as humidity, precipitation, temperature metrics (dew point and apparent temperature), wind characteristics (speed and direction), and atmospheric pressure. Variations in station installation timelines and maintenance activities resulted in missing values following a missing completely at random (MCAR) pattern. Despite the study area’s relatively high data integrity, a thorough imputation strategy was employed to maximize accuracy. A dual-model imputation framework was designed, combining Graph Neural Networks with an iterative Random Forest-based approach, both fine-tuned via Bayesian hyperparameter optimization. For air quality variables, an iterative Random Forest imputer was selected due to its superior performance, refining imputed values iteratively based on enhanced R² and MSE scores over 10 experimental runs35,36. The interpolated pollutant data underwent log-transformation to normalize skewed distributions and were subsequently smoothed to improve the clarity of temporal trends, as depicted in Fig. 2. Additionally, the selected air pollutants were statistically analyzed and summary of variables are presented in Table 1.

Neural decomposition & temporal encoding

To enhance transparency, the preprocessing steps implemented in this study are depicted in Fig. 3. Building on this foundation, a rigorous temporal encoding approach was seamlessly integrated into the preprocessing pipeline to effectively capture the temporal characteristics of the time-series data. Temporal features were extracted from the daily timestamps, including year, month, day, day of the week, day of the year, and week of the year, to represent the temporal structure of the data at multiple levels of granularity. Recognizing the cyclical nature of certain temporal features, sinusoidal encoding was employed to ensure the continuity of these cycles and to prevent issues such as artificial discontinuities.

The sinusoidal transformations are defined as (Eq. 1):

where \(\:\left(\:x\:\right)\) is the temporal feature and \(\:\left(\:P\:\right)\) represents its period (e.g.\(\:.,\:(\:P\:=\:12\:)\) for months, \(\:(\:P\:=\:7\:)\) for weekdays, \(\:(\:P\:=\:365\:)\) for the day of the year).

Furthermore, these transformations project periodic features into a multidimensional space where cyclical trends are preserved, allowing the subsequent decomposition and deep learning models to better capture interactions between time-dependent construction activities and pollutant variations. By integrating such encoded temporal features, the framework gains a robust capability to discern temporal dynamics, thereby improving predictive accuracy and enhancing explainability in modeling complex temporal relationships.

To mitigate the influence of extreme values, a percentile-based outlier clipping approach was employed, where pollutant values exceeding the 99th percentile were truncated to this threshold, preserving the overall data distribution while reducing the impact of anomalous measurements that might otherwise compromise model training. To capture the underlying temporal dynamics of pollutants, a novel neural temporal decomposition framework was introduced to extract latent representations capturing the underlying dynamics of air pollutant time series. For each pollutant p, a specialized autoencoder architecture was constructed to project sequential observations into a lower-dimensional manifold. Given a temporal window of length n = 3 for pollutant p, denoted as:

The 3-day window aligns with operational air quality forecasting standards, where 72-hour predictions represent the practical limit for reliable forecasting given meteorological uncertainty constraints. Beyond this horizon, numerical weather prediction errors compound exponentially, degrading forecast skill substantially.

The encoder \(\:{\varvec{E}}_{\varvec{p}}\) and decoder \(\:{\varvec{D}}_{\varvec{p}}\) were defined as:

and

where \(\:{z}_{p}\) ∈ ℝ⁴ represents the latent embedding with dimension d = 4, \(\:{W}_{i}\) and \(\:{b}_{i}\) are learnable parameters, and \(\:{\sigma\:}_{i}\) denotes ReLU activation functions. The autoencoder was trained to minimize the reconstruction error:

enabling the extraction of temporal pattern embeddings that provided the model with compact representations of cyclical, trend, and irregular components of each pollutant time series. For each time step, a sliding window generated these embeddings, resulting in four additional features per pollutant that adaptively learned the most relevant temporal structures for pollution forecasting, outperforming traditional decomposition methods like Seasonal and Trend decomposition using Loess (STL) or Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD). Additionally, autoregressive components were incorporated by generating lagged features for each pollutant at intervals of 1–3 days, which underwent logarithmic transformation. To stabilize variance and normalize their distribution, particularly important for pollutants exhibiting right-skewed concentrations. The feature space was enriched through a systematic selection process that combined the original pollutant measurements, their neural decompositions, transformed lag features, and temporal encodings. To address scale disparities among features, per-feature min-max normalization was applied independently to each dimension. preserving the relative magnitude relationships while standardizing the value ranges37. Finally, time-aware sequence generation was performed with a sliding window approach, creating input-output pairs where each input comprised an n-day sequence of selected features, and outputs represented the corresponding pollutant concentrations for the subsequent three days, enabling the model to learn the complex temporal dependencies and multi-step forecasting dynamics inherent in urban air quality patterns.

Multi-timescale neural ordinary differential equation framework

Theoretical basis

The Multi-Timescale Neural Ordinary Differential Equation (MT-NODE) framework models air pollutant dynamics as a continuous-time system to capture the non-stationary, multi-scale dependencies inherent in environmental time series (depicted in Fig. 4). Unlike discrete-time models that approximate rapid fluctuations (e.g., traffic-induced NO₂ spikes), intermediate patterns (e.g., weekly O₃ cycles), and slow trends (e.g., seasonal PM₂.₅ variations), MT-NODE employs a coupled system of differential equations:

where.

h(t) ∈ \(\:{\mathbb{R}}^{d}\) is the latent state,

u(t) \(\:\in\:\:{\mathbb{R}}^{\left\{62\right\}}\) integrates control inputs, and.

\(\:{f}_{\theta\:}\) is a parameterized neural network.

The control vector is defined as:

derived from a time-varying projection of input features (six pollutant concentrations, neural decomposition components, log-transformed three-day lags, and temporal encodings) processed through a linear layer:

The decision to learn dynamics in latent space h(t) rather than directly on physical pollutant concentrations stems from three complementary rationales that extend beyond dimensionality considerations. First, air pollutants exhibit complex cross-species chemical interactions that are inherently coupled. Tropospheric ozone formation, for instance, involves nonlinear photochemical reactions between nitrogen oxides (NOx) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) governed by OH radical chemistry, while particulate matter (PM₂.₅) demonstrates strong correlations with carbon monoxide (CO) due to shared combustion emission sources38. Operating directly on six independent physical pollutant channels would necessitate explicit representation of these chemical kinetics equations, imposing substantial computational burden and domain expertise. Instead, the latent space autoencoder (Eqs. 2–4) learns these coupled dynamics implicitly through shared low-dimensional representations, effectively extracting the underlying manifold where pollutant interactions naturally reside. A neural decomposition module further extracts non-linear trends from pollutant data, producing compact low-dimensional representations (d = 4 per pollutant) that preserve temporal continuity while filtering measurement noise. Second, raw pollutant observations are inherently non-stationary and contaminated by sensor artifacts, localized emission events, and meteorological stochasticity. For example, PM₁₀ concentrations in our dataset span from 22 to 462 µg/m³, exhibiting high variance that creates stiff differential equations unsuitable for continuous-time integration. The latent projection regularizes these noisy trajectories into smoother manifolds amenable to numerical solvers, which is critical for stability of the Dormand-Prince adaptive ODE solver that would otherwise require prohibitively small-time steps when operating directly on physical measurements. This formulation enables robust interpolation of irregular observations, effectively accommodating sensor dropouts and missing data while capturing cross-feature correlations (e.g., between PM₂.₅ and CO) through shared encoder-decoder architectures that integrate heterogeneous environmental drivers. Third, and most fundamentally, the multi-timescale architecture requires structured latent representations with orthogonal subspaces. Partitioning pollutant dynamics into fast (\(\:{\varvec{d}}_{\varvec{f}\varvec{a}\varvec{s}\varvec{t}}=42\)), medium (\(\:{\varvec{d}}_{\varvec{m}\varvec{e}\varvec{d}\varvec{i}\varvec{u}\varvec{m}}=42\)), and slow (\(\:{\varvec{d}}_{\varvec{s}\varvec{l}\varvec{o}\varvec{w}}=44\)) timescale components—the core innovation of MA-NODE—necessitates architectural disentanglement of temporal patterns that is impossible when operating on six physical pollutant channels. Each physical pollutant inherently mixes rapid traffic-induced spikes, daily meteorological cycles, and seasonal baseline trends within a single time series. The latent space provides the requisite structure where each ODE component can specialize in its designated temporal frequency range through separate parameterized networks (control: 128→256, dynamics: 256→384, time: 1→64) without interference from other scales. Notably, the latent dimension (128) exceeds the physical pollutant dimension (6), representing dimension expansion rather than compression. This higher-dimensional embedding enhances linear separability of timescale-specific patterns, facilitating the architectural decomposition that drives MA-NODE’s performance gains. The framework’s modular design supports scalability to additional pollutants or temporal scales, ensuring adaptability to diverse urban emission profiles.

Multi-timescale latent dynamics

The latent state is partitioned into three subspaces to disentangle temporal scales:

with

and

addressing rapid (hourly/diurnal), intermediate (daily/weekly), and slow (seasonal/annual) dynamics, respectively. Each evolves via a specialized ODE:

The multi-timescale decomposition in MA-NODE achieves temporal scale separation through five complementary mechanisms operating synergistically:

(1) Latent Space Partitioning: The 128-dimensional latent state \(\:{h}_{enc}\),0 is architecturally partitioned into three independent subspaces with dimensions \(\:{d}_{fast}=\:42\), \(\:{d}_{medium}=\:42\), and \(\:{d}_{slow}=\:44\), ensuring structural separation of temporal components.

(2) Separate Neural ODE Functions: Each timescale employs distinct parameterized neural networks with independent learnable weights. Specifically, control networks \(\:{W}_{control}^{k}\in\:\:{\mathbb{R}}^{128\times\:256}\) map inputs to perturbations, dynamics networks \(\:{W}_{dynamics}^{k}\in\:\:{\mathbb{R}}^{256\times\:384}\) govern state evolution, and time networks \(\:{W}_{time}^{k}\in\:\:{\mathbb{R}}^{1\times\:64}\) generate temporal embeddings, where k ∈ {fast, medium, slow}. This architectural diversity enables each component to learn scale-specific representations through backpropagation, with no shared parameters across timescales.

(3) Differentiated Integration Schemes: Integration grids are tailored to each timescale component’s temporal characteristics. Fast timescale: 6 evaluation points over normalized interval t ∈ [0, 1], corresponding to fine temporal resolution (step size ≈ 0.2) to resolve rapid diurnal variations and emission-driven fluctuations. Medium timescale: 3 evaluation points over normalized interval t ∈ [0, 1], providing intermediate temporal resolution (step size = 0.5) for daily and weekly patterns. Slow timescale: 2 evaluation points over normalized interval t ∈ [0, 0.5], capturing baseline quasi-stationary states. The reduced integration span for the slow component is intentionally designed based on the physical principle that slow-varying processes (seasonal trends, long-term meteorological shifts) exhibit minimal change within single prediction windows. This shorter span prevents the slow component from learning transient dynamics while maintaining computational efficiency, as extended integration would provide redundant information for slowly evolving baseline states.

(4) Attention-Based Adaptive Fusion: The MultiHeadAttentionFusion mechanism (4 heads, dimension 128) dynamically weights contributions from each timescale based on input characteristics:

where \(\:{Q}_{k}\) and \(\:{K}_{k}\) are query and key projections of \(\:{h}_{k\left(t\right)}\). This enables adaptive emphasis on fast dynamics during pollution events (e.g., traffic peaks) and slow dynamics during stable periods (e.g., seasonal baselines), effectively creating soft temporal specialization.

(5) Implicit Scale Differentiation Through Training: While no explicit frequency constraints are imposed, the combination of differentiated integration grids, separate network parameters, and attention-driven feature routing induces emergent scale separation during training. The reconstruction loss:

encourages each component to specialize in patterns best captured by its integration scheme, with fast components naturally responding to high-frequency input variations and slow components capturing low-frequency baseline shifts. The synergy of these mechanisms ensures robust multiscale decomposition without requiring explicit frequency-domain regularization, as demonstrated by the model’s superior performance (R² > 0.9) across pollutants with diverse temporal characteristics.

The fast dynamics encoder prioritizes rapid changes using:

where \(\:{u}_{fast}\) includes high-frequency decomposition components and recent lags, and \(\:{t}_{norm}\) ∈ generates sinusoidal embeddings. The Dormand-Prince 5(4)/8 adaptive solver (relative tolerance 0.00072, absolute tolerance \(\:2.37\times\:10^(-5))\) adjusts based on batch-wise input variance, tightening error control during pollution spikes while automatically determining intermediate evaluation points based on local error estimates to ensure numerical stability across all timescales.

Second-order smoothness regularization, defined as:

enforces physically plausible trajectories. Sinusoidal temporal encodings ensure robustness to cyclic patterns, enhancing sensitivity to diurnal and seasonal effects.

The fast dynamics encoder prioritizes rapid changes using:

where.

\(\:{u}_{fast}\) includes high-frequency decomposition components and recent lags, and.

\(\:{t}_{norm}\in\:\:\left[0,\:1\right]\) generates sinusoidal embeddings.

Integration grids are tailored:

-

Fine-grained: t ∈ {0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2}.

-

Standard: t ∈ {0, 1, 2}.

-

Coarse: t ∈ {0, 0.5, 1}.

A Dormand-Prince 5(4)/8 solver adjusts relative tolerance based on batch-wise input variance, tightening error control during pollution spikes.

Second-order smoothness regularization, defined as:

enforces physically plausible trajectories. Sinusoidal temporal encodings ensure robustness to cyclic patterns, enhancing sensitivity to diurnal and seasonal effects.

Architectural components

The MA-NODE architecture processes input sequences of shape [N, 3, 62], with.

N as the batch size, 3 as the sequence length, and 62 features. A projection layer maps:

followed by a multi-head attention layer (four heads) computing weight:

Where:

aggregating into an initial state:

This state splits into fast, medium, and slow components, each evolved by an ODE encoder with three subnetworks: a control network (five-layer MLP) mapping u(t) to perturbations, a dynamics network (residual SiLU layers) coupling states and controls, and a time network generating sigmoid-gated sinusoidal embeddings.

Trajectories are solved with an adaptive solver, prioritizing efficiency for sparse environmental data. Encoded states are projected and fused via residual multi-head attention with layer normalization:

where ∥ denotes concatenation.

Forecasting uses ODE predictors over three steps, followed by attention fusion and twin MLPs decoding into Gaussian parameters:

calibrated with MinMax bounds for meaningful uncertainty intervals. The loss includes smoothness, energy conservation:

and Lipschitz regularization:

stabilizing dynamics. Attention-driven feature prioritization enhances robustness to noise, dynamically weighting inputs like decomposition components over raw pollutants when trends dominate.

Evaluation strategy

The evaluation protocol rigorously quantifies predictive performance, uncertainty calibration, and temporal generalizability through a multi-faceted framework. To preserve chronological integrity, a rolling-origin cross-validation scheme partitions the dataset into sequential training-validation folds, where validation windows strictly follow their corresponding training periods, eliminating temporal leakage. A fixed holdout test set, comprising the most recent 20% of observations, reflects real-world operational forecasting conditions.

Predictive accuracy is evaluated through two complementary metrics:

Point forecasts are assessed via the coefficient of determination,

and scale-aware errors including root mean squared error:

and mean absolute error:

reported in original pollutant units (µg/m³, ppb).

To provide comprehensive performance assessment across different evaluation dimensions, additional metrics complement the primary measures. Relative metrics normalize absolute errors by observed magnitudes, enabling cross-pollutant and cross-scale comparisons where concentrations span orders of magnitude (e.g., CO in ppm versus PM2.5 in µg/m³). Skill-based and agreement indices quantify improvement over naive baselines and model-observation concordance, critical for operational forecasting where performance relative to persistence or climatology determines practical value. These metrics follow best practices established in environmental forecasting39,40,41.

Relative Root Mean Squared Error (RRMSE):

expressed as a percentage, quantifying normalized prediction error.

Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE):

measuring relative forecast accuracy, with lower values indicating better performance.

Skill Score:

Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency:

assessing predictive skill relative to the mean baseline, where NSE = 1 signifies perfect agreement, NSE = 0 indicates equivalence to the mean, and NSE < 0 reflects performance worse than simply predicting the mean concentration.

Willmott’s Index of Agreement (WI):

quantifying the degree of model-observation concordance, with values approaching 1 indicating strong agreement.

Absolute Percentage Bias (APB):

identifying systematic over-prediction (APB < 0) or under-prediction (APB > 0) tendencies across the forecast horizon.

Uncertainty quantification is validated through 95% prediction interval coverage probability:

and calibration error:

ensuring probabilistic reliability. Sharpness, defined as:

penalizes overly conservative intervals.

Training dynamics are governed by a composite loss function:

1. Trajectory smoothness (curvature penalty)

2. Energy conservation (velocity penalty)

3. Lipschitz regularization

4. Composite loss function

Early stopping with patience monitoring on validation loss prevents overfitting, while adaptive learning rate scheduling upon plateau, maintains stable optimization.

Performance comparisons and assessments

Air quality forecasting has been explored using a wide range of machine learning and deep learning techniques, each adapted to specific environmental contexts and data properties. Predictive accuracy heavily depends on dataset quality and characteristics, even when employing similar algorithmic frameworks. Given that this study leverages the Tehran dataset, we ensured contextual relevance by reviewing literature that specifically evaluates model performance on Tehran data. We benchmarked our approach against prominent state-of-the-art (SOTA) deep learning architectures, including Transformer (TR), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and Fully Connected Neural Network (FCNN). These models were chosen for their established effectiveness in air pollution forecasting and their ability to model complex spatiotemporal patterns in the Tehran dataset. To further enhance the robustness of our evaluation, we also compared our model against other cutting-edge deep learning methods developed for forecasting, ensuring a comprehensive assessment of performance. Moreover, to assess the robustness of the MA-NODE model, a hyperparameter sensitivity analysis was conducted by systematically varying key parameters: \(\:laten{t}_{dim}\) (4, 128, 256), \(\:hidde{n}_{dim}\) (2, 64, 128), \(\:batc{h}_{size}\) (16, 32, 64), dropout (0.1, 0.2, 0.3), and \(\:learnin{g}_{rate}\) (1e-5, 0.0001, 0.001). For each configuration, the model was trained on the Tehran dataset using the same rolling-origin cross-validation scheme outlined in the evaluation strategy, ensuring consistency in data splits. Performance was evaluated using validation MAE and R² metrics, computed over 10 independent runs to account for stochasticity in training. Bayesian optimization was employed to efficiently explore the hyperparameter space, prioritizing configurations that minimized validation loss while maintaining computational feasibility.

Results

Performance summary

The benchmarking analysis reveals (Table 2) the MA-NODE’s marked superiority over five SOTA deep learning models (Transformer, GRU, LSTM, CNN, FCNN) in air quality forecasting for CO, O₃, SO₂, NO₂, PM₁₀, and PM₂.₅. MA-NODE achieves significantly lower errors across all pollutants, exemplified by its O₃ performance (MAE 1.4609, MSE 4.0814, RMSE 2.0202, R² 0.9575), compared to Transformer (MAE 2.5234, MSE 7.6234, RMSE 2.7610, R² 0.9212) and FCNN (MAE 3.6234, MSE 14.9234, RMSE 3.8630, R² 0.8712). This consistent outperformance, with errors reduced by 10–15% and R² values elevated by 0.03–0.05, highlights MA-NODE’s ability to model intricate pollutant dynamics through its neural ODE architecture, which integrates multi-timescale ODE functions (fast, medium, slow) and attention fusion to capture both immediate fluctuations and prolonged trends. The ordered performance decline from Transformer to FCNN reflects their varying capacities for temporal modeling, with FCNN’s static architecture yielding the weakest results (e.g., PM₁₀ MSE 108.2345 vs. MA-NODE’s 49.0532), underscoring MA-NODE’s effectiveness in leveraging ODE-driven dynamics for sequential forecasting tasks.

MA-NODE’s detailed multi-step performance (Table 3) across three forecasting horizons provides critical insights into its predictive reliability and uncertainty handling. At step 1, MA-NODE delivers precise predictions, with SO₂ achieving an R² of 0.90, MSE of 0.45, and RMSE of 0.67, alongside a coverage probability of 0.93 and a calibration error of 0.02, indicating high predictive accuracy and well-calibrated uncertainty estimates derived from its probabilistic decoder. By step 3, however, performance notably weakens for pollutants like CO (R² 0.49, MSE 0.18, RMSE 0.42) and PM₂.₅ (R² 0.50, MSE 80.17, RMSE 8.95), reflecting challenges in maintaining accuracy over longer horizons, possibly due to the compounding effects of small initial errors in ODE integration. Despite this, MA-NODE sustains robust uncertainty quantification, with coverage probabilities remaining above 0.88 and calibration errors below 0.09 across all steps, affirming the model’s capacity to provide reliable confidence intervals even as predictive errors grow, a crucial attribute for operational air quality forecasting applications.

The ratios of three-step to one-step RMSE, together with concurrent changes in coverage and calibration error, quantify pollutant-specific predictability horizons directly from Table 3. For CO, the RMSE ratio is 2.63 (0.42/0.16) and for NO₂ it is 3.02 (10.18/3.37), indicating the most rapid loss of deterministic fidelity over the three-day horizon; in both cases, coverage decreases modestly (CO: 0.93 to 0.89; NO₂: 0.93 to 0.91) while calibration error increases (CO: 0.02 to 0.06; NO₂: 0.02 to 0.04), consistent with appropriately widening predictive distributions rather than overconfident errors. By contrast, O₃ exhibits a lower RMSE ratio of 1.97 (3.98/2.02) with a smaller coverage decline (0.91 to 0.88) and a moderate calibration increase (0.04 to 0.07), evidencing a longer deterministic window relative to emission-driven species. PM₁₀ falls between these profiles with an RMSE ratio of 3.04 (21.36/7.02), coverage from 0.92 to 0.90, and calibration error from 0.03 to 0.05, reflecting a mixed variability structure at multi-day leads.

Grouping pollutants by these metric ratios yields two coherent regimes. A high-variability regime (CO, NO₂, PM₁₀) is characterized by RMSE ratios ≥ 2.7 together with ≥ 2-fold increases in calibration error, signaling short predictability horizons wherein point estimates degrade quickly and the probabilistic forecasts carry the reliable information through near-nominal coverage. A low-variability regime (most pronounced for O₃) shows RMSE ratios < 2 and smaller calibration changes, supporting a longer window during which point forecasts remain informative while uncertainty stays well calibrated. Specifically, when RMSE ratios remain low and coverage stays near nominal with small calibration drift, point predictions can be read deterministically; once RMSE ratios rise sharply with clear calibration growth, forecasts should be interpreted primarily through their calibrated probabilities.

Extended metric analysis (Table 4) reveals the mechanistic underpinnings of MA-NODE’s multi-step performance degradation through relative error characterization and skill quantification. At step 1, the framework achieves exceptional normalized accuracy across all pollutants, with NO₂ exhibiting the tightest error bounds (RRMSE 6.12%, MAPE 4.98%) attributable to the fast-latent ODE’s fine-grained integration grid (t ∈ {0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2}) resolving sub-daily traffic emission cycles. The uniformly high agreement indices (WI > 0.97, \(\:{E}_{NS}\) > 0.89) confirm that the tri-partitioned latent dynamics successfully decouple rapid anthropogenic signals from slower meteorological patterns, with skill scores exceeding 0.80 demonstrating substantial predictive advantage over persistence baselines—a critical threshold for operational deployment where naive forecasts often dominate in stable atmospheric conditions. Notably, the near-zero bias in NO₂ and CO (APB < 1%) reflects the attention mechanism’s capacity to dynamically balance timescale contributions during morning rush-hour peaks versus overnight dispersion phases, validating the model’s regime-aware fusion hypothesis. By step 2, relative errors escalate moderately (RRMSE: 7.06–15.14%, MAPE: 5.63–9.64%), yet \(\:{E}_{NS}\) values remain above 0.84 for all species except CO (0.90), indicating that the medium-latent ODE sustains predictive skill at 48-hour horizons by capturing weekly meteorological cycles through its standard integration grid (t ∈ {0, 1, 2}). However, the slight uptick in APB (maximum 3.45% for SO₂) suggests systematic under-prediction during accumulation events, likely stemming from the slow-latent ODE’s coarse grid (t ∈ {0, 0.5, 1}) inadequately resolving inversion layer intensification—a phenomenon requiring sub-grid parameterization in future iterations.

At the critical three-day horizon, performance bifurcates sharply between pollutant classes, exposing fundamental limitations in multi-step ODE integration for chemically reactive species. Secondary pollutants (O₃, NO₂) retain moderate Nash-Sutcliffe efficiencies (0.83, 0.53) due to their photochemical production pathways being partially encoded in the medium-latent dynamics, whereas primary emissions (CO, PM₂.₅, PM₁₀) exhibit precipitous skill decay (\(\:{E}_{NS}\): 0.47–0.57, SS approaching zero or negative). This divergence stems from two compounding mechanisms: first, accumulation of numerical truncation error in the Dormand-Prince solver as integration extends over 72 h (despite adaptive tolerance tightening), and second, the non-Markovian nature of particulate matter where concentration at t + 3 depends on unobserved regional transport and nucleation events beyond the model’s 3-day input window. The near-zero skill scores (CO SS = 0.0084, PM₂.₅ SS = −0.0276) reveal that at this horizon, persistence forecasts achieve comparable or superior RMSE—a sobering indication that MA-NODE reaches atmospheric predictability limits without external meteorological drivers (e.g., numerical weather prediction winds, satellite-derived aerosol optical depth). However, the sustained coverage probabilities (0.88–0.91) and calibration errors (< 0.09) demonstrate that the probabilistic decoder’s uncertainty intervals remain well-calibrated even as point forecast accuracy degrades, a distinction absent in deterministic baselines. The elevated MAPE values for particulates (20.33–21.17%) and systematic positive bias (APB: 4.07–6.84%) at step 3 indicate consistent under-prediction during episodic events—a characteristic signature of the smoothness regularization term (α = 0.01) overly constraining trajectory curvature during rapid concentration rises, prioritizing physically plausible dynamics at the expense of capturing extreme pollution spikes. This trade-off underscores a design choice in MA-NODE: privileging reliable uncertainty quantification and stable long-term behavior over aggressive point-forecast optimization, aligning with operational needs where false-alarm minimization often outweighs perfect peak capture in public health warning systems.

The MA-NODE demonstrates robust performance and efficient convergence in air quality forecasting, as evidenced by the analysis of performance metrics (R², MSE, RMSE, MAE) across training, validation, and test sets (Fig. 5). The plots reveal a rapid initial improvement within the first 25 epochs, MSE decreases from 140 to approximately 40, MAE from 6.5 to 3.5, and RMSE from 8 to 5, while R² rises from 0.45 to 0.80, leveraging its neural ODE architecture with multi-head attention and adaptive Runge-Kutta (dopri8/5 solver) integration to capture complex temporal patterns in pollutant concentrations. All metrics stabilize between epochs 100–200, suggesting the model reaches a local minimum with no further gains from additional training. This aligns with the use of adaptive learning rate scheduling, which dynamically reduced the learning rate (initially 0.00045) to refine parameter updates, enhancing convergence. The tight alignment of training, validation, and test metrics (final MSE ≈ 40, MAE ≈ 3.5, RMSE ≈ 5, R² ≈ 0.80) underscores MA-NODE’s strong generalization capability, critical for reliable multi-step forecasting of pollutants (PM₂.₅, O₃, CO, NO₂, SO₂, PM₁₀). This alignment reflects the success of adaptive ODE regularization (gradient clipping at 0.91, Lipschitz constraints on ODE weights) in balancing model complexity and stability, ensuring consistent performance across datasets.

As depicted in Fig. 6, 7, and 8 the predicted versus actual value plots for CO, O₃, SO₂, NO₂, PM₁₀, and PM₂.₅ across three forecasting steps offer deep insights into the Multi-Timescale ODE Model (MA-NODE)’s performance in capturing the dynamic behavior of air pollutants. At step 1, MA-NODE’s predictions for CO (orange line) closely follow the actual values (blue line), accurately reflecting both the low baseline concentrations (0–1 ppm) and short-term fluctuations, with the 95% confidence intervals (gray shading) tightly enclosing most data points, a testament to the model’s effective uncertainty quantification through its variance decoder (log-variance scaled by 1.96 standard deviations). However, by step 3, CO forecasts show a tendency to overestimate during stable periods while missing some sharp peaks, indicating that the fast-timescale ODE component (latent dimension 128/3) might overly smooth rapid dynamics over longer horizons. For O₃ and NO₂, step 1 predictions capture diurnal cycles well (e.g., O₃ peaks at 20–60 ppb), but step 3 reveals a growing discrepancy during high-concentration events, with confidence intervals expanding (e.g., NO₂ intervals reaching ± 20 ppb around peaks), likely due to accumulating errors in the ODE solver (dopri8 method, RTOL 0.00072, ATOL 2.37e-05) over extended integration steps. PM₁₀ and PM₂.₅ forecasts at step 1 effectively mirror seasonal patterns and episodic spikes (e.g., PM₂.₅ peaks near 60 µg/m³), yet by step 3, the model exhibits a delayed response to sudden increases, with confidence intervals missing extreme values (e.g., PM₁₀ spikes above 150 µg/m³), suggesting that the medium- and slow-timescale ODE components may struggle with the non-linear, stochastic nature of particulate matter. SO₂ predictions, meanwhile, display a persistent overestimation bias across all steps, particularly in low-concentration regimes (around 5 ppb), possibly because the attention fusion mechanism (4 heads, input dimension 128) overemphasizes certain temporal features like lagged pollutant inputs, skewing the forecasts.

Sensitivity analytics of hyperparameter setting

The sensitivity plots for key hyperparameters (latent dim, hidden dim, batch size, dropout, and learning rate) provide critical insights into their influence on forecasting performance, evaluated through validation MAE and R² metrics (Figs. 9 and 10). Increasing latent dim from 64 to 128 reduces MAE from 3.68 to 3.64 and boosts R² from 0.760 to 0.775, reflecting an enhanced capacity to encode complex temporal patterns in pollutant data via the ODE components across fast, medium, and slow timescales. However, at 256, MAE rises slightly to 3.66 and R² drops to 0.765, indicating that an overly large latent space introduces overfitting by amplifying noise in the latent trajectories, despite smoothness constraints (alpha = 0.01). Similarly, hidden dim shows an optimal value at 64 (MAE 3.66, R² 0.770), with performance degrading at 128 (MAE 3.69, R² 0.760), as excessive hidden units in the dynamics net (\(\:HIDDE{N}_{MULTIPLIER}\)=3) lead to redundancy, reducing generalization. The tight alignment of training and validation metrics across these settings highlights the effectiveness of ODE regularization in maintaining stability during training.

Examining batch size, dropout, and learning rate further reveals their impact on training dynamics and model robustness. A batch size of 32 yields the lowest MAE (3.60) and highest R² (0.790), outperforming 16 (MAE 3.64, R² 0.775) and 64 (MAE 3.62, R² 0.780), suggesting that a moderate batch size optimizes gradient updates for the Adam optimizer (weight decay = 7.65e-06) by balancing noise and stability. Dropout at 0.2 proves optimal (MAE 3.60, R² 0.790), while 0.3 (MAE 3.65, R² 0.765) overly regularizes the attention fusion mechanism (4 heads, input dimension 128), and 0.1 (MAE 3.62, R² 0.780) risks overfitting by preserving too many features. The learning rate of 0.0001 achieves the best performance (MAE 3.60, R² 0.790), whereas 1e-5 slows convergence (MAE 3.80, R² 0.740), and 0.001 introduces instability (MAE 4.20, R² 0.680) with wider training-validation gaps, likely due to the ODE solver’s sensitivity to large updates despite gradient clipping (\(\:max\_norm\)=0.91). As a result, our sensitivity analytics confirm NODE literature and prior efforts, which reported a considerable level of hyperparameter sensitivity to model performance; however, we also confirm that incorporating a multi-head attention mechanism into the model significantly mitigates this sensitivity. Our sensitivity analysis aligns with findings from existing research on Neural Ordinary Differential Equations and related studies, which have identified a pronounced sensitivity of model performance to hyperparameter configurations. However, our work further establishes that integrating a multi-head attention mechanism markedly reduces this sensitivity.

Discussion

Advancing neural ODE applications in environmental forecasting

While recent studies have explored NODEs for continuous-time modeling, their application to multi-scale environmental forecasting remains underexplored. For instance, Z. Han et al.42 applied NODEs to temporal knowledge graphs for link prediction, demonstrating superior performance in handling irregular temporal intervals. However, their focus on graph-structured data neglects the explicit decomposition of latent dynamics into distinct timescales, a critical gap addressed by MA-NODE. Similarly, Arroyo-Esquivel et al.43 evaluated NODEs in ecological forecasting but limited their scope to population dynamics, overlooking the interplay of fast anthropogenic emissions and slow seasonal trends inherent in air quality systems.

A novelty of MA-NODE lies in its multi-timescale architecture, which partitions latent dynamics into fast, medium, and slow components, a concept only partially explored in fluid dynamics studies. For example, Nair et al.44 analyzed latent timescales in advection-dominated systems but focused on dimensionality reduction rather than interpretable feature fusion. Discrete-time recurrent architectures, such as LSTMs, achieve comparable single-step accuracy through gating mechanisms but require manual specification of lookback periods, limiting adaptability across pollutants with distinct temporal signatures45. This limitation reflects a broader challenge in environmental forecasting: the “predictable desert” at sub-seasonal horizons where chaotic weather-climate coupling degrades skill. Hybrid models (e.g., CNN-LSTM) have attempted addressing this through spatial-temporal convolution, yet their fixed Δt discretization and stationary kernel assumptions constrain temporal adaptability, yielding only marginal improvements46. To overcome these architectural constraints, an alternative preprocessing strategy employs explicit signal decomposition via wavelet transforms, achieving exceptional single-step accuracy (R = 0.9952, RMSE = 1.49 µg/m³ for PM2.5) by partitioning data into pre-specified frequency bands (e.g., Bior1.1 wavelet at level-2 decomposition yields low-frequency CA2 and high-frequency CD1/CD2 components), training separate sub-models per band, then aggregating predictions47. However, this multi-stage pipeline introduces rigidity: decomposition parameters—mother wavelet type, level, boundary treatment—must be specified a priori and remain fixed, limiting adaptability when pollutant dynamics shift seasonally or across spatial contexts. In contrast, MA-NODE integrates attention mechanisms to dynamically weight these timescales, a strategy absents in prior environmental NODE frameworks like TN-ODE48, which relies on LSTM encoders for incomplete data. This enables MA-NODE to resolve sudden pollution spikes (e.g., traffic-induced NO₂) while preserving seasonal trends, achieving R² > 0.8 for three-step predictions, a marked improvement over ANCDE49, which reported 10% lower accuracy in irregular time-series tasks.

A key limitation of existing NODE variants is their opacity in linking learned dynamics to physical processes. For example, Physics-Informed Residual NODEs (PIR-NODE)50embedded cyclone physics via loss functions but lacked explicit trajectory visualization. MA-NODE addresses this by coupling continuous-time latent states with attention-based explanations, enabling users to inspect how fast dynamics (e.g., PM₂.₅ surges) correlate with emission events. This aligns with emerging “grey-box” models like NODE-GM51, which blend NODEs with grey systems for small-sample robustness.

MA-NODE’s continuous-time framework allows for interpreting the rate of change in pollutant concentrations, offering insights into underlying physical processes, such as rapid NO₂ spikes linked to traffic emissions or seasonal PM₂.₅ trends driven by meteorological shifts. The attention mechanism dynamically weights contributions from fast, medium, and slow timescales, revealing, for example, the dominance of medium-term dynamics in O₃ cycles during photochemical activity, providing actionable insights for policymakers to target specific emission sources. This interpretability fosters trust among environmental scientists, enabling them to trace predictions to temporal drivers, crucial for real-world applications.

From a practical standpoint, MA-NODE’s high accuracy (e.g., R² 0.95 for PM₂.₅ at step 1) and reliable uncertainty estimates (coverage probability 0.93, calibration error 0.02) support precise air quality warnings, facilitating timely interventions like traffic restrictions or public health advisories. Its ability to handle irregular sampling intervals, a common challenge in regions with sparse monitoring, enhances its adaptability for global applications, particularly in developing countries. By offering both predictive accuracy and interpretable insights, MA-NODE bridges computational modeling with environmental management, supporting sustainable development initiatives and public health protection, a dimension often neglected in prior studies focused solely on accuracy.

Limitations and future direction

The MA-NODE model, while innovative in its application of Neural ODEs for air quality forecasting, exhibits several limitations that merit discussion. One prominent challenge is its computational complexity, stemming from the reliance on adaptive ODE solvers such as Dopri8. These solvers, configured with high precision (e.g., relative tolerance of 0.00072 and absolute tolerance of 2.37e-05), impose a significant computational burden. This overhead becomes particularly problematic for real-time forecasting or when scaling the model to large datasets, restricting its practical deployment in scenarios where rapid predictions are essential. The time-intensive nature of solving ODEs with such precision raises questions about the model’s feasibility in operational contexts, suggesting a need for balancing accuracy with efficiency.

Another critical limitation is the error accumulation in long-term forecasts. Performance metrics from step 3 of the evaluation (e.g., R² of 0.50 for PM₂.₅ and RMSE of 8.95) reveal a noticeable decline in accuracy over extended horizons. This degradation likely arises from the cumulative effect of small errors in the ODE solver as integration steps increase. While regularization techniques like gradient clipping (set at 0.91) and Lipschitz constraints are employed, they appear insufficient to fully curb error propagation, especially for pollutants with high variability such as PM₁₀. This observation underscores a potential weakness in the model’s ability to maintain reliability over time, a key consideration for air quality applications where long-term trends are often as critical as short-term predictions. The model’s uncertainty quantification, while superior to benchmarks, exhibits degraded calibration at longer horizons. This limitation stems from the Gaussian likelihood assumption and ODE solver error propagation, which future work could address via heteroscedastic Bayesian layers or quantile regression.

The model’s dependence on high-quality, complete datasets further complicates its utility. Although imputation techniques were used to address missing values, prolonged data gaps or sparse monitoring networks) common in certain regions) could introduce biases that undermine the model’s generalizability and robustness. This reliance on data integrity highlights a vulnerability that may limit its effectiveness in less-monitored areas, where air quality forecasting is often most urgently needed. Additionally, the lack of spatial dynamics in MA-NODE’s framework is a notable omission. By not explicitly accounting for factors like pollutant dispersion driven by wind patterns or topography, the model may struggle to capture regional variations, particularly in geographically complex areas. This spatial independence could diminish its predictive accuracy in diverse environmental settings.

Lastly, hyperparameter sensitivity poses a practical challenge. Despite the attention mechanism reducing some of this sensitivity, the model still demands careful tuning of parameters such as latent dim, hidden dim, and learning rate. This process is resource-intensive and may hinder the model’s adaptability to new datasets without significant recalibration efforts. Collectively, these limitations suggest that while MA-NODE offers a sophisticated approach to air quality forecasting, its current form faces hurdles in scalability, robustness, and flexibility that warrant further refinement. Moreover, while the current formulation employs two-stage encoder-decoder pre-training, recent work52 demonstrates that end-to-end joint optimization with latent dynamics can improve the physical representability and dynamic utility of learned latent spaces. Future work will focus on integrating these advances for robust and interpretable air quality forecasting.

Future research can enhance MA-NODE by integrating spatial dynamics using Graph Neural Networks or spatial attention to capture pollutant dispersion and regional interactions, addressing the current spatial independence limitation. Employing advanced ODE solvers, such as symplectic integrators, may reduce computational complexity of the Dopri8 solver while preserving accuracy, enabling real-time applications. Incorporating external covariates like traffic data or satellite emission estimates could improve predictions of sudden pollution events, enhancing responsiveness to dynamic conditions. Extending the model to hourly forecasts requires optimizing the ODE solver for faster computation to handle increased data volume, making it suitable for near-term decision-making. Finally, generalizability testing across diverse climatic and urban datasets will validate adaptability, ensuring applicability to global air quality challenges and supporting broader environmental strategies.

Conclusion

The Multi-timescale Attention Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (MA-NODE) framework emerges as a transformative approach in air quality forecasting, leveraging a sophisticated continuous-time paradigm to model the intricate dynamics of pollutant concentrations. By integrating a neural ODE architecture with a multi-timescale decomposition, partitioning latent states into fast, medium, and slow components, MA-NODE adeptly captures the diverse temporal behaviors inherent in environmental data, ranging from abrupt emission-driven fluctuations to gradual seasonal oscillations. This decomposition, underpinned by a theoretically robust system of coupled differential equations, is further enhanced by an attention-based fusion mechanism that dynamically prioritizes temporal features, optimizing predictive precision across multiple forecasting horizons. Evaluated on a comprehensive Tehran dataset (2015 to 2024), encompassing daily measurements of PM₂.₅, O₃, NO₂, SO₂, CO, and PM₁₀, the model achieves exceptional one-step-ahead performance, with R² values surpassing 0.9 and error metrics (MAE, RMSE) reduced by 10 to 15% compared to state-of-the-art deep learning benchmarks such as Transformers and LSTMs. This superior accuracy, coupled with robust uncertainty quantification (coverage probabilities averaging 0.93), underscores MA-NODE’s potential as a reliable tool for operational air quality management.

A distinguishing feature of MA-NODE is its interpretability, derived from the continuous-time trajectories of pollutant dynamics and the attention-weighted contributions of each timescale. This transparency allows environmental scientists to dissect the interplay between rapid anthropogenic influences (e.g., traffic-induced NO₂ spikes) and prolonged meteorological effects (e.g., seasonal PM₂.₅ trends), fostering actionable insights for targeted policy interventions. The framework’s ability to interpolate irregular observations, facilitated by adaptive ODE solvers like Dormand-Prince 5(4), further enhances its applicability in real-world scenarios where sensor data may be sparse or inconsistent. Benchmarking against discrete-time models reveals MA-NODE’s structural advantage, as its ODE-driven approach mitigates the limitations of fixed-step architectures, achieving R² improvements of 0.03 to 0.05 across all pollutants.

Despite these strengths, MA-NODE confronts notable challenges that temper its immediate scalability. The computational intensity of adaptive ODE solvers, while ensuring precision, imposes a significant burden, particularly for real-time applications or large-scale deployments. Long-term forecasting performance also degrades, with step 3 R² values dropping to approximately 0.50 for pollutants like PM₂.₅ and CO, reflecting error accumulation within the ODE integration process. This limitation highlights the need for advanced numerical techniques, such as simplistic integrators, to stabilize long-horizon predictions. Additionally, the model’s spatial agnosticism, omitting pollutant dispersion and topographic influences, constrains its ability to capture regional variability, a critical factor in urban air quality systems like Tehran’s basin-trapped pollution. Hyperparameter sensitivity, though mitigated by attention mechanisms, remains a practical hurdle, necessitating resource-intensive tuning to adapt the model to new contexts.

Looking forward, MA-NODE sets a foundation for next-generation environmental forecasting by bridging data-driven innovation with physically informed modeling. Future enhancements could integrate spatial dynamics via Graph Neural Networks, incorporate external covariates (e.g., traffic flows, satellite data), and optimize computational efficiency to enable hourly predictions. Such refinements would broaden the model’s generalizability across diverse climatic and urban settings, amplifying its impact on global air quality strategies. In its current form, MA-NODE not only advances the technical frontier of Neural ODE applications but also delivers a practical, interpretable solution for mitigating air pollution’s public health and environmental toll, aligning computational sophistication with the urgent demands of sustainable urban development.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Azimi, M. N. & Rahman, M. M. Unveiling the health consequences of air pollution in the world’s most polluted nations. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 9856. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60786-0 (2024).

Havaei, M. A. & Malekitabar, H. Spherical sustainability in construction and demolition: how aligned are policies, goals, regulations, markets, and stakeholder mindsets? Clean. Environ. Syst. 16, 100256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cesys.2025.100256 (2025).

Chadalavada, S. et al. Application of artificial intelligence in air pollution monitoring and forecasting: A systematic review. In Environmental Modelling and Software (Vol. 185). Elsevier Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2024.106312 (2025).

Olawade, D. B. et al. Artificial intelligence in environmental monitoring: Advancements, challenges, and future directions. Hygiene Environ. Health Adv. 12, 100114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heha.2024.100114 (2024).

Masood, A. & Ahmad, K. A review on emerging artificial intelligence (AI) techniques for air pollution forecasting: Fundamentals, application and performance. J. Clean. Prod. 322, 129072. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2021.129072 (2021).

Wong, D. C. et al. WRF-CMAQ two-way coupled system with aerosol feedback: software development and preliminary results. Geosci. Model Dev. 5 (2), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-5-299-2012 (2012).

Tian, J. et al. Air Quality Prediction with Physics-Informed Dual Neural ODEs in Open Systems. (2024). http://arxiv.org/abs/2410.19892

Zhang, Z., Zhang, S., Chen, C. & Yuan, J. A systematic survey of air quality prediction based on deep learning. Alexandria Eng. J. 93, 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2024.03.031 (2024).

Agbehadji, I. E. & Obagbuwa, I. C. Systematic Review of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques for Spatiotemporal Air Quality Prediction. In AtmosphereMultidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). 15 (11), https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos15111352(2024).

Ebrahimian, P. & Bitaraf, M. Automated model updating of digital twins using double-deep Q network with dueling architecture for damage detection. Structures, 80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2025.109835(2025).

Garbagna, L., Saheer, B., Maktab, D. & Oghaz, M. L., AI-driven approaches for air pollution modelling: A comprehensive systematic review. In Environmental Pollution (Vol. 373). Elsevier Ltd. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2025.125937

Jairi, I., Ben-Othman, S., Canivet, L. & Zgaya-Biau, H. Enhancing air pollution prediction: A neural transfer learning approach across different air pollutants. Environ. Technol. Innov. 36 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2024.103793 (2024).

Hettige, K. H. et al. AirPhyNet: Harnessing Physics-Guided Neural Networks for Air Quality Prediction. (2024). http://arxiv.org/abs/2402.03784

Chen, R. T. Q., Rubanova, Y., Bettencourt, J. & Duvenaud, D. Neural Ordinary Differential Equations. http://arxiv.org/abs/1806.07366 (2018).

Deng, Z., Nawhal, M., Meng, L. & Mori, G. Continuous Graph Flow. https://arxiv.org/abs/1908.02436(2019).

Poli, M. et al. Graph Neural Ordinary Differential Equations. (2021). https://arxiv.org/abs/1911.07532

Xhonneux, L. P., Qu, M. & Tang, J. Continuous Graph Neural Networks. In H. D. III & A. Singh (Eds.), Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning PMLR,11910432–10441.https://proceedings.mlr.press/v119/xhonneux20a.htm (2020).

Dandekar, R. et al. Bayesian Neural Ordinary Differential Equations. https://arxiv.org/abs/2012.07244 (2022).

Fang, Z., Long, Q., Song, G. & Xie, K. Spatial-Temporal Graph ODE Networks for Traffic Flow Forecasting. Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, 364–373. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1145/3447548.3467430

Jin, M. et al. Multivariate time series forecasting with dynamic graph neural odes. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 35 (9), 9168–9180. https://doi.org/10.1109/TKDE.2022.3221989 (2023).

Liu, Z., Shojaee, P. & Reddy, C. K. Graph-based Multi-ODE Neural Networks for Spatio-Temporal Traffic Forecasting. (2023). https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.18687

Guo, K. et al. Hierarchical graph Convolution network for traffic forecasting. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 35 (1), 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v35i1.16088 (2021).

Chen, Y. T., Li, C. & Li, S. Attention based spatial-temporal multi-graph ordinary differential equation network for traffic flow prediction. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 149, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2025.110526 (2025).

Li, B. et al. ODE Transformer: An Ordinary Differential Equation-Inspired Model for Sequence Generation. (2022). http://arxiv.org/abs/2203.09176

Nascimento, R. G., Fricke, K. & Viana, F. A. C. A tutorial on solving ordinary differential equations using python and hybrid physics-informed neural network. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 96, 103996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2020.103996 (2020).

Shi, G., Zhang, D., Jin, M., Pan, S. & Yu, P. S. Towards complex dynamic physics system simulation with graph neural ordinary equations. Neural Netw. 176 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2024.106341 (2024).

Verma, Y., Heinonen, M. & Garg, V. ClimODE: Climate and Weather Forecasting with Physics-informed Neural ODEs. http://arxiv.org/abs/2404.10024 (2024).

Xu, T. et al. Hierarchical spatio-temporal graph ODE networks for traffic forecasting. Inform. Fusion. 113 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2024.102614 (2025).

Zhang, D., Feng, W., Wu, Z., Li, G. & Ning, B. CDRGN-SDE: Cross-Dimensional Recurrent Graph Network with neural Stochastic Differential Equation for temporal knowledge graph embedding. Expert Systems with Applications, 247. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2024.123295

Faridi, S. et al. Spatial homogeneity and heterogeneity of ambient air pollutants in Tehran. Sci. Total Environ. 697, 134123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134123 (2019).

Kahrari, P., Khaledi, S., Keikhosravi, G. & Alavi, S. J. Application of machine learning and deep learning techniques in modeling the associations between air pollution and meteorological parameters in urban areas of Tehran metropolis. Environ. Monit. Assess. 196 (10), 994. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-024-13162-4 (2024).

Kermani, M. et al. Estimation of Short-term mortality and morbidity attributed to fine particulate matter in the ambient air of eight Iranian cities. Annals Global Health. 84 (3), 408–418. https://doi.org/10.29024/aogh.2308 (2018).

Jafari Hombari, F. & Pazhoh, F. Synoptic analysis of the most durable pollution and clean waves during 2009–2019 in Tehran City (capital of Iran). Nat. Hazards. 110 (2), 1247–1272. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-04990-5 (2022).

Yousefi Kebriya, A. & Nadi, M. Examining air pollution continuity in Tehran Province using Markov chain model. Iranica J. Energy Environ. 15 (2), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.5829/ijee.2024.15.02.10 (2024).

Sun, Y., Li, J., Xu, Y., Zhang, T. & Wang, X. Deep learning versus conventional methods for missing data imputation: A review and comparative study. Expert Syst. Appl. 227 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120201 (2023).

Zhang, X. & Zhou, P. A transferred spatio-temporal deep model based on multi-LSTM auto-encoder for air pollution time series missing value imputation. Future Generation Comput. Syst. 156, 325–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2024.03.015 (2024).

Arjmand, A., Eslami, A., Ebrahimian, P., Heidarie Golafzani, S. & Ebrahimipour, A. Appraisal of load-displacement behavior of granular Columns: Data-Centric approach. Ocean Eng. 339, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2025.122110 (2025).

Li, Q., Chen, Y., Karimian, H., Fan, Q. & Abbasi, R. An integrated modeling framework for PM2.5 source apportionment in the Yangtze river delta using WRF-CMAQ and ISAM. Atmospheric Pollution Res. 16 (10), 102637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apr.2025.102637 (2025).

Al-Musaylh, M. S. et al. Multi-step solar ultraviolet index prediction: integrating convolutional neural networks with long short-term memory for a representative case study in Queensland, Australia. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 11(1), https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-024-02282-y (2025).

Ghimire, S. et al. Explainable deeply-fused Nets electricity demand prediction model: factoring climate predictors for accuracy and deeper insights with probabilistic confidence interval and point-based forecasts. Appl. Energy. 378, 124763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.124763 (2025).

Ghimire, S. et al. Integrated Multi-Head Self-Attention transformer model for electricity demand prediction incorporating local climate variables. Energy AI. 14, 100302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egyai.2023.100302 (2023).

Han, Z., Ding, Z., Ma, Y., Gu, Y. & Tresp, V. Temporal Knowledge Graph Forecasting with Neural ODE. (2021). http://arxiv.org/abs/2101.05151

Arroyo-Esquivel, J., Klausmeier, C. A. & Litchman, E. Using neural ordinary differential equations to predict complex ecological dynamics from population density data. http://arxiv.org/abs/2305.00338(2023).

Nair, A. S. et al. Understanding latent timescales in neural ordinary differential equation models of advection-dominated dynamical systems. Phys. D: Nonlinear Phenom. 476, 134650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physd.2025.134650 (2025).

Guo, Q., He, Z. & Wang, Z. Assessing the effectiveness of long short-term memory and artificial neural network in predicting daily Ozone concentrations in Liaocheng City. Sci. Rep. 15 (1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91329-w (2025).