Abstract

Compact neuron-specific promoters enable targeted gene expression in the brain, especially when using size-limited adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors. The human synapsin 1 gene promoter (hSyn) promoter is widely used, but the recently described Calm1 promoter (120 bp long) offers a smaller alternative with demonstrated excitatory and inhibitory neuron-specificity in animal models. Here, we compared the commonly used hSyn promoter and the compact Calm1 promoter in human iPSC-derived brain organoids using AAV reporter constructs. Our study evaluating reporter gene expression and immunohistology showed comparable performance in human neurons. Our findings suggest that the compact Calm1 promoter could be used for future central nervous system-targeted human gene therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The brain is made up of a diversity of cell types, necessitating the need for neuron-specific promoters to target gene expression to neurons for physiological studies, tract tracing, and to treat neurological diseases. However, the number of compact, neuron-specific promoters suitable for viral delivery systems like AAV—which has a packaging limit of 4.7 kb-is limited1. Neuronal promoters include hSyn (~ 0.47 kb), CaMKII-alpha (~ 1.3 kb), Thy1 (∼6.5 kb), and NSE (~ 1.5 kb), with hSyn being the most commonly used promoter for AAV-mediated gene expression in neurons due to its smaller size2,3,4,5,6. Recently, Wang et al.4 introduced a new compact promoter, Calm1 (120 bp), derived from the endogenous human CALM1 gene, achieving the highest efficiency of all tested candidates and showing that it drives expression specifically in excitatory and inhibitory neurons across rodent and non-human primate models. However, for new neuron-selective promoters like Calm1 to be applied in human therapeutic contexts, they must undergo careful validation in the more complex cellular environments present in the human brain to ensure no undesired off-target activity. This novel promoter is significantly smaller than the hSyn promoter and offers a significant advantage when designing gene therapy constructs with a confined cargo size. Despite its potential, the efficacy and specificity of the Calm1 promoter in human neuronal cells has not yet been validated. To address this issue, we performed a proof-of-concept study using AAV reporter constructs to compare the performance of the hSyn and Calm1 promoters in human iPSC-derived brain organoids. This system models the mid-fetal cortical human brain7, representing a crucial stage for brain formation during which both upper- and lower-layer neurons are formed.

Results

Calm1 promoter drives reporter gene expression comparable to hSyn in human brain organoids

Recently, Wang et al. introduced a new compact Calm1 promoter as a neuron-specific driver of gene expression, demonstrating its efficacy in vivo, in both mouse and non-human primate models. Their data further show stable long-term expression and successful in vivo gene editing using a single SpCas9-AAV construct 4, suggesting that Calm1 is a promising alternative for AAV-mediated gene delivery specifically targeting neuronal cells in the brain. However, its performance in human brain cells was not evaluated.

We generated an AAV reporter construct where GFP expression is driven by the Calm1 promoter and evaluated its activity in human iPSC-derived cortical brain organoids. Using the same reporter backbone, we directly compared this Calm1 vector to a construct driven by the commonly used hSyn promoter. The Calm1 promoter is ~ 70% smaller than hSyn (Fig. 1a, b). Organoids were transduced on day 73 with virus for three days, and RNA was collected from individual organoids two weeks post-transduction (Fig. 1c). GFP expression levels were quantified via qPCR and compared to untreated organoids as a negative control. Both Calm1- and hSyn-driven constructs showed significantly increased GFP expression relative to untreated controls. No significant difference was observed between the two promoters, whether normalized to EIF4A2 or NEUN (RBFOX3), indicating that both promoters drive gene expression at comparable levels (Fig. 2a, b). Although previous reports suggest that AAV transduction may cause a reduction in NEUN immunoreactivity8, our data show no significant difference in NEUN expression (Fig. 2C) or immunoreactivity fluorescence intensity [ctrl = 1756 ± 815, hSyn = 1303 ± 119, Calm1 = 984 ± 188 (SEM)] across conditions.

AAV reporter constructs and experimental workflow. (a, b) Schematic of AAV reporter constructs expressing GFP under the control of either the hSyn promoter or the Calm1 promoter, using an identical backbone. (c) Overview of experimental workflow, including iPSC-derived brain organoid generation, AAV transduction and subsequent analysis. ITR = inverted terminal repeat; hSyn = human synapsin 1 promoter. Calm1 = compact promoter derived from the CALM1 gene4. eGFP = enhanced green fluorescent protein. hGH = human growth hormone polyadenylation signal. iPSCs = induced pluripotent stem cells.

Quantification of GFP expression in transduced brain organoids via qPCR. (a, b) qPCR-based analysis of GFP expression driven by hSyn or Calm1 promoters, normalized to EIF4A2 (a) or NEUN (b). (c) NEUN expression levels across all conditions. Untreated organoids served as control (ctrl). n = 4/4/4. ns = not significant. *p ≤ 0.05; Mann–Whitney test.

Comparable transduction efficiency of Calm1 and hSyn promoters in brain organoids

To further evaluate the performance of the Calm1 promoter relative to hSyn, we performed immunofluorescence staining of brain organoid sections (Fig. 1c). This enabled us to assess the number and spatial distribution of GFP-positive cells, as well as to compare GFP fluorescence intensity at the single-cell level. Consistent with our qPCR results, we observed GFP-expressing cells around the periphery of both Calm1- and hSyn-transduced organoids with a very similar spatial distribution, but not in untreated controls (Fig. 3a, b). After defining a cutoff for GFP signal intensity (red line in Fig. 3c), we quantified the proportion of GFP-positive cells per section and found again no significant difference between the two conditions, indicating comparable transduction efficiency (Fig. 3c, d).

Immunofluorescence based analysis of GFP expression in brain organoids. (a, b) Representative images of GFP and DAPI staining in organoid sections, comparing untreated controls (ctrl) to AAV-transduced organoids expressing GFP under the control of either the hSyn or Calm1 promoter (dashed line represents organoid border). (c) Analysis of relative GFP intensity in untreated (DAPI⁺GFP−) and transduced (DAPI⁺GFP⁺) organoids defining a cut-off for GFP quantification. (d) Quantification of transduction efficiency based on the proportion of GFP⁺ expressing cells (DAPI⁺GFP⁺; n = 4/4). Scale bars: 200 µm/ 50 µm (a) and 50 µm (b). ns = not significant. Mann–Whitney test.

Assessment of neuronal expression and promoter strength.

To assess neuronal expression of the Calm1 promoter in human brain organoids, we performed immunostaining using a NEUN (RBFOX3) antibody, a well-established neuronal marker (Fig. 4a, b)9,10. This allowed us to validate neuron-targeted expression driven by Calm1 and compare to the hSyn promoter by quantifying the proportion of GFP and NEUN positive cells. For this analysis, we first established a cutoff to define NEUN positive cells based on fluorescence intensity in untreated organoids and both experimental conditions (Fig. 4c, red line). By applying this threshold, we aimed to focus our quantification on cells with high expression of NEUN. In organoids transduced with the hSyn construct, ~ 90% of GFP-positive cells also expressed NEUN (GFP+NEUN+), with only a small fraction of GFP-positive and NEUN-negative cells (GFP+NEUN−) (Fig. 4d, e). A comparable result was obtained for the Calm1 construct, indicating high neuronal expression and no significant difference in targeting efficiency between the two promoters.

Assessment of promoter specificity in AAV-transduced brain organoids. (a, b) Representative images of GFP, NEUN and DAPI immunofluorescence staining in organoid sections transduced with AAVs expressing GFP under the control of either the hSyn or Calm1 promoter (dashed line represents organoid border). (c) Definition of NEUN⁺ cut-off based on ranked NEUN fluorescence intensity across all nuclei per section (low to high; four sections per condition). (d, e) Quantification of the proportion of GFP⁺ & NEUN⁺ and GFP⁺ & NEUN− nuclei in organoids transduced with either hSyn- or Calm1-driven reporters (n = 4/4). ns = not significant. Mann–Whitney test. Scale bars: 500 µm (a) and 50 µm (b).

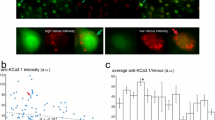

We next analyzed the relative fluorescence intensity of GFP-positive cells as a proxy for promoter strength. Quantification of the average fluorescence intensity revealed a slight but significant reduction in organoids transduced with the Calm1-driven reporter compared to hSyn, suggesting moderately weaker promoter activity in this context (Fig. 5a). Frequency distribution analysis of GFP intensity across all GFP-expressing cells revealed a higher proportion of low-intensity cells and fewer high-intensity cells in the Calm1 condition, further suggesting that Calm1 is slightly weaker than hSyn in human neurons (Fig. 5b). To explore this finding in more detail, we analyzed fluorescence intensity within the GFP⁺NEUN⁺ and GFP⁺NEUN− subpopulations. The GFP⁺NEUN⁺ cells, which represent ~ 90% of all GFP-positive cells in both conditions, showed a similar reduction in fluorescence intensity in the Calm1 group (Fig. 5c). This result suggests a slightly lower promoter strength overall in human neuronal cells. This reduction was not observed in the GFP⁺NEUN− subpopulation (Fig. 5d).

GFP intensity in NEUN+ cells transduced with each vector. (a) Quantification of average relative fluorescence intensity of all identified GFP-expressing cells per organoid in AAV-transduced samples. (b) Frequency distribution analysis of relative GFP intensity across all GFP⁺ cells for each condition. (c, d) Analysis of relative fluorescence intensity within GFP⁺NEUN⁺ (c) and GFP⁺NEUN− (d) cell-subpopulations. n = 4/4. ns = not significant; *p ≤ 0.05; Mann–Whitney test.

Discussion

Our data demonstrates that the compact Calm1 promoter drives efficient neuronal transgene expression in human iPSC-derived brain organoids at levels comparable to the commonly used hSyn promoter. These findings are consistent with a recent study where Calm1 promoter performance was evaluated in vivo in rodent and non-human primate models4. Here we assessed expression at a 2-week time point post AAV transduction. Previous work from Wang et al., 20234, described stable Calm1-driven expression for up to six months in mice via intracerebroventricular or intravenous AAV delivery, indicating its potential for stable long-term expression. Future studies are needed to confirm similar stability in human neuronal systems and would benefit from including additional capsid variants to improve transduction efficiency in human tissue to optimize delivery and enhance neuronal expression. We focused on the use of AAV2, which shows relatively strong transduction efficiency in human neurons11.

We found that the Calm1 promoter showed slightly reduced fluorescence intensity compared to hSyn, but this decrease in signal strength did not compromise neuronal expression, when evaluated using the neuronal marker NEUN. This reflects a pattern observed in other promoter designs, where reducing size may limit the number of regulatory elements, and that could potentially impact transcriptional strength in cell- and species-dependent contexts4,12. Furthermore, different promoters may influence mRNA processing via the recruitment of promoter-specific factors in different ways, which could affect transcript fidelity and may vary depending on cellular context and species. While slightly weaker expression may be less of a concern for gene silencing or other applications where modest expression levels are sufficient, therapeutic strategies requiring high-level expression, such as gene replacement, may need to account for this difference13. Nevertheless, as our data demonstrates, Calm1 provides robust transgene expression in human neurons. The compact size of Calm1 of 120 bp offers a clear advantage for AAV-based applications where vector space is limited and may also help to uncover critical regulatory elements, underlying neuron-specific gene expression.

The small GFP+ NEUN⁻ cell population identified for both constructs may include immature neurons and progenitors with lower NEUN levels7. Given that the organoid differentiation protocol used in this study is well-established and generates both excitatory and inhibitory neurons7, we speculate that the Calm1 promoter drives neuronal expression across these subtypes. This is in line with previous in vivo findings demonstrating Calm1 activity in both excitatory and inhibitory neurons in rodent and non-human primate brains4. Future work using more mature organoids, incorporating other cell types, alternative models, and additional markers will be essential to fully evaluate Calm1 promoter specificity across various human cell types. Overall, the Calm1 promoter represents a promising alternative to the hSyn promoter for gene delivery strategies requiring neuronal targeting in animal models and in the future development of clinical interventions for brain disorders.

Material and methods

Generation of GFP-reporter constructs

The AAV2-hSyn-eGFP reporter construct (Addgene #50465, a gift from Bryan Roth) served as the backbone for generating the AAV2-Calm1-eGFP construct. A gBlock containing the 120 bp Calm1 promoter, sourced from Addgene plasmid sequence #213971 (deposited by the Zhonghua Lu Lab), was synthesized and amplified using primers introducing MluI (5′) and BamHI (3′) restriction sites. Both the backbone and the amplicon were digested and subsequently ligated.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

RNA extraction from single organoids was performed using the Direct-zol RNA Microprep Kit (Zymo Research, #R2060) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, individual organoids were washed in PBS and dissociated in 400 µL of TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, #15596026) by pipetting, followed by centrifugation at maximum speed. The supernatant was transferred onto the spin column and centrifuged at 16 000 × g. DNase I treatment was performed for 15 min. After wash steps, RNA was eluted in RNase-free water and the concentration was determined using the NanoDrop (ND-1000). Subsequently, cDNA was generated via reverse transcription using SuperScript IV VILO (Invitrogen, #11766050). qPCR was performed using SsoAdvancedUniversal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, #1725271) on a QuantStudio5 system (Applied Biosystems). All primers used are listed in Table 1. Data analysis was performed using the ∆∆Ct method.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) production

AAV production was performed according to established protocols14,15. Briefly, 293T cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 3.5 × 105 cells per well and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, #11995065) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). On the next day, each well was co-transfected with 800 ng of pAd-DELTA F6 helper plasmid, 400 ng of AAV2 serotype plasmid, and 400 ng of AAV2-hSyn-eGFP or AAV2-Calm1-eGFP using Fugene6 (Promega, #E2691). One day post-transfection, the medium was replaced with DMEM containing 1% GlutaMAX (Gibco, #11960044; #35050061) and 10% FBS. 2 days after the media change, 800 μl of medium was collected, filtered through 0.45 μm spin filters (Costar, #8162), by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 1 min. The virus-containing flow-through was stored at 4 °C until use, within 2 weeks of collection.

Organoid generation, culture and AAV treatment

Human cortical brain organoids were generated following previously published protocols7,16,17, with modifications as described below. On day 0, 9000 human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs; line 1535-2) were plated per well in 96-well V-bottom plates (Sbio Japan, #MS9096VZ) to initiate aggregation. Cells were dissociated into single cells and reaggregated in mTeSR + medium (STEMCELL Technologies, #100-0276).

On day 1, Cortical Differentiation Medium I (CDM I) was introduced to promote neuroectodermal induction while inhibiting mesodermal and endodermal lineages. CDM I consisted of Glasgow Minimum Essential Medium (Glasgow-MEM; ThermoFisher Scientific, #11710-035) supplemented with 20% KnockOut Serum Replacement (ThermoFisher Scientific, #10828-028), 1 mM sodium pyruvate (ThermoFisher Scientific, #11360-070), 0.1 mM MEM non-essential amino acids (MEM-NEAA; ThermoFisher Scientific, #11140-050), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (ThermoFisher Scientific, #21985023), and 100 U/mL penicillin with 100 μg/mL streptomycin (ThermoFisher Scientific, #15140122).

To promote neural induction, two small-molecule inhibitors were applied from day 0 to day 15: IWR-1 (Millipore, #68,669), a WNT pathway inhibitor, at 3 μM, and SB431542 (STEMCELL Technologies, #100-1051), a TGF-β pathway inhibitor, at 5 μM. On day 1, concentrations were temporarily increased to 4 μM for IWR-1 and 6.66 μM for SB431542. To support early-stage cell survival, the ROCK inhibitor Chroman-1 (MedChem Express, #HY-15392) was added at a final concentration of 100 nM on days 0, 1, and 3.

On day 18, aggregates were transferred to ultra-low attachment plates (ThermoFisher Scientific, #12–566-438) and cultured in Cortical Differentiation Medium II (CDM II) under constant orbital agitation (~ 80 rpm), with medium changes every three days. CDM II consisted of DMEM/F12 (ThermoFisher Scientific, #11330-032) supplemented with 2 mM GlutaMAX (ThermoFisher Scientific, #35050-061), 1% N2 supplement (Life Technologies, #17502-048), 1% Chemically Defined Lipid Concentrate (ThermoFisher Scientific, #11905-031), 0.25 μg/mL fungizone (ThermoFisher Scientific, #15290-018), and 100 U/mL penicillin with 100 μg/mL streptomycin (ThermoFisher Scientific, #15140122).

On day 35, organoids were transferred to spinner flasks (Corning, #3152) and maintained in suspension at ~ 56 rpm in Cortical Differentiation Medium III (CDM III), with medium changes performed once per week. CDM III contained DMEM/F12 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 5 μg/mL heparin (Sigma, #H3149), and 1% Matrigel (Corning, #354234).

On day 70, individual organoids were transferred to Cortical Differentiation Medium IV (CDM IV), which supports long-term culture and promotes neuronal maturation with medium changes once a week. CDM IV consisted of CDM III supplemented with B27 supplement (ThermoFisher Scientific, #17504-044) and 2% Matrigel (Corning, #354234).

Prior to transduction on day 73, organoids were transferred to 24-well plates (Corning, #3524), where they were transduced with adeno-associated virus (AAV) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 × 1010 viral genomes (vg) per organoid. A media change was performed 72 h post-transduction, and the organoids were subsequently cultured for an additional 14 days, with feeds every three days, reaching a final age of 87 days.

Cryosectioning and immunocytochemistry

Organoids were immersion-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, washed three times for 5 min with PBS, and immersed in 30% sucrose solution overnight at 4 °C. The next day, they were embedded in tissue freezing medium (TFM, #72592) and sectioned at 14 μm thickness using a cryostat (CryoStar NX50, Thermo Fisher Scientific)18. Sections were collected on Superfrost Plus slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #12-550-15), dried for 15 min, and permeabilized with 0.01 M PBST (0.2% Triton X-100). Blocking was performed for 1 h using 5% normal donkey serum (NDS) in PBST. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies: guinea pig anti-NEUN (1:800, #ABN90P, EMD Millipore) and rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000, #NB600-386, Novus Biologicals). The next day, sections were washed with PBST and incubated for 1 h with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit (1:1000; #A21206, Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated anti-guinea pig (1:1000; #A11075, Invitrogen), and DAPI (1:40000 #D1306, Invitrogen). Lastly, sections were mounted using FluoroGel (#17985-10) and imaged with the VS200 Slide Scanner (Olympus).

ImageJ based quantification

A custom ImageJ macro pipeline was used to identify nuclei and relative fluorescence intensity for all used channels in organoid sections. The DAPI-channel was used to identify and define all nuclei, regions of interest (ROIs) for each image. First a binary image was created, then converted to a mask with usage of the watershed-function. Subsequently, using this mask, the fluorescence intensity and the number of nuclei for the green and the red channel were measured separately. For the control group (ctrl, untreated organoids), nine sections from three individual organoids were quantified. For each experimental group (hSyn, Calm1), four AAV-treated organoids were analyzed per group, and a minimum of 10 sections per organoid were quantified.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism was used for statistical analysis, and all results are presented as mean ± SEM. Non-significant differences are indicated as ‘ns’ and differences were considered statistically significant when *p ≤ 0.05; A one-tailed, non-parametric, unpaired Mann–Whitney test was used for comparisons between two groups.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dong, B., Nakai, H. & Xiao, W. Characterization of genome integrity for oversized recombinant AAV vector. Mol. Ther. 18, 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/mt.2009.258 (2010).

Kugler, S., Kilic, E. & Bahr, M. Human synapsin 1 gene promoter confers highly neuron-specific long-term transgene expression from an adenoviral vector in the adult rat brain depending on the transduced area. Gene Ther. 10, 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.gt.3301905 (2003).

Finneran, D. J. et al. Toward development of neuron specific transduction after systemic delivery of viral vectors. Front. Neurol. 12, 685802. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.685802 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. An ultra-compact promoter drives widespread neuronal expression in mouse and monkey brains. Cell Rep. 42, 113348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.113348 (2023).

Hosaka, M., Hammer, R. E. & Sudhof, T. C. A phospho-switch controls the dynamic association of synapsins with synaptic vesicles. Neuron 24, 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80851-x (1999).

Shinohara, Y., Ohtani, T., Konno, A. & Hirai, H. Viral vector-based evaluation of regulatory regions in the neuron-specific enolase (NSE) promoter in mouse cerebellum in vivo. Cerebellum 16, 913–922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-017-0866-5 (2017).

Velasco, S. et al. Individual brain organoids reproducibly form cell diversity of the human cerebral cortex. Nature 570, 523–527. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1289-x (2019).

Costa-Verdera, H. et al. AAV vectors trigger DNA damage response-dependent pro-inflammatory signalling in human iPSC-derived CNS models and mouse brain. Nat. Commun. 16, 3694. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-58778-3 (2025).

Herculano-Houzel, S. & Lent, R. Isotropic fractionator: A simple, rapid method for the quantification of total cell and neuron numbers in the brain. J. Neurosci. 25, 2518–2521. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4526-04.2005 (2005).

Mullen, R. J., Buck, C. R. & Smith, A. M. NeuN, a neuronal specific nuclear protein in vertebrates. Development 116, 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.116.1.201 (1992).

Drouyer, M. et al. Enhanced AAV transduction across preclinical CNS models: A comparative study in human brain organoids with cross-species evaluations. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 35, 102264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2024.102264 (2024).

Haery, L. et al. Adeno-associated virus technologies and methods for targeted neuronal manipulation. Front. Neuroanat. 13, 93. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnana.2019.00093 (2019).

Abordo-Adesida, E. et al. Stability of lentiviral vector-mediated transgene expression in the brain in the presence of systemic antivector immune responses. Hum. Gene Ther. 16, 741–751. https://doi.org/10.1089/hum.2005.16.741 (2005).

Bazick, H. O., Mao, H., Niehaus, J. K., Wolter, J. M. & Zylka, M. J. AAV vector-derived elements integrate into Cas9-generated double-strand breaks and disrupt gene transcription. Mol. Ther. 32, 4122–4137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2024.09.032 (2024).

Gao, Y. et al. Plug-and-play protein modification using homology-independent universal genome engineering. Neuron https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2019.05.047 (2019).

Velasco, S., Paulsen, B. & Arlotta, P. Highly reproducible human brain organoids recapitulate cerebral cortex cellular diversity. V.1 https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.2.9542/v1 (2019).

Uzquiano, A. et al. Proper acquisition of cell class identity in organoids allows definition of fate specification programs of the human cerebral cortex. Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2022.09.010 (2022).

Qian, X. et al. Sliced human cortical organoids for modeling distinct cortical layer formation. Cell Stem Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2020.02.002 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Microscopy was performed at the UNC Hooker Imaging Core Facility.

Funding

M.J.Z. is supported by grants from the NIH-NINDS (R21NS142886), NINDS (R01NS144331), NINDS (UG3NS137515), and NIEHS (R35ES028366). UNC Hooker Imaging Core Facility is supported in part by P30 CA016086 Cancer Center Core Support Grant to the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.K. planned and performed the experiments and analyzed the data. Organoids were provided by M.Y. and J.L.S. Cloning procedures were carried out by I.K. and T.E.R. The original manuscript was written by I.K. with contributions from M.J.Z. and reviewed by J.L.S. and M.J.Z.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Klockner, I., Yeturi, M., Rust, T.E. et al. Compact Calm1 promoter enables AAV mediated neuron-targeted expression in human iPSC-derived brain organoids. Sci Rep 15, 44450 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28162-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28162-8