Abstract

Understanding the implications of dietary consumption and food trade for water resources is essential for sustainable development in water-scarce regions. In this study, we quantified the dietary virtual water use (DVWU) and trade flows associated with food production and consumption across the upstream, midstream, and downstream regions of the Yellow River Basin (YRB), with explicit consideration of urban–rural dietary differences. We then evaluated how virtual water transfers in the food trade affect regional water stress. The results revealed that, in 2020, grain-based diets accounted for 28.32% more DVWU than animal-based diets in the YRB. Upstream residents had the highest per capita DVWU (312.3 m3), primarily due to higher intake of water-intensive foods and feed. Rural diets were dominated by grain-based virtual water (60.64%), whereas urban diets relied more on animal sources (53.43%). The food trade led to a net outflow of 60.7 BCM of virtual water from the YRB, primarily from the downstream area, resulting in a 53.64% overall increase in the water stress index (WSI) across the basin. Although upstream regions experienced a 24% decrease in WSI due to virtual water inflow, downstream areas experienced an 80% increase, highlighting the spatial mismatch between food production and water availability. This study provides evidence-based insights for integrated food–water management and water-efficient food system planning in response to increasing water stress in the YRB and other arid regions of China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The overuse of freshwater resources is increasingly being seen as a critical global risk that threatens both ecological stability and human development. Ensuring sustainable water management has become a core component of the international agenda, as emphasized by the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 61. As the primary sector responsible for food production, the agricultural industry is the largest user of freshwater resources, accounting for approximately 70–85% of global water withdrawals. Animal-based food production generally requires substantially more water than plant-based food production because of the cumulative water requirements of feed crops, animal maintenance, and processing2,3. As economic development and living standards improve, dietary patterns shift toward higher meat and dairy consumption; thus, regional water demand increases, often exceeding sustainable limits, particularly in arid or semi-arid basins. Moreover, when food is produced in water-scarce regions and consumed elsewhere, the externalization of consumption can exacerbate local water depletion. Therefore, the relationship among dietary composition, food trade, and embedded water use must be understood for managing water stress in vulnerable regions.

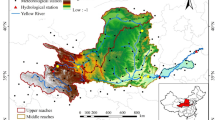

The Yellow River Basin (YRB) is China’s second-largest river basin, spanning an area of 795,000 km2. It originates on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and flows through nine provinces before discharging into the Bohai Sea, forming a distinctive west–east gradient in terms of topography and climate4. The YRB is conventionally divided into three geographical regions: the Upstream Reach, from the source in the Bayan Har Mountains to Hekou Town (located in Togtoh County, Inner Mongolia), is characterized by high elevation and a sparse population; the Midstream Reach, from Hekou Town to Taohuayu (near Zhengzhou, Henan Province), is dominated by the Loess Plateau, with fragile ecosystems and intensive agriculture; and the Downstream Reach, from Taohuayu to the Bohai Sea, is densely populated and economically developed5. This spatial structure results in pronounced variations in the precipitation, runoff, land use, and water demand. The YRB contains 17.7% of China’s water resources and less than 20% of the national per capita average6,7. Over the past five decades, total water use has increased from 17.8 to 39.3 BCM8, with agriculture remaining the dominant sector, accounting for 77% of withdrawals, 91% of which are for irrigation9. Currently, the YRB contributes 38%, 22%, and 30% of wheat, maize, and mutton and milk production, respectively. This imbalance between regional water availability and heavy agricultural burden has intensified water stress within the region.

In addition to growing water demand, the YRB has experienced significant climatic changes. From the 1960s to the 2000s, most areas in the basin experienced declining precipitation. Consequently, annual natural runoff reached a record low of approximately 30.0 BCM in 2002 and has since fluctuated around an average of 57.5 BCM10. Owing to these climatic fluctuations, water availability has exhibited pronounced interannual variability, often coinciding with periods of peak agricultural demand. Population growth, urban expansion, and socioeconomic development are expected to increase industrial and domestic water demand by 50–80% over the next three decades11,12,13, posing new challenges to the region’s already scarce water resources. Within the national strategy for ecological protection and high-quality development in the YRB14, water stress continues to be regarded as the principal constraint and a key bottleneck in achieving sustainable human–environment interactions6,15.

Virtual water is the water embedded in goods and services16,17, and includes blue, green, and gray water. Green water is the water stored in the unsaturated soil layer and precipitation that is eventually transferred to canopy evapotranspiration18. Blue water comprises surface and groundwater. Gray water is the freshwater required for diluting pollutants in receiving water bodies19,20.

Virtual water offers a powerful lens for examining the intricate interplay among agricultural production, food consumption, and water stress21,22. The concept is especially useful for understanding how the food trade redistributes water use and scarcity across regions23,24,25,26,27,28,29. For instance, Xie24 analyzed the temporal dynamics of blue and green water scarcity driven by irrigated croplands in the YRB, and revealed that several areas in the Midstream Reach experienced both blue and green water scarcity, at least at a modest level, for a minimum of 3 months each year, whereas some particularly affected regions, especially in the northern part of the Midstream Reach, faced significant and persistent blue water scarcity throughout the year due to intensive crop production. Regional disparity in grain production and consumption drives virtual water flows via the food trade, helping importing regions to save local water for other critical uses25,26,27. However, such trade may also shift the burden of resource use and environmental impacts from the regions where consumption occurs to those where production takes place3,20,30,31,32,33.

In recent years, a growing body of research has utilized the concept of virtual water to examine how imbalances in household consumption and transformations in dietary patterns contribute to regional and global water stress34,35,36. For instance, Yan2 estimated the virtual water for food consumption in China from the perspectives of urban and rural dietary changes, and found that the per capita virtual water embedded in the diets of urban residents was higher than that of rural residents. Their study suggested that a shift to a balanced diet can reduce pressure on water resources. Consistent with this view, Vanham37,38 emphasized that shifts in dietary patterns, particularly toward more water-intensive foods, will be a major driver of future water stress.

As the YRB spans a vast and diverse geographical region, it exhibits considerable heterogeneity in resource endowments, dietary patterns, demographic characteristics, and agricultural structures across its upper, middle, and lower reaches. Previous studies investigated the impact of agricultural production on water resources in the YRB through a virtual water lens. These efforts primarily focused on assessing the water footprint of agricultural products5,23,39, flow of virtual water embedded in agricultural trade40,41,42,43,44, and resulting pressure on regional water resources45,46.

Although previous studies examined agricultural production and virtual water flows, relatively few addressed how consumption-side heterogeneity—particularly dietary differences between rural and urban populations—shapes virtual water dynamics and regional water stress. This study contributes to the literature in two significant ways: (1) by incorporating consumption-side drivers, including dietary structure and rural–urban disparities, into the analysis of virtual water flows; and (2) by investigating the disparity between food production and consumption as a key mechanism driving intra-basin virtual water transfer and influencing spatial patterns of water stress. These perspectives remain underexplored in existing research and offer new insights into food–water connections at sub-basin scales. To this end, we address the following research questions: (1) How do dietary differences across sub-regions of the YRB influence dietary virtual water use (DVWU)? (2) To what extent do rural–urban dietary disparities contribute to the spatial variation in DVWU? Finally, (3) how does the mismatch between regional food production and consumption drive the virtual water trade (VWT), and in turn, exacerbate or alleviate water stress across the basin? To answer these questions, we first estimated the virtual water content (VWC) of grain- and animal-based food products, then analyzed spatial and demographic patterns in DVWU, and finally evaluated the impacts of VWT—arising from production–consumption imbalances—on regional water stress. This study advances the understanding of food–water interactions at multiple spatial scales and provides a scientific foundation for the formulation of region-specific policies for sustainable food and water management.

Methodologies and data

Estimation of VWC of food

VWC refers to the volume of water consumed in the production of a given commodity at its place of origin per unit mass, typically expressed in cubic meters per ton (m3/ton). VWC is measured via two prominent approaches: the environmentally extended input–output approach (EEIO)47,48 and the process-based method49. The EEIO approach is more appropriate when the objective is to capture broader supply-chain effects, such as embedded energy inputs and water use in upstream production processes (where Scope 2 and 3 impacts are likely to dominate), whereas the process-based approach offers higher spatial and sectoral resolution, rendering it more appropriate for analyzing dietary water footprints and intra-regional VWT within specific regions.

As our study focuses on direct agricultural production within the YRB —primarily involving Scope 1 water use impacts—we estimated crop-specific VWCs via the process-based approach. This approach relies on detailed crop water use and production data, enabling a more accurate assessment of regional and commodity-level heterogeneity in water consumption. It has been widely employed for examining agricultural water use in previous studies, particularly in studies seeking to quantify food-related VWC at fine spatial scales39,50,51.

VWC of crops

The specific calculation formula for VWC of crops is as follows50,51:

where \(\:{VWC}_{i,c}\) indicates the VWC of crop c (including wheat, maize, rice, potato, and soybean) in region i (different provinces in the YRB; L/kg). \(\:{VWC}_{i,c}^{bl}\)and \(\:{VWC}_{i,c}^{gr}\) indicate the blue and green VWC of crop c in region i, respectively (L/kg); \(\:{I}_{i,c}\) and \(\:{Peff}_{i,c}\) represent irrigation water and effective precipitation (portion of rainfall available for crop use after accounting for losses) during the growing season52 for crop c in region i, respectively (mm). \(\:{Y}_{i,c}\) denotes grain yield per unit area (kg/ha). The factor 104 converts water depth (in mm) into water volume per unit area of land (in L/ha); “lgp” is the length of the crop growth period (in days). The VWC of wheat and rice in the YRB was calculated to estimate the virtual water consumed directly via residents’ diets. Additionally, the VWCs of maize, potato, and soybean were calculated, as these crops serve as ingredients for animal feed, allowing us to estimate the VWC of animal-based products.

VWC of animal-based food

The VWC of animal-based foods is generally high, as it includes not only the water used for feed crop production, but also additional water for animal maintenance and product processing. In this study, we focused exclusively on the virtual water associated with feed crop production, assuming that other components (e.g., drinking and service water) are largely returned to the water system. In addition, we did not account for gray water or polluted return flows (e.g., from agricultural systems), as it focused exclusively on quantifying the volumes of water used or retained within agricultural production processes, rather than addressing water quality issues or environmental pollution.

The VWC of animal-based food was determined based on the feed/meat ratio, composition of feed grains, and VWC of each feed grain component.

where \(\:{VWC}_{i,k}\), \(\:{VWC}_{i,k}^{bl}\), and \(\:{VWC}_{i,k}^{gr}\)represent the total VWC, blue VWC, and green VWC of animal-based food k (including pork, beef and mutton, milk, eggs, and poultry) in region i (L/kg); Rati, k indicates feed–meat ratio of animal-based food k in region i (dimensionless) (Table T1 of the Supporting Information (SI)). According to Xin53, 70%, 10%, 15%, 30%, and 40% of the output from maize, rice, wheat, tuber crops, and soybeans, respectively, is used as feed grain. Consequently, the estimated fractions of different grain-based products (\(\:{F}_{c}\)) in the feed were 64.06%, 7.23%, 6.21%, 3.1%, and 19.45% for maize, rice, wheat, potatoes, and soybeans, respectively.

Estimation of DVWU and VWT

DVWU refers to the volume of virtual water embedded in crop- and animal-based foods consumed by residents. This reflects the indirect use of water resources associated with dietary intake, rather than total food production or trade. DVWU was calculated by multiplying the amount of each food type consumed per capita by its corresponding VWC, considering variations in dietary patterns between the urban and rural populations. This approach enabled the assessment of water use specifically linked to human consumption behavior across different regions. In this study, DVWU was calculated separately for each food category and region based on VWC and dietary consumption quantities:

where \(\:{DVWU}_{i}\) represents the DVWU of residents in region i (m3/person); \(\:{DVWU}_{i,c}\) and \(\:{DVWU}_{i,k}\) represent the DVWU of crop- and animal-based food types, respectively (m3/person); and \(\:{Q}_{i,c}\)and \(\:{Q}_{i,k}\) are the quantities of crop- and animal-based food consumed by residents in region i, respectively (kg/person; Table 1).

VWT reflects the net inflow or outflow of virtual water associated with the difference between local food production and consumption. In this study, VWT was not derived from reported trade statistics, which are often incomplete or unavailable at the basin or sub-basin scale and may not align with YRB boundaries. Instead, VWT was estimated indirectly from the balance between local food production and consumption (assuming that all surplus is traded and no wastage occurs). This supply–demand approach enables us to consistently capture implied food flows and their implications for water use across regions, while avoiding the additional uncertainties and spatial inconsistencies associated with reported trade data. Furthermore, all VWT estimations were based on the VWC of the production region, even when insufficient local production is assumed to be compensated by inflows from outside the YRB. This ensures that the analysis directly reflects the influence of local production systems on regional water stress. The total VWT in region i is given by:

where \(\:{VWT}_{i}\) denotes the VWT in region i (m3). A positive value indicates net virtual water outflow (i.e., the region is a net exporter of virtual water), while a negative value indicates net virtual water inflow (i.e., the region is a net importer); \(\:{O}_{i,c}\)and \(\:{O}_{i,k}\)represent the output of grain-based food c and animal-based food k in region i, respectively (ton); \(\:{Pop}_{i}\) is the population in region i;\(\:{\:Q}_{i,c}\times\:{Pop}_{i}\:\)(or\(\:\:{Q}_{i,k}\times\:{Pop}_{i}\)) represents the total consumption of grain-based (or animal-based) products in region i. In practice, this value is calculated as the sum of per capita consumption by urban residents multiplied by the urban population and per capita consumption by rural residents multiplied by the rural population.

In addition to total VWT, green and blue components were separately estimated as green VWT (\(\:{VWT}_{i}^{gr}\)) and blue VWT (\(\:{VWT}_{i}^{bl}\)), respectively. These were calculated using the same formulation as Eq. (10), but with the corresponding VWC values substituted for \(\:{VWC}_{i,c}^{gr}\) (\(\:{VWC}_{i,k}^{gr}\)) and \(\:{VWC}_{i,c}^{bl}\) (\(\:{VWC}_{i,k}^{bl}\)), respectively. This decomposition allows for a more nuanced understanding of the water sources embedded in virtual water flows across regions.

Assessment of dietary impacts on water stress

The possible impact of VWT embedded in food on water stress was detected as20:

where \(\:{{\Delta\:}\text{W}\text{S}\text{I}}_{i}\) is the effect of food trade on water stress in region i, \(\:{WSI}_{i}^{cur}\) is the water stress index (WSI) under current conditions, and \(\:{WSI}_{i}^{nt}\) is the WSI under hypothetical conditions without VWT embedded in food. \(\:{WU}_{i}\) refers to water use (m3/yr) in region i and \(\:T{WA}_{i}\) represents the total available water resources in region i, including surface water and groundwater (m3). Only blue virtual water trade (\(\:{VWT}_{i}^{bl}\)) was considered in estimating the impact of food trade on water stress, as data are available exclusively for blue water resources.

Data

The VWC of crops (\(\:{VWC}_{(i,c)}\)) in this study was estimated based on the five-arc-minute gridded water footprint dataset published by Zhuo42. This dataset was generated using the AquaCrop model, which simulates soil water dynamics by tracking water inflow and outflow in the root zone. Specifically, it calculates daily blue and green water evapotranspiration, as well as crop yield during the crop growth period. For more detailed information on the datasets, please refer to Wang54 and Zhuo42. To reduce the influence of interannual rainfall variability on blue and green water estimates, the VWC was calculated as the average value for the period of 2000–2014. In this study, we combined food production and consumption data, as well as population data for 2020, with the long-term average dataset, as more recent basin-wide water-use data are not yet available. This approach provided consistency and ensured that the assessment results for 2020 were representative of typical hydrological conditions.

The feed–meat ratio reflects the amount of feed required to produce one unit of animal product k in region i, and serves as a key parameter in estimating the VWC of animal-based products. The feed–meat ratios considered in this study were sourced from peer-reviewed literature and account for regional variations across different types of animal-based products. Detailed values for each region and product category are provided in Table T1 of the SI.

Table 1 presents the annual per capita consumption (kg/person) of key food categories, including staple foods (wheat and rice) and animal-based products (pork, beef, mutton, eggs, and milk) for both urban and rural populations. These data were primarily derived from the 2021 Statistical Yearbooks of the relevant provinces, such as the Shandong55, Inner Mongolia56, Shaanxi57, Shanxi58, Ningxia59, Gansu60, Henan61, and Ningxia59 Statistical Yearbooks, as well as supplementary data from selected municipal statistical yearbooks. The 2021 Statistical Yearbooks report records for 2020, which is the assessment year considered in this study. This information serves as a basis for estimating region-specific food consumption volumes, which, when combined with VWC, are used to calculate the DVWU associated with dietary patterns.

In addition to the data mentioned above, we also utilized population statistics for 2020 at the prefecture level across the YRB, including both urban and rural population figures. Data on the production of grain-based (wheat, maize, and rice) and animal-based foods (pork, beef, mutton, eggs, and milk) were collected from each region, obtained from the 2021 statistical yearbooks of the respective provinces55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62. Additionally, information on water resource endowments and use was sourced from provincial water resource bulletins (Shui Ziyuan Gongbao) published by the corresponding provincial water authorities, including the Water Resources Department of Shandong Province62, Department of Water Resources of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region63, Gansu Provincial Department of Water Resources64, Qinghai Water Conservancy Information Network65, Ningxia Water Conservancy66, Shaanxi Provincial Department of Water Resources67, and Shanxi Provincial Department of Water Resources68. These comprehensive datasets provide a foundation for estimating food supply, consumption, virtual water flows, and regional water stress levels.

Results

Virtual water embedded in food consumption by residents in the YRB

VWC of food in the YRB

To better understand the underlying drivers of regional differences in DVWU, this section examines the VWC of major food items in the YRB, including grain-based products, livestock feed, and animal products. The following subsections provide a detailed breakdown of VWC estimates by food category and region (Fig. 1). For improved readability in the descriptive text, we used simplified notations such as VWC, VWCbl (blue water), and VWCgr (green water), omitting the subscripts i, c, and k as defined in Eqs. (1)–(6). Instead, the corresponding region and food type are clearly stated in the narrative context.

-

i.

VWC of grain-based products

The VWCbl for maize, rice, and wheat were 272, 435, and 753 L/kg, comprising 26%, 48%, and 53% of the total VWC in the YRB, respectively. The VWCs of potatoes and soybeans, the key feed ingredients, were 317 and 3,491 L/kg, respectively, with VWCbl contributing 5% and 23%, respectively.

Regionally, the upstream basin presented crops with high VWCs. For example, maize in the upstream region had a VWC of 1,245 L/kg (31% VWCbl), compared with 765 L/kg (20% VWCbl) and 792 L/kg (19% VWCbl) in the midstream and downstream regions. Similarly, the VWC of wheat in the upstream region reached 1,584 L/kg (53% VWCbl), whereas those in the midstream and downstream regions were 1,377 L/kg (45% VWCbl) and 1,028 L/kg (53% VWCbl), respectively.

-

ii.

VWC of feed products.

Based on a standard feed composition as described in Sect. 2.1.2, the average VWC of the feed was calculated as 1,514 L/kg. Regionally, feed VWC was the highest upstream (1,663 L/kg, 31% VWCbl), followed by midstream (1,335 L/kg, 21%) and downstream (1,151 L/kg, 26%). These differences reflect the local crop production conditions and water availability.

-

iii.

VWC of animal-based products.

The VWC of pork, beef and mutton, poultry, eggs, and milk in the YRB were 4,217, 3,245, 3,194, 2,864, and 626 L/kg, respectively. On average, VWCbl and VWCgr accounted for 27% and 73% of the total VWC, respectively.

The upstream basin consistently exhibited higher VWCs than the other regions. For example, VWCbl for pork in the upstream reached 1,381 L/kg, compared with 833 and 809 L/kg in the midstream and downstream regions. VWCgr also followed this trend, with that for pork in the upstream region being 3,092 L/kg, compared with 3,099 (midstream) and 2,299 L/kg (downstream).

At the provincial level (a detailed list of subregional administrative divisions is provided in Table T4, SI), Qinghai (upstream) exhibited the highest VWC for pork (VWCbl: 1,993 L/kg; VWCgr: 5,330 L/kg), indicating heavy reliance on green water. Inner Mongolia (upstream) and Shanxi (midstream) also exhibited high VWCbl for pork (1,500 and 995 L/kg, respectively). In comparison, Henan (midstream) and Shandong (downstream) exhibited lower and more balanced levels (838 and 780 L/kg, respectively). For dairy, Shanxi reported VWCbl and VWCgr of 133 and 485 L/kg, respectively, whereas Inner Mongolia recorded values of 231 and 310 L/kg, respectively. These results highlight the significant spatial variability in water requirements for animal-based production, emphasizing the need for region-specific water management strategies.

Virtual water content (VWC, L/kg) of different food products. Subplots (a) and (b) show the blue and green VWC (VWCbl and VWCgr) of food products by subregion (upstream, midstream, downstream, and basin-wide average), whereas subplots (c) and (d) present the corresponding values at the provincial level. Subregions are grouped according to their location within the YRB. Detailed data are available in Tables T2–T3, and a list of subregional administrative divisions is provided in Table T4, SI.

By comparing the magnitude and composition of VWCs across the upstream, midstream, and downstream regions, clear spatial patterns of dietary water use were observed. These spatial patterns were shaped by agricultural practices and environmental conditions, which jointly influenced dietary water use across the YRB.

DVWU of diets in the YRB

Here, we use the terms “grain-based DVWU” and “animal-based DVWU” to refer to DVWU associated with crop- and animal-based foods, respectively. These expressions correspond directly to the formal notations DVWUi, c and DVWUi, k defined in Eqs. (7)–(9).

Regarding the per capita DVWU, grain-based food accounted for the largest share across all subregions. Rural residents consistently exhibited higher grain-based DVWU than their urban counterparts (Fig. 2). The highest value was observed in rural residents of the upstream region (93.59 m3/person), followed by those in the midstream (80.68 m3/person) and downstream (74.16 m3/person) regions. Urban residents also showed a decreasing trend from upstream (68.04 m3/person) to downstream (55.31 m3/person). Among grain types, wheat dominated the grain-based DVWU, especially in the midstream region, where both urban and rural consumption were significantly higher (55.25 and 72.41 m3/person, respectively) than that of rice.

The animal-based DVWU of urban residents in the upstream, midstream, and downstream regions was higher than that of their rural counterparts, with per capita DVWU of 53.24, 30.25, and 30.55 m3/person, respectively, compared with 46.1, 18.79, and 25.34 m3/person for rural residents.

Overall, rural residents in the upstream and midstream regions had the highest total DVWU, primarily due to their higher consumption of grain-based food. Conversely, urban residents exhibited a high animal-based DVWU, likely because of their dietary preferences and greater affordability. The upstream region had the highest combined DVWU per capita.

The DVWU of grains, dominated by wheat and rice, for residents in the YRB was 28.23 BCM (Fig. 3). This consumption was nearly evenly split between green (13.7 BCM, or 48.55%) and blue (14.53 BCM, or 51.45%) virtual water. This is likely due to the dominant dietary habits in northern China, which heavily emphasize wheat-based foods. In fact, the virtual water consumption from wheat alone constitutes the majority (86.42%) of the total virtual water from grain consumption.

The animal-based DVWU in the YRB amounted to 22 BCM, with pork, eggs, beef and mutton, poultry, and milk contributing 36.12%, 29.32%, 14.59%, 13.19%, and 6.77%, respectively. Green and blue virtual water embedded in feed for producing animal-based food were 16.3 and 5.7 BCM, representing 74.07% and 25.03% of the total DVWU.

The residents in the YRB consumed a total of 50.22 BCM of virtual water in their diet, which comprised 30 and 20.22 BCM of green and blue virtual water, respectively. In terms of overall DVWU, grain-based DVWU comprised 56.21%, whereas animal-based DVWU contributed approximately 43.79%. Furthermore, when considering the consumption of blue virtual water, grain-based foods accounted for 71.8%, whereas animal-based foods constituted the remaining 28.2%.

Dietary virtual water use (DVWU) of food in the YRB. The map shows total DVWU (BCM), with the share from animal-based products (ratio) indicated by circle size and color—larger, darker circles indicate a higher ratio. See Table T4 of the Supporting Information for city names. Map created using ArcGIS 10.8.169.

The spatial distribution of DVWU across the upstream, midstream, and downstream regions of the YRB revealed substantial heterogeneity in both volume and composition, as shown in Fig. 4. The midstream region consistently recorded the highest values, with 14.49 BCM for green DVWU and 8.50 BCM for blue DVWU, contributing to a total DVWU of 23.00 BCM (46%). The upstream region followed, with 7.84 BCM for green DVWU and 6.26 BCM for blue DVWU, totaling 14.10 BCM, where the downstream region showed the lowest green (7.67 BCM) and blue (5.47 BCM) DVWU values, with a total of 13.13 BCM. These results highlight that the midstream region of the basin, owing to its intensive agriculture and reliance on irrigation, exerts the most significant pressure on regional water resources.

Within this regional framework, wheat consistently emerged as the most water-intensive food type, contributing 12.11 (53%), 5.66 (40%), and 6.48 (49%) BCM in the midstream, upstream, and downstream regions, respectively. In contrast, animal-based foods exhibited distinct spatial patterns. The upstream region was characterized by high contributions from pork (2.29 BCM) and beef and mutton (2.03 BCM), reflecting its strong livestock orientation, whereas the downstream region was dominated by eggs (2.33 BCM) and poultry (1.02 BCM). The midstream region showed a more balanced distribution, with pork (3.68 BCM) and eggs (3.00 BCM) as the leading contributors. These findings highlight that spatial heterogeneity in DVWU across the YRB arises from complex interplay between supply-side factors, such as cropping systems and livestock orientation, and demand-side drivers, including population distribution, urban–rural structure, and region-specific dietary preferences.

Composition and quantity of dietary virtual water use (DVWU) across the upstream, midstream, and downstream regions of the YRB in 2020. Subplots (a–c) show the proportions of green DVWU (DVWU_g); (d–f) represent blue DVWU (DVWU_b); and (g–i) depict total DVWU (DVWU_tot). Each pie chart illustrates the percentage contribution of seven major food types (wheat, rice, pork, beef and mutton, poultry, milk, and eggs) to regional DVWU. The largest segment in each chart is annotated with its absolute value (unit: BCM). The figures were created by the authors using ArcGIS 10.8.169 in combination with Microsoft PowerPoint 201070.

VWT derived from food supply–demand imbalance

Here, VWT is defined as the virtual water inflow or outflow of a region (YRB as a whole or its upstream, midstream, and downstream subregions), estimated from the balance between local food production and consumption Eq. (10). The analysis does not track the specific destinations of outflows or sources of inflows; instead, it focuses on the implications of these net flows for regional water stress.

In 2020, the YRB recorded a VWT outflow of 32.56 BCM through wheat (including 16.42 BCM for blue virtual water), and a VWT inflow of 2.89 BCM through rice (Fig. 5a, d). In total, grain trade (wheat and rice) resulted in a net VWT outflow of 29.68 BCM (including 14.95 BCM for blue VWT). For animal-based food, the total VWT outflow was 31.1 BCM, including 22.6 and 8.5 BCM for green and blue VWT, respectively (Fig. 5b, d). Among these, the VWT outflow associated with eggs accounted for 32.98% of the total, followed by pork at 25.42%. Poultry meat, dairy products, and beef and mutton accounted for 14.42%, 14.21%, and 12.96% of the total VWT outflow, respectively.

Virtual water trade (VWT) embedded in food trade for the Yellow River Basin (YRB) as a whole and for its upstream, midstream, and downstream sub-basins in 2020. (a) VWT embedded in grain-based food trade; (b) VWT embedded in animal-based food trade; (c) total VWT embedded in all food trade (grain- and animal-based products combined); (d) net VWT of the upstream, midstream, and downstream sub-basins, along with the contributions of different food categories. Positive values indicate net virtual water outflows, while negative values represent net inflows. Unit: BCM. A full list of administrative city names is provided in Table T4 in the SI. The figures were created by the authors using ArcGIS 10.8.169 in combination with Microsoft PowerPoint 201070.

Overall, the YRB reported a VWT outflow of 60.7 BCM from food trade (including grain-based and animal-based products) in 2020 (Fig. 5c), with grain- and animal-based food trade accounting for 48.88% and 51.12%, respectively. The net blue VWT outflow was 23.4 BCM, primarily driven by grain-based food trade (63.85%). The net green VWT outflow was 37.3 BCM, which was mainly attributed to animal-based food trade (60.52%).

In the upstream basin, the surplus of beef, mutton, and dairy products resulted in a VWT outflow of 5.43 BCM for virtual water. In contrast, other food products experienced a virtual water deficit, corresponding to a VWT inflow of 6.32 BCM (Fig. 5d). As a result, the upstream basin showed a net VWT inflow of 0.89 BCM. For blue virtual water, the upstream basin demonstrated a net VWT inflow of 1.22 BCM, predominantly due to grain-based food shortage (81.82% of the total). Conversely, green virtual water exhibited a net VWT outflow of 0.32 BCM, primarily driven by beef, mutton, and dairy products. In the midstream basin, excluding rice, other food products exhibited a surplus equivalent to a VWT outflow of 8.57 BCM, with wheat being the primary contributor, at 43.75%. Consequently, the region recorded a net VWT outflow of 7.04 BCM, comprising 5.01 and 2.02 BCM for green and blue virtual water, respectively. In the downstream basin, food production significantly exceeded local demand, resulting in a VWT outflow of 54.57 BCM to other regions. Wheat was the primary contributor, accounting for 58.91%, followed by eggs (15.86%) and pork (11.97%). Of the 22.61 BCM for blue VWT outflow, wheat, eggs, and pork accounted for 74.17%, 7.52%, and 9.97%, respectively.

In summary, VWT outflows from the YRB were predominantly driven by surpluses of wheat, eggs, pork, and poultry in the downstream regions. Conversely, VWT inflows were primarily associated with deficits in wheat, rice, and poultry production in the upstream regions.

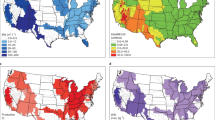

Impact of VWT on water stress in the YRB

The overall water stress level in the upstream basin was low (WSI = 0.18); however, significant spatial variation existed, with some areas experiencing high water stress (Fig. 6a). Regions with WSI > 1 were primarily located in the Inner Mongolia (Bayannur, Baotou, and Wuhai), Ningxia (Yinchuan, Wuzhong, Shizuishan, and Zhongwei), and Gansu (Baiyin and Lanzhou) Provinces. Among these, water stress in Yinchuan, Wuhai, Lanzhou, and Baotou was partially alleviated by the food trade. However, in other areas, virtual water outflows resulting from the food trade exacerbated water stress.

In the midstream basin, the overall water stress was moderate, with a WSI of 0.37. A few areas, including Yuncheng and Zhengzhou, had a WSI greater than 1, indicating high water stress, whereas most areas had a WSI below 1, with the majority of cities reporting WSI values below 0.5. VWT alleviated water stress in some areas of the Shanxi (Taiyuan, Jincheng, and Lvliang) and Shaanxi (Xi’an, Yulin, Tongchuan, and Yan’an) Provinces within the YRB. However, this trade also increased water stress in other areas.

In the downstream region, the overall water stress was notably high, with a WSI of 0.67. This indicated a significant pressure on water resources. The majority of areas in this region had a WSI greater than 0.5, indicating moderate to severe water stress. In particular, nearly half of the region experienced WSI values exceeding 1, highlighting extreme water stress. These high-stress areas were predominantly located in Henan Province, including cities such as Xinxiang, Anyang, Puyang, and Hebi, as well as in Shandong Province, including cities such as Dongying, Binzhou, and Dezhou. These regions face substantial challenges in managing their water resources owing to high demand and limited availability, which exacerbate overall water stress.

Water stress index (WSI) distribution and impact of virtual water trade (VWT) in the Yellow River Basin (YRB) in 2020. (a) Spatial distribution of baseline WSI under current food production and consumption conditions; (b) changes in WSI induced by VWT embedded in food flows. Positive values in panel (b) represent an increase in local water stress due to net virtual water outflows, whereas negative values indicate a reduction in water stress as a result of net virtual water inflows. The full list of administrative city names can be found in Table T4 of the SI. The figures were created by the authors using ArcGIS 10.8.169.

The analysis of the VWT’s impacts on water stress within the YRB revealed a complex interplay of effects across different regions (Fig. 6b). In the upstream basin, cities such as Wuhai and Lanzhou exhibited significant reductions in water stress. In contrast, Bayanzhuoer and Haibeizangzu exhibited moderate increases, leading to an overall net decrease of 24% in water stress. In the midstream basin, substantial reductions in water stress were observed in cities such as Taiyuan, Lvliang, Xi’an, and Yan’an, whereas cities in the Henan and Shanxi Provinces, such as Yuncheng, Xuchang, Jiaozuo, Weinan, and Xianyang, exhibited increases in water stress due to virtual water output, resulting in an overall increase of 19.19%. Conversely, the downstream basin predominantly exhibited increased water stress, with notable increases in cities such as Puyang and Shanqiu, culminating in a significant net increase of 80% in water stress in this region.

When considering the entire basin, the data indicate that the VWT led to an overall increase in water stress of 53.64%, with the downstream region contributing the most to this trend. This suggests that, although the VWT can play a role in managing water resources, it may also exacerbate water stress if not carefully managed, particularly in downstream areas.

Discussion

Linking VWC and dietary patterns to water stress dynamics

The spatial distribution of VWC revealed a clear upstream–downstream gradient across the YRB. Grain-based products, especially wheat and maize, exhibited higher total VWC in the upstream region, whereas the midstream and downstream basins relied more heavily on blue water due to irrigation. Animal-based products also showed the highest water intensity upstream, primarily driven by green water embedded in feed. These patterns indicate that the upstream region faces a greater virtual water burden per unit of food produced, whereas the downstream region faces higher pressure on blue water resources.

From a water stress perspective, adjusting cropping structures based on VWCbl and VWCgr is crucial for enhancing regional water sustainability. According to our results, wheat exhibited consistently high VWCbl values—841, 616, and 544 L/kg in the upstream, midstream, and downstream regions, respectively—posing a considerable burden on irrigation water, particularly in water-scarce downstream areas. In contrast, crops such as potatoes and maize exhibited much lower blue water requirements and higher green water dependence. For example, potatoes exhibited minimal VWCbl (9–21 L/kg across the basin) and moderate VWCgr; thus, they are ideal for rainfed agriculture with low irrigation demand. Maize also exhibited favorable water-use profiles in the midstream and downstream regions, with VWCbl values as low as 156 and 147 L/kg, respectively. These findings suggest that partial substitution of irrigated wheat with potatoes or maize could substantially reduce blue water consumption without compromising food security. Similar strategies have been implemented in water-stressed areas of northern China. For example, in the severely overexploited groundwater funnel region of Heilonggang, located in the northern part of the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, it is recommended to replace water-intensive winter wheat with spring maize, potatoes, and drought-tolerant coarse grains and legumes71. By shifting toward crops that rely primarily on green water, this approach significantly reduced blue water withdrawals, particularly that of groundwater used for irrigation.

Although animal-based foods generally have higher total VWC than grain-based foods, the effects of dietary substitution on water stress are spatially heterogeneous. In the upstream region, animal products such as pork and beef exhibit high VWC values (4,473 and 3,800 L/kg), but are largely supported by green water through feed production. Dietary shifts toward grain-based foods, such as wheat, which are typically produced in midstream and downstream regions, may decrease the total VWC but shift water demand toward blue water sources. Thus, dietary shifts that appear water-saving at the basin scale may exacerbate regional water stress if sourcing is not carefully considered. To avoid such trade-offs, substitutions could prioritize locally grown, green-water-reliant crops—such as potatoes and coarse grains—instead of increasing reliance on irrigated cereals from lower basin regions. This approach supports both water conservation and spatial equity in food–water planning.

Moreover, promoting regionally adapted dietary patterns—such as Mediterranean-like diets with increased legume, vegetable, and coarse grain consumption—can further reduce DVWU while improving overall nutrition. Simultaneously, addressing production inefficiencies—particularly by improving crop yields and reducing irrigation losses—is critical for enhancing water productivity. In this way, the same quantity of food can be produced with lower water input, thereby alleviating water stress across the basin.

Rethinking VWT for sustainable food–water management

In the current VWT configuration of the YRB, pronounced spatial disparities reflect an implicit functional division among subregions. Although the upstream region exhibited relatively low aggregate water stress (WSI = 0.18), its biophysical and agronomic constraints—characterized by low temperatures, limited precipitation, fragile soils, and fragmented arable land—limit its capacity to sustain large-scale cultivation of blue-water-intensive crops, such as wheat72,73. A further dietary shift toward grain-based staples in this region would likely necessitate increased virtual imports of cereals from the midstream and downstream areas, inadvertently intensifying blue water extraction in zones already experiencing severe scarcity (downstream WSI = 0.67; nearly half of the region with WSI > 1). This spatial mismatch between consumption patterns and production suitability underscores the need to align VWT pathways with regional water constraints.

Conversely, the upstream region exhibited comparative advantages in supplying animal-based products. In 2020, surplus beef, mutton, and dairy production from this region generated a VWT outflow of 5.43 BCM, with approximately 62% derived from green water sources, predominantly through feed crops that rely on green water (e.g., rain-fed maize and soybeans), rather than irrigation-intensive feed inputs. Strategic support for expanding such rainfed livestock systems in the upstream region—where green water resources are more abundant and underutilized—could offset the production burden currently placed on water-stressed downstream regions. By decreasing the need for local blue-water-intensive animal farming in the lower basin, this upstream-to-downstream VWT flow would enhance the overall water-use efficiency while preserving regional food supply.

This resource-matched and water-footprint-sensitive reconfiguration of interregional trade presents a promising pathway toward integrated water–food–economic planning. Future basin-level strategies should reinforce agricultural transitions centered on green-water-dominant systems and promote institutional mechanisms for interregional coordination of VWT. Such a framework can facilitate more equitable and hydrologically rational redistribution of water-intensive production, contributing to the simultaneous goals of ecological sustainability, food security, and balanced regional development in the YRB.

Limitations and suggestions for further research

This study provides a static assessment of the impact of current dietary patterns on DVWU, VWT, and VWS across the YRB. However, several limitations should be acknowledged, which also indicate opportunities for future research.

First, the VWC values were derived from long-term averages (2000–2014) to minimize interannual rainfall variability and enhance cross-regional comparability. Although this approach ensures spatial robustness, it may not fully reflect recent advances in irrigation efficiency or climate-induced changes. Nevertheless, our key findings remain valid, as VWT and VWS patterns are primarily driven by structural mismatches between local food production and consumption. Future studies could incorporate more temporally dynamic VWC estimates, such as those from EPIC, PEPIC, or satellite-based evapotranspiration estimates, to better reflect evolving water-use conditions.

Second, this study focuses on dietary patterns in 2020, without evaluating alternative dietary scenarios. Future work should consider counterfactual assessments based on nutritional guidelines or sustainability-oriented diets—such as WHO recommendations, China’s National Food and Nutrition Development Guidelines (2025–2030), or the Mediterranean diet—to inform policy on water-smart and health-promoting diets.

Third, we did not examine the long-term dynamics of dietary transitions. As China has experienced significant shifts from grain-based to more animal-based diets over the past few decades, it is essential to assess how such changes have historically influenced DVWU, VWT, and WSI over time.

Addressing these limitations will contribute to more adaptive, integrated strategies for managing food and water systems under complex socioeconomic and environmental challenges.

Conclusions

This study provided a comprehensive analysis of VWC, DVWU, and VWT linked to food production, consumption, and trade across the YRB, highlighting the implications of dietary patterns and regional disparities on water stress.

Food consumption in the YRB exerts considerable pressure on local water resources, with significant spatial and demographic disparities. Grain-based foods, which are predominantly reliant on blue water, consumed 28% more DVWU than animal-based foods, which are largely supported by green water. Wheat alone accounted for the majority of grain-related DVWU. Among animal-based products, pork and eggs were the principal contributors. Per capita DVWU was highest in upstream regions (312 m3), primarily due to feed-intensive, animal-based diets. Urban and rural dietary patterns also diverged significantly, reflecting different pressures on water resources.

In 2020, the YRB recorded a total food-related VWT of 60.7 BCM. This trade redistributed water stress across the basin—relieving pressure upstream (− 24%) but exacerbating it midstream (+ 19%) and downstream (+ 80%), resulting in a 53.64% net increase in basin-wide stress compared with a no-trade scenario.

These findings underscore the importance of incorporating virtual water dynamics into regional water and food strategies. Addressing spatial mismatches between dietary demand and water availability—through crop substitution, livestock system redesign, and more regionally appropriate food trade—will be critical for promoting sustainable water use in the YRB and similar arid agricultural basins.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

References

Gleeson, T. et al. The water planetary boundary: interrogation and revision. One Earth. 2 (3), 223–234 (2020).

Yan, D. et al. Arable land and water footprints for food consumption in china: from the perspective of urban and rural dietary change. Sci. Total Environ. 838, 155749 (2022).

Mekonnen, M. & Hoekstra, A. Blue water footprint linked to National consumption and international trade is unsustainable. Nat. Food. 1, 792–800 (2020).

Lu, F. et al. Spatiotemporal characteristics of ecological resilience and its influencing factors in the yellow river basin of China. Sci. Rep. 14, 16988 (2024).

Yin, J., Lu, Y. & Ou, Z. Regional agricultural water footprint and crop water consumption study in yellow river Basin, China. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 17, 5539–5559 (2019).

Wang, H. & Zhao, Y. Preliminary study on Harnessing strategies for yellow river in the new period. J. Hydraul. Eng. 50 (11), 1291–1298 (2019). (in Chinese).

Peng, J. The generating mechanism, value embodiment and path reconstruction of the water-energy-food nexus in the yellow river basin. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 43 (8), 76–81 (2021). (in Chinese).

Liu, C. & Zhang, S. Drying up of the yellow river: its impacts and countermeasures. Mitig Adapt. Strateg Glob Chang. 7, 203–214 (2002).

YRCC (Yellow River Conservancy Commission). Comprehensive Planning of the Yellow River Basin for 2012–2030 (Yellow River Conservancy Commission, 2011).

YRCC (Yellow River Conservancy Commission). Comprehensive Planning of the Yellow River Basin for 2012–2030 (Yellow River Conservancy Commission, 2013).

He, C. et al. Future global urban water scarcity and potential solutions. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 4667 (2021).

Garrick, D. et al. Rural water for thirsty cities: a systematic review of water reallocation from rural to urban regions. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 043003 (2019).

Flörke, M., Schneider, C. & McDonald, R. Water competition between cities and agriculture driven by climate change and urban growth. Nat. Sustain. 1, 51–58 (2018).

Xi, J. Speech at the symposium on ecological protection and High-Quality development of the yellow river basin. Qiushi 20, 4–11 (2019). (in Chinese).

Jia, S. & Liang, Y. Suggestions for strategic allocation of the yellow river water resources under the new situation. Resour. Sci. 42 (1), 29–36 (2020).

Hoekstra, A. Y. Virtual Water Trade: Proceedings of the International Expert Meeting on Virtual Water Trade. Value of Water Research Report Series No. 12. Delft (Netherlands): UNESCO-IHE (2003).

Allan, J. A. Virtual water: a strategic resource global solutions to regional deficits. Ground Water. 36 (4), 545–546 (1998).

Falkenmark, M. & Rockström, J. The new blue and green water paradigm: breaking new ground for water resources planning and management. J. Water Resour. Plann. Manag. 132 (3), 129–132 (2006).

Chapagain, A. & Hoekstra, A. Y. Virtual Water Flows between Nations in Relation To Trade in Livestock and Livestock Products (Delft (Netherlands), 2003).

Ren, D. et al. Virtual nitrogen and phosphorus flow associated with interprovincial crop trade and its effect on grey water stress in China. Environ. Res. 16, 124018 (2021).

Tuyishimire, A. et al. Drivers of the increasing water footprint in africa: the food consumption perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 809, 152196 (2022).

Liu, L. et al. China’s dietary changes would increase agricultural blue and green water footprint. Sci. Total Environ. 903, 165763 (2023).

Chen, W. et al. Virtual water export and import in china’s foreign trade: A quantification using input-output tables of China from 2000 to 2012. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 132, 278–290 (2018).

Xie, P. et al. Spatial-temporal variations in blue and green water resources, water footprints and water scarcities in a large river basin: a case for the yellow river basin. J. Hydrol. 583, 124–135 (2020).

Oki, T., Yano, S. & Hanasaki, N. Economic aspects of virtual water trade. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 044002 (2017).

Lezzaik, K., Milewski, A. & Mullen, J. The groundwater risk index: development and application in the middle East and North Africa region. Sci. Total Environ. 628, 1149–1164 (2018).

Golden, O. et al. Assessing the impact of food trade centric on land, water, and food security in South Korea. J. Environ. Manag. 332, 117319 (2023).

Zhuo, L. et al. Water for maize for pigs for pork: an analysis of inter-provincial trade in China. Water Res. 166, 115079 (2019).

Chapagain, A. & Orr, S. An improved water footprint methodology linking global consumption to local water resources: A case of Spanish tomatoes. J. Environ. Manag. 90, 1219–1228 (2009).

Wiedmann, T. & Lenzen, M. Environmental and social footprints of international trade. Nat. Geosci. 11, 314–321 (2018).

Sun, S. et al. Geographical evolution of agricultural production in China and its effects on water Stress, Economy, and the environment: the virtual water perspective. Water Resour. Res. 55, 4014–4029 (2019).

Zhao, X. et al. Burden shifting of water quantity and quality stress from megacity Shanghai. Water Resour. Res. 52, 6916–6927 (2016).

Rosa, L. et al. Global unsustainable virtual water flows in agricultural trade. Nat. Commun. 14, 114001 (2019).

Liu, G. & Li, Y. China’s urban-rural and trade inequality in water footprint. Water 17, 231 (2025).

Liu, B. et al. Assessing virtual water trade and inequalities in household water footprints across california’s counties. Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 74, 175–185 (2025).

Wahba, S. M. A. & Consumption-Based Approach to trace the effects of income inequality on water pollution responsibility in egypt: an internal grey water footprint perspective. Ecol. Econ. 227, 108404 (2025).

Vanham, D., Mak, T. N. & Gawlik, B. M. Urban food consumption and associated water resources: the example of Dutch cities. Sci. Total Environ. 565, 232–239 (2016).

Vanham, D. & Leip, A. Sustainable food system policies need to address environmental pressures and impacts: the example of water use and water stress. Sci. Total Environ. 730, 139151 (2020).

Zhuo, L. et al. Inter- and intra-annual variation of water footprint of crops and blue water scarcity in the yellow river basin (1961–2009). Adv. Water Resour. 87, 29–41 (2016).

Wu, P. et al. Trade-offs between crop-related (physical and virtual) water flows and the associated economic benefits and values: a case study of the Yellow River Basin. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss. 1–32 (2018). (2018).

Zhuo, L. et al. Assessment of crop related physical-virtual water coupling flows and driving forces in yellow river basin. J. Hydraul Eng. 51 (9), 1059–1069 (2020). (in Chinese).

Zhuo, L. et al. Volume versus value of crop-related water footprints and virtual water flows: A case study for the yellow river basin. J. Hydrol. 608, 127674 (2022).

Zhang, F., Jin, G. & Liu, G. Evaluation of virtual water trade in the yellow river Delta, China. Sci. Total Environ. 784, 147285 (2021).

Feng, K. et al. Assessing regional virtual water flows and water footprints in the yellow river Basin, china: A consumption based approach. Appl. Geogr. 32, 691–701 (2012).

Wei, J. et al. Water scarcity risk through trade of the yellow river basin in China. Ecol. Indic. 154, 110893 (2023).

Albers, L. T. et al. Blue water footprint caps per sub-catchment to mitigate water scarcity in a large river basin: the case of the yellow river in China. J. Hydrol. 603, 126992 (2021).

Bogra, S., Bakshi, B. & Mathur, R. A water-withdrawal input–output model of the Indian economy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 1313–1321 (2016).

Marston, L. et al. High-resolution water footprints of production of the united States. Water Resour. Res. 54 (3), 2288–2316 (2018).

Zhao, X. et al. Physical and virtual water transfers for regional water stress alleviation in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116(14), 7110–7115 (2019).

Hoekstra, A. Y. et al. The Water Footprint Assessment Manual: Setting the Global Standard. London (UK) Earthscan (2011).

Ren, D. et al. Land-Water-Food nexus and indications of crop adjustment for water shortage solution. Sci. Total Environ. 626, 11–21 (2018).

Allen, R. G. et al. Crop Evapotranspiration - Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements. FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 56. Rome, FAO (1998).

Xin, L., Wang, L. & Liu, A. Regional production and consumption equilibrium of feed grain in China and its policy implication. J. Nat. Resour. 33 (6), 965–977 (2018). (in Chinese).

Wang, W. et al. A gridded dataset of consumptive water footprints, evaporation, transpiration, and associated benchmarks related to crop production in China during 2000–2018. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 15 (11), 4803–4827 (2023).

Shandong Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Shandong Statistical Yearbook 2021 (China Statistics, 2021). (in Chinese).

Inner Mongolia Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Inner Mongolia Statistical Yearbook 2021 (China Statistics, 2021). (in Chinese).

Shaanxi Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Shaanxi Statistical Yearbook 2021 (China Statistics, 2021). (in Chinese).

Shanxi Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Shanxi Statistical Yearbook 2021 (China Statistics, 2021). (in Chinese).

Ningxia Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Ningxia Statistical Yearbook 2021 (China Statistics, 2021). (in Chinese).

Gansu Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Gansu Statistical Yearbook 2021 (China Statistics, 2021). (in Chinese).

Henan Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Henan Statistical Yearbook 2021 (China Statistics, 2021). (in Chinese).

Water Resources Department of Shandong Province. Shandong Water Resources Bulletin (Shui Ziyuan Gongbao). accessed Aug 16, (2025). http://wr.shandong.gov.cn/zwgk_319/fdzdgknr/tjsj/szygb/

Department of Water Resources of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. Inner Mongolia Water Resources Bulletin (Shui Ziyuan Gongbao). accessed Aug 16, (2025). https://slt.nmg.gov.cn/xxgk/zfxxgkzl/fdzdgknr/gbxx/szygb/

Gansu Provincial Department of Water Resources. Gansu Water Resources Bulletin (Shui Ziyuan Gongbao). accessed Aug 16, (2025). https://slt.gansu.gov.cn/slt/c106726/c106732/c106773/c106775/tld.shtml

Qinghai Water Conservancy Information Network. Qinghai Water Resources Bulletin (Shui Ziyuan Gongbao). accessed Aug 16, (2025). https://slt.qinghai.gov.cn/articles/detail?id=1427097098649604096

Ningxia Water Conservancy. Ningxia Water Resources Bulletin (Shui Ziyuan Gongbao). accessed Aug 16, (2025). https://slt.nx.gov.cn/xxgk_281/fdzdgknr/gbxx/szygb/

Shaanxi Provincial Department of Water Resources. Shaanxi Water Resources Bulletin (Shui Ziyuan Gongbao). accessed Aug 16, (2025). https://slt.shaanxi.gov.cn/zfxxgk/fdzdgknr/zdgz/

Shanxi Provincial Department of Water Resources. Shanxi Water Resources Bulletin (Shui Ziyuan Gongbao). accessed Aug 16, (2025). https://slt.shanxi.gov.cn/zncs/szyc/szygb/

ESRI. ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10.8.1. Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands, CA, USA. https://support.esri.com

Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft PowerPoint 2010. Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA. https://www.microsoft.com

Xie, H. & Cheng, L. Influence factors and ecological compensation standard of winter wheat-fallow in the groundwater funnel area. J. Nat. Resour. 32 (12), 2012–2022 (2017). (in Chinese).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Situation Analysis of Ningxia Province (FAO, 2011). https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/cpesap/Data/Ningxia/SASNingxiawp.pdf

National Development and Reform Commission of China (NDRC). Outline of the Yellow River Basin’s Ecological Protection and High-Quality Development Plan (NDRC, 2021).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments, which significantly enhanced the clarity, structure, and analytical depth of this manuscript. We also gratefully acknowledge the Hebei Key Laboratory of Agricultural Water-Saving for providing essential experimental data that supported the estimation of virtual water content (VWC) in this study.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of China (42207551), Open Project of Hebei Key Laboratory of Agricultural Water-Saving (KFKT202401), Humanities and Social Sciences Research Program of the Ministry of Education (24YJA63008, 24YJCZH362), and Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2023MD089, ZR2024QD163).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.R., Q.M., and L.W. conceptualized the study. D.R. and H.M. conceived and provided the data for the virtual water and water stress evaluation. H.M. implemented the calculation with support from Y.L. and X.X. D.R. and H.M. analyzed and visualized the data, carried out the investigation, and drafted the paper. All co-authors reviewed and edited the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, D., Mao, H., Xiao, D. et al. Dietary differences amplify the water stress impacts of virtual water trade in the yellow river basin. Sci Rep 15, 44370 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28020-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28020-7