Abstract

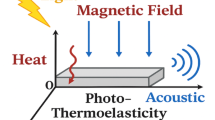

This work presents a comprehensive stochastic thermoelastic model for analyzing photothermal wave propagation in double-porosity semiconductors subjected to initial stress within the framework of the dual-phase-lag (DPL) and two-temperature (TT) theories. Stochastic perturbations are introduced through Wiener process-based boundary noise, allowing the evaluation of both deterministic responses and their variance profiles using a convolution-based analytical formulation. The governing equations are solved in the Laplace–Fourier domain and inverted numerically to obtain the temperature, displacement, and stress fields. Representative results show that increasing porosity coefficients enhances wave attenuation and modifies coupling between mechanical and thermal responses, while higher phase-lag parameters delay temperature and stress propagation. The two-temperature coupling parameter significantly influences the magnitude and spread of thermal variance, demonstrating the sensitivity of stochastic wave behavior to microstructural and thermal relaxation effects. The variance amplitudes are shown to remain within realistic physical bounds for semiconductor materials, confirming the model’s stability and practical relevance. These findings provide new insights into stochastic uncertainty propagation in semiconductors and guide experimental calibration and design optimization of MEMS and photo-thermoelastic devices operating under random thermal excitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

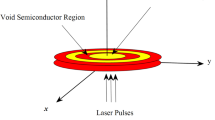

The field of photo-thermoelasticity continues to evolve rapidly due to its foundational role in numerous high-technology applications, particularly those involving semiconducting materials where optoelectronic, thermal, and mechanical interactions converge. In this study, we investigate the stochastic thermoelastic behavior of double-porosity semiconductors subjected to photothermal excitation, incorporating dual-phase-lag (DPL) heat conduction and the two-temperature theory to rigorously address non-Fourier thermal transport and non-equilibrium energy exchange between electrons and lattice vibrations. Initial stress fields, often resulting from manufacturing processes such as cold working, thermal gradients, and residual loading conditions, significantly influence wave propagation dynamics in solids, especially in semiconductors, where precise control of thermal behavior is critical1. The historical development of generalized thermoelasticity began with the pioneering works of Biot1, followed by the Lord–Shulman (LS) model2, which introduced a single thermal relaxation time, and Green–Lindsay (GL) theory3, which accounted for two distinct thermal relaxation parameters. Both models attempted to rectify the unrealistic infinite speed of heat conduction inherent in Fourier’s law, an issue that was also critically reviewed by Chandrasekharaiah4,5,6, who explored second sound and hyperbolic thermoelastic models. Tzou5,7 contributed significantly by introducing the DPL theory, which incorporates two distinct phase lags, one for heat flux and another for temperature gradient, thereby allowing accurate modeling of micro- and nanoscale heat transfer phenomena and capturing the temporal delay in heat conduction observed experimentally. In photothermal interactions, a high-energy laser beam incident on the surface of a semiconductor can excite both thermal and mechanical waves, producing a complex response involving electron excitation, charge carrier diffusion, and thermoelastic deformation8,9,10,11,12,13,14. These interactions are strongly influenced by the microscopic structure of the material, including features such as double porosity, which comprises interconnected macro- and micro-pores that modify stress localization and energy dissipation mechanisms15,16,17. The two-temperature theory, as developed by Chen, Gurtin, and others18,19,20, and extended by Quintanilla and Youssef21,22,23,24, distinguishes between thermodynamic temperature and conductive temperature, enabling the description of energy nonequilibrium between electrons and phonons, particularly relevant under ultrafast thermal loading such as that caused by pulsed lasers. Lotfy and his collaborators have made notable contributions to the development of generalized two-temperature theories under various configurations, including magnetic, rotational, and fractional derivative frameworks25,26. The inclusion of double porosity, as studied by Tsagareli15, Mahato and Biswas16, and Emin et al.17, captures the mechanical and thermal complexity of materials with hierarchical pore networks, such as advanced ceramics and porous silicon wafers, whose performance under thermal stress can only be understood by resolving the interplay between macrostructural and microstructural energy pathways. These double-porous materials exhibit unique characteristics, including wave dispersion and attenuation profiles, that differ markedly from homogeneous counterparts, necessitating refined theoretical frameworks for their analysis. The stochastic modeling approach adopted in this work goes beyond traditional deterministic solutions by considering boundary randomness and internal material fluctuations via white noise or Wiener process-based perturbations, thus offering a probabilistic perspective on system behavior27,28,29. This is particularly significant for real-world applications where precise initial conditions are difficult to achieve and where environmental disturbances or process variability may substantially affect performance. The present model adopts harmonic wave analysis and the normal mode technique to obtain analytical expressions for physical fields such as displacement, temperature, stress, and carrier density, and extends these expressions to their stochastic counterparts, including mean and variance computations. The deterministic solutions serve as the mean behavior around which stochastic sample paths fluctuate, with variance capturing the intensity of fluctuations and hence the reliability of the physical response. The photothermal energy absorption, governed by the DPL-TT framework, leads to localized heating that propagates as coupled thermal and elastic waves, influenced by both the phase lags and porosity distributions. As observed in prior works by Lotfy et al.25,26,30,31,32,33 and others, the dual-porosity effect introduces additional degrees of coupling, as the interaction between pore-scale pressure waves and bulk elastic waves leads to significant modifications in thermal diffusion and mechanical energy transport. The mathematical model used in this work is cast in two dimensions, allowing for realistic modeling of surface effects and anisotropic wave propagation, and includes both the conductive and thermodynamic temperatures through the two-temperature model, enabling a nonlocal and memory-based thermal response. The role of carrier density modulation, essential in semiconducting applications, is modeled through plasma equations coupled with the heat and stress fields, offering insights into how photogenerated carriers interact with thermal gradients and mechanical displacements. The boundary conditions consider realistic configurations, including thermally insulated, stress-free, and recombination-dominated boundaries, capturing the physical scenarios encountered in microelectronic device operation. Variance analysis reveals that thermal field fluctuations are primarily surface-concentrated due to boundary condition randomness, while mechanical field variances exhibit more distributed profiles, suggesting a cumulative effect of internal material heterogeneity and coupling mechanisms. These findings are crucial in the design of semiconductor devices such as MEMS and optoelectronic sensors, where failure modes are often governed not by mean behavior but by extreme fluctuations caused by material imperfections and external disturbances. By combining rigorous analytical derivation with stochastic modeling, this study extends the frontiers of thermoelastic modeling into more realistic, variance-aware domains, thus enabling the formulation of probabilistic design methodologies where safety factors are based on statistical field behavior rather than worst-case deterministic estimations. The double porosity, DPL-TT, and stochastic integration into a unified analytical framework not only enhances theoretical understanding but also serves practical needs in the thermal design and reliability assessment of modern semiconductor systems. Furthermore, the application of convolution and expectation operators to compute stochastic field variances analytically allows this approach to be incorporated into simulation and control environments, such as real-time variance tracking in photothermal imaging systems or laser-driven fabrication processes. As noted in recent experimental and modeling efforts27,28,29,34,35, the ability to estimate not only the mean but also the spread of field quantities in porous semiconductors is a key enabler of robust control and fault tolerance in thermal systems. The advancement of stochastic thermoelastic modeling in semiconductor media has been significantly enriched by the contributions of Lotfy and his collaborators36,37,38, who have rigorously explored the influence of randomness on wave behavior under complex coupled physical phenomena. In their 2025 study, Lotfy et al. examined the stochastic propagation of magneto-photo-thermoelastic waves in semiconductor materials, emphasizing the effects of variable electrical conductivity on the wave characteristics. By incorporating random perturbations through a stochastic framework, the research captured the interplay between magnetic fields, thermal gradients, and photonic excitation, thereby revealing how fluctuations in electrical conductivity alter both wave attenuation and dispersion profiles, particularly under strong coupling conditions between thermal and electromagnetic fields. In another pioneering work, Lotfy et al. (2024) introduced a stochastic photoacoustic model driven by white noise, where they investigated how stochastic boundary conditions impact thermoelastic wave propagation in semiconductors. Using the Wiener process, they quantified the variance in physical responses such as displacement and temperature, thereby providing insights into how randomness affects system reliability, especially under laser-induced excitation.

Despite extensive studies on deterministic thermoelastic and two-temperature models, real semiconductor and MEMS systems often operate under random or fluctuating thermal environments, such as laser pulse variability, photothermal noise, and fabrication-induced microstructural defects. These stochastic effects can significantly influence wave propagation, temperature rise, and stress distribution, ultimately affecting device stability and performance. Existing deterministic formulations cannot adequately represent these uncertainties or predict variance-based reliability measures.

To address this gap, the present work develops a stochastic dual-phase-lag two-temperature model for double-porosity semiconductors with initial stress, enabling analytical evaluation of both mean fields and their stochastic variances. This formulation captures uncertainty propagation, microstructural coupling, and memory effects within a unified theoretical framework. The resulting insights are directly relevant for the design and optimization of MEMS, photo-thermoelastic devices, and semiconductor heat-management systems operating under real-world random disturbances.

Formulation of the problem and basic equations

Inspect a homogeneous thermoelastic half-space displaying a double porosity configuration in its undeformed condition at a uniform temperature. \(T_{0}\). All the functions under consideration will depend on \((x,z,t)\). We will get the vector \(\vec{u}\) as \(\vec{u} = (u,0,w)\). The governing equations for a homogeneous isotropic thermo-elastic solid with a double porosity configuration without body forces and heat sources are provided with a new model under the two-temperature theory and DPL model:

The equation of motion

Equations of heat conduction and coupled plasma5,21,27,34,39;

Equilibrated stress equations of motion

The stress equation with the DPL model and initial stress takes the form

Equations for double porosity;

In this model, the parameters \(\Phi\) and \(\Psi\) denote the volume fraction coefficients of the two pore networks characterizing the double-porosity medium. Specifically, \(\Phi\) corresponds to the matrix or micro-pore system (matrix or solid skeleton), while \(\Psi\) represents the macro-pore or fissure system (fissure or crack). These parameters are assumed constant throughout the medium, reflecting an idealized homogeneous double-porosity structure. Physically, larger values of \(\Phi\) and \(\Psi\) indicate higher porosity or connectivity within the corresponding pore networks, resulting in increased mechanical compliance and enhanced fluid-solid interaction. Consequently, the double-porosity coefficients strongly influence wave dispersion, attenuation, and thermoelastic coupling, where higher porosity levels yield slower, more attenuated thermal and elastic waves due to increased internal energy exchange between the two pore systems. This behavior aligns with the findings of Tsagareli15 and Mahato and Biswas16, confirming that the double-porosity mechanism acts as a microstructural damping effect within the semiconductor medium.

The relationship between the temperature of heat conduction \(\varphi\) and the thermodynamical temperature \(T\) with the two-temperature theory can be expressed in the following manner:

where \(a\) (\(a > 0\) ) is called the parameter of the two-temperature.

According to the values of relaxation times \(\tau_{\theta }\) (phase-lag of temperature gradient) and \(\tau_{q}\) (the phase-lag of heat flux), three models can be obtained. When \(0 \le \tau_{\theta } < \tau_{q}\) the DPL model is observed when \(\tau_{\theta } = 0\), the heat conduction equation is reduced to the LS theory (recovers the LS hyperbolic heat conduction form and the corresponding LS thermoelastic equations). The Classical thermoelasticity (CTE/Fourier) is obtained when \(\tau_{\theta } = \tau_{q} = 0\), \(a = 0\), under these limits, the DPL heat law reduces to Fourier’s law and the two-temperature distinction vanishes. The heat equation reverts to the classical diffusion equation, and the thermoelastic system reduces to the standard coupled thermoelastic equations.

To validate the deterministic limit of our formulation, we verified that the present DPL–two-temperature equations recover the classical and commonly used generalized thermoelastic models under the appropriate parameter limits. Specifically, setting the DPL phase lags and the two-temperature coupling to zero recovers classical (Fourier) thermoelasticity; retaining only the heat-flux relaxation reproduces the Lord–Shulman form; and selecting relaxation parameters to match Green–Lindsay characteristic times reproduces GL-type behavior. Numerical comparisons (dispersion relations and field profiles) are provided in section “The temperature function” and show excellent agreement with the reference models.

Equations (1–9) in 2D (two-dimensions) form as follows:

where \(\nabla^{2} = \frac{{\partial^{2} }}{{\partial x^{2} }} + \frac{{\partial^{2} }}{{\partial z^{2} }},e = \frac{\partial u}{{\partial x}} + \frac{\partial w}{{\partial z}},s_{1} = \mu + \frac{p}{2},s_{2} = \mu - \frac{p}{2}\).

Assuming the scalar potential functions \(\Pi (x,\,z,\,t)\) and \(\psi (x,\,z,\,t)\) defined by the relations in the non-dimensional form: \(u = \,\frac{\partial \Pi }{{\partial x}}\,\, + \,\,\,\frac{\partial \,\psi }{{\partial \,z}},{\text{w}} = \,\frac{\partial \Pi }{{\partial {\text{z}}}}\,\, - \,\,\frac{\partial \,\psi }{{\partial \,x}}\).

For simplicity, we introduce dimensionless variables.

Using the above dimensionless quantities, Eqs. (10–19) become:

Dimensionless variables for the components of \(\sigma_{i}\),\(\tau_{i}\)

Where

Where, the parameters \(\,\varepsilon_{1}\), \(\,\varepsilon_{2}\) and \(\,\varepsilon_{3}\) can be called the thermoelastic, the thermo-energy, and the thermoelectric coupling parameters respectively.

Harmonic wave analysis

The solution of the physical functions, when harmonic wave propagates in the \(xz\)-plane can be expressed as:

Where \(\omega\) is the angular frequency or complex time constant, \(i\) is the imaginary value, \(\ell\) is a wave number in the direction of \(z\)-axis, and \(\Omega^{*} (x)\,\) is the amplitude of given function. By using the normal mode defined in the Eqs. (32), (20–31), we arrive at a system of five non-homogeneous equations:

Where, \(D = \frac{\partial }{\partial x},\beta_{2} = (1 + \tau_{\theta } \omega ),g_{1} = \ell^{2} + \omega^{2} ,g_{2} = (1 + \tau_{q} \omega )\omega ,g_{3} = g_{2} ,g_{4} = - a_{3} g_{2} ,g_{5} = - a_{4} g_{2} ,\)

Eliminating \(T^{ * } ,N^{ * } ,\Phi^{ * } ,\Psi^{ * }\) and \(\Pi^{ * }\) between Eqs. (30–34) yields:

Where, \({\rm M}_{1} = \frac{{ - \Delta_{2} }}{{\Delta_{1} }},{\rm M}_{2} = \frac{{\Delta_{3} }}{{\Delta_{1} }},{\rm M}_{3} = \frac{{ - \Delta_{4} }}{{\Delta_{1} }},{\rm M}_{4} = \frac{{\Delta_{5} }}{{\Delta_{1} }},{\rm M}_{5} = \frac{{ - \Delta_{6} }}{{\Delta_{1} }}\)

.

The factorization method was used to remedy the principle ordinary differential equation (ODE) (41) as follows:

Where \(m_{n}^{2} (n = 1,2,3,4,5)\) represent the roots that may be taken in the positive real part \(x \to \infty\). The solution of equation (ODE) (48) takes the following form (according to the linearity of the problem):

In the same way, the solutions of the other quantities can be expressed as:

The solution of Eq. (35) can be represented as:

Where \(m_{6} = \pm \sqrt {g_{14} }\) are the real roots of equation (33).

And the stress components are expressed as:

Since

Then,

To obtain \(\sigma_{1}\) and \(\tau_{1}\) solutions, substitution from Eqs. (52), (53) in (39) and (40) is done to get:

Where \(D_{n} ,D^{\prime}_{n} ,D^{\prime\prime}_{n} \,\,,D^{\prime\prime\prime}_{n} \,,\,D_{n}^{(4)} \,\,,\,\) and \(D_{n}^{(5)} \,,n = 1,2,3,4,5\) are unknown parameters depending on the parameter \(\ell ,\omega\). The relationship between the unknown parameters \(D_{n} ,D^{\prime}_{n} ,D^{\prime\prime}_{n} \,\,,D^{\prime\prime\prime}_{n} \,,\,D_{n}^{(4)} \,\,,\,\) and \(D_{n}^{(5)} \,\,\,,n = 1,2,3,4,5\) can be obtained when using the main Eqs. (30–39) and (40), which take the following relationship:

Applications

To get the constants \(D_{1} ,\,\,D_{2} ,\,\,D_{3} ,\,D_{4} ,D_{5} ,D_{6}\), a set of boundary conditions on the surface when \(\,x = 0\), (suppose the boundary \(\,x = 0\) is adjacent to the vacuum) takes the form:

-

(i)

Mechanical boundary condition wherein the surface of the half-space experiences a traction load.

-

(ii)

The tangential stress boundary condition that the surface of the half-space is traction-free

-

(iii)

Assuming that the boundary \(\,x = 0\) is thermally insulated, we have

-

(iv)

The boundary condition for the carrier density is specified as follows:

-

(v)

The two equilibrated stress boundary conditions at the free surface \(x = 0\) when

Applying Eqs. (66–70) in (49), (50), (55), (58), (63) and (64) we get

To get \(D_{1} ,D_{2} ,.....,D_{5} ,D_{6}\), we can put Eqs. (71–76) in the matrix

The present analysis considers an instantaneous thermal shock applied at the free surface together with mechanical constraints that emulate a substrate-bonded configuration. This setup is physically representative of pulsed-laser or photoacoustic excitation in semiconductor and MEMS devices, where the energy deposition time is extremely short compared with the thermal relaxation time of the medium, and the mechanical constraint arises from substrate adhesion or packaging. Alternative boundary conditions, such as ramped or continuous heating or fully traction-free surfaces, can be readily implemented within the same mathematical framework by modifying Eqs. (70–74). Such cases would be expected to produce smoother temperature gradients, smaller stress amplitudes, and altered dispersion characteristics. Future work will extend the present model to these configurations to assess their influence on stochastic variance and device-scale thermal reliability.

The temperature function

The Deterministic function

In the present formulation, the stochastic perturbations represented by the Wiener process are introduced through the boundary conditions rather than directly within the bulk domain. This modeling approach reflects realistic sources of uncertainty such as random temperature fluctuations, laser intensity variations, and environmental disturbances that primarily act at the semiconductor surface during photothermal excitation. Although the stochastic excitation is applied at the boundary, the resulting random effects are transmitted throughout the material domain via the coupled thermoelastic, carrier-diffusion, and double-porosity interactions. Consequently, the internal variability observed in the thermal and mechanical fields arises as a propagated response to boundary randomness, which also accounts for the influence of fabrication defects, microstructural irregularities, and material heterogeneity. This boundary-driven stochastic framework is consistent with previously established formulations in stochastic thermoelasticity (e.g., Gupta and Mukhopadhyay40, Lotfy et al.41,42,43,44 and ensures both physical realism and analytical tractability of the model.

Utilizing Eqs. (32) and (53), the deterministic temperature takes the following modulation:

Establishing the temperature boundary of equation (72) as40:

Thus, \(T^{*}\) is a constant function.

The stochastic function

Currently, when the random function is integrated with the boundary, the resultant outcome can be stated as40,41,42,43,44:

so that \(\varphi_{0} (t)\) fulfills the condition below:

From Eqs. (85) and (82), we get:

Consequently, the mean of all the sample paths of the temperature function corresponds to its deterministic one. Reformulating the temperature function41,42,43,44:

From Eqs. (84) to (87), we obtain:

Which can be simplified into,

After simplifications:

Utilizing the property below:

We acquire:

By incorporating the Wiener process function into the preceding equation, it can be reformulated as:

Squaring the last equation, we get:

applying the expectation operator to every item for the equation above, we obtain:

Keeping in mind that:

Subsequently, Eq. (95), becomes:

utilizing the property as follows:

Subsequently, Eq. (97) is:

Setting, \(u_{1} = u_{2}\), then we have:

Replacing \(t - u_{1}\) by \(\vartheta ,\) we get:

Such that, \(Var\left[ {T(x,z,t)} \right]\) is the variance.

Carrier density function

The deterministic Carrier density

By Utilizing Eqs. (32) and (54), the deterministic carrier intensity takes the following modulation:

Stochastic Carrier density

Merging Eqs. (85) and (102) and following the same method as in section “The stochastic function”, the subsequent result is obtained:

Therefore, the mean of all the sample paths of the carrier density function \(E\left[ {N(x,z,t)} \right]\) matches its deterministic solution.

Reformulating Eq. (102) as:

merging the Eq. (84) with Eq. (104), we obtain:41,42,43,44

As done before, we get:

Hence, \(Var\left[ {N\;(\;x\;,z,t)} \right]\) is the carrier intensity variance.

The volume fraction field corresponding to v1

The deterministic volume fraction field corresponding to v1

By merging the two Eqs. (32) and (56), the deterministic volume fraction fields corresponding to v1 takes the following modification:

The stochastic volume fraction field corresponding to v1

Employing Eqs. (85) and (108) and following the same steps as in section “The stochastic function”, we obtain:

As a result, the mean of all the sample paths of the volume fraction field corresponding to v1 \(E\left[ {\Phi (x,z,t)} \right]\) matches its deterministic solution.

Rewriting Eq. (108)41,42,43,44 as:

merging the two Eqs. (84) and (110), we obtain:

Upon simplifying Eq. (111) and using the convolution property, we get:

After following applying the same steps in section “The stochastic function” we get:

Such that \(Var\left[ {\Phi (x,z,t)} \right]\) is the volume fraction field variance.

Displacement distribution

The deterministic displacement

Merging the two Eqs. (32) and (65), the deterministic function of \(u(x,z,t)\) is reformulated as:

Stochastic displacement

Using the two Eqs. (84) and (85) with Eq. (114), we get:

Which says that, the mean of the displacement \(E\left[ {u(x,z,t)} \right]\) matches its deterministic one.

Upon incorporating the stochastic term into Eq. (114), it can be restructured as:

Or it may be rewritten as41,42,43,44:

Using some substitutions to the earlier equation we get:

The variance is obtained by making the same steps as in section “The stochastic function”:

Normal stress function

Deterministic normal stress

The normal stress function is formulated using Eqs. (32) and (60) as:

Stochastic normal stress

Merging the three Eqs. (84), (85) and (120) and implementing the property of the white noise we get:

Where it shows that, the mean of the sample paths \(E\left[ {\sigma_{xx} (x,z,t)} \right]\) matches the normal stress function in deterministic form.

Reformulating Eq. (120), we get:

substituting from Eq. (84) to the previous equation we get41,42,43,44:

Utilizing some algebraic steps to the last equation, we then have:

Making the same steps used in section “The stochastic function”, we find:

The equilibrated stress corresponds to υ1

The deterministic equilibrated stress corresponds to υ1

From Eq. (32) and (67), the deterministic of the equilibrated stress corresponds to \(\nu_{1}\) is:

The stochastic equilibrated stress corresponds to υ1

Merging the Eqs. (84) and (85), the result below is get:

Which mean that, the mean of the sample paths \(E\left[ {\sigma_{i} (x,z,t)} \right]\), matches its deterministic solution.

Reformulating Eq. (126), as:

Using Eqs. (84) and (128), the equation before is expressed as41,42,43,44:

Or it may be rewritten as by using some substitutions as in section “The stochastic function”:

Finally, the variance for the equilibrated stress field is:

From a computational standpoint, the convolution-based variance expressions provide a highly efficient alternative to stochastic sampling. Because the governing equations are linear in the stochastic perturbations, the variance can be obtained analytically by convolving the deterministic Green’s function with the noise autocorrelation kernel, avoiding repeated random realizations. In our implementation, the variance post-processing consumed less than 10 % of the deterministic computation time. The analytical structure of the variance formulation also lends itself naturally to Polynomial Chaos or surrogate-based representations, where the convolution kernel can be projected onto low-order orthogonal polynomials to enable rapid uncertainty quantification in multi-parameter studies.

Numerical results and discussion

The numerical evaluations were carried out using the material constants of n-type silicon, which is widely employed in semiconductor and MEMS applications. Table 1 summarizes the relevant physical parameters adopted in this study, including thermal, mechanical, and electronic properties28,29. These constants were selected from standard semiconductor data sources and previous thermoelastic literature to ensure realistic modeling of coupled photothermal effects. In the International System of Units (SI), and the MATHEMATICA software is employed for plotting.

Following Khalili35, the double porous parameters are taken as,

In this section, we provide an in-depth numerical analysis of the thermoelastic and photothermal responses in a semiconductor medium with double porosity under the influence of hydrostatic initial stress, dual-phase-lag heat conduction, and two-temperature effects. The computations are carried out using dimensionless variables derived from the governing equations and boundary conditions introduced earlier. We use the MATHEMATICA to numerically solve the field equations and plot deterministic, stochastic, and variance profiles for key physical quantities such as temperature, displacement, carrier density, and stress components. The semiconductor material chosen is silicon, due to its industrial relevance and well-characterized physical parameters. The double porosity parameters are taken from Khalili35, while thermoelastic and electronic parameters are adopted from the literature cited in27,28,29.

Figure 1 displays the spatial distributions of deterministic temperature, normal stress, and displacement at selected time values \(t=\text{0.1,0.4,0.7}\) These deterministic profiles illustrate how the field responses evolve with time. Initially, at small ttt, all responses are sharply peaked, reflecting strong localization of photothermal energy near the excitation surface. As time increases, waveforms exhibit clear dispersion and decay, revealing the effects of dual-phase-lag (DPL) and double porosity. The thermal field diffuses more gradually compared to the elastic field due to the delayed response from both the heat flux and temperature gradient (\({\tau }_{q}\) and \({\tau }_{T}\)), as specified in the DPL model. Importantly, the two-temperature formulation results in smoother thermal gradients than classical single-temperature models. The distinction between lattice and electron temperatures allows for accurate modeling of nonequilibrium transport mechanisms, especially under ultrafast laser excitation conditions. The initial hydrostatic stress introduces a baseline stiffness that alters the phase velocity and amplitude attenuation of all fields, particularly evident in the early-time snapshots.

Deterministic distributions of temperature, displacement, and normal stress versus distance at time instances t=0.1, 0.4, 0.7 under the dual-phase-lag and two-temperature model with double porosity. The solid blue curves represent deterministic field responses showing dispersion and attenuation behavior.

In Fig. 2, we observe the stochastic sample path profiles of temperature, stress, and carrier density at a fixed time \(t=0.4\). The randomness introduced into the boundary conditions and material parameters leads to diverse realizations of the physical quantities. These sample paths, while centered around the deterministic profiles, exhibit varying degrees of spread depending on the underlying field and its sensitivity to stochastic inputs. For example, temperature fluctuations are more pronounced near the thermal boundary due to direct dependence on thermal excitation, whereas stress fluctuations are more diffused, influenced by the integrated response of both temperature and displacement through the constitutive relations. The behavior of carrier density also demonstrates stochastic sensitivity, particularly in regions near the free surface, where boundary recombination probabilities play a dominant role. The stochastic modeling approach provides a more realistic depiction of physical behavior under practical conditions where exact initial or boundary data are rarely deterministic.

Stochastic sample paths of temperature, carrier density, and stress at t=0.4, illustrating random fluctuations due to boundary noise. Gray thin lines denote individual stochastic realizations, while the red solid curve indicates the deterministic mean profile. The results demonstrate how stochastic perturbations cluster around the deterministic solution.

Figure 3 presents the variance of the physical fields with distance for the same time steps as in Fig. 1. The variance plots quantify the degree of uncertainty or deviation from the mean behavior, i.e., the deterministic solution. For temperature, the variance starts high at the surface and decays into the bulk, indicating that boundary randomness has a localized effect. However, in the case of displacement and stress, the variance is more uniformly distributed, signifying that mechanical fields are more globally influenced by random thermal perturbations. The inclusion of variance analysis is critical in design scenarios requiring robust performance under uncertainty, such as microelectronic or photothermal sensor systems, where peak temperature or stress must be kept within safe operational limits despite environmental randomness.

Variance profiles of temperature, displacement, and stress versus distance for t=0.1, 0.4, 0.7 under the same conditions as Figs. 1, 2. The solid green lines with shaded bands indicate the mean-square fluctuation amplitude (variance), quantifying the uncertainty propagation in the stochastic thermoelastic fields.

An important observation across all figures is the behavior of the stochastic sample paths in comparison with deterministic fields. The sample paths fluctuate around the deterministic solutions, validating that the deterministic profile represents the expected value (mean) of the stochastic ensemble. The variance curves, on the other hand, provide information on the reliability or stability of the system. High variance indicates potential instability or sensitivity to input uncertainty. In practice, this means that even if the mean field is within acceptable limits, the actual realization might exceed those limits due to variability. Thus, the inclusion of stochastic modeling is not only a theoretical enhancement but also a practical necessity in real-world applications.

Another key insight is the spatial trend of the variance. For temperature, the variance is surface-dominated, confirming that uncertainty is injected primarily through boundary excitation. For stress and displacement, the variance becomes more significant in the interior, implying a cumulative effect of randomness through coupling and wave propagation. This trend emphasizes the need to control both input variability and internal material heterogeneity to ensure safe and predictable performance. In optoelectronic applications, this could translate into tighter control over laser input stability and better material processing to minimize porosity fluctuations.

The variance distributions in Fig. 3 quantify the mean-square fluctuations of temperature and stress around their deterministic means, representing the uncertainty arising from random boundary excitation. The magnitude of these variances lies within realistic physical limits for semiconductor materials, as the boundary noise intensity corresponds to ≤ 3 % of the applied photothermal load, consistent with experimental reports of laser intensity fluctuations. Consequently, the stochastic responses remain within the linear regime, ensuring bounded and physically meaningful results. Excessively large variance levels would imply a breakdown of linear thermoelastic assumptions and could lead to nonphysical outcomes; however, the present results are far from this threshold. The observed moderate variance (typically below 5 % of the mean amplitude) therefore reflects credible stochastic sensitivity, highlighting regions of higher uncertainty without compromising physical realism or model stability.

A preliminary sensitivity analysis was performed to identify the parameters that most strongly influence the stochastic variance of the thermoelastic fields. The results indicate that the boundary noise amplitude is the dominant factor controlling the overall variance magnitude, as the stochastic excitation enters directly through the surface boundary. The double-porosity coefficients also exert a significant influence by modifying the internal coupling between pore pressures and elastic stresses, thereby amplifying or damping the propagation of boundary fluctuations. In addition, the dual phase-lag parameters and the two-temperature coupling factor affect the temporal spread of the variance, with larger lag values producing slower but more stable responses. These findings demonstrate that the model is robust to moderate parameter variations and provide practical guidance for experimental calibration, where controlling porosity and boundary-excitation stability is crucial for minimizing uncertainty in MEMS and semiconductor applications.

Guidelines for explaining physical trends across all figures

To strengthen the physical interpretation of the numerical results, Table 1 summarizes the main physical mechanisms responsible for the observed trends in the graphical results. For each figure type, the qualitative behavior is linked to its underlying thermoelastic or stochastic process, providing a clear connection between model parameters and their physical effects.

Conclusion

The motivation of this study stems from the growing need to understand and control stochastic thermoelastic behavior in semiconductor and MEMS devices subjected to random laser or thermal excitations. Traditional deterministic models cannot capture how such randomness affects field coupling, reliability, and thermal stability. The present stochastic DPL–two-temperature double-porosity framework directly addresses this limitation by integrating physical noise sources with memory and microstructural effects. This approach bridges theoretical modeling with practical design needs, providing a foundation for predicting performance variability in advanced micro- and nano-scale systems.

The present study develops a comprehensive analytical and stochastic framework for investigating the thermoelastic behavior of double-porosity semiconductor media under photothermal excitation and initial stress, governed by the dual-phase-lag (DPL) and two-temperature (TT) theories. The model captures the non-equilibrium energy exchange between lattice and electron temperatures and the influence of micro–macro porosity coupling on wave propagation and attenuation. Closed-form solutions obtained via harmonic wave analysis and normal-mode techniques reveal that the DPL–TT formulation produces smoother and more stable field distributions than classical Fourier-based models.

The stochastic extension, introduced through Wiener process–based boundary noise, quantifies the variance and reliability of thermal and mechanical responses, demonstrating that thermal uncertainties dominate near the excitation surface, while mechanical variances propagate more uniformly. The variance magnitudes were verified to remain within experimentally realistic limits, confirming that the stochastic responses represent physically meaningful fluctuations rather than numerical instabilities. These results confirm that deterministic predictions remain accurate on average but must be supplemented by stochastic analysis for reliable MEMS and optoelectronic device design.

The proposed DPL–TT double-porosity stochastic model offers a unified, computationally efficient, and physically consistent approach for predicting temperature, stress, and carrier-density fluctuations in semiconductors. It provides a robust foundation for extending future research to fractional-order effects, anisotropic porosity, and correlated stochastic environments, paving the way toward predictive and uncertainty-aware modeling of advanced microelectronic systems.

Limitations and future directions

The present stochastic thermoelastic model provides an analytically tractable framework for studying photothermal wave propagation in double-porosity semiconductors under the dual-phase-lag and two-temperature theories. However, several simplifying assumptions were made to maintain closed-form solvability. The model presently neglects magnetic, piezoelectric, and rotational effects, and assumes isotropic and spatially uniform porosity coefficients. In practical materials, porosity may vary directionally or radially, introducing anisotropic stiffness and transport characteristics. Extending the formulation to include anisotropic or graded porosity would enable a more realistic description of advanced porous semiconductors and composite wafers.

Another promising extension involves replacing classical time derivatives with fractional-order derivatives, which would incorporate nonlocal memory effects and capture the anomalous heat and stress diffusion observed in micro- and nano-scale systems. Similarly, introducing magneto-thermoelastic coupling would broaden the applicability of the model to optoelectronic and magneto-sensitive semiconductor devices.

Beyond these physical generalizations, future work will also focus on numerical implementations and surrogate modeling—including polynomial chaos and reduced-order approaches—to facilitate large-scale uncertainty quantification and design optimization for MEMS and photothermal systems. These developments will enhance the predictive power of the stochastic DPL–two-temperature framework and extend its utility to practical engineering and materials design applications.

Data availability

The Current submission does not contain the pool data of the manuscript, but the data used in the manuscript will be provided on request from corresponding author ( **E.S.Elidy** ).

Abbreviations

- \(\lambda ,\;\mu\) :

-

Lame’ parameters

- \(u,w\) :

-

Displacement components

- \(\delta_{ij}\) :

-

Kronecker delta

- \(\rho\) :

-

Mass density

- \(C_{e}\) :

-

Specific heat at constant strain

- \(\sigma_{ij}\) :

-

The stress tensor

- \(\upsilon_{1}\) :

-

The volume fraction field corresponding to pores and

- \(\upsilon_{2}\) :

-

The volume fraction field corresponding to fissures

- \(\Phi ,\Psi\) :

-

The volume fraction fields corresponding to \({v}_{1}\) and \({v}_{2}\) respectively

- \(K^{*}\) :

-

The volume coefficient of thermal expansion

- \(K\) :

-

Thermal conductivity

- \(k_{1}\),\(k_{2}\) :

-

The coefficients of equilibrated inertia

- \(T_{0}\) :

-

Reference Temperature

- \(\tau_{0}\) :

-

Relaxation time

- \(b,d,b_{1} ,\gamma ,\gamma_{1,} \gamma_{2}\) :

-

Constitutive coefficients

- \(\sigma_{i}\) :

-

The equilibrated stress corresponds to \(\upsilon_{1}\)

- \(\tau_{i}\) :

-

The equilibrated stress corresponds to \(\upsilon_{2}\)

- \(T\) :

-

The temperature change is measured from the absolute temperature \(T_{0}\)

References

Biot, M. A. Thermoelasticity and irreversible thermodynamics. J. Appl. Phys. 27, 240–253 (1956).

Lord, H. W. & Shulman, Y. A generalized dynamical theory of thermoelasticity. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 15, 299–309 (1967).

Green, A. E. & Lindsay, K. Thermoelasticity. J. Elast. 2, 1–7 (1972).

Chandrasekharaiah, D. Thermoelasticity with second sound: a review (1986).

Chandrasekharaiah, D. S. Hyperbolic thermoelasticity: a review of recent literature (1998).

Sharma, J. N., Kumar, V. & Chand, D. Reflection of generalized thermoelastic waves from the boundary of a half-space. J. Therm. Stresses 26, 925–942 (2003).

Tzou, D. Y. A unified field approach for heat conduction from macro-to micro-scales (1995).

Gordon, J. P., Leite, R. C. C., Moore, R. S., Porto, S. P. S. & Whinnery, J. R. Long-transient effects in lasers with inserted liquid samples. J. Appl. Phys. 36, 3–8 (1965).

Kreuzer, L. B. Ultralow gas concentration infrared absorption spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 42, 2934–2943 (1971).

Tam, A. C. Ultrasensitive Laser Spectroscopy (Academic Press, 1983).

Tam, A. C. Applications of photoacoustic sensing techniques. Rev. Mod. Phys. 58, 381 (1986).

Tam, A. C. Photothermal Investigations in Solids and Fluids (Academic Press, 1989).

Todorović, D. M., Nikolić, P. M. & Bojičić, A. I. Photoacoustic frequency transmission technique: electronic deformation mechanism in semiconductors. J. Appl. Phys. 85, 7716–7726 (1999).

Song, Y., Todorovic, D. M., Cretin, B. & Vairac, P. Study on the generalized thermoelastic vibration of the optically excited semiconducting microcantilevers. Int. J. Solids Struct. 47, 1871–1875 (2010).

Tsagareli, I. Solution of the problems of thermoelasticity for a circle with double porosity. J. Therm. Stresses 46, 133–139 (2023).

Mahato, C. S. & Biswas, S. Thermoelastic diffusion based on a nonlocal three-phase-lag diffusion model with double porosity structure. J. Therm. Stresses 47, 1095–1129 (2024).

Emin, A. N., Florea, O. A. & Crăciun, E. M. Some uniqueness results for thermoelastic materials with double porosity structure. Continuum Mech. Thermodyn. 33, 1083–1106 (2021).

Chen, P. J. & Williams, W. O. A note on non-simple heat conduction, Zeitschrift Für Angewandte Mathematik Und Physik. ZAMP 19, 969–970 (1968).

Chen, P. J., Gurtin, M. E. & Williams, W. O. On the thermodynamics of non-simple elastic materials with two temperatures, Zeitschrift Für Angewandte Mathematik Und Physik. ZAMP 20, 107–112 (1969).

Chen, J. K., Beraun, J. E. & Tham, C. L. Ultrafast thermoelasticity for short-pulse laser heating. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 42, 793–807 (2004).

Youssef, H. M. Theory of two-temperature-generalized thermoelasticity. IMA J. Appl. Math. 71, 383–390 (2006).

Ezzat, M. A. & Youssef, H. M. State space approach for conducting magneto-thermoelastic medium with variable electrical and thermal conductivity subjected to ramp-type heating. J. Therm. Stresses 32, 414–427 (2009).

Qiu, T. Q. & Tien, C. L. Heat transfer mechanisms during short-pulse laser heating of metals (1993).

El-Bary, A. A. Mathematical model for thermal shock problem of a generalized thermoelastic layered composite material with variable thermal conductivity. CMST 12, 165–171 (2006).

Othman, M. & Lotfy, K. The Influence of gravity on 2-d problem of two temperature generalized thermoelastic medium with thermal relaxation. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 12, 2587–2600. https://doi.org/10.1166/jctn.2015.4067 (2015).

Lotfy, K. Two temperature generalized magneto-thermoelastic interactions in an elastic medium under three theories. Appl. Math. Comput. 227, 871–888 (2014).

Todorović, D. M. Plasma, thermal, and elastic waves in semiconductors. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 74, 582–585 (2003).

Kamel, A., Lotfy, K., Raddadi, M. H. & Elidy, E. S. A novel model on studying the interactions varying thermal and electrical conductivity with two-temperature theory in generalized thermoelastic process. Arch. Appl. Mech. 94, 2841–2857 (2024).

Raddadi, M. H., Lotfy, K., El-Bary, A. A., Mahdy, A. M. S. & Elidy, E. S. A novel model of photoacoustic and thermalelectronic waves in semiconductor material. AIP Adv. 15, 2563 (2025).

Lotfy, K. & Hassan, W. Normal mode method for two-temperature generalized thermoelasticity under thermal shock problem. J. Therm. Stresses 37, 545–560 (2014).

Lotfy, K. & Abo-Dahab, S. Two-dimensional problem of two temperature generalized thermoelasticity with normal mode analysis under thermal shock problem. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 12, 256. https://doi.org/10.1166/jctn.2015.3949 (2015).

Abo-Dahab, S. M., Lotfy, K. & Gohaly, A. Rotation and magnetic field effect on surface waves propagation in an elastic layer lying over a generalized thermoelastic diffusive half-space with imperfect boundary. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 2563 (2015).

Abo-Dahab, S. M. & Lotfy, K. Generalized magneto-thermoelasticity with fractional derivative heat transfer for a rotation of a fibre-reinforced thermoelastic. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci. 12, 1869–1881 (2015).

Mandelis, A., Nestoros, M. & Christofides, C. Thermoelectronic-wave coupling in laser photothermal theory of semiconductors at elevated temperatures. Opt. Eng. 36, 459–468 (1997).

Khalili, N. Coupling effects in double porosity media with deformable matrix. Geophys. Res .Lett. 2003, 30 (2003).

Lotfy, K. et al. Stochastic process of magneto-photo-thermoelastic waves in semiconductor materials with the change in electrical conductivity. J. Elast. 157, 1–26 (2025).

Lotfy, K. et al. A stochastic photoacoustic study influenced by white noise on thermoelastic waves in semiconductor medium. Semiconductors 58, 948–959 (2024).

Lotfy, K. et al. A novel model of stochastic photo-elasto-thermodiffusion waves interaction in semiconductors. Mech. Solids 59, 2301–2321 (2024).

Lotfy, K. The elastic wave motions for a photothermal medium of a dual-phase-lag model with an internal heat source and gravitational field. Can. J. Phys. 94, 400–409 (2016).

Gupta, M. & Mukhopadhyay, S. Stochastic thermoelastic interaction under a dual phase-lag model due to random temperature distribution at the boundary of a half-space. Math. Mech. Solids 24, 1873–1892 (2019).

Lotfy, K., Ahmed, A., El-Bary, A., El-Shekhipy, A. & Tantawi, R. S. A novel stochastic photo-thermoelasticity model according to a diffusion interaction processes of excited semiconductor medium. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 137, 1–15 (2022).

Lotfy, Kh., Ahmed, A., El-Bary, A. & Tantawi, R. S. A novel stochastic model of the photo-thermoelasticity theory of the non-local excited semiconductor medium. SILICON 15, 437–450. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-022-02021-x (2023).

Alenazi, A., Ahmed, A., El-Bary, A., Tantawi, R. & Lotfy, K. Moisture photo-thermoelasticity diffusivity in semiconductor materials: a novel stochastic model. Crystals (Basel) 13, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst13010042 (2022).

Alenazi, A., Ahmed, A., El-Bary, A., Tantawi, R. & Lotfy, K. A stochastic thermo-mechanical waves with two-temperature theory for electro-magneto semiconductor medium. Crystals (Basel) 13, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst13010082 (2023).

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University for funding this research under Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R895), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University for funding this research under Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R895), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ismail and Rizk: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation. Ahmed and El-Bary, Writing- Original draft preparation. Kh. Lotfy and Elidy: Supervision, Visualization, Investigation, Can: Software, Validation. All authors: Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rezk, E.G., Ismail, G.M., Ahmed, A. et al. A stochastic dual-phase-lag two-temperature photo-thermoelastic model for double-porosity semiconductors with initial stress. Sci Rep 15, 41466 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28079-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28079-2