Abstract

The proposed bidirectional converter exhibits a superior voltage gain compared to conventional designs and maintains low current ripple on both sides, making it highly suitable for photovoltaic and fuel cell applications. Notable features include the use of compact output filter capacitors, adequate voltage gain in both operational modes, and the elimination of coupled inductors. In step-up operation, switches S1 and S2 are activated simultaneously, while in step-down operation, switches S3, S4, and S5 are triggered at the same time. This switching scheme enables the converter to operate in each mode with a single PWM control signal, thereby simplifying the control circuitry. A thorough analysis has been carried out for both operating modes, and experimental verification using a 400 W prototype has confirmed a peak efficiency of 96.3%, validating the theoretical predictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

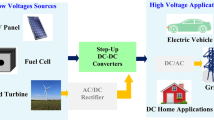

Introduction

Bidirectional converters support power transfer in both directions, making them ideal for EVs, smart grids, UPS, aerospace, and renewable energy applications1,2,3. Their ability to interface sources with storage removes the need for separate converters, resulting in more compact designs and higher efficiency. Bidirectional DC–DC converters (BDCs) can be classified as either isolated or non-isolated. In isolated architectures, a high-frequency transformer facilitates the DC–AC–DC conversion process while ensuring galvanic isolation between the low-voltage side (LVS) and the high-voltage side (HVS). In applications where isolation is unnecessary, non-isolated BDCs are generally preferred owing to their reduced structural complexity and simplified control requirements.

Non-isolated converter configurations include Cuk, SEPIC/Zeta, coupled-inductor, conventional buck–boost, three-level4,5,6,7, multilevel, and switched-capacitor types8. For Cuk and SEPIC/Zeta designs, the cascaded two-stage arrangement leads to lower conversion efficiency9,10. While coupled-inductor converters can deliver high voltage gain by adjusting the turns ratio11, they face persistent issues with leakage inductance, and their power processing capability is constrained by the magnetic core capacity. A coupled-inductor-based modification of the SEPIC converter was proposed in12, achieving high efficiency, high voltage gain, and soft-switching operation, but at the expense of additional active switches and capacitors. Battery charging and discharging are typically managed by bidirectional DC-DC converters (BDDCs), which must provide high buck gain during charging and high boost gain during discharging, while minimizing or eliminating current ripple on the battery side13,14,15,16. A wide range of converter designs and control techniques have been developed to address source current ripple. Coupled-inductor high-gain converters can significantly suppress ripple by selecting an appropriate turns ratio, but this enables either high voltage gain or ripple cancellation, not both at once. Non-coupled-inductor converters aimed at low source current ripple are generally classified into two groups: methods that decrease ripple amplitude and those that completely eliminate it at a specific duty ratio17.

Switched-capacitor converters offer a straightforward structure, simple control, and high scalability. By directing capacitor charge and discharge through different paths, energy can be transferred between the low- and high-voltage sides to attain high voltage gain. Early single-capacitor bidirectional designs18,19 exhibited low efficiency, leading to the development of interleaved switched-capacitor converter20 aimed at minimizing input current ripple. An interleaved configuration can effectively suppress significant current ripple on the low-voltage side (LVS)21. Complete ripple cancellation, however, requires the duty cycle to be locked to a specific ratio determined by the interleaving phase count. Ripple injection circuits, classified as active or passive, offer another suppression method. In the active scheme22, a ripple mirror circuit offset the inherent LVS ripple. Yet, eliminating the ripple entirely necessitates a fixed duty cycle, thereby constraining the attainable voltage conversion range. Reference23 introduced a DC–DC converter using voltage multiplier cells, providing high conversion ratio and low voltage stress. However, attaining such high gain necessitates multiple multiplier cells, which reduces power density and raises cost. In other works24,25,26,27, coupled-inductor designs achieve high voltage gain by adjusting the turns ratio of the magnetic components. A persistent drawback is leakage inductance, which induces voltage spikes on the switches, requiring snubber circuits to recover the associated energy. Reference28 introduces an active filter for source current ripple suppression, consisting of two switches, an inductor, and two capacitors. Although the converter’s voltage gain is preserved, the added components increase size and lower power density. The filter capacitors are regulated by separate converters operating at different frequencies and duty cycles, necessitating additional control circuitry and an isolation transformer. In29, a synchronous-switching bidirectional DC–DC converter was studied for LV-side ripple elimination, though it produced high HV-side ripple and used many switches.

The main contributions of this work are as follows: the development of a converter topology capable of maintaining low current ripple on both the high- and low-voltage sides; improved voltage gain in step-up operation and reduced gain in step-down operation; and the introduction of a design free from coupled inductors and switched capacitors, thereby enhancing power density while mitigating problems associated with leakage inductance and inrush current. In summary, this work presents a new bidirectional high step-up/step-down DC–DC converter topology that achieves high voltage gain with low device stress. Unlike most existing converters, the proposed design is free from coupled inductors and switched-capacitor networks, resulting in a simpler structure, reduced component count, and higher overall efficiency.

In this paper, Sect.“The proposed bidirectional converter” presents the description of the proposed converter along with its operation in both step-up and step-down modes. The steady-state analysis and design equations are provided in Sect. “Steady-state analysis of the proposed converter”. In Sect. “Small-signal analysis and controller design of the converter”, the small-signal model of the proposed converter for both operating modes is developed, and stability considerations are discussed. To benchmark the proposed topology against prior works, a comprehensive comparison is conducted in Sect. “Comparative assessment with recent advances”. Finally, Sect. “Loss analysis of a bidirectional DC-DC converter” provides the experimental results of a 400 W prototype to validate the theoretical analyses.

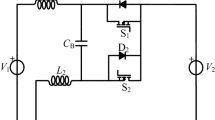

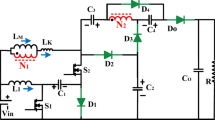

The proposed bidirectional converter

The proposed bidirectional converter, depicted in Fig. 1, consists of five switches, three inductors, and three capacitors. In the forward mode, switches S1 and S2 are simultaneously triggered while switches S3 through S5 remain off. Conversely, in the backward mode, switches S3 and S4 are triggered in a similar manner, with S1 and S2 turned off. Therefore, a single PWM pulse is sufficient to control the converter in both operating modes. During state 2 of both step-up and step-down modes, the MOSFET body diodes conduct naturally when the corresponding switches are turned off, providing a freewheeling path for the inductor currents and ensuring continuous current flow.

Converter operation

For ease of analyzing the steady-state characteristics of the proposed converter, the following practical assumptions are applied: (a) all power semiconductor devices and energy storage elements are considered ideal, and the converter operates under continuous conduction mode (CCM); (b) the capacitances are sufficiently large such that the voltage across each capacitor remains essentially constant during each switching cycle. In each mode of operation, the converter functions in continuous conduction mode (CCM) and exhibits two separate switching modes. Figure 2 depicts the key waveforms in both the step-up and step-down operating modes. Figures 3 and 4 show the equivalent circuits of the converter in the step-up and step-down modes, respectively.

Step-up mode

State 1:

switches S1 and S2 remain ON, while S3, S4, and S5 are kept OFF. Under these conditions, inductors L1 and L3 store energy, whereas capacitors C1, C2, and C3 release their stored charge. During this period, the load is powered entirely by the output capacitor CoH. The corresponding state-space equations for the converter in this operating state are expressed as follows.

State 2:

With switches S1 and S2 turned off, the body diodes of S4, S5, and S3 conduct. During this interval, inductors L1 and L3 release their stored energy to the output, while capacitors C1, C2, and C3 are being charged. This mode concludes once the switches are turned on again.

Step-down mode

State1:

In this state, switches S4, S5, and S3 are in the on-state, while S1 and S2 remain off. Inductor L3 is energized, and with S1 and S2 turned off, capacitors C1 and C2 are effectively paralleled, delivering their stored energy to the output via L1. Simultaneously, capacitor C3 supplies energy to magnetize the coupled inductor. During this mode, both L1 and L3 undergo a linear charging process. The state-space representation of the converter in this operating mode is expressed as follows.

State 2:

During this stage, switches S4, S5, and S3 are in the off-state, causing the body diodes of S1 and S2 to conduct. Consequently, inductors L1 and L3 release their stored energy to the output, while capacitors C1, C2, and C3 are being energized.

Steady-state analysis of the proposed converter

This section provides a comprehensive analysis of the proposed bidirectional converter, including its voltage gain in both modes of operation, the voltage and current stresses on the components, and the design equations for the passive elements.

Voltage gain

The voltage–second balance principle is applied to all three inductors of the circuit for both step-up and step-down operation modes. Based on these formulations, the expressions for the converter voltage gain in each mode are directly derived as follow.

For step-down mode:

Figure 5 depicts the voltage gain profiles of the converter under both step-up (Fig. 5(a) and step-down (Fig. 5(b)) operating modes.

Switch voltage stress

Using Kirchhoff’s voltage law for the switch loop when the switches are OFF, the maximum voltage across them can be easily determined from the following Eq.

Passive component design

Prior to selecting the capacitance values, it is essential to determine the average currents of the capacitors. By applying the ampere–second balance principle to capacitors C1, C2, C3, and Co, and utilizing Eqs. (2) and (4), the average currents of the inductors are derived as follows:

Small-signal analysis and controller design of the converter

By presuming ideal characteristics for all semiconductor and passive elements, the averaged and small-signal representations are formulated using the state-space averaging technique. In the step-up configuration (Fig. 3(b)) as well as in the step-down configuration (Fig. 4(a)), conduction of S4 and S5 or their intrinsic diodes places C1 and C2 in parallel, thereby enforcing voltage equality between C1 and C2.

Modeling of the step-up operating mode

To analyze the dynamic behavior of the proposed bidirectional converter, the state-space averaging technique is employed. Considering ideal semiconductor and passive elements, two subintervals corresponding to switch ON and OFF states are modeled in step-up mode. By averaging these models over a switching cycle with duty ratio D the large‐signal model is expressed as below

Modeling of the step-down operating mode

To investigate the dynamic performance of the proposed bidirectional converter in the step-down mode, the state-space averaging method is applied. Assuming ideal components, two switching intervals (ON and OFF states) are formulated, and their combination over a switching cycle with duty ratio D yields the corresponding large-signal model.

Dynamic behavior of the converter

Because the converter may exhibit nonminimum-phase behavior in step-up operation due to the presence of a right-half-plane zero, the crossover frequency ωc must be selected well below the RHP-zero frequency and also remain a small fraction of the switching frequency, i.e., ωc ≲ 0.2 ωz,RHP and ωc≪0.1 ωs. To ensure stable and well-damped closed-loop performance, a PI controller of the form CPI(s) = Kp+Ki/s = Kp(1 + ωi/s) with ωi = Ki/Kp is designed using loop-shaping. In the step-down operating mode, a PI controller is also adopted to regulate the output voltage and achieve stable closed-loop performance. Unlike the boost case, the buck configuration does not introduce a right-half-plane zero; therefore, the crossover frequency ωc can be selected higher, though it still must remain well below one-tenth of the switching frequency to ensure robustness, i.e., ωc≪0.1 ωs. The PI compensator maintains the same structure, CPI(s) = Kp+Ki/s = Kp(1 + ωi/s) where the zero is placed at ωi ≈ ωc/10 to improve phase margin and enhance low-frequency tracking. The proportional gain Kp is again tuned by enforcing unity open-loop gain at the chosen ωc. This procedure ensures that in the step-down mode the system achieves sufficient phase margin and disturbance rejection, while the integral term guarantees zero steady-state error in output voltage regulation.

Figure 6 depicts the control block diagram of the proposed bidirectional converter, whereas Figs. 7 shows the system’s Bode plots for the step-up and step-down modes, respectively, comparing the cases with and without the PI controller.

Comparative assessment with recent advances

Table 1 provides a comparative evaluation of the proposed converter against previously reported topologies in terms of voltage gain in both operating modes, component count, current ripple on both sides, and overall efficiency. Converters20,24,30,31, and32 exhibit both lower voltage gain and higher ripple at the high-voltage port, necessitating larger filter capacitors. Although converters33,34,35 maintain low current ripple on both sides, their achievable gain remains limited. As illustrated in Fig. 8, the proposed converter demonstrates superior performance in both step-up and step-down operations, reducing the duty ratio in step-up mode while increasing it in step-down mode. Additionally, converter20 incurs considerable conduction losses due to its diode-based structure, whereas converter27 is unsuitable for low-voltage applications such as batteries or fuel cells because of its high input-side ripple. Figure 8 illustrates the comparative voltage gain characteristics for both operating modes, where (a) corresponds to the step-up mode and (b) represents the step-down mode. Figure 9 compares the maximum switch voltage stress (Fig. 9(a)) and the maximum switch current stress (Fig. 9(b)) among the converters listed in Table 1. As demonstrated in Fig. 9, the proposed converter achieves superior performance by substantially reducing the normalized switch voltage and current stress, leading to lower conduction losses and component ratings.

Figure 10 presents a comparative analysis of the estimated cost and power density for the proposed converter and several state-of-the-art topologies reported in the literature. Each converter is represented by two adjacent bars corresponding to the cost (in USD) and the power density (in W/cm³). As illustrated, the proposed design exhibits a balanced performance achieving a significantly higher power density while maintaining a moderate overall cost compared with most reference converters.

Loss analysis of a bidirectional DC-DC converter

This section presents a detailed loss analysis of a bidirectional DC-DC converter operating in step-up and step-down mode. The goal is to calculate the conduction and switching losses of MOSFETs, conduction losses of body diodes, copper and core losses of the inductors, and losses in the capacitors, as well as to estimate the overall efficiency.

Step-up mode losses

MOSFET Conduction Losses: The conduction loss of each MOSFET is calculated using:

MOSFET Switching Losses: The switching losses due to turning on and off the MOSFETs are estimated by:

MOSFET Capacitive Turn-On Losses: The capacitive turn-on (drain-to-source capacitance) losses are calculated using:

Body Diode Conduction Losses: Conduction losses for the MOSFET body diodes are estimated by:

Inductor Copper Losses: The copper losses in the inductors are computed as:

Inductor Core Losses The core losses are estimated conservatively based on ferrite volume and typical loss density at 50 kHz:

The total core loss for the three Ferrite inductors is modeled and verified to be 0.73 W using the comprehensive loss equation at a switching frequency 50 kHz. The calculation incorporates the core’s effective area (Ae), set at 0.5 * 10− 4 m2, and a peak-to-peak flux density change \(\:\varDelta\:B=0.1T\). The key loss parameters for the Ferrite material are the frequency coefficient \(\:\alpha\:\), approximately 2.5 the volume coefficient (b), approximately 1, and the material coefficient (k), which is determined by the selected material and design to be 4.61 * 105.

Capacitor Losses: Capacitor ESR losses are calculated using:

In this mode, the total converter loss is obtained from theoretical calculations by summing the conduction and switching losses of the semiconductors, the copper and core losses of the inductors, and the ESR losses of the capacitors. The efficiency is then expressed as

Step-down mode losses

The same methodology applied for boost mode is also used to analyze the converter in step-down mode at full load. In this configuration, three switches are actively conducting while the body diodes of the remaining two switches carry current. The total losses are calculated by summing the conduction and switching losses of the active MOSFETs, the losses in the body diodes, the copper and core losses of the inductors, and the ESR losses of the capacitors. The efficiency is then determined as the ratio of the output power to the total of output power and losses. The detailed formulas used for each component’s loss calculation are presented. The loss analysis, detailing the distribution for both step-up and step-down modes, is summarized in the breakdown shown in Fig. 11.

Experimental verification

For experimental validation of the theoretical analyses, a laboratory prototype of the proposed converter was built, featuring a 400 W power rating and compact dimensions of 7*10*3.5 cm3. The detailed parameters of this prototype are listed in Table 2, and a photograph of the hardware implementation is shown in Fig. 12. Experimental results for both step-up and step-down operation modes are provided in Figs. 13 and 14, respectively. Specifically, Fig. 13(a) presents the gate voltage waveforms of switches S1 and S2, while Fig. 13(b) illustrates the drain–source voltage and current of S1. The current waveform of inductor L1 is presented in Fig. 13(c). The drain–source voltage and current of switch S2 are illustrated in Fig. 13(d), whereas Fig. 13(e) provides the measured input and output voltage profiles of the converter. The dynamic response of the converter to load variations, confirming the effectiveness of the control loop, is shown in Fig. 13(f). Likewise, for the step-down mode, Fig. 14(a) shows the gate voltage waveforms of switches S3 and S4, and Fig. 14(b) depicts their drain–source voltages. The drain-source currents of switches S3 and S4 are displayed in Fig. 14(c), and the corresponding current for S5 is illustrated in Fig. 14(d). Capacitor voltage waveforms (C1–C3) are presented in Fig. 14(e), and the dynamic load response is illustrated in Fig. 14(f). The dynamic response characteristics of the converter to input voltage changes are illustrated in Fig. 15, showing transient behavior under both sudden (Figs. 15(a), 15(b)) and linear (Fig. 15(c)) changes in the input voltage. Specifically, Fig. 15(c) depicts step-up operation where the input voltage rises steadily from 40 V to 100 V while the output voltage remains fixed at 360 V. Altogether, these experimental findings corroborate the theoretical analysis.

Converter efficiency

According to Fig. 16, the efficiency of the proposed bidirectional converter improves as the output power increases in both the step-up and step-down modes. At light loads, conduction and switching losses play a more dominant role in lowering efficiency, but their influence becomes less pronounced as the load grows, resulting in higher overall performance. When comparing the two modes, the step-down operation exhibits slightly better efficiency than the step-up operation, mainly due to fewer active switch turn-ons, lower circulating currents, and therefore reduced losses. In general, the converter maintains an efficiency 96.3% in step-down mode and 96% in step-up mode at full load, confirming its effectiveness and suitability for practical applications.

Conclusion

This study presents a novel bidirectional DC–DC converter capable of delivering very high voltage gain in the step-up mode and substantially reduced voltage gain in the step-down mode. The design employs only two switches operating concurrently in step-up mode and three switches operating together in step-down mode, which simplifies the control structure. Moreover, the proposed configuration achieves low current ripple on both input and output sides, enabling the use of smaller filter capacitors. Experimental results validate the effectiveness of the converter, showing excellent efficiency of 96% in step-up operation and 96.3% in step-down operation.

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Refrences

Farajzadeh, K., Mohammadian, L., Shahmohammadi, S. & Abedinzadeh, T. A novel bidirectional DC–DC converter with high voltage conversion ratio and capability of cancelling input current ripple. IET Power Electron. 17, 375–393 (2024).

Delshad, M., Madiseh, N. A. & Amini, M. R. Implementation of soft-switching bidirectional flyback converter without auxiliary switch. IET Power Electron. 6, 1884–1891. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-pel.2012.0472 (2013).

Banaei, M. R., Golmohamadi, M. & Afsharirad, H. Development and research of a new bidirectional extended gain DC–DC topology with modularity and continuous current. IET Power Electron. 18 (2), e70017. https://doi.org/10.1049/pel2.70017 (2025).

Lin, C. C., Yang, L. S. & Wu, G. W. Study of a non-isolated bidirectional DC–DC converter. IET Power Electron. 6 (1), 30–37 (2013).

Grbović, P. J., Delarue, P., Le Moigne, P. & Bartholomeus, P. A bidirectional three-level DC–DC converter for ultracapacitor applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 57(10), 3415–3430 (2010).

Wang, P., Zhao, C., Zhang, Y., Li, J. & Gao, Y. A bidirectional three-level DC–DC converter with a wide voltage conversion range for hybrid energy source electric vehicles. J. Power Electron. 17(2), 334–345 (2017).

Jin, K., Yang, M., Ruan, X. & Xu, M. Three-level bidirectional converter for fuel-cell/battery hybrid power system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 57(6), 1976–1986 (2010).

Das, P., Mousavi, S. A. & Moschopoulos, G. Analysis, design, and control of a nonisolated bidirectional ZVS-PWM DC–DC converter with coupled inductors. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 25(10), 2630–2641 (2010).

Jose, P. & Mohan, N. A novel ZVS bidirectional cuk converter for dual voltage systems in automobiles, in Proceedings of the IEEE IECON Conference Record, 117–122. (2003).

Kim, I. D., Paeng, S. H., Ahn, J. W., Nho, E. C. & Ko, J. S. New bidirectional ZVS PWM Sepic/Zeta DC–DC converter, in Proceedings of the IEEE ISIE Conference Record, 555–560. (2007).

Wai, R. J. & Duan, R. Y. High-efficiency bidirectional converter for power sources with great voltage diversity. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 22(5), 1986–1996 (2007).

Yao, J., Abramovitz, A. & Smedley, K. Steep gain bi-directional converter with a regenerative snubber. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 30(12), 6845–6856 (2015).

Loera-Palomo, R. & Morales-Saldana, J. A. Family of quadratic step-up DC–DC converters based on non-cascading structures. IET Power Electron. 8 (5), 793–801 (2015).

Gholizadeh, H., Babazadeh-Dizaji, R. & Hamzeh, M. High-gain buck–boost converter suitable for renewable applications, in Proc. IEEE 27th Iranian Conf. on Electrical Engineering (ICEE), 777–781. (2019).

Veerachary, M. & Khuntia, M. R. Design and analysis of two-switch-based enhanced gain buck–boost converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 69(4), 3577–3587 (2022).

Mahdizadeh, S., Tavakoli, A. & Afjei, E. A quadratic boost converter suitable for photovoltaic solar panel, in Proc. IEEE 13th Power Electronics, Drive Systems, and Technologies Conf. (PEDSTC), 357–361. (2022).

Yao, T. et al. Zero input current ripple DC–DC converter with high step-up and soft-switching characteristics. IEEE Trans. Ind. Applications 60(2), 2832–2839 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Gao, Y., Zhou, L. & Sumner, M. A switched-capacitor bidirectional DC–DC converter with wide voltage gain range for electric vehicles with hybrid energy sources. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 33(11), 9459–9469 (2018).

Chung, H. S. H., Ioinovici, A. & Cheung, W. L. Generalized structure of bi-directional switched-capacitor DC–DC converters. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Fund. Theory Appl. 50(6), 743–753 (2003).

Ardi, H., Ajami, A., Kardan, F. & Avilagh, S. N. Analysis and implementation of a nonisolated bidirectional DC–DC converter with high voltage gain. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 63(8), 4878–4888 (2006).

Kabalo, M. et al. Experimental validation of high-voltage-ratio low-input-current-ripple converters for hybrid fuel cell supercapacitor systems. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 61(8), 3430–3440 (2012).

Pan, C. T., Liang, S. K. & Lai, C. M. A zero input current ripple boost converter for fuel cell applications by using a mirror ripple circuit, in Proceedings of the IEEE 6th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference, 787–793. (2009).

Soltani, M., Mostaan, A., Siwakoti, Y. P., Davari, P. & Blaabjerg, F. Family of step-up DC–DC converters with fast dynamic response for low power applications. IET Power Electron. 9 (14), 2665–2673 (2016).

Sojoudi, T., Sarhangzadeh, M., Olamaei, J. & Ardashir, J. F. An extendable bidirectional high-gain DC–DC converter for electric vehicle applications equipped with IOFL controller. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 38(8), 9767–9779 (2023).

Rao, V. S., Tapaswi, S. & Kumaravel, S. Extendable bidirectional DC–DC converter with improved voltage transfer ratio and reduced switch count. IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Industrial Electronics 4(2), 460–470 (2023).

Heydari-doostabad, H. & O’Donnell, T. A wide-range high-voltage-gain bidirectional DC–DC converter for V2G and G2V hybrid EV charger. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 69(5), 4718–4729 (2022).

Yu, L. et al. A novel nonisolated GaN-based bidirectional DC–DC converter with high voltage gain. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 69(9), 9052–9063 (2022).

Garg, R. K. & Veerachary, M. A nonisolated bidirectional DC–DC converter with current ripple cancellation at a selectable duty ratio, in Proc. Global Conf. Renewable Energy and Hydrogen Tech., 1–6. (2023).

Selvam, S., Sannasy, M. & Sridharan, M. Analysis and design of two-switch enhanced gain SEPIC converter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 59(3), 3552–3561 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Gao, Y., Li, J. & Sumner, M. Interleaved switched-capacitor bidirectional DC–DC converter with wide voltage-gain range for energy storage systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 33(5), 3852–3869 (2018).

Jiang, F. et al. A zero current ripple bidirectional DC–DC converter with high voltage gain and common ground for hybrid energy storage system EVs. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 11(5), 4882–4894 (2023).

Wang, Z., Wang, P., Li, B., Ma, X. & Wang, P. A bidirectional DC–DC converter with high voltage conversion ratio and zero ripple current for battery energy storage system, IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, (Early Access), (2023).

Garg, R. K. & Veerachary, M. A non-isolated bidirectional DC–DC converter with current ripple cancellation at a selectable duty ratio, Proc. Global Conf. Renewable Energy and Hydrogen Tech., 1–6, (2023).

Kallelapu, R., Peddapati, S. & Naresh, S. V. K. A family of non-isolated quadratic buck–boost bidirectional converters with reduced current ripple for EV charger applications, IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, (Early Access), (2023).

Zhang, N., Zhang, G., See, K. W. & Zhang, B. A single-switch quadratic buck–boost converter with continuous input port current and continuous output port current. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 33(5), 4157–4166 (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the review of the manuscript. S. S was responsible for the design and execution of the experiments, data analysis, documentation, and overall supervision. M. D contributed to data analysis and provided supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sharifi, S., Delshad, M. A new coupled-inductor-free bidirectional DC-DC converter with low current ripple in both sides. Sci Rep 15, 44538 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28246-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28246-5