Abstract

Postprandial plasma glucose between 4 and 7.9 h is associated with the diagnosis of diabetes, diabetes mortality, and cardiovascular mortality. However, it is unknown whether 2-hour plasma glucose during the oral glucose tolerance test conducted in this postprandial period (4–7.9 h), termed as 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h, can accurately classify diabetes diagnosis and predict mortality risks. This study aimed to address these questions using 2,347 adult participants. Diabetes was defined as HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, and the ability of 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h to classify diabetes was analyzed using receiver operating characteristic curves. Cox proportional hazards models were employed to estimate mortality hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The results showed that 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h could classify diabetes with 92% accuracy. Participants were followed up for a mean of 21.4 years. A 1-square-root higher 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h was associated with an increased risk of mortality from all causes (adjusted HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04–1.08), diabetes (adjusted HR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.33–1.61), and cardiovascular disease (adjusted HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.03–1.11). In conclusion, 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h, a non-fasting test, may be useful for diabetes classification and prediction of mortality risk from diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes is a metabolic disease characterized by elevated blood glucose levels1. As of 2021, approximately 529 million people worldwide were living with diabetes, a number projected to rise to 1.31 billion by 20502. This condition contributes to about 1.5 million deaths annually3. It imposes a substantial economic burden, costing $1.3 trillion globally in 2015, which figure is estimated to climb to around $2.2 trillion by 20304.

In 2021, about half of diabetic cases in adults remained undiagnosed5. Those with undiagnosed diabetes are developing diabetes-related complications, leading to increased healthcare expenditure6. Individuals with undiagnosed diabetes face a 60% higher risk of mortality compared to those without diabetes7. Timely diagnosis is crucial for initiating appropriate medical interventions to prevent or delay diabetes-related complications8. Therefore, enhanced efforts are needed to improve diabetes detection.

Currently, diabetes diagnosis relies on fasting plasma glucose levels, 2-h plasma glucose during an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)9. However, fasting requirements for tests such as fasting plasma glucose and OGTT can be inconvenient and may induce hypoglycemia in vulnerable individuals10. Exploring the diagnostic potential of non-fasting plasma glucose and non-fasting OGTT could therefore offer valuable insights.

Recent research highlights postprandial glucose levels measured between 4 and 7.9 h after a meal (PPG4–7.9 h) as a promising biomarker for diagnosis. Computed PPG4–7.9 h demonstrates an 87% accuracy in diagnosing diabetes11, falling within the optimal accuracy range of 80% to 90%12. Moreover, PPG4–7.9 h has been linked to predicting mortality from diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD)13, and cancer14. Importantly, it remains stable throughout this postprandial period, as evidenced by consistent hourly measurements13,15.

Supporting this finding, Eichenlau et al.‘s study showed that plasma glucose returned to baseline levels within 4 h after a meal, regardless of meal type (standard meal or high carbohydrate meal) and meal time (breakfast, lunch or dinner) in healthy individuals16. These clinical results underscore the potential of the postprandial period between 4 and 7.9 h to reflect an individual’s glucose homeostasis state, offering a promising window for diabetes diagnosis.

Yet, the diagnostic and prognostic value of 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT conducted within this postprandial period between 4 and 7.9 h (2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h) remains unknown. This study aimed to explore whether 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h was associated with diabetes diagnosis and predicted mortality risks. It utilized data from 2,347 adult participants who attended the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) during 1988–1994. Additionally, 3,865 participants from the same survey with 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT conducted in the fasting period (fasting time ≥ 8 h9,17,18), termed as 2-h PGOGTT@fasting, were included in the analysis.

Methods

Participants

This study included adult participants (aged ≥ 20 years) from NHANES III (1988–1994)19. Two cohorts of participants were selected from the participants: the postprandial cohort (fasting time, 4–7.9 h) and the fasting cohort (fasting time, ≥ 8 h9,17,18).

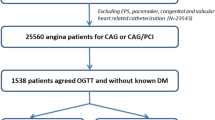

The postprandial cohort included all participants who had 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT conducted in the postprandial period between 4 and 7.9 h (n = 2410). This 2-h plasma glucose was termed as 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h. Participants missing follow-up time or with a follow-up of 0 months (n = 2) were excluded. Individuals who lacked the following data were also excluded: HbA1c (n = 13), body mass index (n = 4), systolic blood pressure (n = 4), total cholesterol (n = 21), and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (n = 19). Therefore, the remaining 2347 participants were included in the final analysis for the postprandial cohort (Fig. 1).

Flow diagram of the study participants. 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h, 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT conducted in the postprandial period between 4 and 7.9 h; 2-h PGOGTT@fasting, 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT conducted in the fasting period (fasting time, ≥ 8 h); BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; NHANES III, the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; PG, plasma glucose; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

The fasting cohort included all participants who had 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT conducted in the fasting period (fasting time, ≥ 8 h; n = 3961). The 2-h plasma glucose in this cohort was termed as 2-h PGOGTT@fasting. Participants missing follow-up time or with a follow-up of 0 months (n = 2) were excluded. Individuals who lacked the following data were also excluded: HbA1c (n = 16), body mass index (n = 5), systolic blood pressure (n = 4), total cholesterol (n = 41), and HDL cholesterol (n = 28). Therefore, the remaining 3865 participants were included in the final analysis for the fasting cohort (Fig. 1).

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the NHANES Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent. All participant records were anonymised prior to being accessed by the authors.

Exposure variable

The exposure variable of this study was 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT which was conducted in the postprandial period between 4 and 7.9 h or in the fasting period (fasting time, ≥ 8 h9,17,18). During the OGTT test, participants were administered a glucose challenge containing the equivalent of 75 g of glucose20. Two hours later, a blood specimen was drawn to measure 2-h plasma glucose levels using the hexokinase method21,22.

Outcome variables

The outcome variables of this study were HbA1c, diabetes diagnosis, and various types of mortality.

HbA1c was measured using the Bio-Rad DIAMAT glycosylated hemoglobin analyzer system21. Currently, diabetes in the clinic is diagnosed using HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose and 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT which was conducted in the fasting period. However, participants in the postprandial cohort lacked fasting plasma glucose and OGTT that was conducted in the fasting period. Therefore, diabetes in the current study was defined as HbA1c ≥ 6.5 only in the main analyses. Diabetes was also defined as a self-reported diagnosis in additional analyses.

Data on mortality from diabetes, CVD, cancer, and all causes were directly retrieved from NHANES-linked mortality files19. To evaluate mortality status and the cause of death, the National Center for Health Statistics linked the NHANES data with death certificate records from the National Death Index records23. Follow-up time was the duration from the time when the individual was examined at the Mobile Examination Center until death or until the conclusion of follow-up (31 December 2019), whichever occurred first24.

Covariables

Covariables were described previously11,15 and included age, sex (female or male), ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other), body mass index, poverty–income ratio (< 130%, 130%–349%, ≥ 350%, or unknown), education (< high school, high school, > high school, or unknown), smoking status (current smoker, past smoker, or non-smoker), alcohol consumption (never, < 1 drink per week, 1–6 drinks per week, ≥ 7 drinks per week, or unknown), physical activity (inactive, insufficiently active, or active), survey periods (1988–1991 or 1991–1994), systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and family history of diabetes (yes, no, or unknown).

Statistical analyses

The baseline characteristics of these two cohorts of participants were presented as median and interquartile range for not normally distributed continuous variables, mean and standard deviation for normally distributed continuous variables, or number and percentage for categorical variables25. Differences in continuous variables were analyzed via the Mann-Whitney U test (not normally distributed)26 and Student’s T-test (normally distributed)27, and differences among categorical variables were analyzed via Pearson’s chi-square test28.

The associations of 2-h plasma glucose with HbA1c and diabetes diagnosis were analyzed by multiple linear regression and binary logistic regression29,30, respectively. Receiver operating characteristic curves were constructed and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to assess the association of 2-h plasma glucose with diabetes diagnosis and mortality31, and the Youden Index was used to determine the optimal cutoff32.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of 2-h plasma glucose for mortality from diabetes, CVD, cancer, and all causes. 2-h plasma glucose was treated as a continuous variable (natural log-transformed) or categorical variable (≥ versus < 200 mg/dL, or < 140 versus ≥ 140 & <200 mg/dL). Kaplan–Meier curves were constructed to estimate the survival rates of participants between the two 2-h plasma glucose categories (≥ versus < 200 mg/dL), which were compared using the log-rank test33. To improve data distribution, body mass index, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and systolic blood pressure were natural log-transformed and 2-h plasma glucose was square root-transformed in all the regression analyses34.

Power estimation was conducted by simulations employing 10,000 randomly generated samples with various sample sizes (ranging from 50 to 200) derived from the postprandial cohort of 2347 participants35,36. Diabetes prediction was defined as a 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h ≥ 200 mg/dL, and actual diabetes status was defined as HbA1c ≥ 6.5%37. Within each sample, the diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h for diabetes diagnosis were then calculated38,39,40.

A diagnostic accuracy of 80%, which is deemed a minimum threshold for an excellent diagnostic marker12, was used for power estimation. The percentage of samples exhibiting ≥ 80% accuracy out of 10,000 random samples was assigned as the diagnostic power of 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h in classifying diabetes. Mean sensitivity and specificity values were calculated from the 10,000 samples, and their 95% confidence intervals were generated from the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the 10,000 sensitivity and specificity values41. In addition, a diagnostic accuracy of 81% was also used to estimate power and sample size.

The null hypothesis was rejected for two-sided values of p < 0.05. The estimation of power and sample size were conducted using the R program, and the remaining analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, NY, USA, IBM Corporation)42.

Results

Baseline characteristics

This study included two cohorts of participants: the postprandial cohort (fasting time, 4–7.9 h; n = 2347) and the fasting cohort (fasting time, ≥ 8 h; n = 3865). Both cohorts had a mean age of 56 years. Participants with higher 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT were older, and had higher levels of HbA1c, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, and total cholesterol, and had lower levels of HDL-cholesterol, education, and income (Supplementary Tables S1-S2 online).

Association of 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT with HbA1c

2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h was positively associated with HbA1c without adjustment (Model 1, β = 0.614, p < 0.001, Supplementary Table S3 online). This association remained significant after adjustment for all the tested confounders (Model 6, β = 0.606, p < 0.001, Supplementary Table S3). Similarly, 2-h PGOGTT@fasting was positively associated with HbA1c in the absence (β = 0.671) and presence of adjustment (β = 0.650, Supplementary Table S3 online).

Association of 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT with diabetes diagnosis

A 1-square-root increase in 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h was associated with a higher risk of HbA1c-diagnosed diabetes after adjustment for all the tested confounders (Model 6; OR = 2.44; 95% CI, 2.19–2.73; p < 0.001; Table 1). 2-h PGOGTT@fasting was associated with HbA1c-diagnosed diabetes to a similar extent (Model 6; OR = 2.49; 95% CI, 2.28–2.71; p < 0.001; Table 1).

ROC curve analysis showed that 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h predicted HbA1c-diagnosed diabetes with an accuracy of 92% as indicated by the AUC value, and the accuracy for 2-h PGOGTT@fasting was 95% (Fig. 2). The optimal cutoff for 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h to predict HbA1c-diagnosed diabetes was 206.8 mg/dL, and the corresponding cutoff for 2-h PGOGTT@fasting was 203.6 mg/dL (Fig. 2).

ROC curves of 2-h plasma glucose to classify diabetes, defined as HbA1c ≥ 6.5%. (A) OGTT was conducted in the postprandial period between 4 and 7.9 h. The optimal cutoff was 206.8 mg/dL, with a sensitivity of 84.8%, specificity of 86.1%, and an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.92. (B) OGTT was conducted in the fasting period (fasting time, ≥ 8 h). The optimal cutoff was 203.6 mg/dL, with a sensitivity of 85.8%, specificity of 93.1%, and an AUC of 0.95. HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

In further analyses, we defined diabetes as a self-reported diagnosis. The results showed that both 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h and 2-h PGOGTT@fasting remained significantly associated with diabetes diagnosis (Supplementary Table S4 and Supplementary Figure S1).

Association of 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT with Pre-diabetes diagnosis

Prediabetes was defined as HbA1c ranging between 5.7% and 6.4%. A 1-square-root increase in 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h was associated with a 13% increased risk of pre-diabetes diagnosis after adjustment for all the tested confounders (Model 6; OR, 1.13.1; 95% CI, 1.07–1.19; p < 0.001; Supplementary Table S5 online). When 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT was treated as a dichotomous variable using the cut off of 140 mg/dL, those with 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h ≥140 mg/dL had a 29% higher risk of pre-diabetes diagnosis after adjustment for all the tested confounders (Model 6; OR, 1.29.1; 95% CI, 1.04–1.60; p = 0.021; Table 2). As expected, 2-h PGOGTT@fasting was associated with a higher risk of HbA1c-defined pre-diabetes.

Association of 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT with diabetes mortality

The postprandial cohort was followed up for 50,185 person-years with a mean follow-up of 21.4 years. The fasting cohort was followed up for 82,039 person-years with a mean follow-up of 21.2 years. During the follow-up, diabetes led to 40 and 62 deaths in the postprandial and the fasting cohorts, respectively (Supplementary Table S6).

A 1-square-root increase in 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h was associated with a 46% increase in diabetes mortality risk after adjustment for all the tested confounders (Model 6; HR, 1.46.1; 95% CI, 1.33–1.61; p < 0.001; Table 3). A 1-square-root increase in 2-h PGOGTT@fasting was associated with a 29% increase in diabetes mortality risk after adjustment for all the tested confounders (Model 6; HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.21–1.38; p < 0.001; Table 3).

Further analysis was conducted by treating 2-h plasma glucose as a categorical variable using the clinical cutoff of 200 mg/dL. The Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that those with 2-h plasma glucose of ≥ 200 mg/dL (versus < 200 mg/dL) had an increased risk of diabetes mortality in both cohorts (p < 0.001, Supplementary Figure S2). The positive association remained after further adjustment for all the tested confounders (Supplementary Table S7).

Association of 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT with All-Cause mortality, CVD mortality, and cancer mortality

We further analyzed the association of 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h with mortality from all causes and CVD. The results showed that a 1-square-root increase in 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h was associated with a 6% increase in multivariable-adjusted risk of all-cause mortality (Model 6; HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04–1.08; p < 0.001; Table 4) and a 7% increase in multivariable-adjusted risk of CVD mortality (Model 6; HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.03–1.11; p < 0.001; Table 5). 2-h PGOGTT@fasting predicted mortality from all causes and CVD to a similar extent (Tables 4 and 5). In addition, neither 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h nor 2-h PGOGTT@fasting was independently associated with cancer mortality (Supplementary Table S8).

Further analyses were conducted to characterize the association between 2-h plasma glucose during OGTT with mortality. 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h and 2-h PGOGTT@fasting remained positively associated with higher risk for all-cause mortality and diabetes mortality after further adjustment for HbA1c (Table 6). However, the positive association between 2-h plasma glucose and CVD mortality disappeared after this adjustment (Table 6). In addition, ROC curve analysis showed that the optimal cutoffs were 203.5 and 139.9 mg/dL, respectively, for 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h to classify diabetes mortality and CVD mortality (Supplementary Figures S3 & S4 online). Moreover, further analyses found that fasting status per se (4–7.9 h vs. ≥ 8 h) was not associated with mortality risks (Supplementary Table S9 online).

Power and sample size estimation for 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h to diagnose diabetes

The current study has a limitation in evaluating the diagnostic utility of 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h within the postprandial cohort. In this analysis, diabetes was defined based on HbA1c ≥ 6.5% or self-reported diagnosis, as fasting plasma glucose and standard fasting OGTT data were not available for this cohort. To rigorously assess the diagnostic utility of 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h, future studies should be designed to incorporate all standard diabetes diagnostic parameters alongside the 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h measurement. Sample size estimation will be essential to ensure sufficient statistical power for these investigations.

Power analysis for using 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h to diagnose diabetes was conducted through the simulation of 10,000 random samples, and each simulation had a certain sample size ranging from 50 to 200 participants.

A diagnostic accuracy from 80% to 90% is considered excellent12. This study employed an accuracy threshold of 80% to conduct power and sample size estimations. Additionally, a slightly improved accuracy of 81% was also explored for these estimations (Supplementary Table S10). The findings suggested that a sample size of 100 participants may be necessary to achieve over 80% power in detecting a diagnostic accuracy of 81% using 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h in future studies (Supplementary Table S10).

Discussion

Using a cohort of US adults (n = 2347), this study demonstrated, for the first time, that OGTT conducted during the postprandial period between 4 and 7.9 h may serve as a valuable tool for diabetes diagnosis and predicting mortality risk. This study suggests that non-fasting OGTT, which is more convenient than fasting OGTT, could be clinically significant.

2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h classified HbA1c-diagnosed diabetes with 92% accuracy (95% CI 89%–94%), falling within the outstanding accuracy range (> 90%)12. This accuracy was comparable to its fasting counterpart, 2-h PGOGTT@fasting, which achieved 95% accuracy (95% CI, 93%–96%). We further conducted analysis using self-reported diagnosis of diabetes. In epidemiological studies, self-reported diagnosis of diabetes is widely accepted due to its relatively higher accuracy compared to many other chronic conditions such as stroke, heart disease, and hypertension43,44. Studies across diverse populations have consistently shown that self-reported diagnosis of diabetes exhibits a sensitivity of approximately 70%–75% in identifying true diabetes, with specificity exceeding 95%45,46,47,48. Our further analysis using self-reported diagnosis confirmed similar diagnostic accuracies between 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h and 2-h PGOGTT@fasting (89% versus 88%). Therefore, our findings suggest that 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h holds promise as a diagnostic marker for diabetes.

The optimal cutoff for predicting HbA1c-diagnosed diabetes with 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h was 206.8 mg/dL, aligning closely with the cutoff for 2-h PGOGTT@fasting at 203.6 mg/dL. This suggests that the clinical cutoff of 200 mg/dL used for 2-h PGOGTT@fasting9,17,18 may be applicable to 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h as well. Participants with 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h ≥ 200 mg/dL demonstrated a significantly higher risk of diabetes mortality (HR, 12.3; 95% CI, 5.4–27.9) compared to those with lower values (< 200 mg/dL).

2-h PGOGTT@fasting is used to identify those at risk of prediabetes49. Here, we investigated whether 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h was associated with prediabetes, which was defined as HbA1c ranging between 5.7% and 6.4%. We found that, in participants without diabetes (HbA1c < 6.5%), those with 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h ≥140 mg/dL had a 29% higher adjusted risk of pre-diabetes compared with those with 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h <140 mg/dL. Therefore, 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h may be useful to identify those with a higher risk of pre-diabetes.

Regarding mortality predictions, both 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h and 2-h PGOGTT@fasting effectively forecasted mortality from CVD and all causes. This is consistent with literature suggesting that 2-h PGOGTT@fasting serves as an independent predictor for CVD50,51,52,53 and all-cause mortality54,55,56,57. Furthermore, 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h also demonstrated comparable predictive ability for mortality from CVD and all causes. It is important to highlight that the glycemic thresholds used for diabetes diagnosis are higher than those associated with elevated mortality risk. This suggests that current diagnostic criteria may be insufficient to fully capture cardiometabolic risk58. Moreover, given that individuals spend the majority of their time in a postprandial state—typically consuming three meals per day—there may be clinical relevance in considering postprandial glycemic measures for risk prediction.

Interestingly, neither 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h nor 2-h PGOGTT@fasting predicted cancer mortality in this study, consistent with some reports in the literature regarding 2-h PGOGTT@fasting59,60,61. Notably, other studies have reported associations between 2-h PGOGTT@fasting and cancer mortality62,63.

Moreover, both 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h and 2-h PGOGTT@fasting predicted mortality specifically from diabetes, consistent with a previous report that 2-h PGOGTT@fasting predicted diabetes mortality64. In fact, 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h exhibited potentially greater sensitivity for predicting diabetes mortality compared to its fasting counterpart, evidenced by an adjusted HR of 21.1 (95% CI, 9.2–48.0) versus 7.1 (95% CI, 4.2–11.9) per 1-square-root increase. A similar trend was observed when analyzing 2-h plasma glucose as a categorical variable (≥ versus < 200 mg/dL), with adjusted HRs of 12.3 (95% CI, 5.4–27.9) and 5.9 (95% CI, 3.4–10.1) for higher PGOGTT@4–7.9 h and PGOGTT@fasting, respectively.

Many guidelines have started to recommend non-fasting lipids (total cholesterol, HDL & LDL cholesterol, and triglyceride) as the standard for cardiovascular risk assessment10,65,66,67. This is because non-fasting lipid tests are more comfortable and convenient for individuals than fasting tests. Importantly, non-fasting tests seem to have similar or better prognostic value for general risk screening65,68, CVD risks10 and all-cause mortality68 compared with their fasting counterpart.

The current study supports the shift from fasting to nonfasting OGTT tests, as 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h has a similar capacity in classifying diabetes diagnosis and in predicting mortality risks from CVD and all causes. The baseline glucose levels (mean ± standard deviation) prior to OGTT were 106.5 ± 34.3 mg/dL in the fasting cohort and 99.9 ± 32.2 mg/dL in the postprandial cohort. Although the 6.6 mg/dL difference was relatively small, it reached statistical significance (p < 0.05). Whether glucose levels during a fasting period of 4 to 7.9 h influence the accuracy of calculated insulin sensitivity and secretion indices remains to be determined. Further research is needed to assess the potential impact of fasting duration on these metabolic parameters.

In conclusion, this study found that 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h classified HbA1c-diagnosed diabetes with an outstanding accuracy of 92%, similar to that of 2-h PGOGTT@fasting (i.e., 95%). 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h predicted mortality risk from diabetes, CVD and all causes. Therefore, 2-h PGOGTT@4–7.9 h, a non-fasting test, might be useful for diabetes classification and CVD risk prediction.

Data availability

All data in the current analysis are publicly available on the NHANES website.

References

ElSayed, N. A. et al. 1. Improving care and promoting health in populations: standards of care in Diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care. 46, S10–S18 (2022).

GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators. Global, regional, and National burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet 402, 203–234 (2023).

World Health Organization. Diabetes Overview. https://www.who.int/health-topics/diabetes#tab=tab_1 (2024).

Bommer, C. et al. Global economic burden of diabetes in adults: projections from 2015 to 2030. Diabetes Care. 41, 963–970 (2018).

Ogurtsova, K. et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults for 2021. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 183, 109118 (2022).

Islam, R. M. et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes and the relative importance of its risk factors among adults in bangladesh: findings from a nationwide survey. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 185, 109228 (2022).

Wild, S. H., Smith, F. B., Lee, A. J. & Fowkes, F. G. R. Criteria for previously undiagnosed diabetes and risk of mortality: 15-year follow-up of the Edinburgh artery study cohort. Diabet. Med. 22, 490–496 (2005).

The Lancet Diabetes. Undiagnosed type 2 diabetes: an invisible risk factor. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 12, 215 (2024).

ElSayed, N. A. et al. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 46, S19–s40 (2023).

Darras, P., Mattman, A. & Francis, G. A. Nonfasting lipid testing: the new standard for cardiovascular risk assessment. CMAJ 190, E1317–E1318 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. Postprandial plasma glucose between 4 and 7.9 h May be a potential diagnostic marker for diabetes. Biomedicines 12, 1313 (2024).

Mandrekar, J. N. Receiver operating characteristic curve in diagnostic test assessment. J. Thorac. Oncol. 5, 1315–1316 (2010).

Wang, Y. Postprandial plasma glucose measured from blood taken between 4 and 7.9 h is positively associated with mortality from hypertension and cardiovascular disease. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 11, 53 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Postprandial plasma glucose with a fasting time of 4-7.9 h is positively associated with cancer mortality in US adults. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 40, e70008 (2024).

Wang, Y. & Fang, Y. Late non-fasting plasma glucose predicts cardiovascular mortality independent of hemoglobin A1c. Sci. Rep. 12, 7778 (2022).

Eichenlaub, M. M. et al. A glucose-Only model to extract physiological information from postprandial glucose profiles in subjects with normal glucose tolerance. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 16, 1532–1540 (2022).

American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care 44, S15–S33 (2021).

American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 42, S13–s28 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Fasting triglycerides are positively associated with cardiovascular mortality risk in people with diabetes. Cardiovasc. Res. 119, 826–834 (2023).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Plan and operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-94. Series 1: programs and collection procedures. Vital Health Stat. 1, 1–407 (1994).

Gunter, E. W., Lewis, B. G. & Koncikowski, S. M. Laboratory Procedures Used for the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), 1988–1994. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes3/manuals/labman.pdf (2024).

Kubihal, S., Goyal, A., Gupta, Y. & Khadgawat, R. Glucose measurement in body fluids: A ready reckoner for clinicians. Diabetes Metabolic Syndrome: Clin. Res. Reviews. 15, 45–53 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Dietary fatty acids and mortality risk from heart disease in US adults: an analysis based on NHANES. Sci. Rep. 13, 1614 (2023).

Qin, H., Shen, L. & Xu, D. Association of composite dietary antioxidant index with mortality in adults with hypertension: evidence from NHANES. Front. Nutr. 11, 1371928 (2024).

Jungo, K. T. et al. Baseline characteristics and comparability of older multimorbid patients with polypharmacy and general practitioners participating in a randomized controlled primary care trial. BMC Fam Pract. 22, 123 (2021).

Qian, T. et al. Hyperuricemia is independently associated with hypertension in men under 60 years in a general Chinese population. J. Hum. Hypertens. 35, 1020–1028 (2021).

Jackman, K. A. et al. Vascular expression, activity and function of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-1 following cerebral ischaemia-reperfusion in mice. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 383, 471–481 (2011).

Wang, Y. Stage 1 hypertension and risk of cardiovascular disease mortality in united States adults with or without diabetes. J. Hypertens. 40, 794–803 (2022).

Lyu, Y., Xu, Q. & Liu, J. Exploring the medical decision-making patterns and influencing factors among the general Chinese public: a binary logistic regression analysis. BMC Public. Health. 24, 887 (2024).

Cheng, W. et al. The association between serum uric acid and blood pressure in different age groups in a healthy Chinese cohort. Med. (Baltim). 96, e8953 (2017).

Luckett, D. J. et al. Receiver operating characteristic curves and confidence bands for support vector machines. Biometrics 77, 1422–1430 (2021).

Unal, I. Defining an optimal Cut-Point value in ROC analysis: an alternative approach. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2017, 3762651 (2017).

Goel, M. K., Khanna, P. & Kishore, J. Understanding survival analysis: Kaplan-Meier estimate. Int. J. Ayurveda Res. 1, 274–278 (2010).

West, R. M. Best practice in statistics: the use of log transformation. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 59, 162–165 (2022).

Arnold, B. F., Hogan, D. R., Colford, J. M. & Hubbard, A. E. Simulation methods to estimate design power: an overview for applied research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 11, 94 (2011).

Wilson, D. T. et al. Efficient and flexible simulation-based sample size determination for clinical trials with multiple design parameters. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 30, 799–815 (2021).

American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 10. Cardiovascular disease and risk management: standards of medical care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 45, S144–s174 (2022).

Šimundić, A. M. Measures of diagnostic accuracy: basic definitions. Ejifcc 19, 203–211 (2009).

Shreffler, J. & Huecker, M. Diagnostic testing accuracy: Sensitivity, specificity, predictive values and likelihood ratios. StatPearls.. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557491/ (2023).

Eusebi, P. Diagnostic accuracy measures. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 36, 267–272 (2013).

Ialongo, C. Confidence interval for quantiles and percentiles. Biochem. Med. (Zagreb). 29, 010101 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Reduced renal function May explain the higher prevalence of hyperuricemia in older people. Sci. Rep. 11, 1302 (2021).

Muggah, E., Graves, E., Bennett, C. & Manuel, D. G. Ascertainment of chronic diseases using population health data: a comparison of health administrative data and patient self-report. BMC Public. Health. 13, 16 (2013).

Lix, L. M. et al. Population-based data sources for chronic disease surveillance. Chronic Dis. Can. 29, 31–38 (2008).

Huerta, J. M. et al. Accuracy of self-reported diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia in the adult Spanish population. DINO study findings. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 62, 143–152 (2009).

Guo, H., Yu, Y., Ye, Y. & Zhou, S. Accuracy of Self-Reported Hypertension, Diabetes, and hyperlipidemia among adults of Liwan, Guangzhou, China. Iran. J. Public. Health. 49, 1622–1630 (2020).

Li, H. L. et al. Personal characteristics effects on validation of Self-reported type 2 diabetes from a Cross-sectional survey among Chinese adults. J. Epidemiol. 30, 516–521 (2020).

Moradinazar, M. et al. Validity of self-reported diabetes varies with sociodemographic charecteristics: example from Iran. Clin. Epidemiol. Global Health. 8, 70–75 (2020).

Pragati, G. & Paolo, P. Divergence in prediabetes guidelines - A global perspective. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 223, 112142 (2025).

de Vegt, F. et al. Hyperglycaemia is associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the Hoorn population: the Hoorn study. Diabetologia 42, 926–931 (1999).

Rong, L. et al. One-hour plasma glucose as a long-term predictor of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in a Chinese older male population without diabetes: A 20-year retrospective and prospective study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 947292 (2022).

Gabir, M. M. et al. Plasma glucose and prediction of microvascular disease and mortality: evaluation of 1997 American diabetes association and 1999 world health organization criteria for diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 23, 1113–1118 (2000).

Silbernagel, G. et al. Isolated post-challenge hyperglycaemia predicts increased cardiovascular mortality. Atherosclerosis 225, 194–199 (2012).

Nakagami, T. Hyperglycaemia and mortality from all causes and from cardiovascular disease in five populations of Asian origin. Diabetologia 47, 385–394 (2004).

DECODE Study Group. Glucose tolerance and cardiovascular mortality: comparison of fasting and 2-hour diagnostic criteria. Arch. Intern. Med. 161, 397–405 (2001).

Rodriguez, B. L. et al. The American diabetes association and world health organization classifications for diabetes: their impact on diabetes prevalence and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in elderly Japanese-American men. Diabetes Care. 25, 951–955 (2002).

Metter, E. J. et al. Glucose and insulin measurements from the oral glucose tolerance test and mortality prediction. Diabetes Care. 31, 1026–1030 (2008).

Lizarzaburu-Robles, J. C. et al. Prediabetes and cardiometabolic risk: the need for improved diagnostic strategies and treatment to prevent diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Biomedicines 12, 363 (2024).

Brunner, E. J. et al. Relation between blood glucose and coronary mortality over 33 years in the Whitehall study. Diabetes Care. 29, 26–31 (2006).

Lu, W. et al. Effects of isolated post-challenge hyperglycemia on mortality in American indians: the strong heart study. Ann. Epidemiol. 13, 182–188 (2003).

Stengård, J. H. et al. Diabetes mellitus, impaired glucose tolerance and mortality among elderly men: the Finnish cohorts of the seven countries study. Diabetologia 35, 760–765 (1992).

Jiang, C. Q. et al. Glycemic measures and risk of mortality in older chinese: the Guangzhou biobank cohort study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 105, e181–e190 (2019).

Zhou, X. H. et al. Diabetes, prediabetes and cancer mortality. Diabetologia 53, 1867–1876 (2010).

Sievers, M. L., Bennett, P. H. & Nelson, R. G. Effect of glycemia on mortality in Pima Indians with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 48, 896–902 (1999).

Mach, F. et al. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk: the task force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European society of cardiology (ESC) and European atherosclerosis society (EAS). Eur. Heart J. 41, 111–188 (2019).

Pearson, G. J. et al. 2021 Canadian cardiovascular society guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult. Can. J. Cardiol. 37, 1129–1150 (2021).

Grundy, S. M. et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 139, e1082–e1143 (2019).

Fang, Y. & Wang, Y. Fasting status modifies the association between triglyceride and all-cause mortality: A cohort study. Health Sci. Rep. 5, e642 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W.; formal analysis, Y.W.; data curation, Y.W., Y.F., G.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W., Y.F., G.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.W., Y.F., G.Y., F.P., A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Fang, Y., Yang, G. et al. Postprandial 2-h glucose tolerance is associated with diabetes diagnosis, diabetes mortality, and cardiovascular mortality. Sci Rep 15, 43853 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28849-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28849-y