Abstract

Skin hyperpigmentation represents a common aesthetic and dermatological concern, often resulting from excessive melanin synthesis and oxidative stress. Effective skin-lightening strategies target these processes by inhibiting tyrosinase activity, modulating melanogenic regulators, and enhancing antioxidant defenses. Ursolic acid, a natural triterpene abundant in apple peel, has shown potential as a safe and multifunctional skin-brightening molecule. In this study, an apple oil extract rich in ursolic acid (Annurca Apple Oleolite, AAO) was developed and standardized to 784.40 ± 7.58 µg/mL. The extract demonstrated significant tyrosinase inhibition and a marked reduction in melanin content in A375 melanoma cells, accompanied by downregulation of TYRP-1, TYRP-2, and MITF expression and modulation of oxidative stress markers. These molecular effects were confirmed in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial involving 42 subjects with hyperpigmented skin. Topical application of a formulation containing 2.5% AAO for 28 days significantly reduced UV and brown spot scores (–6.4% and − 4.1%, respectively; p < 0.001), decreased melanin index (–10.2%, p < 0.001), and improved skin brightness and tone uniformity (ITA° +12.4%; L* +3.1%; both p < 0.001) compared with placebo. Overall, the results highlight AAO as a promising natural agent for managing skin hyperpigmentation through multiple mechanisms, suggesting its potential utility in both cosmetic and dermatological formulations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Melanin is the most important biological pigment in humans, responsible for the pigmentation of skin, eyes, and hair1. It is produced by melanocytes in specific sub-cellular lysosome-like structures called melanosomes. Physiologically, melanin synthesis and production protect human skin from UV radiation; however, its abnormal synthesis could lead to several skin disorders, including hyperpigmentation, melasma, and age spots. Specifically, melanogenesis is a multi-step process involving melanin synthesis and transport, and the subsequent release of melanosomes. Chemically, the melanogenesis process begins with the oxidation of tyrosine to dopaquinone, which is catalyzed by the enzyme tyrosinase. Subsequently, the dopaquinone is converted into dopachrome by an auto-oxidation reaction2. The L-Dopa produced is itself a tyrosinase substrate and is oxidized again to dopaquinone, which undergoes further oxidative polymerization steps leading to the melanin formation3,4. Several molecular players are involved in regulating the melanogenesis process1. Specifically, UV-irradiation induces the synthesis of alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH) in melanocytes, which activates the melanocortin 1 receptor, leading to increased expression of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) through activation of the cyclic adenosine monophosphate pathway. The MITF produced is a key protein that controls the synthesis of several melanogenesis-regulating protein factors, including tyrosinase and tyrosinase-related proteins 1 and 2 (TYRP-1 and TYRP-2)5,6. Due to their pivotal role in melanin production, tyrosinase, TYRP-1, and TYRP-2 are generally recognized as the most important molecular targets for active agents with skin whitening and depigmenting potentials. Regarding oxidative balance, melanocytes are characterized by higher levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) than other cell types, such as fibroblasts7. This difference could be related to their higher rate of melanin production, which releases high levels of ROS as a collateral product, leading to an alteration in the redox potential of melanocytes. In this regard, several skin pigmentation disorders such as vitiligo have been reported to be positively related to an alteration of cellular defense enzymes with antioxidant activity, including Nrf2-related enzymes such as the catalytic and modulatory subunits of γ-glutamylcysteine ligase (GCLC and GCLM, respectively) as well as the enzyme heme oxygenase (HMOX-1)8,9,10. Given such a multifactorial nature of skin pigmentation disorders, there is great interest in identifying compounds with double potential: (i) antioxidant, and (ii) ability to modulate melanogenesis at different molecular levels.

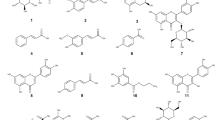

In this regard, increasing attention has been paid to the identification of natural and food-derived compounds as potential inhibitors of tyrosinase11. Among natural lipophilic compounds, ursolic acid (UA), a triterpene acid, has shown valuable in vitro tyrosinase inhibitory activity (IC50: 170.2 µM)12. This molecule reached a valuable concentration in several medical plant species13 and especially in apple peel (14.3 mg/g DW)14.

Interestingly, a comparative study conducted on both commercial and traditional Italian apple cultivars showed that Annurca apple (AA) was richer in UA (9.09 mg/g DW) and total terpenic content (14.19 mg/g DW) than other examined varieties14. Specifically, AA is the only apple cultivar native to southern Italy that has been registered by the European Council as a product with a Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) [Commission Regulation (EC) No.417/2006]. While the nutraceutical potential of the polyphenolic fraction of AA has been widely documented for its beneficial effects in the management of plasma cholesterol levels in humans15,16,17,18 and on the regulation of glycemia19, the potential health-promoting application of AA triterpenoid fraction is less well explored. In light of these considerations, in our recent study, we demonstrated that Annurca apple oil-based formulation (AAO) with standardized UA concentration (736 µg/mL) exerts valuable skin antiaging activity and favourable skin permeation features20,21.

Given these considerations, the main objectives of the present manuscript were to investigate the potential application of AAO as an active ingredient for the preparation of novel topical depigmenting formulations. Firstly, the in vitro inhibitory effect of AAO on tyrosinase was investigated. Next, we investigated the ability of AAO to reduce melanin production and transcriptionally modulate the expression of melanogenesis-regulating protein factors in human melanoma cell lines, as well as to modulate oxidative stress responses. Based on these promising in vitro results, AAO was tested in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, two parallel-arm clinical trials, conducted on 42 subjects with hyperpigmentation and diagnosed photo-damage, to investigate its effects on the main clinical skin pigmentation-related parameters, i.e., UV and brown spots, melanin index, and skin lightening markers (Individual Typology Angle, ITA° and luminescence, L*).

Results

Tyrosinase inhibition assay

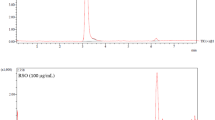

The tyrosinase enzyme plays a pivotal role in human skin pigmentation, thus its inhibition represents a potential treatment for hyperpigmentation-related disorders. To establish AAO as a whitening ingredient, the in vitro inhibition of tyrosinase activity was evaluated. As reported in Fig. 1, the AAO has shown a valuable capacity to inhibit tyrosinase activity in a concentration-dependent manner, with an IC50 of 286.42 µg/mL. To confirm that UA was the main molecule responsible for tyrosinase inhibition, the pure UA was tested, resulting in an IC50 of 26.82 µg/mL (Fig. 2B), which is approximately ten times more active than the AAO, as expected. Additionally, as a positive control, we used kojic acid (KA), a fungal metabolite with strong chelating properties for copper at the active site of the tyrosinase enzyme22. As expected, the KA IC50 (0.59 µg/mL) is the lowest calculated value in the present study (Fig. 2A), and it was in line with the tyrosinase inhibitory activity calculated by others, who reported KA IC50 values ranged from 1 to 10 µg/mL23.

AAO did not affect the proliferation of human melanoma cells

To better characterize the anti-melanogenic effects of AAO, we utilized a human melanoma cell line known to exhibit an altered melanogenesis process. First, we evaluated whether AAO exerts a cytotoxic effect by using A375 human melanoma cells. Cells were treated with increased concentrations of AAO (0, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 µg/mL) for 72 h, and cell viability was evaluated by performing an MTT assay. As shown in Fig. 3A, we found that the concentration of 100 µg/mL impaired A375 cell viability. Conversely, the pure UA reduced the proliferation of A375 melanoma cells already at the concentration of 10 µg/mL (Fig. 3B). Thus, we selected 30 µg/mL and 3 µg/mL as the concentrations for the next experiments for AAO and UA, respectively.

AAO reduced melanin production and the expression of melanogenesis-related genes

Next, we examined the effect of AAO and UA on melanin production in A375 human melanoma cells stimulated with α-MSH, known to trigger the melanin synthesis processes. As expected, the MSH treatment significantly increased the melanin production compared to A375 control cells. Importantly, as shown in Fig. 4A, we observed that both AAO (30 µg/mL) and UA (3 µg/mL) significantly reduced melanin production in MSH-stimulated A375 cells after 72 h of treatment. Moreover, AAO reduced the mRNA expression levels of tyrosinase (TYR) and its related proteins (TYRP-1 and TYRP-2), as well as the transcription factor MITF (Fig. 4B,C). In particular, MSH induced TYR expression ~ 1.5-fold vs. control, while AAO lowered it to 0.39-fold vs. MSH (61% reduction; 0.58-fold vs. control). UA reduced TYR to 0.71-fold vs. MSH (29% reduction; 1.05-fold vs. control). For TYRP-1, MSH increased expression 1.4-fold vs. control, whereas AAO suppressed it to 0.58-fold vs. MSH (42% reduction; 0.81-fold vs. control). UA decreased TYRP-1 to 0.71-fold vs. MSH (29% reduction; 1.0-fold vs. control). Similarly, TYRP-2 expression was induced 1.5-fold by MSH compared to control, while AAO reduced it to 0.40-fold vs. MSH (60% reduction; 0.59-fold vs. control). UA lowered TYRP-2 to 0.70-fold vs. MSH (30% reduction; 1.03-fold vs. control). Finally, MSH increased MITF expression 1.5-fold vs. control, whereas AAO markedly reduced it to 0.44-fold vs. MSH (56% reduction; 0.66-fold vs. control). UA decreased MITF expression to 0.60-fold vs. MSH (40% reduction; 0.90-fold vs. control). Taken together, these data demonstrated that AAO reduced melanin production by modulating the expression levels of the key players involved in melanogenesis.

(A) Melanin content in A375 melanoma cells upon 72 h of treatment with AAO (30 µg/mL) and UA (3 µg/mL) and in the presence of MSH. Expression of TYR, TYRP-1, TYRP-2 (B) and MITF (C) assessed with qPCR in A375 cells upon 6 h of treatment with AAO (30 µg/mL) and UA (3 µg/mL) and in the presence of MSH. Data were shown as mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and **** p < 0.0001 vs. MSH; °p < 0.05, °°p < 0.01 vs. CTR).

AAO modulation of ROS production

Melanogenesis and oxidative stress are intertwined in a feedback loop: while melanin production generates free radicals, the reactive species can further stimulate melanogenesis24. Therefore, we investigated the ability of AAO to modulate oxidative stress in A375 human melanoma cells by evaluating the production of ROS and the expression of the key antioxidant enzymes. First, we analyzed ROS production by using the 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescin (DCF) probe and inducing oxidative damage with Fenton’s reagent in order to increase ROS production. As shown in Fig. 5A,B, the preincubation with both AAO and UA significantly reduced ROS production, suggesting their potential antioxidant protective role. To corroborate these data, we analyzed the expression of three important antioxidant enzymes: GCLC, GCLM, and HMOX-1 in AAO- and UA-treated A375 cells and stimulated with Fenton’s reagent. Our results showed that treatment with AAO significantly increased the expression of all the enzymes tested, whereas UA induced an up-regulation of the HMOX-1 enzyme (Fig. 5C). In addition, we also evaluated the contribution of oxidative damage to the expression of the melanogenesis-related proteins MITF and TYR. As expected, the expression of both MITF and TYR was increased in oxidative stress conditions compared to A375 control cells. Interestingly, the preincubation with AAO (30 mg/mL) or UA (3 mg/mL) drastically reduced their expression, confirming their modulation also under strong oxidative imbalance (Fig. 5D). Finally, to address putative crosstalk between melanogenesis and oxidative stress, we also investigated ROS production in MSH-stimulated A375 cells. As shown in Fig. 5E,F, MSH increased ROS production, while both AAO and UA reduced the production of ROS. Collectively, these results demonstrated that both AAO and UA exert antioxidant effects by reducing ROS production and modulating the expression of antioxidant enzymes. Moreover, both the antioxidant effects and the modulation of melanogenesis of AAO could be interconnected, given the potential crosstalk between these processes.

(A) Representative example of flow cytometry analysis of DCF-DHA in A375 untreated (black histograms) and after AAO (30 µg/mL) and UA (3 µg/mL) treatment (red and orange histogram respectively) in the presence of Fenton’s reagent (green histogram) for 48 h and (B) quantification in terms of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). (C) Expression of GCLC, GCLM, HMOX and MITF and TYR (D) assessed by qPCR in A375 cells upon 6 h of treatment with AAO (30 µg/mL) and UA (3 µg/mL) and in the presence of Fenton’s reagent. (E) Representative example of flow cytometry analysis of DCF-DHA in A375 untreated (black histograms) and after AAO (30 µg/mL) and UA (3 µg/mL) treatment (red and orange histogram respectively) in the presence of MSH (blue histogram) for 48 h and (F) quantification in terms of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Data were shown as mean ± SEM of at least three independent experiments (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 vs. Fenton or MSH; °° p < 0.01, °°° p < 0.001 vs. CTR).

Clinical data

Demographic data

During the recruitment process, out of 48 participants enrolled, 6 subjects dropped out (3 were lost to follow-up and 3 subjects underwent aesthetic procedures), leaving a total of 42 females. The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The majority of participants were 45–55 years old (30 subjects, 71.4%). Overall, 66.7% of the participants had a Fitzpatrick skin type II, and 33.3% had a Fitzpatrick skin type III.

Effects of AAO-based topical formulation on pigmentation-related skin parameters

The key parameters used to evaluate AAO’s efficacy on photo-damage were the Individual Typology Angle (ITA°), L* luminance, and the melanin index (MI). ITA° classifies skin pigmentation based on colorimetry25, and is calculated using the formula:

Where L* represents luminance (ranging from 0 for black to 100 for white) and b* ranges from yellow (-b*) to blue (+ b*). Higher ITA° values indicate lighter skin and greater lightening from treatment. The average percentage changes in ITA° and L* at day 14 (D14) and day 28 (D28) are shown in Fig. 6A,B, while MI changes are depicted in Fig. 6C, whereas the exact mean changes (± SD) for L*, ITA°, MI, and statistical comparisons vs. placebo are provided in Table 1.

(A) L*, (B) ITA° and (C) melanin content percentage variation after treatment with AAO or placebo, respectively, at each follow-up session (D14 and D28). The baseline data served as the reference value for each analysis. Data were shown as mean ± SEM (n = 20). (** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001 vs. D0, $$$ p < 0.001 vs. placebo).

Results showed no significant differences between groups at baseline. However, L*, ITA°, and MI significantly improved in the AAO group during and after treatment (L*: 2% at D14 and 3% at D28, p < 0.01; ITA°: 10.4% at D14 and 12.4% at D28, p < 0.001; MI: −7.8% at D14 and − 10.2% at D28 p < 0.001). AAO also significantly reduced UV and brown spots compared to baseline and placebo by day 14 (Fig. 7). Neither AAO-treatment caused irritation or desquamation.

The UV and brown spots score percentage variation after treatment with AAO or placebo, respectively, at each follow-up session (D14 and D28). The baseline data served as the reference value for each analysis. Data were shown as mean ± SEM (n = 20). (* p < 0.05, vs. D0, $$ p < 0.01, $$$ p < 0.001 vs. placebo).

Discussion

The formation of skin spots has been mainly associated with an over-activation of the melanin synthesis, making the regulation of this biosynthetic pathway a major target of lightning agents. Moreover, melanogenesis and oxidative stress are closely interconnected in a feedback loop: melanin production generates free radicals, which in turn further stimulate melanogenesis. For this reason, the search for new active ingredients to address hyperpigmentation requires a multitarget strategy capable of acting on multiple pathways simultaneously. In line with this trend, in our previous work, we have optimized the obtainment of an oil extract from annurca apple (AAO) as a functional ingredient for topical formulation21. In particular, we have reported that the AAO prepared with a UA optimised concentration of 736 µg/mL is additionally a valuable antioxidant (evaluated in vitro using DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP assays, resulting in the antiradical potential of 16.63 ± 0.22, 5.90 ± 0.49, and 21.72 ± 0.68 µmol Trolox equivalent/g, respectively) and has a favorable skin permeation profile.

Thus, in order to investigate the potential depigmenting activity, we evaluated its inhibitory behavior on tyrosinase, and our results show that AAO has an IC50 of 286.42 µg/mL. The in vitro inhibitory activity is probably linked to the UA content, which is a noticeable tyrosinase inhibitor agent, with a calculated IC50 of 26.8 µg/mL (0.026 mM), a value in perfect agreement with results previously described by other22. In comparison with other well-known skin-lightening agents, the efficacy of AAO deserves contextualization. Hydroquinone, still regarded as the gold standard, shows strong tyrosinase inhibition and marked clinical results26 but its use is increasingly limited by safety and regulatory concerns27. Safer alternatives such as arbutin and niacinamide display higher IC₅₀ values and generally milder clinical outcomes28. Unlike classical depigmenting agents, AAO combines depigmenting efficacy with multifunctional benefits for the skin20 and is derived from apple peel, thereby embracing sustainability and upcycling principles.

In fact, to further investigate the depigmenting activity of AAO, beyond tyrosinase inhibition, we moved to investigate its effects on melanin production in A375 human melanoma cell line. The results showed that AAO (30 mg/mL) compared to UA (3 mg/mL) was able to cause a significant reduction in melanin production (p < 0.0001 vs. CTR) in A375 melanoma cells stimulated with α-MSH. A similar trend, in terms of melanin content, has already been observed in the murine melanoma cells B16F10 after treatment with UA (3–10 mg/mL), resulting in efficient inhibition of melanin production29. To further investigate the molecular mechanism of action involved, the effects of AAO on TYR, TYRP-1, TYRP-2, and MITF mRNA transcription were investigated. Our results indicate that AAO significantly reduces mRNA expression of all the melanogenic modulators studied. Furthermore, these results were also observed in the Fenton-stressed cell model, in which the induced oxidative stress increased the expression of TYR and MITF. These data confirm the AAO ability to downregulate the expression of melanogenic modulators in both basal and oxidative-stress conditions. Interestingly, the implication of UA or UA-containing extracts in the management of these melanogenic factors has not yet been described. Therefore, this work represents the first attempt to establish the effects of UA and UA-based products on the control of the melanogenesis process.

Given the complex and bivalent relationship between melanogenesis and cellular oxidative stress, in which increased melanin synthesis could generate high levels of reactive oxygen species in melanosomes and a subsequent increase in oxidative stress could further stimulate melanogenesis, coupled with the fact that melanin itself has played a central role in modulating oxidative homeostasis at the skin level22,29,our findings suggest that AAO exerts its inhibitory effect through a dual mechanism. On one hand, AAO directly downregulates transcriptional regulators of melanogenesis, such as TYR, TYRP-1, TYRP-2, and MITF. On the other hand, AAO modulates the redox status of melanocytes by reducing ROS levels and upregulating antioxidant defense enzymes such as GCLC, GCLM (p < 0.05), and especially HMOX-1 (3-fold increased vs. CTR, p < 0.001). This antioxidant response contributes to the suppression of MITF expression under oxidative stress, thereby indirectly reinforcing the transcriptional inhibition of melanogenesis. Our results could likely be related to the AAO valuable UA content, whose regulatory activity in transcriptional upregulation of HMOX-1 mRNA expression was previously reported in JB6 P + murine cells30. In addition, while no relevant modulatory effect on the expression of GCLC or GCLM has been attributed to UA, the observed upregulation of these enzymes could be probably related to a synergic activity of the polyphenolic AAO content31,32.

Lastly, the ability of AAO and UA to modulate mitochondrial activity, was also investigated, and we demonstrated that they reduced mitochondrial ROS generation, as demonstrated for other natural compounds such as resveratrol and quercetin33. Encouraged by the achieved promising in vitro results, a monocentric, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2-parallel-arm clinical trial was carried out on 42 subjects with hyperpigmentation and diagnosed photo-damage. The aim was to explore AAO-based topical formulation effects on the main clinical skin pigmentation-related parameters, i.e., UV spots, brown spots, and melanin index. Our results indicate that, after 28 days of treatment, a significant reduction of spot score for both UV (−6.4% vs. T0; p < 0.001) and brown spots (−4.1% vs. baseline; p < 0.001) was registered, accompanied by a valuable reduction of their melanin content (−10.2% vs. baseline; p < 0.001). Additionally, our results are consistent with those reported by the few pieces of evidence related to the beneficial effects of UA-based topical formulations. Finally, an improvement in the color complexion and skin brightness (ITA°: 12.4% vs. baseline; p < 0.001, and L*: 3.1% vs. T0, p < 0.001) was also registered. The relatively small sample size allowed us to interpret the results as preliminary evidence of clinical efficacy and safety. In conclusion, AAO emerges as a safe and sustainable ingredient that, beyond its tyrosinase inhibition, combines antioxidant and antiaging activities, making it a promising multitarget approach for hyperpigmentation.

Conclusion

The triterpenic fraction of AAO, primarily composed of ursolic acid (UA), demonstrated significant inhibition of tyrosinase activity in an in vitro model. In A375 melanoma cells, AAO down-regulated key melanogenesis modulators (TYR, TYRP-1, TYRP-2, MITF) at the transcriptional level, both in α-MSH and Fenton-stimulated models. Given the link between hyperpigmentation and oxidative stress, AAO antioxidant potential was also explored. Results showed AAO up-regulated antioxidant enzyme expression while reducing MITF and TYR levels under oxidative stress. These findings were supported by the clinical trial, further confirming AAO potential as a functional ingredient in depigmenting topical formulations.

Materials and methods

Reagents

All chemicals, reagents, and standards used were analytical or LC-MS grade reagents. The water was treated in a Milli-Q water purification system (Millipore, Bedford, Burlington, MA, USA) before use. Sunflower oil was purchased in a local market. Ursolic acid (purity ≥ 98.5% HPLC), phloridzin (purity ≥ 99% HPLC), kojic acid (purity ≥ 98.5% HPLC), L-tyrosine (purity ≥ 98% HPLC), tyrosinase from mushroom (activity ≥ 1000 U/mg), human melanoma cell lines A375, MTT, TRI-Reagent, and Nanodrop were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Milan, Italy). DMEM medium, heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, L-glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin, and HEPES buffer were purchased from Gibco (New York, NY, USA). The iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix for RT-qPCR was purchased from Bio-Rad (Milan, Italy). H2DCFDHA, MitoTracker Green and TMRM were purchased from Thermo Fisher Waltham (MA, USA).

Oleolite preparation

Annurca apple fruits (Malus pumila Miller cv Annurca) (about 100 g each) were collected in October 2023, Valle di Maddaloni (Caserta, Italy), when the fruits had just been harvested (green peel). The fruits were reddened for about 30 days following the typical treatment34. After this time, the apples were washed and sliced for freeze-drying. The oleolite preparation was performed according to the conditions optimized in our previously published article21 to achieve the maximum UA concentration of 784.40 ± 7.58 µg/mL. Specifically, the ratio of freeze-dried AA to sunflower oil was 1:4, and the mixture was stirred at 68.85 ◦C for 63 h. Then, the AAO was subjected to a specific extraction protocol for the isolation of its triterpenic fraction, according to our published protocols. The extraction was carried out with ethyl acetate, and the fractions were dried using a rotary evaporator. Once the solvents used were completely removed, the residues obtained were suspended in water, frozen at −80°, and freeze-dried (for 24 h, −69 °C at 0.096 mbar). The resulting powder was ground (IKA A11 analytical mill) to obtain a homogeneous powder representative of the triterpenic AAO composition21.

Tyrosinase inhibition assay

The tyrosinase inhibition assay was performed according to the modified dopachrome method35. Practically, the inhibition of the enzyme was assessed by monitoring the enzymatic metabolization of L-tyrosine substrate according to the HPLC method described. According to the used protocol, 70 µL of different concentrations of the samples were added to a 96-well microplate. Then, 100 µL of 1 mM L-tyrosine and 30 µL of mushroom tyrosinase (500 U/mL), both of them prepared in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 6.5, were added, mixed well, and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. After this incubation time, the enzymatic reaction was stopped by the addition to each sample of 100 µL of methanol. The analyzed standards and the extracts were dissolved in 100%v/v DMSO and diluted with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.5, to obtain a final concentration of 1% v/v DMSO in the enzymatic mixture. Kojic acid was used as a positive control, while the control was performed by replacing the sample with an equal volume of buffer. In the HPLC assay, enzymatic activity was evaluated as a decrease in the chromatographic L-tyrosine peak area for the tyrosinase reaction of the enzyme. The L-tyrosine peak area was normalized to the 1 mM L-tyrosine peak area. The inhibitory effect was expressed as the concentration required to inhibit L-tyrosine metabolism by 50% (IC50)36.

HPLC-FLD method for L-tyrosine analysis IC50

A Jasco Extrema LC-4000 HPLC system (Jasco Inc., Easton, MD, USA), coupled with an autosampler, a binary solvent pump, and a fluorescence detector (FLD), was used for the analysis. The chromatographic analysis was performed according to37, with slight modifications. Elution was performed on a Luna HILIC column (150 mm x 3.0, 5 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The mobile phases were an ammonium acetate buffer, 5 mM, containing 0.1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B). The elution gradient was performed under the following conditions: 0–5 min, isocratic on 90% phase B; 5–17 min, linear gradient from 90 to 70% B; 17–27 min, isocratic with 90% B; 24–29 min, isocratic with 60% B for column reconditioning. The separation parameters were as follows: column temperature was set at 35 °C, injection volume was 20 µl, and flow rate was set at 1 mL/min. The quantification of tyrosine was performed with an excitation wavelength of 272 nm and an emission wavelength of 312 nm.

Cell culture

The human melanoma cells lines A375 were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin and 10 mM HEPES buffer and grown at 37 °C in a humidified incubator under 5% CO2.

MTT assay

A375 cells (103 cells/well) were plated on a 96-well plate and treated with AAO and UA (0.01 to 100 µg/mL) for 72 h. Next, 25 µL of MTT was added and incubated for 3 hr at 37 °C. Thereafter, the dark blue crystals developed, were solubilized with DMSO and the absorbance was measured at 545 nm using a Multiskan GO microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA).

Measurement of melanin content

A375 cells (3 × 105/well) were plated in a 6-well plate and treated with AAO (30 µg/mL) and UA (3 µg/mL). After 72 h, cells were lysed in NaOH 1 N and incubated for 90 min at 37 °C, then centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm. The optical density (OD) of supernatant was measured at 450 nm using a Multiskan GO microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

RNA extraction and qPCR analysis

A375 melanoma cells were treated with AAO and UA (30 µg/mL and 3 µg/mL, respectively) for 6 h. Thereafter, total RNA was extracted by using TRI-Reagent, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After quantification with Nanodrop, 1 µg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed by using iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix for RT-qPCR. qPCR analysis was performed with the Bio-Rad CFX384 real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Milan, Italy) by using the following primers:

TYR (Gene ID: 7299).

5’- GCACAGATGAGTACATGGGAGG − 3’; 5’- CTGATGGCTGTTGTACTCCTCC − 3’

TYRP-1 (Gene ID: 7306).

5’- TCTCAATGGCGAGTGGTCTGTG-3’; 5’- CCTGTGGTTCAGGAAGAC-GTTG-3’

TYRP-2 (Gene ID: 1638).

5’- CTCAGACCAACTTGGCTACAGC-3’; 5’- CAACCAAAGCCACCAG-TGTTCC-3’

MITF (Gene ID: 4286).

5’- GGCTTGATGGATCCTGCTTTGC-3’; 5’- GAAGGTTGGCTGGACAG-GAGTT-3’

GCLC (Gene ID: 2729).

5’-GTTGGGGTTTGTCCTCTCCC-3’; 5’-GGGGTGACGAGGTGGAGTA-3’

GCLM (Gene ID: 2730).

5’-AGGAGCTTCGGGACTGTATCC-3’; 5’-GGGACATGGTGCATTCCAAAA-3’

HMOX-1(Gene ID: 3162).

5’-GCCGTGTAGATATGGTACAAGGA-3’; 5’-AAGCCGAGAATGCTGAGTTCA-3’

The 2ΔDCt formula was used for the analysis, and ribosomal protein S16 (RPS16) was used as a housekeeping gene38.

RPS16 (Gene ID: 6217).

5’- TCGGACGCAAGAAGACAGC-3’; 5’- AGCAGCTTGTACTGTAGCGTG-3’

Flow cytometry analysis

A375 were treated for 48 h with AAO and UA (30 µg/mL and 3 µg/mL, respectively). Thereafter, ROS production was evaluated by using the H2DCFDHA probe. Likewise, mitochondrial mass and membrane potential were evaluated by using Mito-Tracker Green and TMRM probes as previously described. For all flow cytometry analyses, gating was performed using FSC/SSC parameters to exclude debris and doublets, and only viable cells were included in the final analysis. Samples were acquired on a BriCyte E6 flow cytometer (Mindray Medical Italy S.r.l., Milan, Italy), and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar V.10; Carrboro, NC, USA).

Clinical trial

The study was a 4-week, monocentric, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial assessing the safety and efficacy of an AAO-based topical formulation versus placebo in adults with moderate-to-severe hyperpigmentation. Conducted from February 2022 to December 2022 at the RD Cosmetics Lab, University of Naples Federico II, it adhered to UNI EN ISO 9001 standards for efficacy studies. The trial included a 15-day screening period, a 7-day washout, and a 4-week treatment phase. The study protocol (Unique Protocol ID: EAAO22G01) was revised by the Institutional Review Board of the Pharmacy Department and recorded on clinicaltrials.gov on 25th June 2025 (ID: NCT07040345). The study was carried out according to ICH GCP, the Declaration of Helsinki and the SCCS Notes of Guidance for the Testing of Cosmetic Ingredients and their Safety Evaluation (12th revision). Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study followed CONSORT guidelines. Furtermore, participants whose identifiable images are used provided written consent for publication. The study flow is depicted in Fig. 8.

Study population and randomization

Eligible participants were women aged 40 to 65 with diagnosed photodamage and hyperpigmentation. Full eligibility criteria are detailed in the Supporting Information. Exclusion criteria included the use of treatments for hyperpigmentation or topical retinoids and allergies to the formulation ingredients. Participants were enrolled at their second laboratory visit, sequentially numbered, and randomized in blocks of 20 at a 1:1 ratio to receive either the active treatment (oil-in-water emulsion with 2.5%w/w AAO) or a placebo. The placebo formulation was identical to the active formulation in vehicle composition, appearance, and packaging, but it did not contain AAO. Blinding was maintained for both participants and observers.

Treatment

Participants applied 2 fingertip units of the allocated test product, whose composition is reported in Table 2. In particular, Group A received the active treatment with 2.5% AAO, whereas Group B received the placebo. The lab’s technicians instructed the volunteers to apply the assigned product twice daily, at least 12 h apart, for 28 days. Training on product application was provided, with the first application supervised. Baseline measurements, including independent instrumental analysis and photographs, were conducted at the initial visit. Participants were reviewed at days 14 and 28, with pigmentation changes assessed using the melanin index (Mexameter MX 18) and skin luminance measured through L* and ITA° values (Skin-Colorimeter CL 400). Brown and UV spots resulting from photodamage were analyzed using VISIA 7th with RBX analysis39. This is a high-resolution digital skin imaging system that combines multispectral photography with RBX® (Red/Brown Subsurface Analysis) technology to objectively quantify pigmentation features such as brown spots, UV spots, and overall skin tone heterogeneity. Skin acceptability was previously tested with an occlusive patch test.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism software version 9 (San Diego, CA, USA) was used for statistical analysis; t-test and ANOVA tests were used for comparison of two groups or multiple groups, respectively. The data were shown as mean percentage variation (%) ± SEM. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and was labelled with *; p-values < 0.01, 0.001, or 0.0001 were labelled with **, ***, or ****, respectively.

Sample size and power

This study was planned as an exploratory, proof-of-concept randomized trial. A formal a priori power calculation was not feasible due to the absence of prior clinical data on AAO. With the enrolled sample (20 active, 22 placebo), the trial provides ~ 72% power to detect large effects (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.8), ~ 89% power for very large effects (d ≈ 1.0), but only ~ 35% power for medium effects (d ≈ 0.5). The study was therefore not powered to detect small or moderate changes in ITA°, L*, or MI, but instead intended to generate effect size and variance estimates for planning future adequately powered studies.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size, which did not allow sufficient power to detect small or moderate differences in UV and brown spots, ITA°, L*, or MI. Consequently, the results should be interpreted as preliminary evidence of efficacy and safety.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. Raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

Annurca apple

- AAO:

-

Annurca apple oil

- CREB:

-

cAMP response element binding protein

- DCF:

-

2’,7’-dichlorofluorescin

- DMEM:

-

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- FLD:

-

Fluorescence detector

- GCLC:

-

γ-glutamylcysteine ligase

- HMOX-1:

-

Enzyme heme oxygenase

- ITA:

-

Individual typology angle

- KA:

-

Kojic acid

- MI:

-

Melanin index

- MITF:

-

Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor

- OD:

-

Optical density

- PGI:

-

Protected geographical indication

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- TYR:

-

Tyrosinase

- TYRP:

-

Tyrosinase-related protein

- UA:

-

Ursolic acid

- α-MSH:

-

Alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone

References

D’Mello, S. A. N., Finlay, G. J. & Baguley, B. C. Askarian-Amiri, M. E. Signaling pathways in melanogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, 1–18 (2016).

Du, D. et al. Real-time fluorometric monitoring of monophenolase activity using a matrix-matched calibration curve. Analyt. Bioanalyt. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-020 (2021).

Guo, N. et al. Continuous fluorometric method for determining the monophenolase activity of tyrosinase on L-Tyrosine, through quenching L-DOPA fluorescence by Borate. Anal. Chem. 92, 5780–5786 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. Synchronous fluorometric method for continuous assay of monophenolase activity. Spectrochim Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2021.119486 (2021).

Nguyen, N. T. & Fisher, D. E. MITF and UV responses in skin: from pigmentation to addiction. Pigment Cell. Melanoma Res. 32, 224–236 (2019).

Park, H. J. et al. Ursolic acid inhibits pigmentation by increasing melanosomal autophagy in B16F1 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 531, 209–214 (2020).

Jenkins, N. C. & Grossman, D. Role of melanin in melanocyte dysregulation of reactive oxygen species. Biomed. Res. Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/908797 (2013).

Qiu, L., Song, Z. & Setaluri, V. Oxidative stress and vitiligo: the Nrf2-ARE signaling connection. J. Invest. Dermatology. 134, 2074–2076 (2014).

Xuan, Y., Yang, Y., Xiang, L. & Zhang, C. The Role of Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Vitiligo: A Culprit for Melanocyte Death. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8498472 (2022).

Chang, W. L. & Ko, C. H. The role of oxidative stress in vitiligo: an update on its pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Cells 12, 1–17 (2023).

Di Lorenzo, R. et al. Phenylalanine butyramide: A butyrate derivative as a novel inhibitor of tyrosinase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 7310 (2024).

Bayrakçeken Güven, Z. et al. Food plant with antioxidant, tyrosinase inhibitory and antimelanoma activity: Prunus Mahaleb L. Food Biosci. 48, 101804 (2022).

López-Hortas, L., Pérez-Larrán, P., González-Muñoz, M. J., Falqué, E. & Domínguez, H. Recent developments on the extraction and application of ursolic acid. A review. Food Res. Int. 103, 130–149 (2018).

Nkuimi Wandjou, J. G. et al. Comprehensive characterization of phytochemicals and biological activities of the Italian ancient Apple ‘Mela Rosa dei monti sibillini’. Food Res. Int. 137, 109422 (2020).

Tenore, G. C. et al. Effects of Annurca Apple polyphenols on lipid metabolism in HepG2 cell lines: A source of nutraceuticals potentially indicated for the metabolic syndrome. Food Res. Int. 63, 252–257 (2014).

Tenore, G. C. et al. A healthy balance of plasma cholesterol by a novel Annurca Apple-Based nutraceutical formulation: results of a randomized trial. J. Med. Food. 20, 288–300 (2017).

Riccio, G. et al. WNT inhibitory activity of malus pumila miller cv annurca and malus domestica cv limoncella apple extracts on human colon-rectal cells carrying familial adenomatous polyposis mutations. Nutrients https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9111262 (2017).

Tenore, G. C. et al. A nutraceutical formulation based on Annurca Apple polyphenolic extract is effective on intestinal cholesterol absorption: A randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover study. PharmaNutrition 6, 85–94 (2018).

Maisto, M. et al. Optimization of Phlorizin extraction from Annurca Apple tree leaves using response surface methodology. Antioxidants 11, 1–15 (2022).

Di Lorenzo, R. et al. Annurca Apple oleolite as functional ingredient for the formulation of cosmetics with Skin-Antiaging activity. Int. J. Molecural Sci. 25, 1677 (2024).

Maisto, M. et al. Optimization of ursolic acid extraction in oil from annurca apple to obtain oleolytes with potential cosmeceutical application. Antioxidants 12, 224 (2023).

Nile, S. H., Nile, A., Liu, J., Kim, D. H. & Kai, G. Exploitation of Apple pomace towards extraction of triterpenic acids, antioxidant potential, cytotoxic effects, and Inhibition of clinically important enzymes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 131, 110563 (2019).

Neeley, E. et al. Variations in IC50 values with purity of mushroom tyrosinase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 10, 3811–3823 (2009).

Kaminski, K., Kazimierczak, U. & Kolenda, T. Oxidative stress in melanogenesis and melanoma development. Wspolczesna Onkologia. 26, 1–7 (2022).

Krutmann, J. et al. Photoprotection for people with skin of colour: needs and strategies. Br. J. Dermatol. 188, 168–175 (2023).

Zolghadri, S. et al. A comprehensive review on tyrosinase inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 34, 279–309 (2019).

Shivaram, K., Edwards, K. & Mohammad, T. F. An update on the safety of hydroquinone. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 316, 3–5 (2024).

Mann, T. et al. Inhibition of human tyrosinase requires molecular motifs distinctively different from mushroom tyrosinase. J. Invest. Dermatology. 138, 1601–1608 (2018).

Zhang, L. et al. Synchronous fluorometric method for continuous assay of monophenolase activity. Spectrochim Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 252, 119486 (2021).

Jin, K. S., Oh, Y. N., Hyun, S. K., Kwon, H. J. & Kim, B. W. Betulinic acid isolated from vitis amurensis root inhibits 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine induced melanogenesis via the regulation of MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways in B16F10 cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 68, 38–43 (2014).

Kachadourian, R. et al. A synthetic chalcone as a potent inducer of glutathione biosynthesis. J. Med. Chem. 55, 1382–1388 (2012).

Yang, Y. C. et al. Induction of glutathione synthesis and Heme Oxygenase 1 by the flavonoids Butein and Phloretin is mediated through the ERK/Nrf2 pathway and protects against oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol. Med. 51, 2073–2081 (2011).

Gibellini, L. et al. Natural Compounds Modulating Mitochondrial Functions. Evid. based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015 (2015).

Lo Scalzo, R., Testoni, A. & Genna, A. Annurca’ Apple fruit, a Southern Italy Apple cultivar: textural properties and aroma composition. Food Chem. 73, 333–343 (2001).

Kolakul, P. & Sripanidkulchai, B. Phytochemicals and anti-aging potentials of the extracts from lagerstroemia speciosa and lagerstroemia floribunda. Ind. Crops Prod. 109, 707–716 (2017).

Schiano, E. et al. Thinned Nectarines, an Agro-Food waste with antidiabetic potential: HPLC-HESI-MS/MS phenolic characterization and in vitro evaluation of their beneficial activities. Foods 11, 1010 (2022).

Pan, Y., Li, J., Li, X., Chen, J. & Bai, G. Determination of free amino acids in isatidis radix by HILIC-UPLC-MS/MS. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 35, 197–203 (2014).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-∆∆CT method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

Zawodny, P., Stój, E., Kulig, P., Skonieczna-żydecka, K. & Sieńko, J. VISIA skin analysis system as a tool to evaluate the reduction of pigmented skin and vascular lesions using the 532 Nm laser. Clin. Cosmet. Investig Dermatol. 15, 2187–2195 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Maria Maisto (M.M.), Giuseppe Ercolano (G.E.), and Ritamaria Di Lorenzo (R.D.L.); Data Curation: Ritamaria Di Lorenzo (R.D.L.), Maria Maisto (M.M.), and Giuseppe Ercolano (G.E.); Formal Analysis: Lucia Ricci (L.R.), Vincenzo Piccolo (V.P.), Daniela Claudia Maresca (C.M.), Benedetta Romano (B.R.), and Adua Marzocchi (A.M.); Investigation: Ritamaria Di Lorenzo (R.D.L.), Lucia Ricci (L.R.), Vincenzo Piccolo (V.P.), Daniela Claudia Maresca (C.M.), Benedetta Romano (B.R.), and Adua Marzocchi (A.M.); Methodology: Maria Maisto (M.M.), Giuseppe Ercolano (G.E.), and Ritamaria Di Lorenzo (R.D.L.); Resources: Sonia Laneri (S.L.), Angela Ianaro (A.I.), and Giuseppe Ercolano (G.E.); Supervision: Ritamaria Di Lorenzo (R.D.L.), Maria Maisto (M.M.), Giuseppe Ercolano (G.E.), Sonia Laneri (S.L.), and Angela Ianaro (A.I.); Writing—Original Draft Preparation: Ritamaria Di Lorenzo (R.D.L.), Maria Maisto (M.M.), and Giuseppe Ercolano (G.E.); Writing—Review & Editing: Maria Maisto (M.M.), Giuseppe Ercolano (G.E.), and Ritamaria Di Lorenzo (R.D.L.).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maisto, M., Piccolo, V., Marzocchi, A. et al. Apple oil as a source of ursolic acid for the treatment of hyperpigmentary disorders with molecular and clinical evaluation. Sci Rep 16, 55 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29398-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29398-0