Abstract

We performed a thorough first-principles study of Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe, including structural, electronic, optical, and transport features. Structurally, both compounds have a trigonal R3m structure with different polyhedral designs. Mg2TeSe shows a larger equilibrium volume, and thermodynamic parameter (Ecoh ≈ − 3.65 eV/atom for Mg2TeS and − 3.79 eV/atom for Mg2TeSe; ΔHf ≈ − 2.17 and − 2.53 eV/atom) indicate both are energetically valuable, with Mg2TeSe relatively more stable. Electronically, these materials are found as direct band gap semiconductors. The WC-GGA underestimated band gaps with values of (≈ 1.49 eV and 1.83 eV), which were then corrected by SOC + TB-mBJ with values of (≈ 2.64 eV and 2.71 eV) for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe, respectively. Projected density of states indicates valence bands are dominated by Te states and conduction bands by Mg states, and replacing S with Se narrows the band gap while shifting density of states toward the Fermi level. Optically, notable interband responses occur with ε1(ω) and refractive index maxima between 5.0 and 5.5 eV, ε2(ω) peaks ≈ 5.5–5.8 eV, static refractive index ≈ 2.1, absorption peaking at ≈ 4.0 eV (Mg2TeS) and ≈ 3.5 eV (Mg2TeSe), low static reflectivity (~ 0.12), and plasmonic loss peaks near 17.0 and 16.0 eV. The transport results demonstrate modest Seebeck at low T, electrical conductivity σ/τ ≈ 2.27 × 1019 and 2.24 × 1019 (Ω·m·s)−1 at 300 K, lower lattice thermal conductivity and a greater power factor for Mg₂TeSe, and ZT increasing with temperature to maxima ≈ 0.32 (Mg2TeS) and 0.24 (Mg2TeSe) at 1200 K, illustrating Mg2TeSe’s promise for thermoelectric applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Band gap engineering is an important field of study that focuses on adjusting the band gaps of various optical materials for their specific device applications. Mg-based chalcogenides such as MgS, MgSe, and MgTe are wide band gap semiconductors with significant scientific value owing to their extensive uses in optoelectronic and luminous appliances1,2. Some substantial experimental and theoretical studies were carried out on their crystalline phases of rock salt (B1), zincblende (B3), and wurtzite (B4)3,4,5. At room temperature, MgS and MgSe adopt the B1 configuration6; however, other researchers have suggested alternative firm structures for these MgTe-based systems. Investigational research reveals that MgTe crystallizes in the B4 configuration under normal conditions7,8 and transforms to the NiAs (B8) structure under high pressure. In theory, Gokoglu et al.9 employed the projector augmented wave technique to determine the structures of MgS and MgSe as B1 and MgTe as B8. Drief et al.10 used the (FP-LAPW) approach to argue that B1 was the most stable structure for all three compounds, MgS, MgSe, and MgTe. The electronic structural and thermodynamic features of magnesium chalcogenide ternary alloys are examined employing first-principles approaches11. The high magnesium-ion mobility of ternary spinel chalcogenides is examined to assess their potential for energy storage applications12. McKeever et al.13 studied the design, features, and functional possibilities of alkali metal and Mg-based ternary chalcogenides for advanced applications. Debnath et al.14 employed density functional theory to study the structural, elastic, and optoelectronic features of the cubic BexMg1−xS, BexMg1−xSe, and BexMg1−xTe semiconducting alloys. Khare et al.15 studied the electronic, optical, and thermoelectric features of sodium and magnesium pnictogen chalcogenides with first-principles calculations. Yaqoob et al.16 performed an ab initio study on the structural, electronic, and thermodynamic properties of ternary XCo2S4 chalcogenides (X = Mg, Zn). Thangavel et al.17 used first-principles simulations to explore the ground-state features and structural phase transitions of ternary chalcogenide semiconductors under high pressure. MgGeO3 and MgSnO3, interesting materials are studied for their visible-light-driven energy applications because to their tunable structural, electronic, and photocatalytic features, primarily under applied stress18. Furthermore, substantial direct fundamental band gaps have been seen in the zinc-blende structures of MgS, MgSe, and MgTe19,20,21. The combination of same-chalcogen diatomic magnesium and Br chalcogenides with varying concentrations could produce several distinct triple amalgams with entirely dissimilar and intriguing physical features. A theoretical study22,23 investigates the optoelectronic features of BexMg1−xX (where X = S, Se, or Te) ternary materials. Sajid et al.24 studied indirect band gap semiconductors MgS, MgSe, and MgTe, resulting in the formation of direct band gap semiconductors MgSxSe1−x, MgSxTe1−x, and MgSexTe1−x with x values ranging from 0.25 to 0.75. It was observed that both ε1(0) and σ(0) change in distinct directions depending on the dopant concentration. At x = 0.75, the essential points and highest places in the visual spectra of the three compounds shift northward. MgSxTe1−x materials exhibit a broad energy band gap and large stationary dielectric constant values at x = 0, 0.25, and 0.50, making them ideal for optoelectronics and microelectronic devices25. The electronic, optical, and transport properties of MgCdO2 and MgCdS2 materials are calculated using the density functional theory calculations26.

Hassan et al.11 used the FP-LAPW approach to analyze the physical, electronic, and thermal nature of the MgSxSe1−x, MgSexTe1−x, and MgSxTe1−x compositions. This study overcomes these constraints by employing Boltzmann transport calculations and first-principles density functional theory (DFT) to investigate the impact of chalcogen (S and Se) on the electronic structure, optical, and TE characteristics of these Mg-based systems. Our study reveals that Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe are distinct ordered ternary compounds that crystallize in the R3m structure. These stoichiometries have not been fully investigated using a first-principles approach. The ability of ordered compounds to combine the preferred chemical bonding environment of chalcogen binaries with the increased structural flexibility and tunability offered by ternary ordering, which can result in improved thermodynamic stability and optimized transport behavior, is what drives the choice of these specific stoichiometries and crystal symmetry. Ordered compounds, as compared to random solid solutions, allow predictable site occupation, which makes it possible to investigate the formation energies, band dispersions, and effective mass trends more clearly. Furthermore, by balancing lighter (S/Se) and heavier (Te) chalcogen elements, they can also enhance carrier mobility and introduce phonon scattering paths appropriate for thermoelectric performance. Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe are predicted to provide performance improvements over their binary counterparts. Our present study analyzes a structural theme known to be stable in equivalent chalcogenides and is anticipated to produce a favorable mixture for electronic and thermal transport properties by focusing on the R3m symmetry. The present research shows that S and Se greatly improve the thermoelectric figure of merit by methodically examining band structure modifications, carrier transport improvements, and phonon scattering mechanisms. The findings open the door for the development of next-generation thermoelectric materials while providing vital insights into how focused chemically substituted materials might maximize the relationship between thermal resistance and electrical conductivity. Additionally, providing significant design techniques for improving the effectiveness of Mg-based optoelectronics and thermoelectric devices, the present investigation increases fundamental knowledge and renders them attractive choices for sustainable energy applications.

Computational methodology

All computations in this study were performed with the exceptionally accurate (FP-LAPW + lo) technique, which is applied in the WIEN2k code and built on DFT27. DFT calculates a system’s total energy as a function of electron density and solves the Schrödinger equation with only atomic numbers as input parameters, and has become an enormously influential tool for researching the physical and chemical features of an extensive variety of compounds28. DFT was similarly a common approach for researching precise effects that are hard or impossible to identify via testing, as well as forecasting novel materials. It is occasionally used to substitute expensive or impossible-to-complete laboratory experiments. To account for electron correlation and exchange effects, the structural and elastic properties were computed with Wu and Cohen’s proposed general gradient approximation (WC-GGA)29. In contrast, electrical features were evaluated using the Tran-Blaha modified Becke-Johnson (TB-mBJ)30. Spherical harmonic functions are amplified to improve the wave function, charge density, and potential of the muffin-tin spheres, while a plane-wave basis set is used in the interstitial area. To obtain appropriately accurate data for the energy junction while calculating eigenvalues, wave functions are extended using a plane-wave basis set in the interstitial region, with an RMT×Kmax cut-off limit of 7. RMT stands for the minimum muffin-tin radius, while Kmax represents the highest k-vector value used in the plane-wave expansion. The maximum value chosen to increase the electron density inside these muffin tin spheres was l = 10. To mix into the (BZ), we employed a modified tetrahedron method with an 11 × 11 × 7 mesh in k-space. Using the Monkhorst-Pack approach, we obtained 84 k-points in the IBZ. Self-consistent computations were deemed to have converged when the system’s total energy stabilized within a 0.0001 Ry range.

Results and discussion

Structure properties

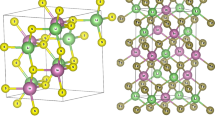

Mg2TeS exhibits an Enargite-like structure that develops in the trigonal R3m space group (see Fig. 1). These are two unequal Mg2+ sites. In that primary Mg2+ site, Mg2+ bonds with one Te2− and three identical S2− atoms to generate edge-sharing MgTeS3 tetrahedra. The Mg-Te bond distance was 2.81 Å. Wholly Mg-S bonds were 2.580 Å. In that, another Mg2+ site, Mg2+, bonds with three comparable Te2− and one S2− atoms to produce corner-sharing MgTe3S tetrahedra. All the Mg-Te bonds measure 2.740 Å. That Mg-S bond distance is 2.47 Å. Te2− bonds with four Mg2+ atoms, resulting in TeMg4 tetrahedra, sharing corners with six TeMg4 tetrahedra and six SMg4 tetrahedra. S2− connects to four Mg2+ atoms that forms SMg4 tetrahedra, sharing corners alongside six TeMg4 tetrahedra and six SMg4 tetrahedra. Mg2TeSe has a Cu3AsS4-like structure and develops in the triangular R3m space group. A total of two equivalent Mg2+ positions. In that first Mg2+ site, Mg2+ bonds to one Te2− and three identical Se2− atoms, resulting in edge-sharing MgTeSe3 tetrahedra. The Mg-Te bond length was 2.801 Å. Altogether, Mg-Se bonds are 2.670 Å. In the second Mg2+ location, Mg2+ bonds with three Te2− and one Se2− atoms, resulting in corner-sharing MgTe3Se tetrahedra. All Mg-Te bonds range from 2.770 Å. The Mg-Se bond distance was 2.601 Å. Te2− bonds with four Mg2+ atoms, resulting in TeMg4 tetrahedra, which distribute edges with six TeMg4 tetrahedra and six SeMg4 tetrahedra. The cohesive energy of a substance indicates the strength of bonding among its constituent atoms, while the formation energy demonstrates its thermodynamic stability with its constituent components. Mg2TeS possesses slightly smaller cohesive energy (-3.65 eV/atom) than Mg2TeSe (-3.79 eV/atom), implying stronger bonds. This is probably owing to the greater electronegativity and bonding strength of selenium (Se) compared to sulfur.

The predicted formation enthalpies (ΔHf) for Mg2TeS (− 2.17 eV/atom) and Mg2TeSe (− 2.53 eV/atom) reveal that both materials are exothermic relative to their constituent elemental reference states. This indicates a thermodynamic preference for formation from elements under the chosen reference convention. The uncertainties (± 0.05 eV/atom) are careful predictions based on DFT convergence sensitivity (k-points, cutoff). The ΔHf values are per atom and link to the elemental end members given. Mg2TeSe’s negative Ecoh and ΔHf suggest a larger overall binding and driving force for formation compared to Mg2TeS, which renders it intrinsically more favorable in the Mg-Te-Se chemical space. To attain true phase stability, the convex-hull (ΔEhull) of all competing phases in the Mg-Te-S/Se space, such as MgTe, MgSe, MgS, MgX2 stoichiometries, and reported ternaries, needs to be evaluated in addition to elemental-referenced ΔHf. ΔEhull = 0 eV/atom implies thermodynamic stability (on the hull), whereas modest positive ΔEhull values (generally ≈ 25–50 meV/atom) represent metastability and kinetic accessibility, and greater positive values indicate probable breakdown. Both compounds are appealing possibilities for synthesis, but specific stability judgments need explicit hull construction. The calculated cohesive and formation energies indicate that Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe are thermodynamically advantageous, with negative values reflecting structural integrity and compound stability. When compared to reference states (hcp-Mg, α-S8, trigonal Se, and trigonal Te) (see Table 1), these materials have low formation energy, indicating that they are resilient against decomposition. Mg2TeSe, with a greater negative formation energy than Mg2TeS, is expected to be slightly more stable. Possible competitive phases, including MgS, MgSe, and MgTe binaries, are less favorable, indicating the ternary compounds’ strong phase stability. Mg2TeSe has a lower formation energy (-2.53 eV/atom) compared to Mg2TeS (-2.17 eV/atom), showing its thermodynamic stability. It demonstrates that substituting sulfur with selenium promotes the structural stability of the compound. Magnesium (Mg) contributed considerably to the stability of both materials by strong electrostatic interactions with chalcogen atoms, while tellurium (Te), which is larger and less electronegative, influences lattice dynamics and electronic characteristics. The discrepancy in formation and cohesive energies can be caused by differences in atomic size and electronegativity between S and Se. Se, being larger than S, forms slightly longer but stronger connections in this structure, giving greater cohesive energy. Mg2TeSe is a little more stable than Mg2TeS, as demonstrated by their negative formation energies. This pattern aligns with the usual behavior of chalcogenides, as Se-based compounds often demonstrate greater stability and bonding interactions than their sulfur counterparts. Mg2TeSe is anticipated to have greater structural integrity and functional characteristics than Mg2TeS. Figure 2a,b displays the fluctuation of the whole energy as a function of volume (in atomic units cubed) for two distinct materials, Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe. The curves have a parabolic tendency, as expected of a state equation such as the Birch-Murnaghan or Murnaghan equation, in which the minimum energy is linked to the material’s equilibrium volume. The depth and position of the minimum offer provide information about the stability and structural qualities of each material. The Mg2TeS material has a lower equilibrium volume than Mg2TeSe, indicating a more compact structure. Mg2TeS has a lower equilibrium energy than Mg2TeSe, which suggests that it is more stable. The substitution of selenium (Se) for sulfur (S) results in an increase in volume, which is due to selenium’s higher atomic radius. This increase in volume has an impact on bonding interactions, which may modify mechanical and thermoelectric properties. Understanding these distinctions is critical for applications where these materials’ structural and electrical properties influence their performance, such as thermoelectric devices.

Electronic properties

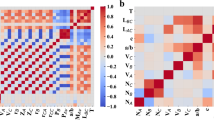

Density of states investigations demonstrate how orbital contributions influence the electronic properties of Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe. Orbital interaction affects the effective mass of charge carriers, which explains variances in transport performance. These characteristics have a direct impact on the Seebeck coefficient, carrier mobility, and optical absorption edges, all of which contribute to density of states characteristics throughout transport and optoelectronic effectiveness. Figure 3a,b displays the density of Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe states in that valence band region. The variations in the density of state changes for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe in the valence band region are mostly caused by changes in the electronegativity, atomic radius, and bonding characteristics of sulfur and selenium. Sulfur has more electronegativity of 2.58 compared with a 2.55 for selenium. This indicates that Sulfur attracted electrons more strongly than Se, resulting in more tightly packed bonding states and a shift in energy levels. As a result, Mg-s and Mg-p contributions move deeper in energy than Mg2TeSe. The Mg-s contribution is dominant in the − 4.0 eV to -3.0 eV range for Mg2TeS, although it is found at a lower energy series of -3.01 eV to -2.01 eV in Mg2TeSe. In Mg2TeS, the stronger Mg-S contact causes more mixing of s and p states at lower energy levels, whereas in Mg2TeSe, the weaker Mg-Se interaction causes Mg-s and Mg-p states to emerge at larger energy levels. In the CB range, both materials exhibit Mg-s and Mg-p contributions within the (3.0 to 6.0) eV range. This resemblance occurs because conduction band states are predominantly formed from Mg orbitals, with little effect from the anion S or Se. Te-s states dominate the valence band in Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe materials with energies ranging from − 4.01 eV to the Fermi level. Tellurium (Te) is a heavy chalcogen element with a low-energy s orbital. Te is more electropositive than S or Se, hence it has a stronger presence in the VB region. Contributions of Te-s/p/d states in the CB for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe materials between 3.8 and 6.0 eV. The conduction band states include contributions from Mg-s and Mg-d states, which interact with Te-s, Te-p, and Te-d states to generate hybridized bands. S-s states dominate the valence band contribution in Mg2TeS’s from (-4.0 to -1.5) eV because sulfur’s strong attraction to electrons results in more localized states in the lower energy range. In Mg2TeSe, the Se-s state contributes primarily to the Fermi level from − 3.01 eV, showing a shift in energy levels caused by Se’s lower electronegativity. This allows the Se-s states to extend to the Fermi level, whilst S states remain deeper. Se has a greater atomic radius compared to S, which impact the bond length and energy overlap between orbitals, bringing the DOS closer to the Fermi level. In that conduction band, states given by S-s/p and Se-s/p/d from 3.8 eV to 6.0 eV are mostly owing to contributions from Te-p states that interact with S and Se states. The S-p states provide a major contribution to Mg2TeS due to higher hybridization with Mg and Te. Because of the weaker binding in Mg2TeSe, the Se-p and Se-d states stretch further into the conduction band, resulting in more delocalized and dispersed electronic states than S.

Figure 4 illustrates the electronic band structures of Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe, revealing valuable information on their electrical properties. Both materials are semiconducting, with energy gaps that vary depending on the used functional. The TB-mBJ approach, both with and without SOC, yields more accurate estimates than WC-GGA, highlighting the significance of exchange-correlation treatment. The addition of SOC is especially important in Te-containing systems due to how it affects the valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM), leading to optical transition thresholds. These band gap properties have significant effects on carrier excitation energies, as well as the materials’ potential for optoelectronic and thermoelectric applications. The WC-GGA approach underestimates band gaps, providing 1.49 eV for Mg2TeS and 1.83 eV for Mg2TeSe as shown in Table 2. This is a common restriction of semilocal functions. Application of TB-mBJ corrects this underestimation, anticipating 2.86 eV and 2.95 eV for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe, respectively, resulting in more realistic values. Te-rich chalcogenides have strong relativistic interactions; hence, SOC was specifically incorporated. This leads to slightly smaller gaps of 2.64 eV (Mg2TeS) and 2.71 eV (Mg2TeSe). SOC-induced splitting at the valence and conduction band minimizes the band ordering at Γ, leading to a drop of approximately 0.2–0.25 eV in comparison with TB-mBJ. At all levels of theory, Mg2TeSe displays a narrower gap compared to Mg2TeS, demonstrating Se’s more delocalized p-states and stronger relativistic effects relative to S. Importantly, since WC-GGA underestimates and TB-mBJ slightly overestimates, SOC + TB-mBJ gives a balanced description of the band gap and band dispersion, ensuring accuracy in forecasting optical edges and transport performance. SOC is essential for Te-containing chalcogenides. Chemical substitution (S → Se) adjusts the band gap, influencing carrier effective masses and transport characteristics. Thus, the addition of SOC and TB-mBJ provides reliable electronic structural insights, which are vital when analyzing optical absorption and thermoelectric performance. Both Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe have direct band gaps (Γ-Γ), indicating that the (VBM) and (CBM) are at the Γ-point of the Brillouin zone. That property was determined by electronic interactions inside the crystal structure, such as orbital hybridization between Mg, Te, S, and Se atoms. The electrical configuration of magnesium is [Ne] 3s². In both Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe, the Mg-s and Mg-p states contribute to the VB and CB. The Mg-s state has a considerable influence in the region from − 4.01 eV to -3.0 eV for Mg2TeS and from − 3.0 eV to -2.0 eV for Mg2TeSe. This shift implies that Mg interacts differently with S and Se due to changes in electronegativity and bonding properties. Mg-s and Mg-p states dominate in both materials between 3.0 and 6.0 eV, demonstrating their importance in conduction. Te’s electronic setup is [Kr] 4d¹⁰5s²5p⁴. It makes a significant contribution to the valence and conduction bands. Te-s contributes − 4.0 eV to 0 eV in both materials, suggesting substantial hybridization with Mg and S/Se. Te-s, Te-p, and Te-d states contribute between 3.8 eV and 6.0 eV, emphasizing their involvement in conduction. In Mg2TeS, the S-s state contributes to the valence band region from (− 4.01 to − 1.5) eV, representing a durable bonding linking between S and Mg/Te. In that conduction band, the S-s and S-p states contribute between 3.8 and 6.0 eV. In Mg2TeSe, the Se-s state contributes to the − 3.0 eV Fermi level, indicating that Se hybridizes differently with Mg and Te than S. Se-s/p/d states contribute to the CB between 3.8 and 6.0 eV. The shifting contributions between Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe indicate that Mg2TeSe has a slightly smaller bandgap than Mg2TeS, as the Se states are at a higher energy level than the S states. Te-s and Te-p hybridization with Mg and S/Se are more prominent in both cases, but Mg2TeS has greater Mg-S bonding, shifting the S-s states lower in energy than Se-s in Mg2TeSe.

Optical properties

Figure 5a depicts the real dielectric constant, ε1(ω), which is calculated by the material’s ability to split in response to an external electrical field. At first, in both materials Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe, ε1(ω) rises as the input photon energy shifts electrons from the valence bands to the conduction bands, improving the material’s polarizability. The peaks at 5.0 eV indicate the most essential electronic transitions, and both materials have the highest ability to store electric field energy. At photon energies that exceed 5.0 eV, electrons absorb energy and transition to higher conduction states, leading to increased absorption. This absorption results in energy dissipation rather than polarization, resulting to a significant decrease in ε1(ω). When ε1(ω) approaches zero or becomes negative at 7.0 eV, both Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe materials behave like metals, with free carriers dominating the optical response over bound electronic transitions. Selenium has a higher atomic radius than sulfur, resulting in less orbital overlap in the valence band. This reduces the DOS around the band margins, slightly limiting the material’s capacity to polarize. Figure 5b depicts the imaginary dielectric constant, ε2(ω), for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe materials. The imaginary part of the dielectric function ε2(ω) was closely related to the interband optical variations from occupied VB to unoccupied CB states. That threshold energy where ε2(ω) begins to increase is linked to the minimal energy necessary for direct optical transitions, which is frequently near the fundamental band gap energy or somewhat higher due to selection rules and density of states effects. Mg2TeSe has a slightly lower threshold energy than Mg2TeS, implying a smaller optical band gap. This is consistent with the general trend that heavier chalcogens (Se rather than S) have smaller band gaps due to weaker bonding and lower energy separation between valence and conduction bands. The peak in ε2(ω) occurs at 5.5 eV for Mg2TeS and 5.8 eV for Mg2TeSe when the joint density of states (JDOS) and optical transition probabilities are maximum. After reaching the peak, ε2(ω) begins to fall as the JDOS lowers at higher energies due to fewer accessible states for transitions. At high photon energies (over 16.0 eV), ε2(ω) decreases to zero as the material becomes essentially transparent, and no substantial interband transitions are conceivable within the energy series.

In Fig. 5c, the functioning of the refractive index n(ω) as a function of photon energy can be clarified through fundamental optical physics concepts about the interactions of electromagnetic waves with the electronic structure of materials. Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe have identical static refractive index values of around 2.1, implying moderate optical density and relationship to low-energy electromagnetic waves. The refractive index n(ω) increases with photon energy from 0 eV, reaching its peak at 5.0 eV for Mg2TeS and 5.5 eV for Mg2TeSe. This rise is mostly caused by electronic interband transitions, in which photons drive electrons from the VB to the CB. That refractive index correlates with the dielectric function ε1(ω). A substantial electronic transition occurs at 5.0 eV for Mg2TeS and 5.5 eV for Mg2TeSe, resulting in a peak in the ε1(ω) and in n(ω). Beyond the peak, both materials’ refractive index n(ω) drops. Absorption is represented by the ε2(ω), which increases strongly at and beyond the peak. Since the refractive index depends on both real ε1(ω) and imaginary components of ε2(ω), an increase in absorption leads to a lower ε2(ω), lowering n(ω). The Kramers-Kronig relations explain how these real and imaginary parts of the dielectric function interact. When absorption (associated with ε2(ω)) increases significantly, the real component ε1(ω) begins to decrease, resulting in a decrease in n(ω). The absorption coefficient I(ω) indicates how strongly a substance absorbs light at various photon energies. Figure 5d illustrates the absorption spectra of Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe, which have unique threshold values of 4.0 eV and 3.5 eV, respectively, and peak intensities followed by a drop. The peak values result from transitions between higher energy levels in the valence and conduction band, which include a high (JDOS) and strong dipole transition matrix element. The maximum absorption occurs at 9.0 eV for Mg2TeS and 8.0 eV for Mg2TeSe. These peaks imply strong electronic transitions beyond the basic band gap, where more interband transitions occur. Absorption is heavily dependent on the density of electronic states (JDOS). Furthermore, at very high photon energies, many-body interactions, including electron-electron scattering and electron-phonon interactions, increase. These interactions can cause energy widening and redistribution of optical transitions, resulting in reduced absorption.

Considering the optical properties and electronic transitions in Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe may give insight into the behavior of static reflectivity R(0) and frequency-dependent reflectivity R(ω). Figure 5e demonstrates that both Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe possess a static reflectivity R(0) value of 0.12, showing that they have a low reflectivity in the long-wavelength (infrared) or zero-frequency limit. This number is determined by the material’s dielectric response, specifically the ε1(0). The reflectance R(ω) increases with photon energy, peaking at 10.0 eV for Mg2TeS and 8.0 eV for Mg2TeSe. These peaks link to strong interband electronic transitions, in which photons of this energy excite electrons in the VB and transport them towards the CB. The reflectivity peaks occur because the dielectric function responds strongly to these photon energies, indicating the onset of significant optical absorption. The shift in the peak energy between Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe can be attributed to differences in their electronic band structures. Mg2TeS, which contains sulfur (S) with a smaller atomic size and higher electronegativity than selenium (Se), has a wider band gap and requires more photon energy to induce major interband transitions, resulting in a peak at 10.0 eV versus 8.0 eV for Mg2TeSe. After peaking, R(ω) falls at higher photon energy. Figure 5f displays the energy loss function. The relationship between L(ω) and the dielectric function ε2(ω) is critical for understanding a compound’s plasmonic activity. The onset energy is typically linked to the plasma frequency, which is determined by free carrier density and electron effective mass. The minor difference in threshold energy between Mg2TeS at 5.5 eV and Mg2TeSe at 6.0 eV is owing to variances in electronic structures, notably carrier concentration and band structure. The peaks in L(ω) indicate the most significant energy loss caused by collective plasmon excitations. The largest loss occurs at energy levels of 17.0 eV and 16.0 eV, respectively, because the plasmon resonance requirement is met, indicating that the material responds strongly to external perturbations at these frequencies. The Landau damping effect causes L(ω) to diminish after reaching its peak.

Transport properties

The Seebeck coefficient (S) shown in Fig. 6a for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe compounds at temperatures ranging from 100 to 1200 K. The Seebeck coefficient expresses the power produced per unit temperature variation around a compound. At low temperatures (100 K), the carrier concentration is low, and the Seebeck coefficient is predominantly determined by the dominant charge carriers (electrons in this case, because S is negative). Figure 6a shows that at 100 K, the highest Seebeck coefficient values for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe are − 6.0 µV/K and − 9.0 µV/K, respectively. The higher Seebeck coefficient at this level indicates fewer free carriers and greater energy filtering effects. As the temperature rises (100–1200 K), intrinsic carrier excitation increases, leading to higher total carrier concentrations. The Seebeck coefficient is inversely associated with carrier concentration, resulting in a drop in S. At intermediate temperatures, enhanced phonon scattering affects charge carriers, changing the Seebeck coefficient even further. In strongly substituted semiconductors, ionized impurity and acoustic phonon scattering mechanisms dominate, resulting in a more significant drop in S. The decrease in S up to 900 K is due to both carrier excitation and scattering effects. Thermal excitation increases dramatically as temperatures near 1200 K, resulting in the creation of electrons and holes. This causes conduction, in which electrons and holes contribute oppositely to the Seebeck coefficient. Because of this effect, S has a minimum value of 1200 K, as contributions from both types of charge carriers effectively limit the overall magnitude of S. The observed similarity in Seebeck coefficient values for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe. At 1200 K, the highest electrical Mg2TeSe at high temperatures (-42.0 µV/K and − 43.0 µV/K) indicates that both materials display comparable intrinsic excitation behavior and carrier transport capabilities. In Fig. 6b, both Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe exhibit an increase in electrical conductivity (σ/τ) when the temperature rises from 100 K to 1200 K. Electrical conductivity (σ) is another important characteristic in thermoelectrics. It assesses the material’s ability to conduct electrical currents. The conductivity per relaxation time (σ/τ) is displayed against temperature. Both materials exhibit an increase in electrical conductivity with temperature. Mg2TeS has consistently better conductivity than Mg2TeSe over the whole range. Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe are most likely semiconductors, which means that their electrical conductivity is very temperature-dependent. The amount of thermally excited charge carriers is low at low temperatures due to the limited energy available to promote electrons over the band gap. The electrons possess sufficient energy to transit from the valence band to the conduction band, boosting carrier concentration and electrical conductivity. When the temperature rises from 100 K to 1200 K, more electrons are excited around the band gap, resulting in improved carrier concentration and σ. At 300 K, the electrical conductivity values for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe are virtually identical, indicating equal intrinsic carrier concentrations and effective masses. At 1200 K, the conductivity of both materials improves but remains relatively close, indicating that they have similar band structures and charge transport mechanisms. At around 300 K, the σ/τ values for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe are 2.27 × 1019 and 2.24 × 1019 (Ω m s)−1, respectively. At 1200 K, the values were 2.78 × 1019 and 2.76 × 1019 (Ω m s)−1 for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe, respectively.

Figure 6c illustrates a linear rise in electronic heat conductivity (κe) for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe when the temperature rises from 100 K to 1200.01 K. Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe exhibit a linear increase in electronic thermal conductivity (κe) from 100 K to 1200 K, owing to the temperature dependence of electrical conductivity (σ) and the Wiedemann-Franz law. At 300 K, Mg2TeS has a thermal conductivity of 0.5 × 1015 W m− 1− 1 s− 1, while Mg2TeSe has 1.0 × 1015 W m− 1− 1 s− 1, indicating that Mg2TeSe has a greater carrier transport efficiency. At 1200 K, the maximum numbers of κe for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe are 3.0 and 4.5 × 1015 W m− 1− 1 s− 1, respectively. This confirms that Mg2TeSe has higher electronic transport capabilities due to its more conductive structure. Mg2TeSe has a higher intrinsic electrical conductivity than Mg2TeS due to differences in band structure and carrier effective masses, as indicated by the κe difference between the two. The figure of merit ZT is an important quantity in thermoelectric materials since it dictates how efficiently they convert heat into electricity. Higher ZT values indicate improved thermoelectric performance, which is critical for applications such as waste heat recovery, power generation in spacecraft, and cooling and refrigeration. Fig. 6d illustrates the behavior of the figure of merit ZT for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe. ZT for both Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe increases approximately linearly from 100 to 1200 K. In semiconductors, when the temperature rises, more charge carriers (electrons or holes) are thermally activated, enhancing electrical conductivity. ZT results in a rising trend in ZT. At high temperatures, both intrinsic carrier excitation and reduced phonon transport improve thermoelectric performance. This leads to a nearly linear increase in ZT. Figure 6d reveals that ZT values at 300 K are 0.05 and 0.03 for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe, respectively. The greatest figure of merit, ZT values at 1200 K are 0.32 and 0.24 for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe, respectively. Mg2TeS has somewhat greater ZT than Mg2TeSe across the full range. Minor variations in band convergence or (DOS) near the Fermi level between Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe may improve carrier transport characteristics in Mg2TeS. ZT is projected to grow with temperature as electrical conductivity improves and the material becomes more efficient.

The variation in lattice thermal conductivity (κl) with temperature for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe in Fig. 6e reveals a clear declining trend. This is consistent with the general behavior of crystalline semiconductors, where higher phonon-phonon scattering dominates at high temperatures. At low temperatures, κl is higher due to less scattering. Still, as the temperature rises, phonon-phonon Umklapp interactions intensify, leading to a rapid decrease. Mg2TeS consistently outperforms Mg2TeSe in terms of κl across all temperatures. The lighter atomic mass of sulfur relative to selenium results in stronger bonding and greater phonon group velocities in Mg2TeS, increasing its heat conductivity. The heavier selenium atoms in Mg2TeSe increase lattice anharmonicity, increase phonon scattering, and decrease κl. Mg2TeS may have slightly stronger heat conduction, but Mg2TeSe possesses a greater potential for thermoelectric applications due to its lower inherent κl. Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe display a continuous increase in power factor (PF = S2σ) as temperature rises (see Fig. 6f), consistent with thermoelectric semiconductors. At greater temperatures, electrical conductivity (σ) improves because of increased carrier activation, whereas the Seebeck coefficient (S) remains large enough to support PF formation. Mg2TeSe exhibits greater PF than Mg2TeS across the temperature range, implying better electronic transport properties. The heavier selenium atom improves band convergence and retains modest conductivity. Mg2TeS, with lighter sulfur atoms, exhibits stronger bonding but lower band degeneracy, resulting in limited PF values. Mg2TeSe is the most attractive thermoelectric contender because of its high PF and decreased lattice thermal conductivity (κl), which can lead to higher ZT values. Mg2TeSe exceeds Mg2TeS in thermoelectric applications because of its greater balance of low κl and high power factor.

Conclusions

The present first-principles calculation for Mg2TeS and Mg2TeSe yields strong and complementary results of their structural, electronic, optical, and transport studies. structurally both materials crystallize in trigonal R3m shapes with distinct polyhedral motifs and calculated bond lengths (Mg–Te ≈ 2.74–2.81 Å, Mg–S ≈ 2.47–2.58 Å, Mg–Se ≈ 2.60–2.67 Å), Mg2TeSe exhibits a greater equilibrium volume whereas Mg2TeS is more compact, and energetic metrics demonstrate negative cohesive energies (Ecoh: -3.65 eV/atom for Mg2TeS, and − 3.79 eV/atom for Mg2TeSe) and formation enthalpies (ΔHf: −2.17 and − 2.53 eV/atom), suggesting thermodynamic favorability with Mg2TeSe slightly greater stable; electronically both materials are direct-gap semiconductors at Γ-point with WC-GGA underestimating the band gaps, and SOC + TB-mBJ giving balanced values. Likewise the Mg and Te orbitals dominating conduction and valence edges respectively and substitution S→Se narrows the gap and shifts DOS towards the Fermi level; optically both materials display strong interband responses with ε1(ω) and refractive index peaking close to 5.0–5.5 eV, ε2(ω) peaks at ~ 5.5–5.8 eV, static refractive index ≈ 2.1, absorption thresholds at ~ 4.0 eV for Mg2TeS and ~ 3.5 eV for Mg2TeSe, minimal static reflectivity R(0) ≈ 0.12 and plasmonic loss peaks at ≈ 17.0 and 16.0 eV; transport computations demonstrate small Seebeck magnitudes at low T, enhancing electrical conductivity with T (σ/τ ≈ 2.27 × 1019 and 2.24 × 1019 (Ω·m·s)−1 at 300 K), κe and κl trends where Mg2TeSe has smaller lattice thermal conductivity and higher power factor, and ZT increasing with temperature to maxima of ≈ 0.32 (Mg2TeS) and 0.24 (Mg2TeSe) at 1200 K, making Mg2TeSe a promising thermoelectric candidate because to its favorable PF/κl balance.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Liu, J., Guo, T. F. & Yang, Y. Erratum: Effects of thermal annealing on the performance of polymer light emitting diodes. J. Appl. Phys. 91, 9437–9437 (2002).

Asano, T., Funato, K., Nakamura, F. & Ishibashi, A. Epitaxial growth of ZnMgTe and double heterostructure on GaAs substrate by metalorganic chemical vapor deposition. J. Cryst. Growth. 156, 373–376 (1995).

Jobst, B., Hommel, D., Lunz, U., Gerhard, T. & Landwehr, G. Band-gap energy and lattice constant of ternary Zn1 – xMgxSe as functions of composition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 69, 97–99 (1996).

Xia, C. et al. Experimental and theoretical studies on luminescent mechanisms and different visual color of the mixed system composed of MgGeO3: mn, Eu and Zn2GeO4: Mn. Int J. Mod. Phys. B. 34, 2050216 (2020).

Charif, R., Makhloufi, R., Selmi, O. R., Mouna, S. C. & Khan, W. The investigation of the physical properties and bandgap engineering of the antimony trirutile phase-based magnesium under hydrostatic pressure. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 179, 114758 (2025).

Peiris, S. M., Campbell, A. J. & Heinz, D. L. Compression of MgS to 54 GPa. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 55, 413–419 (1994).

Waag, A., Heinke, H., Scholl, S., Becker, C. R. & Landwehr, G. Growth of MgTe and Cd1 – xMgxTe thin films by molecular beam epitaxy. J. Cryst. Growth. 131, 607–611 (1993).

Li, T. et al. Jr. High pressure phase of mgte: stable structure at STP. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 5232–5235 (1995).

Gökoğlu, G., Durandurdu, M. & Gülseren, O. First principles study of structural phase stability of wide-gap semiconductors MgTe, MgS and MgSe. Comput. Mater. Sci. 47, 593–598 (2009).

Drief, F., Tadjer, A., Mesri, D. & Aourag, H. First principles study of structural, electronic, elastic and optical properties of MgS, MgSe and MgTe. Catal. Today. 89, 343–355 (2004).

El Haj Hassan, F. & Amrani, B. Structural, electronic and thermodynamic properties of magnesium chalcogenide ternary alloys. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 19, 386234 (2007).

Canepa, P. et al. & Yan, W. High magnesium mobility in ternary spinel chalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 8, 1759 (2017).

McKeever, H., Patil, N. N., Palabathuni, M. & Singh, S. Functional alkali metal-based ternary chalcogenides: Design, properties, and opportunities. Chem. Mater. 35, 9833–9846 (2023).

Debnath, B. et al. Structural, mechanical and optoelectronic properties of cubic BeₓMg₁₋ₓS, BeₓMg₁₋ₓSe and BeₓMg₁₋ₓTe semiconductor ternary alloys: A density functional study. Bull. Mater. Sci. 43, 59 (2020).

Khare, I. S., Szymanski, N. J., Gall, D. & Irving, R. E. Electronic, optical, and thermoelectric properties of sodium pnictogen chalcogenides: A first-principles study. Comput. Mater. Sci. 183, 109818 (2020).

Yaqoob, U., Atiq, A., Ain, Q. T., Kalsoom, A. & Rasul, M. N. A comprehensive ab-initio study of ternary XCo₂S₄ (X = Mg, Zn) chalcogenides. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 189, 109261 (2025).

Thangavel, R., Prathiba, G., Naanci, B. A., Rajagopalan, M. & Kumar, J. First-principle calculations of the ground state properties and structural phase transformation for ternary chalcogenide semiconductor under high pressure. Comput. Mater. Sci. 40, 193–200 (2007).

Khan, W., Charif, R., Masood, M. K., Jamil, A. & Karamti, H. Band gap engineering of Mg-based Germanate and Stannate oxides for sustainable photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 208, 113176 (2026).

Watanabe, K. et al. Optical properties of ZnTe/Zn₁–ₓMgₓSeTe₁– quantum wells and epilayers grown by molecular beam epitaxy. J. Appl. Phys. 81, 451–455 (1997).

Kirfel, A., Hinze, Е. & Will, G. J. The rhombohedral high pressure phase of MgGeO3 (ilmenite): synthesis and single crystal structure analysis, Z. Kristallogr. Cryst. Mater. 148, 305–318 (1978).

Liu, X., Bindley, U. & Sasaki, Y. Optical properties of epitaxial ZnMnTe and ZnMgTe films for a wide range of alloy compositions. J. Appl. Phys. 91, 2859–2865 (2002).

Litz, M. T. et al. Epitaxy of Zn1 – xMgₓSeTe1– on (100) InAs. J. Cryst. Growth. 159, 54–57 (1996).

Furdyna, J. K., Luo, H. & Dobrowolska, M. Zeeman-tuning of heterostructures consisting of semimagnetic and non-magnetic semiconductors. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 32, 359 (1993).

Bensaid, D. et al. Band gap engineering of semiconductors. Int. J. Met. 2014, 1–7 (2014).

Sabir, B. et al. Bandgap engineering to tune the optical properties of BexMg(S, Se, Te) alloys. Chin. Phys. B. 27, 016101 (2018).

Gul, B., Khan, M. S., Abu-Farsakh, H., Ahmad, H. & Thounthong, P. First-principles analysis of novel Mg-based group II-VI materials for advanced optoelectronics devices. J. Solid State Chem. 318, 123726 (2022).

Luitz, J. et al. Partial core hole screening in the CuL₃EdGe. Eur. Phys. J. B. 21, 363–367 (2001).

Blaha, P. et al. J. Chem. Phys. 152 074101 (2020).

Wu, Z. & Cohen, R. E. More accurate generalized gradient approximation for solids. Phys. Rev. B. 73, 235116 (2006).

Tran, F. & Blaha, P. Accurate band gaps of semiconductors and insulators with a semilocal exchange-correlation potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 226401 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2503).

Funding

This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2503).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M. S. K.: Software, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft review & editing. M A: Software, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft review & editing. S. N.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Writing - original draft review & editing. S. M. A.: Software, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, M.S., Al-Hmoud, M., Nabirye, S. et al. Exploring multifunctional properties of ternary chalcogenides for advanced energy applications. Sci Rep 15, 41728 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27927-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-27927-5