Abstract

Hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia are common complications among critically ill patients. Maintaining blood glucose levels in the normal range is crucial but challenging due to complex influencing factors. This study aimed to develop a machine learning model that predicts hypo- or hyperglycemia 6 h in advance in patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). We analyzed electronic health records of 8,853 ICU patients (1,350,097 records) from a single center in Japan (2010–2022). Hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia were defined as blood glucose levels ≤ 80 mg/dL (4.4 mmol/L) and ≥ 180 mg/dL (10 mmol/L), respectively. We developed prediction models using routinely collected ICU data, including demographic, physiological, laboratory, and treatment variables. Machine learning models were developed using eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), random forest, neural networks, and logistic regression. The XGBoost model demonstrated the highest performance with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.939 and an F1 score of 0.520 for predicting hypoglycemia and an AUC of 0.919 and an F1 score of 0.702 for predicting hyperglycemia. It also achieved high calibration and net benefit. The machine learning models, notably the XGBoost algorithm, accurately predicted glucose abnormalities in critically ill ICU patients. These findings support its potential as a tool for early detection and proactive management of dysglycemia in critical care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Blood glucose abnormalities, including hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, are common among patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). These conditions are associated with complications and an increased risk of mortality1,2,3,4,5. Although maintaining blood glucose levels within an appropriate range is recommended6,7,8, achieving optimal glycemic control remains challenging because critically ill patients often experience fluctuations in their glucose levels due to dysregulated glucose metabolism1,9,10. Developing an algorithm to predict blood glucose levels could assist medical professionals in providing better blood glucose management, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

With advancements in artificial intelligence, several machine learning models predicting the blood glucose levels in outpatients or hospitalized patients with diabetes have been developed and evaluated11,12,13,14,15,16. In contrast, few studies have explored the development of machine learning algorithms for predicting dysglycemia in critically ill patients. One study created a machine learning model that predicts blood glucose levels 2 h in advance using publicly available databases17. Although the study demonstrated acceptable accuracy for glucose levels within the normal range, the model encountered difficulties in predicting hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. Another study developed a model to predict hypoglycemia during ICU stays; however, it lacked short-term predictive ability, limiting its practical application in dynamic blood glycemic management18. This highlights the need for innovative machine learning models that can accurately predict hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia at any point during ICU stays to achieve better glycemic control.

We tested the hypothesis that machine learning algorithms effectively predict glucose abnormalities in critically ill patients. This study focused on developing machine learning models to predict hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia separately, utilizing a large cohort of critically ill patients from a 12-year ICU database comprising 8,853 cases and 1,350,097 records from a single center in Japan.

Methods

Study design and participants

This retrospective study utilized the electronic health record data of consecutive patients admitted to the ICU at Chiba University Hospital, Japan, from November 2010 to October 2022. Patients who stayed in the ICU for more than 24 h were included in the study.

Blood glucose levels were measured using blood gas analysis. Records lacking blood gas measurements 6 h before or after the reference time were excluded. Data collected after the initiation of oral food intake were also excluded.

The Ethical Review Board of Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine waived the requirement for written informed consent, and all the methods were in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects in Japan (approval number: 3380).

Definition of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia

Hypoglycemia was defined as blood glucose levels ≤ 80 mg/dL (4.4 mmol/L). Although a threshold of < 70 mg/dL has been well established as being associated with adverse outcomes in critically ill patients1,3 , current guidelines including the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines 20218 recommend maintaining blood glucose levels above 80 mg/dL to avoid clinically significant hypoglycemia. This practical threshold is widely used in ICU settings, where interventions such as nutritional adjustment or insulin dose modification are typically initiated once glucose levels fall below 80 mg/dL. Therefore, we adopted ≤ 80 mg/dL as the operational definition of hypoglycemia in this study.

Hyperglycemia was defined as blood glucose levels ≥ 180 mg/dL (10 mmol/L), consistent with international guidelines, including the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines 20218, which recommend initiating insulin therapy at this threshold.

The primary outcome of this study was the occurrence of hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia 6 h after an arbitrary baseline point.

Data collection

We selected 59 variables from a clinical perspective (Supplementary File: Table S1), including basic information at ICU admission (age, sex, sequential organ failure assessment [SOFA] score, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation [APACHE] II score, and admission route), physiological measurements (vital signs), blood tests, caloric intake from parenteral or enteral nutrition, insulin dosage, and other medications. For the sequential data, the blood glucose level, insulin dosage, and caloric intake through parental and enteral nutrition 6 h and 12 h before the reference time point were included.

Machine learning algorithms

The data were divided into one record per hour, with each record referencing the most recently available data. The dataset was structured on an hourly basis, where each record represented a clinically meaningful prediction point corresponding to the patient’s condition at that hour. Blood glucose measurements were incorporated using their actual measurement intervals (typically every 6 h, but more frequent in unstable conditions such as after insulin initiation, hypoglycemia, or severe hyperglycemia). To maintain generalizability and prevent data leakage, patient data were randomly split on a case-by-case basis to ensure no overlap between the training and test sets (80% training and 20% test cohorts). While missing values remained unchanged for eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), the median values were imputed in the other models.

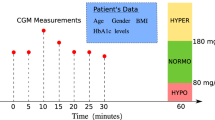

We then developed binary classification models to predict hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia 6 h after an arbitrary time point (Fig. 1). Because we routinely measure and manage blood glucose levels every 6 h at our facility, we selected a 6-h prediction interval. For this study, we created prediction models using XGBoost, which utilizes the gradient boosting method, random forest, and neural networks, which are known for their effectiveness with large datasets, and logistic regression for comparison. For the models utilizing XGBoost and random forest, the hyperparameters were tuned using Bayesian optimization with cross-validation to maximize the F1 score. L2 regularization was applied to the logistic regression analysis. Additionally, cross-validation was conducted to ensure the robustness and generalizability of the models.

Study overview. This study used 59 variables from admission data, past data, and recent data, as shown below, to develop a machine learning model that predicts hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia 6 h in advance. XGBoost: eXtreme Gradient Boosting, ICU: intensive care unit, SOFA: sequential organ failure assessment, APACHE: acute physiology and chronic health evaluation, EN/PN: enteral/parenteral.

Evaluation of machine learning models

In our primary analysis, we used the area under the curve (AUC) as the key evaluation metric for the model. We also evaluated other metrics, such as accuracy, F1 score, precision-recall (PR)-AUC, calibration plot, and decision curve analysis (DCA). The cutoff value was determined using the Youden index, and the sensitivity and specificity were calculated. We selected the F1 score and PR-AUC as evaluation metrics, because they are well-suited for measuring the prediction performance in imbalanced datasets. This is particularly useful in our case, as the occurrences of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia are relatively rare. The F1 score is the harmonic mean of the precision and recall, which measures a model’s balance between false positives and false negatives. The PR curve shows the precision (positive predictive value) and recall (sensitivity) across different threshold settings. For further evaluation, we created a calibration plot to assess the reliability of the model’s predicted probabilities by comparing how well the predicted probabilities matched the actual observed rates. The Brier score was calculated to measure the accuracy of our probabilistic predictions by assessing the mean squared difference between the predicted probabilities and actual rates. Finally, the DCA demonstrated the clinical utility of the model by showing the net benefit at various threshold levels. The net benefit was calculated as the true positive rate minus the false positive rate.

The main Python packages used in the analysis to create the machine learning algorithms were Python 3.11.4, pandas 2.0.3, numpy 1.24.0, matplotlib 3.8.2, scikit-learn 1.2.3, XGBoost 2.0.3, and shap 0.44.1.

Analysis of key factors contributing to blood glucose prediction

To assess the effects of the features, we have provided the summary plots of the Shapley additive explanation (SHAP) values, which illustrate the extent of each feature’s contribution to the model’s predictions. The SHAP value indicates the impact of each feature on the model output, with higher interpretability in machine learning models. We expressed the SHAP value as an absolute number, reflecting a positive or negative association between the variable and the outcome. SHAP individual force plots used a color scale to display the contribution of each feature to the onset of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia in individual instances.

Subgroup analysis

For the subgroup analyses, we trained separate XGBoost models for each subgroup and compared their AUC and 95% confidence intervals (CI). The subgroups were categorized based on the following three variables: insulin administration (yes/no), body mass index (BMI) (≥ 25 kg/m2 or < 25 kg/m2), and SOFA score (≥ 11 or < 11). The analysis aimed to evaluate the performance of the model across specific patient populations.

These variables were selected for their clinical significance in influencing insulin resistance and metabolism. Insulin administration identified patients undergoing active insulin treatment, which is a key factor in glycemic management. Obesity, defined as BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 according to the World Health Organization classification19 and the Japan Obesity Society criteria20, highlights patients at a higher risk of insulin resistance. To identify critically ill patients, the SOFA score threshold of ≥ 11 was used based on its established association with poor prognosis21,22, where hypermetabolism is likely to exacerbate insulin resistance.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

Of the 11,005 cases and 1,673,592 records of patients who stayed in the ICU for over 24 h, 2152 cases and 323,495 records were excluded based on the exclusion criteria. Consequently, 8,853 cases and 1,350,097 records were included in this study (Fig. 2).

Among the 8,853 cases analyzed, 1942 (21.9%) patients experienced hypoglycemia at least once during their ICU stay, while 4,930 (55.7%) experienced hyperglycemia. Insulin therapy was administered to 2,841 patients (32.1%). The median SOFA score was 6, and the ICU mortality rate was 7.5% (Table 1).

Performances of the prediction models

Compared to the other models, the XGBoost model demonstrated superior performance in predicting both hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia 6 h in advance, with an AUC of 0.939 (95% CI 0.935–0.942) and an F1 score of 0.520 for hypoglycemia and an AUC of 0.919 (95% CI 0.918–0.920) and an F1 score of 0.702 for hyperglycemia (Table 2). As observed in the calibration plot, the XGBoost model exhibited the highest calibration, with Brier scores of 0.014 and 0.088 for the prediction of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, respectively. Furthermore, the DCA of the XGBoost model displayed the highest net benefit across a range of threshold probabilities compared to the other models (Fig. 3).

Visualization of prediction model performances for hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia 6 h in advance among intensive care unit patients. (A) ROC curve of four machine learning models. (B) PR curve shows the precision and recall across different threshold settings. (C) Calibration plot shows the consistency between predicted probability and actual rate. (D) Decision curves used to evaluate the net benefit for various threshold settings. Hypoglycemia: blood glucose level ≤ 80 mg/dL (4.4 mmol/L), Hyperglycemia: blood glucose level ≥ 180 mg/dL (10 mmol/L). ROC: receiver operating characteristics, PR: precision-recall, XGBoost: eXtreme Gradient Boosting, AUC: area under the curve. (a) Performances of models predicting hypoglycemia. (b) Performances of models predicting hyperglycemia.

Factors contributing to blood glucose prediction

According to the SHAP values, sequential blood glucose levels were the most significant variables for predicting hypoglycemia in both models. Other key variables included insulin dosage, caloric intake from parenteral or enteral nutrition, lactate levels, and body weight (Fig. S1).

Subgroup analyses

The cohort of patients not receiving insulin presented higher accuracy in predicting hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia than those receiving insulin (Fig. 4). No significant differences were observed between groups classified based on the SOFA score (≥ 11 or < 11) and BMI (≥ 25 kg/m2 or < 25 kg/m2) thresholds.

Subgroup analyses of the prediction algorithms. We trained the XGBoost model separately for each subgroup to predict hypoglycemia (A) and hyperglycemia (B). The AUC and 95% CI are presented in a forest plot. The numbers of data points and positive labels in each group are also shown. Hypoglycemia: blood glucose level ≤ 80 mg/dL (4.4 mmol/L); Hyperglycemia: blood glucose level ≥ 180 mg/dL (10 mmol/L). AUC: area under the curve; CI: confidence interval, BMI: body mass index; SOFA score: sequential organ failure assessment score. A: Forest plot of prediction models for hypoglycemia. B: Forest plot of prediction models for hyperglycemia.

Discussion

In this study, we developed machine learning models to predict hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia 6 h in advance for critically ill patients using ICU data from a single center in Japan. The model built with XGBoost demonstrated the best performance among the models constructed. However, the predictive accuracy for insulin users was a challenge.

Previous studies reported that the AUCs for machine learning models predicting hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients with diabetes ranged from 0.71 to 0.9611,12,13,14,23, while those for models predicting hyperglycemia ranged from 0.87 to 0.9113,16. Predicting blood glucose levels in critically ill patients is challenging due to severe illness, inflammation, and complex metabolic factors. Despite this, our model outperformed previous models, achieving an AUC of 0.939 for hypoglycemia and 0.919 for hyperglycemia.

A previous study developed a machine learning model using MIMIC-III data to predict ICU patients’ blood glucose levels 2 h in advance17. Although the model achieved high accuracy within the normal range, it faced challenges in predicting hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia. The use of a regression model with numerical results as outcomes contributed to these challenges24. Although methods such as random forest and XGBoost improve normal range accuracy, they often reduce the accuracy for extreme values. Additionally, the infrequency of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia compared to normal glucose levels may have biased the model toward normal patterns24,25. Moreover, predicting all ranges of blood glucose levels using a single model is challenging because the causes of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia differ. Therefore, we treated hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia as separate classes and developed distinct models to predict each condition, thereby improving the performance for extreme values. Our model achieved an AUC of 0.939 and an F1 score of 0.520 for hypoglycemia prediction, which were significantly better than those reported previously (AUC of 0.899 and F1 score of 0.134) 17,24.

Additionally, the quality of our hospital’s database significantly enhanced prediction accuracy. Accurate recording of nutritional intake, including parenteral and enteral nutrition, is essential for effective blood glucose prediction models. However, capturing such data is challenging owing to the wide variety of formulations available. Frequent minor name alterations caused by changes in product names and shifts to products from different manufacturers make it difficult to capture all drug names comprehensively. Additionally, enteral nutrition records often involve manual entry of formulation names, causing inconsistencies and errors. A previous study reported that nutritional intake information in the form of enteral and parenteral nutrition was available for 18.0% and 3.5% of admissions, respectively17. In contrast, our hospital’s database has addressed these challenges by striving to record parenteral and enteral nutrition data comprehensively and accurately. This enhanced data quality has played a crucial role in improving the performance of the blood glucose prediction model in this study.

The other model predicted hypoglycemic events (blood glucose level < 72 mg/dL) during the ICU stay, achieving an AUC of 0.85 and a PR-AUC of 0.4418, outperforming the traditional logistic regression model (AUC of 0.83 and PR-AUC of 0.09)23. However, that model lacks short-term predictions. Our XGBoost model assessed blood glucose levels 6 h in advance with better results, indicating its usefulness in ICU settings for timely and accurate predictions.

The AUCs of the models for hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia were 0.939 and 0.919, respectively, and their F1 scores were 0.571 and 0.767, respectively. The relatively low F1 score of the hypoglycemia prediction model can be attributed to the rarity of hypoglycemia. Among the 1,673,592 records in our dataset, only 28,067 (1.8%) showed hypoglycemia, while 393,138 (25.0%) showed hyperglycemia. This result is consistent with those of previous studies; however, this imbalance often increases false positives and false negatives, leading to lower F1 scores and PR-AUC values. Nevertheless, the F1 score and PR-AUC for hypoglycemia prediction in this study were 0.520 and 0.571, respectively, both of which were considered sufficiently high. Furthermore, the model for hypoglycemia achieved sensitivity and specificity rates of 85.4% and 89.5%, respectively, demonstrating robust performance.

The SHAP value analysis revealed each feature’s contribution to the model’s predictions, showing distinct factors influencing hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia predictions. The impact of nutritional intake and insulin administration from 6 to 12 h before is significant for predicting hyperglycemia. This is probably due to the time needed for nutrient intake and insulin dosage changes to reflect in blood glucose levels. Furthermore, data gathered from multiple time points could be useful for accurately assessing each patient’s insulin resistance, which exhibits significant individual differences. In contrast, short-term factors had a stronger influence on the prediction of hypoglycemia. Blood glucose levels, nutritional intake, and insulin administration at prediction were the top contributing factors, along with lactate levels, pH, and body weight. These findings indicate that short-term effects and severity of illness play a role in predicting hypoglycemia.

The subgroup analyses revealed a decline in the model’s performance among patients receiving insulin therapy. This can be attributed to two factors. First, the rarity of hypoglycemia in this cohort was due to careful treatment practices. Second, the performance of machine learning models tends to decline when physicians determine medication treatments. For instance, a study predicting oliguria in ICU patients reported lower accuracy with diuretic use, and this study showed similar trends26.

The calibration plot of the XGBoost model demonstrated that the predicted probabilities of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia closely aligned with the actual observed incidence. This consistency was observed across all probability ranges, from low to high, indicating that the model avoided overestimation and underestimation, thereby maintaining a stable predictive performance. These results highlight the high reliability of the model’s predictions. Furthermore, the DCA revealed that the model exhibited strong clinical utility across a wide range of thresholds. The model enables appropriate treatment decisions based on the risk of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, helping to minimize overtreatment and undertreatment and maximize the net benefits for patients. Using this predictive model, clinicians can predict the blood glucose levels up to 6 h in advance, enabling timely and precise adjustments to insulin dosing. This proactive approach helps to stabilize blood glucose levels and reduce complications associated with poor glycemic control, such as infections, delayed wound healing, and increased mortality risk. Effective blood glucose management has the potential to improve patient outcomes directly in the ICU, further supporting the practical value of this model.

Despite these promising results, this study has several limitations. First, the data were obtained from a single center, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other populations or settings. Second, the performance of the model decreased in patients who received insulin, leaving room for improvement. This may be because hypoglycemia among insulin users in this dataset was very rare due to careful treatment.

Conclusions

This study developed a highly accurate machine learning algorithm for predicting hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia in critically ill patients. This model has the potential to optimize glycemic management in the ICU, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Data availability

The single-center database from Chiba University Hospital is not publicly available due to privacy restrictions. De-identified data may be provided upon reasonable request with Ethics Committee approval. Requests should be directed to the corresponding author (e-mail: taka.nakada@nifty.com).

References

Egi, M. et al. Hypoglycemia and outcome in critically ill patients. Mayo Clin. Proc. 85(3), 217–224 (2010).

Krinsley, J. S. & Grover, A. Severe hypoglycemia in critically ill patients: Risk factors and outcomes. Crit. Care Med. 35(10), 2262–2267 (2007).

Bagshaw, S. M. et al. The impact of early hypoglycemia and blood glucose variability on outcome in critical illness. Crit. Care 13(3), R91 (2009).

Falciglia, M. et al. Hyperglycemia-related mortality in critically ill patients varies with admission diagnosis. Crit. Care Med. 37(12), 3001–3009 (2009).

Krinsley, J. S. et al. Diabetic status and the relation of the three domains of glycemic control to mortality in critically ill patients: An international multicenter cohort study. Crit Care 17(2), R37 (2013).

Malmberg, K. et al. Effects of insulin treatment on cause-specific one-year mortality and morbidity in diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction. DIGAMI study group. Diabetes insulin-glucose in acute myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 17(9), 1337–1344 (1996).

Malmberg, K. Prospective randomised study of intensive insulin treatment on long term survival after acute myocardial infarction in patients with diabetes mellitus. DIGAMI (diabetes mellitus, insulin glucose infusion in acute myocardial infarction) study group. BMJ 314(7093), 1512–1515 (1997).

Evans, L. et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 47(11), 1181–1247 (2021).

Cook, C. B. et al. Inpatient glucose control: A glycemic survey of 126 U.S. hospitals. J. Hosp. Med. 4(9), E7-e14 (2009).

Robinson, L. E. & van Soeren, M. H. Insulin resistance and hyperglycemia in critical illness: Role of insulin in glycemic control. AACN Clin. Issues 15(1), 45–62 (2004).

Ruan, Y. et al. Predicting the risk of inpatient hypoglycemia with machine learning using electronic health records. Diabetes Care 43(7), 1504–1511 (2020).

Mathioudakis, N. N. et al. Development and validation of a machine learning model to predict near-term risk of iatrogenic hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients. JAMA Netw. Open 4(1), e2030913 (2021).

Zale, A. D. et al. Development and validation of a machine learning model for classification of next glucose measurement in hospitalized patients. EClinicalMedicine 44, 101290 (2022).

Elbaz, M. et al. Predicting hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients with diabetes: A derivation and validation study. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 171, 108611 (2021).

Zale, A. & Mathioudakis, N. Machine learning models for inpatient glucose prediction. Curr. Diab. Rep. 22(8), 353–364 (2022).

Witte, H. et al. Machine learning prediction of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia from electronic health records: Algorithm development and validation. JMIR Form. Res. 6(7), e36176 (2022).

Fitzgerald, O. et al. Incorporating real-world evidence into the development of patient blood glucose prediction algorithms for the ICU. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 28(8), 1642–1650 (2021).

Mantena, S. et al. Predicting hypoglycemia in critically Ill patients using machine learning and electronic health records. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 36(5), 1297–1303 (2022).

Organization, W.H., Obesity and Overweight. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight, 2024. March.

Society, J.O., Guidelines for the Management of Obesity Disease, 2022. http://www.jasso.or.jp/contents/magazine/journal.html, 2022.

Junger, A. et al. Discriminative power on mortality of a modified sequential organ failure assessment score for complete automatic computation in an operative intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 30(2), 338–342 (2002).

Ferreira, F. L. et al. Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. JAMA 286(14), 1754–1758 (2001).

Horton, W. B. et al. Pathophysiologic signature of impending ICU hypoglycemia in bedside monitoring and electronic health record data: Model development and external validation. Crit Care Med 50(3), e221–e230 (2022).

Puhr, R. et al. Firth’s logistic regression with rare events: Accurate effect estimates and predictions?. Stat. Med. 36(14), 2302–2317 (2017).

Jayakody Kankanamalage, C.S., R. Wickramarachchi, and A. Sheth, A Comprehensive Survey on Rare Event Prediction. ACM Computing Surveys, 2024.

Yamao, Y. et al. Machine-learning model for predicting oliguria in critically ill patients. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 1054 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Honyaku Center Inc. for English language editing.

Funding

T.I. has received a grant from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number JP25K21344.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.I. conceived the study, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. S.S., T.I., T.O., E.K., and T.N. contributed to study design, data processing, statistical/machine learning analyses, and manuscript revision. K.T. supervised the study and provided critical feedback. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This retrospective study used a de-identified clinical database from Chiba University Hospital. It was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine (approval number: 3380). The board waived the requirement for written informed consent, and all methods were conducted in accordance with the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects in Japan.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ikeda, Y., Sugimoto, S., Ishikawa, T. et al. Accurate prediction of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia using machine learning in critically ill patients. Sci Rep 16, 404 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29860-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29860-z