Abstract

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) poses significant therapeutic challenges due to the lack of targetable receptors and the systemic toxicity associated with conventional treatments such as surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. While phototherapy has emerged as a potential alternative, its clinical translation is hindered by the colloidal instability of photothermal agents and the need for combinatorial strategies. Here, we report the development of a near-infrared (NIR)-responsive theranostic nanoplatform based on archaeal lipid-derived nanoarchaeosomes (NA) co-encapsulating cisplatin (Cis) and PEGylated gold nanorods (AuNRs), forming a multifunctional NA-Cis-AuNRs nanoformulation. Archaeal lipids confer robust colloidal stability to this complex, enabling high drug-loading efficiency. Upon NIR irradiation, the AuNRs embedded within this complex generate localized hyperthermia, facilitating the rapid and controlled release of cisplatin. NA-Cis-AuNRs exhibit excellent biocompatibility in fibroblast cultures and zebrafish larvae, while effectively inducing apoptosis, oxidative stress, and associated DNA damage, and G2/M cell cycle arrest in TNBC cells. In vivo studies using the chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay confirm significant antiangiogenic activity, marked by downregulation of key angiogenic factors (VEGF, FGF2, and ANG1). Together, these results highlight a minimally invasive, NIR laser-triggered nanotherapeutic strategy with reduced systemic toxicity and establish a potential platform for TNBC treatment, warranting further preclinical validation in mammalian models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite significant advancements in cancer research, the global cancer burden remains staggering, with one in five individuals developing cancer in their lifetime and one in nine men or one in twelve women dying from it1. Among various types of cancers, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) stands out as one of the most aggressive types, representing 15–20% of all breast cancers and characterized by the absence of expression of estrogen receptors (ER), progesterone receptors (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). Lack of these well-defined molecular targets limits therapeutic efficacy, making TNBC particularly difficult to treat, leading to high tumor heterogeneity, increased metastatic potential, and poor prognosis2. The absence of defined therapeutic targets in TNBC contributes significantly to resistance against conventional therapies, often leading to cancer recurrence and metastasis to vital organs such as the lungs, liver, brain, and bones. This resistance is further exacerbated by cellular metabolic reprogramming and enhanced angiogenesis, which hinder effective treatment strategies3,4.

Cancer therapies have evolved dramatically over time, progressing from the earliest methods of surgery and cauterization to neoadjuvant therapies including radiotherapy and chemotherapy, followed by targeted therapies that harness immunotherapy, nanomedicine, and photodynamic therapy5,6. Although chemotherapy remains the primary treatment modality for TNBC, its efficacy is often limited by systemic toxicity, multidrug resistance, and poor tumor-targeting approaches6. These limitations have driven the pursuit of alternative therapeutic approaches that combine multimodal strategies to improve the overall therapeutic efficacy. Photothermal therapy has recently gained significant attention in cancer treatment due to its non-invasive nature and precise spatiotemporal control7. It employs a light source such as a near-infrared (NIR) laser to induce localized thermal ablation in target areas through the mechanism of localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR)7. Photothermal effects of particles such as carbon-based graphene oxides8, metal-based gold9,10, silver11, platinum12, and palladium13 are well established in alleviating repercussions associated with TNBC. Moreover, their efficiency has been improved using combinatorial approaches such as photo-chemotherapy, wherein a chemotherapeutic drug is added to the photothermal formulation12,14.

For successful multimodal cancer therapy, it is crucial to employ stable, biocompatible carriers that can simultaneously deliver chemotherapeutic drugs and other auxiliary materials, such as nanoparticles or photosensitizers. Self-assembled lipid bilayer structures, known as liposomes, are used as versatile drug delivery systems. However, conventional liposomes often suffer from poor stability and premature drug release at non-targeted sites, which can lead to undesirable side effects, toxicity, and reduced therapeutic efficacy15. Moreover, they are readily recognized as foreign by the immune system and subsequently eliminated. To overcome these limitations, next-generation stealth liposomes have also been developed16. One potential approach involves using thermostable archaeal lipids to synthesize liposomes known as “archaeosomes”17. Unlike conventional or eukaryotic lipids, archaeal lipids possess ether linkages instead of ester bonds, which confer exceptional resistance to oxidation, enzymatic degradation, and extreme pH or temperature17. This remarkable structural stability under various environmental stresses makes archaeosomes an ideal drug-delivery vehicle for cancer therapy, with minimal systemic toxicity.

In this study, we propose a synergistic photochemotherapeutic approach by irradiating near-infrared (NIR) lasers on nanoarchaeosomes (NA) loaded with cisplatin (Cis) and PEGylated gold nanorods (PEG-AuNRs) for the treatment of TNBC. Cisplatin, a potent DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic agent, is widely used in TNBC treatment; however, its non-selective cytotoxicity often limits therapeutic success18,19. Meanwhile, AuNRs are a potential photothermal therapeutic tool due to their exceptional photothermal conversion efficiency and biocompatibility20. Upon exposure to a NIR laser, AuNRs generate localized heating, which transiently disrupts the lipid bilayer of NA, facilitating the release of encapsulated drugs21. The extent of drug release can be modulated by tuning the laser parameters such as intensity, exposure time, and power density. Unlike conventional liposomal or hybrid nanocarriers, archaeal lipid–derived NA possess ether-linked backbones that confer remarkable resistance to degradation, oxidation, and extreme pH or temperature variations, ensuring exceptional stability under physiological stress17,22. In addition to durability, NA provides rapid, NIR-triggered on-demand cisplatin release (70% in 5 min) and prevents premature leakage, offering spatial and temporal control. Their inherent biocompatibility, negative surface charge, and PEGylation minimize immune clearance. Furthermore, the dual encapsulation of cisplatin and PEG-AuNRs produces synergistic chemo-photothermal and anti-angiogenic effects at nanomolar concentrations. The applied NIR irradiation parameters (808 nm, 0.5 W cm2, 5 min) fall within clinically acceptable limits, highlighting the translational potential of archaeal lipid–based nanocarriers for advanced TNBC therapy. By integrating cisplatin and AuNRs into novel NA and activating them with NIR laser irradiation, we aim to achieve synergistic chemo-photothermal therapy through controlled drug release and improved therapeutic efficacy. This formulation exhibited cytotoxicity in TNBC cells while showing minimal toxicity towards normal cells and in zebrafish models. Mechanistic studies confirmed cell cycle arrest, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and reduced angiogenesis. This multifunctional strategy offers a potential approach to enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic toxicity through synergistic chemo-photothermal therapy. A schematic illustration of the nanoarchaeosome (NA-Cis-AuNRs) design and its NIR-triggered photochemotherapeutic mechanism is shown in Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the design and mechanism of NIR-triggered photochemotherapy using archaeal lipid–based nanoarchaeosomes (NA-Cis-AuNRs). The Fig. compares conventional liposomes and archaeal nanoarchaeosomes, highlighting the enhanced ether-linked membrane stability of archaeal lipids that confer superior colloidal, thermal, and pH stability. Upon 808 nm NIR irradiation, PEGylated gold nanorods within the NA-Cis-AuNRs generate localized hyperthermia, triggering rapid cisplatin release and inducing oxidative stress–mediated apoptosis and inhibition of angiogenesis in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells.

Materials and methods

Materials

Chemicals such as SOPC (1-stearoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), archaeal lipids, MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide), propidium iodide, and ethidium bromide (EtBr) were procured from Sigma-Aldrich (Bangalore, India). Acridine orange (AO) was purchased from Nalgen (Kolkata, India). Phalloidin and 2′-7′ dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetates (DCFDA) were obtained from Invitrogen (Bangalore, India) and Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Annexin-V APC was obtained from BioLegend (San Diego, USA). Other chemicals, such as methanol, ethanol, isopropanol, and chloroform, were procured from Sisco Research Laboratories (Mumbai, India).

Synthesis and characterization of nanoarchaeosomes (NA)

Nanoarchaeosomes (NA) were synthesized following a previously established protocol with slight modifications17. Briefly, 1-stearoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (SOPC) and archaeal lipids were mixed in a molar ratio of 97:3 in chloroform to reach a final concentration of 1 mg/mL and then subjected to vacuum drying to form a thin lipid film. Later, this film was reconstituted with Milli-Q water and vortexed for 5 min to facilitate the formation of multilamellar vesicles (MLVs). The MLVs were then sonicated at 45 °C for 30 min using an ultrasonic bath sonicator (B.R. Biochem Life Sciences, Mumbai, India) to form small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs). Then, the sample mixture was centrifuged (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5415C) at 13,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C to separate the SUVs from debris. Dynamic light scattering (Horiba Scientific DLS) was performed to characterize the hydrodynamic diameter of NA by diluting the sample in a 1:100 ratio. Morphological analysis was performed using a scanning electron microscope (Apreo 2 SEM, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). For SEM analysis, NA were drop-cast onto a clean glass slide, and air-dried at room temperature, followed by gold sputter coating at 2.5 kV and 20 mA with a deposition rate of 10 nm per minute (Polaron/Quorum Technologies, UK). Images were acquired at an operating voltage of 1–5 kV.

Characterization of PEG-AuNRs

The morphological characteristics of PEG-AuNRs (NanoComposix Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) were examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (model JEM-1010, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) operated at an accelerating voltage of 200 kV. Their size distribution and zeta potential (surface charge) were analyzed using a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK) at a wavelength of 633 nm, a 173° scattering angle, and a temperature of 25 °C. Ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectrophotometry was performed with a Specord 210 Plus spectrophotometer (Edition 2010, Analytik Jena AG, Thuringia, Germany).

Synthesis and characterization of NA-Cis-AuNRs complex

NA-Cis-AuNRs complexes were prepared to achieve a final composition of 1% (v/v) PEG-AuNRs and 100 μM cisplatin in a 1 mg/mL NA solution. Briefly, the NA precursor was prepared by dissolving SOPC and archaeal lipids in a ratio of 97:3 (v/v) in chloroform. After vacuum drying, 1 mg of the lipid film was rehydrated in a 1:1 volume ratio using an aqueous solution containing 2% PEG-AuNRs and 200 μM cisplatin (prepared in sterile Milli-Q water). The resulting suspension was vortexed for 5 min and then sonicated for 45 min to facilitate initial incorporation. To enhance drug loading, the mixture was incubated overnight in a thermal shaker at 37 °C and 300 rpm. This was followed by five cycles of freeze–thaw, alternating between a 45 °C water bath and a − 196 °C liquid nitrogen bath for 1 min each, to get the final NA-Cis-AuNRs formulation.

Thermal stability, drug release, and response of NA-Cis-AuNRs complex after laser irradiation

Once the NA-Cis-AuNRs complexes were synthesized, their thermal stability and response to NIR irradiation were analyzed. A near-infrared laser (Dongguan Blueuniverse Laser Co., Ltd., Dongguan, China) with a power density of 0.5 W/cm2 was used in this study. To track thermal changes post-irradiation, the loaded NA, placed in a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube, was initially irradiated with the NIR device for 5 min at a vertical distance of 5 cm from the sample. The irradiation caused heating of the samples, which was recorded using a thermal camera (HIKMICRO, Hangzhou, China) that measured the temperature rise at different time intervals. Images were analyzed using HIKMICRO Viewer software from the same manufacturer. For irradiation experiments, the platforms, such as cell cultures, larvae, or developing chick embryos, were exposed to the centered laser spot from the NIR device for 5 min at a vertical distance of 5 cm from the bottom, following the addition of treatment components.

For studying the drug release profile, the dialysis membrane method was followed23. The NA loaded with AuNRs and cisplatin was filled in a dialysis membrane having a 12 kDa -14 kDa molecular cutoff and allowed to sink in a screw cap bottle filled with phosphate buffer saline of pH 7.4 under constant stirring at 300 rpm and 37 °C. For the NIR irradiated sample, the NA-Cis-AuNRs solution was irradiated for 5 min, and then the solution was immediately loaded onto the dialysis bag. Samples were taken at predetermined time points (0, 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 120, 200, 300, 400, and 500 min) and evaluated for their concentration using HPLC. The drug release percentage was calculated using the formula22:

In vitro cell culture for cell viability and toxicity

The embryonic mouse fibroblast cell line NIH 3T3 and human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 cells used in this study were obtained from NCCS (National Centre for Cell Science, Pune, India). The cells were routinely maintained in a Forma Steri-Cycle CO2 Incubator (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 5% CO2 and 37 °C in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium Gibco (Grand Island, NY, USA) along with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin solution containing 10,000 units of penicillin and 10 mg of streptomycin dissolved in 0.9% sodium chloride (Himedia, Mumbai, India).

The Dimethyl thiazolyl diphenyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay, which detects mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity, was employed to evaluate biocompatibility and cytotoxicity in mammalian cells. NIH 3T3 cells were used for biocompatibility, while MDA-MB-231 cells were used for cytotoxicity. Briefly, NIH 3T3 and MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded at a density of 104 cells per well in a 96-well tissue culture plate and allowed to attach overnight. Once confluent, the cells were treated with increasing concentrations (0 to 1000 nM) of the NA and NA-Cis-AuNRs complex with or without the NIR irradiation and further incubated for 24 h. Later, the media was changed and 20 µL of MTT (5 mg/mL) was added to each well and made up with normal media, and incubated for 4 h in the dark at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After incubation, 100 µL of DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan crystals formed, and the absorbance was recorded at 570 nm using a BioTek Synergy H1 Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). Cell viability was expressed as a percentage relative to the untreated control, which was set at 100%.

DCFH-DA assay for intracellular ROS level determination

Briefly, MDA-MB-231 cells were seeded in 30 mm dishes. Upon reaching confluence, they were treated with the NA-Cis-AuNRs formulation followed by 5 min of NIR irradiation. After 24 h of incubation, the cells were washed once with 1X PBS and incubated with 20 μM 2’,7'-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH DA) working solution for 30 min in the dark at 37 °C. Following incubation, the cells were washed twice with 1X PBS, and then Images were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse Ti-U Inverted Microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Tokyo, Japan) at an emission wavelength of 530 nm. Fluorescence intensity was quantified using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Acridine orange/ethidium bromide staining for morphological evaluation and apoptosis

After 24 h, the confluent cells were washed twice with sterile PBS and stained with a freshly prepared AO/EtBr solution (100 µg/mL each in PBS) for 5 min at room temperature in the dark. The stained cells were immediately visualized under a fluorescence microscope (excitation: ~ 480 nm, emission: ~ 530–590 nm). At least five random fields per sample were imaged to assess morphological changes.

Cell cycle analysis using flow cytometry

To analyze the population distribution of cells across different cell cycle stages post-treatment, cell cycle analysis was performed using a BD FACS Canto™ II flow cytometer equipped with BD FACSDiva™ software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Briefly, cells treated with 150 nM of NA-Cis-AuNRs were irradiated with an NIR laser and incubated for 24 h. Later, the cells were washed once with ice-cold PBS, trypsinized, and collected. The cell pellet was directly fixed with 70% ice-cold ethanol and stored at -20 °C overnight or until analysis. Then, the cells were washed with 1 × PBS by centrifuging and treated with ribonuclease A (RNAse A) (10 μg/mL) for 20 mins at room temperature. Finally, the cells were stained with propidium iodide (15 μg/mL) and in 0.1% Triton X buffer in PBS at 4 °C for 15–20 min before acquisition on the flow cytometer.

Immunocytochemical analysis of 8-Hydroxy-2-Deoxyguanosine

To analyze the extent of oxidative damage on DNA post-treatment with NA-Cis-AuNRs, we looked into the expression of 8-Hydroxy-2-Deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) in MDA-MB231 cells. Cells were seeded on coverslips for the experiment. After 24 h of treatment, they were washed with sterile PBS and fixed in 100% ice-cold methanol initially and then in 4% Paraformaldehyde. The cells were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X 100 and incubated with 25 ng/mL of RNase. This was further followed by DNA denaturation and neutralization, and washing with 1 X PBS with 0.1% tween 20 (PBST). The cells were then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin and washed. The cells were incubated with a 1:200 dilution of rabbit 8-OHdG primary antibody (Genetex, GTX35250, USA) overnight at 4°Celsius. The next day, the cells were washed with 1 X PBST and incubated in a 1:500 dilution of mouse anti-rabbit IgG-FITC (sc-2359, Santa Cruz Biotech, USA) for 1 h in the dark, then washed. The nuclei were finally counterstained with Hoechst stain (1 μg/mL, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) for 10 min and washed. The images were then captured using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP8).

Zebrafish maintenance, breeding, and viability study

All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC) of Saveetha University, Chennai, India (Approval No: BRULAC/SDCH/SIMATS/IAEC /03/2024/03). Zebrafish were maintained in a dedicated facility with a recirculating water system equipped with automated purification, filtration, and continuous aeration. Environmental parameters, such as temperature (28 °C) and pH (5–8), were carefully maintained throughout this study. Fish were fed a dry diet, and breeding was performed under controlled conditions as required for experimentation. To initiate breeding, male and female zebrafish were placed in a small tank separated by a glass divider and a mesh bottom overnight. The divider was removed the following morning to allow for natural breeding. Fertilized embryos that settled at the bottom of the tank were carefully collected using a pipette and transferred to separate containers for further maintenance and larval formation. The biocompatibility of the synthesized NA, AuNRs, and NA-Cis-AuNRs complex was analyzed in zebrafish larvae based on viability. A total of 30 embryos were assigned to each group. The larvae were exposed to various conditions in water for 24, 48, and 72 h, and water was replaced every 24 h with the respective treatment component, followed by NIR exposure. Viability was further analyzed by counting the number of live larvae.

CAM Assay for angiogenesis inhibition in chicken eggs

Fertilized eggs from brown leghorn chickens were received from the Government Poultry Station (Potheri, Chennai, India) and incubated at 37 °C for 4 days prior to experimentation. A small opening was created on top of the eggshell to facilitate entry of the treatment components. For the positive tumor control, MDA-MB-231 cells seeded onto sterile glass slides were cultured until confluent, and then transferred onto the egg yolk. For simulating treatment, sterile filter paper discs soaked in different concentrations of treatment components, such as NA alone or NA-Cis-AuNRs complex, were placed on egg yolks and incubated up to 6 h. Sterile PBS served as the negative control. Images of Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane (CAM) with the developing blood vessels were acquired using a stereomicroscope equipped with a Magnus camera (Mag Cam, New Delhi, India) at different time intervals of 0, 3, and 6 h. Image analysis was performed using IKOSA CAM software (KML Vision GmbH, Graz, Austria; https://www.kmlvision.com/our-offerings/ikosa-prisma/). Additionally, small areas of the CAM were excised for mRNA expression analysis.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from each excised segment of CAM using the TRIzol reagent method24. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized using a Reverse Transcriptase (RT) kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions from Invitrogen (Cananda, USA). Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed using the KAPA SYBR qPCR kit (Kapa Biosystems, MA, USA) on an Eppendorf Realplex 4 Mastercycler system (Eppendorf North America, Inc., Enfield, CT, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Table 1 shows the list of primers used for RT-PCR analysis. β-actin was used as an internal control for normalization of expression. The thermal cycling steps included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. Relative gene expression was calculated using the ΔΔCt method as previously described24.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3), and the data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Zebrafish and CAM assays were carried out using three independent biological replicates, each comprising 10 embryos and 3 eggs per treatment group. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

Characterization of the NA-Cis-AuNRs complex

Nanoarchaeosomes (NA) and cisplatin–gold nanorods-loaded nanoarchaeosomes (NA-Cis-AuNRs) were prepared by mixing SOPC and archaeal lipids in a 97:3 (w/w) ratio, followed by the thin-film hydration method as described in the Experimental section. The morphology, hydrodynamic diameter distribution, and structural integrity of pure NA, and NA-Cis-AuNRs complex were characterized using SEM, DLS, and FTIR, respectively (Fig. 2). SEM images (Fig. 2a) revealed that pure NA appears as well-dispersed spherical vesicles with relatively uniform morphology. Size analysis from SEM indicated that the mean diameter of NA was approximately 62 ± 9 nm, which was in good agreement with DLS measurements (Fig. 2b), showing a hydrodynamic size of 67 ± 8 nm. This result is consistent with the size of pure NA synthesized using the same procedure in previous studies17. TEM image and UV–vis absorption spectra of PEG-AuNRs are shown in Figures S1a and S1b, respectively. Similar to that of pure NA, SEM images of NA-Cis-AuNRs also showed a spherical morphology (Fig. 2c), suggesting that co-encapsulation of cisplatin and AuNRs did not significantly alter the vesicle shape. No major aggregation was observed, with a particle mean size of 200 ± 6 nm indicating their excellent colloidal stability.

Characterization of nanoarchaeosome formulations confirming morphology, size, and molecular interactions. SEM images and DLS analysis of NA (a, b) and NA-Cis-AuNRs (c, d) showing the corresponding size distribution histograms. Scale bar corresponds to 1 μM. (e) FTIR spectrum of PEG-AuNRs, cisplatin, NA, NA-AuNRs, and the loaded complex.

DLS analysis of NA-Cis-AuNRs (Fig. 2d) shows a considerable increase in their hydrodynamic size to approximately 213 ± 4 nm. This size increase corroborates the effective encapsulation of both cisplatin and AuNRs within the developed nanoformulation. Such size augmentation upon co-loading of metallic nanostructures and drugs has been previously reported in lipid-based nanocarriers25,26. For example, Taylor et al.27 observed a similar size expansion in liposomes loaded with both gold nanoparticles and chemotherapeutic agents, due to surface association and steric interactions between the encapsulated components and the lipid bilayer. The increase in size remains within the optimal range for tumor accumulation via the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, supporting the suitability of NA-Cis-AuNRs for in vivo applications28,29.

Zeta potential measurement confirmed colloidal stability, with NA showing a surface charge of − 55 ± 3 mV, while the NA-Cis-AuNRs formulation exhibited a slightly more negative value of − 58.3 ± 3 mV, suggesting enhanced colloidal stability. The increase in negative surface charge is likely due to the presence of PEGylated AuNRs and the binding of cisplatin to the lipid head groups, which may expose more negatively charged areas30,31. Additionally, the PEG chains on AuNRs help prevent particle aggregation, improving suspension stability. A zeta potential value exceeding ± 30 mV generally indicates strong electrostatic repulsion, which reduces the possibility of particle aggregation and is considered pharmaceutically stable32,33.

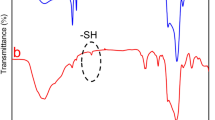

Furthermore, HPLC analysis revealed a cisplatin (100 µM) encapsulation efficiency of 97 ± 3%. This high encapsulation efficiency is consistent with previous results, which demonstrate the superior drug loading capability of NAs, particularly when employing the freeze–thaw method, which induces pore formation on vesicle surfaces through the formation of ice crystals34. Next, FTIR analysis was performed to confirm the interaction of cisplatin and AuNRs within the NA matrix by identifying characteristic functional groups and any spectral shifts indicating molecular interactions. Figure 2e shows FTIR spectra of the individual components (PEG-AuNRs, cisplatin, and NA) and their combinations. The FTIR spectrum of PEG-AuNRs revealed characteristic peaks at 3397 cm−1 (O–H stretching, alcohol), 2923 cm−1 (C–H stretching, alkane), and 2853 cm−1 (C–H stretching, alkane). Additional peaks were observed at 1636 cm−1 (C=O stretching, oxidized carboxylate), and 1061 cm−1 (C–O–C stretching, ether linkage)35. These peaks are consistent with the structural features of PEG, confirming successful PEGylation of the AuNRs, wherein the O–H groups provide hydrophilicity and potential sites for further functionalization. The C–H stretches indicate the methylene backbone of PEG, the C=O peak suggests the presence of oxidized or carboxyl-modified PEG useful for conjugation, and the C–O–C ether stretch confirms the integrity of the PEG chain essential for enhancing biocompatibility, colloidal stability, and reduced immunogenicity of AuNRs. The FTIR bands of cisplatin exhibited notable peaks at 3284 cm−1 (amine N–H stretching), 2920 cm−1 (amine bending), 1625 cm−1 (Pt–N vibration), 1536 cm−1 (C=O stretching), 1299 cm−1 (symmetric amine bending), and 797 cm−1 (C–Cl in-phase stretching), These characteristic peaks of cisplatin are previously reported36. The FTIR spectrum of NA displayed characteristic peaks at 2920 cm−1 (C–H stretch), 1740 cm−1 (ester bond linkage), 1464 cm−1 (C=O stretching), and 1378 cm−1 (PO2− antisymmetric stretching), which are consistent with previous reports17.

The FTIR spectrum of NA-AuNRs exhibited typical peaks at 2956 cm−1, 2920 cm−1, and 2850 cm−1 corresponding to asymmetric and symmetric C–H stretching vibrations of lipid alkyl chains. A characteristic peak at 1737 cm−1 is due to ester C=O stretching, confirming the structural integrity of the lipid22. Additional peaks at 1468 cm−1 and 1382 cm−1 are due to C=O stretching and PO2− antisymmetric stretching, respectively. The appearance of a new peak at 1237 cm−1 indicates potential interactions between AuNRs and the phosphate groups of lipids37. FTIR spectrum of NA-Cis-AuNRs showed typical shifts and new peaks that reflect the molecular interactions of cisplatin. The main peaks were seen at 1735 cm−1 (C=O stretching), 1627 cm−1 (amide bending mode), and 1460 cm−1 (C–H bending). The emergence of new peaks at 1298 cm−1 and 1092 cm−1 also strongly supports the interaction between cisplatin and NA-AuNRs. Also, the peaks at 971 cm−1 and 799 cm−1 are assigned to the Pt–N and C–Cl stretching modes of cisplatin, verifying its successful encapsulation into the nanoformulation. The peak shifts reflecting the changes in characteristic functional groups, especially phosphate and amide regions, implicate the potential molecular interactions of both AuNRs and cisplatin within NA, confirming successful co-encapsulation without compromising vesicle integrity.

Photothermal behavior and NIR-triggered drug release kinetics

To evaluate the photothermal response of the NA-AuNRs complex, the temperature elevation under 808 nm NIR continuous wave laser irradiation (0.5 W/cm2) was measured over time. As represented in Fig. 3a, NA-AuNRs showed a linear temperature increase, reaching approximately 46 ± 4 °C within 5 min of NIR exposure. This temperature is sufficient to induce membrane permeability changes in lipid-based vesicles, facilitating drug release while remaining within the safe hyperthermia range to avoid thermal damage to surrounding healthy tissues38. Thermal images in Figures S2a and S2b further confirm this effect, showing baseline temperature at 0 min and significant heating after 5 min of NIR exposure, thus validating the localized photothermal heating capability of NA-Cis-AuNRs. To evaluate whether this photothermal effect could facilitate drug release, the release profile of cisplatin from NA-Cis-AuNRs with and without NIR exposure was monitored using HPLC.

As illustrated in Fig. 3b, a sharp burst release (~ 70%) of cisplatin occurred within the first 5 min of NIR irradiation, demonstrating rapid and efficient drug release in response to localized heating. The drug release increased further, approximately to 95% by 15 min, and complete release (100%) by 30 min, which remained constant up to 500 min, confirming the potential of NIR-induced hyperthermia to enable controlled and sustained drug delivery.

In contrast, the NA-Cis-AuNRs complex without NIR laser exposure did not exhibit any burst release. It showed only a gradual and limited drug release (~ 20%) over the same duration (500 min). These results confirm that encapsulation of cisplatin in NA provides excellent stability, enhances drug retention time, and improves its bioavailability. Moreover, NIR laser-induced controlled drug release from NA helps to minimize systemic toxicity and decrease adverse side effects. Similarly, a previous study with doxorubicin-loaded NA demonstrated sustained drug release potential at a controlled rate, even under acidic pH conditions that mimic the tumor microenvironment17. These findings support the potential of NA as a robust drug delivery platform. Additionally, the incorporation of AuNRs into NA facilitates localized temperature increase and sustained release of cisplatin.

Notably, the NIR exposure parameters used in this study can be feasibly translated to in vivo or clinical applications with appropriate adaptation for patient treatment. At 808 nm and 0.5 W/cm2 for 5 min, the achieved temperature rise (≈46 °C) lies within the mild hyperthermia range, sufficient to trigger drug release while minimizing risk to surrounding tissues39,40. Given that 808 nm light can penetrate up to ~ 1 cm in soft tissue, these parameters are suitable for superficial or subcutaneous tumors41,42, while deeper targets could be treated using interstitial fiber-optic delivery to bypass surface attenuation43. Comparable irradiance levels have been clinically applied with real-time thermal monitoring and epidermal cooling to ensure safety44,45. The rapid, NIR-triggered cisplatin release demonstrated here supports the feasibility of on-demand, localized drug activation under clinically manageable conditions, underscoring the translational promise of NA-Cis-AuNRs for synergistic photochemotherapy.

Compared to previously reported cisplatin-loaded nanocarriers (Table 246,47,48,49,50,51), the NA-Cis-AuNRs offers a distinctive combination of rapid, NIR-triggered release (~ 70% in 5 min; ~ 95% in 15 min) with minimal passive leakage, enabling precise spatiotemporal control and reduced systemic toxicity. The initial burst within the first 5 min corresponds to the NIR-induced phase transition of the archaeal lipid bilayer, leading to rapid release of surface-associated cisplatin. Beyond this point, the release profile plateaued, indicating stable retention of the core-entrapped fraction and confirming that the system enables on-demand, laser-triggered release rather than uncontrolled diffusion52,53. In contrast, established carriers such as stealth liposomes (SPI-77) or polymeric micelles (NC-6004) rely primarily on slow, diffusion-driven release and enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effects, which may limit immediate intratumoral drug availability. Moreover, unlike pH-responsive or magnetically triggered formulations, the NA-Cis-AuNRs employ a clinically relevant, non-invasive NIR trigger with demonstrated tissue penetration, while simultaneously integrating photothermal and chemotherapeutic modalities in a biocompatible lipid matrix. This multimodal and controllable delivery strategy holds clear potential for improving therapeutic outcomes in solid tumor treatment.

Biocompatibility of NA-Cis-AuNRs in mouse fibroblasts and zebrafish model

The biocompatibility of our formulation was evaluated using the MTT assay on NIH-3T3 mouse fibroblast cells and zebrafish larvae as in vitro and in vivo models, respectively. Figure 4a illustrates the cell viability percentage of NIH-3T3 cells following 24 h of treatment with various controls and our formulation. The cells treated with NA or NIR alone showed negligible cytotoxicity, maintaining > 95% viability compared to the control group. The T-test with p > 0.05 showed no significant difference between the control, NA, NIR, or NA-Cis-AuNRs treated cells. This result is consistent with previous studies, where NA alone did not show any cytotoxic effect on NIH-3T3 cells17,22. No observable reduction in viability by NIR laser at a power density of 0.5 W/cm2 for 5 min indicates that the applied irradiation parameters were biologically safe under the experimental conditions. A previous report has indicated that low-intensity lasers do not exert significant deleterious biological effects54. Nevertheless, it is shown to increase ATP levels at biologically safe ranges at prolonged exposure to similar lasers55. Although the applied intensity in this study was relatively high (0.5 W/cm2), the short exposure duration (5 min) and the use of an 808 nm NIR laser wavelength, which permits deeper tissue penetration with reduced absorption by endogenous chromophores, contributed significantly to the observed safety.

Evaluation of biocompatibility of NA-Cis-AuNRs in fibroblast cells and zebrafish models, confirming the non-toxic nature of the carrier system. (a) MTT assay depicting cell viability of NIH-3T3 fibroblasts after 24 h of treatment with various components. (b) Microscopic images of NIH-3T3 cells after 24 h of treatment. (i) Control, (ii) NA, (iii) Cisplatin, (iv) NIR alone, (v) NA-Cis-AuNRs, (vi) NA-Cis-AuNRs after NIR irradiation. Scalebar corresponds to 100 μM (c) Larval biocompatibility of zebrafish larvae post 24-, 48-, and 72-h treatment with various components. (d) Microscopic images of zebrafish larvae after 72 h of treatment. (i) Control, (ii) NA, (iii) Cisplatin, (iv) NIR alone, (v) NA-Cis-AuNRs, (vi) NA-Cis-AuNRs after NIR irradiation. The scale bar corresponds to 1000 μm.

Similarly, the cells treated with NA-Cis-AuNRs also did not show any notable difference in viability, confirming the carrier’s excellent stability. This suggests that encapsulation within NA effectively reduces off-target drug release, thereby limiting nonspecific damage to healthy fibroblasts. Additionally, previous studies have reported that PEG-AuNRs demonstrate excellent biocompatibility, low inherent cytotoxicity, and efficient cellular internalization in various fibroblast cell types, further supporting the safety profile of the formulation56,57,58.

On the other hand, cells treated with free cisplatin (100 nM) showed a reduction in viability to approximately 93%. This indicates low cytotoxicity of cisplatin at this concentration in normal cells and is consistent with literature reports59,60. For instance, Mirmalek et al.61 demonstrated minimal cytotoxicity (> 90% viability) in NIH-3T3 cells treated with 100 nM cisplatin, whereas the same concentration reduced viability in cancer cells such as MCF-7 and HeLa to below 50%. These findings are further supported by earlier reports showing that the IC₅₀ of cisplatin in mouse fibroblasts exceeds ~ 100 μM, whereas in human fibroblasts during logarithmic growth, it is approximately 15 μM62. Taken together, these data support the use of 100 nM cisplatin as a biocompatible dose in normal cells while retaining therapeutic relevance in cancer models. Interestingly, upon NIR exposure, cells treated with NA-Cis-AuNRs showed only a slight reduction in viability (~ 95%). This indicates that the combined thermal and chemotherapeutic effects were insufficient to induce significant toxicity in fibroblasts with nanomolar-range cisplatin. Notably, free cisplatin (100 nM) caused comparatively greater cytotoxicity primarily due to non-specific uptake and lack of targeting.

These findings are visually corroborated by microscopic imaging (Fig. 4b i–vi). The results showed healthy cells with intact cell membrane and cytoplasm with prominent nucleoli for control, NA, NIR, and NA-Cis-AuNRs-treated samples. These results are consistent with previous work demonstrating the biocompatibility of NA loaded with anti-cancer drug doxorubicin and flavonoid quercetin in NIH-3T3 cells17,22.

Since cell culture models are primitive and not suitable to replicate the systemic effects or whole-organism toxicities, we used zebrafish larvae to compare the biocompatibility of NA-Cis-AuNRs. Due to their genetic similarity to humans and transparency during early vertebrate development, they are well-established models for biocompatibility studies63. Similar to the results obtained with fibroblasts, larvae exposed to control, NA, or NIR only treatments maintained high viability (~ 97 ± 3%) up to 72 h (Fig. 4c), confirming the biocompatibility of NA and the safety of laser parameters. Notably, NA-Cis-AuNRs with NIR treated larvae also maintained high viability at early time points (24 and 48 h), with a slight decline by 72 h, probably due to delayed-onset toxicity. However, free cisplatin significantly reduced larval viability to 91 ± 3% at 72 h, consistent with previously reported ototoxic and pro-inflammatory effects in zebrafish embryos64,65.

These observations were further supported by the microscopic images of zebrafish larvae with different treatment groups after 72 h (Fig. 4d). Larvae in the control (i), NA (ii), and NIR alone (iii) groups appeared morphologically normal, with clear body structure and no signs of edema or deformities, indicating good biocompatibility. Even though constant exposure to low-power infrared light has been shown to induce negative phototaxis in zebrafish larvae, no toxicity has been reported66. In contrast, larvae treated with free Cisplatin or NA-Cis-AuNRs + NIR exhibited clear signs of developmental abnormalities, including pericardial edema, body curvature, and reduced motility (Fig. 4diii and vi). Our results showed that even 150 nM of Cisplatin led to a reduction in larval viability to 91 ± 3.8% at 72 h, consistent with previously reported ototoxic and pro-inflammatory effects in zebrafish embryos67,68. Notably, larvae exposed to NA-Cis-AuNRs and NIR irradiation maintained high viability (95.56 ± 3.85%) up to 48 h, suggesting extreme stability and biocompatibility of NA. The group exposed to 72 h of NIR irradiation follows a similar trend of free Cisplatin but showed a slight reduction in viability (93 ± 0.5%), (91 ± 3.9%), probably due to delayed-onset toxicity. Overall, these results assure the safety of our nanoformulation, while also demonstrating its therapeutic impact under NIR activation.

Cytotoxicity of NA-Cis-AuNRs to TNBC cell lines

To evaluate the cytotoxic potential of NA-Cis-AuNRs against TNBC cells, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with increasing concentrations (0 to 1000 nM) of free cisplatin, NA-Cis-AuNRs (with and without NIR), and NIR irradiation alone. As shown in Fig. 5a, cells treated with NIR alone or free cisplatin exhibited negligible cytotoxicity, maintaining high viability (~ 100 ± 4.8%) across all tested concentrations, confirming that the applied laser intensity (0.5 W/cm2) is biologically safe and that cisplatin alone shows limited potency against this resistant cell line. Previous studies have reported the IC50 of cisplatin to be approximately 15 to 25 μM in claudin-low MDA-MB-231 cells, while it exceeds 200 μM in parental MDA-MB-231 cells after 24 h of treatment69,70.

Cytotoxicity and therapeutic efficacy of NA-Cis-AuNRs demonstrating enhanced photo-chemotherapeutic effects against MDA-MB-231 cells. (a) MTT assay depicting cell viability of MDA MB231 cells post-treatment with NIR, Cisplatin, NA-Cis-AuNRs with and without NIR. (b) Microscopic images of MDA-MB-231 cells after 24 h of treatment. (i) Control, (ii) NA-Cis-AuNRs with NIR. Scalebar corresponds to 100 μM.

In contrast, NA-Cis-AuNRs alone exhibited a dose-dependent reduction in viability, indicating partial release or uptake of cisplatin from the nanocarrier. Cell viability remained above 95% up to 100 nM but declined progressively at higher concentrations: 87 ± 3% at 150 nM, 76 ± 3.8% at 200 nM, 50 ± 2.6% at 400 nM, and 22 ± 2.6% at 1000 nM. Notably, the combination of NA-Cis-AuNRs + NIR treatment led to a dramatic reduction in cell viability, with a significant drop even at 100 nM and complete cytotoxicity at higher concentrations, confirming the synergistic effect of localized photothermal heating and triggered drug release. This enhanced efficacy may be attributed to thermally enhanced cellular uptake and accelerated endosomal escape of the nanocarrier under NIR irradiation, leading to efficient intracellular release of cisplatin. These findings are further supported by the microscopic images of MDA-MB-231 cells after 24 h of treatment (Fig. 5b). The control group (Fig. 5b(i)) showed confluent cells with normal morphology, whereas cells treated with NA-Cis-AuNRs + NIR (Fig. 5b(ii)) displayed clear signs of cell shrinkage, rounding, and detachment, indicative of cytotoxic stress and apoptosis. These effects are consistent with those observed for several organic photothermal agents in cancer therapy71. Collectively, these findings underscore the advantage of the NA-Cis-AuNRs nanoplatform in delivering cisplatin selectively under external NIR stimulus, thereby overcoming the limitations of conventional cisplatin therapy in TNBC.

NA-Cis-AuNRs induce oxidative stress and promote apoptosis

To further elucidate the cytotoxic mechanisms of NA-Cis-AuNRs on other cellular responses, a series of in vitro assays was performed to evaluate morphological changes, ROS generation, and cell death in MDA-MB-231 cells, as shown in Fig. 6. Oxidative stress was assessed in MDA-MB-231 cells using the DCFH-DA assay, which is a widely used fluorescence-based assay for detecting the reactive oxygen species (ROS) content in cells. DCFH-DA is a non-fluorescent, cell-permeable dye that can enter cells. It is oxidized by ROS inside the cells to form DCF (2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein), which is a fluorescent compound72. The fluorescence intensity of DCF correlates with the intracellular ROS levels and can be detected using fluorescence microscopy.

ROS generation and apoptosis analysis revealing synergistic photo-chemotherapeutic effects of NA-Cis-AuNRs. (a) Brightfield images of MDA-MB231 cells after 24 h. (i) Control, (ii) NA-Cis-AuNRs with NIR. (b) Fluorescence microscopic images (i) Control, (ii) NA-Cis-AuNRs with NIR. (c) Graph showing the fluorescence intensity of intracellular ROS. *** Implies the level of significance difference at p < 0.001 as compared to the control. Scalebar corresponds to 200 μM. (d) Acridine Orange/Ethidium Bromide dual staining. i- Control, ii- Cisplatin, iii- NA-Cis-AuNRs, iv- NA-Cis-AuNRs with NIR. (e) Graph showing the fluorescence intensity of AO and EtBr. * Implies significance level at P < 0.05 as compared to control, Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3); significance levels: ** implies P < 0.01, **** implies P < 0.0001. Scalebar corresponds to 100 μM.

Figure 6a(i) shows the bright-field image of untreated MDA-MB231 cells with normal morphology and adherence, whereas Fig. 6a(ii) displays cells treated with NA-Cis-AuNRs + NIR, revealing visible morphological changes such as cell shrinkage and rounding, indicative of treatment-induced stress or apoptosis. High concentrations of AuNRs have been reported to impair antioxidant enzyme activity in bladder cancer cells, thereby increasing oxidative stress73. Cisplatin, a DNA-binding chemotherapeutic drug, is well-known for its ability to induce ROS production and oxidative stress, contributing to apoptosis in various types of cancer74. In contrast, control cells retained normal morphology. Fluorescence microscopic images (Fig. 6b(i)), showed minimal green fluorescence in control cells, indicating low basal levels of intracellular ROS. In contrast, Fig. 6b(ii) shows a marked increase in fluorescence upon NA-Cis-AuNRs + NIR treatment, indicating elevated intracellular ROS generation as a result of the combined photothermal and chemotherapeutic effect.

As shown in Fig. 6c, the control cells displayed minimal signals, with an average fluorescence intensity of ~ 4.9 a.u., whereas the treated cells showed a dramatic fivefold increase, reaching fluorescence intensities of ~ 26 a.u., indicating photothermal activation and substantial oxidative damage induced by NA-Cis-AuNRs. Notably, redox imbalance in the cells is a key factor for the development of cisplatin chemoresistance75. The minimal concentrations of cisplatin and AuNRs used in this study are unlikely to induce such strong oxidative damage independently. Their co-encapsulation in NA and subsequent activation via NIR irradiation facilitates controlled drug release and efficient intracellular delivery. Consequently, this approach improves therapeutic efficacy while reducing systemic toxicity and resistance development.

Elevated ROS levels in cells are known to induce various cell death mechanisms, such as apoptosis and ferroptosis, in cancer cells treated with cisplatin76. To further assess the mechanism of cell death induced by NA-Cis-AuNRs, AO/EtBr dual staining was employed (Fig. 6d). This is a well-established method for assessing membrane integrity and nuclear morphology to distinguish between viable, apoptotic, and necrotic cells77. AO permeates all cells and stains nucleic acids green, indicating viable or early apoptotic cells with intact membranes78. In contrast, EtBr intercalates into the DNA of cells with compromised membranes, staining DNA red and marking late apoptosis or necrosis79.

As shown in Fig. 6d–i, control cells exhibited strong green fluorescence, denoting the highest viability and normal nuclear morphology. Cells treated with free cisplatin exhibited increased yellow fluorescence, indicating chromatin condensation and early apoptosis (Fig. 6d-ii). Following 24 h of treatment with NA-Cis-AuNRs, the cells shifted towards the late apoptotic stage, evidenced by the increase in orange-red fluorescence and nuclear condensation (Fig. 6d-iii). NIR exposure of NA-Cis-AuNRs-treated cells resulted in prominent red fluorescence, suggesting extensive membrane disintegration and EtBr uptake into the nucleus, confirming advanced apoptosis and cell death (Fig. 6d-iv).

Quantitative analysis (Fig. 6e) further confirmed a significant decrease in AO fluorescence and a marked increase in EtBr uptake, underscoring the enhanced cytotoxicity mediated by the combined photothermal and chemotherapeutic approach. These results strongly support the hypothesis that NIR-activated NA-Cis-AuNRs elicit synergistic effects by amplifying ROS production and triggering irreversible cell death pathways. This synergistic photo-chemotherapeutic approach offers a compelling strategy for targeting TNBC, a subtype known for drug resistance and poor clinical outcomes. Previous studies have also demonstrated that NA-based carriers loaded with drugs such as doxorubicin and quercetin can significantly enhance apoptosis, even at low nanomolar doses17,22. Based on these findings, we propose that encapsulation of Cisplatin and AuNRs in NA improves cellular internalization, triggers synergistic effects, and significantly promotes apoptosis.

NA-Cis-AuNRs induce cell cycle arrest

As cancer cells are characterized by uncontrolled cell division and proliferation, any novel treatment modality should ideally target disrupting cell cycle progression at specific phases to enhance cell death. Given the oxidative stress and apoptosis observed with the NA-Cis-AuNRs formulation, we further investigated its impact on cell cycle regulation using flow cytometry following propidium iodide (PI) staining (Fig. 7). The DNA content histogram of untreated control cells (Fig. 7a) shows a predominant population (~ 78%) residing in the G0/G1 phase, and a minimal population in the S and G2/M phases. Figure 7b shows the corresponding histogram for cells treated with NA-Cis-AuNRs and exposed to NIR, demonstrating a shift in cell distribution with substantial accumulation in the S and G2/M phases.

Flow cytometry analysis showing NA-Cis-AuNRs induce cell cycle arrest at S/G2-M phases in TNBC cells. Cell cycle profiles of (a) Control and (b) NA-Cis-AuNRs with NIR from flow cytometry post-staining with propidium iodide. (c) Quantitative comparison of DNA content across various cell cycle phases. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3); significance levels: *** implies P < 0.001.

Figure 7c provides a quantitative comparison of DNA content across cell cycle phases, highlighting a significant decrease in the G0/G1 phase and a marked increase in both the S and G2/M phases. Specifically, the proportion of cells in the S phase increased by approximately 2.2-fold, from 17.5 ± 1% in the control to 39 ± 3% in the treated group, while those in the G2/M phase rose markedly by 8.1-fold, from 6.4 ± 2% to 52.5 ± 2%. In both control and treated groups, minimal sub-G0 accumulation was observed, indicating an absence of early necrotic or degraded cells. Similar results have been reported in other studies, where G2/M arrest was observed at low doses of cisplatin in leukemia and embryonic fibroblasts, whereas sub-G0 phase accumulation occurred at higher cisplatin concentrations80,81.

The observed S/G2 phase arrest correlates well with the nanomolar concentrations of cisplatin used in this study. This is particularly advantageous, as cells in the mitotic phase are known to be hypersensitive to cisplatin, rendering them more susceptible to death at this phase82. Additionally, gold nanoparticles have also been reported to effectively induce S-phase arrest in lung and breast cancer cells, potentially due to their interference with DNA repair mechanisms83. Cisplatin mediates cytotoxicity primarily by binding to DNA and forming intra- and inter-strand crosslinks, resulting in DNA adducts between guanine and adenine bases84. In response to such damage, cells typically activate various repair mechanisms such as nucleotide excision repair and homologous recombination85. We hypothesize that the internalization of the NA-Cis-AuNRs complex enhances cellular sensitivity to cisplatin, contributing to G2/M phase arrest. Furthermore, laser-induced hyperthermia generated by AuNRs augments DNA damage and cellular stress, producing a synergistic effect that amplifies apoptosis and cell death.

NA-Cis-AuNRs induce oxidative DNA damage

Since the NA-Cis-AuNRs, upon NIR exposure, induced significant oxidative stress, we further investigated their impact on oxidative DNA damage. To evaluate this, we measured the levels of 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), a well-established biomarker generated by oxidative attack on guanine residues by reactive oxygen species (ROS). Immunocytochemical staining was performed to detect FITC-tagged 8-OHdG, which was colocalized with the nuclear counterstain Hoechst (Fig. 8). As shown in Fig. 8a, the control group displayed minimal 8-OHdG signal, whereas Fig. 8b (NA-Cis-AuNRs + NIR treatment group) exhibited a pronounced increase in nuclear 8-OHdG localization, as indicated by the arrowheads. This observation confirms enhanced oxidative DNA damage upon treatment.

NA-Cis-AuNRs induce oxidative DNA damage in MDA-MB-231 cells. Immunocytochemical analysis showing the expression of the oxidative DNA damage marker 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) in (A) untreated control cells and (B) cells treated with NA-Cis-AuNRs under NIR irradiation. FITC-labeled 8-OHdG (green) and nuclear counterstain Hoechst (blue) were visualized using fluorescence microscopy. The merged images reveal enhanced nuclear localization of 8-OHdG (indicated by white arrows) in the treated group, confirming increased oxidative DNA damage due to ROS generation and cisplatin-mediated stress. Scale bar = 100 μm.

8-OHdG is a widely recognized marker of oxidative DNA damage in breast neoplasms, particularly in estrogen receptor-negative and progesterone receptor-positive subtypes86. Although it is primarily known as a genotoxic biomarker and a potential non-invasive serum indicator for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and breast cancer87, elevated levels hold strong clinical relevance, especially in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), where baseline levels are comparatively low88. Cisplatin, the chemotherapeutic component in our formulation, is also known to induce oxidative damage, which can exacerbate cellular stress in cancer patients89. In our study, the pronounced increase in 8-OHdG within the nuclei of MDA-MB-231 cells treated with NA-Cis-AuNRs and NIR irradiation demonstrates the formulation’s ability to generate oxidative stress and induce effective DNA damage. This result is consistent with earlier findings in cancer models treated with marine coral-derived Excavatolide C, which also showed elevated 8-OHdG levels90. Collectively, these findings reinforce the efficient delivery and enhanced therapeutic action of Cisplatin achieved through the nanoformulation.

Anti-angiogenic effects of NA-Cis-AuNRs assessed by CAM Assay

Angiogenesis, a major hallmark of tumor progression, facilitates metastasis by supplying essential nutrients and oxygen to rapidly growing tumors91. The CAM assay is a robust and well-established in ovo model for evaluating angiogenesis and the expression of angiogenic factors under tumor-like conditions92. It enables the assessment of drug-induced anti-angiogenic effects by quantifying vascular responses in the presence of tumor cells and treatment formulations. Figure 9 provides a comprehensive evaluation of the anti-angiogenic potential of NA-Cis-AuNRs using the CAM model, illustrating both morphological and quantitative changes in vascular development following treatment. Quantitative parameters, including vessel area, length, thickness, and the number of branching points, were analyzed to evaluate the angiogenic response and therapeutic efficacy of the formulation. Figure 9a depicts representative bright-field images depicting CAM vasculature taken at 0 and 6 h following the administration of MDA-MB-231 tumor cells, along with the respective treatment formulations. The results showed that the tumor group exhibited dense and highly branched vasculature, indicating the strong angiogenetic potential of MDA-MB-231 cells. In contrast, the group treated with NA-Cis-AuNRs under NIR exposure demonstrated a notable reduction in vascular density.

CAM assay depicting the anti-angiogenic effects of NA-Cis-AuNRs by suppression of tumor-induced vascularization. (a) Microscopy images of the CAM vasculature taken at 0 and 6 h after seeding MDA-MB-231 tumor cells and treatment components. (b) Fold change in (i) vessel area, (ii) vessel length, (iii) vessel thickness, iv) number of branching points of mature blood vessels in CAM. ** implies P < 0.01.

Figure 9b represents the quantitative analysis of fold changes in all four key angiogenic parameters. As shown in Fig. 9b. i-iv, tumor group exhibited a significant increase in vessel area (1.9-fold), length (1.9-fold), thickness (1.8-fold), and number of branching points (twofold) at 166 h, which are critical indicators of angiogenesis and tumor vascularization.

Conversely, this effect was significantly reversed in all four measured parameters after treatment with NA-Cis-AuNRs at 6 h, and NIR exposure further enhanced this effect with vessel area (1.1 and 0.7-fold), length (1.1 and 0.8-fold), thickness (1.1 and 0.8-fold), and number of branching points (1.2 and 0.8-fold), respectively. This synergistic action is likely due to the photothermal activation of AuNRs, which not only disrupts the tumor microenvironment but also improves drug penetration and local cytotoxicity. The reduced vascular branching and density suggest effective suppression of tumor-induced neovascularization, a key hallmark of aggressive tumor progression.

Previous studies have demonstrated that biodegradable silica-based polymeric nano-architectures loaded with cisplatin and gold nanoparticles exhibit similar anti-angiogenic properties against solid tumors at micromolar cisplatin concentrations93. Interestingly, NA-Cis-AuNRs formulation achieved comparable effects at nanomolar cisplatin levels, underscoring its superiority over conventional drug carriers for efficient delivery of ultra-low drug doses and enhanced therapeutic efficacy. On the whole, our findings underscore the dual therapeutic capability of the NA-Cis-AuNRs system, combining chemotherapeutic and photothermal modalities for targeted anti-angiogenic therapy in TNBC.

NA-Cis-AuNRs suppress angiogenic factors in the tumor microenvironment model

To further validate the role of angiogenic transcription factors in the above experiment, RNA was isolated from developing CAM blood vessels and analyzed by RT-qPCR to assess the expression of key angiogenic transcription factors, suggesting their role in promoting the proliferation of endothelial cells and the formation of capillary-like structures. ANG1, which is vital for vessel stabilization and maturation, showed a 3.2-fold increase, indicating that tumors actively enhance vascular integrity to ensure a consistent supply of oxygen and nutrients, supporting their growth and metastasis.

Figure 10 illustrates the fold change in mRNA expression levels of key angiogenic factors, VEGFA, FGF2, and ANG1in the CAM assay following treatment with NA-Cis-AuNRs, with or without NIR exposure. Treatment with NA-Cis-AuNRs, with or without NIR exposure, demonstrated an anti-angiogenic effect by significantly downregulating the expression of VEGFA, FGF2, and ANG1 genes, which correspondingly reduced by 1.3, 1.4, and 1.1-fold for NA-Cis-AuNRs without NIR exposure and by 1.7, 2, and 2.3-fold for NA-Cis-AuNRs with NIR exposure compared to the tumor group. Compared to the control, treatment with NA-Cis-AuNRs alone resulted in a moderate downregulation of these angiogenic genes, indicating a partial inhibitory effect on angiogenesis. However, the combination of NA-Cis-AuNRs with NIR irradiation led to a significant reduction in the expression levels of VEGFA, FGF2, and ANG1, highlighting the enhanced anti-angiogenic efficacy of the photothermal-chemotherapy strategy.

Gene expression analysis confirming downregulation of pro-angiogenic and proliferation markers following NA-Cis-AuNRs treatment under NIR irradiation. Relative mRNA expression levels of VEGF, FGF, and ANGPT-1 in treated and control groups were quantified by RT-qPCR. Values are normalized to β-actin expression. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 3); significance levels: p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***).

Previous studies have reported that gold nanoparticles can suppress angiogenesis by downregulating components of the Akt pathway in endothelial cells, which is critical for their proliferation and survival94. Continuous administration of low-dose cisplatin to mice and CAM models has been shown to decrease micro-vessel density and VEGF expression in a metronomic chemotherapeutic model, which is similar to the observed effects in the in ovo model95. Our findings are consistent with these reports and further demonstrate that NA-Cis-AuNRs exert a potent anti-angiogenic effect at significantly lower drug concentrations.

We also analyzed the expression of FGF2 and ANG1, two key regulators involved in endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and vascular maturation. Their expression levels were markedly elevated in the tumor group, but declined markedly following NA-Cis-AuNRs treatment and subsequent NIR irradiation. This substantial downregulation in all three markers (VEGFA, FGF2, and ANG1) highlights the synergistic anti-angiogenic potential of NA-Cis-AuNRs under photothermal activation, indicating a potential strategy for targeting tumor angiogenesis in TNBC.

Conclusion

This study presents a stable and biocompatible nanoarchaeosome system loaded with cisplatin and PEGylated gold nanorods for NIR-triggered synergistic photochemotherapy with NIR. The nanoformulation enabled controlled, on-demand drug release upon NIR exposure and demonstrated anticancer activity against MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells at nanomolar levels. The treatment resulted in oxidative stress–mediated apoptosis, and it appears to be effective in preventing the formation of angiogenic effects. The platform addresses the limitations of conventional nanocarriers by improving stability, eliminating systemic toxicity, and facilitating spatially controlled drug delivery. This paper provides direct evidence that this multifunctional nanostructure can translate to aggressive cancers such as TNBC. In addition, further validation of mammalian tumor models is needed for preclinical efficacy and clinical translation.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263 (2024).

Derakhshan, F. & Reis-Filho, J. S. Pathogenesis of triple-negative breast cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2022(17), 181–204 (2022).

Gong, Y. et al. Metabolic-pathway-based subtyping of triple-negative breast cancer reveals potential therapeutic targets. Cell Metab. 33, 51-64.e9 (2021).

Afifi, N. & Barrero, C. A. Understanding breast cancer aggressiveness and its implications in diagnosis and treatment. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12041375 (2023).

Seamus McAleer. A History of Cancer and Its Treatment. http://www.ums.ac.uk (2021).

National Cancer Institute, N. Milestones in Cancer Research and Discovery.

Overchuk, M., Weersink, R. A., Wilson, B. C. & Zheng, G. Photodynamic and photothermal therapies: Synergy opportunities for nanomedicine. ACS Nano 17, 7979–8003. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.3c00891 (2023).

Itoo, A. M., Paul, M., Ghosh, B. & Biswas, S. Polymeric graphene oxide nanoparticles loaded with doxorubicin for combined photothermal and chemotherapy in triple negative breast cancer. Biomater. Adv. 153 (2023).

dos Santos Jesus, V. P. et al. Triple-negative breast cancer treatment in xenograft models by bifunctional nanoprobes combined to photodynamic therapy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 38 (2022).

Pal, S. et al. DNA-functionalized gold nanorods for perioperative optical imaging and photothermal therapy of triple-negative breast cancer. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 5, 9159–9169 (2022).

Liu, S., Phillips, S., Northrup, S. & Levi, N. The impact of silver nanoparticle-induced photothermal therapy and its augmentation of hyperthermia on breast cancer cells harboring intracellular bacteria. Pharmaceutics 15 (2023).

Yang, H. et al. Docetaxel-encapsulated catalytic Pt/Au nanotubes for synergistic chemo-photothermal therapy of triple-negative breast cancer. Adv. Healthc. Mater. https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.202400662 (2024).

Singh, P. et al. Palladium nanocapsules for photothermal therapy in the near-infrared II biological window. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 39081–39098 (2023).

Keyvan Rad, J., Alinejad, Z., Khoei, S. & Mahdavian, A. R. Controlled release and photothermal behavior of multipurpose nanocomposite particles containing encapsulated gold-decorated magnetite and 5-FU in Poly(lactide-co-glycolide). ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 5, 4425–4434 (2019).

Chen, J. et al. Recent advances and clinical translation of liposomal delivery systems in cancer therapy. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2023.106688 (2024).

Sarnelli, S., Baldino, L. & Reverchon, E. Production and optimization of lipid-based “stealth nanocarriers” by supercritical technology. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp 699 (2024).

Babunagappan, K. V. et al. Doxorubicin loaded thermostable nanoarchaeosomes: A next-generation drug carrier for breast cancer therapeutics. Nanoscale Adv. 6, 2026–2037 (2024).

Ghosh, S. Cisplatin: The first metal based anticancer drug. Bioorg. Chem. 88, 102925 (2019).

Rocha, C. R. R., Silva, M. M., Quinet, A., Cabral-Neto, J. B. & Menck, C. F. M. DNA repair pathways and cisplatin resistance: an intimate relationship. Clinics 73, e478s (2018).

Zhang, F. et al. Death pathways of cancer cells modulated by surface molecule density on gold nanorods. Adv. Sci. 8 (2021).

Cui, X., Cheng, W. & Han, X. Lipid bilayer modified gold nanorod@mesoporous silica nanoparticles for controlled drug delivery triggered by near-infrared light. J. Mater. Chem. B 6, 8078–8084 (2018).

Subastri, A., Abirami, S., VijayalakshmiBabunagappan, K. & Swathi, S. Quercetin-loaded nanoarchaeosomes for breast cancer therapy: A ROS mediated cell death mechanism. Mater. Adv. 5, 6944–6956 (2024).

Babunagappan, K. V., Raj, T., Seetharaman, A., Ariraman, S. & Sudhakar, S. Elucidating shape-mediated drug carrier mechanics of hematite nanomaterials for breast cancer therapeutics. J. Mater. Chem. B 12, 4843–4853 (2024).

Vimalraj, S., Partridge, N. C. & Selvamurugan, N. A positive role of MicroRNA-15b on regulation of osteoblast differentiation. J. Cell Physiol. 229, 1236–1244 (2014).

Mi, P. Stimuli-responsive nanocarriers for drug delivery, tumor imaging, therapy and theranostics. Theranostics 10, 4557–4588 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Multifunctional nanoparticle-mediated combining therapy for human diseases. Signal Transd. Targeted Ther. 9, 1–33 (2024).

Taylor, M. L., Wilson, R. E., Amrhein, K. D. & Huang, X. Gold nanorod-assisted photothermal therapy and improvement strategies. Bioengineering 9, 200 (2022).

Shi, Y., van der Meel, R., Chen, X. & Lammers, T. The EPR effect and beyond: Strategies to improve tumor targeting and cancer nanomedicine treatment efficacy. Theranostics 10, 7921–7924 (2020).

Sharifi, M. et al. An updated review on EPR-based solid tumor targeting nanocarriers for cancer treatment. Cancers 14, 2868 (2022).

Omping, J. et al. Facile synthesis of PEGylated gold nanoparticles for enhanced colorimetric detection of histamine. ACS Omega 9, 14269–14278 (2024).

Chen, H. et al. ‘Living’ PEGylation on gold nanoparticles to optimize cancer cell uptake by controlling targeting ligand and charge densities. Nanotechnology (2013).

Sharma, S., Shukla, P., Misra, A. & Mishra, P. R. Interfacial and colloidal properties of emulsified systems: Pharmaceutical and biological perspective. Pharmaceutical and biological perspective, in Colloid and Interface Science in Pharmaceutical Research and Development 149–172 (Elsevier Inc., 2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-62614-1.00008-9.

Clogston, J. D. & Patri, A. K. Zeta potential measurement,in Methods in Molecular Biology vol. 697, 63–70 (Humana Press Inc., 2011).

Santhosh, P. B. & Genova, J. Archaeosomes: New generation of liposomes based on archaeal lipids for drug delivery and biomedical applications. ACS Omega 8, 1–9 (2023).

Sundararajan, B. & RanjithaKumari, B. D. Novel synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Artemisia vulgaris L. leaf extract and their efficacy of larvicidal activity against dengue fever vector Aedes aegypti L.. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 43, 187–196 (2017).

Farooq, M. A. et al. Recent progress in nanotechnology-based novel drug delivery systems in designing of cisplatin for cancer therapy: An overview. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 47, 1674–1692 (2019).

Gu, C., Geng, Y., Zheng, F. & Rotello, V. M. Rapid evaluation of gold nanoparticle-lipid membrane interactions using a lipid/polydiacetylene vesicle sensor. Analyst 145, 3049–3055 (2020).

Sobol, Ż, Chiczewski, R. & Wątróbska-Świetlikowska, D. Advances in liposomal drug delivery: multidirectional perspectives on overcoming biological barriers. Pharmaceutics 17, 885 (2025).

Gombotz, W. R. & Wee, S. F. Protein release from alginate matrices. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 64, 194–205 (2012).

Hildebrandt, B. et al. The cellular and molecular basis of hyperthermia. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 43, 33–56 (2002).

Weissleder, R. A clearer vision for in vivo imaging: Progress continues in the development of smaller, more penetrable probes for biological imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 19, 316–317 (2001).

Smith, A. M., Mancini, M. C. & Nie, S. Bioimaging: Second window for in vivo imaging. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 710–711 (2009).

O’Neal, D. P., Hirsch, L. R., Halas, N. J., Payne, J. D. & West, J. L. Photo-thermal tumor ablation in mice using near infrared-absorbing nanoparticles. Cancer Lett. 209, 171–176 (2004).

Stern, J. M., Stanfield, J., Kabbani, W., Hsieh, J. T. & Cadeddu, J. A. Selective prostate cancer thermal ablation with laser activated gold nanoshells. J. Urol. 179, 748–753 (2008).

Rastinehad, A. R. et al. Gold nanoshell-localized photothermal ablation of prostate tumors in a clinical pilot device study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 116, 18590–18596 (2019).

Kim, 1.752Q1SJR Q1; 1.752NAABS NANAABDC NALung CancerES et al. A phase II study of STEALTH cisplatin (SPI-77) in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. ElsevierES Kim, C Lu, FR Khuri, M Tonda, BS Glisson, D Liu, M Jung, WK Hong, RS HerbstLung Cancer, 2001•Elsevier https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169500201002781

Plummer, R. et al. A Phase I clinical study of cisplatin-incorporated polymeric micelles (NC-6004) in patients with solid tumours. nature.comR Plummer, RH Wilson, H Calvert, AV Boddy, M Griffin, J Sludden, MJ Tilby, M EatockBritish journal of cancer, 2011•nature.com 104, 593–598 (2011).

Mizumura, Y. et al. Cisplatin‐incorporated polymeric micelles eliminate nephrotoxicity, while maintaining antitumor activity. Wiley Online LibraryY Mizumura, Y Matsumura, T Hamaguchi, N Nishiyama, K Kataoka, T KawaguchiJapanese journal of cancer research, 2001•Wiley Online Library 92, 328–336 (2001).

England, C. G., Miller, M. C., Kuttan, A., Trent, J. O. & Frieboes, H. B. Release kinetics of paclitaxel and cisplatin from two and three layered gold nanoparticles. ElsevierCG England, MC Miller, A Kuttan, JO Trent, HB FrieboesEuropean Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, 2015•Elsevier 92, 120–129 (2015).

drugs, 1.267Q1SJR Q1; 1.267NAABS NANAABDC NAExpert opinion on investigational drugsT Boulikas - Expert opinion on investigational & 2009, undefined. Clinical overview on Lipoplatin: a successful liposomal formulation of cisplatin. Taylor & FrancisT BoulikasExpert opinion on investigational drugs, 2009•Taylor & Francis 18, 1197–1218 (2009).

Jiménez-López, M. C. et al. Novel cisplatin-magnetoliposome complex shows enhanced antitumor activity via Hyperthermia. nature.comMC Jiménez-López, AC Moreno-Maldonado, N Martín-Morales, F O’Valle, MR IbarraScientific Reports, 2025•nature.com 15 (2025).

Viitala, L. et al. Photothermally triggered lipid bilayer phase transition and drug release from gold nanorod and indocyanine green encapsulated liposomes. Langmuir 32, 4554–4563 (2016).

Yan, F. et al. NIR-laser-controlled drug release from DOX/IR-780-loaded temperature-sensitive-liposomes for chemo-photothermal synergistic tumor therapy. Theranostics 6, 2337–2351 (2016).

Wang, Y., Huang, Y. Y., Wang, Y., Lyu, P. & Hamblin, M. R. Photobiomodulation of human adipose-derived stem cells using 810 nm and 980 nm lasers operates via different mechanisms of action. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1861, 441–449 (2017).

Li, S., Wong, T. W. L. & Ng, S. S. M. Potential and challenges of transcranial photobiomodulation for the treatment of stroke. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 30, e70142 (2024).

Mahmoud, N. N., Al-Kharabsheh, L. M., Khalil, E. A. & Abu-Dahab, R. Interaction of gold nanorods with human dermal fibroblasts: cytotoxicity, cellular uptake, and wound healing. Nanomaterials 9, 1131 (2019).

Zhang, L., Ma, Y., Wei, Z. & Wang, L. Toxicity of gold nanoparticles complicated by the co-existence multiscale plastics. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1447046 (2024).

Yang, D. H. et al. A review on gold nanoparticles as an innovative therapeutic cue in bone tissue engineering: Prospects and future clinical applications. Mater. Today Bio. 26, 101016 (2024).

Dasari, S. & Bernard Tchounwou, P. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: Molecular mechanisms of action. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 740, 364–378 (2014).

Wang, D. & Lippard, S. J. Cellular processing of platinum anticancer drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 4, 307–320 (2005).

Mirmalek, S. A. et al. Comparison of in vitro cytotoxicity and apoptogenic activity of magnesium chloride and cisplatin as conventional chemotherapeutic agents in the MCF-7 cell line. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 17, 131–134 (2016).

Perez, R. P. Cellular and molecular determinants of cisplatin resistance. Eur. J. Cancer 34, 1535–1542 (1998).

Chakraborty, C., Sharma, A. R., Sharma, G. & Lee, S. S. Zebrafish: A complete animal model to enumerate the nanoparticle toxicity. J. Nanobiotechnol. 14 (2016).

Chakraborty, C., Sharma, A. R., Sharma, G. & Lee, S. S. Zebrafish: A complete animal model to enumerate the nanoparticle toxicity. J. Nanobiotechnol. 14, 1–13 (2016).

Padovani, B. N. et al. Cisplatin toxicity causes neutrophil-mediated inflammation in zebrafish larvae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 2363 (2024).

Hartmann, S. et al. Zebrafish larvae show negative phototaxis to near-infrared light. PLoS One 13 (2018).

Padovani, B. N. et al. Cisplatin toxicity causes neutrophil-mediated inflammation in zebrafish larvae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 (2024).

Lee, D. S., Schrader, A., Bell, E., Warchol, M. E. & Sheets, L. Evaluation of cisplatin-induced pathology in the larval zebrafish lateral line. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (2022).

Koh, M. Z. et al. Regulation of cellular and cancer stem cell-related putative gene expression of parental and cd44+ cd24− sorted mda-mb-231 cells by cisplatin. Pharmaceuticals 14 (2021).

Hashemi, M. et al. Mechanistic insights into cisplatin response in breast tumors: Molecular determinants and drug/nanotechnology-based therapeutic opportunities. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res 794, 108513 (2024).

Xu, C. & Pu, K. Second near-infrared photothermal materials for combinational nanotheranostics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 1111–1137. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0cs00664e (2021).

Patyar, R. R., Patyar, S., Sharma, Y. P. & Khanduja, K. L. Flow-cytometric analysis of reactive oxygen species in blood cells: a potential tool for predicting restenosis - Insights from a cohort study. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Disorders-Drug Targets 25, 21–32 (2025).

Daei, S., Abbasalipourkabir, R., Khanaki, K., Bahreini, F. & Ziamajidi, N. Effects of gold nanoparticles on oxidative stress status in bladder cancer 5637 cells. Folia Med. (Plovdiv.) 64, 641–648 (2022).

Brozovic, A., Ambriović-Ristov, A. & Osmak, M. The relationship between cisplatin-Induced reactive oxygen species, glutathione, and BCL-2 and resistance to cisplatin. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 40, 347–359. https://doi.org/10.3109/10408441003601836 (2010).

Sun, Y. et al. ent-Kaurane diterpenoids induce apoptosis and ferroptosis through targeting redox resetting to overcome cisplatin resistance. Redox Biol 43 (2021).

Kleih, M. et al. Direct impact of cisplatin on mitochondria induces ROS production that dictates cell fate of ovarian cancer cells. Cell Death Dis 10 (2019).

Liu, K. et al. Dual AO/EB staining to detect apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells compared with flow cytometry. Med. Sci. Monit. Basic Res. 21, 15–20 (2015).

Smith, S. M., Ribble, D., Goldstein, N. B., Norris, D. A. & Shellman, Y. G. A simple technique for quantifying apoptosis in 96-well plates. Methods Cell Biol. 112, 361–368 (2012).

Crowley, L. C., Marfell, B. J. & Waterhouse, N. J. Detection of DNA Fragmentation in Apoptotic Cells by TUNEL. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2016, pdb.prot087221 (2016).

Velma, V., Dasari, S. R. & Tchounwou, P. B. Low doses of cisplatin induce gene alterations, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia cells. Biomark. Insights 11, 113–121 (2016).

Yuan, L., Yu, W. M., Xu, M. & Qu, C. K. SHP-2 phosphatase regulates DNA damage-induced apoptosis and G 2/M arrest in catalytically dependent and independent manners, respectively. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42701–42706 (2005).