Abstract

This study aims to explore the mechanism by which KAL inhibits the proliferation and migration of cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) cells through the downregulation of miR-21, thereby modulating the PTEN/AKT signaling pathway. Cholangiocarcinoma cell lines HUCCT1 and RBE were cultured and transfected with KAL overexpression plasmids or miR-21 mimics. Transfection efficiency was validated by Western blot. Cell viability was assessed using the CCK8 assay, apoptosis levels were analyzed via flow cytometry, and cell invasion capability was evaluated through Transwell assays. PIP3 levels were measured using ELISA. Western blot was used to detect the expression levels of PTEN, AKT/mTOR signaling pathway proteins, and apoptosis-related proteins, including BCL-2 and Cleaved-Caspase3. Dual-luciferase reporter assays were performed to confirm the interaction between PTEN and miR-21-5p. Based on in vitro experimental results, HUCCT1 cells were selected for in vivo tumorigenicity experiments to assess the effects of KAL overexpression lentivirus on CCA tumor growth. Tumor size, volume, and weight were measured, and immunohistochemistry was used to detect the positive expression levels of KI67, PTEN, BCL-2, and Cleaved-Caspase3 in tumor tissues. PCR and Western blot analyses confirmed the effective transfection of KAL overexpression into HUCCT1 and RBE cells. Overexpression of KAL significantly inhibited CCA cell proliferation and invasion, reduced PIP3 production, suppressed the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, and promoted apoptosis. PCR results demonstrated that miR-21 mimic transfection into HUCCT1 and RBE cells was successful. Overexpression of miR-21 reversed the inhibitory effects of KAL on CCA cell proliferation and migration, as well as the pro-apoptotic effects of KAL. Additionally, miR-21 suppressed the KAL-induced upregulation of PTEN and Cleaved-Caspase3 and promoted BCL-2 expression. Dual-luciferase reporter assays confirmed a targeted interaction between PTEN and miR-21-5p. In vivo tumorigenicity experiments showed that KAL overexpression significantly inhibited tumorigenesis in CCA cells. Tumor tissues from the KAL overexpression group exhibited significantly increased expression levels of Cleaved-Caspase3 and PTEN and decreased positive expression levels of KI67 and BCL-2, indicating suppressed proliferation and enhanced apoptosis in CCA cells. Overexpression of KAL inhibits CCA cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis. Overexpression of miR-21 reverses the effects of KAL on CCA cells, suggesting that KAL suppresses CCA growth through miR-21-mediated modulation of the PTEN/AKT signaling pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biliary tract cancer (BTC) is the second most common malignancy of the hepatobiliary system after hepatocellular carcinoma. BTC includes gallbladder cancer and cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), which is further classified into intrahepatic CCA (iCCA), perihilar CCA (pCCA), and distal CCA (dCCA) based on anatomical location1. China has the highest incidence of CCA globally, approximately 40 times higher than in Western countries2. Early clinical features of CCA are often nonspecific, making diagnosis difficult. More than 65% of patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage, losing the opportunity for curative surgical resection3. Consequently, the 5-year survival rate for CCA patients is extremely low, below 10%4. Even among patients eligible for surgical treatment, the high recurrence rate due to vascular, lymphatic, and neural invasion, distant metastases, and resistance to adjuvant therapies limits the 5-year survival rate to less than 10%5. Surgical resection remains the primary potentially curative treatment for CCA. For early-stage perihilar CCA, liver transplantation following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy may be an option. For advanced or unresectable cases, radiotherapy, localized therapies, and systemic chemotherapy are the main treatment modalities6. Imaging modalities for CCA diagnosis primarily include magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and computed tomography (CT)7. Beyond established risk factors, recent research has increasingly explored the roles of viral and metabolic factors in CCA pathogenesis8. Due to nonspecific early symptoms, a lack of reliable molecular biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis prediction, and chemotherapy resistance, the overall incidence of CCA has been increasing9. Understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms of CCA and identifying critical molecules involved in its progression is essential for discovering new diagnostic markers and developing novel therapeutic targets.

The KAL protein, also known as anosmin-1, is an extracellular matrix protein active during embryonic development10. It plays crucial roles in various embryonic systems, including the respiratory tract, kidneys, digestive system, and specific brain regions11. KAL protein is involved in neuronal migration and axonal growth and regulates neural cell interactions. In the developing brain, KAL facilitates the growth and migration of olfactory neurons, which migrate from the developing nasal area to the olfactory bulb in the brain’s anterior region, a process essential for olfactory perception12. Additionally, KAL protein contributes to the migration of neurons producing gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), a hormone crucial for prenatal and pubertal sexual development. GnRH is essential for normal ovarian and testicular function in females and males, respectively13.

In malignancies, studies suggest a tumor-suppressive role for KAL. For instance, Liu et al. reported that KAL expression was significantly reduced in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) tissues compared to normal oral mucosa. Reduced KAL expression was associated with advanced clinical stages, lymph node metastasis, and poor prognosis, indicating its potential tumor-suppressive role in OSCC progression14. Tanaka et al. highlighted KAL as a candidate tumor suppressor gene in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), with its function potentially suppressed by promoter hypermethylation15. However, the role of KAL in CCA remains unclear. However, the direct molecular mechanisms of KAL in tumor initiation and progression remain unclear. Some studies suggest that the role of KAL in tumors may be mediated through the regulation of the FGFR1 signaling pathway16, while others propose that KAL may regulate the invasive ability of tumor cells by influencing epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)17. Although KAL plays important roles in other cancers, its effect on the growth and proliferation of CCA cells is still unknown.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of highly conserved small RNAs of approximately 23 nucleotides in length, widely involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and metabolism. They mainly function by binding to specific mRNAs to regulate gene expression18. The types and levels of miRNAs vary with physiological and pathological conditions, and significant differences in miRNA expression exist between cancer patients and healthy individuals. Therefore, miRNAs have potential as diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers19. miR-21 is a miRNA with critical regulatory roles in tumorigenesis and progression, and it is upregulated in various cancers such as lung cancer, gastric cancer, and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma20. In addition, studies have shown that miR-21 is highly expressed in CCA patients, and its expression correlates with disease stage and prognosis21. miR-21 promotes CCA cell proliferation and growth, and further research has revealed that this effect is mediated through inhibition of PTEN22. PTEN was the first identified tumor suppressor gene with phosphatase activity, and its expression is often downregulated in cancers. Loss of PTEN function has been shown to activate the PI3K/AKT pathway and promote tumor formation23. In CCA as well, blocking the interaction between PTEN and peroxiredoxin 1 results in PTEN oxidation and loss of phosphatase activity, leading to PI3K/AKT pathway activation and ultimately promoting CCA progression and metastasis24. Based on literature review, our research group hypothesizes that KAL may regulate miR-21, thereby affecting the PI3K/AKT pathway and influencing the progression of CCA. To validate this hypothesis, we designed the present study.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and treatments

The RBE cell line (CCA RBE, CL-0191) was purchased from Procell, and the HUCCT1 cell line (CCA HUCCT1, iCell-h316) was purchased from iCell. Both cell lines were cultured in 1640 complete medium containing 10% FBS and 1% P/S at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. For generating KAL-overexpressing CCA cells, adenoviral vectors containing KAL overexpression constructs (OE-KAL) or empty plasmids (OE-NC) as negative controls were transfected into RBE or HUCCT1 cells. Cells with 30–50% confluency were treated as follows: using 48-well plates, the medium was replaced with 1 mL of complete medium, followed by the addition of virus (MOI = 20) containing either OE-KAL or OE-NC. Polybrene (5 µg/mL) was added, and cells were incubated for 4–6 h. Complete medium was replenished to 1 mL. On the second day post-infection, the virus-containing medium was replaced with fresh complete medium, and the cells were cultured for 48 h before subsequent experiments.

For generating miR-21-overexpressing HUCCT1 cells, serum-free medium (1 mL) was used to replace the existing medium. Two sterile EP tubes were prepared, each containing 125 µL Opti-MEM. To one tube, 5 µL Lipofectamine 3000 was added, and to the other, 5 µL P3000 and 2.5 µg miR-21 mimic or mimic NC were added. After gentle mixing, the tubes were incubated at room temperature for 5 min. The contents of both tubes were combined, incubated for another 15 min at room temperature, and then added to the corresponding wells of a 6-well plate. Cells were incubated for 4 h, after which 1 mL of complete medium containing 20% serum was added. Experiments proceeded 48 h post-transfection.

Animal handling and procedures

Male BALB/C nude mice (4 weeks old) were obtained from Jiangsu Jicui Yaokang Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (SCXK(Su)2023-0009). Mice were housed at 20–26 °C with a humidity range of 40–70% under ad libitum feeding and water access. Log-phase CCA HUCCT1 cells were prepared as a single-cell suspension at a density of 1 × 10⁸ cells/mL. Mice were immobilized, and the right dorsal region was sterilized with iodine. A 1 mL syringe was used to inject 0.2 mL of the cell suspension subcutaneously into the dorsal region near the axilla. Following tumor growth to 80–100 mm³, mice were randomly assigned to different treatment groups and injected intratumorally with 50 µL of lentivirus (1 × 10⁸ TU) three times at 3-day intervals. Tumor dimensions were measured every 3 days to calculate tumor volume. At the experimental endpoint, intraperitoneal injection of 10 ml/kg of a mixture containing Zoletil (6 mg/ml) and Sumianxin II (1.7857 mg/ml) was administered to rapidly induce anesthesia in mice, ensuring that the animals did not experience pain during the procedure and maintaining a high level of safety. The tumors in mice were measured using a vernier caliper to determine the longest diameter (a) and the shortest diameter (b), and the tumor volume was calculated using the formula: a × b × b × 1/2. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Lentivirus construction

Based on the KAL (NM_000216.4) sequence, an overexpression sequence was designed. The target fragment was obtained by PCR amplification and recombined with the linearized VP-CMV-MCS-3flag-EF1-ZsGreen-T2A-PURO vector. After transformation into competent cells, bacterial colonies were identified by colony PCR and verified by sequencing. Upon successful sequencing, bacterial cultures were expanded, and high-purity, endotoxin-free plasmid DNA was extracted and purified. Using the Easyfectin transfection reagent, the lentiviral transfer plasmid carrying the target fragment, together with the packaging helper plasmids LV003-VSVG, LV003-REV, and LV003-GP, were co-transfected into 293T cells. Viral supernatants were collected at 48 h and 72 h post-transfection. High-titer lentiviral stocks were obtained by ultracentrifugation-based concentration and purification.

CCK8 assay

Cells with 80–90% confluency were seeded into 96-well plates after digestion with 0.25% trypsin (containing 0.02% EDTA) and centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 3 min. Cells were resuspended in medium and plated at a 1:3 ratio. Once adherent, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 100 µL per well. CCK8 reagent (10 µL) was added to each well, and cells were incubated for 2 h. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (WD-2012B, Beijing LiuYi).

Flow cytometry for apoptosis analysis

Cells (1 × 10⁶) were collected, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in 300 µL of precooled 1× Binding Buffer. Annexin V-FITC (5 µL) and PI (10 µL) were added, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature in the dark for 10 min. An additional 200 µL of precooled 1× Binding Buffer was added before analysis using a NovoCyte™ flow cytometer (NovoCyte 2060R).

Transwell invasion assay

Cells were digested, centrifuged, and resuspended in incomplete medium. A 24-well Transwell chamber was used, with 300 µL of cell suspension (1 × 10⁵ cells) added to the upper chamber and 600 µL of complete medium in the lower chamber. After 24 h, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 1 h, and photographed. Inner chamber cells were removed using cotton swabs. Stained cells were dissolved in 33% acetic acid, and 200 µL of the solution was measured at 562 nm using a microplate reader.

ELISA for PIP3 quantification

ELISA plates were equilibrated to room temperature, and standard or sample wells were prepared by adding 50 µL of standards or diluted samples (1:5 dilution). HRP-conjugated detection antibodies (50 µL) were added, and the plate was sealed and incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. After washing five times, 50 µL of Substrate A and 50 µL of Substrate B were added. The plate was incubated at 37 °C in the dark for 15 min, followed by the addition of 50 µL of Stop Solution. Optical density was measured at 450 nm within 15 min.

qPCR analysis

RNA was extracted using Trizon reagent (1 mL Trizon with 0.2 mL chloroform). miRNA was purified using a miRNA extraction kit (CW0627S, CWBIO), and concentration and purity were measured via UV spectrophotometry (OD260/OD280). cDNA was synthesized using a miRNA reverse transcription kit (MR101-02, Vazyme). qPCR was performed using a fluorescence-based PCR system (CFX Connect™, Bio-Rad) under the following conditions: pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s, for 40 cycles. U6 was used as an internal reference, and relative gene expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method. The primer sequences were listed in the Table 1.

Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested, and the culture medium was discarded. Total protein was extracted on ice using RIPA lysis buffer and centrifuged at 12,000 r/min at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was collected, and protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein quantification kit (E-BC-K318-M, Elabscience). Proteins were denatured and separated via SDS-PAGE for 1 h before being transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore). Membranes were blocked with 3% skim milk at room temperature for 1 h. Primary antibodies used included Mouse Anti-β-Actin (HC201, TransGen Biotech, 1/2000), Rabbit Anti-PTEN (22034-1-AP, Proteintech, 1/2000), Rabbit Anti-Cleaved-Caspase-3 (YC0006, Immunoway, 1/1000), Rabbit Anti-AKT (10176-2-AP, Proteintech, 1/1000), Rabbit Anti-P-AKT (AF0016, Affinity, 1/1000), Rabbit Anti-P-MTOR (AF3308, Affinity, 1/1000), Mouse Anti-MTOR (66888-1-Ig, Proteintech, 1/5000), and Rabbit Anti-BCL-2 (YM3041, Immunoway, 1/1000). Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The next day, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h. Secondary antibodies included HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) (GB23301, Servicebio, 1/2000) and HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (GB23303, Servicebio, 1/2000). PVDF membranes were treated with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent and visualized using an ultra-sensitive chemiluminescence imaging system (Tanon-5200, Shanghai Tanon Technology Co., Ltd.).

Immunohistochemistry

Tumor tissues from nude mice were sectioned, baked, deparaffinized, and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed using citrate buffer. Sections were blocked with 5% BSA and incubated with primary antibodies, including Ki67 (HA721115, HUABIO, 1/200), Bcl-2 (ET1720-53, HUABIO, 1/200), Cleaved-Caspase-3 (25128-1-AP, Proteintech, 1/200), and PTEN (22034-1-AP, Proteintech, 1/200), overnight at 4 °C. Secondary antibody incubation was performed using HRP-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (ZB-2301, ZSGB-Bio, 1:100). DAB chromogen (CW0125M, CWBIO) was applied, followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin (ZLI-9610, ZSGB-Bio). Sections were dehydrated, cleared, and mounted for observation under a microscope (CX43, Olympus).

Dual-luciferase assay

A dual-luciferase reporter vector was constructed. When cell confluence reached approximately 70%, transfection was initiated. Prior to transfection, the culture medium was replaced with serum-free medium. After 6 h of transfection, 0.5 mL of complete medium containing 20% serum was added to each well of a 12-well plate. According to the grouping described above, 293T cells were transfected, and fluorescence intensity was measured using a fluorescence spectrophotometer to verify whether miR-21-5p directly targets and binds to the PTEN gene.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 9.0 software was used for data visualization and statistical analysis. All experiments were repeated three times, and quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (X ± S). One-way ANOVA was used for multiple group comparisons, and T-tests were used for pairwise comparisons. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

KAL inhibits CCA cell proliferation, migration, and promotes apoptosis

First, the efficiency of KAL overexpression in HUCCT1 and RBE cells was validated through qPCR and Western blot analyses. As shown in Fig. 1A, KAL protein expression was significantly elevated in the KAL overexpression group compared to the Control and OE-NC groups, confirming the successful transfection of the KAL overexpression plasmid into HUCCT1 and RBE cells. Subsequently, cells transfected with empty vectors (OE-NC) or KAL overexpression vectors were subjected to CCK8 assays to assess cell proliferation, flow cytometry for apoptosis analysis, and Transwell assays for invasion capabilities. As shown in Fig. 1B; Table 2, the viability of HUCCT1 and RBE cells in the KAL overexpression group was significantly decreased compared with the normal control and empty vector groups. In addition, as shown in Fig. 1C; Table 2, the apoptosis levels of HUCCT1 and RBE cells were significantly increased in the KAL overexpression group compared with the control and empty vector groups. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 1D; Table 2, the invasion ability of HUCCT1 and RBE cells in the KAL overexpression group was significantly reduced compared with the control and empty vector groups. These results indicate that KAL can inhibit the proliferation and invasion of cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) cells while promoting their apoptosis.

KAL inhibits CCA cell proliferation and migration while promoting apoptosis. (A) Western blot validation of KAL overexpression plasmid transfection efficiency in HUCCT1 and RBE cells. (B) CCK8 assay measuring proliferation levels of HUCCT1 and RBE cells. (C) Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis levels in HUCCT1 and RBE cells. (D) Transwell assay evaluating the invasion capabilities of HUCCT1 and RBE cells (*P < 0.05 vs. Control; #P < 0.05 vs. OE-NC).

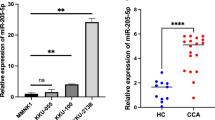

KAL downregulates miR-21-5p expression in CCA cells

The expression levels of miR-21-5p in CCA cells were assessed using qPCR. As shown in Fig. 2A and B, the expression of miR-21-5p was significantly reduced in the KAL overexpression group compared to the Control and OE-NC groups in both HUCCT1 and RBE cells. These results indicate that KAL overexpression effectively downregulates miR-21-5p expression.

KAL suppresses PIP3 production in CCA cells

The levels of PIP3 in HUCCT1 and RBE cells were measured using ELISA. As shown in Fig. 3, PIP3 levels were significantly reduced in the KAL overexpression group compared to the Control group. These results indicate that KAL overexpression effectively suppresses PIP3 production.

KAL inhibits PTEN/AKT pathway and modulates apoptosis-related protein expression in CCA cells

Western blot analysis was conducted to evaluate the expression levels of PTEN, AKT, p-AKT, MTOR, p-MTOR, Bcl-2, and Cleaved-Caspase3 in HUCCT1 and RBE cells. As shown in Fig. 4A and B, the expression ratios of p-AKT/AKT, p-MTOR/MTOR, and Bcl-2 were significantly reduced in the KAL overexpression group compared to the Control group. Conversely, PTEN and Cleaved-Caspase3 expression levels were significantly increased, with statistical significance. These results indicate that KAL overexpression suppresses AKT phosphorylation, inhibits the AKT signaling pathway, and promotes apoptosis in CCA cells.

KAL inhibits the AKT pathway and modulates apoptosis-related protein expression in CCA cells. (A) Western blot analysis of AKT pathway and apoptosis-related protein expression in HUCCT1 cells. (B) Western blot analysis of AKT pathway and apoptosis-related protein expression in RBE cells (n ≥ 3; *P < 0.05 vs. Control; #P < 0.05 vs. OE-NC).

Validation of the targeted interaction between PTEN and miR-21-5p

To confirm the targeted interaction between PTEN and miR-21-5p, a dual-luciferase reporter assay was performed. As shown in Fig. 5, the results demonstrate a direct interaction between PTEN and miR-21-5p.

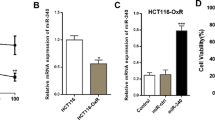

Validation of miR-21 mimic transfection efficiency

To investigate the regulatory mechanism of KAL in CCA cells, mimic NC and miR-21 mimic were transfected into HUCCT1 and RBE cells. As shown in Fig. 6, the miRNA expression levels of miR-21-5p were significantly elevated in the miR-21 mimic group compared to the normal control group, confirming the effectiveness of the miR-21 mimic transfection.

miR-21 reverses the effects of KAL on CCA cell proliferation and migration

HUCCT1 and RBE cells with KAL overexpression were transfected with either mimic NC or miR-21 mimic. As shown in Fig. 7A; Table 3, the cell viability of the OE-KAL + miR-21 mimic group was significantly increased compared with the OE-KAL and OE-KAL + mimic NC groups. As shown in Fig. 7B; Table 3, the apoptosis level of the OE-KAL + miR-21 mimic group was significantly decreased compared with the OE-KAL and OE-KAL + mimic NC groups. As shown in Fig. 7C; Table 3, the invasion ability of the OE-KAL + miR-21 mimic group was significantly increased compared with the OE-KAL and OE-KAL + mimic NC groups. These results indicate that miR-21 overexpression can markedly reverse the effects of KAL on the proliferation, apoptosis, and migration of cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) cells.

miR-21 reverses the effects of KAL on CCA cell proliferation, migration, and apoptosis. (A) CCK8 assay for proliferation levels in HUCCT1 and RBE cells. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of apoptosis in CCA cells (C) Transwell assay for invasion levels in HUCCT1 cells (n ≥ 3;*P < 0.05 vs. OE-KAL; #P < 0.05 vs. OE-KAL + mimic NC).

miR-21 reverses the effects of KAL on PIP3 secretion in CCA cells

As shown in Fig. 8, the PIP3 levels in the OE-KAL + miR-21 mimic group showed an increasing trend compared to the OE-KAL and OE-KAL + mimic NC groups in both cell lines, with statistically significant differences observed in HUCCT1 cells. These results suggest that miR-21 significantly reverses the inhibitory effects of KAL on PIP3 secretion in CCA cells.

miR-21 reverses the effects of KAL on the AKT pathway and apoptosis-related protein expression in CCA cells

Western blot analysis was conducted to examine the expression levels of AKT, P-AKT, MTOR, P-MTOR, PTEN, Cleaved-Caspase3, and BCL-2 in HUCCT1 cells. As shown in Fig. 9A, P-AKT/AKT, P-MTOR/MTOR, and BCL-2 protein expression levels were elevated in the OE-KAL + miR-21 mimic group compared to the OE-KAL + mimic NC group. Conversely, PTEN and Cleaved-Caspase3 expression levels were significantly reduced.

Similarly, in RBE cells, as shown in Fig. 9B, P-AKT/AKT, P-MTOR/MTOR, and BCL-2 protein levels were significantly increased in the OE-KAL + miR-21 mimic group compared to the OE-KAL + mimic NC group, while PTEN and Cleaved-Caspase3 levels were significantly decreased. These results indicate that miR-21 can reverse the effects of KAL on the PTEN/AKT pathway and apoptosis-related protein expression in CCA cells.

miR-21 reverses the effects of KAL on the AKT pathway and apoptosis-related protein expression in CCA cells. (A) Western blot analysis of Cleaved-Caspase3, PTEN, AKT, P-AKT, MTOR, P-MTOR, and BCL-2 protein expression levels in HUCCT1 cells. (B) Western blot analysis of Cleaved-Caspase3, PTEN, AKT, P-AKT, MTOR, P-MTOR, and BCL-2 protein expression levels in RBE cells (n ≥ 3; *P < 0.05 vs. OE-KAL; #P < 0.05 vs. OE-KAL + mimic NC).

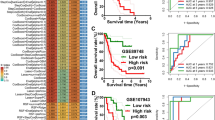

In vivo validation of the effects of KAL overexpression lentivirus on CCA tumorigenesis

HUCCT1 cells were subcutaneously injected into nude mice. When tumors reached 80–100 mm³ in size, the mice were divided into groups and treated with the corresponding lentivirus. Tumor weight and volume were recorded in the supplement Table 1. The results are shown in Fig. 10. Figures 10A–B present the viral qPCR and Western blot validation results, showing that KAL expression was significantly increased in the KAL overexpression group compared with the Control and Vector groups. Figure 10C shows the images of tumor formation in nude mice, Fig. 10D illustrates the changes in tumor volume over time, and Fig. 10E presents the statistical analysis of tumor volumes at the experimental endpoint. After injection of HUCCT1 cells into nude mice, the tumor volume gradually increased. However, compared with the Control group, tumor volume decreased progressively after injection of KAL-overexpressing lentivirus. Figure 10F shows the statistical analysis of tumor weight changes, indicating that tumor weight tended to decrease in the KAL overexpression group, although the difference was not statistically significant. These findings suggest that KAL overexpression can inhibit tumor formation of CCA cells in vivo.

In vivo validation of the effect of KAL-overexpressing lentivirus on tumor formation of CCA cells. (A) qPCR verification of viral transfection efficiency; (B) Western blot verification of viral transfection efficiency; (C) Images of tumor formation in nude mice; (D) Changes in tumor volume over time; (E) Statistical analysis of tumor volume at the experimental endpoint; (F) Statistical analysis of tumor weight; n ≥ 3.

KAL suppresses proliferation and promotes apoptosis in CCA xenografts

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed on tumor tissues to assess the positive expression levels of Bcl-2, Cleaved-Caspase3, PTEN, and KI67. As shown in Fig. 11, compared to the Control group, the KAL overexpression group exhibited significantly increased positive expression of Cleaved-Caspase3 and PTEN, while the positive expression levels of KI67 and Bcl-2 were significantly reduced. These results indicate that KAL overexpression suppresses CCA cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis in CCA xenografts.

KAL suppresses proliferation and promotes apoptosis in CCA xenografts. Immunohistochemical analysis of KI67 and apoptosis-related protein positive expression in tumor tissues. (A) Immunohistochemical staining images. (B) Quantitative analysis of protein positive expression (n ≥ 3; *P < 0.05 vs. OE-KAL; #P < 0.05 vs. OE-KAL + mimic NC).

Discussion

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a malignant epithelial tumor of the biliary tract with no specific tumor markers currently identified, making early clinical detection extremely challenging. As a result, most CCA patients are diagnosed at advanced stages, with the disease showing significant resistance to various chemotherapeutic drugs25,26. Research into the molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways underlying CCA’s development, migration, and metastasis remains limited compared to other digestive system tumors. This highlights the urgent need for fundamental research on CCA to reveal its pathogenesis and identify specific tumor markers for early diagnosis27,28.

In this study, we constructed KAL-overexpressing CCA cell lines via adenoviral transfection. Our findings demonstrated that KAL overexpression significantly suppressed CCA cell proliferation and migration while promoting apoptosis. Furthermore, KAL overexpression markedly reduced tumor volume in a mouse xenograft model, accompanied by decreased KI67 expression and increased levels of apoptosis-related proteins, suggesting that KAL may serve as a critical suppressor in CCA progression.

Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3), an essential intracellular second messenger, is generated by the phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) via phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)29. PIP3 plays a pivotal role in various cellular processes, including growth, survival, metabolism, migration, and cell cycle regulation. It recruits and activates AKT (protein kinase B) and other PH-domain-containing signaling proteins to the plasma membrane, triggering downstream signaling pathways23. The downstream AKT pathway is crucial in CCA development. In CCA, AKT signaling promotes tumor growth through mTORC1 activation, which facilitates cell proliferation and growth via alternative kinase pathways rather than lipid synthesis, as observed in hepatocellular carcinoma30. Moreover, AKT pathway activation is closely associated with CCA cell proliferation and migration, and its inhibitors can promote apoptosis and suppress tumor growth31,32. Consistent with the findings of Zhang et al. regarding Tip6033, we observed that KAL overexpression suppressed CCA cell proliferation and migration while reducing PIP3 production and AKT pathway activity. This suggests that KAL’s inhibitory effects on CCA progression are closely related to PIP3/AKT pathway suppression.

miR-21 is a non-coding single-stranded RNA molecule comprising approximately 18 to 27 nucleotides. It plays a significant role in tumorigenesis by regulating target gene-associated signaling pathways34. miR-21 is frequently upregulated in various cancers, and its abnormal expression is closely associated with tumor progression. It promotes tumor cell proliferation, inhibits apoptosis, enhances invasiveness and metastasis, and contributes to resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy35,36,37. Liu et al. reported significantly elevated miR-21 levels in the serum of CCA patients, correlating with tumor stage, lymph node metastasis, and poor prognosis21. Lu et al. demonstrated that miR-21 promotes CCA progression and tumor growth by targeting NAD(+)-dependent 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15-PGDH)38. Wang et al. further revealed that miR-21 enhances CCA proliferation and growth by inhibiting PTPN14 and PTEN, two functional targets22. In this study, we found that the inhibitory effects of KAL on CCA cell proliferation, migration, and apoptosis, as well as its suppression of the PIP3/AKT pathway, were significantly reversed by miR-21 mimic transfection. These findings suggest that KAL’s inhibitory role in CCA progression is closely linked to miR-21. Our findings on miR-21’s promotion of the AKT pathway in CCA cells are consistent with the results of Liu et al.39.

This study has some limitations. First, the effects of KAL on the AKT pathway were only partially reversed by miR-21 mimic, and some protein expression differences were not statistically significant. This suggests that other regulatory mechanisms may be involved, warranting further investigation. Additionally, the inhibitory effects of KAL on tumor growth in the mouse xenograft model were not statistically significant, likely due to the choice of CCA cell lines. Future studies will focus on selecting CCA cell lines with the lowest KAL expression levels to provide stronger evidence supporting KAL’s role in CCA progression. Moreover, we acknowledge that our current data are based primarily on PTEN expression levels and indirect readouts such as PIP3 reduction. these findings do not fully exclude the possibility that other phosphatases (e.g., SHIP1/2) may also contribute to the observed changes in PIP3 levels. More direct evidence of PTEN activation, such as measurement of its phosphatase activity using commercial activity assays, or analysis of critical phosphorylation sites would provide stronger mechanistic support. Although such assays were beyond the scope of the present work, they represent an important direction for our future studies.

In summary, KAL may suppress cholangiocarcinoma growth by downregulating miR-21 and modulating the PTEN/AKT signaling pathway.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Scott, A. J., Sharman, R. & Shroff, R. T. Precision medicine in biliary tract Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 40 (24), 2716–2734 (2022).

Chen, Y., Xu, Y. & Zhang, Y. Current status of laparoscopic radical hilar cholangiocarcinoma in Mainland China. Biosci. Trends. 14 (3), 168–173 (2020).

Soares, K. C. et al. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: diagnosis, treatment options, and management. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 3 (1), 18–34 (2014).

Bertuccio, P. et al. Global trends in mortality from intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 71 (1), 104–114 (2019).

Elvevi, A. et al. Clinical treatment of cholangiocarcinoma: an updated comprehensive review. Ann. Hepatol. 27 (5), 100737 (2022).

Ilyas, S. I. et al. Cholangiocarcinoma - evolving concepts and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 15 (2), 95–111 (2018).

Ilyas, S. I. & Gores, G. J. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 145 (6), 1215–1229 (2013).

Zhang, H. et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and surgical management. Cancer Lett. 379 (2), 198–205 (2016).

Saha, S. K. et al. Forty-Year trends in cholangiocarcinoma incidence in the U.S.: intrahepatic disease on the Rise. Oncologist 21 (5), 594–599 (2016).

Maccoll, G. S., Quinton, R. & Bulow, H. E. Biology of KAL1 and its orthologs: implications for X-linked Kallmann syndrome and the search for novel candidate genes. Front. Horm. Res. 39, 62–77 (2010).

Sarfati, J. et al. Kallmann syndrome with FGFR1 and KAL1 mutations detected during fetal life. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 10, 71 (2015).

Matsushima, S. et al. Anosmin-1 activates vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and its related signaling pathway for olfactory bulb angiogenesis. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 188 (2020).

Stamou, M. I. & Georgopoulos, N. A. Kallmann syndrome: phenotype and genotype of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Metabolism 86, 124–134 (2018).

Liu, J. et al. Decreased expression of Kallmann syndrome 1 sequence gene (KAL1) contributes to oral squamous cell carcinoma progression and significantly correlates with poorly differentiated grade. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 44 (2), 109–114 (2015).

Tanaka, Y. et al. Translational implication of Kallmann syndrome-1 gene expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 46 (6), 2546–2554 (2015).

García-González, D. et al. Anosmin-1 over-expression increases adult neurogenesis in the subventricular zone and neuroblast migration to the olfactory bulb. Brain Struct. Funct. 221 (1), 239–260 (2016).

Zhou, X. et al. Comprehensive analysis of anosmin-1 as a potential biomarker and its correlation with epithelial-mesenchymal transition in advanced gastric cancer. 3 Biotech. 15 (7), 222 (2025).

Martirosyan, N. L. et al. The role of MicroRNA markers in the Diagnosis, Treatment, and outcome prediction of spinal cord Injury. Front. Surg. 3, 56 (2016).

Jenike, A. E. & Halushka, M. K. miR-21: a non-specific biomarker of all maladies. Biomark. Res. 9 (1), 18 (2021).

Singh, A. et al. The role of microRNA-21 in the onset and progression of cancer. Future Med. Chem. 13 (21), 1885–1906 (2021).

Liu, C. H. et al. Circulating microRNA-21 as a prognostic, biological marker in cholangiocarcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 14 (1), 220–225 (2018).

Wang, L. J. et al. MiR-21 promotes intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma proliferation and growth in vitro and in vivo by targeting PTPN14 and PTEN. Oncotarget 6 (8), 5932–5946 (2015).

Nguyen Huu, T. et al. Redox regulation of PTEN by Peroxiredoxins. Antioxid. (Basel), 10(2), 302–315 (2021).

Liao, W. et al. CircZNF215 promotes tumor growth and metastasis through inactivation of the PTEN/AKT pathway in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 42 (1), 125 (2023).

El Jabbour, T., Molnar, A. & Lagana, S. M. Challenges in diagnosing and reporting Cholangiocarcinoma. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 16 (3), 599–608 (2023).

Khan, A. S. & Dageforde, L. A. Cholangiocarcinoma. Surg. Clin. North. Am. 99 (2), 315–335 (2019).

Labib, P. L., Goodchild, G. & Pereira, S. P. Molecular pathogenesis of Cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 19 (1), 185 (2019).

Macias, R. I. R. et al. Clinical relevance of biomarkers in cholangiocarcinoma: critical revision and future directions. Gut 71 (8), 1669–1683 (2022).

Lee, J. et al. IFITM3 functions as a PIP3 scaffold to amplify PI3K signalling in B cells. Nature 588 (7838), 491–497 (2020).

Corti, F. et al. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in biliary tract cancers: A review of current evidences and future perspectives. Cancer Treat. Rev. 72, 45–55 (2019).

Acharya, B., Chaijaroenkul, W. & Na-Bangchang, K. Atractylodin inhibited the migration and induced autophagy in cholangiocarcinoma cells via PI3K/AKT/mTOR and p38MAPK signalling pathways. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 73 (9), 1191–1200 (2021).

Li, L. et al. Triptolide inhibits intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma growth by suppressing Glycolysis via the AKT/mTOR pathway. Phytomedicine 109, 154575 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Tip60 suppresses cholangiocarcinoma proliferation and metastasis via PI3k-AKT. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 50 (2), 612–628 (2018).

Arghiani, N. & Matin, M. M. miR-21: A key small molecule with great effects in combination cancer Therapy. Nucleic Acid Ther. 31 (4), 271–283 (2021).

Akhtarkhavari, T., Bahrami, A. R. & Matin, M. M. Downregulation of miR-21 as a promising strategy to overcome drug resistance in cancer. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 932, 175233 (2022).

Bica-Pop, C. et al. Overview upon miR-21 in lung cancer: focus on NSCLC. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75 (19), 3539–3551 (2018).

Javanmardi, S. et al. miR-21, an oncogenic target MiRNA for cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms and recent advancements in chemo and Radio-resistance. Curr. Gene Ther. 16 (6), 375–389 (2017).

Lu, L. et al. miR-21 targets 15-PGDH and promotes cholangiocarcinoma growth. Mol. Cancer Res. 12 (6), 890–900 (2014).

Liu, C. H. et al. miR-21 and KLF4 jointly augment epithelial–mesenchymal transition via the Akt/ERK1/2 pathway. Int. J. Oncol. 50 (4), 1109–1115 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Supported by Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China(grant number 2023J01657)and Provincial Key Clinical Specialty in Interventional Radiology (grant number 2128200744 ).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhen Chi: Study conception and design, Experiment execution. Xin Lin: Study conception and design, Data acquisition and analysis. Leye Yan: Study conception and design. Jingyao Huang: Study conception and design, Data acquisition and analysis, final approval and overall responsibility for the published work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to partipate

The animal experiment in this study followed the 3Rs guideline (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) and was approved by the IACUC of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital. The approval number is FJMU 2023-Y-0963, and the approval date is 28 July 2023.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, J., Chi, Z., Lin, X. et al. KAL suppresses cholangiocarcinoma growth via downregulating miR-21 and modulating the PTEN/AKT signaling pathway. Sci Rep 15, 45326 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29568-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29568-0