Abstract

Quantum machine learning (QML) has emerged as a promising paradigm for solving complex classification problems by leveraging the computational advantages of quantum systems. While most traditional machine learning models focus on clean, balanced datasets, real-world data is often noisy, imbalanced and high-dimensional, posing significant challenges for scalability and generalisation. This paper conducts an extensive experimental evaluation of five supervised classifiers- Decision Tree, K nearest neighbour, Random Forest, linear regression and support vector machines in comparison with Quantum machine learning classifiers- quantum Support vector machine, quantum k- nearest neighbor and variational quantum classifier—across five diverse datasets, including iris, wine quality, Breast cancer, UCI human activity recognition, and Pima diabetes. To simulate real-world challenges, we introduce class imbalance using SMOTE and ADASYN Sampling, inject Gaussian noise into the features, and assess the impact of dimensionality reduction through ANOVA-based feature selection. Additionally, we utilise explainable AI tools, such as SHAP and LIME, to interpret model decisions. Our results demonstrate that Logistic Regression consistently performs well under various complexities, while Quantum Support Vector Machines show resilience to feature noise and class imbalance. The study also highlights the current capabilities and limitations of QML models, offering valuable insights into building generalisable and interpretable ML systems for deployment in complex environments. These insights are crucial for building robust, interpretable, and generalisable ML models for practical deployment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Machine Learning (ML) is employed in various computational domains to enhance performance and accuracy. However, the morphology of datasets used to learn the machine offers some obstacles in this task. Machine learning datasets typically consist of many tuples and a limited number of characteristics. Microarray technology, capable of exhibiting particular distinctions from conventional machine learning datasets, is deployed to overcome the morphological issues. To handle complex and vast varieties of datasets, various types of machine learning algorithms, viz. supervised, unsupervised or semi-supervised, are used. Supervised learning algorithms are the preferred machine learning approaches for classification and regression-related tasks. The Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), Neural Network (NN), Linear Regression, Decision Tree, & K-Nearest Neighbor are some extensively used supervised learning methods found in the literature1.

Machine Learning entails the development of a prediction algorithm based on past experiences, which necessitates obtaining relevant data in the specific field. Subsequently, the prediction network self-organizes based on the margin of error2 . In the present day, extracting important information from raw data for efficient decision-making is crucial in business, scientific, medicine, science and engineering applications. Modern intelligence technologies employ data analysis to examine and transform information into knowledge. Data Mining (DM) and Machine Learning (ML) are crucial in accurately extracting information from large datasets. Several machine-learning approaches are available for prediction, including classification, clustering, decision making and regression, as depicted in Fig. 1 below3.

Machine Learning enables systems to acquire knowledge from insight into datasets and improve their performance through natural learning processes without requiring explicit programming. Such algorithms are valuable in domains where it is impractical to implement explicitly written algorithms that can achieve high-speed performance4.

Classical Machine learning algorithms face limitations in scalability and computational efficiency, especially when the dataset size grows, resulting in growing complexity. And this is where we introduce Quantum machine learning, which leverages the principles of Quantum computing, such as superposition, entanglement, and quantum parallelism, to process information in fundamentally new ways. i.e., a Quantum Support Vector Machine (QSVM) can utilise quantum-enhanced feature maps and kernel estimation to classify data, potentially achieving speedups over classical SVMs, especially in high-dimensional feature spaces. Similarly, Quantum Decision Trees and Quantum Neural Networks (QNNs) explore non-classical representations and optimisations of classical models3.

The objective of quantum machine learning is to surpass the classical limits of problems such as pattern recognition, probabilistic mapping and optimisation. Although QML algorithms are currently in the early stages due to the limited availability of qubits and restrictions on quantum hardware, initial results show the potential of QML in the real world. Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of Quantum machine learning from classical machine learning.

The goal of the study is to assess the robustness and interpretability of both classical and quantum classifiers under realistic data challenges. The output of this research will be helpful in selecting a classifier that effectively evaluates previous data and makes accurate predictions for future decisions. This study makes the following key contributions:

-

Conducts a comprehensive empirical evaluation of five widely used supervised machine learning classifiers-Decision Tree, K-Nearest Neighbor, Random Forest, Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine and Quantum Machine Learning classifiers- quantum Support vector machine(QSVM), quantum k-nearest neighbor (QKNN) and variational quantum classifier (VQC ) across five publicly available datasets, reflecting varied real-world conditions.

-

Introduces class imbalance using both SMOTE and ADASYN and injects Gaussian noise into input features to simulate noisy high-dimensional environments commonly encountered in practical applications.

-

Applies ANOVA-based univariate feature selection to evaluate the effect of dimensionality reduction on model performance and to prepare inputs for quantum circuits.

-

Analyses the performance of all classifiers under varying conditions of data noise, imbalance, and feature sparsity using standard evaluation metrics.

-

Employs explainable AI methods, including SHAP and LIME, to interpret model decisions, and quantum kernel distribution, enhancing model transparency and trustworthiness, with extensions to quantum classifier interpretability.

-

Identifies logistic regression as a consistently high-performing model under noise and imbalance, while QSVM demonstrates resilience to noisy features; provides insights on the current capabilities of QML classifiers.

Section "Introduction" explains the concepts of supervised machine learning and Quantum machine learning. Sect. Related work presents an analysis of existing studies in the fields of machine learning and quantum computing. Section "Methodology" describes the methodology, followed by the results section, and Sect.conclusion concludes the paper.

Related work

Several researchers have conducted extensive studies on data analysis through Machine Learning (ML) and Quantum computing (QC) methodologies. Multiple studies have indicated the importance of these strategies in predicting future outcomes, particularly in the realm of classification problems. In these investigations, the authors utilised various methods to address specific issues and achieved high levels of accuracy in categorisation. For instance, these strategies are employed in the healthcare sector to predict diseases. Ch Anwar ul Hassan et al. evaluated the effectiveness of machine learning classifiers. Various ML classifiers, including LR, Naive Bayes, KNN and DT, were used to compare the accuracy, precision, and F-measure of the two datasets. The experimental results demonstrate that Random Forests outperform alternative classifiers. The model achieves an accuracy of 83% in heart data sets and 85% accuracy in predicting hepatitis illness5. Arslan Javaid et al. Proposed an innovative classification methodology and divided skin lesions into benign or malignant categories, employing image processing techniques with machine learning algorithms. Their work presented an innovative method for enhancing the contrast of thermoscope images and the OTSU thresholding technique utilised for picture segmentation. Subsequently, the feature vector undergoes standardisation and scaling. Before classification, a unique feature selection technique based on the wrapper method is proposed. The Random Forest method is the most successful and accurate classification algorithm for achieving maximum accuracy6. Vaishnavi Nath et al. created and implemented an innovative fraud detection technique to analyse streaming transaction data and study consumers’ past transaction information to identify their behavioural patterns. Cardholders are classified into separate categories based on their transaction amounts. Next, employing the sliding window approach, the exchanges performed by cards from several groups are combined to take out the respective behavioural patterns of each group. Subsequently, distinct classifiers are trained on each group individually7. Rabia Karakaya et al. examined the operational rationale of the method for recognising handwritten digits and evaluated the effectiveness of several methods on the identical database. A report was presented by doing a comparative analysis of the accuracy8. Piyush Vyas et al. proposed a hybrid approach, combining techniques based on lexicon for examining and labelling tweet sentiment with supervised machine learning approaches for classifying tweets and assessed the hybrid framework using numerous metrics for evaluation. The findings suggest that a significant proportion of the attitudes expressed are positive (38.5%) or neutral (34.7%)9. A summary of research in the field of quantum and classical machine learning is presented in Table 1.

Literature review gap

An in-depth analysis of the recent literature from 2023 to 2025 on machine learning and quantum machine learning applications across diverse datasets (e.g., RoEduNet-SIMARGL2021, CICIDS-2017, CWRU bearing, ShipsEar, MNIST, and others) reveals significant progress in terms of classification accuracy and the integration of explainable AI (XAI) and feature selection techniques. However, none of the reviewed studies have simultaneously addressed all three critical components: XAI integration, feature selection, and the inclusion of realistic quantum or classical noise models. This gap indicates a pressing need for a unified framework that can incorporate:

-

Explainable AI (XAI) for model interpretability,

-

Feature selection to reduce dimensionality and enhance performance, and

-

Noise models to simulate real-world deployment environments, particularly in quantum machine learning.

Addressing this triad holistically could significantly enhance the reliability, transparency, and deployment ability of both classical and quantum machine learning models.

Methodology

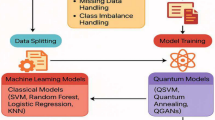

The goal of this section is to assess the performance and interpretability of five widely used classical ML algorithms -support vector machine, random forest, logistic regression, decision Tree and k nearest neighbor, along with three quantum ML algorithms- Quantum SVM, quantum kNN and variational Quantum Classifier, under various levels of complexity, i.e. noise handling, resampled data. Various steps of the methodology is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Key Python modules and libraries used include:

-

Scikit-learn: For data preprocessing, feature selection, classical model training, and performance evaluation.

-

Imbalanced-learn: Specifically, SMOTE and ADASYN were used to address class imbalance in the training data.

-

PennyLane: For constructing and simulating quantum circuits and implementing the Quantum ML Models.

-

SHAP and LIME: For model explainability and visualisation, aiding in the interpretation of feature contributions to model decisions.

-

Matplotlib and Seaborn: For plotting ROC curves and explanation visualisations.

-

NumPy and Pandas: For efficient numerical computation and data manipulation.

Each step is described in detail below.

Here is the pseudo-code for the methodology, for both the quantum and classical models:

Datasets

The different datasets have been selected to assess the performance of QML and ML classifiers. These datasets have been retrieved from the UCI and Kaggle repositories, as tabulated in Table 2. The term is used in the dataset to refer to several instances, features, classes, and their corresponding null values, if present.

Data preprocessing

Data preprocessing ensures the datasets are ready for model training and testing. The steps followed are:

Missing values

Missing values (if any) are imputed using the median (for numerical features) and mode (for categorical features).

Feature scaling

Standardization (z-score normalisation) is applied to all continuous variables to ensure uniformity.

Class imbalance simulation

SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique): Used for over-sampling the minority class in imbalanced datasets like Wine Quality, Breast Cancer, and Credit Card Fraud.

ADASYN (adaptive synthetic sampling): Applied over-sampling to the minority class in specific experiments, especially for highly imbalanced datasets. It generates synthetic samples adaptively, focusing more on minority class instances that are harder to learn, thereby improving classifiers’ performance.

Noise injection

Gaussian noise is added to the features to simulate sensor or data measurement errors. The noise level is controlled (e.g., adding 1% noise by randomly sampling from a Gaussian distribution).

where \(N\left( {0,\sigma^{2} } \right)\) Represents Gaussian noise with mean zero and standard deviation \({\varvec{\sigma}}\) .

Feature selection

SelectKBest: A univariate feature selection method based on ANOVA F-test scores is used to reduce the feature set and evaluate model performance under reduced dimensionality.

Dimensionality Reduction: The top k features (using SelectKBest) are selected to simulate a scenario with reduced information.

Supervised and quantum machine learning classifiers

Supervised learning in machine learning involves acquiring a function that establishes a relationship between input and output data, which can be achieved by utilising provided examples of input–output pairs. The procedure entails deriving a mathematical function based on training data labelled by assigning certain categories or classes and comprising a collection of training instances. The input dataset is partitioned into many training and testing datasets, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The training dataset includes a target variable that necessitates forecasting or categorisation. Algorithms extract patterns from the training dataset and employ them to make predictions or categorise the test dataset18.

Currently, Quantum ML has emerged as a promising advancement of classical ML by leveraging the principles of Quantum Computing to enhance the capacity of learning models. Quantum Models follow the same learning from labelled data but they encode the classical data to quantum data using feature maps and process it using quantum circuits. Figure 4 depicts the pipeline of machine learning.

Decision tree (DT)

Constructing a classifier involves utilising a set of internal and leaf nodes. The internal nodes represent decision criteria, while predictions are represented by the leaf nodes. Let \({^{\prime}}N{^{\prime}}\) Be the quantity of physiological characteristics and \({^{\prime}}M{^{\prime}}\) Represent the number of diagnosis predictions. Let \({^{\prime}}X{^{\prime}}\) Be a set of physiological characteristic vectors denoted \(as{ }\left\{ {X_{1} ,X_{2 \ldots \ldots \ldots } { }X_{N} } \right\}\) . Let \({^{\prime}}W{^{\prime}}\) Be the set of \({^{\prime}}N{^{\prime}}\) thresholds, denoted as {\(W_{1}\), \(W_{2 \ldots \ldots \ldots \ldots \ldots \ldots ..} W_{N}\). Consider \({^{\prime}}C{^{\prime}}\) as a set of diagnosis predictions, denoted as \(as{ }\left\{ {C_{1} ,C_{2 \ldots \ldots \ldots } { }C_{N} } \right\}\).. This process commences from the root node and proceeds towards the last node. Consequently, the classification effect depends on the choices from the starting node to the finishing node. The classification of a classifier based on decision trees can be understood as a collection of IF–THEN statements by systematically visiting each decision route. Hence, it is probable to transform a DT classifier in any rule base consisting of the collections of IF–THEN rules that are formed from the DT classifier19. The attribute that each node tests is labelled, and the values that correspond to those labels are labelled on its branches, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Support vector machine

SVM, a supervised classification method, begins with a pre-existing training set. During the training process, a Support Vector Machine (SVM) acquires knowledge regarding the correlation between each data point and its related label in the given training dataset8. It is specifically designed for binary classification of new testing vectors and refers to a type of issue characterised by having more equations than unknowns, which is known as an over-determined system of equations as represented in Fig. 6. The algorithm produces a hyperplane defined by the equation \(\to _{w} .\to _{x}\) + b = 0. This hyperplane ensures that to obtain a training point \(\to _{xn}\) in the positive class, \(\to _{w} .\to _{x}\) + b ≥ 1, and to obtain a training point \(\to _{{{\text{xn}}}}\) in the negative class, \(\to _{w} .\to _{x}\) + b ≤—1. The algorithm strives to optimise the distance between the two classes throughout the training process. This is logical since we wish to create a clear separation between the two classes in order to obtain a more accurate classification result for new data samples, such as \(\to _{{{\text{xo}}}}\). Mathematically, Support Vector Machines (SVM) find any hyperplane that maximises the distance between two parallel hyperplanes, subject to the restriction that the product of the predicted label ( \(\to _{{{\text{yi}}}}\)) and the linear combination of the weights (\(\to _{{\text{w}}}\)) and the input vector (\(\to _{{{\text{xo}}}}\))20. The diagram in Fig. 6 below represents the categorization of classes using a hyperplane.

K–Nearest Neighbor (KNN)

An enduring approach in class reasoning. The decision-making concept is based on a straightforward principle: the sample that needs to be evaluated is classified in the same category as the closest matching sample. The outcome of the Nearest Neighbor Rule is definitively established for all occurrences to be evaluated, assuming that the distance metric and training set remain constant. In set E, for every sample instance, if y is the closest neighboring instance to x, then the group of y is determined by the nearest neighbor rule. Assume X is a sample from an unidentified category. The decision process is envisaged in equation (2):

Subsequently, the outcome of the choice is \(X \varepsilon Wi.\)

In this context, the nearest neighbour rule is presented with a focus on two key aspects: convergence and generalisation error. The nearest neighbour for a given point \(x\), derived from two training sets with different samples, varies. Given that the classification outcome is contingent upon the category label of the closest neighbouring data point, \(P\left( {e|{ }x,x^{\prime } } \right)\), is so obtained. \(x\) and \(x\prime\) factors determine the conditional error rate21.

Random forest (RF)

This model is a collective learning technique. The algorithm constructs a series of decision trees throughout the training process and the mode determines the class that has the highest frequency among the trees for classification tasks, while it calculates the mean prediction for regression tasks. The node splitting criterion was configured to demand a minimum of two samples, and each leaf node must include at least one sample. The procedural instructions of the Random Forest algorithm:

-

Generate a bootstrap sample using the given data.

-

In order to create each bootstrap sample, a regression tree must be constructed with certain modifications: randomly select a subset of the predictors at each node and determine the optimal split among the variables.

-

Calculate the most recent data by summing up the forecasts of the \({n}_{t}\) trees (taking the average for regression).

Built on a random selection of observations, whether with or without replacement, approximately 36.8% are not utilized for any one tree. This means that these observations are considered "out of the bag (OOB)" for that specific tree. The predictive accuracy of a random forest can be assessed using the out-of-bag (OOB) data.

where the average forecast for the \({i}_{th}\) opinion from total trees the observation that is out-of-bag (OOB) is represented by \(\widehat{{y}_{i}}OOB\).

Linear regression (LR)

Regression is a method employed to analyze the association between two variables. The analysis is commonly employed for the purpose of forecasting and prediction, and it shares significant similarities with the field of machine learning. Crucially, this method demonstrates the relationships between a dependent variable and a predetermined set of other variables in a dataset. The equation is represented as \(y{ } = { }\beta 0{ } + { }\beta 1x{ } + { }\varepsilon .\) Simple regression separates the impact of independent factors from the interplay of dependent variables.

Quantum support vector machine

A Quantum Support Vector Machine (QSVM) is a quantum-enhanced version of the classical Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithm, designed to perform classification tasks. QSVM leverages quantum computing, particularly quantum kernel methods, to potentially outperform classical algorithms in certain scenarios, especially when dealing with high-dimensional data or complex patterns that are difficult to capture classically.

Quantum SVM replaces the classical kernel function with a quantum kernel, which is computed by a quantum computer. This quantum kernel is based on the inner product of quantum states, which allows encoding classical data into quantum feature space.

Quantum kernel estimation

The key idea is to map a classical data point xxx to a quantum state \(\left| {\left. {\phi \left( x \right)} \right\rangle } \right|\) and then compute a kernel matrix \(K\left( {x,x^{\prime } } \right) = \left| {\left\langle {\phi \left( x \right)} \right.} \right|\left. {\left. {\phi \left( {x^{\prime } } \right)} \right\rangle } \right|^{2}\) This is usually done by:

Encoding data into quantum circuits using a feature map \(U\phi \left( x \right)\).

Measuring the fidelity (overlap) between quantum states

This allows capturing nonlinear patterns efficiently, potentially with exponential speedups.

Workflow of QSVM

Feature mapping: Encode classical data xxx into a quantum state using a parameterized unitary \(U\phi \left( x \right)\).

Kernel evaluation: Compute \(K\left( {x,x^{\prime } } \right) = \left| {\left\langle {\phi \left( x \right)} \right.} \right|\left. {\left. {\phi \left( {x^{\prime } } \right)} \right\rangle } \right|^{2}\).

Classical SVM Solver: Use a classical algorithm (e.g., LIBSVM) to find the separating hyperplane using the quantum kernel matrix

Prediction: New data points are mapped and evaluated using the quantum kernel.

Quantum k nearest neighbor

The Quantum kNN algorithm adapts the classical k nearest neighbor classifier to a quantum computing paradigm by representing classical vectors as quantum states and using quantum subroutine to estimate inter sample similarities in superposition. QkNN aims to accelerate distance or similarity estimation and nearest neighbor search under theoretical models that provide efficient quantum access to data22.

QkNN implementations usually estimate \(s\left( {x_{q} ,x_{i} } \right)\) using one of the:

-

Fidelity / inner product: \(\left| {\left\langle {x_{q} } \right.} \right|\left. {\left. {x_{i} } \right\rangle } \right|^{2}\), estimated via a SWAP test or Hadamard test.

-

Euclidean distance via inner product identity:

-

\(\parallel x_{q} - x_{i} \parallel^{2} = \parallel x_{q} \parallel^{2} + \parallel x_{i} \parallel^{2} - 2\left\langle {x_{q} ,x_{i} } \right\rangle\) where the inner product is obtained from amplitude overlaps.

-

Hamming or other discrete distances when features are binarised; specialised circuits exist for parallel Hamming distance estimation.

Variational quantum classifier

The Quantum Variational Classifier (VQC) is a hybrid quantum–classical supervised learning model that leverages parameterised quantum circuits (PQCs) optimised via classical algorithms. It belongs to the class of Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs), specifically designed for Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices.VQC combine quantum feature encoding and trainable quantum layers to learn complex, nonlinear decision boundaries, analogous to a neural network but implemented on qubits. Their advantage lies in exploiting quantum entanglement and superposition to represent data in exponentially large Hilbert spaces, offering potential expressivity beyond classical models23 . If given a dataset D, then

the goal is to find a variational quantum circuit \(U\left( \theta \right)\) parameterised by a vector of tunable parameters \(\theta\) such that the measurement expectation value corresponds to the predicted class label.

This process these steps are included :

-

Encoding: map classical data \(x_{i}\) into a quantum state \(\left| {x_{i} } \right\rangle = U_{\phi } \left( {x_{i} } \right)\left| 0 \right\rangle^{ \otimes n}\), where \(U_{\phi }\) is a data-dependent unitary transformation.

-

Parameterised evolution: Apply a trainable unitary \(U\left( \theta \right)\) to form \(\left| {\psi \left( {x_{i} ,\theta } \right)} \right\rangle = U\left( \theta \right)U_{\phi } \left( {x_{i} } \right)\left| 0 \right\rangle^{ \otimes n}\)

Measurement: Measure an observable (e.g., Pauli-Z) to obtain the expectation value:

where \(M\) is the measurement operator. The sign of \({f}_{\theta }({x}_{i})\) determines the class label.

-

Optimisation: Minimise a cost function such as binary cross-entropy or hinge loss24:

$$L\left( \theta \right) = \frac{1}{N}\mathop \sum \limits_{i} \ell \left( {f_{\theta } \left( {x_{i} } \right),y_{i} } \right)$$(5)

Evaluation parameters

Within the domain of data mining, several evaluation measures, including accuracy, F-measure, precision, and recall, are commonly employed to assess the system’s performance. In this paper, we will consider these measures to evaluate performance. TPe is an abbreviation for correctly identified positive, FPe is a false positive, TNe is a true negative, and FNe is a false negative.

The accuracy rate is the ratio of instances with correct classification to the total cases tried, as stated in Eq. (1). The equation can be formulated in the following manner:

The precision of a model is defined as the proportion of the truly positive instances that are correctly forecasted to all positive forecasts generated by the model.

The recall calculates the percentage of positive scenarios correctly predicted to the total number of positive scenarios, with the false negative scenarios, and is occasionally called the true positive rate.

The F1 score is a quantitative measure that assesses the relationship between precision and recall. The calculation involves taking the harmonious average of both. It is a valuable metric for achieving a compromise between high precision and strong recall. It effectively penalises extreme negative values of either component.

Accuracy quantifies the overall correctness or precision of a measurement or calculation. In the equation \(Pr1\) stands for precision \(Re1\) stands for recall

ROC curve: The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve is a standard tool for evaluating binary classifiers, especially in imbalanced medical datasets. It illustrates the trade-off between a True Positive Rate (Sensitivity) and a False Positive Rate (1—Specificity).

Confusion matrix: It is a tabular representation of showing the counts of True positives, true negatives, false positives and false negatives.

Explainability: SHAP, LIME and Quantum kernel distribution

To enhance model transparency, we use two popular Explainable AI (XAI) techniques: SHAP and LIME. These techniques provide insights into which features are driving the model’s predictions.

SHAP

We use SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to evaluate feature importance globally. SHAP values indicate the impact of each feature on the prediction for each instance.

LIME

For local interpretability, we use LIME to explain individual predictions by approximating the model with simpler interpretable models around each prediction.

Quantum kernel distribution

To analyse quantum-enhanced models like QSVM and QKNN, we examine the distribution of quantum kernel values. The quantum kernel distribution provides insights into how well different classes are separable in the high-dimensional feature space, highlighting regions where the quantum embedding improves classification performance.

Hardware availability and simulation justification

All quantum modes in the study are implemented and executed using the pennylane framework on Google Colab, leveraging its high-performance cloud runtime for reproducible quantum simulation. This design choice was guided by the limited public availability of current NISQ devices, where hardware execution remains constrained by qubit decoherence and hardware noise and is not publicly available or available at a very high cost. Running on Google Colab ensures platform independence and reproducibility across multiple runs. The implemented circuits are intentionally designed with shallow depth and fewer qubit requirements. Consequently, the reported results represent a reproducible and hardware-ready baseline for future near-term deployment.

Experimental results and analysis

Supervised and Quantum Machine Learning classification acquires knowledge from data that is not evaluated based on its performance; eighty per cent of the dataset was designated for training. while the remaining 20% of the dataset is designated as the testing set. The model’s performance is assessed on unseen testing sets, where the model learns from the data without adjusting and optimizing the parameters.

Parameter tuning

Table 3 summarizes key experimental settings, covering dataset handling, preprocessing, model configurations, and evaluation strategies. Each component-from feature selection and resampling to classical and quantum classifiers-was tuned or applied with specific parameters to ensure fair, reproducible, and interpretable results.

Performance overview of classical ML models

To evaluate the performance and robustness of classical machine learning models under varying data conditions, we conducted experiments on five benchmark datasets: Breast Cancer Wisconsin, Iris, Wine Quality, Pima, HAR human activity Dataset. Each dataset was subjected to four experimental variants: (1) resampled data using SMOTE (2) ADASYN (3) noisy data with Gaussian noise, and (4) selected features using ANOVA F-test. Performance was assessed via accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, confusion matrix and Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC). The results are reported for both original and resampled datasets using SMOTE to address class imbalance. Tables 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 summarize the classification performance across all datasets and models. For clarity and reproducibility, each table is grouped by ML Models and includes all four data preprocessing variants.

Performance overview of quantum ML models

To assess the effectiveness of quantum machine learning algorithms, we evaluated three quantum models- Quantum SVM, Quantum kNN, and VQC- on the same dataset applied to classical models. Each dataset was preprocessed using feature standardisation, Gaussian noise addition, and synthetic oversampling (SMOTE and ADASYN). Tables 9, 10 and 11 summarizes the results, highlighting the impact of quantum feature mapping, kernel distributions, and entanglement depth on classification performance. Each tables from 9, 10 and 11 includes metrics averaged over multiple runs, along with standard deviations, to ensure robustness.

Visual analysis and model explainability

To support transparency and interpretability, we applied SHAP (Shapley Additive explanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) techniques on selected models trained on the provided datasets. SHAP summary plots revealed that features such as mean radius and worst concavity were dominant predictors in the breast cancer classification task. LIME explanations illustrated local decision boundaries for SVM and LR classifiers, validating the importance of top-ranked features and offering insight into individual prediction justifications.

From Figs. 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11, we can see SHAP helped identify which features were most important globally, confirming the model relies on medically significant indicators like mean radius and worst concavity. Meanwhile, LIME provided local explanations for individual predictions, demonstrating how specific feature values influence the classification of benign or malignant. Together, these tools enhance trust in the model by offering global and local interpretability. he SHAP plots typically showed red dots indicating higher feature values., Blue dots indicate lower values and. Horizontal clustering near zero indicated low interaction or low impact while the LIME plot breaks down the prediction into positive (supportive) and negative (opposing) contributions, blue bars push the prediction toward one class (e.g., benign, no disease), and orange bars push it toward the opposite class (e.g., malignant, disease present). We also analyse the quantum kernel distributions. Quantum kernels encode classical data into a high-dimensional Hilbert space, enhancing the separability of complex patterns. The kernel distribution, computed as the squared overlap of quantum states, reveals how well the feature map differentiates between classes: tightly clustered intra-class distributions and well-separated inter-class distributions indicate effective encoding. This analysis offers insights into the discriminative power of various quantum feature maps, guiding the selection of kernels and circuit architectures for optimal quantum-enhanced classification. Quantum kernel distributions for all datasets are illustrated in Fig. 12a–e.

The histogram in Fig. 12 shows the distribution of quantum kernel values for all five benchmark datasets used in the study. Each subplot illustrates the frequency of pairwise kernel similarities obtained after encoding the data using the selected quantum feature map. The distribution highlights how the quantum feature map transforms each dataset into the quantum Hilbert space, revealing differences in quantum concentration spread and separability across datasets.

ROC curve and confusion matrix analysis

Accuracy alone can be misleading, especially in imbalanced datasets (e.g., disease detection). ROC curves provide a threshold-independent performance metric that evaluates the classifier’s ability to separate positive and negative classes across all possible thresholds. We analysed the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and Confusion metrix for all models against all datasets, and it is not feasible to present the ROC curve for all cases, so the best ones are presented in Figs. 13, 14, 15, 16 and 17.

Summary of best performing configuration – analysis and interpretation

Table 12 below consolidates the optimal configuration, model type, and data preprocessing technique that yielded the highest classification performance on each of the five datasets, as measured by both Accuracy and execution time.

The bar chart in Fig. 18 illustrates the performance of the best models for each dataset based on accuracy and execution time. The Logistic Regression achieved a perfect score on the iris, UCI-HAR, and Pima dataset, while QSVM performed strongly on the Breast Cancer, and Random Forest did a tremendous job for wine dataset. The Pima diabetes dataset presented more challenges, with a noticeable drop in the accuracies.

The comparative analysis across multiple benchmark datasets demonstrates a distinct performance pattern between quantum and classical machine learning models. QSVM got a remarkable accuracy (98.7%) when using with the Breast cancer dataset(SMOTE + Noise ON), representing the robustness and capacity of QML to model high-dimensional feature space, but this performance was achieved at significantly higher computational overhead, i.e. 147.59 s, which reflects the simulation capacity of quantum circuits. When evaluating the wine dataset, Random Forest achieved the highest accuracy, 99.7%, illustrating its computational efficiency and superior performance on structured data.

For iris, PIMA and UCI-HAR datasets, Logistic regression consistently performed well with the accuracies of 98.87, 96.00 and 77.5%. With the minimum execution time, it suggests the reliability and computational efficiency for complex problems. With the incorporation of SMOTE and ADASYN, it effectively mitigated the class imbalance and enhanced the classification performance.

These findings reveal a clear tradeoff between predictive performance and computational efficiency, highlighting the importance of selecting the right classifier with appropriate methods of preprocessing, i.e., resampling and noise handling, to maximise performance across different domains.To benchmark the results, the study’s findings are now compared with existing results in Table 13.

.

The comparison of classification accuracies of existing models reported in the literature with our results is presented in Table 13. For the iris, wine, and Breast cancer datasets, the study’s results are significantly better than those of existing studies. However, the results of the study are not so good for the PIMA dataset, but still comparable. There is a lack of work on QkNN with PIMA, UCI HAR, and VQC on UCI HAR datasets, so we fill this gap by including them in our study. The results of Table 13 are shown in Fig. 19 in graphical form.

Insights from the results

The valuable insights of the experiment are presented in Table 14. From the table, it can be reasonably inferred that the classical models delivered fast and consistent results, while the quantum models, particularly QSVM, help capture complex patterns. QkNN can be a reliable option where fast execution time is required. And VQC is very prone to noise with lower stability.

Application relevance and real world impact

The comparative framework developed in this study holds strong relevance for real-world domains characterised by data imbalance, noisy features, and complex non-linear separability. Applications such as fraud detection, medical diagnosis, and industrial IoT anomaly detection often exhibit these challenges, where small but critical minority classes are easily overshadowed by dominant patterns. The demonstrated performance of quantum classifiers, particularly QSVM and VQC, on imbalanced and noisy datasets highlights their potential to enhance decision-making in such high-stakes environments. Quantum feature maps effectively embed overlapping classical data into higher-dimensional Hilbert spaces, allowing improved class separability even with limited training samples. Consequently, the proposed framework establishes a foundation for quantum-enhanced analytics that can be extended to practical sectors once stable and accessible quantum hardware becomes available.

Conclusion and future work

A detailed comparative analysis of classical and quantum machine learning is presented in this study, including five datasets, a range of data preprocessing techniques, i.e. resampling, noise handling and feature selection. The results of the experiment suggested that the performance of ML Models is susceptible to the selection of the preprocessing technique and the type of classifier.

Logistic regression in classical ML Models showcased its performance with the highest accuracy in the Iris, Pima, and UCI-HAR datasets. Similarly, Random Forest achieved the highest accuracy with wine datasets, both with and without noise, demonstrating its potential to remain consistent in all cases.

The quantum-enhanced ML Model QSVM outperforms all other classical and quantum models when implemented using the breast cancer dataset, achieving an accuracy of almost 99%, albeit with the highest execution time, highlighting the limited availability of quantum simulations.

Interpretability tools, such as SHAP and LIME, further validated the trustworthiness of the models by identifying both globally and locally essential features, particularly in medical and activity recognition datasets. Confusion matrix, ROC curve, and analyses complemented traditional metrics, especially under class imbalance, highlighting the robust behaviour of the classifier across decision thresholds. Quantum kernel distribution is also analysed to show the similarity values between data points.

When benchmarked against existing literature, the proposed models not only achieved competitive accuracies but also did so using simpler and more interpretable techniques. This suggests that optimal performance does not necessarily require complex architectures; instead, it benefits from judicious model selection, balanced datasets, and effective preprocessing.

In conclusion, this work reinforces the value of hybrid pipelines, which merge classical robustness with emerging quantum techniques, while promoting transparency through explainability tools. These insights can inform the development of future quantum–classical models for real-world classification tasks across healthcare, sensor data, and beyond. Future work will include deploying the optimised quantum circuits on real quantum backends such as IBMQ and ionQ Aria, subject to public availability. This will enable empirical validation of noise resilience and circuit fidelity in a hardware-constrained environment.

Data availability

All the datasets are publicly available at UCI and Kaggle - Breast Cancer Wisconsin Dataset - [https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/17/breast+cancer+wisconsin+diagnostic](https:/archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/17/breast+cancer+wisconsin+diagnostic) , Iris Dataset- [https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/53/iris](https:/archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/53/iris) , Wine Dataset- [https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/109/wine](https:/archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/109/wine) , Pima indian diabetes dataset- [https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/uciml/pima-indians-diabetes-database](https:/www.kaggle.com/datasets/uciml/pima-indians-diabetes-database) , UCI human activity recognition dataset- [https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/240/human+activity+recognition+using+smartphones](https:/archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/240/human+activity+recognition+using+smartphones)

References

Mohsin Abdulazeez, A., Zeebaree, D. Q., Abdulqader, D. M. & Zeebaree, D. Q. Machine learning supervised algorithms of gene selection: A review. Researchgate. Net 62(03), 233–244 (2020).

Singh, A. & Bist, A. S. A wide scale survey on handwritten character recognition using machine learning. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Eng. 7(6), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.26438/ijcse/v7i6.124134 (2019).

C. Havenstein, D. Thomas, S. Chandrasekaran, C. L. Havenstein, and D. T. Thomas, “Comparisons of Performance between Quantum and Classical Machine Learning,” SMU Data Science Review, vol. 1, no. 4, p. 11, 2018, [Online]. Available: https://scholar.smu.edu/datasciencereviewhttp://digitalrepository.smu.edu.Availableat:https://scholar.smu.edu/datasciencereview/vol1/iss4/11

H. K. Gianey and R. Choudhary, “Comprehensive Review On Supervised Machine Learning Algorithms,” Proceedings - 2017 International Conference on Machine Learning and Data Science, MLDS 2017, vol. 2018-Janua, pp. 38–43, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1109/MLDS.2017.11.

C. A. Ul Hassan, M. S. Khan, and M. A. Shah, “Comparison of machine learning algorithms in data classification,” ICAC 2018 - 2018 24th IEEE International Conference on Automation and Computing: Improving Productivity through Automation and Computing, no. pp. 1–6, 2018, https://doi.org/10.23919/IConAC.2018.8748995.

A. Javaid, M. Sadiq, and F. Akram, Skin Cancer Classification Using Image Processing and Machine Learning, Proceedings of 18th International Bhurban Conference on Applied Sciences and Technologies, IBCAST 2021, pp. 439–444, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1109/IBCAST51254.2021.9393198.

Dornadula, V. N. & Geetha, S. Credit card fraud detection using machine learning algorithms. Procedia Comput. Sci. 165, 631–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2020.01.057 (2019).

Karakaya, R. & Kazan, S. handwritten digit recognition using machine learning. Sakarya Univ. J. Sci. 25(1), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.16984/saufenbilder.801684 (2021).

P. Vyas, M. R. Fellow, B. P. Rimal, S. Member, and G. Vyas, “Automated Classification of Societal Sentiments on Twitter with Machine Learning,” pp. 1–11.

O. Arreche, T. Guntur, and M. Abdallah, “XAI-based Feature Selection for Improved Network Intrusion Detection Systems,” 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2410.10050. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2410.10050.

“Machine Fault Diagnosis Using Audio Sensors Data and Explainable AI Techniques-LIME and SHAP.” [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Aniqua-Zereen-2/publication/383320912_Machine_Fault_Diagnosis_Using_Audio_Sensors_Data_and_Explainable_AI_Techniques-LIME_and_SHAP/links/66da9385fa5e11512ca21e81/Machine-Fault-Diagnosis-Using-Audio-Sensors-Data-and-Explainable-AI-Techniques-LIME-and-SHAP.pdf

Shojaeinasab, A., Jalayer, M., Baniasadi, A. & Najjaran, H. Unveiling the black box: A unified XAI framework for signal-based deep learning models. Machines 12(2), 121. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines12020121 (2024).

Liu, C., Han, D., Zhang, X. & Li, N. Research on feature extraction of underwater acoustic target radiation noise based on machine learning algorithm. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2644(1), 012008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/2644/1/012008 (2023).

Franco, G.S., Mahlow, F., Prado, P.M., Pexe, G.E., Rattighieri, L.A. and Fanchini, F.F. Quantum Phases Classification Using Quantum Machine Learning with SHAP-Driven Feature Selection,” (2025), arXiv: arXiv:2504.10673. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2504.10673.

Kottahachchi-Kankanamge-Don, A. and Khalil, I. 2025 QRLaXAI: quantum representation learning and explainable AI,” Quantum Mach. Intell., https://doi.org/10.1007/s42484-025-00253-9.

Mücke, S., Heese, R., Müller, S., Wolter, M. & Piatkowski, N. Feature selection on quantum computers. Quantum Mach. Intell. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42484-023-00099-z (2023).

G. Hellstern, V. Dehn, and M. Zaefferer, Quantum computer based Feature Selection in Machine Learning, 2023. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2306.10591

Mahesh, B. Machine learning algorithms—A review|enhanced reader. Int. J. Sci. Res. 9(1), 381–386. https://doi.org/10.21275/ART20203995 (2020).

Liang, J., Qin, Z., Xiao, S., Ou, L. & Lin, X. Efficient and secure decision tree classification for cloud-assisted online diagnosis services. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secure Comput. 18(4), 1632–1644. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDSC.2019.2922958 (2021).

A. Kariya and B. K. Behera, “Investigation of Quantum Support Vector Machine for Classification in NISQ era,” pp. 1–15, 2021.

Xing, W. & Bei, Y. Medical health big data classification based on KNN classification algorithm. IEEE Access 8, 28808–28819. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2955754 (2020).

Dang, Y., Jiang, N., Hu, H., Ji, Z. & Zhang, W. Image classification based on quantum K-Nearest-Neighbor algorithm. Quantum Inf. Process. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11128-018-2004-9 (2018).

Maheshwari, D., Sierra-Sosa, D. & Garcia-Zapirain, B. Variational quantum classifier for binary classification: Real vs synthetic dataset. IEEE Access 10, 3705–3715. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3139323 (2022).

Maragkopoulos, G., Mandilara, A., Tsili, A. & Syvridis, D. Enhancing the performance of variational quantum classifiers with hybrid autoencoders. Quantum Inf. Process 24(8), 244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11128-025-04864-w (2025).

Hussain, Z. F. et al. A new model for iris data set classification based on linear support vector machine parameter’s optimization. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 10(1), 1079–1084. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijece.v10i1.pp1079-1084 (2020).

Aziz, C. F. & Awrahman, B. J. Prediction model based on iris dataset via some machine learning algorithms. J. Kufa Math. Comput. 10(2), 64–69. https://doi.org/10.31642/jokmc/2018/100210 (2023).

Pandey, A. & Jain, A. Comparative analysis of KNN algorithm using various normalization techniques. Int. J. Comput. Netw. Inf. Secur. 9(11), 36–42. https://doi.org/10.5815/ijcnis.2017.11.04 (2017).

Zhou, Y. Study for iris classification based on multiple machine learning models. HSET 23, 342–349. https://doi.org/10.54097/hset.v23i.3620 (2022).

Y. Fakir, Y. Lakhdoura, and R. Elayachi, Comparative Analysis of Random Forest and J48 Classifiers for ‘IRIS’ Variety Prediction, 2020.

J. Yi, K. Suresh, A. Moghiseh, and N. Wehn, Variational Quantum Linear Solver enhanced Quantum Support Vector Machine 2023, arXiv: arXiv:2309.07770. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2309.07770.

Guerrero-Estrada, A.-Y., Quezada, L. F. & Sun, G.-H. Benchmarking quantum versions of the kNN algorithm with a metric based on amplitude-encoded features. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 16697. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67392-0 (2024).

Akrom, M., Herowati, W. & Setiadi, D. R. I. M. A quantum circuit learning-based investigation: A case study in iris benchmark dataset binary classification. J. Comput. Theor. Appl. 2(3), 355–367. https://doi.org/10.62411/jcta.11779 (2025).

Ahammed, B. & Abedin, M. M. Predicting wine types with different classification techniques. Model. Assist. Stat. Appl. 13(1), 85–93. https://doi.org/10.3233/MAS-170420 (2018).

Dhaliwal, P., Sharma, S. & Chauhan, L. Detailed study of wine dataset and its optimization. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. 14(5), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.5815/ijisa.2022.05.04 (2022).

R. Chandra, Comparison of Data Normalization for Wine Classification Using K-NN Algorithm, IJIIS: International Journal of Informatics and Information Systems, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 175–180, 2022, https://doi.org/10.47738/ijiis.v5i4.145.

A. Trivedi and R. Sehrawat, Wine Quality Detection through Machine Learning Algorithms,” In 2018 International Conference on Recent Innovations in Electrical, Electronics & Communication Engineering (ICRIEECE), Bhubaneswar, India: IEEE, 2018, 1756–1760. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRIEECE44171.2018.9009111.

A. Shah, M. Shah, and P. Kanani, Leveraging Quantum Computing for Supervised Classification, In 2020 4th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS), Madurai, India: IEEE, 2020 256–261. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICICCS48265.2020.9120975.

Kölle, M., Giovagnoli, A., Stein, J., Mansky, M.B., Hager, J. and Linnhoff-Popien, C. Improving convergence for quantum variational classifiers using weight re-mapping, (2023) https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2212.14807.

Vig, L. Comparative analysis of different classifiers for the Wisconsin breast cancer dataset. OALib 01(06), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1100660 (2014).

Hossin, M. M. et al. Breast cancer detection: an effective comparison of different machine learning algorithms on the Wisconsin dataset. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inf. 12(4), 2446–2456. https://doi.org/10.11591/eei.v12i4.4448 (2023).

Assegie, T. A. An optimized K-nearest neighbor based breast cancer detection. JRC https://doi.org/10.18196/jrc.2363 (2021).

Murugan, S., Kumar, B.M. and Amudha, S. Classification and Prediction of Breast Cancer using Linear Regression, Decision Tree and Random Forest,” In 2017 International Conference on Current Trends in Computer, Electrical, Electronics and Communication (CTCEEC), Mysore: IEEE, 2017 763–766. https://doi.org/10.1109/CTCEEC.2017.8455058.

Ronggon AA, Rahman MS. Performance Analysis and Noise Impact of a Novel Quantum KNN Algorithm for Machine Learning 2025 arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2505.06441.

Desai, U., Kola, K.S., Nikhitha, S., Nithin, G., Raj, G.P. and Karthik, G. Comparison of Machine Learning and Quantum Machine Learning for Breast Cancer Detection,” In 2024 International Conference on Smart Systems for applications in Electrical Sciences (ICSSES), Tumakuru, India: IEEE, 2024, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSSES62373.2024.10561257.

Zargar, O.S., Bhagat, A., Teli, T.A. and Sheikh, S. Early Prediction Of Diabetes Mellitus On Pima Dataset Using Ml And Dl Techniques, vol. 23, no. 1, (2023).

Tudisco, A., Volpe, D. and Turvani, G. Multi-VQC: A Novel QML Approach for Enhancing Healthcare Classification, In 2025 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Software (QSW), (2025), 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1109/QSW67625.2025.00013.

Shdefat, A. Y., Mostafa, N., Al-Arnaout, Z., Kotb, Y. & Alabed, S. Optimizing HAR systems: Comparative analysis of enhanced SVM and k-NN classifiers. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 17(1), 150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44196-024-00554-0 (2024).

Nayak, S., Panigrahi, C., Pati, B., Nanda, S. & Hsieh, M.-Y. Comparative analysis of HAR datasets using classification algorithms. ComSIS 19(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.2298/CSIS201221043N (2022).

P. Agarwal and M. Alam, “Quantum-Inspired Support Vector Machines for Human Activity Recognition in Industry 4.0,” In Proceedings of Data Analytics and Management, vol. 90, D. Gupta, Z. Polkowski, A. Khanna, S. Bhattacharyya, and O. Castillo, Eds., In Lecture Notes on Data Engineering and Communications Technologies, vol. 90. , Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2022, pp. 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-6289-8_24.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to every aspect of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheoran, S.K., Yadav, V. & Sheoran, R.K. Robust evaluation of classical and quantum machine learning under noise, imbalance, feature reduction and explainability. Sci Rep 15, 45714 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28412-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28412-9