Abstract

Polyherbal formulations are increasingly investigated for their synergistic antioxidant potential against oxidative stress–related disorders. This study evaluated a polyherbal ethanol extract derived from Abelmoschus esculentus pods and Telfairia occidentalis leaves (AETO-PHF) through integrated in vitro and in silico approaches. GC–MS analysis identified 37 compounds, with dodecanoic acid (16.24%) and 9-octadecenoic acid (Z)-,2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester (16.41%) as predominant constituents. Antioxidant assays revealed potent dose-dependent radical scavenging, with IC₅₀ values of 61.39 ± 0.17 µg/mL (DPPH), 11.15 ± 0.15 µg/mL (H₂O₂ scavenging), 61.75 ± 0.00 µg/mL (FRAP), and 38.97 ± 2.66 µg/mL (NO inhibition). These results were statistically comparable (p > 0.05) to ascorbic acid (61.38 ± 0.58, DPPH; 61.71 ± 0.20, FRAP; and 38.94 ± 0.00, NO inhibition µg/mL) and gallic acid (11.30 ± 0.84 µg/mL, H₂O₂ scavenging). Molecular docking against cytochrome c peroxidase showed strong interactions of dodecanoic acid (− 5.7 kcal/mol) and 9-octadecenoic acid ester (− 6.2 kcal/mol), both surpassing the binding affinity of the reference antioxidant ascorbic acid (− 5.5 kcal/mol). Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed stable protein–ligand complexes with favorable RMSD, RMSF, and hydrogen-bond interaction profiles. These findings validate the traditional use of A. esculentus and T. occidentalis, demonstrate synergistic antioxidant efficacy of their polyherbal blend, and provide molecular-level insights into their mechanism of action. AETO-PHF represents a promising candidate for nutraceutical and therapeutic applications against oxidative stress-related diseases, meriting further in vivo and clinical studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oxidative stress is a critical factor in the development of various chronic illnesses, including diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and aging-related conditions1,2,3,4. This is caused by an imbalance between the body ‘s antioxidant defenses and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Excessive ROS disrupt cellular macromolecules such as lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, impairing cellular function and viability5,6,7. Addressing oxidative stress is therefore essential for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies for these widespread diseases8,9,10.

Natural antioxidants derived from plants have gained considerable attention because they offer potent free radical scavenging abilities with minimal toxicity compared to synthetic antioxidants, whose long-term safety and effectiveness remain questionable11,12,13,14,15,16. In this context, A. esculentus and T. occidentalis are notable for their rich phytochemical profiles and traditional therapeutic use across Africa. A. esculentus is distinguished by its polyphenolic, flavonoid, vitamin, and mineral contents, with documented antioxidant, antidiabetic, antimicrobial, and hepatoprotective effects, particularly linked to its mucilaginous polysaccharides that regulate glucose and scavenge ROS17,18,19. Similarly, T. occidentalis is a nutrient-dense leafy vegetable rich in iron, protein, and essential minerals, exhibiting antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and hepatoprotective properties supportive of its customary use in treating anemia, immune disorders, and diabetes. The rationale for combining these two species in a polyherbal formulation lies in the potential synergistic interactions among their diverse phytochemicals, which could enhance antioxidant activity beyond what is achievable by individual extracts. This approach aligns with contemporary phytopharmaceutical strategies that favor multi-component herbal medicines for tackling complex diseases related to oxidative stress.

This study is framed around three key considerations. First, A. esculentus and T. occidentalis are widely available and economically feasible in developing regions. This accessibility improves their use in therapeutic applications. Second, there is a need for comparative phytochemical and bioactivity analyses. Such studies will guide the discovery of novel natural antioxidants. Third, the study integrates advanced analytical techniques such as GC–MS with computational methods, including in silico studies. These approaches aim to identify the chemical composition and mechanistic interactions of the polyherbal formulation at the molecular level.

Despite extensive literature on the individual antioxidant properties of these plants17,18,19,20,21, there remains an important gap regarding their combined synergistic effects, detailed chemical characterization of their mixture, and mechanistic insights derived from in silico modeling. Polyherbalism has been used for millennia, yet it needs stringent scientific validation and mechanistic elucidation, especially with these two common species. Also, while GC–MS has been widely employed for phytochemical profiling of single plant extracts22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29, comprehensive chemical analysis of a combined A. esculentus and T. occidentalis formulation is absent. Similarly, in silico methods have not previously been applied to explore the specific molecular targets and antioxidant mechanisms of this polyherbal extract30.

Addressing these gaps, the present study aims to provide a detailed GC–MS profile of the polyherbal formulation (AETO-PHF), establish its in vitro antioxidant potential through standardized free radical scavenging assays, and predict the binding interactions of key phytochemicals with oxidative stress-related molecular targets via molecular docking and molecular dynamics(MD) simulations. This integrative methodology seeks to scientifically validate the traditional use, reveal potential synergistic effects, and identify promising bioactive compounds for natural antioxidant drug development, thus laying groundwork for novel phytotherapeutics.

Materials and methods

All reagents employed were of analytical grade and obtained from Sigma Aldrich Chemical Company, Germany.

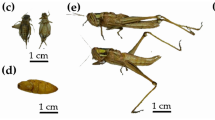

Acquisition and identification of flora

The specimens were gathered at MOUAU, Nigeria, on January 3, 2024. Identification and authentication were conducted at the PG laboratory of MOUAU, Nigeria. The voucher numbers are PO11MIZEB21 for AE and PO11PGZEB22 for PO (See related file section).

Extraction

The pods of AE and leaves of PO were were dried at 27 °C. Thereafter, they were ground and weighed. Extraction was conducted using the cold maceration technique31. Equation 1 was used to calculate extraction yield (EY) after percolating 50 g of each powdered plant in 2.5 L of 95% analytical-grade ethanol to produce the crude ethanol extract. The extract was filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper and concentrated at 34 °C using a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure.

EY = Extraction yield (%), while EA = extracted weight.

OA denotes the initial weight of the plant material (grams). The extraction yield was 22%.

GC–MS analysis

A Trace GC Ultra gas chromatograph (THERMO, Waltham, MA, USA) fitted with a Thermo mass spectrometer was used to analyse the AETO-PHF ethanol extracts. The DB-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., film thickness = 0.25 m) operated in split mode (1:10 split ratio) and one microlitre of extract was injected per analysis. Helium at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min was used as the carrier gas. The temperature of the injection port was kept at 250 °C. After starting at 60 °C and holding it for two minutes, the oven temperature programme increased by 10 °C per minute to 280 °C and held it there for ten minutes. At 70 eV, electron impact (EI) ionisation was carried out with an ion source temperature of 230 °C and a transfer line temperature of 280 °C. With a three-minute solvent delay, the mass spectrometer scanned in the m/z 50–650 range. To identify the compound, the resulting mass spectra were compared to the NIST and Wiley spectral libraries. Also, in accordance with Elwekee et al.29, retention indices were computed in relation to the retention durations of n-alkanes (C8–C22) under the same chromatographic conditions.

In vitro antioxidant activity

DPPH method

A solution of DPPH in methanol with a concentration of 1 × 10–4 M was prepared. 1 mL aliquots of the ethanol extract were obtained at seven distinct concentrations: 15.63, 31.2, 62.5, 125 and 250 µg/mL. Each sample and concentration were reproduced thrice. Each aliquot received 2 mL of a DPPH methanol solution. For half an hour, the solution was kept at 30 °C in a dark environment. Absorbance of the solution was also determined with the aid of a UV-30 spectrophotometer with a wavelength of 517 nm. The DPPH methanol solution was used to make a blank. The standard was ascorbic acid (ASC)32.

H2O2 scavenging activity assay

The extract ‘s ability to scavenge H2O2 was evaluated by means of a replacement titration assay33. The mixture consisted of 100 µL of the extract at different doses and 100 µL of 0.1 mM H2O2. Afterwards, we supplemented the mixture with 2 µL of 3% ammonium molybdate, 200 µL of 2 M H2SO4, and 100 µL of 1.8 M KI. The yellow hue was removed by titrating the resulting solution with a 5.09 mM NaS2O3 solution. To determine the percentage of H2O2 scavenging, the following formula was used: % Inhibition = [(V0 − V1)/V0 × 100]. In this formula, V0 is the volume of NaS2O3 solution that was used to titrate the control sample without extract, in the presence of H2O2. V1 is the volume of NaS2O3 solution that was used with the extract. The standard was gallic acid.

FRAP method

The FRAP assay was carried out using the Egbucha et al. method32. The following five doses of ethanol extract were used in 0.2 mL aliquots: 15.63, 31.2, 62.5, 125 and 250 µg/mL. Triplicates of each sample and concentration were used. To these aliquots, 3.8 mL of FRAP reagent was added. The FRAP reagent was made by mixing one part of a 20 mM FeCl3 hexahydrate solution, ten parts of a 300 mM sodium acetate buffer solution at pH 3.6, and one part of a 10 mM 2,4,6-Tripyridyl-S-Triazine (TPTZ) solution. The resultant mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Absorbance detection was made by operating a UV-30 spectrophotometer at 593 nm. For the blank, the dilute extract was substituted with the volume equivalent to methanol. A calibration with ascorbic acid was carried out. The samples were assessed alongside the ASC reference solution.

NO inhibitory activity

NO, generated from sodium nitroprusside in a water-based physiological pH solution, combines with O2 to produce NO2-. The ions were measured using the Griess technique, as delineated by Marcocci et al.34,35,36. Incubation of the reactants was performed for 150 min at 25 °C. These included 3 ml of sodium nitroprusside (10 mM) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and the extract at concentrations of 10, 20, 40, 80 and 160 μg/ml. A 0.5 mL of the reaction mixture was extracted after incubation and then combined with 0.5 mL of Griess reagent. A wavelength of 546 nm was used to measure the absorbance.

Validation of the antioxidant methodologies has been reported in supplementary file 1.

Docking

Cytochrome c peroxidase structure (PDB ID: 2X08) was obtained from the Protein Data Bank. Heteroatoms and water molecules were removed using ArgusLab 4.0.1.37. Most abundant ligands of AETO-PHF that is, DDA and ODE, were downloaded from PubChem in SDF format. The 2X08 structure and were imported into PyRx, where target sites were defined by creating grid boxes at center coordinates; (X: − 11.924, Y: − 5.631, Z: 7.635). AutoDock Vina in PyRx was used in conducting the docking simulations38, and results were analyzed using Biovia Discovery Studio39. Re-docking allowed the positional validation of the co-crystallized ligand ASC within the 2X08 active site, which was achieved through Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) calculations. ASC was used as the reference antioxidant due to its known specificity for 2X08.

Dynamics simulation

Dynamics simulations of the CcP-CLA complex were performed with the Schrödinger suite40. Using the “System Builder” tool of the Desmond suite, a solvated system was built which was also neutralized with Na+ and Cl- . Energy minimization/simulations were performed with the Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations 3 (OPLS3) force field. Isothermal-isobaric (NPT) production ran for 200 ns at 310 K. Trajectory analysis evaluated the following: root mean square deviation (RMSD), radius of gyration (rGyr), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), polar surface area (PSA), solvent accessible surface area (SASA), molecular surface area (MolSA) and intramolecular hydrogen bonds (intra-HB).

Statistical analysis

A significance level of 5% was applied to determine which variations in the data are statistically meaningful. The significance was examined using one-way ANOVA Duncan multiple range test in SPSS version 22. The IC50 value was performed using pharmcalculator.github.io/enzyme-inhibition-IC50 online server.

Results and discussion

GC–MS profiling

GC analysis of the extract of the AETO-PHF is shown in Fig. 1, and the identified compounds are listed in Table 1.

The TRACE GC Ultra GC–MS system is efficient since it is quick, sensitive, and adaptable. These characteristics are essential for antioxidant studies, food quality assessment, and phytochemical exploration. It can quickly analyze natural antioxidants while maintaining precise and reliable results41,42.The GC–MS analysis of the AETO-PHF ethanol extract identified thirty-seven compounds, with dodecanoic acid (DDA, 16.24%) and 9-octadecenoic acid (Z)-, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester (ODE, 16.41%) as the major components. DDA is known to reduce cataract risk by boosting endogenous antioxidants and removing reactive oxygen species (ROS)43. ODE is an oleic acid glycerol ester. It is a more effective antioxidant because it is composed of a hydroxylated glycerol molecule and an unsaturated fatty acid43. The Z-conformation of the double bond in ODE enables more efficient electron or hydrogen transfer, which is essential for neutralizing free radicals such as DPPH and ABTS. Also, its hydroxyl groups offer multiple sites for hydrogen donation, enhancing its antioxidant activity44,45,46. ODE also has the ability to penetrate lipid membranes, helping to stabilize them and blocking lipid peroxidation, which is a major contributor to oxidative damage. Both DDA and ODE derivatives inhibit LDL oxidation and reduce malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, markers of oxidative stress47. The hydroxyl groups and ester components in ODE may also improve its solubility and bioavailability, further enhancing antioxidant effects. These findings align with previous studies on plant extracts and vegetable oils, where similar esters contributed strongly to total antioxidant activity48. Beyond antioxidant action, they influence cellular stress responses and growth regulation44,45.

Antioxidant Activity

The AETO-PHF antioxidant activities are reported in Figs. 2 (a–d) while the IC50 plot of AETO-PHF is shown in Fig. 2e.

Fig. 2 The results of antioxidant activity of AETO-PHF are provided in Figs. 2 a–d and were measured with the help of four tests, DPPH radical scavenging, H2O2 scavenging, FRAP and nitric oxide scavenging. The antioxidant ability of AETO-PHF increased with the dose, but it was noticeably lower (p < 0.05) than that of ASC and gallic acid. DPPH assay determines the ability of antioxidants to donate a hydrogen atom or an electron to convert DPPH free radicals to a neutral form46. In Fig. 2a, the results of AETO-PHF exhibited a definite trend whereby the highest concentrations were associated with the highest antioxidant activity. This trend is consistent with a number of plant extracts that have high DPPH scavenging activity47,48. It has been indicated in many studies that DPPH scavenging is an important indicator of antioxidant activity in vitro49,50. The antioxidant results in AETO-PHF are in agreement with other effective antioxidant extracts reported in literature51,52. H2O2 generates ROS which are able to form toxic hydroxyl radicals. The way an organism copes with H2O2 indicates its capacity to cope with oxidative stress. Effective peroxide neutralization is shown by the AETO-PHF activity (Fig. 2b), which lowers the risk of oxidative damage. In medicinal plants, the H2O2 scavenging activity has been reported to be excellent and this has been attributed to the role of antioxidants that can counteract peroxides53. Based on these results, it is possible to conclude that AETO-PHF may provide cellular protection against oxidative injury by H2O2. FRAP is used to measure the antioxidant capacity of a sample by quantifying the level of reduction of Fe3+ to Fe2+ by donating electrons. AETO-PHF ‘s strong FRAP activity indicates it ‘s highly effective at donating electrons, emphasizing its strong potential as a reducing agent. This observation concurs with a large number of studies in which plant extracts with high FRAP values possess large total antioxidant capacity, which is frequently attributed to polyphenol content54,55. Nitric oxide scavenging capacity is the capability to detoxify reactive nitrogen species that are associated with nitrosative stress and inflammation56. Hence, the high AETO-PHF activity implies the potential anti-inflammatory activity in addition to the known antioxidant activity57. Multiple studies support that the plant extracts with inhibitory effects on nitric oxide radicals are capable of preventing tissue damage and inflammation caused by nitric oxide and increasing their therapeutic significance58,59,60.

In the DPPH, H₂O₂, FRAP, and nitric oxide assays, the IC₅₀ values for AETO-PHF (61.39 ± 0.17, 11.15 ± 0.15, 61.75 ± 0.00, and 38.97 ± 2.66 µg/mL, respectively) did not show notable differences (P > 0.05) compared to the standard antioxidants (61.38 ± 0.58, 11.30 ± 0.84, 61.71 ± 0.20, and 38.94 ± 0.00 µg/mL). This similarity is illustrated in Fig. 2e. This suggests that AETO-PHF possesses comparable activity to these reference compounds in neutralizing oxidative agents. Given its strong performance and natural origin, AETO-PHF holds promising potential as a viable source of natural antioxidants for therapeutic or nutraceutical applications61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70.

Docking

The validity of molecular docking was tested by re-docking (co-crystallized ligand (ASC) into the same active site of the CcP and RMSD values of 0.4905 Å indicate that the docking experiment is valid71 (Fig. 3).

Cytochrome c peroxidase (CcP) is a useful enzyme for exploring antioxidant activity because it plays a key role in how cells defend themselves against oxidative stress. Specifically, it helps break down H2O2 into reactive oxygen species by using cytochrome c as the electron donor, making it a valuable model for studying antioxidant mechanisms72. The interaction between antioxidant compounds and CcP can give details about their activity in regulating or enhancing the performance of this enzyme and consequently countering the activity of ROS.

The 2D interactions of DDA, ODE and ASC with CcP are given in Figs. 4a–c.

Ligand docking of the ligands ODE and DDA to the protein target CcP gives valuable data concerning antioxidant activity. Both ODE and DDA have indicated higher binding affinity than the control antioxidant ASC (-5.5 kcal/mol), with the docking scores being -6.2 and -5.7 kcal/mol, respectively (Figs. 4a–c). More negative binding energies represent a greater binding affinity73; hence, ODE presents the best anticipated interaction with CcP amongst the three ligands analyzed in this paper. ODE stronger binding may be due to increased hydrophobicity and a closer fit in the pocket of CcP. ODE has a longer oleyl chain to offer more nonpolar interactions than DDA and ASC molecules. The moderate binding affinity of DDA (-5.7 kcal/mol) relative to the weaker interaction of ASC can be attributed to DDA ‘s capacity to form two hydrogen bonds and engage in multiple hydrophobic interactions, which collectively contribute to its stable positioning within the pocket. Other electrostatic interactions involving charged residues like ARG and LYS help strengthen the binding of DDA.

The slightly superior binding score ODE than DDA could be due to additional pi-alkyl interactions with aromatic residues. On the whole, hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic effect, and van der Waals forces combine to stabilize both ODE and DDA in the active site of the antioxidant protein. The interactions contribute to their ability to be effective antioxidants through strong binding to CcP and could affect its reactivity in the scavenging of reactive oxygen species or in the electron transfer pathways involved in the antioxidant reaction74. Although the binding affinity of the reference compound ASC is lower, it establishes several hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions, which agrees with its antioxidant properties. The fact that the binding energy of ASC is slightly less than that of ODE and DDA might be attributed to the small size of this compound restricting the number of hydrophobic contacts75,76,77. Important results indicate that ODE and DDA have a higher and more stable binding affinity to the CcP antioxidant enzyme due to a mixed interaction of hydrophobic, electrostatic, and hydrogen bonding. This is probably indicative of high antioxidant power. It has been observed that CcP is a redox-linked enzyme that has antioxidant effect. The docking analyses offer insight into the binding affinities, emphasizing how ligand interactions may contribute to antioxidant activity. These results are important for understanding the mechanisms behind the antioxidant effects.

MD simulation

RMSD of ODE-CcP complex, RMSF of CcP, RMSF of ODE-CcP complex, ODE-CcP contacts, ODE properties and torsion profile are shown in Fig. 5a–f, respectively.

200-ns simulations are sufficient to capture the equilibrium states and conformational changes in MD simulations78. A standard temperature of 300 K is normally used since it is easy to work with water models and make easier comparisons with experimental data although physiological temperatures are approximately 310 K78. The OPLS3 model enhances better protein–ligand binding predictions through refinement of torsional parameters and charge assignment 78. On the whole, such settings have a great beneficial effect on the reliability of biomolecular dynamics modeling.

Figure 5a presents the RMSD of the CcP protein backbone (C alpha, blue) and ligand ODE (red) during a 200 ns molecular dynamics (MD) of the CcP-ODE complex. The RMSD values that quantify structural stability show that CcP protein had moderate structural changes. The RMSD rose from 1.0 Å to approximately 2.6 Å and then stabilized at less than 3.0 Å which means that it did not change much in its overall structure. ODE initially showed flexibility up to ~ 5.0 Å but later stabilized at 3.0 Å. This shows changes in conformation in the binding site that resulted in a stable complex79,80.

The RMSF analysis (Fig. 5b) shows flexible regions of the protein, particularly at residues 70–90, 120–160, 176–190 and 200–225. Such adaptable loops would probably aid ligand recognition and binding flexibility, indicating they are possible hot spots of interaction81,82. The remaining protein, having RMSF less than 1.5 Å, is a structurally stable core of the protein that enables ligand binding. The observations indicate that the CcP ODE complex maintains energetic stability, as the ligand can preserve essential interactions by altering its conformation within the flexible regions of the protein. The antioxidant mechanism relies on stability at the atomic level, where the persistent binding of the ligand can considerably influence the biological activity of the protein81,82.

Figure 5c displays the RMSF profile of the ODE ligand in the CcP complex, which is 25 atoms long and shows variations mostly within 2.0–3.0 Å. Moderate flexibilities are also evident at some residues at locations 8, 15, 17, and 25 where they are likely to be caused by terminal regions or flexible side chains with minimal bonding interactions. In general, the values of RMSF show that the ligand mobility and stability are balanced because the interactions such as hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts eliminate excessive flexibility and hence stabilize the binding83,84. Figure 5d illustrates that the ODE ligand has moderate RMSD fluctuations stabilizing at 1.5 Å over the 200 ns simulation as would be expected in a stable protein–ligand complex. The Rgyr remains constant at about 4.4 Å, which signifies the maintenance of compactness of the proteins without major unfolding83,84. Low and transient intramolecular hydrogen bonding in the protein implies that there are small internal rearrangements but no impact on the overall structural integrity83,84. Other parameters, those that are complementary (MolSA), (SASA) and (PSA), exhibit minimal fluctuation and support the inference of a well-folded and stable complex83,84.

Figure 5e illustrates protein residue-ligand interactions and includes three key types of interactions: hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and π-stacking. Some of the key hotspots are residues TRP 51, ASP 149 and ASP 235 which play a major role in hydrogen bonding with ASP 235, LYS 149 and ASP 148. The binding is primarily restricted to a small number of residues and this is in line with the concepts of structural biology which dictates that certain amino acid residues are important in offering high-affinity ligand binding83,84.

The torsional profile of the ODE ligand (shown in Fig. 5f) reveals the differences between its free and restricted bond rotations. Rigid molecular segments are functionally significant and are stabilized by steric or non-covalent interactions, which are shown by sharp peaks in distributions of angles85. Smaller peaks indicate flexible regions capable of adopting new conformations. Torsional preference symmetry (± 180 ) indicates possible existence of conserved preferred conformations. The same structural preferences enable the ligand to adapt in the binding site and maintain significant functional motifs required to perform its antioxidant activity86.

MD simulation of ODE binding to CcP links to antioxidant activity via several important characteristics associated with functionality and ligand-binding interaction. CcP reduces hydrogen peroxide to form water, creating an essential enzymatic antioxidant activity that defends cells against oxidative injury by ROS. This enzymatic activity relies on a consistent interaction with substrates or ligands, enabling effective electron transfer and supporting catalysis centered around the heme group72. Molecular dynamics studies reveal that the complex that is stabilized between ODE and CcP is characterised by large binding interactions such as hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions and specific residue interactions which stabilise the enzyme-ligand complex. This stabilization aims to maintain the three-dimensional configuration of the enzyme ‘s active site, which is essential for preserving the integrity of its heme environment—important for its ability to function effectively as a peroxidase, supporting its role in antioxidant activity. The flexibility-rigidity balance in ligands in MD (RMSD, RMSF, torsional angle constraints) suggests that ODE can fit into the binding pocket of CcP, without destabilizing catalytically relevant regions. This flexibility can aid the electron and hydrogen transfer, which makes the reduction of peroxide effective, which is the basis of the antioxidant mechanism86. MD simulations of ODE and CcP suggest that maintaining a steady interaction between the ligand and specific protein residues—through energetic contacts—could enhance or sustain CcP ‘s antioxidant function. This stability appears to improve its structural features, which are key to reducing hydrogen peroxide levels and lowering oxidative stress. This study correlates the intermolecular interaction pattern at the molecular level, which is seen in molecular dynamics to mechanisms at the molecular level that promote antioxidant activity in the CcP system.

The docking stability explains how the ligand modulates CcP function, likely increasing the enzyme ‘s ability to scavenge ROS at the cellular level, which matches the antioxidant activity seen in vitro. Compounds with strong docking affinity to CcP may enhance ROS neutralization by protecting and boosting the enzyme ‘s antioxidant function. This stable binding suggests a direct role in strengthening the body ‘s natural antioxidant defenses, supporting the observed biological effects. Computational data therefore reinforce laboratory findings by showing that the stable complex between CcP and ODE improves enzyme performance in reducing oxidative stress. This confirms that ODE ‘s antioxidant activity seen under controlled conditions reflects underlying molecular mechanisms, which computational models revealed. Together, these results demonstrate the complementary nature of experimental and computational approaches in understanding antioxidant actions and guiding the design of more effective ODE derivatives.

Conclusion

A new approach to the polyherbal formulation derived from A. esculentus and T. occidentalis was studied through a combination of chemical analysis, laboratory antioxidant testing, and computer-based simulations. The GC–MS analysis identified a variety of bioactive compounds with known antioxidant properties, confirming the unique chemical makeup and potential health benefits of this plant mixture. In vitro tests showed strong antioxidant activity, demonstrating the preparation ‘s effectiveness in neutralizing harmful free radicals. Molecular dynamics simulations revealed that the key compound (ODE) forms stable and flexible interactions with a key enzyme, explaining how the preparation helps maintain the enzyme ‘s function under oxidative stress.

This research is original in integrating approach that links the identification of active phytochemicals, confirmation of antioxidant effects, and a clear explanation of how these effects occur at the molecular level. This approach validates traditional uses of these plants and provides insight into the complex interactions responsible for their antioxidant action. The findings suggest that this preparation has potential as a natural therapeutic agent against diseases caused by oxidative stress, working through protein–ligand interactions to modulate key biological pathways.

Future research should include in vivo studies to evaluate absorption, safety, and therapeutic efficacy. Clinical trials will be necessary to establish appropriate dosing and confirm effectiveness in humans. Further exploration of how different phytochemicals work together, along with optimizing the formulation, could improve its healing potential. Expanding computational studies to include other relevant antioxidant enzymes and pathways will deepen understanding and assist in developing even better natural antioxidants. This work emphasizes the value of combining experimental and computational techniques to fully understand and develop plant-based treatments for oxidative stress-related conditions.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

References

Pizzino, G., Irrera, N. & Cucinotta, M. Oxidative stress: Harms and benefits for human health. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 8416763 (2017).

Reddy, V. P. Oxidative stress in health and disease. Biomedicines 11, 2925 (2023).

Cheignon, C. et al. Oxidative stress and the amyloid beta peptide in Alzheimer ‘s disease. Redox Biol. 14, 450–464 (2018).

García-Sánchez, A., Miranda-Díaz, A. G. & Cardona-Muñoz, E. G. The role of oxidative stress in physiopathology and pharmacological treatment with pro- and antioxidant properties in chronic diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2082145 (2020).

Ji, L. L. & Yeo, D. Oxidative stress: An evolving definition. Fac Rev. 10, 13 (2021).

Kapgate, R. R. et al. Review on polyherbal syrup for various pharmacological activities. Human J. 26, 421–435 (2020).

Aladejana, E. & Aladejana, A. Hepatoprotective activities of polyherbal formulations: A systematic review. J. Med. Plants Eco. Dev. 7, 1–22 (2023).

Satish, D. & Ashwini, K. D. Preclinical evidence of polyherbal formulations on wound healing: A systematic review on research trends and perspectives. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 14, 100688 (2023).

Gaonkar, V. P. & Hullatti, K. Indian traditional medicinal plants as a source of potent anti-diabetic agents: A review. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 19, 1895–1908 (2020).

Mochahary, B., Middha, S. K., Usha, T. B. N. N. & Goyal, A. K. Evaluating hepatoprotective activity of polyherbal formulations-an overview of dietary antioxidants. Plant Sci. Today 10, 180–187 (2023).

Alhamhoom, Y. et al. Synergistic antihyperglycemic and antihyperlipidemic effect of polyherbal and allopolyherbal formulation. Pharma 16, 1368 (2023).

Parasuraman, S., Thing, G. S. & Dhanaraj, S. A. Polyherbal formulation: Concept of Ayurveda. Phcog. Rev. 8, 73–80 (2014).

Tomelleri, M. Synergistic effects of polyherbal formulations in traditional and modern medicine. Pharm. Lett. 16, 9–10 (2024).

Karole, S. et al. Polyherbal formulation concept for synergic action: A review. J. Drug Delivery Ther. 9, 453–466 (2019).

Dubey, S. & Dixit, A. K. Preclinical evidence of polyherbal formulations on wound healing: A systematic review on research trends and perspectives. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 14, 100688 (2023).

Rana, S., Badola, A. & Agarwal, V. Polyherbal formulations: New emerging technology in herbal remedies. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Manag. 4, 728–732 (2022).

Borokini, F. B., Oladipo, G. O., Komolafe, O. Y. & Ajongbolo, K. F. Phytochemical nutritional and antioxidant properties of Abelmoschus esculentus Moench L. leaf: a pointer to its fertility potentials. Measur. Food 6, 100034 (2022).

Abdel-Razek, M. A. M., Abdelwahab, M. F., Abdelmohsen, U. R. & Hamed, A. N. E. A review: pharmacological activity and phytochemical profile of Abelmoschus esculentus (2010–2022). RSC Adv. 13, 15280–15294 (2023).

Chaudhari, Y., Kumar, E. P., Badhe, M., Mody, H. R. & Acharya, V. B. An evaluation of antibacterial activity of Abelmoschus esculentus on clinically isolated infectious disease causing bacterial pathogen from hospital. Int. J. Pharm. Phytopharmacol. Res. 1, 107–111 (2011).

Kayode, A. A. A. & Kayode, O. T. Some medicinal values of Telfairia occidentalis: A review. Am. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1, 30–38 (2011).

Aworunse, O. S., Bello, O. A., Popoola, J. O. & Obembe, O. O. Pharmacotherapeutic properties of Telfairia occidentalis Hook F.: A systematic review. Pharmacogn. Rev. 12, 238–249 (2018).

Ikpeazu, O. V., Otuokere, I. E. & Igwe, K. K. Preliminary studies on the secondary metabolites of Buchholzia coriacea (wonderful kola) seed ethanol extract by GC-MS analysis. Int. J. Res. Engr. Appl. 7, 17–26 (2017).

Ikpeazu, O. V., Otuokere, I. E. & Igwe, K. K. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometric analysis of bioactive compounds present in ethanol extract of Combretum hispidum (Laws) (Combretaceae) root. Comm. Phys. Sci. 5, 325–337 (2020).

Ikpeazu, O. V., Otuokere, I. E. & Igwe, K. K. GC–MS analysis of bioactive compounds present in ethanol extract of Combretum hispidum (Laws) (Combretaceae) leaves. Int. J. Trend Sci. Res. Dev. 4, 307–313 (2020).

Otuokere, I. E., Amaku, F. J., Igwe, K. K. & Bosah, C. A. Characterization of Landolphia dulcis ethanol extract by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis. Int. J. Adv. Engr. Techn. Sci. 2, 13–17 (2016).

Otuokere, I. E. et al. GC-MS profiling and in silico studies to identify potential SARS-CoV-2 nonstructural protein inhibitors from Psidium guajava. Afri. Sci. Rep. 1, 161–173 (2022).

Otuokere, I. E. et al. GC-MS analysis and molecular docking studies to identify potential SARS-CoV-2 nonstructural protein inhibitors from Icacina trichantha Oliv tubers. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 6, 1336–1342 (2022).

Nwankwo, C. I. et al. Phenolics of Abelmoschus esculentus pods: HPLC identification and in silico studies to identify potential anti-inflammatory agents. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 6, 1311–1319 (2022).

Elwekeel, A. et al. Anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, GC-MS profiling and molecular docking analyses of non-polar extracts from five Salsola species. Separations 10, 72 (2023).

Otuokere, I. E., Iheanyichukwu, J. I. & Mac-kalunta, O. M. Network pharmacology and molecular docking to reveal the pharmacological mechanisms of Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench in treating breast cancer. Silico Pharmacol. 13, 40 (2025).

Sankeshwari, R. M., Ankola, A. V., Bhat, K. & Hullatti, K. Soxhlet versus cold maceration, which method gives better antimicrobial activity to licorice extract against Streptococcus mutans?. J. Sci. Soc. 45, 67–71 (2018).

Egbucha, J. N., Johnbull, O. E., Igwe, O. U. & Otuokere, I. E. Isolation and characterization of a novel tertiary substituted amine from the leaves of Sarcophrynium brachystachys. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 7, 3502–3507 (2023).

Zhang, X. Y. Principles of chemical analysis (China Science Press, 2000).

Marcocci, L., Maguire, J. J., Droy-Lefaix, M. T. & Packer, L. The nitric oxide-scavenging properties of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 201, 748–755 (1994).

Kingori, S., Cheruiyot, S., Kirui, A., Uwamahoro, R. & Mwangi, A. Optimization and validation of a simple spectrophotometric based DPPH method for analysis of antioxidant activity in aerated, semi-aerated and non-aerated tea products. Open J. Appl. Sci. 14, 2207–2222 (2024).

Camila, P. R., Silvia, M., Josefa, H., Asta, T. & José, J. C. Analytical validation of an automated assay for ferric-reducing ability of plasma in dog serum. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 29, 574–578 (2017).

Thompson, M. A. Molecular docking using ArgusLab, an efficient shape-based search algorithm and the AScore scoring function. ACS Meeting Philadelphia 172, 42 (2004).

Dallakyan, S. & Olson, A. J. Small-molecule library screening by docking with PyRx. In: Chemical Biology. New York: Springer, pp. 243–250 (2015).

Dassault Systèmes. BIOVIA, Discovery Studio (2021).

Schrödinger Release. 2024–1: BioLuminate, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY (2024).

Gomathi, D., Kalaiselvi, M., Ravikumar, G., Devaki, K. & Uma, C. GC-MS analysis of bioactive compounds from the whole plant ethanolic extract of Evolvulus alsinoides (L.) L. J. Food Sci. Technol. 52, 1212–1217 (2015).

Naz, R. et al. GC-MS analysis, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antilipoxygenase and cytotoxic activities of Jacaranda mimosifolia methanol leaf extracts and fractions. PLoS ONE 15, e0236319 (2020).

Luo, J., Xu, J., Yang, Y., Li, D. & Qiu, H. The negative association between dodecanoic acid intake and cataract incidence based on NHANES 2005–2008 (2025).

Nazir, N., Zahoor, M., Uddin, F. & Nisar, M. Chemical composition, in vitro antioxidant, anticholinesterase, and antidiabetic potential of essential oil of Elaeagnus umbellata Thunb. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 21, 73 (2021).

Youssef, A. M. M., Maaty, D. A. M. & Al-Saraireh, Y. M. Phytochemical analysis and profiling of antioxidants and anticancer compounds from Tephrosia purpurea (L.) subsp apollinea family Fabaceae. Molecules 28, 3939 (2023).

Ali Reza, A. S. M. et al. Antiproliferative and antioxidant potentials of bioactive edible vegetable fraction of Achyranthes ferruginea Roxb. in cancer cell line. Food Sci. Nutr. 9, 3777–3805 (2021).

Uysal, D. I. et al. Antioxidant effects and fatty acid analysis of Leucojum aestivum seed coat extracts. Period. Polytech. Chem. Eng. 68, 409–418 (2024).

Kim, B. R. et al. Composition and activities of volatile organic compounds in radiation-bred Coreopsis cultivars. Plants 9, 717 (2020).

Baliyan, S., Mukherjee, R. & Priyadarshini, A. Determination of antioxidants by DPPH radical scavenging activity and quantitative phytochemical analysis of Ficus religiosa. Molecules 27, 1326 (2022).

Mokoroane, K. T., Pillai, M. K. & Magama, S. 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity of extracts from Aloiampelos striatula. Food Res. 4, 2062–2066 (2020).

Gawron-Gzella, A., Dudek-Makuch, M. & Matławska, I. DPPH radical scavenging activity and phenolic compound content in different leaf extracts from selected blackberry species. Acta Biol. Cracov. Ser. Bot. 54, 32–38 (2012).

Fugaban-Hizon, C. DPPH scavenging activity of Ficus septica leaf ethanolic extract. Bull. Env. Pharmacol. Life Sci. 11, 23–26 (2022).

Hwang, S. J. & Lee, J. H. Comparison of antioxidant activities expressed as equivalents of standard antioxidant. Food Sci. Technol. Campinas 43, e121522 (2023).

Yousaf, H. Evaluation and comparison of the antioxidant and free radical scavenging properties of medicinal plants by using the DPPH assay in-vitro. bioRxiv (2023).

Aryal, S. et al. Total phenolic content, flavonoid content and antioxidant potential of wild vegetables from Western Nepal. Plants 8, 96 (2019).

Sreedevi, P. & Vijayalakshmi, K. Determination of antioxidant capacity and gallic acid content in ethanolic extract of Punica granatum L. leaf. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 11, 319–323 (2018).

Hasimun, P., Sulaeman, A. & Maharani, I. D. P. Supplementation of Carica papaya leaves (Carica papaya L.) in nori preparation reduced blood pressure and arterial stiffness on hypertensive animal model. J. Young Pharm. 12, 113–117 (2020).

Sumagaysay, M. A. Z., Abrio, S. & Balindong, H. A. T. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of the crude ethanolic extract from the bark of Cinnamomum mercadoi. GSC Biol. Pharm. Sci. 28, 150–155 (2024).

Fernando, C. D. & Soysa, P. Optimized enzymatic colorimetric assay for determination of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) scavenging activity of plant extracts. MethodsX 2, 283–291 (2015).

Al-Amiery, A. A., Al-Majedy, Y. K., Kadhum, A. A. & Mohamad, A. B. Hydrogen peroxide scavenging activity of novel coumarins synthesized using different approaches. PLoS ONE 10, e0132175 (2015).

Salamah, N., Ahda, M., Bimantara, S. & Hanar, R. Total phenolic content and in vitro evaluation of antioxidant activity of ethanol extract of Ganoderma amboinense. Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 8, 97–101 (2018).

Ab Rahim, N., Zakaria, N., Habib Dzulkarnain, S. M., Mohd Azahar, N. M. Z. & Abdulla, M. A. Antioxidant activity of Alstonia angustifolia ethanolic leaf extract. AIP Conf. Proc. 1891, 020012 (2017).

Edward, J. & Padmaja, V. Antioxidant potential of ethanolic extract of aerial parts of Coleus spicatus Benth Jaslin. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 10, 12054–12057 (2011).

Din, W. M. et al. Antioxidant and cytoprotective effects of an ethanol extract of Acalypha wilkesiana var. macafeana from Malaysia. Nat. Prod. Commun. 8, 375–380 (2013).

Etim, O. E., Ekanem, S. E. & Sam, S. M. In vitro antioxidant activity and nitric oxide scavenging activity of Citrullus lanatus seeds. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 3, 126–132 (2013).

Thida, M., Mya, K. M., Nyein, C. M., Chan, K. N. & Lwin, W. W. Comparative study of free radical scavenging potential of selected Myanmar medicinal plants. Int. J. Adv. Res. Publ. 105, 105–109 (2018).

Roghini, R. & Vijayalakshmi, K. Free radical scavenging activity of ethanolic extract of Citrus paradisi and naringin—An in vitro study. Int. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. Res. 10, 11–16 (2018).

Patel, R. M. & Patel, N. J. In vitro antioxidant activity of coumarin compounds by DPPH, super oxide and nitric oxide free radical scavenging methods. J. Adv. Pharm. Educ. Res. 1, 52–68 (2011).

Rizwana, S. et al. Evaluation of antioxidant, free radical scavenging, and antimicrobial activity of Quercus incana Roxb. Front. Pharmacol. 6, 277 (2015).

Jagetia, G. C. & Baliga, M. S. The evaluation of nitric oxide scavenging activity of certain Indian medicinal plants in vitro: A preliminary study. J. Med. Food 7, 343–348 (2004).

Gheidari, D., Mehrdad, M. & Karimelahi, Z. Virtual screening, ADMET prediction, molecular docking, and dynamic simulation studies of natural products as BACE1 inhibitors for the management of Alzheimer ‘s disease. Sci. Rep. 14, 26431 (2024).

Campos, E. G., Hermes-Lima, M., Smith, J. M. & Prichard, R. K. Characterisation of Fasciola hepatica cytochrome c peroxidase as an enzyme with potential antioxidant activity in vitro. Int. J. Parasitol. 29, 655–662 (1999).

RoyBatty. How to interpret the affinity in a protein docking - ligand. mattermodeling.stackexchange.com (2021).

Shebriya, A. & Santhy, K. S. Insilico approach in the identification of chemotherapeutical lead compounds from Semecarpus anacardium L. F related to apoptotic pathway proteins. J. Xi ‘an Shiyou Univ. 1, 1–13 (2021).

Chen, K. & Kurgan, L. Investigation of atomic level patterns in protein-small ligand interactions. PLoS ONE 4, e4473 (2009).

Panigrahi, S. K. Strong and weak hydrogen bonds in protein-ligand complexes of kinases: A comparative study. Amino Acids 34, 617–633 (2008).

Cornell, C. E. et al. Prebiotic amino acids bind to and stabilize prebiotic fatty acid membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 17239–17244 (2019).

Philipp, J. & Christina, K. Structure-based prediction of Ras-effector binding affinities and design of “branchegetic” interface mutations. Structure 31, 870-883.e5 (2023).

Dhivyadharshini, G. et al. Molecular docking analysis of chlorogenic acid against matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 10, 6865–6873 (2020).

Mohammad, T., Gholamreza, M., Naderi, M. & Hosseini, S. Protein–chlorogenic acid interactions: Mechanisms, characteristics, and potential food applications. Antioxid. 13, 777 (2024).

Cournia, Z., Allen, B. & Sherman, W. Relative binding free energy calculations in drug discovery: Recent advances and practical considerations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 57, 2911–2937 (2017).

Patil, S. B. & Gadad, P. C. Elucidation of intermolecular interactions between chlorogenic acid and glucose-6-phosphate translocase: A step towards chemically induced glycogen storage disease type 1b model. Biotech 13, 250 (2023).

Gheidari, D., Mehrdad, M. & Hoseini, F. Virtual screening, molecular docking, MD simulation studies, DFT calculations, ADMET, and drug likeness of Diaza-adamantane as potential MAPKERK inhibitors. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1360226 (2024).

Mahmoodi, N., Bayat, M., Gheidari, D. & Sadeghian, Z. In silico evaluation of cis-dihydroxy-indeno[1,2-d]imidazolones as inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3: Synthesis, molecular docking, physicochemical data, ADMET, MD simulation, and DFT calculations. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 28, 101894 (2024).

Patrick, C. A. Dihedral angle measurements for structure determination by biomolecular solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 8, 791090 (2021).

Stein, E. G., Rice, L. M. & Brünger, A. T. Torsion-angle molecular dynamics as a new efficient tool for NMR structure calculation. J. Magn. Reson. 124, 154–164 (1997).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, C.I.N and I.E.O; Investigation, J.I.I., and C.M.N; Methodology, O.M.M. Software, J.N.E, Visualization, I.E.O; writing—original draft preparation, G.B.V., N.E.U. and K.K.I. All authors made revisions to the final version and approved its publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and informed consents

The research does not involve human subjects or animals. Therefore, no ethical approval or consent was required for this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nwankwo, C.I., Otuokere, I.E., Iheanyichukwu, J.I. et al. In vitro and in silico evaluation of synergistic antioxidant potential in a polyherbal formulation from Abelmoschus esculentus and Telfairia occidentalis. Sci Rep 15, 44771 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28672-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28672-5