Abstract

Nitrate contamination from agricultural and industrial activities poses significant risks to human health and aquatic ecosystems. Biochar, particularly when chemically modified, has emerged as a sustainable and effective adsorbent; however, the influence of modification sequence and operational conditions on nitrate removal is not fully understood. In this study, rapeseed (Brassica napus L.)-derived biochars were modified with aluminum through three distinct pathways: pre-pyrolysis (MP), post-pyrolysis (PM), and post-pyrolysis with re-pyrolysis (PMP). Comprehensive characterization using BET, SEM, EDS, XRD, and FTIR showed that PM biochar exhibited the highest surface area, uniform mesoporous structure, stable aluminum content, and abundant oxygen-containing functional groups, resulting in superior nitrate adsorption. Batch experiments demonstrated that adsorption efficiency is strongly affected by operational parameters, including initial nitrate concentration, contact time, adsorbent dose, solution pH, and the presence of competing anions, with CO₃2⁻ and SO₄2⁻ having the strongest inhibitory effects. Regeneration tests indicated that PM biochar retained ~ 76% of its initial adsorption capacity after five adsorption–desorption cycles, confirming its reusability. Nonlinear machine learning models, including Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Linear Regression (LR), were applied to predict nitrate removal, with RF achieving the highest predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.892, RMSE = 0.078), demonstrating robustness and generalization. This work highlights the critical role of modification sequence in tailoring biochar structure and functionality and integrates AI-based modeling to provide a data-driven framework for designing high-performance biochars for sustainable nitrate removal from water.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitrate contamination of aquatic environments has emerged as a serious global issue over recent decades, primarily due to intensive farming, industrial effluents, and inadequate waste disposal1,2. Elevated nitrate levels in drinking water pose significant health risks, including methemoglobinemia, thyroid disorders, and increased cancer probability through the formation of N–nitroso compounds3,4. These consequences emphasize the need for efficient, sustainable, and low–cost nitrate removal technologies. Conventional methods include biological denitrification, ion exchange, reverse osmosis, electrodialysis, and chemical reduction5,6,7,8,9. While effective in certain scenarios, these approaches often involve high operational costs, energy consumption, or secondary pollution10. In contrast, Adsorption is recognized as an efficient and promising method for removing pollutants such as nitrate from wastewater due to its operational simplicity, cost-effectiveness, environmental compatibility, and potential for regeneration and reuse11,12. Among various adsorbents, biochar—a carbonaceous material produced by pyrolysis of biomass under limited oxygen conditions—has garnered significant attention as an efficient and suitable adsorbent for resource recycling in environmental applications due to its high specific surface area, abundant functional groups, low production cost, high cation exchange capacity, and potential use as a fertilizer after nitrogen adsorption13. The adsorption mechanisms of biochar include pore diffusion, ionic interactions, and hydrogen bonding, while similar adsorbents like hydrochar exhibit comparable performance in pollutant removal due to their hydrophilic functional groups and high carbon content11,12. However, pristine biochar generally exhibits limited efficiency for nitrate adsorption, primarily because of its negatively charged surface and absence of anion–attracting functional groups14,15. This inherent limitation has motivated researchers to explore various chemical and structural modifications of biochar to enhance its affinity for nitrate ions16. One of the most effective modification strategies involves the incorporation of metal elements, such as iron (Fe), magnesium (Mg), or Aluminum (Al).

Numerous studies have investigated metal modifications to enhance the nitrate adsorption capacity of biochar. For instance, Long, et al.17 demonstrated that iron impregnation improves nitrate removal through enhanced electrostatic interactions and the presence of functional groups. Similarly18, reported superior performance of Mg/Al-modified biochar, attributed to electrostatic attraction and the formation of metal–ligand bridges19, found that protonated Fe-based biochar significantly increased nitrate removal due to stronger electrostatic forces and the enrichment of surface hydroxyl groups. Al has shown promising results in enhancing the anion adsorption capacity of biochar due to its high charge density, affinity for oxygen–containing groups, and stability in aqueous environments.

Several studies have investigated Al-modified biochars for pollutant removal. For instance, Tran, et al.20, demonstrated that Al-modified biochars significantly enhanced phosphate removal through electrostatic interactions and surface functional groups. Similarly, Choi, et al.21, reported superior adsorption performance of Al-impregnated kenaf biochar. Yin, et al.22 also found that Al modification improved the removal efficiency of both phosphate and nitrate ions.

Previous studies have often focused on a single approach to Al incorporation–typically conducted either before or after pyrolysis–and few have compared the effects of different modification sequences. To address this gap, the present study systematically examines three Al-modification routes for rapeseed (Brassica napus) biomass: loading before pyrolysis (pre-modification), loading after pyrolysis (post-modification), and post-modified biochar subjected to an additional thermal treatment (re-pyrolysis). This study provides a comprehensive comparison of Al- modification strategies and elucidates how the timing and sequence of Al incorporation affects surface morphology, functional groups, and overall adsorption performance.

Beyond experimental investigations, predicting adsorption behavior using machine learning (ML) models has emerged as a powerful approach to identify key parameters controlling pollutant removal by modified biochars. For example, Ullah, et al.23 employed machine learning models, including RF, to predict biochar adsorption capacity and identified reaction pH, initial concentration, and pyrolysis temperature as key factors influencing adsorption efficiency.

Fu, et al.24 used machine learning to predict phosphate adsorption by metal-modified biochar and identified metal load, solid–liquid ratio, and pH as key factors. Unlike previous studies that primarily focused on performance enhancement, this work provides new insights into the transformation and coordination behavior of Al species under different modification sequences. By systematically comparing pre-, post-, and re-pyrolysis modifications, the study elucidates how the timing of Al incorporation governs the structural evolution, surface functionality, and adsorption mechanisms of biochar, offering a mechanistic understanding that has not been explicitly reported before. This study involved the preparation and chemical modification of biochar derived from rapeseed biomass using various Al–based methods. The impact of different modification strategies on nitrate adsorption efficiency was evaluated, and the optimal biochar was selected for subsequent experiments. Morphological, structural, and surface area characterization of the biochars was conducted using scanning electron microscope (SEM), energy–dispersive X–ray spectroscope (EDS), X–ray diffraction (XRD), Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET), and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to explain the superior performance of the optimal biochar. Experimental nitrate adsorption data under varying operational conditions were processed using the Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC) to remove redundant features, followed by normalization and division into training and testing sets for machine learning (ML) models Forest (RF), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Linear Regression (LR) Feature importance and sensitivity analyses were performed using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and Permutation Importance (PI), and model performance was re–evaluated after reducing the number of input variables. Finally, the accuracy and reliability of the predictive models were assessed using standard regression metrics.

Materials and methods

Biochar production and characterization

Biochar was prepared from rapeseed (Brassica napus L.), an important crop in Iran with abundant agricultural residues. Stems were collected from the research farm of Lorestan University, washed, air-dried, and ground to particles smaller than 2 mm.

Three distinct Al–modified biochars were synthesized through the following pretreatment pathways:

-

(1) the biomass was first impregnated with Al and then pyrolyzed at 550 °C (MP biochar);

-

(2) the biomass was initially pyrolyzed at 550 °C and subsequently modified with Al (PM biochar).

-

(3) the biomass underwent an initial pyrolysis, followed by Al modification, and then a second pyrolysis at 550 °C (PMP biochar). The chemical modification was conducted based on the method Yin, et al.25.

The morphological features of the biochars were characterized using SEM equipped with EDS. The crystalline structure was analyzed using XRD. The elemental composition and specific surface area were measured using the BET method, and surface functional groups were identified using FTIR spectroscopy.

Nitrate adsorption

A nitrate stock solution (1000 mg L⁻1) was prepared using potassium nitrate (KNO₃). Batch adsorption experiments were carried out at room temperature (21 ± 1 °C) to assess the nitrate removal efficiency of the biochars. The effect of pH on nitrate adsorption was investigated over a pH range of 2 to 11, employing an adsorbent dosage of 0.01 g L⁻1, a contact time of 24 h, and an agitation speed of 150 rpm. To determine the equilibrium contact time, adsorption tests were performed with contact times varying from 5 min to 24 h at natural pH, using an adsorbent dosage of 0.01 g L⁻1 and agitation at 150 rpm. The influence of adsorbent dosage on nitrate removal was evaluated by conducting experiments with biochar concentrations ranging from 0.01 to 10 g L⁻1 under natural pH conditions, a contact time of 24 h, and an agitation speed of 150. To simulate more realistic environmental conditions, where multiple anions are present, the effect of competing ions on nitrate adsorption was examined. The influence of chloride (Cl⁻), phosphate (PO₄3⁻), carbonate (CO₃2⁻), and sulfate (SO₄2⁻) ions was tested at concentrations of 10, 50 and 100 mg L⁻1 under the same experimental conditions (adsorbent dosage of 0.01 g L⁻1, contact time of 24 h, and agitation speed of 150 rpm). This approach allowed for the assessment of the effect of coexisting anions on nitrate adsorption efficiency, providing insight into the performance of biochars under conditions closer to groundwater or wastewater.

The removal percentage (R%) of the nitrate of biochar was calculated using Eq. (1) 26:

where:

R: Adsorption removal (%).

\({C}_{i} and {C}_{e}\): Initial and equilibrium nitrate concentrations (mg L⁻1).

Regeneration and reusability of biochar

The reusability of the spent rapeseed biochar after nitrate adsorption was evaluated through sequential adsorption–desorption cycles. The spent biochar was immersed in 1 M NaOH solution for 480 min at room temperature under shaking at 150 rpm. The alkaline environment facilitated nitrate desorption by weakening electrostatic interactions between nitrate ions and the biochar surface. After regeneration, the biochar was washed with deionized water until neutral pH (~ 7) and dried at 50 °C. The regenerated biochar was then reused under the same conditions as the initial adsorption test. This cycle was repeated five times, and the final nitrate concentration (Cₑ) after each cycle was measured to assess the recovery of adsorption capacity. The procedure was applied to the biochar showing the highest adsorption performance in preliminary tests.

Data Processing and predictive modeling

The dataset used in this study consists of experimental measurements related to nitrate adsorption efficiency obtained under varying operational conditions, including pH, contact time, initial nitrate concentration, and adsorbent dose.

In the data preprocessing stage, the PCC was used to measure the correlation between features, helping to identify and remove redundant or highly similar inputs13,27,28. PCC is a statistical measure that quantifies the linear correlation between two variables. It is calculated as follows:

where \(r\) represents the correlation coefficient between two variables, and \(\overline{x }\) and \(\overline{y }\) denote the mean values of variables x and y, respectively.

Due to differences in the range of feature values, both the input and output variables were normalized before training the machine learning models. Normalization eliminates differences in scale and magnitude among features, facilitating faster algorithm convergence and improved predictive performance29. The normalization process is expressed as:

where \({\text{x}}_{i}^{*}\) and \({x}_{i}\) are the normalized and original values of the input variable, respectively, and \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\) represent the mean and standard deviation of the variable.

Model development and validation procedure

To ensure reliable and unbiased prediction of nitrate adsorption efficiency, a streamlined, multi-level validation framework was implemented, integrating dataset preparation, model training, and rigorous statistical evaluation.

Data preparation and variables

The dataset was compiled from a series of batch adsorption experiments and subsequently expanded to n = 50 samples by incorporating additional measurements conducted under competitive ion conditions. Five experimental input variables– pH, contact time (min), initial nitrate concentration (mg L⁻1), competitive anion concentration (mg L⁻1), and adsorbent dose (g L⁻1)– were employed to predict the target variable, adsorption efficiency (%). All variables were standardized using the StandardScaler function in Scikit-learn to ensure numerical stability and enhance model convergence.

Model algorithms and implementation

To construct robust predictive models for the biochar dataset, three machine learning algorithms were employed: RF, SVR, and LR. RF is an ensemble learning approach, constructs multiple decision trees during training and outputs their average prediction, enhancing model robustness and reducing overfitting. SVR, a kernel-based regression technique, fits an optimal hyperplane within a specified margin of tolerance, effectively capturing complex nonlinear relationships in the data. In contrast, LR is a simple baseline model that assumes a linear relationship between input and output variables. Hyperparameter tuning was performed via GridSearch CV with fivefold inner cross-validation.

Integrated validation framework

A unified, three-tier validation strategy was applied to maximize generalizability and minimize bias:

k-Fold Cross-Validation (k-fold CV) (k = 5): The dataset was randomly partitioned into k folds; each fold served once as the test set. Mean R2 ± standard deviation quantified performance and consistency.

Nested Cross-Validation (NCV): Applied as the gold standard for unbiased generalization. The outer loop evaluated model performance on independent folds, while the inner loop optimized hyperparameters– fully decoupling tuning from testing.

100-Iteration Bootstrapping: Random resampling with replacement was repeated 100 times. Each bootstrap sample was used to retrain and evaluate the models, yielding a distribution of R2 values to assess robustness against sampling variability.

This integrated approach– combining k-fold CV, NCV, and bootstrapping– provided comprehensive, statistically sound evidence of model reliability, effectively simulating performance on independent data despite the modest dataset size.

Feature importance and sensitivity analysis

To identify the most influential operational parameters affecting nitrate adsorption efficiency, feature importance analysis was performed using two complementary approaches. SHAP, based on cooperative game theory, quantifies each input feature’s contribution to the model’s predictions via Shapley values, enabling both global interpretation (average effect across the dataset) and local interpretation (impact on individual predictions)30. PI is a model-agnostic method that evaluates the drop in predictive performance when a feature’s values are randomly permuted while keeping all other features constant; a larger drop indicates higher importance. Using the identified key features, the studied models were re-evaluated after removing less important variables. This approach assesses whether focusing on the most influential parameters can maintain or even improve predictive performance while simplifying the input.

Model performance evaluation metrics

To assess the accuracy and reliability of the predictive models, the following standard regression metrics were used31.

Coefficient of Determination (R2): Quantifies the proportion of variance in the observed data explained by the model, reflecting the goodness of fit.

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): Represents the square root of the average squared differences between predicted and observed values, indicating the typical magnitude of prediction errors.

Here, \({Y}_{i}^{pred}\) and \({Y}_{i}^{exp}\) represent the predicted and experimental values for the i–th observation, respectively. \({Y}_{ave}^{exp}\) denotes the meaning of the experimental values, and n is the total number of observations.

Results and discussion

Characterization of structural features in al–modified biochars

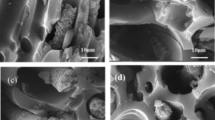

To investigate the surface characteristics and structural properties of the synthesized Al–modified biochars (MP, PM, and PMP), several characterization techniques were employed. SEM was used to examine the surface morphology and pore structure of the biochars (Fig. 1), revealing differences in sheet arrangement, particle size, and porosity. XRD analysis provided insights into the crystalline and amorphous phases of the samples (Figs. 2–4), highlighting the presence of Al and Al(OH)₃ phases that influence surface reactivity. N₂ adsorption–desorption isotherms were analyzed using the BET method to determine the specific surface area, pore volume, and average pore diameter (Fig. 5), reflecting the accessible surface area available for adsorption. EDS was employed to determine elemental composition and surface functionalization (Fig. 6), confirming the incorporation of Al species and oxygen-containing groups that enhance adsorption capacity. Additionally, FTIR spectroscopy was conducted to identify the functional groups present on the biochar surfaces (Fig. 7).

In general, the combination of SEM, XRD, BET, EDS, and FTIR characterizations provided a comprehensive understanding of how different modification routes influence the structural features and nitrate adsorption performance of the biochars.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The surface morphology of the synthesized biochars (MP, PM, and PMP) is presented in Fig. 1. Figure 1(a) corresponds to the MP sample, in which Al was introduced prior to pyrolysis. This sample exhibits thin, curved sheets or layers with relatively coarse micrometer-sized pores, as well as a smooth surface with distinct sheet edges and large pores, indicative of a macroporous to mesoporous structure. Overall, a more integrated morphology resembling a layered framework is observed32,33. During pyrolysis, aluminum salts are converted into aluminum oxides/hydroxides, which can act as carbonization catalysts, promoting the stabilization of the carbon matrix. This process leads to a relatively uniform distribution of aluminum microphases and the formation of a larger pore framework, resulting in large sheets with micrometer-scale pores. The penetration of Al into the matrix may also help prevent complete structural collapse at elevated temperatures34. However, the irregular pore distribution and increased pore size reduce the effective surface area available for nitrate adsorption, thereby limiting its adsorption efficiency.

In contrast, the PM sample– prepared by pyrolysis followed by Al modification (Fig. 1(b)), exhibits angular and planar fragments covered with fine particles, giving the surface a “fractured or powdered” appearance with dense particle accumulation on the planar regions. This morphology indicates the deposition of particles onto the surface of a pre-pyrolyzed biochar. When the preformed biochar is immersed in an aluminum salt solution and subsequently dried and heated, aluminum typically precipitates as hydroxide or oxide particles or clusters on the biochar surface35. The fine particles coating the surface represent crystalline flakes or clusters formed on the carbon sheets. Although the pore diameter decreases in this case, the number of accessible Al–OH surface sites increase, thereby enhancing the anion adsorption capacity36,37. This structural arrangement not only improved surface accessibility but also increased the number of active sites, resulting in enhanced adsorption efficiency. The superior nitrate removal observed in the PM sample further supports this interpretation. The PMP sample, although structurally like PM, underwent an additional pyrolysis step after Al modification as shown in Fig. 1(c), it exhibits a highly crushed and flaky or fluffy structure composed of small particles and fine flakes, with a higher particle density and a more discontinuous distribution of interparticle spaces. After Al deposition on the surface, the subsequent repyrolysis induces phase transformations (dehydroxylation) and converts aluminum hydroxides into more stable oxides, such as Al₂O₃ or amorphous alumina. Meanwhile, the repyrolysis process may also remove residual organic deposits and partially unblock pores, thereby restoring some degree of porosity.

These findings are consistent with previous studies. For example, Li, et al.38 reported that Fe– and Mn–modified biochars developed rougher surfaces with higher densities of adsorption sites due to metal oxide loading, while Hashimi, et al.37 confirmed the presence of Al hydroxide/oxide layers that contributed to surface roughness. Similarly, Tran, et al.20 and Yin, et al.22 demonstrated that Al loading plays a decisive role in pore development, where higher concentrations of Al salts promote wider pore channels and increased roughness, but excessive loading may compromise pore density. Taken together, the results highlight the pivotal role of process sequencing in tailoring the physicochemical properties of Al–modified biochars. Specifically, post–pyrolysis modification (PM) proved to be the most effective strategy for producing biochars with optimized surface morphology, uniform pore distribution, and enhanced adsorption capacity. In contrast, pre–pyrolysis modification (MP) hindered the development of a stable porous network, while re–pyrolysis after modification (PMP) induced partial structural collapse. Therefore, pyrolysis followed by Al modification emerges as the most promising route for designing high–performance biochar adsorbents for nitrate removal from water.

X–ray diffraction (XRD)

XRD analysis was conducted to identify the crystalline phases and evaluate the structural evolution of the Al-modified biochars, namely MP (Fig. 2), PM (Fig. 3), and PMP (Fig. 4). The main crystalline phases identified in the Al-modified biochars (PM and PMP) included α-Al₂O₃ (PDF 00–046-1212), AlOOH (PDF 00–021-1307), KCl (PDF 00–004-0587), and SiO₂ (PDF 00–005-0628). However, for the MP sample, the XRD pattern exhibits a broad, featureless hump centered at approximately 2θ ≈ 24°, characteristic of predominantly amorphous carbon39. The absence of sharp diffraction peaks indicates low crystallinity and the lack of detectable crystalline Al-bearing phases, implying a limited number of surface-active sites for nitrate adsorption. This amorphous structure reflects incomplete carbonization and a predominance of disordered cellulose-derived carbon, which restricts electron mobility and ion-exchange capacity. Accordingly, MP displayed relatively low nitrate removal efficiency (45.90%), consistent with its structural limitations. In contrast, the PM biochar (Fig. 3) exhibits several sharp and intense peaks at 2θ ≈ 38.4°, 45.5°, 65°, and 78°, corresponding to crystalline alumina (Al₂O₃) and aluminum hydroxide (Al(OH)₃) phases. These peaks confirm the successful incorporation and stabilization of Al species within the carbon matrix, enhancing both crystallinity and the density of active surface sites. The increased α-Al₂O₃ content provides abundant Lewis acid sites and surface hydroxyl groups (Al–OH) that facilitate electrostatic attraction and chemisorption interactions with nitrate ions. Moreover, the reduction in amorphous carbon improves thermal stability and adsorption performance1. Accordingly, PM achieved the highest nitrate removal efficiency (70.67%).

The PMP biochar (Fig. 4), subjected to an additional pyrolysis step after Al modification, presents a mixture of amorphous and crystalline features. Although crystalline reflections like those of PM are observed, the persistence of an amorphous background indicates partial reorganization or layered structures that may hinder full accessibility of the adsorption sites. This hybrid structure suggests that secondary pyrolysis promotes partial dehydroxylation and conversion of Al hydroxides into more stable oxides, while retaining some disordered carbon. During the modification process, Al ions can also chemically interact with oxygen-containing surface groups, generating new active functionalities capable of forming complexes with nitrate ions or other anions40. The intermediate crystallinity of PMP corresponds to a moderate nitrate removal efficiency (51.95%).

Overall, these results demonstrate a strong correlation between the structural characteristics and adsorption behavior of the Al-modified biochars. Higher crystallinity and uniform distribution of Al phases (especially α-Al₂O₃ and AlOOH) enhance nitrate adsorption through electrostatic and chemisorption mechanisms, whereas residual amorphous carbon limits active site availability. Secondary crystalline phases such as KCl and SiO₂ contribute to the physical stability of the biochar but play a negligible role in nitrate removal.

Brunauer–emmett–teller (BET)

The surface and structural properties of the synthesized biochars (MP, PM, and PMP) were systematically evaluated using N₂ adsorption–desorption isotherms. The key parameters, including monolayer adsorption volume (Vm), Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area, total pore volume, and average pore diameter, are presented in Fig. 5.

Among the three biochars, the PM sample demonstrated the most favorable physicochemical characteristics, with the highest BET surface area (259.80 m2/g) and Vm (59.69 cm3/g). These values reflect a high density of adsorption sites and extensive active surface area for nitrate uptake. In comparison, MP exhibited negligible BET surface area and Vm, implying either a collapsed porous structure or blocked active sites. The PMP sample showed a relatively large total pore volume (0.27 cm3/g) but moderate BET surface area (194.85 m2/g) and Vm (44.77 cm3/g), indicating that its more open structure was not sufficiently functionalized to enhance nitrate binding.

With respect to pore size, PM displayed the smallest average pore diameter (2.89 nm), falling within the mesoporous range, which is optimal for nitrate diffusion and retention16. In contrast, MP and PMP exhibited larger pore diameters (5.77 and 4.33 nm, respectively), which may facilitate faster ion transport but do not compensate for the lack of surface functionality. These findings emphasize that optimal adsorption is not governed solely by pore size but rather by the synergistic effects of high surface area, suitable pore distribution, and chemical modification.

The preparation sequence was found to play a critical role in determining surface and structural properties. As illustrated in the radar chart (Fig. 5), MP–prepared by Al modification before pyrolysis–showed nearly zero values across all parameters. This suggests that the subsequent pyrolysis step likely destroyed or deactivated the Al–functionalized sites, preventing the development of a porous structure. Conversely, PM–pyrolyzed prior to Al modification–exhibited the highest BET surface area, total pore volume, and monolayer capacity. This improvement can be attributed to the formation of a stable porous carbon matrix during pyrolysis, which was subsequently functionalized by Al species. Such a structure provides abundant accessible adsorption sites and favorable electrostatic interactions with nitrate ions. The PMP sample, subjected to additional pyrolysis after modification, exhibited reduced BET surface area and pore volume, indicating that the second thermal treatment may have caused partial collapse or restructuring of the modified surface. These findings are consistent with previous reports. Tran Tran, et al.20, demonstrated that Al chloride modification of Mimosa pigra biochar significantly increased BET surface area and pore volume. Similarly, Bansal Bansal and Pal16 reported that the deposition of Mg–Al layers on chitosan improved surface area, pore diameter, and pore volume, enhancing adsorption capacity. Addich, et al.5 also observed that Mg/Fe modification of biochar increased surface roughness and pore heterogeneity through metal oxide deposition, which in turn promoted pollutant adsorption. Collectively, these studies and the present findings highlight that metal–assisted modification, combined with controlled pyrolysis, plays a crucial role in tailoring biochar structure for optimized adsorption performance.

Overall, the PM biochar–prepared by pyrolysis followed by Al modification–achieved the best balance of surface area, pore structure, and chemical functionality. This preparation sequence preserved functional groups, stabilized the porous network, and maximized nitrate adsorption efficiency, confirming that post–pyrolysis modification is a promising strategy for designing high–performance biochar–based adsorbents in water treatment applications.

Energy dispersive X–ray spectroscopy (EDS)

The elemental composition of Al–modified biochars (MP, PM, and PMP) was analyzed using EDS (Fig. 6). Although all samples underwent Al modification, their final compositions differed significantly due to the sequence of Al treatment and pyrolysis. The EDS spectra showed that PM biochar contained the highest Al content (17.67%), followed by PMP (14.50%), whereas Al was undetectable in the MP sample (0%). Carbon remained the dominant element across all samples; however, its relative proportion decreased with increasing Al content– from 60.97% in MP to 34.56% in PM and 27.73% in PMP. Conversely, oxygen content increased from ~ 24% in MP to 39.01% in PM and ~ 50% in PMP.

These findings highlight the critical role of process sequencing. In MP, where Al was introduced before pyrolysis, the absence of detectable Al suggests decomposition or volatilization of Al salts during thermal treatment, or possible entrapment within the carbon matrix, leading to heterogeneous distribution and limited surface detectability by EDS. Non-detection does not necessarily confirm the complete absence of Al. This resulted in a carbon-rich biochar with low inorganic content and limited surface-active sites for nitrate adsorption. In contrast, PM biochar, modified post-pyrolysis, retained the highest Al content, indicating that post-pyrolysis modification is the most effective for Al immobilization. The concurrent reduction in carbon and increase in oxygen suggest successful deposition of Al compounds and formation of oxygen-containing functional groups, enhancing electrostatic interactions and adsorption capacity41. PMP biochar, subjected to a three-step process (pyrolysis, Al modification, and second pyrolysis), retained significant Al (14.50%), though less than PM. This reduction likely stems from structural rearrangements or partial degradation of Al species during the second pyrolysis. However, PMP’s high oxygen content (~ 50%) indicates enriched oxygenated surface functionalities, supporting adsorption despite partial Al loss. Overall, the processing sequence significantly influenced the elemental composition and surface chemistry of Al-modified biochars. Post-pyrolysis modification (PM) proved most effective for Al retention and functionalization, yielding a biochar with an optimal balance of carbon, Al, and oxygen. This approach enhances surface chemistry and functional groups, making PM the most promising candidate for nitrate removal. EDS analyses further confirmed that in PM and PMP biochars, metallic elements existed as metal oxides on the surface, increasing roughness, porosity, and ion exchange capacity, thereby improving adsorption efficiency42,43. Previous studies corroborate these findings. For example, Yin, et al.25 synthesized biochars from soybean straw and subsequently modified them with Al and magnesium. This modification led to increased O/C, H/C, and (O + N)/C ratios, reflecting a higher abundance of oxygen–containing functional groups and enhanced adsorption capacity. Similarly, Wang, et al.18 observed that hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), magnesium (Mg), and Al (Al) contents increased in biochars derived from apple branches following Mg/Al–LDH modification. The incorporation of these LDHs enriched the biochars with Mg, Al, and OH groups while reducing carbon content, thereby improving surface functionality and adsorption performance.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

The FTIR results are shown in Fig. 7. The spectra of the three biochar samples (MP, PM, and PMP) were recorded in the 400–4000 cm⁻1 range in absorbance mode to identify their surface functional groups. The FTIR spectra clearly demonstrates that the sequence of aluminum modification and pyrolysis significantly influences the chemical structure and surface functionality of the resulting biochars. Despite identical pyrolysis temperatures, the observed differences in FTIR spectra, EDS data (C, O, Al contents), and nitrate adsorption performance can be attributed solely to the process sequence. In the MP sample, the disappearance of Al–O vibrations (800–500 cm⁻1) and the weak absorption of O–H (≈3400 cm⁻1) and C–O (≈1100 cm⁻1) bands indicate a highly carbonized structure with minimal oxygenated groups. The absence of Al in EDS confirms that aluminum species were decomposed or volatilized during thermal treatment. Nevertheless, the transient presence of Al3⁺ ions during heating may have catalyzed dehydration and aromatization reactions, producing the most condensed carbon framework and the lowest O/C ratio among the samples. In contrast, the PM sample exhibited distinct Al–O peaks and pronounced nitrate-related absorption around 1380 cm⁻1. The porous carbon surface generated during the initial pyrolysis provided abundant oxygenated sites that facilitated Al immobilization via surface complexation, forming stable Al–O bonds. These Lewis acidic sites acted as effective anion-binding centers, explaining the highest nitrate adsorption capacity observed in this sample.

The PMP sample displayed the strongest O–H and C–O absorptions despite undergoing two thermal treatments. This suggests that the second pyrolysis partially disrupted Al–O bonds and induced re-oxidation of the carbon matrix, resulting in the highest O/C ratio. Subsequent cooling and exposure to air likely facilitated the re-formation of hydroxyl groups, producing a more hydrophilic surface reminiscent of low-temperature biochars.

Overall, these findings underscore that the sequence of modification and pyrolysis critically determines the surface chemistry and adsorption behavior of Al-modified biochars. Pre-pyrolysis modification (MP) enhances structural stability but reduces surface reactivity due to Al loss; post-pyrolysis modification (PM) optimizes Al stabilization and nitrate adsorption; while re-pyrolysis (PMP) increases oxygenation but compromises structural integrity.

Influence of synthesis pathway on the kinetics and efficiency of nitrate adsorption by Al–modified biochars

The nitrate removal efficiency of three Al–modified biochars–PM, PMP, and MP–was systematically evaluated over contact times ranging from 0 to 1440 min. Among the tested adsorbents, PM exhibited the highest performance across all intervals, with removal efficiency increasing from 28% at 5 min to a maximum of 71.15% at 480 min, thereafter, stabilizing at approximately 70%. PMP showed a moderate adsorption capacity, with efficiency rising from 6% at 5 min to 51.95% at 1440 min. Although its initial adsorption rate was lower than that of PM, the removal steadily increased and approached equilibrium after 480 min. In contrast, MP demonstrated the lowest performance, with removal improving only from 3% at 5 min to 45.90% at 1440 min, reaching equilibrium around 480 min.

Nitrate adsorption in this study was governed by a combination of three primary mechanisms: surface adsorption (or interfacial adsorption), intraparticle diffusion, and electrostatic interactions. Surface adsorption mainly occurs on the external sites of the adsorbent and can be considered as weak physical interactions44.Given the mesoporous structure and abundant pore system of the modified biochars, nitrate ions–with a Stokes radius of 0.129 nm and a hydrated radius of 0.335 nm–were able to fully penetrate the porous framework. Moreover, Al surface modification introduced positive charges on the biochar surface, thereby enhancing electrostatic attraction toward the negatively charged NO₃⁻ anions45.

All three adsorbents followed a similar kinetic profile: a rapid initial uptake within the first hour due to occupation of readily available surface sites, followed by a slower approach to equilibrium, controlled primarily by diffusion into less accessible internal pores. This kinetic behavior highlights the direct impact of synthesis pathway on adsorption mechanisms (Fig. 8).

The superior performance of PM can be attributed to its favorable structural characteristics, particularly the highest BET surface area and total pore volume among the samples tested. In this case, Al modification after pyrolysis enabled the effective anchoring of active Al species onto the carbon framework without blocking mesopores or compromising pore structure, thereby maintaining both structural integrity and functional activity. PMP, which underwent a second pyrolysis after Al modification, retained a moderately porous structure; however, partial alteration or degradation of key surface functional groups essential for nitrate binding likely resulted in only moderate performance (~ 52%). In contrast, MP, which was modified prior to pyrolysis, showed the lowest nitrate removal (~ 46%), due to decomposition of Al salts and significant loss of surface area during thermal treatment. These results clearly demonstrate the critical role of synthesis sequence. Post–pyrolysis modification (PM) maximizes Al retention, maintains mesopores, and enriches functional groups, leading to superior nitrate adsorption. Pre–pyrolysis (MP) and dual–step modifications (PMP) were less effective in balancing surface chemistry and porosity.

Overall, the findings emphasize that the method and timing of biochar modification are decisive parameters influencing structural and functional properties. Optimizing these factors enables the development of highly effective adsorbents for nitrate removal and broader environmental remediation applications.

Extended study using the most effective biochar (PM)

Based on its superior nitrate removal performance, PM biochar was selected as the optimal adsorbent for further investigations. Subsequent experiments focused exclusively on PM to examine the effects of key operational parameters, including initial nitrate concentration, contact time, adsorbent dosage, competing anions, and pH, on removal efficiency. Additionally, artificial intelligence (AI) models were developed to predict adsorption behavior under varying conditions.

Effect of operational parameters on nitrate removal using PM biochar

The influence of operational parameters on nitrate adsorption by PM biochar was systematically investigated to assess the effects of different factors and to construct a reliable dataset for modeling and prediction of nitrate adsorption behavior. The results (Fig. 9) demonstrated that adsorption performance is strongly dependent on initial nitrate concentration, adsorbent dosage, contact time, and solution pH. At a constant pH of 6, increasing the initial nitrate concentration from 0 to 100 mg L⁻1 enhanced removal efficiency from 0% to ~ 70.7% when 0.01 g of adsorbent was used for 720 min. This improvement can be attributed to the intensified mass transfer driving force at higher concentrations, which promotes nitrate diffusion toward the adsorbent surface46. However, the removal decreased at higher concentrations, reflects the progressive saturation of active sites, in agreement with earlier studies on nitrate adsorption47. Adsorbent dosage also had a significant effect. At 100 mg L⁻1 initial nitrate and pH 6, removal increased steadily from ~ 70.7% to 84.5% as dosage rose from 0.01 g to 10 g. The enhancement arises from the greater number of active sites available for adsorption3,18. Nevertheless, the marginal improvement beyond 1–5 g suggests partial particle aggregation and surface overlap. The time–dependent adsorption profile revealed a biphasic pattern. At 100 mg L⁻1, 0.05 g dosage, and pH 6, removal rose rapidly from 28% at 5 min to ~ 71% at 480 min, after which it remained stable. The fast initial uptake corresponds to the occupation of abundant external sites under steep concentration gradients, while the subsequent slow approach to equilibrium reflects intraparticle diffusion resistance and progressive site saturation. Similar kinetic behavior has been documented for nitrate and other anionic contaminants on porous carbonaceous adsorbents25,48.

Experiments conducted under near-neutral conditions (pH 6–8) using the optimized biochar confirmed substantial nitrate removal (≈58–71%), indicating the adsorbent’s effectiveness under environmentally relevant conditions. These results align with previous studies demonstrating that nitrate adsorption by biochar is strongly influenced by solution pH, biochar modifications, and the presence of competing ions. Generally, adsorption efficiency is highest at acidic to near-neutral pH and decreases at higher pH values. For instance, modified sugarcane bagasse biochar exhibited maximum nitrate adsorption at pH 4.649, Fe–N-doped biochar showed optimal performance at pH 350, and acid-modified coffee grounds biochar demonstrated reduced nitrate removal under alkaline conditions51. These observations are consistent with the electrostatic attraction mechanism between nitrate ions and positively charged biochar surfaces, which can be enhanced through acid treatment or metal doping.

The inhibition ratios of competing anions (Cl⁻, CO₃2⁻, PO₄3⁻, and SO₄2⁻) on nitrate adsorption are shown in Fig. 9e. As the concentration of competing anions increased from 0 to 50 mg L⁻1, the inhibition ratio gradually rose, demonstrating a clear concentration-dependent suppression effect52. Quantitative analysis revealed inhibition ratios of 15.6%, 35.2%, 20.1%, and 34.5% for Cl⁻, CO₃2⁻, PO₄3⁻, and SO₄2⁻, respectively, at 50 mg L⁻1. Among these, CO₃2⁻ and SO₄2⁻ exhibited the strongest inhibition, whereas Cl⁻ showed the weakest.

SO₄2⁻) can compete more effectively for positively charged active sites on Al-modified biochar, forming outer-sphere complexes or participating in ion-exchange reactions that reduce nitrate uptake. In contrast, the monovalent Cl⁻ exhibited negligible competition due to its lower binding affinity and weaker electrostatic attraction. PO₄3⁻ displayed moderate inhibition, likely constrained by steric hindrance and specific coordination limitations despite its higher charge.

These results are consistent with previous studies, which reported that the inhibition is primarily due to competition for adsorption sites, with multivalent anions (CO₃2⁻, SO₄2⁻, PO₄3⁻) outcompeting monovalent nitrate and chloride ions52,53. Furthermore, the surface chemistry of the adsorbent and the specific binding affinities of each anion significantly influence the inhibition sequence52,54. The linear increase in inhibition ratio with concentration (slopes ≈ 0.70% mg⁻1 L for CO₃2⁻/SO₄2⁻, 0.40% mg⁻1 L for PO₄3⁻, and 0.31% mg⁻1 L for Cl⁻) confirms that divalent anions dominate site competition at higher concentrations, leading to up to ~ 35% reduction in nitrate removal efficiency. These findings indicate that CO₃2⁻ and SO₄2⁻ are the most influential inhibitors under environmentally relevant conditions, while Cl⁻ has minimal impact.

Regeneration and reusability of PM biochar

The reusability of the PM Biochar was assessed over five consecutive adsorption–desorption cycles. In the first cycle, 70.67% of nitrate was removed, which decreased to 54% after five cycles following regeneration with 1 M NaOH, corresponding to 76.4% retention of the initial adsorption capacity. The gradual decline in performance may be attributed to surface fouling, pore blockage, or changes in surface chemistry, particularly in long-term or real-world applications55. These findings highlight the potential of the biochar for cost-effective engineering use and are consistent with trends observed in other biochar modifications, including Mg/Al-layered double hydroxide (LDH) composites54,56. Future work should investigate milder regeneration strategies and long-term stability.

Model performance evaluation and discussion

The results of the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) analysis are presented in Fig. 10. The absolute correlation values between all input variables were below 0.7, indicating the absence of significant linear relationships. This suggests that the nitrate adsorption process involves complex nonlinear interactions among variables, emphasizing the need for nonlinear machine learning models to achieve accurate predictions57.

Comparative evaluation through k-fold CV

The predictive performance of RF, SVR, and LR under fivefold CV is summarized in Table 1. The RF model consistently achieved higher mean R2 values and lower standard deviations than other models.

These findings clearly demonstrate that nitrate adsorption is governed by nonlinear and multivariate interactions. The superior and more stable performance of RF reflects its capability to effectively capture these nonlinear dependencies58.

Independent validation via NCV

O obtain an unbiased and rigorous estimate of model performance, NCV was employed, which fully separates hyperparameter optimization (inner loop) from model evaluation (outer loop). The results are presented in Table 2.

The RF model achieved the highest R2 (0.899) with minimal variance, confirming its robustness and generalization ability. The close agreement between CV and NCV results indicates that the observed predictive performance is not an artifact of data partitioning, thus strengthening the reliability of the modeling framework.

Statistical robustness verified by bootstrapping

A 100-iteration bootstrapping analysis was further performed to assess model stability under random resampling. The results are presented in Table 3.

Both RF and SVR achieved high predictive accuracy (R2 > 0.92) with low variance, demonstrating strong model stability and resistance to sampling fluctuations. The ensemble nature of RF, which averages the predictions of multiple decision trees, provides an additional layer of resilience against overfitting. In contrast, LR exhibited substantial variability, indicating its limited capability in modeling the nonlinear adsorption process.

To further visualize the agreement between predicted and experimental adsorption efficiencies, parity plots for the RF, SVR, and LR models are presented in Fig. 11. All three models exhibited a positive correlation between predicted and actual values; however, the RF model displayed the closest alignment with the 1:1 reference line, indicating superior predictive accuracy. The random and uniform distribution of residuals around this line suggests the absence of systematic bias or overfitting. These graphical diagnostics, consistent with the NCV and bootstrapping analyses, confirm the strong generalization capability of the RF model and its ability to accurately represent the nonlinear adsorption mechanisms.

Overall, the integrated evaluation framework—combining fivefold CV, NCV, and bootstrapping—demonstrates the reliability and statistical soundness of the developed predictive models. These findings are in agreement with previous studies emphasizing the superior performance of ensemble and kernel-based algorithms for nonlinear adsorption and contaminant removal processes. The multi-tier validation approach adopted in this study ensures the credibility and reproducibility of the developed framework, even when experimental data are limited.

Sensitivity analysis outcomes

The simultaneous use of many features can reduce model predictive efficiency; therefore, feature selection was performed to remove redundant data and improve performance. Sensitivity analysis using SHAP and PI identified initial contact time and solution pH as the most influential parameters on nitrate adsorption efficiency, while other features had a minor effect (Fig. 12). SHAP, based on game theory, provides a precise measure of each feature’s contribution. This highlights the critical role of contact time and pH, consistent with previous studies, where contact time was identified as crucial for nitrate adsorption by modified biochar2 and pH as a key factor in applying biochar heavy metal adsorption59. The performance of the RF, SVR, and LR models was evaluated under two scenarios: (1) using all available input parameters and (2) using reduced inputs. As illustrated in Fig. 13, The RF model using all input parameters achieved the highest predictive performance with the lowest RMSE value (≈0.078). However, when the dimensionality was reduced by excluding variables such as pH and carbonate concentration, a gradual decline in model accuracy was observed for all methods, with RMSE values increasing.

.

This reduction in accuracy can be attributed to the loss of information when fewer operational parameters are used, thereby limiting the models’ ability to fully capture the nonlinear relationships governing nitrate adsorption. Nevertheless, dimensionality reduction offers practical advantages such as decreased data collection requirements and lower experimental costs, which are particularly important in environmental applications. After dimensionality reduction, the performance of the RF model became comparable to that of the SVR, suggesting that both models retain acceptable predictive capability even with limited input variables. This finding emphasizes the importance of model selection, as nonlinear models such as RF and SVR demonstrate robustness under data constraints. In contrast, the LR model experienced the most significant performance decline, reflecting its limited capacity to describe complex nonlinear adsorption processes. Overall, these results indicate that while including a full set of parameters enhances model accuracy, applying dimensionality reduction can still yield sufficiently reliable predictions, especially when using robust nonlinear models like RF and SVR, while simultaneously minimizing measurement and computational costs.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the sequence of chemical modification plays a decisive role in the nitrate adsorption performance of biochar. Post-pyrolysis modification (PM) achieved the highest adsorption efficiency by maintaining a uniform porous structure, preserving active functional groups, and retaining aluminum content. In contrast, pre-pyrolysis (MP) and re-pyrolysis after modification (PMP) showed lower performance due to structural degradation or alteration of active sites. Operational parameter analysis revealed that contact time and solution pH had the greatest impact on nitrate removal, and adjusting these two parameters can optimize efficiency while reducing operational costs. Machine learning models, particularly RF, enabled accurate prediction of adsorption behavior under variable conditions, and feature selection confirmed that focusing on key parameters is sufficient. The main innovation of this study lies in integrating systematic chemical modification analysis with AI modeling, providing an effective and practical strategy for designing high-performance, sustainable biochars for nitrate removal, with future prospects including multi-contaminant adsorbents and real-water performance evaluation.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Trivedi, Y. et al. Mechanistic assessment of functionalised biochar derived from customised pyrolyzer for nitrate removal. Results Eng. 26, 104672 (2025).

Li, C. et al. Machine learning-driven prediction of nitrate-N adsorption efficiency by Fe-modified biochar: Refined model tuning and identification of crucial features. J. Water Process Eng. 70, 107026 (2025).

Chenchu, S. D. & Deo, M. CuO-modified chitosan beads: An efficient adsorbent for nitrate ion removal from aqueous solution for industrial applications. Results Surfaces Interfaces 100609 (2025).

Núñez-Gómez, D. et al. Sustainable removal of boron and nitrate from agricultural irrigation water using natural sorbents: Optimization and mechanistic insights. J Water Process Eng. 75, 107906 (2025).

Addich, M. et al. Electrocoagulation for nitrate removal from groundwater in Rabat-Kenitra, Morocco: Processing, modeling, optimization and cost estimation. Desalin. Water Treat. 322, 101221 (2025).

Debnath, S. & Das, C. Fabrication of ultrafiltration Membrane Microreactor (MMR) with a novel composition for nitrate removal: Characterization, adsorption, and kinetics studies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 133590 (2025).

Huang, M., Li, J., Gan, Z., Huang, Y. & Meng, F. Efficient biological nitrate removal from hypersaline streams: Denitrification performance and bacterial community succession. Water Research, 124373 (2025).

Berkani, I., Belkacem, M., Trari, M., Lapicque, F. & Bensadok, K. Assessment of electrocoagulation based on nitrate removal, for treating and recycling the Saharan groundwater desalination reverse osmosis concentrate for a sustainable management of Albien resource. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 7, 102951 (2019).

Akula, V. V. et al. Performance evaluation of pilot scale ion exchange membrane bioreactor for nitrate removal from secondary effluent. J. Clean. Prod. 442, 141087 (2024).

Huno, S. K., Rene, E. R., van Hullebusch, E. D. & Annachhatre, A. P. Nitrate removal from groundwater: a review of natural and engineered processes. J. Water Supply: Res. Technol.––AQUA. 67, 885–902 (2018).

Liu, C. et al. Enhanced machine learning prediction of biochar adsorption for dyes: Parameter optimization and experimental validation. Carbon Res. 4, 46 (2025).

Liu, C., Balasubramanian, P., Li, F. & Huang, H. Machine learning prediction of dye adsorption by hydrochar: Parameter optimization and experimental validation. J. Hazard. Mater. 480, 135853 (2024).

Liu, C., Balasubramanian, P., An, J. & Li, F. Machine learning prediction of ammonia nitrogen adsorption on biochar with model evaluation and optimization. Npj Clean Water 8, 13 (2025).

Hollister, C. C., Bisogni, J. J. & Lehmann, J. Ammonium, nitrate, and phosphate sorption to and solute leaching from biochars prepared from corn stover (Zea mays L.) and oak wood (Quercus spp.). J. Environ. Qual. 42, 137–144 (2013).

Ren, J. et al. Granulation and ferric oxides loading enable biochar derived from cotton stalk to remove phosphate from water. Biores. Technol. 178, 119–125 (2015).

Bansal, M. & Pal, B. Enhanced elimination of nitrate and nitrite ions from ground and surface wastewater using chitosan sphere-modified Mg-Al layered double hydroxide composite. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 142, 635–650 (2025).

Long, L., Xue, Y., Hu, X. & Zhu, Y. Study on the influence of surface potential on the nitrate adsorption capacity of metal modified biochar. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 3065–3074 (2019).

Wang, T. et al. Enhanced nitrate removal by physical activation and Mg/Al layered double hydroxide modified biochar derived from wood waste: Adsorption characteristics and mechanisms. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9, 105184 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Development of iron-based biochar for enhancing nitrate adsorption: Effects of specific surface area, electrostatic force, and functional groups. Sci. Total Environ. 856, 159037 (2023).

Tran, T. C. P. et al. Enhancement of phosphate adsorption by chemically modified biochars derived from Mimosa pigra invasive plant. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 4, 100117 (2021).

Choi, M.-Y., Lee, C.-G. & Park, S.-J. Enhanced fluoride adsorption on aluminum-impregnated kenaf biochar: adsorption characteristics and mechanism. Water Air Soil Pollut. 233, 435 (2022).

Yin, Q., Ren, H., Wang, R. & Zhao, Z. Evaluation of nitrate and phosphate adsorption on Al-modified biochar: Influence of Al content. Sci. Total Environ. 631, 895–903 (2018).

Ullah, H. et al. Machine learning-aided biochar design for the adsorptive removal of emerging inorganic pollutants in water. Sep. Purif. Technol. 362, 131421 (2025).

Fu, W. et al. Machine learning-driven prediction of phosphorus removal performance of metal-modified biochar and optimization of preparation processes considering water quality management objectives. Biores. Technol. 403, 130861 (2024).

Yin, Q., Wang, R. & Zhao, Z. Application of Mg–Al-modified biochar for simultaneous removal of ammonium, nitrate, and phosphate from eutrophic water. J. Clean. Prod. 176, 230–240 (2018).

Amusat, S. O., Kebede, T. G., Nxumalo, E. N., Dube, S. & Nindi, M. M. Facile solvent-free modified biochar for removal of mixed steroid hormones and heavy metals: isotherm and kinetic studies. BMC Chem. 17, 158 (2023).

Moosavi, S. et al. A study on machine learning methods’ application for dye adsorption prediction onto agricultural waste activated carbon. Nanomaterials 11, 2734 (2021).

DivbandHafshejani, L., Naseri, A. A., Moradzadeh, M., Daneshvar, E. & Bhatnagar, A. Applications of soft computing techniques for prediction of pollutant removal by environmentally friendly adsorbents (case study: the nitrate adsorption on modified hydrochar). Water Sci. Technol. 86, 1066–1082 (2022).

Zhu, J.-J., Yang, M. & Ren, Z. J. Machine learning in environmental research: common pitfalls and best practices. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 17671–17689 (2023).

Hassan, R. & Kazemi, M. R. Machine learning frameworks to accurately estimate the adsorption of organic materials onto resin and biochar. Sci. Rep. 15, 15157 (2025).

Hafshejani, L. D., Naseri, A. A., Hooshmand, A., Mohammadi, A. S. & Abbasi, F. Prediction of nitrate leaching from soil amended with biosolids by machine learning algorithms. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15, 102783 (2024).

Li, D. et al. Investigation of property of biochar in staged pyrolysis of cellulose. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 172, 105999 (2023).

Huang, H. et al. Characterization of KOH modified biochars from different pyrolysis temperatures and enhanced adsorption of antibiotics. RSC Adv. 7, 14640–14648 (2017).

Xi, L., Ding, K., Zhang, H. & Gu, D. In-situ synthesis of aluminum matrix nanocomposites by selective laser melting of carbon nanotubes modified Al-Mg-Sc-Zr alloys. J. Alloy. Compd. 891, 162047 (2022).

Zheng, Y. et al. Reclaiming phosphorus from secondary treated municipal wastewater with engineered biochar. Chem. Eng. J. 362, 460–468 (2019).

Jung, K.-W., Hwang, M.-J., Jeong, T.-U. & Ahn, K.-H. A novel approach for preparation of modified-biochar derived from marine macroalgae: dual purpose electro-modification for improvement of surface area and metal impregnation. Biores. Technol. 191, 342–345 (2015).

Hashimi, S. Q., Hong, S.-H., Lee, C.-G. & Park, S.-J. Adsorption of arsenic from water using aluminum-modified food waste biochar: Optimization using response surface methodology. Water 14, 2712 (2022).

Li, T., Li, J., Li, Z. & Cheng, X. Mg/Fe Layered Double Hydroxide Modified Biochar for Synergistic Removal of Phosphate and Ammonia Nitrogen from Chicken Farm Wastewater: Adsorption Performance and Mechanisms. Processes 13, 2504 (2025).

Bhattacharjya, D. & Yu, J.-S. Activated carbon made from cow dung as electrode material for electrochemical double layer capacitor. J. Power Sour. 262, 224–231 (2014).

Masjedi, A., Askarizadeh, E. & Baniyaghoob, S. Magnetic nanoparticles surface-modified with tridentate ligands for removal of heavy metal ions from water. Mater. Chem. Phys. 249, 122917 (2020).

Gao, X. et al. Arsenic adsorption on layered double hydroxides biochars and their amended red and calcareous soils. J. Environ. Manage. 271, 111045 (2020).

Zhang, M., Gao, B., Yao, Y. & Inyang, M. Phosphate removal ability of biochar/MgAl-LDH ultra-fine composites prepared by liquid-phase deposition. Chemosphere 92, 1042–1047 (2013).

Ahmad, M. et al. Effects of pyrolysis temperature on soybean stover-and peanut shell-derived biochar properties and TCE adsorption in water. Biores. Technol. 118, 536–544 (2012).

Wang, T. et al. Adsorption characteristics and mechanisms of Pb2+ and Cd2+ by a new agricultural waste–Caragana korshinskii biomass derived biochar. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 13800–13818 (2021).

Inyang, M. I. et al. A review of biochar as a low-cost adsorbent for aqueous heavy metal removal. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 406–433 (2016).

Ansari, S., Bello-Mendoza, R., O’Sullivan, A., Basharat, S. & Barker, D. Nitrate and Phosphate Removal from Water Using a Novel Cellulose-Based Anion Exchange Hydrogel. Environ. Technol. Innov. 104289 (2025).

Kizito, S. et al. Evaluation of slow pyrolyzed wood and rice husks biochar for adsorption of ammonium nitrogen from piggery manure anaerobic digestate slurry. Sci. Total Environ. 505, 102–112 (2015).

Jung, K.-W., Jeong, T.-U., Hwang, M.-J., Kim, K. & Ahn, K.-H. Phosphate adsorption ability of biochar/Mg–Al assembled nanocomposites prepared by aluminum-electrode based electro-assisted modification method with MgCl2 as electrolyte. Biores. Technol. 198, 603–610 (2015).

Hafshejani, L. D. et al. Removal of nitrate from aqueous solution by modified sugarcane bagasse biochar. Ecol. Eng. 95, 101–111 (2016).

Haghighi Mood, S., Pelaez-Samaniego, M. R., Han, Y., Mainali, K. & Garcia-Perez, M. Iron-and Nitrogen-Modified Biochar for Nitrate Adsorption from Aqueous Solution. Sustainability 16, 5733 (2024).

Tan, S.-Y., Sethupathi, S., Leong, K.-H. & Ahmad, T. Acid-modified coffee grounds biochar for nitrate and nitrite removal: an optimization via central composite design. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 21, 3221–3234 (2024).

Amininasab, S. M., Adim, S., Abdolmaleki, S., Soleimani, B. & Hassanzadeh, M. Synthesis and Characterization of Chitosan-Based Hydrogels Grafted Polyimidazolium as Nitrate Ion Adsorbent from Water and Investigating Biological Properties. J. Polym. Environ. 33, 1131–1146 (2025).

Shi, Q., Zhang, S., Xie, M., Christodoulatos, C. & Meng, X. Competitive adsorption of nitrate, phosphate, and sulfate on amine-modified wheat straw: In-situ infrared spectroscopic and density functional theory study. Environ. Res. 215, 114368 (2022).

Alagha, O. et al. Comparative adsorptive removal of phosphate and nitrate from wastewater using biochar-MgAl LDH nanocomposites: coexisting anions effect and mechanistic studies. Nanomaterials 10, 336 (2020).

Vismontienė, R. & Povilaitis, A. Effect of Biochar Amendment in Woodchip Denitrifying Bioreactors for Nitrate and Phosphate Removal in Tile Drainage Flow. Water 13, 2883 (2021).

Mahmoud, M. E., Kamel, N. K., Amira, M. F. & Fekry, N. A. Nitrate removal from wastewater by a novel co-biochar from guava seeds/beetroot peels-functionalized-Mg/Al double-layered hydroxide. Sep. Purif. Technol. 344, 127067 (2024).

Ma, J., Zhang, S., Liu, X. & Wang, J. Machine learning prediction of biochar yield based on biomass characteristics. Biores. Technol. 389, 129820 (2023).

Elzain, H. E. et al. Comparative study of machine learning models for evaluating groundwater vulnerability to nitrate contamination. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 229, 113061 (2022).

Yaseen, Z. M. & Alhalimi, F. L. Heavy metal adsorption efficiency prediction using biochar properties: a comparative analysis for ensemble machine learning models. Sci. Rep. 15, 13434 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank Professor Mohsen Adeli and PhD student Safoura Qazvineh for their valuable scientific guidance and support throughout this study.

Funding

This work was not supported by any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Laleh Divband Hafshejani: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original. Mehri Saeidinia: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – Review & Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hafshejani, L.D., Saeidinia, M. Integrating chemical modification pathways and machine learning for optimization of nitrate removal by rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) biochar. Sci Rep 16, 447 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29743-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29743-3