Abstract

Accurately predicting the specific heat capacity of nanofluids is critical for optimizing their performance in engineering and industrial applications. This study explores twelve machine learning and deep learning models using conventional and stacking ensemble techniques. In the stacking framework, a linear regression model is employed as a meta-learner to improve base model performance. Additionally, two nature-inspired metaheuristic optimization algorithms—Particle Swarm Optimization and Grey Wolf Optimization—were used to fine-tune the hyperparameters of machine learning models. This research is based on a comprehensive dataset of 1,269 experimental nanofluid samples, with key inputs including nanofluid type (hybrid and direct), temperature, and volume concentration. To improve model generalization, data augmentation strategies inspired by polynomial/Fourier expansions and autoencoder-based methods were implemented. The results demonstrate that the stacked multi-layer perceptron model, integrated with linear regression, achieved the highest predictive accuracy, recording an R² score of 0.99927, a mean squared error of 466.06, and a root mean squared error of 21.58. Among standalone machine learning models, CatBoost was the best performer (R² score: 0.99923, MSE: 487.71, RMSE: 22.08), ranking second overall. The impact of metaheuristic optimization was significant; Grey Wolf Optimization, for instance, reduced the LightGBM model’s mean squared error from 29386.43 to 6549.006. These findings underscore the efficacy of hybrid ML/DL frameworks, advanced data augmentation, and metaheuristic optimization in predictive modeling of nanofluid thermophysical properties, providing a robust foundation for future research in heat transfer applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

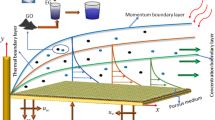

The accurate prediction of specific heat capacity (Cp) is crucial for optimizing the thermal performance of nanofluids in various industrial and engineering applications, including heat exchangers, cooling systems, and energy storage technologies. Traditional empirical and analytical methods often fail to capture the complex nonlinear relationships governing the thermophysical properties of nanofluids, leading to the need for more advanced data-driven approaches. While recent efforts have sought to improve these classical correlations by incorporating temperature-dependent terms1, they still generally lack the flexibility of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques. Consequently, data-driven techniques have gained prominence for modeling experimental datasets, demonstrating superior predictive performance and broader applicability across varying nanofluid formulations2. This investigation presents an integrated framework combining ML, DL, and metaheuristic optimization for Cp prediction in nanofluids. Rather than depending on constrained parametric equations, the methodology utilizes a comprehensive dataset encompassing temperature (°C), volume concentration (φ), and specific heat capacity measurements. Rigorous preprocessing was implemented to ensure data quality, incorporating polynomial and Fourier-based feature expansions alongside autoencoder-driven data augmentation to preserve fundamental physical dependencies. These strategies build upon established work applying computational intelligence to nanofluid thermophysical characterization, including recent advances in artificial intelligence and comprehensive reviews of ML-based approaches3,4,5,6,7,8. The study evaluates twelve ML and DL algorithms in standard and stacked configurations, with Linear Regression (LR) serving as the meta-model to enhance prediction accuracy by integrating linear relationships with sophisticated feature representations from base learners. Hyperparameter optimization employs Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO), both recognized for efficiently navigating high-dimensional parameter spaces9,10,11,12,13,14. Machine learning techniques have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in predicting the specific heat capacity of nanofluids. Said et al. (2022) explored the use of ensemble ML techniques for modeling the heat capacity of water-based hybrid nanofluids in solar energy applications. Similarly, Alade et al. (2019) developed an optimized support vector regression model using Bayesian algorithms to predict the specific heat capacity of alumina/ethylene glycol nanofluids. Oh and Guo (2024) extended this research by evaluating the applicability of various ML algorithms in predicting the heat capacity of complex nanofluids15,16,17.

Deymi et al. (2023) employed various ensemble learning techniques to model the specific heat capacity of nanofluids, demonstrating the superior predictive capability of integrated models compared to conventional correlations18. In a related study, Deymi et al. (2023) developed empirical correlations for estimating the specific heat capacity using GRG, GP, GEP, and GMDH algorithms, highlighting the effectiveness of hybrid and evolutionary learning methods in capturing nonlinear thermophysical behavior19. Further, Deymi et al. (2024) applied a radial basis function neural network (RBFNN) optimized by evolutionary algorithms to evaluate the density of mono-nanofluids, achieving enhanced accuracy and generalization20. More recently, Deymi et al. (2025) proposed innovative mathematical correlations using white-box machine learning models to estimate nanofluid density, providing interpretable insights into parameter influence and model transparency21.

Further contributions have been made in leveraging AI, particularly Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), for predictive modeling of specific heat capacity. This approach has been repeatedly shown to be a powerful tool for this task. For instance, Esfe et al. (2022) employed multilayer perceptron (MLP) artificial neural networks to investigate the effects of different nanoparticles on specific heat capacity and density22. The robustness of ANNs has been validated by several highly focused studies. Çolak (2020) developed an optimal ANN model to predict the specific heat of Y₂O₃/water nanofluids, achieving exceptionally high accuracy with a very low average error23. In a subsequent study, Çolak (2021) again used ANNs to successfully model ZrO₂/water nanofluids, providing a detailed comparison of the predictive performance of different training algorithms. This strong trend of using ANNs for high-accuracy predictions extends to other compositions as well24. Gupta and Mathur (2023) demonstrated improved accuracy over traditional models by applying ANNs25, while Mishra et al. (2024) reinforced this by using ANN-based models for transient heat transfer in CNT nanomaterials, and Boldoo et al. (2021) used an ANN to predict properties of MWCNT nanoparticle-enhanced ionic liquids26]– [27. Other advanced models and applications have also gained traction. Chaudhary et al. (2025) utilized ML models to predict the specific heat capacity of half-Heusler compounds, highlighting the adaptability of AI techniques beyond nanofluids28. Liu et al. (2023) expanded this approach by integrating ML-assisted modeling for ionic liquid-organic solvent binary systems29. Sajjad et al. (2021) introduced a deep learning framework for estimating the boiling heat transfer coefficient of porous surfaces, showcasing the potential of AI in capturing complex heat transfer mechanisms30. The integration of AI with numerical simulations has also been explored, with Albdour et al. (2024) applying ML for predicting condensation heat transfer and Elshehabey et al. (2024) and Knoerzer (2024) demonstrating its use in complex convection and heating predictions31,32,33. In addition to ML and deep learning-based studies, prior research has laid the foundation for AI-driven predictive modeling of nanofluid thermophysical properties. Adun et al. (2021) conducted a critical review of the specific heat capacity of hybrid nanofluids, identifying key trends and challenges in data-driven modelling34. This is a topic that has also seen recent experimental investigation, such as the work by Çolak et al. (2020) on Al₂O₃-Cu/water hybrid nanofluids35. Alade et al. (2019) and Alade et al. (2018) contributed significantly to the field by developing support vector regression models for predicting thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity36]– [37. Moreover, Mathur et al. (2024) examined soft computing approaches for predicting specific heat capacity, demonstrating the effectiveness of hybrid AI techniques in thermophysical property estimation38.

The integration of ML, deep learning, and numerical simulations has significantly improved prediction accuracy and broadened the applicability of AI techniques in thermophysical property modeling. These advancements provide a solid foundation for further research in optimizing thermal performance across various industrial applications. By integrating advanced data augmentation, modeling, and optimization techniques, this study establishes a highly accurate and scalable predictive framework for nanofluid specific heat capacity estimation. The methodology aligns with previous predictive modeling work on composite materials and heat exchangers, demonstrating the significance of AI-driven approaches in thermophysical analysis and providing a foundation for improved design and application of nanofluids in thermal management systems.

The principal contributions of this study are:

-

Comprehensive dataset assembly: A rigorously vetted dataset of 1,269 unique records spanning single-component and hybrid nanofluids was compiled, including composition, temperature (°C), volume fraction (ϕ), and specific heat capacity. Incomplete or inconsistent records were excluded.

-

Systematic model benchmarking: Twelve predictive models—eight machine-learning and four deep-learning architectures—were evaluated in baseline and stacked configurations, enhanced through polynomial/Fourier expansions or autoencoder augmentation, with hyperparameters optimized using PSO or GWO.

-

Performance and deployment metrics: Standard regression metrics (MSE, RMSE, MAE, R²), training time, inference latency, and memory footprint were measured, enabling selection of architectures balancing accuracy with computational efficiency.

These contributions establish the first optimization-driven workflow for real-time nanofluid specific heat capacity estimation, addressing a critical gap in thermal-fluid materials research.

The structure of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. Methodology provides an in-depth explanation of the materials and methods employed in this study. Section Results and discussion presents the experimental results and includes a discussion that lays the groundwork for the conclusions, which are outlined in Sect. Conclusion.

Methodology

The present study aims to establish a comprehensive framework for accurately predicting the specific heat capacity of nanofluids by integrating experimental data and advanced preprocessing methodologies. This work addresses critical gaps in conventional empirical approaches by leveraging diverse datasets from nanofluids and hybrid nanofluids38, enabling the development of a robust predictive model. The dataset includes essential thermophysical parameters such as temperature (°C), volume concentration (ϕ), and specific heat capacity. To ensure its suitability for modeling, the dataset underwent rigorous preprocessing to clean and standardize the data. Furthermore, advanced techniques such as Polynomial and Fourier inspired expansions4 and autoencoder-based data augmentation5 were applied to enrich feature representation, ensuring the preservation of critical physical relationships within the data.

The study employed a comprehensive evaluation framework incorporating twelve machine learning9 and deep learning models, assessed through an extensive set of performance metrics. To further advance predictive accuracy, this work uniquely integrates two state-of-the-art metaheuristic algorithms Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) for systematic hyperparameter optimization of the machine learning models11,12,13,14. This comparative optimization strategy, applied exclusively to machine learning architectures, enables identification of optimal parameter configurations across complex, high-dimensional search spaces, representing a methodological advancement in nanofluid property prediction.

The methodological framework developed in this study focuses on advancing the prediction of thermophysical properties, particularly the specific heat capacity of nanofluids, which is a critical parameter for optimizing performance in various engineering and industrial applications. A detailed overview of the methodology is illustrated in Fig. 1, showcasing the systematic workflow from data collection to model deployment.

Dataset description

The dataset utilized in this study integrates two distinct sources: the nanofluids dataset, which consists of 285 samples, and the hybrid nanofluids dataset, derived from peer-reviewed literature38 comprising 984 samples. This combined dataset results in a total of 1,269 samples. The input features include the Nanofluids, Temperature (°C), and Volume Concentration (ϕ), while the output feature is the experimentally measured Specific Heat Capacity of the nanofluids.

The integration of these datasets enhances the diversity and representativeness of the data, covering a wide range of nanofluid types and operating conditions. Supplementary Table 1 in Appendix outlines the nanofluid dataset along with its sources, and Supplementary Table 2 in Appendix provides a summary of the hybrid nanofluid dataset.

The relationship for the specific heat capacity of the nanofluid (\(\:{C}_{Phnf})\) is given by Eq. 1a:

Where, \(\:{C}_{Phnf}\) represents the specific heat capacity of the nanofluid, \(\:{C}_{Pbf}\) is the specific heat capacity of the base fluid, \(\:{C}_{Pnp}\) is the specific heat capacity of the nanoparticle, \(\:{\varnothing\:}_{v}\) represents the volume fraction of nanoparticles in the nanofluid.

This relation highlights the influence of nanoparticles on the overall specific heat capacity of the nanofluid, depending on the relative thermal properties of the nanoparticle and the base fluid. The term \(\:\left(\frac{{C}_{Pnp}}{{C}_{Pbf}}-1\right)\) reflects the contribution of the nanoparticle’s specific heat in modifying the thermal behavior of the nanofluid.

Colak et al. (2020) established a temperature-dependent correlation for the specific heat capacity (\(\:{C}_{p}\)) as a function of temperature (\(\:T\)) using four empirical constants coefficient A, B, C and D for the Cu-Al2O3/water nanofluid, the corresponding coefficient values are A = 0.0002322, B = 4.168, C = − 0.01175 and D = 0.6207 as defined in Eq. (1b)1. This correlation has been incorporated into the present study to account for the temperature-dependent variation of \(\:{C}_{p}\) in the thermal analysis.

The compiled dataset encompasses a wide array of nanofluids and hybrid nanofluids, incorporating various nanoparticle combinations, as outlined in Tables 1 and 2.These combinations include Fe₃O₄, AlN, Si₃N₄, TiN, and Al₂O₃ (Table 1), as well as MgO-TiO₂, MWCNT-CuO, MWCNT-MgO, MWCNT-SnO₂, Al₂O₃-Cu, Al₂O₃-GO, CuO-MgO-TiO₂, CuO-MWCNT, MgO-MWCNT, Al₂O₃-MWCNT, CeO₂-MWCNT, TiO₂-MWCNT, ZnO-MWCNT, MWCNT + Fe₃O₄, and SiO₂+TiO₂ (Table 2).The base fluids employed include ND, EG, Water, DW, and Green BG, showcasing a broad spectrum of fluid mediums. Overall, this study features twenty-one distinct nanoparticle and base fluid pairings, highlighting the versatility and adaptability of nanofluid applications.

Nanofluids and hybrid nanofluids display exceptional thermal properties, such as improved heat transfer and enhanced thermal conductivity, making them indispensable in fields like electronics cooling, automotive thermal management, heat exchangers, and biomedical technologies, including drug delivery systems and targeted therapies. Their application potential also extends to solar concentration systems, emphasizing their broad adaptability in renewable energy solutions39.

The statistical properties summarized in Tables 1 and 2 offer key insights into the characteristics of the input and output variables in this study: Temperature (°C), Volume Concentration (ϕ), and Specific Heat (\(\:{C}_{phnf}\)). Statistical analysis reflects a dataset characterized by considerable complexity and the presence of extreme values. These distributional characteristics highlight the importance of accounting for a broad range of conditions when investigating the thermal properties of nanofluids.

Dataset preprocessing

Data preprocessing is a fundamental step in ensuring the dataset’s quality and compatibility with predictive models. The combined dataset, integrating the hybrid nanofluids dataset and the nanofluids dataset, resulted in 1,269 samples. This integration captured a wide variety of nanofluid types and operating conditions, enhancing data diversity. Special care was taken to handle missing values and ensure data consistency. Any inconsistencies or anomalies, such as duplicate entries or incorrect formats, were resolved to maintain the dataset’s integrity.

Categorical features, such as the nanofluids, were processed using one-hot encoding, converting categorical variables into binary vectors. Then, the numerical features, including temperature and volume concentration, were standardized to zero mean and unit variance to ensure uniform contribution during model training and prevent dominance by features with larger ranges40]– [41. Statistical analysis provided valuable insights into the dataset’s variability and helped confirm the adequacy of feature distributions for model training.

The dataset was then split into training and testing sets in an 80:20 ratio, allocating 80% of the data for model training and 20% for evaluation. This split ensured unbiased testing and robust model assessment on unseen data.

Augmentation

In machine learning and deep learning, model performance is closely tied to both the quality and quantity of the data used. In this study, the dataset exhibited variability and included regions with underrepresented samples. To address these issues and improve the generalization ability of the models, data augmentation was applied by generating new data points from existing ones—while preserving key statistical properties and physical relationships. This approach enhances model robustness and helps reduce overfitting, without altering the imbalance ratio or introducing bias42.

For this study, two augmentation techniques were utilized: Polynomial and Fourier Expansions Inspired and Autoencoders-based. Each method contributed differently to enhancing the dataset, and their effects on the final model performance were carefully evaluated.

Polynomial and fourier expansion inspired augmentation

This augmentation method enhances numerical features by applying polynomial and Fourier-inspired transformations to generate higher-order features. These expansions allow the model to capture complex, non-linear relationships and periodic patterns, thereby improving model robustness and its ability to generalize across diverse data43.

Polynomial feature expansion

Polynomial expansion introduces higher-order terms, allowing the model to represent non-linear dependencies more effectively. For a feature \(\:{x}_{i}\), the polynomial expansion of degree \(\:d\) is expressed as Eq. 2:

This transformation introduces interaction terms and higher powers of features, which enables the model to account for intricate relationships within the data44.

Fourier-Inspired expansion

The Fourier-inspired expansion applies sine and cosine transformations at various frequencies, allowing the model to capture periodic patterns in the data. While this approach is inspired by the Fourier series, it does not follow the Fourier transformation in its strict mathematical form. For a numerical feature \(\:{x}_{i}\), the Fourier-inspired transformation with n terms is given by Eq. 345:

Here, \(\:N\) denotes the number of frequencies used. This introduces cyclic behavior, helping the model detect periodic signals.

Combining both expansions

The final augmented feature set is created by combining both the polynomial and Fourier-inspired transformations. The expanded dataset \(\:{X}_{expanded}\) is represented as Eq. 4:

This step is depicted in Fig. 2, where the polynomial features \(\:{X}_{poly}\) and the Fourier-inspired features \(\:{X}_{fourier}\) are concatenated to form a richer feature set. The augmented dataset is then created by combining the expanded features with the original categorical ‘Nanofluid’ columns as shown in Eq. 5.

Figure 2 illustrates this complete augmentation pipeline, where original features are enriched with polynomial and Fourier-inspired components to produce a more expressive dataset.

Autoencoder based augmentation

Autoencoders are employed for augmentation to enrich the dataset by generating new, slightly noisy versions of the original data. The process involves learning a compact representation of the input data through the encoder and then reconstructing it with small perturbations during the decoding stage. This approach helps the model generalize better by introducing variations, especially when dealing with noisy or incomplete data46.

The Autoencoder architecture consists of two primary components: the encoder and the decoder. The encoder maps the input data \(\:x\) into a lower-dimensional latent space \(\:z\), the decoder reconstructs the input data \(\:\widehat{x}\:\)from this compressed representation. This is visualized in Fig. 3.

Encoder Function,

Decoder Function,

The autoencoder is trained to minimize the Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss between the original data \(\:x\) and the reconstructed data \(\:\widehat{x}\), given by Eq. 8.

where N is the number of samples in the dataset, and \(\:{x}_{i}\) and \(\:\widehat{{x}_{i}}\) represent the original and reconstructed data points, respectively.

Data augmentation with autoencoder

Once the autoencoder is trained, the decoder is used to generate noisy version of the original data by reconstructing it. The noisy data \(\:{x}_{noisy}\) can be expressed as Eq. 9.

Where, \(\:\epsilon\) denotes the reconstruction noise. By repeating this process iteratively, multiple noisy variants are produced. The final augmented dataset \(\:{X}_{augmented}\) is formed by concatenating the original dataset \(\:X\) with the generated noisy data \(\:{X}_{noisy}\) as shown in Eq. 10.

This process, as shown in Fig. 3, results in an augmented dataset containing both the original and noisy data, improving the model’s ability to generalize.

Optimization

Optimization algorithms play a critical role in enhancing machine learning models by fine-tuning their hyperparameters. They explore the hyperparameter space to identify configurations that improve model accuracy and computational efficiency. In this study, optimization was applied after data preparation and augmentation to effectively address the complexity of nanofluid-specific heat capacity prediction.

In this study, two nature-inspired optimization algorithms, Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO), were utilized. These algorithms were selected due to their proven ability to efficiently explore complex, high-dimensional search spaces. Both approaches are adept at navigating a wide range of hyperparameter combinations and converging toward a global optimum, making them particularly well-suited for optimizing machine learning models47.

Particle swarm optimization

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is a population-based optimization algorithm48 inspired by the social behaviours of flocking birds and schooling fish. It optimizes a problem by iteratively adjusting a population of particles, where each particle represents a potential solution in the search space. At each iteration, particles update their positions based on both their own experience and the best solution found by the swarm.

The velocity update49 mechanism is governed by Eq. 11.

where, \(\:{v}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\) is the particle’s velocity, \(\:{x}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\) is its position in the search space. \(\:pbes{t}_{i}\) represents the best-known position of the particle, and \(\:gbest\) is the best global position found by the swarm. The coefficients \(\:{c}_{1}\) and \(\:{c}_{2}\) control the cognitive and social influences, while \(\:{r}_{1}\) and \(\:{r}_{2}\) are random variables, and \(\:\omega\:\) is the inertia weight that balances exploration and exploitation.

The position of each particle is updated as shown in Eq. 12.

This process continues until a stopping criterion such as convergence or maximum iterations is met.

PSO is well-suited for complex, non-differentiable optimization tasks, making it ideal for hyperparameter tuning. In this study, PSO significantly improved model performance, as visualized in Fig. 4, which outlines the algorithm’s workflow.

Grey Wolf optimization

Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) is a nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm based on the social structure and hunting behavior of grey wolves. The population is divided into four roles: Alpha (α), Beta (β), Delta (δ), and Omega (ω). The Alpha represents the best solution and leads the search, supported by Beta and Delta wolves, which refine and communicate decisions. Omega wolves act as exploratory agents, preserving population diversity and avoiding premature convergence50. This structured hierarchy ensures an effective balance between exploration and exploitation.

The wolves’ positions are updated using Eq. 13.

where, \(\:A\) and \(\:{C}_{1}\) are coefficient vectors, and \(\:{D}_{\alpha\:}\) is the distance to the Alpha. The distance is computed using Eq. 14.

The coefficient vectors are defined as:

where, \(\:\alpha\:\) decreases linearly from 2 to 0 over iterations, and \(\:{r}_{1}\) and \(\:{r}_{2}\) are random vectors in the range [0,1].

The algorithm iteratively updates solutions until convergence, or a stopping criterion is met. As illustrated in Fig. 5, GWO was selected for its strong exploration–exploitation balance, making it highly effective for hyperparameter optimization in machine learning.

Models

Accurate estimation of nanofluid specific heat capacity requires predictive models capable of capturing both linear and complex non-linear patterns. The study employed twelve models, combining machine learning and deep learning approaches. Machine learning models extracted structured relationships from input features, while deep learning models integrated feature extraction and regression within a unified framework using backpropagation51 for parameter adjustment based on error gradients.

A key methodological innovation is the implementation of a stacking ensemble approach with Linear Regression as the meta-learner, which synergistically combines all twelve models to harness their complementary predictive capabilities while mitigating individual limitations. To optimize performance, this study employs a dual-optimization strategy: machine learning models underwent hyperparameter tuning using both Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) for comparative analysis, while deep learning models relied on backpropagation for optimization. This hybrid approach maximizes each model class’s predictive capability according to its computational characteristics.

Figures 6 and 7 illustrate the workflows for machine learning and deep learning pipelines, including model training, tuning, evaluation, and ensemble integration.

Decision tree

The Decision Tree is a widely used algorithm that divides data into subsets based on feature values to generate predictions. The model is represented by a tree structure, where each internal node corresponds to a decision rule based on a feature, each branch represents the outcome of that decision, and each leaf node holds the prediction. The algorithm splits the dataset iteratively by selecting features and thresholds that minimize a chosen impurity metric, such as Gini Impurity or Entropy52.

For regression tasks, Decision Trees aim to minimize the variance within subsets53. The split criterion is based on minimizing the Mean Squared Error (MSE) at each node, calculated as given by Eq. 16.

Where n is the number of samples at the node, \(\:{y}_{i}\) is the actual value, and \(\:\stackrel{-}{y}\) is the mean of the target values at the node. Key hyperparameters include maximum tree depth, minimum samples for splits, and minimum samples at leaves, which control complexity and generalization ability.

Random forest

Random Forest aggregates multiple decision trees to improve predictive accuracy. Each tree trains on a random data subset, with final predictions made by averaging all individual tree outputs54. This ensemble approach reduces variance and improves generalization compared to single decision trees, effectively capturing complex, non-linear relationships in nanofluid specific heat capacity data. The performance of the random forest model is influenced by the aggregation of individual tree predictions. Mathematically, the final prediction of the random forest can be expressed as the average of the predictions made by each individual tree in the ensemble, as given in Eq. 17.

where \(\:{T}_{i}\left(x\right)\) is the prediction of the \(\:i\)-th tree and \(\:n\) is the number of trees in the forest.

K-Nearest neighbor (kNN)

K-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) predicts target values by averaging the values of the \(\:k\) closest neighbors using distance metrics, typically Euclidean distance55. The distance between two data points \(\:{x}_{i}\) and \(\:{x}_{j}\) in d-dimensional space is computed as given in Eq. 18.

where \(\:{x}_{i,k}\) and \(\:{x}_{j,k}\) represent the feature values of the \(\:i\)-th and \(\:j\)-th data points, respectively, and d is the number of features. For regression tasks, the predicted target value \(\:\widehat{{y}_{i}}\) for a data point \(\:{x}_{i}\) is given by Eq. 19.

where \(\:{y}_{j}\) is the target value for the \(\:j\)-th neighbor and \(\:k\) is the number of nearest neighbors.

LightGBM

Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) is an optimized gradient boosting framework that builds tree leaf-wise for improved performance with computational efficiency56. This approach effectively captures complex patterns in large nanofluid datasets. The objective function for training LightGBM can be written as given in Eq. 20.

where \(\:l({y}_{i},\widehat{{y}_{i}})\) is the loss function (commonly squared error),\(\:\:\varOmega\:\left({f}_{k}\right)\) is the regularization term, \(\:n\) is the number of data points, and \(\:K\) is the number of trees57. The regularization term is given by Eq. 21.

where T is the number of leaves, γ is the complexity parameter, \(\:\lambda\:\) is the regularization parameter, and \(\:w\) represents the tree’s weights.

Gradient boosting

Gradient Boosting builds decision trees sequentially, with each tree addressing errors made by previous ones. This approach excels at capturing complex patterns in nanofluid specific heat capacity prediction by progressively improving model performance through focus on residual errors. For Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR)58, the objective function seeks to minimize the loss, typically expressed as given in Eq. 22.

where \(\:L\left(\theta\:\right)\) is the loss function, \(\:{y}_{i}\) and \(\:\widehat{{y}_{i}}\) are the true and predicted values, and \(\:{f}_{k}\) represents individua trees.

AdaBoost

AdaBoost (Adaptive Boosting) combines multiple weak learners, typically decision trees, by training models sequentially with emphasis on previously misclassified data points59. The objective function for AdaBoost aims to minimize the weighted error of the weak learners over iterations and is given by Eq. 23.

where \(\:{w}_{i}\) are the weights assigned to the data points in each iteration. \(\:{y}_{i}\) is the true class label of the sample \(\:{x}_{i}\). \(\:H\left({x}_{i}\right)\) is the prediction made by the weak learner for sample \(\:{x}_{i}\). The sum is over all \(\:m\) data points.

XGBoost

Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) enhances traditional gradient boosting through improved regularization techniques and parallel processing optimization60. It builds decision trees sequentially to correct previous errors while balancing accuracy and model complexity. The objective function for each tree \(\:k\) in XGBoost can be expressed as given in Eq. 24.

where \(\:l\left({y}_{i},{\widehat{y}}_{i}\right)\) is the loss function that measure prediction errors, and \(\:\varOmega\:\left({f}_{k}\right)\) is the regularization term. The regularization term is given by Eq. 25.

Where \(\:\gamma\:\) and \(\:\lambda\:\) control tree complexity, \(\:T\) is the number of leaves and \(\:w\) represents the tree’s weight vector. This regularization helps mitigate overfitting by constraining the complexity of individual trees in the ensemble.

CatBoost

CatBoost is a gradient boosting algorithm optimized for categorical features. It employs ordered boosting to prevent overfitting and data leakage by ensuring predictions are based only on prior observations61. The objective function of CatBoost is a combination of a loss function \(\:L({y}_{i},f\left({x}_{i}\right))\) and a regularization term to control model complexity. The general form of the objective function is given by Eq. 26.

Where \(\:{y}_{i}\) represents the true value, \(\:f\left({x}_{i}\right)\) the model’s prediction for the \(\:i\)-th sample, \(\:\lambda\:.\varOmega\:\left(f\right)\) is the regularization term that prevents overfitting. CatBoost’s ability to efficiently handle categorical data, coupled with its innovative boosting framework, makes it a reliable choice for regression tasks involving diverse datasets, such as those encountered in nanofluid property prediction.

Multi-Layer perceptron (MLP)

The Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) is a neural network architecture designed to capture complex, non-linear relationships in data. Comprising of an input layer, hidden layers, and an output layer, the MLP uses activation functions such as ReLU or Tanh to introduce non-linearity, enabling it to model intricate patterns effectively62. MLP is particularly suitable for tasks that require learning complex data representations and capturing non-linear dependencies.

The MLP training process minimizes the loss function as given by Eq. 27.

where \(\:{y}_{i}\) and \(\:\widehat{{y}_{i}}\) are the actual and predicted values, \(\:w\) represents the weights, and \(\:\alpha\:\) controls regularization.

In the ensemble framework, MLP serves as a feature extractor, with outputs from its penultimate layer feeding into a Linear Regression model to combine deep learning’s representational power with linear model interpretability.

Long Short-Term memory (LSTM)

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) is a recurrent neural network designed to capture long-term dependencies in sequential data. Using memory cells, it overcomes the vanishing gradient problem faced by traditional RNNs. The core of the LSTM model consists of three gates: the forget gate, the input gate, and the output gate. The forget gate determines what information should be discarded from the previous cell state and is given by Eq. 2863.

The input gate decides what new information will be added to the cell state, represented by Eq. 29.

The cell state is then updated by combining the previous cell state and the new candidate memory, as shown in Eq. 30.

Finally, the hidden state is calculated using the output gate, which determines the part of the cell state to output given as Eq. 31.

In this work, an additional configuration was implemented where LSTM served as a feature extractor. The resulting representations captured underlying temporal dependencies and were used as inputs to a linear regression model for predicting specific heat capacity.

Gated recurrent unit (GRU)

The Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) is a recurrent neural network (RNN) designed to capture long-term dependencies in sequential data while addressing the vanishing gradient issue. Compared to LSTM, GRU offers similar performance with simpler and more computationally efficient architecture63]– [64.

The GRU consists of two main gates: the update gate \(\:{z}_{t}\) and the reset gate \(\:{r}_{t}\). The update gate determines how much of the previous hidden state is carried forward, while the reset gate controls how much past information should be forgotten. The candidate hidden state \(\:\stackrel{\sim}{{h}_{t}}\) and the final hidden state \(\:{h}_{t}\) are computed as given by Eqs32,33,34,35. :

These mechanisms allow GRU to retain relevant temporal features while discarding noise.

In the stacked variant, GRU extracts latent temporal features for a Linear Regression model, combining representational strength with linear model simplicity.

Autoencoder

An Autoencoder is a neural network used for unsupervised learning, often applied to dimensionality reduction and feature extraction. It comprises an encoder that maps input \(\:x\) to a latent space \(\:h\) via a nonlinear activation function \(\:f\), as shown in Eq. 36.

where \(\:{W}_{e}\) and \(\:{b}_{e}\) are the encoder’s weights and biases. The decoder reconstructs the input \(\:\widehat{x}\) from the latent representation \(\:h\) using another nonlinear function \(\:g\), as shown in Eq. 37.

where \(\:{W}_{d}\) and \(\:{b}_{d}\) are the decoder’s weights and biases, and \(\:g\) is the activation function in the decoder. The model is trained by minimizing the reconstruction error between the original input \(\:x\) and the reconstructed output \(\:\widehat{x}\). The objective function for training the Autoencoder is given by the following Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss as given by Eq. 38.

where \(\:{x}_{i}\) is the input data, \(\:\widehat{{x}_{i}}\) is the reconstructed data, and \(\:n\) is the number of data points.

In the stacked variant, the Autoencoder extracts latent features from the dataset, which are then input to a Linear Regression model to predict the specific heat capacity of nanofluids. Training is performed using the Adam optimizer with MSE as the loss function.

Performance metrics

In machine learning regression tasks, performance metrics are essential for evaluating a model’s accuracy and ability to generalize. These metrics help compare different models and guide optimization efforts. In this study, several performance metrics were used to assess the quality of the predictions, including the R² Score, Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Explained Variance Score, Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error (SMAPE) and Max Error. These metrics provide a comprehensive evaluation of prediction quality, capturing various aspects such as error magnitude and model fit65,66.

Results and discussion

This section presents the outcomes of the experiments conducted in this study. The performance of the models was evaluated using the metrics described in methodology, providing insights into their accuracy, robustness, and generalization ability. Results are discussed in terms of overall prediction quality, the impact of hyperparameter optimization, and the effectiveness of stacking and augmentation techniques.

Dataset analysis

The dataset utilized in this study, as detailed in methodology, integrates nanofluid and hybrid nanofluid data, resulting in a total of 1,269 samples. These samples cover diverse combinations of nanoparticles, base fluids, and operational conditions, providing a robust foundation for predictive modeling. Input features include Nanofluid, Temperature (°C), and Volume Concentration (ϕ) with the target variable being the experimentally measured Specific Heat capacity. The dataset’s diversity and representativeness were further improved through comprehensive preprocessing, which included one-hot encoding for categorical features and standardization for numerical features.

Figure 8 illustrates the distribution of nanofluid samples in the dataset, showing the count for each nanofluid type. The figure provides a clear overview of the relative frequency of different nanoparticles and base fluid combinations, reflecting the dataset’s overall composition.

Feature distribution

The distribution of the key features in the dataset, as shown in Fig. 9, reveals valuable insights into the underlying data patterns. The histograms for Temperature (°C), Volume Concentration (ϕ), and Specific Heat capacity highlight the variability and representativeness of the dataset.

The temperature distribution shows a uniform spread between 20 °C and 50 °C with multiple plateaus, featuring a secondary peak around 50 °C before tapering off at 70 °C. This range encompasses typical operational conditions for nanofluid applications in both industrial and experimental settings. Volume concentration (ϕ) exhibits a right-skewed distribution, with most samples concentrated below 2% and peak frequency under 1%, while including sparse but valuable data points up to 9%. This distribution aligns with practical applications where lower concentrations are preferred for optimal thermal performance and stability. The specific heat capacity demonstrates a unimodal distribution centered at 3500–4000 J/kg·K, with a secondary cluster in the 2000–3000 J/kg·K range, and extends from 2000 to 9000 J/kg·K. This wide range effectively captures the diverse thermal behaviors across different nanofluid compositions and operating conditions, providing a comprehensive foundation for predictive modeling.

The correlation analysis between the primary features reveals valuable insights into their interdependencies (Fig. 10). The correlation matrix shows that volume concentration (ϕ) exhibits a moderate negative correlation (r = -0.43) with specific heat capacity, indicating that as particle concentration increases, the specific heat capacity tends to decrease. This aligns with the fundamental behavior of nanofluids, where higher particle concentration generally67 results in a decrease in specific heat capacity. In contrast, temperature shows negligible correlations with both specific heat capacity (r = 0.02) and volume concentration (r = 0.12), suggesting that temperature variations within the studied range have minimal impact on these other parameters. Notably, the weak to moderate correlation coefficients across features indicate non-straightforward relationships, revealing the presence of complex, non-linear interactions in nanofluid behavior that conventional correlation-based approaches cannot adequately capture. This critical observation justifies the adoption of advanced machine learning and deep learning modeling techniques capable of capturing these intricate multi-dimensional patterns.

Analyzing specific heat capacity trends across nanofluid compositions

To better understand the relationship between specific heat capacity and key input parameters, a series of visual analyses were conducted for all twenty-one nanofluid compositions in the dataset. Figure 11, which visualizes these relationships in a 3D feature space, immediately reveals the diverse and complex nature of the data. This visualization highlights several distinct patterns across the compositions. For instance, compositions such as AiN/EG and TiN/EG are exceptionally sparse, representing nanofluids with very few available experimental data points. This sparsity poses a significant modeling challenge, requiring a model capable of generalizing from limited information. In contrast, fluids like Al2O3/EG and Al2O3/Water exhibit a highly structured, dense, grid-like distribution. This visual pattern suggests a stable, systematic, and more readily predictable relationship between the variables.

Finally, many of the hybrid nanofluids, including MWCNT-CuO/Water and Al2O3-MWCNT/Water, demonstrate a high data volume but with significant vertical scatter in the specific heat capacity values. This high variance indicates a much more complex and non-linear relationship, where \(\:{C}_{p}\) is highly sensitive to input parameter variations. This observed diversity in data patterns, ranging from sparse to highly structured and complex, confirms that a single, simple analytical model (like the mixing model in Eq. 1) would be insufficient to capture these varied behaviors. It validates the necessity for the sophisticated machine learning framework developed in this study, which is designed to learn these unique patterns for each composition. A more granular breakdown of these relationships is available in the Appendix (Supplementary Figs. 1, 2, and 3).

Baseline model performance analysis

Table 3 presents the baseline performance of twelve machine learning and deep learning models in predicting the specific heat capacity of nanofluids. Each model was evaluated in both standalone form and in a stacked configuration using Linear Regression as a meta-learner. The best-performing version of each model was selected for comparison. Performance was assessed using standard metrics, while detailed architectural configurations are available in Appendix Supplementary Table 3.

Among all configurations, the Autoencoder stacked with Linear Regression delivered the highest predictive accuracy, achieving an R² score of 0.99921, the lowest MSE (509.21), and an RMSE of 22.56. Gradient boosting models such as XGBoost and CatBoost also performed exceptionally well in their direct implementations, achieving R² values of 0.99893 and 0.99876, respectively, and maintaining low error values.

Recurrent models, including GRU and LSTM when stacked with Linear Regression, also yielded strong results, with R² values exceeding 0.998. Other stacked configurations, such as MLP + LR and Gradient Boosting stacked with Linear Regression, demonstrated competitive performance but were marginally outperformed by the top models. In contrast, traditional models like Decision Tree and Random Forest achieved high R² scores (0.99699 and 0.99729) but showed relatively higher error metrics, indicating more limited performance in capturing nuanced patterns within the data.

Overall, the Autoencoder stacked with Linear Regeression model stands out as the most effective baseline configuration, followed closely by XGBoost and CatBoost.

Augmentation

Two augmentation techniques were applied: one inspired by Polynomial and Fourier expansions and the other leveraging Autoencoder-based reconstruction. Specifically, the dataset was expanded to 6084 and 5064 additional samples, respectively, as detailed in Appendix Supplementary Table 4. The impact of each method was evaluated across multiple predictive models, with best performance results summarized in Tables 4 and 5. A detailed breakdown of the augmentation process is available in Appendix (Supplementary Tables 5–7).

Polynomial and fourier expansion inspired augmentation

This augmentation approach applied higher-order polynomial and periodic transformations to numerical features, expanding the dataset sixfold and improving its structural complexity. As presented in Table 6, the Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) model exhibited the best performance, achieving an R² score of 0.99901, MSE of 631.57, and RMSE of 25.13, reflecting strong generalization on the augmented data. CatBoost also performed well, with an R² of 0.99896, MSE of 665.76, and RMSE of 25.80.

Stacked models, particularly Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) stacked with Linear Regression and LSTM stacked with Linear Regression, also responded positively to this augmentation. The MLP model achieved an R² score of 0.99860 with an RMSE of 29.91, while the LSTM model reached an R² of 0.99884 and RMSE of 27.21. Similarly, the Random Forest stacked with Linear Regression and k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) stacked with Linear Regression models showed notable gains.

On the other hand, AdaBoost stacked with Linear Regression struggled to benefit from the added complexity, recording an R² of only 0.92916 and a notably high MSE of 45403.06. In contrast, the LightGBM model improved significantly with this augmentation, reaching an R² score of 0.98318 and MSE of 10781.18. Overall, while the performance boost varied by architecture, models capable of leveraging high-dimensional, non-linear transformations such as GRU, CatBoost, and LightGBM demonstrated the most pronounced improvements.

Autoencoder-Based augmentation

The Autoencoder-based augmentation technique used deep learning autoencoders to extract latent features and generate 5064 additional samples, enriching the dataset with structurally diverse yet consistent data points. The model performance results are presented in Table 7.

Model responses to this augmentation varied. GRU achieved an R² of 0.99614, slightly lower than with Polynomial and Fourier-based augmentation. XGBoost also declined to an R² of 0.99677 and MSE of 2,071.99. CatBoost dropped more noticeably to an R² of 0.97975 and MSE of 12,978.48, suggesting misalignment with the generated data.

In contrast, LightGBM and Random Forest stacked with Linear Regression improved, with R² scores of 0.95879 and 0.99748, respectively, indicating that some tree-based models benefitted from the added variability. However, others struggled. k-Nearest Neighbours and Multilayer Perceptron, both stacked with Linear Regression, declined, with kNN showing an R² of 0.95981 and MSE of 25,761.55. AdaBoost and LSTM stacks also dropped significantly, with R² scores of 0.91043 and 0.92570.

The largest performance drop occurred in the Autoencoders stacked with Linear Regression model, which recorded an R² of 0.82454 and MSE of 112,464.75. This indicates a poor fit between the generated data and the model’s internal representations.

In summary, Autoencoder-based augmentation had mixed effects. It improved results for some models but hindered others, depending on how well the new feature space aligned with each model’s learning approach.

Comparative analysis of deep learning models with optimal augmentation

This subsection compares the performance of deep learning models with Polynomial and Fourier Expansion inspired augmentation (A1 or 1) against Autoencoder-based augmentation (A2 or 2). The results in Table 4 show that A1 consistently enhanced model performance across key metrics, particularly for the GRU, LSTM, and Autoencoders + LR.

Among the models, the GRU achieved the highest performance, closely followed by the LSTM stacked with Linear Regression. The Autoencoders stacked with Linear Regression and MLP stacked with Linear Regression also delivered excellent results with Polynomial and Fourier Expansion inspired augmentation (A1), though their performance was slightly behind the recurrent models.

Overall, Polynomial and Fourier Expansion inspired augmentation (A1) emerged as the most effective strategy, offering notable improvements in accuracy and error reduction compared to Autoencoder-based augmentation (A2).

Optimization

Following augmentation, optimization was conducted using Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO), with the Polynomial and Fourier Expansion-inspired augmentation selected due to superior performance over autoencoder-based methods. This section presents the impact of these optimization algorithms on model performance, with detailed results in Tables 5, 8 and 9 and Appendix Supplementary Tables 8–10.

PSO and GWO led to consistent improvements across error metrics (MSE, RMSE) and R² scores, particularly benefiting ensemble and tree-based models. Due to the high computational cost, only the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) stacked with Linear Regression was optimized among deep learning models, focusing on hidden layer neurons, activation functions, and regularization parameters.

Particle swarm optimization analysis

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) demonstrated its effectiveness in significantly improving the predictive accuracy of the models, as evident in Table 5 and further detailed in Supplementary Table 8 of Appendix. The Decision Tree model’s MSE was reduced from 1926.21 in the baseline to 1625.8, while the RMSE decreased from 43.88 to 40.32. These improvements, though modest, indicate better handling of outliers and increased prediction stability.

The K-Nearest Neighbour (kNN) model stacked with Linear Regression showcased the most dramatic improvement under PSO. Its MSE decreased from 4792.83 to 990.88, and RMSE dropped from 69.23 to 31.47. This significant enhancement reflects PSO’s ability to refine hyperparameters effectively, improving the model’s sensitivity to underlying data patterns.

Among the advanced models, CatBoost and Gradient Boosting stacked with Linear Regression excelled with PSO optimization. CatBoost achieved an R² Score of 0.99923 and an MSE of 487.71, while Gradient Boosting stacked with Linear Regression reached an R² Score of 0.99905 and an MSE of 606.98. These results highlight the ability of PSO to complement ensemble models by fine-tuning their complex parameter spaces.

Grey Wolf optimization analysis

Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) also proved to be an effective optimization technique, yielding comparable and, in some cases, slightly better results than PSO, as evident in Table 8 and further detailed in Supplementary Table 9 of Appendix. The Decision Tree model maintained a similar level of improvement, with an MSE of 1625.8 and RMSE of 40.32, reflecting the stability of the optimization method.

The LightGBM model demonstrated notable gains under GWO, with its MSE reduced from 29386.43 in the baseline to 6549.0062. However, while the improvement in error metrics was substantial, the Max Error remained relatively high, suggesting limitations in addressing extreme outliers.

GWO also showcased its strengths with neural network-based models such as Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) stacked with Linear Regression. The R² Score of this model reached 0.99927 with an MSE of 466.06, representing slight but meaningful improvements over PSO. These results affirm GWO’s ability to explore hyperparameter configurations effectively, particularly in high-dimensional parameter spaces.

Overall, both optimization techniques improved the models’ predictive capabilities, with GWO slightly outperforming PSO in certain instances. The choice between these methods depends on the specific requirements of the task, such as computational efficiency and the complexity of the model’s parameter space.

Comparative analysis of predictive models with optimal optimization techniques

A comparative analysis of Particle Swarm Optimization (O1) and Grey Wolf Optimization (O2) across models is presented in Table 9, with further details in Appendix Supplementary Table 10. Both methods enhanced predictive accuracy, though their effectiveness varied with model complexity.

O1 performed well with traditional and ensemble models. The Decision Tree model achieved an MSE of 1625.81 with an R² of 0.99746, and Random Forest with Linear Regression also showed consistent improvement. CatBoost, optimized with O1, recorded one of the best results with an MSE of 487.71 and the lowest Max Error of 93.33, demonstrating O1’s efficiency in tuning simpler architectures.

In contrast, O2 was more effective for complex models. The MLP stacked with Linear Regression achieved the highest R² of 0.99927 and the lowest RMSE of 21.59. LightGBM showed a substantial MSE reduction from 29386.43 to 6549.01 under O2, though the Max Error remained high. XGBoost also benefited from O2, reinforcing its suitability for models with extensive parameter spaces.

In summary, O1 is more effective for traditional and ensemble models, while O2 offers better results for deep or complex architectures.

Overall results analysis

This section provides a comprehensive discussion of the overall results, including a detailed analysis of the performance of machine learning and deep learning models with enhanced configurations. The two subsections, 4.5.1 and 4.5.2, examine the performance improvements resulting from augmentation and optimization techniques and compare the baseline implementation to enhanced configurations.

Performance analysis of machine learning and deep learning models with enhanced configurations

The application of augmentation and optimization techniques, as summarized above, significantly improved the predictive performance of the models. Table 10 presents the results of the machine learning and deep learning models after incorporating these enhancements. A detailed study of this is provided in Supplementary Table 11 of the Appendix.

Notably, the models demonstrated substantial improvements in predictive accuracy and error minimization. For example, Gradient Boosting stacked with Linear Regression, CatBoost, and MLP stacked with Linear Regression achieved near-perfect R² Scores, reflecting their ability to effectively capture complex relationships in the dataset. Among the deep learning models, GRU and LSTM (stacked with LR) also performed well, demonstrating their suitability for handling temporal and sequential data.

Comparative analysis of baseline implementation versus enhanced configurations of Top-Performing models

The performance analysis in Table 10 identified the five best-performing models from the final implementation with enhanced configurations. These models include Gradient Boosting stacked with Linear Regression, CatBoost, XGBoost, MLP stacked with Linear Regression, and GRU. To further assess the impact of augmentation and optimization techniques, Table 11 presents the baseline results of these models in their direct implementation (without augmentation or optimization), while Table 12 provides their enhanced implementation results.

In their baseline configurations (Table 11), these models displayed strong predictive capabilities. For instance, CatBoost and XGBoost achieved high R² Scores of 0.99876 and 0.99893, respectively, while Gradient Boosting stacked with Linear Regression exhibited competitive performance with an RMSE of 58.22. However, due to the absence of augmentation and optimization techniques, error metric such as MSE were relatively higher.

In contrast, the enhanced implementations (Table 12) demonstrated substantial improvements across all metrics. Gradient Boosting stacked with Linear Regression saw its RMSE drop from 58.22 in the baseline to 24.63 in the enhanced configuration, coupled with a near-perfect R² Score of 0.99905. Similarly, CatBoost showed minor gains, achieving an RMSE reduction from 28.12 to 22.08 and an R² Score increase from 0.99876 to 0.99923. MLP stacked with Linear Regression also benefitted, with its RMSE decreasing from 37.02 to 21.58 and MAE reducing from 21.2 to 13.14. The GRU model, also exhibited an improvement, achieving a higher R² Score and lower error metrics in its enhanced configuration.

While the baseline configurations of the selected models already demonstrated robust performance, the enhancements achieved through augmentation and optimization resulted in significantly better accuracy, lower error metrics, and greater generalization. These findings reaffirm the value of incorporating advanced methodologies to optimize machine learning and deep learning models for real-world applications.

Visual insights into the performance of enhanced models for specific heat capacity prediction

The visual evaluation of the optimally enhanced top 5 models offers critical insights into their predictive performance for specific heat capacity under diverse input conditions. Figure 12 presents the Actual versus Predicted plots, where a close alignment of data points along the 45-degree diagonal line is evident for all five models. This strong adherence confirms high predictive accuracy. Notably, this alignment is consistent across the entire range of specific heat capacity values, from the lowest to the highest, demonstrating that the models are robust and generalize well rather than just modeling the mean. Figure 13 compares the distribution of actual and predicted values. The plots demonstrate that the enhanced models closely replicate the actual multimodal distribution curves of the dataset, which includes a primary peak as well as a distinct secondary cluster at lower specific heat values. This indicates a strong generalization capability, as the models have successfully captured the underlying data’s complex structure, not just its central tendency. The residual analysis in Fig. 14 provides further validation of model reliability. For all top models, residuals are predominantly centred around zero and appear randomly scattered, which suggests low bias and a uniform error distribution (homoscedasticity). The original observation of occasional outliers, particularly for CatBoost and MLP stacked with Linear Regression at higher specific heat capacity values, is also confirmed. These non-systematic errors likely correspond to more complex or rare data points within the dataset that are inherently more difficult to predict. Additional evaluation metrics are visualized in Figs. 15 and 16, and 17. The R² scores in Fig. 15 visually highlight the near-perfect fit for all the best-performing models, reinforcing the qualitative assessment from Fig. 12. Figures 16 and 17, which plot the various error metrics, allow for a more granular comparison. They visually illustrate the consistently low errors (both percentage and absolute) across the models. While all models perform well, these plots also reveal the subtle but consistent advantages of certain models, such as CatBoost and MLP stacked with Linear Regression, which show visibly lower error bars. Collectively, these visual and quantitative analyses confirm the effectiveness of the proposed enhancements in improving model performance, high fidelity, and robustness.

Computational performance analysis of top enhanced models

Table 13 summarizes the computational performance of the top five models based on prediction accuracy, including key metrics such as training time, testing time, average inference time, and model size.

Among the top models, Gradient Boosting stacked with Linear Regression demonstrates efficient training (1.23 s) but has the largest model size (1,123.798 KB). CatBoost is fast to train (0.528 s) and has a relatively small model size (482.009 KB). XGBoost has the fastest training time (0.2 s), though it has a slightly larger model size (638.161 KB). In comparison, MLP stacked with Linear Regression requires longer training time (20.44 s) but has a moderate model size (482.428 KB). GRU, while having the longest training time (1643.39 s), has the smallest model size (317.670 KB) but higher testing time (0.62 s).

Overall, CatBoost and XGBoost are the most computationally efficient due to their smaller training times and moderate sizes, while MLP stacked with Linear Regression and GRU show higher computational demands.

Comprehensive analysis of specific heat predictions

The top five enhanced models—XGBoost, CatBoost, Gradient Boosting stacked with Linear Regression, MLP stacked with Linear Regression, and GRU—exhibit high accuracy in predicting specific heat capacity values across various nanofluids. Figure 18 presents the overall Actual versus Predicted plot, where data points closely align with the 45-degree line, indicating minimal deviation and high predictive fidelity. Supplementary Fig. 4 in the Appendix further compares the predicted and experimental values for each nanofluid, offering a detailed model-wise performance view and analysis.

Supplementary Fig. 5 in the Appendix illustrates the effect of temperature on predicted specific heat capacity across different nanofluids. While the Supplementary Fig. 6 in Appendix illustrates the effect of volume concentration on predicted specific heat capacity across different nanofluids.

Although a direct numerical comparison with existing literature would be desirable, it was not feasible in this study due to the use of a distinct dataset with different experimental parameters, nanoparticle concentrations, and operating conditions. The studies reported in the literature vary significantly in terms of data sources, preprocessing methods, and model input variables, which makes one-to-one metric comparison unreliable. However, a qualitative assessment indicates that the present model exhibits consistent trends with previous findings—specifically, the predicted thermal behavior and sensitivity patterns align with the general relationships reported in earlier works. This confirms that the developed framework produces physically consistent and robust predictions, even under differing dataset conditions.

Conclusion

This study successfully demonstrated the application of machine learning and deep learning models for accurately predicting the specific heat capacity of nanofluids. By leveraging twelve ML and DL models, along with stacking approaches and advanced optimization techniques, the study achieved highly precise predictions, with the MLP + Linear Regression model emerging as the top performer (R² = 0.99927, MSE = 406.06, RMSE = 21.58). Among standalone models, XGBoost and CatBoost exhibited strong performance, highlighting the effectiveness of gradient boosting techniques in capturing nonlinear relationships within nanofluid datasets. The integration of data augmentation techniques, specifically Polynomial and Fourier Expansions inspired and Autoencoders-based, provided mixed results. While Polynomial and Fourier Expansion inspired augmentation significantly improved model accuracy, Autoencoder-based augmentation showed mixed results, with certain models experiencing performance degradation. This suggests that augmentation strategies should be carefully selected based on the specific characteristics of the model architecture and dataset. Furthermore, the use of Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) for hyperparameter tuning significantly enhanced model performance. PSO optimization improved the CatBoost model to an R² of 0.99923 with an MSE of 487.71, while GWO further optimized the MLP + LR model to achieve an R² of 0.99927 with an MSE of 466.06. The LightGBM model saw one of the most dramatic improvements under GWO, reducing its MSE from 29386.43 to 6549.006 and RMSE from 171.42 to 80.92. These results underscore the effectiveness of nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithms in fine-tuning complex models. Overall, the findings of this study highlight the potential of advanced ML and DL techniques in modeling the thermophysical properties of nanofluids with high precision. The hybrid approach combining stacking, augmentation, and metaheuristic optimization proved highly effective in refining predictive capabilities. Future research can explore the incorporation of more sophisticated deep learning architectures, alternative augmentation strategies, and hybrid optimization frameworks to further enhance predictive accuracy. Additionally, applying this methodology to other thermophysical properties of nanofluids, such as thermal conductivity and viscosity, could broaden its industrial and engineering applications.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during this study is publicly available at https://github.com/AI4A-lab/Nanofluid-Specific-Heat-Prediction-Dataset. The code is publicly available on GitHub by accessing the following link: https://github.com/AI4A-lab/Advanced-Nanofluid-Heat-Capacity-Prediction_Hybrid-ML-DL.

References

Çolak, A. B., Yıldız, O., Bayrak, M. & Tezekici, B. S. Experimental study for predicting the specific heat of water- based Cu-Al2O3 hybrid nanofluid using artificial neural network and proposing new correlation. Int. J. Energy Res. 44 (9), 7198–7215 (2020).

Wei, H., Zhao, S., Rong, Q. & Bao, H. Predicting the effective thermal conductivities of composite materials and porous media by machine learning methods. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 127, 908–916 (2018).

Mohanraj, M., Jayaraj, S. & Muraleedharan, C. Applications of artificial neural networks for thermal analysis of heat exchangers–a review. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 90, 150–172 (2015).

Chen, K., Hu, J., Zhang, Y., Yu, Z. & He, J. Fault location in power distribution systems via deep graph convolutional networks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 38 (1), 119–131 (2019).

Khan, M. F. I. et al. High-Fidelity Reconstruction of 3D Temperature Fields Using Attention-Augmented CNN Autoencoders with Optimized Latent Space (IEEE Access, 2024).

Jamei, M. & Said, Z. Recent Advances in the Prediction of Thermophysical Properties of Nanofluids Using Artificial Intelligence 203–232 (Hybrid Nanofluids, 2022).

Basu, A., Saha, A., Banerjee, S., Roy, P. C. & Kundu, B. A review of artificial intelligence methods in predicting thermophysical properties of nanofluids for heat transfer applications. Energies 17 (6), 1351 (2024).

Maleki, A., Haghighi, A. & Mahariq, I. Machine learning-based approaches for modeling thermophysical properties of hybrid nanofluids: A comprehensive review. J. Mol. Liq. 322, 114843 (2021).

Montgomery, D. C., Peck, E. A. & Vining, G. G. Introduction To Linear Regression Analysis (Wiley, 2021).

Jordan, M. I. & Mitchell, T. M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 349 (6245), 255–260 (2015).

Alarifi, I. M., Nguyen, H. M., Bakhtiyari, N., Asadi, A. & A., & Feasibility of ANFIS-PSO and ANFIS-GA models in predicting thermophysical properties of Al2O3-MWCNT/oil hybrid nanofluid. Materials 12 (21), 3628 (2019).

Zhou, H. et al. Combination of group method of data handling neural network with multi-objective Gray Wolf optimizer to predict the viscosity of MWCNT-TiO2-oil SAE50 nanofluid. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 64, 105541 (2024).

Yang, X. S. Metaheuristic Optim. Scholarpedia, 6(8), 11472. (2011).

Yang, L. & Shami, A. On hyperparameter optimization of machine learning algorithms: theory and practice. Neurocomputing 415, 295–316 (2020).

Said, Z., Sharma, P., Elavarasan, R. M., Tiwari, A. K. & Rathod, M. K. Exploring the specific heat capacity of water-based hybrid nanofluids for solar energy applications: A comparative evaluation of modern ensemble machine learning techniques. J. Energy Storage. 54, 105230 (2022).

Alade, I. O., Abd Rahman, M. A. & Saleh, T. A. Predicting the specific heat capacity of alumina/ethylene glycol nanofluids using support vector regression model optimized with bayesian algorithm. Sol. Energy. 183, 74–82 (2019).

Oh, Y. & Guo, Z. Applicability of machine learning techniques in predicting specific heat capacity of complex nanofluids. Heat. Transf. Res., 55(3), 39–60 (2024).

Deymi, O. et al. Employing ensemble learning techniques for modeling nanofluids’ specific heat capacity. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transfer. 143, 106684 (2023).

Deymi, O. et al. Toward empirical correlations for estimating the specific heat capacity of nanofluids utilizing GRG, GP, GEP, and GMDH. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 20763 (2023).

Deymi, O. et al. On the evaluation of mono-nanofluids’ density using a radial basis function neural network optimized by evolutionary algorithms. Therm. Sci. Eng. Progress. 53, 102750 (2024).

Deymi, O. et al. Innovative mathematical correlations for estimating mono-nanofluids’ density: insights from white-box machine learning. Results Phys. 73, 108248 (2025).

Esfe, M. H., Motallebi, S. M. & Toghraie, D. Investigation the effects of different nanoparticles on density and specific heat: prediction using MLP artificial neural network and response surface methodology. Colloids Surf., A. 645, 128808 (2022).

Çolak, A. B. Developing optimal artificial neural network (ANN) to predict the specific heat of water-based yttrium oxide (Y 2 O 3) nanofluid according to the experimental data and proposing new correlation. Heat. Transf. Res., 51(17), 1565–1586 (2020).

Çolak, A. B. Experimental analysis with specific heat of water-based zirconium oxide nanofluid on the effect of training algorithm on predictive performance of artificial neural network. Heat. Transf. Res., 52(7), 67–93 (2021).

Gupta, A. K. & Mathur, P. Predicting Specific Heat Capacity of Nanofluids Using Artificial Neural Network for Al2O3 particle with EG/Water based solution. In 2023 10th International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Computer Science and Informatics (EECSI) pp. 295–299 (IEEE, 2023).

Mishra, S. R., Pattnaik, P. K., Baithalu, R., Ratha, P. K. & Panda, S. Predicting heat transfer performance in transient flow of CNT nanomaterials with thermal radiation past a heated spinning sphere using an artificial neural network: A machine learning approach. Partial Differ. Equations Appl. Math. 12, 100936 (2024).

Boldoo, T., Lee, M., Kang, Y. T. & Cho, H. Development of artificial neural network model for predicting dynamic viscosity and specific heat of MWCNT nanoparticle-enhanced ionic liquids with different [HMIM]-cation base agents. J. Mol. Liq. 341, 117356 (2021).

Chaudhary, L. et al. Machine learning based prediction of specific heat capacity for half-Heusler compounds. AIP Adv., 15(1), 015306 https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0239714 (2025).

Liu, X., Gao, J., Chen, Y., Fu, Y. & Lei, Y. Machine learning-assisted modeling study on the density and heat capacity of ionic liquid-organic solvent binary systems. J. Mol. Liq. 390, 122972 (2023).

Sajjad, U. et al. A deep learning method for estimating the boiling heat transfer coefficient of porous surfaces. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 145, 1911–1923 (2021).

Albdour, S. A., Addad, Y., Rabbani, S. & Afgan, I. Machine learning-driven approach for predicting the condensation heat transfer coefficient (HTC) in the presence of non-condensable gases. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow. 106, 109330 (2024).

Elshehabey, H. M., Aly, A. M., Lee, S. W. & Çolak, A. B. Integrating artificial intelligence with numerical simulations of Cattaneo-Christov heat flux on thermosolutal convection of nano-enhanced phase change materials in Bézier-annulus. J. Energy Storage. 82, 110496 (2024).

Knoerzer, K. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Simplified Adiabatic Compression Heating Prediction: Comparing the Use of Artificial Neural Networks with Conventional Numerical Approach Vol. 91, 103546 (Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, 2024).

Adun, H., Wole-Osho, I., Okonkwo, E. C., Kavaz, D. & Dagbasi, M. A critical review of specific heat capacity of hybrid nanofluids for thermal energy applications. J. Mol. Liq. 340, 116890 (2021).

Çolak, A. B., Yildiz, O., Bayrak, M., Celen, A. & Wongwises, S. Experimental study on the specific heat capacity measurement of water-based al2o3-cu hybrid nanofluid by using differential thermal analysis method. Curr. Nanosci. 16 (6), 912–928 (2020).

Alade, I. O., Abd Rahman, M. A. & Saleh, T. A. Modeling and Prediction of the Specific Heat Capacity of Al2 O3/water Nanofluids Using Hybrid Genetic algorithm/support Vector Regression Model Vol. 17, 103–111 (Nano-Structures & Nano-Objects, 2019).

Alade, I. O., Oyehan, T. A., Popoola, I. K., Olatunji, S. O. & Bagudu, A. Modeling thermal conductivity enhancement of metal and metallic oxide nanofluids using support vector regression. Adv. Powder Technol. 29 (1), 157–167 (2018).

Mathur, P., Gupta, A. K., Panwar, D. & Sharma, T. K. Soft computing approaches for prediction of specific heat capacity of hybrid nanofluids. Expert Syst., 41(1), e13471 https://doi.org/10.1111/exsy.13471 (2024).

Sheikhpour, M., Arabi, M., Kasaeian, A., Rokn Rabei, A. & Taherian, Z. Role of nanofluids in drug delivery and biomedical technology: Methods and applications. Nanotechnol. Sci. Appl. 47–59 (2020).

Rodríguez, P., Bautista, M. A., Gonzalez, J. & Escalera, S. Beyond one-hot encoding: lower dimensional target embedding. Image Vis. Comput. 75, 21–31 (2018).

Ali, P. J. M., Faraj, R. H., Koya, E., Ali, P. J. M. & Faraj, R. H. Data normalization and standardization: a technical report. Mach. Learn. Tech. Rep. 1 (1), 1–6 (2014).

Ying, X. An overview of overfitting and its solutions. In Journal of physics: Conference series Vol. 1168, p. 022022 (IOP Publishing, 2019), February.

Xu, Q. et al. Fourier-based augmentation with applications to domain generalization. Pattern Recogn. 139, 109474 (2023).

Farnebäck, G. Polynomial expansion for orientation and motion estimation (Doctoral dissertation, Linköping University Electronic Press, 2002).

Shu, C. & Chew, Y. T. Fourier expansion-based differential quadrature and its application to Helmholtz eigenvalue problems. Commun. Numer. Methods Eng. 13 (8), 643–653 (1997).

Bakiskan, C., Cekic, M., Sezer, A. D. & Madhow, U. A Neuro-Inspired Autoencoding Defense Against Adversarial Perturbations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.10867 (2020).

Fister, I. Jr, Yang, X. S., Fister, I., Brest, J. & Fister, D. A brief review of nature-inspired algorithms for optimization. ArXiv Preprint arXiv :13074186 arXiv:1307.4186 (2013).

Babalola, A. E., Ojokoh, B. A. & Odili, J. B. A review of population-based optimization algorithms. In 2020 International Conference in Mathematics, Computer Engineering and Computer Science (ICMCECS) pp. 1–7 (IEEE, 2020).

Bonyadi, M. R., Michalewicz, Z. & Li, X. An analysis of the velocity updating rule of the particle swarm optimization algorithm. J. Heuristics. 20, 417–452 (2014).

Faris, H., Aljarah, I., Al-Betar, M. A. & Mirjalili, S. Grey Wolf optimizer: a review of recent variants and applications. Neural Comput. Appl. 30, 413–435 (2018).

Rojas, R. & Rojas, R. The backpropagation algorithm. Neural networks: a systematic introduction. 149–182. (1996).

De Ville, B. Decision trees. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Comput. Stat. 5 (6), 448–455 (2013).

Bertsimas, D., Dunn, J. & Paschalidis, A. Regression and classification using optimal decision trees. In 2017 IEEE MIT undergraduate research technology conference (URTC) pp. 1–4 (IEEE, 2017).

Rigatti, S. J. Random forest. J. Insur. Med. 47 (1), 31–39 (2017).

Song, Y., Liang, J., Lu, J. & Zhao, X. An efficient instance selection algorithm for k nearest neighbor regression. Neurocomputing 251, 26–34 (2017).

Bentéjac, C., Csörgő, A. & Martínez-Muñoz, G. A comparative analysis of gradient boosting algorithms. Artif. Intell. Rev. 54, 1937–1967 (2021).