Abstract

Over 30,000 hazardous material pipeline (HMP) failures have caused nearly $11 billion in damages since 1970. Tropical cyclones, which cause more infrastructure damage than all other forms of natural disasters combined, are thought to be under-attributed causes of HMP failures, largely due to historic policy around pipeline failure reporting. This study defines tropical cyclone-associated HMP failure frequency based on spatiotemporal concomitance, while detrending for background HMP failure rates, and explores the relationship between the likelihood and frequency of HMP failures and tropical cyclone intensity using a method that accounts for omitted variable bias associated with unparameterized storm and pipeline characteristics. Though only 4.3% of HMP failures have been formally linked to natural forcings, 32.5% of HMP failures in the eastern United States occur within 60 days of a tropical cyclone. HMP failures 60 days after a tropical cyclone intersection are both significantly more likely, and exponentially more frequent, with increasing tropical cyclone intensity. Since 1975, the annual frequency of tropical cyclone-associated pipeline failures has increased by an order of magnitude. During this same period, the annual lifetime maximum intensity of a tropical cyclone intersecting with HMP infrastructure has increased from a Category 3 to a Category 4 storm on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane scale. Implications for pipeline design, and of accurate natural hazards-related cause attribution on HMP failure incident reports, are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The United States’ onshore hazardous material pipeline (HMP) network, spanning over 3.3 million miles, is a critical component of the nation’s energy infrastructure. The majority of petroleum products used in the United States are transported through the HMP network. National dependence on HMPs has driven a nearly 14% expansion of pipeline in the past eight years1 with an almost 30 million barrels per day increase in HMP transport projected by 20402. Despite the benefits of HMP infrastructure, HMP infrastructure failures, which cause unintended discharge of petroleum products into the environment, are associated with devastating economic, environmental, and social costs3,4. Over 30,000 HMP failures have been reported in the United States since 1970. Between 2005–2023, reported HMP failures were associated with 274 fatalities, 1120 injuries, and nearly $11 billion in damages5. Between 28–95% of the total costs of pipeline failures are associated with environmental damage and remediation6,7, yet even with the large price tag, about 85% of petroleum products released during HMP failures remain unrecovered after remediation6,8, leading to long-term ecological and public health impacts.

In 1968, the Pipeline Safety Act mandated and outlined the requirements for reporting hazardous material pipeline (HMP) failures5,9,10. This regulation requires pipeline operators to report HMP failures within 30 days of occurrence, providing accident-specific details such as location, facilities involved, operations, personnel conduct, and the cause of the incident. When reporting HMP failure cause, pipeline operators have historically selected a single cause from pre-defined categories, including corrosion, excavation damage, external forces, material or weld failures, equipment malfunctions, and incorrect operation. “Natural forces” was added as a causal category on HMP incidence reporting forms for the first time in 2002 (Text S1). In reality, HMP failures frequently result from the interaction of multiple contributing factors. For example natural force failures are more likely when there is underlying corrosion. Single-category cause attribution requirements in mandated reporting therefore limits analysis of complex or interacting drivers of HMP failures11,12,13.

Though estimates vary widely, meteorological events, specifically tropical storms and hurricanes (tropical cyclones, TCs, powerful, rotating, meso-to-synoptic scale weather systems that form over warm ocean waters and brings strong winds and tornadoes, heavy rain, and potentially dangerous storm surges to terrestrial landmasses), are understood to contribute significantly to total damages associated with natural-hazard triggered pipeline accidents in the United States14, and have been estimated to be the cause of up to 86% of all natural-hazard mediated pipeline failures worldwide12. While the true magnitude of natural-hazard-associated pipeline failures in the United States is difficult to estimate due to reporting bias15, TCs are broadly understood to be an important, and under-characterized, driver of HMP failures12,15.

As average ocean temperatures across the Atlantic Basin continue to increase due to climate change16,17,18, the strongest TCs, which are fueled by warm ocean temperatures, have increased in intensity19,20,21. Previous research shows that the most damaging tropical cyclones—Category 3 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale—are responsible for approximately 85% of the total TC damages, even though they constitute 24% of landfalling storms22. These extreme events are particularly challenging to simulate accurately in gridded climate models (e.g.23), leading to inconclusive findings in numerical studies on how multidecadal climate variability, including anthropogenic climate change, will impact the most powerful TCs. However, historical data indicates a significant increase in the proportion and strength of high-intensity (Category 3 or higher) storms in particular as a result of climate change (Text S6,19,20,24).

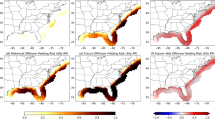

Regulatory bodies across the world target HMP design standards on building network resilience to natural disasters, such as earthquakes in California25 and tsunamis in Japan26. TC storm tracks impact 19 US states, overlapping with some of the densest HMP infrastructure in North America (Fig. 1a,5). Designing for TCs is challenging because TCs can stress pipeline systems through a variety of mechanisms, including but not limited to: mechanical stress from high wind speeds; intense precipitation and related impacts including compound flooding; shifting and settling of rapidly saturated soils; erosion, accretion, and landslides; storm surges and related coastal impacts; and intensified tornado activity inland27,28,29. Some of these stresses are acute, and can logically be associated with pipeline failure at low latency. For example, TC-associated tornado damage to an above-ground transmission pipeline is easily attributable to an individual storm event10,30. Many of these stresses are cumulative and can result in a decreased overall lifetime of the pipe system. For instance, a pipeline network subject to frequent bouts of wetting and drying due to TC-related precipitation in regions with high shrink-swell potential could undergo significant mechanical stress31,32; and pipelines impacted by saline storm surges coastally could experience more rapid rates of corrosion over time33,34. While impacts of high wind speeds and intense rainfall are universal, TCs interact with local soils, land cover, topography, and microclimate to generate different impacts on infrastructure in different regions of the United States. Coastal regions (Texas Coast, Mississippi Delta, Southeast Coast) will experience effects of storm surges35,36; flat regions (High Plains, Southeast Coast, Midwest) may see tornado activity36,37; hilly regions (Northeast) may see compounding flooding, including coastal, riverine, and flash flooding and landslides38,39; and the High Plains, Texas, and Mississippi Delta region will likely be additionally impacted by high shrink-swell potential of local soils saturated with intense rain over large geographic reaches40,41.

When it comes to determining the nature of the impacts of TCs on HMP infrastructure, we are limited by data availability on both response (i.e. we do not know which HMP failures are associated with TCs) and response (i.e. we lack historical observations of many TC associated-impacts, such as precipitation intensity and storm surge height, that could impact infrastructure). From the forcing side, in the United States we are fortunate to have high-quality historical observations of hurricane minimum pressure and maximum sustained windspeed from aircraft reconnaissance since the mid-1940s, but observation networks required for coastal storm surge and precipitation intensity monitoring where not available until the late 1990s42, and our ability to monitor TC associated tornadoes is still quite limited43.

To inform dialogue on engineering standards for HMP failure reporting, design, and maintenance in hurricane-prone regions in the \(21^{\text {st}}\) century, the objective of this study is to quantify associations between trends in HMP failure frequencies and observed increases in TC intensity (TCI, defined here as the first principal component of maximum sustained near-surface windspeed and minimum sea-level pressure due to historical bias trends in windspeed42) associated with climate change. As there are no historical records of TC associated storm failures available through the PHMSA, we identify HMP failures that have occurred within 60 days of exposure to TCs (\(f_s\)). As this number will include both failures related to the TC and background failures that would have occurred anyway, we also calculate the local five-year average 60-day HMP failure rate unassociated with TCs (\(f_o\)). The local background failure rate (\(f_o\)) changes over time, specifically over a five year window. We then define storm related failure frequency as \(f_s'\) =\(f_s\) -\(f_o\). TC-related HMP failure frequency (\(f_s'\)) is therefore detrended for any local trends in background HMP failure frequency associated with infrastructure evolution (e.g. increasing pipe age and network length over time).

Using a panel modeling framework that can control for, and quantify the relative importance of, parameterized spatiotemporal drivers of HMP failure (such as impacts of precipitation, tornadoes, and storm surges, which we lack historic data for; as well as spatiotemporal variability in pipeline resilience to TCs associated with infrastructure characteristics), we estimate the extent to which increases in TCI observed in the last 50 years are associated with increased TC-related failure frequencies (Text S2 and S3, Fig. 1b) during the same time period44. We observe that HMP failures become significantly more likely, and exponentially more frequent, as a function of increasing TCI. We confirm conclusions from the literature12,13,14,36,36 suggesting that the lifetime maximum intensity of the average annual maximum storm intersecting with HMP infrastructure has increased from a Category 3 storm on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale in 1970 to a Category 4 in 2010. To estimate the upper limit of HMP failure risk associated with TCs, in the absence of robust numerical models, we resort to extrapolating from this trend to assume a linear increase in TCI associated with increasing sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic up until 2050, when regional SSTs are projected to reach the \(26.5^{\circ }\) C threshold after which thermodynamic intensification of TCs is expected to “saturate” and break from linear trends45. Assuming near-term continuation of observed linear trends implies that the average annual maximum storm intersecting with HMP infrastructure could be a Category 5 by 2050 (Text S6). These results underscore the significance of meaningful design interventions to stabilize HMPs in TC regions, and suggest that TCs and associated impacts need to be considered as contributing causes of HMP failure on incidence reporting forms for accurate attribution.

Results

Pipeline failure attribution analysis

Between 1986 and 2022, pipeline failures in the PHMSA dataset were categorized as resulting from natural forces (4.3%, or 275 failures), human error (14.9%, or 943 failures), and external forces (80.8%, or 5124 failures). The first recorded pipeline failure attributed to “natural forces” appeared in 2002 when the category was introduced, with no significant positive or negative trends in the frequency of this attribution observed since then (Figure S1). In contrast, significant (\(p < 0.01\)) positive trends were noted in the annual frequency of failures attributed to human error (an increase of 1.33 failures per year) and external forces (an increase of 1.45 failures per year) over the same period (Figure S1). Spatiotemporal characteristics of pipeline network infrastructure, including, but not limited to, the total length of pipeline in a region, the rate at which regional pipeline networks are expanding, and aging pipe, will influence current and future regional baseline and HMP failure frequencies. To account for regional differences in HMP network infrastructure, as well as regional differences in TC dynamics (due to historically unmeasured phenomenon such as precipitation, tornadoes, storm surges, etc), we divided the study area into six spatial subregions using K-means clustering on latitude and longitude (Fig. 1a, Text S1). In all models, we set random intercepts to these location groups, as well as to individual years, to quantify and control for spatiotemporal omitted variable bias which we hypothesize will be associated with these unmeasured storm and infrastructure parameters.

Although PHMSA reports attribute a relatively low percentage of pipeline failures to “natural forces,” our analysis found that 32.5% of HMP failures in the TC intersecting region occur within 60 days of TC exposure (Figure S2), which serves as our temporal cutoff point for a TC-associated HMP failure (Text S1). Over the study period, we observed a significant positive linear trend in the annual frequency of failures occurring within 60 days of TC exposure (the regional TC-associated failure frequency, or \(f_s\), Eq. 1). Drawing from this trend, in 1975, the annual mean \(f_s\) in the Eastern United States was 4 TC associated failures; by 2020, this number had risen to 50 failures per year (Figure S3, S4). As trends in \(f_s\) will be associated with both failures related to TC, as well background failures that would have occurred regardless of TC exposure, we also quantify the local, time-dependent background failure frequency (\(f_o\) , Eq. 2, Fig. 1b), and define the TC-related failure frequency (\(f_s'\)), as \(f_s\) minus the time-dependent regional 60-day background failure frequency (\(f_o\), Eq. 3, Fig. 1b).

(a) Six spatial sub-regions where HMP infrastructure (major crude oil and natural gas transmission pipelines,46) intersect with tropical cyclone storm tracks (TCs) in the continental United States (47 OpenStreetMap © 2024). (b) Time series of \(f_s\) (points) and \(f_o\) (lines) by spatial region. The height of points above the grey polygon represents storm-related HMP failures, or \(f_s'\). (c) For each spatial sub-region, the table indicates total 1970–2022 \(f_s'\), maximum TC windspeed, length of crude oil pipeline, and length of natural gas pipeline. Here “MS Delta” refers to “Mississippi Delta”.

The highest total number of TC-related HMP failures (\(f_s'\)) were observed on the Texas coast, followed by the Mississippi Delta and Northeast regions; where high-magnitude TCs (indicated by wind speed) intersect with dense crude and natural gas pipelines (Fig. 1c). More frequent \(f_s'\) are observed in the second half of the study period relative to the first in the Mississippi Delta and Texas coast, indicative of a trend in these regions (Fig. 1b). Higher pipeline failure per unit length of crude oil pipeline is observed in the Northeast than other regions (Fig. 1c). High magnitude \(f_s'\) is observed in High Plains, despite lower maximum TC wind speed (Fig. 1b,c). The Southeast returns few \(f_s'\) relative to high TC wind speeds, likely because of a lack of crude oil pipeline infrastructure in the region (Fig. 1c).

To evaluate whether the intensity of TCs modifies the likelihood of at least one HMP failure while controlling for omitted variable bias, we utilized a mixed-effects logistic regression model predicting the likelihood of at least one \(f_s'\) per region for a storm, with random intercepts on region and year. TC intensity (or TCI, calculated as the first principal component of the maximum sustained near-surface windspeed and minimum sea-level pressure of all storm HURDAT2 points intersecting with with a spatial subregion) is a statistically significant predictor of one or more TC-related HMP failures for that given region (at \(\alpha\)=0.05), with the likelihood of one or more failure increasing by 46% for a standard deviation increase in TCI (Text S7, Figure S6a). This indicates that with a TCI of zero, approximately equal to the interface between a tropical cyclone and Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane scale, the probability of at least on HMP failure is about 20%. According to this model, the probability of at least one failure increases to 31% for a Category 2 storm, 38% for a Category 3 storm, 49% for a Category 4 storm, and 64% for a Category 5 storm. TCI explains minimal inter-annual variance (\(v\)) in the likelihood of one or more HMP failure (0.2%), but explains 21.8% of the regional variance (\(u\)) in the likelihood of one or more HMP failures during a TC (Figure S6b,c), suggesting that about 22% of the spatial variability in the likelihood of at least one HMP failure per storm is explained by TCI, with the remaining 78% being associated with unmeasured regional storm impacts and their interactions with local pipeline characteristics. The overall likelihood of TC-related HMP failure is higher in the Mississippi Delta, Texas Coast, and Northeast region (Figure S6b), and TCI explains more of this increased likelihood in the Mississippi Delta and Texas Coast, suggesting that other TC impacts, such as precipitation, may be more regionally impactful in the Northeast.

Nested mixed-effects Poisson regression models characterize how TCI modifies the frequency of pipeline failures, while controlling for spatiotemporal non-independence in the data with random intercepts on year and location. TCI is a statistically significant (at \(\alpha < 0.001\)) predictor of increased frequency of pipeline failures \(f_s'\), with an incidence rate ratio of 1.54 averaged across the regions. If we look at how this translates to \(f_s'\) along the Texas Coast, for example, this suggests that a Category 1 storm will be associated with approximately 5 TC-associated HMP failures (\(f_s'\)). This increases to 9 \(f_s'\) for a Category 2 storm; 15 \(f_s'\) for a Category 3 storm; 28 \(f_s'\) for a Category 4 storm; and 63 \(f_s'\) for a Category 5 storm. In the null model, inter-annual variance in \(f_s'\) (\(v\)) was 141% greater than regional variance (\(u\)) implying that inter-annual variability in \(f_s'\) for a given location is greater than regional variability in \(f_s'\) within a given year. Adding TCI explains 24% of variance in \(f_s'\) for location (\(u\)) and 34% of residual variance in \(f_s'\) for year (\(v\)), suggesting that many \(f_s'\) occur do to other regional or time-varying characteristics of TC presentation, and cannot be explained by TCI alone (Fig. 2a, Text S8).

In the null model, \(u_j\) and \(v_k\) indicate anomalies in \(f_s'\) from year to year and location to location. Shifts in \(u_j\) and \(v_k\) between a null model (no fixed effects) and the full model (containing TCI as a fixed effect) indicate inter-regional and inter-annual variability in how \(f_s'\) responds to TCI (Fig. 2b,c). In the null model, the highest \(u_j\), corresponding to the highest regional average regional \(f_s'\), is observed along the Texas Coast, followed by the Mississippi Delta and the High Plains. The lowest \(u_j\), corresponding the lowest \(f_s'\) for a region, are observed in the Southeast and in the Midwest. Negative shifts in \(u_j\) in the Texas Coast and Mississippi Delta with TCI parameterized suggests that a substantial portion of the high \(f_s'\) observed in this region is explained by increased TCI. A positive shift in \(u_j\) in the High Plains suggests that the global coefficient on TCI may lead to an underestimation of TC-related pipeline failures (\(f_s'\)) for low-intensity TCs, which most frequently present in the region (Fig. 1c). A positive shift in the negative \(u_j\) in the Midwest suggests that lower \(f_s'\) in the region is partially explained explained by lower TCI in the Midwest, relative to other regions (Fig. 2b).

(a) Mixed-effects Poisson model parameters and statistics for null (no fixed effects) and full (TCI as a fixed effect) models, (b) caterpillar plot of random intercept (points) on location for null (open circles) and full (closed circles) models, with error bar representing 95% confidence interval; color scale indicating location group (c) as in (b) but for random intercept on year, with color scale indicating advancing year. Here, “MI Delta” refers to “Mississippi Delta”.

The random intercept on year (\(v_k\)) in the null model likewise indicates the relative anomaly in \(f_s'\) for a given year. Evaluating the color scale, we observe 14 out of 20 of the latest years (2002–2022) with a positive \(v_k\), and only 6 out of the 20 latest years with a negative \(v_k\), indicating a trend towards increasing \(f_s'\) over time. Reduction in the absolute value of \(v_k\) between null and full models highlight years when TCI explains anomalies in \(f_s'\). Strong negative shifts are observed in positive intercepts in 2014, 2005, 2017, 1992, and 2012, suggesting that TCI explained more of the anomalously high \(f_s'\) in these years (Fig. 2c, Text S9, S10).

Trends in tropical cyclone dynamics

Between 1977 and 2022, 579 out of 729 tropical cyclones (TCs) in the NOAA HURDAT2 Atlantic Basin database intersected with HMP infrastructure (HMP-intersecting TC) in the Central and Eastern United States. For each year, the lifetime maximum intensity of the strongest HMP-intersecting TC was identified (Fig. 3a). There is evidence that the lifetime maximum intensity of the strongest annual HMP-intersecting TC is getting stronger over time. Since 1975, a significant positive linear trend in components of TCI (maximum sustained near-surface windspeed and minimum sea-level pressure) are observed (Fig. 3a). That the annual maximum sustained HMP-intersecting TC windspeed has been increasing by about 0.6 knots per year since 1975, corresponding to a 27.6 knot increase over the 46 study period. To put this number in perspective, the difference in windspeed between a strong Category 2 storm and a weak Category 4 storm on the Saffir Simpson hurricane scale is 18 knots. Similarly, we observe a significant negative linear trend in annual minimum TC pressure (where decreasing pressures indicate increasing storm intensity) by -0.7 mBar per year (Fig. 3a,b). This result is unsuprising given that maximum windspeed and minimum pressure are highly correlated proxies of hurricane strength48.

Drawing from these trends, the annual maximum wind speed and minimum pressure of an HMP-intersecting TC in 1970 was approximately 107 knots and 954 mBar, respectively; corresponding to a Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale. In 2010, the annual maximum wind speed and minimum pressure of an HMP-intersecting TC were 130 knots and 928 mBar, respectively; corresponding to a Category 4 hurricane (Fig. 3a,b). Projecting this trend to 2050 produces an estimated annual maximum wind speed and minimum pressure of 154 knots and 902 mBar, respectively; corresponding to an annual lifetime maximum intensity of a landfalling Atlantic TC reflecting a Category 5 storm (Fig. 3c, yellow bars). 2050 projections are presented for illustrative purposes only: linear interpolation of hurricane strength based on time, when we assume that the physical driver of this increase in strength is increasing sea surface temperatures under climate change, rests on physically flawed assumptions (Text S6). Incidentally, significant southeastern shifts in origin coordinates of the annual maximum TC intersecting with HMP infrastructure (corresponding to a 0.15 degrees/year southerly and 0.41 degree/year easterly shift) were also observed, consistent with the literature (e.g49, Figure S8). Still, projected maximum annual TCs represent the highest-magnitude storm that could be expected to impact the Gulf Coast regions (Texas coast, Mississippi Delta, and Southeast) on an annual basis, which is an important consideration for infrastructural risk assessment. Projected \(f_s'\) for theoretical annual maximum regional TCs are also indicated in Fig. 3c,d.

Linear trends in 1975–2022 annual maximum HMP-intersecting (a) maximum sustained near-surface windspeed and (b) minimum sea-level pressure. (c) Poisson projected \(f_s'\) (Eq 3) by region (color), with range of observed historical regional TCI indicated by solid lines and out-of-sample projections indicated with dashed lines. Inverted triangle, diamond, and triangle symbols correspond to the annual maximum regional TCI projected from observed linear trends for 1970, 2010, and 2050, respectively. Yellow bars indicate maximum projected HMP-intersecting TCI for 1970 (left), 2010 (center), and 2050 (right); extrapolated from linear trends observed in the regionally aggregated data from 1975-2022 (Fig. 2a,b). Dashed vertical gray lines represent storm classification thresholds on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale, with corresponding storm classification indicated as text along top of figure. (d) Values in table represent projected \(f_s'\) by region for 1970, 2010, and 2050 projected maximum annual regional TCI. Here, “MS Delta” refers to “Mississippi Delta”.

Projecting from local trends in annual maximum TCI, which are much weaker than trends in lifetime maximum intensity of the storm, the Mississippi Delta and Texas Gulf Coast regions are projected to see an over 5-fold increase in the frequency HMP failure associated with the local annual maximum TC (\(f_s'\) associated with the TC with the highest windspeed per location group) in 2050 compared to 1970; the High Plains and Midwest are projected to see nearly a four-fold increase in \(f_s'\) with the annual maximum TC by 2050, and the Southeast and Northeast a doubling in \(f_s'\) with the annual maximum TC (Fig. 3d). These projections suggests a 200–500% increase in HMP failure frequency, independent of drivers of background HMP failures (\(f_o\)) such as increased pipe age or length, associated with the local annual maximum TC across the Eastern United States in 2050, relative to 1970 levels.

Discussion

TC-related HMP failures (\(f_s'\)) are more likely, and exponentially more frequent, for stronger hurricanes. The greatest TCI-related increases in \(f_s'\) are observed along the Texas and Mississippi coasts, regions with dense crude oil pipeline infrastructure, high shrink-swell potential of local soils, and exposure to coastal storm surges and high-intensity TCs7,15. Increased frequency of \(f_s'\) associated with even small shifts in TCI is observed in the High Plains, where only low-intensity storms have occurred, indicating sensitivity of High Plains HMP infrastructure to intensity-invariant impacts of TCs, such as associated tornado activity and interactions between intense precipitation and high shrink-swell potential of local soils, which can put significant mechanical stress on underground pipeline networks31,32,40. Lack of crude oil pipeline infrastructure equates to a significant reduction in overall HMP pipeline failure associated with extreme events on the Southeast coast, despite exposure to frequent, intense TCs (Figs. 1, 3c).

Significant linear trends are observed in the lifetime maximum intensity of the annual maximum TC during the study period, indicating that the annual maximum TC has increased from a Category 3 to a Category 4 between 1970 and 2010. Linear trends in annual maximum lifetime TCI noted here are both notable in terms of their magnitude and in terms of their consistency with previous research50,51,52,53. In using this observed trend to predict the strength of the future annual maximum storms, we make important and flawed assumptions about the physical drivers of TCs. The first assumption is that hurricanes are powered by temperature differences between the warm sea surface and the cold upper atmosphere. There is scientific consensus on this principle (e.g.54). The second assumption is that sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the subtropical Atlantic, where Atlantic TCs originate, are increasing because of anthropogenic climate change. There is emerging scientific consensus backing this assumption, with multiple studies documenting robust trends in SSTs over time55,56,57, in line with what would be expected from physics-based coupled earth systems models58,59. The third assumption is that the historical relationship between SST and hurricane strength will remain stationary over time. There is strong physical evidence countering the realism of this assumption, and so resting on this assumption represents a critical limitation of this approach. First, there are thermodynamic limits to SST-associated TC strength increases over time: climate change is driving both increases in SST and increases in temperatures in the upper atmosphere, reducing the vertical temperature contrast that drives TC formation45,54. In numerical models, once tropical Atlantic SSTs get above a certain threshold (\({\tilde{2}}6.5^{\circ }\)C), a “saturation” of this TC strengthening effect is noted, and SST warming yields smaller increases in TC strength45. Diminishing returns in TC strength for SST warming above \(26.5^{\circ }\)C are associated with energy limitations in total atmospheric vapor storage, and because climate change is modifying other atmospheric drivers and constraints of hurricane formation, such as wind shear, humidity levels, and vertical stability; all of which impact TC formation and development in complex ways60. Finally, not all of the energy from increasing SSTs will be dissipated as increased windspeeds in TCs. Increased energy available for TCs may mean that storms may become more numerous (though evidence for this is lacking in the historical record), larger, more persistent, or may deliver more intense rainfall24.

This study is not intended to contribute to the conversation on the physics of hurricane propagation in a warming climate, but on how our current understanding of TC risk should be considered in infrastructure risk assessment. In the absence of a robust alternative, for illustrative purposes only, we extrapolate from observed linear trends in maximum annual windspeed and minimum annual pressure twenty-five years into the future (to 2050). Our justification is this: the tropical Atlantic SST has been increasing at a rate of about \(0.4^{\circ }\)C per decade since 199361. Assuming current mean SST of 25 \(^{\circ }\)C in the tropical Atlantic, we would expect to be approaching the temperature range associated with “saturation” of impacts of SST-driven strengthening of TCs around 205060. It is in this near-term window, where evidence suggests that trends linking SST increase to increased intensity of major TCs may hold, that we project the lifetime maximum intensity of the annual maximum storm intersecting with HMP infrastructure may increase to a Category 5 storm by 2050.

At existing levels we see an exponential increase in \(f_s'\) with increasing TC strength, any continuation of the trend towards increasing strength in the annual maximum TC may markedly increase HMP failure frequency. Increasing trends in TC-related HMP failure across the United States suggest that these increases are associated with both increased vulnerability of HMP infrastructure to TC impacts (indicated by linear trends in \(v_k\) and some weak trends in \(f_o\), particularly in Texas, Fig. 1b), and increasing intensity of TCs intersecting with HMP infrastructure (indicated by linear trends in TCI, Fig. 2a,b). There are multiple potential pipeline-side drivers of increase in both \(f_o\) and \(f_s'\) over time that are independent of increasing TC intensity, most notably increasing age of pipeline infrastructure and expanding networks (meaning that both baseline and TC associated pipeline failures are more likely simply because there is more pipeline to fail). Reports of HMP failures due to all causes have increased markedly in the last fifty years (Figure S1), indicating the growing scope and vulnerability of this essential infrastructure system. Most pipelines in operation today have surpassed 45 years of service, a threshold associated with greater risk of failure62.

These findings underscore the vulnerability of pipeline infrastructure to tropical cyclones (TCs) in general, and major hurricanes in particular. Although natural force damage accounts for only 4.3% of total failure cause attributions in the PHMSA dataset, 32.5% of failures in United States regions impacted by TC storm tracks occur within 60 days of a TC intersection (Figure S2), and we see that more frequent failures 60 days after a TC intersection are significantly and positively related to TCI, after detrending for non-storm associated background failure rates. This provides new data to back previous claims in the literature of under-reporting of TC-related HMP failures15. TC intensity is a statistically significant predictor of both the likelihood and frequency of HMP failures during a storm, with failure frequency increasing exponentially with increasing TCI. This indicates potentially significant exposure to pipeline infrastructure under major hurricanes in particular, and suggests that an increase in intensity of the annual maximum storm is potentially a more impactful variable with regards to predicting future frequency of pipeline failure then an increase in the total number of storms24. Historical data indicates that the annual maximum hurricane intersecting with hazardous material pipeline has increased from a Category 3 storm in 1970 to a Category 4 storm in 2010. Projecting this trend implies that a Category 5 hurricane can be expected to intersect with HMP infrastructure approximately annually by 2050, with strong implications for future HMP failure frequency across the eastern United States, particularly along the Gulf Coast. Though our results are consistent with current consensus that major hurricanes (Category 3 or above) have increased in observational records in the past fifty years24,51,63,64, we reiterate that there is no scientific consensus on how TCs will respond to climate change, so extrapolating from observed linear trends is for near-term and illustrative purposes only. This question can be further explored with the use of numerical projections or synthetic TCs, though this approach is likewise limited.

Though limited by the nature of HMP incident reporting data and well-documented limitations to prediction of future Atlantic TC dynamics, these findings strongly support conclusions from previous research suggesting that TC-associated impacts to HMP infrastructure are under-reported in regulatory pipeline failure records as well as in the scientific literature (e.g.14), and stress the need for tailored risk assessments that incorporate complex contributions of natural hazards forcings, including TC forcings, to HMP failure occurrence in incident reports. Given the costs of HMP failures in terms of health, environment, and economic damages, identifying HMP failures associated with TCs are critical to administration of appropriate relief during national emergencies, as well as to improving the accuracy of our accounting of financial damages associated with TC events. If collected, such data could lend insight to improved pipeline designs and targeted mitigation strategies that are essential for safeguarding critical infrastructure against the increasing risks posed by expanding, aging pipeline networks intersecting with intensifying TCs under climate change.

Methods

Data preparation

This analysis aims to identify TC-associated pipeline failures in the PHMSA database5. Prior to 2002, “natural force damages” was not a causal category on incident forms, and post-2002, there is suggested negative reporting bias to this causal category (Text S1, Figure S1,14). All data and code comprising this analysis are available online (see SI,65). We examine intersections between PHMSA Failure Data (HMP failures) and 6-hourly points in the NOAA HURDAT2 Dataset (TC points,66). We merge the datasets by identifying records where HMP failure coordinates fall within the tropical cyclone force diameter (calculated from 34 kt wind radii maximum extent) or, prior to 2004 when the force diameter is unavailable, within a 300 mile (the approximate average tropical cyclone force diameter in the HURDAT 2 database). Additionally, the failures must occur within 60 days of the TC point intersection, where we observe a local inflection in the histogram of latency between HMP failures and TC intesection (Text S1, Figure S2). Before merging, all HMP failures and TC points that fall outside the North American TC storm track region are discarded. If HMP failures do not intersect with any TC points, they are associated with a no-storm identifier. Likewise, TC points that do not intersect with HMP failure points are retained as records in the merged HMP x TC database with no affiliated HMP failure points (Text S1). To account for regional variations in hazardous material pipeline (HMP) failure rates due to factors unrelated to tropical cyclones (e.g., local pipeline construction practices, network length and density, network age, ambient geophysical conditions, and use characteristics), we applied k-means clustering to the latitude and longitude of all records in the merged HMP x TC database to define six spatial sub-regions, each one approximately 300 miles in diameter, which are then modeled as random effects (Text S1, Fig. 1a,67).

For each record in the merged TC by HMP dataset, we define variable \(\eta _x\) which has a value of 0 for TC points with no associated HMP failure points, a value of 1 for TC points associated with individual HMP failures, and a value of 1 for HMP failure points unassociated with TC points. The frequency of HMP failures by storm is then aggregated by summing \(\eta\) on storm name, year (as storm names can be reused from year to year) and region, providing the frequency of HMP failures per TC and per spatial subregion (\(f_s^{(i,j, y)}\) or \(f_s\)):

Here x is the index for a record in the merged HMP x TC database; \(\mathcal {X}_{i,j,y}\) denotes the set of all records with storm name i, region j (defined by k-means cluster on latitude and longitude) and year y. The condition \(i(x) \ne 0\) ensures that only records affiliated with a tropical cyclone are included in the summation.

We assume that \(f_s\) will include some failures that would have occurred regardless of TC intersection. We also assume that there may be spatial and temporal trends in this“background failure frequency,” as several key drivers of pipeline failure vulnerability vary by region and are increasing over time, such as increasing maximum pipe age and increasing pipe length. To adjust for this effect, we define the background failure frequency (\(f_o^{(j, y)}\) or \(f_o)\) as the average number of HMP failures during a 60-day window in region j, when there was no storm (\(i=0\)). We base this on data from the approximately 5-year window (\(Y_k\)) that includes year y:

Here, \(\mathcal {X}_{j,y}\) denotes the set of all records corresponding to region j and year y, where y is a member of \(Y_k\), or the set of years in the \(k^{\text {th}}\) period between 1972 and 2022, bounded by the years 1980, 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2022. The term \(N(Y_k)\) represents the total number of days within the years in \(Y_k\).

The storm-related failure frequency (\(f_s'^{(i,j, y)}\) or \(f_s'\) ) is then defined as difference between each storm-associated frequency (\(f_s^{(i,j, y)}\)) and background failure rate (\(f_o^{(j, y)}\)):

Model fitting

Due to the multilevel nature of the data and the presence of zero values in \(f_s'\) (Eq. 2 and 3), we employed strategically nested mixed-effects logistic (Text S2, S7) and mixed-effects Poisson regressions (Text S3 and S8; Figure S6; Table S1). These models used TC intensity (TCI, derived as the first principal component of regional maximum TC wind speed and regional minimum TC pressure) as the main predictor variable (Text S1). The mixed-effects Poisson regression allows us to predict \(f_s'\), a count variable, as a function of TCI, a continuous variable (Text S3 and S7, Figure S7; Table S2):

Here, \(\lambda _{ijy}\) is the predicted TC-associated HMP failure frequency for the \(i\)-th storm in the \(j\)-th region and \(y\)-th year; \(TCI_{ijy}\) is the maximum TC intensity for the \(i\)-th storm in the \(j\)-th region and \(y\)-th year; and \(\beta _0\) is the overall log-rate intercept. \(\beta _1\) is the fixed log-rate coefficient for the predictor \(TCI_{ijy}\); \(u_j\) is the random intercept for region \(j\), capturing the residual deviation of the \(j\)-th region from the overall intercept; \(v_y\) is the random intercept for year \(y\), capturing the residual deviation of the \(y\)-th year from the overall intercept; \(\gamma _j\) represents the random log-rate coefficient local to each region \(j\); and \(\epsilon _{ijy}\) is the residual error term. The “full” model (Eq 4) is compared to a null model with no fixed effects (Eq 5):

The panel model structure mitigates variance bias associated with omitted variables and non-independence of observations65,68, and the nested panel model structure (comparing Eq 4 to Eq 5) enables a more detailed examination of how temporal (year) and spatial (region) variability in \(f_s'\) is influenced by TCI. The model assumes variance component partitioning between random effects, where \(\quad u_j(i) \sim \mathcal {N}(0, \sigma ^2_{\text {j}})\), \(\quad v_y(i) \sim \mathcal {N}(0, \sigma ^2_{\text {y}})\), and \(\quad \epsilon _{ijy} \sim \mathcal {N}(0, \sigma ^2_{\epsilon })\) (Text S4, S5).

Estimating trends and future predictions

Historical (1970–2022) trends in annual TC minimum sea-level pressure (“pressure”) and maximum sustained near-surface wind speed (“windspeed”) were quantified using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. We make a simplified, but necessary, assumption that the linear trends will remain constant until 2050 (see discussion and Text S6 for justification and limitations to this approach), and use these models to estimate the 1970, 2010, and 2050 annual maximum TC windspeed and minimum pressure, both globally and for each region. These values are converted to the 1970, 2010, and 2050 TCI using the principal components model trained on historical TC data. TCI values input into the trained Poisson mixed-effects model (Eq 4) to predict storm-associated failure frequency (\(f_s'\)) associated with the regional annual maximum TCI for 1970, 2010, and 2020.

Data availability

All data and processing code are available on GitHub at https://github.com/LizCarter492/TCpipeline.

References

Parfomak, P. W. DOT’s federal pipeline safety program: Background and issues for congress. Congressional Research Service (2023).

International Energy Agency. Key world energy statistics 2016 (OECD, 2016).

Sovacool, B. K. The costs of failure: A preliminary assessment of major energy accidents, 1907–2007. Energy Policy 36, 1802–1820 (2008).

Mignan, A., Spada, M., Burgherr, P., Wang, Z. & Sornette, D. Dynamics of severe accidents in the oil & gas energy sector derived from the authoritative ENergy-related severe accident database. PLoS ONE 17, e0263962 (2022).

US Department of Transportation Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. Gas Distribution, Gas Gathering, Gas Transmission, Hazardous Liquids, Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG), and Underground Natural Gas Storage (UNGS) Annual Report Data (2023).

Belvederesi, C., Thompson, M. S. & Komers, P. E. Statistical analysis of environmental consequences of hazardous liquid pipeline accidents. Heliyon 4, e00901 (2018).

Restrepo, C. E., Simonoff, J. S. & Zimmerman, R. Causes, cost consequences, and risk implications of accidents in US hazardous liquid pipeline infrastructure. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2, 38–50 (2009).

Maxwell, K., Kiessling, B. & Buckley, J. How clean is clean: a review of the social science of environmental cleanups. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 083002 (2018).

U.S. Government Publishing Office. Title 49 - Transportation. Parts 191 - 195 (1970).

Armstrong, M. F. Jr. The Natural Gas Pipeline Safety Act of 1968. Nat. Resources Law. 2, 142 (1969).

Zakikhani, K., Nasiri, F. & Zayed, T. A review of failure prediction models for oil and gas pipelines. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 11, 03119001 (2020).

Ricci, F., Casson Moreno, V. & Cozzani, V. A. comprehensive analysis of the occurrence of Natech events in the process industry. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 147, 703–713 (2021).

Lam, C. & Zhou, W. Statistical analyses of incidents on onshore gas transmission pipelines based on PHMSA database. Int. J. Pressure Vessels Piping 145, 29–40 (2016).

Girgin, S. & Krausmann, E. Analysis of pipeline accidents induced by natural hazards (Brussels, Belgium, European Union, 2014).

Girgin, S. & Krausmann, E. Lessons learned from oil pipeline natech accidents and recommendations for natech scenario development. Institute for the Protection and Security of the Citizen. Elisabeth Krausmann, Address: Joint Research Centre, Via E. Fermi 2749, 21027 (2015).

Abraham, J. P. et al. A review of global ocean temperature observations: Implications for ocean heat content estimates and climate change: REVIEW OF OCEAN OBSERVATIONS. Rev. Geophys. 51, 450–483 (2013).

Cheng, L. et al. New record ocean temperatures and related climate indicators in 2023. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 41, 1068–1082 (2024).

Keil, P. et al. Multiple drivers of the North Atlantic warming hole. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 667–671 (2020).

Vecchi, G., Landsea, C., Zhang, W., Villarini, G. & Knutson, T. Changes in Atlantic major hurricane frequency since the late-19th century. Nat. Commun. 12, 4054 (2021).

Guzman, O. & Jiang, H. Global increase in tropical cyclone rain rate. Nat. Commun. 12, 5344 (2021).

Reed, K. A., Wehner, M. F. & Zarzycki, C. M. Author Correction: Attribution of 2020 hurricane season extreme rainfall to human-induced climate change. Nat. Commun. 13, 2589 (2022).

Pielke, R. A. Jr. et al. Normalized Hurricane Damage in the United States (Nat, Hazards Rev, 2005).

Mallard, M. S., Lackmann, G. M., Aiyyer, A., Hill, K., Experimental design and isolation of thermodynamic effects. Atlantic hurricanes and Climate Change. Part I. J. Clim. 26, 4876–4893 (2013).

Camargo, S. J. et al. An update on the influence of natural climate variability and anthropogenic climate change on tropical cyclones. Trop. Cyclone Res. Rev. 12, 216–239 (2023).

Nair, G. S., Dash, S. & Mondal, G. Review of Pipeline Performance during Earthquakes since 1906. J. Perform. Constr. Facil. 32, 04018083 (2018).

Murphy, J. F. & Conner, J. Beware of the black swan: The limitations of risk analysis for predicting the extreme impact of rare process safety incidents. Process Saf. Prog. 31, 330–333 (2012).

Qin, R., Khakzad, N. & Zhu, J. An overview of the impact of Hurricane Harvey on chemical and process facilities in Texas. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 45, 101453 (2020).

Czajkowski, J., Simmons, K. & Sutter, D. An analysis of coastal and inland fatalities in landfalling US hurricanes. Nat. Hazards (Dordr.) 59, 1513–1531 (2011).

Burow, D., Ellis, K. & Tran, L. Simultaneous and collocated tornado and flash flood warnings associated with tropical cyclones in the contiguous United States. Int. J. Climatol. 41, 4253–4264 (2021).

Cruz, A. M., Steinberg, L. J. & Vetere-Arellano, A. L. Emerging issues for natech disaster risk management in Europe. J. Risk Res. 9, 483–501 (2006).

Kishné, A. S., Morgan, C. & Miller, W. Vertisol crack extent associated with gilgai and soil moisture in the Texas Gulf Coast Prairie. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 73, 1221–1230 (2009).

Tamizdoust, K., Farzi Sizkow, S., AbdelHamid, Y., Helal, A. & Bryant, J. T. Forensic Eng. 714–724 (ASCE, 2024).

Wang, H., Yajima, A., Liang, R. Y. & Castaneda, H. A clustering approach for assessing external corrosion in a buried pipeline based on hidden Markov random field model. Struct. Saf. 56, 18–29 (2015).

Li, X. et al. Effect of residual and external stress on corrosion behaviour of X80 pipeline steel in sulphate-reducing bacteria environment. Eng. Fail. Anal. 91, 275–290 (2018).

Sengul, H., Santella, N., Steinberg, L. J. & Cruz, A. M. Analysis of hazardous material releases due to natural hazards in the United States. Disasters 36, 723–743 (2012).

Girgin, S. & Krausmann, E. Historical analysis of U.S. onshore hazardous liquid pipeline accidents triggered by natural hazards. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 40, 578–590 (2016).

Edwards, R. Tropical cyclone tornadoes: A review of knowledge in research and prediction. Electron. J. Sev. Storms Meteorol. 7, 1–61 (2021).

Lai, Y., Li, J., Gu, X., Liu, C. & Chen, Y. D. Global compound floods from precipitation and storm surge: Hazards and the roles of cyclones. J. Clim. 34, 1–55 (2021).

Booth, J. F., Narinesingh, V., Towey, K. L. & Jeyaratnam, J. Storm surge, blocking, and cyclones: A compound hazards analysis for the Northeast United States. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 60, 1531–1544 (2021).

Clayton, C. R. I., Xu, M., Whiter, J. T., Ham, A. & Rust, M. Stresses in cast-iron pipes due to seasonal shrink-swell of clay soils. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Water Manag. 163, 157–162 (2010).

Olive, W. W. et al. Swelling clays map of the conterminous United States (1989).

Landsea, C. W. & Franklin, J. L. Atlantic hurricane database uncertainty and presentation of a new database format. Mon. Weather Rev. 141, 3576–3592 (2013).

Brotzge, J. & Donner, W. The tornado warning process: A review of current research, challenges, and opportunities. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 94, 1715–1733 (2013).

Elhorst, J. P. in Spatial econometrics: From cross-sectional data to spatial panels 37–93 (Springer, 2013).

Shen, W., Tuleya, R. E. & Ginis, I. A sensitivity study of the thermodynamic environment on GFDL model hurricane intensity: Implications for global warming. J. Clim. 13, 109–121 (2000).

EPA. Inter- and intra-state pipelines for natural gas in the United States and its territories https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=461c53a9c05f4fc19b1017c96e8a03c0. Accessed: 2025-05-08. (2020).

Esri. ArcGIS Pro Software. Version 3.3. Accessed: 2024-11-25. (2025). https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview.

Knaff, J. A. & Zehr, R. M. Reexamination of tropical cyclone wind-pressure relationships. Weather Forecast. 22, 71–88 (2007).

Weaver, M. M. & Garner, A. J. Varying genesis and landfall locations for North Atlantic tropical cyclones in a warmer climate. Sci. Rep. 13, 5482 (2023).

Gilford, D. M., Giguere, J. & Pershing, A. J. Human-caused ocean warming has intensified recent hurricanes. Environ. Res.: Climate 3, 045019 (2024).

Kossin, J. P., Knapp, K. R., Olander, T. L. & Velden, C. S. Global increase in major tropical cyclone exceedance probability over the past four decades. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117, 11975–11980 (2020).

Holland, G. & Bruyère, C. L. Recent intense hurricane response to global climate change. Clim. Dyn. 42, 617–627 (2014).

Elsner, J. B. Evidence in support of the climate change-Atlantic hurricane hypothesis. Geophys. Res. Lett.33, (2006).

Cione, J. J. & Uhlhorn, E. W. Sea surface temperature variability in hurricanes: Implications with respect to intensity change. Mon. Weather Rev. 131, 1783–1796 (2003).

Cane, M. A. et al. Twentieth-century sea surface temperature trends. Science 275, 957–960 (1997).

Kaplan, A., Kushnir, Y., Cane, M. A. & Blumenthal, M. B. Reduced space optimal analysis for historical data sets: 136 years of Atlantic sea surface temperatures. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 102, 27835–27860 (1997).

Karnauskas, K. B., Zhang, L. & Amaya, D. J. The atmospheric response to North Atlantic SST trends, 1870–2019. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL090677 (2021).

Sung, H. M. et al. Future changes in the global and regional sea level rise and sea surface temperature based on CMIP6 models. Atmosphere 12, 90 (2021).

Yang, X. & Huang, P. Improvements in the relationship between tropical precipitation and sea surface temperature from CMIP5 to CMIP6. Clim. Dyn. 60, 3319–3337 (2023).

Tonkin, H., Holland, G. J., Holbrook, N. & Henderson-Sellers, A. An evaluation of thermodynamic estimates of climatological maximum potential tropical cyclone intensity. Mon. Weather Rev. 128, 746–762 (2000).

ECMWF. Sea surface temperature (2023).

Awuku, B., Huang, Y. & Yodo, N. Predicting natural gas pipeline failures caused by natural forces: An artificial intelligence classification approach. Appl. Sci. (Basel) 13, 4322 (2023).

Elsner, J. B. Continued increases in the intensity of strong tropical cyclones. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 101, E1301–E1303 (2020).

Emanuel, K. Evidence that hurricanes are getting stronger. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 13194–13195 (2020).

Carter, E., Hultquist, C. & Wen, T. GRRIEn analysis: A data science cheat sheet for Earth scientists learning from global Earth observations. Artif. Intell. Earth Syst. 2, 1–49 (2023).

NHC. Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT2) 1851-2023 (2023).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res.abs/1201.0490, 2825–2830 (2011).

Dormann, F. et al. Methods to account for spatial autocorrelation in the analysis of species distributional data: a review. Ecography (Cop.) 30, 609–628 (2007).

Holland, G. A revised hurricane pressure-wind model. Mon. Weather Rev. 136, 3432–3445 (2008).

Knutson, T. et al. Tropical cyclones and climate change assessment: Part I: Detection and attribution. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 1987–2007 (2019).

Kossin, J. P. Hurricane intensification along United States coast suppressed during active hurricane periods. Nature 541, 390–393 (2017).

Michanowicz, D. R. et al. A national assessment of underground natural gas storage: identifying wells with designs likely vulnerable to a single-point-of-failure. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 064004 (2017).

Qin, G., Zhang, P., Hou, X., Wu, S. & Wang, Y. Risk assessment for oil leakage under the common threat of multiple natural hazards. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 27, 16507–16520 (2020).

De Luca, P., Hillier, J. K., Wilby, R. L., Quinn, N. W. & Harrigan, S. Extreme multi-basin flooding linked with extra-tropical cyclones. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 114009 (2017).

Czajkowski, J., Villarini, G., Montgomery, M., Michel-Kerjan, E. & Goska, R. Assessing current and future freshwater flood risk from north Atlantic tropical cyclones via insurance claims. Sci. Rep. 7, 41609 (2017).

Cruz, A. M. & Krausmann, E. Vulnerability of the oil and gas sector to climate change and extreme weather events. Clim. Change 121, 41–53 (2013).

Elsner, J. B. Hurricanes and climate change. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 89, 677–679 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The historical tropical cyclone data used in this study were obtained from the National Hurricane Center’s HURDAT2 dataset (Hurricane Database version 2), which is available from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). We acknowledge the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) for providing the Failure Database, which is a vital resource for tracking and analyzing pipeline failures. Funding for M. Smith was provided by the Graduate Education for Minorities (GEM) Fellowship Program, https://www.gemfellowship.org. This research has been conducted with support of the Digital Waters Flagship (Research Council of Finland decision no. 359228) and the Broad Agency Announcement W912HZ-21-BAA-01 issued by the U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center Coastal and Hydraulics Laboratory.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft. E.C.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—revision, Data curation, Software, Validation, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carter, E., Smith, M. Strengthening tropical cyclones are associated with more frequent hazardous material pipeline failures in the Eastern US. Sci Rep 16, 124 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29059-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29059-2