Abstract

The phenomenon of overqualification is widespread and profoundly impacts employees’ work attitudes. While existing studies have explored overqualification, limited research has focused on the effects of peer overqualification on employees’ dualistic work passion through affective and cognitive mechanisms. Grounded in the theoretical framework of conservation of resource theory as well as cognitive-affective processing system theory, this study examines the relationship between peer overqualification and the production of employees’ dualistic work passion. It analyzes the mediating role of a perceived competitive climate and job anxiety. Utilizing a sample of 532 employees from China, this study finds that peer overqualification stimulates employees’ obsessive work passion and negatively impacts their harmonious work passion. Perceived competitive climate and job anxiety play a chain mediation role in the positive relationship between peer overqualification and obsessive work passion and the negative relationship between peer overqualification and harmonious work passion. This study broadens the theoretical perspectives on peer overqualification, enriches research on the determinants of dualistic work passion, and offers managerial implications for enhancing employees’ work passion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the popularization of higher education, the increase of highly educated talents, and the intensification of competition in the labor market, enterprises that “choose the best among the best” and promote job seekers are trapped in the “internal volume” dilemma. Overqualification can be seen as a concrete phenomenon of “internal volume”1. According to the Global Press Report, approximately 47% of employees globally feel overqualified, while 84% of employees in China feel overqualified and underutilized2. However, in the post-epidemic era, the development speed of enterprises has slowed, and demand in the labor market has declined. As a result, college graduates are experiencing “downward employment” and lack passion for their work, which makes the phenomenon of “overqualification” more prominent3.

The phenomenon where employees’ educational background, work experience, knowledge, and skills exceed the job demand is called “overqualification” and has become a research hotspot in organizational behavior4,5. And the belief that an individual’s skills, experience, or abilities exceed the requirements of their current job is called perceived overqualification5,6. Existing research on perceived overqualification primarily focuses on exploring the positive and negative effects on employees’ perceptions of “overuse” and “lack of talent”4. For example, perceived overqualification promotes innovation performance7, career adaptability8 and work performance9, but may also lead to turnover behaviors10, withdrawal behaviors11,cyberloafing12, and internet burnout13. However, another phenomenon, peer overqualification, has received relatively less attention in the literature but is gradually becoming a topic of interest14.

Peer overqualification refers to the perception that an employee’s peers possess greater qualifications or capabilities than are required by their current roles14,15. This phenomenon, which involves comparisons between individuals within a workplace, has significant implications for work dynamics. For example, Zhang et al.14 studied the interactive effect of perceived overqualification and peer overqualification on peer ostracism and work meaningfulness14,15, while Hu et al.16 examined how peer overqualification affects task importance, perceived fit, and the performance of overqualified employees16.

Work passion is a strong emotional inclination in individuals to internalize work motivation as a form of identity recognition and to invest time and energy in their work17. The autonomous internalization process fosters a harmonious work passion, whereas the controlled internalization process promotes an obsessive work passion17. The dualistic model of passion explicitly incorporates affective, cognitive, and behavioral components18. Specifically, it conceptualizes the construct as a tendency toward an activity that people like (i.e., the affective component), that they find important and identify with (i.e., the cognitive component), and in which they invest substantial time and energy (i.e., the behavioral component)19. When they perceive peer overqualification, employees may adopt a positive or negative attitude towards investing a significant amount of time and energy in their work and then internalize either a harmonious or obsessive work passion. Work passion plays a crucial role in the realization of individual value and the motivation of innovative activities20. However, prolonged exposure to peer overqualification within the internal environment can physically and mentally weaken employees, frustrate their passion for work, and even lead to destructive behavior21. Therefore, it is of great significance to study the working mechanism of peer overqualification on employees’ dualistic work passion. Accordingly, this study aims to address the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1: How does peer overqualification affect employees’ harmonious and obsessive work passion?

RQ2: How does peer overqualification influence employees’ dualistic work passion through cognitive and emotional mechanisms?

RQ3: How can employees who perceive their peers as overqualified derive value from their own work?

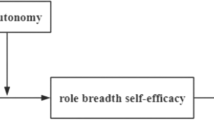

To analyze the differential influence paths of peer overqualification on employees’ dualistic work passion, this study constructs an integrated theoretical framework based on the conservation of resources theory (COR theory) and the cognitive-affective processing system theory (CAPS theory). Specifically, from the dynamic perspective of resource maintenance, the COR theory enhances the understanding of the interaction mechanism between situational factors (such as peer overqualification) and individual resources in organizational contexts. Resource depletion is identified as the direct mechanism leading to the generation of obsessive work passion and the inhibition of harmonious work passion22,23. Accordingly, this study identifies two key resources, i.e., relational resources and emotional resources24, with perceived competitive climate and job anxiety introduced as mediating variables. From the perspective of relational resources, peers serve as a source of work information. According to the COR theory, overqualified peers possessing knowledge, skills, and experience that exceed job requirements are more likely to acquire new resources and promotion opportunities, which makes employees perceive intense competitive climates, thereby inhibiting harmonious work passion while stimulating obsessive passion15,22. Meanwhile, through the emotional resources, peer overqualification makes employees aware of their disadvantage in resource acquisition, leading to high work pressure and job anxiety25. According to the COR theory’s resource spiral effect, anxiety essentially manifests as a continuous depletion of emotional resources. That is, when individuals perceive their inability to replenish resources through effort (e.g., hopelessness about promotion prospects), anxiety intensifies23,26. Consequently, when employees work with overqualified peers, they would experience job anxiety and other negative emotions due to their resource scarcity and competitive pressure, ultimately developing obsessive work passion while inhibiting the formation of harmonious work passion.

Building on the CAPS theory, external situations activate an individual’s cognitive-affective unit network, forming a dynamic pathway of “situational stimulus – cognitive appraisal – affective response – behavioral outcome”24,27. So, this study incorporates perceived competitive climate (a cognitive unit) and job anxiety (an affective unit) as sequential mediators to examine their chained mediating effects between peer overqualification and dualistic work passion. When peer behaviors primarily shape an individual’s situational context, their responses to this environment will be influenced by the peer-activated CAPS network28. Perceived competitive climate describes how individuals view the allocation of organizational rewards, such as promotions, training opportunities, and bonuses29. These rewards are seen as dependent on how an individual’s work performance compares to that of their peers29. Employees who perceive a highly competitive climate often view their work performance as a key determinant of these rewards as well. Overqualified employees, in particular, may feel entitled to better positions, seeing themselves as superior to their peers and sometimes even taking on informal leadership roles within the team30. In contrast, employees who work alongside highly overqualified peers may experience feelings of rejection and anxiety, as they perceive their resources and opportunities to be more limited. This perception of competition, activated by overqualified peers, can significantly shape an individual’s sense of job anxiety. In other words, employees’ perceived competitive climate can be seen as a cognitive unit activated by peer overqualification.

McCarthy et al.31 describe job anxiety as the emotional stress experienced when individuals feel threatened by potential risks or challenges31. Overqualified peers often receive richer individual and work resources, which in turn leads to resource gains22. On the contrary, other employees often find it difficult to access work resources, leading to resource defense and job anxiety22. Job anxiety can be seen as an affective activated by perceived competitive climate. Specifically, in work environments where peers possess superior competencies and resource dominance, employees’ relative resource scarcity generates perceived competitive pressure, which becomes progressively reinforced through sustained exposure to competitive climate experiences, thereby elevating job anxiety levels32. Ultimately, this process facilitates the activation of obsessive work passion while simultaneously suppressing the development of harmonious work passion28. Therefore, drawing on a dual cognitive-affective perspective, we propose that perceived competitive climate and job anxiety form a chain mediation mechanism to promote employees’ dualistic work passion. Figure 1 shows the theoretical model of this study.

Theory and hypotheses

Peer overqualification and dualistic work passion

Previous studies have demonstrated that economic factors, organizational factors33, and personal traits34 all influence the phenomenon of overqualification. Zhang et al.15 define peer overqualification as the average overqualification level of one’s peers15. This study defines peer overqualification as the degree to which employees perceive that their peers’ educational background, information, skills, and abilities exceed the requirements of their current positions within an organizational context.

Vallerand et al.17 define passion as an individual’s strong inclination towards activities that they enjoy and consider important and in which they voluntarily invest time and energy to internalize as part of their self-identity17. The dualistic model of work passion suggests that the autonomous internalization process leads to harmonious work passion, whereas the controlled internalization process fosters obsessive work passion35. Peers play a significant role in influencing internalization. Harmonious work passion means that employees genuinely love their work, are willing to devote themselves to it, and have some autonomy and flexibility in their roles19. In contrast, obsessive work passion means an employee is forced to do the work.

Studies on the antecedents of dualistic work passion in the existing literature primarily focus on certain personal and organizational factors. Personal factors include self-esteem36, personality traits37, controllable perception38, control points39, goal-pursuit orientation40, and others. Lafrenière et al. (2011) explored the significant positive relationship between explicit self-esteem levels and harmonious passion, indicating that implicit self-esteem levels are related to obsessive passion36. Vergauwe et al. (2022) found that both the Big Five personality traits and maladaptive personality traits are related to harmonious and compulsive passion in work37. Organizational factors are studied in terms of aspect such as organizational climate and leadership style, including the autonomy-supportive environment, organizational diversity atmosphere, and the psychological climate of organizational cooperation41, which contribute to generating employees’ harmonious passion. New evidence suggests that the high work requirements perceived by employees not only positively predict employees’ obsessive work passion, but also weaken their harmonious work passion42. In terms of leadership style, some studies have shown that the leaders’ harmonious work passion promotes the harmonious work passion of employees through charismatic leadership. In contrast, contingent reward leadership explains the transfer of obsessive passion43.

COR theory emphasizes individuals’ natural inclination to protect and accumulate resources, a tendency shaped by their perceptions and evaluations of these resources. These perceptions significantly influence their attitudes and behaviors. Hobfoll (1989) noted that employees’ resources, such as information, are not only sourced from peers and leaders but also shaped by the surrounding environment44. In line with COR theory, this study focuses on two critical types of resources: relational and emotional resources24. On the one hand, when employees perceive themselves to have fewer resources or less access to them compared to their peers, they may experience stress and anxiety, which could lead to negative work behaviors, particularly in terms of emotional resources26. On the other hand, in a highly competitive organizational environment, employees may engage in job-crafting behaviors to acquire additional resources45. Furthermore, when employees perceive their peers as overqualified, they recognize that the difficulty of obtaining relational resources has increased, heightening competition and triggering negative behaviors46.

Peer overqualification promotes employees’ obsessive work passion. From the perspective of the organizational environment, employees typically recognize the limited number of personal and work resources, and the access path is less favorable than that of overqualified peers. In a competitive environment, employees’ perceived peer overqualification will exert invisible pressure on themselves, forcing them to produce higher work requirements to mitigate status threats, which results in employees’ obsessive work passion15. From the personnel’s perspective, overqualified employees may experience emotional exhaustion due to autonomy deprivation4, leading to obsessive passion and adversely affecting their psychological and life health. When peers access and take advantage of superior resources, this phenomenon can trigger stress and anxiety among other employees, thereby fostering an obsessive passion for work.

Meanwhile, peer overqualification inhibits the generation of employees’ harmonious work passion. From the perspective of the organizational environment, the autonomy support environment47, organizational diversity atmosphere41, and the psychological climate of organizational cooperation48 all contribute to the harmonious work passion of employees. Peer qualification leads to unequal access and application of internal resources, which leads to a competitive organizational atmosphere. It is not conducive to generating a harmonious work passion among employees. From the perspective of individual factors, overqualified employees may think they have the right to secure better jobs, possess more superiority than their peers, and even become informal leaders within the team49. Employees’ perceived overqualification of their peers poses a threat to their social selves and creates job insecurity50. Individuals are relatively more prone to produce controlled internalization and obsessive work passion due to the pressure and demands of maintaining self-esteem and self-identity51. When individuals have high work autonomy, they are more likely to form harmonious work passion47. However, when individuals perceive the threat and external pressure brought by peer overqualification, they will reduce their sense of autonomy and inhibit the generation of harmonious work passion. Therefore, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a

Peer overqualification has a significant negative impact on harmonious work passion.

H1b

Peer overqualification has a significant positive impact on obsessive work passion.

The mediating role of perceived competitive climate

Perceived competitive climate refers to employees’ subjective assessment of the intensity of competition for resources (such as promotion opportunities, rewards, and recognition) in the work environment29. Relevant studies indicate that organizational resources, organizational uncertainty, and team scale are significant predictors of perceived competitive climate52,53. Peer overqualification, as a critical situational factor, influences organizational resources and thereby fosters the perception of a competitive climate. According to COR theory, overqualified individuals often monopolize key resources (e.g., high-value tasks, leadership attention), making it more difficult for other employees to access these resources22. Consequently, peer overqualification intensifies employees’ perception of a competitive climate.

Based on COR theory, we predict a negative relationship between perceived competitive climate and harmonious work passion, while anticipating a positive relationship between perceived competitive climate and obsessive work passion. The resource compensation mechanism of COR theory suggests that employees may overcommit to work to prove their self-worth in response to competitive pressures, developing a compulsive tendency to “work harder”54, such as workaholic behaviors55. Thus, perceived competitive climate triggers obsessive work passion. On the other hand, perceived competitive climate continuously depletes psychological resources, undermining employees’ sense of intrinsic control over their work and increasing feelings of burnout, thereby inhibiting the development of work enjoyment and harmonious work passion56,57. Therefore,

H2a

Perceived competitive climate plays a mediating role between peer overqualification and harmonious work passion.

H2b

Perceived competitive climate plays a mediating role between peer overqualification and obsessive work passion.

The mediating effect of job anxiety

Job anxiety refers to the tension and anxiety experienced by individuals when perceiving potential threats, primarily manifested as psychological stress31. Based on the anxiety literature and COR theory, we propose three pathways through which peer overqualification induces job anxiety in employees. First, in situations with limited work resources, the advantageous position of overqualified peers in resource acquisition can place other employees in a high-work-pressure state, thereby triggering job anxiety22. Second, peer overqualification may stimulate employees to engage in competition and knowledge hiding to meet job demands, increasing the likelihood of competitive and exclusionary behaviors among peers, which in turn induces higher anxiety15. Third, research by Guo et al. (2024) demonstrates that supervisors’ perceived overqualification can also evoke job anxiety23.

According to COR theory, job anxiety undermines employees’ harmonious work passion while stimulating obsessive work passion. Specifically, the resource spiral effect of COR theory posits that anxiety essentially reflects the ongoing depletion of psychological resources—that is, when individuals perceive their inability to replenish resources through effort (e.g., due to hopelessness about promotion), anxiety intensifies and may even lead to negative behaviors such as emotional exhaustion, burnout, and diminished well-being22,23,24. Therefore, job anxiety may serve as a critical pathway in triggering employees’ obsessive work passion while inhibiting harmonious work passion. Therefore,

H3a

Job anxiety plays a mediating role between peer overqualification and harmonious work passion.

H3b

Job anxiety plays a mediating role between peer overqualification and obsessive work passion.

The chain mediating effect of perceived competitive climate and job anxiety

The CAPS theory emphasizes that an individual’s cognitive-affective units exhibit systematic, complex, and dynamic characteristics27. The CAPS theory further posits that cognitive-affective units activated by situational stimuli can interact with each other, thereby influencing cognition, affect, and behavioral responses24,28. Firstly, according to CAPS theory, peer overqualification serves as a critical situational stimulus that activates employees’ cognitive appraisal systems. When employees observe that highly competent peers occupy more resources (e.g., promotion opportunities, key tasks), they encode this as a resource threat44, subsequently forming a strong perception of competitive climate (cognitive unit).

In addition, employees’ perceived competitive climate further triggers affective responses. Following the cognitive-affective transmission mechanism of CAPS, perceived competitive climate (cognitive unit) has a positive influence on job anxiety (affective unit). On the one hand, employees with a high perceived competitive climate experience relational resource strain caused by peer overqualification, which intensifies competition and can even lead to exclusion among peers, resulting in reduced self-control and higher levels of job anxiety58,59. So, peer overqualification induces job anxiety by exacerbating relational resource strain. On the other hand, García-Gonzálvez et al. (2022) demonstrate that competitive climate can lead employees to perceive threats to their professional status and job security, thereby triggering panic and anxiety60.

Furthermore, grounded in CAPS theory, after undergoing cognitive appraisal and experiencing affective responses, employees develop behavioral outcomes. Specifically, the more intense the perceived competitive climate, the higher the anxiety level and the greater the psychological resource depletion, ultimately resulting in decreased harmonious work passion and increased obsessive work passion.

As a result, this study proposes a serial mediation model of “peer overqualification (situational stimulus) - perceived competitive climate (cognitive appraisal) - job anxiety (affective response) - dualistic work passion (behavioral outcome)”. That is, peer overqualification strengthens the perceived competitive climate, which in turn exacerbates job anxiety, ultimately triggering obsessive work passion while inhibiting harmonious work passion. Therefore,

H4a

There is a chain mediating effect between perceived competitive climate and job anxiety between peer overqualification and obsessive work passion. Namely, peer overqualification increases employees’ perception of competitive climate and leads to an increase in job anxiety, thereby leading to an increase in obsessive work passion.

H4b

There is a chain mediating effect between perceived competitive climate and job anxiety between peer overqualification and harmonious work passion. Namely, peer overqualification increases employees’ perception of competitive climate, leading to an increase in job anxiety and a decrease in harmonious work passion.

Materials and methods

Samples and procedures

This study focuses on employees working in sectors characterized by a high prevalence of overqualification within the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. Questionnaires were distributed to individuals employed in finance, education, government agencies, and health care. Prior to the formal distribution, a pilot survey was conducted involving 50 questionnaires administered to academics, corporate employees, and managers across relevant fields. During the pilot phase, feedback was collected to identify and rectify potential issues, including unclear phrasing, semantic ambiguity, and imprecise wording.

This study adopted a two-stage data collection design with incentive measures. Prior to distributing the questionnaire, the research team communicated with corporate human resources management to secure administrative support61. During the offline questionnaire administration, we explicitly guaranteed that all collected data would be used solely for academic purposes, with sensitive information such as questionnaire responses and contact details being encrypted for processing. Furthermore, customized mugs were distributed to participants who completed the first-stage questionnaires, while chocolate gift boxes were provided to those who continued participation in the second stage (T2). The implementation of these measures significantly enhanced the questionnaire response rate in this study23,62,63. In the first stage, 700 questionnaires were distributed to MBA students and undergraduate graduates of Hebei University of Economics and Business, and 655 valid questionnaires were collected, which mainly included demographic information and the measurement of peer overqualification. This study conducted the second stage one month later, with a total of 589 respondents participating, and finally collected 532 questionnaires, including perceived competitive climate, job anxiety, and dualistic work passion. Among the 532 valid questionnaires, female respondents (56%) slightly outnumbered male respondents (44%), the majority of respondents were under 35 years old (61.1%), and the majority of respondents had a bachelor’s degree or above (72.4%). State-owned enterprises account for a large proportion (31.4%), while private enterprises and government agencies account for 19.9%. As for the sample source cities, first-tier cities account for 13.9%, second-tier cities for 23.5%, third-tier cities for 34.2%, fourth-tier cities for 25%, and fifth-tier cities for 3.4%. The above variables may affect the hypothesis results, so as a control variable.

Measures

The study employed a Likert 5-point scale to assess the constructs of peer overqualification, perceived competitive climate, job anxiety, harmonious work passion, and obsessive work passion, with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Dualistic work passion

Referring to the dualistic work passion scale compiled by Vallerand et al.17, the scale of harmonious work passion contains 7 items17, such as “my work is coordinated with other activities in my life”. The obsessive work passion scale contains 7 items, such as “without work, I cannot support myself “.

Peer overqualification

This study adopted the approach of Maynard and Parfyonova (2013) in measuring peer overqualification11. The peer overqualification scale contains 9 items, which involve overqualification in terms of education, knowledge, experience, and ability, such as “In my department, there are many peers who have a higher degree than the required for the job”.

Perceived competitive climate

This study used the scale of Zhu et al. (2018) to measure competitive climate, which has 6 items64, such as “In our team, everyone must compete with others so as not to be ignored”.

Job anxiety

The job anxiety scale by McCarthy et al.31 with a total of 8 items was used in this study31. For example, “I feel overwhelmed when I don’t do well at work”.

Control variables

Based on previous research and practical considerations, this study selected five demographic variables that may have an impact on dualistic work passion, including gender, age, educational background, organization size, and city type, as control variables to make the research results more accurate16.

Data analysis and results

Non-response bias test

Building on the Early-Late Responders Method put forward by Armstrong and Overton (1977)65, this study sorted the valid questionnaires by their submission times. The first 30% of respondents were categorized as “early responders”, while the last 30% were designated as “late responders”65,66. Through comparing the key variables of these two groups, we indirectly assessed the potential impact of non-response bias, in line with the methodology outlined by Armstrong and Overton (1977)65. To assess non-response bias, we used SPSS software for independent-samples t-tests and chi-square analyses65,66. The results showed no significant disparities, with all p-values exceeding 0.05. Therefore, there is no evidence of serious non-response bias.

Common method bias (CMB)

CMB refers to the measurement error caused by the method of measurement, particularly when using a single method (such as surveys) to collect data67. This study implemented several measures to mitigate the potential impact of CMB, including collecting data at different time points, using anonymous questionnaires, and avoiding language in questionnaire design that might lead participants’ responses. Moreover, this study employed Harman’s single-factor test to assess the impact of CMB67. In this study, the results of the exploratory factor analysis revealed that there were 5 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1. According to Harman’s single-factor test, we focused on the explained variance of the first factor. The results showed that the cumulative variance contribution of the first unrotated factor was only 41.52%, below the 50% threshold, indicating that CMB was not severe in this study68. Furthermore, Unmeasured Latent Method Factor Control was used to test the CMB in this study. We conducted the analysis using Mplus 25.0 and concluded the relevant indicators of the five-factor model (χ2/df = 1.639, RMSEA = 0.035, SRMR = 0.033, TLI = 0.970, CFI = 0.972). Then, we added the method factor CMF on the basis of the five-factor model. The six-factor results were χ2/df = 1.561, RMSEA = 0.032, SRMR = 0.030, TLI = 0.973, and CFI = 0.977. The comparison of fitting indicators shows that the six-factor model does not show significant optimization compared with the original model (ΔRMSEA = 0.003 < 0.05, ΔSRMR = 0.003 < 0.05, ΔTLI = 0.003 < 0.1, ΔCFI = 0.005 < 0.1), which indicates that there is no serious common method bias69.

Confirmatory factor analysis

Reliability analysis was conducted on the 6 variables using SPSS software, revealing that the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients for the peer overqualification (0.919), perceived competitive climate (0.901), job anxiety (0.944), harmonious work passion (0.928), and obsessive work passion (0.917) scale all exceeded 0.7. That outcome indicates high reliability for all scales. For model fit analysis, AMOS software was utilized (as shown in Table 1). The results showed that the five-factor model provided a good fit: χ2/df = 1.637, RMSEA = 0.035; RMR = 0.035, GFI = 0.907, IFI = 0.972, TLI = 0.970, and CFI = 0.972.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Table 2 shows the mean, standard deviation, and correlation coefficients of each variable. Peer overqualification is significantly positively correlated with perceived competitive climate (r = 0.583, p < 0.01) and negatively correlated with job anxiety (r = – 0.575, p < 0.01); the perceived competitive climate (r = 0.488, p < 0.01) is positively correlated with harmonious work passion, and job anxiety (r = – 0.444, p < 0.01) were significantly negatively correlated with the harmonious work passion; the perceived competitive climate is significantly negatively correlated with obsessive work passion (r = – 0.198, p < 0.01), and job anxiety is significantly positively correlated with obsessive work passion (r = 0.513, p < 0.01). The above results are in line with theoretical expectations and provide preliminary support for the hypothesis.

Hypothesis tests

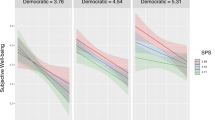

To test the main effect, this study firstly conducted a regression analysis of the relevant variables through SPSS analysis software. The results of the regression analysis are presented in Table 3. From the model 7 in Table 3, it shows that peer overqualification has a negative impact on harmonious work passion (β= −0.486, p < 0.001) significantly. Model 11 shows that peer overqualification has a significantly positive impact on obsessive work passion (β = 0.454, p < 0.001). Accordingly, the H1a is supported, which indicates that peer overqualification significantly and negatively affects employees’ harmonious work passion, and H1b is supported as well. Meanwhile, the mediating effect is tested through the hierarchical regression. Model 7 shows that peer overqualification has a significantly negative impact on harmonious work passion. And adding perceived competitive climate into model 8, competitive climate perception has a significant impact on harmonious work passion (β= −0.416, p < 0.001), peer overqualification still has a negative and significant impact on harmonious work passion (β=−0.254, p < 0.001), but the coefficient is improved compared to model 7, indicating that the perceived competitive climate has a significant mediating effect between peer overqualification and harmonious work passion, and the results support H2a. Model 12 shows that perceived competitive climate positively affects employees’ obsessive work passion (β = 0.434, p < 0.001), peer overqualification still has a significant impact on obsessive work passion (β = 0.210, p < 0.001), but the coefficient decreases compared to model 11. The above results show that the perceived competitive climate plays a partial mediating role between peer overqualification and obsessive work passion. Therefore, H2b is preliminarily verified.

Based on the model 7, peer overqualification and harmonious work passion (β= −0.486, p < 0.001) significantly negative correlation; model 4 shows that peer overqualification positively affects employees’ job anxiety (β = 0.507, p < 0.001) significantly; model 9 shows that job anxiety has a significantly negative impact on employees’ harmonious work passion (β= −0.369, p < 0.001), and peer overqualification still have a significant impact on harmonious work passion (β= −0.300, p < 0.001). The above results show that job anxiety plays a partial mediating role between peer overqualification and harmonious work passion. Therefore, H3a is preliminarily verified. Model 11 shows that peer overqualification and obsessive work passion have a significantly positive correlation (β = 0.454, p < 0.001). The model 4 shows that peer overqualification has a significantly positive impact on employees’ job anxiety (β = 0.507, p < 0.001); and the model 13 shows that job anxiety has a significantly positive impact on employees’ obsessive work passion (β = 0.336, p < 0.001). Besides, peer overqualification still has a significant impact on obsessive work passion (β = 0.283, p < 0.001), but the coefficient decreases, indicating that job anxiety plays a partial mediating role between peer overqualification and obsessive work passion. Therefore, H3b is preliminarily verified.

To further verify the chain mediating effect of perceived competitive climate and job anxiety, the process plugin was used again to test the chain mediating effect. The results are shown in Table 4, and the confidence intervals for the indirect effect of peer overqualification on dualistic work passion do not include 0. Further testing of the specific indirect effects of the chain mediating variable shows that perceived competitive climate and job anxiety have a significant chain mediating effect on the dualistic work passion in peer overqualification (confidence intervals do not include 0). Therefore, H4a and H4b are preliminarily verified.

Discussion and implications

This study, based on COR theory and CAPS theory, developed a mediated chain model to explore how peer overqualification influences employees’ dualistic work passion. The results indicate that peer overqualification has a negative impact on employees’ harmonious work passion (β = −0.486, p < 0.001) and a positive influence on their obsessive work passion (β = 0.454, p < 0.001). Moreover, the study finds that perceived competitive climate and job anxiety partially mediate the relationship between peer overqualification and dualistic work passion. Additionally, the perceived competitive climate and job anxiety have a significant chain mediating effect on dualistic work passion in the context of peer overqualification (confidence intervals do not include 0). Specifically, peer overqualification increases employees’ perception of a competitive climate, which in turn raises job anxiety and decreases harmonious work passion.

Theoretical implications

The theoretical contributions mainly include three points. First, we have enriched the research results on peer overqualification and broadened the research perspective on overqualification. Research on overqualification mainly explores the impact of employees’ perceived overqualification on their work attitudes or behaviors within the organization, such as stimulating constructive behavior4. In contrast, this study highlights the role of comparisons between individuals, specifically how employees perceive their peers’ overqualification, which in turn affects their work attitudes and emotional responses. Specifically, this study adopted a different perspective, using the degree of peer overqualification as the independent variable. Its findings expand the overqualification theory to include peer overqualification, revealing how comparisons between peers influence employees’ work passion.

Second, this study supplemented the research on the antecedent variables of dualistic work passion. There is a wealth of exploration of the antecedents of dualistic work passion in domestic and foreign literature, such as self-esteem36, autonomous support environments47, and so on. However, there is a lack of research on the influence of peer factors on employees’ dualistic work passions. Meanwhile, by focusing on the dualistic model of passion, namely harmonious and obsessive work passion, this study shows how both are influenced by peer overqualification. That not only aligns with but also empirically enriches the theoretical framework of dualistic work passion. Increasingly, research suggests that work passion should be examined from both positive and negative dimensions70,71,72. The findings of this study show that peer overqualification, through the mediating effects of perceived competitive climate and job anxiety, can foster obsessive work passion while potentially inhibiting harmonious work passion. This finding refines the theoretical framework of dualistic work passion and further illustrates the role of peer overqualification in shaping employees’ work passion.

Third, this study explains from the perspective of COR theory how peer overqualification acts as a “resource threat” that affects employees’ emotional and behavioral responses. Traditionally, COR theory focuses on how individuals manage the gain and loss of resources under stress. When resource loss outweighs gain, individuals tend to reduce their effort and avoid showing resources in order to protect what they have73. This study introduces peer overqualification as an external factor and shows that when employees perceive their peers as having more resources or abilities, they may feel a sense of resource threat. This perception then triggers job anxiety, which affects their work passion. These findings add to COR theory by showing that external competition does not only affect people through physical resource loss, but also through emotional and cognitive pathways that influence their motivation and behavior at work.

Finally, this study empirically verifies a comprehensive pathway of “situational stimulus – cognitive appraisal – affective response – behavioral outcome,” thereby extending the explanatory power of the CAPS theory in the field of organizational behavior. The CAPS theory emphasizes that individual behavior results from the joint effects of cognitive and affective systems activated by situational factors. However, previous studies have primarily focused on either cognitive or affective pathways in isolation and have rarely examined how these two systems interact dynamically in real-world contexts. For example, in studies on leadership styles or digital leadership, researchers have pointed out that focusing only on a single cognitive or emotional path is not enough to explain the complexity of employee behavior. They suggest building a more comprehensive framework that integrates both cognition and affect74,75. Building on this idea, the present study takes peer overqualification as the entry point and systematically shows how it activates employees’ cognitive evaluations (i.e., perceived competitive climate) and emotional responses (i.e., job anxiety), which in turn lead to different forms of work passion (harmonious vs. obsessive). This chain mediation model not only fills a gap in the CAPS theory regarding the interaction between cognition and affect in organizational contexts but also expands the theory’s application in the study of social comparison and work motivation.

Practical implications

First, with the arrival of the economic crisis in the post-pandemic era, overqualification has become widespread. Leaders should dialectically view the phenomenon of overqualification in organizations and fully utilize its positive effects. This study finds that peer overqualification increases employees’ perception of a competitive climate, which indirectly triggers job anxiety and affects work passion. There are also studies indicating that perceived overqualification has a specific positive effect on employee creativity76, constructive behavior77, and role performance16. Meanwhile, overqualification reflects surplus skills and qualifications, which can lead to a positive self-evaluation and increase employees’ proactive behavior10. Therefore, managers should ensure transparency in job responsibilities and promotion mechanisms to reduce employees’ feelings of being suppressed or treated unfairly. That can help weaken the “perceived threat” caused by qualification differences. Meanwhile, managers should create and build a culture of positive comparison within teams, encouraging employees to learn from highly qualified peers rather than compete with them. For example, organizations can introduce knowledge-sharing incentives or mentorship programs that encourage highly qualified employees to share resources instead of competing with one another.

Second, managers should also pay attention to the adverse effects of overqualification on the organization and reduce its negative impact. The sense of overqualification reduces harmonious work passion, which is detrimental to the enterprise’s long-term development. This study confirms that job anxiety mediates the relationship between peer overqualification and obsessive work passion, and may also reduce harmonious passion. Therefore, HR department can regularly assess employees’ emotional states through surveys or interviews. These assessments can help identify groups under potential stress caused by workplace comparisons and resource-related anxiety. For employees with high levels of anxiety, managers can implement programs such as phased task adjustments to give them time to recover emotionally and regain a sense of engagement. This may help reduce excessive work input driven by anxiety and lower the risk of developing obsessive work passion.

Finally, this study finds that reasonable resource pressure can, through contextual design, stimulate employees’ harmonious work passion, while perceived resource threats may weaken it. Therefore, managers can adopt a tiered approach to enhance employees’ harmonious passion by increasing their sense of access to resources and autonomy. Specifically, employees can be divided into two groups, new and experienced. For new employees, managers can design a “quick integration & low-risk challenge” path, such as offering training, assigning basic projects, and encouraging teamwork tasks. The goal is to help them gradually build a sense of resource control in a safe and supportive environment. For experienced employees, managers can assign “empowered tasks” or define “expert roles” to strengthen their sense of control and achievement in a high-qualification environment. This can boost their harmonious work passion and help prevent feelings of marginalization caused by resource comparison.

Conclusion

In the context of “involution” and “overqualification”, it is crucial to explore how could peer overqualification influence the development of employees’ dualistic work passion. In response to the three research questions which are proposed as the beginning, this study provides several key findings through a survey of 532 Chinese employees. First, regarding RQ1, this study finds that perceived peer overqualification has a dual effect on employees’ work passion. It increases obsessive work passion while reducing harmonious work passion. Second, in answer to RQ2, the analysis results show that perceived competitive climate and job anxiety both serve as mediators, individually and sequentially, in the relationship between peer overqualification and dualistic work passion. These findings support the proposed cognitive and emotional mechanisms based on COR and CAPS theories. Finally, concerning RQ3, the study suggests that employees who perceive their peers as overqualified may struggle to derive value from their own work, especially when they experience a strong competitive climate and high job anxiety. Specifically, managers should actively realize the problem and reduce the negative emotional impact of peer overqualification by enhancing transparency, fostering a culture of collaboration, and designing supportive task environments.

Limitations and future directions

Although this study focuses on the hot area of peer overqualification and dualistic work passion and points out the direction for future research, it still has certain limitations. First, the data sources for this study are mainly concentrated in industries with excessive qualifications in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region of China. In the future, scholars can expand the data collection field and revalidate this study’s conclusions. What’s more, it may also be considered to collect data by industry for comparative analysis and research. Second, this study examines the impact mechanisms of peer overqualification and dualistic work passion from a cognitive and affective perspective. There may also be other transmission mechanisms for the impact of peer overqualification on dualistic work passion. Future research can further explore the internal impacting mechanisms of the relationship between the two from different perspectives. Third, this study employed a two-stage survey method, which starts with a pilot survey followed by large-scale data collection. However, it did not adopt a longitudinal design, which limits the ability to test the causal ordering of variables over time. Future research could employ longitudinal tracking methods or experience sampling techniques to examine both the long-term causal relationships and short-term mechanisms among key variables.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. Data are not publicly available due to a confidentiality agreement with participants. The questionnaire used in this study is available at the following DOI: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29896325.v1.

References

Luksyte, A., Bauer, T. N., Debus, M. E., Erdogan, B. & Wu, C. H. Perceived overqualification and collectivism orientation: implications for work and nonwork outcomes. J. Manag. 48, 319–349 (2022).

Lin, B., Law, K. S. & Zhou, J. Why is underemployment related to creativity and OCB? A Task-Crafting explanation of the curvilinear moderated relations. AMJ 60, 156–177 (2017).

Shiyuan, Y. et al. Impact of human capital and social capital on employability of Chinese college students under COVID-19 epidemic—Joint moderating effects of perception reduction of employment opportunities and future career clarity. Front. Psychol. 13, 1046952 (2022).

Erdogan, B. & Bauer, T. N. Overqualification at work: A review and synthesis of the literature. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 8, 259–283 (2021).

Guo, T. et al. Perceived overqualification and innovative work behavior: a moderated mediation model. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 11, 1511 (2024).

He, G. & Li, W. The paradox of excess: how perceived overqualification shapes innovative behavior through self-concept. Curr. Psychol. 43, 17487–17499 (2024).

Volery, T. & Tarabashkina, L. The impact of organisational support, employee creativity and work centrality on innovative work behaviour. J. Bus. Res. 129, 295–303 (2021).

Li, Y. & Wang, S. The path from overqualification to success: career adaptability perspective. Curr. Psychol. 43, 9920–9932 (2024).

Purohit, B. Salesperson performance: role of perceived overqualification and organization type. MIP 36, 79–92 (2018).

Erdogan, B. & Bauer, T. N. Perceived overqualification and its outcomes: the moderating role of empowerment. J. Appl. Psychol. 94, 557–565 (2009).

Maynard, D. C. & Parfyonova, N. M. Perceived overqualification and withdrawal behaviours: examining the roles of job attitudes and work values. J. Occupat Organ. Psyc. 86, 435–455 (2013).

Kahn, W. A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 33, 692–724 (1990).

Cheng, B., Zhou, X., Guo, G. & Yang, K. Perceived overqualification and cyberloafing: a moderated-mediation model based on equity theory. J. Bus. Ethics. 164, 565–577 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Bolino, M. C. & Yin, K. The interactive effect of perceived overqualification and peer overqualification on peer ostracism and work meaningfulness. J. Bus. Ethics. 182, 699–716 (2023).

Zhang, H., Li, L., Shan, X. & Chen, A. Do overqualified employees Hide knowledge? The mediating role of psychological contract breach. Front. Psychol. 13, 842725 (2022).

Hu, J. et al. There are lots of big fish in this pond: the role of peer overqualification on task significance, perceived fit, and performance for overqualified employees. J. Appl. Psychol. 100, 1228–1238 (2015).

Vallerand, R. J. et al. Les passions de l’âme: on obsessive and harmonious passion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 85, 756–767 (2003).

Shalley, C. et al. Oxford University Press,. Does passion fuel entrepreneurship and job creativity? in The Oxford Handbook of Creativity, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship (eds. Shalley, C., Hitt, M. A. & Zhou, J.) 59–82 (2015).

Pollack, J. M., Ho, V. T., O’Boyle, E. H. & Kirkman, B. L. Passion at work: A meta-analysis of individual work outcomes. J. Organ. Behav. 41, 311–331 (2020).

Chen, P., Lee, F. & Lim, S. Loving Thy work: developing a measure of work passion. Eur. J. Work Organizational Psychol. 29, 140–158 (2020).

Cui, Z. Good soldiers or bad apples? Exploring the impact of employee narcissism on constructive and destructive voice. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 10, 715 (2023).

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P. & Westman, M. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 5, 103–128 (2018).

Guo, L., Du, J. & Zhang, J. Supervisor bottom-line mentality and employee workplace well-being: a multiple mediation model. BJM 19, 218–233 (2024).

Yao, Z., Zhang, X., Luo, J. & Huang, H. Offense is the best defense: the impact of workplace bullying on knowledge hiding. JKM 24, 675–695 (2020).

Wu, X. & Ma, F. How perceived overqualification affects radical creativity: the moderating role of supervisor-subordinate Guanxi. Curr. Psychol. 42, 25127–25141 (2023).

Hobfoll, S. E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 50, 337–421 (2001).

Mischel, W. & Shoda, Y. Reconciling processing dynamics and personality dispositions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 49, 229–258 (1998).

Mischel, W. & Shoda, Y. A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychol. Rev. 102, 246–268 (1995).

Brown, S. P., Cron, W. L. & Slocum, J. W. Effects of trait competitiveness and perceived intraorganizational competition on salesperson goal setting and performance. J. Mark. 62, 88–98 (1998).

Erdogan, B., Karaeminogullari, A., Bauer, T. N. & Ellis, A. M. Perceived overqualification at work: implications for extra-role behaviors and advice network centrality. J. Manag. 46, 583–606 (2020).

McCarthy, J. M., Trougakos, J. P. & Cheng, B. H. Are anxious workers less productive workers? It depends on the quality of social exchange. J. Appl. Psychol. 101, 279–291 (2016).

Dou, G., Li, G., Yuan, Y., Liu, B. & Yang, L. Structural dimension exploration and measurement scale development of employee Involution in china’s workplace field. IJERPH 19, 14454 (2022).

Lobene, E. V., Meade, A. W. & Pond, S. B. Perceived overqualification: A Multi-Source investigation of psychological predisposition and contextual triggers. J. Psychol. 149, 684–710 (2015).

Wiegand, J. P. When overqualification turns dark: A moderated-mediation model of perceived overqualification, narcissism, frustration, and counterproductive work behavior. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 214, 112351 (2023).

Perrewé, P. L., Hochwarter, W. A., Ferris, G. R., McAllister, C. P. & Harris, J. N. Developing a passion for work passion: future directions on an emerging construct. J. Organ. Behav. 35, 145–150 (2014).

Lafrenière, M. A. K., Bélanger, J. J., Sedikides, C. & Vallerand, R. J. Self-esteem and passion for activities. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 51, 541–544 (2011).

Vergauwe, J., Wille, B., De Caluwé, E. & De Fruyt, F. Passion for work: relationships with general and maladaptive personality traits and work-related outcomes. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 185, 111306 (2022).

Collewaert, V., Anseel, F., Crommelinck, M., De Beuckelaer, A. & Vermeire, J. When passion fades: disentangling the Temporal dynamics of entrepreneurial passion for founding. J. Manage. Stud. 53, 966–995 (2016).

Zigarmi, D., Galloway, F. J. & Roberts, T. P. Work locus of Control, motivational Regulation, employee work Passion, and work intentions: an empirical investigation of an appraisal model. J. Happiness Stud. 19, 231–256 (2018).

Li, J., Zhang, J. & Yang, Z. Associations between a leader’s work passion and an employee’s work passion: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. 8, 1447 (2017).

Luu, T. T. Can diversity climate shape service innovative behavior in Vietnamese and Brazilian tour companies? The role of work passion. Tour. Manag. 72, 326–339 (2019).

Trépanier, S. G., Fernet, C., Austin, S., Forest, J. & Vallerand, R. J. Linking job demands and resources to burnout and work engagement: does passion underlie these differential relationships? Motiv Emot. 38, 353–366 (2014).

Ho, V. T. & Astakhova, M. N. The passion bug: how and when do leaders inspire work passion? J. Organ. Behav. 41, 424–444 (2020).

Hobfoll, S. E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44, 513–524 (1989).

Du, Y., Luo, J. & Su, Y. Job crafting towards strengths and interests: how overqualification enhances creativity? Serv. Ind. J. 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2025.2457548 (2025).

Wrzesniewski, A., LoBuglio, N., Dutton, J. E. & Berg, J. M. Job crafting and cultivating positive meaning and identity in work. in Advances in Positive Organizational Psychology (ed Bakker, A. B.) vol. 1 281–302 (Emerald Group Publishing Limited, (2013).

Fernet, C., Lavigne, G. L., Vallerand, R. J. & Austin, S. Fired up with passion: investigating how job autonomy and passion predict burnout at career start in teachers. Work Stress. 28, 270–288 (2014).

Ho, V. T., Wong, S. S. & Lee, C. H. A Tale of passion: linking job passion and cognitive engagement to employee work performance: A Tale of passion. J. Manage. Stud. 48, 26–47 (2011).

Erdogan, B., Tomás, I., Valls, V. & Gracia, F. J. Perceived overqualification, relative deprivation, and person-centric outcomes: the moderating role of career centrality. J. Vocat. Behav. 107, 233–245 (2018).

Jiang, J., Dong, Y., Hu, H., Liu, Q. & Guan, Y. Leaders’ response to employee overqualification: an explanation of the curvilinear moderated relationship. J. Occupat Organ. Psyc. 95, 459–494 (2022).

Mageau, G. A., Carpentier, J. & Vallerand, R. J. The role of self-esteem contingencies in the distinction between obsessive and harmonious passion. Euro. J. Social Psych. 41, 720–729 (2011).

Dong, Y., Luksyte, A., Zhang, M. & Ma, L. Employees’ perceived overqualification and spouses’ Family-Work enrichment: examining the role of schedule control and competitive climate. Pers. Psychol. 78, 277–299 (2025).

Lee, A. et al. Upward leader-member exchange social comparison and organizational citizenship behaviour: the mediating role of interpersonal justice and moderating role of competitive climate. Eur. J. Work Organizational Psychol. 34, 91–108 (2025).

Clark, M. A., Michel, J. S., Zhdanova, L., Pui, S. Y. & Baltes, B. B. All work and no play? A Meta-Analytic examination of the correlates and outcomes of workaholism. J. Manag. 42, 1836–1873 (2016).

Keller, A. C., Spurk, D., Baumeler, F. & Hirschi, A. Competitive climate and workaholism: negative sides of future orientation and calling. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 96, 122–126 (2016).

Bochoridou, A., Gkorezis, P., Chatziioannou, A., Sidiropoulou, F. & Paltoglou, A. Perceived overqualification and intention to leave the profession: the mediating role of work enjoyment and the moderating role of competitive psychological climate. Curr. Psychol. 44, 7236–7249 (2025).

Liu, D., Chen, X. P. & Yao, X. From autonomy to creativity: A multilevel investigation of the mediating role of harmonious passion. J. Appl. Psychol. 96, 294–309 (2011).

Haider, S., Fatima, N. & Pablos-Heredero, C. D. A Three-Wave longitudinal study of moderated mediation between perceptions of politics and employee turnover intentions: the role of job anxiety and political skills. Revista De Psicología Del. Trabajo Y De Las Organizaciones. 36, 1–14 (2020).

Dormann, C., Zapf, D. & Isic, A. Emotionale Arbeitsanforderungen und ihre Konsequenzen bei Call Center-Arbeitsplätzen. Zeitschrift für Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie A&O 46, 201–215 (2002).

García-Gonzálvez, S. & López-Plaza, D. Abellán-Aynés, O. Influence of competition on anxiety and heart rate variability in young tennis players. Healthcare 10, 2237 (2022).

Uddin, M. K., Azim, M. T. & Islam, M. R. Effect of perceived overqualification on work performance: influence of moderator and mediator. Asia Pac. Manage. Rev. 28, 276–286 (2023).

Rogelberg, S. G. & Stanton, J. M. Introduction: Understanding and dealing with organizational survey nonresponse. Organizational Res. Methods. 10, 195–209 (2007).

Sauermann, H. & Roach, M. Increasing web survey response rates in innovation research: an experimental study of static and dynamic contact design features. Res. Policy. 42, 273–286 (2013).

Zhu, Y. Q., Gardner, D. G. & Chen, H. G. Relationships between work team Climate, individual Motivation, and creativity. J. Manag. 44, 2094–2115 (2018).

Armstrong, J. S. & Overton, T. S. Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 14, 396 (1977).

Singh, K., Chatterjee, S. & Mariani, M. Applications of generative AI and future organizational performance: the mediating role of explorative and exploitative innovation and the moderating role of ethical dilemmas and environmental dynamism. Technovation 133, 103021 (2024).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903 (2003).

Huang, H. C. Entrepreneurial resources and speed of entrepreneurial success in an emerging market: the moderating effect of entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep Manag J. 12, 1–26 (2016).

Ding, C., Su, M., Pei, J., Zhu, C. J. & Zhao, S. When and Why Negative Supervisor Gossip Yields Functional and Dysfunctional Consequences on Subordinate Interactive Behaviors. J Bus. Ethics 200(1), 137–155 (2024).

Zhang, L., Mao, M., Li, J. & Zhang, D. Navigating the algorithmic paradox: how and when perceived algorithmic control affects gig workers’ engagement through harmonious and obsessive work passion. Inform. Technol. People. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-08-2024-1030 (2025).

Luksyte, A. & Carpini, J. A. Perceived overqualification and subjective career success: is harmonious or obsessive passion beneficial? Appl. Psychol. 73, 2077–2106 (2024).

Astakhova, M. N., McKay, A. S., Doty, D. H. & Wooldridge, B. R. Does one size fit all? The role of job characteristics in cultivating work passion across knowledge, blue-collar, nonprofit, and managerial work. Hum. Resour. Manag. 63, 443–462 (2024).

Kumar, S. S., Tubuna, K., Lal, A. A., Prasad, R. R. & Lingam, S. Employee Learning Agility as an Antecedent of Knowledge Sharing in the Supply Chain: An Examination Through the Lens of Conservation of Resource Theory. in Advances in Environmental Accounting & Management (eds. Elias, A. A., Pepper, M., Gurumurthy, A. & Shukla, A. K.) 93–114 (Emerald Publishing Limited, 2024).

Liu, J., Zhou, X. & Wang, Q. The influence of entrepreneurial leadership on employee improvisation in new ventures: based on cognitive-affective processing system framework. K 52, 3566–3587 (2023).

Gao, P. & Gao, Y. How does digital leadership foster employee innovative behavior: A Cognitive–Affective processing system perspective. Behav. Sci. 14, 362 (2024).

Dar, N., Ahmad, S. & Rahman, W. How and when overqualification improves innovative work behaviour: the roles of creative self-confidence and psychological safety. PR 51, 2461–2481 (2022).

Duan, J., Xia, Y., Xu, Y. & Wu, C. The curvilinear effect of perceived overqualification on constructive voice: the moderating role of leader consultation and the mediating role of work engagement. Hum. Resour. Manag. 61, 489–510 (2022).

Funding

This study was funded by Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department (BJ2025264), and Hebei Human Resources and Social Security Research Cooperation Project (JRSHZ-2024-01017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Y.W.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Validation. C.L.Y.: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. J.Y.K.: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. M.M.W.: Resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

All participants provided written informed consent before taking part in the study. They were clearly informed that their participation was entirely voluntary and that they could withdraw from the survey at any point without facing any negative consequences. Instructions were given to ensure participants understood how to complete the questionnaire. Participants were also assured that their responses would remain confidential and that all information collected would be used solely for academic research purposes.

Ethics statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hebei University of Economics and Business. All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with relevant institutional guidelines and the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation, written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All data collected were used for academic research purposes only.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, LY., Kong, JY., Yao, CL. et al. The effects of peer overqualification on dualistic work passion through the sequential mediation of perceived competitive climate and job anxiety. Sci Rep 15, 44741 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28658-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28658-3