Abstract

In sepsis, temperature fluctuations are typical. The objective of this study was to determine whether hypothermia in sepsis patients was associated with an increased risk of death. To identify septic patients with and without hypothermia, the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) database was queried. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Multivariate Cox regression was utilized to determine the association between hypothermia and all-cause mortality, and propensity score matching (PSM) and an inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) were used to validate our findings. Our analysis comprised 19,636 septic patients, of whom 937 (4.8%) developed hypothermia within 24 h of intensive care unit (ICU) admission. The hypothermia group had a higher 180-day and 360-day mortality than the no hypothermia group (P < 0.001). Hypothermia was associated with higher 180-day and 360-day mortality in the matched cohort and in the weighted cohort. In conclusion, hypothermia was associated with increased in-hospital and all-cause mortality in septic patients, emphasizing the significance of temperature protection in the ICU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sepsis is a series of abnormal physiological reactions triggered by an infection, resulting in organ damage that is life-threatening and associated with a high mortality and disability rate1. A series of abnormal physiological reactions affects vital signs including body temperature (BT), respiratory rate (RR), heart rate (HR), and blood pressure (BP)2,3. Hypothermia, tachypnea, tachycardia, and hypotension are frequently related with altered clinical outcomes in sepsis patients4,5,6.

Hypothermia, which is defined as having a BT that is lower than 36 ℃, is one of the hallmark characteristics of sepsis7. According to the statistics, people diagnosed with sepsis have a 9–35% chance of developing hypothermia8. A post-hoc analysis of a retrospective cohort research revealed that BT, as a vital sign, is associated with increased mortality in septic patients and may be an early clinical predictor of sepsis-induced immunosuppression9. Even minute fluctuations in body temperature can affect inflammation and immunological function, with varying implications on patient outcomes10. There is accumulating evidence that the systemic immune response plays a crucial role in the etiology and progression of sepsis11,12. During the first phase of sepsis, the immune response is dominated by pro-inflammatory activities and is conducive to pathogen elimination13. Progressive sepsis is primarily defined by an impaired immunological response, as seen by a decrease in the function and quantity of immune cells14. However, the association between hypothermia and long-term outcomes is controversial, with potential confounding variables including age, gender, comorbidities, and other life support requirements. However, the definition of hypothermia has the potential to greatly impact the clinical consequences that are observed. It is necessary to conduct a well-designed randomized controlled study in order to overcome these constraints, despite the fact that such a trial is challenging to carry out in patients who are septic.

To control for sample selection bias and imitate the randomization process, we apply propensity score matching (PSM) and inverse probability treatment weighting (IPTW) techniques. This study aims to determine if hypothermia is an independent predictor of death in septic patients, with hypothermia defined as a BT < 36 °C. In order to investigate the impact of hypothermia on the 180-day mortality of septic patients, the present study employed the PSM and IPTW models.

Methods

Study design

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis using the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC- IV), a major database based in the United States15. Patient information from 2008 to 2019 who were admitted to the intensive care units (ICUs) at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center is included in the MIMIC- IV database, which is both comprehensive and of high quality. One of the authors, CJM, was able to successfully complete the necessary training to use the database and acquire the certificate (certification number 12473022). Because the project did not affect clinical care and all protected health information was anonymized, individual patient permission was waived.

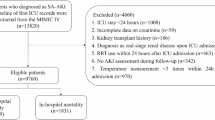

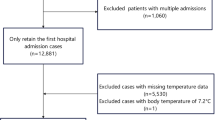

Selection of participants

Patients in the MIMIC-IV who met the criteria for sepsis were considered candidates for participation in the study. The sepsis was determined to be present based on the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) criteria2; Briefly, sepsis was diagnosed in individuals with proven or suspected infection and an acute change in overall Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of ≥ 2 points. The MIMIC-IV recognized infection based on the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition (ICD-9) code. The study included data from the initial hospital/ICU admission (if a patient has been admitted many times). Patients with a body temperature > 38 °C were excluded due to the small sample size in this group, which could affect statistical power and data consistency. Additionally, the distinct pathophysiological mechanisms of hyperthermia in sepsis make it challenging to draw reliable conclusions, so excluding this subgroup ensures a more homogeneous analysis focused on normothermic and hypothermic cases. We excluded patients who spent less than 24 h in the ICU and whose body temperature was greater than 38 °C. Included patients for whose mean BT < 36 °C during the first 24 h after admission to the ICU were classified as the hypothermia group, and the rest of the patients comprised the no hypothermia group. Figure 1 depicts the patient enrollment process of this study.

Variable extraction

Using Structured Query Language (SQL), baseline characteristics within the first 24 h after ICU admission were obtained, including age, gender, race, marital status, insurance, admission type and weight. Vital signs included the heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), mean BT and saturation of pulse oxygen (SpO2). Laboratory variables including blood glucose (Glu), haematocrit (HCT), haemoglobin (HGB), platelet (PLT) count, white blood cell (WBC) count, anion gap (AG), bicarbonate, calcium, chloride, sodium, potassium, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cr), international normalized ratio (INR), prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT) and urine output were measured during the first 24 h in the ICU. Severity at admission as measured by SOFA score and the Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II). Comorbidities including myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure (CHF), cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), mild liver disease, diabetes without complication, diabetes with complication, renal disease, malignant cancer, severe liver disease and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) were also collected for analysis based on the recorded ICD-9 codes in the MIMIC-IV database. The use of mechanical ventilation, application of continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and administration of vasoactive agent were also recorded.

Outcomes

The primary outcome in the present study was 180-day mortality. Secondary outcomes included 360-day mortality, ICU length of stay (LOS) and in-hospital mortality.

Statistical analysis

No data loss occurred for categorical variables. Less than 10% of continuous variables were lost, thus mean values were substituted for the missing information (Table S1). Using the Anderson-Darling test, the normal distribution of all continuous variables was examined (Table S2). Continuous variables are shown as medians [interquartile ranges (IQRs)]; categorical variables are presented as total numbers and percentages. Comparisons between groups were made using the χ2 test for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, as appropriate.

The total number of initial participants comprised the original cohort. PSM was used to create well-balanced groupings, notably the matched cohort, in addition to the original cohort. The propensity score was calculated utilizing a non-parsimonious multivariable logistic regression model, with hypothermia as the dependent variable and all baseline parameters (age, gender, race, marital status, insurance, admission type, weight, HR, RR, SBP, DBP, BT, SpO2, Glu, HCT, HGB, PLT count, WBC count, AG, bicarbonate, calcium, chloride, sodium, potassium, BUN, Cr, INR, PT, PTT, urine output, SOFA score, SAPS II, MI, CHF, cerebrovascular disease, COPD, mild liver disease, diabetes without complication, diabetes with complication, renal disease, malignant cancer, severe liver disease, AIDS, the use of mechanical ventilation, application of CRRT and ECMO, and administration of vasoactive agent)as the independent factors. Patients in the hypothermia group were matched with patients in the no hypothermia group using the greedy nearest neighbor matching method with a caliper width of 0.2. In addition, the predicted propensity ratings were used as weights to generate an IPTW cohort (called weighted cohort). PSM and IPTW-based propensity score adjustments were also applied to confirm the validity of our findings16,17,18. To assess the efficacy of the PSM and IPTW, the standardized mean differences (SMD) were computed. SMD < 0.1 is considered a reasonable compromise between the groups19.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.1.1), and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

This study enrolled a total of 19,636 patients, with 937 individuals in the hypothermia group and 18,699 patients in the control group. The median age of the study patients was 68.2 [22.2] years old, and 11,273 (57.4%) were males. In total, the 180-day mortality was 28.5% and 2,933 (14.9%) patients died in the hospital. When examining BT as a continuous variable, we observed an “L” -shaped curve, with high HRs for 180-day death observed for low BT levels and with the lowest HRs seen around BT of 37.3 °C, with flattening or slightly increasing mortality at even higher BT levels (Figure S1). After PSM, 927 patients in the hypothermia group and 927 patients in the no hypothermia group were enrolled in the PSM cohort (Table 1). Before matching, the majority of factors between the two groups were not balanced. After matching, the imbalanced covariates were balanced in the matched cohort and weighted cohort (Table 2, Table S3 and Fig. 2).

The chi-square test showed that the hypothermia group had a higher 180-day mortality [482 (51.4%) vs. 5117 (27.3%), P < 0.001] than the no hypothermia group in the original cohort. In the matched cohort and weighted cohort, the hypothermia group had a higher 180-day mortality than the no hypothermia group (Table 2, P < 0.001). After adjustment, logistic regression in the primary cohort showed that hypothermia was associated with a higher 180-day mortality rate, with an OR of 2.82 (95% CI, 2.47–3.21, P < 0.001). This association remained significant in the matched cohort (OR, 1.66, 95% CI, 1.38–2.00, P < 0.001) and in the weighted cohort (OR, 1.78, 95% CI, 1.54–2.04, P < 0.001) (Figure S2). In the original cohort, Kaplan-Meier curve analysis showed that the 180-day mortality of the hypothermia group was significantly higher than that of the no hypothermia group (Fig. 3A, P < 0.001). This result remained significant in the matched cohort (Fig. 3B, P < 0.001) and in the weighted cohort (Fig. 3C, P < 0.001).

In the matched cohort, the hypothermia group had a higher 180-day mortality than the no hypothermia group [526 (56.7%) vs. 395 (42.6%), P < 0.001] (Table 2). After adjustment, logistic regression in the primary cohort showed that hypothermia was associated with a higher 360-day mortality rate in both cohorts (Figure S3). In the original cohort, Kaplan-Meier curve analysis showed that the 360-day mortality of the hypothermia group was significantly higher than that of the no hypothermia group (Figure S4A, P < 0.001). This result remained significant in the matched cohort (Figure S4B, P < 0.001) and in the weighted cohort (Figure S4C, P < 0.001).

The Mann-Whitney U test showed that the hypothermia group had a longer ICU LOS [3.61 (2.02, 6.99) vs. 3.04 (1.81, 6.16) d, P < 0.001] than the no hypothermia group in the original cohort. In the matched cohort and weighted cohort, there were no significant difference in length of hospital stay between the two groups (P > 0.05) (Table 2). The chi-square test showed that the hypothermia group had a higher in-hospital mortality (P < 0.001) than the no hypothermia group in the original cohort. In the matched cohort and weighted cohort, the hypothermia group had a higher in-hospital mortality than the no hypothermia group (P < 0.001, Table 2). After adjustment, logistic regression in the original cohort showed that hypothermia was associated with a higher hospital mortality rate, with an odds ratio (OR) of 3.36 (95% CI, 2.92–3.87, P < 0.001). This association remained significant in the matched cohort (OR, 1.87, 95% CI, 1.53–2.30, P < 0.001) and in the weighted cohort (OR, 1.87, 95% CI, 1.61–2.19, P < 0.001) (Figure S5).

Discussion

This study explored, to the best of our knowledge, the link between hypothermia on the first day of admission and all-cause mortality of ICU patients with sepsis. We confirmed that hypothermia is an independent risk factor for mortality at 180-day and 360-day in individuals with sepsis. In addition, we observed a substantial association between hypothermia and in-hospital mortality in sepsis patients.

BT is a widely monitored vital sign in the emergency room and on the wards, and abnormalities in BT are among the most often observed symptoms in critically ill patients8. In addition, these abnormalities typically result in modifications to the treatment plan for the patient20. In critically ill patients, hypothermia, rather than hyperthermia, can disguise symptoms of deteriorating disease, making it more difficult for doctors to notice them. This, in turn, can lead to delays in treatment, which can worsen outcomes. Abnormal BT involves both hyperthermia and hypothermia. As systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criterion for hypothermia, a BT less than 36 °C is a widely accepted number21. Despite the fact that Sepsis-3 abandoned the SIRS criteria, which included BT, for evaluating sepsis patients, BT may have clinical or prognostic implications in these patients2.

Hypothermia has been related with an increased risk of mortality in septic patients, according to some research. Compared to hyperthermia, normothermia was substantially related with increased in-hospital mortality, as revealed by a retrospective, multicenter observational analysis22. Hypothermia was linked with greater in-mortality in both the matched cohort and the weighted cohort, according to our analysis. Moreover, a second retrospective, multicenter observational study indicated that hypothermia may enhance the efficacy of rapid Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) to predict 28-day mortality in sepsis patients23. However, past studies have mostly focused on the association between hypothermia and short-term outcomes and have seldom investigated the association between hypothermia and long-term outcomes in patients with sepsis.

In the current study, the incidence of mortality among patients with hypothermia within 24 h after ICU admission was 4.8% (937/19636), and the 180-day and 360-day mortality rates were similarly significantly higher compared to those of other patients. The physiology and development of hypothermia are complex; nevertheless, an overactive anti-inflammatory response and enhanced immunosuppression may be associated with the increased prevalence of hypothermia in septic patients9,24,25. Excessive anti-inflammatory responses have a tendency to deplete proinflammatory cytokines, in particular interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), which are the primary mediators of fever26,27. Immunosuppression is the primary hallmark of the progression of sepsis, which is primarily characterized by a reduction in the number of immune cells in the body14. Moreover, hypothermia may reduce the suppression of pathogenic microorganisms. This is because a moderate fever directly inhibits the reproduction of many viruses and bacteria, which are common causes of life-threatening diseases, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and the novel coronavirus. Fatteh et al.28 pointed out that in patients infected with the novel coronavirus, the mortality risk of those with hypothermia is 2.06 times higher than that of patients without hypothermia.

In addition to the findings of this study, it is important to acknowledge the heterogeneity within the sepsis population. Patients with different sources of infection may respond differently to hypothermia, and this variability could influence outcomes. While our analysis focused on the overall cohort, the potential impact of infection source on the relationship between hypothermia and mortality warrants further investigation. Future research should aim to explore how different subgroups, based on infection etiology, might demonstrate varying responses to hypothermia. This would provide a more nuanced understanding of the role of temperature management in septic patients29. Furthermore, while our study identified an association between hypothermia and mortality, the question of causality remains unanswered. To strengthen causal inferences, it would be beneficial to explore the relationship using more advanced statistical methods, such as target trial emulation. This approach could help replicate the causal framework of a randomized controlled trial, offering a more reliable estimation of the treatment effect. We acknowledge that such methods could provide valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms of hypothermia and its impact on patient outcomes. Future studies incorporating these techniques will be crucial in advancing our understanding of the causal relationship between hypothermia and mortality in sepsis30.

Despite the significance of our findings, numerous limitations should be acknowledged. Due to the retrospective study design, it was unable to eliminate selection bias. The PSM and IPTW methods were utilized to ensure the reliability of our results. Second, we removed patients who had missing body temperature data without imputing them. This omission may have an effect on the underlying relationship between hypothermia and mortality. In addition, some additional variables, such as lactate, which played crucial roles in determining the severity of disease were unavailable due to an overwhelming number of missing values. Furthermore, a limitation of this study is the lack of detailed information regarding the specific method and site of temperature measurement, which may introduce systematic bias, particularly since a fixed threshold of 36℃ was used. Lastly, the potential impact of interventions, such as the use of warming devices, on outcomes was not explicitly considered. Finally, due to the limitation of sample size and the need to ensure balance in intergroup comparisons, patients with a body temperature > 38℃ were excluded, which may lead to selection bias. Future research should consider addressing this potential limitation to provide a more comprehensive understanding of sepsis across all temperature ranges.

In conclusion, hypothermia was associated with increased in-hospital and all-cause mortality in septic patients, emphasizing the significance of temperature protection in the ICU.

Data availability

The datasets given in this investigation are accessible through the MIMIC IV database (https://www.physionet.org/content/mimiciv/3.1/).

Abbreviations

- MIMIC-IV:

-

Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV

- PSM:

-

propensity score matching

- IPTW:

-

inverse probability of treatment weighting

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- BT:

-

body temperature

- SQL:

-

Structured Query Language

- HR:

-

heart rate

- RR:

-

respiratory rate

- SBP:

-

systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

diastolic blood pressure

- SpO2 :

-

saturation of pulse oxygen

- Glu:

-

blood glucose

- HCT:

-

haematocrit

- HGB:

-

haemoglobin

- PLT:

-

platelet counts

- WBC:

-

white blood cell count

- AG:

-

anion gap

- BUN:

-

blood urea nitrogen

- Cr:

-

creatinine

- INR:

-

international normalized ratio

- PT:

-

prothrombin time

- PTT:

-

partial thromboplastin time

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- SAPS II:

-

Simplified Acute Physiology Score II

- MI:

-

myocardial infarction

- CHF:

-

congestive heart failure

- COPD:

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- AIDS:

-

acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- CRRT:

-

continuous renal replacement therapy

- ECMO:

-

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- LOS:

-

length of stay

- SMD:

-

standardized mean differences

- SIRS:

-

systemic inflammatory response syndrome

References

Rhodes, A. et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 43 (3), 304–377 (2017).

Singer, M. et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315 (8), 801–810 (2016).

Asiimwe, S. B., Abdallah, A. & Ssekitoleko, R. A simple prognostic index based on admission vital signs data among patients with sepsis in a resource-limited setting. Crit. Care. 19, 86 (2015).

Shimazui, T. et al. Significance of body temperature in elderly patients with sepsis. Crit. Care. 24 (1), 387 (2020).

Andrews, B. et al. Effect of an early resuscitation protocol on In-hospital mortality among adults with sepsis and hypotension: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 318 (13), 1233–1240 (2017).

Schelonka, R. L. et al. Mortality and neurodevelopmental outcomes in the heart rate characteristics monitoring randomized controlled trial. J. Pediatr. 219, 48–53 (2020).

Drewry, A. & Mohr, N. M. Temperature management in the ICU. Crit. Care Med. 50 (7), 1138–1147 (2022).

Kushimoto, S. et al. The impact of body temperature abnormalities on the disease severity and outcome in patients with severe sepsis: an analysis from a multicenter, prospective survey of severe sepsis. Crit. Care. 17 (6), R271 (2013).

Drewry, A. M., Fuller, B. M., Skrupky, L. P. & Hotchkiss, R. S. The presence of hypothermia within 24 hours of sepsis diagnosis predicts persistent lymphopenia. Crit. Care Med. 43 (6), 1165–1169 (2015).

Evans, S. S., Repasky, E. A. & Fisher, D. T. Fever and the thermal regulation of immunity: the immune system feels the heat. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15 (6), 335–349 (2015).

Rubio, I. et al. Current gaps in sepsis immunology: new opportunities for translational research. Lancet Infect. Dis. 19 (12), e422–e436 (2019).

Nakamori, Y., Park, E. J. & Shimaoka, M. Immune deregulation in sepsis and septic shock: reversing immune paralysis by targeting PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. Front. Immunol. 11, 624279 (2020).

van der Poll, T., van de Veerdonk, F. L., Scicluna, B. P. & Netea, M. G. The immunopathology of sepsis and potential therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17 (7), 407–420 (2017).

Venet, F. & Monneret, G. Advances in the Understanding and treatment of sepsis-induced immunosuppression. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 14 (2), 121–137 (2018).

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data. 10 (1), 1 (2023).

Ryan, B. M. In response: using propensity score matching to balance the baseline characteristics. J. Thorac. Oncol. 16 (6), E46–E46 (2021).

Narduzzi, S., Golini, M. N., Porta, D., Stafoggia, M. & Forastiere, F. [Inverse probability weighting (IPW) for evaluating and correcting selection bias]. Epidemiol. Prev. 38 (5), 335–341 (2014).

Austin, P. C. & Stuart, E. A. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat. Med. 34 (28), 3661–3679 (2015).

Austin, P. C. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat. Med. 28 (25), 3083–3107 (2009).

O’Grady, N. P. et al. Guidelines for evaluation of new fever in critically ill adult patients: 2008 update from the American college of critical care medicine and the infectious diseases society of America. Crit. Care Med. 36 (4), 1330–1349 (2008).

Bone, R. C. et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest, 101(6): 1644–1655. (1992).

Park, S. et al. Normothermia in patients with sepsis who present to emergency departments is associated with low compliance with sepsis bundles and increased In-Hospital mortality rate. Crit. Care Med. 48 (10), 1462–1470 (2020).

Kushimoto, S. et al. Complementary role of hypothermia identification to the quick sequential organ failure assessment score in predicting patients with sepsis at high risk of mortality: A retrospective analysis from a Multicenter, observational study. J. Intensive Care Med. 35 (5), 502–510 (2020).

Baek, M. S., Kim, J. H. & Kwon, Y. S. Cluster analysis integrating age and body temperature for mortality in patients with sepsis: a multicenter retrospective study. Sci. Rep. 12 (1), 1090 (2022).

Thomas-Rüddel, D. O. et al. Fever and hypothermia represent two populations of sepsis patients and are associated with outside temperature. Crit. Care. 25 (1), 368 (2021).

Bibby, D. C. & Grimble, R. F. Temperature and metabolic changes in rats after various doses of tumour necrosis factor alpha. J. Physiol. 410, 367–380 (1989).

Yi, W. et al. Effect of temperature stress on gut-brain axis in mice: regulation of intestinal Microbiome and central NLRP3 inflammasomes. Sci. Total Environ. 772, 144568 (2021).

Fatteh, N. et al. Association of hypothermia with increased mortality rate in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 108, 167–170 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. Hongying Ni, Zhongheng zhang: identification of clinical subphenotypes of sepsis after laparoscopic surgery. Laparosc. Endoscopic Robotic Surg. 7 (1), 16–26 (2024).

Jie Yang, L. et al. Zhongheng zhang: A comprehensive step-by-step approach for the implementation of target trial emulation: evaluating fluid resuscitation strategies in post-laparoscopic septic shock as an example, laparoscopic. Endoscopic Robotic Surg. 8 (1), 28–44 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yongmei Yang conceptualized the research aims, planned the analyses and guided the literature review. Wenyuan Zhang extracted the data from the MIMIC-IV database. Jinmin Chen and Wenyuan Zhang participated in processing the data and doing the statistical analysis. Jinmin Chen wrote the first draft of the paper and the other authors provided comments and approved the final manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. Additionally, the use of the MIMIC-IV database was approved by both the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. The datasets utilized in this research can be accessed through the MIMIC database.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, J., Zhang, W. & Yang, Y. Hypothermia association with all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis based on the MIMIC-IV database. Sci Rep 15, 44902 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29166-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29166-0