Abstract

Current detection methods of Demodex mite density in facial erythema are semi-invasive or operator-dependent. We developed and evaluated a deep learning model (DemodexNet) for predicting Demodex mite density and assessed its impact on the diagnostic performance of dermatologists. This study included 1,124 patients with facial erythema who underwent Demodex mite density measurement at two referral hospitals between January 2016 and August 2023. DemodexNet achieved area under the receiver operating characteristic curve values of 0.823–0.865 in internal testing, with lower values observed in the external testing set. AI-assisted evaluation was associated with an increase in diagnostic accuracy among dermatologists from 63.7% to 70.6% (P < .001). Less experienced dermatologists and those with higher trust in AI showed greater performance gains. The model recognized central facial regions and individual lesions characteristic of demodicosis. DemodexNet demonstrates promising performance in predicting Demodex mite density and significantly improves dermatologists’ diagnostic accuracy. As this proof-of-concept study was limited to Korean patients with Fitzpatrick skin types III-IV, validation in diverse populations is required before broader clinical application.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Facial erythema, often referred to as “red face,” is a readily identifiable clinical manifestation in dermatology1. However, its presentation can result from diverse dermatological diseases and other medical conditions2. Rosacea is one of the most common chronic inflammatory conditions that present with frequent flushing and facial erythema. This condition can greatly affect the quality of life of patients and is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, mental, and neurological problems3. Although rosacea is the most emblematic disease associated with “red face,” the differential diagnosis encompasses a broad spectrum of conditions, including contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, acne vulgaris, lupus erythematosus, and dermatomyositis4,5.

Various genetic, environmental, and microbial determinants have been implicated in the etiology of facial erythema. Among these, Demodex mites, which reside within the pilosebaceous units of human facial skin as commensals, are significant contributors6. Demodex mites are commonly found in the skin of healthy adults, with a prevalence rate of 100% and a density of ≤ 5 mites/cm27. However, overproliferation of these mites can lead to pathogenic processes referred to as demodicosis, which result in various symptoms, including facial redness, irritation, itching, and inflammation8,9. The diagnosis of demodicosis is based on the evaluation of the number of Demodex mites present on the skin surface. This can involve a standardized skin surface biopsy or direct microscopic examination of fresh secretions from sebaceous glands (DME)10,11. However, the utility of these methodologies in routine clinical practice is limited owing to their painful, semi-invasive nature and the significant impact of operator proficiency on the results10,12.

This study aimed to develop a deep learning model called DemodexNet, which can predict the density of Demodex mites by analyzing clinical data and photographs of patients with facial erythema. Furthermore, the study assessed the effectiveness of the model in enhancing the ability of dermatologists to identify overproliferation of Demodex mites.

Methods

Study design and participant selection

This diagnostic study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Severance Hospital and Yongin Severance Hospital (approval numbers 4–2023-1008 and 2023-0382-001, respectively). The study adheres to the Checklist for Evaluation of Image-Based Artificial Intelligence Reports in Dermatology34 and the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies reporting guidelines. The requirement for informed consent was waived because retrospective and deidentified data were used.

This study included all patients diagnosed with facial erythema between January 2016 and August 2023 who underwent Demodex mite density measurement at two referral hospitals in South Korea: Severance Hospital and Yongin Severance Hospital. The Demodex mite density was quantified using the DME method, as previously described9,35. A density of > 5 mites/cm2 was classified as high (positive) Demodex infestation10. Patients were excluded if frontal facial photographs were not obtained during their clinic visit on the day of the Demodex examination.

Data preparation and preprocessing

The study included digital images of the face, which underwent an automated face detection and deidentification process to protect personally identifiable information. Using the Mediapipe library, facial landmark coordinates were extracted, and polygonal masks were drawn over the eyes and mouth to protect anonymity. To address class imbalance and prevent overfitting, data augmentation was applied, including geometric transformations and color-based enhancements. Full procedures are detailed in Supplementary Methods S1. Several approaches for handling class imbalance were compared, with data augmentation chosen as the preferred method (see Supplementary Table S5).

Additionally, clinical data were collected for each patient, including age, sex, clinical symptoms (itching, burning or stinging, edema, dryness, and flushing), serum allergy marker levels (eosinophil cationic protein, total immunoglobulin E (IgE), and eosinophil counts), patch test results, and the presence of extra-facial skin lesions32. Missing values in serum allergy markers (19.0% of the dataset) were imputed using the MissForest algorithm with optimized hyperparameters as detailed in Supplementary Methods S4.

Model development

To develop an AI model that learns the distribution of facial demodicosis and individual localized lesions situated around complex anatomical landmarks while integrating clinical information, we implemented a two-fold strategy in our model development process. First, a stacking ensemble (SE) model was developed, layering networks focusing on the comprehensive facial image and localized patches indicative of Demodex infestation (Fig. 1a)20,21. Second, we applied the Globally-aware Multiple Instance Classifier (GMIC), a weakly supervised model designed for end-to-end training to independently identify patches associated with Demodex infestation from the full image (Fig. 1b)23,36. While the architectures of these models are independent and differ, both include global and local modules for capturing the nuanced features of Demodex infestation. Moreover, each model incorporates 12 clinical variables related to the image data in a distinct module, leading to a combined prediction model that merges insights from both image and clinical data (Supplementary Figure S1). The data collected from Severance Hospital constituted the primary dataset, with an allocation of 80% for model training, 10% for validation, and 10% for internal testing. The entire dataset from Yongin Severance Hospital (100%) was designated as the external testing set (Table 1). Additionally, we employed 10-fold stratified cross-validation to maintain model performance robustness.

SE architecture

The SE framework comprises global, local, and clinical modules, which take as input a whole facial image \(\:\text{G}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{H\times\:W\times\:3}\), seven localized patches \(\:{\text{P}}_{k}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{H\times\:W\times\:3}\) with \(\:k=1,\dots\:,7\), and clinical data\(\:\:\text{C}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{12}\). We extracted patches, including the forehead, nose, cheeks, and chin, based on facial landmark coordinates obtained during the deidentification process. Each module employed an independent feature extractor, referred to as a base learner: \(\:{f}_{g}\) and \(\:{f}_{l}\) (DenseNet121 for image modules) and \(\:{f}_{c}\) (XGBoost for clinical data). The global module processes the whole face image G using a DenseNet121 and outputs a probability as

Similarly, the local module processes each patch \(\:{P}_{k}\) to output \(\:{y}_{l,k}={f}_{l}\left({P}_{k}\right)\), and the outputs from the local module are then summed to obtain the integrated local score:

The clinical module produces \(\:{y}_{c}={f}_{c}\left(C\right)\). These outputs are concatenated into a feature vector \(\:\text{z}=[{y}_{g},\:{y}_{l},\:{y}_{c}]\), which is subsequently passed to a meta learner \(\:{f}_{m}\) to obtain the final prediction:

Each base learner is trained using the binary cross‑entropy loss:

Additional implementation details are provided in Supplementary Methods S2.

GMIC architecture

The GMIC also consists of global, local, and clinical modules. It takes as input the original high-resolution image \(\:\text{x}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{H\times\:W\times\:3}\) along with clinical data \(\:\text{C}\). A global network \(\:{f}_{g}\) first extracts a feature map as follows:

Then, a 1\(\:\times\:\)1 convolution followed by a sigmoid activation produces a saliency map \(\:\text{A}\), which highlights regions potentially relevant to Demodex infestation. Based on the saliency map, \(\:\text{K}\) regions of interest (ROIs), representing the most informative patches, are selected from the input \(\:\text{x}\) according to the following procedure:

We employed a greedy algorithm to retrieve \(\:\text{K}\) patches, denoted as \(\:{\stackrel{\sim}{x}}_{k}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{{h}_{c,}{w}_{c}}\), where we set \(\:{w}_{c}={h}_{c}=256\). We heuristically set K\(\:=\)6 (see Supplementary Table S6), and each patch was then processed by a local network \(\:{f}_{l}\) to obtain feature vectors:

Attention weights \(\:{\alpha\:}_{k}\) are computed using a gated mechanism, as the selected ROI patches do not contribute equally to the final prediction. This mechanism enables the model to assign higher weights to more informative patches, thereby enabling effective aggregation of local features:

with learnable parameters \(\:\mathbf{w}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{L}\), \(\:\mathbf{V}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{L\times\:M}\), and \(\:\mathbf{U}\in\:{\mathbb{R}}^{L\times\:M}\) with \(\:\text{L}=512\) and \(\:\text{M}=128\). The weight sum via attention-weighted aggregation,

is used to represent the locally aggregated feature.

Clinical data are separately encoded by a multi‑layer perceptron to produce the feature vector \(\:{h}_{c}={f}_{c}\left(C\right)\). To integrate the global and local feature, we applied global max pooling on \(\:{h}_{g}\) and concatenated it with \(\:\text{z}\) and \(\:{h}_{c}\). The fused representation is subsequently passed through a fully connected layer with a softmax activation to yield the final prediction:

where \(\:{\varvec{w}}_{f}\) values are learnable parameters. The GMIC is trained with the following loss function:

where \(\:\beta\:\) is a weighting coefficient. To encourage the saliency map to focus only on highly informative regions, we applied the L1 regularization on \(\:A\):

Further implementation details are provided in Supplementary Methods S3.

Human evaluators and decision study

Twenty-one participants, comprising 10 dermatology residents and 11 board-certified dermatologists, were recruited to evaluate the ability of human evaluators to classify Demodex infestation cases using facial images and clinical data. The study also aimed to assess potential performance improvement with the assistance of DemodexNet. An anonymous online questionnaire was administered in two parts over a two-week interval using Google Survey (Supplementary Figure S2).

We used all 100 cases from the internal testing dataset in Part I. Participants were presented with original-resolution photographs and associated clinical data (age, sex, clinical symptoms, and the presence of extra-facial skin lesions). They were asked to classify each case as positive or negative for Demodex infestation. In Part II, participants were given DemodexNet’s confidence scores (ranging from 0 to 1) for each case, with scores ≥ 0.5 indicating a model prediction of Demodex positivity. Participant performance was assessed by comparing their predictions with the gold standard label. Case sequences were shuffled between parts to ensure unbiased responses. Reference diagnoses and participant scores were not disclosed until the conclusion of the study.

Evaluation of algorithm performance and statistics

Model performance was evaluated using top-1 accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and the F1 score. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted using sensitivity and specificity for each threshold, and areas under the curve (AUCs) were calculated. Additionally, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained via nonparametric bootstrap of predictions with replacement (N = 1000), using the same sample size as the internal test set and external set for each resample37.

For a visual explanation of Demodex mite distribution predictions, we implemented gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM)38 on each base learner for the SE model. For the GMIC model, we visualized saliency maps based on the algorithm’s inherent attention scores. To identify significant variables in predicting algorithm outcomes for the clinical-data-based model, we employed SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to visualize feature importance rankings39. Additionally, we conducted multivariate logistic regression analyses to identify predictive factors associated with high Demodex mite density.

We determined the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of human participants for each part, comparing their performances before and after algorithm assistance using the McNemar test. This test was specifically chosen for paired nominal data, where each evaluator assessed the same 100 images twice. We constructed 2 × 2 contingency tables for each evaluator comparing their diagnostic decisions (correct/incorrect) between Part I (image only) and Part II (image with AI assistance) to evaluate whether AI assistance significantly improved diagnostic performance.

Fleiss’ kappa (κ) values were calculated to evaluate agreement among participants’ responses, and we generated a heatmap using hierarchical agglomerative clustering to visualize interparticipant agreement rates24,40. Statistical analyses were performed using Python version 3.9.7 and R version 4.1.3. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed P-value < 0.05.

Results

Study dataset

The study included 1,024 and 100 patients in the main and external datasets, respectively. The main dataset was collected at Severance Hospital from January 2016 to December 2022, while the external dataset was obtained at Yongin Severance Hospital from March 2020 to August 2023. Both sites used standardized indoor clinical lighting with a consistent blue background and white overhead illumination, along with similar digital cameras. The datasets showed comparable gender distributions (68.1% and 70.0% female, respectively) but differed in median age at diagnosis (32.5 vs. 37.5 years) and notably in Demodex positivity rates (24.9% vs. 45.0%). Detailed participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1, and baseline comparisons of clinical features by Demodex mite density are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

The study included 1,024 and 100 patients in the main and external datasets, respectively. Both datasets predominantly comprised female participants (68.1% and 70.0%, respectively), with median ages at diagnosis of 32.5 and 37.5 years, respectively.

Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1, and baseline comparisons of clinical features by Demodex mite density are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Model performance

Table 2 summarizes the performance metrics of the DemodexNet models—sensitivity, specificity, F1 score, ROC–AUC, and accuracy—reported from the fold with the smallest absolute validation–test ROC–AUC gap. For the SE model, the image-based model on the internal testing set achieved an ROC–AUC of 0.825 (95% CI: 0.734–0.903), with relatively high specificity (0.980 [95% CI: 0.937–1.000]) and low sensitivity (0.260 [95% CI: 0.143–0.380]). The clinical data-based model achieved an ROC–AUC of 0.842 (95% CI: 0.751–0.915), while the combination of these two models yielded an ROC–AUC of 0.823 (95% CI: 0.728–0.896). For the GMIC model, the image-based model achieved an ROC-AUC of 0.833 (95% CI: 0.753–0.908) on the internal testing set, with balanced specificity (0.760 [95% CI: 0.633–0.872]) and sensitivity (0.640 [95% CI: 0.500–0.767]). The clinical data-based model achieved an ROC–AUC of 0.790 (95% CI: 0.680–0.873), while the combined model yielded an improved ROC–AUC of 0.865 (95% CI: 0.785–0.934). Both models exhibited similar trends in the external test dataset, although with lower ROC–AUC and accuracy values than the internal test set results (Supplementary Figure S3).

Augmented decision-making with artificial intelligence

We invited 21 dermatologists to participate in a two-step reader study to validate the decision support provided by DemodexNet. Without AI assistance, participants demonstrated an accuracy of 0.637 (95% CI: 0.615–0.656), representing an absolute improvement of 6.9% (95% CI: 4.1–9.7%, P <.001). The effect was most pronounced for sensitivity, with an absolute increase of 13.6% (95% CI: −16.6–16.6%, P <.001), while specificity remained relatively stable with a 0.2% change (95% CI: −2.6–2.6%, P =.95).

When analyzing human raters divided into three subgroups based on clinical experience, the magnitude of improvement varied notably. The low-experience group (> 2 years) showed the most significant benefit, with an 11.6% absolute accuracy improvement, while the high-experience group (> 8 years) demonstrated a 5.8% improvement; both achieved statistical significance (P <.001 and P =.01, respectively). The low-experience group initially underperformed compared with the AI model in Part I. However, in Part II, this group showed more pronounced improvements in accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity than more experienced groups (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table S2). Comparing responses between Parts I and II to assess changes in rater response based on AI predictions, we observed that less experienced raters were more likely to modify their responses to correct answers when assisted by AI. Notably, this increased correction rate was not accompanied by a higher tendency to follow incorrect AI predictions (Fig. 2b).

Performance of DemodexNet and its impact on human evaluators. (a) Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for the DemodexNet models and human evaluators before and after AI assistance. (b) Benefit of AI assistance stratified by evaluator experience level. (c) Benefit of AI assistance based on evaluators’ trust in AI. GMIC, Globally-aware Multiple Instance Classifier; SE, stacking ensemble; TPR, true positive rate; FPR, false positive rate; AI, artificial intelligence. “Benefit” is defined as the change in response from Part 1 to Part 2 that aligns with the response generated by AI, scored as positive when the changed response matches the gold label and negative when it does not. *P <.05, **P <.001 for Mann–Whitney U test.

Following Part II, we conducted a 5-point questionnaire-based assessment of DemodexNet among human evaluators13. On the basis of the survey results, we divided participants into two subgroups: those with a positive impression of DemodexNet (Trust group) and those without (Untrust group). We then performed a subgroup analysis (Supplementary Figure S4). Results showed that the Trust group demonstrated significantly higher positive benefits when modifying their responses according to AI predictions. Notably, the two groups had no significant difference in responses to incorrect AI predictions (Fig. 2c).

Effect of AI predictions on human responses

Figure 3a and b illustrate the interrater agreement rates among participant responses, AI model predictions, and gold standard labels. In Part I, significant disagreements were observed among participants (Fig. 3a, Fleiss’ κ = 0.388 [95% CI, 0.374–0.401]). In contrast, Part II showed a significant improvement in interrater agreement (Fig. 3b, Fleiss’ κ = 0.453 [95% CI, 0.439–0.466]). Interestingly, while the interrater agreement rate between the low-experience and expert groups was notably lower than that in other group pairs in Part I, this disparity showed substantial improvement after AI assistance in Part II.

Impact of DemodexNet assistance on interrater agreement and diagnostic patterns. (a) Interrater agreement heatmap for Part I (image only). (b) Interrater agreement heatmap for Part II (image + DemodexNet assist). (c) Distribution of diagnoses for low Demodex cases. (d) Distribution of diagnoses for high Demodex cases. PPR, papulopustular rosacea; ETR, erythematotelangiectatic rosacea; ACD, allergic contact dermatitis; AD, atopic dermatitis; SD/POD, seborrheic dermatitis/perioral dermatitis.

We sought to examine the selection tendencies of human evaluators and AI in successfully predicting high Demodex mite density cases, based on their actual clinical diagnoses. Two dermatologists reviewed and labeled the final clinical diagnoses of 100 cases from the internal test set. We then analyzed the distribution of clinical diagnoses among correct answers given by humans, humans with AI assistance, and the AI model alone.

Overall, the AI model showed higher accuracy for high Demodex cases (44.0% vs. 23.8%), whereas dermatologists performed slightly better in low Demodex cases (34.7% vs.31.5%). Human evaluators tended to select papulopustular rosacea more frequently than the AI model in high Demodex cases (58.4% vs. 41.1%), whereas the AI model showed a higher tendency to choose erythematotelangiectatic rosacea than humans (27.5% vs. 16.0%).

In low Demodex cases, humans favored erythematotelangiectatic rosacea selections compared with the AI model (10.1% vs. 2.9%), whereas the AI model showed a higher tendency to select atopic dermatitis or acne/folliculitis. Notably, human evaluators assisted by AI demonstrated intermediate values in both overall accuracy and relative distribution of clinical diagnoses, falling between unassisted humans and the AI model alone (Fig. 3c and d and Supplementary Table S3).

Explainable AI models

Feature importance rankings based on absolute SHAP values revealed that the presence of extra-facial skin lesions had the most decisive influence on the model’s output. This was followed by age, eosinophil cationic protein, total IgE, eosinophil count, flushing, and positive patch test results (Supplementary Figure S5). Subsequent multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed using two models: a stepwise variable selection model (Model 1) and a model using the Top-7 features from SHAP analysis (Model 2). Both models consistently showed that age (odds ratio [OR]: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.19–1.46 for Model 1; OR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.12–1.38 for Model 2) and positive patch test results (OR: 1.60, 95% CI: 1.13–2.25 for Model 1; OR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.01–2.04 for Model 2) were positively correlated with Demodex mite density. Conversely, extra-facial skin involvement was negatively correlated with Demodex mite density in both models (OR: 0.16, 95% CI: 0.11–0.24 for Model 1; OR: 0.20, 95% CI: 0.13–0.31 for Model 2, Table 3).

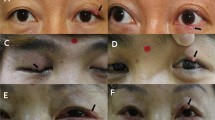

Analysis of saliency maps from the GMIC model and Grad-CAM from the SE model revealed that the AI models primarily recognized the central facial region, the leading proliferation site for Demodex mites. Furthermore, the models demonstrated the ability to detect individual skin lesions characteristic of demodicosis, such as fine-scaled papules or tiny pustules (Fig. 4; see also Supplementary Figure S6 for additional examples).

Visualization of DemodexNet’s attention mechanisms. (a) GMIC model saliency maps and attention scores for three representative cases. For each case: input image (left), patch map showing regions of interest (center), and saliency map highlighting areas of model focus (right). Attention scores (α) indicate the importance of each patch. (b) Class activation mapping of the SE model, showing heat maps of regions contributing to the model decisions. (1) to (4) represent different facial local patches with their corresponding close-up views and activation maps. GMIC, Globally-aware Multiple Instance Classifier; SE, stacking ensemble.

Discussion

Various AI models have been developed for inflammatory dermatoses causing facial erythema. Most of these are based on single convolutional neural network models for classification or severity grading of conditions such as acne or rosacea14,15,16,17,18. Particularly in individuals with skin of color, diagnosing facial erythema diseases, such as rosacea, based solely on photographs or clinical findings can be challenging19. Although Demodex mite density testing aids in differential diagnosis, its limited availability prompted us to propose DemodexNet as a complementary diagnostic tool.

In this study, we developed DemodexNet, a deep learning model that predicts Demodex mite density in patients with facial erythema using clinical data and photographs. The model demonstrated considerable performance, with ROC-AUC values of 0.823–0.865 in internal testing. When used as a decision-support tool, DemodexNet was associated with an improvement in diagnostic accuracy from 63.7% to 70.6% (P <.001) among participating dermatologists. Notably, less experienced dermatologists and those who trusted DemodexNet more benefited the most from AI assistance without increasing errors. The model primarily recognized facial areas and individual lesions characteristic of demodicosis. Additionally, we identified unique clinical features associated with increased Demodex mite density.

Accurate prediction of Demodex mite density necessitates a model that incorporates both the distribution of erythema throughout the face and the detailed aspects of individual lesions, while also considering clinical features associated with facial erythema5,8. Given the complex anatomical landmarks of the face, deriving Demodex mite density directly from a whole face image using a single model is challenging20. Therefore, we constructed a deep ensemble model based on SE and GMIC, capable of capturing global and local features from multiple facial subregions while incorporating clinical factors. The SE model uses a parallel arrangement of base models for the whole face and local patches, training global and local features in a complementary manner20,21. The GMIC model employs flexible localized patches that vary for each face, thus providing an individualized, patient-tailored approach22,23.

Several studies have investigated the effect of AI assistance on the diagnostic accuracy of clinicians for various skin conditions, including skin cancers, pressure ulcers, and lupus erythematosus24,25,26,27,28. Although the present study focused on a different disease with a distinct dataset, the effect of AI assistance on decision-making among survey participants shared similar aspects with previous research. Specifically, raters with less experience or those with higher trust in AI demonstrated greater performance gains from AI-based support25,26,27. Moreover, concordance in clinical decisions between diverse groups of experts increased with augmented decision-making24,27. Additionally, considering the differences in clinical diagnosis labels between AI and humans, they appear to use distinct diagnostic clues to determine high or low Demodex cases. Notably, these differences were mitigated in humans receiving decision support, proving that AI and clinician expertise can complement each other29.

Our findings suggest that visualization techniques derived from two different model architectures consistently highlight the distribution of Demodex mites across the whole face and individual lesions. This attention was particularly pronounced in individuals with typical papulopustular rosacea, known for high Demodex mite density (Fig. 3)30,31. Interestingly, compared with humans, the AI model more often classified cases as high Demodex mites in conditions with atypical facial erythema distribution, such as erythematotelangiectatic rosacea or contact dermatitis (Fig. 3d)12,32. This suggests that the decision-making of AI may rely more heavily on recognizing microscopic textures than human assessments33.

The performance gap between internal and external validation warrants careful consideration. Our analysis revealed two primary factors contributing to this difference. Clinically, the external dataset exhibited substantially different population characteristics, including nearly double the rate of high Demodex density (45.0% vs. 24.9%) and varying extrafacial involvement patterns, suggesting distinct clinical phenotypes between institutions. Additionally, inter-examiner variability in the operator-dependent DME method likely introduced differences in ground-truth labeling, despite standardized protocols. From a technical perspective, both our multi-modal architectures (SE and GMIC) may be inherently sensitive to distributional shifts. The SE model’s reliance on fixed patches may capture non-discriminative features, whereas GMIC’s joint optimization of global, local, and clinical modules with shared gradients could lead to feature misalignment under distribution shift. Although multi-modal fusion effectively captures comprehensive information, it also increases vulnerability to dataset heterogeneity. These findings highlight that the observed performance degradation reflects both real-world clinical variation and architectural limitations, emphasizing the need for domain adaptation strategies in future iterations of the model.

This study has some limitations. First, this work represents a proof-of-concept study with limited generalizability. The data were sourced from two referral hospitals in South Korea, including only a single ethnic group with Fitzpatrick skin types III and IV. This homogeneous population restricts the model’s applicability to diverse ethnic backgrounds and other skin phototypes. Future multi-center, multi-ethnic validation studies are essential before clinical deployment in broader populations. Second, our dataset exhibited significant class imbalance, with only 24.9% positive cases in the training set, which may affect model sensitivity and generalization. Third, the external validation cohort was relatively small (n = 100), which limited our ability to comprehensively assess model generalizability. Fourth, the DME method used for Demodexmite detection is operator dependent10, which may lead to variations in sensitivity among different examiners. While each institution employed a single experienced examiner (> 5 years) using standardized protocols to minimize within-site variability, we lack inter-rater reliability data between institutions, which limits our ability to assess the consistency of our ground truth labels across datasets.

Lastly, the performance of human participants may have been underestimated in our experimental setting, which differed from real-world clinical practice. Participants were provided only frontal facial photographs and limited clinical information, without access to diagnostic tools, such as dermoscopy.

In conclusion, this diagnostic study used clinical data and photographs to develop and evaluate DemodexNet, a deep learning model for predicting Demodex mite density in patients with facial erythema. The model showed promising results in predicting Demodex mite density and significantly improved the diagnostic accuracy of dermatologists when used as a decision-support tool. The ability of the model to recognize both global facial features and individual lesions characteristic of demodicosis highlights its potential as a valuable aid in clinical practice. Although future studies are needed to validate these results across diverse populations and clinical settings, DemodexNet could potentially aid in clinical evaluation and the management of Demodex-related facial erythema, particularly in resource-limited settings or for less experienced clinicians.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy restrictions. The data contain potentially identifiable facial photographs of patients with dermatological conditions, and public sharing of these images is prohibited by the institutional ethics committees and data protection policies of Yonsei University Health System. Even with deidentification procedures applied, facial features remain inherently identifiable, and patients did not provide consent for public data sharing. However, deidentified clinical data and aggregated statistical results are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The code supporting the findings of this study is openly available at https://github.com/L-YUNNA/demodex_GMIC_pytorch.

References

Dessinioti, C. & Antoniou, C. The red face: not always rosacea. Clin. Dermatol. 35, 201–206 (2017).

Izikson, L., English, I. I. I., Zirwas, M. J. & J. C. & The Flushing patient: differential diagnosis, workup, and treatment. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 55, 193–208 (2006).

Haber, R. & El Gemayel, M. Comorbidities in rosacea: a systematic review and update. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 78, 786–792 (2018). e788.

Olazagasti, J., Lynch, P. & Fazel, N. The great mimickers of rosacea. Cutis 94, 39–45 (2014).

Gallo, R. L. et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National rosacea society expert committee. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 78, 148–155 (2018).

NUTTING, W. B. Hair follicle mites (Acari: Demodicidae) of man. Int. J. Dermatol. 15, 79–98 (1976).

Forton, F. & Seys, B. Density of demodex folliculorum in rosacea: a case-control study using standardized skin‐surface biopsy. Br. J. Dermatol. 128, 650–659 (1993).

Forton, F. Papulopustular rosacea, skin immunity and demodex: pityriasis folliculorum as a missing link. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 26, 19–28 (2012).

Lee, S. G. et al. Cutaneous neurogenic inflammation mediated by TRPV1–NGF–TRKA pathway activation in rosacea is exacerbated by the presence of demodex mites. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 37, 2589–2600 (2023).

Aşkın, Ü. & Seçkin, D. Comparison of the two techniques for measurement of the density of demodex folliculorum: standardized skin surface biopsy and direct microscopic examination. Br. J. Dermatol. 162, 1124–1126 (2010).

Forton, F. et al. Demodicosis and rosacea: epidemiology and significance in daily dermatologic practice. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 52, 74–87 (2005).

Forton, F. & De Maertelaer, V. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea May be associated with a subclinical stage of demodicosis: a case–control study. Br. J. Dermatol. 181, 818–825 (2019).

Zhou, J. et al. Pre-trained multimodal large Language model enhances dermatological diagnosis using SkinGPT-4. Nat. Commun. 15, 5649 (2024).

Zhao, T., Zhang, H. & Spoelstra, J. A computer vision application for assessing facial acne severity from selfie images. arXiv preprint arXiv:.07901 (2019). (2019). (1907).

Binol, H. et al. Ros-NET: A deep convolutional neural network for automatic identification of rosacea lesions. Skin. Res. Technol. 26, 413–421 (2020).

Lim, Z. V. et al. Automated grading of acne vulgaris by deep learning with convolutional neural networks. Skin. Res. Technol. 26, 187–192 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Construction and evaluation of a deep learning model for assessing acne vulgaris using clinical images. Dermatology Therapy. 11, 1239–1248 (2021).

Zhao, Z. et al. A novel convolutional neural network for the diagnosis and classification of rosacea: usability study. JMIR Med. Inf. 9, e23415 (2021).

Alexis, A. F. et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 80, 1722–1729 (2019). e1727.

Fan, Y., Lam, J. C. & Li, V. O. (2018) In Artificial neural networks and machine learning–ICANN 2018: 27th International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Rhodes, Greece, October 4–7, Proceedings, Part I 27. 84–94 (Springer).

Almasi, R., Vafaei, A., Kazeminasab, E. & Rabbani, H. Automatic detection of microaneurysms in optical coherence tomography images of retina using convolutional neural networks and transfer learning. Sci. Rep. 12, 13975 (2022).

Shamout, F. E. et al. An artificial intelligence system for predicting the deterioration of COVID-19 patients in the emergency department. NPJ Digit. Med. 4, 80 (2021).

Shen, Y. et al. An interpretable classifier for high-resolution breast cancer screening images utilizing weakly supervised localization. Med. Image Anal. 68, 101908 (2021).

Lee, S. et al. Augmented decision-making for acral lentiginous melanoma detection using deep convolutional neural networks. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 34, 1842–1850 (2020).

Tschandl, P. et al. Human–computer collaboration for skin cancer recognition. Nat. Med. 26, 1229–1234 (2020).

Han, S. S. et al. Evaluation of artificial intelligence–assisted diagnosis of skin neoplasms: a single-center, paralleled, unmasked, randomized controlled trial. J. Invest. Dermatol. 142, 2353–2362 (2022). e2352.

Kim, J. et al. Augmented decision-making in wound care: evaluating the clinical utility of a deep-learning model for pressure injury staging. Int. J. Med. Inf. 180, 105266 (2023).

Li, Q. et al. Human-multimodal deep learning collaboration in ‘precise’diagnosis of lupus erythematosus subtypes and similar skin diseases. J Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 38(12), 2268–2279 (2024).

Farzaneh, N., Ansari, S., Lee, E., Ward, K. R. & Sjoding, M. W. Collaborative strategies for deploying artificial intelligence to complement physician diagnoses of acute respiratory distress syndrome. NPJ Digit. Med. 6, 62 (2023).

Chang, Y. S. & Huang, Y. C. Role of demodex mite infestation in rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 77, 441–447 (2017). e446.

Sattler, E. C., Hoffmann, V. S., Ruzicka, T., Braunmühl, T. & Berking, C. Reflectance confocal microscopy for monitoring the density of demodex mites in patients with rosacea before and after treatment. Br. J. Dermatol. 173, 69–75 (2015).

Kim, J. et al. Contact hypersensitivity and demodex mite infestation in patients with rosacea: a retrospective cohort analysis. Eur. J. Dermatol. 32, 716–723 (2022).

Geirhos, R. et al. ImageNet-trained CNNs are biased towards texture; increasing shape bias improves accuracy and robustness. arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.12231 (2018).

Daneshjou, R. et al. Checklist for evaluation of image-based artificial intelligence reports in dermatology: CLEAR derm consensus guidelines from the international skin imaging collaboration artificial intelligence working group. JAMA Dermatology. 158, 90–96 (2022).

Huang, H., Hsu, C. & Lee, J. Thumbnail-squeezing method: an effective method for assessing Demodex density in rosacea. (2021).

Ilse, M., Tomczak, J. & Welling, M. in International conference on machine learning. 2127–2136 (PMLR).

Sanchez-Lengeling, B. et al. Machine learning for scent: Learning generalizable perceptual representations of small molecules. arXiv preprint arXiv:.10685 (2019). (2019). (1910).

Selvaraju, R. R. et al. in Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision. 618–626.

Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S. I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv Neural Inf. Process. Syst 30 (2017).

Fleiss, J. L. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol. Bull. 76, 378 (1971).

Acknowledgements

We thank the board-certified dermatologists and dermatology residents who participated in the user tests. Additionally, we are thankful for the assistance provided by the Digital Health Center, Yonsei University Health System, in data preprocessing and technical support. Also, we are grateful to Prof. Youngdeok Hwang (Paul H. Chook Department of Information Systems and Statistics, Baruch College, The City University of New York, NY, USA) for his expert statistical consultation.

Funding

This work was supported by faculty research grants from Yonsei University College of Medicine (6-2023-0098 and 6-2024-0056); research grants from the Korean Dermatological Association and Amore Pacific Skin Science 2023; a grant from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number HI14C1324); and grants from the National Institutes of Health, including grant number RS-2023-00265913, a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (grant number RS-2023-00234581, RS-2024-00344273 and RS-2025-16070039), and a new faculty research seed money grant from Yonsei University College of Medicine (grant number 2024-32-0056). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

COP and Jihee K had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the data’s integrity and the data’s accuracy. Jemin K and YNL contributed equally to this work as co-first authors.Concept and design: Jemin K, Jihee K, YNL, and COP. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: JB, JHL, YSC, and HK.Drafting of the manuscript: Jemin K, YNL, JB, and Jihee K.Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: IO, JIN, and COP.Statistical analysis: Jemin K, YNL, and JB.Obtained funding: Jemin K, Jihee K, and COP.Administrative, technical, or material support: CL and IO.Supervision: Jihee K, COP, and IN.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Oh is currently employed by LG Chem Ltd. However, the company did not have any role in the study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of this manuscript. All other authors declare no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Severance Hospital and Yongin Severance Hospital (approval numbers 4-2023-1008 and 2023-0382-001, respectively), with a waiver of informed consent for the retrospective analysis of clinical data. For patients whose clinical images are presented in this manuscript, separate written informed consent was obtained for publication of their case details.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J., Lee, Y.N., Boo, J. et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted prediction of Demodex mite density in facial erythema. Sci Rep 16, 456 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29791-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29791-9