Abstract

In this study, Ni-based superalloy Alloy 718 + xTiB2 (x = 1.25; 2.5; 3.75; 5.0%) composites were fabricated by suction casting to improve hardness, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance. The microstructure and properties were analyzed using synchrotron X-ray diffraction, light microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, scanning transmission electron microscopy, dilatometry, differential scanning calorimetry, Vickers hardness, wear resistance measurements, and corrosion tests. The results show that the addition of TiB2 to Alloy 718 has a strong influence on the primary microstructure. All composites are characterized by a dendritic microstructure with irregular distribution of strengthening precipitates. In the reference Alloy 718, the dendritic regions consist of the γ-phase, while interdendritic areas contain Nb-rich carbides and Laves phase precipitates. The TiB2 particles added to a powder mixture reacts strongly with the liquid Alloy 718 during suction casting, resulting in the decrease of the Laves phase and the formation of the M3B2 and M23B6 phases. Increasing the initial TiB2 content shifted the phase transformation temperatures (solidus and liquidus) to lower temperatures. Hardness values increased significantly from 198 HV10 in the reference Alloy 718 to 403 HV10 (5.0% TiB2), which contributed to improved wear resistance. Finally, high temperature exposures in rich oxygen atmosphere (steam) and reduced oxygen atmosphere (Ar + 0.25 vol% SO2) at 704 °C for 1000 h indicated that the Alloy 718 + TiB2 composites were characterized by a lower mass gain than the reference Alloy 718.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The repair of Ni-based superalloy components often requires the integration of welding processes into industrial practice1. Defects in repaired parts caused by foreign object damage, corrosion, and fatigue often have complex geometries that require computerized scanning and robot programming for repair. Manually performing this process using gas tungsten arc welding (GTAW) is therefore a faster and more cost-effective alternative to additive manufacturing techniques such as selective laser melting or laser powder bed fusion2,3. However, a defining feature of GTAW is the use of a wire filler metal, which presents challenges when welding Ni-based superalloys. Ni-based superalloys with a high volume fraction of γ′ precipitates are susceptible to solidification cracking in the weld zone and liquation cracking in the heat affected zone. Although liquation cracking can be reduced by induction preheating prior to welding, solidification cracking remains a major challenge4,5. As a result, filler metals with the same chemical composition as the base metal are generally not recommended for repair. Instead, alloys with lower intermetallic phase and carbide content are preferred as they improve weldability and reduce the risk of cracking during both welding and subsequent heat treatment6. A commonly used filler material for the repair of Ni-based superalloys is Alloy 718 (Inconel 718), which has been used for this purpose for many years7,8,9.

Given the favorable mechanical properties and good weldability of Alloy 718, many researchers have focused on improving its key properties by modifying its chemical composition or adding ceramic particles. The aforementioned reinforcement materials include WC10, TiC11, Cr3C212, h-BN13, and carbon nanotubes14, which are introduced in various forms, including spherical particles, blocks, whiskers, and long fibers. The addition of ceramic particles to weldable Ni-based alloys has the potential to produce metal matrix composites (MMCs) with improved hardness, high temperature stability, and service properties. The improved mechanical performance of MMCs can be attributed to the synergy between the metallic matrix properties, which exhibit excellent ductility and toughness, and the ceramic properties, which impart high strength, hardness and modulus. However, the mechanism of reinforcement by addition of ceramic particles is closely related to the manufacturing process and remains unclear due to the multitude of factors that can influence the resulting microstructure and properties. These factors include the matrix, the type of precipitates (volume fraction, size, morphology, purity), and the fabrication method (method of mixing matrix powders, thermal cycle for composite synthesis, environmental conditions)16,17,18.

A promising phase for reinforcing the matrix is TiB2, which crystallizes in the hexagonal structure (P6/mmm) with lattice parameters a = 3.029 Å and c = 3.229 Å. TiB2 is an excellent reinforcing phase that possesses several outstanding properties: significant strength, high modulus of elasticity (565 GPa), low density (4.5 g/cm3), high melting point (3230 °C), high hardness (2500 HV), and good thermal conductivity19,20. Zhang21 reported that the addition of TiB2 particles could produce crack-free and high performance Hastelloy X. Compared with “pure” Hastelloy X, both the room temperature hardness and the high temperature hardness were increased by approximately 50%, while the yield strength was increased by 28%. Despite the high stability of TiB2, some researchers have observed that the particles can react with a matrix. An extensive study on the wetting of Group IV-VI metal diborides has shown that Ni wets TiB2 under vacuum conditions, forming a contact angle of 62°22,23,24. However, a better wetting behavior in the TiB2-Ni system (θ = 46°) has been reported by Tumanov25. Dissolution of refractory borides and chemical interactions have been found to occur in the TiB2-Ni system, resulting in the formation of the NixB phase and solid solution of boron in nickel. Partial dissolution of the precipitates enriches the matrix with alloying elements, forming secondary phases, as in the Inconel 625/TiB2 composite, where a Ti and Mo enriched transition layer was observed around TiB2 particles26. Strong reactivity between particles and Alloy 718 has also been confirmed for other strengthening phases27.

The fabrication of MMCs always involves some problems, such as reinforcement-matrix interface cracking, uneven reinforcement distribution and segregation at grain boundaries, which can affect the properties of the components28,29. To fabricate ceramic-reinforced MMC coatings, a commonly used technique is to introduce ceramic particles at an optimal mixing ratio into a metal matrix or melt pool prepared directly by an ex-situ process30. Suction casting can be a very promising and effective method for rod fabrication, but a large research gap exists in the utilization of this technique for composites, so a systemic investigation of TiB2 reinforcement of MMCs fabricated by suction casting is necessary. The aim of the present study is to investigate the effect of TiB2 on the as-cast microstructure and selected properties of Alloy718 + TiB2 composites processed by suction casting.

Materials and methodology

The Alloy 718 (Ni-19.8Cr-18.55Fe-5.2Nb-2.98Mo-0.56Al-0.1Si-0.005 C, wt %) and TiB2 powders were used in this study. The Alloy 718 particles were spherical with an average particle diameter of 40–50 μm. Individual TiB2 powder particles have an average size of less than 100 nm. Four mixtures of Alloy 718 powder with the addition of 1.25%, 2.50%, 3.75% or 5.0% (wt %) TiB2 were prepared. Each powder mixture was subjected to mechanical alloying using the Fritsch Pulverisette planetary mixer. The prepared mixtures were weighed again in batches of about 20 g (mass necessary to prepare a single rod φ5 mm x 50 mm) and then synthesized by suction casting using the Arc Melter (Edmund Bühler GmbH). The device is equipped with a copper plate and a suction casting unit, which allows to suck the initially homogenized molten alloy into the two-part casting mold. The material was melted in the main chamber using an electric arc created by a power generator between a non-consumable tungsten electrode (anode) and a copper plate (cathode). The actual casting took place after opening the drain valve. Thanks to the force generated by the pressure difference between the main chamber (60–80 MPa) and the vacuum reservoir (about 0.001 MPa), the material was sucked into the mold in a very short time. The cooling rate of castings using this equipment has been described in detail by Kozieł31. For rods with a diameter of 5 mm, the cooling rate is 100 °C/s. After crystallization, the castings were machined by cutting off the upper and lower parts. Castings prepared in this way were subjected to several tests.

Using chemical composition of Alloy 718 and assumption of complete TiB2 particles dissolution the thermodynamic simulations were carried out to analyze the influence of Alloy 718 enrichment in Ti and B. The Thermo-Calc® software (version 2024b), with the TCNI:10 database, was used to predict primary phases (using the Scheil model) and to characterize the stability of phases in equilibrium conditions.

High-energy synchrotron radiation using beamline P07B at DESY (Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron, Hamburg, Germany) was applied to analyze the Alloy 718 and Alloy 718 + TiB2 nanocomposites. The experiments used high-energy radiation (87.1 keV, λ = 0.01423 nm) and a 2D Mar345 image plate detector for phase analysis and Rietveld refinement32,33.

Microstructural analysis included light microscopy (LM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM). Light microscopy observations were performed using a Leica DM/LM instrument. Quantitative analysis of microporosity was performed on unetched images using ImageJ software.

A ThermoFisher Phenom XL scanning electron microscope with a 20 kV accelerating voltage and a backscattered electron (BSE) detector was used for further observations on electrolytically etched samples in 10% oxalic acid reagent for 5 s. Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX) was used to determine the distribution of selected alloying elements. The partition coefficient ki of the “i” alloying elements was calculated from 20 measurements at different locations according to the relationship:

where: \(\:{\text{C}}_{\text{D}}^{\text{i}}\)-element concentration in the dendrite core (point analysis), \(\:{\text{C}}_{0}^{\text{i}}\)-element concentration in the area with dimensions 53 × 53 μm (area including dendritic cores and interdendritic spaces).

The microstructure of Alloy 718 + 5.0TiB2 composite processed by suction casting was additionally investigated by high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM-HAADF). Lamellae were cut and polished with a Ga + ion beam in a Zeiss Crossbeam 350 FIB-SEM microscope. The lamellae were ion polished to a thickness of 100 nm. Observations were performed with a Cs-corrected FEI Titan Cubed G-2 60–300 probe using a ChemiSTEM system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operating at 300 kV. Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) and atomic resolution images after Fast Fourier Transformation (FFT) were analyzed using JEMS software.

The castings were then subjected to dilatometry to analyze dimensional changes with increasing temperature. The tests were performed using a DIL 806 non-contact optical dilatometer. Cylindrical samples (φ4.5 mm x 20 mm) were heated at a rate of 0.08 ˚C/s up to 1100 °C under nitrogen protection. The linear coefficient of thermal expansion at 20–1100 °C was determined from the dilatometric tests. The coefficient values were calculated with respect to room temperature T0 (2).

where: T0 is the ambient temperature; Tn is the test temperature; l0 is the initial length; ln is the length at test temperature.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed using a Netzsch STA 449F3 Jupiter instrument equipped with a rhodium furnace. The samples were analyzed in disposable Al2O3 crucibles with lids. The test program included heating the sample in argon from room temperature to 1400 °C at a rate of 20 °C /min, isothermal holding for 3 min for thermal homogenization, and then cooling at a rate of 20 °C/min to a temperature of 1000 °C. To characterize the wear resistance of the composites, a dry sliding contact test was performed using the T-05 roller block device. To ensure proper contact between the specimen and the steel ring (100Cr6, 55 HRC, Ø49.5 × 8 mm) rotating at a constant speed, a rectangular specimen (4 × 4 × 20 mm) was fixed in a holder containing a hemispherical insert. The surface of the specimen in contact with the counterpart was perpendicular to the direction of loading. A double lever system was used to push the specimen in the direction of the ring with a load accuracy of ± 1.5%. The rotational speed, load, and sliding distance were 200 rpm, 100 N, and 500 m, respectively. Upon completion of the tests, the specimens were subjected to further microstructural analysis using a scanning electron microscope to analyze the wear mechanism.

Oxidation and hot corrosion tests were performed in steam and Ar + 0.25 vol% SO2 gas mixture, respectively. Samples (φ5 mm x 2 mm) were cleaned in isopropanol using an ultrasonic bath for 15 min at 40 °C. After drying, the samples were carefully weighed using an analytical balance (accuracy 10− 5 g). First, a steam oxidation experiment was performed using the station presented in our previous works34,35. During the experiment, steam was generated by pumping deionized water from a tank placed under the furnace. The entire system was purged with oxygen-free nitrogen (OFN) for at least 2 h prior to the steam oxidation process to remove moisture and atmospheric air remaining in the chamber. The test was conducted at a temperature of 704 °C for 1000 h with interruptions at every 10, 25, 100, 250, 500, 750 and finally 1000 h (mass gain control). The samples were introduced into the hot zone of the furnace using a calibrated stick at a measured distance. After each interval, the samples were cooled to room temperature by turning off the power.

During the test in Ar + 0.25% SO2 atmosphere, a similar sample procedure was used. The test system consisted of a reaction chamber made of 316 austenitic stainless steel, and inside there was a ceramic liner Al2O3-SiO2 was used to avoid reaction of SO2 with a vessel and to avoid reduction of pSO2 and pO2. The furnace, together with the samples, was flushed for 2 h at room temperature with Ar + 0.25% SO2 gas directly from the bottle at a gas flow of 50 ml/min to clean the inner tube, remove moisture and air. The furnace with the sample gas flow was heated at a ramp rate of 5 °C/min to reach the test temperature (704 °C). The procedure for collecting mass gain data was the same as for the steam oxidation test. The exposed materials were subjected to SEM and XRD analysis to study the changes in phase constituents, chemical composition, and the thickness of the scale formed during the 1000 h exposure in steam and in Ar + 0.25% SO2. A Panalytical Empyrean X-ray diffractometer (CuKα=1.5405 Å) was used for X-ray diffractogram collection, and the results were subsequently analyzed using X-pert HighScore software.

Results

Phase composition of Alloy 718 + TiB2 predicted by thermodynamic simulation

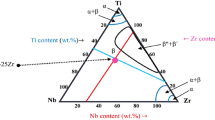

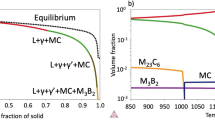

To predict the potential influence of Ti and B on the microstructure of Alloy 718, thermodynamic simulations of the solidification process (Scheil model) and analysis of phase stability at equilibrium conditions were performed. It was assumed that all TiB2 particles dissolve during synthesis and cause a change in the chemical composition of the matrix powder. According to the Scheil solidification simulation of Alloy 718, crystallization begins with the formation of the γ phase, followed by the Laves phase and MC carbides. As a result of chemical composition segregation, an intermetallic δ phase may be formed. The formation of the δ phase may require significant chemical segregation, which is more likely to occur in larger castings that crystallize for longer periods of time. As Ti and B concentrations increase in Alloy 718, the simulation predicts that γ phase, Laves phase, MC carbides and additional B-rich phases (M3B2 and M23B6) may precipitate from the liquid phase.

The phase stability of Alloy 718 with increasing temperature under equilibrium conditions is shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1. In the variants with 1.25% and 2.5% TiB2 additions, the primary strengthening phase under equilibrium conditions is the δ phase, although its volume fraction is lower compared to the reference alloy. However, as the Ti + B content increases to 5.0%, the δ phase becomes unstable and the amount of other stable phases increases. The stability range of the γ’ phase also extends as its fraction increases. This occurs because Ti, along with Ni and Al, contributes to the formation of the γ′ phase. Furthermore, the addition of Ti and B to the chemical composition of Alloy 718 stabilizes two additional B-rich phases, M₃B₂ and M₂₃B₆, under equilibrium conditions. The solvus temperature for M3B2 ranges from 1190 °C to 1210 °C, while for M23B6 it ranges from 789 °C to 939 °C. The absence of the δ phase in the Alloy 718 + 5.0 TiB2 variant may be due to the consumption of niobium by the Laves phase and the borides M3B2 and M23B6. Although the carbon concentration in Alloy 718 powder is relatively low, the presence of strong carbide-forming elements results in the formation of MC carbides. At lower temperatures, these carbides can undergo phase transformation to M23C6 carbides after reaction: MC + γ → M23C6 + γ′. In addition, the phase fractions were evaluated at 704 °C, the temperature at which the corrosion resistance tests were performed. The results indicate that the dissolution of TiB2 precipitates could significantly alter the microstructure, particularly through the precipitation of the M3B2 and M23B6 phases.

Microstructure of alloy 718 + TiB2 nanocomposites processed by suction casting

Figure 2 shows the synchrotron X-ray diffraction results and the corresponding changes in the volume fraction of the γ matrix and strengthening precipitates in the Alloy 718 + TiB2 nanocomposites. In the reference Alloy 718, only the Laves phase and trace amounts of carbides are observed. However, in the variants containing TiB2, additional phases are detected, indicating significant dissolution of the nanoparticles into the molten Alloy 718 during suction casting. When TiB₂ nanoparticles are added in amounts ranging from 1.25 to 3.75%, the formation of M3B2 and TiN phases is observed. At 5.0% TiB2 addition, M23B6 precipitates also appeared, suggesting substantial enrichment of boron in the liquid phase during solidification. Figure 2b represents the changes in the volume fraction of the matrix and strengthening precipitates in the Alloy 718 + TiB2 nanocomposites. In the reference Alloy 718, the volume fraction of Laves phase precipitates is approximately 8.1%, with the rest comprising the matrix. The MC carbide content is too low to be quantified. In the TiB2-modified alloys, there is a gradual increase in the volume fraction of M3B2 borides from 1.1% to approximately 7.2% at 5.0% TiB2. This suggests that boron from the dissolved TiB2 nanoparticles is primarily incorporated into the M3B2 phase. The M23B6 phase is detected only at the highest TiB2 addition, with a volume fraction of about 1%. The increase in boron-rich precipitates is accompanied by a rise in MC/Ti(C, N) precipitates, while a noticeable decrease in Laves phase precipitates is observed. These findings suggest that chemical reactions occurred between Alloy 718 and the TiB2 particles during suction casting, which will be further analyzed in the following sections. Figure 2c illustrates the changes in the lattice parameter of the γ matrix and the MC carbides. The lattice parameter of the γ matrix remains nearly constant regardless of TiB2 content. This stability may suggest that Ti and B originating from the partially dissolved TiB2 nanoparticles are likely incorporated into other phases rather than remaining in a supersaturated γ solid solution. In Alloy 718 + TiB2 nanocomposites, the lattice parameter of the MC carbides gradually decreases from 4.414 Å at 1.25% TiB2 to 4.335 Å at 5.0% TiB2, indicating a variation in the chemical composition of the carbides. Elements such as Ti, Nb, and Mo exhibit a strong affinity for C and are known to form MC carbides in Ni-based superalloys. The M₃B₂ borides possess a tetragonal P4/mbm structure with nominal lattice parameters of a = 5.746 Å and c = 3.036 Å. As the TiB2 content increases, both lattice parameters decrease: at 1.25% TiB2, a = 5.658 Å and c = 3.138 Å, while at 5.0% TiB2 they drop to a = 5.625 Å and c = 3.070 Å. Similar to the MC carbides, this trend indicates a composition change in the borides, which may also affect their stability at high temperature, as suggested by previous ThermoCalc simulation results.

The microstructure of the unetched castings is shown in Fig. 3. Their microporosity is at a very low level, which is related to the characteristics of the suction casting process. In the reference Alloy 718, the microporosity is 0.01% (± 0.001%), while with the increase of TiB2, the microporosity increases slightly to 0.03% (± 0.02%), 0.04% (± 0.02%), 0.04% (± 0.01%) and 0.08% (± 0.02%).

To reveal the distribution of alloying elements in the microstructure of the composites, a semi-quantitative analysis of the chemical composition was performed using SEM-EDX. The partition coefficients ki for the selected elements are presented in Table 2. The values of ki > 1, indicating a higher concentration of the element in the dendritic region of Alloy 718, are observed for Fe, Mo and Al. A coefficient of ki < 1 is obtained for Nb. This MC carbide former tends to segregate strongly in the residual liquid formed during casting solidification. As a result, the interdendritic regions become the preferred site for carbide nucleation and subsequent growth. This can effectively suppress elemental diffusion and trap numerous carbide-forming elements in the interdendritic regions. The values of kNi and kCr, i.e. the γ-phase forming elements, are close to 1, indicating their relatively homogeneous distribution in the microstructure. The kTi coefficient is also around 1, but it is an element that is mainly responsible for the precipitation of carbides and intermetallic phases. In the Alloy 718 + TiB2 nanocomposites, the kNi coefficient is slightly higher with the addition of 1.25% TiB2 and 2.5% TiB2 compared to the reference alloy. Then a decrease to 0.98 and 0.94 is observed for 3.75% TiB2 and 5.0% TiB2, respectively. Simultaneously, there is an increase in the kCr coefficient. The Fe partition coefficient is similar for all variants. The kMo coefficient shows the most pronounced increase, especially in the 5.0% TiB2 variant. The Nb coefficient is also similar to the reference alloy, indicating that it is responsible for the co-creation of precipitates in the interdendritic spaces. There is also a visible change in the Ti distribution. With the addition of TiB2 particles, the kTi values drop significantly below 1, indicating a behavior similar to that of Nb. The recorded changes in the ki coefficients indicate the strong microstructural changes due to the addition of TiB2 particles to Alloy 718.

The amount, distribution and morphology of the strengthening precipitates in the reference Alloy 718 and Alloy 718 + TiB2 nanocomposites are shown in Figs. 3 and 4. All variants are characterized by a dendritic structure with an irregular distribution of strengthening precipitates, which is related to the segregation of alloying elements during powder synthesis. The dendritic regions are characterized by a relatively homogeneous microstructure. SEM observation of the reference Alloy 718 confirmed the presence of fine precipitates of the Laves phase (enriched in Ni and Nb) and MC carbides (enriched in Nb and Ti) (Table 3), which is in agreement with thermodynamic predictions. The Laves phase had a discrete particle morphology or long chain morphology, which is usually related to the solidification conditions36. In the suction casting process, the formation of the Laves phase with complex morphology is difficult due to the very high cooling rate and limited time for coarsening.

In general, the desired microstructure of Alloy 718 with excellent overall properties consists mainly of a matrix γ phase with the intermetallic γ″ (metastable) and γ′ phases. However, other phases are often present in Alloy 718 due to different process parameters such as solidification rate and heat treatment. In suction casting, rapid solidification leads to elemental segregation and eventually to the formation of Laves phase. Sui37 showed that the fine and discrete Laves phases in Alloy 718 hinder the dislocation motion, reduce the stress concentration and increase the toughness. Typically, the Laves phase precipitates are eliminated or reduced by homogenization and solid solution treatments. Qin38 observed that the solution treatment at 950 °C does not eliminate the Laves phases, but makes the long-striped and interconnected Laves phase into fine and discrete structure. As a result of the addition of TiB2, there is a change in the morphology of the precipitates in the interdendritic spaces. At 1.25% TiB2, an increase in the number of bright phase contrast precipitates is observed. The precipitates were subjected to semiquantitative SEM-EDX analysis to characterize their chemical composition (Table 3). The results showed that the Laves phase precipitates (enriched in Ni and Nb) and the MC carbides are still present. The change with respect to the reference Alloy 718 is that in the MC carbides Ti starts to dominate the chemical composition instead of Nb. The value of the partition coefficient of Nb (kNb < 1) indicates that solidification of Alloy 718-based composites starts with the formation of Nb-lean γ dendrites, which leads to the enrichment of the liquid phase in Nb. In the absence of TiB2 addition, Nb is partially bound to the MC phase by carbon. In Alloy 718 + 1.25TiB2, the partial dissolution of the nanoparticles resulted in the enrichment of the liquid with Ti, which is also a strong carbide former. This causes more Nb to be in the liquid phase and can participate in the precipitation of other phases. Cieślak39 stated that the solidification of Alloy 718 (and other Nb-containing superalloys) is dominated by the segregation behavior of Nb and the precipitation of Nb-rich eutectic constituents in the form of γ/Laves and/or γ/MC. As the addition of TiB2 increases to 2.5% and above, the microstructure of the composites changes significantly, resulting in additional Cr, Mo, Nb-rich precipitates with a morphology indicating that they were precipitated during the eutectic transformation. In the interdendritic spaces of the composites with at least 2.5% TiB2, the bright fine precipitates and darker ones with blocky morphology are still present. Based on the SEM-EDX analysis in points no. 6, 9 and 13 of Table 3, only the increased concentration of Ti is observed. In comparison with point no. 3, there is a significant decrease in the concentration of Nb. In addition, in points no. 7, 8, 10, 11 and 12 an increased concentration of Ni and Nb is recorded, which with this alloying element ratio could indicate the presence of the Laves phase. With addition 3.75% TiB2 and 5.0% TiB2 in the areas of precipitates with eutectic-like morphology, elevated concentrations of Cr, Nb and Mo are observed. Locally, in addition to the Ti-rich precipitates with a size of about 2–3 µm, small areas of increased Ti content are visible. They are visible at 5.0% TiB2, which may indicate the presence of very small undissolved TiB2 conglomerates. Due to the very complex microstructure and the size of the precipitates in the interdendritic spaces of the variants with higher amounts of TiB2, additional observations were made with STEM. Alloy 718 + 5.0TiB2 was selected as a representative variant.

The diffraction pattern of the γ matrix does not show any additional diffraction maxima originating from γ″ and/or γ′ phases, which is related to the very high cooling rate (Fig. 5). The matrix crystallizes in a face-centered cubic (FCC) structure. In the heat-treated state (solution and aging), Alloy 718 has high strength at elevated temperature mainly from a stable matrix γ phase with reinforcement from γ″ and γ′ phases precipitating at 600–900°C40.

When TiB2 = 2.5–5.0%, numerous precipitates with lamellar morphology are observed, indicating their formation by eutectic transformation. The morphology of these phases is shown in Fig. 6. ThermoCalc simulations and XRD measurements allowed to confirm that the lamellar precipitates are the M3B2 borides with the tetragonal structure P4/mbm. The elemental distribution in the M3B2 borides was additionally identified by STEM-EDX, are mainly enriched in Cr, Mo, Nb and B. According to the Ni-B binary phase diagram, the solubility of B in Ni is as low as 0.3 at%41. At the same time, the elements of Cr, Mo and B have a high chemical affinity, so the formation of the (Cr, Nb, Mo)-rich borides in Alloy 718 + TiB2 nanocomposites is determined by the insufficient diffusion of B and little movement of Cr, Nb and Mo under the suction casting conditions42. Zhao43 observed in the laser cladding of Alloy 718 + TiB2 that the sufficiently high melted TiB2 particles changed the segregation of alloying elements so that the chain-like Laves phase was modified into network-like M3B2 borides. Miao44 found in cast B-modified Alloy 718 that a low-melting B-bearing phase enriched in Nb, Mo and Cr is observed due to the strong segregation behavior of B in the final residual liquid. Since Alloy 718 is routinely heat treated, the stability of the M3B2 borides during homogenization should be considered. Vernier45 observed that when Alloy 718 was reheated to 1050 °C after subsolvus treatment at 933 °C, the solubility of boron increased both at the grain boundaries and in the bulk. As a result, the material became undersaturated in B and, consequently, the intergranular (Nb, Mo)2CrB2 borides began to dissolve. However, after 2 h at 1050 °C, the residual (Nb, Mo)2CrB2 borides appear stable, indicating that the grain boundaries become supersaturated with boron again after partial dissolution of the precipitates. Zheng46 observed that after HSDA (Homogenization + Solution + Double Aging) treatment, the precipitation of γ′ and γ″ phases decreased with the increase of TiB2 addition. In particular, the γ′ or γ″ strengthening phase of the selectively laser-melted 5% TiB2-added Inconel 718 sample didn’t precipitate due to the considerable non-melted M3B2 precipitates consuming a lot of Nb. Near the M3B2 borides, precipitates with slightly different phase contrast and chemical composition are observed (Fig. 7). These precipitates were subjected to TEM-SAED and FFT analysis, which allowed the confirmation of M23B6 precipitates with FCC structure and nominal lattice parameter a = 10.52 Å. Xie47, based on a study of B-enriched brazing filler metal, reported that B has a higher affinity interaction with Cr than C to form M23C6-like intermetallic phase. In the diffusion-affected zone, B atoms from the molten brazing filler metal could mainly diffuse along grain boundaries and the Cr23B6-like intermetallic phase could be formed. Based on the microstructure analysis of Ni–Cr–Co–W–Mo–B interlayer alloy for Ni-based single crystal superalloy repair, Li48 suggested that the M23B6 phase is formed by eutectic reaction. Ruiz Vargas49 observed M23B6 near the interphase between the base metal and brazed joint and suggested that M23B6 precipitates at the early stage of the isothermal solidification process. Gonzalez50 observed that transition metals react with TiB2 to form MB, M2B and M23B6 metallic borides, which are even harder than titanium diboride. Berns51 found in model Fe–Cr–B–C alloys that the M23B6 phase had the highest carbon solubility compared to all other borides and its hardness was 1100–1600 HV. The presence of M3B2 and M23B6 phases indicates that the TiB2 particles added to the powder mixture are largely dissolved in the liquid during suction casting and, as a result of recrystallization, Ti and B form other types of precipitates.

In the interdendritic spaces, close to the M3B2 borides, there are precipitates with a blocky morphology and an average size around 1–2 μm. Their amount increased with the addition of TiB2 to the powder mixtures. TiB2 and TiN/Ti(N, C) precipitates can have a very similar morphology, which sometimes makes identification difficult. The TEM-SAED pattern is indexed to the FCC structure whose lattice parameter is a = 4.24 Å (Fig. 8). The nitrogen incorporated into Ti(C, N) is primarily introduced as an impurity in the TiB₂ nanoparticles. The strong adhesive interface between Ti(C, N) and the Ni matrix is a clean one without the formation of other precipitates and segregation. In the reference Alloy 718, precipitates with a dominant proportion of Nb and Ti were found, corresponding to MC carbides. Such precipitates were not found in alloys with the addition of 2.5-5.0% TiB2, indicating that C was bound in another phase, most likely Ti(N, C). The formation of similar carbonitrides has also been reported in welding52 and casting of Alloy 71853. Only a few precipitates (Fig. 9) enriched in both Ti and B were observed locally, which could indicate the presence of TiB2, however, it is not a large amount and the results indicate that almost all TiB2 particles were dissolved in the liquid. Zheng46 observed that when 3% TiB2 is melted in Alloy 718, M3B2 borides would be precipitated first during the molten pool solidification process, which has a high melting temperature. Both the formation of high-melting boride and non-melted TiB2 can be used as a support for nucleation. It is found that some TiB2 precipitates can withstand the synthesis and some of the others re-precipitate in the matrix. The amount of TiB2 is much smaller than that of Ti(N, C) due to the above mentioned consideration of B and N interaction with Ti.

Boron from the dissolved TiB2 precipitates was found in M3B2 and M23B6 precipitates, while the Ti concentration also increased. It should be noted that Ti can form different phases in Ni-based alloys. Thermodynamic simulations and microstructural observations show that the addition of Ti to Alloy 718 can promote the precipitation of η phase under certain conditions54. The absence of plate-like η precipitates indicates that titanium was primarily bound in Ti(N, C) precipitates. Considering that the liquid was highly enriched in Ti and B during melting of the powder mixtures, it is worth considering why Ti(N, C) was formed from the liquid instead of TiB2. Since the enthalpy of formation of TiN is − 340.2 kJ/mol, more negative than that of TiB2 (− 281.4 kJ/mol), from a thermodynamic point of view, Ti prefers to react with N rather than B. On the other hand, the radius of the B atom (1.17 Å) is larger than that of the N atom (0.75 Å), so the formation of Ti(B) solid solution is much more difficult than that of Ti(N) solid solution. This conclusion can be further confirmed by the Ti-B and Ti-N phase diagrams, which show that the solubility of B atoms in Ti (much less than that of N atoms in Ti below 1000 °C)55. Therefore, Ti atoms react more readily with N than B atoms. From a thermodynamic point of view, the nucleation ability of phases is influenced by their Gibbs free energies during solidification. TiN has a lower Gibbs free energy than TiC. In addition, Feng56 also showed that the formation energies of TiN and TiC are − 1.94 eV and − 0.90 eV, respectively. TiN has lower formation energy than TiC. Therefore, TiN preferentially nucleates before TiC. There is a small difference in the radii of the C and N atoms, and both TiC and TiN have the FCC structure16. Therefore, the Hume-Rothery condition is satisfied. Thus, TiC and TiN are continuously dissolved, so as the reaction proceeds, a certain amount of C atoms replace N atoms to form Ti(C, N) precipitates. The TEM SAED pattern and FFT image indicate that the fine Nb-rich precipitates in the interdendritic spaces have a hexagonal (P63/mmc) crystal structure with nominal lattice parameters of a = 5.22 Å and c = 8.57 Å (Fig. 10). The detected Laves phase appears to be the product of a non-equilibrium eutectic reaction L→γ + Laves occurring at the end of composite solidification. According to Radhakrishna57, the formation of the Laves phase requires a local niobium concentration of 10–30%.

Influence of the temperature on the stability and phase transformation of Alloy 718 + TiB2 nanocomposites studied by dilatometry and differential scanning calorimetry

Figure 11a shows the dilatometry curves of the Alloy 718 + TiB2 nanocomposites. The samples elongate almost linearly with increasing temperature. Above 400 °C, an increasingly pronounced difference in elongation is observed between the reference Alloy 718 and the Alloy 718 + TiB2 composites. This is most likely due to the increased volume fraction of strengthening phases. Borides, nitrides, carbides and intermetallic phases are characterized by a lower coefficient of thermal expansion than the γ phase58. Therefore, more intensive dissolution of these precipitates (reduction of their fraction) in the matrix may contribute to the increase in strain. In addition, the coefficient of thermal expansion of the γ phase increases more rapidly during heating than that of the strengthening phases. At 1100 °C, the reference Alloy 718 elongates by 1.88%, while with increasing TiB2 addition it decreases by 1.70%, 1.65%, 1.59% and 1.49%, respectively. The coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) was calculated from the measured elongation (Fig. 11b). In general, the CTE of the composites decreases with increasing addition of TiB2, indicating its lower thermal expansion compared to Alloy 718. For heat resistant components, materials with controlled low coefficients of thermal expansion can solve the high temperature problems of thermal stress. The high degree of CTE mismatch between a matrix and its reinforcement is directly related to the degree of residual thermal stress59.

Figure 12 shows the DSC heating curves for the reference Alloy 718 and TiB2 alloyed composites where the main phase transformation temperatures were determined. In addition, the data obtained is summarized in Table 4. When the reference Alloy 718 was heated, a group of related endothermic peaks was observed on the heat flow curve in the temperature range of 1100–1278 °C, which was considered to be the incipient melting of the alloys just before the main endothermic peak caused by the actual melting of the sample. In this group, the first endothermic peak with a maximum temperature at 1186 °C can be related to the dissolution of the Laves phase. A similar endothermic peak in the temperature range of 1162–1190 °C was observed by Cao60 in the differential thermal analysis (DTA) thermograms of the as-cast Alloy 718. The effect was attributed to the Laves phase eutectic reaction. Immediately after the initial melting, the liquefaction of the existing Laves + γ eutectic was reported to increase rapidly with temperature. This phenomenon was responsible for the endothermic process after the Laves peak on the thermograms. The maximum temperature of the next thermal effect, observed at 1260 °C, may correspond to the dissolution of NbC carbides. Melting starts at 1281 °C (beginning of the first deviation from the baseline), while the liquidus temperature is determined at 1362 °C. The melting range of the reference Alloy 718 was therefore 81 °C. The melting enthalpy of Alloy 718, calculated as the area under all visible endothermic peaks on the DSC curve, was approximately 180 J/g. For Alloy 718 + TiB2 composites, a shift in the onset of melting as well as the liquidus to lower temperatures is clearly shown in Fig. 12b. There is also a change in the melting peak geometry which is mostly related to the appearance of two endothermic effects for the variants with 1.25, 2.5 and 3.75% TiB2 addition. At 5.0% addition, one peak is visible again, but this is not an aberration, but the result of further merging of two peaks visible in the previous variants. In each of the composites, a weak peak is visible before reaching 1150 °C, probably due to the dissolution of the Laves phase. During further heating of the composites with 1.25 and 2.5% TiB2 addition, a local melting starts, which is a result of the boride dissolution and the enrichment of the M3B2/γ and M23B6/γ phase boundary with boron. The liquidus temperatures, elaborated as the maximum temperature of the last endothermic peak visible on the DSC heating curve, decreased with increasing TiB2 addition.

Figure 13 shows the recorded exothermic perturbation revealed during liquid cooling of the reference Alloy 718 and composites with different TiB2 additions.

During the cooling of the reference Alloy 718, the start of solidification at 1344 °C was elaborated as the extrapolated onset of the first exothermic peak with its minimum at 1339 °C, while during the further cooling, the second exothermic peak was revealed with an onset at 1160 °C and a minimum at 1156 °C, which is most likely related to the precipitation of the Laves phase. For the Alloy 718 + TiB2 composites, the onset of solidification temperature was shifted to lower values. However, there is a relationship between temperature and TiB2 addition as it decreases to 1308 °C (1.25% TiB2), 1279 °C (2.5% TiB2), 1238 °C (3.75% TiB2) and 1200 °C (5.0% TiB2). Further cooling of Alloy 718 + 1.25 TiB2 resulted in Laves phase precipitation, which is shown on the cooling curve as a second exoteric peak beginning at 1177 °C. The maximum rate of Laves phase precipitation was found at 1159 °C. With the addition of 2.5% TiB2, this peak occurs at almost the same temperature, namely 1159 °C, which, together with the microstructural features characterized earlier, indicates that the range of Laves phase, the formation of M3B2/γ and M23B6/γ eutectics, may occur in a similar temperature range. By increasing the TiB2 addition to 3.75% and 5.0%, a clear split of the exothermic effect occurs. The former, i.e. at a higher temperature, may correspond to M3B2 and Laves phase formation, while the latter may correspond to M23B6 precipitation. After completion of the M3B2/γ and M23B6/γ eutectic transformations, the crystallization process of the composites is complete (liquidus temperature). The liquidus temperature decreases from 1116 °C to 1080 °C with increasing TiB2 addition. Considering the intensive dissolution of TiB2 particles during synthesis and the presence of M3B2 and M23B6 borides in the composites, B-rich phases play the most important role in the location of the phase transformation temperature. Zhao61 observed that M3B2 borides significantly reduced the incipient melting temperature of Ni-based superalloy and influenced the microstructure homogenization during heat treatment. The incipient melting occurred around the M3B2 borides, indicating that the heat treatment temperature was higher than its melting point.

Influence of TiB2 addition on vicker’s hardness and wear resistance of Alloy 718 + TiB2 composites

Microstructure and hardness have a strong influence on the wear resistance of materials (Table 5). The hardness of the reference Alloy 718 is approximately 198 HV10 (± 3 HV10). With the addition of TiB2, the hardness increases to 403 HV10 (± 7 HV10) for 5.0% TiB2, an increase of over 100%. Alloy 718 prepared by selective laser melting has an average microhardness of 277 HV0.2. With the addition of 3% and 5% TiB2, the hardness increases to 538 HV0.2 and 578 HV0.2, respectively46. Zheng46 observed minimal changes in the hardness of TiB2-reinforced samples, probably due to the partial dissolution of M3B2 borides during solution annealing. These borides are very stable, and even partial dissolution requires extended homogenization treatment. Takagi62 showed that Mo1.25 Ni0.25 Cr1.5 B2 borides have a Vickers hardness comparable to NbC carbides, about 2000 HV. Table 4 shows the wear properties of 718 + TiB2 composites processed by suction casting. The reference Alloy 718 shows a mass loss of 0.09% after the test, while the addition of TiB2 significantly improves the wear resistance. With 1.25% TiB2, the mass loss is nearly halved to 0.052%, and further increases in TiB₂ content yield even greater resistance; with 5.0% TiB2, the mass loss is reduced by a factor of four. The wear rate, calculated from sample mass loss, decreases to 0.9 × 10−8 mg/Nm with 5.0% TiB2. The TiB2 modified variants exhibit excellent wear resistance with increasing TiB2 content, which is attributed to the high abrasive and adhesive wear resistance of the M3B2 borides.

In addition to evaluating the material properties under the applied tribological test conditions, it is crucial to study the phenomena occurring at the friction interface, which can be identified by observing the surface morphology after the test. This analysis allows the identification of the frictional mechanisms active during the test. Figure 14 shows typical examples of the post-friction surface morphology for the Alloy 718 + TiB2 composites studied. The wear mechanisms observed on the surfaces after the test vary with the amount of strengthening phases, revealing changes in oxide formation and iron adhesion on the sample surfaces. For the reference alloy and composites with up to 3.75% TiB2, the post-test surfaces are dominated by iron adhesion, which is partially oxidized to form complex iron-rich oxides. Exposed areas of the Ni-rich matrix with fine oxide deposits are also visible. However, in the 5% TiB2 composite, the surface morphology changes, showing primarily nickel and nickel-rich oxide regions, with occasional iron and iron oxide streaks distributed along the wear path, aligned with the direction of rotation of the counterpart. It appears that wear of the friction pair begins with adhesion between the steel matrix regions and the counterpart, resulting in iron transfer to the composite surface. These iron adhesions smear along the surface, bounded by the protruding strengthening phase particles in the interdendritic spaces. Plastic deformation and friction increase the contact temperature, resulting in oxidation of the iron surface, followed by fragmentation of the oxides and their distribution over the surface. Abrasive wear occurs in addition to adhesion and plastic deformation, particularly in the Ni-rich matrix, due to the presence of hard chromium carbide precipitates in the counterpart. As the test duration increases, oxidation intensifies, affecting not only the iron regions but also the Ni-rich matrix. The mechanically weak iron oxides are easily fragmented and distributed over the surface, forming localized clusters of small oxide particles embedded in the iron matrix. In highly plastically deformed iron adhesion regions, fatigue cracks oriented transverse to the friction direction indicate the presence of fatigue wear, particularly in iron transferred from the counterpart. The low roughness observed in the tribological contact area suggests that adhesion and plastic deformation occur smoothly and progressively. In order to quantitatively assess the surface changes, the roughness parameters Rz, Ra and Sa were measured. Each parameter decreases with increasing TiB2 content, which correlates with improved wear resistance. This notable reduction in surface roughness parameters can be attributed to the increased volume fraction of hard, B-rich precipitates. Similar results were reported by Berns51, who observed that increasing the volume fraction of M3B2 and M23B6 borides improved the wear resistance of Fe–Cr–C–B model alloys.

Influence of TiB2 addition on steam oxidation and Ar + 0.25% SO2 gas mixture atmosphere resistance of Alloy 718 + TiB2 nanocomposites

Figure 15a shows the steam oxidation kinetic curves of Alloy 718 and Alloy 718 + TiB2 composites. Mass gain gradually increases with exposure time. In the early stages of oxidation, the mass gain increases rapidly due to the accelerated formation of oxides. The transition from linear to parabolic rate can be related to the thickness of the oxide scale. In the early stages of oxidation, a film is formed where oxidizing species are transported from the ambient atmosphere to the surface, then species must diffuse through the oxide (substrate interface) and react with elements of the matrix. During the initial phase, the transient oxide is formed and is controlled by the diffusion of metal ions to the scale/gas interface or oxygen to the scale/alloy interface. The rate of thickening is determined by temperature, oxygen partial pressure, amount, composition and structure of the initial oxide phases63. As the oxidation time is increased, a slower rate of mass gain is observed due to longer diffusion paths and time. An increase in TiB2 addition from 1.25 to 5.0% results in a reduction in mass gain after 1000 h, as shown in Fig. 15a. The positive effect of TiB2 addition is observed especially when 3.75% TiB2 and 5.0% TiB2 are added. The results are in agreement with the recently published work of Zheng46. According to his work, the addition of at least 3% TiB2 affects the shape and size of a grain. This process enhances the diffusion of elements responsible for high resistance in an oxidizing atmosphere at high temperatures. The higher the TiB2 content, the greater the effect, as the study shows.

In comparison to the steam oxidation process, the exposure of Alloy 718 and Alloy 718 + TiB2 at 704 °C for 1000 h Ar + 0.25% SO2 gas mixture showed (Fig. 15b) a similar effect, the highest TiB2 addition the lowest mass gain, but the mechanism of scale formation is different from that observed in the steam oxidation process. In contrast to steam oxidation, a constant mass gain is observed. In contrast, the mass gain in the steam test was significantly reduced after some time. In the Ar + 0.25% SO2 gas mixture, the activity of pSO2 plays the most important role and is responsible for the constant mass gain instead of the sulfur-rich oxide scale developed. Nevertheless, the lowest mass gain of the exposed specimen was found in Alloy 718 with 5% TiB2 addition, while the specimen with the lowest TiB2 showed almost the highest mass gain, in comparison, unmodified Alloy 718 showed the highest mass gain. To evaluate the oxidation mechanism for a particular material, the n value must be evaluated. In this case, a general equation was used (Eq. 3), where ΔW is the mass gain (mg), A is the initial surface area (cm2), k is the rate constant, t is the oxidation time, and finally n is the time exponent.

A linear law is responsible for characterizing the kinetics of the exposed materials at high temperatures. The oxidation process is controlled by a reaction occurring at the oxide scale-gas and metal-oxide interface and by the oxygen supply from the gas. This oxidation mechanism is independent of the thickness of the oxide layer and the oxide layer is not protective. In contrast, when n = 0.5, the oxide scale develops according to parabolic kinetics, where diffusion is the main controlling process of the oxide scale growth. The parabolic law shows that the ion diffusion process controls the oxidation and depends on the oxide scale thickness. Table 6 shows the n value calculated using the formula given earlier in this paper.

The n values show sub-parabolic behavior below n = 0.5 for all specimens exposed to steam conditions except Alloy 718 with 5% TiB2 addition. The n = 0.56 indicates a nearly parabolic rate of oxide scale growth64. In contrast, specimens exposed to an Ar + 0.25% SO2 gas mixture exhibit n = 1, indicating a linear scale growth rate. These results are consistent with established theory and suggest the formation of weakly protective scales in sulfur-containing atmospheres, where porous scales tend to develop. Scales are thicker after exposure to sulfur-rich environments at high temperatures due to their rapid formation, resulting in greater mass gain as observed in kinetic data65. Furthermore, concerns are often raised about the potential evaporation of Cr-containing compounds in humid environments. However, in this study, no evidence of evaporation was found during a test for both Alloy 718 and Alloy 718 with TiB₂ addition. Young66 recently noted that the evaporation process is largely dependent on the availability of oxygen in the system, which increases with pressure. In this case, with steam at a pressure of 0.1 MPa, the oxygen concentration was insufficient to initiate evaporation.

Figure 16 shows the XRD diffractograms of the samples exposed to steam and Ar + 0.25% SO2 gas mixture atmosphere at 704 °C for 1000 h. In the case of the samples exposed to steam, only Cr2O3 was additionally confirmed as an oxidation product. The presence of Cr2O3 is expected as the Gibbs free energy of formation for Cr2O3 is much lower than that for Fe- or Ni-based oxides; therefore, Cr2O3 can be formed67. On the other hand, the materials exposed in Ar + 0.25% SO2 showed the formation of additional phases: Cr2O3, Ni3S2, Fe3O4, and TiO2. The formation of Ni3S2 is also expected since the atmosphere contains SO2. The formation of scale is mainly attributed to the pO2 - pSO2 ratio. In this work, due to the formation of a large proportion of oxides, pO2 reached a critical level where pSO2 led to the formation of the Ni3S2 phase. The sequence of scale formation is mainly related to Gibbs free energy formation and the activity of an element, a higher the concentration, the higher the activity of an element is observed, in the present case, due to a high concentration and a low Gibbs free energy formation, Cr2O3 forms as the first in Ar + 0.25% SO2 gas, further Fe3O4, and TiO2, the last is Ni3S2 phase, since Gibbs free energy formation is much higher compared to the formed oxides. As mentioned, the formation of Ni3S2 is expected, but due to the low pSO2 in the gas mixture, only this sulfide phase could form. Metal sulfides are generally less stable than the corresponding oxides due to the higher Gibbs free energy. In addition, sulfides have longer bonds and lower energy than oxides. Degradation of the structure is easier in the presence of sulfides than in an oxide. Also, sulfides have a higher number of defects within the crystal structure. Therefore, sulfur diffusion is faster than oxygen, resulting in a higher mass gain of samples exposed to an SO2-containing atmosphere68.

The oxidized Alloy 718 and the composites with TiB2 additions of 1.25% and 2.5% show similar morphological characteristics, with distinct flat and rippled oxidation zones (Fig. 17). However, for the 3.75% and 5.0% TiB2 variants, a slight change in oxide scale morphology is observed, characterized by a transition from flake-like precipitates to granular formations. XRD analysis confirms that the high steam oxidation resistance of the composites is mainly due to the formation of Cr2O3. Cross-sectional microstructural analysis also shows that the oxide layers on the composites exhibit high adhesion. The average oxide layer thicknesses are 1.11 μm (± 0.20 μm) for the reference Alloy and 1.05 μm (± 0.11 μm), 0.96 μm (± 0.14 μm), 0.90 μm (± 0.13 μm) and 0.74 μm (± 0.07 μm) for the four composite variants, respectively. The surface morphology of samples exposed to the Ar + 0.25% SO2 mixture differs significantly from those exposed to steam. Numerous precipitates appear on the surface, ranging from simple geometric blocks to more complex, evolved shapes. The oxide scale on Alloy 718 shows high brittleness and poor adhesion. However, with increasing TiB₂ additions, a gradual improvement in adhesion is observed, probably due to a reduced number of large precipitates on the surface. Only minor, localized spallation is observed in these samples. Based on the XRD results and microstructural analysis, it can be concluded that the rapid formation of a thin Cr2O3 oxide scale is primarily responsible for protecting the composites from excessive degradation by slowing its rate. In contrast to the uniform Cr2O3 layer observed in the steam-exposed samples, the surface of the samples exposed to the Ar + 0.25% SO2 mixture shows Fe3O4, Ni3S2, and TiO2 phases. The Fe3O4 and Ni3S2 phases, which are significantly degraded, show poor adhesion. Microstructural analysis shows that Fe3O4 forms within the Ni3S2 and locally covers it. The formation of Cr- and Fe-rich oxides reduces the oxygen partial pressure while increasing the sulfur partial pressure at the interface between the gas mixture and the composite surface. The oxide formation is attributed to the outward diffusion of Cr and Fe, which react with oxygen. Below the surface there is a region of mixed fine MxOγ and MxSγ phases. Although the surface corrosion products are largely similar, the amount of Fe3O4 and Ni3S2 decreases with increasing TiB2 content. In the Alloy 718 + 3.75% TiB2 and Alloy 718 + 5.0% TiB2 composites (which have the highest resistance), numerous TiO2 precipitates are observed on the surface, which probably contribute to the reduction of Fe3O4 formation.

Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the effect of varying TiB2 contents on the microstructure and selected properties of Alloy 718 + TiB2 composites processed using the suction casting process. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

The Alloy 718 + TiB2 composites are characterized by a dendritic microstructure with irregular distribution of the strengthening precipitates. During the suction casting process the TiB2 particles have been intensively dissolved in the matrix leading to the formation of additional phases Ti(C, )N, M3B2, M23B6.

-

The increase in TiB2 content results in the reduction of the maximum Δl value and, consequently, the linear thermal expansion coefficient. This is related with higher volume fraction of strengthening precipitates characterized by a lower CTE in relation to the matrix.

-

Due to the enrichment of the matrix in the Ti and B, phase transformation temperatures shifted to lower values. During cooling, the liquidus temperature decreased from 1344 °C (for Alloy 718) to 1200 °C (for Allo 718 + 5.0% TiB2). Splitting of the crystallization peak was observed, which attributed to the formation of low-melting B-rich phases.

-

The addition of TiB2 led to increase in hardness (from 198 HV10—Alloy 718 to 403 HV10—Alloy 718 + 5.0% TiB2) and wear resistance. It is linked mostly with presence of hard B-rich phases.

-

During steam oxidation, the Cr2O3 oxide scale was formed on both the reference Alloy 718 and Alloy 718 + TiB2 composites, ensuring high oxidation resistance (mass gain below 0.20 mg/cm2). With TiB2 addition, it gradually decreased to less than 0.10 mg/cm2.

-

After hot corrosion tests in Ar + 0.25% SO2, the mass gain of all composites was higher than during tests in steam. However the addition of TiB2 had a beneficial effect on the corrosion resistance with the mass gain decreasing from 1.76 mg/cm2 (for Alloy 718) to 0.44 mg/cm2 (for Alloy 718 + 5.0% TiB2). Based on XRD measurements, it was shown that the main corrosion products were Fe3O4, Ni3S2 ,and Cr2O3. The amount of Ni3S2 and Fe3O4 decreased with TiB2 addition. In the variants with the addition of 3.75% TiB2 and 5.0% TiB2, numerous TiO2 precipitates were additionally revealed.

Data availability

Related research data is available on demand from the corresponding author lrakoczy@agh.edu.pl.

References

Jeong, H. E., Seo, S. M. & Chun, E. J. Effect of local carbide formation behavior on repair weld liquation cracking susceptibility for long-term-serviced 247LC Superalloy. J. Mat. Res. Technol. 28, 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.12.003 (2024).

Tao, S., Gao, R., Peng, H., Guo, H. & Chen, B. High-reliability repair of single-crystal Ni-base Superalloy by selective electron beam melting. Mat. Des. 224, 111421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2022.111421 (2022).

Wang, D. et al. A laser powder bed fusion–based methodology for repairing damaged nickel-based turbine blades: investigation of interfacial characteristics and hot isostatic pressing treatment. Mat. Char. 212, 113948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2024.113948 (2024).

Liu, S. et al. Insights into process optimization and induction preheating for crack-free laser metal deposition of nickel-based Superalloy K417G. J. Mat. Res. Technol. 29, 2035–2050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.01.266 (2024).

Dmitrieva, A., Mukin, D., Sorokin, I., Stankevich, S. & Klimowa-Korsmik, O. Laser-directed energy deposition of Ni-based superalloys with a high content of γ’-phase using induction heating. Mat. Lett. 353, 135217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2023.135217 (2023).

Mashhuriazar, A. et al. Investigating the effects of repair welding on microstructure, mechanical properties, and corrosion behavior of IN-939 Superalloy. J. Mat. Eng. Perform. 32, 7016–7028. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11665-022-07596-5 (2023).

Jeong, D-H., Choi, M-J., Goto, M., Lee, H-C. & Kim, S. Effect of service exposure on fatigue crack propagation of inconel 718 turbine disc material at elevated temperatures. Mat. Char. 95, 232–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2014.06.022 (2014).

Lech, S., Wusatowska-Sarnek, A., Wieczerzak, K. & Kruk, A. Evolution of microstructure and mechanical properties of ATI 718Plus® Superalloy after graded solution treatment. Metall. Mat. Trans. A. 54, 2011–2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-022-06859-z (2022).

Xu, X. Y. et al. Characterization of residual stresses and microstructural features in an inconel 718 forged compressor disc. Trans. Nonfer Met. China. 29, 569–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1003-6326(19)64965-4 (2019).

He, S., Park, S., Shim, D-S., Yao, C. & Zhang, W-J. Study on microstructure and abrasive behaviors of inconel 718-WC composite coating fabricated by laser directed energy deposition. J. Mat. Res. Technol. 21, 2926–2946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.10.088 (2022).

Sun, X., Ren, X., Qiang, W., Feng, Y. & Zhao, X. Microstructure and properties of inconel 718 matrix composite coatings reinforced with submicron tic particles prepared by laser cladding. Appl. Surf. Sci. 637, 157920. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.157920 (2023).

Khorram, A., Jamaloei, A. D., Paidar, M. & Cao, X. J. Laser cladding of inconel 718 with 75Cr₃C₂+25(80Ni20Cr) powder: statistical modeling and optimization. Surf. Coat. Technol. 378, 124933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2019.124933 (2019).

Kim, S. H. et al. Thermo-mechanical improvement of inconel 718 using ex-situ Boron nitride-reinforced composites processed by laser powder bed fusion. Sci. Rep. 7, 14359. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14713-1 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. Laser powder deposition of carbon nanotube reinforced Nickel-based Superalloy inconel 718. Carbon 107, 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2016.06.014 (2016).

Lemos, G., Fredel, M. C., Pyczak, F. & Tetzlaff, U. Creep resistance improvement of a polycrystalline Ni-based superalloy via tic particles reinforcement. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 854, 143821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2022.143821 (2022).

Mao, X. et al. Nucleation mechanism, particle shape and strengthening behavior of (Ti,Nb)(C,N) particles in Fe-based composite coatings by plasma spray welding. Ceram. Int. 50, 27296–27304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.05.027 (2024).

Junsheng, M. & Zesheng, J. Microstructure and formation mechanism of in-situ TiN-TiB₂/Ni coating by argon Arc cladding. Rare Met. Mater. Eng. 47, 13–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1875-5372(18)30064-X (2018).

Sufiiarov, V., Erutin, D., Borisov, E. & Popovich, A. Selective laser melting of inconel 718/TiC composite: effect of tic particle size. Metals 12, 1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/met12101729 (2022).

Munro, R. G. Material properties of titanium diboride. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 105, 709–720. https://doi.org/10.6028/jres.105.057 (2000).

Zhang, Z. et al. Influence of the TiB₂ content on the processability, microstructure and high-temperature tensile performance of a Ni-based Superalloy by laser powder bed fusion. J. Alloys Compd. 908, 164656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2022.164656 (2022).

Zhang, Z. et al. Laser powder bed fusion of advanced submicrometer TiB₂ reinforced high-performance Ni-based composite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 817, 141416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2021.141416 (2021).

Storozhenko, M., Umanskyi, O., Krasovskyy, V., Antonov, M. & Terentjev, O. Wetting and interfacial behavior in the TiB₂-NiCrBSiC system. J. Alloys Compd. 778, 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.11.102 (2019).

Passerone, A., Muolo, M. L. & Passerone, D. Wetting of group IV diborides by liquid metals. J. Mater. Sci. 41, 5088–5098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-006-0442-8 (2006).

Muolo, M. L., Valenza, F., Sobczak, N. & Passerone, A. Overview on wetting and joining in transition metals diborides. Adv. Sci. Technol. 64, 98–107. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AST.64.98 (2010).

Tumanov, V. I., Gorbunov, A. E. & Kondratenko, G. M. Wetting and properties of group IV and VI metal Mono- and Di-Borides. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. 44, 304 (1970). (in Russian).

Zhang, B., Bi, G., Nai, S., Sun, C. & Wei, J. Microhardness and microstructure evolution of TiB₂ reinforced inconel 625/TiB₂ composite produced by selective laser melting. Opt. Laser Technol. 80, 186–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2016.01.010 (2016).

Lu, S., Zhou, J., Wang, L. & Liang, J. Influence of MoSi₂ on the microstructure and elevated-temperature wear properties of inconel 718 coating fabricated by laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 424, 127665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2021.127665 (2021).

Gawdzińska, K., Nagolska, D. & Szweycer, M. Classification of structure defects of metal matrix castings with saturated reinforcement. Arch. Found. Eng. 12, 29–36. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10266-012-0077-y (2012).

Zhang, T. et al. Effect of hybrid ultrasonic-electromagnetic field on cracks and microstructure of inconel 718/60%WC composites coating fabricated by laser cladding. Ceram. Int. 48, 33901–33913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.07.339 (2022).

Graboś, A. et al. Thermal properties of inconel 625-NbC metal matrix composites (MMC). Mater. Des. 224, 111399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2022.111399 (2022).

Kozieł, T., Pajor, K. & Gondek, Ł. Cooling rate evaluation during solidification in the Suction casting process. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 9, 13502–13508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.09.082 (2020).

Chulist, R. et al. Adaptive phase or variant formation at the Austenite/Twinned martensite interface in modulated Ni–Mn–Ga martensite. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2307322. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202307322 (2024).

Szewczyk, A., Wójcik, A., Maziarz, W., Schell, N. & Chulist, R. Structural differences between single crystalline and polycrystalline NiMnGa-based alloys. Mater. Charact. 222, 114850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2025.114850 (2025).

Dudziak, T. et al. Phase investigations under steam oxidation process at 800°C for 1000 h of advanced steels and Ni-based alloys. Oxid. Met. 87, 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11085-016-9662-8 (2017).

Dudziak, T. et al. Neural network modelling studies of steam oxidised kinetic behaviour of advanced steels and Ni-based alloys at 800°C for 3000 h. Corros. Sci. 133, 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2018.01.013 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. Study on the element segregation and Laves phase formation in the laser metal deposited IN718 Superalloy by flat top laser and Gaussian distribution laser. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 754, 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2019.03.096 (2019).

Sui, S. et al. The influence of Laves phases on the room temperature tensile properties of inconel 718 fabricated by powder feeding laser additive manufacturing. Acta Mater. 164, 413–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2018.10.032 (2019).

Qin, L. et al. Microstructure, high-temperature Cyclic oxidation, and hot corrosion behaviors of inconel 718 alloy produced by laser-induction hybrid cladding. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 32, 550–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.07.200 (2024).

Cieslak, M. J., Knorovsky, A., Headley, T. J. & Romig, A. D. The solidification metallurgy of Alloy 718 and other Nb-containing superalloys. In Superalloy 718 - Metallurgy and Applications: The Minerals, Metals and Materials Society, 59–68 (1989).

Cao, M. et al. The effect of homogenization temperature on the microstructure and high-temperature mechanical performance of SLM-fabricated IN718 alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 801, 140427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2020.140427 (2021).

Teppa, O. & Taskinen, P. Thermodynamic assessment of Ni–B phase diagram. Mater. Sci. Technol. 9, 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1179/mst.1993.9.3.205 (1993).

Theska, F. et al. Review of microstructure–mechanical property relationships in cast and wrought Ni-based superalloys with boron, carbon, and zirconium microalloying additions. Adv. Eng. Mater. 25, 2201514. https://doi.org/10.1002/adem.202201514 (2023).

Zhao, M. et al. Laser powder bed fusion of inconel 718-based composites: effect of TiB₂ content on microstructure and mechanical performance. Opt. Laser Technol. 167, 109596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2023.109596 (2023).

Miao, Z-J. et al. Effects of P and B addition on as-cast microstructure and homogenization parameter of inconel 718 alloy. Trans. Nonferr Met. Soc. China. 22, 318–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1003-6326(11)61177-1 (2012).

Vernier, S., Pugliara, A., Viguier, B., Andrieu, E. & Laffont, L. Solid-state phase transformations involving (Nb,Mo)₂CrB₂ borides and (Nb,Ti)₂CS carbosulfides at the grain boundaries of Superalloy inconel 718. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 51, 6607–6629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-020-06045-z (2020).

Zheng, Y. et al. The microstructure evolution and precipitation behavior of TiB₂/Inconel 718 composites manufactured by selective laser melting. J. Manuf. Process. 79, 510–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmapro.2022.04.070 (2022).

Xie, C. et al. Microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of Ni-based Superalloy joints brazed using a ternary Ni-W-B amorphous brazing filler metal. J. Alloys Compd. 960, 170663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.170663 (2023).

Li, W. et al. Study of Ni-Cr-Co-W-Mo-B interlayer alloy and its bonding behavior for a Ni-base single crystal Superalloy. Scr. Mater. 48, 1283–1288. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6462(03)00045-9 (2003).

Ruiz-Vargas, J. Étude des mécanismes de formation des microstructures lors du brasage isotherme de superalliages à base de nickel. PhD thesis, Université Lorraine (In French). (2014).

Gonzalez, R. et al. New binder phases for the consolidation of TiB₂ hardmetals. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 216, 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/0921-5093(96)10408-1 (1996).

Berns, H. & Fischer, A. Abrasive wear resistance and microstructure of Fe-Cr-C-B hard surfacing weld deposits. Wear 112, 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/0043-1648(86)90238-3 (1986).

Orr, M. R. Solidification cracking performance and metallurgical analysis of filler metal 82. MS thesis, The Ohio State University (2016).

Chen, X. et al. Investigation of oxide inclusions and primary carbonitrides in inconel 718 Superalloy refined through electroslag remelting process. Metall. Mater. Trans. B. 43, 1596–1606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11663-012-9723-6 (2012).

Cheng, H. W., Tang, Y. L. & Wang, M. Q. Growth mechanisms of Eta phase in 718Plus alloy. Mater. Today Commun. 38, 108452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2024.108452 (2024).

Qiu, L. X. et al. Characterization of structure and properties of TiN–TiB₂ nano-composite prepared by ball milling and high pressure heat treatment. J. Alloys Compd. 456, 436–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2007.02.052 (2008).

Feng, W. X., Cui, S. X., Hu, H. Q., Zhang, G. & Lv, Z. Electronic structure and elastic constants of TiCₓN₁₋ₓ, ZrₓNb₁₋ₓC and HfCₓN₁₋ₓ alloys: A first-principles study. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 406, 3631–3635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physb.2011.06.058 (2011).

Radhakrishna, C. & Prasad Rao, K. The formation and control of Laves phase in Superalloy 718 welds. J. Mater. Sci. 32, 1977–1984. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018541915113 (1997).

Karunaratne, M., Kyaw, S., Jones, A., Morell, R. & Thomson, R. Modelling the coefficient of thermal expansion in Ni-based superalloys and bond coatings. J. Mater. Sci. 51, 4213–4226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-015-9554-3 (2016).

Mandal, V., Tripathi, P., Kumar, A., Singh, S. & Ramkumar, J. A study on selective laser melting (SLM) of tic and B₄C reinforced IN718 metal matrix composites (MMCs). J. Alloys Compd. 901, 163527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.163527 (2022).

Cao, W. D., Kennedy, R. L. & Willis, M. P. Differential thermal analysis (DTA) study of homogenization process in Alloy 718. In Proceedings of the Superalloys 718, 625 and Various Derivatives, 147–160 (1991).

Zhao, Y. et al. Influence of minor Boron on the microstructures of a second-generation Ni-based single-crystal Superalloy. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 28, 483–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnsc.2018.06.001 (2018).

Takagi, K., Koike, W., Momozawa, A. & Fujima, T. Effects of cr on the properties of Mo₂NiB₂ ternary boride. Solid State Sci. 14, 1643–1647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2012.05.009 (2012).

Danielewski, M., Filipek, R., Pawełkiewicz, M., Klassek, D. & Kurzydłowski, K. Modelling of oxidation of Fe-Ni-Cr alloys. Defect Diffus. Forum. 237–240, 958–964. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/DDF.237-240.958 (2005).

Welch, N. J., Quintana, M. J., Butler, T. M. & Collins, P. C. High-temperature oxidation behavior of TaTiCr, Ta₄Ti₃Cr, Ta₂TiCr, and Ta₄TiCr₃ concentrated refractory alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 941, 169000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.169000 (2023).

Gesmundo, F., Young, D. H. & Roy, S. K. The high-temperature corrosion of metals in sulfidizing-oxidizing environments: A critical review. High. Temp. Mater. Process. 8, 149–190. https://doi.org/10.1515/HTMP.1989.8.3.149 (1989).

Young, D. J. & Pint, B. A. Chromium volatilization rates from Cr₂O₃ scales into flowing gases containing water vapor. Oxid. Met. 66, 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11085-006-9030-1 (2006).

Ellingham, H. J. T. Reducibility of oxides and sulphides in metallurgical processes. J. Soc. Chem. Ind. 63, 125–133 (1944).

Mrowec, S. On the defect structure and diffusion kinetics in transition metal sulphides and oxides. React. Solids. 5, 241–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-7336(88)80025-1 (1988).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding by National Centre for Research and Development, Poland, under grant LIDER XIII—Development of the manufacturing and deposition technology of metal-ceramic nanocomposite coatings for the structural reconstruction of heat-resistant nickel-based superalloys (Project no. 0036/L-13/2022). ŁR acknowledges the contribution of European Ceramic Society (ECerS) in supporting the collaboration between AGH University of Kraków and FunGlass—Centre for Functional and Surface Functionalized Glass (Alexander Dubček University of Trenčín) within JECS Trust Mobility Program (Contract number: 2023 385).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ł.R.—conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, project administration, funding acquisition, software, data curation. M.G.R.—investigation, review and text editing. G.C.—investigation. T.K.—investigation, review and text editing. E.R.—investigation. M.M.—investigation, review and text editing. A.K.—investigation, review and text editing. T.D.—investigation, review and text editing. D.K.—investigation. R.C.—supervision, investigation. R.Ch.—investigation. D.G.—supervision, investigation, review and text editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rakoczy, Ł., Grudzień-Rakoczy, M., Cempura, G. et al. Microstructure, phase transformation temperatures and long-term stability of ex-situ Alloy 718 + TiB2 metal-ceramic nanocomposites as a repair coatings for aerospace applications. Sci Rep 16, 95 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29049-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29049-4