Abstract

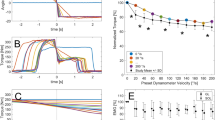

Push-ups enhance upper body strength without special equipment, yet the impact of different inclinations on intensity is not well-understood. Although the load-velocity relationship is established in resistance training, its relevance to push-ups needs further exploration. Previous studies have suggested that inclination affects muscle activation, but accurate models for predicting exercise intensity remain underdeveloped. To address this gap, this study aims to develop a reliable predictive model based on ground reaction forces measured during push-ups performed at different inclinations and speeds. Twenty-seven male university students participated, performing push-ups at 10°, 20°, and 30° inclinations with feet elevated, at three metronome-enforced tempos (7 reps/10 s, 5/10 s, and 4/10 s). Body measurements, vertical ground reaction forces, and average speeds were recorded for each angle. This study developed a predictive model for vertical ground reaction force during push-up exercises that incorporates body mass, incline angle, and movement tempo. Force data were collected with a Kistler force platform (Model 9281EA, Switzerland) and modeled via multiple linear regression. Agreement between predicted and measured forces was summarized using Bland–Altman analyses: mean biases were small (|bias| ≤ 16.66 N) and the 95% limits of agreement were approximately ± 104–206 N across conditions. Significant angle-specific associations were observed between tempo and force. At 10°, maximum force correlated with fast (r = 0.58, p = 0.005) and medium tempos (r = 0.69, p < 0.001). At 20°, all tempos correlated with maximum force, most strongly at slow tempo (r = 0.74, p < 0.001), and minimum force correlated with medium (r = 0.61, p < 0.001) and slow tempos (r = 0.75, p < 0.001). At 30°, both fast (r = 0.55, p = 0.009) and slow tempos (r = 0.54, p = 0.010) were associated with maximum force. These findings support the use of the model to inform individualized load prescription across common incline angles and tempos. Within the tested conditions (10°, 20°, 30° and three tempos), the regression model showed moderate predictive performance with acceptable agreement between predicted and measured forces. The 20° models for minimum force performed best at medium and slow tempos. Because body mass was a positive predictor of force across angles, individual body mass should be considered when prescribing push-up intensity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Strength training plays a critical role in various sports; however, the biomechanical mechanisms underlying upper-limb strength training remain insufficiently quantified, often leading to a lack of individualized load prescription. This is particularly evident in lower-limb-dominant sports, where upper-body strength development is frequently overlooked, ultimately impairing overall athletic performance and muscular balance1. The push-up, a widely adopted upper-body exercise valued for its practicality and minimal equipment requirements2,3,4, is effective not only for improving upper-limb strength5 and local muscular endurance6 but also commonly incorporated into physical fitness assessments7. By modifying hand and foot positions to perform different push-up variations, this exercise can enhance upper-body muscle activation while reducing joint stress, making it a efficient option for home-based training8,9,10. Nevertheless, predictive models for estimating ground reaction forces under different inclination angles and movement tempos are still underdeveloped, limiting the precision of intensity modulation in practice. This study aims to develop a biomechanics-based predictive model to address this gap and provide a theoretical foundation for individualized load quantification in push-up training.

Velocity-Based Training (VBT) is grounded in the well-established physiological principle that movement velocity is closely related to the percentage of one’s one-repetition maximum (%1RM), providing an objective basis for regulating training intensity in real time11,12. This approach allows coaches and athletes to monitor neuromuscular performance and adjust loads dynamically based on daily readiness13,14,15. The present study is conceptually situated within the VBT framework, with the aim of extending its application to inclined push-up exercises—a common yet understudied closed-chain upper-body movement. While prior research has examined the effects of movement speed on push-up performance16,17, the load-velocity profile and force characteristics of push-ups performed under different inclination angles and tempos remain poorly quantified. This gap is particularly relevant given the growing use of push-ups in both athletic and recreational training settings. By investigating the relationship between kinematic variables (inclination and tempo) and kinetic outputs (vertical ground reaction forces), this study seeks to establish a predictive model that can support evidence-based application of VBT principles in upper-limb training. The findings are expected to contribute to more individualized and precise programming of push-up exercises, thereby enhancing both performance outcomes and training safety.

The simplicity of the push-up technique makes it suitable for both beginners and experienced trainers. It is frequently incorporated into dynamic warm-ups and bodyweight training routines, and is widely used in upper limb rehabilitation, especially for patients with shoulder injuries17. Additionally, push-ups are an effective method for assessing upper limb muscle strength and endurance18. The primary resistance in standard push-ups comes from the individual’s body mass19,20,21, making them a valuable strength-building exercise that can easily fit into daily workout routines17,18.

For home-based training, adjusting push-up positions to modify force output offers a practical and feasible approach. In the early stages of training, frequent 1RM upper limb strength tests can induce physical and mental fatigue. To address this, our study introduces a predictive model for estimating force during elevated push-ups, which broadens the application of upper limb strength assessments. Incorporating this digital testing method into training not only alleviates the psychological fatigue associated with repeated testing but also provides a clearer understanding of performance levels. This model has significant practical value for both beginners and experienced trainers in designing and executing personalized training programs.

This study applies the load-velocity relationship—a foundational concept in strength training—to push-up exercises under various inclines and tempos. While well-established for free-weight exercises, this relationship remains under-explored in closed-chain movements like push-ups. We use movement velocity to predict external load (measured as vertical ground reaction force), extending velocity-based training principles to bodyweight exercise. The goal is to develop a quantitative framework for prescribing and monitoring push-up intensity based on individual biomechanics.

Methods

Participants

Sample size was determined a priori using G’Power 3.1. A repeated-measures ANOVA (within factors) with an assumed medium effect size (f = 0.25), α = 0.05, and power = 0.95 indicated a required sample of 22 participants. Accounting for 20% potential attrition, 27 male undergraduates from Beijing Sport University were recruited. Inclusion criteria included: (1) ≥ 1 year of sports training; (2) no recent injuries; (3) proficiency in push-ups per Bushman22. Exclusion criteria were: (1) inadequate sports experience; (2) recent injuries; (3) inability to perform proper push-ups. All 27 participants completed the study (Table 1).

Human ethics and consent to participate declarations

This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Beijing Sport University Ethics Committee (approval number: 2022002H). The research design met ethical standards, and participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose, benefits, risks, and their rights before providing written consent. They were also informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without affecting their future services, and any data from withdrawn participants would be excluded from the analysis.

Experimental design

After familiarization with the experimental protocol, all 27 participants completed push-up trials under three elevation conditions in randomized order: (1) 10° incline (Fig. 1A), (2) 20° incline (Fig. 1B), and (3) 30° incline (Fig. 1C). The inclination angles were precisely set and verified using a digital inclinometer prior to each testing session. The platform height was individually adjusted according to each participant’s lower limb length to ensure biomechanical consistency and angle accuracy across participants.

These angles were selected to systematically examine the effect of progressively increasing intensity on muscle activation and performance. The 10° condition served as a mild elevation commonly used in rehabilitative and introductory strength training, while the 20° and 30° inclines introduced graduated challenges to the upper body musculature. All participants wore standardized compression clothing to minimize clothing-related measurement variance and facilitate consistent motion capture.

Each condition was performed in a separate session with a 48-h interval between tests to minimize fatigue. Within each session, participants performed push-ups at three different tempos (7 push-ups/10 s, 5/10 s, and 4/10 s), guided by a metronome16,23,24,25. Vertical ground reaction forces were recorded using a Kistler force platform (Model 9281EA, Winterthur, Switzerland), and movement velocity was recorded with a GymAware linear position transducer (PowerTool, Kinetic Performance Technology, Australia). A 15-min rest period was enforced between sets. Prior to testing, anthropometric data including height and weight were measured. Warm-up consisted of joint mobilization, dynamic stretching, activation exercises, and light jogging, followed by 5 min of rest.

Intervention

Feet-elevation height calculation and angle verification

With the participant standing in anatomical position, we measured: c = torso length (acromion to greater trochanter, cm), a = arm length (acromion to wrist center with the elbow fully extended, cm), and d = force-platform height (floor to top plate, cm). For a target incline angle θ (relative to the horizontal, defined by the line from the acromion to the greater trochanter when the body is held rigid in a plank), the required feet-elevation height e was computed as:

We verified θ before each trial using a digital angle finder (DL7306, Deli, Ningbo, China; accuracy ± 0.05°) placed along the acromion–greater-trochanter line while the participant held the start position. Figure 2 shows the geometry and includes only the variables a, c, d, e, θ.

Definition of average concentric velocity (X₂) and tempo enforcement

A metronome enforced three tempos: 7 reps/10 s (1.43 s/rep), 5/10 s (2.00 s/rep), and 4/10 s (2.50 s/rep). Participants performed symmetrical repetitions (eccentric and concentric each occupying half of the rep duration) without intentional pauses. The linear position transducer provided rep-level velocity. For each repetition, concentric velocity was computed over the positive-displacement phase (from the sign change of velocity to zero velocity at the top). X₂ was defined as the mean concentric velocity across valid repetitions within each angle-by-tempo condition. Force- and velocity–time series were time-synchronized.

Push-up force value testing

Participants started in a standard push-up position, lifting their bodies in a straight line and bending their arms until their foreheads touched a yoga block. Before testing, the appropriate angle for each participant was calibrated based on group-specific requirements. Attempts where the body was not straight or the forehead did not touch the yoga block were invalid. Force values at different incline angles were recorded using a Kistler force platform (Model 9281EA) at 1000 Hz, low-pass filtered at 10 Hz, with peak-picking for maximum and minimum vertical forces.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (Version 26.0, IBM Corp., USA) and are presented as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD). For within-subject factors angle (10°, 20°, 30°) and rhythm (fast, medium, slow), we used a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (α = 0.05); Shapiro–Wilk tested residual normality and Mauchly’s test assessed sphericity, with Greenhouse–Geisser corrections as needed and Bonferroni post hoc tests. Effect sizes are partial η2.

Associations were examined with Pearson correlations. Multiple linear regression predicted vertical ground reaction force from body mass, angle, and average concentric velocity (X₂); standard assumptions were checked (linearity, independence, homoscedasticity, multicollinearity, influence). Agreement between measured and predicted forces was summarized using Bland–Altman mean bias and 95% limits of agreement; paired t-tests were not used for validation.

Results

Variation characteristics among angle, rhythm, body mass, and force values

A multivariate linear regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the influence of body mass, incline angle, and execution rhythm on vertical ground reaction force values. Prior to modeling, key regression assumptions were thoroughly examined. The linearity between each independent variable and the outcome was assessed using partial regression plots, while the independence of residuals was verified with the Durbin-Watson test (d ≈ 2.0). Homoscedasticity was confirmed by visual inspection of standardized residual versus predicted value plots.

Multicollinearity was evaluated using variance inflation factors (VIFs), with all predictors yielding VIF values below 5, indicating absence of multicollinearity. Outliers and influential cases were examined through studentized residuals (all < 3), leverage values (all < 0.2), and Cook’s distance (all < 1). Normality of the residuals was confirmed visually via a normal P-P plot and formally with the Shapiro–Wilk test (p > 0.05).

All three predictors significantly contributed to the model (p < 0.05). Detailed regression equations and coefficients are reported in Table 2. Agreement between measured and predicted forces is summarized in Table 3. Mean biases were small across conditions (− 0.02 to 16.66 N), with 95% limits of agreement ranging approximately from ± 104 to ± 206 N depending on condition. To avoid back-substitution bias, we did not use paired t-tests for validation.

Significant correlations between movement rhythm and force values were observed across all incline angles, with the strength and direction of correlations structured as follows:

10° Incline: Fast rhythm showed a moderate correlation with maximum force values (r = 0.58, p = 0.005), while medium rhythm exhibited a strong correlation (r = 0.69, p < 0.001).

20° Incline: All rhythms significantly influenced maximum force values (p < 0.05). Fast rhythm demonstrated a moderate correlation (r = 0.36, p = 0.006), while both medium (r = 0.58, p = 0.007) and slow rhythms (r = 0.74, p < 0.001) showed strong correlations. Minimum force values were also strongly correlated with medium (r = 0.61, p < 0.001) and slow rhythms (r = 0.75, p < 0.001).

30° Incline: Both fast (r = 0.55, p = 0.009) and slow rhythms (r = 0.54, p = 0.010) significantly predicted maximum force values with moderate to strong correlations.

Variations between angle and force values

A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (angle × rhythm), with Greenhouse–Geisser corrections where necessary, showed a significant main effect of angle on maximum force (F = 5.943, p = 0.003). When collapsing across angles, the main effect of rhythm on maximum force was not significant (p > 0.05), and the angle × rhythm interaction was not significant. Overall, maximum force decreased as the incline angle increased, indicating an inverse angle–force relationship. Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons for the angle main effect (ignoring rhythm) yielded non-weighted marginal means of 666.72 N at 10°, 663.10 N at 20°, and 595.61 N at 30° (Table 5). Accordingly, the maximum force at 10° exceeded 30° by 71.12 N (95% CI: 25.28–116.96, p = 0.03), and 20° exceeded 30° by 67.50 N (95% CI: 21.66–113.34, p = 0.04), whereas 10° vs 20° was not significant (Table 4).

Pairwise comparison analysis of main effects of incline angles—conducted to evaluate the independent impact of inclination on force output—revealed non-weighted marginal means of 666.72 at 10°, 663.10 at 20°, and 595.61 at 30°. These results clarify the fundamental force-angle relationship without the influence of rhythm. Ignoring rhythm, maximum force value at 10° was significantly higher than at 30° by 71.12 (95% CI 25.28–116.96, p = 0.03), and at 20° was higher than at 30° by 67.50 (95% CI 21.66–113.34, p = 0.04) (Table 5). These findings highlight a consistent decline in force production with increasing inclination, supporting the presence of a significant inverse force-angle relationship.

Variation characteristics between rhythm and force values

The study found no significant main effects of rhythm on either minimum or maximum force values (F = 0.813, p = 0.445; F = 0.253, p = 0.777), indicating that, overall, rhythm variations did not exert a systematic influence on force outputs. However, post hoc correlation analyses revealed more nuanced, angle-specific relationships. Pearson correlation analysis showed no general significant correlations across all conditions, but several rhythm- and angle-dependent associations were identified. These included a moderate positive correlation between fast rhythm and maximum force specifically at 20° (r = 0.50, p < 0.05), and strong positive correlations for medium-tempo rhythm with maximum force at 10°, 20°, and 30° (r = 0.63, 0.60, 0.80 respectively; p < 0.01). Slow rhythm demonstrated a moderate positive correlation at 10° (r = 0.49, p < 0.05) and very strong correlations at 20° and 30° (r = 0.63, p < 0.01), alongside a moderate negative correlation with minimum force at 20° (r = − 0.50, p < 0.05) (Table 6). When collapsing across angles, the main effect of tempo on maximum or minimum force was not significant; however, angle-specific associations emerged in correlation analyses. This pattern indicates that the influence of tempo is angle-dependent rather than a uniform main effect across all angles.

Discussion

Biomechanical Impact of Incline Angles on Push-Up Force Output

Adjustments in hand or leg positions can lead to various biomechanical changes, affecting muscle recruitment, activation, and joint forces26,27,28. Our study also found that maximum force values decrease with increasing angles for different rhythms, showing an inverse relationship. Notably, for push-ups at a 20° incline angle, force values significantly decrease across all three rhythms. At a 10° incline, force values for fast push-ups show a clear upward trend. However, when performing 20° incline push-ups at a moderate rhythm, force values rise and exceed those of fast rhythms. After accounting for rhythm (i.e., marginal means), maximum force at 10° exceeded 30° by 71.12 N (95% CI 25.28–116.96, p = 0.03) and 20° exceeded 30° by 67.50 N (95% CI 21.66–113.34, p = 0.04) (Tables 4–5). Previous studies have shown that force values in conventional push-ups28 and knee-flexion push-ups29 differ slightly from earlier results, ranging from about 64% to 66% and 49% to 53% of body mass, respectively. Changes in hand positions result in force values ranging from 52.9% to 72.9% of body mass. Further exploration revealed that push-ups with hands elevated to 60.96 cm produce vertical forces as low as 41% of body mass, whereas elevating the feet to the same height can increase vertical forces up to 74% of body mass30.

Our findings can be explained through biomechanical principles. At 10° or 20° inclines, the center of mass shifts horizontally relative to the support surface (hands), directly affecting the moment arm lengths at the shoulder and elbow joints31. The moment arm is a key factor in torque production; a longer moment arm can generate greater torque with the same muscle force output, thereby enhancing the force exerted by the muscles around the joints32,33,34. At a 20° incline, the moment arm lengths at the shoulder and elbow reach a balance, allowing the upper limb muscles (such as the pectoralis major, anterior deltoid, and triceps brachii) to work at an optimal mechanical advantage35. This optimal positioning not only maximizes force output but also reduces joint shear forces, thereby lowering the risk of injury36. Furthermore, the core muscles are more effectively engaged to stabilize the body at this angle, resulting in more direct and efficient force transmission37,38.

When the incline angle increases to 30° or higher, although the center of mass continues to move forward and the moment arm length increases, the shear forces at the shoulder joint significantly increase24. This additional stress requires the shoulder muscles to contribute more to joint stabilization, reducing the overall efficiency of force output39. Therefore, a 20° incline provides an ideal balance, maximizing force output while maintaining joint stability and safety35,36,40.

In our study, participants maintained a standardized hand position with shoulder-width spacing and kept the body in a straight line from head to toe throughout the movement. Hand position was individually adjusted to ensure consistency, as it plays a role as critical as inclination angle in determining exercise intensity and biomechanical output30. These observations align with the predictive model proposed in our study, which integrates body posture, joint kinematics, and timing parameters to estimate force output under various configurations.

Prior work has reported that modifying limb positioning can increase push-up loading by approximately 33%37. Our findings are directionally consistent with this evidence, although quantifying percentage increases was not the aim of the present study. Moore et al. reported that integrating standard postures, knee-flexed push-ups, and elevated-hand or elevated-foot variations into training regimens significantly enhances ground reaction forces—particularly in feet-elevated push-ups compared to other modalities38. This reinforces the importance of posture and limb placement, factors that our model systematically incorporates to improve prediction accuracy concerning force output and joint loading.

Thus, while hand and foot adjustments are often overlooked in conventional practice, their biomechanical effects are captured and quantifiable through our model, enhancing its applicability and explanatory power.

Influence of push-up rhythm on force generation

The choice of rhythm in push-up execution significantly influences performance, as excessively fast or slow rhythms may compromise technique or induce premature fatigue, thereby reducing the number of repetitions performed24,39,40. Numerous training protocols—with or without prescribed rhythm and time constraints—have been employed in push-up assessments41,42,43,44,45. This study identified a moderate to strong positive correlation between medium-to-fast rhythms and maximum force across various angles, underscoring that movement rhythm substantially affects ground reaction force. Efficient shifting between eccentric and concentric muscle contractions optimizes the stretch–shortening cycle (SSC), which facilitates elastic energy storage and release, thereby augmenting force production41. Conversely, overly rapid rhythms may curtail the efficacy of the SSC due to inadequate time for energy storage, while very slow rhythms can diminish force output as a result of reduced dynamic muscle activation.

The interplay between inclination angle, rhythm, and force further complicates this relationship. At a 10° incline, faster rhythms appear to enhance force output, likely owing to the elasticity and brief tension periods inherent in dynamic contractions. At 20°, a moderate rhythm proves most beneficial, balancing favorable joint moments with sufficient SSC utilization. At steeper inclines (e.g., 30°), both fast and slow rhythms correlate with decreased force, likely due to increased shoulder shear forces and compromised mechanical advantage.

These findings directly inform practical training applications. For instance, incorporating feet-elevated push-ups—which elicit higher ground reaction forces—into structured programs may maximize strength development44,45,46,47,48. As push-up variations continue to proliferate in fitness contexts49,50, it becomes possible to modulate external loading according to individual athlete mass and skill level51,52,53. Lighter individuals may use additional load to achieve comparable intensity to heavier athletes, who may instead use technique modifications to reduce load.

Notably, the predictive model introduced in this study offers a practical tool for estimating force output under various conditions, which can help customize push-up intensity for home-based or team training. However, the model has limitations: it does not fully account for inter-individual variability in biomechanics, muscle composition, or neuromuscular efficiency. Moreover, its accuracy may diminish under extreme angles or highly irregular rhythms. Future iterations could benefit from incorporating real-time biomechanical feedback or personal performance data.

Ultimately, this research provides a foundational model for force estimation in standard and modified push-ups, facilitating the design of individualized training programs and supporting load selection in group settings to improve athletic performance.

Conclusion

Across 10°, 20°, and 30° inclines and three tempos, the regression model integrating body mass, angle, and average concentric velocity provided moderate predictive performance with acceptable agreement between predicted and measured vertical ground reaction forces (Bland–Altman mean bias − 0.02 to 16.66 N; 95% limits of agreement ≈ ± 104–206 N). For minimum force, models at 20° performed most reliably under medium and slow tempos. Because body mass was a positive predictor across angles, it should be incorporated when prescribing push-up intensity.

These findings support condition-specific use of the model to program and monitor body-weight push-ups within the tested ranges of angles and tempos. In practice, coaches may adjust angle and tempo alongside body mass to achieve targeted force demands.

Limitations and future directions

This study was conducted with a homogeneous sample of male students from a sports university under controlled laboratory conditions with predefined tempos, and it did not explicitly model individual biomechanical differences such as limb segment lengths, muscle insertion geometry, or neuromuscular efficiency. These features limit external validity and may influence prediction accuracy when the model is applied beyond the tested context.

Future research should prioritize external validation and, where necessary, recalibration in women, competitive athletes, and tactical populations, as well as in field settings that introduce greater ecological variability. Incorporating anthropometric and biomechanical covariates would enable more personalized predictions and would allow assessment of model transportability across different body mass strata. It is also important to extend analyses to additional push-up variants, including decline push-ups, weighted push-ups, and unilateral push-ups, and to broader tempo schemes, and to report fold level performance metrics when k fold cross validation is used to document generalization.

Finally, translation into practice will benefit from the development and evaluation of sensor based real time prescription workflows that suggest angle and tempo to achieve a target force. These workflows should be tested in supervised, remote, and home environments and benchmarked against standard programming. These steps would help advance the framework into a more generalizable, individualized, and deployment ready tool for upper limb strength prescription using body mass exercise.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article. For specific requests, please feel free to contact the corresponding author at weihw@bsu.edu.cn.

References

Schaun, G. Z., Bamman, M. M. & Alberton, C. L. High-velocity resistance training as a tool to improve functional performance and muscle power in older adults. Exp. Gerontol. 156, 111593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2021.111593 (2021).

Calatayud, J. et al. Muscle activation during push-ups with different suspension training systems. J. Sports Sci. Med. 13(3), 502–510 (2014).

Borreani, S. et al. Muscle activation during push-ups performed under stable and unstable conditions. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 13(2), 94–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesf.2015.07.002 (2015).

Bezerra, E. S. et al. Effect of push-up variations performed with Swiss ball on muscle electromyographic amplitude in trained men: A cross-sectional study. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 24(2), 74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2019.09.004 (2020).

Finlay, M. J., Bridge, C. A., Greig, M. & Page, R. M. Upper-body post-activation performance enhancement for athletic performance: A systematic review with meta-analysis and recommendations for future research. Sports Med. 52(4), 847–871. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01598-4 (2022).

Hollerbach, B. S. et al. Muscular strength, power, and endurance adaptations after two different university fitness classes. Sports (Basel) 9(8), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports9080107 (2021).

Knapik, J. The army physical fitness test (APFT): A review of the literature. Mil. Med. 154(6), 326–329 (1989).

Vossen, J. F., Kramer, J. E., Burke, D. G. & Vossen, D. P. Comparison of dynamic push-up training and plyometric push-up training on upper-body power and strength. J. Strength Cond. Res. 14(3), 248–253. https://doi.org/10.1519/00124278-200008000-00002 (2000).

Ubinger, M. E., Prentice, W. E. & Guskiewicz, K. M. Effect of closed kinetic chain training on neuromuscular control in the upper extremity. J. Sport Rehabil. 8(3), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.8.3.184 (1999).

Chuckpaiwong, B. & Harnroongroj, T. Palmar pressure distribution during push-up exercise. Singapore Med. J. 50(7), 702–704 (2009).

Pelka, E. Z., Gadola, C., McLaughlin, D., Slattery, E. & Claytor, R. P. Comparison of the PUSH Band 2.0 and vicon motion capture to measure concentric movement velocity during the barbell back squat and bench press. Sports (Basel) 11(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports11010006 (2022).

Jovanović, M. & Flanagan, E. P. Researched applications of velocity based strength training. J. Australian Strength Cond. 22(2), 58–69 (2014).

Włodarczyk, M., Adamus, P., Zieliński, J. & Kantanista, A. Effects of velocity-based training on strength and power in elite athletes—A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(10), 5257. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105257 (2021).

Balsalobre-Fernández, C., Kuzdub, M., Poveda-Ortiz, P. & Campo-Vecino, J. D. Validity and reliability of the PUSH wearable device to measure movement velocity during the back squat exercise. J. Strength Cond. Res. 30(7), 1968–1974. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001284 (2016).

Orange, S. T. et al. Validity and reliability of a wearable inertial sensor to measure velocity and power in the back squat and bench press. J. Strength Cond. Res. 33(9), 2398–2408. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002574 (2019).

Chou, P. H. et al. Effect of push-up speed on elbow joint loading. J. Med. Bio Eng. 31(3), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.5405/jmbe.772 (2011).

Dhahbi, W., Chaouachi, A., Cochrane, J., Chèze, L. & Chamari, K. Methodological issues associated with the use of force plates when assessing push-ups power. J. Strength Cond. Res. 31(7), e74. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001922 (2017).

Cogley, R. M. et al. Comparison of muscle activation using various hand positions during the push-up exercise. J. Strength Cond. Res. 19(3), 628–633. https://doi.org/10.1519/15094.1 (2005).

Snarr, R. L. & Esco, M. R. Electromyographic comparison of traditional and suspension push-ups. J. Hum. Kinet. 31(39), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2013-0070 (2013).

Zalleg, D. et al. Explosive push-ups: From popular simple exercises to valid tests for upper-body power. J. Strength Cond. Res. 34(10), 2877–2885. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002774 (2020).

Ebben, W. P. et al. Kinetic analysis of several variations of push-ups. J. Strength Cond. Res. 25(10), 2891–2894. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e31820c8587 (2011).

Barbara, B. ACSM’s Complete Guide to Fitness & Health-Human Kinetics 42–45 (American Human Kinetics, 2011).

van den Tillaar, R. & Ball, N. Push-ups are able to predict the bench press 1-RM and constitute an alternative for measuring maximum upper body strength based on load-velocity relationships. J. Hum. Kinet. 21(73), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2019-0133 (2020).

Rozenek, R., Byrne, J. J., Crussemeyer, J. & Garhammer, J. Male-female differences in push-up test performance at various cadences. J. Strength Cond. Res. 36(12), 3324–3329. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000004091 (2022).

Uhl, T. L., Carver, T. J., Mattacola, C. G., Mair, S. D. & Nitz, A. J. Shoulder musculature activationduring upper extremity weight-bearing exercise. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 33(3), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2003.33.3.109 (2003).

McGill, S. M., Cannon, J. & Andersen, J. T. Analysis of pushing exercises: Muscle activity and spine load while contrasting techniques on stable surfaces with a labile suspension strap training system. J. Strength Cond. Res. 28(1), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182a99459 (2014).

Beach, T. A. C., Howarth, S. J. & Callaghan, J. P. Muscular contribution to low-back loading and stiffness during standard and suspended push-ups. Hum. Mov. Sci. 27(3), 457–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2007.12.002 (2008).

Freeman, S., Karpowicz, A., Gray, J. & McGill, S. Quantifying muscle patterns and spine load during various forms of the push-up. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 38(3), 570–577. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000189317.08635.1b (2006).

Borreani, S. et al. Shoulder muscle activation during stable and suspended push-ups at different heights in healthy subjects. Phys. Ther. Sport. 16(3), 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2014.12.004 (2015).

García-Massó, X. et al. Myoelectric activation and kinetics of different plyometric push-up exercises. J. Strength Cond. Res. 25(7), 2040–2047. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e4f7ce (2011).

Gulmez, I. Effects of angle variations in suspension push-up exercise. J. Strength Cond. Res. 31(4), 1017–1023. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001401 (2017).

Giancotti, G. F., Fusco, A., Varalda, C., Capranica, L. & Cortis, C. Biomechanical analysis of suspension training push-up. J. Strength Cond. Res. 32(3), 602–609. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002035 (2018).

Dhahbi, W. et al. Standardizing the quantification of external load across different training modalities: A critical need in sport-science research. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2024-0366 (2024).

Dhahbi, W. et al. 4–6 Repetition maximum (RM) and 1-RM prediction in free-weight bench press and smith machine squat based on body mass in male athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 38(8), 6. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000004803 (2024).

Calatayud, J., Borreani, S., Colado, J. C., Martin, F. & Rogers, M. E. Muscle activity levels in upper-body push exercises with different loads and stability conditions. Phys. Sportsmed. 42(4), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.3810/psm.2014.11.2097 (2014).

Marcolin, G. et al. Selective activation of shoulder, trunk, and arm muscles: A comparative analysis of different push-up variants. J. Athl. Train. 50(11), 1126–1132. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-50.9.09 (2015).

Gouvali, M. K. & Boudolos, K. Dynamic and electromyographical analysis in variants of push-up exercise. J. Strength Cond. Res. 19(1), 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1519/14733.1 (2005).

Moore, L. H., Tankovich, M. J., Riemann, B. L. & Davies, G. J. Kinematic analysis of four plyometric push-up variations. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 5(4), 334–343 (2012).

Lopes Dos Santos, M. et al. Differences and relationships between push-up and sit-up variations among male law enforcement cadets. J. Strength Cond. Res. 37(9), 1865–1869. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000004466 (2023).

Clemons, J. Construct validity of two different methods of scoring and performing push-ups. J. Strength Cond. Res. 33(11), 2971–2980. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002843 (2019).

Payne, N., Gledhill, N., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Jamnik, V. K. & Keir, P. J. Canadian musculoskeletal fitness norms. Can. J. Appl. Physiol. 25(6), 430–442. https://doi.org/10.1139/h00-028 (2000).

Padulo, J. et al. Validity and reliability of a new specific parkour test: Physiological and performance responses. Front. Physiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.01362 (2019).

Turki, O. et al. Warm-up with dynamic stretching: Positive effects on match-measured change of direction performance in young elite volleyball players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2019-0117 (2019).

Fortier, M. D., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Malina, R. M. & Bouchard, C. Seven-year stability of physical activity and musculoskeletal fitness in the Canadian population. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 33(11), 1905–1911. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200111000-00016 (2001).

Marquina Nieto, M., Rivilla-García, J., de la Rubia, A. & Lorenzo-Calvo, J. Assessment of the speed and power of push-ups performed on surfaces with different degrees of instability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(21), 13739. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192113739.PMID:36360619;PMCID:PMC9658261 (2022).

Hinshaw, T. J., Stephenson, M. L., Sha, Z. & Dai, B. Effect of external loading on force and power production during plyometric push-ups. J. Strength Cond. Res. 32(4), 1099–1108. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001953 (2018).

Dhahbi, W. et al. Kinetic analysis of push-up exercises: A systematic review with practical recommendations. Sports Biomech. 21(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2018.1512149 (2022).

Vural, F. et al. Can different variations of suspension exercises provide adequate loads and muscle activations for upper body training?. PLoS ONE 18(9), e0291608. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0291608 (2023).

Alberga, A. S. et al. Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on cardiorespiratory and musculoskeletal fitness in adolescents with obesity: The HEARTY trial. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 41(3), 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2015-0413 (2016).

Tillaar, R. V. D. Comparison of kinematics and muscle activation between push-up and bench press. Sports Med. Int. Open 3(3), E74–E81. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1001-2526 (2019).

Youdas, J. W. et al. Comparison of muscle-activation patterns during the conventional push-up and perfect· pushup™ exercises. J. Strength Cond. Res. 24(12), 3352–3362. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181cc23b0 (2010).

Mier, C. M. et al. Differences between men and women in percentage of body weight supported during push-up exercise. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 7(2), 161–168 (2014).

Suprak, D. N., Dawes, J. & Stephenson, M. D. The effect of position on the percentage of body mass supported during traditional and modified push-up variants. J. Strength Cond. Res. 25(2), 497–503. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181bde2cf (2011).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Sports Science Research Center at Beijing Sport University for providing the necessary facilities and environment that greatly facilitated our research. Furthermore, we acknowledge the collective efforts of all the authors whose contributions have been crucial in bringing this study to fruition.

Funding

This research was supported by the Special Funds for Basic Scientific Research Services of Chinese Central Universities (2024TNJN003) and the Athletic Sports Specific Program of the China Administration of Sports for Persons with Disabilities (2023-JT&014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.H. and W.H. contributed to the design. W.H, and W.H. participated in most of the study steps. Z.H. and W.H. prepared the manuscript. Z.H. and M.R. assisted in designing the study and helped in the, interpretation of the study. All authors have read and approved the content of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Experimental Ethics Committee of Sports Science, Beijing Sport University (approval number: 2022002H). All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, H., Zhai, H., Ma, R. et al. A predictive model for vertical ground reaction force during incline push-ups. Sci Rep 15, 44454 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28012-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28012-7