Abstract

Determining blood flow in major cerebral arteries is crucial for understanding cerebrovascular diseases. This study focused on comparing flow volumes derived from the signal intensity gradient (SIG) of Time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography (TOF-MRA), referred to as SIG volume, and two-dimensional phase-contrast MR (PC-MR) and assessing their correlation in both experimental and human studies. The SIG volume of TOF-MRA could be calculated based on the concept of SIG as velocity gradient correspondingly. This research encompassed an experimental study as well as a prospective cross-sectional study involving human participants. Flow volumes were measured in four varying-sized tubes using PC-MR and TOF-MRA in the experimental study. The internal carotid and vertebral arteries were examined in relatively healthy subjects and the data were prospectively collected. Pearson’s correlation coefficients and coefficients of determination (R²) were calculated, and Bland-Altman plots were used to assess the agreement between the two methods. In the tubal experiments (n = 80), the correlation coefficient of flow volumes measured by two modalities was 0.98, with an R2 of 0.96 (p < 0.001). In the human study, 50 internal carotid and 49 vertebral arteries from 25 subjects (mean age ± standard deviation: 63.3 ± 11.5 y) were examined. The coefficient for the cerebral arteries was 0.93, with an R2 of 0.87 (p < 0.001). Calculated SIG volumes of TOF-MRA were highly correlated with the blood flow volume from PC-MR in both tubal experiments and human studies on extracranial cerebral arteries.

This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04585971, Date of Registration: 2020-10-14).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Measuring cerebral blood flow (CBF) is essential for understanding the dynamics of cerebrovascular networks, particularly in relation to neurovascular coupling and autoregulatory mechanisms1,2. CBF reflects how well blood supply meets the metabolic demands of neural tissue, making it a critical parameter for assessing brain function, detecting pathology, and monitoring therapeutic responses. Accurate determination of local and global CBF responses over the circle of Willis necessitates understanding the blood flow distribution across arterial levels, such as the internal carotid artery (ICA) and vertebral artery (VA). These arteries, like the pial arterioles, buffer perfusion pressure surges, respond to arterial blood gases3, and are associated with cortical thinning4.

Doppler ultrasonography and phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (PC-MR) measure arterial flow volumes and total CBF. PC-MR estimates mean velocity, while Doppler ultrasound measures peak velocity within a voxel5. Some studies have reported significantly higher values with Doppler ultrasonography than PC-MR6,7, though other studies have found no significant difference8. Most studies used the flow volumes of both ICAs and VAs for total CBF measurement6,7,8,9,10, while some replaced the two VAs with one basilar artery11. Additionally, PC-MR has been used to measure flow volumes of all the cerebral arteries, providing reference values for healthy young and old subjects9.

While both PC-MR and Doppler ultrasonography can assess CBF, PC-MR may be more appropriate for measuring flow volumes in cerebral arteries. Accurate CBF measurement necessitates assessing ICA flow beyond the carotid bulb to avoid overestimations caused by the bulbous region. Anatomical limitations, such as the overlying mandible bone, often impede ultrasonographic access to the distal ICA. Even with transcranial Doppler’s superior penetration, challenges with the temporal window remain, particularly in elderly patients, limiting its applicability for precise ICA measurements12.

Accurate determination of arterial flow volume requires measuring both flow velocity and vessel radius. Although PC-MR theoretically enables in vivo assessment of flow velocity and arterial volume13, the procedure is technically demanding. It involves integrating time of flight-magnetic resonance angiography (TOF-MRA) to capture vessel geometry, selecting appropriate anatomical levels for measurement, and applying velocity encoding (VENC) in conjunction with cardiac gating14. Consequently, there is a need for simplified and more accessible methods for evaluating arterial flow volume in clinical practice.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the signal intensity gradient (SIG) derived from TOF-MRA correlates significantly with arterial wall shear stress, as calculated using either computational fluid dynamics (CFD)15 or PC-MR16. This correlation underscores SIG’s potential as a noninvasive surrogate marker for hemodynamic forces acting on the arterial wall. Since the arterial wall SIG conceptually reflects the shear rate or velocity gradient according to infinitesimal calculus, additional hemodynamic parameters may be inferred from SIG. In this study, we introduce a method to estimate flow volume based on TOF-MRA SIG, termed “SIG volume”. We evaluated this method by comparing it with PC-MR in both tube experiments and human studies involving the carotid and vertebral arteries. Mean SIG and vessel radius values were obtained from the tube and arterial sections, and correlation metrics, including the coefficient of determination (R2), were presented for each experimental condition.

Materials and methods

This study conducted both an experimental investigation and a prospective cross-sectional study involving human subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The Ethics Review Committee of Jeonbuk National University Hospital approved this study (CUH2020-07-024-011), registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04585971). Additionally, the committee confirmed that the study adhered to relevant guidelines and regulations.

Experimental study

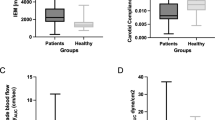

A phantom study investigated flow volumes using PC-MR and TOF-MRA SIG as a function of flow rate (Fig. 1)15,16. Flow phantoms with variable steady flow rates (0.06–12.75 mL/s) were constructed using four types of flexible tubing (4, 6.5, 8, and 11 mm inner diameters), which could be controlled separately. Tap water (T1 time, 2.1–3.5 s) was pumped into a buffer reservoir (outside of the MR scanning room) to provide continuous flow at the outlet of the water hose and the imaging region of a 3.0-T MR using a SENSE 32-channel head coil (Philips Medical Systems, Achieva, The Netherlands). For each tube, water flow measurements were performed at 20 distinct pump-controlled flow rates using PC-MR and TOF-MRA. Measurements obtained from each method were directly compared across all tubes. A 1900 mL MR phantom, consisting of a plastic bottle containing 3.75 g NiSO4(H2O)6 + 5 g NaCl per 1000 mL of distilled H2O (T1, 40–120 ms), was placed between the tubes.

Tube study examining flow volumes using PC-MR and TOF-MRA SIG as a function of flow rate. (a) A 3-dimensional (3D) TOF-MRA image with a transverse plane used for flow volume measurement in PC-MR. (b) Semiautomatic identification of the region of interest at the transverse plane. (c,d) 3D reconstructions of tubes from TOF-MRA, demonstrating measurement methods over a short segment (c) and long segment covering neighboring tubal segment (d). PC-MR, phase-contrast magnetic resonance; TOF-MRA, time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography; SIG, signal intensity gradient.

Human study

Subjects visiting Jeonbuk National University Hospital for routine health checks were prospectively screened between March and June 2021. Participants who met the inclusion criteria were selected initially. The inclusion criteria were (1) adults aged 18 years or older, (2) individuals who underwent both carotid ultrasonography and TOF-MRA, and (3) those who provided informed consent to participate in the study. Medical information, such as age, sex, smoking history, and current alcohol consumption, was recorded. Patients with a history of smoking were categorized accordingly. Hypertension was defined by a previous diagnosis, current use of antihypertensive medication, or a stable blood pressure reading of 140/90 mmHg or higher. Type 2 diabetes mellitus was identified by a history of diabetes, current medication, or fasting blood glucose levels of 126 mg/dL or higher on more than two occasions. Serum lipid profiles were analyzed using standard methods.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded subjects with these characteristics: (1) more than one ultrasound-defined ICA stenosis > 50% with ICA peak systolic velocity (PSV) ≥ 125 cm/s or VA stenosis > 50% stenosis with PSV ≥ 110 cm/s while visible plaque or luminal narrowing17; (2) atrial fibrillation; (3) prior carotid or vertebral artery revascularization, including endarterectomy or stenting; (4) previous cerebrovascular event, including transient ischemic attacks; and (5) abnormal hepatic (aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, and albumin), renal (creatinine and glomerular filtration rate), or hematologic (complete blood count, thrombin time, prothrombin time, and activated partial thromboplastin time) laboratory findings.

Phase contrast (PC) MRI and TOF-MRA

Blood flow was calculated using a 3.0T MR with a SENSE 32-channel head coil (Philips Medical Systems, Achieva) through PC-MR. A three-dimensional (3D) TOF-MRA, covering the ICAs and cervical segment of the VAs, was performed to identify the proper transverse plane for measuring blood flow in the ICAs and VAs (Fig. 2). The TOF-MRA parameters were TR = 23.0 ms, TE = 3.5 ms, resolution = 300 × 220, field of view (FOV) = 180 mm2, 160 slices, flip angle (FA) = 20.0°, and scan duration = 1 m 53 s.

Human studies on flow volumes using PC-MR and TOF-MRA SIG. (a) A 3D TOF-MRA image with a transverse plane used to measure flow volume in PC-MR. (b,c) 3D reconstructions of the ICAs and VAs from TOF-MRA, demonstrating measurement methods over a short segment (b) and a long segment covering the neighboring arterial segment (c). ICA, internal carotid artery; VA, vertebral artery.

The transverse plane was positioned in the cervical segments of the ICAs and VAs within straight sections with consistent diameters to select laminar flow segments for each vessel. Cardiac-gated PC images were acquired using a pulse oximetry sensor. The parameters were: TR = 13.0 ms, TE = 7.9 ms, in-plane resolution = 128 × 128, slice thickness = 5 mm, FOV = 150 mm2, FA = 10.0°, signal average (NEX) = 1, and total scan time = 2 m 53 s. VENC was oriented from the caudal to the cephalic direction to maximize blood velocity near the vessel wall and minimize phase wrapping. Blood flow was measured with a VENC of 100 cm/s initially; if the phase wrap or velocity aliasing occurred, the VENC limit was adjusted, and the velocity was remeasured in the individual.

The region of interest (ROI) was delineated semiautomatically using software (extended MR WorkSpace 2.6.3.4, Philips Medical Systems). Initially drawn manually by the researcher, the ROI was refined into a smooth contour, with real-time adjustments in response to phase image changes using wall-edge detection and wall tracking. Mean flow velocities and radii from PC-MR were obtained for both tube and human studies. The arterial wall SIG and radius were measured at corresponding PC-MR levels for both the tubes and cerebral arteries over the short segment (< 5 mm in length), as shown in Figs. 1c and 2b. Measurements were repeated over the long segment (≥ 5 mm), as shown in Figs. 1d and 2c. All data were analyzed using FDA-approved semi-automated software (VINT; MediIMG, Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea), as previously reported16.

Calculating flow volume in the arteries and tubes

Flow volumes were determined using PC-MR based on the mean flow velocities and radii (R) along the tube or arterial segments, as follows:

Flow volume (cm3/sec) = area (πR2) ✕ mean flow velocity

SIG volumes from TOF-MRA were calculated using the mean values of the arterial SIG and radius. The mean SIG values demonstrated significant correlations with wall shear stress measured using PC-MR16. Conceptually, SIG corresponds to the shear rate or velocity gradient (velocity/radius, V/R). Wall shear stress (τwall) was determined by multiplying whole blood viscosity (\(\mu\)) and shear rate (V/R) or flow volume (Q) from the Hagen-Poiseuille equation as follows18:

The SIG volume of TOF-MRA can be defined as follows, with the shear rate (V/R) replaced by the mean value of SIG in each artery or tube:

Compared to the 2D PC-MR in which the flow volume was calculated using the whole signals from the arterial sections, the SIG volume of TOF-MRA is determined by the signals only from the near arterial wall. So, the SIG volumes of TOF-MRA were measured over short or long segments in both tubal and human studies to find out the regional effects. Total CBF was calculated as the sum of the measurements from both the ICAs and VAs in the PC-MR and TOF-MRA.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data for the clinical characteristics and laboratory findings of the participants were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or percentage, as appropriate. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test assessed distributional adequacy. Differences in continuous variables were evaluated using a t-test or analysis of variance. The SIG volume derived from TOF-MRA was measured in two ways: over a short PC-MR-corresponding segment and a long segment covering the corresponding and neighboring arterial segments. Pearson’s correlation coefficients, 95% confidence intervals (CI), and coefficients of determination (R²) represented the proportion of variance in values measured using PC-MR and TOF-MRA. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and Bland-Altman plots assessed reliability and agreement between the measurements. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20 (SPSS, Armonk). For a determination of sample size, the G*Power 3.1 was used. When the significance level required for correlation analysis is 0.05, the expected correlation coefficient is 0.7, the power is 0.9 according to Cohen’s law, and the number of variables is set to 0, the minimum samples was expected to be 17. The dropout rate was considered to be 20%.

Results

Experimental study

Both PC-MR and TOF-MRA were conducted (n = 80) in the experiment involving four tubes of varying sizes (see Fig. 1). Flow volume measurements were conducted 20 times for each tube, using a range of predefined flow rate settings to assess performance across different conditions. The TOF-MRA scanned an average tubal length of 113.5 ± 0.5 mm (mean ± SD). SIG was measured in two ways depending on measured length: over a short segment of 4.3 ± 0.5 mm (3.8% of total tube length) (see Fig. 1c) and over a long segment of 85.4 ± 0.6 mm (75.3% of the tube scanned) (see Fig. 1d).

Flow volumes measured using PC-MR and TOF-MRA across all individual tube measurements demonstrated a strong correlation, with a correlation coefficient of 0.95 (95% CI: 0.90–0.97, R² = 0.90, p < 0.001) when SIG was measured over the short segment (Fig. 3a). The coefficient r increased to 0.98 (95% CI: 0.97–0.99, R2 = 0.96) with measurements over the long segment (Fig. 3b).

The radii measured by PC-MR and TOF-MRA were similar but significantly lower than the actual radii of the tubes (Table 1). Flow volumes measured by PC-MR and TOF-MRA increased significantly with larger tube radii. PC-MR measured higher tubal flow volumes than SIG volume for all tubes. No significant differences in SIG volume were observed between the short- and long-segment measurements.

Human study

We initially selected 78 of the 145 screened subjects for having relatively healthy carotid and vertebral arteries. Thirty-two consented to participate, with seven subsequently excluded (four withdrew consent, and three failed PC-MR measurements due to cardiac gating issues). Ultimately, 50 carotid and 49 vertebral arteries were examined in 25 subjects (Fig. S1). The mean age (± SD) was 63.3 ± 11.5 y; 9 participants (36.0%) were women, and the body mass index (kg/m2) was 23.1 ± 3.4, as detailed in the Table S1.

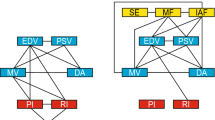

Flow volumes measured by PC-MR and TOF-MRA (using the long measurement) in the 99 internal carotid and vertebral arteries demonstrated a correlation coefficient of 0.93 (95% CI 0.90–0.95, R2 = 0.8661, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4a). Total CBF (using the long measurement) in the 25 subjects exhibited a correlation coefficient of 0.93 (95% CI 0.82–0.97, R2 = 0.86, p < 0.001), as illustrated in Fig. 4b. The more detailed descriptions in each artery were presented in Fig. S2. The correlation coefficient and R2 for the short measurement were 0.91 (95% CI 0.84–0.95) and 0.83 (p < 0.001), respectively (see Fig. S3). The mean length of the short and long measurements was 3.7 ± 0.3 mm and 19.1 ± 3.8 mm, respectively. No significant differences were observed in the radius and flow volume between the two methods (Table 2).

The radius of the cerebral arteries was not significantly different between PC-MR and TOF-MRA (all p-values > 0.1) (Table 3). In the long measurement (Fig. 2c), PC-MR measured significantly higher flow volumes than those of TOF-MRA in the left ICA but not in either the VAs or the right ICA. Consequently, the total CBF measured by PC-MR was significantly higher than that of TOF-MRA. The anterior circulation blood flow was 6.51 ± 1.69 ml/s, representing 70.6% of total CBF with PC-MR, and 5.47 ± 1.69 SIG·cm3, representing 68.6% with TOF-MRA.

Reliability assessment and method comparison

Bland-Altman plots were used to compare blood flow volume measurements in both ICAs and VAs using PC-MR and TOF-MRA (long measurement), as shown in Fig. S4. The graphical presentation of agreements in the cerebral arteries indicated that differences and variabilities were mostly within the upper and lower limits of agreement. Similar findings were observed with short measurements, as shown in Fig. S5. The SIG volume derived from TOF-MRA in the cerebral arteries showed strong agreement with PC-MR measurements, with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.95 (95% CI 0.84–0.98). Additionally, in tube experiments, SIG volume demonstrated excellent reproducibility across four scanning sessions, yielding an ICC of 0.97 (95% CI 0.92–0.99).

Discussion

This study demonstrated a strong correlation between flow volumes measured by PC-MR and TOF-MRA SIG, validated through both tubal experiments and human studies involving relatively healthy elderly participants. Long measurements over adjacent segments yielded robust results, with slightly higher correlation coefficients and R2 values in both tubal and human studies. The parameters of TOF-MRA in this study were consistent with clinical routine setting, not requiring additional scans and settings for blood flow estimation, which is a major advantage of SIG volume from TOF-MRA.

Assessment of cerebral arterial flow volumes plays a pivotal role in understanding neurovascular coupling and autoregulatory mechanisms. Such measurements hold clinical value across conventional settings, including the evaluation of headache19, cardiovascular disease risk prediction20, decision-making for interventions21, follow-up assessments22, and diagnostic evaluation in patients with altered mental status23 or neurodegenerative diseases24. Arterial flow volume can be assessed using Doppler ultrasonography and PC-MR. PC-MR is advantageous for measuring flow volumes in cerebral arteries because it can determine flow velocity and radius at any depth, irrespective of limitations imposed by the skull. However, transcranial Doppler or transcranial color Doppler penetrates the bony skull to provide flow velocity and direction but cannot measure the radius, thereby limiting flow volume calculation, even among individuals with a suitable temporal window.

The SIG volume derived from the TOF-MRA, is based on the wall shear stress equation, which was calculated using blood viscosity and shear rate (velocity gradient). Although the SIG volume is not directly measured, it serves as an indirect estimate based on quantitative imaging data. However, SIG volume from TOF-MRA exhibited significantly high correlation coefficients with PC-MR-measured flow volumes in tubal experiments and human studies, indicating promising results. Previous research has reported image-based flow-volume estimation using silent MRA, showing a significant correlation between arterial image intensity distributions and phase distributions by 2D PC-MR25. Further investigation of flow measurement by silent MRA, arterial spin labeling, and TOF-MRA is warranted.

Fundamentally, a key element of SIG volume from TOF-MRA is SIG, which represents the shear rate (or velocity gradient). Comprehensive details on the SIG calculation technique were described previously. Briefly, the SIG (SI/mm) was calculated as the difference in signal intensity between the arterial wall and inner points of maximum gradient, analogous to the calculation of the wall shear rate. The 3D geometry of the artery is then reconstructed to visualize the SIG, with MR signal intensities normalized to account for imaging equipment variations across datasets15. SIG showed a high correlation with wall shear stress calculated from both CFD and PC-MR15,16. Arterial WSS can be more accurate when blood viscosity is considered carefully26. Although the factor of blood viscosity was canceled out in the equation for SIG volume, subsequent studies needs to find out the effect of blood viscosity on SIG itself.

Another crucial factor is a radius. TOF-MRA is a first-line noninvasive imaging modality for geometric examination and was reported to be more sensitive and have a higher negative predictive value than 3D PC-MR27. This study is based on the principle of minimum work, where blood flow is proportional to the cube of the radius of the vessel at a specific point28, as derived from the Hagen–Poiseuille equation29. Although Murray’s cube law of minimal energy discharge has been challenged by a square law30,31, both methods have been carefully used for the entire arterial system32. Both cube and square laws were considered in calculating the SIG volume of TOF-MRA. However, the cube law consistently showed higher correlations with SIG volumes in tubal experiments and human studies (data not shown).

The SIG volumes of TOF-MRA demonstrated more reliable and robust correlations with those measured by PC-MR when assessed over longer segments (Figs. 1d and 2c). Techniques in PC-MR (both 2D and 4D flow MRI) are segmented and gated to the cardiac cycle, with velocity data acquired over whole arterial section33. Conversely, the SIG volume of TOF-MRA uses near wall signals only, which were generated by the inflow of fresh, unsaturated, fully magnetized spins into the imaging volume over multiple slab acquisitions34. The near wall MR signals and volume measurement from them could be dependent on regional characteristics of arterial flow and geometry15. Therefore, measuring arterial wall signals in 3D TOF-MRA is more appropriate over longer segments than shorter segments or single slices.

Although the SIG volume of TOF-MRA is an indirect measure through imaging data, it can be valuable for detecting hemodynamic changes in the cerebrovascular network, particularly in large arteries. Additionally, TOF-MRA SIG has demonstrated significant inter-individual and intraclass correlations. However, the SIG volume of TOF-MRA must be interpreted cautiously due to the inherent characteristics of TOF-MRA. Variations in the human arterial tree, such as bends and branches, can impede optimal artery scanning and accurate measurement over target segments. The SIG volume of TOF-MRA may benefit from guidance regarding the appropriate arterial level and length for measurement.

This study has several limitations. First, the human study was conducted at a single center with a small, homogenous participant group. It could be a potential source of bias, because flow volume rates and arterial geometry could not be controlled compared to the tubal experiments in which wide spectrum of flow volume could be applied more easily. Large scale, multi-center studies with more diverse ethnic groups are mandatory. Second, the study used only a single 3.0T MR machine; future research should employ various MR machines to validate these findings. Third, SIG shares limitations of TOF-MRA, such as washout of saturated spins and intravoxel dephasing effects35. These limitations may be more pronounced in younger subjects, who typically exhibit higher velocity profiles than older subjects. This study focused on an older population despite testing a wide range of radii and flow volumes in the tubal experiment. Further research is required to understand the variable profile of arterial velocity. Fourth, only vertically aligned and straight arterial segments were selected for measuring blood flow volume, making SIG volume of TOF-MRA unsuitable for other cerebral arteries with diverse courses far from the z-axis of the MR machines. Further studies are required to determine whether SIG volume can be reliably applied to other cerebral arteries, particularly those with a tortuous course. Fifth, the flow experiments lacked sufficient consideration of pulsatile flow, which is a critical feature of physiological conditions. To enhance the translational relevance, future research should incorporate the distinctive properties of blood flow. Finally, 2D PC-MR measured flow volume encoded through a 2D plane in one direction. Three-directional velocity encoding and 3D imaging could provide valuable information beyond 2D techniques24,36.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the arterial SIG volume of TOF-MRA was highly correlated with the blood flow volume calculated using PC-MR in both experimental and human studies. Further studies involving diverse populations and various MR scanners are necessary to generalize our findings.

Data availability

The corresponding author, Seul-Ki Jeong, will provide the data upon reasonable request from the reviewers or editors.

References

Willie, C. K., Tzeng, Y. C., Fisher, J. A. & Ainslie, P. N. Integrative regulation of human brain blood flow. J. Physiol. 592, 841–859. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2013.268953 (2014).

Claassen, J., Thijssen, D. H. J., Panerai, R. B. & Faraci, F. M. Regulation of cerebral blood flow in humans: physiology and clinical implications of autoregulation. Physiol. Rev. 101, 1487–1559. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00022.2020 (2021).

Faraci, F. M. & Heistad, D. D. Regulation of large cerebral arteries and cerebral microvascular pressure. Circ. Res. 66, 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.res.66.1.8 (1990).

Marshall, R. S. et al. Cortical thinning in High-Grade asymptomatic carotid stenosis. J. Stroke. 25, 92–100. https://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2022.02285 (2023).

Robertson, M. B., Kohler, U., Hoskins, P. R. & Marshall, I. Quantitative analysis of PC MRI velocity maps: pulsatile flow in cylindrical vessels. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 19, 685–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0730-725x(01)00376-9 (2001).

Ho, S. S., Chan, Y. L., Yeung, D. K. & Metreweli, C. Blood flow volume quantification of cerebral ischemia: comparison of three noninvasive imaging techniques of carotid and vertebral arteries. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 178, 551–556. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.178.3.1780551 (2002).

Oktar, S. O. et al. Blood-flow volume quantification in internal carotid and vertebral arteries: comparison of 3 different ultrasound techniques with phase-contrast MR imaging. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 27, 363–369 (2006).

Khan, M. A. et al. Measurement of cerebral blood flow using phase contrast magnetic resonance imaging and duplex ultrasonography. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 37, 541–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271678X16631149 (2017).

Zarrinkoob, L. et al. Blood flow distribution in cerebral arteries. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 35, 648–654. https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2014.241 (2015).

Scheel, P., Ruge, C., Petruch, U. R. & Schoning, M. Color duplex measurement of cerebral blood flow volume in healthy adults. Stroke 31, 147–150. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.31.1.147 (2000).

Vernooij, M. W. et al. Total cerebral blood flow and total brain perfusion in the general population: the Rotterdam scan study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 28, 412–419. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600526 (2008).

Lee, C. H., Jeon, S. H., Wang, S. J., Shin, B. S. & Kang, H. G. Factors associated with temporal window failure in transcranial doppler sonography. Neurol. Sci. 41, 3293–3299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04459-6 (2020).

Nayler, G. L., Firmin, D. N. & Longmore, D. B. Blood flow imaging by cine magnetic resonance. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 10, 715–722. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004728-198609000-00001 (1986).

Lotz, J., Meier, C., Leppert, A. & Galanski, M. Cardiovascular flow measurement with phase-contrast MR imaging: basic facts and implementation. Radiographics 22, 651–671. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiographics.22.3.g02ma11651 (2002).

Han, K. S. et al. Direct assessment of wall shear stress by signal intensity gradient from time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 7087086. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7087086 (2017).

Lee, C. H. et al. Validation of signal intensity gradient from TOF-MRA for wall shear stress by phase-contrast MR. J. Imaging Inf. Med. 37, 1248–1258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10278-024-00991-5 (2024).

Rice, C. J. et al. Ultrasound criteria for assessment of vertebral artery origins. J. Neuroimaging. 30, 45–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/jon.12674 (2020).

Papaioannou, T. G. & Stefanadis, C. Vascular wall shear stress: basic principles and methods. Hellenic J. Cardiol. 46, 9–15 (2005).

Ling, Y. H. et al. Association between impaired dynamic cerebral autoregulation and BBB disruption in reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. J. Headache Pain. 24, 170. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-023-01694-y (2023).

Lee, C. H., Kim, J. S., Rosenson, H. J., Yang, R. S., Jung, K. H. & W, and Association of carotid artery stenosis with cerebral artery signal intensity gradient on time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography. Front. Neurol. 16 https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2025.1576655 (2025).

Lee, W. J. et al. Impact of endothelial shear stress on the bilateral progression of unilateral Moyamoya disease. Stroke 51, 775–783. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.028117 (2020).

Lee, C. H. et al. Cerebral artery signal intensity gradient from Time-of-Flight magnetic resonance angiography and clinical outcome in lenticulostriate infarction: a retrospective cohort study. Front. Neurol. 14, 1220840. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1220840 (2023).

Johnson, T. W. et al. Cerebral blood flow hemispheric asymmetry in comatose adults receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Front. Neurosci. 16, 858404. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.858404 (2022).

Morgan, A. G., Thrippleton, M. J., Wardlaw, J. M. & Marshall, I. 4D flow MRI for non-invasive measurement of blood flow in the brain: A systematic review. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 41, 206–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271678X20952014 (2021).

Hwang, Z. A. et al. Intensity of arterial structure acquired by silent MRA estimates cerebral blood flow. Insights Imaging. 12, 185. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-021-01132-0 (2021).

Lee, S. H., Hur, K. S. H. N., Cho, Y. I. & Jeong, S. K. The effect of patient-specific non-newtonian blood viscosity on arterial hemodynamics predictions. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 19, 1940054 (2019).

Oelerich, M. et al. Intracranial vascular stenosis and occlusion: comparison of 3D time-of-flight and 3D phase-contrast MR angiography. Neuroradiology 40, 567–573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002340050645 (1998).

Murray, C. D. The physiological principle of minimum work: I. The vascular system and the cost of blood volume. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 12, 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.12.3.207 (1926).

R, S. S. & a., S. The history of poiseuille’s law. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 25, 1–19 (1993).

Zamir, M. Shear forces and blood vessel radii in the cardiovascular system. J. Gen. Physiol. 69, 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1085/jgp.69.4.449 (1977).

Cheng, C. et al. Large variations in absolute wall shear stress levels within one species and between species. Atherosclerosis 195, 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.11.019 (2007).

Reneman, R. S. & Hoeks, A. P. Wall shear stress as measured in vivo: consequences for the design of the arterial system. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 46, 499–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11517-008-0330-2 (2008).

Thompson, R. B. & McVeigh, E. R. Flow-gated phase-contrast MRI using radial acquisitions. Magn. Reson. Med. 52, 598–604. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.20187 (2004).

DL, K. S. & a., P. Time-of-flight angiography. In Magnetic Resonance Angiography: Principles and Applications (eds. James, C. C. & Timothy, J. C.) 39–50 (Springer, 2012).

Axel, L. Blood flow effects in magnetic resonance imaging. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 143, 1157–1166. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.143.6.1157 (1984).

Markl, M., Kilner, P. J. & Ebbers, T. Comprehensive 4D velocity mapping of the heart and great vessels by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 13, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429X-13-7 (2011).

Funding

This study was partially supported by a research grant from the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (RS-2023-00215667; JKH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.H. conducted the experiments and clinical studies and drafted the manuscript. S.H. participated in the experiment and data analysis and reviewed the draft. H.S. contributed to the experiments and reviewed the manuscript. R.R. was involved in the study design and manuscript review. S.K. planned the study, participated in the experiments and clinical study, and drafted the manuscript. K.H. contributed to the design, clinical study, and manuscript drafting and review. All authors critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, CH., Lee, S.H., Kwak, HS. et al. Arterial flow volume measurement using signal intensity gradient versus phase contrast. Sci Rep 15, 44848 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28379-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28379-7