Abstract

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammatory condition requiring accurate and non-invasive imaging for diagnosis and monitoring. Current clinical methods, including Disease Activity Index (DAI) scoring, have limitations due to their subjectivity and inability to detect mild or early inflammation. This study introduces a novel 89Zr-labeled IL-23p19 monoclonal antibody ([89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19) for targeted immuno-PET imaging in a dextran sulfate sodium-induced murine IBD model. Radiolabeling of IL-23p19 antibody with [89Zr]Zr yielded a stable tracer with high radiochemical purity. PET/MR imaging showed focal accumulation of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 in inflamed colonic regions, aligning closely with histological inflammation and IL-23p19 expression. In contrast, the previous metabolic tracer [18F]FSPG demonstrated diffuse uptake without clear localization to inflamed tissues. Quantitative PET analysis indicated a significant correlation between [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 uptake and DAI scores, whereas [18F]FSPG exhibited weak correlations. These results highlight [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 immuno-PET imaging as a sensitive, specific, and non-invasive biomarker with strong potential for clinical translation in diagnosing and monitoring chronic intestinal inflammation in patients with IBD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, relapsing inflammatory disorder characterized by recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms and progressive functional impairment, resulting in substantial healthcare and societal burden1. Global epidemiological trends from 1990 to 2021 indicate stable incidence rates in Western countries, yet prevalence continues to rise owing to improved survival and the chronic nature of the disease2. Conversely, newly industrialized countries are experiencing a rapid increase in incidence rates, although the overall prevalence remains comparatively lower. In South Korea, both the incidence and prevalence of IBD have significantly risen over recent decades3,4.

The Disease Activity Index (DAI), a composite scoring system incorporating clinical parameters such as stool frequency, rectal bleeding, mucosal appearance, and physician’s global assessment, is the most commonly employed method for evaluating disease severity in clinical trials and routine clinical practice in IBD. Despite its practicality, the DAI is inherently subjective, susceptible to interobserver variability, and insufficiently sensitive to detect early or mild inflammatory states. These limitations may result in delayed diagnosis, inadequate intervention, and suboptimal monitoring of disease progression. Therefore, there is an urgent need for the development of objective, precise, and non-invasive diagnostic imaging methods to improve the clinical management of IBD.

Since the first introduction in 1997, [18F]F-fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) has become a standard imaging modality to detect inflammatory lesions based on enhanced glucose metabolism in activated immune cells5,6. Although PET imaging provides whole-body coverage and quantitative data that augment traditional clinical evaluations, the high physiological uptake of [18F]FDG in normal bowel tissue reduces its specificity for detecting inflammation7,8,9,10. In our previous research, we proposed (4S)-4-(3-[18F]Fluoropropyl)-L-glutamate ([18F]FSPG) as an alternative PET tracer, which demonstrated promising results in both preclinical and clinical studies by effectively identifying active inflammation and remission at the patient as well as bowel segment levels11,12. However, its clinical utility is constrained by the short physical half-life of fluorine-18 (~ 110 min), which may limit flexibility in imaging timing. In certain cases, extended imaging windows are beneficial to enhance lesion-to-background contrast or to capture delayed tracer uptake, especially in chronic inflammatory settings such as IBD.

Accurate and sustained detection of chronic IBD is essential to improve diagnostic precision, prevent complications, and guide individualized treatment. Recent advances in biologic therapies targeting the IL-23 pathway, including ustekinumab13, risankizumab14, and guselkumab15, and the recently FDA-approved mirikizumab16, have demonstrated the therapeutic relevance of this axis. These antibodies, which selectively inhibit IL-23p19 or IL-12/23p40, offer improved clinical outcomes due to their extended half-life and immunomodulatory effects17,18. The IL-23/Th17 pathway plays a central role in sustaining chronic intestinal inflammation, as IL-23 promotes Th17 cell survival and IL-17 production19,20,21. A recent study by Rezazadeh et al. introduced an 89Zr-labeled anti-IL12/23p40 antibody as an immuno-PET imaging probe for IBD22. However, 89Zr-labeled anti-IL12/23p40, which targets a shared subunit in the IL-12/IL-23 axis, showed limited clinical relevance, as its intestinal uptake plateaued or declined shortly after injection, reducing its suitability for delayed or longitudinal imaging. Moreover, its PET signal showed weak correlation with disease severity, limiting its diagnostic value. To overcome these limitations, we targeted IL-23p19, the unique and essential subunit of IL-23, which enables selective imaging of IL-23-driven inflammation. Unlike the shared p40 subunit, IL-23p19 provides greater molecular specificity and avoids cross-reactivity with IL-12 signaling. IL-23 is a key driver of Th17-mediated chronic mucosal inflammation and has emerged as a validated therapeutic target in IBD.8–10 This makes IL-23p19 an ideal candidate for biologically targeted molecular imaging in chronic intestinal inflammation.

Herein, we present a novel immuno-PET imaging strategy using 89Zr-labeled anti-IL-23p19 monoclonal antibody (G23-8) for non-invasive assessment of chronic intestinal inflammation in dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced murine IBD models (Fig. 1). The long half-life of 89Zr (3.3 days) enables prolonged imaging windows suitable for chronic disease monitoring. By targeting IL-23p19, a central mediator of the IL-23/Th17 inflammatory axis, this approach is designed to offer biologically specific detection of active disease. Importantly, literature-reported IL-23p19 monoclonal antibodies, such as risankizumab23 and guselkumab24, have demonstrated picomolar binding affinities (KD ≈ 21 pM and 35 pM, respectively, measured by surface plasmon resonance), supporting the feasibility of highly specific targeting of IL-23p19. The objective of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic potential and translational relevance of this targeted immuno-PET platform in a murine model of IBD.

Methods

Preparation of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 antibody

Synthesis of DFO-conjugated IL-23p19

The anti-mouse IL-23p19 monoclonal antibody (BioXcell, Lebanon, NH, USA) was first purified using a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and eluted with saline at a concentration of 3.3 mg/mL. The pH of the antibody solution was adjusted to 9.0 by the addition of sodium carbonate (Na2CO3; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA). The bifunctional chelator, 1-(4-isothiocyanatophenyl)-3-[6,17-dihydroxy-7,10,18,21-tetraoxo-27-(N-acetylhydroxylamino)-6,11,17,22-tetraazaheptaeicosine] thiourea (p-SCN-Bn-DFO; Macrocyclics, Plano, TX, USA), was dissolved in DMSO and added to the antibody at a 4.5-fold molar excess. The conjugation reaction was performed at 37 °C for 30 min with gentle shaking (550 rpm). The DFO-conjugated IL-23p19 antibody (DFO-IL-23p19) was purified using a PD-10 column and eluted with PBS buffer (pH 6.8), then stored at 4 °C until radiolabeling. The degree of p-SCN-Bn-DFO chelator conjugation to IL-23p19 was evaluated using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS; Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA, USA) and reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Arc HPLC system, Waters, USA) equipped with a PLRP column (PLRP-S, 1000 A 50 mm X 2.1 mm, Agilent, UK).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for antibody binding activity

To assess the binding activity of the antibody before and after DFO conjugation, a quantitative ELISA was performed. anti-mouse IL-23p19 monoclonal antibody was diluted to 5 µg/mL in antigen coating buffer (C3041, Sigma-Aldrich), and 20 µL of the solution was added to each well of a 96-well microplate (3690, Corning). Plates were incubated overnight at 4 °C for antigen immobilization. The following day, wells were blocked with 150 µL of 3% BSA in PBS and incubated at 37 °C for 1.5 h.

Serial dilutions of test antibodies (IL-23p19 and DFO-IL-23p19) were prepared in blocking solution, starting from 4,000 nM with a 1:4 dilution series to generate 10 concentrations (4,000, 1,000, 250, 62.5, 15.625, 3.90625, 0.9765625, 0.2441406, 0.0610352, 0.0152588, and 0 nM). 50 µL of each dilution were added to wells in triplicate. Plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 1.5 h. Between each step, wells were washed three times with 150 µL of wash buffer (524653, Merck Millipore).

Subsequently, 50 µL of goat anti-rat IgG (H + L), HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (A110-105P, Bethyl) diluted 1:10,000 in blocking solution, was added to each well. Plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C and then washed again. 50 µL of TMB substrate solution (00-4201-56, Invitrogen) were added, and the enzymatic reaction was stopped after 3 min by adding 50 µL of stop solution (DY994, R&D Systems). Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader to evaluate antibody binding activity.

Radiolabeling of DFO-IL-23p19 with [89Zr]Zr and quality control

No-carrier-added [89Zr]Zr-oxalate was purchased from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA, USA; manufactured by BV Cyclotron VU, Amsterdam, Netherlands) and used without further purification. A total of 185 MBq of [89Zr]Zr-oxalate diluted in 200 µL of 1 M oxalic acid was neutralized with 90 µL 2 M Na2CO3 in a 20 mL reaction vial and gently shaken at 500 rpm for 3 min. Subsequently, 1 mL of 0.5 M HEPES buffer (pH 7.0) and 710 µL of DFO-IL-23p19 solution were added, and the mixture was incubated for 60 min at 25 °C with gentle shaking (500 rpm).

Radiochemical purity and labeling efficiency were determined by radio-instant thin-layer chromatography (radio-TLC) using silica gel strips (iTLC-SG; Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The mobile phase was composed of 20 mM citric acid and acetonitrile (ACN) in a 9:1 (v/v) ratio. The resulting [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 was purified using a PD-10 desalting column and eluted with saline. The product was concentrated using a 100 kDa molecular weight cut-off centrifugal filter unit (Amicon® Ultra-0.5, Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) for subsequent in vivo studies.

Animal studies

Animal preparation and establishment of DSS-induced intestinal inflammation

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Asan Medical Center (registration number: 2024-30-094) and conducted in accordance with the ARRIVE 2.0 guidelines. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations for the ethical treatment, anesthesia, and euthanasia of animals. Male C57BL/6 mice (9 weeks old; average body weight, 26.4 ± 1.5 g) were purchased from JaBio (Suwon, Republic of Korea). During the experiments, mice were housed in groups of 4 per cage under controlled conditions (temperature, 22 ± 1 °C; humidity, 60 ± 5% to 50 ± 10%; 12:12 h light/dark cycle) with ad libitum access to food and water.

To induce intestinal inflammation, mice received 2.5% (w/v) dextran sulfate sodium (DSS; MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH, USA) dissolved in drinking water, which was ingested voluntarily for seven consecutive days. During the subsequent recovery period, mice were provided regular drinking water, while control mice received only regular drinking water throughout the entire experimental timeline.

Disease activity index (DAI) scoring

The severity of intestinal inflammation was assessed using the DAI, calculated based on the three parameters: weight loss, stool consistency, and the extent of rectal bleeding25. Each parameter was scored on a scale from 0 to 4 as follows (Table 1):

The final DAI score was determined by summing the individual scores and dividing the total by three, resulting in a composite score ranging from 0 (no disease) to 4 (severe disease). Scoring was conducted throughout the experimental period by two independent observers who each performed the scoring in a blinded manner.

PET/MR imaging

Radiotracer administration: [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 and [18F]FSPG

Mice were divided into three groups: control, [⁸⁹Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 imaging group, and [18F]FSPG imaging group (Fig. 2). PET/MR imaging with [⁸⁹Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 was performed on days 10 and 14 following DSS administration. Imaging with [18F]FSPG was also conducted on days 10 and 14. Radiotracers were administered via tail vein injection. [18F]FSPG was prepared as previously described12. A total of six mice were used per group (control, [⁸⁹Zr]Zr-IL-23p19, and [¹⁸F]FSPG) for imaging and downstream analyses.

PET/MR imaging

PET/MR imaging was performed on days 10 and 14 following DSS administration using a nanoScan PET/MR system (Mediso, Budapest, Hungary). Mice were anesthetized with 1.0–1.5% isoflurane throughout the imaging procedure to minimize motion artifacts. For [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19, static PET scans were acquired for 20 min after intravenous administration of approximately 7.4 MBq of radiotracer via the tail vein. For [18F]F-FSPG, static PET scans were performed for 10 min, starting at 60–70 min post injection, to capture optimal tracer biodistribution. Subsequently, T1-weighted MR images were obtained for anatomical reference.

PET images were reconstructed using a three-dimensional ordered-subsets expectation maximization (3D-OSEM) algorithm, with corrections applied for attenuation and scatter. Co-registration and fusion of PET and MR images were performed using the Mediso InterViewFUSION™ software. In addition, maximum intensity projection (MIP) PET images were generated to provide a comprehensive visualization of tracer distribution throughout the intestines. Regions of interest (ROIs) were manually defined on fused PET/MR images. To ensure consistency and minimize observer bias, spherical ROIs with a fixed diameter of 2 mm were placed over the regions of highest radiotracer uptake within the inflamed intestinal segments, as well as in background muscle tissue.

The standardized uptake value (SUV) was calculated according to the following formula:

Lesion-to-muscle ratios were also computed for semi-quantitative analysis. Correlations between PET imaging parameters and DAI scores were evaluated using linear regression analysis.

Ex vivo analysis

Mouse inflammation antibody array

Immediately following PET imaging, systemic inflammation was assessed by quantifying serum cytokine levels. Mice were anesthetized using 1.0–1.5% isoflurane administered via inhalation, and whole blood was collected from the inferior vena cava using a 26-gauge syringe. Blood samples were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to isolate serum. Cytokine profiling was performed using a mouse inflammation antibody array (RayBiotech, AAM-INF-1) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentrations of key proinflammatory cytokines, including interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-17 (IL-17), were quantified to evaluate systemic inflammatory responses.

Colon tissue assay

Euthanasia was performed under continued isoflurane anesthesia immediately after blood collection, in accordance with approved institutional ethical guidelines. Following euthanasia, the entire colon was excised, opened longitudinally, and rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm thickness, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) using standard histological protocols.

For IHC, paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and subjected to heat-induced antigen retrieval. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 0.7% hydrogen peroxide, followed by incubation in normal serum to reduce nonspecific binding. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with a primary antibody targeting IL-23p19 (Invitrogen, PA5-20239), followed by detection with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody using the EnVision™ detection system (Dako, K4050). Immunoreactivity was visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB), and nuclei were counterstained with Harris hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich). Stained slides were digitized using the Olympus Slideview VS200 system, and quantitative image analysis was performed using the HALO® image analysis platform (Indica Labs).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Differences between groups were analyzed using unpaired t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests where appropriate. *p ≤ 0.05 and **p ≤ 0.01. Correlation analyses were performed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size for animal experiments. Illustrations were created with BioRender.com.

Results and discussion

Radiolabeling and quality control of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19

Figure 3a illustrates the synthetic route for preparing [⁸⁹Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 antibody using the bifunctional chelator p-SCN-Bn-DFO. The isothiocyanate group of the chelator was covalently coupled to the primary amines of lysine residues on the antibody under mildly basic conditions (pH 8.9–9.1) at 37 °C for 60 min. MALDI-TOF MS analysis of the DFO-conjugated IL-23p19 revealed a mass shift of approximately 296.01 Da compared to the unconjugated antibody, corresponding to a DFO-to-antibody ratio of 0.393. HPLC analysis revealed a chelator-to-antibody conjugation ratio of approximately 0.43 (Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating that each IL-23p19 antibody molecule was conjugated with about 0.43 DFO chelators on average, consistent with the MALDI-TOF MS result (0.39). Although a 4.5-fold molar excess of p-SCN-Bn-DFO was used during the conjugation reaction, the actual incorporation efficiency was lower; nevertheless, the achieved conjugation was sufficient to enable stable and effective radiolabeling with [89Zr]Zr4+. The ELISA binding assay demonstrated comparable saturation binding between the unconjugated IL-23p19 antibody and its DFO-conjugated IL-23p19 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Although a slight reduction in binding efficiency was observed for DFO- IL-23p19 at lower concentrations, the maximal binding capacity remained nearly identical. These findings suggest that the target-binding potential of the antibody is largely preserved following DFO conjugation, supporting its suitability for in vivo applications.

Radiolabeling and quality control of the 89Zr-labeled antibody ([89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19). (a) Schematic illustration of the radiolabeling of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19. (b) Radiolabeling efficiency of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 at 10, 30, and 60 min reaction times. (c) Representative radio-TLC chromatogram of the purified [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19. (d) Synthetic scheme of [18F]FSPG, included to provide a complete overview of both radiotracers used in the study.

Following purification, the resulting DFO-IL-23p19 was radiolabeled with approximately 185 MBq of [89Zr]Zr-oxalate at room temperature (pH 6.8–6.9) to afford the [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19. This robust and reproducible radiolabeling strategy consistently yielded a stable tracer, which is essential to minimize non-specific background signal and ensure reliable biodistribution and PET quantification.

The reaction kinetics were systematically investigated to optimize the radiolabeling process. Aliquots of the reaction mixture were collected at predefined time points (10, 30, and 60 min) and analyzed by radio-TLC to determine labeling efficiency (Fig. 3b). The initial radiolabeling efficiency was approximately 16% at 10 min, increasing to over 80% after 60 min of reaction. Based on these findings, the optimal radiolabeling time was established as 60 min. After purification using a PD-10 desalting column, the purity of the final [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 product, determined by radio-TLC, was 100% (Fig. 3c). The high radiochemical purity confirmed the suitability of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 for in vivo PET/MR imaging applications.

Validation of intestinal inflammation of murine IBD models

The successful establishment of DSS-induced colitis was confirmed by clinical, histological, and molecular markers, including DAI scores, histopathological alterations, cytokine expression, and inflammatory profiling. During DSS treatment, all mice were carefully monitored for weight loss, stool consistency, and rectal bleeding. Importantly, none of the DSS-treated mice experienced a body weight loss greater than 20% of their baseline values, and all animals remained within the IACUC guidelines throughout the study. Despite this, DSS-treated mice exhibited progressive body weight loss compared to controls (p = 0.0019) and elevated DAI scores (3.1 ± 0.3), reflecting disease severity (Fig. 4a). Representative images of excised colons showed macroscopic features of inflammation, including shortening, thickening, and hyperemia in the DSS group (Fig. 4b). These abnormalities directly contributed to DAI scoring.

Successful establishment of DSS-induced colitis in murine IBD models. (a) Body weight changes following DSS treatment compared to control mice (n = 6 per group). (b) Macroscopic comparison of colons from control and DSS-induced colitis mouse models. (c) Representative H&E-stained colon sections showing histological features of control and DSS-treated groups. Scale bar: 100 μm. (d) Immunohistochemical staining for IL-23p19 expression in colonic tissues. Scale bar: 100 μm. (e) Quantification of IL-23p19 expression. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 6 per group). (f) Cytokine profile analysis comparing DSS-treated and control groups (n = 6 per group).

Histological evaluation revealed crypt distortion, epithelial erosion, and dense inflammatory infiltration in DSS-treated colons, in contrast to the preserved architecture in controls (Fig. 4c). Notably, IL-23p19 expression was markedly upregulated in epithelial and immune cells of inflamed tissue, as demonstrated by IHC and quantification (p = 0.019) (Fig. 4d and e). This target-specific expression supports the biological rationale for using [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 in molecular imaging.

Cytokine profiling revealed a pronounced pro-inflammatory environment in DSS-treated mice, with elevated levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, MCP-1, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-17 (Fig. 4f). This cytokine pattern closely reflects the dysregulated inflammatory network characteristic of human IBD, confirming that the model recapitulates key features of human intestinal inflammation and supporting the relevance of [⁸⁹Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 as a biologically meaningful PET imaging probe.

These findings demonstrate that DSS treatment successfully induces a complex inflammatory response characterized by clinical symptoms, mucosal injury, IL-23p19 upregulation, and cytokine dysregulation. The elevated expression of IL-23p19, a direct molecular target of our [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19, provides a rational basis for its application as a PET imaging probe. The model thus not only recapitulates key features of human IBD but also provides a biologically relevant platform for the evaluation of targeted molecular imaging strategies.

PET/MR imaging and quantitative analysis of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 and [18F]FSPG uptake in DSS-induced IBD models

The performance of [⁸⁹Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 as a molecular imaging probe for intestinal inflammation was evaluated by PET/MR imaging and compared with the conventional metabolic tracer [18F]FSPG. To evaluate disease progression, PET/MR imaging was performed at two time points, day 10 (intermediate disease) and day 14 (advanced disease) following DSS treatment. Notably, [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 was administered only once, prior to the day 10 imaging session, and the same cohort of mice was imaged again on day 14. This approach leveraged the long physical half-life (3.3 days) and prolonged circulation time of the radiolabeled antibody, which allowed for sequential imaging of disease evolution using a single injection. In contrast, [18F]FSPG, due to its short half-life (~ 110 min), required separate injections for each imaging time point. While this protocol aligns well with the rapid disease progression observed in murine models, we recognize that inflammation in human IBD unfolds over much longer timescales. Nevertheless, this design provides preclinical proof-of-concept for the potential application of long-lived immunoPET tracers in longitudinal imaging, which may reduce patient burden by enabling serial monitoring from a single tracer dose. Importantly, imaging data demonstrated that [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 provided superior diagnostic performance compared to [18F]FSPG at both stages of disease. The antibody tracer yielded more specific localization to inflamed colonic segments and exhibited greater correlation with clinical disease severity, emphasizing its utility for sensitive and dynamic monitoring of intestinal inflammation.

As shown in Fig. 5a, control mice exhibited only background-level uptake of both tracers, with no focal accumulation in the abdominal region, consistent with the absence of intestinal inflammation. In contrast, DSS-treated IBD mice injected with [⁸⁹Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 demonstrated intense and well-localized PET signals within the intestine, which co-registered precisely with the bowel wall on MR images. The uptake pattern displayed a characteristic focal distribution along inflamed colonic segments, consistent with histologically confirmed inflammation observed in vitro. The PET/MR fusion images further enabled precise anatomical localization of tracer accumulation, underscoring the utility of this antibody-based imaging approach for visualizing intestinal inflammation with high spatial resolution and target specificity.

PET/MR imaging and quantitative analysis of DSS-induced mouse models. (a) Representative axial and coronal PET/MR fusion images and corresponding T1-weighted MR images of control (left), [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19–injected (center), and [18F]FSPG–injected (right) mice. SUVmean of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 (b) and [18F]FSPG (c). Lesion-to-muscle uptake ratio of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 (d) and [18F]FSPG (e). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 6 per group).

In comparison, [18F]FSPG PET imaging in DSS-treated mice revealed moderate and heterogeneous abdominal uptake. Although tracer accumulation was higher than in control animals and localized to the general region of inflammation, the signal was diffuse and lacked the spatial specificity observed with [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19. These findings suggest that while [18F]FSPG is taken up at sites of inflammation, its ability to reflect the severity and extent of disease is limited. This interpretation is consistent with our previous report11,12 and highlights the superior performance of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 in both detecting and characterizing intestinal inflammation in vivo.

The enhanced imaging performance of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 is attributable to its specific binding to IL-23p19, which plays a key role in the IL-23/Th17 inflammatory axis. By directly binding to IL-23p19 expressed within inflamed intestinal tissues, the antibody provides a biologically specific and spatially resolved signal, resulting in robust lesion visualization. These findings highlight the potential of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 PET imaging as a valuable tool for non-invasive assessment of intestinal inflammation in IBD. Importantly, the ability of the antibody tracer to selectively detect inflamed regions with superior contrast compared to [18F]FSPG suggests it may offer improved diagnostic accuracy and more reliable disease monitoring.

Quantitative PET imaging analysis was performed to evaluate the uptake characteristics of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 compared to [18F]FSPG in DSS-induced IBD mice. The SUVmean analysis revealed that [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 antibody exhibited a progressive and significant increase in tracer accumulation within the inflamed intestine until 14 days after DSS treatment (Fig. 5b), which was consistent with the ongoing progression of inflammation. In contrast, [18F]FSPG displayed only modest and relatively stable SUVmean values across the same time points (Fig. 5c). These findings indicate that [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 provides a more dynamic and inflammation-sensitive imaging signal, likely due to its specific targeting of IL-23p19.

To further assess the lesion conspicuity and tracer specificity, lesion-to-muscle ratios were calculated. As shown in Fig. 5d, the intestinal lesion-to-muscle ratio of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 increased significantly over time, reflecting a continuous enhancement of inflammation. In contrast, the lesion-to-muscle ratio of [18F]FSPG remained low and unchanged throughout the study (Fig. 5e). These data suggest that while [18F]FSPG can detect metabolic alterations associated with colitis, its limited contrast and lack of dynamic uptake restrict its ability to sensitively monitor disease progression. In addition, MIP PET images were generated as supplementary video data to provide a dynamic and comprehensive visualization of tracer distribution (Supplementary Fig. 3). The treated group displayed pronounced abdominal uptake consistent with tracer accumulation in inflamed bowel segments, whereas the control group exhibited only background-level uptake. This difference is attributed to the upregulation of IL-23p19 and localized inflammation in the DSS model, in contrast to the absence of specific target expression in healthy controls.

These results demonstrate the superior diagnostic performance of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 PET imaging over conventional metabolic imaging with [18F]FSPG. The progressive increase in both SUVmean and intestinal lesion-to-muscle ratio provides compelling evidence that [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 offers a reliable, biologically specific, and non-invasive method for assessing intestinal inflammation and monitoring disease progression in preclinical IBD models.

Correlation between PET uptake and disease severity in DSS-induced IBD models

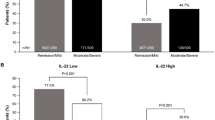

The relationship between PET imaging parameters and disease severity was further assessed by correlating lesion-to-muscle ratios with DAI scores for both tracers. [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 PET imaging demonstrated a strong positive correlation with clinical disease activity at both 10 and 14 days post-DSS treatment. At 10 days after DSS induction, the antibody uptake demonstrated a substantial correlation with DAI scores (R2 = 0.7302), indicating that inflammation-associated tracer accumulation could be detected even at intermediate stages of disease progression (Fig. 6a). Notably, the correlation further strengthened at 14 days after DSS induction (R2 = 0.9122), confirming that [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 uptake closely reflects the degree of inflammation as disease severity advances (Fig. 6b). These results highlight the ability of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 PET imaging to serve as a sensitive and quantitative biomarker for assessing intestinal inflammation in vivo.

Correlation analysis between PET imaging signals and DAI in DSS-induced models. (a, b) [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 uptake in the intestine showed a strong positive correlation with DAI scores on day 10 (R2 = 0.7302) and day 14 (R2 = 0.9122) post-DSS treatment. (c, d) [18F]FSPG uptake demonstrated no significant correlation with DAI scores on day 10 (R2 = 0.0106) or day 14 (R2 = 0.4595), indicating limited ability to reflect disease severity.

In contrast, [18F]FSPG PET imaging failed to demonstrate a meaningful correlation with DAI scores. At 10 days after DSS induction, there was virtually no correlation between tracer uptake and disease severity (R² = 0.0106) (Fig. 6c). Although a weak correlation was observed at 14 days after DSS induction (R² = 0.4595) (Fig. 6d), the association remained substantially lower than that observed with the [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19. These findings suggest that [18F]FSPG, despite its utility in reflecting metabolic alterations, lacks the specificity and dynamic range necessary for accurately monitoring colitis progression.

The superior correlation observed with [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 PET imaging likely results from its direct targeting of IL-23p19, a critical cytokine involved in the IL-23/Th17 axis and a well-known driver of intestinal inflammation. By selectively binding to this inflammation-associated biomarker, the antibody enables accurate detection and quantification of inflamed lesions, thereby outperforming the metabolic imaging capabilities of [18F]FSPG. Taken together, these data support the application of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 PET imaging as a highly promising, biologically specific tool for non-invasive assessment and monitoring of intestinal inflammation in preclinical IBD models.

In summary, this study demonstrates that [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 antibody enables sensitive and specific PET/MR imaging of intestinal inflammation in a preclinical DSS-induced IBD model. The radiolabeled antibody exhibited excellent radiochemical purity, favorable biodistribution, and superior lesion-to-background contrast compared to the conventional metabolic tracer [18F]FSPG. Quantitative imaging parameters, including SUVmean and lesion-to-muscle ratios, strongly correlated with disease activity, highlighting the potential of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 as a non-invasive biomarker for assessing inflammation severity and progression.

This targeted immuno-PET approach may offer a valuable tool not only for diagnosing and monitoring chronic intestinal inflammation but also for evaluating IL-23, targeted therapeutic strategies. Nonetheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, while the DSS-induced colitis model reflects many aspects of human IBD, it does not fully capture the immunological and pathological complexity of the clinical condition, which may affect translational applicability. Second, imaging was performed at fixed time points with a single antibody dose, limiting assessment of optimal imaging windows and dose-response dynamics. Third, the inherent long circulation time and slow clearance of antibody-based tracers, while suitable for preclinical imaging, may pose challenges for clinical use in time-sensitive diagnostic workflows.

Finally, although IL-23p19 is a critical mediator of IBD pathogenesis, additional inflammatory pathways likely contribute to disease heterogeneity and may warrant further exploration through multiplexed imaging approaches. We also acknowledge that ex vivo intestinal PET imaging would enhance the validation of ROI-derived in vivo PET data and help reduce variability in lesion analysis. While this was not performed in the current study, future work will incorporate ex vivo intestinal PET or organ-level biodistribution analysis to support and extend our in vivo findings. In addition, comprehensive ex vivo biodistribution studies will be essential for accurately quantifying tracer uptake in non-target tissues and for further confirming the specificity of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19.

Future studies should also explore the utility of this imaging platform for monitoring therapeutic response, assessing alternative antibody formats (e.g., fragments or nanobodies), and enabling extended time-point imaging to support clinical translation in IBD management.

Data availability

All data generated and/or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Seyed Tabib, N. S. et al. Big data in IBD: big progress for clinical practice. Gut 69, 1520. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320065 (2020).

Kaplan, G. G. & Windsor, J. W. The four epidemiological stages in the global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Reviews Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-020-00360-x (2021).

Park, S. H. et al. A 30-year trend analysis in the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Songpa-Kangdong district of Seoul, Korea in 1986–2015. J. Crohn’s Colitis. 13, 1410–1417. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz081 (2019).

Lee, J. W. & Eun, C. S. Inflammatory bowel disease in korea: epidemiology and pathophysiology. Korean J. Intern. Med. 37, 885. https://doi.org/10.3904/kjim.2022.138 (2022).

Brodersen, J. B. & Hess, S. FDG-PET/CT in inflammatory bowel disease: is there a future? PET. Clin. 15, 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpet.2019.11.006 (2020).

Noriega-Álvarez, E. & Martín-Comín, J. Molecular imaging in inflammatory bowel disease. Semin. Nucl. Med. 53, 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2022.12.003 (2023).

Aarntzen, E. H., Hermsen, R., Drenth, J. P., Boerman, O. C. & Oyen, W. J. 99mTc-CXCL8 SPECT to monitor disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Nucl. Med. 57, 398–403. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.115.165795 (2016).

Li, Y. & Behr, S. Acute findings on FDG PET/CT: key imaging features and how to differentiate them from malignancy. Curr. Radiol. Rep. 8, 22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40134-020-00367-x (2020).

Rezazadeh, F., Kilcline, A. P. & Viola, N. T. Imaging agents for PET of inflammatory bowel disease: A review. J. Nucl. Med. 64, 1858–1864. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.123.265935 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Comparative analysis of [18F]F-FAPI PET/CT, [18F]F-FDG PET/CT and magnetization transfer MR imaging to detect intestinal fibrosis in crohn’s disease: A prospective animal model and human cohort study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 51, 1856–1868. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-024-06644-7 (2024).

Chae, S. Y. et al. Exploratory clinical investigation of (4S)-4-(3-18F-Fluoropropyl)-L-Glutamate PET of inflammatory and infectious lesions. J. Nucl. Med. 57, 67–69. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.115.164020 (2016).

Seo, M. et al. PET imaging of system x(C) (-) in immune cells for assessment of disease activity in mice and patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Nucl. Med. 63, 1586–1591. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.121.263289 (2022).

Honap, S. et al. Effectiveness and safety of ustekinumab in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 67, 1018–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-021-06932-4 (2022).

D’Haens, G. et al. Risankizumab as induction therapy for crohn’s disease: results from the phase 3 ADVANCE and MOTIVATE induction trials. Lancet 399, 2015–2030. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00467-6 (2022).

Danese, S. et al. Efficacy and safety of 48 weeks of Guselkumab for patients with crohn’s disease: maintenance results from the phase 2, randomised, double-blind GALAXI-1 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9, 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(23)00318-7 (2024).

D’Haens, G. et al. Mirikizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 2444–2455. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2207940 (2023).

Herrington-Symes, A. P., Farys, M., Khalili, H. & Brocchini, S. Antibody fragments: prolonging circulation half-life special issue-antibody research. https://doi.org/10.4236/abb.2013.45090 (2013).

Chen, W., Sun, Z. & Lu, L. Targeted engineering of medicinal chemistry for cancer therapy: recent advances and perspectives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 5626–5643. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201914511 (2021).

Danese, S. & Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Evolution of IL-23 Blockade in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Crohn’s Colitis. 16, ii1–ii2. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab188 (2022).

Korta, A., Kula, J. & Gomułka, K. The role of IL-23 in the pathogenesis and therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24 (2023).

Krueger, J. G. et al. IL-23 past, present, and future: a roadmap to advancing IL-23 science and therapy. Front. Immunol. 15, 1331217. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1331217 (2024).

Rezazadeh, F. et al. Detection of IL12/23p40 via PET visualizes inflammatory bowel disease. J. Nucl. Med. 64, 1806. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.123.265649 (2023).

Krueger, J. G. et al. Anti–IL-23A mAb BI 655066 for treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: Safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and biomarker results of a single-rising-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 136, 116–124e117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.018 (2015).

Blauvelt, A. et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: results from the phase III, double-blinded, placebo- and active comparator–controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 76, 405–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.11.041 (2017).

Wirtz, S. et al. Chemically induced mouse models of acute and chronic intestinal inflammation. Nat. Protoc. 12, 1295–1309. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2017.044 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: RS-2018-KH049510). The mouse cartoons were created with BioRender.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.J.L. and D.Y.L. conceived and designed the study. N.K. and S.J.L. performed radiolabeling, quality control, and data analysis. J.W.A. and S.-Y.K. conducted animal experiments, immunohistochemistry, and cytokine profiling. J.H.C. contributed to PET/MR acquisition and image reconstruction. S.J.O. supervised the project and secured funding. N.K., S.-Y.K., and S.J.L. drafted the manuscript. H. Kim performed and analyzed the ELISA-based binding assay. Y.P. Kim carried out the quantification of chelators using MALDI-TOF MS and HPLC. All authors contributed to data interpretation, manuscript revision, and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ko, N., Ahn, J.W., Lee, D.Y. et al. A novel diagnosis strategy for chronic inflammatory bowel diseases using immuno-PET of [89Zr]Zr-IL-23p19 antibody. Sci Rep 16, 365 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29881-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29881-8