Abstract

Postoperative delirium (POD) significantly increases mortality and medical burden, however, evidence regarding the best opioid options after cardiac surgery remains limited.Using the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) database, we identified 8246 adult patients receiving > 70% of postoperative 24-h morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) during the ICU length of stay as fentanyl, morphine, or hydromorphone. After 1:1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) (n = 701 per group), we compared POD incidence, mortality, length of stay, vasopressor- and ventilator-free days within 28 days.The matched cohort of 2103 patients showed balanced baseline characteristics (all SMD < 0.1). POD incidence was significantly lower in the morphine (10.6%) and hydromorphone (9.7%) groups than in the fentanyl group (22.1%). The hydromorphone group was associated with significantly lower rates of ICU (OR 0.07, 95% CI 0.01–0.53) and hospital mortality (OR 0.25,95% CI 0.08–0.74), as well as shorter ICU and hospital length of stay, and more vasopressor- and ventilator-free days within 28 days. Hydromorphone was associated with a significantly lower incidence of POD, lower mortality, shorter length of stay, and more vasopressor- and ventilator-free days within 28 days. Whereas morphine was also associated with a reduced risk of delirium and shorter length of stay, it was not significantly associated with a reduction in mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postoperative delirium (POD) is a common complication following cardiac surgery, with an incidence rate as high as 11.5–54.9%, particularly prevalent among elderly and high-risk populations1,2,3,4. POD can prolong mechanical ventilation and increase ICU and total hospitalization time5,6,7. It may also negatively affect long-term cognitive function and quality of life. Studies indicate that POD is linked to long-term cognitive impairment, emotional disorders, and reduced postoperative survival rates6,8,9.

Opioids are crucial for postoperative analgesia, but the link between opioids and POD is not well understood, partly due to their dichotomous (pro- and anti-inflammatory) effects on the central nervous system10. Some studies have associated certain opioids, such as pethidine and tramadol, with a higher risk of POD, whereas morphine, fentanyl and hydromorphone appear to pose a lower risk11,12. A Japanese study found no statistically significant difference in POD risk among morphine, fentanyl, and oxycodone13. However, another study involving mechanically ventilated patients reported a slightly higher incidence of POD with fentanyl than with morphine14. According to a meta-analysis by Michael Reisinger et al., the evidence linking opioids to POD is generally of very low quality and insufficient for definitive conclusions to be drawn15. Hydromorphone has proven effective in alleviating agitation and improving analgesia in pediatric patients16, but its impact on POD in adult cardiac surgery patients requires further research.

To address this gap, we conducted a propensity score-matched cohort study using the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) database. The primary objective was to compare the incidence of POD among adult cardiac surgery patients receiving predominantly fentanyl, morphine, or hydromorphone within the first 24 h postoperatively. Secondary outcomes included ICU and hospital mortality, length of stay, and vasopressor- and ventilator-free days within 28 days.

This study tested two primary hypotheses: (1) postoperative analgesia based on hydromorphone is associated with a lower risk of POD than fentanyl-based analgesia; and (2) postoperative analgesia based on morphine is associated with a lower risk of POD than fentanyl-based analgesia.We further hypothesized that hydromorphone, compared with both morphine and fentanyl, is associated with superior ICU mortality, hospital mortality, ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, and a greater vasopressor- and ventilator-free days within 28 days.The findings from this study are poised to inform evidence-based analgesic protocols within the framework of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) for cardiac patients, ultimately aiming to improve recovery outcomes and reduce the burden of POD.

Results

Baseline characteristics

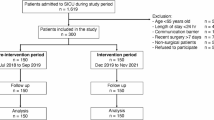

The present study initially enrolled a total of 8246 patients, categorized into three cohorts based on postoperative opioid administration: 3612 patients in the fentanyl group, 3077 patients in the morphine group, and 1557 patients in the hydromorphone group. Before PSM, notable baseline discrepancies were identified across these groups (Table S2).The fentanyl cohort demonstrated significantly higher mean age (68.5 ± 10.6 years compared to 63.2 ± 11.6 years), greater severity of illness (SOFA score: 6.00 ± 2.54 versus 5.23 ± 2.10), and a higher mechanical ventilation rate (74.9% versus 60.8%). These findings pointed to the presence of selection bias.

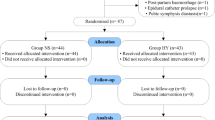

To mitigate these discrepancies and minimize the risk of confounding biases, a 1:1:1 PSM was applied, resulting in a balanced cohort of 2103 patients (with 701 in each group). Upon analysis, the matched dataset revealed that SMDs across all variables—such as demographic factors (age, gender), vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure), laboratory indices (white blood cell count, creatinine ), comorbidity incidence, and severity scores (SOFA, APS III, CCI)—were uniformly below 0.1 (Table S2, Fig. S1). These results confirm the successful elimination of baseline imbalances between the groups.

After PSM, significant differences in clinical outcomes were identified across the fentanyl, morphine, and hydromorphone groups, as detailed in Table 1. With respect to primary endpoints, the morphine group exhibited a significantly lower POD incidence (10.6%) compared to the fentanyl group (22.1%), while the hydromorphone group also showed a comparable reduction (9.7%, p < 0.001). Secondary outcome analysis revealed that both hydromorphone and morphine were associated with enhanced clinical outcomes compared to fentanyl. Specifically, ICU mortality rates were 2.0% in the fentanyl group, 1.3% in the morphine group, and 0.1% in the hydromorphone group (p = 0.004). Similarly, overall hospitalization mortality rates were 2.3% for fentanyl, 1.1% for morphine, and 0.6% for hydromorphone (p = 0.017). These results highlight that the hydromorphone group exhibited the lowest mortality rates among the three cohorts. In terms of healthcare resource utilization, patients in the fentanyl group exhibited longer median ICU length of stay compared to those in the morphine and hydromorphone groups. (2.0 days versus 1.5 days and 1.4 days, p < 0.001). A comparable pattern was evident in the total duration of hospitalization across the three cohorts.Furthermore, the hydromorphone group demonstrated significantly better outcomes in terms of organ support-free days within 28 days. The days without vasoactive agents were 27.3 ± 2.1 days, and the days without ventilators were 27.5 ± 2.0 days. These results surpassed those observed in the fentanyl and morphine groups (all p < 0.001), suggesting a faster recovery of circulatory and respiratory functions.These findings indicate that following baseline characteristic adjustment, the administration of morphine and hydromorphone—particularly hydromorphone—was associated with superior clinical outcomes relative to fentanyl.

Outcomes

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between postoperative opioid use (fentanyl, morphine, and hydromorphone) and POD risk. In the unadjusted analysis, morphine (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.41–0.54) and hydromorphone (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.31–0.47) exhibited significantly lower POD risks than fentanyl (reference group), with all p values < 0.001. After adjusting for potential confounding factors in multivariate models, this protective association remained statistically significant. Morphine was linked to a 60% reduction in POD risk (adjusted OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.34–0.48), while hydromorphone showed a 54% reduction (adjusted OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.37–0.57), both with p < 0.001. In matched cohorts, morphine (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.31–0.56) and hydromorphone (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.28–0.51) continued to yield significantly better outcomes than fentanyl (both p < 0.001). All models suggest that postoperative use of morphine or hydromorphone may substantially reduce POD risk compared to fentanyl.

Association between postoperative opioids and delirium risk after cardiac surgery across unadjusted, multivariable-adjusted, and propensity score-matched models. The forest plot displays the results of three analytical models comparing morphine and hydromorphone to fentanyl (reference): unadjusted (crude), multivariable-adjusted (for all covariates listed in Supplementary Table S2), and propensity score-matched (1:1:1 nearest-neighbor matching, caliper = 0.2 SD). Point estimates (odds ratios) and their 95% CIs are shown. Estimates below the vertical line of null effect (OR = 1) indicate a statistically significant protective effect (two-sided p < 0.001). SD, standard deviation; OR, odds Ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table 2 shows the direct comparison of hydromorphone versus morphine regarding POD risk in cardiac surgery. In multivariate models, the odds ratio for hydromorphone was 0.96 (95% CI 0.74–1.23), indicating no significant difference in POD risk between the two agents. After PSM, the OR for hydromorphone slightly decreased but remained insignificant (p = 0.595). These findings suggest hydromorphone and morphine have comparable effects on POD risk in cardiac surgery.

In PSM cohort analysis (n = 711 per group), the hydromorphone group showed a significant advantage in mortality outcomes. Compared to the fentanyl group, the hydromorphone group had a 93% lower ICU mortality risk (OR 0.07, 95% CI 0.01–0.53) and a 75% lower hospitalization-related mortality risk (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.08–0.74).However, due to the small sample size, the significant reduction in ICU mortality should be interpreted with caution.However, morphine showed no statistically significant benefit in mortality (p > 0.05) (Table 3).

Compared to fentanyl, morphine and hydromorphone significantly increased organ support-free days within 28 days. hydromorphone demonstrated more pronounced effects, with 1.21 additional ventilator-free days (95% CI 0.79–1.62) and 1.26 additional pressor-free days (95% CI 0.84–1.69). Morphine also showed improvement but to a lesser extent (ventilator-free days: coefficient 0.63, 95% CI 0.22–1.05; pressor-free days: coefficient 0.76, 95% CI 0.34–1.18) (Table 3).

Regarding hospitalization duration, both morphine and hydromorphone groups showed significantly better outcomes than the fentanyl group. Specifically, the hydromorphone group showed the most notable reduction in ICU length of stay (coefficient = − 1.45, 95% CI − 1.89 to − 1.00). For total hospitalization duration, the morphine group demonstrated the greatest reduction (coefficient = − 2.03, 95% CI − 2.68 to − 1.38), followed by the hydromorphone group (coefficient = − 1.86, 95% CI − 2.51 to − 1.21) (Table 3).

Subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis

Subgroup analysis further examined the association between postoperative use of morphine and hydromorphone and POD risk (Fig. 3). Across subgroups defined by age (< 65 vs. ≥ 65 years), BMI (< 24 vs. ≥ 24 kg/m2), emergency surgery status (yes/no), hospitalization stage (early, intermediate, late), and CPB-OHS, both morphine and hydromorphone significantly reduced POD incidence compared to fentanyl (OR < 1). Notably, in most subgroups, hydromorphone’s point estimates were consistently lower than those of morphine, indicating a trend toward superior efficacy. All interaction tests were statistically nonsignificant, suggesting that these patient characteristics did not significantly moderate the effects.

Subgroup Analysis Forest Plot.The forest plot displays OR and 95% CI for POD risk in different patient subgroups within propensity score-matching cohorts, compared with fentanyl. Subgroup variables include age (< 65 vs. ≥ 65 years), gender (female vs. male), body mass index (BMI < 24 vs. ≥ 24 kg/m2), and Emergency operation (No vs. Yes), Admission epoch (Early, Middle and Late), and CPB-OHS (No vs. Yes). For each subgroup, POD incidence rates and corresponding OR values (95% CI) for both hydromorphone and morphine groups are plotted. The figure also presents interaction P-values to evaluate consistency of subgroup effects. The effect size is expressed as OR values, where < 1 indicates lower POD risk. BMI, body mass index; CPB-OHS, cardiopulmonary bypass-assisted open-heart surgery; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

To evaluate the robustness of the study results against unmeasured confounding factors, we conducted E-value analysis. In multivariate models, morphine exhibited greater robustness than fentanyl with an E-value of 4.44 (95% CI 3.59), while hydromorphone showed robustness with an E-value of 3.77 (95% CI 2.90). hydromorphone’s robustness further increased to E = 4.70 (95% CI 3.33) in PSM analysis. All E-values exceeded 3.7, indicating that a risk ratio of greater than 3.7 from strong unmeasured confounding factors would be required to invalidate the conclusions(Table 4).

To evaluate the potential impact of CPB-OHS on POD risk, we included CPB-OHS as a key covariate in all statistical models. Fig. S2 presents the association analysis results between opioids and POD risk under three statistical models. In the unadjusted analysis, both morphine (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.41–0.54) and hydromorphone (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.31–0.47) showed a significant reduction in POD risk compared to fentanyl (p < 0.001). In multivariate models, the protective effect remained significant after controlling for CPB-OHS and other potential confounders. The OR for the morphine group was 0.57 (95% CI 0.44–0.73), and for hydromorphone it was 0.51 (95% CI 0.41–0.63). After PSM combined with multivariate adjustment, morphine still showed significant risk reduction, while hydromorphone exhibited even more pronounced protective effects, reducing POD risk by 43% and 58%, respectively. The analysis indicates that the efficacy of morphine, particularly hydromorphone, in reducing POD remains consistent across patients with different CPB-OHS, suggesting its therapeutic benefits are not affected by CPB-OHS.

We directly compared the effects of hydromorphone and morphine on POD risk to the potential impact of CPB-OHS.As Table S4 shows, in a multivariate model, hydromorphone’s OR was 0.82 (95% CI 0.60–1.11), which did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.192). In a propensity score-matching multivariate model, hydromorphone showed a larger risk reduction trend (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.43–1.15), corresponding to a 30% risk decrease, but remained statistically insignificant (p = 0.16). Despite the lack of statistical significance, all models demonstrated lower POD risk point estimates for hydromorphone. This trend became more pronounced In the PSM model, (OR decreased from 0.82 to 0.70), offering valuable directions for future research.

Table S5 shows that in patients undergoing CPB-OHS, both morphine and hydromorphone were linked to a significantly lower risk of POD than fentanyl, with a significant dose-response trend.Hydromorphone showed the lowest incidence of POD in this subgroup. In the non-CPB-OHS subgroup, morphine and hydromorphone also demonstrated a significant risk reduction, with consistent trend tests. Although the protective effect was more pronounced in the CPB-OHS subgroup, both subgroups consistently indicated that morphine and hydromorphone were superior to fentanyl.

In multivariate models incorporating CPB-OHS, morphine and hydromorphone had E-values of 2.90 and 3.33, respectively. After PSM analysis, hydromorphone’s E-value increased to 4.19, indicating stronger association robustness (Table S3). Overall, the high E-values across all models indicate that the POD risk reduction linked to morphine and hydromorphone compared to fentanyl is credible and unlikely to be invalidated by unmeasured confounding factors.

To assess how changes in opioid exposure definitions might affect the study results, we performed sensitivity analyses using two morphine milligram equivalent (MME) thresholds (80% and 60%). At the 80% MME threshold, unadjusted models showed that morphine (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.41–0.55) and hydromorphone (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.32–0.49) were both linked to a significantly lower risk of POD than fentanyl (both p < 0.001). After multivariable adjustment, these protective associations remained significant (morphine: aOR 0.53, 95% CI 0.41–0.68; hydromorphone: aOR 0.50, 95% CI 0.40–0.63; both p < 0.001). A significant dose-response relationship was indicated by trend tests (p for trend < 0.001), with the lowest POD incidence in the hydromorphone group (8.6%). At the 60% MME threshold, the results were consistent. In adjusted models, morphine (aOR 0.58, 95% CI 0.46–0.75) and hydromorphone (aOR 0.53, 95% CI 0.43–0.66) continued to outperform fentanyl (Table S6). The dose-response trend remained significant (p for trend < 0.001), reinforcing the consistency in risk reduction across opioids. In summary, using either the 80% or 60% MME threshold to define exposure, both morphine and hydromorphone were significantly associated with a lower risk of POD, with hydromorphone showing a stronger protective effect. The trend analysis also supported a dose-dependent relationship between opioid selection and POD risk, strengthening the study’s conclusions.

Discussion

-

In this PSM cohort study of adult cardiac surgery patients, after adjusting for covariates, we found that postoperative use of morphine and hydromorphone was associated with reduced POD risk compared to fentanyl, with hydromorphone showing a more pronounced association during the ICU length of stay.

-

Our findings are in line with mechanistic evidence indicating that highly lipophilic opioids can activate glial cells via TLR4 and NLRP3 inflammasome pathways, promoting neuroinflammation17,18,19. The association between commonly used potent opioids (such as morphine, fentanyl, and oxycodone) and POD remains unclear. Tanaka et al. found a higher incidence of morphine-induced POD in cancer patients compared to fentanyl20. A Japanese multicenter trial observed similar POD rates between fentanyl and oxycodone in patients with cancer pain21. Casamento et al. noted that fentanyl resulted in higher POD rates during hospitalization than morphine14. Wang et al. demonstrated that perioperative use of morphine reduced POD risk compared to fentanyl22. However, existing studies, often limited by small sample sizes and heterogeneous cohorts, have yielded conflicting conclusions. However, existing studies often yield conflicting conclusions due to small sample sizes and significant cohort heterogeneity. A prospective cohort study of 560 patients aged 70 years or older undergoing elective non-cardiac surgery demonstrated no significant association between postoperative opioid use and the incidence of delirium during hospitalization23. Another study focusing on elderly patients undergoing spinal surgery demonstrated that postoperative delirium was associated with pain intensity, but not with the total dosage of opioids administered24. Our analysis demonstrated that hydromorphone and morphine was associated with a 58–62% reduction in the incidence of POD compared to fentanyl after cardiac surgery.

-

Furthermore, postoperative analgesia based on hydromorphone was associated with lower mortality rates, reduced ICU and hospital length of stay, and more vasopressor- and ventilator-free days within 28 days.

-

Analysis of our data revealed that hydromorphone was associated with a significant reduction in mortality, whereas morphine did not confer a statistically significant mortality benefit. However, we must exercise caution when interpreting the significant reduction in ICU mortality rates associated with hydromorphone. The extremely low number of deaths in the hydromorphone group (n = 1) suggests that the estimated effect may be unstable and potentially exaggerated, possibly due to unmeasured confounding factors or random variation. Thus, this finding should be considered preliminary and viewed as a hypothesis rather than a definitive conclusion.The survival advantage of hydromorphone and its 28-day efficacy may stem from its lower lipophilicity (less than fentanyl) and absence of active metabolites like morphine-3-glucuronide, thereby reducing organ toxicity.

-

In this study, postoperative use of hydromorphone for pain management was associated with potential benefits for cardiac surgery patients. However, conflicting evidence persists in existing literature. Notably, a multicenter prospective study in Japan found no statistically significant difference in POD risk between fentanyl and hydromorphone for cancer pain patients21. This discrepancy may be due to the unique high-risk factors experienced by cardiac surgical patients, including heightened systemic inflammation and physiological stress conditions.

-

While our study focused on cardiac surgery patients, the findings suggest hydromorphone’s benefits may also apply to other high-risk groups experiencing significant physiological stress or inflammation, such as those undergoing major thoracic/abdominal surgery, trauma, or sepsis. However, these conclusions require validation through prospective studies in diverse populations. Conversely, differences between these opioids may be negligible in low-risk surgical settings or patients with minimal inflammatory burden.

-

Lastly, it is essential to monitor for hydromorphone’s potential adverse effects, particularly respiratory depression. The respiratory depression caused by hydromorphone primarily results from suppression of the brainstem respiratory center, which significantly reduces respiratory rate and ventilation, ultimately leading to carbon dioxide retention and hypoxemia25,26,27. This effect is dose-dependent and influenced by factors such as patient age, renal function, and concomitant sedative use. Unlike opioids like morphine, high-dose hydromorphone may induce more severe respiratory depression25,28. Clinical guidelines recommend starting with low doses and gradually adjusting based on individual conditions to minimize risks. In this study, no significant increase in respiratory depression risk was observed in the hydromorphone group, likely due to ICU’s comprehensive monitoring system—including continuous vital signs monitoring (e.g., pulse oximetry, partial pressure of carbon dioxide), standardized sedation management protocols, and regulated weaning procedures—which played a crucial role in reducing associated risks.

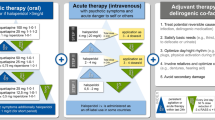

The results of this study demonstrate that postoperative analgesia with hydromorphone after cardiac surgery is associated with a lower risk of POD. Furthermore, its use was linked to reductions in ICU and hospital length of stay. These findings carry economic implications, as the shortened hospitalization directly translates into substantial cost savings for the healthcare system.Although the findings are derived from observational data necessitating validation through prospective randomized controlled trials, these findings support the integration of hydromorphone into multidisciplinary ERAS protocols for high-risk cardiac surgery patients. A collaborative approach involving anesthesiology, cardiothoracic surgery, ICU, and nursing teams is essential to implement a multimodal analgesic strategy that effectively combines hydromorphone with non-opioid analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen, NSAIDs) and regional anesthesia techniques. Such an approach not only has the potential to decrease the overall risk of POD and improve patient outcomes but also to reduce total opioid consumption and alleviate the broader healthcare economic burden.

A pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial should compare weight-based hydromorphone (0.02 mg kg−1 h−1) with fentanyl (2 µg kg−1 h−1) initiated within 24 h of cardiac surgery. Primary endpoints should include delirium-free days and 30-day all-cause mortality. Parallel mechanistic substudies should concurrently quantify causal pathways using biomarkers (e.g., neuro-inflammatory cytokines) and electroencephalographic burst-suppression patterns.

Methods

Ethics

This retrospective cohort study analyzed data from the MIMIC-IV database (version 3.1, 2008–2022) and adhered to the STROBE statement29 The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB No.2001-P-001699/14) at MIT and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. All researchers hold biomedical ethics certification from the CITI Project (Certificate No.39099161). To protect patient privacy, all patient information in the database was anonymized. Given the study’s retrospective design and use of anonymized data, the Institutional Review Board waived the requirement for informed consent.

Data source and patient selection

Cardiac surgical cases were identified using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes, which are detailed in online supplementary material Table S1. The study cohort was primarily composed of patients who underwent cardiopulmonary bypass-assisted open-heart surgery (CPB-OHS), as this reflects the mainstream clinical practice within the database. Meanwhile, to make the cohort more in line with real-world clinical populations, patients who underwent open-heart surgeries without cardiopulmonary bypass were also included.Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age ≥ 18 years; (2) ICU length of stay for at least 24 h; (3) receipt of > 70% of postoperative 24-h morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) as fentanyl, morphine, or hydromorphone during the ICU length of stay; and (4) Underwent cardiac surgery in accordance with the aforementioned surgical definition. Exclusion criteria were age < 18 years, ICU length of stay < 24 h, any readmission (only the first hospitalization and first ICU admission records were retained), and absence of survival data. Patients were categorized into different exposure groups based on opioids accounting for over 70% of total 24-hour mean monitoring data (MME). The threshold selection aims to define a primary exposure measure, enhance inter-group comparability by limiting the inclusion of patients with mixed medication regimens, and align with standard practices in similar database studies to balance cohort purity and statistical power30,31,32.Ultimately, 8246 patients fulfilled all criteria (fentanyl 3612; morphine 3077; hydromorphone 1557).

Data extraction and variables

Data were extracted from the MIMIC-IV relational database (PostgreSQL 13.0). Variables included: (1) demographics (age, sex, BMI, admission time period); (2) vital signs (heart rate, mean arterial pressure, SpO2). All vital signs data were collected and computed as the mean value over the first 24 h following ICU admission. (3) laboratory indices (white blood cell, haematocrit, creatinine, lactate); (4) comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, sepsis, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, liver disease, renal disease, dementia, alcohol abuse); (5) Severity Scores (SOFA, SAPS II, Charlson Comorbidity Index); (6) Clinical Conditions (sepsis-3, hypotension occurred, emergency Operation); (7) Treatments (vasopressor therapy, mechanical ventilation, benzodiazepines, dexmedetomidine); (8) opioid exposure (fentanyl, morphine, hydromorphone); and (9) outcomes—primary: ICU delirium; secondary: ICU mortality, hospital mortality, vasopressor- and ventilator-free days within 28 days, ICU length of stay, and hospital length of stay. Biochemical variables were recorded at ICU admission and before any therapeutic intervention. Custom extraction scripts, available at the referenced repository, were employed. Variables with > 20% missing values were excluded; for the remainder, single imputation was applied.

Variable definitions

The morphine milligram equivalent (MME) administered during the ICU length of stay standardises doses among opioid analgesics by referencing morphine as the common denominator33,34. Equivalence ratios are 1 mg morphine = 1 MME, 1 mg hydromorphone ≈ 5 MME, and 1 mcg intravenous fentanyl ≈ 0.1 MME33,34.

ICU delirium was evaluated with the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) and defined according to DSM-5 criteria35.If the patient has at least one positive (Positive) CAM-ICU assessment result, the patient is considered a POD positive case. This is performed by a trained doctor and nurse during the daily clinical evaluation of the patient’s ICU length of stay.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The language has been polished by GPT4.0 to enhance readability.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation when normally distributed or as median [interquartile range] otherwise; categorical data were summarised as frequency (%). Between-group comparisons were performed with the χ2 or Fisher exact test for categorical variables, one-way ANOVA for normally distributed continuous variables, and Kruskal–Wallis test for non-normally distributed variables.

Participants were matched 1:1:1 by nearest-neighbour propensity scores with a caliper of 0.2 and without replacement. All covariates listed in Supplementary Table S2 online were incorporated. Balance was evaluated with SMD, and values < 0.1 indicated adequate balance. The final matched cohort comprised 711 patients in each group (N = 2103; Fig. S1)..

Primary outcome measure (POD): Multivariate logistic regression was used, with results presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Mortality outcomes: Risk ratios were calculated using a modified Poisson regression model with robust variance estimation. ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, vasopressor- and ventilator-free days within 28 days: Linear regression analysis was performed after Box–Cox transformation.

To evaluate the robustness of our findings, we performed sensitivity analyses. In the full cohort, the primary outcome measures were compared under three conditions: unadjusted, multivariate-adjusted (including all covariates in Table S2), and propensity score adjustment. Multivariate logistic regression models were used for subgroup analysis and interaction testing of the primary outcomes, with p-values < 0.05 indicating statistically significant interactions. Subgroup stratification was performed based on age, BMI, emergency surgery status, admission time window, and CPB-OHS, with interaction term tests assessing effect modification. To validate the model specification, we conducted sensitivity analyses: introducing CPB-OHS as an additional covariate to assess result consistency under alternative models; using E-value analysis to quantify the potential impact of unmeasured confounders on association effects; and redefining opioid exposure using 60% and 80% MME thresholds, followed by repeated primary analyses to assess stability under different exposure definitions.

Analyses were performed with Free Statistics software v2.2.1 and R 4.5.1 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria); two-sided P < 0.05 denoted statistical significance.

Limitations

This study achieved balanced baseline covariates across groups using rigorous PSM (SMD < 0.1) and validated the findings with multi-model sensitivity analysis. However, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results. Firstly, The MME transformation employed in this study was intended to standardise exposure levels, but it failed to adequately consider critical pharmacokinetic differences among opioids, particularly with regard to their duration of action. This may result in exposure misclassification and bias in effect estimation. Secondly, residual confounding factors may remain. These may include intraoperative details, genetic polymorphisms affecting opioid metabolism, and pain management—none of which could be objectively quantified.Thirdly, there are limitations to delirium assessment. While the CAM-ICU is the gold standard for ICU delirium screening, it may underestimate low-activity delirium, potentially resulting in an underestimation of its prevalence post-surgery. The timing of the assessment may coincide with opioid administration, potentially capturing transient sedation caused by the drug rather than true delirium. This could lead to an overestimation of delirium occurrence based on a single positive CAM-ICU assessment. Meanwhile, the MMSE is unsuitable for diagnosing POD in ICUs. Fourthly, the data were collected from a single academic medical center. Despite stringent inclusion criteria and statistical adjustments, results may be affected by institution-specific treatment protocols when generalized. Fifth, retrospective database studies afford large sample sizes. However, electronic medical records inadequately capture the rationale underlying clinical decisions, thereby introducing indicator bias.These limitations should be addressed in future research through multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled trials designed to establish the causal relationship between opioid use and POD.

Conclusion

This retrospective cohort study compared the associations between early postoperative use of fentanyl, morphine, and hydromorphone and the risk of POD and other clinical outcomes following cardiac surgery. PSM analysis revealed that compared to fentanyl, postoperative hydromorphone was associated with a significantly lower risk of POD, lower mortality, shortened ICU and hospital length of stay, and more organ support-free days within 28 days. Morphine, whereas also associated with a lower risk of POD, shortened ICU and hospital length of stay, and more organ support-free days within 28 days, was not significantly associated with a reduction in mortality.These findings highlight important clinical associations and underscore the necessity of further research, particularly randomized controlled trials, to confirm potential causal relationships.

Data availability

Data are publicly available through the MIMIC-IV database (https://mimic-iv.mit.edu/).

References

Chen, Z. et al. Predictive value of the geriatric nutrition risk index for postoperative delirium in elderly patients undergoing cardiac surgery. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 30, e14343 (2024).

Kim, M. S. & Kim, S. H. Risk factors for postoperative delirium in patients with cardiac surgery. Sci. Prog. 107, 368504241266362 (2024).

Mattimore, D. et al. Delirium after cardiac surgery-a narrative review. Brain Sci. 13, 1682 (2023).

Gonçalves, M. C. B. et al. Multivariable predictive model of postoperative delirium in cardiac surgery patients: proteomic and demographic contributions. Anesth. Analg. 140, 476–487 (2025).

Mangusan, R. F., Hooper, V., Denslow, S. A. & Travis, L. Outcomes associated with postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery. Am. J. Crit. Care. 24, 156–163 (2015).

de la Varga-Martínez, O. et al. Postoperative delirium: an independent risk factor for poorer quality of life with long-term cognitive and functional decline after cardiac surgery. J. Clin. Anesth. 85, 111030 (2023).

Sugimura, Y. et al. Risk and consequences of postoperative delirium in cardiac surgery. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 68, 417–424 (2020).

Cohen, C. L., Atkins, K. J., Evered, L. A., Silbert, B. S. & Scott, D. A. Examining subjective psychological experiences of postoperative delirium in older cardiac surgery patients. Anesth. Analg. 136, 1174–1181 (2023).

McKay, T. B. et al. Associations between Aβ40, Aβ42, and Tau and postoperative delirium in older adults undergoing cardiac surgery. J. Neurol. 272, 393 (2025).

Echeverria-Villalobos, M. et al. The role of neuroinflammation in the transition of acute to chronic pain and the opioid-induced hyperalgesia and tolerance. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1297931 (2023).

Swart, L. M., van der Zanden, V., Spies, P. E., de Rooij, S. E. & van Munster, B. C. The comparative risk of delirium with different opioids: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 34, 437–443 (2017).

Fong, H. K., Sands, L. P. & Leung, J. M. The role of postoperative analgesia in delirium and cognitive decline in elderly patients: a systematic review. Anesth. Analg. 102, 1255 (2006).

Sugiyama, Y. et al. Incidence of delirium with different oral opioids in previously opioid-naive patients. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care. 39, 1145–1151 (2022).

Casamento, A. et al. Delirium in ventilated patients receiving fentanyl and morphine for analgosedation: findings from the ANALGESIC trial. J. Crit. Care. 77, 154343 (2023).

Reisinger, M., Reininghaus, E. Z., Biasi, J. D., Fellendorf, F. T. & Schoberer, D. Delirium-associated medication in people at risk: a systematic update review, meta‐analyses, and GRADE‐profiles. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 147, 16–42 (2023).

Huang, Q. et al. Hydromorphone reduced the incidence of emergence agitation after adenotonsillectomy in children with obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized, double-blind study. Open Med. 20, (2025).

Carranza-Aguilar, C. J. et al. Morphine and fentanyl repeated administration induces different levels of NLRP3-dependent pyroptosis in the dorsal Raphe nucleus of male rats via cell-specific activation of TLR4 and opioid receptors. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 42, 677–694 (2022).

Zhang, P. et al. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/opioid receptor pathway crosstalk and impact on opioid analgesia, immune function, and Gastrointestinal motility. Front. Immunol. 11, (2020).

Stevens, C., Aravind, S., Das, S. & Davis, R. Pharmacological characterization of LPS and opioid interactions at the toll-like receptor 4. Br. J. Pharmacol. 168, 1421–1429 (2013).

Tanaka, R. et al. Incidence of delirium among patients having cancer injected with different opioids for the first time. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 34, 572–576 (2017).

Hiratsuka, Y. et al. Prevalence of opioid-induced adverse events across opioids commonly used for analgesic treatment in japan: a multicenter prospective longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 31, 632 (2023).

Zhong, J., Sui, R., Zi, J. & Wang, A. Comparison of the effects of perioperative Fentanyl and morphine use on the short-term prognosis of patients with cardiac surgery in the ICU. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1453835 (2025).

Duprey, M. S. et al. Association between perioperative medication use and postoperative delirium and cognition in older adults undergoing elective noncardiac surgery. Anesth. Analg. 134, 1154 (2022).

Sica, R. et al. The relationship of postoperative pain and opioid consumption to postoperative delirium after spine surgery. J. Pain Res. 16, 287–294 (2023).

Babalonis, S. et al. Relative potency of intravenous oxymorphone compared to other µ opioid agonists in humans - pilot study outcomes. Psychopharmacol. (Berl). 238, 2503–2514 (2021).

Babalonis, S., Lofwall, M. R., Nuzzo, P. A. & Walsh, S. L. Pharmacodynamic effects of oral oxymorphone: abuse liability, analgesic profile and direct physiologic effects in humans. Addict. Biol. 21, 146–158 (2016).

Baldo, B. A. & Rose, M. A. Mechanisms of opioid-induced respiratory depression. Arch. Toxicol. 96, 2247–2260 (2022).

Khanna, A. K. et al. Prediction of opioid-induced respiratory depression on inpatient wards using continuous capnography and oximetry: an international prospective, observational trial. Anesth. Analg. 131, 1012–1024 (2020).

von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) St atement: guidelines for reporting observational studies*. Bull. World Health Organ. 85, 867–872 (2007).

Liu, H. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index correlates with the incidences and prognoses of cardiac arrest following acute myocardial infarction: data from two large-scale cohorts. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 24, 108 (2025).

Asamoah-Boaheng, M., Bonsu, O., Farrell, K., Oyet, J., Midodzi, W. K. & A. & Measuring medication adherence in a population-based asthma administrative pharmacy database: A systematic review and meta-analysis. CLEP 13, 981–1010 (2021).

Hayes, K. N., Cadarette, S. M. & Burden, A. M. Methodological guidance for the use of real-world data to measure exposure and utilization patterns of osteoporosis medications. Bone Rep. 20, 101730 (2023).

Sa, E. et al. Declines and regional variation in opioid distribution by U.S. Hospitals. Pain. 163, (2022).

Dowell, D., Haegerich, T. M. & Chou, R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain–united states, 2016. JAMA. 315, 1624–1645 (2016).

Gusmao-Flores, D., Salluh, J. I. F., Chalhub, R. Á. & Quarantini, L. C. The confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) and intensive care delirium screening checklist (ICDSC) for the diagnosis of delirium: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies. Crit. Care. 16, R115 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all participants for their invaluable contributions to this study.

Funding

This research is supported by the Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Project No. 2022J011472) and the Doctoral Workstation Project of Zhangzhou Municipal Hospital (Project No. PDB202316).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.X. conceptualized the study. C.S. and J.B. curated the data and performed the formal analysis. Q.-W.H. and L.Z. validated the results. Y.G. provided critical guidance on the formal analysis and contributed to manuscript review. H.L. supervised the project and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

All authors have reviewed the manuscript and have given their consent for its publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, L., Su, C., Bian, J. et al. Comparative effects of fentanyl, morphine, and hydromorphone on postoperative delirium and outcomes after cardiac surgery: a propensity score-matched cohort study. Sci Rep 15, 45514 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29805-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29805-6