Abstract

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and structural musculoskeletal abnormalities cause substantial work-related pain, disability, and productivity loss in industrial workforces; traditional screening tools and single-variable analyses can miss complex, interdependent risk patterns that arise from combined biomechanical exposures, workstation mismatches, and worker characteristics. We aimed to develop and validate a data-driven framework — Fuzzy Irregular Cellular Automata (FICA) — to integrate multi-modal ergonomic measurements, detect high-risk abnormality clusters, quantify their associations with MSDs and demographic predictors, and prioritize targeted ergonomic interventions. Comprehensive data were collected from 415 supervisory/administrative workers (15 objectively measured abnormalities; self-reported MSDs via the Nordic questionnaire; workstation anthropometry; exposure-time logs). FICA represented the inputs as a fuzzy graph and applied Mamdani inference with a voting/colouring routine (FICAVCA) to identify clusters and rank interventions. Model validation used repeated 10-fold cross-validation and benchmarking against alternative algorithms. FICA identified interpretable high-risk clusters (e.g., lumbar lordosis + dropped shoulder, 22.2%) and demonstrated strong predictive performance (accuracy = 0.92; stability index = 0.89). Multivariate analyses confirmed BMI, age, and work experience as key predictors (R² = 0.43, p < 0.001); BMI ≥ 30 increased odds of lumbar lordosis (OR = 2.3) and genu varum (OR = 1.9). Model-based intervention simulations estimated prioritized workstation and exercise interventions could reduce cluster risk by up to ≈ 34% (scenario projections). FICA provides an interpretable, scalable method to translate multimodal ergonomic data into prioritized, resource-efficient interventions. Longitudinal trials are needed to validate projected intervention effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are a leading occupational health problem worldwide, causing pain, disability, reduced productivity, and substantial healthcare costs. These disorders—commonly presenting as low back pain, neck pain, shoulder complaints, and lower-limb conditions—are highly prevalent in industrial workforces and represent a major public health and economic burden. Recent global and national estimates emphasize the scope and impact of MSDs in both developed and developing countries1,2.

Despite their importance, commonly used ergonomic assessment tools have important limitations. Traditional instruments such as the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire, Rapid Upper Limb Assessment (RULA), and other posture-analysis methods provide useful screening information but often cannot capture the complex, multivariable and network-like relationships among biomechanical exposures, individual susceptibilities, and environmental context. These methods are also sensitive to self-report bias and may not fully exploit continuous or high-dimensional data (e.g., wearable sensor streams, detailed posture metrics). Such limitations reduce the ability to accurately identify workers at highest risk or to prioritize interventions in resource-constrained industrial settings3,4,5.

The complexity of ergonomic risk arises from interactions among biomechanical factors (e.g., prolonged awkward postures, compressive loads), demographic characteristics (age, body mass index (BMI), work experience), and workstation/environment factors (e.g., chair and desk mismatch). Recent systematic reviews and epidemiological studies have catalogued specific causative and risk factors for MSDs—such as whole-body vibration, repetitive tasks, and prolonged awkward postures—reinforcing the multifactorial nature of these conditions6,7. These multivariable and sometimes non-linear relationships, together with uncertainty in measurement and reporting, create challenges for standard statistical approaches. For example, prolonged duration of otherwise-acceptable postures can substantially increase joint and spinal stress even when instantaneous postural risk appears low8,9,10.

There is therefore a clear need for advanced computational approaches that can (a) handle irregular and heterogeneous data, (b) represent networked interactions among variables, and (c) accommodate uncertainty and imprecision in measurements. Hybrid methods that combine fuzzy logic with graph-based or automata models offer a promising route because they can model soft boundaries between risk levels and capture complex spatial/temporal dependencies in workplace data11,12,13,14,15.

In this study, we apply the Fuzzy Irregular Cellular Automata (FICA) model as a novel, data-driven framework for ergonomic risk assessment and prediction of musculoskeletal abnormalities and musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) among industrial workers. FICA integrates fuzzy membership mappings to manage uncertainty and irregular cellular automata to model heterogeneous interaction networks among worker-level and workstation-level features11,12. Therefore, This study aimed to develop and validate a Fuzzy Irregular Cellular Automata (FICA) model to identify high-risk clusters of musculoskeletal abnormalities, assess their associations with MSDs and demographic factors, and propose targeted ergonomic interventions for industrial workers.

Definitions and terminology

To avoid ambiguity we use the following terms consistently in the manuscript:

-

Musculoskeletal abnormalities — objectively measured structural or postural deviations (for example, lumbar lordosis angle beyond a normative range, shoulder height asymmetry, genu varum distance) assessed by clinical/ergonomic instruments (goniometer, inclinometer, arcometer, calipers).

-

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) — symptom- and function-based conditions (for example, work-related low back pain, neck pain, knee pain) typically captured via self-report instruments such as the Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (NMQ). MSDs refer to the experience of pain, discomfort or functional limitation, whether or not an objective abnormality is present.

Methodology

Study design and participants

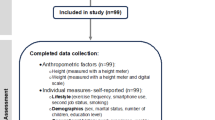

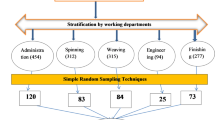

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2025 among 430 male employees of an iron-smelting and sponge-iron production company in Sirjan, Iran. The study population included all supervisory and administrative staff, whose work primarily involved seated, low-mobility tasks. Sampling was census-based, and all eligible employees were invited to participate. Inclusion criteria were at least six months of office work experience and willingness to participate, while exclusion criteria were prior musculoskeletal injuries or non-sedentary job duties. Accordingly, 415 workers participated (response rate: 96%). Ethical approval was obtained from the Sirjan University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (IR.SIRUMS.REC.1402.007), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The methodological framework followed a six-step process of ergonomic data collection and modeling (Fig. 1).

Step 1-Assessment of MSDs and musculoskeletal abnormalities

The Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (NMQ) was used to collect standardized information on self-reported musculoskeletal symptoms across body regions. The NMQ is an internationally recognized, validated screening instrument for occupational musculoskeletal symptoms16. For this study we used the Persian version of the extended NMQ (NMQ-E), which has been translated, culturally adapted, and validated for Persian-speaking populations and shown to have acceptable validity and test–retest reliability. Mokhtarinia et al. showed the intra-class correlation coefficient and the standard error of measurement of the Persian version of the NMQ were deemed acceptable (SEM = 0.56–1.76 and ICC > 0.7) and the Kappa coefficient was calculated as 0.78–1.00.78.0017.

The musculoskeletal abnormalities examined included lateral pelvic tilt, anterior pelvic tilt, posterior pelvic tilt, dropped shoulder, scoliosis, ankle valgus, ankle varus, forward shoulders, forward head posture, genu recurvatum (knee hyperextension), genu varum (bow-leggedness), genu valgum (knock-knees), kyphosis, lumbar lordosis, and cervical lordosis (Fig. 2). These 15 musculoskeletal abnormalities were selected according to three criteria1: responsiveness to ergonomic interventions, meaning the abnormality could reasonably be improved by workstation adjustment, training or exercise2; feasibility of objective measurement using field-portable instruments available to our team (calipers, arcometer, inclinometer, digital goniometer); and3 precedent in ergonomics practice and literature, where similar sets of postural/structural measures are commonly used in workplace screening programs. Selection was performed by a multidisciplinary team (occupational physicians, ergonomists, and physiotherapists) to ensure clinical relevance and measurement reliability.

Continuous and observational abnormality measures were converted to categorical severity levels (none/mild/moderate/severe) using predefined, a priori thresholds and scoring rules. For continuous angle or distance measures (e.g., lumbar lordosis angle, forward head angle, genu varum distance), thresholds were defined with reference to clinical and ergonomic normative ranges and prior literature where available.

Two trained technicians collected musculoskeletal abnormalities data. For intra-observer assessment, the musculoskeletal abnormalities measurements were taken on 2% of study sample (9 participants) in the present study (chosen randomly)18. Both technician measured each participant’s abnormality three consecutive times within 1 h. For interobserver assessment, a complete set of musculoskeletal abnormalities measurements was taken on 9 participants (chosen randomly). Both technicians measured the same participant once. The interobserver reliability investigation was performed on a separate day from the intraobserver reliability test18. Technical error of measurement (TEM) was used to calculate a reliability coefficient (R)19. The reliability coefficient of more than 0.8 indicated the appropriate precision of the measurements20. For actual measurement, the supervising researcher assessed the musculoskeletal abnormalities of 10% of each technician’s sample to ensure accurate measurements. If at least two of the three measurements were correct, the measurements were considered accurate21.

Step 2-workstation assessment

Workstation dimensions were measured and compared with workers’ anthropometric data to assess ergonomic fit. Measurements included seat pan height, depth, and width; armrest height; thigh clearance; desk height; and backrest dimensions. Each dimension was measured twice, and discrepancies greater than 5% were resolved through a third reading. The purpose of this step was to identify mismatch conditions between individual anthropometric characteristics and workstation geometry, which were later used as input variables for FICA modeling.

Step 3-biomechanical analysis

Biomechanical analysis was performed using the 3D Static Strength Prediction Program (3DSSPP, Version 7; University of Michigan). The 3DSSPP software program was developed to assess the static and biomechanical forces of workers related to the physical demands of the workplace22. The software can provide a wide range of information and analysis, from predicted back compression forces to information related to the strength capabilities of the population. The percentage of strength capabilities (for each joint, the resultant torque produced by the load and body weight; muscle effect; population mean strength, standard deviation, and percentage of the population with the strength ability to produce a torque greater than the resultant torque) was examined. In this way, the software shows the percentage of people in the population who can work in the examined posture without injury.

Step 4-exposure time assessment

The purpose of this stage was to quantify the duration and frequency of exposure to potentially stressful postures. Observational time logs were used to record the duration spent in seated, standing, and dynamic positions during a typical workday. A subset of observations was validated using video recordings for verification. The data were expressed as the percentage of total work time spent in each posture type, and used later as temporal weightings in the model.

Step 5-ergonomic interventions

Based on each worker’s MSD profile and abnormality assessment, ergonomic interventions were proposed to reduce risks. These included workstation adjustments, education on ergonomic postures, and corrective exercise prescriptions for musculoskeletal abnormalities. Each recommendation was tagged with an estimated intervention effectiveness coefficient derived from ergonomic guidelines and literature sources. These coefficients were later incorporated as optimization parameters in the modeling stage.

Intervention-effect parameterization and simulation protocol. For simulation and prioritization, each candidate intervention (e.g., backrest adjustment, seat-depth change, corrective-exercise program) was assigned an effect-size parameter representing its expected proportional impact on the relevant node state(s). These parameters were derived from a combination of published intervention effect estimates and interdisciplinary expert judgement from the study team (occupational physicians, ergonomists, physiotherapists). To estimate expected intervention impacts, we applied each intervention parameter to affected nodes by reducing their fuzzy severity states proportionally and then reran the FICA/FICAVCA routine to obtain post-intervention cluster severity measures. Relative risk reduction for each cluster was calculated as (pre-intervention mean severity − post-intervention mean severity)/pre-intervention mean severity and expressed as a percentage. Simulation results were averaged across repeated runs with different random seeds to assess robustness (see Model Validation). These outputs are model projections (scenario estimates), not observed results from implemented workplace interventions.

Step 6-data analysis and FICA modeling

This stage involved integrating all datasets and applying the Fuzzy Irregular Cellular Automata (FICA) model developed by Kashani et al.23for high-risk cluster detection and intervention prioritization (Fig. 3).

Fuzzy mapping and justification

Categorical severity labels were subsequently mapped to fuzzy numeric states for FICA modelling: mild = 0.3, moderate = 0.6, severe = 0.9 (and none = 0.0). We selected these centers to produce clearly separated but overlapping membership functions that reflect graded clinical severity rather than hard binary thresholds. The mapping rationale is threefold1: uncertainty representation — many field measures and self-reports have inherent imprecision; fuzzy states allow partial membership and reduce sensitivity to small measurement differences2, interpretability — three well-spaced membership centers (0.3/0.6/0.9) are easy to interpret and implement within Mamdani inference, and3 numerical stability — overlapping triangular/gaussian membership functions prevent abrupt state jumps and improve model convergence. Membership function supports and shapes used were triangular/gaussian with supports selected to create moderate overlap. We conducted sensitivity analyses by varying the membership centers by ± 0.1 and varying the membership function widths; results showed the main cluster assignments and performance metrics were stable (stability index = 0.89; performance deviations < 11%). Finally, when mapping from raw measurements to categorical severities we prioritized clinical relevance (normative ranges and ergonomics guidance) and inter-rater consensus to assure that mappings reflected meaningful differences for occupational health decision-making.

Graph construction and edge definitions

The dataset was represented as an undirected weighted heterogeneous graph G(V, E) in which nodes V comprised two types: worker nodes Wi (one node per participant) and abnormality nodes Ak (one node per measured abnormality type). Edges eij\(\epsilon{E}\)capture pairwise relationships among nodes and are weighted to represent the strength of those relationships. Three edge classes were used:

-

Worker–Abnormality edges\((W_i\leftrightarrow{A_k})\).

These edges represent the measured relationship between a worker and a specific abnormality. For a given worker i and abnormality k, the raw measurement (angle, distance, score) was first mapped to a categorical severity (none, mild, moderate, severe) and then to a fuzzy state \(S_{ik}\epsilon[0,1]\) (none = 0.0, mild = 0.3, moderate = 0.6, severe = 0.9). The initial worker–abnormality weight is therefore:

Optionally, this weight is adjusted by a workstation-impact factor \(I_{ik}\epsilon[0,1]\) (how much the workstation mismatch is believed to affect that abnormality for worker i) to produce a composite weight:

Where an impact factor was not applicable or not available, Iik=1.

-

Abnormality–Abnormality edges\((A_p\leftrightarrow{A_q})\).

Abnormality nodes were connected when they showed statistical association across the sample. Association was measured using Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients (or co-occurrence frequency for non-continuous scores). The raw association rpq was converted to a non-negative weight and normalized to the unit interval:

where “normalize” scales values linearly to [0,1] across the set of observed associations. If composite evidence (correlation + co-occurrence frequency) was used, a weighted-sum composite was applied:

followed by normalization: wAp, Aq = normalize(wAp, Aq). The coefficients α\alphaα and β\betaβ were set by sensitivity analysis (see below) and are reported as α = 0.5, β = 0.5.

-

Worker–Worker edges\((W_i\leftrightarrow{W_j})\).

Worker similarity edges encode how similar two workers are across a selected feature vector Fi (e.g., demographics, normalized workstation metrics, exposure-time measures, and aggregated abnormality severities). We used cosine similarity as the default metric:

and set worker–worker weight \(w_{wi, wj}=normalize(\mid{sim(i,j)}\mid)\). Alternative similarity metrics (Pearson on standardized features, Euclidean-based similarity) were explored in sensitivity analyses.

-

Weight normalization and thresholding.

All raw weights were scaled to the unit interval [0,1] by linear min–max normalization across the relevant edge set prior to combining heterogeneous edges. To reduce noise and focus on meaningful relations, an edge retention threshold τ\tauτ was applied: edges with wij < τ were removed from the graph. The threshold τ\tauτ was selected by sensitivity analysis and set to τ = 0.1 in the primary analysis (sensitivity range tested: 0.05–0.2). All adjacency matrices used for FICA were symmetric (undirected) by construction.

-

Composite edge weighting.

Where multiple evidence streams applied between the same node pair (for example, a combined correlation and workstation impact), we computed a composite weight as a weighted sum:

with α + β + γ = 1. Coefficients were chosen by grid search and sensitivity analysis and are reported in Methods (Model Validation).

Graph representation and clustering

The final graph G(V, E) is represented by a weighted adjacency matrix W. FICA operates on this heterogeneous graph: worker and abnormality nodes coexist and influence each other during fuzzy state updates (worker nodes propagate their abnormality severities to neighboring abnormality nodes and vice versa). This design lets FICA detect clusters that may include multiple worker nodes connected to one or more abnormality nodes (e.g., a cluster of workers sharing a common abnormality pattern) and also abnormality-only clusters (groups of co-occurring abnormalities). The clustering and priority selection (FICAVCA voting–colouring routine) use the same weighted graph; local densities and node weights account for node type and degree when casting votes and selecting intervention priorities.

Conceptual overview

FICA is a hybrid of Irregular Cellular Automata (ICA) and Fuzzy Cellular Automata (FCA) designed for complex systems represented as graphs. Each node represents either a worker or an abnormality, and each edge denotes a quantified relationship such as correlation strength, ergonomic mismatch, or co-occurrence (The FICA transfer process is illustrated in Fig. 4). The model structure is defined as a 4-tuple A = < G(V, E), S, N, F>, where:

-

G(V, E) is the undirected graph of workers and abnormality relationships.

-

S (0–1) represents fuzzy states (e.g., severity of abnormality: mild = 0.3, moderate = 0.6, severe = 0.9).

-

N defines neighboring nodes for each vertex.

-

F is the fuzzy transition function, which updates node states using a Mamdani inference engine and center-of-gravity defuzzification.

The model allows for uncertainty handling via fuzzy mapping (see Table 1) and for network-like representation of irregular ergonomic interactions (e.g., between lumbar lordosis and dropped shoulder).

Rationale for using FICA: FICA was selected over other clustering algorithms because it can simultaneously represent spatial irregularity and uncertainty while maintaining interpretability in ergonomic systems. Unlike traditional graph or machine learning models, FICA incorporates human-like fuzzy reasoning and can identify both local and global high-risk patterns. However, it assumes a static graph per iteration and relies on the precision of fuzzy rule definitions, which we acknowledge as limitations.

Model validation and performance evaluation

All algorithms (FICA, TPA, ILS, Greedy) were evaluated on the same dataset using a repeated cross-validation procedure to ensure a fair comparison. We performed 10-fold cross-validation (each fold ≈ 80% training/20% testing) repeated five independent times, yielding 50 test folds in total. The same random seeds were used to generate train/test splits and to initialize algorithmic randomness across all methods so that each algorithm saw identical data partitions and comparable initial conditions.

For each test fold we recorded key performance metrics: accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, AUC (from confusion matrices), and execution time. Table 2 reports summary values (mean ± SD across the 50 test folds) for accuracy, execution time, stability index, and number of clusters. Sensitivity, specificity, precision and AUC are reported in Results (sensitivity = 0.85, specificity = 0.88, precision = 0.82, AUC = 0.91).

To quantify run-to-run consistency of the clustering outputs we performed 20 additional independent stability runs (different random seeds) and computed a stability index defined as the mean pairwise cluster-assignment concordance (Jaccard similarity) across runs; stability index values are reported in Table 2. Intervention scenario simulations were executed using the same validation folds and repeated runs; intervention-effect estimates were averaged across repeated simulations to obtain stable scenario summaries.

Sensitivity analyses explored the effect of varying key hyperparameters (correlation threshold τ, membership-function centers and widths, and iteration counts). The primary analysis used τ = 0.1 (sensitivity range tested: 0.05–0.2). Performance deviations across the tested parameter grid were small (mean deviation < 11%) and did not change the substantive cluster assignments.

Statistical comparisons across algorithms

Fold-level accuracies (50 paired test-fold accuracy values per algorithm) were used for statistical comparison. Because accuracy distributions over folds were not assumed to be normally distributed, we applied the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (two-tailed) for pairwise comparisons of FICA versus each alternative algorithm. P-values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni procedure. Pairwise Wilcoxon p-values (FICA vs. Greedy, FICA vs. TPA, FICA vs. ILS) are reported in the Table 2 footnote (p = 0.0012, p = 0.0034, p = 0.0087, respectively). As a sensitivity check, paired t-tests were also computed where appropriate and yielded consistent conclusions.

Statistical analysis

Multivariate modeling and diagnostic protocol

The primary multivariable analysis evaluated predictors of the participant-level abnormality count (dependent variable). After inspecting the empirical distribution (histogram and dispersion index), we specified a multivariable linear regression as the main model because the outcome approximated a continuous distribution. Covariates chosen a priori were BMI (kg/m², continuous), age (years, continuous), and work experience (years, continuous). Additional candidate covariates considered for adjustment were gender, workstation mismatch score, exposure time to seated posture. We used a forced-entry strategy for these pre-specified predictors to reflect hypothesis-driven analysis; model selection considered both clinical relevance and information criteria (AIC/BIC) where additional candidate covariates were evaluated.

Where diagnostic checks indicated violation of linear-model assumptions (notably non-normal residuals or overdispersion), we fitted generalized linear models as sensitivity analyses. For count/overdispersed data we used a negative-binomial GLM (rather than Poisson) and report those estimates alongside the linear model results.

Multicollinearity and diagnostics

Multicollinearity was assessed using variance inflation factors (VIF); covariates with VIF > 5 were considered to indicate problematic collinearity and were evaluated for removal or combination. Model residuals were inspected graphically (residual vs. fitted plots; Q–Q plots) and tested formally for normality (Shapiro–Wilk test, p = 0.062) and heteroscedasticity (Breusch–Pagan test, p = 0.119). Overdispersion for count models was evaluated using the dispersion statistic (dispersion = 1.27); when dispersion exceeded conventional thresholds we report negative-binomial estimates. Influential observations were evaluated by Cook’s distance with threshold set as 4/n (for n = 415, Cook’s D threshold = 0.00964); observations exceeding this threshold were examined and sensitivity models without influential cases were run. Model goodness-of-fit is reported as adjusted R² (adjusted R² = 0.41) for linear models and deviance/dispersion statistics for GLMs. All tests were two-sided with α = 0.05.

Presentation of results

Regression coefficients (β for linear models; incidence rate ratios or odds ratios for GLMs where applicable), 95% confidence intervals, and p-values are reported in Table 5. We present both the main model and sensitivity models (alternative variable selections and GLMs) to demonstrate robustness.

Ethical considerations

All data were anonymized before analysis. Participants received individualized ergonomic feedback and training recommendations. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Sirjan University of Medical Sciences (IR.SIRUMS.REC.1402.007).

The full operational flow of the FICAVCA algorithm is shown in Figs. 5, 6.

Results

By applying fuzzy mapping to abnormality severity (mild = 0.3, moderate = 0.6, severe = 0.9) and a Mamdani-based transition function, the Fuzzy Irregular Cellular Automata (FICA) model analyzed local interactions between nodes (workers, abnormalities) and edges (correlations, workstation impacts). Model outputs included cluster assignments, ranked intervention priorities (FICAVCA), and expected risk reductions from candidate interventions. Model performance (validation and benchmarking) is summarized below and in Table 2 (Methods); detailed prevalence and association results are presented in Tables 3, 4 and 5.

Participant characteristics

Table 3 gives participant demographics. Briefly, participants were predominantly middle-aged (mean age 35.2 years, SD 6.8) with average work experience 9.3 years (SD 5.7). Mean BMI was 26.4 (SD 3.2), with 21.4% categorized as obese (BMI ≥ 30).

BMI distribution: underweight 4.3% (n = 18), normal weight 40.5% (n = 168), overweight 33.7% (n = 140), obese 21.4% (n = 89).

Prevalence of abnormalities and association with MSDs

Key prevalence and primary associations are summarized in the Table 4. High prevalence of lumbar lordosis (62%) and dropped shoulder (50%) were observed. Overall, 403 participants (97%) had at least one abnormality; total abnormalities = 1,114 (mean per person = 2.7). Overall MSD prevalence was 45% (n = 187); most commonly affected regions were lower back 35.9% (n = 149), knees 20.5% (n = 85), and neck 15.7% (n = 65).

Predictors of abnormality count and specific abnormality risk (regression and ORs)

We investigated predictors of the total number of measured musculoskeletal abnormalities (abnormality count) and risk factors for specific abnormalities using multivariable regression and logistic regression models. The dependent variable for the primary analysis was the participant-level abnormality count (range 0–15). Covariates included a priori were body mass index (BMI, continuous, kg/m²), age (years, continuous), and work experience (years, continuous). All models and diagnostics reported below were fitted using SPSS v26.

Primary multivariable modeling (abnormality count)

A multivariable linear regression model with abnormality count as the outcome and BMI, age, and work experience as predictors explained a substantial portion of variance (R² = 0.43, p < 0.001). The model was specified using a forced-entry strategy (all prespecified covariates entered simultaneously) to reflect hypothesis-driven variable selection. Adjusted R² and full coefficient estimates (β), standard errors, 95% confidence intervals and p-values for each predictor are presented in Table 5.

Model diagnostics and sensitivity analyses

We evaluated multicollinearity using variance inflation factors (VIF); maximum VIF = 1.84 (mean VIF = 1.62), indicating [acceptable/moderate] collinearity. Residual diagnostics included graphical inspection (residual vs. fitted plots, Q–Q plots) and formal tests: Shapiro–Wilk for normality (p = 0.062) and Breusch–Pagan for heteroscedasticity (p = 0.119). Influential observations were examined using Cook’s distance (maximum Cook’s D = 0.0073; no observations exceeded the commonly used threshold of 0.0096). Where linear regression assumptions were not fully met in sensitivity checks, we fitted a negative-binomial generalized linear model (GLM) for abnormality count (to accommodate potential overdispersion). The negative-binomial model produced effect estimates consistent in direction and inference with the linear model (see Table 5 for full sensitivity results).

Logistic regression for individual abnormalities

We examined specific abnormality outcomes (binary presence/absence) using logistic regression models with BMI category (≥ 30 vs. < 30), age category (> 40 vs. ≤ 40), and work experience (> 10 vs. ≤ 10 years) as primary predictors. Selected results include:

-

BMI ≥ 30 increased odds of lumbar lordosis: OR = 2.3 (95% CI: 1.5–3.5; p < 0.001).

-

BMI ≥ 30 increased odds of genu varum: OR = 1.9 (95% CI: 1.3–2.8; p < 0.01).

-

BMI ≥ 30 increased odds of genu recurvatum: OR = 1.6 (95% CI: 1.1–2.4; p < 0.05).

Age > 40 was positively associated with kyphosis (r = 0.42, p < 0.005) and cervical lordosis (r = 0.39, p < 0.005). Work experience > 10 years correlated with lumbar lordosis (r = 0.45, p < 0.005) and dropped shoulder (r = 0.34, p < 0.01). Full logistic model coefficients, 95% CIs, p-values, and model fit statistics (Hosmer–Lemeshow, Nagelkerke R² where appropriate) are provided in Table 5.

Interpretation and robustness

Across modeling approaches (linear regression, negative-binomial GLM, and logistic regressions), BMI, age, and work experience were consistent predictors of overall abnormality burden and of several specific abnormalities. Diagnostic checks and sensitivity analyses (alternative covariate specifications, GLM family choice, and exclusion of influential cases) produced similar inferences, supporting the robustness of the reported associations. Detailed model diagnostics and supplementary plots are available upon request or in the supplementary material.

Cluster detection and interpretation

FICA identified several clinically meaningful high-risk clusters. Below we present the clusters, their epidemiological prevalence, and an ergonomic interpretation that links cluster composition to plausible causal mechanisms and recommended priorities.

Cluster 1 — Lumbar lordosis + Dropped shoulder

-

Prevalence: 22.2% (n = 91).

-

Interpretation: Combined spinal (lumbar) and shoulder misalignment consistent with prolonged sitting with poor lumbar/back support and forward-reach or rounded-shoulder tasks. This cluster is associated with elevated odds of low back pain (cluster OR for low back pain = 2.8, 95% CI: 1.8–4.3, p < 0.001).

-

Intervention priority: Backrest adjustment (improve lumbar support), seat depth adjustment, and posture training. These interventions were ranked highest by FICAVCA for expected impact.

Cluster 2 — Lumbar lordosis + Genu varum

-

Prevalence: 15.4% (n = 64).

-

Interpretation: The cluster links lumbar spinal curvature with lower-limb alignment issues; plausible mechanisms include prolonged sitting with intermittent load-bearing transitions that interact with lower-limb alignment or pre-existing knee loading patterns.

-

Intervention priority: Combined workstation adjustments and lower-limb strengthening/stretching programs.

Cluster 3 — Dropped shoulder + Cervical lordosis

-

Prevalence: 12.8% (n = 53).

-

Interpretation: Upper-body/neck postural strain cluster, likely associated with sustained forward head posture, monitor position, or poor shoulder ergonomics.

-

Intervention priority: Monitor and desk height adjustments, ergonomic training, and targeted neck/shoulder exercises.

Associations among abnormalities (network findings)

FICA’s graph-based analysis highlighted notable inter-region correlations:

-

Dropped shoulder — cervical lordosis: r = 0.46 (p < 0.001).

-

Lumbar lordosis — genu varum: r = 0.41 (p < 0.001).

-

Kyphosis — ankle valgus: r = 0.37 (p < 0.005).

Path modeling (derived from the fuzzy-updated graph) indicated an indirect pathway in which lumbar lordosis influenced dropped shoulder via genu varum (standardized indirect β = 0.32, p < 0.01), suggesting mechanical/compensatory linkages between spine and lower-limb alignment in this population.

Workstation mismatches and Biomechanical analysis

Workstation mismatches were common and quantified as: chair backrest mismatch 27% (n = 61), seat depth mismatch 20% (n = 46), and desk height mismatch 16% (n = 35). These mismatches correlated with measured abnormalities (overall r ≈ 0.51, p < 0.001).

Using participant-specific anthropometry, measured joint angles and workstation dimensions, 3DSSPP static simulations indicated that 97% of modeled instantaneous postures fell within the program’s static safety limits for joint loads under the input assumptions described in Methods. Because 3DSSPP provides instantaneous (static) load estimates, these results do not capture time-dependent fatigue: 79.4% of participants nevertheless had excessive uninterrupted seated durations, indicating high cumulative exposure despite generally acceptable instantaneous loads.

Intervention scenario simulations

The estimated reductions reported below are model-projected values derived from FICA intervention simulations (scenario analyses), not measured outcomes following implemented interventions. Using literature/expert-derived effect parameters applied to affected node states, we reran FICA and computed relative pre/post reductions in cluster severity. The simulation-averaged estimates were: backrest adjustment → projected ~ 18% reduction in lumbar-lordosis cluster severity; corrective exercise → projected ~ 22% reduction in combined-cluster severity; combined optimized interventions → projected aggregate cluster-risk reduction up to ~ 34%. These are scenario-driven projections intended to prioritize interventions and require field validation.

Model performance, validation, and benchmarking

Model validation used 10-fold cross-validation (80% training/20% testing) repeated 5 times with identical random seeds for comparability. Reported metrics:

-

Accuracy = 0.92.

-

Execution time (per run) ≈ 0.45 s on the reported computational environment (see Methods).

-

Stability index (across 20 independent runs) = 0.89.

-

Sensitivity = 0.85; Specificity = 0.88; Precision = 0.82; AUC = 0.91.

Comparative benchmarking (Table 2) showed FICA outperforming alternative algorithms in accuracy and stability for cluster detection with similar or better execution time than most alternatives.

Discussion

In this study we applied a Fuzzy Irregular Cellular Automata (FICA) framework to an integrated ergonomic dataset from 415 industrial workers to characterize musculoskeletal abnormalities, their associations with musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs), and to prioritize feasible interventions. Our principal findings were threefold. First, structural abnormalities were highly prevalent in this supervisory/administrative workforce: 97% of participants had at least one abnormality, with lumbar lordosis (62%) and dropped shoulder (50%) being the most common. Second, demographic factors — notably BMI, age, and accumulated work experience — were significant predictors of abnormality burden (multivariate R² = 0.43, p < 0.001) and of individual abnormality odds (for example, BMI ≥ 30: OR = 2.3 for lumbar lordosis). Third, the FICA model produced interpretable, network-level clusters (e.g., Cluster 1: lumbar lordosis + dropped shoulder, 22.2%) and prescriptive outputs (ranked interventions and estimated risk reductions) with high predictive performance (accuracy = 0.92; stability index = 0.89). Taken together, these results confirm the heavy ergonomic burden in office-based industrial work and demonstrate how a graph-based fuzzy framework can both clarify interdependent risks and inform prioritized, practical responses.

Our prevalence estimates and the identified role of BMI, age, and work experience are consistent with prior epidemiological and ergonomic studies. The observed lumbar-dominant burden resonates with global estimates of occupational low back pain and supports the assertion that low back complaints remain one of the most important workplace health problems24. Similarly, the link between obesity and increased risk for spinal and lower-limb abnormalities aligns with prior analyses indicating that excess body mass exacerbates mechanical loading and predisposes to postural deviations and pain25. The association of long work experience with cumulative structural changes echoes longitudinal and cross-sectional evidence implicating prolonged exposure to non-neutral postures and repetitive loading in chronic musculoskeletal outcomes26. These concordant findings strengthen confidence in our measurement approach and provide a robust epidemiological context for the modeling results.

Beyond reproducing known risk patterns, the FICA model yielded network-level insights that extend conventional analytic approaches. Traditional regression models are well suited to estimate independent associations of risk factors with single outcomes but are limited in revealing how abnormalities co-occur and interact as coupled systems. By representing workers and abnormalities as nodes in an irregular graph and propagating graded (fuzzy) severity states via Mamdani inference, FICA uncovered interdependent pathways — for example, an indirect pathway in which lumbar lordosis influences dropped shoulder through an intermediate relation with genu varum (standardized indirect β = 0.32, p < 0.01). This kind of emergent, pathway-level finding is difficult to identify with standard methods and suggests compensatory or mechanical linkages between spinal alignment and lower-limb posture that merit biomechanical and longitudinal investigation. In this way, FICA complements rather than replaces regression-based modeling: it provides a systems-level lens that highlights clusters of co-occurring abnormalities and the potential mechanisms that tie them together, consistent with recent calls to move ergonomic assessment beyond isolated risk-factor lists and toward network-aware analyses27.

Importantly, the FICA approach addresses two pragmatic challenges in workplace ergonomics: uncertainty in measurement and the need for prioritized interventions under resource constraints. The fuzzy-state mapping (e.g., mild = 0.3, moderate = 0.6, severe = 0.9) tempers binary thresholds and reduces the sensitivity of outputs to arbitrary cut-points, improving robustness to self-reported or noisy measures — an advantage noted in prior discussions of measurement error in occupational health surveys28. Concurrently, the FICAVCA voting/colouring routine produces ranked intervention candidates that are directly actionable for occupational health teams. In our cohort, FICA prioritized backrest adjustment and posture training for Cluster 1, combined workstation and lower-limb exercise programs for Cluster 2, and monitor/desk adjustments plus neck/shoulder conditioning for Cluster 3. Model-based intervention simulations suggested modest to meaningful reductions in cluster risk (for example, backrest adjustment ~ 18% reduction; corrective exercise ~ 22%; combined measures up to ~ 34%), which if validated in pragmatic trials could inform cost-effective implementation strategies in constrained industrial settings25.

The study also provides convergent findings from biomechanical modeling and workstation assessment that help translate cluster outputs into concrete ergonomic fixes. Although 3DSSPP analyses indicated that instantaneous joint loads were within static safety limits for most postures (97% considered “safe” under static assumptions), exposure-time assessment revealed excessive posture maintenance in a large proportion of workers (79.4% with prolonged uninterrupted seated durations). This pattern — safe instantaneous postures coupled with high cumulative exposure — helps explain why structural abnormalities and MSDs remain prevalent despite apparently acceptable momentary postures, and it underscores the importance of temporal metrics in ergonomic evaluation10,29. Likewise, our finding that workstation mismatches (backrest, seat depth, desk height) correlated with abnormalities (r ≈ 0.51, p < 0.001) reaffirms the role of poor workstation fit in promoting postural deviations30and supports the practical emphasis of FICA on workstation adjustments as first-line measures.

Study limitations and future research

We acknowledge several limitations that temper interpretation and motivate future work. First, the cross-sectional and single-site design limits external generalizability and precludes causal inference; longitudinal follow-up is required to verify whether FICA-identified clusters predict incident MSDs and whether prioritized interventions produce the modeled risk reductions in practice. Second, although we combined objective measures with interviewer-administered questionnaires to mitigate reporting bias, the reliance on any self-reported symptom data introduces potential recall or desirability biases that could influence certain associations; integration of wearable sensor data would strengthen future inferences. Third, FICA’s outputs depend on fuzzy-rule definitions, membership choices, and graph-construction thresholds; although we performed sensitivity analyses and report a stability index of 0.89, external replication and consensus-driven rule calibration would further enhance robustness. Finally, the intervention effect estimates are model projections derived from mapped effect-size parameters and should be validated in implementation trials before being used for definitive policy-making. Finally, our intervention impact estimates are model-based projections from scenario simulations within FICA rather than observed trial outcomes. While simulations provide useful prioritization guidance, randomized or pragmatic implementation studies are necessary to verify the real-world effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the prioritized interventions.

Despite these limitations, the study has practical and theoretical implications. Practically, FICA can be deployed as part of a stepped occupational health response: rapid screening to detect high-prevalence clusters, targeted low-cost workstation fixes for top-ranked clusters, and follow-up monitoring to assess intervention uptake and outcomes. The model’s computational efficiency (mean run time ~ 0.45 s) and interpretability facilitate such integration into routine workplace health programs. Theoretically, FICA demonstrates the value of hybrid fuzzy-graph methods in ergonomics research: they expand analytic capacity from isolated risk estimation to network discovery and prescriptive prioritization, addressing calls in the literature for more holistic and implementable ergonomic analytics16,27,31.

Our ergonomic risk assessment of 415 workers at an industrial company in Sirjan, utilizing the Fuzzy Irregular Cellular Automata (FICA) model, provides a robust framework for understanding the complex interplay between musculoskeletal abnormalities, MSDs, demographic factors, and workplace ergonomic conditions. The high prevalence of musculoskeletal abnormalities (97% of participants, including 62% with lumbar lordosis and 50% with dropped shoulders) and MSDs (45% prevalence, with 35.9% reporting low back pain) aligns with global trends reported in the ergonomic literature. For instance, Hoy et al. reported that low back pain affects approximately 38% of the global working population, highlighting its significance as an occupational health issue24. These findings are also consistent with the results of Karimi et al., who demonstrated that static, prolonged postures and inadequate workstation design exacerbate abnormalities of the spine and lower limbs32. The FICA model’s ability to represent these abnormalities as nodes in a graph, with edges signifying relationships such as correlations with BMI or workstation mismatches, allowed for a precise analysis of these interactions, overcoming the limitations of traditional linear models.

Conclusion

In this study we developed and validated a Fuzzy Irregular Cellular Automata (FICA) framework to integrate multi-modal ergonomic data and support prioritized risk management in an industrial workforce. The model met the study objectives by1 identifying interpretable high-risk clusters of musculoskeletal abnormalities2, quantifying their associations with MSD outcomes and key demographic predictors, and3 producing ranked, actionable intervention recommendations for resource-targeted implementation. FICA demonstrated strong predictive performance and stability, and its fuzzy-graph representation revealed network-level relationships—such as co-occurring spinal and shoulder abnormalities—that are not easily captured by conventional regression approaches.

The results are most directly applicable to industrial and manufacturing settings—for example, metal processing, heavy manufacturing, and production facilities—particularly where work includes a mix of seated supervisory/administrative tasks and production-adjacent activities that produce prolonged static postures or frequent transition between seated and standing work. The approach is also immediately relevant to office-based work within industrial enterprises (control rooms, production supervision, and back-office operations) where workstation fit, prolonged sitting, and repetitive upper-body tasks are common.

With appropriate adaptation and local validation, the FICA framework can be extended to other sectors that face ergonomic challenges but differ in exposure patterns. For example, transportation (professional drivers, vehicle operators), healthcare and service sectors (nursing, retail), and education (teachers, laboratory staff) could benefit from FICA-based screening if the model inputs are adjusted to reflect sector-specific tasks, exposure-time profiles, and relevant abnormality sets. Such adaptations typically require (a) changing the node/feature set to include sector-relevant measurements, (b) recalibrating fuzzy membership functions and rule bases to reflect different exposure–outcome relationships, and (c) performing local validation (preferably longitudinal) to confirm predictive and prescriptive performance.

Because the intervention impact estimates reported here are model projections, we recommend that occupational health teams pilot FICA-guided interventions in their specific operational context and collect follow-up outcome data to confirm effectiveness. Future work should therefore prioritize multi-site replication, longitudinal validation, and integration with wearable time-series data to strengthen causal inference and enable scalable deployment. Overall, FICA offers a promising, adaptable framework to improve the efficiency and targeting of ergonomic interventions across industrial settings, and—with appropriate customization—across other sectors facing distinct ergonomic exposures.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Korhan, O. Work-related Musculoskeletal Disorders (BoD–Books on Demand, 2019).

Clemente, A. & Carvalho, F. Ergonomic work analysis in the production of interiors for the transport industry. Human Factors and Systems Interaction (AHFE 2023)—AHFE Open Access; Nunes, IL, Ed. :336–46. (2023).

Stehle, S. A. et al. Predicting postural control adaptation measuring EEG, EMG, and center of pressure changes: BioVRSea paradigm. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 16, 1038976 (2022).

Bertoncelli, C. M. et al. Identifying postural instability in children with cerebral palsy using a predictive model: a longitudinal multicenter study. Diagnostics 13 (12), 2126 (2023).

Mosavianasl, Z., Nemati Ajvadi, A. & Babayi Pouya, A. Evaluation of workplaces and corrective actions in the central Iranian steel industries. Archives Hygiene Sci. 7 (3), 208–215 (2018).

Shaikh, A. M., Mandal, B. B. & Mangalavalli, S. M. Causative and risk factors of musculoskeletal disorders among mine workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Saf. Sci. 155, 105868 (2022).

Shaikh, A. M., Sharma, A. & Mandal, B. B. Assessing whole-body vibration and musculoskeletal disorders among shuttle car operators in underground mines: an epidemiological perspective on occupational health and safety. Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration. :1–13. (2025).

Ruennusan, M., Chaikittiporn, C., Taptagaporn, S. & Boonshuyar, C. Development of an ergonomics risk assessment tool for repetitive task assessment (RTRA). Work 74 (4), 1595–1611 (2023).

Tang, K. H. D. Abating Biomechanical risks: A comparative review of ergonomic assessment tools. J. Eng. Res. Rep. 17 (3), 41–51 (2020).

Johnson, W., Koshy, J. M. & Rajasundram, A. Analysis of workstation posture in diversified professionals as a tool to enhance better Understanding of health outcomes to avoid occupational health hazards. J. Anat. Soc. India. 71 (2), 114–118 (2022).

Hu, X. et al. Identification of fuzzy rule-based models with collaborative fuzzy clustering. IEEE Trans. Cybernetics. 52 (7), 6406–6419 (2021).

Moghari, S. Synthesizing fuzzy tree automata. RAIRO-Theoretical Inf. Appl. 56, 6 (2022).

Lefevr, N., Kanavos, A., Gerogiannis, V. C., Iliadis, L. & Pintelas, P. Employing fuzzy logic to analyze the structure of complex biological and epidemic spreading models. Mathematics 9 (9), 977 (2021).

Ahn, S. et al. (eds) A fuzzy logic based machine learning tool for supporting big data business analytics in complex artificial intelligence environments. IEEE international conference on fuzzy systems (FUZZ-IEEE); 2019: IEEE. (2019).

Liu, Y., Yu, X., Zhao, J., Pan, C. & Sun, K. Development of a robust data-driven soft sensor for multivariate industrial processes with non-Gaussian noise and outliers. Mathematics 10 (20), 3837 (2022).

Kuorinka, I. et al. Standardised nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Appl. Ergon. 18 (3), 233–237 (1987).

Mokhtarinia, H., Shafiee, A. & Pashmdarfard, M. Translation and localization of the extended nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire and the evaluation of the face validity and test-retest reliability of its Persian version. Iran. J. Ergon. 3 (3), 21–29 (2015).

Stomfai, S. et al. Intra-and inter-observer reliability in anthropometric measurements in children. Int. J. Obes. 35 (1), S45–S51 (2011).

Ulijaszek, S. J. & Kerr, D. A. Anthropometric measurement error and the assessment of nutritional status. Br. J. Nutr. 82 (3), 165–177 (1999).

Schwartz, A. H., Albin, T. J. & Gerberich, S. G. Intra-rater and inter-rater reliability of the rapid entire body assessment (REBA) tool. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 71, 111–116 (2019).

Sadeghi, F., Mazloumi, A. & Kazemi, Z. An anthropometric data bank for the Iranian working population with ethnic diversity. Appl. Ergon. 48, 95–103 (2015).

Asadi, N., Choobineh, A., Keshavarzi, S. & Daneshmandi, H. Estimation of forces exerted on the lower back in manual load lifting using 3DSSPP software. Iran. J. Ergon. 2 (4), 25–31 (2015).

Kashani, M., Gorgin, S. & Shojaedini, S. V. A fuzzy irregular cellular automata-based method for the vertex colouring problem. Connection Sci. 32 (1), 37–52 (2020).

Hoy, D. et al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthr. Rhuem. 64 (6), 2028–2037 (2012).

Lowe, B. D., Dempsey, P. G. & Jones, E. M. Ergonomics assessment methods used by ergonomics professionals. Appl. Ergon. 81, 102882 (2019).

Viester, L. et al. The relation between body mass index and musculoskeletal symptoms in the working population. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 14 (1), 238 (2013).

Coenen, P., Kingma, I., Boot, C. R., Bongers, P. M. & van Dieën, J. H. Cumulative mechanical low-back load at work is a determinant of low-back pain. Occup. Environ. Med. 71 (5), 332–337 (2014).

Bonfiglioli, R., Caraballo-Arias, Y. & Salmen-Navarro, A. Epidemiology of work-related musculoskeletal disorders. Curr. Opin. Epidemiol. Public. Health. 1 (1), 18–24 (2022).

Vaughn, D. W. & Brown, E. W. The influence of an in-home based therapeutic exercise program on thoracic kyphosis angles. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 20 (4), 155–165 (2007).

Bontrup, C. et al. Low back pain and its relationship with sitting behaviour among sedentary office workers. Appl. Ergon. 81, 102894 (2019).

Waller, E., Bowens, A. & Washmuth, N. Prevalence of and prevention for work-related upper limb disorders among physical therapists: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 23 (1), 453 (2022).

Janbozorgi, A., Karimi, A., Rahnama, N., Karimian, R. & Ghasemi, G-A. The ergonomic analysis of the musculoskeletal risk of teachers by QEC method and the effect of 8 weeks selective corrective exercises and the ergonomic intervention on their encountering. J. Res. Rehabilitation Sci. 8 (5), 919–927 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the participants for their cooperation in this research.

Funding

This study was supported by Sirjan School of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 401000021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SB and AZ analyzed and interpreted participants’ data on MSDs. MK performed data modeling and played a critical role in writing the manuscript. AZ and MBJ managed the project and methodology and performed the final editing of the manuscript. MAM and MS collected data in the field and assisted in preparing the primary information. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sirjan School of Medical Science (Ethics Code: IR.SIRUMS.REC.1402.007). The written informed consent from all participants were obtained, and data confidentiality was maintained through anonymous coding. There were no risks to the participants, and the results were reported without identifying individuals. In the computational model, we examined potential biases (such as gender) through weight adjustments. The study adheres to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the data were used solely for research purposes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kashani, M., Zare, A., Barzekar, S. et al. Optimizing ergonomic risk assessment using fuzzy irregular cellular automata: a novel approach to modeling musculoskeletal disorders in industrial workstations. Sci Rep 15, 44815 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28916-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28916-4