Abstract

As urbanization accelerates, the safety threats confronting buildings have grown increasingly severe, with terrorist attacks and accidental explosions occurring with greater frequency. Open-web sandwich plate structures, a novel structural form, have seen widespread application in engineering construction due to their advantages, including superior overall integrity, high stiffness, lightweight properties, large spanning capacity, space efficiency, aesthetic appeal, and facilitation of equipment and pipeline installation. However, the dynamic response mechanisms and blast resistance performance of such structures under near-field explosion loads remain critical topics requiring further exploration. To date, domestic and international scholars have primarily focused on theoretical analyses, quasi-static investigations, and seismic performance studies of open-web sandwich plate structures, with limited research dedicated to understanding the overall structural behavior of these systems under near-field explosion loads conditions. To mitigate the risks of explosions in open-web sandwich plate structures threatening human life, property safety, and causing adverse societal impacts, this study investigates the dynamic response of open-web sandwich plate structures under near-field explosive loads. A two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure was selected as the research subject. The finite element Coupled Eulerian–Lagrangian numerical simulation method was employed to analyze its dynamic response under near-field explosive loads, while simultaneously investigating the failure modes and underlying mechanisms of the structure. Through this investigation of two-layer open-web sandwich plate structures, a more comprehensive understanding of their dynamic response and failure mechanisms under actual near-field explosion loads is expected to be achieved. This research not only offers more effective guidance for enhancing the blast resistance performance of open-web sandwich plate structures but also provides a robust reference framework for the blast-resistant design of overall building structures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

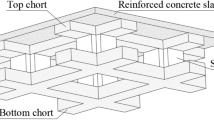

As urbanization accelerates, multi-story and high-rise building structures have become increasingly prevalent in urban construction, with the safety threats to the overall structural integrity of buildings growing progressively severe. Concurrently, the frequent occurrence of terrorist attacks and accidental explosions has further compromised the safety of building structures. As a novel building structure, the reinforced concrete open-web sandwich plate structure, as shown in Fig. 1, is a new type of open-web girder structure composed of reinforced concrete plate, top ribs, and bottom ribs connected by shear keys. It can also be regarded as a hollow-core structure formed by an top reinforced concrete plate and multiple bottom open-web girders, where the open-web girders are composed of top ribs, bottom ribs, and shear keys. The specific composition can be observed in Fig. 1. Since the 1980s and 1990s, open-web sandwich plate structures have gained widespread application in engineering practice due to their advantages: high integrity, superior rigidity, light self-weight, large span capacity, high space utilization, aesthetically pleasing appearance, and ease of equipment and piping installation.

However, existing research has primarily focused on theoretical analysis, quasi-static investigations, and seismic performance evaluations of open-web sandwich plate structures, while systematic investigations into their dynamic response under near-field explosion loads remain limited. For example, Tan et al.1 conducted static load tests on an actual engineering project involving an open-web sandwich plate floor structure. They investigated the mechanical behavior of the top and bottom ribs and shear keys in an orthogonal diagonal steel grid open-web sandwich plate, as well as the deformation patterns of the floor structure. The results demonstrated that this novel floor structure exhibits favorable overall integrity and excellent 3D spatial load-bearing capacity. Sun et al.2 developed a formula for the equivalent shear stiffness of steel open-web sandwich plate structures based on the principle of structural equivalence. Through progressive analysis, they derived analytical solutions for the structure under four-sided simply supported boundary conditions. Using the same case study, they compared the results of continuous analysis with those from finite element analysis. The findings revealed that the deflection errors between the two methods were within 5%, and the axial force errors of the lower chord members were within 15%; thus, the continuous analysis method for static calculations of steel open-web sandwich plate structures exhibits high accuracy. Wu et al.3 proposed replacing the primary components of open-web sandwich plates with H-shaped steel composite members to form a steel–concrete composite open-web sandwich plate floor system. Via case studies, they compared this design with U-shaped steel plate-concrete composite open-web sandwich plate configurations and conducted rare earthquake triaxial dynamic elastic–plastic analysis. The results indicated that this structure performs well in multi-story, long-span buildings, satisfying both load-bearing requirements and normal service conditions while demonstrating favorable seismic performance, making it suitable for structures with larger spans. Fan et al.4 systematically investigated the influence of shear key capacity on the overall structural load-bearing capacity of open-web sandwich plate structures. Based on their research, they proposed design calculation formulas for shear keys applicable to engineering practice.

Meanwhile, Zhang et al.5 developed a novel bending theory for open-web sandwich plates via Fourier integral transforms and mechanical asymptotic methods under strong boundary constraints; finite element analysis (FEA) showed ≤ 2.42% deviation from Matlab-derived theoretical values, validating high accuracy for internal force/deformation calculations. Liu et al.6 used material orthogonality between equivalent thin plates and open-web sandwiches to derive rib parameters, established an energy function for geometric nonlinear vibration, and obtained elliptic-function free-vibration solutions via Galerkin’s method. Simulations revealed complex responses (e.g., alternating periodicity from modal superposition) in orthotropic plates, deepening understanding of hollow sandwich vibration. Yu et al.7 performed full-scale static tests on a 10-m simply supported open-web sandwich bridge, finding substantial safety margins persisted in the steel–concrete section after lower chord yielding. Wang et al.8 derived natural frequency formulas for reinforced concrete open-web sandwiches using Reissner’s theory and Hamilton’s variational principle; SAP2000 FEA validated these against analytical results across support conditions.

To date, research on the blast resistance of building structures has primarily centered on specific structural components, with limited investigations into the holistic blast resistance of entire structures. For example, Chen et al.9 conducted experimental studies on nine full-scale reinforced concrete shear walls under diverse blast loads, measuring front-side reflected overpressure, and back-side acceleration and displacement. They systematically investigated the dynamic response characteristics and damage features of reinforced concrete shear walls under blast loading, and established a failure assessment methodology for such walls under explosive loads. Jiang et al.10 developed a rapid damage prediction model for reinforced concrete columns based on graph neural networks (GNN), which overcomes the inherent limitations of pixel-based machine learning methods in handling three-dimensional spatial topological structures. Additionally, this model delivers consistently high-precision damage predictions across diverse explosive scenarios, demonstrating exceptional stability.

Kong et al.11 integrated parametric modeling with Gaussian process regression analysis to develop a surrogate model for predicting the dynamic response of thermoplastic fiber-reinforced metal laminates, aiming to investigate their dynamic response and failure behavior under constrained explosion conditions. Yao et al.12 proposed two equivalent methods—the mass equivalence method and the deformation energy equivalence method—and conducted two explosion experiments with varying dimensions and explosive masses to evaluate their equivalence effects. They analyzed the damage characteristics of both reinforced plates and equivalent plates; results revealed that mass-equivalent plates exhibited greater deformation than reinforced plates, whereas energy-equivalent plates displayed the opposite trend.

In addition, Liu et al.13 conducted experimental and numerical simulation analyses to compare the dynamic strain responses at the center of circular plates of varying thicknesses under conditions with and without water coverage. They further established a finite element model to analyze the maximum equivalent strain and maximum displacement at multiple locations on the water-covered plate. The results indicated that water presence exerts a significant damping effect on vibration attenuation, not only reducing the maximum response peak but also effectively decreasing the number of vibrations under high-strain conditions. Cong et al.14 proposed a scaling method for the global–local responses of reinforced concrete members based on Buck’s theorem, which was validated against experimental results of reinforced concrete members (e.g., floor slabs and beams) under near-field explosive loads. The validated model could accurately predict the global–local responses of the prototype structure. Subsequently, they proposed a refined scaling method accounting for strain rate and size effects, and investigated common issues such as reinforcement ratio distortion in model tests and the influence of constitutive equations on scaling results. Wang et al.15 designed three 2500 mm-long, 200 mm-diameter concrete-steel double-wall pipe components and conducted experimental and numerical analyses to evaluate their dynamic responses under near-field explosive loads. The results revealed that under close-range explosive loading, these components exhibit highly localized failure modes, including FRP pipe fracture and concrete fragmentation. Wang et al.16 fabricated five reinforced concrete slabs and performed contact explosion tests under varying explosive load equivalents to evaluate the influences of T63 reinforcing bars and ultra-high-performance concrete on slab macro-damage, damage patterns, and dynamic stress–strain responses. The study demonstrated that compared to slabs with HRB400 reinforcing bars, those with T63 reinforcing bars exhibited reduced damage and lower peak acceleration responses under equivalent explosive loads, indicating superior blast resistance performance.

In summary, this paper reviews the current research status of open-web sandwich plate structures and blast resistance in building structures. The analysis reveals that current blast resistance studies on building structures primarily focus on small-scale structures and critical components, with limited attention to the overall structural integrity. As open-web sandwich plate structures are increasingly being used in construction, their overall blast resistance is facing growing challenges. To prevent explosion incidents involving open-web sandwich plate structures from threatening human life and property safety and mitigate their negative societal impacts, this study uses finite element numerical simulations to investigate the dynamic response of two-layer open-web sandwich plate structures under near-field explosion loads. Additionally, it analyzes the failure modes and mechanisms of these structures. This investigation into the dynamic response of two-layer open-web sandwich plates under near-field explosion loads not only provides critical guidance for blast-resistant design of building structures but also offers a scientific foundation for future engineering applications and dynamic response analysis, with significant theoretical and practical value.

Material models and validation of material parameter validity

Material models

Concrete material modeling

In this study, the JH-2 constitutive model17,18 was used to describe the material properties of concrete. This model includes a strength model, a damage model, and a state equation.

Strength model

The strength model is categorized into intact, damaged, and fractured states based on the damage factor D. Figure 2a illustrates the correlation between normalized equivalent stress and normalized hydrostatic pressure. The relevant parameters are shown in Table 1.

a. intact state: D = 0

b. damage state: 0 < D < 1

c. fracture state: D = 1

Damage model

As illustrated in Fig. 2b, the cumulative calculation formula for fracture damage is expressed as:

where \(\Delta {\varepsilon }^{p}\) represents the increment in equivalent plastic strain, \({\varepsilon }_{f}^{p}\) represents the equivalent plastic strain to fracture under constant pressure, \({\text{D}}_{1}\) and \({\text{D}}_{2}\) represents material parameters.

State equation

As depicted in Fig. 2c, the state equation for the constitutive parameters of the C35 concrete JH-2 model is presented below:

a. When the material is not damaged (D = 0), the equation is:

b. Once damage accumulation commences (D > 0), an incremental pressure ΔP must be incorporated, described by the equation:

The pressure increment is governed by the energy factor, as expressed by the equation:

In the equation, β denotes the fraction of elastic energy loss converted into potential hydrostatic energy (0 < β < 1), where \(\Delta {\text{U}}\) signifies the instantaneous damage energy.

The constitutive parameters of concrete in this study were fitted based on the values in Reference19, as shown in Table 2. The control parameters not provided were obtained through numerical simulation, as shown in Table 3.

Material model for steel

The Johnson–Cook constitutive model20 is used for the reinforcing steel constitutive model. Equation 9 defines the yield stress equation, the relevant parameters are shown in Tables 4, and 5 lists the corresponding parameters

Material model for explosive

To better simulate the scene of an explosive (TNT) explosion, this study used the Jones Wilkins Lee (JWL) formula of state21. The relevant parameters are shown in Table 6, and the material parameters and state equation of explosives are shown in Table 7.

Material model for air

Using the EOS of an ideal gas, the equation of state for the gas is as follows22. The relevant parameters are shown in Table 8. The material parameters and state equation of air are shown in Table 9.

Validation of material parameter validity

When investigating the dynamic response of open-web sandwich plates under near-field explosive loads, this study employed a finite element numerical simulation method owing to the high experimental costs and limited testing facilities. During the research process, validating the material constitutive model parameters was necessary. In prior studies, the validity of these parameters had been verified via simulations of reinforced concrete beams23 and plates24, with partial comparison plots presented in Figs. 3 and 4. Figure 3 shows a comparison between experimental results and numerical simulation results for the frame structure beam. Figure 4 shows the comparison between experimental results and numerical simulation results for reinforced concrete.

Figure 3 compares numerical simulations with experimental results for reinforced concrete beams in a frame structure subjected to near-field blast loads, focusing on the beam’s dynamic response. When TNT mass was 4 kg, explosion height was 0.5 m, and the proportional distance Z = 0.31 m/kg1/3, significant bending and crushing damage occurred in the mid-span region of the beam. Specific data indicate that the lengths of the damaged regions in the beam mid-span were 50 cm and 53 cm in the test and simulation, respectively (error 6%); the lengths of exposed reinforcement on the blast-facing side were 30 cm and 34 cm (error 13.3%); concrete on the non-blast-facing side remained uncrushed in both cases; and the maximum mid-span displacements were 42 mm and 39.7 mm (error 5.5%). In summary, this numerical simulation effectively reproduces the explosion test process of the beam.

Figures 4a and b compare simulation results with Eulerian grid sizes of 10 mm and 15 mm against experimental data for a 2 kg TNT charge (explosion height 0.5 m, proportional distance 0.4 m/kg1/3). In the experiment, the blast-facing side of the reinforced concrete slab exhibited clear blast marks but no damage, while the non-blast-facing side showed no changes. The maximum displacement at the center was 10 mm. Both simulation results with different mesh sizes matched this damage characteristic, with maximum displacements at the center of 11.3 mm and 8.4 mm, respectively. Figure 4c and d compare results for the 4 kg TNT case (explosion height 0.5 m, proportional distance 0.31 m/kg1/3). In the test, the rear face of the slab exhibited central spalling damage (approximately 70 cm diameter) with a maximum central displacement of 24.7 mm. The 10 mm grid simulation predicted a damage diameter of 74 cm (error 5.7%). (Note: Letter (a) indicates the comparison between numerical simulation test results and explosion test results for reinforced concrete slabs with 10 mm and 15 mm grid sizes on the blast-facing side at a proportional distance of 0.40 m/kg1/3; Letter (b) indicates the comparison between numerical simulation test results and explosion test results for reinforced concrete slabs with 10 mm and 15 mm grid sizes on the blast-back side at a proportional distance of 0.40 m/kg1/3; Letter (c) indicates the comparison between numerical simulation test results and explosion test results for reinforced concrete slabs with 10 mm and 15 mm grid sizes on the blast-facing surface at a proportional distance of 0.31 m/kg1/3; Letter (d) indicates the comparison between numerical simulation test results and explosion test results for reinforced concrete slabs with 10 mm and 15 mm grid sizes on the blast-rear surface at a proportional distance of 0.31 m/kg1/3.)

By conducting explosion tests on reinforced concrete beams and plates under near-field explosion loads, this study compared and analyzed key dynamic response characteristics—including the extent of damage, damaged areas, and maximum vertical displacement—between numerical simulation results and experimental test outcomes. The comparative analysis demonstrates that the finite element CEL method is feasible for simulating the dynamic response of open-web girders and open-web sandwich plate floor structures under near-field explosion loads, thereby providing methodological and technical support for further investigations into the dynamic behavior of open-web sandwich plate structures under such loading conditions.

Study on the dynamic response of open-web sandwich plate structures under near-field explosive loads

Open-web sandwich plate structural model parameters

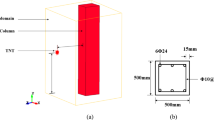

The modeling data in this study were designed in accordance with the relevant specifications for open-web sandwich plate structures25, as illustrated in Fig. 5. The open-web sandwich plate structure comprises reinforced concrete plates, top ribs, bottom ribs, and shear keys. Its structural configurations are depicted in Figs. 5b and c, while the associated dimensional and reinforcement details are presented in Figs. 5d and e. Figure 5a shows a schematic diagram of the double-layer perforated mesh open-web sandwich plate structure; Fig. 5b presents the plan layout of the double-layer perforated mesh open-web sandwich plate structure, where u, v, and w denote the cross-sections at their respective locations; Fig. 5c displays the sectional view of Sect. 1–1, while sections A-A and B-B in Fig. 5c represent the open-web girder section and shear key section, respectively; Fig. 5d shows the dimension drawing and reinforcement detailing of the PQ open-web girder; Fig. 5e presents the sectional views of sections C–C and D–D. This investigation focuses exclusively on the structural components defined by the numerical simulation design, neglecting the impacts of infrastructure and auxiliary facilities on the simulation outcomes. During the numerical simulation, the bases of the concrete columns underlying the two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure were constrained using fixed constraints. Furthermore, to address the discrepancy between numerical simulations and explosive tests, enhance the realism of the simulation, comprehensively investigate the overall blast resistance performance of the open-web sandwich plate structure, and mitigate the influences of local effects on the results, TNT charges were positioned 0.75 m directly above the center of the second-floor plate in this numerical simulation. This configuration of TNT charges fulfills two key objectives: first, it enables parametric investigations of the open-web sandwich plate structure; second, it accounts for the propagation characteristics of explosive shock waves and the influence of the air medium, thereby improving the engineering applicability of the research findings.

Materials and modeling parameters

This study employed Abaqus finite element software for modeling, utilizing the concrete constitutive model parameters derived in Chapter 2, along with constitutive parameters for reinforcing bars, TNT explosives, and air sourced from literature (Tables 2, 3, 5, 7, and 9). During numerical modeling, a 26.4 cm-side cubic explosive (30 kg) was positioned at a vertical distance of 750 mm directly above the center of the two-layer hollow-core slab structure, corresponding to an equivalent proportional distance of 0.241 m·kg⁻1/3. To account for air damping effects, both explosive and air materials were defined within the Euler domain with a mesh size of 100 mm. Concrete and reinforcing bars were modeled with a finer mesh size of 40 mm, and the reinforcing bars were embedded into the concrete.

Damage analysis

Analysis of concrete damage

To investigate the damage response characteristics of a two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure under near-field explosive loads, a numerical simulation was conducted with a 30 kg explosive charge at an explosion height of 0.75 m. Damage cloud maps of the structure at different time intervals are presented in Figs. 6 and 7, respectively. Analysis of these figures reveals that the central region of the blast-facing surface of the two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure presents a semi-circular indentation under the explosion shock wave, though the indentation remains relatively minor. Meanwhile, the central region of the blast-facing surface of the second-floor plate exhibits typical cross-shaped and square damage zones, while the blast-back surface displays cross-shaped and circular damage zones. Furthermore, minor concrete spalling is observed at the central region of the blast-facing surface of the second-floor plate, with extensive cracking and damage present on both the blast-facing and blast-back surfaces. No obvious damage is observed at the central region of the blast-facing surface of the first-floor plate; however, similar-sized cracks develop at the column-plate connections. Reflection of the explosion shock wave leads to similar square damage regions around the columns, while no obvious damage is observed on the blast-back surface of the first-floor plate.

In summary, analysis of the numerical simulation results reveals that the top ribs, bottom ribs, shear keys, and column connections of the first- and second-floor plates have sustained varying degrees of damage with numerous cracks, with the second-floor plate experiencing relatively more severe damage. Based on the damage condition analysis of the two-story open-web sandwich plate structure, the second-floor plate is evident to have sustained significantly more damage than the first-floor plate. However, the overall functional integrity of the structure remains unaffected, providing a foundation for further research on displacement and stress analysis of open-web sandwich plate structures.

Analysis of steel reinforcement damage

Figure 8 presents the damage distribution cloud maps of reinforcing bars in a two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure under explosive loading at distinct time points. Analysis of these maps indicates that during the initial explosion phase, the explosive shock wave first reaches the central region of the second-floor plate, inducing tensile stress in the reinforcing bars of this area initially, while reinforcing bars in other regions remain unaffected by the shock load. As the shock wave propagates further, reinforcing bars in both the first and second-floor plates become influenced by the shock wave. Notably, the damage cloud maps clearly reveal that within each floor plate, reinforcing bars in the upper layer of the upper flange consistently exhibit higher stress levels than those in the lower layer of the upper flange, and reinforcing bars in the lower layer of the lower flange consistently display higher stress than those in the upper layer of the lower flange. Under explosive loading, the reinforcing bars first undergo yielding under tensile stress, resulting in a reduction of the structure’s overall stiffness. Sustained explosive shock loads may induce significant plastic deformation in the reinforcing bars, thereby adverse affecting the structure’s load-bearing capacity. Furthermore, under repeated explosive shock loading, reinforcing bars in stress concentration zones may experience fatigue failure. Eventually, when the stress on the reinforcing bars exceeds their ultimate strength, the bars will fracture and fail, completely losing their load-bearing capacity.

Displacement analysis

Vertical displacement analysis

To investigate the vertical displacement response characteristics of a two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure under near-field explosion loads, the locations of shear keys at the most severely damaged sections of the second-floor and first-floor plates were extracted. The displacement time-history curves are presented in Fig. 9. As shown in Fig. 9, the second-floor plate exhibits a more pronounced displacement response under near-field explosion loading. The maximum displacement at the center of the second-floor plate directly below the explosion point is 96.33 mm, whereas the maximum displacement at the corresponding location on the first-floor plate is 32.05 mm, highlighting a notable discrepancy between the two plates. Additionally, Fig. 9 reveals a time lag between the first-floor and second-floor plates in reaching their peak displacements. The following factors are primarily responsible for this phenomenon: First, the explosion-generated shock wave initially acts on the second-floor plate, with partial energy absorbed and dissipated by the plate through material plastic deformation and cracking26,27. Second, after propagating through the second-floor plate, the intensity of the explosion load transmitted to the first-floor plate is significantly reduced, as the shock wave attenuates with increasing propagation distance in air26,27. Third, during shock wave propagation between the floor slabs, reflection and interference phenomena occur, altering the load distribution and intensity28. The analysis of the maximum displacement of the two-story open-web sandwich plate structure provides a critical reference for subsequent investigations into structural failure modes and mechanisms.

To investigate the vertical displacement behavior of a two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure under near-field explosive loads at two distinct time points (10 ms and 20 ms), vertical displacement data of the lower portion of the open-web girder PQ structure were extracted from Fig. 5c and are presented in Fig. 10. As shown in Fig. 10, under a 30 kg TNT explosive charge at an explosion height of 0.75 m, the maximum vertical displacement at the center of the second-floor plate of the two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure reaches 83.86 mm, whereas the maximum vertical displacement at the center of the first-floor plate is 10.32 mm. This indicates a 73.54 mm greater displacement response in the second-floor plate compared to the first-floor plate, highlighting a more pronounced displacement behavior in the upper plate. Additionally, Fig. 10 reveals high similarity in vertical displacements between the first- and second-floor plates at the two time points, which validates the reliability of the numerical simulation results.

In summary, based on the analysis of vertical displacements in the two-story open-web sandwich plate structure under near-field explosion loads, it is recommended that practical engineering designs adopt the following measures to enhance structural stability, improve torque resistance and horizontal force transmission capacity, and prevent premature failure of the open-web sandwich plates: reducing the grid size of adjacent floor plates, installing lateral connections between floor plates, and utilizing high-strength reinforcing bars and concrete materials.

Horizontal displacement analysis

To investigate the horizontal displacement response characteristics of a two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure under near-field explosive loads, horizontal displacement data at points u, v, and w on the cross-sections of two-layer and single-layer floor plates were extracted for analysis. The horizontal displacement curves at four distinct time points are presented in Fig. 11. Figure 11 presents a comparative analysis of horizontal displacements at the u, v, and w sections for two floor slabs in a two-story open-web sandwich plate structure. The locations of the u, v, and w sections are shown in Fig. 5b.

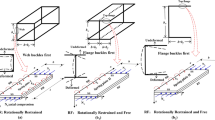

As shown in Fig. 11a, displacements at various points on the top rib, bottom rib, and shear keys of the u-section in the two-layer floor plate are relatively scattered. These displacements deviate from the plane section assumption, primarily due to severe concrete damage in the top rib, bottom rib, and shear keys, which obscures observation of the neutral axis position. Additionally, slippage occurs between the top and bottom ribs under the explosion shock wave. At the u-section of the first-layer floor plate (Fig. 11b), displacements at points on the top rib, bottom rib, and shear key generally conform to the plane section assumption, though slight slippage persists between the top and bottom ribs.

Similarly, at section v of the second-layer floor plate (Fig. 11c), displacements at points on the top and bottom ribs are scattered and deviate from the plane section assumption. This is attributed to the absence of shear keys at this location, which weakens shear resistance, leading to slippage between the ribs and obscuring the neutral axis position. At section v of the first-layer floor plate (Fig. 11d), displacements at points on the top and bottom ribs also deviate from the plane section assumption. The lack of shear keys here results in weak shear resistance, causing slippage between the ribs and preventing clear observation of the neutral axis.

At section w of the second-layer floor plate (Fig. 11e), displacements at points on the upper rib, lower rib, and shear key partially comply with the plane section assumption. Slight sliding occurs between the top and bottom ribs, and the neutral axis position remains unobservable. Similarly, at section w of the first-layer floor plate (Fig. 11f), displacements at points on the top rib, bottom rib, and shear key also partially comply with the plane section assumption, with slight slippage between the ribs and the neutral axis position obscured.

By comparing horizontal displacements at sections u, v, and w of the two-layer and first-layer floor plates (Fig. 11), it is evident that the two-layer floor slab exhibits greater horizontal displacement than the first-layer plate, confirming slippage between the top and bottom ribs under near-field explosive loads. Notably, when shear keys connect the top and bottom ribs, they effectively mitigate rib slippage. Based on these findings, this study recommends increasing the width of shear keys in practical engineering designs to reduce shear deformation, thereby enhancing stability between the upper flange, lower flange, and shear keys. This measure prevents structural accidents caused by rib slippage and improves overall structural safety.

Reinforcing bar stress analysis

To investigate the Mises stress response characteristics of reinforcing bars in a two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure under near-field explosive loads, reinforcing bars at sections u, v, and w of the two-layer and single-layer floor plates were selected for analysis. The Mises stress time-history curves of these reinforcing bars at the three sections are presented in Fig. 12. Figure 12 presents a comparative analysis of the Mises stress in the reinforcement of the u, v, and w sections for two floor slabs in a two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure. The locations of the u, v, and w sections are shown in Fig. 5b.

In Fig. 5c, “f-a” denotes the reinforcement at the intersection of horizontal axis a and vertical axis f; similar labeling conventions apply to the other three locations. Regarding Fig. 12a, the Mises stress values at the h–d, f-d, g-d, and h–d positions (Note: Potential typo correction; adjust labels if needed) are shown. To clearly highlight the differences in Mises stress distribution of reinforcing bars under varying explosion heights, the Mises stress values at four key positions across sections u, v, and w of both the second-floor and first-floor slabs are summarized in Table 10.

In summary, through analysis of the Mises stress time-history curves of reinforcing bars at sections u, v, and w in the cross-sections of the second-floor and first-floor plates of a two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure, the following conclusions can be drawn: When the mass of TNT explosive is constant, reinforcement in the second-floor plate experiences greater explosive impact than that in the first-floor plate. Additionally, at shear key locations, shock wave intensities experienced by the top and bottom ribs display a decreasing trend. Furthermore, within each floor plate, shock wave intensities acting on the upper layer of reinforcement in the top rib are consistently higher than those on the lower layer of the top rib, while shock wave intensities on the lower layer of reinforcement in the bottom rib are consistently higher than those on the upper layer of the top rib. Based on these findings, it is recommended that during the design of reinforcement layouts for open-web sandwich plate structures: (1) the reinforcement content in the upper layer of the top rib and the lower layer of the bottom rib should be appropriately increased to fully utilize the load-bearing capacity of the reinforcement; (2) connecting reinforcement should be used to effectively link shear key nodes with the top and bottom ribs, thereby reducing stress concentration and local bending moments at the nodes, lowering the likelihood of premature structural failure, and enhancing the overall stability of the open-web sandwich plate structure.

Destruction mode and failure mechanism analysis

Destruction mode analysis

In this numerical simulation, when an explosion occurs, the shock wave directly impacts the surface of the second-floor plate, leading to high stress concentration in the upper concrete panel. Due to shock wave reflection within the structure, the blast-impacted surface of the concrete may delaminate. At this stage, the upper plate primarily undergoes overall bending deformation, while the lower plate exhibits shear deformation characteristics under explosive reflection waves, resulting in a wavy deflection pattern. Near the explosion center, concrete may experience crushing failure, along with severe shear failure. As the shock wave propagates through the air, it generates reflected stress waves within the hollow sandwich panel’s cavity, causing debonding between the upper and lower concrete plates and the hollow layer, which leads to interlayer separation. Simultaneously, the cross-shaped shear keys within the cavity are subjected to non-uniform shear stress under explosion loads, resulting in shear fractures or bending plastic hinges and causing excessive loss of local load-bearing capacity. At the connection points between the open-web girders and shear keys, stress concentrations induce 45° diagonal cracks, accelerating the loss of structural continuity and load-bearing capacity.

When the shock wave propagates near the columns, approximately 60–75% of the explosion energy is dissipated through plastic deformation of the interlayer cavity, while the remaining energy is transmitted via support columns to the surrounding structure, aggravating damage in boundary regions. Concurrently, the shock wave generates tensile-shear combined stresses at fixed support corners, initiating radial cracks that extend into the hollow core layer. Finally, when the explosion load reaches a critical threshold, the open-web sandwich plate structure undergoes extensive concrete spalling, plastic bending, and collapse.

Failure mechanism analysis

Failure mechanisms refer to the physical processes and mechanical behaviors through which a structure transitions from its initial state to the complete loss of load-bearing capacity under specific loading conditions. For analyzing the failure mechanisms of two-layer open-web sandwich plate structures under near-field explosive loads, research can be conducted from two key perspectives: material-level failure mechanism analysis and structural response failure analysis.

First, material-level failure mechanism analysis encompasses the examination of failure processes in both concrete and reinforcing steel. Under the action of explosive shock waves, concrete experiences bending stresses, initiating crack formation first in the tension zone. As the shock wave intensity increases, these cracks propagate rapidly, progressively reducing the concrete’s effective load-bearing area. Concurrently, near the explosion epicenter, concrete is subjected to extremely high compressive stresses, potentially leading to crushing failure. When the shock wave propagates to shear keys and columns, concrete in regions with concentrated impact loads becomes prone to shear failure, particularly when shear reinforcement is insufficient. For the reinforcement in open-web sandwich plate structures, tensile stresses induced by the shock wave cause yielding, which reduces the structural stiffness of the open-web sandwich plate. As the shock wave intensity continues to escalate, the reinforcement may ultimately fracture, leading to the loss of load-bearing capacity in the open-web sandwich plate structure.

Next, the failure analysis of two-layer open-web sandwich plate structures is presented, focusing on four distinct structural failure modes: bending failure, shear failure, punching failure, and global instability.

-

(1)

Bending failure: Under near-field explosive loading, the two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure undergoes bending deformation. As the bending deformation angle increases beyond the structural limit, the load-bearing capacity of the structure is exceeded, leading to bending failure.

-

(2)

Shear failure: When subjected to explosive impact loads, shear stresses at the shear keys and column connections exceed the shear strength of the two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure, inducing shear failure.

-

(3)

Punching failure: Under explosive impact loading, a conical failure surface develops in the region of concentrated impact loading within the two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure. Punching failure may occur at the plate locations under such localized impact.

-

(4)

Global instability: When the explosive impact load reaches a critical magnitude, the two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure may experience global instability, leading to structural collapse.

Conclusion

This chapter investigates the dynamic response of a two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure under near-field explosive loads. Through analysis of numerical simulation results—including damage patterns, vertical and horizontal displacement, steel reinforcement Mises stress distribution, failure modes, and failure mechanisms—the following key conclusions are drawn:

-

(1)

During the numerical simulation, the two-layer open-web sandwich plate structure retained its load-bearing capacity under the design explosion load. The primary observed damage was concrete spalling attributed to tensile stresses in the concrete. Notably, when the concrete and reinforcing bars jointly withstood the explosion load, the bending deformation of the two-layer open-web sandwich plate was effectively reduced, indicating that the structure exhibits excellent blast resistance performance.

-

(2)

Analysis of the damage response revealed that, regardless of whether the second-floor or first-floor plate was analyzed, connection points such as top ribs, bottom ribs, shear keys, and columns were more susceptible to explosion shock waves due to inadequate shear stiffness. This susceptibility led to premature cracking at these connections and localized concrete spalling.

-

(3)

Analysis of displacement and reinforcement stress responses showed that the displacement response of the two-layer open-web sandwich plate exceeded that of the single-layer plate. The study suggests that the load-bearing capacity of reinforcement can be fully utilized by appropriately increasing the reinforcement quantity in the upper flange’s upper reinforcement and the lower flange’s lower reinforcement. Additionally, strategies such as reducing the slab grid size, using high-strength reinforcement and concrete materials, installing transverse connections, and increasing shear key width can enhance the structure’s overall blast resistance, thereby improving structural safety.

-

(4)

Under near-field explosive loads, failure of open-web sandwich plate structures primarily stems from the rear blast surface being subjected to strong tensile waves. Concurrently, explosion-generated shock waves produce reflected stress waves within the hollow cavities, leading to debonding between the top and bottom concrete plates and the hollow core layer and inducing interlayer separation. Finally, when the explosive load reaches a critical threshold, the structure experiences large-scale concrete spalling, plastic bending, and collapse.

-

(5)

Under near-field explosive loads, the open-web sandwich plate structure exhibits four distinct failure modes: bending failure, shear failure, punching failure, and overall instability, which may lead to structural failure or even collapse. It is recommended that protective measures be designed based on specific engineering needs to enhance the structure’s overall blast resistance.

Data availability

The data and Abaqus files used in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Tan, Z. et al. Static load test of open-web sandwich plate floor with orthogonal-diagonal arranged steel grid. Build Struct. 49(4), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.19701/j.jzjg.2019.04.002 (2019).

Sun, T. et al. Equivalent shear stiffness analysis of steel vierendeel sandwich plate structure. Build Struct. 23(2), 54–59. https://doi.org/10.13849/j.issn.1006-6578.2017.02.054 (2017).

Wu, B. et al. Research on static and dynamic performances of steel-reinforced concrete composite open-web sandwich plate structures. Build Struct. 47(4), 81–86. https://doi.org/10.19701/j.jzjg.2017.04.017 (2017).

Fan, Y. et al. Shear-bearing capacity analysis under static force for shear key of the reinforced concrete open-web sandwich slab applied to long-span structure. Int. J. Struct. Integr. 12(2), 195–213. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijsi-11-2019-0121 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Bending theory and numerical simulation of open-web sandwich plate based on Fourier integral transform and mechanical asymptotic method. Structures. 71, 108073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.108073 (2025).

Li, D. et al. Geometric nonlinear vibration theory of the Vierendeel sandwich plate based on generalized variational method. Arch. Appl. Mech. 94(6), 1667–1689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00419-024-02605-6 (2024).

Fang, Y. et al. Experimental study of a new assembled integral concrete–steel open-web sandwich plate composite bridge. Eng. Struct. 272, 115018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.115018 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Calculation of natural frequency of reinforced concrete honeycomb-type open-web sandwich plate. Spatial Struct. 23(4), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.13849/j.issn.1006-6578.2017.04.029 (2017).

Chen, X. et al. Failure assessment method of reinforced concrete shear walls under close-in blast loads. Eng. Fail Anal. 177, 109660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2025.109660 (2025).

Peng, Z. J. et al. Self-adaptive graph neural network for predicting blast-induced damage in RC columns across multiple scenarios. Eng. Struct. 337, 120505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2025.120505 (2025).

Kong, X. et al. Numerical investigation on the dynamic behavior of thermoplastic fiber-metal laminates subject to confined explosion loading. Thin-Walled Struct. 214, 113354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2025.113354 (2025).

Yao, S. et al. Equivalent method of stiffened plates for dynamic response and damage assessment under internal blast. Structures. 76, 109046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2025.109046 (2025).

Liu, Z. et al. Experimental and numerical investigation of the dynamic response of water-covered plates subjected to gas-mixture blast loading. Thin-Walled Struct. 212, 113203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2025.113203 (2025).

Cong, P. & Li, X. Scaling global and local responses of RC structural members subjected to near-field blast loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 203, 105334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2025.105334 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. Close-range blast behavior of hybrid FRP-concrete-steel double-skin tubular member. Thin-Walled Struct. 211, 113022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2025.113022 (2025).

Wang, J. et al. Effect of high-strength rebar and ultra-high-performance concrete on blast resistance of slabs under contact explosion loads. Int. J. Impact Eng. 198, 105230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2025.105230 (2025).

Johnson, G. R. & Holmquist, T. J. An improved computational constitutive model for brittle materials. AIP Conf Proc. 309, 981. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.46199 (2008).

Oucif, C. & Mauludin, L. M. Numerical modeling of high-velocity impact applied to the reinforced concrete panel. Undergr. Space. 4(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.undsp.2018.04.007 (2019).

Xu, P. & Zuo, S. Study on the JH-2 model parameters for metro shield cutting reinforced concrete pile. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 39(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-021-01830-y (2021).

Zhao, X. H. & Wang, G. H. Damage features of RC slabs subjected to air and underwater contact explosions. Ocean Eng. 147, 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2017.11.007 (2018).

Lee, E. L. & Tarver, C. M. Phenomenological model of shock initiation in heterogeneous explosives. Phys. Fluids. 23(12), 2362. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.862940 (1980).

Dassault Systèmes. SIMULIA user assistance 2022 [software manual]. 12, (2022).

Yang, H. et al. Research on the dynamic response of open-web girders in new floor structures under near-blast load based on the CEL method. Structures. 65, 106692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2024.106692 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Study on the dynamic response of concrete open-web sandwich plate under close-range blast loading based on the CEL method. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 21, e03626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e03626 (2024).

Zhang, H.G., & Ma, K.J. Compiling and application of technical specification for reinforced concrete open-web sandwich plate structures (DB 22/48-2005). Sci. Rep. 3, (2008).

Graham, G.K.K. Explosive shocks in air [M]. (1985).

Cormie, D. & Mays, G. Blast effects on buildings [M] (Thomas Telford Publishing, London, 2009).

Li, Z. & Shi, Y. Blast analysis of building structures [M] (Science Press, New York, 2015).

Funding

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support from the Innovation Fund of Guizhou University Survey and Design [Grant No. 202206]; Science and Technology Program of Guizhou Province [Grant No.QKH2023081]; Foundation of Guizhou University [Grant No.GZUF202034].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ruison Gan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing—Original Draft; Hongxiang Yang: Data Curation, Resources, Formal Analysis; Kaicong Kuang: Resources, Supervision, Investigation; Shengyu Wu: Resources, Investigation, Supervision; Kejian Ma: Resources, Investigation, Supervision; Jing Chen (Corresponding Author): Resources, Investigation, Supervision;

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gan, R., Yang, H., Kuang, K. et al. Study on dynamic response of open web sandwich plate under near field explosive load. Sci Rep 16, 97 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28994-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28994-4