Abstract

The paradoxical nature of stress lies in its ability to both enhance and hinder psychological, physiological, and cognitive functioning. While chronic stress impairs functioning, acute stress can enhance resilience, cognition, and performance. We examined whether intentional short-term stress induced by cyclic hyperventilation and cold exposure (the Wim Hof Method (WHM)) improves psychophysiological and cognitive outcomes compared to an active control (mindfulness meditation). In this semi-randomised controlled trial, healthy adults (N = 404; 226 females, 177 males, 1 other; mean age = 37) completed one of three 29-day interventions: WHM in-person, WHM-remote, or meditation. Measures included physiological and sleep biometrics, executive function tests, and psychometric event sampling surveys (state and trait change). WHM conditions showed greater momentary improvements in self-reported energy, mental clarity, and ability to handle stress following daily protocol compared with meditation. Although WHM protocols initially resulted in smaller reductions in self-reported state stress, their impact increased across days on protocol, while the impact of meditation decreased. A similar time-condition interaction was also observed for energy, mental clarity, and ability to handle stress, suggesting cumulative, dose-dependent benefits. While minimal significant between-condition trait changes emerged over 29-days, state interaction patterns suggest potential for longer-term state–trait shifts. Executive function, physiological, and sleep results showed nuanced between-condition differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While acute, controlled exposure to moderate stressors can enhance resilience, vitality, and performance, high or chronic doses can be detrimental1,2,3,4. Chronic stress has been shown to not only degrade psychological and physiological functioning but also increase health risks such as burnout5,6. Given this duality of stress, along with the rising prevalence and cost of burnout and other stress-related illnesses7, current approaches to stress management, which typically focus on stress avoidance, reduction8, or changing one’s mindset or appraisals of stress9,10, may be missing a crucial aspect. Specifically, the strategic utilisation of acute stress to optimise psychological, physiological and cognitive functioning.

The Wim Hof Method® (WHM) has gained significant attention in recent years as a potential approach to enhancing well-being in a number of domains. The method consists of three pillars: (1) short, controlled bouts of cyclic hyperventilation, (2) brief, controlled cold exposure, and (3) maintaining a “commitment mindset” (i.e., patience and dedication to explore and master the techniques11). Together, these practices increase autonomic nervous system activation (e.g., acute stress response), with emerging evidence supporting a range of physiological and psychological benefits, such as improvements in immune function12,13,14, and reductions in symptoms of depression15, and perceived stress16. In addition to a vast literature supporting the benefits of cold exposure17 and breathwork practices in isolation18,19, recent findings suggest these practices may be even more effective when combined, as in the WHM (e.g., for reducing perceptions of stress16).

Despite promising results, methodological constraints limit the early evidence for WHM’s efficacy, including small sample sizes, a lack of active control conditions, absence of pre-registered published protocols, and predominantly subjective markers (detailed in 12). Recent investigations have revealed mixed results, with some studies finding no positive effects of these practices on cardiovascular or psychological health20. These inconsistencies may stem from variability across methods, protocols, dosages, and theoretical framework guiding research questions and outcome measures.

On the other hand, WHM appears to be particularly beneficial for stress and inflammatory response categories12. While not a cure-all, repeated practice of the WHM (cold exposure and hypoxia induced by cyclic hyperventilation) may inoculate against chronic stress through the dose-dependent stress response (also known as hormesis2,21. Specifically, low to moderate (usually intermittent) doses of certain stressors (e.g., “microdosing” stress) can trigger adaptive responses and promote resilience and improved health outcomes, while high or chronic doses are detrimental22. This process of hormesis is broadly applicable, being observed across cells, systems, plants, and humans21,22 and may explain how WHM practices impact stress-related outcomes.

We also propose that repeated practice of the WHM may help specifically to recalibrate metacognitive beliefs about the capacity to effectively anticipate, adapt to, and recover from stress. Allostasis refers to the processes by which the brain anticipates and adapts to changing conditions (including stressors) to maintain stability through change5. Allostatic processes involve the production of stress mediators, such as adrenaline and cortisol, in response to anticipated challenges5. While these mediators are crucial for promoting adaptation to acute stress, chronic or prolonged activation of the body’s stress response systems can lead to allostatic overload (i.e., wear and tear) on various physiological systems, increasing one’s risk of health problems5. Chronic dyshomeostasis (e.g., prolonged stress) can also foster implicit beliefs that one is ineffective at regulating stress responses. This belief is theorised to diminish subjective wellbeing, manifesting as increased fatigue and depressive symptoms23. Frequent intentional exposure to and recovery from short-term stress, such as that elicited by acute cold exposure and hypoxia induced by cyclic hyperventilation, may help adjust expectations about allostatic regulation. By overcoming default stress reduction strategies (e.g., avoiding or fleeing from the source of stress), intentional practice of the WHM may be encoded by the brain as experiences of successfully overcoming stress, adjusting the brain’s expectations about allostatic self-efficacy, and the range (or boundary conditions) of stress that one can cope with and recover from.

Repeated intentional hormetic stress, as practised in WHM, may facilitate recalibration of the brain’s expectations about stress and thus lead to improved stress resilience and allostatic self-efficacy over time. Guided by this framework, the present study employs a semi-randomised controlled trial with a large sample size, an active control condition, event sampling methodology (ESM), physiological biometric capture, and online cognitive testing to examine the effects of the WHM on psychological, physiological, and cognitive functioning.

WHM has previously been linked to reduced inflammation and improvements in energy, fatigue, and breathing12, suggesting it may also influence physiological regulation (e.g., allostasis24,25). To better understand the physiological effects of the WHM, we also included objective metrics that reflect autonomic recovery and sleep processes. We assessed heart rate variability (HRV), resting heart rate, respiratory rate, and sleep architecture (slow wave sleep (SWS), rapid eye movement (REM)) to supplement self-report data and detect changes outside of conscious awareness. This extends previous research19 by evaluating the full WHM protocol, including breathing and cold exposure, over a longer intervention period.

Methods

Ethics & OSF

This study received ethical approval from the Human Ethics Sub-Committee at the University of Queensland (ID: 2023/HE000736). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. All study protocols, hypotheses, data collection procedures, and planned analyses were pre-registered prospectively on the Open Science Framework (OSF; see https://osf.io/mdwpq; registered 25/07/2023). This study was also registered as a clinical trial with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN; ACTRN12623000913673; registered 25/08/2023). Deviations from our pre-registration (OSF) and retrospective ANZCTR registration are detailed at the end of the methods section (see Deviations from Pre-registration).

Recruitment

Participants were recruited across Australia and New Zealand via three channels: (a) targeted LinkedIn advertisements, (b) outreach to existing biometric capture device users (WHOOP Inc), and (c) internal emails to PricewaterhouseCoopers employees (Australia only). Participants were allocated to one of three semi-randomised conditions (WHM in-person, WHM-remote, or meditation control). WHM in-person recruitment was restricted to the Sydney Central Business District in Australia, as their intervention protocol required them to attend local weekly group icebaths. The WHM-remote and meditation conditions were recruited from existing users of the biometric capture device (WHOOP strap 4.0; Boston, USA) in Australia and New Zealand. A research member first ranked these participants by their local average August temperature and randomly assigned them to either the WHM-remote or meditation condition via location-stratified, computer-generated sequential numbering to balance temperatures between conditions. The 29-day intervention phase was conducted in August to coincide with winter in the Southern Hemisphere, to ensure convenient and free access to a daily cold immersion (i.e., showers). Due to the nature of the interventions, participants were not blinded to their condition.

Eligible participants were 18 years or older, English-speaking, located in Australia or New Zealand during the 29-day intervention period, residing in a city with a maximum August mean temperature of 22 °C, not currently engaging in or with extensive previous experience of any breathwork, meditation, or cold immersion practices, and free from medical conditions that could impact their health or safety during the interventions (e.g., heart disease, hypertension, respiratory difficulties, glaucoma, seizures, diabetes, pregnancy, psychosis, suicidal ideation, bipolar disorder, substance use disorders, severe vision, or hearing impairments).

Procedure

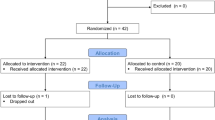

Participants underwent five phases of testing: (1) onboarding (days -14 to -8), (2) baseline (days -7 to 0), (3) intervention (days 1 to 29), (4) offboarding (day 30), and (5) monthly follow-ups (days 31 to 119; see Fig. 1). They completed a 10–15-min survey at onboarding and offboarding, with links open for one week. During the baseline phase, participants completed a daily survey and online executive function tasks (counterbalanced Stroop Task or N-back Task; not reported in this paper) for seven consecutive days. Baseline surveys were sent at 4:00 am Australian Eastern Standard Time (AEST) via a Qualtrics survey link to participants’ biometric capture smartphone app, with instructions to complete the survey before starting their daily routine.

During the intervention phase, participants completed the following daily tasks: (1) a pre-intervention survey, (2) the intervention protocol, and (3) a post-intervention survey and online executive function task (Stroop Task or N-back Task) for 29 consecutive days. Intervention surveys and protocols were sent at 4:00 am AEST, with participants requested to complete them in the morning before work or exercise. Links remained open, with executive function task presentations alternating every 24 h. In the monthly follow-up phase, participants completed the same baseline/offboarding survey once a month for three consecutive months. Participants were asked to wear their wrist-worn biometric capture devices continuously for the duration of the study.

In-person study induction sessions were provided for the WHM condition, and online inductions for the WHM-remote and meditation conditions. These sessions offered guided instruction on the daily intervention activity (breathwork and cold immersion or meditation) by qualified instructors (Certified Wim Hof Method and Mindfulness instructors) and all necessary resources (e.g., instructions, study timeline). To incentivise compliance and ensure accurate implementation of the daily intervention activities, condition-specific weekly online Q&A sessions with the instructors and research team were hosted. Participants were advised to maintain their regular routines and refrain from participating in the intervention activities not assigned to them. After the intervention phase, an online information session was held to thank participants and provide details regarding the monthly follow-ups. At study completion, participants received a debrief pack with the intervention resources and instructions for the condition they were not assigned, if they wished to try it.

Figure 1 above depicts the overall timeline of the study, including recruitment, enrolment, onboarding, baseline, intervention, offboarding, and follow-up phases.

Participants

The pre-registered sample size target was 745 participants; however, fewer participants were recruited due to the limited availability of eligible individuals who met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and resided in Australian or New Zealand cities with a maximum August mean temperature of 22 °C. A total of 556 participants enrolled in the study, with a final sample size of 404 participants (226 females, 177 males, and 1 identifying as “other”). Attrition was due to a medical condition (1), travel, and conflicting time commitments. Based on power calculations for intensive longitudinal models, a sample size of 125 participants per condition was deemed adequate to achieve 80% power26 and is consistent with the ability to detect small to moderate effect sizes in similar multilevel designs. Participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 65 years (M = 37, SD = 9.95). Most participants were in Australia during the intervention period (376, 93.07%), with the remaining 28 (6.93%) located in New Zealand. The average winter temperature for the intervention month of August was 17.24 °C (SD = 2.53), comparable across participants’ locations for all conditions (see Table 1). Compliance rates were 94.32% for the biometric capture device (sleep and physiological metrics), 89% for the baseline surveys, 64.71% for the daily intervention and survey, and compliance ranged from 58.42% to 62.16% for the intervention executive function Stroop Task and N-back Task, respectively. See Table 1 for within-condition participant descriptives.

Materials

Onboarding & exit survey measures

The surveys contained eight scales, items randomised and adapted to reflect only the last seven days. The internal consistency was assessed using the coefficient omega (ω) from the omegaSEM function of the multilevelTools package in R27, with higher scores (0–1) indicating higher internal consistency as with Cronbach’s alpha28. In the onboarding survey participants reported their age, sex, and whether they considered themselves knowledge workers in their current profession. To investigate sustained post-study effects, participants completed monthly follow-up surveys for three months, containing the same eight scales as the onboarding and exit surveys. Note: Psychological Wellbeing Scale (PWB-1829) was measured but excluded from analyses due to data collection errors.

Depression anxiety and stress scale (DASS-21)

The DASS scale30 consisted of 21 statements, with seven items per subscale, which measure negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress. Scores are presented as a total score and a score for the three subscales as per scale scoring instructions, with higher scores indicating higher severity. The DASS-21 demonstrated excellent internal consistency at onboarding (ω = 0.91) and exit (ω = 0.90). The subscales also showed good to acceptable internal consistency: Depression (onboarding ω = 0.86; exit ω = 0.83), Anxiety (onboarding ω = 0.77; exit ω = 0.74), and Stress (onboarding ω = 0.84; exit ω = 0.83).

Mini sleep questionnaire (MSQ)

The 10-item MSQ31 measures two dimensions of sleep: insomnia and hyperinsomnia. For the study, we made the following changes to the scale, resulting in a modified 9-item scale: (1) Item 6, “Snoring”, was removed, (2) Item 10, “Excessive movement during sleep”, was replaced with “Excessive restlessness in bed”, and (3) Item 3, “Hypnotic medication”, use was replaced with “Use of prescription or non-prescription sleep medication (including melatonin)”. The first two modifications were made because the participant could not easily answer them without consulting a sleeping partner (if applicable). The third modification was made to make the item more generalisable. Participants were asked to rate the frequency of each sleep event over the past seven days on a scale of 1 (never) to 7 (always). The MSQ demonstrated good internal consistency at onboarding (ω = 0.78) and exit (ω = 0.79).

Multidimensional daily fatigue (MDF-fibro-17)

The 17-item MDF-fibro-1732 measures the different components of fibromyalgia-related fatigue symptoms. The scale has 5 subscales, including (1) Global Fatigue experience, (2) Physical Fatigue, (3) Cognitive Fatigue, (4) Motivation, and (5) Impact on Function. Participants were asked to rate the 17 items reflecting on the last seven days on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely). Higher subscale scores indicated greater fatigue severity. The MDF-fibro-17 demonstrated excellent internal consistency at onboarding (ω = 0.97) and exit (ω = 0.97). The subscales also showed good to excellent internal consistency: Global Fatigue Experience (onboarding ω = 0.92; exit ω = 0.90), Physical Fatigue (onboarding ω = 0.87; exit ω = 0.84,), Cognitive Fatigue (onboarding ω = 0.92; exit ω = 0.92), Motivation (onboarding ω = 0.90; exit ω = 0.90), and Impact on Functioning (onboarding ω = 0.91; exit ω = 0.92).

Multidimensional assessment of interoceptive awareness (MAIA-2)

The MAIA-233 is an 8-scale state-trait questionnaire that measures eight dimensions of interoception by self-report, including Noticing, Not Distracting, Not Worrying, Attention Regulation, Emotional Awareness, Self-regulation, Body Listening, and Trusting. Participants were asked to rate how often the 37 statements apply to them in daily life on a scale of 0 (never) to 6 (always). Scores are presented as a total score and a score for the eight subscales. Higher scores indicate higher interoceptive sensitivity. The MAIA-2 demonstrated good internal consistency across subscales: Noticing (onboarding ω = 0.75; exit ω = 0.72), Not-Distracting (onboarding ω = 0.78; exit ω = 0.80), Not-Worrying (onboarding ω = 0.76; exit ω = 0.77), Attention Regulation (onboarding ω = 0.87; exit ω = 0.87), Emotional Awareness (onboarding ω = 0.77; exit ω = 0.77), Self-Regulation (onboarding ω = 0.82; exit ω = 0.82), Body Listening (onboarding ω = 0.77; exit ω = 0.80), and Trusting (onboarding ω = 0.76; exit ω = 0.74).

Stress mindset measure (SMM)

The SMM9 is an 8-item scale, designed to assess the extent to which an individual believes that the effects of stress are either enhancing or debilitating. Participants rate how strongly they agree or disagree on a scale of 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). The Stress Mindset Measure demonstrated good internal consistency at onboarding (ω = 0.85) and exit (ω = 0.89).

Frustration discomfort scale (FDS)

The FDS34 is a 14-item scale designed to assess the strength of common thoughts and beliefs about distress and frustration. Of the four subscales, we included two. The first was the Discomfort Intolerance subscale, intolerance of difficulties or hassles. The second was the Emotional Intolerance subscale, intolerance of emotional distress. Participants indicate the strength of their belief in each statement on a 0 (absent) to 4 (very strong). The two FDS demonstrated excellent internal consistency at onboarding (ω = 0.90) and exit (ω = 0.91). Subscale reliabilities were good: Discomfort Intolerance (onboarding ω = 0.88; exit ω = 0.89), and Emotional Intolerance (onboarding ω = 0.86; exit ω = 0.87).

Psychological safety

We included a 10-item version of the Psychological Safety Scale35, which was adapted to measure the degree of psychological safety an individual feels within their direct work team environment36. Participants were asked to reflect on the past 7 days when answering the stem “In the interactions with your direct work team last week, if needed, did you feel comfortable to…” with an example item “Bring up problems and tough issues”. Responses were made on a 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) scale. This scale was presented as part of a branched response if participants answered ‘yes’ to the question, “If you are currently employed right now, do you work within a direct team in your job?”. The Psychological Safety measure demonstrated good internal consistency at onboarding (ω = 0.89) and excellent internal consistency at exit (ω = 0.91).

Physiology and sleep

We used the continuous biometric capture device (WHOOP strap 4.0; Boston, USA) to collect key sleep and physiological metrics, including sleep quantity, slow wave sleep (SWS), rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, heart rate variability (HRV), resting heart rate, and respiratory rate. The wrist-worn device integrates an accelerometer, gyroscope, and an optical heart rate sensor that measures blood flow and changes in blood volume to calculate heart rate. Proprietary algorithms process the raw RR-intervals collected from the heart rate sensor during sleep without user input to derive sleep and heart rate metrics. The device has been shown to provide valid measures of heart rate, HRV, and sleep quantity (very low precision errors and bias) in comparison to gold-standard measures of electrocardiogram and polysomnography37,38; Note: Berryhill’s validation study on the WHOOP device37 was funded by a grant to the University of Arizona from WHOOP Inc., and Miller’s38 research group at Central Queensland University receives funding support from WHOOP Inc). However, the accuracy for identifying sleep stage (i.e., REM and SWS) is more moderate38, indicating that while the WHOOP device is validated for field-based assessment of sleep quantity and cardiovascular metrics, further improvement is necessary for assessing specific sleep stages (e.g., SWS, REM).

Cardiovascular metrics

Heart rate variability (RMSSD) and resting heart rate (beats per minute) are calculated as the average over the nightly sleep period. The device has shown excellent intraclass correlation (0.99) in comparison to electrocardiogram-derived heart rate and HRV38. To our knowledge research has not validated WHOOP’s HRV algorithm directly, though it has confirmed the reliability of its raw heart rate data, from which their HRV metric was calculated38.

Unfortunately, WHOOP’s proprietary HRV algorithm prevented independent calculation of HRV metrics from the raw RR-interval data or verification of the device’s data processing methods, including artifact handling (e.g., ectopic beats or arrhythmias), filtering, or time windows for calculation. Nevertheless, RMSSD-derived HRV is a widely accepted measure of parasympathetic activation39,40 and is considered the most appropriate HRV metric for field research41, with applications in self-regulation42 and stress arousal research43.

Respiratory rate

Respiratory rate, measured as breaths per minute, was calculated by the device as the average number of respirations during the nightly sleep period using the device’s heart rate data. The device’s respiratory rate measurement has been validated against polysomnography, demonstrating low bias (1.8%) and precision error 6.7%37. Respiratory rate serves as a key indicator of respiratory health and metabolic activity44.

Sleep quantity

Sleep quantity represents the total time (in minutes) spent asleep each night, automatically detected by the device without the need for user input. Validation studies demonstrated an 86% correct identification of sleep/wake epochs, with a moderate level of agreement (kappa value of 0.44), when compared to polysomnography38.

Slow wave sleep

SWS represents the total time (in minutes) spent in deep sleep per night. The device’s multi-stage sleep stage categorisation exhibited 60% accuracy (kappa value of 0.44) compared to gold standard polysomnography38.

Rapid eye movement sleep

REM sleep represents the total time (in minutes) spent in REM sleep stages. Similarly to SWS, the device’s assessment of multi-stage sleep showed an accuracy of 66%, with a kappa value of 0.44, indicating moderate agreement when compared to polysomnography38. REM sleep is when most dreams occur and is characterised by rapid movements of the eyes, vivid dreaming, and increased brain activity45.

Momentary self-report items

Participants rated their momentary “energy”, “mental clarity”, “anxiety”, “stress”, and “ability to handle stress”, on a sliding scale from 0 (very low) to 10 (very high). Participants were provided with the stem, “Reflecting on how you feel right at this moment, please rate the following”, followed by each of the five items. These items were presented once daily in the baseline survey and before and after the daily intervention in the intervention surveys, with presentation order randomised.

Executive function test

We used two brief online versions of the Stroop Colour and Word Test46 and the N-back Test47 programmed and used by the research team36 for completion on a computer or smartphone. The N-back and Stroop tasks are generated and run completely online using a combination of Html, CSS, and JavaScript. To mitigate potential latency effects due to changing network conditions, the experiment pre-loaded all required resources before the tasks started. No network activity is required during the tasks except to save the results, which is done asynchronously in the background. Stimulus presentation was controlled using JavaScript’s ‘requestAnimationFrame’ for precise frame synchronisation at 60 Hz, ensuring consistent and smooth display timing.

Online stroop task

Participants accessed the task via a Qualtrics link embedded in the daily survey. Before starting the task, written instructions with visual representations of correct and incorrect responses were provided. Each trial began with a central fixation cross presented for random intervals of 800 ms, 1000 ms, or 1100 ms, followed by the first stimulus presentation. The stimuli consisted of four colour words (RED, GREEN, YELLOW, BLUE) written in either yellow, green, blue, or red ink, presented on a black background. The stimuli remained on the screen until a button press response was made or for 3000 milliseconds (ms), whichever came first. Each trial was preceded by a blank interstimulus interval of 250 ms. Stimuli size varied by word length (e.g., the word BLUE covered 40% of the screen width and the word YELLOW 70%). The one block of 24 trials consisted of 50% congruent trials (i.e., the written colour word and ink match) and 50% incongruent trials (i.e., the written word and ink do not match), with presentation order randomised throughout the block. Participants made a response by pressing one of the four coloured circles at the bottom of the screen (red, green, blue, yellow), with the stimuli disappearing after a response was given. Immediate feedback was provided, a green tick for correct responses and a red cross for incorrect or timed-out responses, which were displayed for 1000 ms.

Online N-back task

Written instructions and visual examples of correct and incorrect 2-back responses were provided to participants before commencing the task. They were informed about the in-task feedback they would receive and were requested to respond as quickly as possible. Each trial began with the 1250 ms presentation of the first stimuli (stimulus delay) followed by a 250 ms blank interstimulus interval. Participants responded to a target by touching the stimuli presented on the screen if they had seen the same stimuli two times before. Post-trial feedback appeared under each presented stimulus for 250 ms (e.g., green tick for correct responses, red cross for incorrect or timed-out responses). The screen was scaled to 800 pixels wide (irrespective of screen size), and stimuli were 300 pixels wide, taking up 35% of the screen width, with stimulus size dependent on participants’ screen size. Instructions for the 3-back trial followed the completion of the 2-back trial. To help increase effort and motivation and minimise recognition based on perceptual features, our N-back task contained novel visual stimuli to ensure a variety of shapes and colours. Indeed, gamification of online N-back tasks has been found to increase effort and motivation without impacting task performance and cognitive load48.

See Fig. 2, below, for an overview of all data streams collected.

Intervention protocols

Participants were instructed to complete their daily study participation before starting their day (i.e., in the morning before exercise or work). Daily study participation time ranged between 20 to 23 min and included (1) a pre-intervention survey, (2) intervention protocol, (3) a post-intervention survey, and (4) executive function task (Stroop or N-back). Before the intervention phase, participants underwent an online training session tailored to their assigned intervention protocol, which we conducted with the certified WHM instructor or the meditation instructor. Note: Certified Wim Hof Method instructors undergo comprehensive online and in-person training in physiology, breathing, cold exposure, mindset, and instructional techniques. To maintain certification, they must pass an annual examination. Certified meditation instructor completed formal training in mindfulness and meditation training and facilitation through accredited programs. Certification is supported by formal coursework and practical experience under qualified supervision.

Weekly intervention-specific Zoom sessions with the instructors were held to address participant inquiries or provide further guidance on the protocols. Daily intervention surveys collected data on participants’ adherence to the intervention, including the duration of participation in the breathwork exercises, see Fig. 1 for the daily protocol.

Breathwork cold immersion conditions

Breathwork protocol

Participants engaged in a daily breathwork protocol that included controlled hyperventilation followed by breath retention. The breathwork exercises were guided by a video created by Wim Hof, which followed established WHM breathing and retention techniques. In the daily survey link, participants were provided with written breathwork instructions and were asked to familiarise themselves with them before starting the 15-min pre-recorded guided breathwork video. The written instructions asked participants to lie down flat with their legs bent at the knees and legs and arms uncrossed or to sit in a meditation posture if that was more comfortable. They were asked to inhale deeply through the nose (or mouth, if required) and exhale without force through the mouth. Fully inhale to the belly and the chest, and exhale without force, without pause 30 times. After the 30 deep breaths, they were asked to draw the breath in once more and fill the lungs to maximum capacity without forcing it. Then, let the air out again and hold it for the duration of the video timer or until they feel the urge to breathe again. When the breath hold timer was up (or when they felt the urge to breathe again), they were asked to then draw one breath to full capacity. At full lung capacity, they were asked to then hold their breath for 15 seconds (s). Participants completed four consecutive rounds, with each round involving a progressive increase in the duration of the exhaled breath holds: 1 min, 1 min and 30 s, another 1 min and 30 s, and finally 2 min. The guided breathwork video guided the breathing pace and timing of breath holds and rounds. The study’s guided breathwork is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cuxppurd-tw.

Participants were trained in the breathwork component during the online onboarding seminars, which were facilitated by certified WHM instructors. Both in training and in the instructions of their daily ESM survey, participants were advised that hyperventilation should be performed in a safe environment (e.g., not driving, or near water), as it may cause momentary loss of consciousness.

Shower protocol

Participants were instructed to begin their daily cold shower immersion by setting a timer to monitor the duration of their immersion. Upon starting the immersion, participants were asked to submerge as much of their body as possible, focusing particularly on the torso area. During immersion, participants were instructed to maintain controlled breathing, emphasising slow and deep inhalation through the nose and even slower exhalation through the mouth. As participants were requested to complete their daily intervention protocol before starting their day, they were given the option to start their shower with warm water if preferred and conclude with the cold immersion phase. For the first week, participants were directed to immerse themselves in cold water for increasing increments each week (i.e., 1, 1.5, 2, then 2.5 min), recording the cold immersion duration in their daily post-intervention survey.

Ice bath protocol

In addition to the daily shower cold immersion, the WHM condition (in-person) participants, comprising knowledge workers based in Sydney, Australia, attended weekly research-conducted ice bath sessions held in the Sydney Central Business District throughout the 4-week intervention period. Under the supervision and guidance of the research team and certified Wim Hof Method instructors, participants entered individually standing ice baths for the allocated period. Ice bath immersion timing increased weekly as with the cold showers (i.e., 1, 1.5, 2, then 2.5 min). Participants were informed of their cold immersion time to enter in their survey on exiting the ice bath, see Table 2 for ice bath temperatures. Due to logistical constraints and the inability to provide comparable supervision and support, the remote group did not participate in weekly ice baths.

Meditation condition protocol

Participants were provided with written mindfulness meditation instructions and were asked to familiarise themselves with them before starting the 15-min pre-recorded mindful breath awareness meditation video. The research team created the meditation video in collaboration with a certified mindfulness meditation instructor to closely align the WHM breathwork guided video, to ensure consistency and coherence across intervention materials. The written instructions asked participants to lie down flat with their legs bent at the knees and legs and arms uncrossed or to sit in a meditation posture if that was more comfortable. Participants were asked to anchor themselves to the feelings in their body, first by bringing their attention to the point between their eyebrows and then focusing on the natural rhythm of their breathing. They were then told that thoughts arising are completely normal, and if they notice that they have drifted off into thinking, they could anchor their attention by bringing focus back to the point in the centre of their eyebrows, and then simply returning to the natural rhythm of their breathing.

Analyses

Data analysis was conducted in R (version 2023.06.0 + 421). We used the ‘stats’ package49 to evaluate changes from onboarding over the 29-day intervention. Specifically, pairwise Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Tests (within condition, available in Supplementary Materials) and Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Tests (between conditions) due to the non-normal distribution of the data as determined by significant Shapiro–Wilk tests. Effect sizes (r) were calculated using the Wilcoxon Statistic normalised by its expected mean and standard deviation and then scaled by the square root of the sample size and were categorised as 0.10—< 0.3 (small effect), 0.30—< 0.5 (moderate effect) and > = 0.5 (large effect).

We used ‘lme4′50 and ‘lmerTest’ (p-values and confidence intervals51) packages in R to evaluate the within and between condition daily change scores while also accounting for intervention compliance. A p < 0.05 significance level was used to determine statistical significance, and unstandardised coefficients with confidence intervals included for interpretability. For all three analyses (Pairwise Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Tests, Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Tests, and Linear Mixed models), the default in R is listwise deletion (i.e., complete case analysis), whereby cases with missing values on analysis variables are excluded.

The data file consisted of N = 45,311 rows, each row containing day-of intervention survey responses (N = 7071), test scores for Stroop (N = 3304) and N-back (N = 3767), the previous night’s sleep data (N = 7656; average nightly sleep quantity, SWS, and REM sleep) and physiological data (average nightly HRV, resting heart rate, and respiratory rate), and pre and post-intervention survey data (N = 604). Participants were retained in the parametric pre-post analyses if they completed both the pre-intervention and post-intervention surveys (N = 302). For the linear mixed model analyses, participants were included if they completed at least two of the daily post-intervention surveys and had corresponding nightly physiological data (N = 404). Between-person controls of age and sex were included for use in our sensitivity analyses (see Control Analyses in Supplementary Materials).

Data preprocessing

Stroop data

Accuracy scores and mean reaction times and were computed for congruent and incongruent trials for each participant. The Stroop Interference Effect was calculated with correct response reaction times using the calculation (incongruent reaction time – congruent reaction time). Response times faster than 200 ms were identified as erroneous touches, as this time is considered the fastest finger reaction time possible to visual stimuli52. No participant had outliers (exceeding 3SD of their mean), so winsorising was not conducted. Stimuli were presented for a maximum display time of 3000 ms; reaction times exceeding this were also classified as extreme outliers and removed. In total, 502 individual occasions were removed as extreme outliers (498 too fast, 4 too slow).

N-back data. Accuracy scores for the 2-back and 3-back were computed for each participant by taking the mean score of all correct responses within each condition.

Heart rate variability. HRV values were natural log-transformed using the log() function in R to reduce the skewed distribution of raw HR values, as is customary in heart rate data analysis53.

Deviations from pre-registration

Analysis level structure

Change

We used two-level models instead of the preregistered three-level models for H3 and H4.

Rationale

The two-level model, with condition treated as a fixed effect, was a more appropriate approach given our sample size. It allowed us to directly examine the impact of condition on the H3 and H4 outcomes while preserving power and simplifying the model. The three-level model would have required a larger sample size to estimate random effects reliably.

Exclusion of random intercepts (Participant and time)

Change

We did not include random intercepts for the interaction between participants and time point for H3 and H4, as originally planned. Instead, we included days on protocol as a fixed effect in the interaction with intervention condition.

Rationale

Removing this random intercept simplified the model to align with the two-level structure and ensured sufficient power to detect condition-based differences over days on protocol without overfitting the data.

Control variables potency checks

Change

Instead of including between-person control variables (age and sex) directly in the main results, we first conducted potency checks to justify their inclusion.

Rationale

We tested whether these variables had a significant relationship with the outcomes. Only significant controls were included in the sensitivity analyses (see Sensitivity Analyses in Supplementary Materials), aligning with best practices for control variable use54,55.

Within-condition analyses for H3 and H4

Change

We preregistered between-condition effects for H3 and H4 but also ran within-condition analyses in the paper.

Rationale

Since H1 and H2 included both within- and between-condition predictions, we conducted within-condition analyses for H3 and H4 for consistency and thoroughness.

Within-condition analyses

Change

All within-condition results (H1-H4) are reported in full in Supplementary Materials.

Rationale

Between-condition results are the focus of our semi-randomised control trial, and in line with reviewer feedback and space constraints, within-condition results are reported in the Supplementary Materials.

There are also some differences between the OSF (As Predicted template) and ANZCTR (Trial Registration Template) preregistration content due to differing template structures, however the documents are not contradictory.

Results

Baseline differences

Trait measures

Baseline trait measures were largely comparable across conditions, as assessed using Kruskal–Wallis tests on all Time 1 survey measures. The only exception was the Interoception ‘Not Worrying’ subscale, where WHM participants scored significantly lower than those in WHM-Remote and Meditation (see Supplementary Table 1 for full details).

State measures

Baseline daily momentary measures were assessed using Kruskal–Wallis tests on 7-day pre-intervention ratings. Significant between-condition differences were found for energy, mental clarity, and ability to handle stress, with the WHM group scoring lower than both WHM-Remote and Meditation, while no differences were observed for stress or anxiety (see Baseline Differences in Supplementary Materials for full details).

Test of hypotheses

Hypothesis 1

We hypothesised that there would be improvement in post-intervention outcome measures compared to baseline across all three conditions, with the WHM condition showing greater improvement over the WHM-remote and Meditation conditions and the WHM-remote showing greater improvement over the Meditation condition.

Non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests investigating pre (day -14) and post (day 30) measures showed that the 29-day intervention largely improved outcomes across conditions. Please refer to the Supplementary Table 2 for full reporting of within-condition pre/post results. To assess between-condition differences, we computed change scores for each participant by subtracting their pre-intervention scores (Time 1 day -14) from their post-intervention scores (Time 2 day 30). We then ran Wilcoxon rank-sum tests to investigate significant changes between conditions. Full reporting of results is available in Supplementary Table 3. The analyses consisted of 302 participants who completed both Time 1 and Time 2 surveys (WHM = 118, WHM-Remote = 99, MC = 85). Attrition rates for the T2 off-boarding survey were WHM = 24, WHM-Remote = 32, and MC = 46.

Contrary to Hypothesis 1, results revealed a greater decrease in the anxiety subscale of the DASS-21 in the meditation condition compared to WHM-remote at the completion of the 29-day intervention, W = 4717.00, p = 0.044, 95% CI [0.00, 0.13], r = 0.003. However, this effect was not maintained at the one-month follow-up, with a Wilcoxon Rank-sum test indicating no significant difference between WHM-remote and Meditation conditions (W = 2374, p = 0.21; see Supplementary Table 3 and sensitivity analyses for full details).

Contrary to Hypothesis 1, no significant difference between conditions was observed for the depression or stress subscales.

Contrary to our Hypothesis 1, no significant differences were observed between conditions for any of the remaining scales, including frustration discomfort, interoceptive awareness, daily fatigue, sleep quality, and stress mindset, ps > 0.065.

Hypothesis 2

We hypothesized that there would be an improvement in daily momentary measures (pre/post daily intervention protocol) across all three conditions, with the WHM condition showing greater improvement over the WHM-remote and Meditation conditions, and the WHM-remote showing greater improvement over the Meditation condition.

Non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests investigating pre-post daily measures showed all three conditions had a significant increase in momentary energy, mental clarity, and ability to handle stress, and a significant decrease in momentary stress and anxiety following their daily intervention protocol. Please refer to the Supplementary Table 4 for full reporting of within-condition pre-/post-daily intervention results.

Linear Mixed Models tested whether the two WHM conditions showed greater change in momentary energy, mental clarity, anxiety, stress, and ability to handle stress, relative to the Meditation condition, following the daily protocols. Specifically, we assessed the impact of condition and days on intervention protocol, and their interaction on the daily measure change scores over the 29-day intervention. The model incorporated random intercepts for each participant to capture individual variability to account for the nested nature of the data. The momentary change scores were calculated as (participants’ daily protocol post-score—daily protocol pre-score). The days on protocol variable was calculated as the cumulative sum of daily intervention protocols completed for each participant on each study day. Incorporating the days on protocol variable, we were able to explore the cumulative impact of participants’ adherence to the daily intervention protocol on the daily fluctuations of our outcome variables, enabling us to assess whether the duration of adherence to the intervention protocols influenced our momentary outcomes. The analyses consisted of 404 participants who completed at least two daily intervention surveys (WHM = 142, WHM-remote = 131, Meditation control = 131). See Table 3 for a summary of the results.

In line with Hypothesis 2, both WHM and WHM-remote were associated with significantly greater increases in momentary energy levels, mental clarity, and ability to handle stress following the daily intervention compared to the Meditation condition. For all three measures, follow-up linear mixed model results revealed no significant differences between the two WHM conditions. A significant negative main effect of Days on Protocol on energy levels and mental change (but not ability to handle stress) was observed for the intercept (i.e., the Meditation condition). Importantly, significant Condition × Days on Protocol interactions indicated that for mental clarity and ability to handle stress, both WHM conditions showed progressively greater increases over time relative to meditation (see Fig. 3 for a Condition × Days on Protocol interaction plot for ability to handle stress). For energy level, however, this interaction was only observed for WHM relative to Meditation, with no significant interaction for WHM-remote.

Interaction plot illustrating the predicted values of Ability to Handle Stress Change Scores over the Days on Protocol across the three conditions. WHM Wim Hof Method in-person; WHM-remote Wim Hof Method remote. The plot is generated based on the linear mixed model analysis reported above, which includes a random intercept for each participant.

Results for momentary stress and anxiety diverged from Hypothesis 2. For stress, the Meditation condition showed a significantly greater momentary decrease than the WHM condition, while no difference emerged between WHM-remote and Meditation. However, WHM-remote participants reported a significantly greater decrease in stress compared to WHM. Importantly, the negative Condition × Days on Protocol interactions indicated that both WHM conditions showed progressively greater decreases in stress relative to Meditation over time. A significant positive main effect of Days on Protocol was also observed in the Meditation condition. For anxiety, no significant difference was observed between WHM and Meditation; however, WHM-remote showed a significantly greater decrease in anxiety compared to both Meditation and WHM. A significant positive main effect of Days on Protocol on anxiety was observed in the Meditation condition, with no significant interaction effects between conditions. A summary of within-condition changes before-to-after daily intervention protocols are reported in Supplementary Table 4.

Hypothesis 3

We hypothesized that there would be better executive functioning performance in the two WHM conditions relative to Meditation, following the daily intervention protocol.

Linear mixed models tested the impact of conditions, days on intervention protocol, and their interaction on executive function performance over the 29-day intervention. See Table 4 for a summary of the results. In line with Hypothesis 3, the WHM condition had significantly faster reaction times (Stroop congruent and incongruent trials) following the daily intervention compared to the Meditation condition, see Supplementary Figure 1 for Stroop incongruent reaction times across conditions. There was no significant difference in reaction times between the WHM-remote and Meditation conditions or between the two WHM conditions. However, contrary to hypotheses, the WHM condition had significantly lower Stroop incongruent accuracy relative to the Meditation condition. Meanwhile, no significant differences were observed between conditions for the 2-back, 3-back, Stroop congruent accuracy, or the Stroop Effect. Lastly, three significant main effects of Days on Protocol on executive function were observed for the intercept (Meditation). A negative main effect of Days on Protocol and Stroop congruent reaction time, and two positive main effects of Days on Protocol and 2-back and 3-back performance were observed. No Condition × Days on Protocol interactions were observed across measures. Please refer to the Supplementary Table 5 for full reporting of within-condition linear mixed model effects for executive function performance.

We also explored the immediate effects of ice bath cold immersion on executive function performance amongst the WHM condition participants. Full details can be found in the Exploratory Analyses section of the Supplementary Materials and Supplementary Table 7.

Hypothesis 4

We hypothesized that the WHM condition would show greater improvement in nightly physiological metrics than the WHM-remote and Meditation conditions, and the WHM-remote would show greater improvement over the Meditation condition over the 29-day protocol.

We constructed linear mixed models to assess the impact of condition, days on intervention protocol, and their interaction on the nightly physiological metrics over the 29-day intervention, see Table 5 for a summary of the results. In line with Hypothesis 4, WHM-remote showed a significantly lower respiratory rate relative to Meditation. Meanwhile, WHM-remote had a significantly lower respiratory rate and resting heart rate relative to the WHM condition. While no significant respiratory rate difference between WHM and Meditation was observed, a significant negative Condition × Days on Protocol interaction was found, whereby for each additional day on the protocol, WHM showed a greater decrease in respiratory rate compared to Meditation. Contrary to Hypothesis 4 WHM-remote had significantly less sleep duration relative to Meditation. Meanwhile, no significant difference in resting HR, HRV, SWS, or REM sleep was observed between conditions. Please refer to the Supplementary Table 6 for full reporting of within-condition linear mixed model effects for nightly physiological outcomes.

Exploratory analyses

We also explored the impact of conditions on participants’ self-reported psychological safety in their work terms. As with Hypothesis 1, we computed change scores for each participant by subtracting their pre-intervention scores (Time 1 day -14) from their post-intervention scores (Time 2 day 30). Wilcoxon rank-sum tests found partial support for our pre-registered exploratory hypothesis, revealing a significant increase in participants’ perceived psychological safety within their respective workplace teams for the WHM condition, W = 3575.50, p = 0.042, 95% CI [0.00, 0.50], r = 0.31 and the WHM-Remote condition, W = 2416.50, p = . 033, 95% CI [0.00, 0.40], r = 0.42 compared to the Meditation condition. No significant difference in psychological safety was observed between WHM and WHM-remote conditions, W = 3226.00, p = 0.808, 95% CI [-0.20, 0.20], r = 0.43. See Supplementary Figure 2 for a box plot of Wilcox ranked-sum psychological safety change scores between conditions. At the one-month follow-up, Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests showed no significant differences between WHM and Meditation (W = 882, p = 0.50) or between WHM-Remote and Meditation (W = 950, p = 0.98; see supplementary sensitivity analyses for full details). Please refer to the Exploratory Analyses section of the Supplementary Materials for full reporting of within-condition psychological safety results.

Discussion

This semi-randomised control trial aimed to investigate the psychophysiological and cognitive efficacy of the Wim Hof Method (in-person and remote) against an active control condition (mindfulness meditation) over a 29-day intervention with three month follow up. We assessed between-condition differences in (1) self-report pre- and post-study measures, (2) self-report pre- and post-momentary changes following daily intervention protocols, (3) post-daily intervention executive function performance, and (4) nightly physiological and sleep metrics. Overall, we found WHM practices (over and above Meditation) appeared to decrease nightly respiratory rate, and increase momentary energy levels, mental clarity, ability to handle stress, certain domains of executive function, and intriguingly, post-intervention psychological safety. Importantly, for every additional day on the WHM protocol we observed an increase in self-reported momentary energy, mental clarity, ability to handle stress, and a greater decrease in stress relative to Meditation. Meanwhile, the Meditation condition was associated with a greater reduction in momentary stress, trait anxiety, greater executive function accuracy, and longer sleep duration, relative to WHM. These findings, summarised below, contribute nuance to our understanding of these intervention techniques, their mechanisms, and their potential applications. See Supplementary Table 8 for an overview of findings relative to hypotheses.

Summary of results

Trait mental health and wellbeing (Hypothesis 1)

First, we examined the impact of the 29-day WHM intervention on pre- to post- self-report psychological measures. Participants in the Meditation condition showed a greater reduction in trait anxiety compared to the WHM-remote condition, and finally WHM. While this finding is consistent with the well-established anxiolytic effects of meditation practices56, it is contrary to our momentary state results, where WHM-remote practice was associated with the greatest momentary reductions in self-reported anxiety, followed by Meditation. This discrepancy between trait and momentary anxiety between conditions highlights a potential distinction between the immediate and long-term anxiolytic effects of these two practices on self-reported anxiety.

We also predicted that both WHM and Meditation would lead to improvements across all self-reported pre–post measures (e.g., depression, stress, fatigue, sleep quality). As expected, consistent within-condition improvements were observed (see Supplementary Table 2). Overall, however, contrary to our hypotheses, WHM was not more effective than Meditation, with no significant between-group differences across most self-reported outcomes immediately following the 29-day intervention.

Exploratory analyses

We also explored whether individual practice of the WHM influenced participants perceived psychological safety within their work environments before and after the 29-day intervention. Participants in both WHM conditions reported a significantly greater increase in their perceived team psychological safety compared to the Meditation group. These results suggest that the WHM may offer unique benefits that extend beyond individual stress management and adaptation to influence perceptions of workplace team dynamics. This is, to our knowledge, the first study to investigate this relationship, and these findings warrant further research to better understand the potential mechanisms.

Momentary state affect and functioning (Hypothesis 2)

We next examined the efficacy of the WHM for improving momentary state affect and functioning immediately following the daily intervention protocol. Between-condition comparisons revealed that both WHM conditions experienced significantly greater momentary improvements in their self-reported ability to handle stress, energy levels, and mental clarity compared to the Meditation. Importantly, our pre-registered analyses controlling for days on protocol (in line with previous approaches19) revealed an unexpected, but perhaps unsurprising, time-dependent interaction: whereby the magnitude of improvements increased with each additional day on the intervention protocol relative to Meditation. Although we did not explicitly hypothesize this interaction and it was modeled as a fixed effect, the observed pattern supports the idea of a possible hormetic, dose-dependent adaptation to repeated controlled stress exposure21, in line with other stress inoculation practices22,57.

Further, while the WHM condition overall showed less reduction in momentary stress following the daily intervention (relative to the Meditation control condition), the magnitude of stress reduction also increased with each additional day on the protocol in the WHM conditions, similarly suggesting a dose-dependent stress adaptation mechanism21.

More generally, the observed time- and dosage-dependent effects may account for the absence of trait-level improvements in mental health and wellbeing over the 29 days (Hypothesis 1), consistent with prior null findings from shorter 15-day WHM protocols assessing perceived stress, affect, and vitality20. Substantially longer intervention periods may be necessary to elicit hormetic adaptation needed to see measurable improvements in trait stress and resilience.

In the case of meditation, while it is difficult to deduce the practice to a single mechanism58, focused attention meditation is shown to enhance parasympathetic activation (e.g., a relaxation response59), resulting in the well-established stress-reducing effects8,56,60.

Executive functioning (Hypothesis 3)

We then investigated the effect of daily WHM protocol on executive functioning changes in working memory (N-back Task) and inhibitory control (Stroop Task) over the 29-day intervention. In line with our hypotheses, stroop reaction times were significantly faster in the WHM conditions, however contrary to our hypotheses the Meditation condition displayed greater Stroop accuracy. These findings align with existing literature linking fast breathwork (relative to slow breathwork) to improvements in reaction times60, cold-immersion to a speed-accuracy trade-off strategy in cognitive function (i.e., faster responses but lower accuracy61) and meditation to improvements in accuracy rather than reaction times62.

Nightly physiology and sleep (Hypothesis 4)

We examined the impact of the WHM intervention on nightly physiology and sleep across days on protocol. In line with our hypotheses, WHM conditions had significantly lower respiratory rate and resting heart rate (WHM-remote only), relative to Meditation. Additionally, we observed a small but significant decrease in respiratory rate for the WHM condition for every additional day on the protocol compared to the meditation condition. Given lower resting respiratory rate is associated with enhanced cardiovascular efficiency, improved ventilatory efficiency, and reduced sympathetic nervous system activation63, this reduction points to potential physiological benefits associated with combined cyclic hypoventilation and cold immersion. Contrary to our hypotheses, significantly greater sleep quantity was observed for Meditation relative to the WHM-remote condition. Overall, we observed no effects of SWS or REM sleep, aligning with recent investigations of high ventilation breathwork and meditation on sleep19,56.

Implications

The pattern of results (momentary state-level improvements in the WHM conditions that increased over time relative to Meditation, alongside largely non-significant 29-day trait-level differences), suggests a potential role for allostatic adaptation in state-to-trait change. Specifically, the WHM group not only showed greater momentary state improvements (in self-reported ability to handle stress, energy, and mental clarity) compared to Meditation, but these gains grew stronger over the days on the protocol. Moreover, although WHM participants initially reported a lower reduction in momentary stress levels relative to Meditation, the magnitude of this reduction increased over days on protocol for this group, over and above Meditation.

Taken together, these findings suggest a cumulative, dose-dependent relationship (i.e., hormetic inoculation), where repeated engagement with acute stressors in the WHM practice (e.g., cold exposure, cyclic hyperventilation, breath retention) stimulates adaptive responses that accumulate over time. These adaptive responses align with improved allostatic self-efficacy, as reflected in enhanced self-reported capacity to handle stress. Repeated intentional exposure to and recovery from short-term stress in WHM practices may therefore be encoded by the brain as successful stress coping, thereby adjusting expectations about allostatic self-efficacy and the range (or boundary conditions) of stress that one can cope with and recover from23.

While trait-level differences were largely not significant between groups, the trajectory of consistent improvement across days on protocol in the WHM conditions, particularly in terms of stress aptitude, may indicate a meaningful psychological adaptation, whereby meaningful changes in state-level psychological responses (e.g., changes in allostatic self-efficacy) repeated over time can contribute to longer-term trait development (i.e., in an Upward Spiral64).

A novel finding emerged whereby WHM practice positively influenced perceptions of psychological safety within participants’ work teams over and above Meditation. Psychological safety is a positive interpersonal climate where team members believe interpersonal risk-taking is safe35. Importantly, while it is evaluated at the team level, it is measured at the individual level through individual perceptions65. Given our interventions did not target team dynamics directly, our results may reflect an individual-level shift in interpersonal perceptions, potentially fostered by the WHM’s daily exposure to acute stress. Through stress adaptation practices in the WHM, individuals may have built stress resilience to engage in psychological safety behaviours, which are, by nature, interpersonally risky (e.g., such as admitting to mistakes, asking for help, and sharing ideas without fear of consequence to their self-image or career66). While psychological safety research has typically focused on leadership65, these findings suggest that interventions targeted at building individual team members’ stress resilience may be effective in improving psychological safety perceptions within the workplace. However, as this is the first known study to examine WHM in relation to psychological safety, replication is needed before drawing firm conclusions.

A practical implication for cognition is that the WHM was also associated with self-reported gains in mental clarity and objective improvements in executive function, skills that underpin planning, forethought, and goal-directed behaviour67. Cold showers may offer an accessible strategy to enhance basic cognitive processes such as response speed, while ice baths may offer additional benefits for higher-order functions like inhibitory control (see Exploratory Analyses in Supplementary Materials), which supports effective decision-making and self-regulation68.

Limitations & Future Research

Despite the study’s strengths, including the semi-randomised design, an active control condition, and the use of both subjective and objective measures, several limitations should be noted. First, compliance was modest (59–67% across conditions) despite instructions, reminders, and support sessions. While our sample size exceeded power thresholds for medium effects, smaller effects may have gone undetected. Nevertheless, compliance and missing data were consistent across conditions, and multilevel modelling is generally robust to missing data69. Future research might benefit from both shorter protocols (e.g., 3–4 days per week), given observed effects even at lower adherence levels, and also longer protocols, given the potential trajectory from state-to-trait level changes across days on protocol. Second, given this time-dependent dosage effect (suggesting possible state-to-trait level changes across days on protocol) was not hypothesised or pre-registered, there is a need for more targeted and hypothesis-driven approaches to this question in the future, perhaps in the context of longer interventions that may reveal trait changes. Third, without a passive control or external validation of our active control, we cannot rule out non-specific effects (e.g., expectancy, demand characteristics). Shared elements like structured practice and positive expectations may have contributed to improvements across all groups, and the absence of a control for the ice bath component limits our ability to isolate its specific effects. Similarly, because the study tested the full WHM protocol, we cannot determine whether effects stemmed from breathing, cold exposure, or their combination16. Fourth, cold exposure temperatures were not standardised across participants, a common challenge in home-based studies17, and adherence relied on self-report. Variability in shower temperature and exposure may have introduced error variance, and future research should test whether such variation influences WHM efficacy20. Fifth, our Meditation condition was intended as an active control, not an optimal mindfulness program; therefore, findings should not be interpreted as definitive comparisons with fully developed mindfulness-based interventions. Lastly, although the biometric device (WHOOP Strap 4.0) is validated for in-field sleep quantity and heart rate, its sleep stage detection (SWS and REM sleep) requires improvement38, which may explain the null effects for these metrics. Current validation studies37,38 are also company-funded, highlighting the need for future research to balance the convenience of remote commercially available biometric monitoring with independent validation and transparency.

Conclusions

This semi-randomised control trial comparing the WHM to an active meditation revealed both shared and distinct benefits across psychological, physiological, and cognitive domains. While both interventions improved within-condition trait (pre/post) measures of psychological functioning (see Supplementary Materials), they differed in between-condition state (momentary) profiles and underlying mechanisms. The WHM produced distinct state psychophysiological benefits beyond Meditation, including greater momentary self-reported energy, mental clarity, and ability to handle stress. Although WHM participants initially showed smaller reductions in momentary stress than Meditation participants, these reductions grew larger with each additional day on the protocol. This time × condition interaction was also observed for energy, mental clarity, and ability to handle stress, indicating cumulative, dose-dependent benefits with continued WHM practice. In contrast, Meditation showed benefits for attentional control, objective sleep quantity, trait anxiety, and momentary stress reduction, over and above WHM. Future research should isolate the active component effects of the WHM, examine how repeated state-level changes may translate into trait-level adaptations, and further investigate the distinct and complementary mechanisms of mind–body approaches for stress management and resilience across psychological, cognitive, and physiological domains.

Data availability

The data, materials, and code used in this study are available can be accessed by contacting nadia.fox@uq.edu.au.

References

Knauft, K., Waldron, A., Mathur, M. & Kalia, V. Perceived chronic stress influences the effect of acute stress on cognitive flexibility. Sci. Rep. 11, 23629 (2021).

Mattson, M. P. Dietary factors, hormesis and health. Ageing Res. Rev. 7, 43–48 (2008).

Sapolsky, R. Stress and the brain: individual variability and the inverted-U. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1344–1346 (2015).

Epel, E. S. et al. More than a feeling: A unified view of stress measurement for population science. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 49, 146–169 (2018).

McEwen, B. S. Stress, Adaptation, and Disease: Allostasis and Allostatic Load. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 840, 33–44 (1998).

McEwen, B. S. & Russo, S. J. Chronic work stress and mental health: reciprocal relationships and treatment implications. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 443–458 (2018).

von Känel, R. et al. Relationship between job burnout and somatic diseases: a network analysis. Sci. Rep. 10, 18438 (2020).

Sparacio, A. et al. Self-administered mindfulness interventions reduce stress in a large, randomized controlled multi-site study. Nat. Hum. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01907-7 (2024).

Crum, A. J., Salovey, P. & Achor, S. Rethinking stress: the role of mindsets in determining the stress response. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 104, 716–733 (2013).

Bosshard, M. & Gomez, P. Effectiveness of stress arousal reappraisal and stress-is-enhancing mindset interventions on task performance outcomes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci. Rep. 14, 7923 (2024).

WHM Services. Wim Hof Method benefits. Wim Hof Method benefits https://www.wimhofmethod.com/benefits (2024).

Almahayni, O. & Hammond, L. Does the Wim Hof Method have a beneficial impact on physiological and psychological outcomes in healthy and non-healthy participants? A Systematic review. PLoS ONE 19, 0286933–0286933 (2024).

Buijze, G. A. et al. An add-on training program involving breathing exercises, cold exposure, and meditation attenuates inflammation and disease activity in axial spondyloarthritis—A proof of concept trial. PLoS ONE 14, e0225749 (2019).

Kox, M. et al. Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 7379–7384 (2014).

Touskova, T. P. et al. A novel Wim Hof psychophysiological training program to reduce stress responses during an Antarctic expedition. J. Int. Med. Res. 50, 03000605221089883 (2022).

Kopplin, C. S. & Rosenthal, L. The positive effects of combined breathing techniques and cold exposure on perceived stress: a randomised trial. Curr. Psychol. 42, 27058–27070 (2023).

Buijze, G. A., Sierevelt, I. N., Heijden, B. C., Dijkgraaf, M. G. & Frings-Dresen, M. H. The effect of cold showering on health and work: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 11, 0161749 (2016).

Banushi, B. et al. Breathwork interventions for adults with clinically diagnosed anxiety disorders: A scoping review. Brain Sci. 13, 256 (2023).

Balban, M. Y. et al. Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. Cell Rep. Med. 4, 100895 (2023).

Ketelhut, S. et al. The effectiveness of the Wim Hof method on cardiac autonomic function, blood pressure, arterial compliance, and different psychological parameters. Sci. Rep. 13, 17517 (2023).

Calabrese, E. J. & Mattson, M. P. How does hormesis impact biology, toxicology, and medicine?. NPJ Aging Mech. Dis. 3, 13 (2017).

Wan, Y., Liu, J. & Mai, Y. Current advances and future trends of hormesis in disease. npj Aging 10, 26 (2024).

Stephan, K. E. et al. Allostatic self-efficacy: A metacognitive theory of dyshomeostasis-induced fatigue and depression. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10, 550 (2016).

Sterling, P. Allostasis: a model of predictive regulation. Physiol. Behav. 106, 5–15 (2012).

McEwen, B. S. & Wingfield, J. C. The concept of allostasis in biology and biomedicine. Horm. Behav. 43, 2–15 (2003).

Laurenceau, J.-P. & Bolger, N. Analyzing Diary and Intensive Longitudinal Data from Dyads. In Handbook of research methods for studying daily life (eds Mehl, M. R. & Conner, T. S.) (The Guilford Press, 2012).

Wiley, J. multilevelTools: Tools for multilevel modeling (R package version 0.x. (2020).

Geldhof, G. J., Preacher, K. J. & Zyphur, M. J. Reliability estimation in a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis framework. Psychol. Methods 19, 72–91 (2014).

Ryff, C. D. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57, 1069–1081 (1989).

Lovibond, P. F. & Lovibond, S. H. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 33, 335–343 (1995).

Natale, V., Fabbri, M., Tonetti, L. & Martoni, M. Psychometric goodness of the mini sleep questionnaire. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 68, 568–573 (2014).

Morris, S. et al. Multidimensional daily diary of fatigue-fibromyalgia-17 items (MDF-fibro-17) part 1: development and content validity. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 18, 195 (2017).

Mehling, W. E., Acree, M., Stewart, A., Silas, J. & Jones, A. The multidimensional assessment of interoceptive awareness, Version 2 (MAIA-2). PLoS ONE 13, e0208034 (2018).

Harrington, N. The frustration discomfort scale: development and psychometric properties. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 12, 374–387 (2005).

Edmondson, A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 44, 350–383 (1999).

Fox, N. Leaders’ Sleep, HRV, Executive Function, and Stress on Leadership Performance and Psychological Safety: Three in-Field Day-Level Studies [Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation (University of Queensland, 2024).

Berryhill, S. et al. Effect of wearables on sleep in healthy individuals: a randomized crossover trial and validation study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 16, 775–783 (2020).

Miller, D. J., Sargent, C. & Roach, G. D. A validation of six wearable devices for estimating sleep, heart rate and heart rate variability in healthy adults. Sensors 22, 6317 (2022).

Thayer, J. F., Hansen, A. L. & Johnsen, B. H. The Non-invasive Assessment of Autonomic Influences on the Heart Using Impedance Cardiography and Heart Rate Variability. In Handbook of Behavioral Medicine (ed. Steptoe, A.) (Springer, 2010).

Massaro, S. & Pecchia, L. Heart rate variability (HRV) analysis: A methodology for organizational neuroscience. Organ. Res. Methods 22, 354–393 (2019).

Uusitalo, A. et al. Heart rate variability related to effort at work. Appl. Ergon. 42, 830–838 (2011).

Zahn, D. et al. Heart rate variability and self-control—A meta-analysis. Biol. Psychol. 115, 9–26 (2016).

Parker, S. L., Sonnentag, S., Jimmieson, N. L. & Newton, C. J. Relaxation during the evening and next-morning energy: The role of hassles, uplifts, and heart rate variability during work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 25, 83 (2020).

Yin, Z., Yang, Y. & Hu, C. Wearable respiratory sensors for health monitoring. NPG Asia Mater 16, 8 (2024).

Maranci, J. B., Nigam, M. & Masset, L. Eye movement patterns correlate with overt emotional behaviours in rapid eye movement sleep. Sci. Rep. 12, 1770 (2022).

Stroop, J. R. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. J. Exp. Psychol. 18, 643–662 (1935).

Kane, M. J., Conway, A. R. A., Miura, T. K. & Colflesh, G. J. H. Working memory, attention control, and the N-back task: A question of construct validity. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 33, 615–622 (2007).

Scharinger, C., Prislan, L., Bernecker, K. & Ninaus, M. Gamification of an n-back working memory task - Is it worth the effort? An EEG and eye-tracking study. Biol. Psychol. 179, 108545 (2023).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing (2021).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Software https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1406.5823 (2014).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. B. & Christensen, R. H. B. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Software 82, 1–26 (2017).

Ng, A. W. & Chan, A. H. Finger Response Times to Visual. In: Auditory and Tactile Modality Stimuli Proceedings of the international multiconference of engineers and computer scientists. 2 1449–1454 (2012).

Nunan, D., Sandercock, G. R. & Brodie, D. A. A quantitative systematic review of normal values for short-term heart rate variability in healthy adults. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 33, 1407–1417 (2010).

Becker, T. E. et al. Statistical control in organizational research: An update, analysis, & discussion of next steps. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2014, 10370 (2014).

Bernerth, J. B. & Aguinis, H. A critical review and best-practice recommendations for control variable usage. Pers. Psychol. 68, 619–660 (2015).

Goyal, M. et al. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 174, 357–368 (2014).

Radak, Z., Chung, H. Y. & Goto, S. Systemic adaptation to oxidative challenge induced by regular exercise. Free Radical Biol. Med. 44, 153–159 (2008).

Sedlmeier, P. et al. The psychological effects of meditation: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 138, 1139–1171 (2012).

Amihai, I. & Kozhevnikov, M. Arousal vs. relaxation: a comparison of the neurophysiological and cognitive correlates of Vajrayana and Theravada meditative practices. PLoS ONE 9, 102990 (2014).