Abstract

The persistent challenge of air leakage in smart factories continues to impose significant costs and operational inefficiencies. Conventional solutions, such as infrared detectors, suffer from drawbacks, demanding additional manpower for detection and incurring monetary losses during equipment downtime. Addressing the urgent need for early air leakage detection in manufacturing plants amid the ongoing digital transformation, this paper introduces an end-to-end framework that jointly handles class imbalance and provides uncertainty-aware predictions. At its core, we propose a novel unsupervised-enhanced data sampling method (UEDSM) to preserve data structure while alleviating imbalance, integrated with a dropout-enabled neural network (ALDNet) that applies Monte Carlo Dropout for robust inference. The effectiveness of our method is validated through a comprehensive series of experiments, incorporating real-time physical monitoring of two air compressors within a manufacturing plant. Beyond minimizing resource wastage and human intervention, our solution achieves over 95% accuracy and an F1-score above 80%, enabling reliable leakage detection several minutes in advance. These results highlight the practical viability of our approach for deployment in edge environments, contributing to improved efficiency, reduced resource wastage, and enhanced resilience in smart manufacturing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The smart factory seamlessly orchestrates the integrated management of diverse energy sources, aiming to optimize operational efficiency throughout the manufacturing process1,2,3,4. Notably, compressed air, a central component in the manufacturing process, serves as the control mechanism for a multitude of equipment across various sites5. This essential element, periodically supplied by a dedicated provider and conveyed through pipelines to end-users, faces potential challenges, including leaks originating from cracks or gaps within the intricate network of pipes6,7. In addition, the delicate equilibrium between air demand and supply occasionally falters, compelling pneumatic machines to involuntarily release air into the atmosphere8. These instances of air leakage can significantly impact the operational efficiency of the smart factory, posing a threat to the reliability of the energy supply system. Moreover, the substantial financial repercussions, equating to a 20% loss in the factory, underscore the pressing need for effective solutions. Given the absence of an established technique for solving air leakage, both industry and academia are actively involved in diverse initiatives aimed at addressing these pervasive challenges9,10.

Numerous conventional methods currently exist to detect air leakage in machines, encompassing manual inspections with hardware devices, such as the use of infrared cameras to identify leaks by temporarily shutting down other devices, as well as real-time monitoring techniques that analyze the ratio of air intake to discharge from the machine11,12. But, these approaches pose significant limitations, demanding a substantial investment of time and financial resources for effective machine monitoring. Furthermore, operators must halt machine operations to compare normal and abnormal sections, introducing challenges that impact the production schedule in the factory. While monitoring the ratio of inhaled and discharged air, along with a stop-the-machine scheme, can avert further issues after an air leakage, its capacity to alleviate pre-existing financial losses is limited. Thereby, our focus is on an advanced abnormal situation detection technique that enables the pre-detection of air leakage within a pneumatic machine. This is achieved through the comprehensive analysis of data collected from strategically integrated sensors within the infrastructure of a smart factory13,14.

In recent years, the increasing reliance on deep learning to detect abnormal situations across diverse fields attests to its proficiency in uncovering high-order correlations within complex multivariate time series data, often characterized by substantial volume and dimensionality15,16,17. Despite this progress, early detection of compressed-air leakage in smart manufacturing remains underexplored, particularly when available datasets are highly imbalanced and predictions must be reliable for deployment in safety-critical environments. To address these challenges, we investigate a framework that couples an imbalance-aware sampling strategy with an uncertainty-aware neural model, and validate its effectiveness using real-world compressor data collected in a smart factory setting.

Contributions of this paper

In this paper, we present an end-to-end deep learning framework for early detection of air leakage in IoT-connected compressors. The framework is designed to mitigate class imbalance and to provide uncertainty-aware predictions suitable for deployment in industrial edge environments. The main contributions are summarized as follows:

-

We propose an unsupervised-enhanced data sampling method (UEDSM) that integrates principal component analysis, k-means clustering, and cluster similarity scoring to eliminate overlapping majority samples prior to SMOTE oversampling.

-

We propose ALDNet, a dropout-enabled network that applies Monte Carlo Dropout at inference to capture epistemic uncertainty. While MC Dropout is well established, its integration with UEDSM in a unified pipeline delivers robust, reliable early-warning capability for industrial anomaly detection.

-

We formalize a domain-specific labeling strategy that defines leakage events from actuator dynamics within a predictive horizon, and apply correlation-aware feature filtering to mitigate multicollinearity in high-dimensional sensor data.

-

Extensive performance evaluation validates the superiority of the proposed scheme in terms of accuracy and F1-score, utilizing real-time physical monitoring of air compressors within a manufacturing plant.

Related work

The substantial energy loss attributed to air leakage in industry poses a critical challenge, given the indispensable role of compressed air in transmitting energy and operating various machines and equipment18. Operating under high pressure and system stability, compressed air stands as a vital resource extensively employed in automation and control systems within factories. Therefore, ensuring the integrity of compressed air systems is imperative for bolstering productivity and curtailing energy consumption. Unfortunately, the susceptibility of compressed air to leakage presents a considerable challenge, resulting in monetary losses and diminished operational efficiency19. This issue has evolved into a pressing concern in the business landscape, demanding urgent attention from the industry.

To tackle this challenge, researchers have recently delved into the detection of air leakage, leveraging diverse data and artificial neural network models20,21,22. For instance, Yang et al. proposed a method to predict the differential pressure value between chambers for the early detection of air leakage20. Employing a radial basis function neural network and collected air pressure data, the authors demonstrated the feasibility of predicting differential pressure values. However, this approach has limitations, requiring additional infrastructure and an accurate prediction scheme for preemptive air leakage determination. In another study, Cheng et al. introduced a fault detection and diagnosis method using multi-scale convolutional neural networks, showcasing advanced performance in detecting air leakage across various environments21. The authors presented that the diagnostic capability is enhanced by robust discriminative multiscale features and minimized classification information loss through end-to-end learning. In contrast, Quan et al. employed the particle swarm optimization algorithm, achieving highly accurate air leakage detection22. While these conventional studies have contributed novel analyses of various data to construct models related to air leakage detection, they often fall short in determining which data is genuinely relevant to air leakage. Additionally, these studies frequently lack a comparison between the proposed methods and conventional approaches.

In addition, extensive research has been dedicated to the identification of air leakage in compressors and analogous machinery23,24,25,26. In one study, Santolamazza et al. selected energy consumption as an indicator highly relevant to the normal operation of pneumatic machines23. They employed an artificial neural network model to assess abnormal situations, demonstrating the network’s ability to accurately characterize the system’s energy behavior. The results indicated that, when used in conjunction with a control chart, the artificial neural network enables the detection of anomalies in high performance. Furthermore, Salmanov et al. proposed a data-driven method for bleed valve system failure prediction in industrial engines24, Lee et al. introduced a density-based clustering method with logistic regression classifier to anticipate the severity of air leakages in braking pipes25. Lastly, Kim et al. attempted to detect abnormal situations using time series data through the anomaly-score-moving-average technique, grounded in statistical techniques26.

Beyond these domain-specific studies, the broader machine learning community has investigated uncertainty-aware sampling and deep active learning strategies to address skewed data distributions. For instance, Nuggehalli et al. proposed DIRECT, which employs uncertainty-based thresholds to select informative samples under imbalance and label noise conditions27. Next, Jin et al. introduced balanced active learning to improve image classification in imbalanced settings28, while Zhang et al. developed GALAXY, a graph-based active learning method designed for extreme class imbalance29. From a learning-theoretic perspective, Khan et al. demonstrated that Bayesian uncertainty can guide decision margins for rare classes30, and more recent work by Baltaci et al. suggested class-level predictive uncertainty as a measure to mitigate imbalance across datasets31. While these approaches offer valuable insights, they typically operate in iterative label acquisition settings and focus on benchmark datasets, making them less applicable to industrial telemetry where labeling is fixed and costly. Moreover, few works attempt to jointly combine class-imbalance mitigation and predictive uncertainty in a unified framework for real-world time series.

In recent decades, despite advancements in air compressor leakage detection, there is still a distinguished absence of the latest deep learning techniques, systematic discussions on selecting key factors linked to air leakage indicators, comprehensive model comparisons, and effective strategies for handling imbalanced industrial data. Our approach addresses these gaps through a unified framework that integrates imbalance mitigation with uncertainty-aware inference, thereby enabling robust and reliable early detection of air leakage in real-world manufacturing environments.

Results and discussion

In this section, the performance of UEDSM with ALDNet is comprehensively evaluated through experiments. The section begins by introducing the experimental settings, providing details on the dataset description, performance metrics, and comparison methods. Subsequently, the corresponding experimental results are thoroughly analyzed. All experiments are implemented using Python 3.6.13 with Tensorflow 2.6.2 on a server equipped with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-9700K CPU @ 3.60 GHz, 65.0 GB RAM, and NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1660 SUPER with CUDA 11.2.

Dataset description

To conduct a comprehensive evaluation, we utilized IoT sensor data gathered from real-time physical monitoring of two air compressors in a manufacturing plant located in South Korea, as shown partially in Fig. 1. These data, recorded and stored in the cloud every minute, initially comprised twenty-nine features. However, after data preprocessing, twelve features were retained for training the classification model. The training dataset covers the periods from April 15, 2023, to April 25, 2023, and May 01, 2023, to May 15, 2023, representing operational periods of the air compressors. For testing, data from June 14 to June 31, July 01 to July 15, and August 03 to August 21 were used. Table 1 presents the class ratios for each air compressor.

The sensor data were provided by the collaborating company, where standard calibration procedures had been performed in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. This ensured that the recorded pressure and flow values were consistent and reliable for analysis. Although the plant environment naturally introduced background noise, the collected time series exhibited stable patterns, and the proposed framework maintained consistent performance across multiple datasets, demonstrating robustness to such disturbances. For labeling, leakage events were defined according to the actuator dynamics expressed in Eq. (6). This rule ensured reproducibility and consistency in the ground-truth annotations used for training and evaluation.

Performance metrics

We assess the performance of the proposed framework and compare it with relevant baselines using two key metrics: accuracy and F1-score. These metrics are commonly used to evaluate classification models and are defined as

and

where TP, TN, FP, and FN represent the number of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. Higher values for both metrics indicate superior classification performance. Given the prevalent challenge of imbalanced class distribution in real-world classification scenarios, F1-score especially serves as a valuable metric for a more sophisticated evaluation of model performance.

Comparison methods

To thoroughly evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed ALDNet classifier, we conducted a comprehensive comparison with six established methodologies widely employed in practical applications. The methodologies considered are as follows:

-

1.

Support vector machine (SVM): A classifier that seeks a decision boundary to maximize the separation between data points of different classes, subject to specific conditions 32.

-

2.

Decision tree: A hierarchical model that recursively splits data based on attribute significance 33.

-

3.

Random forest: An ensemble of decision trees designed to improve generalization performance 34.

-

4.

Naive Bayes: A probabilistic model based on Bayes’ theorem with independence assumptions 35.

-

5.

K-nearest neighbor (KNN): An algorithm classifying data points by referencing the labels of the k nearest neighbors 36.

-

6.

XGBoost: A gradient boosting framework that iteratively improves classification by re-weighting misclassified samples 37.

Furthermore, to assess the effectiveness of the proposed UEDSM, we compared it with seven other widely used methods for handling imbalanced data.

-

1.

ClusterCentroids: An under-sampling method strategically reducing the majority class by replacing a cluster of majority samples with the cluster centroid determined by a k-means algorithm 38.

-

2.

NearMiss: An under-sampling method systematically eliminating samples from the majority class in a random fashion 39.

-

3.

TomekLinks: An under-sampling method adequately employed to identify samples from the majority class with the minimal euclidean distance to the minority class 40.

-

4.

SMOTETomek: An integrated over-and-under-sampling strategy harnessing the synergy of SMOTE and Tomek link 41.

-

5.

ADASYN: An over-sampling method generating diverse sample quantities based on an estimate of the local distribution of the target class 42.

-

6.

KMeansSMOTE: An over-sampling method implementing k-means clustering prior to oversampling through SMOTE 43.

-

7.

BorderlineSMOTE: An over-sampling method grounded in SMOTE, selectively utilizing a few class samples on the border to generate better samples 44.

Experimental results and discussion

This section delves into a comprehensive analysis of the experimental results obtained from the proposed framework, comparing it with several other methods. The enhancements are fully examined in terms of accuracy and F1-score.

Effectiveness of UEDSM

The impact of the UEDSM was rigorously assessed through a comprehensive comparative analysis across two distinct scenarios: model performance with and without UEDSM application prior to training. A critical parameter, u, representing the number of subsequent time steps, was set to five, enabling the classification models to predict air leakage occurrences five minutes in advance. This forward-looking approach significantly enhances the practical utility of the models in real-world manufacturing environments, providing a crucial window for preventive action.

Table 2 presents a detailed overview of the experimental results, revealing substantial performance enhancements in both accuracy and F1-score metrics across the air compressor datasets. The integration of UEDSM consistently yields superior performance in the majority of cases, underscoring its efficacy in addressing class imbalance and enhancing the models’ discriminative capabilities. This consistency suggests that UEDSM’s impact is robust across different model architectures and data distributions, a crucial factor for its broad applicability in industrial settings. A deeper examination of the results uncovers several key insights regarding the performance of the models. The magnitude of improvement varies across models and datasets, indicating that UEDSM’s effectiveness is influenced by the underlying model architecture and the specific characteristics of each dataset. This variability emphasizes the complexity of the class imbalance problem in industrial data and highlights the necessity for tailored approaches in various manufacturing scenarios.

Notably, the ALDNet model demonstrates remarkable improvements, particularly in F1-score metrics. For the first air compressor dataset, ALDNet’s F1-score increased from 82.60% to 84.00%, while in the second dataset, a substantial improvement from 72.06% to 80.10% was observed. This significant enhancement in F1-score, especially for the second dataset, highlights ALDNet’s superior ability to leverage the balanced dataset produced by UEDSM. The performance gap between ALDNet and other models widens after UEDSM application, particularly for the second air compressor dataset, suggesting that ALDNet’s architecture is particularly well-suited to exploit the balanced dataset produced by UEDSM.

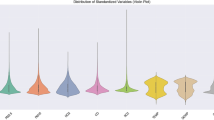

ALDNet’s consistent performance improvement across both datasets indicates a high degree of generalizability, a crucial factor for practical applications in diverse industrial settings. This robustness across datasets is particularly valuable in manufacturing environments where conditions may vary significantly between different air compressors or production lines. Interestingly, some models (e.g., Naive Bayes) show a decrease in certain metrics after UEDSM application. This observation highlights the complexity of the class imbalance problem and suggests that UEDSM’s effectiveness may vary depending on the underlying assumptions of each model. It also underscores the importance of careful model selection when implementing UEDSM in real-world scenarios. The graphical representation of these trends in Fig. 2 further corroborates the statistical findings, providing a visual confirmation of ALDNet’s superiority when combined with UEDSM. This visual analysis aids in identifying patterns and relationships that might not be immediately apparent from the numerical data alone, offering additional insights into the performance characteristics of different models under UEDSM.

These results have significant implications for the field of air leakage detection in smart manufacturing. The combination of ALDNet and UEDSM demonstrates superior classification accuracy and robust performance across different compressor datasets, suggesting high potential for real-world implementation. The models’ ability to predict air leakage five minutes in advance provides a crucial window for preventive action, potentially reducing downtime and maintenance costs in manufacturing environments. Furthermore, the consistent improvement across models after UEDSM application underscores the importance of addressing class imbalance in industrial datasets, where anomalies are often rare but critical events. This finding has broader implications for anomaly detection in various industrial processes, potentially leading to more efficient and reliable manufacturing operations.

In conclusion, the synergy between ALDNet and UEDSM not only demonstrates superior performance in air leakage detection but also opens avenues for further research in handling imbalanced datasets in industrial applications.

Classification performance with alternative data sampling methods for the first air compressor

Table 3 presents a comprehensive analysis of classification performance across eight data sampling methods, including UEDSM, applied to the first air compressor dataset. This comparative study aims to elucidate the optimal pairing between data sampling methods and classification models, providing crucial insights for performance optimization in early air leakage detection. A critical observation emerges regarding the NearMiss method, which consistently underperforms across all classification models. Its F1-scores remain consistently below 10%, with accuracy rates failing to exceed 35%. This stark underperformance renders NearMiss unsuitable for the critical task of early air leakage detection.

The data reveals nuanced relationships between sampling methods and classification models. UEDSM demonstrates superior efficacy when paired with ALDNet and SVM, while TomekLinks significantly enhances the performance of Decision Tree, Random Forest, and KNN models. This variability in optimal pairings underscores the importance of tailored approaches in addressing class imbalance for different model architectures. Figure 3 illustrates the optimal combinations of classification models and data sampling methods. Notably, ALDNet coupled with UEDSM achieves the highest performance, boasting an accuracy of 98.69% and an F1-score of 84.00%. This combination outperforms all other pairings, including the second-best performer, Random Forest with TomekLinks. A quantitative comparison reveals that the ALDNet-UEDSM combination surpasses the least effective pairing (Naive Bayes with KMeansSMOTE) by a substantial 6.23% in F1-score. This significant performance gap highlights the potential impact of choosing the optimal model-sampling method combination in practical applications. The superior performance of ALDNet with UEDSM can be attributed to several factors, including UEDSM’s ability to effectively balance the dataset while preserving the underlying data structure, ALDNet’s architecture, which appears particularly adept at leveraging the balanced dataset produced by UEDSM, and the potential synergy between ALDNet’s dropout mechanism and UEDSM’s data augmentation approach, enhancing model generalization. These findings have significant implications for the field of air leakage detection in smart manufacturing, suggesting that the combination of ALDNet and UEDSM could substantially improve early detection capabilities.

Classification performance with alternative data sampling methods for the second air compressor

Table 4 presents a comprehensive analysis of classification performance across eight data sampling methods applied to the second air compressor dataset. Consistent with the findings from the first dataset, the NearMiss method demonstrates a detrimental impact on most classification models, resulting in significantly reduced accuracy and F1-scores. This consistent underperformance across both datasets strongly suggests that NearMiss is ill-suited for the specific characteristics of air leakage detection data. A notable observation is the persistent challenge faced by the Decision Tree model, which fails to achieve accuracy above 90% or F1-scores exceeding 70% regardless of the sampling method employed. In contrast, UEDSM shows broader efficacy in this scenario, enhancing the performance of ALDNet, SVM, Random Forest, and XGBoost, underscoring its adaptability to different data distributions and potential as a robust sampling method across various model architectures.

The optimal combinations of classification models and sampling methods, as illustrated in Fig. 4, reveal interesting patterns. While UEDSM remains the preferred method for several models, other sampling techniques show specific strengths with certain models. For instance, ClusterCentroids pairs well with Decision Tree, KMeansSMOTE with Naive Bayes, and ADASYN with KNN. Notably, the ALDNet-UEDSM combination maintains its superior performance, achieving the highest accuracy (95.54%) and being the only model to surpass an 80% F1-score (80.10%). This consistent excellence across both datasets reinforces the robustness and generalizability of the ALDNet-UEDSM approach in air leakage detection. A comparative analysis reveals that the second-best performer, SVM with UEDSM, achieves an F1-score of 78.68%, which is 1.42% points lower than ALDNet with UEDSM.

The experimental results from both air compressor datasets consistently demonstrate the superior performance of the ALDNet-UEDSM combination in early air leakage detection. This robust performance across different datasets underscores the potential of this approach for practical implementation in diverse industrial settings, offering a promising solution for enhancing manufacturing efficiency via improved air leakage detection performance.

Hyperparameter selection and sensitivity

The two hyperparameters that most strongly affect the proposed framework are the removal ratio p in UEDSM and the dropout rate in ALDNet. Since the clustering procedure in UEDSM is inherently binary, the number of clusters k is fixed to two and does not require additional tuning.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis by varying the removal ratio p \(\in \{0.35, 0.55, 0.75, 0.90, 0.95\}\) and dropout rates \(\in \{0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6\}\). The experimental results are summarized in Tables 5 and 6. On the first compressor, the best performance was obtained with p = 0.75 and dropout = 0.3, reaching 98.69% accuracy and 84.00% F1-score. On the second compressor, the same configuration yielded 95.54% accuracy and 80.10% F1-score.

Beyond identifying the optimal setting, the analysis provides two important observations. First, performance remained relatively stable across neighboring configurations (e.g., p = 0.55–0.90 and dropout = 0.2–0.5), which indicates robustness of the framework to moderate parameter shifts. This stability is particularly relevant for industrial deployment, where precise hyperparameter re-tuning may not always be feasible. Second, extreme parameter values degraded performance. For example, very low dropout (0.1) or very high dropout (0.6) reduced the F1-score, reflecting either under-regularization or excessive information loss.

Overall, these results justify the choice of \(p = 0.75\) and dropout = 0.3 as the default setting. The sensitivity analysis confirms that the proposed framework is not only effective at its optimal parameters but also resilient across a broad range, ensuring reproducibility and practicality in real-world manufacturing environments.

Methods

The proposed architecture for air leakage detection, as depicted in Fig. 5, incorporates three key components. Firstly, air compressors serve as the cornerstone by capturing several numeric features that characterize their condition, including the blow-off valve (BOV), inlet guide vane (IGV), and air temperature. Subsequently, the edge server accommodates a customized model for air leakage detection in each air compressor, facilitating early notifications and anticipating potential incidents several minutes in advance. Lastly, the Amazon AWS cloud server is utilized for training the classification model, ALDNet, employing the data sampling method called UEDSM. After training, these models are deployed on the edge server for efficient inference. This concise and integrated architecture ensures the effective monitoring and timely prediction of air leakage incidents.

Time series data preprocessing

The data from each air compressor is fully treated as a multivariate time series, represented as an ordered sequence comprising \(M \in \mathbb {N}\) streams, where \(\varvec{a}_{m}=(a_{m,1}, \dots , a_{m,L})\). Mathematically, this is represented as

where M denotes the total number of features or variables, while L represents the length of the time series. Next, to mitigate challenges such as multicollinearity and high correlation45, known for inducing overfitting problems, we employ the pearson correlation coefficient. This coefficient is computed for all pairs of features, producing values within the range of [-1, 1]. The computation is expressed by

where \(\bar{\varvec{a}_{i}}\) and \(\bar{\varvec{a}_{i}}\) denote the means of the respective features. A threshold \(\tau\) is set, such that if \(|\rho _{\varvec{a}_{i}\varvec{a}_{j}}|\ge \tau\), it signifies high correlation between features \(\varvec{a}_{i}\) and \(\varvec{a}_{j}\). We then define a set E containing n features to be eliminated. In the event of high correlation between two features, one of them is selected for removal, with the choice guided by domain knowledge. The final multivariate time series without highly correlated pairs is denoted as

In addition, its corresponding label \(y_{t}\) at each time step t can be encoded as 0, signifying normal condition, or 1, indicating an air leakage incident. This encoding relies on two pivotal features, BOV and IGV, in our problem. Assuming \(\varvec{a}_{i}\) and \(\varvec{a}_{j}\) respectively stand for the BOV and IGV features, the label \(y_t\) is then determined by

where \(0 <r \le u\) and \(u \in \mathbb {W}\) is the number of subsequent time steps. In this paper, the labeled set is thus denoted by

Data sampling method (UEDSM)

In general, the issue of imbalanced datasets emerges in classification, where the number of instances in one class is notably lower than in the others46,47. The primary challenge in addressing this imbalance is that smaller classes are often more informative, yet standard classifiers tend to be biased toward the larger classes, potentially overlooking the significance of the smaller ones. Consequently, class imbalance can significantly impair the performance of a classification model. In this paper, we propose an unsupervised-enhanced data sampling method (UEDSM) to tackle this challenge. As depicted in Fig. 6, the proposed UEDSM integrates three main components: principal component analysis, k-means clustering, and cluster similarity scoring.

Principal component analysis (PCA)

PCA serves as a linear dimensionality reduction method, transforming higher-dimensional data into a lower dimension by maximizing the variance of the lower dimension. This multivariate analysis technique reduces dataset complexity while preserving data covariance48. Initially, we perform feature scaling on \(A'\) to obtain the standardized \(\hat{A'}\), ensuring a distribution with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one using StandardScaler49. Subsequently, PCA is applied to the standardized \(\hat{A'}\) following the procedures outlined in Algorithm 1. These procedures involve computing the covariance matrix of the sample, decomposing eigenvalues, and selecting the eigenvectors corresponding to the largest k eigenvalues, which are then formed into a projection matrix50. In the end, a new multivariate time series with k-dimensional features, denoted by B, is created and later used in cluster similarity scoring. This is formally expressed as

where k is fixed at two, given that the classification is binary in this paper.

K-means clustering

The k-means approach is a widely adopted unsupervised modeling technique, known for its simplicity and frequent use in dividing datasets into k classes51. Its effectiveness lies in categorizing objects into groups with distinct characteristics, making it especially valuable for labeling unlabeled datasets. In this paper, a labeled set \(Y'\) completely derived from k-means clustering is utilized for comparison with the initially predefined labeled set Y. Thus, given \(\hat{A'}\), the k-means clustering algorithm, as outlined in Algorithm 2, is executed to partition a set of samples based on their attributes into k clusters. The principal steps of k-means clustering include initializing cluster centers, assigning data points to clusters, and updating cluster centers until convergence52.

As a consequence of the k-means clustering process, a new set \(Y'\) is obtained, which will be further used in cluster similarity scoring phase. This labeled set not only captures the inherent patterns within the data but also serves as a tool for improving the understanding of the underlying structure. The iterative nature of the algorithm ensures the refinement of clusters to accurately represent the data distribution, making \(Y'\) a reliable foundation for subsequent analyses. For this specific problem, k is set to two, as the choice of \(k=2\) aligns undoubtedly with the binary nature of the classification task in our problem, simplifying the interpretation of outcomes and facilitating meaningful comparisons with the original labeled set Y.

Cluster similarity scoring

To address class imbalance, this paper introduces the concept of cluster similarity scoring, a method designed to selectively remove a fraction p of instances from the majority class that overlaps with the unsupervised cluster showing the highest similarity. Given Y and \(Y'\), the newly transformed multivariate time series with k-dimensional features B facilitates the identification of each cluster corresponding to its binary class. These clusters are denoted as \(c^{Y}_{z}\) and \(c^{Y'}_{z}\), as illustrated in Fig. 7, providing a visual representation of the concept.

Herein, the cluster similarity score (CSS) can be mathematically computed as

where the score ranges between 0 and 1, h represents the majority class from Y, and both \(\overline{c}^{Y}_{h}\) and \(\overline{c}^{Y'}_{z}\), represented as vectors, denote the mean values of their respective clusters. The class with the highest similarity score, denoted by \(z_\text {max}\), can be determined as

Now, consider I as the representation of the intersection of indices between the clusters \(\overline{c}^{Y}_{h}\) and \(\overline{c}^{Y'}_{z_\text {max}}\) for the class of interest. In the subsequent step, a specified fraction p of the common indices within I is randomly deleted. Following this, both \(\hat{A'}\) and Y undergo an update by removing these common indices, ensuring that the dataset reflects the altered distribution.

Lastly, to address any remaining imbalances, the synthetic minority over-sampling technique (SMOTE) method53 is applied to achieve a balanced overall dataset. The comprehensive procedure of the proposed unsupervised-enhanced data sampling method (UEDSM) is explicitly outlined in Algorithm 3 for clarity and reproducibility. Next, we delve into the classification model, which we refer to as ALDNet.

Classification model (ALDNet)

The paper introduces ALDNet, a dropout-enabled deep neural network specially designed for air leakage detection. ALDNet leverages Monte Carlo Dropout (MC Dropout)54, an advanced extension of the dropout regularization technique renowned for its efficacy in enhancing generalization and mitigating overfitting in neural networks.

In conventional dropout, neurons are randomly excluded during both forward and backward passes in each training iteration. MC Dropout extends this concept to the prediction phase, executing multiple forward passes with dropout activation. This results in an ensemble of predictions for each input, with the final prediction derived through aggregation. Formally, for a neural network with weight matrix Q, the dropout operation can be mathematically expressed as

where \(\lambda\) is a binary mask with elements drawn from a Bernoulli distribution with probability s, and \(\odot\) denotes element-wise multiplication. Now, MC Dropout extends this concept to the inference phase, performing T stochastic forward passes through the network. For an input x, the MC Dropout prediction is given by

where \(f_Q\) represents the neural network function, and \(\lambda _d\) is the dropout mask for the d-th forward pass.

As depicted in Fig. 8, the architecture of ALDNet comprises four hidden layers with 32, 32, 16, and 9 neurons, respectively. Each hidden layer is followed by a dropout layer with a retention probability of 0.7 (dropout rate of 0.3). The hyperbolic tangent activation function is employed in each hidden layer, defined as

where \(\omega _l\) is the output of the l-th layer, \(Q_l\) is the weight matrix, and \(b_l\) is the bias vector. The incorporation of MC Dropout during inference enables uncertainty estimation, crucial for assessing model confidence in air leakage detection. The predictive uncertainty can be approximated using the variance of the MC samples:

This approach provides a measure of epistemic uncertainty, reflecting the model’s uncertainty in its parameters55.

Overall, the implementation of MC Dropout in ALDNet offers several advantages over alternative methods, particularly in terms of model robustness and reliability in air leakage detection scenarios. By providing both predictions and associated uncertainties, ALDNet enables more informed decision-making in critical manufacturing environments where early and accurate detection of air leakage is paramount.

Conclusion

The digital transformation of manufacturing companies has emerged as a critical focus in strategic management, as highlighted by recent studies56,57. This shift presents significant opportunities for optimizing operational efficiency and reducing costs. Our research directly addresses this trend by introducing a pioneering methodology for the early detection of air leakage in air compressors, a persistent and costly issue in manufacturing plants. By developing an automated solution for proactive air leakage identification, we not only mitigate resource wastage but also minimize human intervention, thereby enhancing overall operational efficiency. This aligns with the broader goals of Industry 4.0 and smart manufacturing initiatives, where data-driven decision-making and predictive maintenance are key pillars.

The efficacy of our approach is rigorously validated through comprehensive experiments utilizing real-time physical monitoring of two air compressors within a South Korean manufacturing plant. In particular, the proposed unsupervised-enhanced data sampling method (UEDSM) proved effective in alleviating class imbalance, a major obstacle in industrial anomaly detection. When combined with the dropout-enabled ALDNet classifier, the unified framework consistently outperformed conventional models and alternative sampling techniques. This integration delivered robust, reliable predictions for early leakage detection, demonstrating its practical value in improving operational reliability and reducing maintenance costs.

While the proposed framework demonstrates strong performance, certain limitations remain. The experiments were limited to two air compressors in a single industrial site, which may affect generalizability to broader manufacturing contexts. Additionally, the framework does not explicitly address long-term data drift or evolving machine behavior. Future work could expand validation across multiple industrial sites, incorporate adaptive mechanisms for handling temporal drift, and extend uncertainty modeling to include aleatoric as well as epistemic components. Furthermore, integrating concepts from active learning, such as uncertainty-guided sample selection, may further enhance applicability in scenarios where labeled data are scarce or costly to obtain.

Data availibility

The data that support the findings of this study are available from ETRI and Hyundai Infracore but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. However, data are available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author, Prof. Kim (jk.kim@sejong.ac.kr), and with permission of ETRI and Hyundai Infracore.

References

Son, Y. H., Kim, G.-Y., Kim, H. C., Jun, C. & Noh, S. D. Past, present, and future research of digital twin for smart manufacturing. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 9, 1–23 (2022).

Ransikarbum, K., Pitakaso, R., Kim, N. & Ma, J. Multicriteria decision analysis framework for part orientation analysis in additive manufacturing. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 8, 1141–1157 (2021).

Lee, G. H., Park, H., Jang, J. W., Han, J. & Choi, J. K. Ppo-based autonomous transmission period control system in IoT edge computing. IEEE Internet Things J. 10(24), 21705–21720 (2023).

Han, J., Lee, G. H., Lee, J. & Choi, J. K. IEC-TPC: An imputation error cluster-based approach for energy optimization in IoT data transmission period control. IEEE Internet Things J. 11(5), 7841–7862 (2023).

Silva, F. S. T., da Costa, C. A., Crovato, C. D. P. & da Rosa Righi, R. Looking at energy through the lens of industry 4.0: A systematic literature review of concerns and challenges. Comput. Ind. Eng. 143, 106426 (2020).

Zhou, K. et al. Estimation of the natural gas leakage source with different monitoring sensor networks in an underground utility tunnel: From the perspectives of energy security. Energy Build. 254, 111645 (2022).

Baptista, M. et al. Forecasting fault events for predictive maintenance using data-driven techniques and arma modeling. Comput. Ind. Eng. 115, 41–53 (2018).

Soares, C. Gas turbines: A handbook of air, land and sea applications (Elsevier, 2011).

Geng, D., Evans, S. & Kishita, Y. The identification and classification of energy waste for efficient energy supervision in manufacturing factories. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 182, 113409 (2023).

Casillas, A., Modera, M. & Pritoni, M. Using non-invasive mems pressure sensors for measuring building envelope air leakage. Energy Build. 233, 110653 (2021).

Tong, K., Wang, Z., Si, L., Tan, C. & Li, P. A novel pipeline leak recognition method of mine air compressor based on infrared thermal image using IFA and SVM. Appl. Sci. 10, 5991 (2020).

Ma, D., Gao, J., Zhang, Z., Zhao, H. & Wang, Q. Locating the gas leakage source in the atmosphere using the dispersion wave method. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 63, 104031 (2020).

Abela, K., Refalo, P. & Francalanza, E. Analysis of pneumatic parameters to identify leakages and faults on the demand side of a compressed air system. Clean. Eng. Technol. 6, 100355 (2022).

Czopek, D., Gryboś, D., Leszczyński, J. & Wiciak, J. Identification of energy wastes through sound analysis in compressed air systems. Energy 239, 122122 (2022).

Audibert, J., Michiardi, P., Guyard, F., Marti, S. & Zuluaga, M. A. Do deep neural networks contribute to multivariate time series anomaly detection?. Pattern Recogn. 132, 108945 (2022).

Han, J., Lee, G. H., Park, S., Lee, J. & Choi, J. K. A multivariate-time-series-prediction-based adaptive data transmission period control algorithm for IoT networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 9, 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1109/JIOT.2021.3124673 (2022).

Nagarajan, S., Kayalvizhi, S., Subhashini, R. & Anitha, V. Hybrid honey badger-world cup algorithm-based deep learning for malicious intrusion detection in industrial control systems. Comput. Ind. Eng. 180, 109166 (2023).

Lene, E. Data-driven manufacturing monitoring. J. Smart Manuf. 34, 45–59 (2021).

Eret, P. & Meskell, C. Microphone arrays as a leakage detection tool in industrial compressed air systems. Adv. Acoust. Vib. 2012(1), 689379 (2012).

Yang, Q., Guo, B. & Lin, M. Differential pressure prediction in air leak detection using rbf neural network. In 2010 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computational Intelligence, vol. 1, 211–213 (IEEE, 2010).

Cheng, F., Cai, W., Zhang, X., Liao, H. & Cui, C. Fault detection and diagnosis for air handling unit based on multiscale convolutional neural networks. Energy Build. 236, 110795 (2021).

Quan, X. et al. Prediction of air leakage rate of sintering furnace based on bp neural network optimized by PSO. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 1, 5631787 (2022).

Santolamazza, A., Cesarotti, V. & Introna, V. Anomaly detection in energy consumption for condition-based maintenance of compressed air generation systems: An approach based on artificial neural networks. IFAC-PapersOnLine 51, 1131–1136 (2018).

Salmanov, K. & Harb, H. Data analysis for the aero derivative engines bleed system failure identification and prediction. Int. J. Intell. Syst. Appl. (IJISA) 13, 13–24 (2021).

Lee, W. J. Anomaly detection and severity prediction of air leakage in train braking pipes. Int. J. Progn. Health Manag.8 (2017).

Kim, M.-J., Cho, H.-J. & Kang, C.-G. Anomaly detection of an air compressor from time-series measurement data. In 2022 22nd International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems (ICCAS), 825–828 (IEEE, 2022).

Nuggehalli, S., Zhang, J., Jain, L. & Nowak, R. Direct: Deep active learning under imbalance and label noise. arXiv:2312.09196 (2023).

Jin, Q., Yuan, M., Wang, H., Wang, M. & Song, Z. Deep active learning models for imbalanced image classification. Knowl.-Based Syst. 257, 109817 (2022).

Zhang, J., Katz-Samuels, J. & Nowak, R. Galaxy: Graph-based active learning at the extreme. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 26223–26238 (PMLR, 2022).

Khan, S., Hayat, M., Zamir, S. W., Shen, J. & Shao, L. Striking the right balance with uncertainty. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 103–112 (2019).

Baltaci, Z. S. et al. Class uncertainty: A measure to mitigate class imbalance. arXiv:2311.14090 (2023).

Hearst, M. A., Dumais, S. T., Osuna, E., Platt, J. & Scholkopf, B. Support vector machines. IEEE Intell. Syst. Appl. 13, 18–28 (1998).

Song, Y.-Y. & Ying, L. Decision tree methods: Applications for classification and prediction. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 27, 130 (2015).

Belgiu, M. & Drăguţ, L. Random forest in remote sensing: A review of applications and future directions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. 114, 24–31 (2016).

Zhang, H. The optimality of naive bayes. Aa 1, 3 (2004).

Peterson, L. E. K-nearest neighbor. Scholarpedia 4, 1883 (2009).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 785–794 (2016).

Lemaître, G., Nogueira, F. & Aridas, C. K. Imbalanced-learn: A python toolbox to tackle the curse of imbalanced datasets in machine learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 18, 1–5 (2017).

Mani, I. & Zhang, I. knn approach to unbalanced data distributions: a case study involving information extraction. In Proceedings of workshop on learning from imbalanced datasets, vol. 126, 1–7 (ICML, 2003).

Tomek, I. Two modifications of CNN (Man, and Cybernetics, IEEE Transactions on Systems, 1976).

Batista, G. E. et al. Balancing training data for automated annotation of keywords: A case study. Wob 3, 10–8 (2003).

He, H., Bai, Y., Garcia, E. A. & Li, S. Adasyn: Adaptive synthetic sampling approach for imbalanced learning. In 2008 IEEE international joint conference on neural networks (IEEE world congress on computational intelligence), 1322–1328 (IEEE, 2008).

Douzas, G., Bacao, F. & Last, F. Improving imbalanced learning through a heuristic oversampling method based on k-means and smote. Inf. Sci. 465, 1–20 (2018).

Han, H., Wang, W.-Y. & Mao, B.-H. Borderline-smote: a new over-sampling method in imbalanced data sets learning. In International conference on intelligent computing, 878–887 (Springer, 2005).

Katrutsa, A. & Strijov, V. Comprehensive study of feature selection methods to solve multicollinearity problem according to evaluation criteria. Expert Syst. Appl. 76, 1–11 (2017).

Menardi, G. & Torelli, N. Training and assessing classification rules with imbalanced data. Data Min. Knowl. Disc. 28, 92–122 (2014).

Rathi, S. C. et al. Empirical evaluation of the performance of data sampling and feature selection techniques for software fault prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 223, 119806 (2023).

Basak, H., Kundu, R., Chakraborty, S. & Das, N. Cervical cytology classification using pca and gwo enhanced deep features selection. SN Comput. Sci. 2, 369 (2021).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Wold, S., Esbensen, K. & Geladi, P. Principal component analysis. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2, 37–52 (1987).

Windarto, A. P. et al. Analysis of the k-means algorithm on clean water customers based on the province. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series, vol. 1255, 012001 (IOP Publishing, 2019).

Hartigan, J. A. & Wong, M. A. Algorithm as 136: A k-means clustering algorithm. J. Roy. Stat. Soc.: Ser. C (Appl. Stat.) 28, 100–108 (1979).

Fernández, A., Garcia, S., Herrera, F. & Chawla, N. V. Smote for learning from imbalanced data: progress and challenges, marking the 15-year anniversary. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 61, 863–905 (2018).

Gal, Y. & Ghahramani, Z. Dropout as a bayesian approximation: Representing model uncertainty in deep learning. In International conference on machine learning, 1050–1059 (PMLR, 2016).

Zhu, L. & Laptev, N. Deep and confident prediction for time series at uber. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops (ICDMW), 103–110 (IEEE, 2017).

Liu, C. Risk prediction of digital transformation of manufacturing supply chain based on principal component analysis and backpropagation artificial neural network. Alex. Eng. J. 61, 775–784 (2022).

Melanie Pfaff, Y., Judith Wohlleber, A., Münch, C., Küffner, C. & Hartmann, E. How digital transformation impacts organizational culture – a multi-hierarchical perspective on the manufacturing sector. Comput. Ind. Eng. 183, 109432 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the Korea Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP) and the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE) of the Republic of Korea (No. RS-2025-16064197) and in part by the ”Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE)” through the Seoul RISE Center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Seoul Metropolitan Government (2025-RISE-01-019-04).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.H.L. conceptualized and implemented the methodology, wrote the draft manuscript, and created the visualizations. J.K. supervised the study and contributed to validation and manuscript writing. Y.-S.Y. and I.-W.L. contributed to methodology, validation, and review. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Yoon-Sik Yoo and Il-Woo Lee are affiliated with ETRI (Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute), a public research institute. The authors intend to file a patent application related to the method described in this manuscript. This is declared as a potential competing financial interest. Other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, G.H., Kim, J., Yoo, YS. et al. Early detection of air leakage in IoT-connected compressors using enhanced data sampling with deep learning. Sci Rep 16, 1096 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29522-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29522-0