Abstract

Bee pollen as a natural product has gained popularity in recent years and is increasingly being used as a food and dietary supplement. This work aims to characterize, the botanical origin, nutritional value, total phenolic content, and microbiological quality of this beehive product. Palynological analyses of 28 pollen samples by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) identified a total of 75 pollen types from 25 families and 64 genera, most of them belonging to Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Rosaceae, Brassicaceae and Apiaceae families. Physicochemical parameters were determined, and data showed that pH, moisture, and ash content values ranged from 4.7 to 5.4, 2.1% to 3.2%, and 1.8% to 2.1%, respectively. Total carbohydrate, lipid, and protein contents in these samples varied from 67.7% to 75.8%, 2.1% to 8.9%, and 16.4% to 24.6%, respectively. Total phenolic content was between 6 and 11.5 mg GAE/g pollen. Microbiological quality was assessed using the plate count method, and the aerobic mesophilic plate count (APC) of pollen samples ranged from 1.2 × 102 to 6 × 103 cfu/g. The results of this study could play an important role in the quality control of bee pollen, and help improve the commercial value of this product.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pollen is the male reproductive cell of seed plants. Bee pollen is a product resulting from the agglutination of pollen with nectar and salivary substances of the honey bee (Apis mellifera L.). Bee workers collect pollen from flowers, combine it with their oral secretions and form the blend into pellets, and then transport it to the hive on their hind pair of legs1,2,3. Pollen is basically the main nutritional source for bees. This product will be used for feeding, especially of the larvae. It is essential to the normal growth and development of all individuals, and for the reproduction and maintenance of the colony4,5,6,7. Additionally, the collection of pollen by bees plays an ecologically fundamental role in pollination and in the conservation of plant biodiversity8,9. Beekeepers harvest bee pollen by placing traps at the hive entrances; then they cleaning and dry it to prepare it for human consumption1,10. Bee pollen contains carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and vitamins2,11,12,13,14,15. Many minerals such as K, P, Mg, Ca, Na, S, Fe, Cu, Mn, Zn, Ch, and Se have also been detected in bee pollen samples16,17,18. Moreover, studies have found that bee pollen contains polyphenol groups such as quercetin, myricetin, rutin, tricetin, luteolin, selagin, and isorhamnetin3,19,20,21. Bee pollen may be used as a dietary supplement due to its high nutritional value and therapeutic properties, i.e., its anti- inflammatory22,23,24,25,26, antioxidant27,28,29,30, antimicrobial31,32,33,34,35, antifungal8,36,37 and anticancer38,39,40 activities. It has been described as being anti-anemic and as a tonic and restorative, hormone regulator, intestinal regulator, vasoprotector, hepatoprotective, and anti-atheroscleorotic agent12,27,41,42. Bee pollen has also been successfully used to treat some cases of benign prostatitis and for the oral desensitization of children who have allergies43,44. Its therapeutic properties have been attributed mainly to the presence of flavonoids, phenolic acids, and hydroxycinnamic acid amides2,41,45,46. Composition and characteristic features such as color, size, and aroma of the bee pollen depend on its botanical and geographical origin together with other factors, such as climatic conditions, time of year, and beekeeper activities2,21,47,48,49,50,51,52. When bees visit predominantly single plant species, the collected bee pollen is called monofloral and reflects the biochemical, functional, and sensory properties of the original plant, and exhibits a uniform color. Monofloral bee pollen should be represented with more than 80% of the pollen grains of the related taxon. Conversely, multifloral bee pollen is collected by bees from various plants and possesses a variety of properties, and displays a mixture of colors1,53. The diversity and frequency of pollen grains in bee pollen can be determined by palynological analysis, which indicates the botanical and geographical origin of the product. Determining the botanical and geographical origin of bee pollen is important for quality control and increases the commercial value of bee products41,52. Palynological analysis seems to be essential, especially when specific therapeutic properties are associated with a botanical species. For example, several studies have shown that Cistus bee pollen can stimulate the bone system in an animal model and has anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antioxidant effects as well54,55,56. Palynology is an important tool for identifying the floral resources preferentially used by bees57. Knowing the bee flora is an important step towards the rational exploitation and conservation of bees, contributing to apiary management. Palynology can also reveal changes in regional vegetation and biodiversity such as, for example, non-native and exotic plant invasions, and thus contribute to the ecological and conservation studies of plant diversity2,6,58,59. Moreover, determining the physico-chemical properties, nutritional composition, and quantification of bioactive markers such as phenolic compounds is necessary for the standardization of the bee pollen. It is known that bee health is influenced by many parameters of the nutritional quality of a pollen diet, such as protein content, digestibility, amino-acid profile, lipids, vitamins and minerals60. As bees and their products are considered effective biological monitoring tools, the results of nutritional and physico-chemical analysis can reflect the state of the environment that affects the health and wellbeing of both humans and bees61. They can be used by beekeepers to identify the most advantageous locations for the collection of bee pollen.

Iran is one of the main centers of diversity for flowering plants in the world with almost 8000 plant species62,63,64. This high flora diversity along with favorable climatic conditions in several Iranian regions make the country suitable for beekeeping. Apiculture is an important economic activity in Iran. Despite a growing interest in beekeeping, apicultural authorities are focused on honey production, and they neglect other hive products such as royal jelly, propolis, and bee pollen. To date, no scientific study concerning the national bee pollen in Iran has been conducted. Moreover, the status of the production as well as the trade of bee pollen in Iran is unclear. Therefore, the comprehensive and detailed characterization of Iranian bee pollen is an important research priority so as to obtain reliable data on this valuable product. In addition, the investigation of its chemical, nutritional and microbiological composition and a botanical certification program will contribute to valorizing this natural product and increasing its commercial value.

The aim of this study was to determine the botanical origin, nutritional composition, and microbial quality of multifloral bee pollen samples from Iran. We used palynological analysis to identify the botanical origin of different bee pollen samples and determined values for the nutritional and phytochemical parameters of moisture, ash, pH, lipid, carbohydrate, protein, energy, and polyphenol contents. Finally, microbial quality was evaluated by colony counting the aerobic mesophilic micro-organisms of the pollen samples. As far as we know, this is the first study of bee pollen in Iran, and its results might help improve the certification of this product and increase its economic benefit.

Materials and methods

Study area

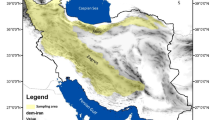

The study was conducted in Azerbaijan province (also known as Iranian Azerbaijan), northwestern Iran, which is divided into East Azerbaijan and West Azerbaijan (Fig. 1). This province is located between 35° and 39° N latitude and between 44° and 48° E longitude. Azerbaijan province measures 82,540 km2 and covers about 5.1% of Iran՚s total area. It shares borders with Turkey and Iraq to the west and the Republic of Azerbaijan and Armenia to the north. Regional temperatures (annual mean 13 °C) vary greatly between the coldest and warmest months (> 20 °C), and annual precipitation is 260–350 mm. Siberian low pressure fronts from the north and Mediterranean humidity from the west affect the area, which has a mainly semi-arid climate. From a geological aspect, most parts of this area have sedimentary and quaternary formations. There are several high mountains in this area (e.g., Sahand, Sabalan, Avrin, Buz Sina, Bozgush, and Mishodagh) which exhibit substantial plant diversity, making it one of the main centers of apiculture in Iran. The vegetation in the area is mainly characterized by therophytes and hemicryptophytes as well as several cultivated crops; oak forests represent the main component of the vegetation in the northern parts of East Azerbaijan (Arasbaran). The most representative plant families are Asteraceae, Poaceae, Fabaceae, Lamiaceae, Boraginaceae, Apiaceae and Brassicaceae. Flowering time of these plants covers the entire spring season and peaks between May and June.

Map of Iran and location of sample collection sites in Azerbaijan province, northwestern Iran. This map was generated using ArcGIS 10.2 software (https://www.esri.com/arcgis).

Bee pollen samples

A total of 28 dried bee pollen samples of Apis mellifera (14 from each East Azerbaijan and West Azerbaijan) were obtained from beekeepers. They were obtained using beehives equipped with bottom-fitted pollen traps. Each sample consisted of 200 g of pollen harvested and mixed from various hives, and sun dried by the beekeepers. The sample collection in this study was done based on the distribution and distance of the apiaries, as well as elevation differences and vegetation types in the areas where the apiaries were located. Because the different elevations and slopes can support various types of vegetation, and influence the diversity and botanical origin of the bee pollen. Temperature, relative humidity, and rainfall amount for all apiaries were relatively similar, but location elevation differed (1100–2840 m.a.s.l.). The samples were placed in sterile plastic zip-lock bags, vacuum-packed, and stored at 4 °C until analysis.

Palynological analysis

The palynological analysis of the bee pollen was performed using the method proposed by Almeida-Muradian et al.65. Briefly, 2 g of each sample, approximately 350 pollen pellets, was considered representative for botanical origin. Then, the pollen loads of each sample were grouped into subsamples according to color, and each subsample (plant taxon) was weighed to calculate its percentage in the main sample. The pollen types were then classified into “Predominant pollen” (≥ 45% of the total), “Secondary pollen” (16–44%), “Important minor pollen” (3–15%) and “Minor pollen” (< 3%) based on Louveaux et al.66. One pollen pellet of each subsample was crushed with 50% ethanol to disperse the pollen grains. The dried pollen grains were mounted on stubs using double-sided adhesive tape and coated with gold using a desktop DC Magnetron sputter coater. The samples were then photographed with a scanning electron microscope (Cam Scan Hitachi SU3500). Pollen grains were identified using the Iranian SEM Atlas of Palynology (Mehrabian, Shahid Beheshti University), PalDat website, Erdtman67, Faegri et al.68, Moore et al.69, Hesse et al.70, Halbritter et al.71, Silva et al.72.

Physico-chemical, nutritional, and bioactive compounds analysis

pH

The pH value of each sample was measured with a digital pH meter in the aqueous phase obtained after mixing 5 g of pollen in 20 mL of distilled water.

Moisture content

Aliquots of 2 g crushed bee pollen were weighed and heated at 65 °C for 24 h in a ventilated oven. The samples were then cooled to laboratory temperature, about 25 °C, and weighed. Moisture content was obtained by difference73.

Ash content

The ash content was determined through gravimetry after incineration of 2 g of sample at 600 ± 15 °C until constant weigh74. The values were expressed as a percentage of the original sample on a dry weight basis (g/100 g).

Total protein content

Protein determination was performed by Kjeldahl method based on standard AOAC (1990, 976.05) official method75. One gram of sample was weighted and homogenized. The digestion step (400 °C, four hours) was done with sulfuric acid (96%) in presence of sodium sulfate and copper sulfate as catalysts. Sodium hydroxide (40%) was added, and the digest was distilled in 4% boric acid solution. Titration was performed with 0.1 M hydrochloric acid and the nitrogen content was calculated. Finally, the protein content was estimated by multiplying the nitrogen content by 6.25.

Total lipid content

Total lipids were determined using Soxhlet extraction according to AOAC (1999, 920.39) official method76. Two grams of bee pollen was powdered, and placed in a cellulose thimble. The thimble was then placed inside the extraction chamber, which is suspend above a round bottom flask containing petroleum ether as solvent and below a condenser. The solvent was heated, and the vapors directed through the condenser, where they cooled and converted into liquid form. The liquid solvent was then trickled into the extraction chamber containing the sample. This process was repeated many times for 6 h to ensure through extraction of the lipids. After the extraction, the solvent was evaporated, and the lipid content was determined by weighing the residue.

Total carbohydrate content

The total carbohydrate content was obtained by difference [100—(protein + lipid + ash + moisture)]77.

Total energy

Total energy (in kcal) was estimated using the Atwater coefficients (4 kcal/g for protein and carbohydrate + 9 kcal/g for lipid)78.

Total phenolic content

Total phenolic content was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu colorimetric method, described by Singleton et al.79. 0.1 g of each sample was diluted in 5 mL methanol solution (70% v/v), followed by incubation in a water bath for 10 min at the temperature of 70 °C. After cooling, it was poured into centrifuge tubes for centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 10 min using a Gerber Centrifuge (FUNKE GERBER, Germany). Then, 0.5 mL of the the pollen extract was mixed with 2.5 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (10% v/v), and after 3 min, 2 mL of sodium carbonate solution (7.5% w/v) was added. After 30 min of incubation at room temperature, the absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a UV/VIS spectrophotometer (UNICO, China). Gallic acid was used to construct the calibration curve (R2 = 0.99), and the values of total phenols were expressed as mg gallic acid equivalents per g dry weight of bee pollen (mg GAE/g dw).

Microbiologic examination

Microbiological quality was evaluated according to standard procedures of ISO 1999 (6887–1)80. All microbiological tests were performed in triplicate. Ten grams of each bee pollen sample were added to 90 mL of sterile physiological saline solution [0.85% NaCl in sterile deionized H2O, pH = 7.0 ± 0.05], and vortexed. Decimal serial dilutions to 10−5 were prepared from this homogenate in the same sterile diluents (1:10, by vol). One ml of each dilution was inoculated onto molten 45 ˚C plate count agar (PCA; Ibresco, Karaj, Iran) in a sterile plate, and mixed. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and then colonies were counted and recorded as colony-forming units per gram of bee pollen (CFU g−1).

Statistical analysis

To assess the interrelationships among the physicochemical parameters and microbiological characteristics of the bee pollen samples, Pearson pairwise correlation analysis was conducted at a 95% confidence level. This analysis allowed the identification of significant correlations between key nutritional and microbiological variables such as protein, carbohydrate, phenolic content, and microbial load. To evaluate the influence of botanical origin on the chemical composition and microbiological quality of bee pollen samples, linear regression models were applied within a 95% confidence interval. Parameters such as total carbohydrate, total lipid, total protein, moisture, ash, pH, total phenolic content, and aerobic mesophilic plate count (APC) were treated as dependent variables.

Results and discussion

Palynological identification

A total of 75 pollen types, belonging to 25 families and 64 genera, were identified in the palynological analysis of 28 bee pollen samples. All samples were multifloral because of the presence of different pollen types (Fig. 2). The bee pollens analyzed had between three (sample 15) and ten (samples 4 and 13) pollen types; the mean number was 7.1 with a SD of 1.6. Table 1 shows the identified pollen types and their occurrence and distribution in the samples, and Table 2 shows the sampling locations and full palynological analysis of the bee pollen samples. Asteraceae contributed the highest number of pollen types (24), followed by Fabaceae (7), Rosaceae (6), Brassicaceae (5), Apiaceae (5), Caryophyllaceae (3), Amaranthaceae (2), Lamiaceae (2), Ranunculaceae (2), Papaveraceae (2), Scrophulariaceae (2), and Solanaceae (2). The remaining families registered one pollen type. The most frequent pollen types were those belonging to herbaceous plants, a result already expected due to the vegetation type in the study area. With respect to their frequency of occurrence, Asteraceae was represented in the 27 samples, followed by Papaveraceae (16), Araceae (13), Brassicaceae (11), Caryophyllaceae (11), Fabaceae (10), Apiaceae (9), and Rosaceae (8).

Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) micrographs of some of the observed pollen types in the analyzed bee pollen samples: (a) Amaranthus sp. (Amaranthaceae); (b) Scabiosa sp. (Caprifoliaceae); (c) Allium sp. (Amarylidaceae); (d) Onobrychis sp. (Fabaceae); (e) Helianthus anuus (Asteraceae); (f) Gypsophila sp. (Caryophyllaceae); (g) Papaver bracteatum (Papaveraceae); (h) Xanthium strumarinum (Asteraceae); (i) Echinops sp. (Asteraceae); (j) Ferulago sp. (Apiaceae); (k) Geranium sp. (Geraniaceae); (l) Ceratocephala orthoceras (Ranunculaceae); (m) Sisymbrium sp. (Brassicaceae); (n) Taraxacum officinale (Asteraceae); (o) Astragalus sp. (Fabaceae); (p) Ambrosia sp. (Asteraceae); (q) Arabis sp. (Brassicaceae); (r) Salvia spinosa (Lamiaceae); (s) Epilobium sp. (Onagraceae); (t) Carthamus sp. (Asteraceae).

Botanical origin of bee products has a direct effect on their physicochemical properties. Therefore, determining the botanical origin of bee products is important for standardizing these products. Palynological analysis is the most widely used traditional method to determine the botanical origin of bee products50,52,81. The palynological analysis revealed significant variation in the botanical composition of the bee pollen samples collected from Iran. The bar chart illustrates the relative abundance (%) of pollen grains grouped by plant family, providing insight into the main floral sources exploited by honeybees in the region (Fig. 3). Among the 25 identified families, Asteraceae dominated overwhelmingly, comprising an average of approximately 33% of the pollen content. This dominance aligns with the widespread distribution and ecological prevalence of Asteraceae in the studied area. Its high abundance suggests that it is a primary floral source for foraging bees, likely due to its extended blooming period and high pollen yield. Other prominent families included Brassicaceae (11.5%), Papaveraceae (10.7%), and Fabaceae (9.2%), followed by Apiaceae (8.3%), Caryophyllaceae (7.1%), and Rosaceae (6.7%). These families also exhibit high adaptability and prevalence in various habitats across Iran, especially herbaceous fields, which further supports their frequent representation in bee pollen. The remaining families such as Scrophulariaceae, Caprifoliaceae, and Poaceae had moderate to low representation (ranging between 2 and 5%), while others like Lythraceae, Onagraceae, and Amaryllidaceae showed minimal contribution, typically below 1%. This diversity reflects the multifloral nature of all collected samples, confirming that Iranian bee pollen is derived from a rich and varied botanical environment. The relatively wide error bars for some families, particularly Asteraceae, Brassicaceae, and Papaveraceae, indicate considerable variability among samples, likely due to differences in local flora, seasonality, and foraging preferences. These results are consistent with SEM analysis findings, where Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Rosaceae, Brassicaceae, and Apiaceae were among the most taxonomically rich families. The convergence of taxonomic richness and abundance underlines the ecological importance of these families as consistent and abundant pollen sources for honeybee nutrition.

Palynological analysis of our samples confirmed the richness in important species of Azerbaijan Province. Most of these plants are native and known by their high nectariferous and polliniferous potential82. No existing study has yet compared the plant origins of bee pollen samples collected from Iran. Results of bee pollen load sample analyses of neighboring countries of Iran have been published mainly in Turkey. Many of the pollen types identified in Turkish bee pollen were similar to our results, and Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Rosaceae and Brassicaceae also represented more species than other plant families52,83,84,85. Costa et al.86 reported that the family Fabaceae was most represented in bee pollen samples from the semiarid city of Itaberaba in Brazil during the dry season of 2007, followed by the families Asteraceae, Commelinaceae, and Poaceae. Addi & Bareke87 showed that the highest number of visits by bees has been made to Asteraceae and Fabaceae families. Feás et al.2 studied bee pollen samples from Portugal and identified nine plant families in 22 samples; Cistaceae, Boraginaceae, and Rosaceae were found to be the dominant pollen types. Nuvoloni et al.88 found that Rubus and Castanea were the most abundant pollen genera in Italian bee pollen, and the pollen type variability in the samples was related to their geographical origins. Freire et al.20 determined the botanical origins of Brazilian bee pollens, and seven plant genus were found as predominant pollen types. Sun et al.89 studied the botanical origin of bee pollen samples from Uzbekistan using morphological and molecular methods and reported that Capparaceae, Apiaceae, Hypericaceae, Fabaceae, and Papaveraceae were the major sources of pollen. Bakour et al.18 found that Rutaceae, Apiaceae, and Rosaceae were the most represented families in bee pollen samples from Morocco.

Figure 4 presents the abundance of the most frequent pollen types identified at the genus level across all samples. The analysis shows a highly skewed distribution, where a few genera dominate the pollen composition while most others occur at relatively low frequencies. Papaver, Cirsium, and Brassica were the most abundant genera, each contributing significantly to the total pollen content across the samples. These genera are all characterized by high pollen production and extensive floral availability during peak foraging periods, making them attractive resources for honeybees. Their high representation is also consistent with the dominant families identified in the previous figure (e.g., Papaveraceae, Asteraceae, and Brassicaceae). Genera such as Prunus, Verbascum, Anthemis, and Eryngium were moderately abundant, ranging between 5 and 15%. These plants, commonly found in temperate, open, and semi-natural habitats, also contribute to the seasonal foraging spectrum and reflect the local floristic structure. In contrast, the majority of genera—including Lythrum, Ambrosia, Leontodon, and Echinops—showed low relative abundance, indicating that while present in the environment, they are either less preferred by bees, less abundant in the landscape, low pollen production, or flowering outside the major collection periods. The presence of diverse genera, including both herbaceous and woody taxa (e.g., Rosa, Malus, Allium, Zea, and Salvia), emphasizes the multifloral nature of Iranian bee pollen. This diversity is a valuable feature for consumers, as it indicates a broad range of nutritional and bioactive compounds, which can enhance the health-promoting properties of the pollen.

Honeybees (Apis mellifera) are generalist pollinators that forage on a variety of plant species90. More generalist collection strategies ensure that bees consume a diverse range of nutrients while also diluting their intake of plant protection products and toxins91. During pollen collection, the bees might show preferences regarding floral sources. The dietary needs of bees and their various life stages are diverse, as is the nutritional quality of pollen provided by different plant families and species92. Asteraceae and Fabaceae are known as the largest plant families in Iran in terms of the number of species93,94,95,96,97,98, and the highest number of pollen types in our study were those belonging to these two families. In this study, Asteraceae was not only the most diverse, but also the most frequent plant family. Asteraceae is a large family of flowering plants with more than 2500 species and 1600 genera. The plants of this family have the ability to grow in most habitats due to their high adaptability and are scattered in different parts of the world except Antarctica99. According to Refahi and Alipour82, Fabaceae family members are known as good nectar and pollen producers, and our results confirm their observations. The Fabaceae species have dense inflorescences with small and gently scented flowers that attract bees to collect pollen and nectar, highlighting the importance of this botanic family100. In bee pollen samples evaluated by Almeida-Muradian et al.65 and Estevinho et al.98 pollen types of Fabaceae were also identified. In addition, the study by Di Marco et al.99 confirms the importance of species of this botanical family also as an important source of nectar for bees. The Brassicaceae family stood out in the current study because of the presence of Brassica napus. Rosaceae fruit trees are widely sought by bees at the beginning of spring, when wild plants are not yet in flower. The Papaveraceae family was also highlighted in this work, mainly because of the presence of the Papaver bracteatum pollen type. In addition, Zea mays from the Poacea family is an important representative of an anemophilous taxon in this study. The findings highlight the botanical richness and ecological variety of the regions from which the samples were collected. The dominant genera also reflect the seasonal phenology of regional flora and underline the selective foraging behavior of honeybees in response to pollen availability, accessibility, and nutritional value.

Physico-chemical and nutritional composition

pH

pH measurements presented values between 4.7 and 5.4 with an average of 5.1 ± 0.2. These results confirmed the acidic character of the bee pollen, and are in agreement with those reported in the case of multifloral bee pollen from Romania, Morocco, Turkey, Purtugal and India18,21,85,100,101. pH is a parameter that influences indirectly the shelf life and thus the stability of bee pollen. Low pH has an inhibitory effect on the growth of many microorganisms. This parameter is affected by botanical and geographical origin, conditioning storage and beekeepers’ practices18,21 (Table 3).

Moisture content

The moisture content of the bee pollen samples was found to be between 1.8% and 2.1%, with a mean value of 1.9 ± 0.1 (Table 3). Moisture is another important parameter during the storage of bee pollen, as it influences the pollen’s shelf life. If bee pollen is not stored in suitable conditions, high moisture content will provide an opportunity for the growth of microorganisms. Beekeepers reduce bee pollen moisture content by drying to prevent microbial deterioration. Bee pollen with a moisture content below ~ 6 g/100 g is in the acceptable range for storage stability1,102. Our samples showed an average of moisture lower than that found in other studies18,48,101,103. It is likely because drying bee pollen by direct exposure to the sun is the most commonly used method among beekeepers in Iran, and they dry it more than necessary.

Ash content

The amount of ash, which is the pollen inorganic fraction, in our samples ranged from 2.1% to 3.2% with a mean value of 2.6 ± 0.3 (Table 3), results well within the limits of the standards that set a maximum limit of 4% for bee pollen65. The values are also in agreement with the literature18,52,87,101,103. Ash content is a quality parameter that may be influenced by botanical and geographical origin, soil type, or capacity of the plant to accumulate minerals19,104.

Total carbohydrates content

Carbohydrates are the main pollen fraction, and approximately two-thirds of bee pollen is made up of carbohydrates. Nevertheless, their contents vary significantly, depending on factors such as the plant species, growth conditions, and harvesting methods21,24. In this study the carbohydrate contents ranged between 67.7% (sample 19) and 75.8% (sample 18). The mean value was 71.9 ± 2.3 (Table 3). These results are similar to the findings of Feas et al.2, Yang et al.48, Estevinho et al.98, Nogueira et al.100, Alicic et al.103, and De-Melo et al.105. The values are also higher than those found by Carpes et al.19, Spulber et al.106, Fernández et al.107, and Sagona et al.108. Carbohydrates are important indicators of nutritional value and energy content, corresponding to sugars, starch, and fibers19. The carbohydrates in pollen around the world vary greatly, ranging from 18.50 to 82.80%21. High values of carbohydrates in pollen are attributed to the presence of honey or nectar used by bees to compact the grains50. However, since diverse methods have been used to identify the carbohydrate content of bee pollen, its values also tends to vary21,77.

Total protein content

Protein was the second most abundant component, with values between 16.4% (sample 15) and 24.6% (sample 19). The mean value was 18.9 ± 1.9 (Table 3). According to Campos et al. (2008)1, protein content can vary between 10 and 40% in bee pollen. Our results were similar to those obtained by2,18,24,52,84,101,103,106,109. Gardana et al.110 observed a lower content in terms of proteins (12.3%) for bee pollen from Spain. For pollen from Portugal, De-Melo et al.105 found that the total protein content in bee pollen samples from Brazil was 7.9% to 32.9%, values which differ from those of our samples, likely due to their botanical origins. In addition, differences within the same plant species growing under different environmental conditions can also affect the contents of bee pollen. Moreover, the application of varied analytical techniques may result in dissimilar measurements for the same type of nutrient3. Protein and amino acid concentration in pollen play crucial roles in bee health and reproduction as well as colony development111,112,113. Although studies have indicated that honeybees do not forage preferentially on pollen with higher protein concentrations92,114, the protein–to-lipid ratio in bees has been found effective in figuring out the bees’ preference115,116. Our results clearly revealed that all samples were rich in total protein (> %16).

Total lipid content

Lipids are considered the third group of substances present in the bee pollen, after carbohydrates and proteins, and are vital for the generation of royal jelly101. Total lipid content in this study was highly variable and ranged from 2.1 (sample 20) to 8.9 (sample 9) g/100 g (mean 4.6 ± 1.8) (Table 3). These results are supported by the findings of2,24,52,84,101,103. However, the values differ from those obtained by48 for bee pollen from China,106 for Romanian bee pollen,100 for bee pollen from Spain, and by98 for bee pollen collected in Portugal. Lipids, such as fatty acids, sterols, and triglycerides, are of great importance in the food industry as they represent energy source in the diet and, consequently, directly affect the food nutritional values117,118.

Energy

The energy values of the pollen, calculated using Atwater’s constant, ranged from 392.1 (sample 20) to 425.7 (sample 9) kcal/100 g. The mean value was 404.9 ± 9.5. The results are in agreement with those found by2,48,100,119. However, these valuse are higher than those obtained by101,106. The energy value is directly associated with the number of macronutrients accumulated in a given food120. As seen in Table 3, bee pollen is a good source of energy.

Total phenolic content

The total phenolic content values in bee pollen samples varied between 6.0 (samples 3, 15, 27) and 11.5 (sample 4) mg GAE/g. The mean value was 6.9 ± 1.1 (Table 3). The highest polyphenol content was detected in pollen collected from several plants, whereas the lowest was detected in samples dominated by Brassica napus pollen. These findings were in the same range as those reported for Tuscanian bee pollen (578 to 2015 mg/100gm)121, and Romanian bee pollen (4.64 to 17.93 GAE mg/g)101, and bee pollen from Bosnia and Herzegovina (4.95 to 13.37 GAE mg/g)100, while the values were lower than those obtained by52 for Turkish bee pollen (26.69–43.42 GAE mg/g), by122 for bee pollen from Brazil (33.73–75.60 GAE mg/g), by123 for bee pollen from Baltic region (14.2–26.8 GAE mg/g), by21 for Indian bee pollen (9.79–35.63 GAE mg/g), and by2 for Portuguese bee pollen (12.9–19.8 GAE mg/g). Straumite et al.124 found that the total phenolic content of bee pollen samples from Latvia ranged between 4.7 and 32.1 mg GAE/g. Morais et al.28 studied the relationship between the geographical origin and the antioxidant activity of heteroflorous pollen samples coming from different natural parks of Portugal and found significant differences in the total polyphenol content and antioxidant activity among most of the samples taken. These results led the authors to affirm that these differences are attributable to both geographical and botanical origin. Polyphenols or phenolic compounds are secondary metabolites present in all parts of plants. As carbohydrates, volatile compounds of nectar are important for the function of attraction; secondary metabolites are considered as a plant defense and have a less obvious benefit for pollinators125. Phenolic content of bee pollen varies according to its botanical and geographic origins as well as soil type, climatic conditions, time of harvest, and beekeeper activities89,126. These phyto-compounds present a wide range of biological activities and provide great protection against many chronic pathologies involving oxidative stress such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular affections, and aging127.

Microbiological quality

Aerobic mesophilic microorganisms were found in all the bee pollen samples taken in this study. Their quantity ranged from 1.2 × 102 cfu/g for sample 22 to 6.0 × 103 in sample 14 (Table 3). The mean value of APC in bee pollen samples was 1.8 × 103 cfu/g. Arruda et al. 128 studied the microbiological quality of Brazilian bee pollen and found aerobic mesophiles in 56% of the samples, oscillating between < 10 and 1.27 × 103 cfu/g. De-Melo et al.129 reported values ranging from < 10 to 1.1 × 104 cfu/g. Estevinho et al.98 identified the aerobic mesophiles in 40% of bee pollen samples that ranged from 7.6 × 102 to 2.8 × 103 cfu/g. Nogueira et al.100 reported aerobic mesophiles in 12.5% of the bee pollen samples from spain and portugal, ranging between < 10 and 8.7 × 103 cfu/g. The total aerobic mesophiles obtained in our study were lower than those found by Beev et al.130 in Bulgaria, which ranged from 4 × 102 to 6.7 × 104 cfu/g, and by Vargas-Abella et al.131 in Colombia, which ranged from 9 × 103 to 1.2 × 104 cfu/g. However, the results were higher than those reported from Portuguese bee pollen by2,132, which ranged from 3.6 × 10 to 1.4 × 103 cfu/g, and < 10 to 2.4 × 103 cfu/g respectively.

Bee pollen is a nutritious substance that, in proper conditions, strongly supports microbial growth. Along with the nutritional requirements, microbial growth is affected by numerous environmental conditions, like relative humidity, temperature, concentration of antimicrobial compounds, and explicit factors in relation to the existing microbial flora2,98. Enumeration of aerobic mesophilic microorganisms is commonly used as a general indicator of microbiological quality in foodstuffs133. The lowest APC seen in sample 22 and the highest seen in sample 14 as well as the overall variation in microbial count of different bee pollen samples may occur because of differences in harvesting histories, handling, and storage conditions as well as the intrinsic and explicit factors of each sample. Various researchers have emphasized the potential adverse effect of non-hygienic collection sites, environmental pollution, and inappropriate treatment and storage conditions on the microbial quality of bee pollen2,98,100,133. Attention to hygienic practices in pollen harvesting, handling, and storage is a key factor in obtaining a pollen product with good microbiological quality. The microbiological quality of bee pollen, especially the absence of fungi and pathogens, should also be considered an important criterion88. Cross-contamination by beekeepers and pollen handlers may result in the pollen acquiring pathogenic microorganisms. These microorganisms can easily propagate under proper conditions and reach an infective dose. Beekeepers do not usually harvest the pollen on a regular daily basis, and pollen, which is a highly hygroscopic substance, absorbs water in environments with relatively high humidity, making them more favorable for microbial growth. A higher relative humidity during the handling and storage of pollen will result in higher water activity which provides a supportive condition for the growth of a broader spectrum of microorganisms. Drying is a crucial step in pollen production, and any impairment in this stage will cause a remarkable imperfection in the microbiological quality. The drying step must be as quick and perfect as possible, and the conventional air drying procedures used by Iranian beekeepers are not appropriate in this aspect. Moreover, high temperature during the air drying process could contribute to microbial growth in the samples128. pH is another main factor influencing microbial growth in foods. The 25% suspensions of the bee pollen samples had acidic pH values ranging from 4.7 to 5.4 (Table 3). Although acidic pH in this range suppresses the propagation of pathogens, most pathogens can survive in this pH range and should be considered as a potential health risk for consumers. Our results prove this probability and confirm the necessity of hygienic practices in producing bee pollen-based products to enhance their microbiological quality.

Statistical analysis

Correlation analysis was conducted to explore relationships among physicochemical, nutritional, and microbiological parameters of the 28 bee pollen samples. Figure 5 illustrates the scatter plots with fitted trend lines, and Table S1 and Figure S1 (Supporting Information) summarizes the corresponding Pearson correlation coefficients, confidence intervals, and p-values. A moderate positive correlation was observed between pH and altitude (r = 0.364, p = 0.057), suggesting that pollen collected from higher elevations tends to have a slightly higher pH. Although this relationship approached statistical significance, the p-value indicates a trend rather than a definitive association. Carbohydrate content was significantly positively correlated with pH (r = 0.484, p = 0.009), implying that bee pollen with higher pH levels generally contains more carbohydrates. Conversely, protein content and pH were negatively correlated (r = − 0.377, p = 0.048), indicating that lower pH samples are likely to have higher protein content. Moisture was positively associated with aerobic mesophilic bacterial count (APC) (r = 0.542, p = 0.003), highlighting that higher moisture levels can support microbial proliferation and potentially affect microbiological quality. A similar results were obtained by88,98,124, who found that pollens with higher water activity were positively correlated with total aerobic mesophiles.

A significant negative correlation was found between energy value and ash content (r = − 0.418, p = 0.027), as well as between energy and both carbohydrate content (r = − 0.536, p = 0.003) and protein content (r = − 0.667, p < 0.001). Interestingly, energy was extremely positively correlated with lipid content (r = 0.995, p < 0.001), underlining lipids as the most energy-dense macronutrient among the analyzed variables. The data also revealed significant inverse relationships between macronutrients. For instance, lipid content was negatively correlated with carbohydrate content (r = − 0.556, p = 0.002), and protein content was negatively correlated with carbohydrates (r = − 0.667, p < 0.001), indicating a possible nutrient trade-off mechanism in pollen composition depending on botanical origin.

To evaluate the influence of botanical composition on the acidity of bee pollen, regression analyses were performed between pH values and the relative abundance of pollen from dominant plant families. The results are presented in Fig. 6 and supported by the correlation analysis (Table S2 and Figure S1- Supporting information). Significant negative correlations were observed between pH and the relative proportions of Brassicaceae (r = − 0.394, p = 0.038), Caryophyllaceae (r = − 0.397, p = 0.036), and Fabaceae (r = − 0.572, p = 0.001). These findings indicate that an increased presence of pollen from these families is associated with a decrease in the pH of the final bee pollen product. The strongest inverse association was observed for Fabaceae, with pH decreasing by approximately 0.012 units for each percentage increase in Fabaceae content. Conversely, Scrophulariaceae showed a statistically significant positive correlation with pH (r = 0.447, p = 0.017), suggesting that pollen samples with higher proportions of this family tend to be less acidic. Regression analysis confirmed a slope coefficient of + 0.01421, indicating a potential buffering effect from this botanical group. Although correlations with Asteraceae (r = 0.325, p = 0.091) and Hypericaceae (r = 0.328, p = 0.088) were positive, they did not reach statistical significance. Overall, the data suggest that specific botanical sources contribute measurably to the acidity profile of bee pollen, with some families exerting acidifying effects while others may have an alkalizing influence.

The influence of botanical origin on the mineral content of bee pollen was evaluated by examining the correlation between the proportion of specific pollen families and ash content (%). As illustrated in Fig. 6, a statistically significant positive correlation was observed between the proportion of Papaveraceae pollen and ash content (r = 0.418, p = 0.027). The 95% confidence interval for the correlation coefficient (0.053 to 0.684) further supports the robustness of this association. Regression analysis indicated that increased representation of Papaveraceae pollen in the samples was associated with a linear rise in ash content, suggesting a direct botanical contribution to the mineral profile of bee pollen. This result may reflect the inherent mineral richness of Papaveraceae-derived pollen grains, or it may suggest environmental factors related to their floral ecology that contribute to increased inorganic residue in the final product. Arruda et al.128 reported that there is a directly proportional relationship between the values of ashes and the percentages of Cocos nucifera, M. verrucosa, Myrcia and Tapirira, and an inversely proportional relationship between content of ashes and Asteraceae, Euphorbiaceae, and Poaceae in Brazilian bee pollen. The level of minerals in bee pollen can vary considerably throughout the year due to differences in the floral source134.

Statistical analyses revealed significant correlations between the relative abundance of certain pollen families and the total carbohydrate content in the bee pollen samples. Among these, the Apiaceae family exhibited a positive correlation with carbohydrate content (ρ = 0.374, p = 0.050), suggesting that higher proportions of Apiaceae pollen were associated with increased carbohydrate levels in the samples. Conversely, the Poaceae family showed a negative correlation of equal magnitude but opposite direction (ρ = − 0.374, p = 0.050), indicating that sample richer in Poaceae pollen tended to has lower carbohydrate concentrations. These correlations were statistically significant at the 0.05 level, with 95% confidence intervals narrowly excluding zero in both cases, reinforcing the potential biological relevance of these relationships. The regression plot for Apiaceae (Fig. 6) shows a clear upward trend, further illustrating this positive association. Similarly, although the plot for Poaceae was not included, the negative correlation value supports a downward trend. Spulber et al.103 showed that the highest value for carbohydrate content in pollen dominated by Plantago sp. (Plantaginaceae), and the lowest in Zea mays (Poaceae) pollen.

A statistically significant positive correlation was observed between the relative abundance of pollen from the Rosaceae family and the protein content of bee pollen samples (r = 0.383, p = 0.044). This indicates that samples containing higher proportions of Rosaceae pollen tend to have higher protein percentages. The 95% confidence interval for the correlation coefficient (0.011 to 0.661) further supports the reliability of this association. As shown in Fig. 6, a linear regression model illustrates the upward trend in protein content with increasing Rosaceae pollen percentage. The regression line is accompanied by 95% prediction bands, reflecting the expected variability in protein values. These findings suggest that Rosaceae species may contribute significantly to the nutritional value of Iranian bee pollen, particularly in enhancing its protein profile. Conversely, the correlation between Scrophulariaceae pollen and protein content, while negative (r = − 0.372), was not statistically significant (p = 0.051). Although this relationship approaches significance, it requires further investigation with larger sample sizes to confirm its relevance. Conti et al.135 reported that the pollens of Hedera (Araliaceae), Rubus (Rosaceae) and Castanea (Fagaceae) were positively correlated with protein content, while those of Plantago (Plantaginaceae) and Erica (Ericaceae) were negatively correlated with it. Campos et al.77 showed the differences in protein content based on plant origin, and reported that the lowest value was observed for Actinidia chinensis (9.70%) and the highest for Crocus sativa (26.08%). Several authors have reported that sunflower pollen has low protein and high lipid and carbohydrate content while high protein content is characteristc for willow pollen and pollen of Brasicaceae and Rosaceae families106,136,137,138,139.

The microbiological quality of bee pollen samples, assessed through aerobic mesophilic plate counts (APC), showed statistically significant correlations with the abundance of specific pollen families. Notably, a positive correlation was observed between Rosaceae pollen content and APC values (r = 0.399, p = 0.036), suggesting that higher proportions of Rosaceae pollen may be associated with increased microbial load. The 95% confidence interval (0.030 to 0.672) confirms the reliability of this association. As visualized in Fig. 6, the regression line clearly indicates a rising trend in APC values with increasing Rosaceae presence. Conversely, a negative and statistically significant correlation was found between Fabaceae pollen and APC levels (r = − 0.409, p = 0.031), indicating that samples richer in Fabaceae pollen may have lower microbial contamination. This inverse relationship could reflect the influence of bioactive compounds with antimicrobial properties, commonly found in Fabaceae species140,141,142. While Hypericaceae showed a moderate positive correlation with APC (r = 0.327), this was not statistically significant (p = 0.090), suggesting a potential trend that requires further validation with expanded datasets.

Conclusions

For the first time, the botanical origins of Iranian dried bee pollen samples were determined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). In addition, their physicochemical parameters, nutritional values, and microbiological quality were investigated. The bee pollen samples were analyzed in the same form as they are offered to consumers (i.e., processed rather than in their raw state directly from the hive). This approach ensured that any changes resulting from post-harvest processes were accurately captured, reflecting the quality and safety of the final product. This study provided insights into the diversity of plants used by bees in northwestern Iran, with Asteraceae, Fabaceae, Rosaceae, Brassicaceae, and Apiaceae being the most abundant plant families found in the bee pollen samples. Furthermore, the results demonstrated that Iranian bee pollen is a rich source of proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, polyphenols, and energy, offering valuable nutritional benefits. The observed similarities in the chemical composition of certain samples are likely attributed to the ecological and botanical characteristics of the study area, which may have influenced these properties. Some samples exhibited high levels of microbial contamination, which could be related to differences in harvesting practices, handling, storage conditions, or intrinsic and extrinsic factors specific to each sample. Our results suggest that greater attention should be paid to the microbiological quality of this product. The findings of this study can help local beekeepers make informed decisions regarding the selection and management of foraging plants, thereby supporting the health and productivity of their colonies. This information could also play an important role in quality control and improve the commercial value of bee pollen.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary information files) or are availabe from the corresponding author (A. R. Mehrabian: a_mehrabian@sbu.ac.ir) on reasonable request.

References

Campos, M. et al. Pollen composition and standardisation of analytical methods. J. Apic. Res. 47, 156–163 (2008).

Feás, X., Vázquez-Tato, M. P., Estevinho, L., Seijas, J. & Iglesias, A. Organic bee pollen: Botanical origin, nutritional value, bioactive compounds. Antioxid. Act. Microbiol. Qual. Mol. 17, 8359–8377 (2012).

Rodríguez-Pólit, C. et al. Chemical Properties and biological activity of bee pollen. Molecules 28, 7768 (2023).

Baldi, C. B., Grasso, D., Pereira, S. C. & Fernández, G. Caracterización bromatológica del pólen apícola argentino. Cienc. Docen. Tecnol. 29, 145–181 (2004).

Marchini, L. C., Reis, V. D. A. & Moreti, A. C. C. C. Composição físico-química de amostras de pólen coletado por abelhas Africanizadas Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera:Apidae) em Piracicaba. Estado de São Paulo. Ciênc. Rural 36, 949–956 (2006).

Dimou, M., Tananaki, C., Liolios, V. & Thrasyvoulou, A. Pollen foraging by honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) in Greece: Botanical and geographical origin. J. Apic. Sci. 58, 11–23 (2014).

Kocot, J., Kiełczykowska, M., Luchowska-Kocot, D., Kurzepa, J. & Musik, I. Antioxidant potential of propolis, bee pollen, and royal jelly: Possible medical application. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 7074209 (2018).

Durazzo, A. et al. Bee products: A representation of biodiversity, sustainability, and health. Life 11, 970 (2021).

Krishnan, S., Wiederkehr Guerra, G., Bertrand, D., Wertz-Kanounnikoff, S. & Kettle, C.J. The Pollination Services of Forests—A Review of Forest and Landscape Interventions to Enhance Their Cross-Sectoral Benefits. Forestry Working Paper. FAO & Biodiversity International, No. 15 (2020).

Aylanc, V., Falc˜ao, S. I., Ertosun, S. & Vilas-Boas, M. From the hive to the table: Nutrition value, digestibility and bioavailability of the dietary phytochemicals present in the bee pollen and bee bread. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 109, 464–481 (2021).

Bogdanov, S. Pollen: Nutrition, functional properties, health: A review. Bee Prod. Sci. 20, 1–34 (2011).

Denisow, B. & Denisow-Pietrzyk, M. Biological and therapeutic propertis of bee pollen: A review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 96, 4303–4309 (2016).

Khalifa, S. et al. Bee pollen: Current status and therapeutic potential. Nutrients 13, 1876 (2021).

El Ghouizi, A. et al. Bee pollen as functional food: Insights into Its composition and therapeutic properties. Antioxidants 12, 557 (2023).

Komosinska-Vassev, K., Olczyk, P., Kafmierczak, J., Mencner, L. & Olczyk, K. Bee pollen: Chemical composition and therapeutic application. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2015, 297425 (2015).

Ecem Bayram, N. Vitamin, mineral, polyphenol, amino acid profle of bee pollen from Rhododendron ponticum (source of “mad honey”): nutritional and palynological approach. J. Food Measurem. Charact. 15, 2659–2666 (2021).

Morgano, M. A. et al. A comprehensive investigation of the mineral composition of Brazilian bee pollen: Geographic and seasonal variations and contribution to human diet. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 23, 727–736 (2012).

Bakour, M. et al. Exploring the palynological, chemical, and bioactive properties of non-studied bee pollen and honey from Morocco. Molecules 27, 5777 (2022).

Carpes, S. T. et al. Palynological and physicochemical characterization of Apis mellifera L. bee pollen in the Southern region of Brazil. J. Food Agric Env. 7, 667–673 (2009).

Freire, K. R. L. et al. Palynological origin, phenolic content, and antioxidant properties of honeybee collected pollen from Bahia. Brazil. Mol. 17, 1652–1664 (2012).

Thakur, M. & Nanda, V. Assessment of physico-chemical properties, fatty acid, amino acid and mineral profile of bee pollen from India with a multivariate perspective. J. Food Nutr. Res. 57, 328–340 (2018).

Lee, K. H., Kim, A. J. & Choi, E. M. Antioxidant and antiinflammatory activity of pine pollen extract in vitro. Phytother. Res. 23, 41–48 (2009).

Pascoal, A., Rodrigues, S., Teixeira, A., Feás, X. & Estevinho, L. M. Biological activities of commercial bee pollens: Antimicrobial, antimutagenic, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory. Food Chem. Toxicol. 63, 233–239 (2014).

Li, Q. et al. Bee pollen extracts modulate serum metabolism in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury mice with anti-inflammatory effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67, 7855–7868 (2019).

Mokhtari, M. B. et al. Palynological analysis, phenolic components and anti-inflammatory activity of some bee pollens collected from the northeast region of algeria. Uluda˘g Arı Derg. 22, 45–58 (2022).

Kosedag, M. & Gulaboglu, M. Pollen and bee bread expressed highest anti-inflammatory activities among bee products in chronic inflammation: An experimental study with cotton pellet granuloma in rats. Inflammopharmacology 31, 1967–1975 (2023).

Graikou, K. et al. Chemical analysis of Greek pollen-antioxidant, antimicrobial and proteasome activation properties. Chem. Cent. J. 5, 33 (2011).

Morais, M., Moreira, L., Feás, X. & Estevinho, L. M. Honeybee-collected pollen from five portuguese natural parks: Palynological origin, phenolic content, antioxidant properties and antimicrobial activity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 49, 1096–1101 (2011).

El Ghouizi, A., Nawal, E. M., Bakour, M. & Lyoussi, B. Moroccan monofloral bee pollen: Botanical Origin, physicochemical characterization, and antioxidant activities. J. Food Qual. 2021, 8877266 (2021).

Tutun, H., Kaya, M. M., Usluer, M. S. & Kahraman, H. A. Bee pollen: Its antioxidant activity. Uluda˘g Arı Derg. 21, 119–131 (2021).

García, M., Pérez-Arquillue, C., Juan, T., Juan, M. I. & Herrera, A. Pollen analysis and antibacterial activity of Spanish honeys. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 7, 155–158 (2001).

Basim, E., Basim, H. & Ozcan, M. Antibacterial activities of Turkish pollen and propolis extracts against plant bacterial pathogens. J. Food Eng. 77, 992–996 (2006).

Bartkiene, E. et al. Variations of the antimicrobial, antioxidant, sensory attributes and biogenic amines content in Lithuania-derived bee products. LWT 118, 108793 (2020).

Asoutis Didaras, N., Dimitriou, T., Daskou, M., Karatasou, K. & Mossialos, D. In vitro assessment of the antiviral activity of greek bee bread and bee collected pollen against enterovirus d68. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 11, e4859 (2022).

Sawicki, T., Starowicz, M. & Kł˛ebukowska, L. & Hanus, P.,. The profile of polyphenolic compounds, contents of total phenolics and flavonoids, and antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of bee products. Molecules 27, 1301 (2022).

Ozcan, M. Inhibition of Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 by pollen and propolis extracts. J. Med. Food 7, 114–116 (2004).

Kurek-Górecka, A., Górecki, M., Rzepecka-Stojko, A., Balwierz, R. & Stojko, J. Bee products in dermatology and skin care. Molecules 25, 556 (2020).

Wang, B. et al. Antitumor activity of bee pollen polysaccharides from Rosa rugosa. Mol. Med. Rep. 7, 1555–1558 (2013).

Aylanc, V. et al. Evaluation of antioxidant and anticancer activity of mono- and polyfloral moroccan bee pollen by characterizing phenolic and volatile compounds. Molecules 28, 835 (2023).

Münstedt, K. & Männle, H. Bee products and their role in cancer prevention and treatment. Complement. Ther. Med. 51, 102390 (2020).

Komosinska-Vassev, K., Olczyk, P. & Ka´zmierczak, J., Mencner, L. & Olczyk, K.,. Bee pollen: Chemical composition and therapeutic application. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 1, 297425 (2015).

Antonelli, M., Donelli, D. & Firenzuoli, F. Therapeutic efficacy of orally administered pollen for nonallergic diseases: An umbrella review. Phytother. Res. 11, 2938–2947 (2019).

Campos, M., Markham, K. R., Mitchell, K. A., Cunha, D. A. & A. P.,. An approach to the characterization of bee pollens via their flavonoid/phenolic profiles. Phytochem. Anal. 8, 181–185 (1997).

Algethami, J. S. et al. Bee pollen: Clinical trials and patent applications. Nutrients 14, 2858 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Characterization and quantification by LC-MS/MS of the chemical components of the heating products of the flavonoids extract in pollen typhae for transformation rule exploration. Molecules 20, 18352–18366 (2015).

Erkmen, O. & Ozcan, M. M. Antimicrobial effects of Turkish propolis, pollen, and laurel on spoilage and pathogenic foodrelated microorganisms. J. Med. Food 11, 587–592 (2008).

Szszesna, T., Rybak-Chielewska, H. & Chmielewski, W. Sugar composition of pollen loads harvested at different periods of the beekeeping season. J. Apic. Scienc 46, 107–115 (2002).

Yang, K. et al. Characterization of chemical composition of bee pollen in china. J. Agric. Food Chem. 61, 708–718 (2013).

Gasparotto, J. A. et al. Impact of origin on bioactive compounds and nutritional composition of bee pollen from southern Brazil: A screening study. Food Res. Int. 77, 82–91 (2015).

Kostić, A. Ž et al. Physicochemical composition and techno-functional properties of bee pollen collected in Serbia. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 62, 301–309 (2015).

Lau, P., Lesne, P., Grebenok, R. J., Rangel, J. & Behmer, S. T. Assessing pollen nutrient content: A unifying approach for the study of bee nutritional ecology. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Biol. Sci. 377, 20210510 (2022).

Mayda, N., Özkök, A., Ecem Bayram, N., Gerçek, Y. C. & Sorkun, K. Bee bread and bee pollen of different plant sources: Determination of phenolic content, antioxidant activity, fatty acid and element profiles. J. Food Meas. Charact. 14, 1795–1809 (2020).

Barth, O. M. et al. Evaluation of the botanical origin of commercial dry bee pollen load batches using pollen analysis: A proposal for technical standardization. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 82, 893–902 (2010).

Atsalakis, E., Chinou, I., Makropoulou, M., Karabournioti, S. & Graikou, K. Evaluation of phenolic compounds in cistus creticus bee pollen from Greece. Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Nat. Prod. Commun. 12, 1934578X1701201141 (2017).

Maruyama, H., Sakamoto, T., Araki, Y. & Hara, H. Anti-inflammatory effect of bee pollen ethanol extract from Cistus sp. of Spanish on carrageenan-induced rat hind paw edema. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 10, 1–11 (2010).

Yamaguchi, M., Hamamoto, R., Uchyama, S. & Hashimoto, K. Preventive effects of bee pollen cistus ladaniferous extract on bone loss in streptozotocin rats in vivo. J. health sci. 53, 190–195 (2007).

Shakoori, Z., Mehrabian, A., Minai, D., Salmanpour, F. & Khajoei Nasab, F. Assessing the quality of bee honey on the basis of melissopalynology as well as chemical analysis. PLoS ONE 18, 0289702 (2023).

Alves, R. F. & Santos, F. A. R. Arecaceae potential for production of monofloral bee pollen. Grana 57, 1–10 (2016).

Kast, C., Kilchenmann, V., Reinhard, H., Bieri, K. & Zoller, O. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids: The botanical origin of pollen collected during the flowering period of Echium vulgare and the stability of pyrrolizidine alkaloids in bee bread. Molecules 24, 2214 (2019).

Brodschneider, R. & Crailsheim, K. Nutrition and health in honey bees. Apidologie 41, 278–294 (2010).

Matuszewska, E., Klupczynska, A., Maciołek, K., Kokot, Z. J. & Matysiak, J. Multielemental analysis of bee pollen, propolis, and royal jelly collected in west central Poland. Molecules 26, 2415 (2021).

Noroozi, J. Plant Biogeography and Vegetation of High Mountains of Central and South-West Asia. 17, 360, (Springer International Publishing, 2020).

Noroozi, J. et al. Hotspots of vascular plant endemism in a global biodiversity hotspot in Southwest Asia suffer from significant conservation gaps. Biol. Conserv. 237, 299–307 (2019).

Hassanpouraghdam, M. B. et al. Diversity and distribution patterns of endemic medicinal and aromatic plants of Iran: Implications for conservation and habitat management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 1552 (2022).

Almeida-Muradiana, L. B., Pamplonaa, L. C., Coimbraa, S. & Barth, O. M. Chemical composition and botanical evaluation of dried bee pollen pellets. J. Food Compos. Anal. 18, 105–111 (2005).

Louveaux, J., Maurizio, A. & Vorwohl, G. Methods of melissopalynology. Bee World 59, 139–157 (1978).

Erdtman, G. Handbook of palynology: morphology-taxonomy-ecology: an introduction to the study of pollen grains and spores. (1969).

Faegri, K., Kaland, P.E. & Krzywinski, K. Textbook of pollen analysis. 4, 328. 1989. Preprinted (1992).

Moore, P.D., Webb, J.A. & Collison, M.E. Pollen analysis. 216. (1991).

Hesse, M. et al. Pollen terminology: An illustrated handbook (Springer-Verlag Wien, 2009).

Halbritter, H. et al. Illustrated pollen terminology (Springer, 2018).

Silva, C.I. da, Radaeski, J.N., Arena, M. V. N. & Bauerman, S.G. Atlas of pollen and plants used by bees. CISE-Consultoria Inteligente em Servicos Ecossistemicos. ISBN 978–65–86372–01–4 (2020).

Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). Official Methods of Analysis, 934.01, 15th ed. (1990).

Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). Official Methods of Analysis, 942.05, 15. (1990).

Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). Official Methods of Analysis, 976.05, 15. (1990).

Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). Official Methods of Analysis, 920.39, 17. (1999).

Campos, M. et al. Standard methods for pollen research. J. Apic. Res. 60, 1–109 (2021).

Merill, A. L. & Watt, B. K. Energy Value of Foods, Basis and Derivation. In Agriculture Handbook, 74. United States Department of AgricultureUSA (1995).

Singleton, V. L., Orthofer, R. & Lamuela-Raventos, R. M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 299, 152–178 (1999).

ISO 6887–1. Microbiology of the food chain- Prepration of test samples, initial suspension and decimal dilutions for microbiological examination (1999).

Escriche, I., Juan-Borrás, M., Visquert, M. & Valiente, J. M. An overview of the challenges when analysing pollen for monofloral honey classifcation. Food Control 143, 109305 (2023).

Refahi, M. & Alipour, M. J. Beeplants of Iran. Zarih Aftab, 464. (2018).

Alimoglu, G. et al. Monofloral and polyfloral bee pollens: Comparative evaluation of their phenolics and bioactivity profles. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 142, 110973 (2021).

Bay, V., Topal, E., Çakıcı, N., Yıldızdal, İ & Tosunoglu, A. Palynologıcal analyses, chemical and mineral composition of some honeybee polen pellets. Ulu. Arı. Derg. 21, 187–197 (2021).

Çobanoğlu, D. N., Felek, I. & Dündar, O. Palynological, Antioxidant and physicochemical properties of pollen loads from eastern anatolia. Bee Stud. 13, 31–38 (2021).

Costa, S. N., Alves, R. M. D. O., Carvalho, C. A. L. D. & Conceicao, P. D. J. Pollen sources used by Apis mellifera Latreille in the semiarid region. Cien. Anim. Bras. 16, 491–497 (2015).

Addi, A. & Bareke, T. U. R. A. Floral resources diversity of honeybees in important types of vegetation of Ethiopia. Asian J. For. 3, 64–68 (2019).

Nuvoloni, R. et al. Bee pollen retailed in Tuscany (Italy): Labelling, palynological. Microbiological, and mycotoxicological profile. LWT- Food Sci. Technol. 140, 110712 (2021).

Sun, S., Mohamadzade Namin, S., Ghosh, S. & Jung, C. Integrated identification of the botanical origins of Uzbekistan bee pollen by morphological and molecular methods. J. Apicult. 39, 133–139 (2024).

Koppler, K., Vorwohl, G. & Koeniger, N. Comparison of pollen spectra collected by four different subspecies of the honey bee Apis mellifera. Apidologie 38, 341–353 (2007).

Eckhardt, M., Haider, M., Dorn, S. & Muller, A. Pollen mixing in € pollen generalist solitary bees: A possible strategy to complement or mitigate unfavourable pollen properties?. J. Anim. Ecol. 83, 588–597 (2014).

Roulston, T. H., Cane, J. H. & Buchmann, S. L. What governs protein content of pollen: Pollinator preferences, pollen pistil interactions, or phylogeny?. Ecol. Monogr. 70, 617–643 (2000).

Noroozi, J., Akhani, H. & Breckle, S. W. Biodiversity and phytogeography of the alpine flora of Iran. Biodivers. Conserv. 17, 493–521 (2008).

Ghahremaninejad, F. & Nejad Falatoury, A. An update on the flora of Iran: Iranian angiosperm orders and families in accordance with APG IV. Nova Biologica Reperta. 3, 80–107 (2016).

Hosseini, Z., Bartoli, F., Cicinelli, E. & Lucchese, F. First floristic investigation in archaeological sites of Iran: features and plant richness of the Pasargadae World Heritage Site. Plant Biosystems-An Int. J. Deal. Aspect. Plant Biol. 157, 605–621 (2023).

Güneş, A., Kordali, Ş, Turan, M. & Bozhüyük, A. U. Determination of antioxidant enzyme activity and phenolic contents of some species of the Asteraceae family from medicinal plants. Ind. Crops Prod. 137, 208–213 (2019).

Carneiro-Neto, T. F. S. et al. Spectrum of Pollen stored by Melipona mandacaia (Smith, 1863) (Hymenoptera: Apidae, Meliponini) in an Urban Arid Landscape. Sociobiology 64, 284–291 (2017).

Estevinho, L. M., Rodrigues, S., Pereira1, A. P. & Feas, X. Portuguese bee pollen: Palynological study, nutritional and microbiological evaluation. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol 47, 429–435 (2012).

Di Marco, G. et al. Geographical, botanical and chemical profile of monofloral Italian honeys as food quality guarantee and territory brand. Plant Biosys. 151, 450–463 (2017).

Nogueira, C. et al. Commercial bee-pollen with different geographical origins: A comprehensive approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 13, 11173–11187 (2012).

Oroian, M., Dranca, F. & Ursachi, F. Characterization of Romanian bee pollen—An important nutritional source. Foods 11, 2633 (2022).

Bogdanov, S. Quality and standards of pollen and beeswax. Apiacta 38, 334–341 (2004).

Alicic, D. et al. Physicochemical propertes and antoxidant capacity of bee pollen collected in Tuzla Canton (B&H). J. Cent. Eur. Agric. 21, 42–50 (2020).

Villanueva, M. T. O., Marquina, A. D., Serrano, R. B. & Abell´an, G. B.,. Importance of bee collected pollen in the diet: a study of its composition. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 53, 217–224 (2002).

De-Melo, A. A. M. et al. Phenolic profile by HPLC-MS, biological potential, and nutritional value of a promising food: Monofloral bee pollen. J. Food Biochem. 42, e12536 (2018).

Spulber, R., Dogaroglu, M., Babeanu, N. & Popa, O. Physicochemical characteristics of fresh bee pollen from different botanical origins. Rom Biotechnol Lett. 23, 13357–13365 (2018).

Fernández, L. A. et al. Microbiological and chemical characterization of bee pollen throughout the production process in the Southwest of Buenos Aires Province (Argentina). J. Apic. Res. 59, 156–159 (2020).

Sagona, S. et al. Palynological origin, chemical composition, lipid peroxidation and fatty acid profile of organic Tuscanian bee-pollen. J. Apic. Res. 56, 136–143 (2017).

Martins, M. C. T., Morgano, M. A., Vicente, E., Baggio, S. R. & Rodriguez-Amaya, D. B. Physicochemical composition of bee pollen from eleven Brazilian states. J. Apic. Sci. 55, 107–116 (2011).

Gardana, C., Del Bo, C., Quicazán, M. C., Corrrea, A. R. & Simonetti, P. Nutrients, phytochemicals and botanical origin of commercial bee pollen from different geographical areas. J. Food Compos. Anal. 29, 29–38 (2018).

Alaux, C., Ducloz, F., Crauser, D. & Le Conte, Y. Diet effects on honeybee immunocompetence. Biol. Lett. 6, 562–565 (2010).

Vanderplanck, M. et al. How does pollen chemistry impact development and feeding behaviour of polylectic bees?. PLoS ONE 9, 86209 (2014).

Moerman, R. et al. Growth rate of Bumblebee larvae is related to pollen amino acids. J. Econ. Entomol. 109, 25–30 (2016).

Pernal, S. F. & Currie, R. W. The influence of pollen quality on foraging behavior in honey bees (Apis mellifera L.). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 51, 53–68 (2001).

Vaudo, A. D., Patch, H. M., Mortensen, D. A., Tooker, J. F. & Grozinger, C. M. Macronutrient ratios in pollen shape bumblebee (Bombus impatiens) foraging strategies and floral preference. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 113, 4035–4042 (2016).

Donkersley, P. et al. Nutritional composition of honey bee food stores vary with floral composition. Oecologia 185, 749–761 (2017).

Mărgăoan, R. et al. Predominant and secondary pollen botanical origins influence the carotenoid and fatty acid profile in fresh honeybee-collected pollen. J. agricul. food chemist. 62, 6306–6316 (2014).

Oliveira, D. J. et al. Botanical origin, microbiological quality and physicochemical composition of the Melipona scutellaris pot-pollen (“samburá”) from Bahia (Brazil) Region. J. Apic. Res. 60, 457–469 (2020).

Alshallash, K. S. et al. Bee pollen as a functional product—Chemical constituents and nutritional properties. J. Ecol. Eng. 24, 173–183 (2023).

Souza, R. C. S., Yuyama, L. K. O., Aguiar, J. P. L. & Oliveira, F. P. M. Nutritional value of honey and pollen of stingless bees of the Amazonian region. Act. Amazon. 34, 333–336 (2004).

Barbieri, D. et al. Antioxidant, nutraceutical properties, and fluorescence spectral profles of bee pollen samples from different botanical origins. Antioxidants 9, 1001 (2020).

Araújo, J. S. et al. Chemical composition and biological activities of mono- and heterofloral bee pollen of different geographical origins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 921 (2017).

Kaškonienė, V., Ruočkuvienė, G., Kaškonas, P., Akuneca, I. & Maruška, A. Chemometric analysis of bee pollen based on volatile and phenolic compound compositions and antioxidant properties. Food Anal. Methods 8, 1150–1163 (2015).

Straumite, E., Bartule, M., Valdovska, A., Kruma, Z. & Galoburda, R. Physical and microbiological characteristics and antioxidant activity of honey bee pollen. Appl. Sci. 12, 3039 (2022).

Stevenson, P. C., Nicolson, S. & Wright, G. A. Plant secondary metabolites in nectar: Impacts on pollinators and ecological functions. Funct. Ecol. 31, 65–75 (2017).

Soares de Arruda, V. A. et al. Brazilian bee pollen: Phenolic content, antioxidant properties and antimicrobial activity. J. Apic. Res. 60, 775–783 (2020).

Pandey, K. B. & Rizvi, S. I. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid. Med. and Cell. Longev. 2, 270–278 (2009).

Arruda, D. E. et al. Microbiological quality and physicochemical characterization of Brazilian bee pollen. J. Apic. Res. 56, 231–238 (2017).

De-Melo, A. A. M., Estevinho, M. L. M. F. & Almeida-Muradian, L. B. A diagnosis of the microbiological quality of dehydrated bee-pollen produced in Brazil. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 61, 477–483 (2015).

Beev, G., Stratev, D., Vashin, I., Pavlov, D. & Dinkov, D. Quality assessment of bee pollen: A cross sectional survey in Bulgaria. J. Food Qual. Hazards Control. 5, 11–16 (2018).

Vargas-Abella, J. C., Tarazona-Manrique, L. E. & Andrade-Becerra, R. J. Microbiological characterization of dry and frozen pollen in Viracachá-Colombia. Rev MVZ Cordoba 25, 1854 (2020).

Anjos, O., Paula, V. B., Delgado, T. & Estevinho, L. M. Influence of the storage conditions on the quality of bee pollen. Zemdirbyste Agric. 106, 87–94 (2019).

De-Melo, A. A. M. et al. Effect of processing conditions on characteristics of dehydrated bee-pollen and correlation between quality parameters. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 65, 808–815 (2016).

Taha, E. K. A. A study on nectar and pollen sources for honeybee, Apis mellifera L. in Al-Ahsa Saudi Arabia. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 3, 272–277 (2015).

Conti, I. et al. Preliminary survey of the nutritional and palynological traits of honey bee foraged pollen from Liguria (Italy). J. Apic. Res. 57, 572–579 (2018).

Szczęsna, T. Study on the sugar composition of honeybee-collected pollen. J. Apic. Sci. 51, 15–22 (2007).

Nicolson, S. W. & Human, H. Chemical composition of the ‘low quality’pollen of sunflower (Helianthus annuus, Asteraceae). Apidologie 44, 144–152 (2013).

Lilek, N., Pereyra Gonzales, A., Božić, J., Kandolf Borovšek, A. & Bertoncelj, J. Chemical compositon and content of free tryptofan in Slovenian bee pollen. J. Food Nut. Res. 54, 323–333 (2015).

Velásquez, P. et al. Relation between composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities and botanical origin of multi-floral bee pollen. (2017).

Obistioiu, D. et al. Phytochemical profile and microbiological activity of some plants belonging to the Fabaceae family. Antibiotics 10, 662 (2021).

Jadhavar, P. & Deshpande, S. Recent updates on medicinal potentiality of Fabaceae family: Critical Review. Int J Pharm Sci. 13, 32–41 (2022).

Maroyi, A. Medicinal uses of the Fabaceae family in Zimbabwe: A review. Plants 12, 1255 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank the beekeepers for supplying bee pollen samples and sharing their insightful guidance. We gratefully thank Mr. Saeed Javadi in Central Laboratory of Shahid Beheshti University for his valuable helps in taking SEM images.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The Manuscript supervision: A. R. Mehrabian The Manuscript Idea: S.N.: Writing - original draft; Project administration; Data curationAR .M.: Supervision.H.M. : Analysis; Software.Z.S.: Formal analysis; Software.S.N., AR. M., H.M., Z.S.: Writing - review & editing; Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology. A. R. Mehrabian The Manuscript Edit: A. R. Mehrabian The manuscript Writing: Siavash Naghizdeh The Aanlysis: Hadi Maleki The manuscript analysis: Zahra Shakoori.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naghizadeh, S., Mehrabian, A., Maleki, H. et al. Botanical origin, chemical composition, and microbiological quality of bee pollen from Iran. Sci Rep 15, 44979 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28500-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28500-w