Abstract

Age-related hearing loss (ARHL) has a multifactorial pathogenesis, and the influence of alcohol consumption on it is controversial. This cross-sectional study investigated the association between ARHL and alcohol consumption by using cohort data from Tohoku Medical Megabank Project, including self-reported questionnaires and pure-tone audiometry thresholds (500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz). ARHL was defined as a threshold of > 25 dB in the better ear. Multiple logistic regression analyses (age 50–79 y; 5,219 men and 9,266 women) were conducted separately for men and women and indicated that daily alcohol consumption levels of 60–80 and ≥ 80 g were significantly associated with increased odds of ARHL at 4,000 Hz in men (odds ratio [OR] 1.42; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.05–1.94; OR 1.55; 95% CI 1.12–2.16; respectively); consumption of 10–20 g was significantly associated with reduced odds of ARHL at 4,000 Hz in women (OR 0.81; 95% CI 0.68–0.96). Assessment of drinking-related single nucleotide polymorphisms suggested that the effect of alcohol on ARHL may differ by genotype. Our findings suggest a sex-specific association between alcohol consumption and ARHL; heavy drinking is a potential risk factor in men, whereas moderate drinking may have a protective effect in women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Age-related hearing loss (ARHL) is a common disorder in older adults that causes a decline in hearing function, manifesting as increased hearing thresholds and decreased frequency resolution, with a prevalence of 65.3% in people aged 71 y and older and 96.2% in those 90 y and older1. As life expectancy increases worldwide, the number of people affected by ARHL is expected to increase2. ARHL has been linked to depression, dementia, and frailty in old age3,4. Hearing loss has become an important public health issue as it is a major risk factor for dementia that can be intervened upon5.

The proposed mechanism of ARHL is multifactorial and involves chronic inflammation, ototoxic drugs, noise, and atherosclerosis, which increase production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the inner ear. This leads to increased oxidative stress and necrosis and apoptosis of inner ear cells, causing ARHL6. Epidemiological studies have reported that genetic predisposition (sex, race, genes), environmental factors (socioeconomic status, noise exposure, smoking), and comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes) are independent risk factors for ARHL7. Moreover, recent studies have suggested that oral health may also play a role. Tooth loss has been proposed as a potential risk factor for ARHL, reflecting nutritional as well as systemic health status. A longitudinal study demonstrated that a reduction in the number of teeth was significantly associated with hearing decline in older adults8. Our previous study also suggested that tooth loss may represent an independent risk factor for hearing loss9.

Alcohol consumption is a proven risk factor for esophageal cancer; however, there is no consensus regarding the role of alcohol in diseases such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes, with conflicting reports of protective and harmful effects10,11. Similarly, studies on the effects of alcohol on hearing loss have not yielded consistent results12,13,14,15. Dawes et al. categorized alcohol consumption into five categories: never drinkers; ex-drinkers; the lowest 25% of alcohol drinkers (1 to 118.4 g ethanol per week); middle 50% (118.4 to 196.8 g ethanol per week); and the top 25 percentile (greater than 196.8 g ethanol consumption per week), and reported that all drinking groups had a lower risk of hearing loss than the never-drinker group, indicating that alcohol has a protective effect on hearing16. However, since their study did not include a heavy drinking group (generally \(>\) 40 g of pure alcohol per day for men and \(>\) 20 g for women17), it is impossible to estimate the appropriate upper limit of alcohol consumption for each sex that has a protective effect on hearing. Conversely, a recent meta-analysis of the association between alcohol consumption and hearing loss compared current drinking and non-drinking groups, and concluded that drinkers were at a higher risk of hearing loss than non-drinkers18. Based on these results, we hypothesized that a certain amount of alcohol consumption may be associated with a lower risk of hearing loss, whereas it could act as an aggravating factor above a specific amount. Some studies have suggested that low-to-moderate drinking has a protective effect on the heart and reduces the risk of hypertension and diabetes10. Regarding the underlying mechanism, it has been suggested that alcohol may alleviate certain processes that cause atherosclerosis and inflammation10. Since the pathogenesis of ARHL involves oxidative stress in the inner ear due to inflammation and atherosclerosis6,19, moderate alcohol consumption may protect against hearing loss.

One possible reason for the inconsistent results of previous studies was that a uniform definition of hearing loss was not used. Specifically, different testing methods, such as three-tone tests for speech in noise, subjective questionnaires, and pure-tone audiometry, as well as various cutoff values for hearing loss, were adopted across studies18,20. Therefore, further studies building on accurate hearing evaluations, a clear and consistent definition of hearing loss, and detailed assessment of alcohol consumption would be valuable.

The Tohoku Medical Megabank (TMM) project aims to solve medical problems and provide personalized healthcare by conducting a prospective cohort study of the local population in the Tohoku region of Japan in combination with population genomics21. The integrated biobank of the TMM contains health and clinical information, biospecimens, and genome and omics data, including detailed diet and alcohol consumption questionnaires and thresholds of pure-tone audiometry results (500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz). This study aimed to examine the association between ARHL and alcohol consumption using data from a large community-based study of Japanese men and women.

Material and methods

Study design and population

The data for this cross-sectional study were obtained from two cohort studies conducted by Tohoku University Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization (ToMMo): the TMM Community-Based Cohort Study (TMM CommCohort Study) and TMM Birth and Three-Generation Cohort Study (TMM BirThree Cohort Study). The TMM CommCohort Study enrolled participants aged ≥ 20 y at specific health checkup sites and collected basic information and samples after recruitment. The TMM BirThree Cohort Study is a family-based cohort study involving pregnant women and their families. This study was approved by the Ethical Research Committee of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine (2024-1-929). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants at each study visit21.

Overall, 25,009 participants of the two abovementioned cohort studies aged 20 y or older living in Miyagi Prefecture, Japan, underwent pure-tone audiometry at four frequencies between July 2021 and January 2024. Since the purpose of the current study was to assess ARHL and its risk factors, participants who reported a history of chronic otitis media or who did not provide information on this item (155 men, 259 women) were excluded. Moreover, participants aged 49 y or younger (2,277 men and 7,275 women) or over the age of 80 y (38 men and 34 women) were excluded because the effects of aging were minimal and the number of older participants was too small to guarantee anonymity, respectively.

Audiometric assessments

Hearing sensitivity was assessed using a pure-tone audiometer (AA-H1; RION, Tokyo, Japan) and soundproof booth (AT-66; RION, Tokyo, Japan). Pure-tone thresholds via air conduction were recorded at frequencies of 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz, and the pure-tone average (PTA) was calculated for each side. We used the PTA of the better-hearing ear to assess the severity of hearing impairment. The better-hearing ear was chosen for evaluation because it conforms to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria of hearing loss and to minimize the effect of middle ear disease22, which cannot be excluded by self-reported questionnaires. In this study, hearing loss was defined as pure-tone threshold > 25 dB hearing level (HL). Hearing loss was categorized based on the PTA in the better-hearing ear as normal: ≤ 25 dB HL, mild: > 25 and ≤ 40 dB HL, moderate: > 40 and ≤ 70 dB HL, and severe: > 70 dB HL23. In the most recent WHO report, the upper limit of normal hearing was lowered from 25 to 20 dB22, but for the purpose of assessing the risk factors for ARHL, the difference from normal hearing should be more evident. Therefore, we set the threshold for hearing loss above 25 dB HL, as did previous studies1. We evaluated both the PTA of four frequencies and the threshold of 4,000 Hz, which is the high-frequency region that is more vulnerable to age-related changes1.

Assessing alcohol consumption

A detailed self-reported questionnaire (see Supplementary file 1 for the English translation) was administered to assess alcohol consumption. Information on individual drinking habits (type, quantity, and frequency) was converted into ethanol intake (g/day)24. Alcohol consumption (g/day) in this study was calculated as follows. First, for each type of alcoholic beverage, the frequency of drinking was converted to a numeric value (every day = 7; 5–6 days/week = 5.5; 3–4 days/week = 3.5; 1–2 days/week = 1.5; no habitual drinking = 0). This value was multiplied by the reported amount per drinking occasion and then divided by 7 to obtain the average daily intake (mL/day). Subsequently, the average daily pure alcohol intake (g/day) was calculated using the following formula: Average daily alcohol consumption (g/day) = average daily intake (mL) × alcohol content (%) ÷ 100 × specific gravity of ethanol (0.8 g/mL). In this study, one drink was defined as follows: Japanese sake, 180 mL (16%); Shochu (including plum wine), 180 mL (25%); Chuhai (shochu-based cocktail), 180 mL (9%); Beer/low-malt beer, 1 large bottle 633 mL (4.6%); Whisky single, 30 mL (40%); Whisky double, 60 mL (40%); and Wine, 1 glass 100 mL (12%).

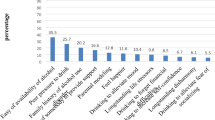

Based on the calculated alcohol consumption (g/day), men were divided into seven categories: current and former non-drinker (0 g/day [never-drinker]), 0 g/day currently but former drinker (0 g/day [past-drinker]), 0–20 g/day, 20–40 g/day, 40–60 g/day, 60–80 g/day, and ≥ 80 g/day. To reflect sex-specific differences in alcohol metabolism, women were also divided into seven groups based on half the amount of alcohol consumed in the corresponding groups of men: 0 (never-drinker and past-drinker), 0–10, 10–20, 20–30, 30–40, and ≥ 40 g/day. Women are known to differ from men in several physiological aspects of alcohol handling, including lower gastric alcohol dehydrogenase activity leading to reduced first-pass metabolism, smaller volume of distribution resulting in higher blood alcohol concentrations for the same intake, and faster hepatic ethanol oxidation rate25. These factors collectively contribute to a higher production of hepatotoxic metabolites such as acetaldehyde and ROS, potentially rendering women more sensitive to the pharmacological effects of ethanol. In recognition of the sex-specific differences in alcohol metabolism, international guidelines, including those of the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension, recommend no more than two drinks per day for men and one drink per day for women26. Therefore, we established this classification scheme to adequately capture the range of alcohol consumption from light to heavy drinking in both sexes.

Model covariates

A detailed self-reported questionnaire was administered to assess the participants’ characteristics. Information on past history of cardiovascular disease and chronic otitis media, current medical conditions including hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia (defined as self-reported physician diagnosis or current medication use), and family history of hearing loss was collected. Educational status was classified into three categories: university/graduate school; high school/technical school/junior college/technical college; and elementary/junior high school. Smoking status was classified into three categories: never smokers (smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime), former smokers (smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and do not currently smoke), and current smokers (smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and currently smoke). Noisy occupations were defined as forestry, mining, construction, and manufacturing industries9. Height was measured using a height meter (AD-6400, A&D Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and weight was measured using a body composition monitor (InBody720 or InBody770, Biospace Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the weight (kg) by height squared (m2). The number of teeth was determined by dental examination and categorized into the following three groups: [1] 0–9, [2] 10–19, and [3] 20–28 teeth. An unknown value for any item was considered a missing value and excluded from the multivariable analysis.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)

To investigate whether the effect of alcohol consumption on ARHL differs depending on the genotype, rs671 (acetaldehyde dehydrogenase2 [ALDH2]), rs79463616 (acetaldehyde dehydrogenase2 [ALDH2]), rs1260326 (glucokinase regulatory protein [GCKR]), rs28712821 (klotho beta [KLB]), rs1229984 (alcohol dehydrogenase 1B [ADH1B]), rs2228093 (acetaldehyde dehydrogenase1B1 [ALDH1B1]), rs8187929 (acetaldehyde dehydrogenase1A1 [ALDH1A1]), and rs73550818 (glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 2 [GOT2]) were selected as the target SNPs for the current study from a previous Japanese genome-wide association study (GWAS) on alcohol consumption and risk of esophageal cancer27. Genomic data were obtained from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data of the Tohoku Medical megabank28.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R version 4.2.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). For comparison of background characteristics between men and women, continuous data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test for independent samples and categorical data were analyzed using the two-tailed χ2 test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant based on two-sided tests. Data are presented as medians (interquartile range [IQR]) for continuous variables and numbers (%) for categorical variables. Because the prevalence of hearing loss and distribution of confounding factors differed widely between men and women, all subsequent analyses were performed separately for men and women. For multivariable logistic regression analysis, the presence of hearing loss was counted as a dependent variable, and the explanatory variables were selected based on the issues of interest in this study and clinically relevant factors from previous studies (age, history of cardiovascular disease, noisy occupation, family history of hearing loss, educational history, number of teeth, smoking status, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and alcohol drinking status)9,29,30,31. Because this study included two different cohort studies, the cohort type was also included as a covariate to account for background differences. First, we ran a univariable model of the candidate risk factors for hearing loss as described earlier (crude value). Next, we ran a multivariable model that included all the candidate risk factors for hearing loss as covariates (multivariable-adjusted values).

To analyze the association between each SNP and hearing loss, we first performed univariable analyses and then multivariable analyses, excluding hyperlipidemia as a covariate because we found no significant association between hearing loss and hyperlipidemia in the univariable analyses. Because of the rarity of SNPs, the number of variant homozygotes for some of the genotypes was small, and a sufficient number of participants for the analysis was not available for the seven groups of alcohol consumption status. Therefore, ex-drinkers were excluded to ensure linearity in alcohol consumption. To further exclude outliers, the median alcohol consumption for each category was fitted and entered into the explanatory variables as a continuous variable. Because each SNP has been shown to be associated with alcohol consumption, we evaluated multiplicative interaction models between alcohol consumption and each SNP genotype using logistic regression. For these models, we estimated the regression coefficient (β) for the interaction term (alcohol × SNP), and presented the corresponding odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI), along with both unadjusted P values and false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P values. To correct for multiple testing in the interaction analysis, the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was applied to control the FDR. An FDR-adjusted P value of < 0.1 was considered statistically significant. The genotypes for which the interaction was significant were subjected to subgroup analysis to evaluate the association between the alcohol consumption categories (g/day) and hearing loss within strata; however, this analysis alone does not allow a distinction between genuine gene–environment interactions and group heterogeneity. When the genotype that showed a significant relationship with alcohol consumption was a heterozygote, subgroup analysis was performed for two groups: a heterozygotes and variant homozygotes group versus wild-type group, because the number of variant homozygotes was small and because of the functional aspect of the allele. When the genotype that was found to be significant was a variant homozygote, a subgroup analysis was performed with two groups: variant homozygotes versus wild-type and heterozygotes for the mutation, assuming recessive inheritance.

Results

Demographics of the participants

The number of participants who met the study criteria at each stage of the analysis is shown in Fig. 1. Overall, 14,971 participants (5,376 men and 9,595 women) were analyzed separately by sex for univariate analyses. The demographic data are presented in Table 1. The median age of the study participants was 65.1 [62.0–69.1] y for men and 62.0 [57.1–66.3] y for women. The PTA of the better hearing ear was 28.4 [20.0–36.3] dB HL for men and 23.1 [15.0–28.8] dB HL for women, with men having a higher threshold than women. Men had higher median threshold values than women at all frequencies, and the light, moderate, and severe hearing loss categories had a greater proportion of men than women. All candidate factors affecting hearing loss differed between men and women except for a family history of hearing loss (Table 1).

Validation of self-reported alcohol consumption

Because alcohol intake in this study was assessed using a self-reported questionnaire, it was necessary to confirm the validity of the questionnaire-based estimates. γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP) is a well-established biomarker of liver function and is widely known to be closely associated with alcohol consumption32. To examine the validity of the self-reported alcohol consumption questionnaire, we performed linear regression analyses of alcohol intake (g/day) against serum γ-GTP levels. A significantly positive association was observed in both men and women: β = 5.97 (95% CI 5.29–6.64, P < 0.001) in men; and β = 1.23 (95% CI 0.85–1.61, P < 0.001) in women. These findings indicate that alcohol intake estimates derived from the questionnaire reasonably reflected alcohol-related biochemical changes. Furthermore, a validation study of the TMM project food frequency questionnaire evaluated the validity and reproducibility of dietary intake. In this study, participants completed weighed food records for 3 consecutive days in each season (12 days in total) and food frequency questionnaires in 2019 and 2021. For alcohol intake, high validity was observed between the weighed food records and the food frequency questionnaire (correlation coefficients: men, 0.89; women, 0.66); good reproducibility was confirmed between the two food frequency questionnaires administered 2 years apart (men, 0.86; women, 0.77)33. Together, these findings provide support for the validity and reproducibility of alcohol intake estimates derived from the food frequency questionnaire of the TMM project.

Multivariable analyses of men

Using the data of 14,485 participants (5,219 men and 9,266 women) with no missing values in the covariates, multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the associations between various factors, including alcohol intake and ARHL. The following factors were significantly associated with the presence of hearing loss, based on the PTA in men: older age (P < 0.001), family history of hearing loss (P = 0.001), education below high school (P < 0.001), and fewer remaining teeth (10–19) (P = 0.042). The prevalence of hearing loss in participants of the TMM BirThree Cohort Study was significantly lower than that in participants of the TMM CommCohort Study (P < 0.001). Although not significantly different, there was a trend toward increased hearing loss in men with a history of cardiovascular disease (P = 0.075), fewer than 10 remaining teeth (P = 0.065), current smokers (P = 0.078), past drinkers (P = 0.071), and 80 g or more alcohol consumption (P = 0.072). At 4,000 Hz, the following factors demonstrated significant associations with the presence of the hearing loss in men: older age (P < 0.001), family history of hearing loss (P = 0.035), education below high school (P < 0.001), 60–80 g alcohol consumption (OR 1.42; 95% CI 1.05–1.94; P = 0.026), and 80 g or more alcohol consumption (OR 1.55; 95% CI 1.12–2.16; P = 0.009). Similar to the PTA, the prevalence of hearing loss in participants of the TMM BirThree Cohort Study was significantly lower than that in participants of the TMM CommCohort Study (P < 0.001). There was also a trend toward greater hearing loss in the current smoking group (P = 0.086) (Table 2).

Multivariable analyses of women

The following factors were significantly associated with the presence of hearing loss, as evaluated by the PTA in women: older age (P < 0.001), family history of hearing loss (P = 0.001), education below high school level (P < 0.001), fewer remaining teeth (10–19 and 0–9: P < 0.001 and P = 0.007, respectively), and diabetes (P = 0.036). The 10–20 g drinking group tended to have less hearing loss, although no statistically significant differences were found (P = 0.097). At 4,000 Hz, the following factors were significantly associated with the presence of hearing loss in women: older age (P < 0.001), family history of hearing loss (P = 0.015), education below the high school level (P < 0.001), fewer remaining teeth (10–19 and 0–9: P < 0.001 and P = 0.043, respectively), and diabetes (P = 0.045). There was a trend toward greater hearing loss in the presence of hypertension (P = 0.084). Interestingly, women in the 10–20 g drinking group had significantly less hearing loss compared to the never-drinker group (OR 0.81; 95% CI 0.68–0.96; P = 0.016). As with men, the TMM BirThree Cohort Study reported significantly less hearing loss at the PTA and 4,000 Hz in women compared to the TMM CommCohort Study (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Genetic analysis

To analyze the associations between alcohol-related SNPs and ARHL, data from 3,992 men and 6,681 women with no missing covariate data, including SNPs, were analyzed. In men, rs2228093 variant homozygotes (T/T) was an independent risk factor for hearing loss (OR 1.35; 95% CI 1.08–1.69; P = 0.009). At the PTA, a significant interaction with alcohol consumption as a factor for hearing loss was observed in the rs671 (heterozygotes [G/A] + variant homozygotes [A/A]) group (β = -0.0060, OR = 0.994 [95% CI 0.988–0.999], P = 0.034, FDR-adjusted P = 0.034). In addition, rs79463616 heterozygotes (G/A) only (FDR-adjusted P = 0.065) and rs 79463616 (heterozygotes [G/A] + variant homozygotes [A/A]) group (FDR-adjusted P = 0.035) showed significant interactions with alcohol consumption at the PTA. At 4,000 Hz, significant interactions with alcohol consumption were observed in the rs671 heterozygotes (G/A) only (FDR-adjusted P < 0.001), rs671 (heterozygotes (G/A) + variant homozygotes [A/A]) group (FDR-adjusted P < 0.001), and rs73550818 variant homozygotes (A/A) (FDR-adjusted P = 0.018) (Table 4).

None of the SNPs were found to be independently associated with hearing loss in women. rs79463616 heterozygotes (G/A) only was found to interact with alcohol intake and was associated with hearing loss at both the PTA and 4,000 Hz (FDR-adjusted P = 0.001 and 0.047, respectively) (Table 5).

Subgroup analyses of SNPs that interacted with alcohol intake in men

For the genotypes for which the interaction was significant, subgroup analyses were performed to examine the association between each alcohol consumption group and hearing loss. In rs671 wild-type homozygote (G/G) participants among men, hearing loss at 4,000 Hz was significantly higher in the 80 g or more drinking group (OR 1.57; 95% CI 1.10–2.28; P = 0.015). In contrast, for the rs671 (heterozygotes [G/A] + variant homozygote [A/A]) group, we found no similar trend among the drinking groups. These results suggest that there was no association between alcohol consumption and hearing loss in participants who did not have a high alcohol tolerance. Among men, rs79463616 wild-type homozygote (G/G) participants, the 60–80 g drinking group, and 80 g or more drinking group tended to have more hearing loss, both at the PTA and 4000 Hz (at the PTA: P = 0.062 and P = 0.082, respectively; at 4000 Hz: P = 0.063 and P = 0.061, respectively). For rs73550818 variant homozygotes (A/A), the prevalence of hearing loss was significantly higher in the 80 g or more drinking group (OR 2.82; 95% CI 1.22–7.20; P = 0.021), while in wild-type homozygotes (C/C) and heterozygotes (C/A), there was no difference in hearing loss according to the amount of alcohol consumption (Table 6).

Subgroup analyses of SNPs that interact with alcohol intake in women

In rs79463616 wild-type homozygote (G/G) participants among women, hearing loss was significantly lower in the 10–20 g drinking group both at the PTA and 4000 Hz (OR 0.71; 95% CI 0.54–0.92; P < 0.01; and OR 0.69; 95% CI 0.54–0.88; P < 0.01, respectively). However, in the rs79463616 (heterozygotes [GA] and variant homozygotes [AA]) group, the prevalence of hearing loss was significantly higher in the 40 g or more drinking group (OR 1.82; 95% CI 1.08–3.06; P = 0.023) at the PTA (Table 7).

Supplementary analyses of interactions among SNPs

Supplementary analyses were conducted to explore potential interactions between alcohol consumption (the median alcohol intake for each category was fitted and entered into the models as a continuous variable, as described previously) and the SNPs that had shown significant multiplicative interactions with alcohol consumption in the primary models. Specifically, logistic regression models were constructed including alcohol × pairwise SNP combinations (alcohol × rs671 × rs73550818, alcohol × rs671 × rs79463616, and alcohol × rs79463616 × rs73550818) and an alcohol × three-SNP combination (alcohol × rs671 × rs73550818 × rs79463616), with adjustment for age. None of these interaction terms reached statistical significance (Supplementary Table 1).

Discussion

In this study, the effect of alcohol consumption on ARHL differed between men and women; ARHL was significantly higher in men in the heavy drinking group (more than 60 g), whereas hearing loss did not increase with increased alcohol consumption in women. In addition, we found that alcohol consumption in small amounts (10–20 g) may be protective against ARHL in women. Previous studies, including those by Dawes et al.16 and Fransen et al.34, have examined the association between alcohol consumption and hearing outcomes using audiometric data and analyses across intake levels. However, few large-scale studies have specifically addressed ARHL using sex-stratified analyses and detailed alcohol consumption categories. Therefore, our study adds further evidence to the literature and provides valuable data for future research on the relationship between ARHL and alcohol consumption.

Several studies have reported the protective effects of alcohol consumption in small to moderate amounts on hearing12,35. However, few large studies have examined these effects separately in men and women. Popelka et al. reported that moderate alcohol consumption (> 140 g/week) was inversely associated with hearing loss (mean of 500, 1000, 2000, 4000 Hz > 25 dB HL; OR 0.71; 95% CI 0.52–0.97), and this result was consistent across both sexes12. This finding differs from our results, which suggest that alcohol has a possible protective effect on ARHL in women only. Sex differences in the effects of alcohol on other diseases have been explored more than those on hearing loss10,11. For example, a meta-analysis examining the association between hypertension and alcohol consumption reported a linear increase in the hypertension risk in men consuming 31–40 g/day or more of alcohol, whereas in women, alcohol consumption of 15 g/day or less was associated with a protective effect, and consumption of 31–40 g/day was associated with a significantly increased risk of hypertension, demonstrating a J-shaped curve36. Our results reflect a partially similar trend, suggesting that there are sex-dependent differences in the protective effects of alcohol on ARHL, as for hypertension. Regarding the differences between our study and that of Popelka et al., we assumed that the possible reason for hearing loss being less in the drinking group in both men and women was that they did not exclude past drinkers from the 0 g group. In fact, in our analysis, when ex-drinkers and never drinkers were grouped together in the 0 g group, the 0–20 g group had a significantly lower prevalence of hearing loss in men. In general, especially in men, past drinkers included those who refrained from drinking alcohol for health or other reasons, which may have skewed the comparison between the 0 g and other groups. Therefore, we speculate that, as with other diseases, only women may benefit from low to moderate alcohol consumption to prevent ARHL.

Several mechanisms may underlie the protective effects of alcohol against hearing loss. Some reports have suggested that low-to-moderate alcohol intake has a favorable effect on insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism, which are important risk factors for the development of diabetes10. There are insulin receptors, glucose transporters, and insulin signaling components in the sensory receptors and supporting cells of the cochlea, stria vascularis, and spiral ligament37; therefore, improvement in insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism in women by an appropriate amount of alcohol may lead to the prevention of ARHL. Second, an appropriate amount of alcohol increases estrogen levels, which may lead to the suppression of hearing loss. A study of postmenopausal women reported that alcohol intake (1–2 drinks per day) significantly increased the serum levels of steroid hormones, such as dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and estrone sulfate, compared with placebo38. Estrogen, the primary sex steroid in women, is considered to be protective against hearing loss, which has been confirmed by the sex differences in hearing, the clinical picture of estrogen-deficient Turner’s syndrome, and animal studies39. However, few studies have investigated the mechanism underlying the effects of ethanol on hearing, and further clarification is needed, especially with regard to the ethanol volume and sex differences.

The relationship between heavy alcohol consumption and hearing impairment remains unclear, with some studies showing no effect and others confirming that alcohol is an exacerbating factor12,14,16,34. Our study showed that more than 60 g alcohol consumption was associated with increased hearing loss in men. There was no significant increase in the probability of hearing loss in women in the heavy drinking group, which may be due to the relatively small number of heavy drinkers among women. One possible mechanism underlying alcohol-induced ARHL is an increase in ROS levels due to heavy alcohol consumption. Alcohol facilitates ROS production and reduces levels of agents that can eliminate ROS7. ROS causes endothelial dysfunction and is involved in apoptosis and necrosis pathways in auditory tissues7. Consequently, heavy alcohol consumption can lead to hearing loss.

The novelty of the present study lies not only in the categorization of alcohol consumption or the use of pure-tone audiometry, but also in the incorporation of genetic analyses, which allowed us to examine potential gene–environment interactions in relation to ARHL. SNPs have been associated with the physical constitution and risk of developing several diseases, and several SNPs related to alcohol consumption have been reported in a Japanese GWAS27,40. The effect of alcohol consumption on ARHL may differ depending on the genotype of the SNPs. Therefore, we performed multivariable analysis that included each SNP as a covariate. Subgroup analysis showed that in men, rs671 wild-type homozygote (G/G) was associated with significantly more hearing loss in the 80 g or more drinking group. Although there was a limitation due to the small number of heavy drinkers, there was no increase in hearing loss with heavy alcohol consumption in the heterozygotes (G/A) and variant homozygotes (A/A) group. Alcohol is primarily metabolized to acetaldehyde by the alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) enzyme, and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) further detoxifies acetaldehyde to acetic acid41. rs671 is a functional SNP in the ALDH2 gene and genetic variant that strongly influences alcohol consumption41. These results were contrary to our expectation because it is known that rs671 wild-type homozygotes (G/G) do not accumulate acetaldehyde easily and have a low risk of alcohol-related cancer, while rs671 heterozygotes (G/A), who accumulate acetaldehyde easily, have an increased risk of alcohol-related cancer27. The harmful elements of alcohol are attributable to the toxicity of ethanol and its metabolites, such as acetaldehyde, and oxidative stress, with acetaldehyde in particular being considered a carcinogen10. Based on the results of the subgroup analysis of rs671, we speculated that inner ear damage caused by heavy drinking is largely due to mechanisms that do not involve acetaldehyde. It should be taken into consideration that rs671 heterozygotes (G/A) who drank heavily may have experienced reverse causation in that they had more chances to drink because of preserved hearing abilities and better communication skills. rs671 heterozygotes (G/A) often have increased health problems associated with alcohol consumption42, but our study results suggest that rs671 wild-type homozygotes (G/G) may need to be more careful about the amount of alcohol intake because of the effect on hearing.

Women possessing the rs79463616 A allele had a significantly higher prevalence of hearing loss at the PTA in the 40 g or more drinking group. Although the possibility of an incidental result cannot be ruled out because there was no similar trend at 4000 Hz, the rs79463616 A allele may accelerate hearing loss in heavy drinkers among women. rs79463616, like rs671, is a functional SNP in the ALDH2 gene; the rs79463616 A allele is associated with decreased expression of ALDH2 in multiple tissues, which has a protective effect by reducing the drinking intensity27. There are still many unknowns regarding the effects of the rs79463616A allele, and detailed analyses and experimental studies are needed to clarify its effects on hearing.

In men possessing rs73550818 variant homozygotes (A/A), heavy consumption of more than 80 g of alcohol significantly increased the risk of hearing loss, with a high OR (2.82). rs73550818 is a SNP of the GOT2 gene that is involved in amino acid metabolism and the urea circuit27,43. The A allele is associated with increased GOT2 expression in the liver and has been shown to decrease alcohol consumption in heterozygotes27. A GWAS of Japanese participants revealed that the rs73550818 A allele is significantly associated with elevated levels of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), a biochemical marker of liver injury44. In guinea pigs, AST activity is associated with energy metabolism in the cochlea45. Collectively, the rs73550818 variant may contribute to the development of ARHL in heavy drinkers among men through alterations in GOT2 or AST activity; however, further studies are required to clarify the effects of GOT2 and AST on cochlear pathophysiology.

Rs2228093 is a SNP of ALDH1B1, a mitochondrial ALDH isozyme with the second-highest affinity for acetaldehyde41. Men possessing rs2228093 variant homozygotes (T/T) had a higher prevalence of hearing loss at the PTA, independent of alcohol consumption (OR1.35; 95% CI 1.08–1.69). We consider this a plausible result because a trend toward increased hearing loss was also observed at 4000 Hz (P = 0.088) and the number of participants with this variant (n = 453) was sufficiently large. Although rs2228093 has previously been shown to be associated with alcohol consumption and alcohol-induced hypersensitivity in Japanese and Europeans41, its effect on ALDH1B1 enzyme activity is largely unknown. ALDH1B1 has been shown to be expressed at high levels in the small intestine, liver, and pancreas, and at lower levels in the lung and colon46. However, we could not find any studies that examined the expression of ALDH1B1 in the inner ear. Further investigation is needed to determine the mechanism of hearing loss in rs2228093 variant homozygotes (T/T) observed in this study.

We also investigated the associations between ARHL and physical, environmental, and lifestyle factors. In our analysis, older age, family history of hearing loss, and education below high school were associated with an increased risk of ARHL in both sexes, whereas the participants of the TMM BirThree Cohort Study showed a decreased prevalence of hearing loss. A trend toward increased hearing loss was observed in both men and women with 19 or fewer remaining teeth. The association of older age, family history of hearing loss, lower education, and residual teeth with hearing loss is concurrent with the results of previous studies9. The significantly lower prevalence of hearing loss in the participants of the TMM BirThree Cohort Study may be attributable to the high proportion of individuals with a spouse in this cohort. Previous studies have shown that a healthy diet contributes to better hearing thresholds at high frequencies47. Therefore, it is possible that having a spouse promoted healthier dietary habits, which in turn helped preserve hearing function.

This study has several limitations. First, it was a cross-sectional study and it is difficult to clearly establish a causal relationship between hearing loss and various background factors and SNPs. Therefore, future longitudinal cohort studies are warranted on this issue. Second, this study was conducted in a Japanese population, and the results may not be generalizable to other populations. In particular, Japanese women do not have heavy drinking habits; therefore, the association between heavy drinking and hearing loss in women may not have been adequately analyzed. However, a relatively homogeneous ethnic background may have allowed for a more accurate assessment of the effects of alcohol consumption. Third, alcohol consumption was quantified by self-reporting and not by the exact measurement of daily consumption. However, the type, amount, and frequency of alcohol consumption were calculated based on detailed questionnaires, and we believe that the results closely reflect alcohol consumption in the study population. Finally, otoscopy, tympanometry, and bone conduction testing were not performed in this study. Therefore, to address this limitation, we excluded participants with a history of chronic otitis media and chose the better-hearing ear for evaluation to reduce the likelihood of including conductive hearing loss. This approach also reduced the possibility of misclassifying unilateral sudden sensorineural hearing loss as ARHL. Since the prevalence of middle ear disorders and sensorineural hearing loss other than ARHL is not high, our research design was considered to be sufficient for evaluating the relationship between ARHL and alcohol consumption.

Conclusion

Our results show that, after adjustment for confounding factors, men who consumed more than 60 g of alcohol per day had significantly higher odds of hearing loss, whereas women who consumed 10–20 g per day had significantly lower odds, compared with lifetime abstainers. These results suggest that heavy drinking may be a risk factor for hearing loss in men, while moderate drinking (10–20 g of alcohol) may protect against hearing loss in women. Certain SNPs showed differences in the risk of hearing loss depending on the amount of alcohol consumed. However, further research is needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Data availability

Individual genotyping results and other cohort data used for the association study are stored in Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization. In response to reasonable requests for these data (contact us at dist@megabank.tohoku.ac.jp), we will share the stored data after assembling the data set and after approval of the Ethics Committee and the Materials and Information Distribution Review Committee of Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization.

References

Reed, N. S. et al. Prevalence of hearing loss and hearing aid use among US medicare beneficiaries aged 71 years and older. JAMA Netw. Open 6, e2326320–e2326320. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.26320 (2023).

Bowl, M. R. & Dawson, S. J. Age-related hearing loss. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a033217 (2019).

Wei, J., Li, Y. & Gui, X. Association of hearing loss and risk of depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 15, 1446262. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2024.1446262 (2024).

Tian, R., Almeida, O. P., Jayakody, D. M. P. & Ford, A. H. Association between hearing loss and frailty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 21, 333. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02274-y (2021).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the lancet standing commission. Lancet 404, 572–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(24)01296-0 (2024).

Yamasoba, T. et al. Current concepts in age-related hearing loss: epidemiology and mechanistic pathways. Hear. Res. 303, 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2013.01.021 (2013).

Tang, D., Tran, Y., Dawes, P. & Gopinath, B. A narrative review of lifestyle risk factors and the role of oxidative stress in age-related hearing loss. Antioxidants 12, 878 (2023).

Han, S. Y., Seo, H. W., Lee, S. H. & Chung, J. H. The association between tooth loss and hearing impairment: Partial compensation with dental implants. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 21, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.5152/iao.2025.241786 (2025).

Watarai, G. et al. Relationship between age-related hearing loss and consumption of coffee and tea. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 23, 453–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.14589 (2023).

Hendriks, H. F. J. Alcohol and human health: What is the evidence?. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 11, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-food-032519-051827 (2020).

Piano, M. R. et al. Alcohol use and cardiovascular disease: A scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 152, e7–e21. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001341 (2025).

Popelka, M. M. et al. Moderate alcohol consumption and hearing loss: A protective effect. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 48, 1273–1278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb02601.x (2000).

Itoh, A. et al. Smoking and drinking habits as risk factors for hearing loss in the elderly: Epidemiological study of subjects undergoing routine health checks in Aichi, Japan. Public Health 115, 192–196. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ph.1900765 (2001).

Gopinath, B. et al. The effects of smoking and alcohol consumption on age-related hearing loss: The blue mountains hearing study. Ear Hear. 31, 277–282. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181c8e902 (2010).

Curhan, S. G., Eavey, R., Shargorodsky, J. & Curhan, G. C. Prospective study of alcohol use and hearing loss in men. Ear Hear. 32, 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181f46a2f (2011).

Dawes, P. et al. Cigarette smoking, passive smoking, alcohol consumption, and hearing loss. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 15, 663–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10162-014-0461-0 (2014).

Rehm, J. The risks associated with alcohol use and alcoholism. Alcohol. Res. Health 34, 135–143 (2011).

Qian, P. et al. Alcohol as a risk factor for hearing loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 18, e0280641. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280641 (2023).

Rim, H. S. et al. Association of metabolic syndrome with sensorineural hearing loss. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10214866 (2021).

Yévenes-Briones, H., Caballero, F. F., Banegas, J. R., Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. & Lopez-Garcia, E. Association of lifestyle behaviors with hearing loss: The UK biobank cohort study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 97, 2040–2049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.03.029 (2022).

Hozawa, A. et al. Study profile of the tohoku medical megabank community-based Cohort study. J. Epidemiol. 31, 65–76. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20190271 (2021).

Olusanya, B. O., Davis, A. C. & Hoffman, H. J. Hearing loss grades and the International classification of functioning, disability and health. Bull. World Health Organ. 97, 725–728. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.19.230367 (2019).

Clark, J. G. Uses and abuses of hearing loss classification. ASHA 23, 493–500 (1981).

Kogure, M. et al. Multiple measurements of the urinary sodium-to-potassium ratio strongly related home hypertension: TMM Cohort study. Hypertens. Res. 43, 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0335-2 (2020).

Greaves, L., Poole, N. & Brabete, A. C. Sex, gender, and alcohol use: Implications for women and low-risk drinking guidelines. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084523 (2022).

Jones, D. W. et al. AHA/ACC/AANP/AAPA/ABC/ACCP/ACPM/AGS/AMA/ASPC/NMA/PCNA/SGIM guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation and management of high blood pressure in adults: A report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension 82, e212–e316. https://doi.org/10.1161/hyp.0000000000000249 (2025).

Koyanagi, Y. N. et al. Genetic architecture of alcohol consumption identified by a genotype-stratified GWAS and impact on esophageal cancer risk in Japanese people. Sci. Adv. 10, eade2780. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ade2780 (2024).

Fuse, N. et al. Genome-wide association study of axial length in population-based cohorts in Japan: The tohoku medical megabank organization eye study. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2, 100113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xops.2022.100113 (2022).

Fulton, S. E., Lister, J. J., Bush, A. L., Edwards, J. D. & Andel, R. Mechanisms of the hearing-cognition relationship. Semin. Hear. 36, 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1555117 (2015).

Kiely, K. M., Gopinath, B., Mitchell, P., Luszcz, M. & Anstey, K. J. Cognitive, health, and sociodemographic predictors of longitudinal decline in hearing acuity among older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 67, 997–1003. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gls066 (2012).

Deal, J. A. et al. Hearing impairment and incident dementia and cognitive decline in older adults: The health ABC study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 72, 703–709. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glw069 (2017).

Conigrave, K. M., Davies, P., Haber, P. & Whitfield, J. B. Traditional markers of excessive alcohol use. Addiction 98(Suppl 2), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1359-6357.2003.00581.x (2003).

Murakami, K. et al. Validity and reproducibility of food group intakes in a self-administered food frequency questionnaire for genomic and omics research: The Tohoku medical megabank project. J. Epidemiol. 35, 109–117. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20240064 (2025).

Fransen, E. et al. Occupational noise, smoking, and a high body mass index are risk factors for age-related hearing impairment and moderate alcohol consumption is protective: A European population-based multicenter study. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 9, 264–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10162-008-0123-1 (2008).

Brant, L. J. et al. Risk factors related to age-associated hearing loss in the speech frequencies. J. Am. Acad. Audiol. 7, 152–160 (1996).

Piano, M. R. Alcohol’s effects on the cardiovascular system. Alcohol. Res. 38, 219–241 (2017).

Samocha-Bonet, D., Wu, B. & Ryugo, D. K. Diabetes mellitus and hearing loss: A review. Ageing Res. Rev. 71, 101423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2021.101423 (2021).

Dorgan, J. F. et al. Serum hormones and the alcohol-breast cancer association in postmenopausal women. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 93, 710–715. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/93.9.710 (2001).

Delhez, A., Lefebvre, P., Péqueux, C., Malgrange, B. & Delacroix, L. Auditory function and dysfunction: Estrogen makes a difference. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 77, 619–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-019-03295-y (2020).

Matoba, N. et al. GWAS of 165,084 Japanese individuals identified nine loci associated with dietary habits. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4, 308–316. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0805-1 (2020).

Edenberg, H. J. & McClintick, J. N. Alcohol dehydrogenases, aldehyde dehydrogenases, and alcohol use disorders: A critical review. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 42, 2281–2297. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.13904 (2018).

Du, X. Y. et al. Association between the aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 rs671 G> a polymorphism and head and neck cancer susceptibility: A meta-analysis in east asians. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 45, 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14527 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. GOT2 silencing promotes reprogramming of glutamine metabolism and sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma to glutaminase inhibitors. Cancer Res. 82, 3223–3235. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-22-0042 (2022).

Kanai, M. et al. Genetic analysis of quantitative traits in the Japanese population links cell types to complex human diseases. Nat. Genet. 50, 390–400. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0047-6 (2018).

Wiet, G. J., Godfrey, D. A., Rubio, J. A. & Ross, C. D. Quantitative distributions of aspartate aminotransferase and glutaminase activities in the guinea pig cochlea. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 99, 353–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348949009900507 (1990).

Stagos, D. et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1B1: Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel mitochondrial acetaldehyde-metabolizing enzyme. Drug Metab. Dispos. 38, 1679–1687. https://doi.org/10.1124/dmd.110.034678 (2010).

Spankovich, C. & Le Prell, C. G. Healthy diets, healthy hearing: National health and nutrition examination survey, 1999–2002. Int. J. Audiol. 52, 369–376. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2013.780133 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This research used the supercomputer system provided by Tohoku Medical Megabank Project (funded by AMED under Grant Number JP21tm0424601). We thank the members of the Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization, including the Genome Medical Research Coordinators and the office and administrative personnel for their cooperation. We are grateful to all the study participants, participating medical institutions, and staff involved in the TMM CommCohort Study and TMM BirThree Cohort Study. We also thank the Consortium for the integrated analysis of genomic, medical, and health information for supporting the WGS data of Tohoku Medical Megabank. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for the English language editing.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number: JP23KK0156). It was also supported by the Osake-no-Kagaku Foundation and Daiwa Securities Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: HT and JS. Data analysis: HT, JS, INM, MS, YK, GW, HT, TK, YH, RI, AH, and NF. Cohort organization: MK, NN, TO, AH, and SK. Biobank organization: KK. The draft of the manuscript was written by HT and JS. Supervision of research: MY and YK. All authors read and reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

JS received research grants from the Osake-no-Kagaku Foundation and Daiwa Securities Foundation. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethical Research Committee of Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicines, with the ethics code 2024-1-929. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Takahashi, H., Suzuki, J., Motoike, I.N. et al. Relationship between age-related hearing loss and alcohol consumption in a Japanese population. Sci Rep 16, 336 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29634-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29634-7