Abstract

Diapers are essential for managing incontinence in infants, but delayed diaper changes can lead to discomfort, skin rashes, and infections. Previous research has focused on ultra-high frequency (UHF) radio-frequency identification (RFID) moisture sensors with limited read ranges and binary (dry/wet) detection capabilities. This study proposes a textile-based UHF RFID bowtie antenna using high conductive material as a passive sensor for diaper moisture sensing. The purpose of the sensor is to detect and measure moisture levels in infant diapers, providing immediate notifications to parents and caregivers. The sensor, measuring 78 mm × 32 mm × 0.09 mm, offers multilevel wetness detection (0–60 ml) and achieves a maximum read distance of 12.1 m (dry) and 3.3 m (wet) within the US UHF RFID passband (902–928 MHz), which, to the best of our knowledge, represents the highest reported read range among passive UHF RFID diaper moisture sensors in the scientific literature. Additionally, the sensor is cost-effective, reusable, flexible, and can seamlessly attach to reusable diapers, making it an ideal solution for practical and sustainable diaper monitoring applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of diapers has revolutionized newborn hygiene practices all around the world, and the baby diapers market size is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.6% from 2025 to 20301. Currently, diapers with wetness indicators are sold in the market, appealing to modern parents who seek both convenience and responsibility. The wetness indicator is used to determine whether a diaper change is needed. It works as a visual-based indicator that can change the colour based on the moisture or acidity of urine in the diaper. The substance “Bromophenol Blue” in the indicator will change to blue colour when the diaper is in wet condition2. However, the wetness indicator requires the caregivers or parents to physically check multiple times to see whether there is a colour change. The longer a baby is exposed to a wet diaper, the higher the risk of skin breakdown, potentially leading to life-threatening infections3. To address this issue, both battery-operated4,5 and battery-free6 moisture sensors have been developed. These sensors monitor diaper wetness and transmit data wirelessly via microcontrollers, which can reduce diaper-related infections. However, the rigidity of microcontrollers can cause discomfort for infants.

Recent research has focused on wireless moisture sensors by utilizing ultra-high frequency (UHF) radio-frequency identification (RFID) technology7,8,9. UHF RFID tags have been widely used as communication devices for logistics, medical, and retail10,11,12,13. It uses radio waves to enable automatic identification and data capture technology. These systems comprise a transponder (with a microchip connected to an antenna) and an interrogator (or reader). The RFID reader sends radio waves to activate the tag, which then processes the signal into usable data. Notably, the antenna in an RFID system can also function as a sensor, detecting changes in its environment14,15. This dual functionality allows the potential of RFID technology in smart diaper applications.

There are two types of UHF RFID: passive and active. Passive RFID tags rely on external signals for power, while active tags have an independent power source, such as a battery, to operate the microchip. Among UHF RFID systems, passive RFID is preferred due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and lack of reliance on an independent power source. Integrating UHF RFID into household applications, such as smart diapers, represents an exciting frontier in technology-driven caregiving. One author uses an existing passive UHF RFID tag (Monza E64 Viper tag) which is made of aluminium and paper. The problem with this tag is that it requires a tedious process of attaching two tags to the diaper16. This sensor is impractical for use with reusable cloth diapers due to the rigidity and incompatibility in attaching to the diaper. Furthermore, the read range of this sensor is only 3.6 m for baby diapers. To improve wearability, an ink-fabric RFID tag is used to measure the moisture state of the diaper17. However, the use of silver ink is high cost. Other authors have introduced a hybrid sensor incorporating both hydrogel and metal components18. The sensor is embedded between the absorption layer and the bottommost layer, which is located inside the disposable diaper. However, the read range of this sensor is low, which is 1 m, and the wearability of the diaper is reduced due to the metal component of the sensor.

Textile antennas have gained significant attention in recent years due to their flexibility and compatibility with wearable applications. Unlike conventional rigid antennas, textile-based designs can conform to the contours of the human body, making them particularly suitable for integration into garments, medical devices, and smart textiles19,20. They are typically fabricated using conductive fabrics21,22, embroidery techniques23, or printed conductive inks24, combined with textile substrates such as cotton, polyester, or felt. These antennas offer advantages such as comfort and low-cost fabrication, while maintaining acceptable electromagnetic performance for wireless communication.

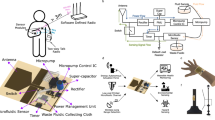

In this paper, we proposed a passive-based (battery-free), flexible, and reusable textile-based UHF RFID diaper moisture sensor. An external RFID reader wirelessly activates the tag and monitors the power it receives from it. When there is a presence of urine, it will affect the antenna impedance and eventually lower the read distance at the intended frequency. This will be further discussed in the next section. Once the RFID reader detects a change in the wetness level of the diapers from the preset threshold, it will trigger an alarm to the caregivers or parents via the Internet. To prevent the antenna from drastically losing radiation efficiency due to its proximity to the human body (mainly consisting of high-loss water), the antenna is first attached on the cotton insert of the reusable diaper before being inserted into the diaper, with the tag facing outwards (does not come into direct contact with the human body). This creates a gap that can enable the antenna to work efficiently with low/negligible harm to the human body. The proposed antenna offers several key advancements, including an extended read range, multilevel moisture detection capabilities, and improved wearability. With its extended read range, the sensor can accurately detect moisture levels from a distance, providing timely notifications for diaper changes. The multilevel moisture detection feature enables parents or caregivers to monitor varying degrees of diaper saturation, offering more nuanced insights into the infant’s condition. Additionally, the use of textile materials simplifies the fabrication process, as the tag can be manufactured using automated cutting methods, and enhances the comfort and wearability of the antenna for diaper users. This paper is structured in the following way. First, the antenna configuration is discussed in detail, followed by analyzing some of the important design parameters. Then, the antenna fabrication process is elaborated. Finally, the characteristics and performances of the moisture-sensing UHF antenna are explored.

Antenna configuration and design procedure

Figure 1a, b provide a comprehensive structural overview of the proposed textile antenna. It is excited by a UCODE 9 microchip with a read sensitivity of -21.85 dBm and a chip impedance of 10 – j191 Ω25. The antenna impedance needs to be nearly equal to the conjugate chip impedance to achieve resonance within the regulated US RFID band frequencies (902 MHz – 928 MHz) and below − 10 dB of reflection coefficient. This regulated frequency range is designated for RFID applications, ensuring compliance with communication standards and minimizing interference with other wireless systems. This precise impedance matching is critical for efficient energy transfer and reliable operation in practical sensing environments.

The textile components of the antenna are carefully selected to balance functionality and comfort. The conductive area (grey in colour) of the antenna was fabricated using a commercial nickel-copper coated polyethylene terephthalate (PET) conductive fabric (thickness = 0.09 mm; electrical conductivity = 5.34 × 105 S/m) (bought from Taobao, an online shipping platform in China26. This conductive fabric is first adhered to the microfibre polyester substrate (blue) (thickness, h1 = 1 mm; εr = 1.55; tan σ = 0.009), subsequently attaching to the cotton insert (yellow in colour) (thickness, h2 = 10 mm; εr = 1.5; tan σ = 0.05)27, which serves as the foundational substrate. The cotton insert is the absorbent insert of a reusable pocket-type baby diaper. This ensures compatibility with the diaper structure, as the cotton insert is specifically designed to remain in close contact with moisture, making it an ideal material for moisture-sensing applications. Lastly, the UCODE 9 microchip, pre-soldered onto a bonding pad with a pre-etched 0.15 mm gap, was then soldered to the antenna with the matching circuit. The final optimized parameters of the antenna are provided in Table 1.

Here, the T-matched folded bowtie half-wavelength dipole antenna structure28 is selected for the diaper moisture sensing application, primarily due to its visually appealing bowtie shape and its ease of fabrication for a single-layer design. The resonant frequency, fr, of a T-matched folded bowtie half-wavelength dipole antenna can be obtained using the following equations28,29,30,31. :

The half length can be obtained:

In Eqs. (1)–(2), the relative permittivity of the substrate is denoted as εr, c represents the speed of light, and Ld and Cd represent the effective inductive and capacitive of the bowtie dipole. These equations were utilized to create an initial design for the bowtie antenna, which was subsequently refined and finalized through numerical simulations. The simulated resonant electric field, magnetic field, and surface current at 917 MHz are shown in Fig. 2a–c, exhibiting characteristics typical of a half-wavelength dipole. The electric and magnetic fields confirm effective radiation at resonance, while the surface current is strongest along the bowtie arms and bridge, indicating the primary radiating regions of the antenna.

Parametric study

Parametric analysis was conducted to investigate the effects of geometrical parameters on the resonant frequency and corresponding input impedance of the proposed textile antenna. First, the effect of the length of the antenna (S) was studied. As illustrated in Fig. 3a, increasing the bowtie arm length S causes the resonant frequency to shift down. The shift in resonant frequency is attributed to the impedance mismatch with the chip impedance (horizontal dotted line), as observed in the corresponding input impedance graph. A similar decreasing trend is also observed, as shown in Fig. 3b, when the bowtie bridge length L2 is decreased. It was also found in the simulation that changing bowtie width W1 has very little effect on the resonance (Fig. 3c), as the surface currents on the vertical edges are significantly weaker, as can be seen in Fig. 2c. Hence, this parameter is mainly used for fine-tuning the resonant frequency. Next, the bowtie bridge width W4 is increased with a step size of 1 mm, and it can be observed that the resonant frequency shifts from 878 MHz to 949 MHz at an average rate of 35 MHz/mm, as observed in Fig. 3d. Among the parameters analyzed, W4 exhibited the highest sensitivity to frequency changes. All reflection coefficient curves are below the − 10 dB reflection coefficient threshold (horizontal dotted line), showing good impedance matching between the antenna and the chip.

Additionally, since moisture has a strong dielectric loading effect towards the antenna, the location of moisture near the particular antenna parameter has a specific influence on the antenna performance. For example, moisture concentrated near the bowtie bridge section may impact parameters L2 and W4, whereas moisture near the bowtie arms influences parameters S and W1. These cause shifts in resonant frequency that align with the sensitivity of these parameters as observed in the parametric analysis. This highlights the importance of understanding the interplay between the antenna geometry and the moisture distribution in the substrate material. A detailed analysis of these effects, including the dielectric loading influence on both resonant frequency and impedance behavior, will be elaborated upon in a later section.

Fabrication processes

Figure 4 shows the fabrication processes of the proposed textile antenna. To produce the antenna, the conductive fabric was cut with the precise pattern programmed in the Silhouette Studio software for the electronic paper cutting machine (Silhouette Portrait, United States, Mechanical resolution: 0.025 mm), which has been used previously in our previous works32,33, as shown in Fig. 4a,b. This cutting allows for avoiding the commonly used etching process, and it is a faster and cheaper technology compared to the classical printed circuit board (PCB) manufacturing process (photo-lithography mask fabrication). The cut-out antenna was then secured on the microfibre cloth with the aid of double-sided thermo-adhesive non-woven adhesive fabric, as shown in Fig. 4c. The adhesive fabric can be obtained easily from any local art store. To secure the antenna with the microfibre, a hotplate with a temperature of around 135 °C was applied to melt the adhesive for about 10 s while applying a suitable pressure to ensure consistent adhesion, as shown in Fig. 4d. Then, the antenna attached to the microfibre is removed from the hotplate and allowed to cool down to room temperature for 2 minutes. Then, in Fig. 4e–g, a UCODE 9 microchip with a pre-soldered pad was soldered carefully onto the antenna’s matching circuit, before sewing it onto the cotton insert (350 × 135 mm2). The melting point of PET of the conductive fabric (250–265 °C)34 is sufficient to withstand the temperature of soldering (~ 200 °C). However, extra care was taken to prevent direct contact between the soldering tip and the fabric to avoid localized overheating. To protect the microchip from moisture, a layer of silicone conformal coating (MG-Chemicals 422B Silicone modified conformal coating) was applied over it, which has minimal effect on the antenna performance.

Fabrication processes of the proposed textile antenna: (a) Antenna pattern is cut using Silhouette Portrait. (b) The antenna is obtained. (c) The adhesive fabric is placed on the microfibre cloth. (d) The adhesive fabric is melted using the hot plate to adhere the antenna onto the microfibre cloth. (e) The UCODE 9 chip is soldered onto the textile antenna. (f) Fabricated prototype. (g) The textile antenna is sewn onto the cotton insert.

Results

Measurement setup

The proposed textile antenna measurements were conducted using the Voyantic Tagformance Pro inside an anechoic chamber over a frequency range of 800 MHz – 1 GHz with a 0.5 MHz step size35. The measurement setup of the antenna is shown in Fig. 5a. Then, the antenna is placed on the foam stand (εr ~ 1) at a constant distance (d = 52 cm) from the reader antenna. The foam stand is used to minimize backside reflections and the loading effect towards the antenna. The distance, d, is carefully selected based on the farfield distance (3):

where D is the antenna dimension, and λ is the wavelength of the respective frequency28.

A linearly polarized reader antenna with an 8 dBi gain is used to provide the signal power that is needed to excite and detect the antenna under test (AUT). Calibration was performed on the system before measurement by using a reference broadband dipole antenna to calculate the path loss (Ll) (including both free-space loss and cable loss). During the calibration, the reader antenna increases its transmitted power gradually until sufficient backscattered power is received from the reference AUT. The threshold power (Pt) is the transmitted power that is required to sufficiently switch on the AUT. The power received by the AUT, Ptag, can be calculated as Ptag = Ll × Pt. The realized gain of the AUT, can therefore be approximated using Gr [dBi] = Pchip [dBm] / (Ll × Pt) [dBm], where Pchip is the chip sensitivity (-21.85 dBm), which is the minimum received power needed to power up and read the chip on the AUT. A maximum equivalent isotropic radiated power (EIRP) of Pr = Ptx · Gtx = 3.28 W is used in this measurement, where Ptx is the reader’s transmitted power and Gtx = 8 dBi is the reader’s antenna gain. From the derivation of the Friss transmission equation, the maximum read distance, R, of the AUT, can be calculated using (4)36.

After the calibration process, the reference AUT is then replaced by the proposed textile antenna for measuring realized gain and read distances. In countries that allow 4 W EIRP, the measured read distance results should be multiplied by 10.43%37.

Realized gain and radiation pattern

The measured realized gains were compared with their simulated counterparts obtained from the CST Microwave Studio Software. The peak realized gain, which also corresponds to the resonant frequency, is achieved when the power transfer between the antenna and the RFID chip is maximized. The textile antenna has a measured resonant frequency of 915 MHz (simulation: 917 MHz), with a corresponding measured realized gain of -3.669 dBi (simulation: -0.679 dBi), as shown in Fig. 5b. This discrepancy arises because the simulation assumes ideal conditions such as perfectly flat geometry, uniform dielectric constant, fixed substrate thickness, and highly conductive traces. In practice, the fabricated textile is porous and not perfectly planar, which causes variations in the effective permittivity, thickness, and conductor conductivity. Despite the lower realized gain observed in measurement, the results remain valid as the antenna still operates within the intended frequency band.

To measure the radiation pattern, the textile antenna is rotated about its axes according to the cutplane definitions shown in Fig. 6a,b. This allows for the characterization of the antenna’s radiation pattern in the xz-, yz-, and xy-planes, corresponding to different angular rotations defined by the spherical coordinate angles θ and φ. The read distance of the textile antenna was measured over 360⁰ with a step size of 5⁰, and compared with the simulated results, forming the radiation patterns of the xz-, yz-, and xy-planes shown in Fig. 7. Omnidirectional radiation patterns (8-shaped) have been observed in the xz- and xy-planes, being shown in Fig. 7a,c. A maximum measured read distance of 12.16 m and 12.88 m is observed at θ = 0° and 180° in the xz-plane, respectively, while it becomes 15.68 m at both φ = 0° and 180° in the xy-plane. Referring to Fig. 7b, an average measured read distance of 13.85 m can be achieved, showing uniform spatial coverage, with a minor fluctuation in the range of 12.79–15.21 m. The differences in the radiation patterns between simulation and measurement are mostly caused by unavoidable misalignments between the reader and the antenna during the measurement. Hence, a reasonably good omnidirectional feature is observed. This omnidirectional characteristic is advantageous for diaper moisture sensing applications to ensure reliable communication regardless of the orientation of the diaper or the position of the reader. This feature minimizes the need for precise alignment, making the system practical and user-friendly in real-world scenarios. It should be noted that while the measurements were conducted in anechoic chamber conditions to establish a controlled baseline, potential degradation in read range and sensing accuracy may occur in realistic environments due to multipath propagation, user movement, or the presence of multiple tags or readers. As the proposed RFID sensor is intended for infants up to 9 months old, the effects of user movement are expected to be minimal, since infants within this age range generally exhibit limited mobility.

Moisture sensing

The textile antenna (antenna with the cotton insert) is inserted into the reusable cloth diaper (diaper) for actual moisture sensing experiment. This experiment involves gradually applying standard 0.9% saline solution (0.9% NaCl in deionized water, σ = 16 mS/cm, εr ~ 74) in increments from 0 ml to 60 ml, increasing in steps of 10 ml, to the center region of the diaper. A 0.9% saline solution is used as an industry standard as a substitute for baby urine for testing under laboratory conditions38. Typically, an infant aged 1 to 9 months releases about 30 ml (max 60 ml) of discharge per event39,40. Therefore, 60 ml is selected as our upper limit in the experiment. This selection also aligns with the standard absorption tests performed in industry41,42.

Each time a set amount of saline solution is added, the antenna is allowed to stabilize for two minutes to ensure uniform moisture distribution across the diaper before recording the measurement. While the antenna’s response is instantaneous, this waiting period is necessary to ensure consistent experimental conditions. The same measurement setup, as previously described, was used. Figure 8a shows the frequency vs. read distance for different moisture levels. The read distance curves correlate with the level of moisture in the diaper. To provide a clearer indication of the moisture sensing response, Fig. 8b shows the read distance (the maximum communication range) and the power-on tag forward (the minimum power needed to activate the tag) at 915 MHz. Due to the antenna experiences additional dielectric losses and impedance mismatch, which reduce the efficiency of power transfer to the RFID chip. Consequently, the reader must supply more transmit power to activate the tag, which is reflected as an increase in the power on tag forward curve. As a result, the read distance of the antenna reduces. Both metrics are inversely related and represent the antenna’s performance at different moisture levels, though we focus more on the read distance as the primary metric for evaluation. With reference to the same figure, the read distance of the antenna dropped sharply from 12.1 m to 5.9 m, at 0 ml to 10 ml, followed by a gradual decline from 5.9 m to 3.3 m, at 10 ml to 60 ml, showing the textile antenna’s capability for multi-level moisture detection. In the initial range (0 to 10 ml), the sharp reduction in read distance is primarily due to significant changes in the substrate’s electrical properties, including increased conductivity and dielectric constant caused by the introduction of saline moisture. This rapid response to small amounts of moisture demonstrates the antenna’s high sensitivity, making it effective for detecting early stages of moisture presence. Beyond 10 ml, the changes in electrical properties occur more gradually. This results in a slower and more predictable decline in read distance, enabling the antenna to distinguish between varying levels of moisture. Such performance is ideal for detection and differentiation across a wide range of moisture levels, rather than a simple binary wet/dry assessment. These two sensitivity regions can be explained using the surface current distribution observed in Fig. 2c. The saline moisture initially accumulates near the bowtie bridge of the textile antenna upon being applied with a small amount of moisture which is the most sensitive region (yellow solid box). At higher moisture levels, the solution begins to spread outward and toward the bowtie arms, where the surface current density is lower (yellow dotted box). To further support this explanation, this behavior also aligns with the findings from the parametric analysis discussed in the previous section. Figure 9 shows the measured radiation patterns of the antenna in wet conditions for different moisture volumes (20 ml, 40 ml, and 60 ml). The patterns are presented for the xz-plane, yz-plane, and xy-plane, illustrating how increasing moisture slightly reduces the read distance but does not significantly alter the overall radiation characteristics.

To have a better insight into how the read distance of the antenna is being affected by the moisture on the diaper, additional simulations and analysis were performed using CST Microwave Studio. A cylindrical geometry representing the 0.9% saline solution (σ = 16 mS/cm, εr = 74) was defined at the center of the cotton insert, consistent with the saline placement in the experimental setup. Seawater is chosen (source: CST Microwave Studio) for simulating the 0.9% saline solution. The diameter of this cylinder was incrementally increased (r = 0, 40, 60, 80 mm) to model the increasing volume of moisture. These diameter values were determined by reverse-calculating moisture volume (V) dispersed during the experiment and the thickness of the cotton insert (h2), using the volume formula for a cylinder: V = πr2h2. It is assumed that the cotton insert fully absorbed the saline solution from the diaper. Figure 10a shows the simulated frequency vs. read distance, which correlates quite well with the measurement in Fig. 8a. Here, the saline solution acts as a dielectric loading to the antenna, increasing the effective permittivity of the cotton insert. The resulting larger effective permittivity alters the electromagnetic field distribution around the ungrounded bowtie antenna, affecting its impedance (both real and imaginary components), as shown in Fig. 10b. The equivalent circuit of the antenna is depicted in Fig. 11, consisting of a series resonator with resistance Rin, inductance Lin, and capacitance Cin. The antenna impedance equation is given by (5)43,44:

where the angular frequency \(\:{\omega\:}_{0}=1/\sqrt{{L}_{in}{C}_{in}}\) and quality factor \(\:{Q}_{0}={\omega\:}_{0}{L}_{in}/{R}_{in}\). Given that the UCODE 9 chip impedance is Zchip = 13–191j, any mismatch between Zchip and Zantenna due to moisture will affect the power transfer, which can be detected through the RFID backscatter performance, which eventually affects the read distance.

The simulations were further extended by studying three different antenna placements relative to the center of the cotton insert (Right-Center, Right-Lower, and Right-Upper), while the moisture geometry is fixed at the center of the cotton insert. The simulations were only conducted on one side as the antenna is symmetric. The corresponding changes in read distance are shown in Fig. 12a–c, which differ slightly from the trend observed in Fig. 10a, where the antenna is placed at the center. For a clearer comparison, Fig. 12d summarizes the relationship between moisture level and read distance for all four antenna placements. It is noticed that the antenna placed at center exhibits the highest sensitivity. This is because the center region plays a dominant role in current distribution and impedance matching, as indicated in the surface current distribution in Fig. 2c. These findings highlight the importance of antenna placement: positioning the antenna at the center ensures maximum sensitivity, which also corresponds to the practical urination pattern in infants. In practical implementation, the diaper’s mechanical fastening structure ensures consistent wrapping and keeps the antenna fixed at the center position, thereby maintaining measurement consistency across different uses.

Equivalent circuit of the proposed bowtie antenna44.

Bending test

For textile antenna, it is expected to be deformed or conformed to uneven human body surfaces during operation45. To verify that the proposed antenna maintains its resonant frequency in the intended frequency band when subjected to bending, investigation is conducted on the proposed antenna under different degrees of structural deformations. The experiments were performed in free space by attaching the antenna onto polystyrene cylinders of different diameters (D = 76, 102, 127 mm) using adhesive tape. Since the antenna is positioned perpendicularly to the diaper, bending along the x-axis is the most representative scenario in practical use. Hence, the respective read ranges being bent along the antenna’s x-axis on the three different cylinders are shown in Fig. 13. The measured read ranges show only slight or negligible frequency shift, indicating that the proposed antenna is stable under different bending conditions.

Integration of diaper on a baby doll

Figure 14a,b show the cloth diaper in unfolded and folded conditions, respectively. The diaper can be folded as the textile antenna is flexible. Next, the cloth diaper is worn with a baby doll, as shown in Fig. 14c. The inclusion of the baby doll simulates a more realistic usage scenario by accounting for the potential effects of the doll’s body on signal propagation. All these conditions were measured in the anechoic chamber, as shown in Fig. 15a,b.

The maximum read distance of the textile antenna at 915 MHz under various conditions with and without involving a baby doll is shown in Fig. 16. When the baby doll is not present, the read distance for a dry cloth diaper in the “Unfolded” condition is 13.1 m and the “Folded” condition is 14.4 m. Since the width of the antenna is less than half of the length, bending of the antenna along its width (x-axis) has minimal effect towards the antenna performance. However, this slight improvement in the “Folded” scenario could be attributed to the stronger radiation signal at θ = -60⁰ to -90⁰, with reference to Fig. 7b. With the baby doll and the diaper in a dry state, the read distance is 12.8 m. When the cloth diaper is in a wet state (60 ml liquid), the read distance is significantly reduced, measuring 5.5 m. This reduction highlights the substantial impact of moisture on the read distance performance, which is useful for detecting the moisture state of the diaper.

Effect of human body

Since the antenna operates in close proximity to the baby, the effect of the human body on the antenna’s performance was simulated using a cuboid-shaped multilayer human tissue model. This model, with dimensions of 200 × 200 × 40 mm³, was implemented in the CST simulation software to replicate the characteristics of the human body. The material properties of the layers used in the simulation are shown in Table 246. The distance between the human tissue model and the antenna is 30 mm. This is because the thickness of the cotton insert and the reusable cloth diaper are taken into consideration. Figure 17 shows the realized gains of the simulated and the measured results, showing reasonable agreement. This shows that the antenna is able to perform stable operation even when located close to the human body. In addition, regarding radiation safety, the U.S. FDA has declared RFID as safe in healthcare settings47, as long as the RFID reader is placed at a safe distance of more than 1 m with an EIRP of 3.2 W48,49,50. Moreover, our proposed antenna achieves a high read distance, due to the use of high conductivity material, ensuring it meets safety standards by allowing the reader to remain well beyond the recommended distance, further enhancing the suitability of the design for practical diaper moisture sensing applications.

Specific Absorption Rate (SAR) is an important metric for determining if an antenna is suitable for practical use on human body. Hence, the SAR values were simulated to verify that the proposed textile antenna is harmless to human body. The SAR levels were simulated in CST Microwave Studio using the similar separation distance, and the calculations were performed with reference to the IEEE/IEC 62704-1 standard with a benchmark of 0.5 W input power. Figure 18 shows the simulated SAR distributions. The maximum SAR value corresponding to the 1 g standard is equal to 0.106 W/kg, while the maximum SAR value corresponding to the 10 g standard is equal to 0.0834 W/kg. Both values are significantly below the regulatory limits of 1.6 W/kg (1 g US standard) and 2.0 W/kg (10 g European standard). These results confirm that the proposed antenna operates well within the SAR safety requirements, ensuring its suitability for infant wearable applications.

Comparison

Table 3 compares the proposed textile antenna with other reported diaper wetness detection RFID tags. Our proposed textile antenna offers significant advantages in terms of multi-level moisture detection, seamless integration with diaper materials, and high read ranges of 12.1 m in the dry state and 3.3 m in the wet state. To the best of our knowledge, these read ranges are the highest reported among passive wireless smart diaper technologies in the scientific literature. In comparison, the tissue-aluminium tag reported in51 offers only binary wet or dry detection, with very short read ranges of 0.07 m and 0.04 m for dry and wet conditions, respectively, making it unsuitable for practical diaper monitoring applications. The hydrogel-copper hybrid design reported in18, achieves only 1.0 m in the wet state, while the commercial paper-aluminum-based tag (Monza E64 Viper tag)16 achieves read ranges of 4.4 m for adult diapers and 3.6 m for baby diapers for dry conditions. Unlike these designs, our proposed antenna maintains robust and efficient performance under varying moisture conditions, supporting multilevel detection rather than being limited to binary wet/dry detection. Furthermore, both the hydrogel-copper tag and the Monza E64 Viper tags lack seamless integration onto diaper surfaces, resulting in limited practicability and mass production challenges. The denim-copper foil design reported in9, although capable of multilevel wetness detection and achieving a read range of 6.0 m when dry and 1.0 m when wet, suffers from limited suitability for diaper integration due to the use of copper foil. The silver ink-based textile RFID sensor reported in17, while suitable for integrating onto diaper and capable of multilevel moisture sensing, it offers a maximum read range of just 0.5 m in the wet state. Furthermore, its reliance on silver ink significantly increases the overall production expense. In contrast, the use of conductive fabric in our design is not only cost-effective but also ensures high conductivity and ease of fabrication, making it better suited for scalable production. In summary, the proposed textile antenna demonstrates superior performance in terms of high read range, multi-level wetness detection, seamless diaper integration, and cost efficiency. These features establish it as an ideal solution for infant care applications, addressing the limitations of existing technologies while enhancing usability and practicality.

Conclusion

A textile-based antenna is proposed for diaper moisture sensing. The dielectric and conductive parts of the antenna are made using textile materials for flexibility and seamless integration into the diaper. The bowtie antenna is chosen as a moisture sensor due to its strong sensitivity towards proximity moisture changes. Experimental results show that the antenna achieves a realized gain of -3.669 dBi at 915 MHz, with a good impedance matching with the UCODE 9 chip. The antenna showed a sensitive response to the different saline moisture levels from 0 to 60 ml. Electromagnetic analysis was performed, revealing that changes in the proximity of moisture significantly affect the impedance of the antenna. The textile antenna was successfully integrated into a reusable cloth diaper and tested on a baby doll, demonstrating a good read distance, and further validating its practical application. At the same time, the low SAR of 0.106 W/kg (1 g US standard) and 0.0834 W/kg (10 g European standard) meet the SAR requirements of both the US and EUR standards. This proposed antenna offers a promising solution for real-time diaper moisture monitoring, particularly suited for newborn infants, contributing to improved caregiving and hygiene practices. Future work could focus on integrating artificial intelligence into the system, enabling advanced functionalities such as predictive analytics or real-time monitoring in medical and caregiving environments.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

GrantViewResearch. Baby Diapers Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Product (Non-Disposable Diapers, Disposable Diapers), By Type (Open Diapers, Closed Diapers), By Size (New Born, Small), By Distribution Channel, By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2025–2030. 110 (2024).

Mroz, J. C. & Thomas, D. A. (Google Patents, 1980).

Šikić Pogačar, M., Maver, U., Marčun Varda, N. & Mičetić-Turk, D. Diagnosis and management of diaper dermatitis in infants with emphasis on skin microbiota in the diaper area. Int. J. Dermatol. 57, 265–275 (2018).

Khan, T. A noninvasive smart wearable for diaper moister quantification and notification. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 9, 2088 (2019).

Chaudhary, P. et al. Design and development of flexible humidity sensor for baby diaper alarm: experimental and theoretical study. Sens. Actuator B-Chem. 350, 130818 (2022).

Peng, Y. et al. A battery-free music-driven humidity sensor for intelligent wearable sensing system in smart diaper. Smart Mater. Struct. 32, 025016 (2023).

Maiti, S. & Dey, S. Design and analysis of a novel UHF RFID soil moisture sensor for smart farming. IEEE J. Radio Freq. Identif (2025).

Wu, Y., Hou, Z., Liu, Y. & Liu, W. Leaf moisture content detection method based on UHF RFID and hyperdimensional computing. Forests 15, 1798 (2024).

Alsultan, M. A., López-Soriano, S. & Melià-Seguí, J. Multi-textile and multi-band UHF RFID antenna-based sensor for noninvasive eHealth hydration monitoring. IEEE Sens. J. (2025).

Lee, Y. H., Lim, E. H., Bong, F. L. & Chung, B. K. Loop-fed planar inverted-L antennas (PILAs) for omnidirectional UHF on-metal Tag design. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propagat. 68, 5864–5871 (2020).

Low, J. H., Chee, P. S. & Lim, E. H. Cavity-backed double H-slot antenna with IPMC flaps for designing Frequency-switchable On/In-metal Semi-active Tag. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propagat (2022).

Ooi, S. Y., Chee, P. S., Lim, E. H., Low, J. H. & Bong, F. L. A zeroth-order slot-loaded cap-shaped patch antenna with omnidirectional radiation characteristic for UHF RFID Tag design. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propagat. 71, 131–139 (2022).

Ng, G. J. et al. Single-Layer truncated patch antenna with an inclined I-Slit for Anti-Metal Tag design. IEEE J. Radio Freq. Identif (2024).

Ganesan, V. K. et al. Far-Field ammonia gas sensing at room temperature with graphene Nanoplatelets-Infused PEDOT: PSS transparent thin film. Talanta Open, 100389 (2024).

Low, J. H., Chee, P. S. & Lim, E. H. Deformable liquid metal patch antenna for air pressure detection. IEEE Sens. J. 20, 3963–3970 (2019).

Tajin, M. A. S., Mongan, W. M. & Dandekar, K. R. Passive RFID-based diaper moisture sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 21, 1665–1674 (2020).

Tekcin, M., Palandoken, M. & Kursun, S. Wearable UHF-RFID sensor for wetness detection. IEEE Access (2023).

Sen, P., Kantareddy, S. N. R., Bhattacharyya, R., Sarma, S. E. & Siegel, J. E. Low-cost diaper wetness detection using hydrogel-based RFID tags. IEEE Sens. J. 20, 3293–3302 (2019).

Shahariar, H., Soewardiman, H., Muchler, C. A., Adams, J. J. & Jur, J. S. Porous textile antenna designs for improved wearability. Smart Mater. Struct. 27, 045008 (2018).

Lin, X. et al. Ultrawideband textile antenna for wearable microwave medical imaging applications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propagat. 68, 4238–4249 (2020).

Kapetanakis, T. N., Nikolopoulos, C. D., Petridis, K. & Vardiambasis, I. O. Wearable textile antenna with a graphene sheet or conductive fabric patch for the 2.45 ghz band. Electronics 10, 2571 (2021).

Zhang, K., Soh, P. J. & Yan, S. Design of a compact dual-band textile antenna based on metasurface. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuit Syst. 16, 211–221 (2022).

Gharbi, M. E., Fernández-García, R. & Gil, I. Textile antenna-sensor for in vitro diagnostics of diabetes. Electronics 10, 1570 (2021).

Hasni, U., Piper, M. E., Lundquist, J. & Topsakal, E. Screen-printed fabric antennas for wearable applications. IEEE Open. J. Antennas Propag. 2, 591–598 (2021).

NXP. UCODE® 9 Accelerates the IoT (2024). https://www.nxp.com/products/rfid-nfc/ucode-rain-rfid-uhf/ucode-9-accelerates-the-iot:SL3S1206FUD2

Zhong-Yang-Shielding-Materials-Manufacturer-(Taobao). Electromagnetic Shielding Fabric, https://e.tb.cn/h.6zxum9Zc9esOE9O?tk=GwoHVKbn5hK (2025).

Yamada, Y. Dielectric properties of textile materials: analytical approximations and experimental measurements—A review. Textiles 2, 50–80 (2022).

Balanis, C. A. Antenna Theory: Analysis and Design (Wiley, 2016).

Zamora, G., Zuffanelli, S., Paredes, F., Martı, F. & Bonache, J. Design and synthesis methodology for UHF-RFID tags based on the T-match network. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 61, 4090–4098 (2013).

Yang, L., Rida, A., Vyas, R. & Tentzeris, M. M. RFID Tag and RF structures on a paper substrate using inkjet-printing technology. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 55, 2894–2901 (2007).

Xi, J. & Zhu, H. in IEEE International Conference on RFID (RFID). 86–93 (IEEE, 2015).

Low, J. H., Chee, P. S., Lim, E. H. & Ganesan, V. Kirigami-inspired self-powered pressure sensor based on shape fixation treatment in IPMC material. Smart Mater. Struct. 33, 025029 (2024).

Low, J. H., Chee, P. S., Lim, E. H. & Gim, J. W. in 2023 IEEE International Symposium On Antennas And Propagation (ISAP). 1–2 (IEEE).

Lepoittevin, B. & Roger, P. Poly (ethylene terephthalate). Handb. Eng. Speciality Thermoplastics. 3, 97–126 (2011).

Tagformance Pro - Industry Standard in RFID Measurements. https://voyantic.com/lab/tagformance-pro/

Virtanen, J., Björninen, T., Ukkonen, L. & Sydänheimo, L. Passive UHF inkjet-printed narrow-line RFID tags. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 9, 440–443 (2010).

Abdulhadi, A. E. & Abhari, R. Design and experimental evaluation of miniaturized monopole UHF RFID Tag antennas. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 11, 248–251 (2012).

Edana EDANA Guidelines for the Testing of Baby Diapers (2016). https://www.edana.org/docs/default-source/international-standards/edana-diaper-test-protocol-2-0-final.pdf?sfvrsn=213c4e0_2

Holmdahl, G. et al. Four-hour voiding observation in healthy infants. J. Urol. 156, 1809–1812 (1996).

Guerra, L., Leonard, M. & Castagnetti, M. Best practice in the assessment of bladder function in infants. Ther. Adv. Urol. 6, 148–164 (2014).

Shokubai, N. Superabsorbent Polymers (2022). https://www.shokubai.co.jp/en/products/detail/sap/

Zohourian, M. M. & Kabiri, K. Superabsorbent polymer materials: A review (2008).

Alimenti, F. et al. A new contactless assembly method for paper substrate antennas and UHF RFID chips. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 59, 627–637 (2011).

Zhang, B., Zhang, J., Liu, C., Wu, Z. P. & He, D. Equivalent resonant circuit modeling of a graphene-based bowtie antenna. Electronics 7, 285 (2018).

Sundarsingh, E. F. et al. Polygon-shaped slotted dual-band antenna for wearable applications. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 13, 611–614 (2014).

Andreuccetti, D. An internet resource for the calculation of the dielectric properties of body tissues in the frequency range 10 Hz-100 ghz (2012). http://niremf.ifac.cnr.it/tissprop/

Administration, U. S. F. & a., D. Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) (2018). https://www.fda.gov/radiation-emitting-products/electromagnetic-compatibility-emc/radio-frequency-identification-rfid

Arumugam, D. D. & Engels, D. W. Specific Absorption Rates in Muscle Tissues for UHF RFID Reader Systems.

Zradziński, P., Karpowicz, J., Gryz, K., Owczarek, G. & Ramos, V. Modelling and evaluation of the absorption of the 866 MHz electromagnetic field in humans exposed near to fixed I-RFID readers used in medical RTLS or to monitor PPE. Sensors 21, 4251 (2021).

Marrocco, G. in Development and Implementation of RFID Technology 91–93 (IntechOpen, 2009).

Ziai, M. A. & Batchelor, J. C. Smart radio-frequency identification Tag for diaper moisture detection. Healthc. Technol. Lett. 2, 18–21 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.J.W.T performed the fabrication and measurements. P.S.C. and E.H.L. analysed the results. J.H.L and H.K.M wrote the manuscript and supervised C.J.W.T. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tean, C.JW., Low, JH., Chee, PS. et al. Design of a textile-based UHF RFID sensor for high read range and multilevel diaper moisture sensing. Sci Rep 15, 44357 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28171-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28171-7