Abstract

This retrospective observational study compared the outcomes of transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) versus open surgery in patients with blunt abdominal solid organ injury (liver, spleen, or kidney; abdominal Abbreviated Injury Scale [AIS] ≥ 3) with traumatic brain injury (TBI) (head AIS ≥ 3), using data from the Japan Trauma Data Bank (2004–2019). Patient characteristics were adjusted using propensity score matching. The primary endpoint was in-hospital mortality; secondary endpoints included 48-h mortality, transfusion requirements, and complications. After matching, 135 patients per group were analyzed. In-hospital mortality was significantly lower in the TAE group (25/135 [18.5%] vs. 42/135 [31.1%], adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 0.247, 95% confidence interval 0.101–0.605, p = 0.002). TAE also showed lower 48-h mortality (10/135 [7.4%] vs. 22/135 [16.3%], AOR 0.306, p = 0.008) and transfusion rates. Complication rates were similar. Subgroup analysis showed that TAE was associated with lower mortality in non-shock (AOR 0.392, p = 0.032), elderly (AOR 0.293, p = 0.044), and focal TBI patients (AOR 0.301, p = 0.004) but not in patients with diffuse TBI. TAE may be a feasible treatment option for selected patients with blunt abdominal solid organ injury complicated by TBI, particularly in hemodynamically stable, elderly, and focal TBI patients. These findings require prospective validation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Blunt abdominal trauma is a frequent injury in trauma patients. The rate of intra-abdominal organ injury among patients with blunt abdominal trauma presenting to the emergency department is approximately 13%1.

Traditionally, immediate open surgery has been the standard of care for suspected intra-abdominal injuries from blunt abdominal trauma2. However, less invasive treatments, such as transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE), have been established as viable therapeutic alternatives3. In current clinical practice, for arterial bleeding resulting from abdominal solid organ injury, TAE is typically selected for hemodynamically stable patients, while open surgery is preferred for those who are hemodynamically unstable4,5. The effectiveness of TAE in hemodynamically stable patients with blunt splenic injury is well known, with TAE increasing the success rate of non-operative management6,7,8,9. Similarly, the effectiveness of TAE, when patients are appropriately selected, has also been reported for liver and kidney injuries10,11,12.

Research on blunt abdominal trauma complicated by traumatic brain injury (TBI) is limited, and treatment strategies and outcomes remain unclear. TBI induces the release of tissue factor (TF), resulting in coagulopathy, making hemorrhage control more challenging13. Furthermore, patients with TBI require careful management to avoid hypotension and hypoxemia to prevent secondary brain injury14,15. This creates a complex clinical scenario where neurosurgical management of TBI must be balanced against hemodynamic instability caused by intra-abdominal bleeding, while abdominal interventions may be delayed or modified based on intracranial pressure considerations16. Therefore, when treating concurrent abdominal injuries, it becomes crucial to select treatment modalities that minimize additional physiological stress, surgical trauma, and hemodynamic instability.

For abdominal hemorrhage control, two primary approaches are available. Open surgery allows direct management of bleeding and can address multiple injuries simultaneously; however, it is highly invasive and may exacerbate TBI-associated coagulopathy through additional TF release and surgical stress. In contrast, TAE offers minimally invasive hemostasis with reduced physiological stress, although its use is limited to specific conditions, such as arterial bleeding.

There is little research directly comparing TAE and open surgery in patients with combined TBI and abdominal solid organ injury. Most studies focus on managing either TBI or abdominal trauma, overlooking the unique challenges presented by their coexistence.

Whether conventional treatment decisions based solely on hemodynamic status are appropriate for patients with abdominal organ injuries complicated by TBI remains unclear. Furthermore, the influence of varying TBI injury patterns on treatment outcomes remains understudied. Therefore, we compared the treatment outcomes of TAE versus open surgery in patients with blunt abdominal organ injury complicated by TBI. We hypothesized that TAE could be safely performed in selected patients with concurrent TBI, rather than being universally superior to open surgery. Specifically, we aimed to identify patient subgroups in which the minimally invasive nature of TAE might offer comparable or improved outcomes while avoiding the additional physiological stress associated with laparotomy.

Results

Study population

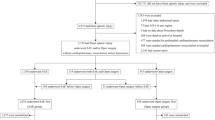

Of the 338,744 cases registered in the Japan Trauma Data Bank (JTDB) between 2004 and 2019, 673 met the inclusion criteria. After excluding 210 cases based on the exclusion criteria, 463 cases were finally analyzed. TAE was performed in 300 cases and open surgery in 163 cases as the initial hemostatic treatment. After multiple imputation (20 datasets) and propensity score matching performed within each imputed dataset, 135 cases from each group were consistently matched across all datasets for the comparative analysis (Fig. 1).

Patient flow diagram. Flow diagram showing the selection of study patients from the Japan Trauma Data Bank. Of the 338,744 patients registered between 2004 and 2019, 463 met the inclusion criteria after applying the exclusion criteria. Missing data were handled using multiple imputation (20 datasets). Propensity score matching was performed within each imputed dataset, resulting in 135 patients who underwent transcatheter arterial embolization being matched with 135 patients who underwent open surgery across all imputed datasets. AIS Abbreviated Injury Scale, JTDB Japan Trauma Data Bank, TAE, transcatheter arterial embolization, SBP systolic blood pressure, HR, heart rate.

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics were assessed using a representative dataset (the first imputed dataset) to demonstrate the effectiveness of propensity score matching. Before matching, there was a minimal difference in age between the two groups (open surgery: 46.34 [23.20] years; TAE: 49.28 [22.83] years; standardized mean difference [SMD] = 0.128) but notable differences in severity indices. The Injury Severity Score (ISS) was higher in the open surgery group (median 43 [36.00, 57.00] vs. 41 [34.00, 48.00]; SMD = 0.511), as were the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) scores for the head (SMD = 0.346) and abdomen (SMD = 0.550). The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was lower in the open surgery group (median 8.00 [6.00, 13.00] vs. 12.00 [7.00, 14.00]; SMD = 0.414). Regarding vital signs, the open surgery group had a lower systolic blood pressure (SBP) (100 mmHg vs. 112 mmHg; SMD = 0.369) and a higher heart rate (HR) (109 bpm vs. 100 bpm; SMD = 0.247). Consequently, the proportion of patients in shock (SBP < 90 mmHg) was higher in the open surgery group (64/163 [39.3%] vs. 76/300 [25.3%]; SMD = 0.301). Minor differences were also noted in the distribution of injury periods (SMD = 0.106) and in the breakdown of injured organs.

After propensity score matching, 135 cases from each group were analyzed. Adequate overlap was achieved between the treatment groups (Supplementary Fig. S1). Most baseline characteristics were well-balanced. However, some brain injury-related variables showed residual imbalance with SMD > 0.1, including cranial surgery rates (15.6% vs. 8.1%, SMD = 0.231) and subdural hematoma (32.6% vs. 20.7%, SMD = 0.270). While these imbalances were noted, our double adjustment approach included adjustment for overall injury severity (ISS and AIS scores), which should partially account for these differences. Time from arrival to hemostatic intervention was not significantly different between the groups (median [interquartile range]: open surgery 130 [75–185] min vs. TAE 102 [71–147.5] min, SMD = 0.044). Treatment conversion was rare in both groups (open surgery to TAE: 8/135 [5.9%], TAE to open surgery: 6/135 [4.4%]) (Table 1).

Outcomes

Regarding the primary endpoint, the TAE group had significantly lower in-hospital mortality (18.5% [25/135] vs. 31.1% [42/135]; odds ratio [OR] 0.247, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.101–0.605; p = 0.002).

For the secondary endpoints, the TAE group showed significantly lower early mortality within 48 h (7.4% [10/135] vs. 16.3% [22/135]; OR 0.306, 95% CI 0.128–0.734; p = 0.008), transfusion within 24 h (51.1% [69/135] vs. 67.4% [91/135]; OR 0.382, 95% CI 0.183–0.798; p = 0.011), and in-hospital transfusion (77.0% [104/135] vs. 88.1% [119/135]; OR 0.384, 95% CI 0.170–0.867; p = 0.021). There were no significant between-group differences in complication rates (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Forest Plot of Primary and Secondary Outcomes Comparing TAE and Open Surgery. Forest plot showing odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for in-hospital mortality, 48-h mortality, transfusion requirements, and complications. Values < 1.0 favor TAE, while values > 1.0 favor open surgery. CI, confidence interval; TAE, transcatheter arterial embolization. CI, confidence interval; TAE, transcatheter arterial embolization.

Kaplan–Meier analysis showed significantly better 30-day survival in the TAE group (p = 0.021) (Fig. 3).

Kaplan–Meier Survival Curves for 30-Day Mortality. Kaplan–Meier curves showing 30-day survival probability for the propensity score-matched transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) and open surgery groups. The number of patients at risk is shown below the graph. The p-value was determined by pooled Cox regression results (p = 0.021). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Subgroup analysis

In patients without shock (n = 182), in-hospital mortality was significantly lower in the TAE group (OR 0.392, 95% CI 0.167–0.923; p = 0.032). Among patients with shock (n = 88), no significant difference was observed (OR 0.363, 95% CI 0.111–1.187; p = 0.094).

In the age-stratified analysis, among elderly patients ≥ 65 years (n = 81), TAE was associated with significantly lower in-hospital mortality (OR 0.293, 95% CI 0.089–0.966; p = 0.044). Among non-elderly patients < 65 years (n = 189), the difference was not statistically significant (OR 0.437, 95% CI 0.174–1.097; p = 0.078).

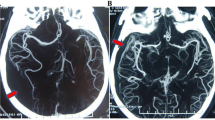

In the brain injury type-stratified analysis, patients with focal TBI (n = 198) had significantly lower mortality in the TAE group (OR 0.301, 95% CI 0.132–0.687; p = 0.004). Conversely, no significant difference was found in the diffuse-TBI group (n = 20) (OR 0.355, 95% CI 0.008–16.609; p = 0.597) (Table 3; Fig. 4). Sensitivity analyses using different age cutoffs (60 and 70 years) showed results consistent with the primary analysis (Supplementary Table S1).

Forest Plot of Subgroup Analysis for In-Hospital Mortality. Forest plot showing odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for in-hospital mortality across predefined subgroups. The vertical line at 1.0 indicates no difference between the TAE and open surgery groups. OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, TAE transcatheter arterial embolization, TBI traumatic brain injury.

Discussion

This study found that TAE may be a feasible treatment option for selected patients with blunt abdominal solid organ injury complicated by TBI, particularly those who are hemodynamically stable.

Our initial hypothesis that TAE might be safely performed in selected patients with concurrent TBI, rather than being universally superior to open surgery, was partially confirmed. The results demonstrated that TAE was indeed associated with lower mortality in specific subgroups, particularly patients without shock (OR 0.392, p = 0.032) and those with focal TBI (OR 0.301, p = 0.004), while showing no significant benefit in patients with shock or diffuse TBI. This selective efficacy aligns with our hypothesis that the minimally invasive nature of TAE would be advantageous in patients who could tolerate the procedure without compromising hemodynamic stability.

Current guidelines recommend prompt surgical intervention for abdominal solid organ injury in patients with severe TBI to prevent secondary brain injury due to hypotension4,5. Our analysis showed comparable time from arrival to hemostatic intervention between open surgery and TAE (median 130 vs. 102 min), with TAE actually trending toward shorter times, although the difference was not statistically significant. This suggests that, in appropriately selected patients and institutions with adequate resources, TAE can be performed as expeditiously as open surgery. However, this may reflect selection bias, as TAE was likely only offered to patients stable enough to safely undergo angiography.

Damage-control surgery (DCS) limits initial interventions to rapid hemorrhage control and contamination management in critically ill patients with physiological compromise, prioritizing stabilization in the intensive care unit17. DCS has demonstrated high utility, especially in cases involving hemorrhagic shock and multiple injuries18,19,20. However, DCS also carries risks, including infection, worsening hypothermia and coagulopathy, and the need for increased fluid resuscitation.

It is important to emphasize that our results should not be interpreted as evidence that TAE is superior to open surgery in all patients. Rather, they suggest that TAE can be performed safely in carefully selected patients with concurrent TBI, providing clinicians with an additional therapeutic option for managing these complex cases. The choice between TAE and open surgery should remain individualized based on hemodynamic status, injury pattern, and institutional capabilities.

In this context, TAE is a promising alternative for hemodynamically stable patients. Nonetheless, open surgery remains the treatment of choice for patients with severe hemodynamic instability or when surgical intervention is necessary. Treatment selection decisions become even more critical in cases complicated by TBI. The primary mechanism underlying TBI-associated coagulopathy involves the release of TF from damaged brain tissue21,22. TF forms complexes with factor VII, activating the coagulation cascade. Furthermore, disruption of the blood-brain barrier facilitates the entry of these coagulation factors into systemic circulation and the local release of inflammatory mediators21,22. These changes lead to increased thrombin generation and abnormal activation of the fibrinolytic system, potentially progressing to consumptive coagulopathy. Under such conditions, open surgery may exacerbate existing coagulopathy by promoting further TF release through extensive tissue damage. Conversely, TAE may interrupt this vicious cycle by minimizing additional tissue injury.

The subgroup analysis results provide insights into patient selection for TAE. In the non-shock subgroup, TAE was associated with significantly lower mortality (OR 0.392, p = 0.032), suggesting it may be a viable option for hemodynamically stable patients. This finding may reflect that, when circulatory dynamics are maintained, the minimally invasive nature of TAE allows effective hemorrhage control while avoiding the additional physiological stress associated with laparotomy.

In contrast, no significant difference was observed between treatment modalities in the shock group (OR 0.363, p = 0.094). In patients with severe circulatory failure, existing coagulopathy from tissue hypoperfusion and metabolic acidosis, when compounded by TBI-associated coagulopathy, may determine outcomes regardless of the hemostatic approach. This suggests that, in hemodynamically unstable patients, the speed of hemorrhage control may be more critical than the specific method used.

Age-related differences in response to surgical stress may also explain our subgroup findings. Surgical stress increases inflammatory cytokine production, activates the sympathetic nervous system, and alters immune responses23. These effects are more pronounced in elderly patients than in younger individuals24. Moreover, in elderly patients with TBI, decreased cerebrovascular autoregulation and comorbidities further increase the risk of secondary brain injury25,26. The effectiveness of TAE was evident in the elderly group (≥ 65 years; OR 0.293, 95% CI 0.089–0.966, p = 0.044), where the minimally invasive nature of TAE may provide greater benefit compared to the surgical stress of open surgery. However, the wide confidence interval reflects the limited sample size in this subgroup (n = 81), and these findings should be interpreted with caution. In contrast, non-elderly patients may have sufficient physiological reserve to tolerate open surgery.

A particularly noteworthy finding was the difference in treatment effects by TBI type. Focal TBI is characterized by localized brain tissue damage resulting from direct impact, which involves local TF release and secondary changes concentrated at the injury site27. In our study, TAE was associated with significantly lower mortality in the focal-TBI group (OR 0.301, p = 0.004). The minimally invasive nature of TAE may have contributed to favorable outcomes by limiting systemic inflammatory responses and further TF release, thereby minimizing coagulopathy progression.

Conversely, diffuse TBI is characterized by widespread axonal damage primarily caused by rapid acceleration-deceleration forces, resulting in more extensive TF release and systemic effects. In the diffuse-TBI group, no significant difference was observed between treatment modalities (OR 0.355, p = 0.597). In these cases, coagulopathy may already be well advanced, and the severity of the underlying injury may have a greater impact on prognosis than the treatment approach. However, the relatively small sample size in the diffuse-TBI group (n = 20) warrants cautious interpretation of these findings.

This study had some limitations. First, as a retrospective observational study with non-randomized treatment allocation, the analysis is subject to potential selection bias. Despite propensity score matching, residual confounding may persist, and unmeasured factors related to injury severity or physiological status may have influenced treatment selection and outcomes. Therefore, our findings should be considered as hypothesis-generating rather than as definitive evidence for treatment recommendations. Although propensity score matching achieved acceptable balance for most variables, some brain injury-related variables retained moderate imbalance (SMD > 0.2), particularly cranial surgery rates (SMD = 0.231) and subdural hematoma (SMD = 0.270). Although we addressed this through double adjustment using outcome models, these imbalances may reflect unmeasured differences in TBI severity between the groups.

Second, the JTDB primarily targets patients with severe trauma, and potential selection bias may arise from the database’s inclusion criteria and variability in data entry accuracy. Moreover, critical clinical data that could substantially affect the progression of secondary brain injury and treatment effectiveness were unavailable, including transfusion volumes, cause-specific mortality, and the temporal sequence of neurosurgical and abdominal interventions. Without transfusion volume data, we cannot determine whether lower transfusion rates in the TAE group reflect reduced hemorrhage or the selection of less severely injured patients. The lack of data on massive transfusion protocol activation is particularly limiting, as this is an important prognostic indicator. Similarly, without cause-of-death classification, we cannot definitively attribute mortality differences to improved hemorrhage control or other factors. Additionally, although treatment crossover occurred in a small proportion of cases, the analysis used an intention-to-treat approach based on the initial treatment modality, which may not fully reflect the dynamic nature of clinical decision-making. Furthermore, while our inclusion criteria ensured abdominal intervention was performed first or simultaneously with neurosurgical procedures, we cannot determine the exact temporal relationship between these interventions or how this timing affected outcomes.

Third, the study included patients with severe chest trauma (AIS ≥ 3), which may have introduced heterogeneity due to the presence of thoracotomy cases or TAE for intercostal or bronchial artery injuries. In such patients, management priorities often shift toward respiratory and circulatory support in addition to hemorrhage control. Consequently, the choice between TAE and open surgery may be influenced by factors beyond abdominal bleeding, including the severity of chest trauma and the patient’s overall condition.

Fourth, propensity scores were calculated using mixed-effects logistic regression models with institution and injury periods as random effects to account for temporal trends and facility-specific treatment preferences. The SMD for the injury period increased slightly after matching (from 0.106 to 0.119) but remained near the acceptable threshold. In the subgroup analysis, some groups had small sample sizes, warranting cautious interpretation. However, the use of multivariable logistic regression models with double adjustment and pooling across multiple imputed datasets using Rubin’s rules enhanced the statistical robustness of our findings.

Fifth, the primary outcomes focused on short-term endpoints. This is a notable limitation, particularly in patients with TBI, where evaluation of neurological recovery and functional status over time is essential for comprehensive assessment.

Sixth, although we analyzed time from arrival to hemostatic intervention and found no significant difference between groups, we were unable to assess the complete timeline of care, including time to hemorrhage control, delays related to competing priorities, or the effects of simultaneous versus sequential management of TBI and abdominal injuries.

Despite these limitations, our study provides hypothesis-generating evidence that TAE may be associated with lower mortality in selected patients with concurrent TBI and abdominal solid organ injury. The consistency of findings across multiple sensitivity analyses strengthens our observations, although we cannot determine whether the observed associations reflect improved hemorrhage control, reduced physiological stress, or unmeasured confounding. Prospective studies incorporating cause-specific mortality data, detailed transfusion records, and comprehensive neurological outcomes are essential to validate these findings and establish optimal treatment strategies for specific patient subgroups.

In this retrospective cohort study, TAE was associated with lower mortality than open surgery in selected patients with blunt abdominal solid organ injury complicated by TBI, particularly those who were hemodynamically stable, elderly, or had focal TBI. However, these associations should be interpreted cautiously given the study’s limitations, including the absence of cause-specific mortality data and potential residual confounding despite propensity score matching. Open surgery remains the standard of care for hemodynamically unstable patients and those requiring immediate surgical intervention. Treatment decisions should be individualized based on patient hemodynamic status, injury patterns, institutional capabilities, and the availability of experienced interventional radiology teams. Our findings are hypothesis-generating and require validation through prospective studies with detailed clinical outcomes before definitive treatment recommendations can be made.

Methods

Study design and data source

This retrospective cohort study used data from the JTDB for cases registered between January 2004 and December 2019. The JTDB is a national trauma registry established in 2003 by the Japanese Association for the Surgery of Trauma and the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine to improve trauma care in Japan. As of 2025, 319 medical institutions participated in the registry. The database includes 92 variables, such as patient demographics, injury mechanisms, vital signs, symptoms, treatments, and outcomes28.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Saga University Medical School (approval number: 2019-02-迅速-02). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects published by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan.

The requirement for individual informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board of Saga University Medical School due to the retrospective nature of the study and the use of de-identified registry data. Information on JTDB registration is publicly available on the JTDB website and participating hospitals’ websites, and patients may opt out of data registration upon request.

Selection of participants

Eligible cases met all of the following criteria: (1) aged ≥ 15 years with blunt trauma; (2) severe abdominal organ injury (abdominal AIS ≥ 3); (3) severe TBI (head AIS ≥ 3); (4) underwent abdominal computed tomography (CT) during the initial evaluation; (5) received either TAE or open surgery as the initial hemostatic intervention, ensuring that abdominal hemorrhage control was prioritized or performed simultaneously with other procedures; and (6) injury to at least one of the following organs: liver, spleen, or kidney. The restriction to cases with abdominal CT excluded patients who underwent immediate open surgery as part of damage control protocols. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) AIS score of 6 or 9 in any body region; (2) cardiac arrest on arrival or missing SBP and HR data; (3) cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) before or after hospital arrival; (4) concomitant vascular, gastrointestinal, pancreatic, or other abdominal organ injuries; and (5) use of aortic occlusion. Vascular and gastrointestinal injury cases were excluded because these injuries mostly require surgical intervention.

Data collection

From the JTDB, we collected basic patient information, including age, sex, and time of injury (2004–2010 or 2011–2019). For the initial evaluation, we recorded vital signs, including GCS, SBP, HR, respiratory rate, and the presence of shock. To assess injury severity, we collected AIS scores, maximum AIS scores for each body region, ISS, and the number of injured abdominal organs. Regarding injury location, we documented injuries to abdominal organs (liver, spleen, and kidney) and categorized types of head injury (epidural hematoma, subdural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intraparenchymal hemorrhage, cerebral contusion, diffuse axonal injury, cerebral edema, and others). For treatment data, we recorded the initial hemostatic intervention (open surgery or TAE), transfusion within 24 h, and any changes in treatment modality.

Treatment group assignment

Patients were classified based on their initial hemostatic procedure. Those who initially underwent TAE were assigned to the TAE group, regardless of any subsequent conversion to open surgery. Similarly, patients initially treated with open surgery were assigned to the open surgery group, regardless of later TAE. This intention-to-treat approach was adopted to reflect real-world clinical decision-making.

Definitions and outcomes

The severity of TBI and abdominal organ injury was classified using the 1998 AIS codes (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). TBI was categorized by injury pattern into focal, diffuse, and mixed TBI. Cardiac arrest was defined as occurring either before hospital arrival or in the emergency department and included patients who received CPR before transport or presented with SBP of 0 mmHg or HR of 0 bpm. Shock was defined as an SBP of < 90 mmHg.

Any cranial surgery was defined as craniotomy or burr hole surgery performed during the hospital stay. Time from arrival to hemostatic intervention was defined as the time interval in minutes from emergency department arrival to the initiation of the first hemostatic intervention (TAE or laparotomy). Treatment conversion was defined as cases requiring the alternative treatment modality after the initial intervention.

The primary endpoint was in-hospital mortality. Secondary endpoints included early mortality (within 48 h of admission), transfusion within 24 h, and transfusion during hospitalization. Additionally, in-hospital complications were evaluated (Supplementary Table S4).

Sample size calculation

As this was a retrospective observational study that included all eligible cases from 2004 to 2019, an a priori sample size calculation was not performed.

Statistical analysis

Missing data were handled using multiple imputations via the mice package, generating 20 imputed datasets (m = 20, maxit = 50). The “polyreg” method was used for categorical variables, and “cart” for continuous variables. For each of the 20 imputed datasets, propensity scores were estimated using mixed-effects logistic regression models. Covariates included age, sex, ISS, GCS, SBP, number of injured organs, individual organ injuries (liver, spleen, and kidney), and AIS scores for each body region as fixed effects. Institution and injury period (2004–2010 vs. 2011–2019) were included as random effects. Subsequently, 1:1 nearest-neighbor matching was performed with a caliper width of 0.2 for each imputed dataset separately. Matching quality was evaluated using SMDs, with values < 0.1 considered acceptable, and visual inspection of propensity score distributions (Supplementary Fig. S1).

For the outcome analysis, multivariable logistic regression models were fitted to each matched dataset, adjusting for the same covariates used in the propensity score estimation to ensure double adjustment. This double adjustment approach combines the benefits of propensity score matching and covariate adjustment. For each outcome, the analysis was performed separately on each of the 20 matched datasets, and the results were pooled using Rubin’s rules for multiple imputation.

For survival analysis, Cox proportional hazards regression models incorporating all covariates were fitted for each of the 20 matched datasets, and the results were pooled using Rubin’s rules. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated using a representative dataset (the first imputed dataset) for visualization purposes, with statistical significance determined by the pooled Cox regression results when available, or log-rank tests as an alternative.

Subgroup analyses were conducted based on shock status (SBP < 90 vs. ≥90 mmHg), age (≥ 65 vs. <65 years), and TBI type (focal vs. diffuse). For each subgroup within each of the 20 matched datasets, multivariable logistic regression models including the same covariates as the main analysis were fitted. Results were pooled using Rubin’s rules. Cases with mixed TBI features or head injuries that could not be categorized were excluded from the TBI subgroup analysis. Subgroup results were visualized using forest plots.

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.2.3. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Conference presentations

The results of this study were presented at the 52nd Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society of Intensive Care Medicine, held in Fukuoka, Japan, in March 2025.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the Japan Trauma Data Bank, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data, however, can be obtained from the corresponding author (Dr. Mitsuaki Kojima, kojiaccm@tmd.ac.jp) upon reasonable request and with permission from the Japan Trauma Care and Research organization.

Abbreviations

- AIS:

-

Abbreviated injury scale

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CPR:

-

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DCS:

-

Damage-control surgery

- GCS:

-

Glascow coma scale

- HR:

-

heart rate

- ISS:

-

Injury severity score

- JTDB:

-

Japan trauma data bank

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean difference

- TAE:

-

Transcatheter arterial embolization

- TBI:

-

Traumatic brain injury

- TF:

-

Tissue factor

References

Nishijima, D. K., Simel, D. L., Wisner, D. H. & Holmes, J. F. Does this adult patient have a blunt intra-abdominal injury? JAMA 307, 1517–1527 (2012).

Peitzman, A. B. & Richardson, J. D. Surgical treatment of injuries to the solid abdominal organs: a 50-year perspective from the journal of trauma. J. Trauma. 69, 1011–1021 (2010).

Gamanagatti, S., Rangarajan, K., Kumar, A. & Jineesh Blunt abdominal trauma: imaging and intervention. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 44, 321–336 (2015).

Coccolini, F. et al. Liver trauma: WSES 2020 guidelines. World J. Emerg. Surg. 15, 24 (2020).

Coccolini, F. et al. Splenic trauma: WSES classification and guidelines for adult and pediatric patients. World J. Emerg. Surg. 12, 40 (2017).

Suzuki, T., Shiraishi, A., Ito, K. & Otomo, Y. Comparative effectiveness of angioembolization versus open surgery in patients with blunt Splenic injury. Sci. Rep. 14, 8800 (2024).

Banerjee, A. et al. Trauma center variation in Splenic artery embolization and spleen salvage: a multicenter analysis. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 75, 69–74 (2013). discussion 74.

Dehli, T., Bågenholm, A., Trasti, N. C., Monsen, S. A. & Bartnes, K. The treatment of spleen injuries: a retrospective study. Scand. J. Trauma. Resusc. Emerg. Med. 23, 85 (2015).

Sabe, A. A., Claridge, J. A., Rosenblum, D. I., Lie, K. & Malangoni, M. A. The effects of Splenic artery embolization on nonoperative management of blunt Splenic injury: a 16-year experience. J. Trauma. 67, 565–572 (2009).

Melloul, E., Denys, A. & Demartines, N. Management of severe blunt hepatic injury in the era of computed tomography and transarterial embolization: a systematic review and critical appraisal of the literature. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 79, 468–474 (2015).

Roberts, R. & Sheth, R. A. Hepatic trauma. Ann. Transl Med. 9, 1195 (2021).

Hsu, C. P. et al. The effect of transarterial embolization versus nephrectomy on acute kidney injury in blunt renal trauma patients. World J. Urol. 40, 1859–1865 (2022).

McCully, S. P. & Schreiber, M. A. Traumatic brain injury and its effect on coagulopathy. Semin Thromb. Hemost. 39, 896–901 (2013).

Chesnut, R. M. et al. The role of secondary brain injury in determining outcome from severe head injury. J. Trauma. 34, 216–222 (1993).

Wilson, R. F. & Tyburski, J. G. Management of patients with head injuries and multiple other trauma. Neurol. Res. 23, 117–120 (2001).

Oriko, D. O. et al. Multidisciplinary surgical management of concurrent traumatic brain and abdominal injuries: A systematic review of integrated care approaches and clinical outcomes. Cureus 17, e86034 (2025).

Roberts, D. J. et al. History of the innovation of damage control for management of trauma patients: 1902–2016. Ann. Surg. 265, 1034–1044 (2017).

Chaudhry, R., Tiwari, G. L. & Singh, Y. Damage control surgery for abdominal trauma. Med. J. Armed Forces India. 62, 259–262 (2006).

Rotondo, M. F. et al. Damage control’: an approach for improved survival in exsanguinating penetrating abdominal injury. J. Trauma. 35, 375–382 (1993).

Shapiro, M. B., Jenkins, D. H., Schwab, C. W. & Rotondo, M. F. Damage control: collective review. J. Trauma. 49, 969–978 (2000).

Zhang, J., Zhang, F. & Dong, J. F. Coagulopathy induced by traumatic brain injury: systemic manifestation of a localized injury. Blood 131, 2001–2006 (2018).

Maegele, M. et al. Coagulopathy and haemorrhagic progression in traumatic brain injury: advances in mechanisms, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Neurol. 16, 630–647 (2017).

Ivascu, R. et al. The surgical stress response and anesthesia: a narrative review. J. Clin. Med. 13, 3017 (2024).

Mohseni, S., Joseph, B. & Peden, C. J. Mitigating the stress response to improve outcomes for older patients undergoing emergency surgery with the addition of beta-adrenergic Blockade. Eur. J. Trauma. Emerg. Surg. 48, 799–810 (2022).

Podolsky-Gondim, G. G. et al. Traumatic brain injury in the elderly: clinical features, prognostic factors, and outcomes of 133 consecutive surgical patients. Cureus 13, e13587 (2021).

Shen, H., Liu, H., He, J., Wei, L. & Wang, S. Risk factors of prognosis in older patients with severe brain injury after surgical intervention. Eur. J. Med. Res. 28, 479 (2023).

Andriessen, T. M., Jacobs, B. & Vos, P. E. Clinical characteristics and pathophysiological mechanisms of focal and diffuse traumatic brain injury. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 14, 2381–2392 (2010).

Ishii, W., Kandori, K., Miyaguni, M. & HitoSugi, M. Status of use in Japan trauma DataBank, and future developments. J. Jpn Counc. Traffic Sci. 22, 32–37 (2022-2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Japan Trauma Data Bank for providing the data used in this study. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in the study design. T.S., M.K., and A.S. contributed to data collection, data analysis, and manuscript drafting. K.M. critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suzuki, T., Kojima, M., Shiraishi, A. et al. Comparative outcomes of transcatheter arterial embolization versus open surgery for blunt abdominal solid organ injury with concurrent traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep 15, 44898 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29045-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29045-8