Abstract

Excessive visceral adipose tissue (VAT) has proven to be an efficient predictor of cardiovascular disease (CVD), independent of body mass index (BMI) or total body fat, and reducing visceral obesity is key to addressing the current epidemic of CVD. Selenium (Se) is suggested to protect against CVD, but a direct link between dietary Se intake and VAT levels is lacking. This study investigated this relationship, emphasizing the importance of expressing Se intake relative to body weight. A total of 3244 individuals participated in the Complex Diseases in the Newfoundland population: Environment and Genetics (CODING) study. Dietary Se intake was assessed using the Willett food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). VAT mass and VAT volume were precisely measured via dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Visceral adiposity, as indicated by VAT mass and VAT volume, decreased significantly across increasing quartiles of dietary Se intake (µg/kg/d) in both sexes. Compared with participants in the lowest quartile, those in the highest quartile had substantially lower visceral adiposity with reduction of 50.97% in women, and 63.75% in men, respectively. Likewise, this inverse dose-dependent manner was also observed when dietary Se intake was expressed as µg/d. Moreover, a linear negative correlation between dietary Se intake (µg/kg/d) and visceral adiposity was discovered, whereas no significant correlation was found if dietary Se intake was expressed as µg/d. After controlling for possible confounders, the linear regression analyses revealed that a 10% increase in dietary Se intake (µg/kg/d) was associated with 2.73% decrease in visceral adiposity. Interestingly, this inverse correlation remained consistent across different sex, age and menopausal status subgroups, with greater associations observed in males, individuals younger than 35 years old, and women in menopausal status. This is the first study to demonstrate a significant inverse association between dietary Se intake and VAT, which is exclusively evident when intake is expressed relative to body weight (µg/kg/d). This finding resolves prior inconsistencies and suggests that ensuring adequate weight-adjusted Se intake could be a valuable nutritional strategy for reducing visceral obesity and improving CVD prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) continues to be the leading cause of death worldwide, with approximately 17.9 million individuals dying each year; and one third of these deaths occur prematurely in people under 70 years of age, as estimated by the World Health Organization (WHO)1. Obesity, recognized as a major risk factor for CVD, has more than doubled in its age-standardized prevalence among adults aged 18 years and older, increasing from 6.6% in 1990 to 15.8% in 20222. Growing evidence supports that the amount of fat around the internal organs in the abdominal cavity, also called visceral adipose tissue (VAT), has been strongly associated with greater risks and earlier onset of CVD than fat stored elsewhere irrespective of body mass index (BMI) or total adiposity3,4,5. This has also confirmed the notion that excess VAT is predictive of an increased CVD risk independent of BMI or total body fat. Thus, from an early prevention standpoint, reducing visceral obesity is key to addressing the current epidemic of CVD. In addition to the contribution of genetics, lifestyle habits, including nutrients from dietary intake, are crucial factors that affect the amount of VAT6,7.

Selenium (Se), an essential trace element, is required for encoding the unique amino acid selenocysteine (Sec) and subsequent biosynthesis of selenoproteins8. Se exerts its biological effects through selenoproteins and plays multiple roles in physiological and pathophysiological processes, such as the regulation of oxidative stress, inflammatory response, and proliferation and differentiation of immune cells8,9. Based on the above functions of Se, it has long been suggested as a protective factor for CVD10,11,12,13. Studies have shown that physiologically high selenium levels in the body are associated with a decreased risk for CVD incidence, with a 15% (RR = 0.85) decreased risk of CVD incidence per 10 µg increment in blood selenium concentration10. Furthermore, a series of randomized controlled trials found that long-term Se yeast (200 µg/day) and coenzyme Q10 supplementation increased cardiac function and reduced cardiovascular mortality, suggesting that possible mechanisms may be due to the protective effects of Se in reducing systemic oxidative stress and inflammation11,12,13.

Considering the significant role of VAT in contributing to CVD, it is noteworthy that there is currently no evidence to directly link dietary Se intake with VAT levels. Understanding this relationship could be crucial for exploring potential new mechanisms by which Se exerts its protective effects against CVD. In our previous study, we discovered a negative correlation between dietary Se intake and various obesity measurements, including weight, BMI, waist circumference (WC), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), total body fat (BF), trunk fat (TF), android fat (AF), and gynoid fat (GF), and the correlations persisted in significance even after adjustments for age, total dietary caloric intake, and physical activity14. Given that WC and AF serve as indicators of abdominal fat distribution3, it is plausible to hypothesize a connection between Se intake and the accumulation of intra-abdominal fat. Thus, in this study, we aimed to delve into the relationship between dietary Se intake and visceral adiposity, which may contribute to the development of more effective strategies for the early prevention of CVD.

Methods

Study population

This study constitutes a secondary analysis of the Complex Diseases in the Newfoundland population: Environment and Genetics (CODING) study, a cohort established and maintained by our research group. Eligibility of participants for the CODING study was based on the following original inclusion criteria: 1) ≥ 19 years of age; 2) at least a third generation Newfoundlander; 3) healthy, without any serious metabolic, cardiovascular, or endocrine diseases; and 4) women were not pregnant at the time of the study14,15,16. All participants provided written informed consent, which explicitly authorized the use of their de-identified data for future research analyses. The original CODING study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Authority (HREA) of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Canada, with project identification code #10.33. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The ethical framework of the original approval encompasses secondary analyses of the de-identified dataset by the research team, and therefore, separate ethics approval for this specific analysis was not required.

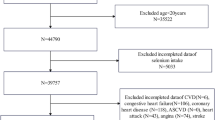

A total of 3244 participants from the CODING study 2003–2017 were included initially. First, we excluded participants without data on VAT mass for 138 individuals and food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) for 126 individuals. Second, those with incomplete or missing data, including weight and height for 1 individual, WC and hip circumference (HC) for 11 individuals, and physical activity information for 17 individuals were excluded. Third, participants were excluded for 19 individuals with dietary Se intake above 400 µg per day, the upper tolerable limit for adults17,18. Finally, a total of 2932 participants were enrolled in the present study (Fig. 1).

Flow chart of the enrolled participants. A total of 3244 participants from the CODING study 2003–2017 were included initially. After excluding those with incomplete or missing data on VAT, FFQ, and relevant covariates, a total of 2932 participants were included in the final analyses. VAT, visceral adipose tissue; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; WC, waist circumference; HC, hip circumference; Se, selenium.

Dietary se intake assessment

A 124-item semiquantitative Willett FFQ was used to assess dietary intake for each participant, which is the most cost-effective dietary assessment method utilized in large-scale epidemiological studies19,20. The FFQ was obtained from participants regarding the number of weekly servings consumed of common food items over the past 12 months. Then, the quantity of each food item was converted into a daily average intake value, which was used subsequently to calculate dietary calories (kcal/d) and Se intake (µg/d) based on the Nutribase Clinical Nutrition Manager (software version 9.0; Cybersoft Inc, Phoenix, AZ, USA) as we previously described14,15. The intake of dietary Se (µg/kg/d) was also estimated by dividing by body weight for each participant.

Anthropometric measurements and other relevant covariates

Anthropometric data were measured and recorded by trained personnel from all participants following a 12-hour overnight fast, including sex, age, body weight, height, WC, and HC. The BMI was calculated as body weight/(height ×height) (kg/m2). The waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) was calculated as WC/HC. Moreover, physical activity levels were measured via the ARIC Baecke Questionnaire, which consists of work, sport, and leisure time activity indices14,15. In addition, women completed questionnaires regarding menstrual history and menopausal status (pre-menopausal or menopausal).

Visceral adiposity measurements

Whole-body dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA; Lunar Prodigy; GE Medical Systems, Madison, WI, USA) scans were taken while patients lay horizontally on the scanner following a 12-hour fast. The fat mass was measured in different regions, including arms, legs, trunk, android, and gynoid regions. VAT mass and VAT volume were precisely delineated using the DXA software algorithm during the analysis of the scans16, which has been shown to be an accurate method correlating well with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) estimations of visceral fat mass and volume21,22. Daily quality assurance was performed on the DXA scanner, and the typical coefficient of variation was 1.3% during the study period14,15,16.

Statistical analyses

SPSS software version 26.0 was used for statistical analyses. All continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard error (SE), among which calorie intake, dietary Se intake, VAT mass and VAT volume were log-transformed to normalize distributions in order to perform effective data analyses. Comparisons of continuous data between two subgroups were analyzed using the independent Student’s t-test. Comparisons of continuous data among quartiles of dietary Se intake were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by pairwise comparisons using the least significant difference (LSD) test.

Pearson partial correlation analysis was used to identify significant correlations of Se intake with body weight, BMI, WC, HC, WHR, and visceral adiposity, in which the confounding variables including age, physical activity, and calorie intake, were statistically controlled. The association of dietary Se intake with visceral adiposity was estimated using multivariable linear regression models, and dietary Se intake, VAT mass, and VAT volume underwent log10 transformation in the linear regression analyses. Three models were applied in the present study, with adjustment for potential confounders ascertained based on prior publications14,15,16,22. Model 1 was the crude model without adjustment for potential confounders. Model 2 was adjusted for age, and sex. Model 3 was further adjusted for WC, physical activity and calorie intake. Multicollinearity did not occur in any of these models. A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics, dietary se intake, and visceral adiposity according to sex

A total of 2932 participants, comprising 2109 females and 823 males, were included in the present study (Table 1). The average age of women was 3.5 years older than that of men. Men had significantly higher weight, BMI, WC, WHR, physical activity, calorie intake, VAT mass, and VAT volume than women (P < 0.001). However, men had slightly lower HC than women. The average dietary Se intake of the entire population was 105.75 µg/d, with its level higher in men than in women (120.65 µg/d vs. 99.94 µg/d, P < 0.001). However, the difference between men and women was dramatically diminished, and even negligible, after adjusting for body weight (1.44 µg/kg/d vs. 1.47 µg/kg/d, P = 0.042).

Visceral adiposity levels according to quartiles of dietary se intake

The comparisons of clinical obesity-related measurements and visceral adiposity levels were performed among quartiles of dietary Se intake, expressed as micrograms per kilogram per day (µg/kg/d) and micrograms per day (µg/d), respectively (Tables 2 and 3). The study demonstrated that all markers, body weight, BMI, WC, HC, and WHR, decreased with increasing quartiles of dietary Se intake expressed as µg/kg/d (P < 0.001 for all, Table 2). Regarding visceral adiposity, as indicated by VAT mass and volume, a significant inverse dose-dependent relationship was observed with increasing dietary Se intake for both women and men. Compared with participants in the lowest quartile, those in the highest quartile had substantially lower VAT mass and volume with a reduction of 50.97% in women, and 63.75% in men, respectively.

Similar results were shown for VAT mass and volume when dietary Se intake was expressed as µg/d (Table 3) in most markers, especially in men. However, although there was a slight increase in body weight in the total population with increasing quartiles of dietary selenium intake, this increase did not reach statistical significance in men and women, respectively. Additionally, BMI, WC, HC, and WHR in women did not reach a statistical difference among the four dietary Se intake groups.

Correlations of dietary se intake with visceral adiposity

The correlations of clinical measurements related to obesity and visceral adiposity levels with dietary Se intake were presented, with intake expressed as µg/kg/d and µg/d, respectively (Table 4). The identified confounding variables including age, physical activity, and calorie intake were statistically controlled in the correlation analysis. When dietary Se intake was expressed as µg/kg/d, it revealed a linear negative correlation with all clinical measurements related to obesity in the entire population, and this correlation was also observed in both women and men (P < 0.001 for all). Moreover, dietary Se intake was negatively correlated with VAT mass and volume (r = −0.36, P < 0.001 for both) in the total population, with similar relations in women (r = −0.36, P < 0.001 for both) and men (r = −0.35, P < 0.001 for both).

However, when dietary Se intake was expressed in µg/d, no significant correlations were found, not only between dietary Se intake and clinical measurements related to obesity but also between dietary Se intake and visceral adiposity, as shown in Table 4.

Multivariable linear regression analyses for dietary selenium intake on visceral adiposity

Multivariable linear regression analysis (Table 5) showed that VAT mass and volume were inversely associated with dietary Se intake. The unadjusted crude model (Model 1) explained a small variance in VAT mass and volume by using only dietary Se intake (12.5% for both). After adjusting for age and sex (Model 2), this inverse association remained significant with a model that described a much higher variance in VAT mass and volume (29.7% for both). Following additional adjustments for WC, physical activity, and calorie intake in the fully adjusted model (Model 3), the significant negative associations still persisted with a model that explained the highest percentage of variance in VAT mass and volume (55.4% for both). Furthermore, the negative association in the fully adjusted model (Model 3) revealed that a 10% increase in dietary Se intake (µg/kg/d) was associated with a 2.73% decrease in VAT mass and volume (P < 0.001 for both, Table 5).

Subgroup analyses of the association between se intake and visceral adiposity

Subgroup regression analyses were performed based on the stratified factors including sex, age (<35, 3555, >55), and menopausal status in the fully adjusted model. The associations between visceral adiposity (indexed by VAT mass and volume) with dietary Se intake were consistently negative among all subgroups (P < 0.05 for all, Fig. 2). Those who were male (β = −0.394, 95% CI: −0.641−0.418, P = 0.002), younger than 35 years old (β = −0.423, 95% CI: −0.691−0.154, P = 0.002), or female in menopausal status (β = −0.230, 95% CI: −0.390−0.070, P = 0.005) were more prone to have lower VAT mass and volume compared with the other subgroups, respectively.

Subgroup analyses of the association between dietary Se intake and visceral adiposity. Dietary Se intake, VAT mass and VAT volume were log10 transformed in the linear regression analyses. The results of the association between dietary Se intake and VAT mass were the same as those for the association between dietary Se intake and VAT volume. Se, selenium; VAT, visceral adipose tissue.

Discussion

Recognized as a pivotal micronutrient, Se is of fundamental importance to human health in trace amounts10,23. Insufficient Se intake can cause the development of Keshan disease (KD) characterized by cardiomyopathy, whereas excessive Se consumption can lead to adverse health issues, such as loss of hair and nails, skin lesions, nervous system disorders, and even fatality10,23,24. Given the narrow range between Se deficiency and toxicity, maintaining an optimal daily Se intake is essential. The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of daily dietary Se intake for adults is 55 µg/d, corresponding to 0.51.0 µg/kg/d25, the amount that is needed to maximize plasma glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity17,26. Meanwhile, the tolerable upper intake level (UL) for adults is set at 400 µg/d to prevent selenosis as the adverse effect17,26, above which toxicity is observed around 815 µg/kg/d25. Dietary Se intake varies based on geographic locations; numerous people in some countries suffer from suboptimal levels of dietary Se intake, including KD areas of China (such as Wanyuan of Sichuan and Chuxiong of Yunnan with 311 µg/d), Finland (25 µg/d), and Turkey (30 µg/d)23,24,27. However, there is no indication of average Se intake below the RDA in Se-enriched areas, such as Japan (127.5 µg/d), USA (60160 µg/d), Canada (98224 µg/d), and India, even above the UL (475632 µg/d)24,27,28. In this study, the mean dietary Se intake was 105.75 µg/d and 1.46 µg/kg/d, which is similar to the previously reported dietary Se intake of the general Canadian population27,28,29, indicating an adequate Se intake in the Newfoundland population. Consistent with our previous study14, men exhibited a higher dietary Se intake (µg/d) than women, but the difference was nearly eliminated after adjustment for body weight.

The dietary sources of Se, and consequently population intake, vary dramatically based on geographic location and associated soil Se content, as well as local dietary patterns. The notably low intakes in historical KD areas of China, Finland, and Turkey are linked to populations relying on local cereal grains and vegetables grown on low-Se soil regions, with minimal contribution from Se-rich animal products23,24,27. In contrast, in populations with adequate or high Se status, dietary patterns include significant contributions from Se-accumulating foods. In the United States and Canada, the primary dietary sources are animal products, such as meats, poultry, and seafood, as well as grains; animals often concentrate Se from Se-supplemented feed or from grains grown in Se-adequate soils27,28,30. While specific dietary studies on Se sources in Newfoundland are limited, the general Canadian and North American dietary pattern is characterized by adequate consumption of these Se-rich foods. Furthermore, given Newfoundland’s coastal location, it is plausible that seafood—a category known to be high in Se, including fish and shellfish—is a significant contributor to the dietary intake in this population. This pattern mirrors that of Japan, where high seafood consumption ensures ample Se intake, and stands in stark contrast to the seleniferous regions of India, where high intake results from plant crops grown in Se-rich soil27,31. Beyond ensuring adequate intake from these diverse dietary sources, the biological impact of selenium depends fundamentally on its incorporation into functional selenoproteins. The cardioprotective effect of Se is primarily mediated by these selenoproteins, which are crucial for regulating redox homeostasis. In the context of VAT mass/volume, a key molecular mechanism linking moderate-to-high selenium intake to its reduction may involve the selenoprotein-mediated attenuation of adipocyte dysfunction and hypertrophy32. In adipose tissue, experimental work has shown that key selenoproteins such as glutathione peroxidases and thioredoxin reductases attenuate oxidative stress and subsequent activation of pro-inflammatory pathways like NF-κB32,33. This reduction in adipose tissue inflammation and oxidative stress improves adipocyte function, preventing pathological hypertrophy, and limiting the expansion of VAT mass/volume32,33. The consequent decrease in the release of free fatty acids and pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6) from visceral fat depots, in turn, ameliorates systemic insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction, thereby mitigating key pathways in the pathogenesis of diabetes, atherosclerosis and CVD32,33,34.

Although our previous studies revealed that women in the Newfoundland population have 12% more BF than men measured by DXA16,35, when it comes to visceral adiposity, we found that VAT mass and volume levels were approximately doubled in men compared to women. In addition to VAT, this study also showed increasing trends in body weight, BMI, WC, and WHR among men. Consistent with our findings, Anand et al36. documented that among 9189 participants from the Canadian Alliance for Healthy Hearts and Minds (CAHHM) and the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiological–Mind (PURE- MIND) cohort studies, Canadian females had higher percentage BF compared with males. However, males exhibited a higher mean VAT volume than females, as well as higher body weight, BMI, WC, and WHR36. These trends may at least partially explain the male predisposition towards CVD prevalence and mortality among middle-aged men in Canada, specifically those aged 30 to 64 years37,38,39. Therefore, strategies that could improve the above CVD risk factors, especially VAT, are key to preventing or delaying the onset of CVD.

Recently, there has been a growing interest in the role of dietary Se intake in obesity and body fat composition, though the results have been inconsistent. A group of observational studies found no significant difference of in dietary Se intake (µg/d) between normal weight and overweight/obese adolescents, as well as in adults40,41,42. A cross-sectional study also indicated that there was no association between Se intake (µg/d), BMI, and WC in United States adults using data from the 2007 to 2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)43. In contrast, a study by Fontenelle et al44. suggested an elevated Se intake (µg/d) in obese adult women compared to a normal weight group. However, when body weight was considered, the relative Se intake (µg/kg/d) was actually lower in the obese group. Interestingly, a subsequent study from the same group showed that while absolute dietary Se intake (µg/d) was adequate and not significantly different between control and obese participants (70.34 µg/d vs. 71.30 µg/d), the relative Se intake (µg/kg/d) was significantly lower among the obese group in Brazil (0.68 µg/kg/d compared to 1.27 µg/kg/d)45. This lower relative intake was accompanied by decreased plasma Se levels, and similar results were also confirmed in their other studies46,47,48. Taken together, it is worth noting that individuals with obesity, due to their higher body weight, may require a relatively higher absolute Se intake (µg/d) than the recommended values to achieve equivalent plasma Se levels. In other words, to ensure adequate Se nutrition, it is both reasonable and crucial to take body weight into account when determining intake requirements. Moreover, dietary Se intake, expressed in µg/kg/d, should be discussed simultaneously in relevant research, as it may be a partial reason for the above-mentioned conflicting results.

In addition, a negative correlation of dietary Se intake with WC, WHR, BF, TF, AF, GF, and AF/GF was reported14,45,49. Meanwhile, plasma Se has also been proved to be inversely associated with BMI, WC, WHR, and BF50,51,52. Furthermore, a randomized prospective study including 37 overweight/obese individuals showed that supplementation with L-selenomethionine (240 µg/d) for 3 months could decrease body fat mass compared to the placebo control group53. In the present study, we showed that with increasing quartiles of dietary Se intake (µg/kg/d), body weight, BMI, WC, HC, and WHR were all decreased in both female and male participants. However, when Se intake was expressed as µg/d, body weight in men, BMI, WC, HC, and WHR in women did not reach statistical difference among the four dietary Se intake (µg/d) groups. Furthermore, correlation analysis revealed that after adjusting for age, physical activity, and calorie intake, a linear negative association of dietary Se intake (µg/kg/d) with body weight, BMI, WC, HC, and WHR was observed, but no significant correlations were found if dietary Se intake was expressed in µg/d. Thus, this study also clarifies the indispensable role of body weight in dietary Se-related research.

Dietary Se intake is linked with WC and AF, indicating a strong relationship between dietary Se and the distribution of abdominal fat, particularly with the accumulation of VAT. An observational study of 42Canadian adults with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) conducted by Aktary et al29. showed that dietary Se intake (µg/d) was negatively correlated with liver fat measured via MRI (r = − 0.501, P = 0.015) in females. This study highlighted the role of dietary Se on VAT, although no current evidence directly links dietary Se intake with VAT levels. In the present study, VAT mass and volume decreased with the increase of dietary Se quartiles (µg/kg/d) both in women and men, and this inverse dose-dependent relationship was also observed when dietary Se intake was expressed as µg/d. Moreover, dietary Se intake was negatively correlated with VAT mass and volume in the total population, with similar relations in women and men. However, no significant correlations were found if dietary Se intake was expressed as µg/d, so we did not include Se intake (µg/d) in the following linear regression analyses. In the fully adjusted model, the negative association of dietary Se (µg/kg/d) with VAT mass and volume revealed that a 10% increase in dietary Se intake was associated with a 2.73% decrease in visceral adiposity. The reduction in VAT associated with higher Se intake (µg/kg/d) is metabolically significant, as VAT is a key driver of insulin resistance and progression to type 2 diabetes. In fact, our recent analysis within this same cohort has already demonstrated a direct, inverse association between dietary Se intake (µg/kg/d) and the prevalence of prediabetes, reinforcing the potential role of adequate Se status in mitigating diabetes risk through pathways that may include reduced visceral adiposity54. Importantly, this inverse correlation between Se intake (µg/kg/d) and VAT remained consistent across different sex, age and menopausal status subgroups. These findings highlight the potential benefits of increasing dietary Se intake for reducing VAT mass and volume in various subgroups in the Newfoundland population, especially for males, individuals younger than 35 years old, and women in menopausal status.

The strengths of our research are significant. First, based on our current understanding, this is the first cross-sectional study specifically designed to analyze the association between dietary Se intake and VAT levels in the general population. Second, the inclusion of 2932 participants provided a more substantial sample size compared with previous studies, enhancing its statistical power. Third, the participants were recruited based on the absence of clinically diagnosed serious metabolic, cardiovascular, or endocrine diseases, as per the original CODING study criteria. While the cohort’s average BMI falls within the overweight or obese range, this metabolic profile is representative of a significant segment of the general Canadian population, which enhances the real-world applicability of our findings. Last, rigorous measures such as controlling for identified confounding factors and conducting subgroup analyses were taken to ensure the reliability of our results. Our findings carry significant clinical implications for populations with adequate baseline Se status, such as the Newfoundland cohort studied here. We demonstrate that within the safe, non-toxic range of intake, a higher dietary Se intake, specifically when expressed relative to body weight (µg/kg/d), is associated with a favorable reduction in visceral adiposity, a key risk factor for cardiometabolic disease. This suggests that for individuals who are overweight or obese, ensuring an adequate weight-adjusted Se intake could be a valuable, yet often overlooked, component of nutritional strategies aimed at mitigating visceral fat accumulation and its associated cardiometabolic risks. However, a key limitation must be acknowledged. The analysis relies on the CODING database, which, while extensive and well-characterized, is not current. This temporal limitation means that our findings reflect dietary patterns and population health status at the time of data collection and may not account for more recent shifts in the food supply or lifestyle. Consequently, the clinical implication—that ensuring adequate weight-adjusted selenium intake may help manage visceral adiposity—should be interpreted as a proof-of-concept derived from this specific cohort and time period. In addition to this temporal limitation, due to the cross-sectional design, no information regarding any causality between higher dietary Se intake and lower visceral adiposity can be provided. Therefore, additional longitudinal randomized controlled trials in this direction should be conducted, and investigation of the mechanisms of dietary Se on VAT levels through animal experiments is needed.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides a significant methodological and conceptual advance in the field of Se and body composition research. We demonstrate for the first time in a general population that the inverse association between dietary Se and visceral adiposity is only evident when intake is expressed relative to body weight (µg/kg/d), not as an absolute daily intake (µg/d). This key finding resolves prior inconsistencies in the literature and establishes body-weight adjustment as a crucial factor for uncovering Se’s true relationship with VAT. Our work moves beyond establishing adequate population-level Se status to show that within this safe range, a higher weight-adjusted intake is associated with a clinically favorable reduction in a major cardiometabolic risk factor. Therefore, ensuring adequate weight-adjusted Se intake may represent a novel nutritional strategy for VAT reduction and CVD risk mitigation, particularly in subgroups like men, younger adults, and postmenopausal women. Future research and dietary guidance should prioritize this weight-adjusted approach to fully elucidate Se’s role in human health.

Data availability

The CODING dataset used in this study is not publicly available due to privacy and ethical reasons. However, the de-identified participant data underlying the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author Guang Sun upon reasonable request. All requests are subject to a data access agreement to ensure compliance with the ethical provisions of the original informed consent and the policies of the Health Research Ethics Authority of Newfoundland.

Abbreviations

- AF:

-

Android fat

- BF:

-

Body fat

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- DXA:

-

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- FFQ:

-

Food frequency questionnaire

- GF:

-

Gynoid fat

- HC:

-

Hip circumference

- HREA:

-

Health research ethics authority

- Se:

-

Selenium

- Sec:

-

Selenocysteine

- VAT:

-

Visceral adipose tissue

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- WHR:

-

Waist-to-hip ratio

- WHO:

-

World health organization

References

World Health Organization (WHO). World health statistics 2024: monitoring health for the SDGs. WHO (2024).

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet (London Engl. 403 (10431), 1027–1250 (2024).

Powell-Wiley, T. M. et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 143 (21), e984–e1010 (2021).

Karlsson, T. et al. Contribution of genetics to visceral adiposity and its relation to cardiovascular and metabolic disease. Nat. Med. 25 (9), 1390–1395 (2019).

Piché, M. E., Tchernof, A. & Després, J. P. Obesity phenotypes, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Circul. Res. 126 (11), 1477–1500 (2020).

Salmón-Gómez, L., Catalán, V., Frühbeck, G. & Gómez-Ambrosi, J. Relevance of body composition in phenotyping the obesities. Reviews Endocr. Metabolic Disorders. 24 (5), 809–823 (2023).

Fridén, M. et al. Diet composition, nutrient substitutions and Circulating fatty acids in relation to ectopic and visceral fat depots. Clin. Nutr. 42 (10), 1922–1931 (2023).

Tsuji, P. A., Santesmasses, D., Lee, B. J., Gladyshev, V. N. & Hatfield, D. L. Historical roles of selenium and selenoproteins in health and development: the good, the bad and the ugly. International J. Mol. Sciences 23(1), 5 (2021).

Benstoem, C. et al. Selenium and its supplementation in cardiovascular disease–what do we know? Nutrients 7 (5), 3094–3118 (2015).

Kuria, A. et al. Selenium status in the body and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 61 (21), 3616–3625 (2021).

Alehagen, U., Aaseth, J., Alexander, J., Johansson, P. & Larsson, A. Supplemental selenium and coenzyme Q10 reduce glycation along with cardiovascular mortality in an elderly population with low selenium status - A four-year, prospective, randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 61, 126541 (2020).

Dunning, B. J. et al. Selenium and coenzyme Q(10) improve the systemic redox status while reducing cardiovascular mortality in elderly population-based individuals. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 204, 207–214 (2023).

Alehagen, U., Alexander, J. & Aaseth, J. Supplementation with selenium and coenzyme Q10 reduces cardiovascular mortality in elderly with low selenium status. A secondary analysis of A randomised clinical trial. PloS One 11 (7), e0157541 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Significant beneficial association of high dietary selenium intake with reduced body fat in the CODING study. Nutrients 8(1), 24 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. High dietary selenium intake is associated with less insulin resistance in the Newfoundland population. PloS One. 12 (4), e0174149 (2017).

Youssef, S., Nelder, M. & Sun, G. The association of upper body obesity with insulin resistance in the Newfoundland population. Int J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 18(11), 5858 (2021).

Monsen, E. R. Dietary reference intakes for the antioxidant nutrients: vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium, and carotenoids. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 100 (6), 637–640 (2000).

Prabhu, K. S., Lei, X. G. & Selenium Adv. Nutr. 7 (2), 415–417 (2016).

Willett, W. C. et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am. J. Epidemiol. 122 (1), 51–65 (1985).

Subar, A. F. et al. Comparative validation of the block, willett, and National cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires: the eating at america’s table study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 154 (12), 1089–1099 (2001).

Kaul, S. et al. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for quantification of visceral fat. Obes. (Silver Spring Md). 20 (6), 1313–1318 (2012).

Neeland, I. J., Grundy, S. M., Li, X., Adams-Huet, B. & Vega, G. L. Comparison of visceral fat mass measurement by dual-X-ray absorptiometry and magnetic resonance imaging in a multiethnic cohort: the Dallas heart study. Nutr. Diabetes. 6 (7), e221 (2016).

Zhao, X. et al. Selenium Spatial distribution and bioavailability of soil-plant systems in china: a comprehensive review. Environ. Geochem. Health. 46 (9), 341 (2024).

Dinh, Q. T. et al. Selenium distribution in the Chinese environment and its relationship with human health: a review. Environ. Int. 112, 294–309 (2018).

Tanguy, S., Grauzam, S., de Leiris, J. & Boucher, F. Impact of dietary selenium intake on cardiac health: experimental approaches and human studies. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 56 (7), 1106–1121 (2012).

Mohammadifard, N. et al. Trace minerals intake: risks and benefits for cardiovascular health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 59 (8), 1334–1346 (2019).

Navarro-Alarcon, M. & Cabrera-Vique, C. Selenium in food and the human body: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 400 (1–3), 115–141 (2008).

Thompson, J. N., Erdody, P. & Smith, D. C. Selenium content of food consumed by Canadians. J. Nutr. 105 (3), 274–277 (1975).

Aktary, M. L., Eller, L. K., Nicolucci, A. C. & Reimer, R. A. Cross-sectional analysis of the health profile and dietary intake of a sample of Canadian adults diagnosed with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Food Nutr. Res 64, 4548 (2020).

Thomson, C. D. Assessment of requirements for selenium and adequacy of selenium status: a review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 58 (3), 391–402 (2004).

Combs, G. F. Jr. Selenium in global food systems. Br. J. Nutr. 85 (5), 517–547 (2001).

Zhang, F., Li, X. & Wei, Y. Selenium and selenoproteins in health. Biomolecules 13(5), 799 (2023).

Silvestrini, A. et al. The role of selenium in oxidative stress and in nonthyroidal illness syndrome (NTIS): an overview. Curr. Med. Chem. 27 (3), 423–449 (2020).

Koenen, M., Hill, M. A., Cohen, P. & Sowers, J. R. Obesity, adipose tissue and vascular dysfunction. Circul. Res. 128 (7), 951–968 (2021).

Sun, G. et al. Concordance of BAI and BMI with DXA in the Newfoundland population. Obes. (Silver Spring Md). 21 (3), 499–503 (2013).

Anand, S. S. et al. Evaluation of adiposity and cognitive function in adults. JAMA Netw. Open. 5 (2), e2146324 (2022).

Hu, X. F., Singh, K., Kenny, T. A. & Chan, H. M. Prevalence of heart attack and stroke and associated risk factors among Inuit in canada: A comparison with the general Canadian population. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 222 (2), 319–326 (2019).

Thomas, R. D. et al. Validation of a case definition to identify patients diagnosed with cardiovascular disease in Canadian primary care practices. CJC Open. 5 (7), 567–576 (2023).

Bots, S. H., Peters, S. A. E. & Woodward, M. Sex differences in coronary heart disease and stroke mortality: a global assessment of the effect of ageing between 1980 and 2010. BMJ Glob Health. 2 (2), e000298 (2017).

Aminnejad, B. et al. Association of dietary antioxidant index with body mass index in adolescents. Obes. Sci. Pract. 9 (1), 15–22 (2023).

Wang, L., Liu, W., Bi, S., Zhou, L. & Li, L. Association between minerals intake and childhood obesity: A cross-sectional study of the NHANES database in 2007–2014. PloS One. 18 (12), e0295765 (2023).

Fontenelle, L. C. et al. Nutritional status of selenium in overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 41 (4), 862–884 (2022).

Jiang, S. et al. Association between dietary mineral nutrient intake, body mass index, and waist circumference in U.S. Adults using quantile regression analysis NHANES 2007–2014. PeerJ 8, e9127 (2020).

Fontenelle, L. C. et al. Relationship between selenium nutritional status and markers of low-grade chronic inflammation in obese women. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 201 (2), 663–676 (2023).

Cardoso, B. E. P. et al. Selenium biomarkers and their relationship to cardiovascular risk parameters in obese women. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 202 (3), 866–877 (2024).

Cruz, K. J. C. et al. Relationship between zinc, selenium, and magnesium status and markers of metabolically healthy and unhealthy obesity phenotypes. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 202 (8), 3449–3464 (2024).

Fontenelle, L. C. et al. Selenium status and its relationship with thyroid hormones in obese women. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 41, 398–404 (2021).

Watanabe, L. M. et al. The influence of serum selenium in differential epigenetic and transcriptional regulation of CPT1B gene in women with obesity. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 83, 127376 (2024).

Santos, A. C., Passos, A. F. F., Holzbach, L. C. & Cominetti, C. Selenium intake and glycemic control in young adults with normal-weight obesity syndrome. Front. Nutr. 8, 696325 (2021).

Gutiérrez-Bedmar, M. et al. Serum selenium and incident cardiovascular disease in the PREvención Con DIeta MEDiterránea (PREDIMED) trial: nested Case-Control study. J Clin. Med 11(22), 6664 (2022).

Soares de Oliveira, A. R. et al. Selenium status and oxidative stress in obese: influence of adiposity. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 51 (9), e13538 (2021).

Tinkov, A. A. et al. Trace element and mineral levels in serum, hair, and urine of obese women in relation to body composition, blood pressure, lipid profile, and insulin resistance. Biomolecules 11(5), 689 (2021).

Cavedon, E. et al. Selenium supplementation, body mass composition, and leptin levels in patients with obesity on a balanced mildly hypocaloric diet: A pilot study. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 4802739 (2020).

Yu, S., Zhang, H., Du, J. & Sun, G. Association between dietary selenium intake and the prevalence of prediabetes in Newfoundland population: a cross-sectional study. Front. Nutr. 12, 1615462 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully thank all of the volunteers who participated in this study.

Funding

This CODING (Complex Disease in Newfoundland population: Environment and Genetics) study was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR, operating grant: MOP192552 to Guang Sun).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y. performed statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. H.Z. conducted data collection. J.D. revised the manuscript. G.S. directed the entire study, revised the manuscript, and had primary responsibility for the final content of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Authority (HREA), Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, Canada, with project identification code #10.33. Written consent was provided by all who participated.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, S., Zhang, H., Du, J. et al. Significant reverse association between dietary selenium intake and visceral adiposity in the CODING study. Sci Rep 15, 44920 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29228-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29228-3