Abstract

Proteinuria contributes to venous thromboembolism (VTE), and its levels can change over time. This registry-based retrospective study investigated the association between changes in proteinuria status and VTE occurrence at the population level. We included participants (n = 1,712,507) who underwent two successive health checkups during the initial period (2003 or 2004) and the subsequent period (2005 or 2006). Outcomes were defined as the occurrence of VTE, including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary thromboembolism, and other venous thromboses, according to the International Classification of Diseases-10 code. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to assess the occurrence of VTE based on changes in proteinuria. Over a median follow-up period of 14.5 years, 45,711 participants (event rate: 1.88%) experienced a VTE. Compared with the normal group, the incidence risk of VTE dose dependently increased with the severity of proteinuria in each of the persistent, progressed, and improved groups (p for trend < 0.001). In a pairwise comparison, the risk of occurrence of VTE in the improved (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.18, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.10–1.27), progressed (HR: 1.31, 95% CI: 1.23–1.40), and persistent groups (HR: 1.88, 95% CI: 1.61–2.19) were higher than that of the normal group. In addition, the improved group had a lower risk of VTE occurrence than that of the persistent group (HR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.58–0.82, p < 0.001). Our study showed that the incidence risk of VTE was associated with change and severity of proteinuria status. Improvement in proteinuria may attenuate the occurrence of VTE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a major global health concern affecting approximately 10 million people worldwide every year1. A recent report indicated that the annual incidence of VTE ranges from 0.7 to 2.69 per thousand individuals2. However, with the global transition to an aging society, we anticipate further increases in the incidence of VTE1. Moreover, VTE, which encompasses conditions such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, substantially affects mortality and morbidity, with a high rate of recurrence2,3. Virchow postulated that the stagnation of blood flow, modifications in the vessel wall, and variations in blood composition contribute to thrombosis formation4. Although previous efforts to identify risk factors, including obesity, trauma, surgery, antiphospholipid syndrome, cancer, and prolonged bedridden state, are crucial to prevent VTE, further research is needed to gain additional insights into disease prevention5,6.

Proteinuria, marked by the presence of surplus protein in the urine, is a risk factor for renal disease7,8. The urine dipstick test, due to its ease of use, rapid results, affordability, and satisfactory diagnostic accuracy, is commonly used for health screening to detect proteinuria9. Previous studies indicated that proteinuria is associated with an elevated risk of mortality, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, kidney failure, and cardiovascular disease10,11,12,13. Additionally, proteinuria can increase the risk of VTE, including deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism6,14,15. However, the influence of alterations in proteinuria, evaluated through urine dipstick testing, on the risk of VTE occurrence remains inadequately determined, with limited extensive longitudinal studies focusing on this correlation16.

We hypothesized that the risk of VTE is influenced by the improvement or persistence of proteinuria and the severity of proteinuria. Therefore, we aimed to explore the association between changes in proteinuria status or severity of proteinuria and risk of VTE using a longitudinal cohort database representing the general population.

Results

Among the included participants, 1,670,263 (97.53%), 18,857 (1.10%), 21,073 (1.23%), and 2,314 (0.14%) were categorized into normal, improved, progressed, and persistent-proteinuria groups, respectively, according to changes in proteinuria (Table 1 and Table S1). The baseline characteristics based on changes in proteinuria status are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the overall participants was 44.04 ± 12.12 years, and 69.01% of them were male. The proportion of males was higher in the persistent group than in the other groups, whereas the improved group included more female. Body mass index was the highest in the persistent group. All comorbidities and CCI score ≥ 2 were the lowest in the normal group and the highest in the persistent group (Table 1).

Over a median follow-up of 14.5 (interquartile range: 14.2–15.1) years, 45,711 (1.88%) cases of VTE were recorded. The cumulative incidence curve using 1-Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the occurrence of VTE, including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary thromboembolism, and other venous thromboses, based on changes in proteinuria status, is shown in Fig. 1 and Figures S1-S3. Throughout the follow-up period, the occurrence of VTE was the highest in the persistent group, followed by the progressed, improved, and normal groups (Fig. 1). These findings were consistent with those of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary thromboembolism, and other venous thromboses (Figures S1-S3).

After propensity score matching in multivariate Cox regression analysis, compared with the normal group, the incidence risk of VTE and other venous thromboses increased with the change in proteinuria status in each of the persistent, progressed, and improved groups (all p for trend < 0.001). Additionally, the tendency for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary thromboembolism to increase according to changes in proteinuria status, compared with the normal group, was observed in the progressed group and the persistent group, but not in the improved group (Table S2-S16). In addition, compared with the normal group, the incidence risk of VTE increased with the severity of proteinuria in each of the persistent, progressed, and improved groups (p for trend < 0.001; Table 2 and Table S17). These results were consistent even when deep vein thrombosis (p for trend < 0.001) and other venous thrombosis (p for trend < 0.001) were considered as outcomes. In contrast, for pulmonary thromboembolism, the dose-response relationship according to the severity of proteinuria was significant only in the persistent group (p for trend < 0.001) but non-significant in the improved (p for trend = 0.247) and progressed groups (p for trend = 0.354; Table 2 and Tables S18-S20).

In a pairwise comparison, the risk of occurrence of VTE in the improved (HR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.10–1.27), progressed (HR: 1.31, 95% CI: 1.23–1.40), and persistent groups (HR: 1.88, 95% CI: 1.61–2.19) were higher than that of the normal group (Table 3). In contrast, the improved group had a lower risk of VTE occurrence than that of the persistent group (HR: 0.69, 95% CI: 0.58–0.82, p < 0.001), and the progressed group (HR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.82–1.00, p = 0.043). Similar results were observed for deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary thromboembolism, and other venous thromboses (Table 3). In the sensitivity analysis, these trends and results remained consistent, regardless of the history of renal disease (Table S21). These results were consistently observed in the sensitivity analysis regarding the change in the presence of proteinuria (Tables S22 and S23 and Figures S4-S7).

In addition, multivariate analysis revealed an association between the occurrence of VTE and proteinuria severity in the initial and subsequent periods. The association between the occurrence of VTE and the severity of proteinuria in the subsequent period significantly increased in the order of severity of proteinuria (+ 1, + 2, +3, and + 4) compared to negative proteinuria in the subsequent period (+ 1: 1.33 [1.24–1.43], + 2: 1.52 [1.37–1.69], + 3: 1.72 [1.38–2.16], and + 4: 2.57 [1.66–3.99]; p for trend < 0.001; Table S24). Considering the severity of proteinuria, the risk of occurrence of VTE showed an increasing trend based on the severity of proteinuria, regardless of the underlying renal conditions (Table S25).

Discussion

This registry-based retrospective study included data from adults who underwent repeated health checkups in South Korea to evaluate the impact of changes in proteinuria status or severity of proteinuria on the risk of VTE. The key findings of our study revealed that an improvement in proteinuria was associated with a reduced occurrence of VTE compared to persistent proteinuria or progressed proteinuria. Additionally, the occurrence of VTE was relatively higher when proteinuria progressed more severely or when severe proteinuria persisted. Furthermore, even if proteinuria improved, the risk of VTE increased when the initial proteinuria was severe or when the improvement was only partial rather than complete. Similar trends were observed for deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary thromboembolism, and other venous thromboses.

Previous studies have suggested an association between proteinuria and VTE17,18. Compared to patients without proteinuria, those with proteinuria were reported to have more than twice the risk of deep vein thrombosis and three times the risk of VTE17,19. Additionally, proteinuria was identified as a risk factor for VTE in patients with idiopathic membranous nephropathy20. However, the results of other studies have been controversial21,22. Furthermore, these studies only assessed proteinuria at baseline and did not account for alterations in proteinuria status, which can be influenced by factors such as glucose levels, blood pressure, and prescribed medications. Proteinuria can also be observed in patients without renal disease, hypertension, or diabetes. Additionally, the high false-positive rate associated with proteinuria in the general population has limitations. Therefore, assessing sequential changes in proteinuria may be a valuable approach to predict the risk of VTE.

Based on previous findings, this study highlights the association between alterations in proteinuria status and the occurrence of VTE. A previous study has suggested that patients with severe chronic kidney disease and persistent proteinuria are at an increased risk of developing VTE16. Another study showed that mild-to-moderate chronic kidney disease and proteinuria are risk factors for VTE23. Furthermore, chronic kidney disease is associated with deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary thromboembolism24,25,26. Changes in proteinuria status indicate kidney disease progression. The onset of proteinuria can potentially exacerbate damage to glomerular mesangial cells or tubules, consequently accelerating the progression of kidney disease27. Additionally, an increase in proteinuria over time is an independent predictor of both a rapid decline in kidney function and the development of kidney failure in patients with kidney disease28. Persistent proteinuria is an independent risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke29,30. However, to date, no study has examined the association between persistent proteinuria and the occurrence of VTE, including deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary thromboembolism. In the present study, the occurrence of VTE, including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary thromboembolism, and other venous thromboses, was relatively higher when proteinuria progressed more severely or when severe proteinuria persisted.

Various mechanisms explain the relationship between changes in proteinuria and the occurrence of VTE. A previous randomized controlled trial also showed that patients with proteinuria were in a more prothrombotic state than healthy controls, caused by higher levels of fibrinogen, factor V, free protein S, and prothrombin fragment 1 and 2.31 Furthermore, the levels of fibrinogen, factor V, free protein S, prothrombin fragments 1 and 2, and activated protein C resistance were significantly lower during the maximum proteinuria treatment period than during the placebo treatment period. Consequently, improved proteinuria based on antiproteinuric therapy may ameliorate this prothrombotic state31. Additionally, persistent proteinuria may be considered a marker of systemic dysfunction involving the vascular endothelium, hemostasis, and fibrinolysis, particularly in individuals with conventional cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension32. This may represent another mechanism that contributes to the increased risk of VTE33,34. Moreover, persistent proteinuria may affect risk factors for VTE, such as platelet function, inflammation, and intravascular volume35,36.

The present study had some limitations. First, this was a retrospective observational study and was susceptible to various biases, including selection bias. Second, we used the dipstick test to estimate proteinuria. Because proteinuria was assessed using a semiquantitative urine dipstick test, it may not accurately reflect the degree of proteinuria. Further evaluation with quantitative methods would be necessary to more accurately reassess proteinuria levels. Also, due to time constraints and cost considerations, markers of kidney damage, such as urine protein-to-creatinine ratio and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, were not assessed. These ratios provide valuable support to validate the results of this study. Third, the levels of estimated glomerular filtration rate, which were important parameters for renal disease and proteinuria, were not measured at NIHS during the inclusion period of our study. Fourth, the interpretation of our results must consider variations in the visual reading of dipstick strips, as well as the potential influence of exercise, dehydration, fever, infection, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and the use of medications. Unfortunately, our dataset did not include information on history of medications that could influence the development of proteinuria or VTE, such as anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers. Therefore, further studies including multivariable analyses adjusting for medication history are needed. Fifth, given the retrospective nature of this study, it was not feasible to establish a causal relationship or control the confounding variables. Sixth, although we showed a dose-response relationship between the severity of proteinuria and the incidence of VTE, participants in the improved group had the possibility of false-positive results, mild (+ 1) proteinuria, or occasional proteinuria at the health checkup. Seventh, in this study, VTE, including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary thromboembolism, and other venous thromboses, as well as comorbidities, were defined using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes. We considered the performance measures, such as the positive predictive value, for identifying VTE and comorbidities to be acceptable37,38,39,40,41,42,43. However, this remains a limitation of our study. Therefore, there is a possibility of random misclassification in the identification of VTE. Further large-scale studies based on more accurate diagnoses are warranted. Eighth, our dataset does not provide information on whether patients with persistent proteinuria received further diagnostic workup or clinical follow-up. Therefore, potential bias in the diagnosis of VTE could have occurred depending on the duration of follow-up among individuals with persistent proteinuria, which is a limitation of our study. Ninth, the occurrence of VTE, including deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary thromboembolism, and other venous thromboses, was observed between 7.0 and 10.8 years after the initial proteinuria test (Table S26 and S27). This delayed onset may suggest a lack of biological plausibility in the observed association, possibly due to the influence of other confounding variables. Caution is warranted when interpreting this relationship. Tenth, given the retrospective design of the study, there may be a risk of immortal time bias. Further research is warranted to address this issue. Finally, since this was an epidemiological study, the fundamental mechanisms underlying the association between changes in proteinuria and the occurrence of VTE could not be elucidated.

In conclusion, our study showed that the incidence risk of VTE was associated with change and severity of proteinuria status. Improvement in proteinuria may attenuate the occurrence of VTE.

Methods

Participants

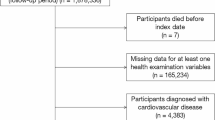

This study used data from the National Health Insurance Service-Health Screening (NHIS-HEALS) cohort dataset. The database includes demographics, socioeconomic status, and medical datasets for the diagnosis and treatment modality of participants aged ≥ 40 years who underwent free health checkups biannually. Details about the dataset have been previously reported44,45. Health checkup datasets include information on physical examination, lifestyle questionnaire, and laboratory findings, including a urine dipstick test for proteinuria. We analyzed data from 1,878,336 participants who underwent two successive health checkups during the initial period (2003 or 2004) and the subsequent period (2005 or 2006) (dataset number: NHIS-2021-1−715) through an identification and validation process46,47,48,49,50. Among the 1,878,336 participants, those who died before the index date (n = 7) and those with at least one missing data set (n = 164,275) were excluded. Additionally, participants with a history of VTE (n = 1,547) were excluded. Finally, 1,712,507 participants were included in this study (Fig. 2). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ewha Womans University Seoul Hospital (Institutional Review Board approval number: SEUMC 2023-05−020), which waived the requirement of informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study and the minimal risk of data collection to patients. The research was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments.

Changes in proteinuria and covariates

As part of a health checkup to detect proteinuria, a dipstick urinalysis was conducted on morning urine samples obtained after an overnight fasting period. Based on the change in color from yellow to blue, proteinuria was semi-quantitatively interpreted as “0,” “+1,” “+2,” “+3,” or “+4.” In this study, we divided the participants into four groups focused on the presence of proteinuria at the two consecutive health examinations: (1) normal (0 → 0), (2) proteinuria-improved (+ 1 → 0, + 2 → ≤ +1 [0 or + 1], ≥ +3 → ≤ +2 [0, + 1 or + 2]), (3) proteinuria-progressed (0 → ≥ +1, + 1 → ≥ +2, + 2 → ≥ +3), and (4) proteinuria-persistent (+ 1 → +1, + 2 → +2, ≥ +3 → ≥ +3).51 For the sensitivity analysis, we classified participants according to changes in the presence of proteinuria (Supplementary Method 1).

Detailed definitions of the covariates are provided in Supplementary Methods 2 and previous studies50,52,53. Data on variables such as age, sex, body mass index, household income, smoking status, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, and comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, cancer, and renal disease) were collected. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), a well-established tool, was used to assess comorbidities52,54,55.

Outcomes

The index date was defined as the date of the second health check-up. VTE includes deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary thromboembolism, and other venous thromboses. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary thromboembolism were defined as one or more claims of diagnostic codes for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary thromboembolism (I80.2, I80.3 and I26.0, I26.9), respectively. Other venous thromboses were defined as one or more claims of diagnostic codes for other venous thromboses (I82.9). Previous validation studies have confirmed the diagnostic accuracy of International Classification of Diseases-10 codes for VTE in the NHIS dataset56,57,58. The data were followed up from after the second visit up to December 31, 2020 or the first occurrence of VTE, whichever came first.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of the groups were compared using analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni post-hoc analysis for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. The cumulative incidence curve using 1-Kaplan–Meier survival curves was used to assess the association between the change in proteinuria status and the occurrence of VTE. To ensure balanced baseline characteristics and minimize potential confounding between the two groups, a 1:3 PSM approach was employed. Propensity scores were estimated using a multivariate logistic regression model including demographic, lifestyle, and clinical variables (age, sex, body mass index, household income, smoking status, alcohol consumption, regular exercise, comorbidities and CCI. The effectiveness of matching was evaluated using the standardized mean difference (SMD), with an absolute SMD value below 0.2 indicating an acceptable level of balance. The Cox proportional hazards model, presented as a hazard ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI), was used to assess the effects of changes in proteinuria status and severity of proteinuria between the two health checkups on the occurrence of VTE after adjusting for all potential confounding factors. The assumption of hazard proportionality was tested using the Shoenfeld residuals. No deviations from the proportional hazard assumption were observed. Additionally, a sensitivity and stratified analyses were performed to evaluate the combined effects of renal disease. Subgroup analysis was performed for pairwise comparisons to evaluate the change in the risk of VTE among participants who improved or progressed to proteinuria. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System software (SAS version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from NHIS-HEALS, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under the license for the current study; hence, they are not publicly available. However, the data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the National Health Insurance System.

References

Khan, F., Tritschler, T., Kahn, S. R. & Rodger, M. A. Venous thromboembolism. Lancet (London England). 398, 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32658-1 (2021).

Raskob, G. E. et al. Thrombosis: a major contributor to global disease burden. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 34, 2363–2371. https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.114.304488 (2014).

Lozano, R. et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet (London England). 380, 2095–2128. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61728-0 (2012).

Reitsma, P. H., Versteeg, H. H. & Middeldorp, S. Mechanistic view of risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 32, 563–568. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.242818 (2012).

Pastori, D. et al. A Comprehensive Review of Risk Factors for Venous Thromboembolism: From Epidemiology to Pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24043169 (2023).

Heit, J. A. et al. Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based case-control study. Arch. Intern. Med. 160, 809–815. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.160.6.809 (2000).

Iseki, K., Iseki, C., Ikemiya, Y. & Fukiyama, K. Risk of developing end-stage renal disease in a cohort of mass screening. Kidney Int. 49, 800–805. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.1996.111 (1996).

Cravedi, P. & Remuzzi, G. Pathophysiology of proteinuria and its value as an outcome measure in chronic kidney disease. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 76, 516–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12104 (2013).

Lim, D. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of urine dipstick for proteinuria in older outpatients. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 33, 199–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.krcp.2014.10.003 (2014).

Lim, W. H. et al. Proteinuria detected by urine dipstick test as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation: A nationwide Population-Based study. Sci. Rep. 7, 6324. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-06579-0 (2017).

Hemmelgarn, B. R. et al. Relation between kidney Function, Proteinuria, and adverse outcomes. JAMA 303, 423–429. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.39 (2010).

Bello, A. K. et al. Associations among estimated glomerular filtration rate, proteinuria, and adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrology: CJASN. 6, 1418–1426. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.09741110 (2011).

Perkovic, V. et al. The relationship between proteinuria and coronary risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 5, e207. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050207 (2008).

Htike, N., Superdock, K., Teehan, G., Thiruveedi, S. & Surkis, W. Evaluating proteinuria and nephrotic syndrome in patients with venous thromboembolism. Am. J. Med. Sci. 343, 124–126. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318223b95c (2012).

Baird, W. L. Jr. & Buchanan, D. P. The nephrotic syndrome following thrombosis of the inferior Vena Cava. Am. J. Med. 32, 128–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(62)90189-4 (1962).

Wattanakit, K., Cushman, M., Stehman-Breen, C., Heckbert, S. R. & Folsom, A. R. Chronic kidney disease increases risk for venous thromboembolism. J. Am. Soc. Nephrology: JASN. 19, 135–140. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2007030308 (2008).

Kato, S. et al. Relationship between proteinuria and venous thromboembolism. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis. 30, 281–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-010-0442-z (2010).

Mahmoodi, B. K. et al. Microalbuminuria and risk of venous thromboembolism. Jama 301, 1790–1797. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.565 (2009).

Kayali, F., Najjar, R., Aswad, F., Matta, F. & Stein, P. D. Venous thromboembolism in patients hospitalized with nephrotic syndrome. Am. J. Med. 121, 226–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.08.042 (2008).

Kumar, S., Chapagain, A., Nitsch, D. & Yaqoob, M. M. Proteinuria and hypoalbuminemia are risk factors for thromboembolic events in patients with idiopathic membranous nephropathy: an observational study. BMC Nephrol. 13, 107. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-13-107 (2012).

Königsbrügge, O., Lötsch, F., Zielinski, C., Pabinger, I. & Ay, C. Chronic kidney disease in patients with cancer and its association with occurrence of venous thromboembolism and mortality. Thromb. Res. 134, 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2014.04.002 (2014).

Folsom, A. R. et al. Chronic kidney disease and venous thromboembolism: a prospective study. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association -. Eur. Ren. Association. 25, 3296–3301. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfq179 (2010).

Ocak, G. et al. Chronic kidney disease stages 1–3 increase the risk of venous thrombosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 8, 2428–2435. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04048.x (2010).

Daneschvar, H. L., Seddighzadeh, A., Piazza, G. & Goldhaber, S. Z. Deep vein thrombosis in patients with chronic kidney disease. Thromb. Haemost. 99, 1035–1039. https://doi.org/10.1160/th08-02-0107 (2008).

Sturgill, B. C. & Rowe, C. T. Renal vein thrombosis and the nephrotic syndrome. Immunofluorescence studies. Arch. Intern. Med. 120, 708–711 (1967).

Leslom, A. N. et al. Prevalence of pulmonary thromboembolism in nephrotic syndrome patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Family Med. Prim. Care. 9, 497–501. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1076_19 (2020).

Remuzzi, G., Benigni, A. & Remuzzi, A. Mechanisms of progression and regression of renal lesions of chronic nephropathies and diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 116, 288–296. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci27699 (2006).

KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney international 102, S1-s127, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2022.06.008

Wang, A. et al. Changes in proteinuria and the risk of myocardial infarction in people with diabetes or pre-diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 16, 104. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-017-0586-7 (2017).

Park, S. K. et al. The association between changes in proteinuria and the risk of cerebral infarction in the Korean population. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 192, 110090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2022.110090 (2022).

Mahmoodi, B. K. et al. The impact of antiproteinuric therapy on the prothrombotic state in patients with overt proteinuria. J. Thromb. Haemostasis: JTH. 9, 2416–2423. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04525.x (2011).

32 Leizorovicz, A. et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of Dalteparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients. Circulation 110, 874–879. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000138928.83266.24 (2004).

Pedrinelli, R. et al. Microalbuminuria and endothelial dysfunction in essential hypertension. Lancet (London England). 344, 14–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91047-2 (1994).

Stehouwer, C. D. et al. Urinary albumin excretion, cardiovascular disease, and endothelial dysfunction in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Lancet (London England). 340, 319–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/0140-6736(92)91401-s (1992).

Massicotte-Azarniouch, D. et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients by albuminuria and estimated GFR. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 70, 826–833. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.07.003 (2017).

Machleidt, C. et al. Multifactorial genesis of enhanced platelet aggregability in patients with nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int. 36, 1119–1124. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.1989.310 (1989).

Liu, B. et al. Accuracy of venous thromboembolism ICD-10 codes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb. Update. 14, 100154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tru.2023.100154 (2024).

Kuang, A., Xu, C., Southern, D. A., Sandhu, N. & Quan, H. Validated administrative data based ICD-10 algorithms for chronic conditions: A systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Popul. Health. 72, 202744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeph.2024.202744 (2024).

So, L., Evans, D. & Quan, H. ICD-10 coding algorithms for defining comorbidities of acute myocardial infarction. BMC Health Serv. Res. 6, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-6-161 (2006).

Pan, J. et al. Assessing the validity of ICD-10 administrative data in coding comorbidities. BMJ health care Inf. 32, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjhci-2024-101381 (2025).

Yao, R. J. R. et al. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of identifying atrial fibrillation using administrative data: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Epidemiol. 11, 753–767. https://doi.org/10.2147/clep.s206267 (2019).

Oake, J. et al. Using electronic medical record to identify patients with dyslipidemia in primary care settings: international classification of disease code matters from one region to a National database. Biomedical Inf. Insights. 9, 1178222616685880. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178222616685880 (2017).

Baek, J. H. et al. Comparison of operational definition of type 2 diabetes mellitus based on data from Korean National health insurance service and Korea National health and nutrition examination survey. Diabetes Metabolism J. 47, 201–210. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2022.0375 (2023).

Song, S. O. et al. Background and data configuration process of a nationwide population-based study using the Korean National health insurance system. Diabetes Metabolism J. 38, 395–403. https://doi.org/10.4093/dmj.2014.38.5.395 (2014).

Seong, S. C. et al. Cohort profile: the National health insurance Service-National health screening cohort (NHIS-HEALS) in Korea. BMJ open. 7, e016640. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016640 (2017).

46 Woo, H. G., Kang, M. K. & Song, T. J. Association of predicted body composition with occurrence of atrial fibrillation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1159087. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2023.1159087 (2023).

Woo, H. G., Kim, D. H., Lee, H., Kang, M. K. & Song, T. J. Association between changes in predicted body composition and occurrence of heart failure: a nationwide population study. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1210371. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1210371 (2023).

Park, H., Chang, Y., Lee, H., Hong, I. & Song, T. J. Association of total cholesterol variability with risk of venous thromboembolism: A nationwide cohort study. PloS One. 18, e0289743. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0289743 (2023).

Chang, Y., Lee, H. & Song, T. J. Association of gamma-glutamyl transferase variability with risk of venous thrombosis. Sci. Rep. 13, 7402. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34368-5 (2023).

Park, J. et al. Association of atrial fibrillation with infectivity and severe complications of COVID-19: A nationwide cohort study. J. Med. Virol. 94, 2422–2430. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.27647 (2022).

Levey, A. S. et al. Change in albuminuria and GFR as end points for clinical trials in early stages of CKD: A scientific workshop sponsored by the National kidney foundation in collaboration with the US food and drug administration and European medicines agency. Am. J. Kidney Diseases: Official J. Natl. Kidney Foundation. 75, 84–104. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.06.009 (2020).

Kwon, H. S. et al. Five-Year community management rate for dementia patients: A proposed indicator for dementia policies. J. Clin. Neurol. 18, 24–32 (2022).

Lee, K. et al. Oral health and Gastrointestinal cancer: A nationwide cohort study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 47, 796–808. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13304 (2020).

Chang, Y., Woo, H. G., Park, J., Lee, J. S. & Song, T. J. Improved oral hygiene care is associated with decreased risk of occurrence for atrial fibrillation and heart failure: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 27, 1835–1845. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319886018 (2020).

Sundararajan, V. et al. New ICD-10 version of the Charlson comorbidity index predicted in-hospital mortality. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 57, 1288–1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.03.012 (2004).

Kim, H. Y. et al. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism and treatment pattern of oral anticoagulation in Korea, 2009–2016: a nationwide study based on the National health insurance service database. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 29, 265–278 (2021).

Kim, S. Y. et al. Venous thromboembolism risk in Asian patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A Population-Based nationwide inception cohort study. Gut Liver. 16, 555–566. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl210190 (2022).

Jang, M. J., Bang, S. M. & Oh, D. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in korea: from the health insurance review and assessment service database. J. Thromb. Haemost. 9, 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.04108.x (2011).

Acknowledgements

We received valuable advice from a professor of nephrology (Hyung Jung Oh) and we are grateful for it. Hyung Jung Oh is affiliated with the Department of Nephrology, Sheikh Khalifa Specialty Hospital, Ras Al-Khaimah, United Arab Emirates.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2022-0-00621, RS-2022-II220621, Development of artificial intelligence technology that provides dialog-based multimodal explainability). This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: RS-2023-00262087 to T-JS). This research was supported by the BK21 Fostering Outstanding Universities for Research (FOUR) funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE, Korea) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-5199990614253, Education Research Center for 4IR-Based Health Care). The funding source had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Research conception and design, H.G.W. and T.J.S.; Data acquisition, H.G.W. and T.J.S.; Data analysis and interpretation, H.G.W. and T.J.S.; Statistical analysis, H.G.W. and T.J.S.; Drafting of the manuscript, H.G.W. and T.J.S.; Critical revision of the manuscript, H.G.W. and T.J.S. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Woo, H.G., Song, TJ. Improvement in proteinuria attenuates the occurrence of venous thromboembolism: A population-based cohort study. Sci Rep 16, 52 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29288-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29288-5