Abstract

Accurately differentiating scaly erythematous rashes among psoriasis, eczema, and dermatophytosis remains a clinical challenge, particularly for non-dermatologists. This study aimed to develop and evaluate deep learning models using macroscopic clinical images to classify these conditions and compare their performance with that of non-specialists. A total of 2940 images were sourced from public datasets, the Siriraj Dermatology databank, and newly collected images from Thai participants. Among sixteen evaluated models, the Swin demonstrated the best performance and interpretability. Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) visualizations confirmed that the model focused on clinically relevant lesion features. Most importantly, in a pilot comparison, the Swin outperformed non-specialists in diagnostic accuracy. However, given the limited sample size of 30 images and 30 evaluators, these results should be interpreted as exploratory. Future studies with larger datasets and diverse clinician cohorts are warranted to confirm these findings and to support clinical integration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psoriasis, eczema, and dermatophytosis are common skin diseases characterized by erythematous papules or plaques with scales, frequently encountered in routine clinical practice1. Although these diseases have distinct etiologies, psoriasis is an immune-mediated disorder with keratinocyte hyperproliferation2, eczema involving skin barrier dysfunction and immune dysregulation3, and dermatophytosis caused by superficial fungal infection4, they often present overlapping clinical features. This overlap contributes to diagnostic challenges, particularly among non-specialists, where misdiagnosis can result in inappropriate treatments that may exacerbate symptoms.5.

Diagnostic accuracy in general practice remains limited, with some studies reporting accuracy rates as low as 50% for common skin diseases6. The increasing demand for dermatological care, especially in resource-constrained and rural settings, underscores the need for diagnostic tools that support non-specialists in clinical decision-making.

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have demonstrated impressive capabilities in dermatologic image classification, often surpassing human performance in identifying skin cancers and other defined lesions7,8,9,10. For instance, AI systems have achieved up to 99% accuracy in differentiating melanoma from benign lesions7,11, and have performed well in detecting psoriasis and multiple skin diseases across various tasks7,12. However, accurate multiclass differentiation of erythematous scaly rashes, specifically psoriasis, eczema, and dermatophytosis, remains underexplored, with reported accuracies ranging from 89.1 to 96.2%9,13,14.

Limitations of current models include their reliance on dermoscopic images and training on predominantly lighter skin phototypes, which may hinder generalizability to diverse populations and practical use in primary care8. In contrast, macroscopic clinical images captured via smartphones represent a more accessible format for real-world implementation, despite inherent quality variability. Leveraging AI to analyze such images could enhance dermatologic support in broader clinical environments.

This study addresses these gaps by developing and evaluating an AI framework to classify psoriasis, eczema, and dermatophytosis from macroscopic clinical images. We trained eight convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and eight Transformer-based models on a dataset of 2940 images from both public sources and Thai patients. Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) was used to visualize model interpretability. Finally, we compared the diagnostic performance of our best-performing deep learning model with that of non-specialist clinicians to evaluate its practical utility.

Methods

The protocol for this study was approved by the Siriraj Institutional Review Board of the Siriraj Hospital of the Faculty of Medicine of Mahidol University (MU-MOU COA no. 073/2023). This study complied with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and all its subsequent amendments. The eligible skin lesion images were clinical images of scaly, erythematous rashes, with the final diagnosis of plaque psoriasis, eczema, or dermatophytosis (Figure 1). All patients contributing new images provided written informed consent for the use of their images in research, academic publication, and anonymized data sharing. Skin lesions on the face, neck, and groin, as well as tattoos or scars, were excluded due to the Personal Data Protection Act, which has been enforced in Thailand since June 2022.

Data acquisition

A total of 2940 photographs were included in this study, sourced from two primary categories: existing databanks and newly collected patient images. The existing databanks contributed 1320 images, comprising 308 images from the Siriraj Dermatology databank and 1012 images from public repositories, including DermNet15. The Siriraj Dermatology databank comprises images of Thai participants diagnosed with a range of skin diseases by experienced dermatologists employing state-of-the-art diagnostic methods. Participants provided informed consent for their images to be used in educational, research, and publication contexts. Dermatophytosis cases in this databank were confirmed through clinical manifestations and positive potassium hydroxide (KOH) examinations showing branching and septate hyphae.The diagnosis of psoriasis and eczema in the Siriraj Dermatology databank were also made by three experienced dermatologists, each with over 10 years of expertise in the field. For the public databank, the images were also reviewed and confirmed by the same three dermatologists. Notably, the combined dataset captures a broad spectrum of image characteristics—such as variation in quality, perspective, skin tone, and acquisition protocols. In the context of computer vision, training deep learning models on such diverse conditions can enhance model robustness, as it encourages generalization across real-world scenarios. Accordingly, the inclusion of diverse image sources may contribute to the stability and reliability of the model’s performance across a wide range of clinical settings and input variations.

The newly collected dataset included 1620 images, obtained from Thai participants aged 18 years or older with scaly erythematous rashes and a confirmed diagnosis of psoriasis. Participants were recruited from the outpatient clinic at Siriraj Hospital and provided informed consent before inclusion in the study. Lesions were photographed using three different smartphone models: iPhone 11, 13, and 14 Pro (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA); Samsung Galaxy A33 (Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., Suwon, South Korea); and Oppo A78 (Guangdong Oppo Mobile Telecommunications Corp., Ltd., Dongguan, China). Images were taken under consistent ambient lighting with a neutral green background and fixed distance ( 30 cm) to ensure reproducibility. Device flash was used under controlled conditions to enhance lesion detail without overexposure. Autofocus and exposure-lock features were used to maintain image sharpness and consistency across participants (Figure 2).

For each lesion, 18 photographs were captured: three angles (frontal, 30° left, 30° right) under both flash and non-flash conditions, with duplicate shots for quality assurance. From this set, one representative image per lesion was selected for inclusion, based on clarity, color balance, and lesion visibility. This selection was conducted by three dermatologists with over 10 years of clinical experience, using a consensus process to ensure diagnostic quality and consistency. An overview of the dataset is presented in Table 1.

Data preparation and data augmentation

To ensure that the training data were standardized, diverse, and suitable for effective training of both CNN and Transformer models, four steps of data preparation and augmentation (as shown in Fig. 2) were applied as follows. To minimize inter-device color variability and ensure consistency, all images underwent pixel intensity normalization to zero mean and unit variance, a standard procedure in deep learning workflows. This process adjusts brightness and contrast automatically without altering clinical features. No manual color correction or enhancement was applied. Although Figure 2 illustrates natural color variation due to lighting and skin tone, normalization ensured that models were not biased by these differences.

Step 1: Zero-padding to square image

To ensure consistency in input dimensions, we applied zero-padding to convert all images to a square shape. Zero-padding involves adding rows or columns of zeros around the image to make it square without altering the original content. This step helps maintain the aspect ratio and prevents distortion when resizing images later16.

Step 2: Random horizontal flip

Random horizontal flipping with a probability of 0.5 was performed to augment the dataset. This technique introduces variability by flipping images along the vertical axis, which can help the model become invariant to horizontal orientations of the skin lesions. Such augmentation can prevent the model from overfitting to specific orientations in the training data17.

Step 3: Resize image after padding and flipping

All images were resized to a specific resolution required by each model to ensure compatibility and consistent input dimensions during training. The original images before preprocessing ranged from 720 × 447 to 4024 × 6048 pixels, reflecting variability due to different devices and imaging conditions. This preprocessing step helped standardize the input format, facilitating batch processing and improving computational efficiency. The chosen resolution represented a trade-off between preserving essential visual features and maintaining a reasonable computational cost18.

Step 4: Normalize image

The images were normalized to have a consistent mean and standard deviation. Normalization scales the pixel values to a standard range, which helps to accelerate convergence during training and improves numerical stability. This step ensures that the neural network or convolutional neural network treats all input features equally19.

The final images for the development and testing of the algorithms had varying illumination effects and were divided into three sets: (i) training, (ii) validation, and (iii) testing data sets.

Implementation of Swin for skin lesion classification

An effective algorithm was developed based on CNN and Transformer architectures. The CNN models included eight existing architectures: AlexNet20, DenseNet-12121, EfficientNetV222, GoogLeNet23, MobileNetV324, SqueezeNet25, VGG-1926, and ResNet-5027. Additionally, the eight Transformer-based models included ViT28, Swin29, CvT30, DaViT31, MaxViT32, GC ViT33, FastViT-S1234, and SHViT-S135. These architectures were trained and validated to classify each skin disease from skin images, and subsequently evaluated on a separate test set to confirm that their performance remained consistent. The parameters of both the CNN and Transformer models are shown in Table 2. To evaluate reasonable or unreasonable predictions by the architectures, Grad-CAM visualizations were generated to highlight which important regions of the image correspond to any decision of interest by an architecture.

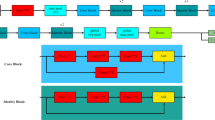

The architecture of the Swin used for classifying skin lesion images was shown in Figure 3. Swin29 is a hierarchical vision Transformer that introduces a novel shifted windowing mechanism for self-attention. It processes input images by dividing them into non-overlapping patches, which are then embedded into a sequence of tokens. The model consists of four stages, each comprising Swin Blocks that use either window-based multi-head self-attention (W-MSA) or shifted window-based self-attention (SW-MSA). These mechanisms allow the model to capture both local and global contextual information efficiently. Patch merging operations are applied between stages to progressively reduce spatial resolution and increase feature representation depth.

After feature extraction through the Swin blocks, the output is passed through an adaptive average pooling layer, which transforms variable-sized spatial features into a fixed-length feature vector. This vector is then input to a final fully connected layer that maps the features to class scores. In this study, we modified the final layer to contain three output nodes corresponding to the target classes: dermatophytosis, eczema, and psoriasis. The Swin is designed to be both computationally efficient and highly effective in capturing fine-grained image features relevant to medical imaging tasks such as skin lesion detection.

We used a pre-trained Swin model with weights from the ImageNet dataset36. To adapt it to our skin disease classification task, we applied transfer learning. This technique allowed a model that was trained on a large dataset, like ImageNet, to be reused for a different but related task. Instead of training from scratch, the model was fine-tuned on a smaller, specific dataset. This approach helped reduce training time, improves accuracy, and works well even when only a limited number of labeled medical images are available. Images of skin lesions were fed into the model to predict the corresponding disease class. To reduce overfitting and random split bias, the k-fold cross-validation technique was adopted, with the number of folds set to k = 5.

Comparing the performance results between non-dermatologists and the deep learning model

To evaluate and compare the diagnostic accuracy of the best-performing CNN and Transformer models against clinicians without specialized dermatology training, a pilot study was conducted. For this purpose, 10 images per disease category, representing cases of psoriasis, eczema, and dermatophytosis, were selected. These images were not used during any training, validation, or testing processes to ensure unbiased evaluation. Participants were presented with the question, “What is the most likely diagnosis?” along with the options: “A. Psoriasis, B. Eczema, C. Dermatophytosis.” The images were randomly integrated into an online questionnaire created using Google Forms.

The set of 30 images (10 per diagnostic class) used in the human-AI comparison was selected based on equal class representation and diagnostic clarity, rather than formal sample size calculation. This design aimed to facilitate a focused pilot comparison rather than a fully powered inferential study. Each image represented a distinct case from the test set, ensuring no overlap with the training or validation data. While the sample enabled qualitative and quantitative benchmarking across physician groups and AI, we acknowledge that it may be underpowered for detecting smaller inter-group differences and should be interpreted as exploratory.

Thirty clinicians without specialized dermatology training were recruited to voluntarily provide diagnoses for the 30 images. Participants were divided into two groups based on their clinical experience: the intern group, consisted of medical interns in their first postgraduate year of clinical training. These individuals had recently graduated from medical school and were working under supervision in hospital-based settings as part of their national service. And the internist group (n = 15) included board-certified internal medicine physicians with at least three years of clinical experience. They were involved in both outpatient and inpatient care at secondary hospitals but had no formal dermatology fellowship or extended dermatology rotations.

This comparison was designed to capture the influence of clinical experience on diagnostic performance among non-dermatologists. Interns represent entry-level clinical exposure, while internists embody more seasoned generalists. By including both, we aimed to assess how AI performance compares across different experience levels typical in primary and secondary care settings, where dermatology expertise is often limited.

Statistical analysis

Performance was evaluated using four metrics: precision, recall, F1 score, and accuracy, each ranging from 0 (very poor) to 1 (perfect). where TP = True Positives, FP = False Positives, TN = True Negatives, and FN = False Negatives. The formulas and interpretations of these metrics are provided below.

Precision is the ratio of correctly predicted positive observations to the total predicted positives.

where \(\text {TP}\) is True Positives and \(\text {FP}\) is False Positives. Precision is critical when the cost of false positives is high. For example, in medical diagnosis, predicting a disease when it is not present can lead to unnecessary treatment and anxiety. Precision helps ensure that when the model predicts a positive class, it is very likely to be correct. High precision indicates that the model has a low false positive rate, which is crucial for applications where false positives can be particularly costly.

Recall (or Sensitivity) is the ratio of correctly predicted positive observations to all observations in the actual class.

where \(\text {FN}\) is False Negatives. Recall is important when the cost of false negatives is high. For instance, in the same medical diagnosis example, missing a disease (false negative) can be very dangerous. Recall ensures that the model identifies as many actual positives as possible. High recall means that the model has a low false negative rate, which is essential in applications where missing a positive case could have serious consequences37.

F1 Score is the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall. It provides a single metric that balances both concerns.

The F1 Score is useful when you need to find a balance between Precision and Recall. It is particularly valuable when the classes are imbalanced and one class is significantly rarer than the other. It provides a single measure that accounts for both false positives and false negatives, making it a good indicator of the model’s overall effectiveness in identifying positive instances without being biased by the majority class38.

Accuracy is the ratio of correctly predicted observations to total observations.

where \(\text {TN}\) is True Negatives. Accuracy is a straightforward metric that provides an overall view of the model’s performance. However, it can be misleading in cases of class imbalance. For example, if 95% of the data belongs to one class, a model that predicts the majority class all the time will have high accuracy but poor performance in terms of Precision, Recall, and F1 Score for the minority class. Thus, while accuracy gives a general performance measure, it should be considered alongside the other metrics to get a full picture of model performance39.

Using these four metrics together provides a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s performance, ensuring it performs well not only overall but also across different aspects of classification performance.

To assess human diagnostic performance, evaluators’ responses were analyzed to calculate true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives for each diagnostic category. Confusion matrices were constructed to visualize the distribution of predictions across actual categories, providing insights into patterns of correct and incorrect diagnoses. The matrices highlighted areas where human evaluators struggled most, particularly when differentiating eczema from psoriasis or distinguishing dermatophytosis from other conditions. Statistical p-values were calculated using two-proportion tests to evaluate whether differences in diagnostic accuracy between evaluator groups—including interns and internists—were significant.

In parallel, the diagnostic performance of the deep learning model was evaluated using the same test dataset. A confusion matrix was generated to compare its predictions with the ground truth labels. The deep learning model’s confusion matrix was directly compared with those of interns and internists to identify areas where the AI showed superior or inferior performance relative to human evaluators. Key performance metrics including overall accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score were derived from all confusion matrices. One-proportion tests were applied to assess statistically significant differences between AI and human performance across these key diagnostic metrics.

All statistical analyses were conducted using MedCalc Statistical Software, version 22.013 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium) and IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Statistics, version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Performance of deep learning models in diagnosing skin lesions from images

To identify the CNN and Transformer architectures that performs best for skin lesion classification in skin images. Table 2 presented the main parameters of sixteen models, which were considered during the selection process. Batch Size represents the number of training examples used in a single iteration. The Loss Function measures the error in the model’s predictions. The Optimizer is the algorithm used to update the model’s weights. Learning Rate indicates the step size during each iteration, as the model seeks to minimize the loss function. Parameters refer to the total number of learnable parameters in the model. Finally, Giga Floating Point Operations per second (GFLOPs) reflect the computational complexity of the model. All models in the comparison use a batch size of 4, ensuring a fair and consistent training process. They all employ the cross-entropy loss function and the stochastic gradient descent optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001. This consistency allows for a direct comparison of their inherent capabilities without variability in the training setup. We used the k-fold cross-validation technique to avoid overfitting and random split bias. We set k to 5.

Table 3 presents the performance comparison of CNN and Transformer-based architectures on both training and validation datasets for the classification of dermatophytosis, eczema, and psoriasis. The table includes precision, recall, F1-score, and accuracy values for each class, as well as the overall classification performance of each model. To make the results easier to follow, the models were grouped into three categories based on validation accuracy: high-performing models (accuracy\(\ge\)0.900), moderate-performing models (accuracy between 0.800 and 0.899), and low-performing models (accuracy<0.800). The high-performance group comprised ten models—VGG19, SqueezeNet, ResNet-50, MobileNetV3, EfficientNetV2, ViT, Swin, DaViT, MaxViT, and GC ViT—all of which achieved an accuracy of 0.900 or higher. This group included both advanced CNNs and most Transformer-based architectures. Their strong performance highlights the ability of these models to capture complex visual features from macroscopic skin images. Among them, Swin and ViT achieved the highest accuracy scores, demonstrating the growing effectiveness of Transformer-based models in medical image classification. Specifically, Swin and ViT achieved F1 scores above 0.82 for dermatophytosis, 0.87 for eczema, and 0.97 for psoriasis, reflecting their consistent and robust performance across all target classes. The moderate-performance group included five models: AlexNet, GoogLeNet, DenseNet-121, CvT, and FastViT-S12. With accuracies ranging from 0.800 to 0.899, these models achieved acceptable performance but fell short of the top-performing architectures. Although relatively efficient in terms of computational cost, they may have limited ability to capture the subtle and complex visual patterns necessary for distinguishing between clinically similar conditions, particularly dermatophytosis and eczema. The low-performance group contained only one model, SHViT-S1, which achieved an accuracy of 0.777. Its relatively poor performance suggests that the model’s design may not be well suited to this classification task.

Table 4 presents the test set performance of CNN and Transformer-based models, confirming the trends observed during validation (Table 3). Overall, most models demonstrated consistent generalization, with top-performing architectures retaining high accuracy and F1 scores across all classes. Swin and ViT, which achieved the highest validation accuracy in Table 3, remained the best-performing models on the test set, both achieving perfect or near-perfect scores for psoriasis (F1 = 1.000) and high F1 scores for dermatophytosis and eczema. Their overall test accuracies were 0.967 and 0.960, respectively, demonstrating stable performance when applied to unseen data.

Among the evaluated models, the Swin has a parameter count of 86.74 million and requires 21.10 GFLOPs, placing it among the more resource-intensive models in the comparison. When compared with other Transformer-based models, Swin demonstrates a balanced trade-off between model size and computational demand. For instance, DaViT and GC ViT have slightly higher parameter counts (86.93 M and 89.29 M, respectively), yet require more computation (30.56 and 27.78 GFLOPs). Similarly, ViT has a comparable parameter count (85.80 M) but consumes more computational resources (24.04 GFLOPs), suggesting that Swin is relatively more efficient in terms of design. On the other hand, lightweight Transformers such as CvT, MaxViT, FastViT-S12, and SHViT-S1 operate with fewer than 20 million parameters and under 10 GFLOPs, making them more suitable for environments with limited computational capacity—though typically with some compromise in performance. Compared to CNN models, Swin requires higher resource consumption than compact architectures like SqueezeNet (0.73 M, 1.47 GFLOPs), MobileNetV3 (1.52 M, 0.11 GFLOPs), and GoogLeNet (5.60 M, 3.00 GFLOPs), but this is offset by its stronger classification performance in complex tasks such as skin disease recognition.

Figure 4 presents confusion matrices for all CNN and Transformer-based models evaluated on the test dataset for three-class skin condition classification. The color intensity in each cell represents the proportion of predictions, with darker shades indicating higher frequencies. These matrices visualize both correct predictions (diagonal elements) and misclassification patterns, providing insights into each model’s classification behavior. The visualizations were generated using predictions from the best-performing fold, representing the highest-performing results of each model during evaluation.

The analysis reveals notable performance differences across architectures. The Swin shows a perfectly diagonal matrix, meaning all test cases were correctly classified with no misidentifications. This suggests Swin is highly effective at distinguishing between challenging skin conditions—particularly between dermatophytosis and eczema, which are frequently misclassified by both deep learning models and human observers. In contrast, several CNN architectures exhibited varying degrees of classification confusion. AlexNet and GoogLeNet showed substantial misclassification between dermatophytosis and eczema categories, while more recent architectures like EfficientNetV2, MobileNetV3, and ResNet-50 demonstrated improved but imperfect performance with occasional classification errors. Among other Transformer models, ViT, DaViT, and GC ViT generally performed well but still showed some confusion between eczema and dermatophytosis classes. Notably, only the Swin achieved perfect separation across all three diagnostic categories, highlighting its superior ability to capture subtle visual distinctions in clinical skin images. As illustrated in Figure 4, the Swin achieved perfect diagonal separation across all diagnostic classes, with no misclassifications observed. By contrast, several CNN and Transformer models demonstrated residual confusion, particularly between eczema and dermatophytosis. To complement these results, Figure 11 depicts the confusion matrix of physician responses, showing frequent misclassification of eczema as psoriasis or dermatophytosis. Taken together with Figure 4, which demonstrates perfect diagonal separation by the Swin, these findings underscore the contrast between AI and human evaluators, while the model consistently achieved flawless classification across all categories, physicians which include both interns and internists struggled most with eczema, often confusing it with other erythematous conditions. This pictorial comparison highlights not only the superior accuracy of the Swin but also its potential to address recurrent diagnostic blind spots in clinical practice. This visual comparison underscores the robustness of the Swin relative to both other architectures and human evaluators. Although Swin and ViT have comparable parameter counts (86.74M vs. 85.80M, respectively), Swin consistently outperformed ViT across all evaluation metrics (Tables 3, 4). This performance gap can be attributed to Swin’s architectural innovations, particularly its shifted window self-attention mechanism and hierarchical feature representation. While ViT applies global self-attention at a single resolution, Swin introduces local window-based attention with overlapping regions through shifting windows, which enables efficient modeling of both local and long-range dependencies. Furthermore, Swin’s hierarchical design—progressively merging patches across layers—allows the model to capture multiscale contextual features that are crucial in dermatological imaging, where lesions often exhibit fine-grained textures and spatial variability. This design not only improves computational efficiency but also enhances the model’s ability to focus on clinically meaningful regions, leading to improved classification performance across all skin disease categories in our study. This result supports previous findings (Tables 3, 4), where Swin achieved the highest F1 scores and accuracy, further confirming its robustness and precision in clinical image-based skin disease classification.

As mentioned above, we can conclude that the Swin consistently outperformed all other models across multiple evaluation metrics. It achieved the highest test accuracy of 0.967 with strong F1 scores for all three conditions (Tables 3, 4). Most importantly, Figure 4 shows that Swin was the only model to achieve perfect classification with zero misclassifications, successfully distinguishing between the visually similar dermatophytosis and eczema conditions that challenge other models. While Swin requires moderate computational resources (86.74M parameters, 21.10 GFLOPs), it is more efficient than comparable Transformers like ViT and DaViT (Table 2). This demonstrates Swin’s suitability for skin lesion classification tasks.

Clinical interpretation and evaluation of Grad-CAM outputs

Purpose and interpretability of Grad-CAM

Grad-CAM is a widely used method for visualising which regions of an input image influence a model’s prediction. In medical applications—where accountability and transparency are critical—such spatial attention visualisations offer an interpretability layer that bridges deep learning outputs with clinician intuition. By tracing the internal reasoning process of convolutional and Transformer-based models, Grad-CAM provides insight not just into what was predicted, but why. In dermatology, where lesion localisation is diagnostic, Grad-CAM is particularly valuable in assessing whether a model’s prediction is rooted in clinically meaningful regions. This contextual interpretability is crucial for building trust in AI-assisted skin disease classification.

Observed attention patterns across model families

Figures 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 display Grad-CAM visualisations for 16 models (eight CNN-based and eight Transformer-based) across three skin disease categories: dermatophytosis, eczema, and psoriasis. These heatmaps show distinct patterns of spatial attention between architectural families. Among CNN-based models, architectures such as AlexNet, GoogLeNet, DenseNet-121, and SqueezeNet were more prone to misclassification. Their Grad-CAM visualizations often revealed attention directed toward irrelevant background or unaffected skin regions—especially in conditions like dermatophytosis and eczema—suggesting a tendency to rely on artefactual or contextual cues. Correct classifications in CNNs were generally associated with narrowly focused red highlights on a portion of the lesion, whereas incorrect predictions frequently occurred when lesion areas were neglected or highlighted in cooler colours. By contrast, Transformer-based models generally demonstrated stronger alignment with clinically meaningful regions. Swin and ViT, in particular, consistently generated accurate predictions with heatmaps focused squarely on lesion zones. Grad-CAM visualizations with clinical annotations further illustrate this alignment, highlighting hallmark diagnostic cues such as silvery scales in psoriasis, diffuse erythema in eczema, and the raised peripheral rim with central clearing in dermatophytosis. These annotated comparisons reinforce that the highlighted regions correspond to features routinely used by clinicians in diagnostic reasoning. Swin maintained precise attention on pathologic areas across all three disease categories. Other Transformer models—such as DaViT, MaxViT, and GC ViT—also showed reliable localisation but occasionally included surrounding non-lesional skin within their focus. Across the board, correct predictions were associated with red-highlighted lesion centres, while failures typically involved dispersed or misplaced focus. These findings underscore the critical role of spatial attention in dermatologic AI classification.

To move beyond architectural trends, we further examined how these attention patterns aligned with clinical reasoning through structured expert review.

Clinical review of Grad-CAM outputs

To assess the clinical plausibility of the Grad-CAM visualisations, two board-certified dermatologists (C.W. and C.C.) jointly reviewed a representative subset of Grad-CAM heat-maps through a structured discussion. The reviewers assessed whether attention maps corresponded to key diagnostic features for psoriasis, eczema, and dermatophytosis, and whether the visual patterns aligned with real-world clinical reasoning.

Overall, CNN models tended to produce narrower, more localized attention focused on high-contrast features such as silvery scales or annular borders. These maps were generally easier to interpret but occasionally failed to capture the full lesion extent, particularly for diffuse conditions like eczema. In contrast, Transformer models demonstrated broader spatial coverage and were more likely to capture composite lesion patterns, such as both peripheral rim and central clearing in dermatophytosis. However, this breadth sometimes came at the expense of specificity, with occasional attention spillover into non-lesional skin or background artefacts.

The reviewers concluded that while CNN models are often more intuitive, Transformer models better mimic holistic diagnostic strategies used in practice. A structured summary of these observations across all disease categories and model types is provided in Table 5.

Performance of novices and experienced non-dermatologists in diagnosing skin lesions from images

Among non-dermatologist physicians, internists demonstrated moderately higher diagnostic performance than interns across all disease categories (see Supplementary Table S1, Figure 11). While both groups showed similar trends in misclassification patterns, internists achieved higher recall and F1 scores in eczema and dermatophytosis, likely reflecting their broader clinical experience.

Comparing the performance results between nondermatologists and the deep learning model in classifying the skin diseases

Table 6 presents a performance comparison between 30 physicians (comprising interns and internists) and the Swin model in diagnosing dermatophytosis, eczema, and psoriasis from clinical images. Across all disease categories, Swin consistently outperformed human evaluators in precisions, recall and F1 score. Differences between AI and human performance were statistically significant for nearly all metrics (all p < 0.001), except for dermatophytosis precision (p = 0.467). Notably, the largest performance gap was observed in recall for psoriasis (Swin: 1.000 vs. physicians: 0.716; p < 0.001; 95% CI: 0.722 to 0.974).

For dermatophytosis, the Swin outperformed physicians across all evaluation metrics, achieving a recall (0.980), precision (0.925), and F1 score (0.951). In comparison, physicians attained a recall (0.737), precision (0.890), and F1 score (0.774).

In the classification of eczema, the Swin demonstrated superior performance, achieving higher precision (0.980), recall (0.920), and F1 score (0.948). In contrast, physicians recorded lower scores across all metrics, with a precision of 0.864, recall of 0.694, and F1 score of 0.843.

For psoriasis, Swin obtained perfect scores in all three metrics including precision, recall, and F1 score (1.000 each). Physicians demonstrated lower performance, with a precision of 0.877, recall of 0.716, and F1 score of 0.807.

When evaluating overall classification performance across all classes, Swin again outperformed human physicians, achieving a precision of 0.968, recall of 0.967, F1 score of 0.967, and overall accuracy of 0.967. In comparison, physicians achieved 0.801 precision, 0.800 recall, 0.800 F1 score, and 0.867 accuracy.

Discussion

The results of this study underscore the considerable promise of transformer-based architectures, particularly the hierarchical Swin, as diagnostic tools for dermatological conditions such as psoriasis, dermatophytosis, and eczema. In our experiments, Swin consistently outperformed every comparator model and the physician cohort across precision, recall, and F1 metrics. These findings corroborate a growing body of evidence: Mohan et al. reported that a Swin-based pipeline achieved a macro-F1 of 0.95 and 93 % accuracy on a 31-class skin-disease dataset, clearly surpassing CNN baselines40, a recent systematic review likewise concluded that vision-transformer families set the current state of the art in cutaneous-image recognition41 and a conference study that applied Swin to 24 skin conditions documented\(>5\) % accuracy gains over ResNet-50 and EfficientNet benchmarks42. Collectively, these lines of evidence position hierarchical vision transformers as leading candidates for real-world dermatological decision support and justify further prospective clinical validation.

Beyond architecture design, the integration of meta-heuristic optimization algorithms with deep learning models has shown significant promise in a variety of medical-imaging tasks. Saber et al.43 employed a hybrid ensemble framework that combined deep networks with meta-heuristic algorithms for breast-tumor classification, achieving notable improvements in diagnostic accuracy. Elbedwehy et al.44 likewise incorporated advanced optimization strategies with neural networks to enhance kidney-disease detection, underscoring the value of feature selection and hyper-parameter tuning. Khaled et al.45 further demonstrated that coupling adaptive CNNs with the grey-wolf optimizer boosted breast-cancer diagnostic performance. Taken together, these studies suggest that optimization-driven enhancements could further strengthen models like Swin in future dermatologic applications.

Moreover, Swin also outperformed non-dermatologists which are interns and internists, across key metrics like diagnostic precision, recall, F1 scores, and overall accuracy. This performance demonstrates its ability to bridge gaps in clinical expertise, particularly for complex and variable conditions like eczema.

An important characteristic of advanced Transformer and CNN models, such as Swin, can be observed through the use of Grad-CAM, which provides insights into the regions of an image that the model prioritizes for its predictions. Annotated Grad-CAM visualizations explicitly mark clinically meaningful features as confirmed by expert dermatologists, demonstrating that the model’s attention is not arbitrary but grounded in features fundamental to diagnosis. This alignment with clinical reasoning strengthens clinician trust and supports integration of such models into medical education and teledermatology workflows. Apart from accurately identifying lesioned areas, the model’s predictions align closely with clinical reasoning principles taught in medical education. For instance, in cases of dermatophytosis, clinical training emphasizes recognizing a central clearing with an active, raised border. Grad-CAM visualizations from Swin effectively focus on these diagnostic features. For eczema, the attention maps highlight diffuse and inflamed patches, consistent with the condition’s varied presentations and clinical complexity. For psoriasis, the Grad-CAM emphasize well-demarcated plaques with scaling, features that are central to its clinical identification. These observed attentions mimicked the reasoning patterns used by human experts. The insights provide a clear and interpretable basis for the model’s predictions while ensuring consistency with established clinical practices.

The diagnostic superiority of Swin can be attributed to its extensive and diverse training dataset of 2,940 images, enabling it to capture subtle distinctions between dermatological conditions. While the combined dataset used in this study included images from both public sources (e.g., DermNet) and Thai patients, we did not conduct a formal ablation analysis to isolate the impact of dataset origin on model performance. Informal observations during model development indicated that networks trained solely on lighter-skinned datasets (e.g., DermNet) yielded reduced accuracy on images from Thai patients, particularly in conditions such as eczema, where erythema presents less prominently. This underscores the need for training datasets that reflect a diversity of skin tones and lesion morphologies to ensure generalizability. In contrast, non-dermatologists, whose clinical training primarily involves history taking and physical examination, were limited in this study to interpreting photographic images without access to contextual patient histories or additional diagnostic tools. This reliance on static images highlights the advantage of data-driven deep learning models in standardizing and enhancing diagnostic accuracy. Similar insights were reported in a study by Liu et al., which demonstrated that a deep learning system achieved diagnostic accuracy comparable to dermatologists and surpassed that of primary care physicians and nurse practitioners in classifying skin conditions46. Additionally, a study by Venkatesh et al., found that deep learning models exhibited higher diagnostic accuracy than non-dermatologists in dermatology, further supporting the collaborative potential of AI in clinical workflows47.

While internists outperformed interns, reflecting the value of clinical experience, their diagnostic accuracy remained below that of Swin, particularly for conditions with complex presentations like eczema. This discrepancy highlights the need for structured dermatology training to ensure high diagnostic accuracy.

The prevalence of dermatophytosis (20–25%) and eczema (up to 20%) compared to psoriasis (1–10%) may influence diagnostic familiarity among non-dermatologists in real-world settings1,48. Despite this, eczema remains the most challenging condition for non-dermatologists due to its varied clinical presentations.

From the confusion matrix, interns show considerable difficulty in diagnosing eczema, with 22% of eczema cases being misclassified as dermatophytosis and 10% as psoriasis. While interns perform relatively well in identifying psoriasis (\(85\%\)) and dermatophytosis (\(81\%\)), the clinical variability of eczema introduces significant errors. In contrast, internists demonstrate improved diagnostic accuracy, with 71% correct predictions for eczema, though 20% of eczema cases are still misclassified as psoriasis. The challenges with eczema persist even for experienced internists, highlighting its complexity in clinical practice. Figure 11 shows the confusion matrix for novices and experts in diagnosing three skin diseases)

The ability of Swin to consistently outperform non-dermatologists across all conditions, supported by Grad-CAM visualizations that enhance interpretability, underscores its potential as a transformative tool in dermatology. These visualizations enhance clinician trust and facilitate AI integration into clinical workflows. Furthermore, the challenges highlighted in this study, including reliance on photographic data and limited contextual information, advocate for integrating deep learning models into dermatological training to complement clinical expertise and improve patient outcomes. To translate these findings into practical deployment, the Swin could serve as a triage or decision-support tool in telemedicine,assisting primary care providers in identifying high-risk cases or confirming suspected diagnoses. For real-world deployment, model explainability, clinician oversight, and medicolegal frameworks are essential to ensure safety and accountability. Clear governance protocols and human-in-the-loop safeguards should be established to address diagnostic liability and maintain clinician trust. These elements will be critical for transitioning AI systems like the Swin from research to clinical implementation. These steps are essential to move from proof-of-concept to reliable and safe adoption in everyday practice. In real-world workflows, the Swin’s interpretability via Grad-CAM could be integrated as a visual overlay during telemedicine consultations or electronic health record systems, allowing physicians to cross-check AI focus with clinical features. Such interpretability not only enhances clinician trust but also provides educational value for trainees. To ensure patient safety, a human-in-the-loop framework is envisioned, where ambiguous or low-confidence cases trigger clinician review, and user feedback on AI-assisted decisions is collected to iteratively refine the model’s deployment. The model’s robustness and interpretability make it an appealing candidate for deployment in general practice and telemedicine workflows. However, the current study did not evaluate performance under real-world telemedicine conditions, such as uncontrolled lighting, motion blur, or low-resolution images from patient-owned devices. These variables may impact classification reliability and should be investigated in prospective validation. Additionally, the evaluation of human performance was conducted as a pilot study using 30 clinical images assessed by 30 non-dermatologist participants. While this design allowed for a direct comparison with the deep learning models, its limited sample size may restrict statistical power and reduce the generalizability of findings. The human–AI comparison in this study was intentionally designed as a pilot, using 30 clinical images and 30 non-dermatologist participants. While this design allowed for a controlled, qualitative benchmark, its limited scale reduces statistical power and restricts the generalizability of conclusions. Therefore, these findings should be considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating rather than definitive. To address this limitation, future research will incorporate larger sample sizes, a broader range of evaluator expertise, and more heterogeneous image sets to strengthen the reliability and applicability of comparative analyses.

By incorporating findings from comparative studies, this discussion underscores the potential of Swin and similar deep learning models to enhance diagnostic workflows in dermatology while addressing existing challenges in clinical and AI integration

Strengths and limitations

This study offers several notable strengths. First, it utilized a diverse dataset drawn from a public source, DermNet9 and a local Thai clinical dataset. This diversity enhances the model’s generalizability and ensures representation across a wide range of dermatologic conditions. Second, the inclusion of Asian patients, who generally have darker skin types than Caucasians1, increases the relevance of our findings for populations that are often underrepresented in dermatologic AI studies. Third, all clinical images were captured using various smartphone models under realistic conditions, reflecting the quality and variability typical of teledermatology environments. Lastly, model interpretability was addressed using Grad-CAM, which demonstrated that the model consistently attended to clinically meaningful regions, providing transparency that may enhance clinician trust and educational utility. Nevertheless, this study has limitations. Differences in skin pigmentation can alter the visual characteristics of dermatologic lesions49, and both deep learning models and physicians have shown reduced diagnostic accuracy in darker-skinned populations50. Additionally, to comply with the Thai Personal Data Protection Act, we excluded lesions from the face, neck, and groin. While this approach was necessary for ethical and legal compliance, it restricts the generalizability of our model to clinically important areas, such as inverse psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and intertriginous eczema51. These anatomical sites often pose diagnostic challenges due to overlapping morphologies, and their exclusion represents a meaningful limitation of this work. Future studies should aim to incorporate such regions through carefully designed, privacy-compliant protocols to enhance applicability in real-world practice. The human-AI comparison was conducted as a pilot study with 30 clinical images reviewed by 30 non-dermatologists. While this design provided an initial benchmark, the limited sample size reduces statistical power and generalizability. Additionally, the study did not evaluate medicolegal risks associated with AI misdiagnosis or the operational implications of deploying such models in clinical practice. This study did not evaluate performance under real-world telemedicine conditions, such as uncontrolled lighting, motion blur, or low-resolution images from patient-owned devices. Device variability, including differences in smartphone models, camera quality, and ambient lighting, can substantially affect image appearance and diagnostic reliability. These factors limit direct applicability of our results to telemedicine environments, underscoring the need for future validation under uncontrolled, real-world imaging conditions.

Future research should include larger, more diverse clinician cohorts and broader anatomical coverage, validated under real-world telemedicine conditions. Moreover, efforts should be made to stratify performance across skin phototypes and establish clinical oversight frameworks for safe AI deployment, including mechanisms to flag uncertain or ambiguous cases. These steps are essential to ensure both the scalability and safety of AI-assisted dermatologic diagnosis in routine care.

Conclusions

This study developed a deep learning framework leveraging CNN and Transformer architectures to classify dermatophytosis, psoriasis, and eczema. Swin outperformed all models, demonstrating the highest accuracy and F1 scores, minimal misclassification, and interpretable predictions via Grad-CAM, enhancing its clinical applicability.

Swin also surpassed non-dermatologists in diagnostic performance, particularly for challenging conditions like eczema, highlighting its potential as a diagnostic aid in primary care and telemedicine. The model’s robustness across diverse datasets, including Thai skin phototypes, underscores its suitability for varied populations, though its exclusion of facial, neck, and groin lesions limits generalizability.

These findings support integrating AI tools like the Swin Transformer into clinical practice to enhance diagnostic accuracy and educate non-specialists. Further large-scale validation across diverse populations is warranted.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Kimball, A. B. Skin differences, needs, and disorders across global populations. In Journal of Investigative Dermatology Symposium Proceedings 13, 2–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/jidsymp.2008.5 (2008).

Egeberg, A., Griffiths, C., Williams, H., Andersen, Y. & Thyssen, J. Clinical characteristics, symptoms and burden of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis in adults. Br. J. Dermatol. 183, 128–138 (2020).

Chong, M. & Fonacier, L. Treatment of eczema: Corticosteroids and beyond. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 51, 249–262 (2016).

Gnat, S., Łagowski, D. & Nowakiewicz, A. Major challenges and perspectives in the diagnostics and treatment of dermatophyte infections. J. Appl. Microbiol. 129, 212–232 (2020).

Gottlieb, A. B. & Dann, F. Comorbidities in patients with psoriasis. Am. J. Med. 122, 1150-e1 (2009).

Basarab, T., Munn, S. & Jones, R. R. Diagnostic accuracy and appropriateness of general practitioner referrals to a dermatology out-patient clinic. Br. J. Dermatol. 135, 70–73 (1996).

Liu, Z., Wang, X., Ma, Y., Lin, Y. & Wang, G. Artificial intelligence in psoriasis: Where we are and where we are going. Exp. Dermatol. 32, 1884–1899 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Recent advancements and perspectives in the diagnosis of skin diseases using machine learning and deep learning: A review. Diagnostics 13, 3506 (2023).

Hammad, M., Pławiak, P., ElAffendi, M., El-Latif, A. A. A. & Latif, A. A. A. Enhanced deep learning approach for accurate eczema and psoriasis skin detection. Sensors 23, 7295 (2023).

Krakowski, I. et al. Human-ai interaction in skin cancer diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. NPJ Digit. Med. 7, 78 (2024).

Hameed, N., Shabut, A. M., Ghosh, M. K. & Hossain, M. A. Multi-class multi-level classification algorithm for skin lesions classification using machine learning techniques. Expert Syst. Appl. 141, 112961 (2020).

Huang, K. et al. The classification of six common skin diseases based on xiangya-derm: Development of a chinese database for artificial intelligence. J. Med. Internet Res. 23, e26025 (2021).

Eskandari, A. & Sharbatdar, M. Efficient diagnosis of psoriasis and lichen planus cutaneous diseases using deep learning approach. Sci. Rep. 14, 9715 (2024).

Wu, H. et al. A deep learning, image based approach for automated diagnosis for inflammatory skin diseases. Ann. Transl. Med. 8, 581 (2020).

Hammad, M., Plawiak, P., ElAffendi, M., El-Latif, A. A. A. & Latif, A. A. A. Enhanced deep learning approach for accurate eczema and psoriasis skin detection. Sensors https://doi.org/10.3390/s23167295 (2023).

Dumoulin, V. & Visin, F. A guide to convolution arithmetic for deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.07285 (2016).

Taylor, L. & Nitschke, G. Improving deep learning using generic data augmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1708.06020 (2017).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 6105–6114 (PMLR, 2019).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst.25 (2012).

Krizhevsky, A. One weird trick for parallelizing convolutional neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1404.5997 (2014).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 4700–4708 (2017).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. Efficientnetv2: Smaller models and faster training. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 10096–10106 (PMLR, 2021).

Szegedy, C. et al. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 1–9 (2015).

Koonce, B. & Koonce, B.E. Convolutional neural networks with swift for tensorflow: Image recognition and dataset categorization (Springer, 2021).

Iandola, F.N. Squeezenet: Alexnet-level accuracy with 50x fewer parameters and\(<\) 0.5 mb model size. arXiv preprint arXiv:1602.07360 (2016).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556 (2014).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 770–778 (2016).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 10012–10022 (2021).

Wu, H. et al. Cvt: Introducing convolutions to vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 22–31 (2021).

Ding, M. et al. Davit: Dual attention vision transformers. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 74–92 (Springer, 2022).

Tu, Z. et al. Maxvit: Multi-axis vision transformer. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 459–479 (Springer, 2022).

Hatamizadeh, A., Yin, H., Heinrich, G., Kautz, J. & Molchanov, P. Global context vision transformers. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 12633–12646 (PMLR, 2023).

Vasu, P. K. A., Gabriel, J., Zhu, J., Tuzel, O. & Ranjan, A. Fastvit: A fast hybrid vision transformer using structural reparameterization. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 5785–5795 (2023).

Yun, S. & Ro, Y. Shvit: Single-head vision transformer with memory efficient macro design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 5756–5767 (2024).

Deng, J. et al. Imagenet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In 2009 IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 248–255 (IEEE, 2009).

Sokolova, M. & Lapalme, G. A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Inform. Process. Manage. 45, 427–437 (2009).

Chinchor, N.A. Muc-4 evaluation metrics. In Message Understanding Conference (1992).

Powers, D.M. Evaluation: from precision, recall and f-measure to roc, informedness, markedness and correlation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.16061 (2020).

Mohan, J. et al. Enhancing skin disease classification leveraging transformer-based deep learning architectures and explainable ai. Comput. Biol. Med. 190, 110007 (2025).

Adebiyi, A. et al. Transformers in skin lesion classification and diagnosis: A systematic review. medRxiv 09, 2024 (2024).

Ahmad, J., Farooq, M.U., Zafeer, F., Shahid, N. et al. Classification of 24 skin conditions using swin transformer: Leveraging dermnet & healthy skin dataset. In International Conference on Energy, Power, Environment, Control and Computing (ICEPECC 2025), vol. 2025, 511–519 (IET, 2025).

Saber, A., Elbedwehy, S., Awad, W. A. & Hassan, E. An optimized ensemble model based on meta-heuristic algorithms for effective detection and classification of breast tumors. Neural Comput. Appl. 37, 4881–4894 (2025).

Elbedwehy, S., Hassan, E., Saber, A. & Elmonier, R. Integrating neural networks with advanced optimization techniques for accurate kidney disease diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 14, 21740 (2024).

Alnowaiser, K., Saber, A., Hassan, E. & Awad, W. A. An optimized model based on adaptive convolutional neural network and grey wolf algorithm for breast cancer diagnosis. PLoS One 19, e0304868 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. A deep learning system for differential diagnosis of skin diseases. Nat. Med. 26, 900–908. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0842-3 (2020).

Venkatesh, K. P., Raza, M. M., Nickel, G., Wang, S. & Kvedar, J. C. Deep learning models across the range of skin disease. npj Dig. Med. 7, 32 (2024).

Chanyachailert, P., Leeyaphan, C. & Bunyaratavej, S. Cutaneous fungal infections caused by dermatophytes and non-dermatophytes: An updated comprehensive review of epidemiology, clinical presentations, and diagnostic testing. J. Fungi 9, 669 (2023).

Myers, J. Challenges of identifying eczema in darkly pigmented skin. Nurs. Child. Young People 27, 24–28. https://doi.org/10.7748/ncyp.27.6.24.e571 (2015).

Groh, M. et al. Deep learning-aided decision support for diagnosis of skin disease across skin tones. Nat. Med. 30, 573–583. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02728-3 (2024).

Micali, G. et al. Inverse psoriasis: From diagnosis to current treatment options. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 12, 953–959. https://doi.org/10.2147/CCID.S189000 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the patients who participated in this study; the clinicians who participated in the tests; Dr. Prapat Suriyaphol for his advice about the Personal Data Protection Act in Thailand, Dr. Irin Chaikangwan for her advice about deep learning, Ms. Nutwara Meannui for her assistance with data collection, and Dr. Chulaluk Komoltri for her advice with statistical analysis. This research project was supported by Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Grant Number (IO) R016633016.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT and Grammarly to improve readability and grammar. After using these tools, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the final content of the publication.

Funding

This research project was supported by Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Grant Number (IO) R016633016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.Y.: Conceptualization, acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, administrative, technical, or material support, supervision. C.W.: Conceptualization, acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, administrative, technical, or material support, supervision. T.T.: Conceptualization, Acquisition of data, Data analysis and interpretation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing ,administrative, technical, or material support, Supervision. L.C.: Conceptualization, acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, Writing—Original Draft, administrative, technical, or material support. N.S.: Conceptualization, acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, Writing—Original Draft, administrative, technical, or material support. C.C.: Conceptualization, acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, Writing—Original Draft, administrative, technical, or material support. S.B.: Conceptualization, acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data. T.N.: Conceptualization, acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data. T.P.: Conceptualization, acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data. T.H.: Acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data. P.W.: Acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data. P.K.: Acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data. S.A.: Conceptualization, Acquisition of data, Data Analysis and Interpretation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision P.C.: Conceptualization, acquisition of data, analysis or interpretation of data, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, administrative, supervision. administrative, technical, or material support.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yodrabum, N., Wongpraparut, C., Titijaroonroj, T. et al. Comparative performance of deep learning models and non-dermatologists in diagnosing psoriasis, dermatophytosis, and eczema. Sci Rep 16, 245 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29562-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29562-6