Abstract

Depression is a severe mental health disorder that profoundly affects individuals, characterized by persistent sadness, reduced enthusiasm, and impaired concentration, ultimately impacting daily life. Early and precise diagnosis is essential yet challenging, as traditional approaches rely heavily on subjective evaluations by mental health professionals, often resulting in delayed intervention. Recent advancements have explored the use of machine learning techniques to automatically estimate depression severity through speech analysis. Although prior methods have demonstrated effectiveness, there remains potential for further performance improvement. This paper introduces a novel deep spectrotemporal network designed to estimate depression severity scores from vocal cues. Specifically, we propose extracting holistic and localized spectral features using the pre-trained EfficientNet-B3 model from Mel spectrogram sequences and capturing spatiotemporal dynamics through our novel Volume Local Neighborhood Encoded Pattern (VLNEP) descriptor. Finally, a dual-stream transformer model is designed to effectively fuse and learn these extracted spectral and spatiotemporal features. Experimental results on the benchmark AVEC2013 and AVEC2014 datasets demonstrate the superiority of our proposed framework compared to state-of-the-art methods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depression, clinically referred to as major depressive disorder (MDD), is a psychiatric disease that is characterized by the inability to manage feelings for a prolonged time, long-term sadness, lack of pleasure or enthusiasm for life, and lack of concentration1. It significantly affects an individual’s behavior, work performance, and eating habits2. The individual with depression tends to have anxiety, hopelessness, worrying, irritability, or restlessness, and at worst, it could lead directly to suicide3. World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that nearly 350 million individuals throughout the world have MDD4. WHO now ranks depression at the number four cause of disability in the world, and the projection is that by the year 2030, it could be the second most prevalent cause4,5.

Fortunately, MDD can be treated with appropriate psychiatric care, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and medication. However, timely diagnosis significantly helps for successful intervention6. Depression at present is primarily diagnosed by skilled mental health professionals. However, this conventional approach is time-consuming, relies on subjective judgment, and does not offer real-time assessment. This often delays diagnosis, preventing patients from receiving timely and appropriate treatment. As a result, growing interest has emerged in using machine learning to automatically predict an individual’s level of depression, driving research in affective computing toward developing such diagnostic systems.

Physiological studies7,8 showed that individuals with depression exhibited different speech behavior, facial expressions, and body movements compared with individuals without the condition. In the literature, numerous video-based methods9,10,11 and audio-based methods1,12,13 have been proposed for automatic depression severity estimation. Among all such non-contact indicators, speech is the most accessible and natural means of interaction because vocal characteristics can reflect emotional states and meaning-carrying language13,14,15. In this study, we focus on using speech cues to predict the severity of depression. Specifically, our work aims to estimate scores from the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), which is an evaluation method of MDD stages. The BDI-II scores range from 0 to 63, with 0–13 indicating no depression, 14–19 representing mild depression, 20–28 reflecting moderate depression, and 29–63 signifying severe depression12,16.

Many researchers have proposed methods for estimating BDI-II scores by processing raw audio data1,16, extracting hand-crafted low-level features17,18, or employing deep learning techniques12,13,19,20 to analyze the Fourier spectra of speech signals for depression indicators. While these approaches have demonstrated their effectiveness, there remain certain areas for further enhancement. For instance, previous studies have not adequately addressed the integration of local and global representations derived from spectrograms, which is crucial because local features capture detailed, fine-grained frequency information, whereas global features encapsulate broader contextual patterns21. Additionally, dynamic texture descriptors, which effectively capture subtle temporal variations inherent in speech signals, have been underexplored for modeling spectrogram sequences. Moreover, the joint modeling of spectral and temporal features has not been sufficiently investigated; such modeling could facilitate more robust feature learning by effectively capturing complementary information across these domains, indicating significant potential for improvement in this area.

In this paper, we introduce a deep spectrotemporal network for automated depression severity estimation from speech cues. First, we partition the audio data into fixed-length segments and derive Mel spectrograms from these segments. These Mel spectrogram sequences are then fed into the spectral stream and the temporal stream. The spectral stream captures holistic spectral features from the full Mel spectrogram and local spectral features from multiple spectrogram patches using the pre-trained EfficientNet-B3 model22. Meanwhile, in the temporal stream, we propose a novel dynamic texture descriptor, namely the Volume Local Neighborhood Encoded Pattern (VLNEP), to extract spatiotemporal dynamics from Mel spectrogram sequences. Finally, features from both streams are jointly learned through a dual-stream transformer model, enabling robust fusion of spectral and temporal information for accurate BDI-II score prediction. We conducted comprehensive experiments on two benchmark datasets, including, AVEC2013 dataset17 and AVEC2014 dataset18. The findings confirm that the proposed framework outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods in depression severity prediction. Our key contributions are outlined as follows:

-

We capture the holistic and local spectral features from the Mel spectrogram via state-of-the-art EfficientNet-B3 and aggregate them, improving performance further.

-

We develop a dynamic feature descriptor, named Volume Local Neighborhood Encoded Pattern (VLNEP), which captures spatiotemporal patterns from Mel spectrogram sequences by encoding local neighborhood dynamics.

-

We design a dual-stream transformer framework that facilitates effective fusion and joint representation learning of spectral and temporal features.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section “Related works” provides a review of related work on automated depression assessment using audio-based approaches. Section “Proposed framework” describes the proposed framework in detail. Section “Experiments and result analysis” presents the experimental evaluation conducted on two benchmark datasets, including an ablation study and a comparison with existing state-of-the-art methods. Lastly, Section “Conclusion” concludes the paper.

Related works

Numerous strategies have been developed for automated assessment of depression severity, including biomarker-based methods23, analyses of social media content24, EEG-based techniques25, video-based approaches9,10,11, audio-based methods12,13,19,20, and multimodal fusion frameworks16,26. In this section, we specifically focus on audio-based methods for automated depression assessment.

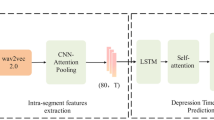

Valstar et al.17 initiated the foundation by establishing the AVEC2013 challenge, setting benchmarks for predicting depression severity from audio data. Meng et al.27 utilized the Motion History Histogram (MHH) method to extract dynamic vocal features, subsequently employing Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to predict depression levels effectively from audio signals. Continuing the trend, Valstar et al.18 presented the AVEC2014 challenge, refining the scope by emphasizing structured vocal feature extraction and regression-based prediction methods to enhance performance. Jain et al.28 employed Fisher Vector encoding on audio descriptors, coupled with linear Support Vector Regression (SVR), significantly outperforming earlier baseline approaches. Jan et al.29 further advanced audio-based depression detection by extracting Spectral Low-Level Descriptors (LLDs) and Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs), utilizing these features in regression models to achieve superior predictive performance. He et al.19 introduced a hybrid approach combining hand-crafted features, namely Median Robust Extended Local Binary Patterns and deep-learned features extracted through convolutional neural networks (CNNs), achieving improved results in automatic depression analysis from speech signals. Niu et al.30 developed a hybrid neural network framework combining CNN, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), and Deep Neural Networks (DNN) for segment-level MFCC feature extraction and proposed optimized p-norm pooling combined with LASSO regression for aggregating these features to estimate depression severity more accurately. Subsequently, Cummins et al.31 presented a two-stage rank regression framework that partitioned audio features into distinct score ranges. Zhao et al.32 proposed a hybrid network integrating Self-Attention Networks (SAN)33,34 and Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (DCNN) to capture complementary depression-relevant features from acoustic descriptors and 3D log-Mel spectrograms, respectively. Further innovation was demonstrated by Niu et al.35, who developed a Spatio-Temporal Attention (STA) network employing spatial and temporal attention mechanisms to highlight discriminative audio frames and effectively capture detailed temporal variations. Dong et al.36 introduced a hierarchical depression detection model leveraging deep speaker recognition (SR) and speech emotion recognition (SER) features extracted from pretrained models, significantly improving audio-based depression severity estimation. Fu et al.20 proposed an integrated model combining Audio Delta Ternary Patterns (ADTP) for temporal movement features with high-level spectral and MFCC features, enhancing the ability to predict depression scores through deep network architectures. Uddin et al.16 introduced a deep Spatio-Temporal Networks framework, employing a 1D residual network and an LSTM-based encoder-decoder architecture with attention mechanisms to capture both local spatial features and temporal dynamics effectively from audio data. Subsequently, Niu et al.12 presented WavDepressionNet, which modeled raw speech signals to capture comprehensive depression-related information and employed representation blocks and a spatiotemporal self-calibration mechanism to enhance prediction performance. Liu37 developed a Multi-Head Self-Attention Network (WavMHSA-Net), which utilized WavLM38 for direct feature extraction from raw speech signals and employed multi-head self-attention mechanisms to emphasize depression-relevant features, leading to enhanced depression severity estimation. Zhao et al.39 designed the Dense Coordinate Channel Attention Network (DCCANet), which extracted profound speech features using Coordinate Channel Attention (CCA) blocks and dense connections, providing superior capability in distinguishing depression levels from audio data. Huang et al.1 further leveraged wav2vec 2.0, a pre-training model, to automatically derive high-quality vocal features from raw audio, demonstrating excellent generalization capabilities and notable performance in depression severity classification tasks. Exploring time-frequency characteristics, Niu et al.13 analyzed the Fourier spectrum of speech signals, introducing a Time-Frequency Self-Embedding (TFSE) module and a Time-Frequency Tensor Vectorization (TFTV) module to refine feature extraction and significantly boost prediction accuracy. Subsequently, Niu et al.26 presented a Depression Scale Dictionary Decomposition (DSDD) framework, employing semantically derived dictionaries from depression scales to enhance the identification of depression cues in audio sequences. Recently, Wang et al.40 proposed a spatiotemporal information modeling and modality alignment (SIMMA) framework, where audio data was processed through a linear spatiotemporal detector and cross-modal temporal aligner. However, existing methods inadequately addressed the integration of local and global spectrogram features as well as overlooked dynamic texture descriptors for capturing temporal characteristics.

Proposed framework

This paper introduces a deep spectrotemporal network designed to estimate depression severity by predicting BDI-II scores using vocal cues. The approach begins by dividing the input audio into fixed-length segments, from which Mel spectrograms are produced. These spectrograms are processed through two different streams: a spectral stream that captures both holistic and local spectral features, and a temporal stream that extracts dynamic texture patterns. The features obtained from both these streams are then jointly learned using a dual-stream transformer model. An overview of the proposed framework for automatic depression level prediction is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Data preprocessing

During the data preprocessing phase, the original audio signals are resampled to an 8 kHz frequency, following the procedure adopted in prior studies13,16,30,35. Similar to32, we divide the raw speech signal into short segments (set S = 30 chosen empirically) using 25 ms Hamming frames with a 10ms hop. For each frame, we compute the power spectrum and pass it through the i-th Mel filter to obtain the band energy \(u_i\). A logarithmic operation is then applied to \(u_i\) to produce the log-Mel coefficient \(x_i\). Lastly, we compute the \(x_i^{d}\) feature, which is the deltas of \(x_i\) via Eq. (1), while the value of N is set to 3. Similarly, the delta-deltas features \(x_i^{dd}\) are computed by taking the derivative of the deltas, as presented in Eq. (2).

Afterward we produce a three-dimensional feature representation \(Z \in \mathbb {R}^{t \times f \times c}\), where t denotes the length of the frame, f denotes the number of Mel-filter banks and c is the channel count. In our setup, f is set to 80, and c is 3, corresponding to the static, deltas and delta-deltas log-Mel spectrograms, respectively. This 3D log-Mel spectrogram is used as input to the spectral stream, whereas the temporal stream uses the 2D static log-Mel spectrogram as input. In this work, Mel spectrograms are chosen due to their demonstrated effectiveness in capturing subtle frequency variations in speech, which are essential for accurate emotion and depression analysis19,20.

Spectral stream

The spectral stream is responsible for capturing both holistic and localized spectral features from 3D log-Mel spectrogram using the pre-trained EfficientNet-B3 model22. EfficientNet-B3, part of the EfficientNet family, leverages a compound scaling method that simultaneously balances network depth, width, and resolution. EfficientNet-B3 adopts a systematic design with an initial layer for convolution, followed by a series of stages made up of Mobile Inverted Bottleneck Convolution (MBConv) blocks. Specifically, the architecture starts with a 3\(\times\)3 convolutional layer for capturing essential low-level features. Then it contains a total of 12 MBConv blocks formed into separate stages, and the number of stages follows a systematic scaling of depth (layer number), width (channels per layer), and resolution (input size). Each MBConv block consists of expansion, depthwise convolution, squeeze and excitation (SE), and projection stages. The SE mechanism rescales the channel-wise feature responses explicitly modeling inter-channel relationships, and hence improving the network’s representation capability. The network concludes with a convolutional layer, followed by global average pooling (GAP) and a fully connected classification layer. We empirically found that EfficientNet-B3 performs better than other pre-trained state-of-the-art models such as VGGNet41, ResNet42, and Inception-ResNet-v243 (see Table 2). EfficientNet-B3 achieves the best performance with maintained computational effectiveness due to the efficient scaling of the network parameters. Its depth and width dimensions are systematically balanced, and hence it could generalize better and extract robust features. Furthermore, the resulting lightweight computation facilitated within the MBConv blocks built into the EfficientNet architecture provides a clear stride for the model’s appropriateness for real-time and resource-limited applications without losing performance.

In this work, we extract two types of spectral information from each 3D log-Mel spectrogram: holistic features and local features from multiple patches. For holistic feature extraction, a single pre-trained EfficientNet-B3 model is applied to capture global spectral information from the entire 3D log-Mel spectrogram, which corresponds to an individual audio segment. The holistic feature extraction process extracts deep feature representations from the final GAP layer, resulting in a compact \(1 \times 1536\) dimensional feature vector per spectrogram. In contrast, for local feature extraction, each 3D log-Mel spectrogram is partitioned into four overlapping patches. These patches are individually passed through the EfficientNet-B3 model to extract local feature representations. Similar to the holistic feature extraction process, features are extracted from the GAP layer, yielding a \(4 \times 1536\) dimensional feature vector per spectrogram. Afterward, mean-pooling is applied to these four local feature vectors to produce a \(1 \times 1536\) dimensional local feature vector. Finally, the holistic and local features are concatenated, resulting in a unified \(1 \times 3072\) dimensional feature vector per 3D log-Mel spectrogram.

Temporal stream

Dynamic texture descriptors such as Volume Local Binary Pattern (VLBP)44, Adaptive Local Motion Descriptor (ALMD)45, Volume Local Directional Number (VLDN)9, and Volume Local Directional Structural Pattern (VLDSP)16 have been widely used for capturing facial temporal dynamics. However, their use in extracting temporal dynamics from spectrogram sequences has been largely overlooked. This work investigates the application of dynamic texture descriptors for temporal feature extraction. Existing descriptors like VLBP and ALMD capture only the sign of intensity differences between the center pixel and its neighbors, which limits their robustness to noise and reduces their ability to represent fine-grained texture structures. On the other hand, VLDN and VLDSP encode only the most prominent directional responses using the first and second derivatives, discarding weaker gradients and thus diminishing discriminative power in complex or low-contrast regions. In order to overcome the aforementioned issues, this work proposes a dynamic texture descriptor called Volume Local Neighborhood Encoded Pattern (VLNEP) to capture temporal dynamics from 2D static log-Mel spectrogram sequences.

For the time frame t, the input to the VLNEP is three consecutive frames (i.e., the \((t-1)^{\text {th}}\) (previous), \(t^{\text {th}}\) (current), and \((t+1)^{\text {th}}\) (next) frames). For the previous frame, \(LNEP\_PF\) in Eq. (3) compares the intensity of each pixel \(I_i\) in the previous frame relative to two neighboring pixels positioned either vertically or horizontally in the current frame, as well as with the center pixel in the current frame \(J_C\) using the sign function. The sign function emphasizes that it encodes ordinal relations and therefore provides robustness to monotonic intensity transforms. Specifically, the neighboring pixels in the current frame for a pixel at location i are denoted as \(J_{(i+1) \bmod P}\) and \(J_{(P+i-1) \bmod P}\), where P is the total number of pixels in the neighborhood of the current frame J. \(\odot\) denotes the XOR operation; therefore, after the three comparisons, if all three intensity signs match, the pixel at location i is assigned a value of 1; otherwise, it is assigned 0. Similarly, for the current frame, \(LNEP\_CF\) in Eq. (4) compares the intensity of each pixel \(J_i\) relative to two neighboring pixels positioned either vertically or horizontally in the current frame, as well as with the center pixel in the current frame \(J_C\). Finally, for the next frame, \(LNEP\_NF\) in Eq. (5) compares the intensity of each pixel \(K_i\) in the next frame relative to two neighboring pixels positioned either vertically or horizontally in the current frame, as well as with the center pixel in the current frame \(J_C\). Afterward, the binary output for each of the previous, current, and next frames is transformed into a decimal number by summing the products of the weights assigned to each position. The max-pooling operation is then performed on the resulting decimal values of the three consecutive frames, which generates the VLNEP code (see Eq. 6). This max-pooling operation selects the strongest of the three temporal responses, providing robustness to small temporal jitter and ensuring that salient local dynamics are retained even if they peak in only one of the three frames. Finally, a statistical histogram represents the VLNEP feature vector with size \(1 \times 256\). More specifically, we compute the VLNEP-based spatiotemporal features by applying the following equations.

An illustration of VLNEP is presented in Fig. 2. The proposed VLNEP captures richer temporal and structural variations by encoding neighborhood relationships along with comparisons between the center and neighboring pixels across consecutive frames, thereby enhancing robustness to noise and preserving fine-grained dynamic patterns.

Dual-stream transformer model

In the literature, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks were utilized to model the spatiotemporal dynamics present in spectrogram sequences20,30. Although effective in capturing sequential dependencies, these methods exhibit limitations in modeling long-range temporal dependencies. Transformers first appeared prominently in Natural Language Processing (NLP) tasks46,47 and subsequently gained prominence in computer vision tasks48,49,50,51, excelling particularly in capturing extensive contextual interactions through self-attention mechanisms. Recently, Transformer-based models have been adapted for emotion recognition52 and speech-based depression severity prediction1,13; however, the use of Transformers to extract spatiotemporal representations from Mel spectrogram sequences has not been explored sufficiently. To address this gap, our study proposes a dual-stream Transformer framework designed to learn spatiotemporal features from spectral and temporal characteristics of Mel spectrogram sequences, thereby enhancing the prediction performance of depression severity.

The proposed dual-stream Transformer architecture comprises five primary components: embedding layer, positional encoding, Transformer encoder, aggregation layer, and prediction layer. Initially, a one-dimensional convolution-based embedding layer with \(d_{model}\) filters processes input features independently from both spectral and temporal streams. Specifically, given input feature sequences \(F \in \mathbb {R}^{S \times b}\)–where S denotes the number of audio segments and b indicates feature dimensionality–the embedding \(F_{embed}\) is calculated as:

To effectively integrate temporal relationships essential for sequential modeling, sinusoidal positional encodings are incorporated into the embeddings for both streams. These encodings are defined as:

Here, pos refers to the feature’s sequence position, d is the dimension index, and \(b_{model}\) represents the embedding vector dimension. Incorporating positional encodings preserves sequential order, thus resolving the permutation invariance limitation inherent in conventional Transformer models.

The Transformer encoder consists of several stacked layers, each comprising a multi-head self-attention sub-layer followed by a position-wise feed-forward neural network. The multi-head self-attention computes attention scores between all pairs of positions, effectively capturing global context within the entire sequence. This mechanism is mathematically described as:

where queries Q, keys K, and values V are linear projections derived from the embedded input, and \(b_k\) denotes the dimensionality of keys. The multi-head outputs are concatenated and further linearly projected. Empirically, our study employs three encoder layers. Each encoder layer includes a position-wise feed-forward network composed of two fully connected layers with nonlinear activations, coupled with residual connections and layer normalization to ensure stable training.

Following the Transformer encoder, features from each stream are passed to the aggregation layer. Here, we adopt an attention mechanism to emphasize relevant information while diminishing less significant details. This mechanism operates on encoder outputs, represented as hidden states \({ z_k }_{k=0}^{L-1}\), with sequence length L. Each hidden state \(z_k\) undergoes a nonlinear transformation using a learnable weight matrix \(W_a\) and bias \(b_a\), followed by a \(\tanh\) activation:

Attention scores for each hidden state are calculated using another learnable weight matrix \(W_b\) and bias \(b_b\), normalized via the softmax function:

Subsequently, the context vector G for each stream is derived as a weighted sum of hidden states, guided by the computed attention scores:

In our dual-stream Transformer, context vectors from the spectral stream (\(G_X\)) and temporal stream (\(G_Y\)) are concatenated to produce the final feature vector:

This concatenated vector V serves as the input to the prediction layer, which estimates BDI-II scores. The prediction layer comprises a fully connected layer having 128 neurons followed by a regression layer. To mitigate potential overfitting during training, a dropout layer with a dropout rate of 0.2 is incorporated before the fully connected layer.

Experiments and result analysis

This section presents experimental evaluations conducted on two publicly available benchmark datasets, namely AVEC 201317 and AVEC 201418, to validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach. We begin by providing an overview of these benchmark datasets along with the experimental setup used for our model. Subsequently, ablation studies are carried out to assess the contribution of each proposed component in predicting depression severity. Lastly, a comparative analysis is performed against existing state-of-the-art methods. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations as well as all experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee at Heriot-Watt University.

Dataset

The AVEC2013 depression dataset17 comprises 150 audio recordings collected from 82 individuals. It is derived from the larger Audio-Visual Depressive Language Corpus (AViD-Corpus), which includes 340 recordings from 292 participants. In this corpus, participants were recorded one to four times, with 5 appearing in 4 sessions, 93 in 3, 66 in 2, and 128 in a single session, spaced approximately two weeks apart. The audio durations range from 20 to 50 minutes, during which participants engaged in various Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) tasks such as counting numbers, sustained vowel pronunciation, and verbalizing thoughts while performing a task. Each recording contains speech from a single participant captured via a microphone. The age range of participants is 18 to 63 years, with an average age of 31.5 years. All speakers are native German speakers. Each subject signed an informed consent form before the experiment. The dataset is divided evenly into training, development, and test sets, with 50 recordings in each partition, and every audio is labeled with a corresponding BDI-II score.

The AVEC2014 depression dataset18 consists of 300 audio recordings from 84 participants, also extracted from the AViD-Corpus. It features two distinct types of tasks: the Freeform task, where participants respond to emotionally evocative questions such as recalling a sad memory, and the Northwind task, where participants read a passage from a fable aloud. Each task contributes 150 recordings, and participant overlap includes 18 individuals with 3 recordings, 31 with 2, and 34 with just one. All speakers are German natives, and the recordings were made using a microphone. Each subject signed an informed consent form before the experiment. Similar to the AVEC2013 dataset, AVEC2014 is divided into training, development, and test subsets, each containing 100 recordings. Each audio clip is labeled with its corresponding BDI-II score, and the average duration of these recordings is approximately 2 minutes. In both datasets, the training set is utilized to develop the proposed model, the development set is used for evaluating individual module effectiveness, and the test set serves to benchmark performance against state-of-the-art approaches. Fig. 3 illustrates the distribution of BDI-II scores across both datasets.

Experimental settings

The experimental configuration was executed using Jupyter Notebook (Python 3.7) and MATLAB 2024a on a 64-bit Windows 10 system equipped with 16GB RAM and an Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-10750H processor. The model training was carried out using the Adam optimizer, with a batch size of 32, a momentum value of 0.9, and a learning rate set to 0.0001. The Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) was used as the loss function during training. To evaluate the overall effectiveness of the proposed framework, both Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) are used as performance metrics, which are defined as

where \(x_i\) indicates the actual BDI-II score for the \(i\)-th instance, \(\bar{x}_i\) corresponds to the model’s predicted score, and \(N\) refers to the total number of instances.

Ablation study

To evaluate the contributions of various components in our proposed framework, we conduct a comprehensive ablation study using the AVEC2013 and AVEC2014 datasets. Table 1 presents the prediction performance, in terms of MAE and RMSE, for different architectural variants. First, we assess the spectral stream using holistic features with a Transformer, which yields competitive results and reflects the value of global spectral context. However, replacing holistic features with only multi-patch local features slightly degrades performance, indicating that localized features alone may lack global context and can over-respond to transient artifacts. Fusing holistic and local spectral features recovers both strengths of global context and local detail, therefore mitigating the smoothing of discriminative micro-patterns by holistic features and the context-insensitivity of local patches; accordingly, the integrated spectral stream achieves improved results on both datasets. Furthermore, incorporating the VLNEP-based temporal stream with a Transformer enhances performance even further, highlighting the importance of capturing dynamic temporal patterns. Finally, the proposed spectrotemporal network, which jointly learns and fuses both spectral and temporal representations, achieves the best performance across both datasets, confirming the complementary nature of spectral and temporal features for depression severity estimation from speech.

The results presented in Table 2 compare the performance of different pre-trained convolutional neural network (CNN) architectures utilized as backbone modules for spectral feature extraction in our proposed framework, evaluated on both the AVEC2013 and AVEC2014 datasets. Among the four models tested, VGGNet-1641, ResNet-10142, Inception-ResNet-v243, and EfficientNet-B3, the EfficientNet-B3 based spectral stream consistently achieves the lowest Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) across both datasets. Specifically, on AVEC2013, it achieves an MAE of 6.91 and RMSE of 8.08, while on AVEC2014, it records an MAE of 6.41 and RMSE of 7.95. This consistent improvement demonstrates that EfficientNet-B3, with its compound scaling strategy and enhanced feature extraction capabilities, is more effective in capturing the relevant spectral cues correlated with depression severity compared to other conventional architectures. These findings validate the choice of EfficientNet-B3 as the spectral stream backbone in our dual-stream transformer network.

Table 3 presents a comparative analysis of various dynamic texture descriptors integrated into the temporal stream of the proposed framework, evaluated on the AVEC2013 and AVEC2014 datasets. Among the descriptors compared, the proposed VLNEP descriptor achieves the best performance across both datasets. Specifically, VLNEP achieves the lowest MAE and RMSE values of 6.57 and 7.76 on AVEC2013, and 6.21 and 7.62 on AVEC2014, respectively. This demonstrates VLNEP’s superior ability by capturing ordinal relations across consecutive frames and applying max-pooling, it remains robust to monotonic intensity shifts while retaining weak but informative temporal patterns. In contrast, MHH compresses temporal history, and VLDN or VLDSP emphasizes only dominant derivatives, thereby losing these subtle cues.

Figure 4 illustrates the performance comparison of the proposed transformer architecture against different variants on the AVEC2013 and AVEC2014 datasets. From this experiment, it is evident that the proposed transformer consistently outperforms all other variants in both datasets across both evaluation metrics. Specifically, the removal of positional encoding leads to the highest MAE and RMSE, highlighting the significance of temporal order modeling in speech-based depression estimation. Similarly, excluding the 1D convolutional layer adversely impacts performance, which suggests that this component is crucial for capturing local contextual patterns in the spectrogram features. On the other hand, omitting the global attention mechanism degrades the model’s ability to capture global dependencies, reflected by an increase in both MAE and RMSE. Among all the variants, the full model that integrates positional encoding, 1D convolution, and global attention yields the lowest error rates. This confirms the combined effectiveness of all three components in enhancing the transformer’s ability to model complex spectrotemporal dynamics effectively.

Figure 5 illustrates the performance trends of the proposed dual stream transformer model when varying the number of encoder layers (\(N = 1\) to \(N = 5\)) in the AVEC2013 and AVEC2014 datasets. As depicted, the model achieves its best performance at \(N = 3\) encoder layers for both datasets, reflected by the lowest MAE and RMSE values. Increasing the number of encoder layers from 1 to 3 enhances the model’s capacity to capture complex spectrotemporal patterns, leading to improved depression severity estimation. However, further increasing the number of layers beyond 3 results in a gradual performance drop. This is because additional capacity beyond 3 layers yields diminishing returns on these datasets and begins to memorize speaker or channel abnormalities and noise.

Figure 6 presents the impact of varying audio segment lengths (\(S = 10, 20, 30, 40, 50\)) on the depression severity prediction performance, evaluated using MAE and RMSE on the AVEC2013 and AVEC2014 datasets. The results clearly indicate that segment size plays a crucial role in the model’s performance. For both datasets, a segment length of \(S = 30\) achieves the lowest error values in terms of both MAE and RMSE, demonstrating its effectiveness in balancing temporal detail and sequence-level context. When the segment size is either too small (\(S = 10\)) or too large (\(S = 50\)), the model performance deteriorates. Short segments may fail to capture sufficient contextual information, whereas excessively long segments might include redundant or noisy patterns, negatively affecting the model’s learning capability.

Figure 7 presents a visual comparison between the predicted BDI-II scores generated by the proposed framework and the actual ground truth scores across the test subjects from the AVEC2013 and AVEC2014 datasets. As shown in both subplots, the predictions closely follow the general trend of the actual scores, particularly at the lower and higher ends of the depression spectrum. However, some noticeable deviations are observed in the mid-range scores. This inconsistency can be attributed to the uneven distribution of BDI-II labels within both datasets.

We additionally computed the training and validation losses of the proposed framework, as illustrated in Figs. 8 and 9. The resulting curves demonstrate that the model maintains a consistent performance across both sets without signs of overfitting, thereby confirming its robustness and strong generalization ability. The proposed framework contains approximately 15.1 million trainable parameters and requires 4.8 giga floating point operations (GFLOPs).

Comparison with state-of-the-art approaches

Table 4 presents the performance comparison between our proposed Deep Spectrotemporal Network and existing state-of-the-art methods for depression severity estimation on the AVEC2013 and AVEC2014 datasets. The results highlight that our method consistently outperforms previous approaches in terms of both Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). Traditional hand-crafted methods, such as MHH+PLS27, Fisher Vector28, and PCA+PLS29, achieved higher error rates, indicating limited capability in capturing complex depression cues due to reliance on manually selected features.

In comparison, deep learning-based models such as Deep CNN19, CNN+LSTM+DNN30, and Hybrid Network32 demonstrated improved performance due to automatic high-level feature extraction. The STA Network35, SR+SER36, and recent methods like STN16 and WavDepressionNet12 further advanced performance by employing sophisticated temporal and spatial attention mechanisms. However, these methods still exhibit relatively higher MAE and RMSE compared to our proposed framework.

The SpectrumFormer13 and DSDD26 represent the latest advancements, leveraging detailed spectral attributes for better depression estimation. Yet, our proposed Spectrotemporal Network achieves superior performance with the lowest MAE (5.860 on AVEC2013, 5.78 on AVEC2014) and RMSE (7.109 on AVEC2013, 6.918 on AVEC2014), underscoring the effectiveness of jointly learning holistic, multi-patch local spectral features via EfficientNet-B3 and temporal dynamics using our novel VLNEP descriptor. This substantial performance gain emphasizes our method’s capability to comprehensively capture depression-related cues from speech, outperforming state-of-the-art methods.

Conclusion

This study presented a deep spectrotemporal network leveraging vocal cues for automated depression severity assessment. Our approach innovatively combines the EfficientNet-B3 model’s robust spectral feature extraction with the novel VLNEP descriptor’s effective temporal dynamic encoding. Employing a dual-stream transformer allowed for the effective fusion and learning of comprehensive spatiotemporal representations from Mel spectrogram sequences. Empirical evaluations on the AVEC2013 and AVEC2014 datasets confirmed that our method significantly outperforms existing techniques, underscoring the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed model. However, our evaluation was restricted to the AVEC2013 and AVEC2014 datasets, which comprise recordings of native German speakers and specific elicitation protocols; consequently, cultural and linguistic factors may limit external validity. As future work, we will assess cross-corpus generalization through multilingual datasets, domain adaptation, and robustness testing under varied speaking styles.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are from [https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2512530.2512533] and [https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2661806.2661807]. These datasets are publicly available upon request. To access the datasets, please contact Professor Michel Valstar at the University of Nottingham.

Code availability

The source code for all the experiments can be viewed at https://github.com/azher0006/DepressionPrediction.

References

Huang, X. et al. Depression recognition using voice-based pre-training model. Sci. Rep. 14, 12734 (2024).

Belmaker, R. H. & Agam, G. Major depressive disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 55–68 (2008).

Soloff, P. H., Lis, J. A., Kelly, T., Cornelius, J. & Ulrich, R. Self-mutilation and suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. J. Pers. Disord. 8, 257–267 (1994).

World Health Organization. Depression. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression (2021).

Depression, W. Other Common mental disorders: global health estimates. World Health Organization24 (2017).

for Mental Health (UK), N. C. C. et al. Depression: the treatment and management of depression in adults (updated edition) (British Psychological Society, 2010).

Mundt, J. C., Vogel, A. P., Feltner, D. E. & Lenderking, W. R. Vocal acoustic biomarkers of depression severity and treatment response. Biol. Psychiat. 72, 580–587 (2012).

Dietrich, M., Abbott, K. V., Gartner-Schmidt, J. & Rosen, C. A. The frequency of perceived stress, anxiety, and depression in patients with common pathologies affecting voice. J. Voice 22, 472–488 (2008).

Uddin, M. A., Joolee, J. B. & Lee, Y.-K. Depression level prediction using deep spatiotemporal features and multilayer bi-ltsm. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 13, 864–870 (2020).

Al Jazaery, M. & Guo, G. Video-based depression level analysis by encoding deep spatiotemporal features. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 12, 262–268 (2018).

Zhou, X., Jin, K., Shang, Y. & Guo, G. Visually interpretable representation learning for depression recognition from facial images. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 11, 542–552 (2018).

Niu, M., Tao, J., Li, Y., Qin, Y. & Li, Y. Wavdepressionnet: Automatic depression level prediction via raw speech signals. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 15, 285–296 (2023).

Niu, M., Tao, J., He, Y., Zhang, S. & Li, M. Examining the fourier spectrum of speech signal from a time-frequency perspective for automatic depression level prediction. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2025, 256 (2025).

Stasak, B., Epps, J., Cummins, N. & Goecke, R. An investigation of emotional speech in depression classification. In Interspeech 485–489 (2016).

Long, H. et al. Detecting depression in speech: Comparison and combination between different speech types. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), 1052–1058 (IEEE, 2017).

Uddin, M. A., Joolee, J. B. & Sohn, K.-A. Deep multi-modal network based automated depression severity estimation. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 14, 2153–2167 (2022).

Valstar, M. et al. Avec 2013: the continuous audio/visual emotion and depression recognition challenge. In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM International Workshop on Audio/visual Emotion Challenge 3–10 (2013).

Valstar, M. et al. Avec 2014: 3d dimensional affect and depression recognition challenge. In Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge 3–10 (2014).

He, L. & Cao, C. Automated depression analysis using convolutional neural networks from speech. J. Biomed. Inform. 83, 103–111 (2018).

Fu, X., Li, J., Liu, H., Zhang, M. & Xin, G. Audio signal-based depression level prediction combining temporal and spectral features. In 2022 26th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR) 359–365 (IEEE, 2022).

Ma, R. et al. Learning attention in the frequency domain for flexible real photograph denoising. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 33, 3707–3721 (2024).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. Efficientnet: rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In International Conference on Machine Learning 6105–6114 (PMLR, 2019).

Wollenhaupt-Aguiar, B. et al. Differential biomarker signatures in unipolar and bipolar depression: a machine learning approach. Austral. New Zeal. J. Psychiatry 54, 393–401 (2020).

Zhou, L. et al. Tamfn: Time-aware attention multimodal fusion network for depression detection. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 31, 669–679 (2022).

Wang, B. et al. Depression signal correlation identification from different eeg channels based on cnn feature extraction. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 328, 111582 (2023).

Niu, M. et al. Depression scale dictionary decomposition framework for multimodal automatic depression level prediction. IEEE Trans. Circ. Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 256 (2025).

Meng, H. et al. Depression recognition based on dynamic facial and vocal expression features using partial least square regression. In Proceedings of the 3rd ACM international workshop on Audio/visual emotion challenge 21–30 (2013).

Jain, V., Crowley, J. L., Dey, A. K. & Lux, A. Depression estimation using audiovisual features and fisher vector encoding. In Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Audio/visual Emotion Challenge 87–91 (2014).

Jan, A., Meng, H., Gaus, Y. F. B. A. & Zhang, F. Artificial intelligent system for automatic depression level analysis through visual and vocal expressions. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 10, 668–680 (2017).

Niu, M., Tao, J., Liu, B. & Fan, C. Automatic depression level detection via lp-norm pooling 4559–4563 (Proc. INTERSPEECH, Graz, Austria, 2019).

Cummins, N. et al. Generalized two-stage rank regression framework for depression score prediction from speech. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 11, 272–283 (2017).

Zhao, Z. et al. Hybrid network feature extraction for depression assessment from speech (Proc. INTERSPEECH, Shanghai, China, 2020).

Ma, R., Li, S., Zhang, B., Fang, L. & Li, Z. Flexible and generalized real photograph denoising exploiting dual meta attention. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 53, 6395–6407 (2022).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 30, 256 (2017).

Niu, M., Tao, J., Liu, B., Huang, J. & Lian, Z. Multimodal spatiotemporal representation for automatic depression level detection. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 14, 294–307 (2020).

Dong, Y. & Yang, X. A hierarchical depression detection model based on vocal and emotional cues. Neurocomputing 441, 279–290 (2021).

Liu, S. Multi-head self-attention network for depression level estimation from speech. In 2024 9th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Signal Processing (ICSP) 1088–1091 (IEEE, 2024).

Chen, S. et al. Wavlm: large-scale self-supervised pre-training for full stack speech processing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 16, 1505–1518 (2022).

Zhao, Z., Liu, S., Niu, M., Wang, H. & Schuller, B. W. Dense coordinate channel attention network for depression level estimation from speech. In International Conference on Pattern Recognition 402–413 (Springer, 2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Simma: multimodal automatic depression detection via spatiotemporal ensemble and cross-modal alignment. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2025, 256 (2025).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556 (2014).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 770–778 (2016).

Szegedy, C., Ioffe, S., Vanhoucke, V. & Alemi, A. Inception-v4, inception-resnet and the impact of residual connections on learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 31 (2017).

Zhao, G. & Pietikainen, M. Dynamic texture recognition using local binary patterns with an application to facial expressions. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 29, 915–928 (2007).

Uddin, M. A., Joolee, J. B., Alam, A. & Lee, Y.-K. Human action recognition using adaptive local motion descriptor in spark. IEEE Access 5, 21157–21167 (2017).

Gillioz, A., Casas, J., Mugellini, E. & Abou Khaled, O. Overview of the transformer-based models for nlp tasks. In 2020 15th Conference on computer science and information systems (FedCSIS) 179–183 (IEEE, 2020).

Wang, R. et al. Raft: robust adversarial fusion transformer for multimodal sentiment analysis. Array 2025, 100445 (2025).

Han, K. et al. A survey on vision transformer. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 87–110 (2022).

Gao, M. et al. Towards trustworthy image super-resolution via symmetrical and recursive artificial neural network. Image Vis. Comput. 158, 105519 (2025).

Wang, R. et al. Contrastive-based removal of negative information in multimodal emotion analysis. Cogn. Comput. 17, 107 (2025).

Wang, R. et al. Cime: contextual interaction-based multimodal emotion analysis with enhanced semantic information. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2025, 256 (2025).

Zhu, X. et al. Rmer-dt: robust multimodal emotion recognition in conversational contexts based on diffusion and transformers. Inf. Fusion 2025, 103268 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Chungbuk National University Glocal30 project (2025).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Chungbuk National University Glocal30 project (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ishana Jabbar and Joolekha Bibi Joolee conducted the experiments. Md Azher Uddin developed the idea. Ishana Jabbar, Joolekha Bibi Joolee, and Md Azher Uddin analyzed the results. Ishana Jabbar, Joolekha Bibi Joolee, Aziz Nasridinov, and Md Azher Uddin wrote and reviewed the manuscript. Md Azher Uddin and Aziz Nasridinov are the corresponding authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jabbar, I., Uddin, M.A., Joolee, J.B. et al. Deep spectrotemporal network based depression severity estimation from speech. Sci Rep 15, 45620 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29889-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29889-0