Abstract

Chemical castration represents a non-surgical alternative to achieve male sterility by inducing azoospermia, with growing interest in nanoparticle-based agents owing to their targeted toxicity. This study aimed to determine whether intratesticular administration of copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs) is effective in the chemical castration of male mice, and whether biochemical and histological changes can be assessed. Fifty-six adult male mice were divided into seven groups (n = 8 per group): a surgically castrated cohort, a control group, a sham group, and four experimental groups receiving CuO NPs at concentrations of 5, 10, 20, and 40 mg/mL. The assessment included fertility analysis after 30 days of treatment, sperm quality, testicular tissue, histological parameters, oxidative status, and gene expression. Testis weight, sperm parameters, and testosterone levels were significantly reduced by exposure to CuO NPs, but oxidative stress and DNA damage increased in a dose-dependent manner. Higher doses also decreased the expression of anti-apoptotic genes (Bcl-2) and increased that of pro-apoptotic genes (Bax and caspase-3). The correlation between these alterations and lower fertility indices highlighted the reproductive toxicity of CuO NPs. There were no noticeable differences between the control and sham groups for comparison. These findings suggest that intratesticular CuO NPs have potential as a method for chemical castration, offering a less invasive and more economical option for population-control applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Castration may be necessary for inguinal hernia, spermatic cord torsion, orchitis, epididymitis, varicocele, hydrocele, neoplasia, and testicular trauma1. Various surgical and non-surgical techniques have been used in animals for this purpose. Historically, the standard method of male sterilization has been surgical castration. However, this strategy has known disadvantages, such as its limited applicability, the need for specialized medical equipment, anesthesia, qualified veterinary personnel, sterile surgical environment, high cost, time commitment, postoperative care needs, and possible complications2,3.

Several attempts have been made to sterilize males by using various pharmacological agents. Hormone injections have been tested in several studies to sterilize male animals of multiple species, however, these procedures have not been successful in achieving permanent sterilization4. According to research, chemical castration can be performed with any substance that can prevent spermatogenesis by preventing the release of gonadotropins, especially luteinizing hormone5. Gonadotropin-specific antibodies have also been produced using immunological methods with varying degrees of success6. An ideal chemical sterilant agent should have no harmful side effects and efficiently inhibit libido, androgenesis, and spermatogenesis7. Animal species have been chemically sterilized without surgery using a variety of chemicals including lactic acid8, glycerol9, arginine-neutralized zinc gluconate10, calcium chloride11, ferric chloride, ferrous sulfate4, and cadmium chloride12. After injecting these substances into the testicles, pain, fever, and severe inflammation (orchitis) can occur. Glycerol, lactic acid, and cadmium chloride are among the substances that selectively destroy testicular tissue and cause reversible damage to testicular tissue9,13.

Ingestion, inhalation, skin absorption, injection, and implantation are routes through which nanoparticles (NPs) can enter the body owing to their small size and biocompatibility. Once inside the body, they can affect several physiological functions14. Chronic exposure to NPs has been linked to several diseases in animals in several studies, including irreversible testicular damage, lung damage, hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity, and renal toxicity15,16,17. Recent reviews have highlighted the toxicological effect of NPs on the reproductive system, including oxidative stress and genotoxicity in testicular cells18. As a vital component of healthy physiological processes, copper (Cu) is involved in the metabolism of drugs, xenobiotics, carbohydrates, and the antioxidant defense system, all essential for human and animal life19. Cu can enter the body in several ways, including inhalation, eating, drinking, and skin contact with Cu-containing soil, water, and air. When copper intake exceeds the range of biological tolerance, adverse effects such as liver, kidney, immune system damage, and gastrointestinal disorders may occur20,21. Copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO NPs), widely used in catalysis, cosmetics, and electronics, pose potential health risks due to their increasing applications, prompting intensive research into their in vitro and in vivo toxicity22. There is increasing evidence that oxidative stress, which includes the induction of lipid peroxidation and ROS-dependent DNA damage, is the mechanism by which CuO NPs cause toxicity23. Studies on cadmium, a similar heavy metal, have demonstrated oxidative toxicity and apoptosis in spermatogenic cells, underscoring the relevance of metals to reproductive toxicology24. Intratesticular injections of CuO NPs in male mice have not been documented. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the application of CuO NPs for chemical castration of male mice. For this purpose, differences in sperm parameters, oxidation status, histopathological findings, testosterone levels, apoptosis gene expression, and in vivo fertility indices were examined.

Results

Serum testosterone levels

Table 1 shows serum testosterone levels on day 30. Control (1.72 ± 0.03 ng/mL) and sham (1.71 ± 0.02 ng/mL) groups showed no difference (p > 0.05). Levels decreased dose-dependently: CuO NPs-5 (1.64 ± 0.03 ng/mL, p < 0.05), CuO NPs-10 (1.51 ± 0.06 ng/mL, p < 0.01), CuO NPs-20 (1.18 ± 0.04 ng/mL, p < 0.001), and CuO NPs-40 (0.74 ± 0.06 ng/mL, p < 0.001). These reductions align with CuO NPs-induced Leydig cell damage, supporting the hypothesis of reproductive toxicity.

Sperm parameters

Control and sham groups had similar sperm concentrations (36.46 ± 2.14 × 10⁶/mL and 36.10 ± 2.25 × 10⁶/mL; p > 0.05). Sperm concentration decreased with increasing CuO NPs doses, with the lowest observed in the CuO NPs-40 group (11.81 ± 1.94 × 10⁶/mL; p ≤ 0.001; Table 2).

Total motility (TM) and progressive motility (PM) followed similar trends, with the control and sham groups having the highest values (81.07 ± 2.03% and 80.33 ± 2.91% for total motility; 45.20 ± 1.86% and 44.93 ± 1.33% for PM; p > 0.05). The CuO NPs-40 group showed significantly reduced motility parameters (32.75 ± 1.22% total motility and 12.39 ± 0.11 PM; p < 0.001 vs. control) (Table 2).

The average path velocity (VAP), curvilinear velocity (VCL), and straight-line velocity (VSL; all first mentions redefined) were significantly reduced at higher CuO NPs doses, with the CuO NPs-40 group consistently exhibiting the lowest values (Table 2). VCL (curvilinear velocity): Similar trends were observed for VCL, with the control (84.78 ± 2.01 μm/s) and sham (83.21 ± 2.53 μm/s) groups showing the highest values and CuO NPs-40 the lowest (51.37 ± 1.22 μm/s ; p < 0.001) (Table 2). VSL (straight-line velocity): VSL decreased significantly with increasing doses, from 24.49 ± 1.28 μm/s in the control group to 8.24 ± 0.37 μm/s in the CuO NPs-40 group (p < 0.001; Table 2). LIN (linearity): Linearity values remained relatively consistent across groups (0.23 ± 0.02 in the control group to 0.21 ± 0.02 in the CuO NPs-40 group; p > 0.05), indicating minor dose-dependent changes. ALH (amplitude of lateral head displacement): ALH values were highest in the control group (2.69 ± 0.01 μm/s) and lowest in the CuO NPs-40 group (0.76 ± 0.02 μm; p ≤ 0.001). STR (straightness): STR values showed minimal differences between groups (0.84 ± 0.01 in the control group to 0.82 ± 0.02 in the CuO NPs-40 group ; p > 0.05) (Table 2). BCF (beat-cross frequency): BCF decreased significantly with increasing CuO NPs doses, from 14.78 ± 0.73 Hz in the control group to 4.69 ± 0.64 Hz in the CuO NPs-40 group (p < 0.001). These motility impairments suggest oxidative disruption of mitochondrial function, linking to DNA damage observed later.

Sperm viability, DNA damage, and morphology

Table 3 shows viability, plasma membrane functionality (PMF), DNA damage, and morphology. Control and sham groups showed the highest sperm viability (89.53 ± 2.40% and 88.39 ± 2.68%) and PMF (84.04 ± 2.75% and 83.53 ± 2.19%; p > 0.05). Viability and membrane functionality decreased significantly at higher CuO NPs doses, with CuO NPs-40 group showing the lowest values (41.60 ± 1.04% and 33.47 ± 1.13%; p < 0.001). DNA damage was minimal in the control and sham groups (3.17 ± 0.18% and 3.83 ± 0.21%, respectively; p > 0.05) but increased significantly with the CuO NPs doses and peaked in the CuO NPs-40 (25.85 ± 1.43%; p < 0.001). The abnormal morphology increased with CuO NPs doses, with the highest value observed in the CuO NPs-40 group (50.61 ± 1.91%; p ≤ 0.001).

Histological parameters

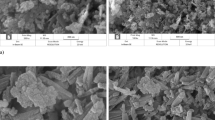

Control and sham groups showed similar testis and epididymis weights, while a dose-dependent decrease was noted in the CuO NPs-treated groups (Fig. 1). The CuO NPs-40 group had the lowest testis (0.20 ± 0.02 g) and epididymis (0.081 ± 0.002 g) weights (p < 0.001; Table 4). The Johnsen and Cosentino scores were significantly reduced in the CuO NPs-treated groups, indicating testicular damage (p < 0.01 for Johnsen, p < 0.001 for Cosentino). The CuO NPs-40 group had the lowest Johnsen score (1.50 ± 0.03) and the highest Cosentino score (3.86 ± 0.02). The Sertoli cell index, repopulation index, and spermiogenesis index were significantly reduced with increasing doses of CuO NPs (all p < 0.001; Table 4). These histological changes corroborate oxidative stress as a mediator of toxicity.

Testicular histo-architecture was compared across different experimental groups: (A) control; (B) Sham; (C) 5 mg/mL CuO NPs; (D) 10 mg/mL CuO NPs; (E) 20 mg/mL CuO NPs; (F) 40 mg/mL CuO NPs. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining at 400× magnification was used. The black arrows represent sperm density in the seminiferous tubule lumens, and it was significantly lower in group (F). Groups (C–E) also showed a decline in sperm density. The asterisks indicate that the germinal epithelium was disorganized and disrupted in different groups, with group F experiencing the most severe effects. However, groups (C–E) also experienced disruptions.

Oxidative stress markers

The total antioxidant capacity (TAC), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase (CAT) levels were significantly reduced in the CuO NPs-treated groups, with the CuO NPs-40 group having the lowest values (TAC: 0.53 ± 0.005 mmol/g protein; GPx: 0.12 ± 0.002 U/mg protein). ; SOD: 2.24 ± 0.03 U/mg protein; CAT: 0.56 U/mg protein; all p < 0.001 vs. control). The malondialdehyde (MDA) values were significantly increased in the CuO NPs-treated groups, with the highest values observed in the CuO NPs-40 group (14.39 ± 1.24 nmol/g protein ; p < 0.001) (Table 5). Elevated MDA and reduced antioxidants directly link to the observed DNA damage and motility deficits.

Gene expression levels

Table 6 shows the gene expression levels of Bax, caspase-3, and Bcl-2. Bax and caspase-3 expression were significantly upregulated in the CuO NPs-treated groups, with the highest values in the CuO NPs-40 group (fold changes: Bax 3.2 ± 0.15, caspase-3 2.8 ± 0.12; p < 0.001). Bcl-2 expression was significantly downregulated in CuO NPs-treated groups, with the lowest values occurring in the CuO NPs-40 group (0.41 ± 0.02-fold change; p < 0.001) (Table 6).

Fertility indices

The fertility indices were significantly lower in the CuO NPs groups than in the control and sham groups, as shown in Table 7 (all p < 0.01). The group that received the injection of 40 mg/ml CuO NPs had the lowest fertility index (15.2%; p ≤ 0.001). This means that fertility decreased in a dose-dependent manner with higher doses of CuO NPs.

Discussion

Testosterone levels and spermatogenesis

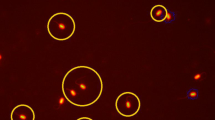

The present study investigated the effectiveness of intratesticular injections of CuO NPs for chemical sterilization in male mice (Fig. 2). Castration of animals using chemical, surgical, and mechanical means has been the subject of previous studies25,26,27,28. Due to the advantages and disadvantages of surgical castration, non-invasive chemical techniques that can completely stop spermatogenesis, androgenesis, and libido are currently being investigated. The prerequisites for these techniques are large-scale effectiveness, a high safety profile, and irreversibility after a single treatment13. However, it hasn’t proven easy to find a method of terminating fertility that is 100% effective and free of side effects. Irreversible or permanent loss of fertility is the ultimate goal of all castration procedures, including hormonal, chemical, and surgical procedures. Previous studies have reported the absence of side effects such as diarrhea, lethargy, vomiting, scrotal ulcers, and dermatitis after intratesticular injections. This is similar to our finding that no apparent side effects occurred3,29.

It has been shown that CuO NPs are a sensitive target of mammalian testes, and their accumulation in the male reproductive system can cause severe reproductive damage30. This study found that administering CuO NPs may have significantly reduced testosterone levels, consistent with Zheng et al. (2023)31, indicating Leydig cell damage. Critically, while our results align with Zheng et al., they contrast with studies on other NPs like TiO2, which show variable hormone disruption depending on dose and exposure route, suggesting CuO NPs’ specificity to Leydig cells via ROS-mediated pathways. The study suggests that NP-induced testicular damage and inhibition of spermatogenesis in male mice may be related to changes in testicular gene expression and male sex hormone levels. For example, partial vacuolization of seminiferous tubules and increased serum testosterone levels suggest impaired male reproductive function in mice exposed to black carbon nanoparticles32. In our study, the histomorphometric indices of testicular tissue decreased in parallel with the decline in testosterone levels. The measured structure and function indices of the CuO NPs-treated groups were significantly lower than those of the control group. The significant decrease in testosterone levels observed in the CuO NPs-treated group suggests that CuO NPs may be the leading cause of damage to testicular Leydig cells, the primary endogenous cells responsible for the production of testosterone33. Copper oxide nanoparticles may affect the ability of the hormone testosterone to bind to receptors, and therefore its blood levels, thereby altering androgen-dependent biological functions34. It is reasonable to assume that intratesticular injections of CuO NPs may reduce spermatogenesis by impairing testosterone production in the testes since testosterone is involved in spermatogenesis35. Our results contradict a study on donkeys that found that chemical castration and intramuscular calcium chloride injection did not reduce testosterone levels (potentially due to species-specific sensitivity or dosing differences36. This highlights a need for comparative studies across species.

Sperm parameters and quality

Testicular toxicity caused by chemicals is frequently measured using sperm motility37. A key consideration when evaluating sperm fertilization potential is motility38. In the female reproductive system, sperm migration depends on progressive motility, or the sperm’s capacity to travel in a particular direction. The cyclic adenosine monophosphate pathway-dependent protein kinase, protein kinase A, and the Ca2 + pathway are among the metabolic and regulatory pathways controlling sperm motility39,40,41. Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthesis and oxidative phosphorylation are two processes that mitochondria use to maintain normal cellular function and energy metabolism42. CuO nanoparticles can potentially cause aberrant sperm counts, semen quality, and androgen levels in adult mice30. CuO NPs administered intratesticularly to mice in our study significantly reduced both total and progressive sperm motility, as well as other characteristic sperm motility parameters from the cauda epididymis (p < 0.001). Numerous regulatory systems and metabolic processes influence sperm motility. The calcium pathway and protein kinase A, which depends on the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) pathway, are two significant mechanisms that control sperm motility. Thus, these mechanisms could be harmed by CuO NPs39,40,41. Likewise, an additional investigation demonstrated that intra-testicular mannitol injection could reduce motility properties29. Furthermore, intratesticular injection of mannitol and hypertonic saline can reduce donkeys’ total and progressive motility3. Individual susceptibility, dosage, and duration of exposure may influence the specific effects of copper oxide nanoparticles on sperm properties. They have been shown to cause sperm toxicity and, in particular, to alter sperm properties43. Upon contact with copper oxide nanoparticles, sperm motility, and speed may decrease, and sperm viability may decrease44.

A recent study showed that the number of sperm in mice testicles significantly decreased when CuO NPs were injected. In one study, mice given CuO NPs also showed a decrease in the weight of their reproductive organs45. The vascular disease caused testicular cells to undergo apoptosis, which slowed down the process of sperm formation. This reduction can be linked to testicular parenchyma shrinkage, seminal epithelium breakdown, and a subsequent drop in spermatogenesis. Because the cauda epididymis stores sperm, a decrease in epididymal sperm concentration indicates a decline in testicular sperm production46. Several studies have shown that sperm survival and PMF integrity are negatively affected by various chemicals that disrupt membrane integrity, resulting in increased damage47,48,49,50. Exposure to CuO NPs increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lipid peroxidation, reduced sperm viability, and inhibited mitochondrial activity. Following exposure to CuO NPs, morphological alterations and DNA damage have also been noted44. These results and antioxidant rescue studies44 indicate that oxidative stress is the primary cause of CuO NPs’ sperm toxicity effects. The control and treatment cohorts’ sperm morphologies differed significantly, according to the current study. Similarly, an intra-testicular injection of mannitol in rats was found to increase aberrant sperm morphology and decrease PMF and viability29. Donkey sperm quality may be reduced by intra-testicular infusion of hypertonic mannitol and saline, according to another study3. Significant alterations in sperm properties, such as quality, motility, and defective sperm, were noted in mice given zinc oxide nanoparticles daily for up to 35 days51. As stated by Kwak et al. (2013)10, sodium chloride injections can potentially cause severe degenerative alterations and widespread immune cell infiltration into the seminiferous tubules of the testicles. According to the results of our investigation, the groups that received intra-testicular injections of CuO NPs experienced more DNA damage than the control group (p < 0.001). Our results are consistent with a study that found that injecting male rats with mannitol and HTS could increase the damage to their sperm DNA29. Gromadzka-Ostrowska et al. (2012)52 conducted a survey that showed that the number of nonviable sperm increased while the quantity of epididymal sperm decreased. Additionally, it was discovered that a single intravenous administration of silver nanoparticles significantly increased the amount of DNA damage in germ cells. Zeini et al. (2010)53 showed that DNA strands can break apart due to imperfect and incomplete spermatogenesis.

Oxidative stress and mechanisms

The higher concentration of polyunsaturated fatty acids in sperm membranes makes testicular tissue more susceptible to oxidation54. Intracellular components are destroyed when plasma membrane lipids are peroxidized and damaged due to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) in testicular tissue55. According to the results of the study, the groups exposed to CuO NPs had significantly lower levels of CAT, GPx, SOD, and TAC (all p < 0.001). In addition, the testicular tissue of the CuO NPs groups had significantly higher levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) (p < 0.001). Numerous studies indicate that oxidative stress is a significant factor in cell death, as extracellularly distributed copper ions account for less than half of the total cytotoxicity of CuO NPs56,57. Consequently, intracellular copper triggers the oxidative cascade that ultimately leads to DNA damage and cell death by increasing the generation of ROS and decreasing glutathione (GSH)56,57. The decrease in the activities of testicular GPx, SOD, and glutathione S-transferase (GST) enzymes - all essential radical scavengers in the male reproductive organs - further proves that the administration of CuO NPs increased the formation of free radicals in the testes58. Our study supported the findings of Baqerkhani et al. (2024)3, who showed that intratesticular administration of saline and hypertonic mannitol could reduce oxidative status. Abou-Khalil et al. (2020)11 found that chemical castration reduced the TAC of male donkeys. Recent updates on heavy metal toxicity, such as cadmium, emphasize ROS-mediated pathways similar to those induced by CuO NPs, including genotoxicity and apoptosis59. Expanding on molecular pathways, CuO NPs trigger cuproptosis via copper-dependent mitochondrial lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis through iron dysregulation, amplifying ROS-induced damage beyond traditional apoptosis. Critically, this differs from organic toxins, where antioxidant pathways dominate, highlighting CuO NPs’ unique ion-release mechanism60.

Histopathology and apoptosis

The study’s results showed significant changes in several indicators comparable to the observed atrophy of the seminiferous tubules. According to histopathological analyses of their epididymis, the presence of spermatozoa in the epididymal lumen was significantly reduced in mice treated with CuO NPs. Poor spermatogenesis, testicular degeneration, parenchymatrophy, and seminiferous epithelium degeneration are possible causes of the decline in sperm count. Furthermore, our investigation showed that the groups treated with CuO NPs had significant immune cell infiltration, coagulative necrosis in all testes, and degenerative changes in seminiferous tubules. Degenerative changes or physical exhaustion of the germ cells can cause vacuole formation in the germ cells within the seminiferous tubules. This could be a precursor to Sertoli cell disorders61,62. In addition, it may indicate fluid imbalances caused by Sertoli cells63. Testicular cell atrophy manifests histologically as the partial or complete absence of mature spermatids in the tubular lumen. These results are consistent with previous research in this area. According to histopathological analyses of testicular tissue samples from male mice exposed to CuO NPs, CuO NPs can significantly reduce the weight of prostate, testes, epididymis, and seminal vesicles64. CuO NPs have been shown to alter the structure and function of gonadal tissue in male mice, which can lead to oxidative stress and cell death65. A study by Baqerkhani et al. (2024)3 found that injecting hypertonic mannitol and saline into donkeys’ testes reduced the histological parameters’ quality. Previous studies by Canpolat et al. (2016)66 also showed comparable results, with dogs treated with a sodium chloride solution exhibiting reduced sperm parameters and impaired spermatogenesis. Talebi et al. (2011)67 investigated how zinc oxide nanoparticles affect testicular tissue. They found that administering these nanoparticles to mice caused histopathological changes such as germ cell proliferation and epithelial vacuolization67.

According to Goslvez et al. (2015)68, apoptotic markers such as Fas, Bcl-X, p53, and Annexin V in both testicular and mature sperm demonstrated that apoptosis plays a role in the formation of DNA breaks. Apoptosis is crucial in the evolutionary process of mammals. It is a quality control mechanism that removes broken, defective, abnormal, or mispositioned cells69. According to our study, Bax and caspase-3 gene expression were significantly upregulated in the CuO NPs groups (p < 0.001), while Bcl-2 gene expression was significantly downregulated. This study supported the results of other studies showing that NP exposure resulted in adverse effects and infection of testicular tissue. The accumulation of these particles and the hydrogen-induced conversion of CuNPs into copper (II) ions – which are highly harmful to tissue – are partly responsible70,71. In a previous study, hypertonic mannitol and saline increased Bax gene expression and decreased Bcl-2 gene expression in these groups3—Bcl-2, as reported by Ozen et al. (2008)72, is an anti-apoptotic protein that delays the onset of apoptosis by preventing the activation of the caspase protein. This is achieved by preventing the Bax protein from penetrating the mitochondrial membrane and causing the release of cytochrome c. Numerous studies have shown free radicals to phosphorylate and modify Bcl-2 proteins, which serve as markers of apoptosis73.

Fertility implications, limitations, and future directions

NPs, including gold and TiO2 NPs, were highly toxic to Leydig cells, as evidenced by the concentration of sex hormone levels. Nanoparticle accumulation reduced fertility and impaired offspring growth45,74. This may be due to a decline in serum testosterone levels and sperm quality. Furthermore, the reduced fertility could be due to changes in the plasma membrane75. Moreover, Lu et al. (2018)76 and Zhang et al. (2019)77, suggest that sperm motility, viability, and DNA damage may have decreased due to a decrease in antioxidant enzyme activities, potentially affecting sperm fertilization capacity. Our study confirms these results, which show that applying CuO NPs can reduce testicular tissue cytoarchitecture and sperm properties, ultimately reducing the fertility index in mice. Regarding reversibility, studies indicate persistent testicular impairment even 140 days post-exposure discontinuation, suggesting irreversible damage at higher doses; this contrasts with lower-dose effects that may partially recover, warranting long-term monitoring78.

Limitations include the small sample size (n = 8), which may limit generalizability, and the focus on mice, raising translational concerns to humans or larger animals. While no systemic side effects were observed, long-term reversibility remains unclear, and public health applications for population control require ethical scrutiny beyond animal models. Additionally, the study did not assess chronic exposure or multi-generational effects, potentially underestimating cumulative toxicity. Future studies should assess reversibility over extended periods, human-relevant doses, and protective antioxidants like quercetin against NP-induced genotoxicity59. Further, investigate cuproptosis/ferroptosis pathways for targeted interventions60.

Conclusion

The current study revealed that CuO NPs caused oxidative stress by disrupting the osmotic balance in testicular cells. An interesting finding of the study was that exposure to CuO NPs activated the inflammasome by increasing ROS levels and further stimulated apoptosis in the testicular tissue of mice through altered expression of genes. This toxic biochemical stress impairs androgen access and energy metabolism, damages sperm DNA, causes functional damage to the plasma membrane, increases expression of apoptotic genes, and may harm the reproductive system of male mice. These dose-dependent effects highlight CuO NPs’ potential in chemical castration models, but further validation is needed. In the future, intra-testicular injection of these substances may offer a non-surgical alternative to surgical castration for the sterilization of rodents, with implications for veterinary population control. Furthermore, more research is needed to determine whether the degenerative damage caused by CuO NPs is reversible and to study their long-term effects, including translational safety to other species.

Methods

Chemicals

The CuO NPs in monoclinic form, 25–55 nm size, and 99.9% purity were purchased from NANOSHEL company (CAS no: 1317-38-0) in Punjab, India. We also bought all necessary chemicals from reliable suppliers, including Merck and Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany).

Animals

Fifty-six adult male mice, aged 6–8 weeks and weighing 20–25 g, were obtained from the Animal Resource Center, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran. Additionally, untreated virgin female mice, aged 6–8 weeks and weighing 18–22 g, were used for the fertility index study. Mice were maintained in a typical environment with temperature control (20–22 °C), ventilation, a 12:12-hour light-dark cycle, and humidity (50 ± 10%). The animals were housed in plastic cages, fed regular laboratory chow, and had unrestricted access to tap water. They were acclimatized one week before the experiment. The sample size (n = 8 per group) was determined via power analysis to detect a 30% change in sperm motility with 80% power and α = 0.05, minimizing animal use in line with ethical guidelines.

Experimental protocol

After acclimatization, mice were divided into seven groups (n = 8 each): control, sham, surgically castrated, and four CuO NPs groups (5, 10, 20, and 40 mg/mL):

-

Control: All male testicles were in good condition.

-

Sham: Received intratesticular injection of normal saline.

-

CuO-NPs-5: Received 5 mg/mL CuO NPs (100 µL per testis) injected into the distal testis toward the epididymal tail79.

-

CuO NPs-10: Received 10 mg/mL CuO NPs (100 µL per testis) injected into the distal testis toward the epididymal tail79.

-

CuO NPs-20: Received 20 mg/mL CuO NPs (100 µL per testis) injected into the distal testis toward the epididymal tail79.

-

CuO-NPs-40: Received 40 mg/mL CuO NPs (100 µL per testis) injected into the distal testis toward the epididymal tail79.

-

Surgically Castrated: Underwent bilateral orchiectomy.

Doses were selected based on reported LD50 values for CuO NPs in rodents (approximately 400 mg/kg body weight), scaled for intratesticular administration to achieve dose-dependent effects without systemic lethality79. Injections were administered using a 26-gauge needle under anesthesia (xylazine 10 mg/kg i.p., ketamine 150 mg/kg i.p.)80. Analgesia (buprenorphine 0.05 mg/kg s.c.) was provided post-injection to minimize distress during retro-orbital blood collection.

Blood collection and testosterone levels

On days 0 and 30, approximately 0.5 mL of blood was collected from the retroorbital sinus of each mouse using a microhematocrit capillary tube into precooled EDTA-containing microtubes. Blood was centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and plasma was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 20°C81. Testosterone was measured using an ELISA kit (Monobind Inc., Lake Forest, CA, USA). A 10 µL sample was added to wells with 100 µL testosterone-HRP conjugate, incubated for 1 h at room temperature, washed with 300 µL HRP wash buffer, and incubated with 100 µL TMB substrate for 15 min in the dark. Absorbance was read at 450 nm after adding 100 µL stop solution29.

Collection of organs from male mice and epididymal sperm collection

At the end of the experiment, all mice were weighed before euthanasia. Euthanasia was performed via intraperitoneal (IP) injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), sourced from Alfasan, Kortenhoef, Netherlands82. Testes and epididymides were removed, weighed, and recorded relative to body weight. The cauda epididymis was minced in 1 mL human tubal fluid (HTF) medium and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 30 min49,50,83.

Sperm analysis

Epididymal sperm count

The sperm were diluted 1:5 with distilled water and counted using a Neubauer hemocytometer (BrandTM, Wertheim, Germany). Epididymal tissue was weighed using a precision balance (SartoriusTM, Göttingen, Germany, 0.0001 g). Sperm concentration was calculated as 10⁶/mL per gram of tissue84.

Epididymal sperm motility

Kinetic parameters were assessed using a CASA system (Test Semen 3.2, Videotest, St. Petersburg, Russia). A 7 µL sperm sample was placed in a pre-warmed (37 °C) slide chamber, and at least 500 sperm were analyzed at 60 Hz. Parameters included VAP ≥ 50.0 μm/s, straightness ≥ 50%, cell size 13 pixels, VCL > 180 μm/s, linearity < 38%, and ALH > 9.5 μm (thresholds based on WHO guidelines for rodent sperm analysis85. A 10 µL sperm suspension was examined on a microscope slide using a phase-contrast microscope (Olympus BX41, Tokyo, Japan) to confirm motility41.

Plasma membrane function (PMF), sperm viability and morphology, and DNA damage assessment

Sperm viability and morphology were assessed using eosin-nigrosin staining85. A 10 µL sperm sample was mixed with 20 µL 1% eosin and 30 µL 10% nigrosin, smeared on a slide, and examined at 400× magnification using a light microscope (Olympus BX41, Tokyo, Japan). Viable sperm remained unstained; non-viable sperm stained red. Abnormal morphology (e.g., head, neck, tail defects) was quantified in 200 sperm41.

PMF was evaluated using the hypoosmotic swelling (HOS) test86. A 10 µL sperm sample was mixed with 100 µL hypoosmotic solution (1.351 g/L fructose, 0.735 g/L sodium citrate), incubated at 37 °C for 1 h, and examined at 400× magnification. Sperm with coiled/swollen tails indicated intact membranes41.

Acridine orange (AO) staining87: Smears were fixed in Carnoy’s solution (methanol: acetic acid, 3:1) for 2 h, air-dried, and stained with AO (1 mg/1000 mL water) for 5 min at 4 °C in the dark. A fluorescence microscope (Nikon GS7, Kyoto, Japan) at 400× magnification distinguished double-stranded DNA (green) from single-stranded/damaged DNA (yellow/red). At least 200 sperm were evaluated41.

Histomorphometry and histopathology of the testes

A 10% formalin solution was used to preserve the testes of the mice, which were then dehydrated with ethanol and embedded in paraffin. Using an Olympus light microscope model BH-2 (Tokyo, Japan), thin slices seven µm thick were prepared with a microtome, stained with H&E stain, and observed. Spermatogenesis was evaluated in 200 seminiferous tubules using the Johnsen score (Table 8) (blinded scoring by two independent pathologists to reduce bias)88. Seminiferous tubule diameter (STsD) was measured using a calibrated ocular micrometer across 200 cross-Sect88. In addition, an established methodology was used to evaluate testicular injury (Cosentino scoring system), tubular differentiation index (TDI), spermiogenesis index (SPI), Leydig cell nuclear diameter (LCND), repopulation index (RI), mitotic index (MI), and Sertoli cell index (SCI)89. The relative index measures the percentage of tubules containing germ cells that have progressed to the mid-spermatogonial stage or beyond90.

A measure of the percentage of cells lost during cell division is the mitotic index (MI), which indicates the ratio of round spermatids to pachytene primary spermatocytes91. Following the instructions of Elias and Hyde, a calibrated ocular micrometer was used to measure the Leydig cell nuclear diameter (LCND)92. The Cosentino grading system93 was used to determine the extent of testicular injury, which divides testicular architecture into four grades. Grade 1 denotes standard testicular architecture; Grade 2 means less ordered, disjointed germ cells and densely packed seminiferous tubules; Grade 3 denotes disordered, exfoliated germ cells with shrunken, pyknotic nuclei and less distinct edges of the seminiferous tubules; and grade 4 shows densely packed seminiferous tubules along with coagulative necrosis of the germ cells—the percentage of germ cells with at least three complete developments in the seminiferous tubules94. The ratio of sperm typically located in the seminiferous tubules95.

Evaluation of enzymatic antioxidant activity

Testicular tissue (20–30 mg) was homogenized in 1000 µL lysis buffer, centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 15 min, and the supernatant analyzed. Total protein was quantified using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with bovine serum albumin as the standard96.

The TAC assay kit determined the testis’s total antioxidant capacity (TAC) (Naxifer; Navand Salamat Company, Urmia, Iran). The results were expressed as nmol/mg protein41.

A glutathione peroxidase (GPx) kit (NagpixTM; Navand Salamat Company, Urmia, Iran) was used to measure the amounts of GPx in the samples. The results were expressed as mU/mg protein41.

The superoxide dismutase (SOD) content in the testis samples was determined using a commercial SOD kit (Nasdox; Navand Salamat Company, Urmia, Iran). The results were expressed as U/mg protein41.

Catalase activity (CAT) was measured using a commercially available CAT kit (NactazTM Catalase Activity Assay Kit; Navand Salamat Company, Urmia, Iran). The results were expressed as U/mg protein41.

MDA levels were measured using a commercial kit (Navand Salamat), with absorbance read at 532 nm on a spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA)41.

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), cDNA synthesis and RNA extraction

cDNA was synthesized using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). A 20 µL reaction with 1 µg RNA, 1 µL random hexamer primer, 4 µL 5× reaction buffer, 1 µL RNase inhibitor, 2 µL dNTP mix, and 1 µL RevertAid reverse transcriptase was incubated at 42 °C for 60 min, followed by 70 °C for 5 min97. qRT-PCR was performed using the StepOne System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with SinaSyber Blue HF-qPCR Mix (CinnaGen, Tehran, Iran). Primers for Bax, caspase-3, Bcl-2, and GAPDH are listed in Table 9. A 25 µL reaction included 12.5 µL master mix, 1 µL each primer (10 µM), 2 µL cDNA, and 8.5 µL water. Cycling conditions were: 95 °C for 10 min, 45 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. Expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, normalized to GAPDH49.

Fertilization index in vivo

Three males per group were housed with two untreated virgin females for 10 days until copulation was confirmed by vaginal plug or swab. Pregnancy and offspring were recorded on postnatal day 4. Indices were calculated as: female mating index (females mated/females × 100), male mating index (males mated/males × 100), pregnancy index (females pregnant/females mated × 100), and male fertility index (males impregnating females/males mated × 100)82.

Statistical analysis

The study data were examined using SPSS software (version 26.0, IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL, USA). The study used one-way ANOVA to identify significant differences between groups. Individual groups that differed significantly were determined using Tukey’s post hoc analysis. A p-value of less than 0.05 was found to be statistically significant.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- NPs:

-

Nanoparticles

- Cu:

-

Copper

- CuO NPs:

-

Copper oxide nanoparticles

- TM:

-

Total motility

- PM:

-

Progressive motility

- VCL:

-

Curvilinear velocity

- VSL:

-

Straight-line velocity

- VAP:

-

Average path velocity

- STR:

-

Straightness

- LIN:

-

Linearity

- ALH:

-

Amplitude of lateral head displacement

- BCF:

-

Beat-cross frequency

- PMF:

-

Plasma membrane functionality

- TAC:

-

Total antioxidant capacity

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- CAT:

-

Catalase

- GSH:

-

Reduced glutathione

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- AO:

-

Acridine orange

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- H&E:

-

Hematoxylin and eosin

References

Auer, J. A. & Stick, J. A. (eds) Reproductive system in equine surgery. Equine surgery. 3rd ed. USA: Saunders Elsevier pp. 1234–1256 (2006).

Hamed, M. A. et al. Evaluation of chemical castration using intra-testicular injection of zinc gluconate into the testis of the male Donkey versus surgical castration: antimullerian hormone as an endpoint marker. BMC Vet. Res. 19, 140 (2023).

Baqerkhani, M., Soleimanzadeh, A. & Mohammadi, R. Effects of intratesticular injection of hypertonic mannitol and saline on the quality of Donkey sperm, indicators of oxidative stress and testicular tissue pathology. BMC Vet. Res. 20, 99 (2024).

Singh, G., Kumar, A., Dutt, R., Arjun, V. & Jain, V. K. Chemical castration in animals: an update. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App Sci. 9, 2787–2807 (2020).

Shim, M., Bang, W. J., Oh, C. Y., Lee, Y. S. & Cho, J. S. Effectiveness of three different luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists in the chemical castration of patients with prostate cancer: Goserelin versus Triptorelin versus leuprolide. Investig Clin. Urol. 60, 244 (2019).

Inaba, T. et al. Reversible suppression of pituitary-testicular function by a sustained-release formulation of a GnRH agonist (leuprolide acetate) in dogs. Theriogenology 46, 671–677 (1996).

Hassan, A. & Fromsa, A. Review on chemical sterilization of male dogs. Int. J. Adv. Res. (Indore). 5, 758–770 (2017).

Hill, G. M., Neville, W. E. Jr, Richardson, K. L., Utley, P. R. & Stewart, R. L. Castration method and progesterone-estradiol implant effects on growth rate of suckling calves. J. Dairy. Sci. 68, 3059–3061 (1985).

Immegart, H. M. & Threlfall, W. R. Evaluation of intratesticular injection of glycerol for nonsurgical sterilization of dogs. Am. J. Vet. Res. 61, 544–549 (2000).

Kwak, B. K. & Lee, S. H. Intratesticular injection of hypertonic saline: non-invasive alternative method for animal castration model. Dev. Reprod. 17, 435 (2013).

Abou-Khalil, N. S., Ali, M. F., Ali, M. M. & Ibrahim, A. Surgical castration versus chemical castration in donkeys: response of stress, lipid profile and redox potential biomarkers. BMC Vet. Res. 16, 1–10 (2020).

Murty, T. S. & Sastry, G. A. Effect of cadmium chloride (CdCl2) injection on the histopathology of the testis and the prostate in dogs. I. Intratesticular procedure. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 16 (4), 456–459 (1978).

Jana, K. & Samanta, P. K. Evaluation of single intratesticular injection of calcium chloride for nonsurgical sterilization in adult albino rats. Contraception 73, 289–300 (2006).

Oberdorster, G. Toxicology of air born environment and occupational particles. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 5, 83–91 (2006).

Schipper, M. L. et al. A pilot toxicology study of single-walled carbon nanotubes in a small sample of mice. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 216–221 (2008).

Lin, P. et al. Computational and ultrastructural toxicology of a nanoparticle, quantum Dot 705, in mice. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 6264–6270 (2008).

Chou, C. C. et al. Single-walled carbon nanotubes can induce pulmonary injury in mouse model. Nano Lett. 8, 437–445 (2008).

Bhardwaj, J. K. & Rathee, V. Toxicological impact of nanoparticles on reproductive system: A review. Toxicol. Int. 30, 605–628 (2023).

Uauy, R., Olivares, M. & Gonzalez, M. Essentiality of copper in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 67, 952S–959S (1998).

Bertinato, J. & L’Abbé, M. R. Maintaining copper homeostasis: regulation of copper-trafficking proteins in response to copper deficiency or overload. J. Nutr. Biochem. 15, 316–322 (2004).

Dorsey, A. & Ingerman, L. Toxicological profile for copper. Atlanta, GA: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, pp: 130–250 (2004).

Gondwal, M. & Joshi nee Pant, G. Synthesis and catalytic and biological activities of silver and copper nanoparticles using Cassia occidentalis. Int J Biomater 6735426 (2018). (2018).

Sarkar, A., Das, J., Manna, P. & Sil, P. C. Nano-copper induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in kidney via both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways. Toxicology 290, 208–217 (2011).

Bhardwaj, J. K. & Panchal, H. Quercetin mediated Attenuation of cadmium-induced oxidative toxicity and apoptosis of spermatogenic cells in caprine testes in vitro. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 62, 374–384 (2021).

Dixit, V. P., Lohiya, N. K., Arya, M. & Agrawal, M. Chemical sterilization of male dogs after a single intra-testicular injection of danazol. Folia Biol. (Praha). 23, 305–310 (1975).

FORDYCE, G. et al. An evaluation of calf castration by intra-testicular injection of a lactic acid solution. Aust Vet. J. 66, 272–276 (1989).

Mohammed, A. & James, F. O. Chemical castration by a single bilateral intra-testicular injection of chlorhexidine gluconate and cetrimide in bucks. Sokoto J. Vet. Sci 11, (2013).

Canpolat, I., Gur, S., Gunay, C., Bulut, S. & Eroksuz, H. An evaluation of the outcome of bull castration by intra-testicular injection of ethanol and calcium chloride. Rev. Med. Vet. (Toulouse). 157, 420 (2006).

Maadi, M. A. et al. Chemical castration using an intratesticular injection of mannitol: A preliminary study in a rat model. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 45, 519–530 (2021).

Souza, M. R., Mazaro-Costa, R. & Rocha, T. L. Can nanomaterials induce reproductive toxicity in male mammals? A historical and critical review. Sci. Total Env. 769, 144354 (2021).

Zheng, X. et al. Prepubertal exposure to copper oxide nanoparticles induces Leydig cell injury with steroidogenesis disorders in mouse testes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 654, 62–72 (2023).

Yoshida, S. et al. Effect of nanoparticles on the male reproductive system of mice. Int. J. Androl. 32, 337–342 (2009).

Heinrich, A. & DeFalco, T. Essential roles of interstitial cells in testicular development and function. Andrology 8, 903–914 (2020).

Jassim, S. H. & Salman, T. A. The potential of green-synthesized copper oxide nanoparticles from coffee aqueous extract to inhibit testosterone hormones. Egypt. J. Chem. 65, 395–402 (2022).

Ramaswamy, S. & Weinbauer, G. F. Endocrine control of spermatogenesis: role of FSH and LH/testosterone. Spermatogenesis 4, e996025 (2014).

Farombi, E. O. et al. Quercetin protects against testicular toxicity induced by chronic administration of therapeutic dose of quinine sulfate in rats. J. Basic. Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 23, 39–44 (2012).

Lemasters, G. K. & Selevan, S. G. Toxic exposures and reproduction: a view of epidemiology and surveillance. Reproductive toxicology and infertility. Scialli AR, Zinaman MJ, eds. McGraw Hill 307–321 (1993).

Puja, I. K. et al. Preservation of semen from Kintamani Bali dogs by freezing method. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 6, 158 (2019).

Izanloo, H., Soleimanzadeh, A., N Bucak, M., Imani, M. & Zhandi, M. The effects of varying concentrations of glutathione and Trehalose in improving microscopic and oxidative stress parameters in Turkey semen during liquid storage at 5° C. Cryobiology 101, 12–19 (2021).

Ramazani, N. et al. Reducing oxidative stress by κ-carrageenan and C60HyFn: the post-thaw quality and antioxidant status of Azari water Buffalo bull semen. Cryobiology 111, 104–112 (2023).

Ramazani, N. et al. The influence of L-proline and fulvic acid on oxidative stress and semen quality of Buffalo bull semen following cryopreservation. Vet. Med. Sci. 9, 1791–1802 (2023).

Ruiz-Pesini, E., Díez‐Sánchez, C., López‐Pérez, M. J. & Enríquez, J. A. The role of the mitochondrion in sperm function: is there a place for oxidative phosphorylation or is this a purely glycolytic process? Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 77, 3–19 (2007).

Vassal, M., Rebelo, S. & de Pereira, M. Metal oxide nanoparticles: evidence of adverse effects on the male reproductive system. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 8061 (2021).

Garncarek, M., Dziewulska, K. & Kowalska-Góralska, M. The effect of copper and copper oxide nanoparticles on rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus Mykiss W.) spermatozoa motility after incubation with contaminants. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 19, 8486 (2022).

Kalirawana, T. C., Sharma, P. & Joshi, S. C. Reproductive toxicity of copper nanoparticles in male albino rats. Int. J. Pharma Res. Health Sci. 6, 2258–2263 (2018).

Robert, M. A., Jayaprakash, G., Pawshe, M., Tamilmani, T. & Sathiyabarathi, M. Collection and evaluation of canine semen-a review. Int. J. Sci. Environ. Technol. 5, 1586–1595 (2016).

Bennetts, L. E. & Aitken, R. J. A comparative study of oxidative DNA damage in mammalian spermatozoa. Mol. Reprod. Dev: Incorporating Gamete Res. 71, 77–87 (2005).

Soleimanzadeh, A., Mohammadnejad, L., Ahmadi, A. & Dvm, A. S. Ameliorative effect of allium sativum extract on busulfan-induced oxidative stress in mice sperm. Vet. Res. Forum. 9, 265–271 (2018).

Soleimanzadeh, A., Pourebrahim, M., Delirezh, N. & Kian, M. Ginger ameliorates reproductive toxicity of formaldehyde in male mice: evidences for Bcl-2 and Bax. J. Herb. Pharmacol. 7, 259–266 (2018).

Soleimanzadeh, A., Kian, M., Moradi, S. & Mahmoudi, S. Carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.) fruit hydro-alcoholic extract alleviates reproductive toxicity of lead in male mice: evidence on sperm parameters, sex hormones, oxidative stress biomarkers and expression of Nrf2 and iNOS. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 10, 35 (2020).

Talebi, A. R., Khorsandi, L. & Moridian, M. The effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles on mouse spermatogenesis. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 30, 1203–1209 (2013).

Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J. et al. Silver nanoparticles effects on epididymal sperm in rats. Toxicol. Lett. 214, 251–258 (2012).

Zini, A. et al. Anti-sperm antibodies are not associated with sperm DNA damage: a prospective study of infertile men. J. Reprod. Immunol. 85, 205–208 (2010).

Jungwirth, A. et al. EAU guidelines on male infertility. Eur. Urol. 7, 226–241 (2013).

Asghari, A., Akbari, G., Meghdadi, A. & Mortazavi, P. Protective effect of Metformin on testicular ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Acta Cir. Bras. 31, 411–416 (2016).

Hanagata, N. et al. Molecular responses of human lung epithelial cells to the toxicity of copper oxide nanoparticles inferred from whole genome expression analysis. ACS Nano. 5, 9326–9338 (2011).

Wang, Z. et al. CuO nanoparticle interaction with human epithelial cells: cellular uptake, location, export, and genotoxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 25, 1512–1521 (2012).

Jana, K. & Samanta, P. K. Sterilization of male stray dogs with a single intratesticular injection of calcium chloride: a dose-dependent study. Contraception 75, 390–400 (2007).

Bhardwaj, J. K., Siwach, A., Sachdeva, D. & Sachdeva, S. N. Revisiting cadmium-induced toxicity in the male reproductive system: an update. Arch. Toxicol. 98, 3619–3639 (2024).

Creasy, D. M. Pathogenesis of male reproductive toxicity. Toxicol. Pathol. 29, 64–76 (2001).

Creasy, D. et al. Proliferative and nonproliferative lesions of the rat and mouse male reproductive system. Toxicol. Pathol. 40, 40S–121S (2012).

Hild, S. A., Reel, J. R., Larner, J. M. & Blye, R. P. Disruption of spermatogenesis and Sertoli cell structure and function by the indenopyridine CDB-4022 in Rats1. Biol. Reprod. 65, 1771–1779 (2001).

Al-Musawi, M. M. S., Al-Shmgani, H. & Al-Bairuty, G. A. Histopathological and biochemical comparative study of copper oxide nanoparticles and copper sulphate toxicity in male albino mice reproductive system. Int J Biomater 4877637 (2022). (2022).

Rajabi, S., Shahbazi, F., Noori, A. & Karshenas, R. Investigation of the toxic effects of copper oxide nanoparticles on the structure of gonadal tissue in male. Experimental Anim. Biology. 7, 117–124 (2019).

Canpolat, I., Karabulut, E. & Eroksuz, Y. Chemical castration of adult and non-adult male dogs with sodium chloride solution. IOSR J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 9, 9–11 (2016).

Talebi, A. R., Sarcheshmeh, A. A., Khalili, M. A. & Tabibnejad, N. Effects of ethanol consumption on chromatin condensation and DNA integrity of epididymal spermatozoa in rat. Alcohol 45, 403–409 (2011).

Gosálvez, J., López-Fernández, C., Fernandez, J. L., Esteves, S. C. & Johnston, S. D. Unpacking the mysteries of sperm DNA fragmentation: ten frequently asked questions. J. Reprod. Biotechnol. Fertil. 4, 2058915815594454 (2015).

Neuber, E., Luetjens, C. M., Chan, A. W. S. & Schatten, G. P. Analysis of DNA fragmentation of in vitro cultured bovine blastocysts using TUNEL. Theriogenology 57, 2193–2202 (2002).

Iftikhar, M. et al. Perspectives of nanoparticles in male infertility: evidence for induced abnormalities in sperm production. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 18, 1758 (2021).

Kim, J. S. et al. Toxicity and tissue distribution of magnetic nanoparticles in mice. Toxicol. Sci. 89, 338–347 (2006).

Ozen, O. A., Kus, M. A., Kus, I., Alkoc, O. A. & Songur, A. Protective effects of melatonin against formaldehyde-induced oxidative damage and apoptosis in rat testes: an immunohistochemical and biochemical study. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 54, 169–176 (2008).

Kontos, K., Christodoulou, C., Scorilas, A. & M.-I. & Apoptosis-related BCL2-family members: key players in chemotherapy. Curr. Med. Chem:Anti-Cancer Agents. 14, 353–374 (2014).

Kamal, R. et al. Design, synthesis, and screening of triazolopyrimidine–pyrazole hybrids as potent apoptotic inducers. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim). 350, 1700137 (2017).

Kumar, P. et al. Multicomponent synthesis of some molecular hybrid containing thiazole pyrazole as apoptosis inducer. Drug Res. 68, 72–79 (2018).

Wiwanitkit, V., Sereemaspun, A. & Rojanathanes, R. Effect of gold nanoparticles on spermatozoa: the first world report. Fertil. Steril. 91, e7–e8 (2009).

Mehmood, A., Anwar, M. & Naqvi, S. M. S. Motility, acrosome integrity, membrane integrity and oocyte cleavage rate of sperm separated by swim-up or Percoll gradient method from frozen–thawed Buffalo semen. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 111, 141–148 (2009).

Lu, X. et al. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoTEMPO improves the post-thaw sperm quality. Cryobiology 80, 26–29 (2018).

Zhang, X. et al. Mito-Tempo alleviates Cryodamage by regulating intracellular oxidative metabolism in spermatozoa from asthenozoospermic patients. Cryobiology 91, 18–22 (2019).

Ahmad, M. et al. Histotoxicity induced by copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO-NPs) on developing mice (Mus musculus). Food Chem. Toxicol. 184, 114369 (2024).

de Lima, A. Fertility in male rats: disentangling adverse effects of arsenic compounds. Reprod. Toxicol. 78, 130–140 (2018).

Raabe, B. M., Artwohl, J. E., Purcell, J. E., Lovaglio, J. & Fortman, J. D. Effects of weekly blood collection in C57BL/6 mice. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 50, 680–685 (2011).

Sadeghirad, M., Soleimanzadeh, A., Shalizar-Jalali, A. & Behfar, M. Synergistic protective effects of 3, 4-dihydroxyphenylglycol and Hydroxytyrosol in male rats against induced heat stress-induced reproduction damage. Food Chem. Toxicol 114818 (2024).

Kashiwazaki, N. et al. Techniques for in vitro and in vivo fertilization in the rat. Rat Gen: Methods Protocols 311–322 (2010).

Anbara, H. et al. Repro-protective role of Royal jelly in phenylhydrazine-induced hemolytic anemia in male mice: Histopathological, embryological, and biochemical evidence. Environ. Toxicol. 37, 1124–1135 (2022).

Organization, W. H. WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen. in Who Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen 6th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 12–68 (2021).

Soleimanzadeh, A., Karvani, N., Davoodi, F., Molaie, R. & Raisi, A. Efficacy of silver-doped carbon Dots in chemical castration: a rat model study. Sci. Rep. 14, 24132 (2024).

Tejada, R. I., Mitchell, J. C., Norman, A., Marik, J. J. & Friedman, S. A test for the practical evaluation of male fertility by acridine orange (AO) fluorescence. Fertil. Steril. 42, 87–91 (1984).

Vendramini, V., Sasso-Cerri, E. & Miraglia, S. M. Amifostine reduces the seminiferous epithelium damage in doxorubicin-treated prepubertal rats without improving the fertility status. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 8, 1–13 (2010).

Russell, L. D., Ettlin, R. A., Hikim, A. P. S. & Clegg, E. D. Histological and Histopathological Evaluation of the Testis pp: 90–150 (Cache River, 1990).

Meistrich, M. L. & van Beek, M. Spermatogonial stem cells: assessing their survival and ability to produce differentiated cells. In: (eds Chapin, R. E. & Heindel, J. J.) Methods in Toxicology. Vol 3A: Male Reproductive Toxicology. San Diego, CA: 106–123 (1993).

Kheradmand, A., Dezfoulian, O. & Tarrahi, M. J. Ghrelin attenuates heat-induced degenerative effects in the rat testis. Regul. Pept. 167, 97–104 (2011).

Elias, H. & Hyde, D. M. An elementary introduction to stereology (quantitative microscopy). Am. J. Anat. 159, 411–446 (1980).

Cosentino, M. J., Nishida, M., Rabinowitz, R. & Cockett, A. T. K. Histopathology of prepubertal rat testes subjected to various durations of spermatic cord torsion. J. Androl. 7, 23–31 (1986).

Porter, K. L., Shetty, G. & Meistrich, M. L. Testicular edema is associated with spermatogonial arrest in irradiated rats. Endocrinology 147, 1297–1305 (2006).

Rezvanfar, M. A. et al. Protection of cyclophosphamide-induced toxicity in reproductive tract histology, sperm characteristics, and DNA damage by an herbal source; evidence for role of free-radical toxic stress. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 27, 901–910 (2008).

Akbar Gharehbagh, S., Tolouei Azar, J. & Razi, M. ROS and metabolomics-mediated autophagy in rat’s testicular tissue alter after exercise training; evidence for exercise intensity and outcomes. Life Sci. 277, 119473 (2021).

Wu, K. C. et al. Propofol induces DNA damage in mouse leukemic monocyte macrophage RAW264. 7 cells. Oncol. Rep. 30, 2304–2310 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Vice Chancellor of Research and Technology of the Urmia Branch, Islamic Azad University.

Funding

The Vice-Chancellor of Research and Technology of Urmia Branch, Islamic Azad University, supported this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Amin Rezazadeh: Investigation, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing., Alireza Najafpour: Methodology, Conceptualization, Writing - original draft. Ali Soleimanzadeh: Investigation, Methodology, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - original draft. Amir Amniattalab: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing - review & editing, Validation.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All protocols were approved by the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine’s Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments at Islamic Azad University (IR.IAU.URMIA.REC.1403.092). All animal experiments comply with the ARRIVE guidelines and follow the U.K. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986, and associated guidelines, EU Directive 2010/63/EU for animal experiments. Animal numbers were minimized per 3Rs principles (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement).

Declaration of generative AI in scientific writing

While preparing this work the author(s) used ChatGPT to make the text native. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the publication’s content.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rezazadeh, A., Najafpour, A., Soleimanzadeh, A. et al. Intratesticular copper oxide nanoparticles induce dose-dependent chemical castration in male mice. Sci Rep 15, 44927 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29371-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29371-x