Abstract

Difference between the South Asian Summer Monsoon (SASM) and East Asian Summer Monsoon (EASM) is observed in modern climate variations, but remains unclear on the orbital timescales. In this study, we reconstruct the monsoon history using three high-resolution (~ 17 years) and precisely dated ( ~ ± 400 years) speleothem δ18O records from Zhangjia Cave in Sichuan Basin, spanning 126.2–138.8 ka BP. In comparison with most ASM speleothem δ18O records in penultimate deglaciation, we unravel three differences in structure, amplitude, and trends between the western and eastern ASM, applied to distinguish the SASM from the EASM. First, the SASM in last interglacial seems stronger than that in Holocene, in contrast to the relatively stable EASM. Second, the different amplitudes of δ18O variations across the Marine Isotope Stages 6–5 transition further distinguish the two monsoons system. Third, the SASM speleothems δ18O-gradually depleted trend is significantly different with the relatively stable speleothems δ18O in EASM during Heinrich Stadial 11, indicating the different responses to cross-equatorial insolation gradients between SASM and EASM. These findings suggest that the SASM is more sensitive to cross-equatorial insolation gradients and cross-equatorial flow dynamics, distinguishing it from the EASM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Asian Summer Monsoon (ASM) is a dominant monsoon system globally, typically divided into two subcomponents: the East Asian Summer Monsoon (EASM) and the South Asian Summer Monsoon (SASM)1. Meteorological studies have documented the distinct characteristics of these two monsoon systems on interannual or seasonal timescale2,3. The EASM exhibits both tropical and subtropical features, influenced by the western Pacific subtropical high, while the SASM is primarily tropical, driven by features such as the cross-equatorial flow. During the last millennials, the subtropical high and cross-equatorial flow have also driven significant spatial differences between SASM and EASM, indicated by the spatial pattern of speleothem δ18O records4,5.

Studies of their differences on orbital and millennial-scale timescales, however, remain very limited. Speleothem δ18O values from caves influenced by the SASM are more depleted during the last interglacial (Marine isotope stages, MIS 5e) compared to those during MIS 5c and 5a, roughly corresponding to changes in Northern Hemisphere summer insolation (NHSI) at 65°N6,7 or low-latitude interhemispheric insolation gradients8,9,10. Additionally, SASM δ18O records, along with records from the Arabian Sea, indicate a weakening monsoon between 22 and 17 ka, while EASM δ18O records likely point to enhancing monsoon conditions during the same period11. Speleothem δ18O values can document a decoupled relationship between the SASM and EASM, likely both on orbital timescales and during abrupt millennial-scale climate events. However, debate persists over the ASM evolution on orbital timescales, whether the absence extent of glacial-interglacial cycle remains similar in both monsoon sub-systems, or how global-ice volume influences both monsoon sub-systems in a differentiated manner12. Cheng et al.8 further developed the new theory of “monsoon system science”, which firstly put monsoon dynamic system into the context of both external insolation (high/low attitudes) and internal (ice volume/CO2) forcings, and providing new perspectives on low- and high-latitude interactions.

A key characteristic of the monsoon system is its incorporation of subsystems from different latitudinal zones, encompassing both the subtropical EASM and the purely tropical SASM. Identifying the differences between the SASM and EASM across different periods would be significant for advancing the frontiers of “monsoon system science”4,8. Notably, the millennium-scale changes during the penultimate deglaciation were marked by a ~ 6–7 ka long interval, referred to as the “weak monsoon interval-II” (WMI-II) or “Heinrich stadials 11”13,14, and it occurred with the apparently rising cross-equatorial insolation gradients in boreal summer or NHSI at 65°N. Although the Heinrich stadials 11 cooling in NH and the associated Southern Hemisphere (SH) warming can contribute to the decreasing interhemispheric temperature gradient to the first order, questions remain regarding the extent to which the increasing cross-equatorial insolation gradients influence the dynamics of both SASM and EASM during the WMI-II8, and whether there are the different appearances between the SASM and EASM.

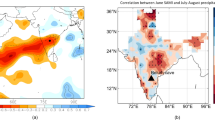

Here, we present three high-resolution (~ 17 years) and precisely dated ( ~ ± 400 years) speleothem δ18O records from Zhangjia Cave in the Sichuan Basin, located at the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 1), spanning from 126 to 138 ka BP. Through paleoclimate reconstruction and meteorological processes, our study aims to further disentangle the SASM influencing on Sichuan basin and examine the differences between the EASM and SASM domains on orbital timescales. Furthermore, we investigate the underlying dynamical forces driving their heterogeneities, distinguishing between external and internal forcings.

Cave locations alongside the spatial variations of precipitation differences. (A) Spatial pattern of JJAS minus the amount of DJFM precipitation using the GPCP data (from: https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.gpcp.html, with a grid resolution of 2.5 × 2.5°). The analyses are based on 1979–2017 data. (B) Tibet plateau and Huaxi Rain Screen (yellow lines) position and the elevation. Black circles depict cave locations: Bittoo Cave15, Wulu Cave (WL)16, SEY Cave7, Jiangjun Cave (JJ)17, Xiaobailong Cave (XBL)6. Yellow circles depict cave locations: Sanbao Cave (SH)18, Yangkou Cave (YK)19, Dongge Cave (DG)20,21 and the Hulu Cave (HL)14, and the black star shows the location of Zhangjia cave (this study). The map was primarily generated using MATLAB software and GPCP data.

Cave location, sample and climate

Zhangjia cave is located in Guangyuan City, Sichuan Province, southwestern China, near the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau (32°35′N, 105°58′E, ~ 680 m above sea level) (Fig. 1 and S1). Local climate is characterized by warm/wet summers and cool/dry winters. According to instrumental data from the Guangyuan meteorological station (~ 54 km southwest of the cave), the mean annual air temperature is 16.1 °C, and mean annual precipitation of ∼950 mm (1951–2019) falls mostly from June through September (∼74%)22,23, indicating the summer monsoon rainfall dominates the annual precipitation at the cave site. Continuous monitoring of temperature and humidity within the cave over 5 years (2017–2022) has shown that the relative humidity remains constant at approximately 100%, and the mean annual temperature inside the cave is approximately ~ 15.0 °C, close to local mean annual air temperature (16.1 °C). The cave, formed in the limestones of the Lower Triassic Feixianguan Formation, has an entrance of 3 × 4 m2, and its total length exceeds 1 km. The interior of the cave is relatively enclosed, with an underground river flowing throughout the year. Two well-developed cave chambers have formed inside, namely the first cave chamber (∼800 m from the entrance) and the second cave chamber (∼900 m from the entrance) (Fig. S2).

Three stalagmites (ZJD174, ZJD2020-1, and ZJD2020-2) were collected from the first chamber of the cave (Fig. S2), where ventilation is confined to a small channel to the outer chamber. The collected stalagmites all showed candlestick shapes, indicating rather stable growth conditions. The speleothem ZJD174, which is 548 mm in height and ~ 10 cm in width, exhibits a pronounced sedimentary discontinuity at the 403 mm mark. Speleothem ZJD2020-2, measuring 270 mm in height and approximately 65 mm in width, was broken and scattered on the first cave chamber, presumably as a consequence of seismic activity. Speleothem ZJD2020-1 was reported in our previous study23, which grew continuously from 132.8 ± 0.3 ka to 138.8 ± 0.4 ka, covering the late portion of the penultimate glacial period. The timing of monsoon shift from MIS6 to MIS5e in Zhangjia cave is in excellent agreement with speleothem data from Sanbao Cave13, Dongge Cave21, Hulu Cave in Southern China14, Xinglong Cave in northern China24, Xiaobailong Cave in Southwest China6, Bittoo Cave in India15, Clearwater Cave and Whiterock Cave in Borneo25.

Results

Chronology

Forty-three 230Th dates attained from ZJD174 indicate that it grew at 138.4–128.8 ka BP, with a hiatus between ~ 132.8 and 134.1 ka BP. Because of the high uranium concentrations (~ 2900–27000 ng/g) and relative low thorium concentrations (most of them were less than 100 pg/g), most of the dating errors are less than 4‰. Likewise, another 19 230Th dates from ZJD2020-2 show that the speleothem grew continuously from ~ 134.5 to 126.4 ka BP. This speleothem also exhibited high uranium concentrations (4000–16000 ng/g) and relatively low thorium concentrations (4000–16000 pg/g). The dating errors are less than 4‰. To minimize the dating errors, we increased the sampling weight and the test cycles of uranium and thorium. As a result, the final dating errors predominantly ranged between 2‰ and 3‰. Speleothem ZJD2020-2 supplements the hiatus in ZJD174 and the missing portion of MIS 5e (128.8–126.2 ka BP). Together, these two samples constitute a complete structure of the penultimate deglaciation period, including H11, TII and MIS5e.

The age models were built using the StalAge Monte-Carlo simulation (Fig. S3), and the 95% confidence limit was calculated from the distribution of the simulated fits (Scholz and Hoffmann, 2011). The ages are expressed in years before the present (1950).

δ18O records

The δ18O records of stalagmites ZJD174, ZJD2020-1, and ZJD2020-2 replicate each other very well during their overlapping time period, indicating the reproducibility of the cave records in this study (Fig. S4). The speleothem δ18O in our record shows similar variations to the well-studied cave records from Hulu, Sanbao and Dongge caves etc. within chronological uncertainties. Such similarities enable the replication of speleothem records from different caves and provide further evidence of the climatic relevance of the present record. It indicates that stalagmites ZJD174 and ZJD2020-1 appear to have been deposited in near-equilibrium conditions with cave drip water, and thus the speleothem δ18O appears to have been controlled by the δ18O of the drip water and the cave temperature.

The sampling strategies (i.e., drilling on the polished surface) produced a temporal resolution of the speleothem δ18O records, the ZJD174 record contains 548 δ18O data with a mean temporal resolution 17.5 years, while the ZJD2020-2 record, with about 270 sets of data, has a mean temporal resolution 33 years. Utilizing these two records, along with another annually laminated speleothem ZJD2020-1(a previously published record from Zhangjia cave, Cui et al. (2024)), we obtained a composite δ18O record, hereafter the Zhangjia record. We did not use any algorithms but achieved the composite time series record of the three stalagmites from Zhangjia Cave through simple splicing, because the amplitudes of the three records were sufficiently close. In Zhangjia record, we used the records with more 30Th age constraints and higher temporal resolution, including the original ZJD174 record from 128.8 ka BP to 133 ka BP, the original ZJD2020-1 record from 133 ka BP to 138.8 ka BP, and the ZJD2020-2 record from 126.6 to 128.8 ka BP. The Zhangjia record contains a total of 774 δ18O data, with a mean temporal resolution of 16.6 years, spaning from 126.2 ka BP to 138.8 ka BP.

The Zhangjia δ18O values vary between − 4.29 and − 12.96‰ (average − 7.64‰), with a maximum range of ~ 8.67‰. Superimposed on the long-term increasing trend are a series of millennial to centennial-scale fluctuations. The most prominent feature exhibited in the Zhangjia δ18O record is an abrupt shift at ~ 129.4 ± 0.3 ka BP, varying between − 7.1‰ and − 10.2‰, with a decrease of -3.1‰. We date-encrypted the timing of this key climate abrupt change, using 19 230Th dates derived from ZJD174 to constrain the timing of the abrupt shift to precisely 129.4 ± 0.3 ka BP. Complementarily, the abrupt shift in ZJD2020-2 is at 129.3 ± 0.3 ka BP accompanied by a δ18O decrease of ~ 3.3‰, which is similar to ZJD174 within the 230Th dating uncertainty, thereby corroborating the temporal and fluctuation range of the abrupt shift.

Discussion

Interpretation of cave speleothem δ18O

Our speleothem δ18O variability is similar to the trends in speleothem records from the SASM domain (Fig. 2A), as well as broadly consistent with the records from the EASM domain (Fig. 2B), suggests the stalagmites in this study were formed under (or near) isotope equilibrium conditions, and so the stable isotopes mainly reflect climate conditions. In addition, based on the temperature monitoring results of Zhangjia cave from 2017 to 2025, the current cave temperature shows very little seasonal variation (Temperature variations recorded during the monitoring period were 0.22 °C for the Hobo instrument, Fig. S9). So, a large portion of the variability in our samples must have resulted from changes in rainfall δ18O, which are likely dominated by upstream convection.

The Zhangjia δ18O amplitudes (~ 8.67‰) is markedly greater than that (~ 5‰) observed in speleothem records from the EASM domain (e.g., Hulu, Sanbao, and Dongge Cave), but comparable to that (~ 8‰) of the SASM region (e.g., Bittoo, and Xiaobailong Cave). In addition, our research area belongs to the southwest region, spatially closer to SASM domains (Fig. S8). Our research area is located in the Huaxi Rain Screen, mainly situated between the Sichuan Basin and the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau26. The Huaxi rain screen is one of the crucial areas for southwest or SASM moisture transport, with studies suggesting that this moisture flow could further influence northern China27, highlighting the significant role of SASM. Hence, these evidences support our interpretation of the speleothem δ18O mainly as a proxy of SASM strength.

Timing and structure of ASM shift from MIS6 to MIS5e

The abrupt shift in Zhangjia δ18O records commenced at 129.4 ± 0.3 ka BP with a significant decrease of ~ 3.3‰ in mere ~ 300 years based on its 230Th chronology, marking the onset of the last interglacial. The timing of this abrupt transition is in excellent agreement with speleothem data from Sanbao Cave13, Dongge Cave21, Hulu Cave in Southern China14, Xinglong Cave in northern China24, Xiaobailong Cave in Southwest China6, Bittoo Cave in India15, Clearwater Cave and Whiterock Cave in Borneo25. The speleothems chronologies across North and South China and other Asian locations constrain the synchronous timing of the onset of the last interglacial, further confirming a coherent temporal variation of precipitation δ18O in ASM regions6,18,28,29 (Fig. 3 and S5).

The onset of the last interglacial is also evident in speleothem records from other mid-low latitude regions, such as Soreq Cave in Israel30,31 and the Sofular Cave in Turkey32, and in some mid-high latitude speleothem records, such as Corchia Cave in the European Alps33,34,35 and Sieben Hengste (7 H) in central Switzerland hole36 (Fig. S5). Notably, the global timing of the various climate responses generally aligns with the transition timing of the ASM. The abrupt recovery of ASM in the presence of uncertain age is consistent with a sharp increase in SST in the North Atlantic37,38, a sharp rise in methane, and high atmospheric CO2 recorded in Antarctic ice cores39,40, indicating their synchronously beginning in the last interglacial period (Fig. 3).

A comparison of speleothem δ18O records between SASM (A) and EASM (B) domain. (A): (a) Zhangjia Cave (this study); (b) Wulu Cave16; (c) Jiangjun Cave17; (d) Bittoo Cave15. (B) (a) Hulu Cave14; (b) Sanbao Cave13; (c) Yangkou Cave19; (d) Dongge Cave21. The 230Th dates with uncertainties (± 2σ) are shown in each of the error bars. The vertical blue shadow bar indicates H11, and the red dashed line indicates the onset of the last interglacial. (C) The correlation coefficients (a) between cross-equatorial insolation gradients and different cave δ18O records, and the corresponding change rate (b and c) of caves δ18O respond to insolation.

EASM and SASM in prolonged weak monsoon interval

The Zhangjia Cave δ18O record from 136.4 to 129.8 ka BP in WMI-II, is relatively enriched, with an average value of -5.9‰, indicating a significantly weakening of the monsoon. The synchronous occurrence of these events (within age uncertainties) is consistent with the patterns observed in most other δ¹⁸O records from the ASM domains (Fig. 2 and S5). It corresponds to the severe millennial-scale cold event in the North Atlantic, associated with a significant weakening event of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), known as the Heinrich stadials 11, as recorded in Ocean Drilling Program (ODP) core 980. This event is linked to episodes of ice-rafted debris (IRD)38,41,42 (Fig. 3k-m). Beyond this general similarity, the high-resolution Zhangjia δ18O record further refines the understanding of the WMI-II disturbance, revealing two subphases: WMI-IIa (134.3 to 129.8 ka BP) and WMI-IIb (136.4 to 134.4 ka BP), separated by a brief centennial-scale strengthening of the ASM, known as the 134-ka event23. Our most recent data from ZJD174 and ZJD2020-2 further support our previous findings, confirming that the 134-ka event lasted no longer than 500 years. Previous work indicates the notion that ice volume is less effective in driving ASM changes21. In other words, the “ice volume effect” on the ASM would lie in its influence on the AMOC through North Atlantic meltwater forcing, and therefore the AMOC mode, not the ice volume, per se, would be more critical for low-latitude monsoons. Additionally, the 134-ka event appears to correlate with an abrupt AMOC change in a similar duration. In sum, the systematic ASM weakening during prolonged WMI-II is, to the first order, dominated by AMOC slow down, concomitant NH cooling, and decreasing interhemispheric temperature gradient in the perspective of “monsoon system science”.

On the other hand, Zhangjia δ18O record shows a gradual depletion of δ18O values during the prolonged WMI-II. This pattern exhibits a significantly negative correlation with the cross-equatorial insolation gradients in boreal summer (Fig. 2C). Notably, this feature is not as evident in records from middle-east China (Fig. 2AII). For instance, the δ18O data from Dongge and Sanbao Caves show no clear distinction between the two states of the WMI-II (Fig. 2B), and δ18O values in these records do not exhibit a significantly negative correlation with the cross-equatorial insolation gradient or the NHSI (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, these Dongge and Sanbao Caves sites are located relatively farther from the equator-crossing flow and SASM, making them less influenced. As modern meteorological studies suggest, these caves are more significantly affected by the subtropical monsoon, which is influenced by the subtropical high and westerly winds2,3.

While we have not considered the role of CO2 increasing or global ice sheet melting, these factors also operate through positive feedback processes that theoretically would enhance both monsoon sub-system. However, these effects seem very weak in enhancing the land-sea or high-low latitudes temperature gradient, and thus ASM intensity8. In sum, the Zhangjia Cave record, with its clear signal related to the SASM, and its similarities to records from regions more strongly influenced by the SASM, strongly indicates that the SASM is more significantly affected by the cross-equatorial insolation gradient than the EASM.

The climate changes from MIS6 to MIS5e: (a) δ18O records of Zhangjia Cave and insolation at 30°N − 30°S on July 21; (b) Atmospheric CH4 records39; (c) Atmospheric CO2 records39; (d) Relative sea level records (Grant et al., 2014); (e) The deuterium record39; (f-i) MD01-2444 alkenone uk’37 and Mg/Ca SST, planktonic (G. bulloides), benthic foraminiferal δ18O, temperate (Mediterranean + Eurosiberian) tree pollen percentages35; (j) ODP984 Neogloboquadrina pachyderma (s) (inverse scale), N. incompta percentages43; (k) ODP984 and MD03-2663 IRD percentages43,44; (l) εNd from the Bermuda Rise ODP 1063 site45; (m) 231Pa/230Th data from Bermuda Rise ODP 1063 site45; (n) %NPS (a temperature proxy) from the NE Atlantic46; (p) TEX86 temperature from Jiangjun Cave17. The red dashed line indicates the onset of the last interglacial.

EASM and SASM’s responses to orbital changes during penultimate deglaciation

During MIS5e, the δ18O values from Zhangjia Cave reached the most negative value of approximately − 13‰ around 126 ± 0.3 ka BP, which is similar to the records from Wanxiang Cave and Wulu Cave (Fig. 2A-b). In contrast, the δ18O records from Sanbao Cave remained relatively stable after the glacial terminations, with the most negative value reaching approximately − 11‰. Meanwhile, the δ18O values from Dongge Cave exhibited a positive trend following this climate pause, with the lowest value reaching around − 10‰. The δ18O magnitudes observed in the Zhangjia, Wulu, and Wanxiang Cave records during the transition from MIS6 to MIS5e are larger than those observed in the EASM domain, as seen in caves such as Hulu, Dongge, and Sanbao Cave13,18 (Figs. 2 and 4).

In addition, there are notable differences in the speleothem δ18O amplitudes between MIS 5e and the Holocene. Caves influenced by the SASM, such as Zhangjia, Wanxiang, and Xiaobailong, show significantly lower δ18O values during MIS 5e compared to the Holocene. These variations are consistent with strengthening in cross-equatorial insolation gradients (Fig. 4a-b) and the NHSI at 65°N on 21 July (Fig. 4d-f). On the other hand, in caves influenced by the EASM, such as Dongge, Sanbao, and Hulu, δ18O values in MIS 5e are similar to those in the Holocene (Fig. 4d-f), indicating a muted response of speleothem δ18O to insolation changes during MIS 5e.

Comparison of different Cave δ18O records, insolations, and AMOC intensity during the last two deglaciation and interglacial periods. (a) The δ18O records from Zhangjia Cave. This study (125–140 ka BP), among them 0 ~ 20 ka BP is a previously published record from Zhangjia cave22; (b) The δ18O records from Wanxiang Cave47; (c) AMOC intensity changes through simulation48; The 231Pa/230Th record of CDH19 borehole on the Bermuda Rise indicate the strength of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC)45,49,50; (d) The δ18O records from Sanbao Cave13,29; (e) The δ18O records from Dongge Cave21,51,52. (f) The δ18O records from Hulu Cave14,53; The insolation forcing is depicted by 30°N–30° S July 21 insolation (Orange curve); Insolation at 65°N on 21 July (Gray curve). The vertical blue shaded bars indicate cold periods, and the vertical orange shaded bars indicate warm periods.

These disparities suggest that different processes and moisture sources may influence the precipitation δ18O in the EASM and SASM regions6,54. For the EASM, three major moisture transport pathways have been identified through modern observations and model simulations (Fig. S10): the South Asian Ocean pathway, which crosses the Arabian Sea and the southern Bay of Bengal; the South China Sea and the tropical Pacific; and the Pacific. In contrast, moisture in southwest China and the southern Tibetan Plateau primarily originates from the Bay of Bengal, largely influenced by the SASM6,7,28.

The increased moisture contribution from the nearby Pacific and South China Sea, driven by an anomalous anticyclone over the northwestern Pacific (Fig. S6 and S7), resulted in precipitation enriched in δ18O. This may have had substantial impacts on the variation of EASM and the precipitation δ18O in East Asia during MIS 5e8,55,56, highlighting the role of Pacific moisture in EASM regions during this period. Additionally, the intensified southerly winds of the EASM led to reduced precipitation in eastern China and Japan, but increased precipitation further to the north and northwest in the modeling researches 55,56,57 (Fig. S6 and S7). Nevertheless, further model simulations are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

The ASM was intensified during the MIS5e as a result of enhanced inter-hemispheric thermal contrast and increased cross-equatorial moisture fluxes, directly responding to changes in cross-equatorial insolation10,58,59 (Fig. S6 and S7). This increase was further amplified by both local and remotely forced ocean mechanisms57. A cooler eastern South Asian Ocean increased the thermal gradient between the Eurasian continent and the Indian Ocean, thereby strengthening the ASM (Fig. S6). This mechanism is specific to the SASM, where the land-sea contrast occurs in the north-south direction, and may not significantly affect the East Asian monsoons precipitation (Fig. S7), where the land-sea contrast is oriented in the west-east direction. Additionally, Tibetan plateau, ~ 5 km above sea level, widely serve as a heat source that drives the SASM, particularly the narrow orography of the Himalayas and adjacent south mountain ranges60,61. Our study area, the Sichuan basin is also located in the southeast part of Tibetan plateau, indicating that Zhangjia cave seem be mainly dominated by the SASM, different with the cave in eastern China (Fig. 1).

The differences observed in our speleothem records between the EASM and SASM domains during the MIS6-MIS5 transition likely reflect the distinct behaviors of the SASM and EASM. The precipitation δ18O in Zhangjia Cave, influenced by the SASM, shows a more pronounced transition between MIS6 and MIS5, highlighting the stronger response of SASM-related moisture to interglacial climate changes.

Conclusion

Key discrepancies emerge between our records and the EASM domain in terms of ASM dynamics. First, amplified speleothem δ18O amplitude variations in our MIS6-MIS5 records, consistent with regional archives from southwestern China, reveal distinct response patterns between the SASM and EASM systems. Second, the progressive depletion of δ18O values in Zhangjia Cave stalagmites during the prolonged WMI-II period correlates with enhanced interhemispheric insolation gradients during boreal summer. These findings collectively indicate that Zhangjia’s precipitation δ18O primarily reflects SASM intensity, a system predominantly modulated by orbital-scale insolation forcing, during the Termination II. This mechanism also accounts for the elevated SASM intensity during MIS5e compared to the Holocene. Importantly, analogous to Termination II dynamics, our results suggest that future anthropogenic warming may exacerbate temporal decoupling between ASM subsystems, with critical implications for regional hydroclimate predictability.

Methods

230Th dating

Subsamples for 230Th dating were drilled along growth layers on the polished speleothem section using a 0.5-mm carbide dental drill. We followed standard chemistry procedures to separate uranium and thorium for instrument analysis62. 230Th dating was performed at Xi’an Jiaotong University, China, using a Thermo-Finnigan Neptune Plus multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC-ICP-MS). A triple-spike (229Th–233U–236U) isotope dilution method was employed to correct instrumental fractionation and determine U-Th isotopic ratios and concentrations. U and Th isotopes were measured on a MasCom multiplier behind the retarding potential quadrupole in the peak-jumping mode using standard procedures. Uncertainties in U and Th isotopic measurements were calculated offline at the 2σ level, including corrections for blanks, multiplier dark noise, abundance sensitivity, and contents of the same nuclides in the spike solution. The most recent values of the decay constants of 234U and 230Th and 238U were used. Corrected 230Th ages assume an initial 230Th/232Th atomic ratio of (4.4 ± 2.2) × 10 − 6 and those are the values for material at secular equilibrium with the bulk earth 232Th/238U value of 3.888. The corrections for samples in this study are small because their uranium concentrations are extremely high (~ 4000–27000 ng/g) and detrital 232Th is low (less than 1000 pg/g). We obtained a total of 62 230Th ages, all of them in stratigraphic order within uncertainties (Table. S1).

Stable isotopes

For each oxygen isotope measurement, ∼100 µg of powder samples were drilled from the central axis of the stalagmite. A total of 818 subsamples (548 from ZJD174 and 270 from ZJD2020-2) were micro-milled at 1-mm increments perpendicular to the growth axes and analyzed using a Thermo Scientific MAT253 plus mass spectrometer coupled with an online carbonate preparation device (Kiel IV) at the Isotope Laboratory, Xi’an Jiaotong University, China. The results show an analytical error (1σ) for δ18O of 0.06‰. International standards were added to the analysis every 10–20 samples to check reproducibility. The results are reported relative to the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) standard in δ-notation (‰).

Data availability

All speleothem isotope data and the chronology presented in this manuscript are available through the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/data-access/paleoclimatology-data).

References

Ding, Y. et al. Interdecadal and interannual variabilities of the Asian summer monsoon and its projection of future change. Chin. J. Atmospheric Sci. 37, 253–280 (2013).

TAO, S. Y. A review of recent research on the East Asian summer monsoon in China. Monsoon Meteorology, 60–92 (1987).

Wang, Y. J. et al. A high-resolution absolute-dated late pleistocene monsoon record from Hulu Cave, China. Science 294, 2345–2348 (2001).

Xiao, Z. et al. Spatial pattern of Asian stalagmite δ18O over the last millennium shaped by monsoon circulation changes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 662 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2025.119382 (2025).

Zhao, K. et al. Late holocene monsoon precipitation changes in Southern China and their linkage to Northern hemisphere temperature. Q. Sci. Rev. 232 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106191 (2020).

Cai, Y. et al. Variability of stalagmite-inferred Indian monsoon precipitation over the past 252,000 y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 2954–2959 (2015).

Liu, G. et al. On the glacial-interglacial variability of the Asian monsoon in speleothem δ18O records. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay8189 (2020).

Cheng, H. et al. Milankovitch theory and monsoon. The Innovation 3 (2022).

Cheng, H. et al. Orbital-scale Asian summer monsoon variations: paradox and exploration. Sci. China Earth Sci. 64, 529–544 (2021).

Beck, J. W. et al. A 550,000-year record of East Asian monsoon rainfall from 10Be in loess. Science 360, 877–881 (2018).

Jiang, X. et al. Decoupling of the East Asian summer monsoon and Indian summer monsoon between 20 and 17 ka. Quatern. Res. 82, 146–153 (2014).

Cheng, H. et al. Chinese stalagmite paleoclimate researches: A review and perspective. Sci. China Earth Sci. 62, 1489–1513 (2019).

Cheng, H. et al. Ice age terminations. Science 326, 248–252. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1177840 (2009).

Cheng, H. et al. A penultimate glacial monsoon record from Hulu cave and two-phase glacial terminations. Geology 34 https://doi.org/10.1130/g22289.1 (2006).

Kathayat, G. et al. Indian monsoon variability on millennial-orbital timescales. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–7 (2016).

Liu, S., Liu, D., Wang, Y., Zou, L. & Gao, H. Spatio-temporal expressions of precessional-scale stalagmite δ18O variations from the Asian monsoon area. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 585, 110720 (2022).

Wassenburg, J. A. et al. Penultimate deglaciation Asian monsoon response to North Atlantic circulation collapse. Nat. Geosci. 14, 937–941 (2021).

Cheng, H. et al. The Asian monsoon over the past 640,000 years and ice age terminations. Nature 534, 640–646. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18591 (2016).

Li, T. Y. et al. Stalagmite-inferred variability of the Asian summer monsoon during the penultimate glacial–interglacial period. Clim. Past. 10, 1211–1219. https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-10-1211-2014 (2014).

Yuan, D. et al. Timing, duration, and transitions of the last interglacial Asian monsoon. Science 304, 575–578 (2004).

Kelly, M. J. et al. High resolution characterization of the Asian monsoon between 146,000 and 99,000 years B.P. From Dongge Cave, China and global correlation of events surrounding termination II. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 236, 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.11.042 (2006).

Pan, L. et al. Different responses of precipitation patterns to the East Asian summer monsoon weakening: the 7.2 and 8.2 ka events. Q. Sci. Rev. 319, 108329 (2023).

Cui, J. et al. Precisely constrained 134-ka strong monsoon event in the penultimate deglaciation by an annually laminated speleothem from the Asian monsoon domain. Quatern. Res. 118, 116–125 (2024).

Duan, W., Cheng, H., Tan, M., Li, X. & Lawrence Edwards, R. Timing and structure of termination II in North China constrained by a precisely dated stalagmite record. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 512, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2019.01.043 (2019).

Carolin, S. A. et al. Northern Borneo stalagmite records reveal West Pacific hydroclimate across MIS 5 and 6. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 439, 182–193 (2016).

Sha, L. et al. Triple oxygen isotope compositions reveal transitions in the moisture source of West China autumn precipitation. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 188 (2024).

Zhang, X. Penetration of monsoonal water vapour into arid central Asia during the holocene: an isotopic perspective. Q. Sci. Rev. 251, 106713 (2021).

Cai, Y. et al. The holocene Indian monsoon variability over the Southern Tibetan plateau and its teleconnections. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 335, 135–144 (2012).

Wang, Y. et al. Millennial-and orbital-scale changes in the East Asian monsoon over the past 224,000 years. Nature 451, 1090–1093 (2008).

Bar-Matthews, M., Ayalon, A., Gilmour, M., Matthews, A. & Hawkesworth, C. J. Sea–land oxygen isotopic relationships from planktonic foraminifera and speleothems in the Eastern mediterranean region and their implication for paleorainfall during interglacial intervals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 67, 3181–3199 (2003).

Grant, K. et al. Rapid coupling between ice volume and Polar temperature over the past 150,000 years. Nature 491, 744–747 (2012).

Badertscher, S. et al. Pleistocene water intrusions from the mediterranean and Caspian seas into the black sea. Nat. Geosci. 4, 236–239 (2011).

Drysdale, R. et al. Magnesium in subaqueous speleothems as a potential palaeotemperature proxy. Nat. Commun. 11, 5027 (2020).

Drysdale, R. et al. Evidence for obliquity forcing of glacial termination II. Science 325, 1527–1531 (2009).

Tzedakis, P. et al. Enhanced climate instability in the North Atlantic and Southern Europe during the last interglacial. Nat. Commun. 9, 4235 (2018).

Luetscher, M. et al. A last interglacial speleothem record from the Sieben Hengste cave system (Switzerland): implications for alpine paleovegetation. Q. Sci. Rev. 262, 106974 (2021).

Jiménez-Amat, P. & Zahn, R. Offset timing of climate oscillations during the last two glacial‐interglacial transitions connected with large‐scale freshwater perturbation. Paleoceanography 30, 768–788 (2015).

Oppo, D. W., McManus, J. F. & Cullen, J. L. Evolution and demise of the last interglacial warmth in the subpolar North Atlantic. Q. Sci. Rev. 25, 3268–3277 (2006).

Petit, J. R. et al. Climate and atmospheric history of the past 420,000 years from the Vostok ice core, Antarctica. Nature 399, 429–436 (1999).

Schmidely, L. et al. CH 4 and N 2 O fluctuations during the penultimate deglaciation. Clim. Past. 17, 1627–1643 (2021).

Martrat, B., Jimenez-Amat, P., Zahn, R. & Grimalt, J. O. Similarities and dissimilarities between the last two deglaciations and interglaciations in the North Atlantic region. Q. Sci. Rev. 99, 122–134 (2014).

McManus, J. F., Oppo, D. W. & Cullen, J. L. A 0.5-million-year record of millennial-scale climate variability in the North Atlantic. Science 283, 971–975 (1999).

Mokeddem, Z., F McManus, J. & W Oppo, D. Oceanographic dynamics and the end of the last interglacial in the subpolar North Atlantic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 11263–11268 (2014).

Irvalı, N. et al. Evidence for regional cooling, frontal advances, and East Greenland ice sheet changes during the demise of the last interglacial. Q. Sci. Rev. 150, 184–199 (2016).

Böhm, E. et al. Strong and deep Atlantic meridional overturning circulation during the last glacial cycle. Nature 517, 73–76 (2015).

Barker, S. et al. Icebergs not the trigger for North Atlantic cold events. Nature 520, 333–336 (2015).

Jia, W. et al. The spatio-temporal pattern of Asian summer monsoon during glacial termination II recorded by Chinese stalagmite δ18O. Q. Sci. Rev. 313, 108193 (2023).

Clark, P. U. et al. Oceanic forcing of penultimate deglacial and last interglacial sea-level rise. Nature 577, 660–664 (2020).

McManus, J. F., Francois, R., Gherardi, J. M., Keigwin, L. D. & Brown-Leger, S. Collapse and rapid resumption of Atlantic meridional circulation linked to deglacial climate changes. Nature 428, 834–837 (2004).

Ng, H. C. et al. Coherent deglacial changes in Western Atlantic ocean circulation. Nat. Commun. 9, 2947 (2018).

Drysdale, R. N., Zanchetta, G., Hellstrom, J. C., Fallick, A. E. & Zhao, J. x. Stalagmite evidence for the onset of the last interglacial in Southern Europe at 129 ± 1 Ka. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32 (2005).

Wang, Y. et al. The holocene Asian monsoon: links to solar changes and North Atlantic climate. Science 308, 854–857 (2005).

Wang, Q. et al. Millennial-scale Asian monsoon variability during the late marine isotope stage 6 from Hulu Cave, China. Quatern. Res. 90, 394–405. https://doi.org/10.1017/qua.2018.75 (2018).

Cai, Y. et al. Orbital-to millennial‐scale variation of the speleothem δ18O record during marine isotope stages 5 to 3 on the Southeast Chinese loess plateau and its Climatic and environmental implications. J. Quat. Sci. 38, 295–307 (2023).

He, C., Li, T. & Zhou, W. Drier North American monsoon in contrast to Asian–African monsoon under global warming. J. Clim. 33, 9801–9816 (2020).

Shi, Z., Cai, Y., Liu, X. & Sha, Y. Distinct responses of East Asian and Indian summer monsoons to astronomical insolation during marine isotope stages 5c and 5e. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 510, 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.12.029 (2018).

Chen, K., Axelsson, J., Zhang, Q., Li, J. & Wang, L. EC-Earth simulations reveal enhanced inter‐hemispheric thermal contrast during the Last Interglacial further intensified the Indian Monsoon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL094551 (2022).

An, Z. et al. Global Monsoon Dynamicsand Climate Change. (2015).

An, Z. et al. Mid-Pleistocene climate transition triggered by Antarctic ice sheet growth. Science 385, 560–565 (2024).

Boos, W. R. & Kuang, Z. Dominant control of the South Asian monsoon by orographic insulation versus plateau heating. Nature 463, 218–222 (2010).

Zhang, R., Jiang, D., Zhang, Z. & Yu, E. The impact of regional uplift of the Tibetan plateau on the Asian monsoon climate. Palaeogeogr., Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 417, 137–150 (2015).

Edwards, R. L., Chen, J. & Wasserburg, G. 238U234U230Th232Th systematics and the precise measurement of time over the past 500,000 years. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 81, 175–192 (1987).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. Liangcheng Tan and Prof. Yan Yang for their kind comments on the manuscript, and Mrs. Xiaoli Qu, the engineer of the State Key Laboratory for Manufacturing Systems Engineering, School of Mechanical Engineering, Xi’an Jiaotong University, for her assistance with the LSCM work. This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 42372218, 42488201, 42472244), Project (No. KDL&Guangxi202005) supported by Guangxi Key Science and Technology Innovation Base on Karst Dynamics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z and J.C. did the fieldwork and collected the stalagmite. J.C. led the U/Th dating. J.Z. and J.C. led the stable isotope analyses. Writing was led by J.C. and data interpretation was led by J.Z., J.C. and H.C. with inputs from co-authors (L.P., J.W., Q.L., X.D., and K.W.).

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, J., Cui, J., Pan, L. et al. Monsoon differences in South Asia and East Asia during the penultimate deglaciation revealed by speleothem oxygen isotopes. Sci Rep 15, 45591 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29249-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29249-y