Abstract

Sepsis is frequently accompanied by severe metabolic disturbances and malnutrition, with nutritional status being an important modifiable factor affecting patient outcomes. The Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI) and the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) are multidimensional tools for assessing nutritional status. However, the association between PNI/GNRI and 60-day mortality in patients with sepsis remain inadequately elucidated. This study aimed to evaluate the value of PNI and GNRI for predicting the mortality risk in sepsis based on analysis of data from the MIMIC-IV database. A total of 1649 patients with sepsis were enrolled and stratified into tertiles of PNI and GNRI. We performed Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, multivariate Cox regression analysis, restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis, complemented by subgroup analyses stratified by age, comorbidities, and treatments. Patients in the PNI- and GNRI-Q3 groups (high-score groups) demonstrated a 53% reduction in 60-day mortality risk relative to those in the PNI- and GNRI-Q1 groups (low-score groups) [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.47, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.30–0.73]. RCS analysis revealed a nonlinear inverse correlation between PNI and mortality risk, with elevated mortality risk (HR > 1) observed at low scores of PNI (< 20). Subgroup analyses indicated that PNI exhibited more pronounced protective effects in patients aged ≤ 65 years (HR = 0.33) and those treated with β-lactam antibiotics (HR = 0.38). In contrast, GNRI showed better predictive value in elderly patients (> 65 years, HR = 0.61) and those with diabetes (HR = 0.37). Both PNI and GNRI are independent predictors of 60-day mortality in patients with sepsis. By integrating nutritional and immunological parameters, they provide valuable prognostic value beyond conventional measures. Incorporating PNI and GNRI into risk evaluation frameworks may help identify patients who may benefit from early nutritional interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory response syndrome triggered by infection. Its pathophysiological mechanisms are complex, involving immune dysregulation, metabolic disturbances, and multi-organ dysfunction. Globally, sepsis remains a major cause of mortality among patients in the intensive care unit (ICU)1. Epidemiological studies report approximately 49 million cases of sepsis globally each year. Of these, about 11 million deaths are attributable to sepsis or its complications, accounting for over 20% of total global mortality2. Despite advances in critical care, in-hospital mortality caused by sepsis still reaches 30%-40% in resource-abundant countries. Moreover, many survivors frequently suffer from long-term functional impairments and are at risk of rehospitalization3. Patient outcomes are strongly influenced by their baseline health conditions. In particular, malnutrition has gained increasing attention as a modifiable risk factor that may significantly affect prognosis4.

Malnutrition is highly prevalent among critically ill patients and is significantly associated with adverse outcomes. In sepsis, hypermetabolism markedly increases energy expenditure and accelerates protein catabolism. These metabolic disturbances, together with gastrointestinal dysfunction and insufficient nutritional intake, result in significant nutritional imbalances5. Research demonstrates that malnutrition impairs immune function, delays tissue repair, and exacerbates organ damage through mechanisms involving oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction6. Early identification of nutritional risk and timely intervention are therefore critical for improving the clinical outcomes of patients with sepsis. However, conventional nutritional assessment tools, such as body mass index (BMI) and serum albumin, have inherent limitations in the ICU settings. BMI does not accurately reflect acute changes in nutritional status, while serum albumin levels are easily influenced by inflammation and fluid resuscitation7. To address these limitations, multidimensional assessment tools have been developed. Among them, the Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI) and the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) have been increasingly adopted in critical care medicine.

The PNI is used for assessing nutritional and immune status by integrating serum albumin levels and peripheral lymphocyte counts8. It was originally developed to predict postoperative complications in gastrointestinal surgery but has since demonstrated broader applicability across diverse conditions, including cancer and chronic kidney disease9. In the ICU setting, for example, a retrospective study revealed that sepsis patients with low PNI scores had significantly higher mortality rates than those with high PNI scores10. The GNRI, specifically designed for elderly patients, can be used for the evaluation of nutritional risk using serum albumin levels and the ratio of actual to ideal body weight (IBW)11. Beyond identifying malnutrition, the GNRI has been validated as a predictor of infection risk and long-term survival among older populations. Research indicates that elderly inpatients with higher GNRI scores exhibit significantly lower mortality12. Despite these findings, comparative studies evaluating the predictive value of PNI and GNRI in patients with sepsis remain limited. In particular, their predictive value for 60-day mortality has yet to be clearly established.

Although previous studies have demonstrated a link between nutritional risk and sepsis outcomes, most have solely focused on short-term endpoints (e.g., 28-day mortality). In contrast, the evaluation of intermediate-term outcomes, including 60-day mortality, remains less studied. Such endpoints may better reflect the sustained effects of nutritional interventions. To address this gap, we sought to systematically evaluate the predictive value of PNI and GNRI for 60-day mortality in patients with sepsis through analysis of data from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) database. We hypothesized that both of them can serve as independent predictors of 60-day mortality in sepsis, and that their prognostic performance differs across patient subgroups. The current study aimed to provide evidence-based insights to enhance nutritional risk stratification and inform personalized management strategies in the clinical management of sepsis.

Materials and methods

Research data

The data analyzed in this study were collected from the MIMIC-IV database (v3.0), a large-scale, freely accessible database developed for research in emergency and intensive care medicine. This database contains de-identified clinical records from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (2008–2022). It provides comprehensive data on patient demographics characteristics, vital signs, laboratory measurements, surgical procedures, medication administrations, clinical severity scores, and survival outcomes13. Following the protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board, all protected health information in MIMIC-IV is fully de-identified, and patient identities are represented solely by randomly generated codes.

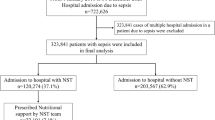

Research sample

The current study focused on adult patients with sepsis admitted to the ICU, as identified in the MIMIC-IV database. Sepsis was defined in accordance with the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock, characterized by suspected or documented infection and a total Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score of ≥ 2. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age ≥ 18 years; (2) first ICU admission (for patients with multiple ICU stays, only data from the initial admission were retained); and (3) ICU stay exceeding 24 h. Patients were excluded if key nutritional parameters were missing (specifically serum albumin levels, lymphocyte counts, height, or weight) or if they had a hospital stay longer than 60 days. The process of patient selection is detailed in Fig. 1.

Data extraction

Data were extracted using PostgreSQL (v17.3.1) through structured query language operations. The study accounted for potential confounders across five domains: (1) baseline demographics: age, gender, race, and marital status; (2) comorbidities: hypertension, diabetes, congestive heart failure (CHF), myocardial infarction, and cerebrovascular disease; (3) treatments: administration of antibiotics, glucocorticoids, and dopamine; (4) laboratory parameters: white blood cells (WBC), red blood cells (RBC), red cell distribution width (RDW), hemoglobin, platelets, international normalized ratio (INR), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), oxygen saturation (SPO₂), temperature, lymphocytes, neutrophils, hemoglobin oxygen saturation (SO₂), partial pressure of oxygen (PO₂), and partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO₂); and (5) severity scores: acute physiology score III (APS III) and simplified acute physiology score II (SAPS II).

Calculation of nutritional indices

The PNI was calculated using the following formula: PNI = 10 × serum albumin (g/dL) + 0.005 × total peripheral lymphocyte count (/mm³)8,14. Actual body weight (ABW) was measured directly, while IBW was estimated using the Lorentz formula. For men, IBW = height (cm) − 100 − [(height − 150)/4]. For women, IBW = height (cm) − 100 − [(height − 150)/2.5]. The GNRI was calculated according to the formula proposed by Bouillanne et al.: GNRI = 1.489 × serum albumin (g/dL) × 10 + 41.7 × (ABW/IBW)11. The primary outcome of this study was 60-day mortality, determined based on the death records recorded in the MIMIC-IV database.

Statistical analysis

Participants were categorized into three groups (Q1-Q3) according to tertiles of PNI and GNRI. The PNI groups were defined as follows: Q1 (n = 550, PNI ≤ 30), Q2 (n = 549, 30 < PNI ≤ 37.7), and Q3 (n = 550, PNI > 37.7).The GNRI groups were similarly categorized as Q1 (n = 550, GNRI ≤ 95.5), Q2 (n = 549, 95.5 < GNRI ≤ 111.9), and Q3 (n = 550, GNRI > 111.9). Categorical variables were presented as percentages, and between-group comparisons were performed using the chi-square test. Continuous variables were tested for normality and expressed as medians with interquartile ranges, with group comparisons conducted using non-parametric rank-sum tests. Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) to evaluate PNI and GNRI as risk factors for the outcome event, with Q1 serving as the reference group. Prior to multivariate modeling, multicollinearity among covariates was assessed using variance inflation factors and no significant collinearity that would compromise model stability was found. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by stratifying patients into quartiles of PNI and GNRI values to evaluate the robustness of the findings. In the multivariate Cox regression models, age, gender, race, marital status, WBC, RBC, RDW, hemoglobin, platelet count, INR, PTT, SPO₂, temperature, lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, SO₂, PO₂, PCO₂, APSIII, SAPSII, hypertension, diabetes, myocardial infarction, CHF, cerebrovascular disease, as well as the use of antibiotics, glucocorticoids, and dopamine were included as confounding factors, and trend tests were performed. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis based on the tertiles of PNI and GNRI, and the log-rank test were used to evaluate differences between groups. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis was conducted to explore the association between PNI and GNRI and the outcome events.

Results

Comparison of patient baseline characteristics based on PNI and GNRI tertiles

A total of 1649 patients with sepsis were included in the analysis and they were stratified into low- (Q1), medium- (Q2), and high-score (Q3) groups based on tertiles of the PNI and GNRI, respectively. Patients in the PNI- and GNRI-Q3 groups generally had better nutritional and hematologic profiles, with higher lymphocyte counts as well as higher albumin and hemoglobin levels), In contrast, patients in the PNI- and GNRI-Q1 groups demonstrated more severe inflammation and greater disease severity, as reflected by higher neutrophil counts as well as higher APSIII and SAPSII scores.

Regarding demographic characteristics, a higher proportion of males was observed in the PNI-Q3 group (PNI-Q3: 64.36% vs. GNRI-Q3: 57.45%), while a larger percentage of elderly patients (> 65 years) was found in the GNRI-Q1 group (GNRI-Q1: 50.91% vs. PNI-Q1: 47.82%). Analysis of comorbidities indicated that hypertension was most prevalent in both the PNI- and GNRI-Q3 groups (PNI-Q3: 60.36% vs. GNRI-Q3: 60.73%, p < 0.0001), and diabetes was more commonly observed in the GNRI-Q3 group (GNRI-Q3: 23.09% vs. PNI-Q3: 19.27%). In terms of different treatments, β-lactam antibiotics was used more frequently in patients in the PNI-Q1 group (PNI-Q1: 15.27% vs. GNRI-Q1: 14.18%), whereas other antibiotics were more frequently administered in patients in the GNRI-Q3 group (GNRI-Q3: 63.27% vs. PNI-Q3: 64.36%) (Tables 1 and 2).

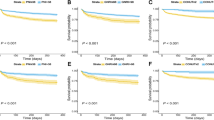

Kaplan-Meier analysis of PNI/GNRI and in-hospital mortality

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to compare 60-day survival among different nutritional scoring groups (PNI vs. GNRI) (Fig. 2). Statistically significant differences in survival rates were observed among the PNI-stratified groups (log-rank test, P < 0.0001; Fig. 2A), with patients in the PNI-Q3 group showing markedly higher survival probability compared to those in the PNI-Q1 group. Similarly, significant differences in survival were also observed among GNRI-stratified groups (log-rank test, P = 0.0089; Fig. 2B), with patients in the GNRI-Q3 group showing better survival outcomes relative to the those in the GNRI-Q1 group. Divergence in survival curves emerged within the first 10 days following ICU admission. At day 60, the survival probability in the PNI-Q3 group was approximately 25% higher than that in the PNI-Q1 group. A similar pattern was observed for GNRI, where patients in the GNRI-Q3 group had a 15–20% higher survival probability compared with those in the GNRI-Q1 group (Fig. 2).

Association between PNI/GNRI and outcome events

Multivariable Cox regression analysis demonstrated a significant association between nutritional scores (PNI and GNRI) and in-hospital mortality among patients with sepsis (Tables 3 and 4). Using the low-score group (Q1) as the reference, the unadjusted Model 1 demonstrated that patients in the PNI-Q3 group had the lowest mortality risk (HR = 0.39, 95% CI: 0.29–0.52, p < 0.001), while those in the GNRI-Q3 group showed a significantly reduced mortality risk compare to Q1 (HR = 0.67, 95% CI: 0.52–0.87, p = 0.003). After adjusting for demographic variables including age, gender, marital status, and race in Model 2, the protective effects of high nutritional scores remained significant for both PNI-Q3 (HR = 0.43, 95% CI: 0.32–0.58, p < 0.001) and GNRI-Q3 groups (HR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.56–0.96, p = 0.022). Further adjustment for laboratory parameters, disease severity scores, and comorbidities in Model 3 yielded similar results (PNI-Q3: HR = 0.47, 95% CI: 0.30–0.73, p = 0.001; GNRI-Q3: HR = 0.47, 95% CI: 0.30–0.73, p = 0.001), suggesting independent predictive value of both PNI and GNRI for in-hospital mortality. Notably, the PNI-Q2 group did not retain statistical significance in the fully adjusted model (HR = 0.76, 95% CI: 0.54–1.07, p = 0.119), and a similar trend was observed for the GNRI-Q2 group (HR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.41–0.90, p = 0.014).

Furthermore, sensitivity analyses based on quartile-based stratification (Table S1, Table S2) demonstrated that patients in the PNI-Q4 and GNRI-Q4 groups (with the highest nutritional scores) had even further reduced mortality risk compared to those in the PNI-Q1 and GNRI-Q1 groups (PNI-Q4: HR = 0.63, p < 0.001; GNRI-Q4: HR = 0.63, p = 0.003). These findings were consistent with the primary analysis, reinforcing the association between nutritional status and in-hospital outcomes. In the multivariable Cox models, high PNI scores (Q3) were associated with a 47% reduction in 60-day mortality (HR = 0.47, 95% CI: 0.30–0.73), and high GNRI scores conferred a comparable survival benefit (HR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.41–0.90, p = 0.014). The findings persisted after full adjustment, underscoring the independent prognostic value of both indices. By contrast, medium PNI and GNRI scores (Q2) did not retain significance, suggesting that only marked improvements in nutritional status are associated with meaningful survival benefits.

Dose-response relationship between nutritional scores and mortality risk

Through RCS analysis, we further examined the dose-response relationship between nutritional scores (PNI and GNRI) and in-hospital mortality risk among patients with sepsis. For PNI (Fig. 3A–C), Model 1 (unadjusted) revealed a significant nonlinear inverse association between PNI and mortality risk (overall P < 0.001, nonlinear P = 0.019). The risk of mortality (HR > 1.5) rose sharply at low PNI scores (< 20), but stabilized (HR ≈ 0.5) at higher PNI scores (> 20). After adjustment for demographic variables (Model 2), the nonlinear trend weakened but approached significance (nonlinear P = 0.058). In the fully adjusted model (Model 3), the evidence for a nonlinear relationship was no longer observed (nonlinear P = 0.183), suggesting that other confounding factors may partially mediate such association. For GNRI (Fig. 4A–C), Model 1 showed an overall linear inverse association between GNRI and mortality risk (overall P = 0.024), without evidence of significant nonlinearity (P = 0.597). GNRI’s linear protective effect lost statistical significance in Model 3 (overall P > 0.05), though mortality risk (HR ≈ 0.6) consistently decreased with high GNRI scores (> 80). The lack of significance may reflect partial mediation by confounders. However, when analyzed categorically, higher GNRI scores continued to be associated with a significantly lower risk of mortality (Table 4), supporting the value of this index in clinical risk stratification.

RCS curves demonstrated a sharp increase in mortality risk at PNI levels below 20, followed by a plateau around 30, with risk remaining stable at higher levels, this pattern indicates a threshold effect, whereby patients with PNI below 20 are at particularly high risk of mortality. In contrast, GNRI showed a close-to-linear protective pattern, suggesting gradual survival benefit with increasing scores.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses demonstrated heterogeneous protective effects of PNI and GNRI on in-hospital mortality across different patient populations. For PNI (Table 5), high PNI scores (Q3) conferred a significantly greater mortality reduction in younger patients (≤ 65 years, HR = 0.33) than in elderly patients (HR = 0.46, p < 0.001), with particularly pronounced effects in patients without diabetes (HR = 0.41, p < 0.001) and those treated with β-lactam antibiotics (HR = 0.38, p = 0.008; interaction P = 0.023). Comparable trends were observed in White patients (HR = 0.42, p < 0.001) and in those without cerebrovascular disease (HR = 0.39, p < 0.001).

Regarding GNRI (Table 6), significant protective effects was observed in elderly patients (> 65 years, HR = 0.61, p = 0.017), patients with diabetes (HR = 0.37, p = 0.003; interaction P = 0.049), and those treated with non-β-lactam antibiotics (HR = 0.56, p = 0.002). Notably, among different racial groups, Black patients exhibited the greatest mortality reduction with high GNRI scores (HR = 0.18, p = 0.025), while the association in White patients showed borderline significance (HR = 0.72, p = 0.066). Additionally, GNRI demonstrated stronger protective trends in patients with CHF (HR = 0.42, p = 0.002).

Both PNI and GNRI were consistently linked to lower mortality in certain subgroups (e.g., males and patients without myocardial infarction). However, PNI demonstrated superior predictive value in younger patients and specific treatment subgroups, whereas GNRI provided more robust risk stratification among elderly patients and patients with diabetes.

Discussion

Sepsis is a systemic inflammatory syndrome caused by a dysregulated host response to infection, frequently leading to multiple organ dysfunction and high mortality. Emerging evidence has highlighted nutritional status as a key modifiable factor influencing outcomes in patients with sepsis. By analyzing data from the MIMIC-IV database, this study comprehensively evaluated the association between PNI/GNRI and 60-day mortality in patients with sepsis, while concurrently examining their heterogeneous effects across different subgroups. This discussion focused on three key aspects: the clinical implications of the findings, the potential underlying biological mechanisms, and the consistency of our results with existing literature.

Our findings are consistent with prior reports linking poor nutritional status to adverse outcomes in sepsis and other severe critical conditions. Hypoalbuminemia and lymphopenia are the main components of PNI and has been reported to reflect both malnutrition and systemic inflammation, which are known contributors to worse outcomes in sepsis. Likewise, GNRI, which incorporates serum albumin and body weight, has been validated as a simple yet effective measure of nutritional risk in hospitalized patients. Importantly, the current study extends existing knowledge by confirming the independent prognostic value of both PNI and GNRI in a large cohort of patients with sepsis in the ICU setting.

This study identified both PNI and GNRI as significant independent predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients with sepsis. Multivariable Cox regression analysis revealed that patients in the high-score PNI group (Q3) exhibited a 53% reduction in mortality risk compared to those in the low-score PIN group (Q1).A similar risk reduction was also observed in the high-score GNRI group (Q3). These results align with previous research by Bouillanne et al., which confirmed the value of GNRI in assessing nutritional risk and predicting mortality in elderly populations, as it integrates the evaluation of both albumin levels and body weight parameters11. PNI is a composite immunonutritional marker incorporating albumin level and lymphocyte count. It not only reflects energy reserves but may also influence sepsis outcomes through its role in immune regulation within the hypermetabolic state of sepsis. Notably, lymphopenia, a key component of PNI, correlates with immunosuppression and impaired pathogen clearance15. Albumin, shared by both PNI and GNRI, plays a crucial part beyond nutritional assessment. Its ability to maintain colloid osmotic pressure and provide antioxidant effects may mitigate sepsis-induced capillary leakage and organ damage16. RCS analysis revealed a nonlinear dose-response relationship between nutritional scores and mortality, highlighting two critical findings. First, patients with PNI < 20 exhibited persistently high mortality risk (HR > 1.5), which reached a relatively stable level at PNI > 30 (HR ≈ 0.5). Second, these threshold effects emphasize the clinical imperative for early nutritional interventions. Strategies such as enteral nutrition supplemented with immunonutrients like ω-3 fatty acids may disrupt the malnutrition-inflammation cycle in patients with low-PNI/GNRI. This could reduce inflammatory mediator release, preserve intestinal barrier function, and ultimately decrease the risk of organ failure17,18.

Subgroup analyses revealed significant heterogeneity in the protective effects of both PNI and GNRI across different patient populations. The PNI was strongly linked to lower mortality in younger patients (≤ 65 years, HR = 0.33) and in those treated with β-lactam antibiotics (HR = 0.38). These observations may be attributed to the greater metabolic resilience typically observed in younger individuals and the efficacy of β-lactam antibiotics in targeting Gram-negative bacterial infections19,20. In contrast, GNRI was associated with more pronounced risk reduction trends in elderly patients (> 65 years, HR = 0.61) and in patients with diabetes (HR = 0.37). The GNRI’s formula incorporates a weight adjustment formula based on IBW calculated from height, enhances its suitability for nutritional assessment in elderly populations, especially in the context of age-related conditions such as sarcopenia and chronic disease-related wasting11,21. Notably, differences were also observed among different racial groups. High GNRI scores were associated with the greatest reduction in mortality among Black patients, whereas the protective effect was not statistically significant in White patients. These differences may be influenced by genetic factors (e.g., albumin metabolic rate) or by disparities in access to healthcare resources. For instance, African Americans are more likely to experience delayed access to medical care due to socioeconomic factors, which can lead to severely compromised nutritional status by the time infections progress to sepsis3. Overall, these findings underscore the importance of developing individualized nutritional support strategies that account for population-specific characteristics in clinical practice.

The association between nutritional scores and sepsis outcomes may be mediated through several mechanisms: (1) Immunomodulation: the lymphocyte count in PNI directly reflects immune function. In the early stages of sepsis, excessive inflammatory responses induce lymphocyte apoptosis, while nutritional interventions (e.g., arginine and glutamine) promotes lymphocyte proliferation and enhances pathogen clearance22; (2) Metabolic support: albumin not only serves as a marker of nutritional status but also plays active roles in binding endotoxins, reducing oxidative stress, and maintaining vascular endothelial integrity, thereby lowering the risk of capillary leakage23; (3) Inflammation suppression: patients with higher nutritional scores tend to have lower neutrophil counts and APSIII scores, indicating milder systemic inflammation. Experiments through animal models demonstrate that adequate protein intake suppresses NF-κB pathway activation, thereby reducing the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α and IL-6)24,25; (4) Organ-specific protection: GNRI shows stronger protective effects in patients with CHF. Nutritional interventions may improve myocardial energy metabolism (e.g., enhanced fatty acid oxidation) and attenuate oxidative stress-related cardiomyocyte apoptosis26. Additionally, higher platelet counts observed in patients with high GNRI scores may facilitate microcirculatory repair, thereby mitigating ischemic organ injury27.

Conventional nutritional assessment tools (e.g., BMI and serum prealbumin) have notable limitations in the ICU settings. BMI cannot reliably distinguish between acute malnutrition and chronic wasting disorders. Similarly, serum prealbumin, with its short half-life (2–3 days) and susceptibility to suppression by inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6), may not accurately reflect true nutritional status28. In contrast, PNI and GNRI represent a more robust evaluation framework by incorporating multidimensional parameters (e.g., albumin level, lymphocyte count, and body weight).

This study demonstrated that both PNI and GNRI significantly outperformed individual nutritional markers (e.g., albumin or lymphocyte count alone) in predicting mortality risk. Their predictive value remained statistically significant even after full adjustment for potential confounders. These findings underscore the utility of PNI and GNRI for risk stratification in patients with sepsis.

The hypermetabolic state in sepsis accelerates protein catabolism and promotes negative nitrogen balance, thereby exacerbating malnutrition. In this study, patients with low PNI scores exhibited significantly elevated neutrophil counts, suggesting a vicious cycle between malnutrition and excessive inflammatory responses. Experimental studies in mice with sepsis have demonstrated that branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) deficiency aggravates inflammatory cascades and multi-organ damage, while BCAA supplementation reduces TNF-α release by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway29. Furthermore, patients with high GNRI scores have higher hemoglobin levels, which may potentially enhance oxygen delivery efficiency to mitigate mitochondrial dysfunction and reduce organ failure risk from tissue hypoxia30. These findings highlight the central role of the “nutrition-immunity-metabolism” axis in the pathophysiology of sepsis. It is expected that combined nutritional support with targeted immunomodulation (e.g., IL-7 receptor agonists) can be evaluated in future investigations, so as to interrupt the mutual deterioration between malnutrition and inflammation.

In summary, PNI and GNRI were identified as robust prognostic indicators for patients with sepsis. By integrating multidimensional physiological parameters, these indices provide an assessment that overcomes the limitations of conventional nutritional assessment tools. However, patient heterogeneity (e.g., age, comorbidities, and treatments) may influence their clinical applicability. For example, liver disease, which may affect albumin synthesis and thus influence nutritional indices, was not included in the final model due to its high collinearity with serum albumin. While this approach preserved model stability, residual confounding from liver disease cannot be entirely excluded. Furthermore, albumin levels in critically ill patients may be influenced by factors such as capillary leakage, fluid resuscitation, and dilutional effects, which may limit its reliability as a nutritional marker. Future studies should validate the prognostic significance of dynamic changes in PNI/GNRI and assess their combined use with inflammatory/metabolic markers. Although PNI and GNRI are not fully aligned with consensus diagnostic criteria for malnutrition, such as the GLIM framework, they provide an integrated assessment by combining immune-inflammatory status with anthropometric measures. Their prognostic value is warranted to be validated by linking them with muscle mass markers or direct body composition assessments. Clinically, we recommend integrating PNI and GNRI into personalized nutritional interventions (e.g., immunonutrient supplementation for patients with low PNI scores or metabolic support strategies for patients with high GNRI scores). Such targeted approaches may enhance sepsis management and improve long-term outcomes.

Although the MIMIC-IV database includes a comprehensive set of clinical indicators, certain nutrition-related variables are lacking (e.g., details of dietary intake and direct measurements of muscle mass). In addition, information on socioeconomic status or long-term nutritional interventions is not captured, both of which may indirectly influence patient prognosis. Moreover, as data in the MIMIC-IV database primarily reflects U.S. healthcare settings, population characteristics (e.g., racial composition and access to healthcare resources) may limit the generalizability of these findings to other regions. For example, while GNRI demonstrated a significant protective effect in Black patients, this observation warrants validation in different healthcare systems and patient populations.

Conclusion

Both PNI and GNRI can serve as independent predictors of 60-day mortality in patients with sepsis. Higher nutritional scores are indicative of a lower risk of death, and this association showed heterogeneity across subgroups defined by age, comorbidities, and treatments. Clinically, the incorporation of PNI and GNRI into the early assessment of sepsis can help identify high-risk patients and guide targeted nutritional interventions to improve organ function and reduce mortality. Future research should integrate dynamic nutritional monitoring with multi-omics techniques to further elucidate the regulatory mechanisms of the nutrition-immunity-metabolism axis, so as to optimize individualized management strategies for patients with sepsis.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the MIMIC-IV database ( v3.0) at physionet.org).

Abbreviations

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- PNI:

-

Prognostic Nutritional Index

- GNRI:

-

Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index

- IBW:

-

Ideal body weight

- MIMIC-IV:

-

Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV

- CHF:

-

Congestive heart failure

- WBC:

-

White blood cells

- RBC:

-

Red blood cells

- RDW:

-

Red cell distribution width

- INR:

-

International normalized ratio

- PTT:

-

Partial thromboplastin time

- SPO₂:

-

Oxygen saturation

- SO₂:

-

Hemoglobin oxygen saturation

- PO₂:

-

Partial pressure of oxygen

- PCO₂:

-

Partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- APS III:

-

Acute physiology score III

- SAPS II:

-

Simplified acute physiology score II

- ABW:

-

Actual body weight

- HRs:

-

Hazard ratios

- RCS:

-

Restricted cubic spline

- BCAA:

-

Branched-chain amino acid

References

Shankar-Hari, M. et al. Developing a new definition and assessing new clinical criteria for septic shock: for the third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). Jama 315 (8), 775–787 (2016).

Global regional, and National incidence and mortality burden of non-COVID-19 lower respiratory infections and aetiologies, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24 (9), 974–1002 (2024).

Fleischmann-Struzek, C. & Rudd, K. Challenges of assessing the burden of sepsis. Med. Klin. Intensivmed Notfmed. 118 (Suppl 2), 68–74 (2023).

De Waele, E., Malbrain, M. & Spapen, H. Nutrition in sepsis: A Bench-to-Bedside review. Nutrients 12 (2), 395 (2020).

Englert, J. A. & Rogers, A. J. Metabolism, metabolomics, and nutritional support of patients with sepsis. Clin. Chest Med. 37 (2), 321–331 (2016).

Hill, A., Elke, G. & Weimann, A. Nutrition in the intensive care unit-a narrative review. Nutrients 13 (8), 2851 (2021).

Reintam Blaser, A. et al. Early enteral nutrition in critically ill patients: ESICM clinical practice guidelines. Intensive Care Med. 43 (3), 380–398 (2017).

Wu, H., Zhou, C., Kong, W., Zhang, Y. & Pan, D. Prognostic nutrition index is associated with the all-cause mortality in sepsis patients: a retrospective cohort study. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 36 (4), e24297 (2022).

Man, Z. et al. Prognostic significance of preoperative prognostic nutritional index in hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford). 20 (10), 888–895 (2018).

Li, T. et al. Clinical value of prognostic nutritional index in prediction of the presence and severity of neonatal sepsis. J. Inflamm. Res. 14, 7181–7190 (2021).

Bouillanne, O. et al. Geriatric nutritional risk index: a new index for evaluating at-risk elderly medical patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 82 (4), 777–783 (2005).

Jin, Y., Zhou, T., Hou, C., Zhang, H. & Xu, B. Relationship between the geriatric nutritional risk index and sepsis in elderly critically ill patients: a retrospective cohort study. Eur. J. Med. Res. 30 (1), 130 (2025).

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. Author correction: MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data. 10 (1), 219 (2023).

Ni, L. et al. Prognostic nutritional index predicts response and prognosis in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 9, 823087 (2022).

Singer, M. et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). Jama 315 (8), 801–810 (2016).

Vincent, J. L., De Backer, D. & Wiedermann, C. J. Fluid management in sepsis: the potential beneficial effects of albumin. J. Crit. Care. 35, 161–167 (2016).

McClave, S. A. et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: society of critical care medicine (SCCM) and American society for parenteral and enteral nutrition (A.S.P.E.N). JPEN J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 40 (2), 159–211 (2016).

Singer, P. et al. Enteral and supplemental parenteral nutrition enriched with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in intensive care patients—a randomized, controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 40 (5), 2544–2554 (2021).

Hsu, A. J., Chiotos, K., Heil, E. L., Shields, R. K. & Tamma, P. D. The effectiveness of newer Beta-Lactams for the treatment of Antimicrobial-Resistant Gram-Negative meningitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 959–968 (2025).

Rudd, K. E. et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet 395 (10219), 200–211 (2020).

Ueshima, J. et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment and Nutrition-Related assessment: a Cross-Sectional survey for health professionals. Geriatr. (Basel) 4 (1), 23 (2019).

Cao, C., Yu, M. & Chai, Y. Pathological alteration and therapeutic implications of sepsis-induced immune cell apoptosis. Cell. Death Dis. 10 (10), 782 (2019).

Keller, U. Nutritional laboratory markers in malnutrition. J. Clin. Med. 8 (6), 775 (2019).

Chen, L. et al. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 9 (6), 7204–7218 (2018).

Herrero-Cervera, A., Soehnlein, O. & Kenne, E. Neutrophils in chronic inflammatory diseases. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 19 (2), 177–191 (2022).

Lim, G. B. Inhibiting fatty acid oxidation promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 17 (5), 266–267 (2020).

Wiśniewski, A. et al. High On-Treatment platelet reactivity affects the extent of ischemic lesions in stroke patients due to Large-Vessel disease. J. Clin. Med. 9 (1), 251 (2020).

Evans, D. C. et al. The use of visceral proteins as nutrition markers: an ASPEN position paper. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 36 (1), 22–28 (2021).

Liang, S., Li, Y., Liu, H. & Wang, B. Pre-operative prognostic nutritional index was associated with recurrence after surgery in giant cell tumor of bone patients. J. Bone Oncol. 25, 100324 (2020).

Tohyama, M. et al. Predictive value of the Hemoglobin-Geriatric nutritional risk index in patients with heart failure. Nutrients 15 (22), 4789 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Project of Hangzhou Health Science and Technology Plan (ZD20230017), the Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Health Science and Technology Project (2022KY241), the Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Health Technology Project (2023RC226), and the Zhejiang Provincial Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project (2023ZR121).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Jinyan Fang and Jinyu Huang; Data curation, Xue Zhao; Formal analysis, Yuanhan Lin; Investigation, Linjun Zhao; Methodology, Jinyan Fang; Writing – original draft, Jinyan Fang; Writing – review & editing, Jinyu Huang.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The MIMIC-IV database has obtained approval from the Institutional Review Boards of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Informed consent from patients was not required as all protected private information was removed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, J., Lin, Y., Zhao, L. et al. Prognostic nutritional indices predict 60 day mortality in ICU patients with sepsis. Sci Rep 15, 45733 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28609-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28609-y