Abstract

This cross-sectional study evaluated the association between sleep health and the Lifestyle Inflammation Score (LIS), which has not been sufficiently examined in previous research. We further assessed whether inadequate sleep duration and poor sleep quality are associated with a higher LIS. Moreover, we explored the effects of age, sex, and income. A generalized ordered logit model was used to evaluate the association between sleep health and the LIS, incorporating independent variables and control variables. Separate models predicted the LIS quintile probability for each combination of sleep quality and sleep duration. Inadequate sleep duration (odds ratio [OR]: 1.108, P < 0.001) and poor sleep quality (OR: 1.090, P < 0.001) were significantly associated with higher LIS across quintiles. The probability of belonging to the highest LIS quintile (Q5) did not increase proportionally with age. Crucially, predictive margins analysis showed that poor sleep health was associated with a higher predicted probability of being in the highest LIS quintile (20.7%) compared with good sleep health (18.4%). This large-scale nationwide study identified consistent associations between poor sleep health and higher inflammation burden within the study population, highlighting the need for comprehensive management strategies addressing sleep alongside other lifestyle factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sleep is essential for maintaining immune regulation, metabolic balance, and cognitive function. Insufficient and excessive sleep have been linked to cardiometabolic and mental health disorders, including obesity, diabetes, and depression1,2,3.

The National Sleep Foundation recommends 7–9 h of sleep for adults aged 18–64 years and 7–8 h for those aged ≥ 65 years, noting that durations outside these ranges are associated with cardiovascular and metabolic diseases4. Sleep durations < 6 or > 10 h for adults aged 18–64 years, and < 5 or > 9 h for those aged ≥ 65 years, reportedly increase health risks5,6,7. This is because insufficient sleep can disrupt circadian rhythms, cause hormonal imbalance, and weaken immune function. However, prolonged sleep duration may reflect reduced physical activity and underlying health conditions or sleep disorders, suggesting that excessive sleep is more likely a consequence or marker of ill health rather than a direct cause.

Sleep quality is equally important for overall health. Even when sleep duration is adequate, poor quality can impair physical and mental recovery, increase fatigue, and elevate inflammatory activity8,9. Mechanistically, reduced sleep quality activates the sympathetic nervous system and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, increasing stress hormones, such as cortisol and inflammatory markers including C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-62,4,10,11.

Chronic inflammation is a key mechanism in the onset and progression of various chronic diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases2,12. Moreover, emerging evidence has suggested that chronic low-grade inflammation is also involved in mental health conditions, such as depression and anxiety, emphasizing its broad systemic relevance13. However, measuring inflammation levels in daily life requires blood tests (e.g., CRP and white blood cell count), and there is a lack of comprehensive indicators to evaluate the overall impact of lifestyle factors on inflammation.

To address these issues, the Lifestyle Inflammation Score (LIS) was proposed14. The LIS integrates key factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and body mass index (BMI) into a single score, with higher values reflecting lifestyle patterns with greater potential to induce inflammation14,15. Recent studies have shown that the LIS is significantly associated with risks of cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and cancer16, suggesting its potential for use in screening high-risk groups and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions15,17.

However, to our knowledge, previous studies have not examined sleep health, including duration and quality, in relation to a comprehensive LIS rather than individual inflammatory biomarkers10,11,18. Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation of sleep health and its association with the LIS is necessary.

Given the cross-sectional nature of the dataset, the objectives of the present study were to (1) assess whether sleep duration (adequate vs. inadequate) and sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI]) are associated with the LIS, (2) determine whether there is an interactive effect on LIS elevation when both factors are poor, and (3) evaluate whether the effects of key variables, particularly age, are consistent across LIS quintiles, thereby identifying potential non-linear distribution patterns. The conceptual framework of the study is illustrated in Fig. 1. Through this, we aimed to highlight the need for an inflammation management strategy that comprehensively considers lifestyle factors, such as sleep, weight, smoking, and physical activity, while also exploring lifestyle management policies and digital health-based intervention strategies applicable across healthcare systems.

Results

General characteristics of the study participants

Of the 231,602 participants, 46,427 (20.04%), 46,906 (20.24%), 50,339 (21.72%), 43,128 (18.61%), and 44,924 (19.39%) were in the first (Q1), second (Q2), third (Q3), fourth (Q4), and fifth (Q5) LIS quintiles, respectively. Regarding sleep health, slightly more participants reported adequate than inadequate sleep duration (50.63%, n = 117,253 vs. 49.37%, n = 114,349), while noticeably more participants reported good than poor sleep quality (71.98%, n = 166,791 vs. 28.02%, n = 64,937). Over half of the participants were female (54.20%, n = 125,590), and the largest age group was aged 45–64 years (37.40%), followed by those aged 19–44 years (26.44%), with smaller proportions of participants in the older than younger age groups. Higher income households (≥ 3 million won/month) comprised the majority (59.79%), while only 12.68% were in the lowest income bracket (< 1 million won/month). Regarding medical accessibility, most participants reported no unmet medical need (95.33%, n = 220,884), whereas the remaining few did (4.67%). Regarding mental health indicators, a minority reported experiencing stress (20.27%, n = 46,969) and depression (6.90%, n = 15,980). Chronic diseases were reported, with 32.14% (n = 74,462) having hypertension and 14.14% (n = 32,761) having diabetes (Table 1).

LIS quintiles according to sleep health and general characteristics

Chi-square tests showed that LIS quintiles were significantly associated with all general characteristics and sleep health variables (P < 0.001). The proportion of participants with inadequate sleep duration increased from 44.62% in Q1 to 52.04% in Q5, indicating that inadequate sleep duration was more prevalent among individuals with higher inflammatory burden than among those with lower inflammatory burden. The proportion of participants with poor sleep quality gradually increased from 24.63% in Q1 to 29.18% in Q3 and then to 30.39% in Q5.

Sex distribution showed an increasing proportion of male individuals as the LIS quintile increased but a decreasing trend for female individuals (70.01% to 41.41%). In Q5, the 45–64-year age group had the highest proportion (38.99%), whereas the ≥ 75-year age group had the lowest proportion (17.74%). The proportion of participants in the high-income group (≥ 3 million won /month) decreased, from 69.97% in Q1 to 56.50% in Q5. However, the proportion of those in the low-income group (< 1 million won/month) increased, from 8.16% in Q1 to 14.31% Q5, suggesting that economic vulnerability is associated with higher inflammatory burdens. Unmet medical need increased slightly, from 4.54% in Q1 to 4.99% in Q5.

The rates of presence of mental health indicators and chronic diseases increased from Q1 to Q5: 19.78% to 22.75% for stress, 6.07% to 7.57% for depression, 15.72% to 46.34% for hypertension, and 7.00% to 20.56% for diabetes (Table 2).

Association between the LIS quintiles and sleep health

Generalized ordinal logistic regression analysis showed that sleep health and other demographic, social, and health factors were significantly associated with the LIS quintiles (P < 0.001). Multicollinearity was not a concern, as variance inflation factor (VIF) values for independent variables were below the conventional threshold of 10 (mean VIF: 1.19). Inadequate sleep duration (odds ratio [OR]: 1.108, P < 0.001) and poor sleep quality (OR: 1.090, P < 0.001) were significantly associated with an increased odds of being in the higher LIS quintiles, with inconsistent effects across categories.

Sex and income level showed significant inverse relationships with the LIS: female individuals had lower odds than male individuals did (OR: 0.437, P < 0.001), and higher income was associated with a reduced odds of being in the higher LIS quintiles (OR: 0.772 for income group 3 [≥3 million won/month] vs. reference, P < 0.001).

Age showed a highly complex association with the LIS across quintiles. The ≥ 75-year group showed increased odds of having a higher LIS in Q1; however, this effect was attenuated or reversed in the higher quintiles. The association became non-significant (P = 0.807) in the LIS ≤ Q3 vs. > Q3 comparison and negative (OR= 0.894, P < 0.001) in the LIS ≤ Q4 vs. > Q4 comparison.

Chronic diseases, stress, and depression were significant risk factors for having a higher LIS. Specifically, hypertension (OR: 2.034, P < 0.001) and diabetes (OR: 1.386, P < 0.001) were significantly associated with a higher LIS. Stress and depression were significantly associated with a higher LIS across the categories (Table 3).

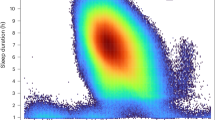

Predicted probability analysis by the LIS quintile for the PSQI and sleep duration combinations

Predictive margins analysis revealed a clear shift in the probability of belonging to a specific LIS quintile based on sleep health combinations (Table 4). For the group with good sleep quality and adequate sleep duration, the predicted probability of being in the lowest LIS quintile (Q1) was 21.1% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 20.9–21.4%), whereas the probability of being in the highest quintile (Q5) was only 18.4% (95% CI: 18.2–18.6%). In contrast, for the group with poor sleep quality and inadequate sleep duration, the probability of being in Q1 was the lowest, at 18.3% (95% CI: 18.0–18.7%). This probability distribution shifted dramatically, with the probability of being in Q5 increasing to 20.7% (95% CI: 20.3–21.0%) (Table 4).

Non-linear pattern of age on the LIS in the predictive margins analysis

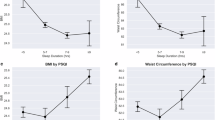

Age and sleep duration were determinants of the LIS, with a combined effect that was more complex than their individual associations. Inadequate sleep consistently decreased the predicted probability of being in the lowest LIS quintile (Q1) and increased the probability of being in the highest quintile (Q5) across all age groups. For instance, in the 19–44-year group, the probabilities of being in Q1 were 26.3% for individuals with adequate sleep but only 24.5% for those with inadequate sleep. However, the analysis demonstrated a significant non-linear pattern of age. Regardless of sleep duration, the predicted probability of being in Q1 decreased as age increased (from 26.3% in the 19–44-year group to 15.0% in the ≥ 75-year group among those with adequate sleep). Crucially, the probability of being in the highest LIS quintile (Q5) did not increase proportionally with age; it even decreased in the ≥ 75-year group (from 18.7% in the 19–44-year group to 17.2% in the ≥ 75-year group among those with adequate sleep), a finding that illustrates the non-parallel pattern of age on the LIS (Fig. 2).

Discussion

We comprehensively evaluated the relationship between sleep health (sleep duration adequacy and sleep quality) and the LIS using nationwide large-scale data. The results showed that inadequate sleep duration and poor sleep quality were significantly associated with a higher LIS (upper quintiles). The OR for inadequate sleep duration ranged from 1.065 to 1.108, and that for poor sleep quality ranged from 1.090 to 1.143, both of which were consistently significant. Notably, an interactive pattern emerged when both indicators were combined: the predicted probability for Q5 (top quintile) was 20.7% in the “Poor Quality & Inadequate Duration” combination, compared with 18.4% in the “Good Quality & Adequate Duration” combination. This indicates that impaired sleep health is strongly associated with higher lifestyle-based inflammatory burden8,11,18.

These findings align with prior research indicating that sleep disruption is linked to health risks through chronic low-grade inflammatory mechanisms, such as sympathetic nervous system hyperactivity, HPA axis activation, and increased inflammatory cytokines. Previous studies have suggested that sleep duration and quality act as independent risk factors while being intertwined in a complementary manner with inflammation-related lifestyle patterns, potentially showing an associated shift toward the upper quantiles of the LIS2,4,19. In this study, sex-specific differences were also noted. Women showed lower proportions in the highest LIS quintile compared with men, likely reflecting their generally lower rates of smoking, alcohol consumption, and obesity11,14,16. Furthermore, the consistent association of hypertension and diabetes with an increased LIS reaffirmed that chronic diseases and lifestyle-related inflammatory burdens exhibit a mutually reinforcing relationship20,21.

Among socioeconomic and mental health factors, low income and unmet medical need were associated with a higher LIS, with stress and depressive experiences showing significant associations. This demonstrates that inflammatory burden can accumulate structurally, intertwine with healthcare accessibility and mental health, and extend beyond individual lifestyle dimensions22.

The probability of being in Q1 decreased steadily with age, whereas the probability for Q2 increased noticeably across age groups. However, a non-linear age pattern was observed in the association between sleep health and the LIS. The predicted probability of belonging to the highest LIS quintile (Q5) increased from young to middle-aged adults but decreased in the oldest group (≥ 75 years). This descriptive curvilinear pattern suggests that the relationship between age and lifestyle-related inflammation is not simply monotonic. Possible explanations, such as survivor bias, behavioral adaptation, or physiological attenuation of inflammatory responses in older adults, warrant further investigation23,24,25. Additionally, as shown in Table 4, this non-linear distribution pattern, in which the predicted probability for Q3 slightly exceeded that of Q5 among those with poor sleep quality and inadequate duration, may reflect a threshold effect, where the inflammatory impact plateaus beyond multiple adverse lifestyle factors26.

To effectively alleviate the burden of chronic inflammation, integrated lifestyle management programs encompassing weight management, smoking cessation, reduced alcohol consumption, and physical activity should be established to target simultaneous improvements in sleep quality and duration. Furthermore, health disparities among vulnerable populations should be reduced and health equity strengthened at the population level by expanding digital, mobile, and customized service models that combine mental health support strategies with improved access to medical care22.

This study has some limitations. First, its cross-sectional design precludes establishing causality and cannot rule out reverse causation or residual confounding. Although causality cannot be inferred from this cross-sectional study, sleep interventions targeting unrecognized sleep disorders, such as insomnia or obstructive sleep apnea, may help reduce the overall burden of lifestyle-related inflammation. Future longitudinal or interventional research is warranted to confirm temporal relationships and clarify causal pathways underlying these associations. Second, sleep, lifestyle habits, and disease indicators were self-reported, which may have introduced recall bias. Future studies using objective measures such as actigraphy are warranted. Third, the lack of complex sample weighting may lead to underestimation of standard errors and limit representativeness and generalizability. Fourth, the results reflect Korean BMI standards and cultural specificities (such as sleep and alcohol consumption habits)27,28, potentially limiting their international generalizability.

In conclusion, this large-scale nationwide study showed that poor sleep health is consistently associated with a higher inflammation burden, highlighting the need for comprehensive management strategies addressing sleep alongside other lifestyle factors.

Methods

Data sources

This study was conducted using raw data from the 2024 Community Health Survey (CHS) conducted by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. The CHS is an annual survey with a multistage sampling design that has been conducted by local health centers nationwide since 2008. The survey includes data from 153 questions related to residents’ health behaviors, morbidity, and environment through one-on-one interviews (computer-assisted). The 2024 survey targeted adults aged ≥ 19 years nationwide between May 16 and July 3129.

Of 231,728 respondents, 231,602 were included in the final analysis after excluding 126 cases (0.05%) with missing data on the LIS quintile, stress, depression, diabetes, or hypertension using listwise deletion. Given the minimal missingness, bias was unlikely. Although the CHS used a complex sampling design, weights were not applied because this study focused on associations rather than population-level estimates. The large sample size (> 230,000) was sufficient to detect statistical relationships.

The 2024 Community Health Survey (CHS) was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. All participants provided informed consent before data collection. The present study protocol was approved by the Yonsei University Mirae Institutional Review Board (IRB no. 1041849-202508-SB-164-01), which waived the requirement for additional informed consent because only de-identified secondary data were used. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant guidelines and regulations.

Variables

Dependent variable

The dependent variable was the LIS14, an indicator that integrates lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and BMI) using weighted values. Higher scores reflect lifestyle patterns with greater potential to induce inflammation. Based on previous studies, continuous LIS values were sorted in ascending order and divided into five quintiles, ranging from the first quintile (Q1, lowest) to the fifth quintile (Q5, highest)14 (Table 5).

The LIS is calculated with the following formula:

Independent variables

Independent variables included sleep quality and sleep duration. Sleep quality was assessed using the PSQI, which generates a total score ranging from 0 to 21 points based on 7 components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime functioning, based on sleep habits over the past month. Participants with a PSQI total score ≤ 5 points were classified as the “Good” group, whereas those with a score ≥ 6 points were classified as the “Poor” group for analysis30. The PSQI cutoff of > 5 has been validated in Korean adults, showing acceptable sensitivity and specificity for identifying poor sleepers31.

The PSQI is calculated with the following formula:

Appropriate sleep duration was classified based on the recommendations of the National Sleep Foundation (2015)5. This was defined as 7–9 h for adults aged < 65 years and 7–8 h for those aged ≥ 65 years. Deviations from this range were considered inappropriate. For analysis, participants were categorized into two groups: adequate and inadequate5.

Control variables

Control variables included demographic factors (sex and age), economic factors (monthly income), presence of chronic diseases (diabetes and hypertension), mental health factors (experience of stress and depression), and medical accessibility (unmet medical need).

Age was reclassified into four categories based on the CHS questionnaire: 19–44 years, 45–64 years, 65–74 years, and ≥ 75 years. Stress experience was defined as responding “I feel a lot of stress” or “I feel a great deal of stress” to the question, “How much stress do you typically feel in your daily life?” Monetary values were expressed in units of 100, where 100 corresponds to 1 million KRW.

Analysis methods

General characteristics of the participants were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages. Differences between the LIS quintiles and sleep health groups were assessed using chi-square tests.

The primary analysis of the association between sleep health (sleep quality and adequate sleep duration) and the LIS was conducted using a generalized ordered logit model (gologit2). This model was chosen after the Brant test indicated a significant violation of the proportional odds assumption (P < 0.001) in a preliminary ordinal logistic regression model. The gologit2 model addressed this issue by allowing the effects of independent variables to vary across cumulative logits. All models were adjusted for covariates, including sex, age, income level, medical need, stress, depressive experience, and presence of chronic diseases (hypertension and diabetes). VIF values were calculated to assess potential multicollinearity, and all values were below the conventional threshold of 10 (mean VIF: 1.19), indicating no multicollinearity concerns.

Additionally, to predict absolute probabilities, a separate generalized ordered logit model with an interaction term between sleep quality and sleep duration was used. Based on this model, the absolute probabilities of the five LIS quintiles were predicted for each combination of sleep quality and sleep duration using the margins command in Stata. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata MP 18 (64-bit), and the significance level was set at P < 0.05.

Data availability

The raw data from the 2024 Korea Community Health Survey (KCHS) are not publicly available due to participant privacy regulations but can be requested from the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA). Researchers interested in accessing the data should apply through the official KCHS website (https://chs.kdca.go.kr/), where contact information and the formal application process are provided. For direct inquiries, the KDCA Statistics Division can be contacted at 043-719-7396 or via fax at 043-719-7429.

References

Medic, G., Wille, M. & Hemels, M. E. Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nat. Sci. Sleep. 9, 151–161 (2017).

Irwin, M. R. Why sleep is important for health: a psychoneuroimmunology perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66, 143–172 (2015).

Irwin, M. R. & Opp, M. R. Sleep health: reciprocal regulation of sleep and innate immunity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 42, 129–155 (2017).

Hirshkowitz, M. et al. National sleep foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep. Health. 1, 40–43 (2015).

Ungvari, Z. et al. Imbalanced sleep increases mortality risk by 14–34%: a meta-analysis. GeroScience. 47 (3), 4545–4566 (2025).

Itani, O., Jike, M., Watanabe, N. & Kaneita, Y. Short sleep duration and health outcomes: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Sleep. Med. 32, 246–256 (2017).

García-Perdomo, H. A., Zapata-Copete, J. & Rojas-Cerón, C. A. Sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol. Psychiatric Sci. 28 (5), 578–588 (2019).

Buysse, D. J. Sleep health: can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep. 37, 9–17 (2014).

Altena, E., et al. How sleep affects daytime functioning: the latest insights from different patient and age groups. Brain Sci. 11 (9), 1163. (2021).

Besedovsky, L. et al. Sleep and immune function. Pflugers Arch. 463, 121–137 (2012).

Irwin, M. R., Olmstead, R. & Carroll, J. E. Sleep disturbance, sleep duration, and inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies and experimental sleep deprivation. Biol. Psychiatry. 80, 40–52 (2016).

Grandner, M. A. Sleep, health, and society. Sleep. Med. Clin. 17, 117–139 (2022).

Milaneschi, Y. et al. Association of inflammation with depression and anxiety: evidence for symptom-specificity and potential causality from UK biobank and NESDA cohorts. Mol. Psychiatry. 26, 7393–7402 (2021).

Byrd, D. A. et al. Development and validation of novel dietary and lifestyle inflammation scores. J. Nutr. 149, 2206–2218 (2019).

Shivappa, N., Steck, S. E., Hurley, T. G., Hussey, J. R. & Hébert, J. R. Designing and developing a literature-derived, population-based dietary inflammatory index. Public. Health Nutr. 17, 1689–1696 (2014).

Li, Z. et al. Novel dietary and lifestyle inflammation scores directly associated with all-cause, all-cancer, and all-cardiovascular disease mortality risks among women. J. Nutr. 151, 930–939 (2021).

Wirth, M. D. et al. Association of a dietary inflammatory index with inflammatory indices and metabolic syndrome among Police officers. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 56, 986–989 (2014).

Patel, S. R. et al. Sleep duration and biomarkers of inflammation. Sleep. 32, 200–204 (2009).

Slavich, G. M. & Irwin, M. R. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: a social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychol. Bull. 140, 774–815 (2014).

Kwaifa, I. K., Bahari, H., Yong, Y. K. & Noor, S. M. Endothelial dysfunction in obesity-induced inflammation: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Biomolecules. 10, 291 (2020).

Pickup, J. C. Inflammation and activated innate immunity in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 27, 813–823 (2004).

Gulliford, M. et al. What does ‘access to health care’ mean? J. Health Serv. Res. Policy. 7, 186–188 (2002).

Franceschi, C. et al. Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech. Ageing Dev. 128, 92–105 (2007).

Shen, X. et al. Nonlinear dynamics of multi-omics profiles during human aging. Nat. Aging. 4, 1619–1634 (2024).

McKechnie, D. G. et al. Associations between inflammation, cardiovascular biomarkers and incident frailty: the British regional heart study. Age Ageing. 50, 1979–1987 (2021).

Guo, K. et al. Lifestyle deterioration linked to elevated inflammatory cytokines over a two-month follow-up. Sci. Rep. 14, 21381 (2024).

Lee, Y. H. et al. Impact of visceral obesity on the risk of incident metabolic syndrome in metabolically healthy normal weight and overweight groups: a longitudinal cohort study in Korea. Korean J. Fam Med. 41, 229–236 (2020).

Cho, S. S., Min, J., Ko, H. & Kang, M. Y. Data profile: Korean Work, Sleep, and health study (KWSHS). Ann. Occup. Environ. Med. 37, e3 (2025).

Kang, Y. W. et al. Korea community health survey data profiles. Osong Public. Health Res. Perspect. 6, 211–217 (2015).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28, 193–213 (1989).

Shin, S. & Kim, S. H. The reliability and validity testing of the Korean version of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index. J. Converg Inf. Technol. 10, 148–155 (2020).

Wu, D., Zhai, Q. & Shi, X. Alcohol-induced oxidative stress and cell responses. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21, S26–S29 (2006).

Mathews, M. J., Liebenberg, L. & Mathews, E. H. The mechanism by which moderate alcohol consumption influences coronary heart disease. Nutr. J. 14, 33 (2015).

Forde, C. Scoring the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) 3 (Univ. of Dublin, 2018).

Gomez-Cabrera, M. C., Domenech, E. & Viña, J. Moderate exercise is an antioxidant: upregulation of antioxidant genes by training. Free Radic Biol. Med. 44, 126–131 (2008).

van der Vaart, H., Postma, D. S., Timens, W., Ten Hacken, N. H. T. Acute effects of cigarette smoke on inflammation and oxidative stress: a review. Thorax 59, 713–721 (2004).

Calder, P. C. et al. Dietary factors and low-grade inflammation in relation to overweight and obesity. Br. J. Nutr. 106, S5–S78 (2011).

Jung, J. G., Kim, J. S., Yoon, S. J., Lee, S. M. & Ahn, S. K. Korean alcohol guidelines for primary care physician. Korean J. Fam Pract. 11, 14–21 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Jaegeun Cho and Young-Joo Won; methodology, Jaegeun Cho and Eunvin Kang; formal analysis, Jaegeun Cho; investigation, Jaegeun Cho; data curation, Jaegeun Cho and Se Eun Kim; writing—original draft preparation, Jaegeun Cho; writing—review and editing, Jaegeun Cho, Eunvin Kang, Se Eun Kim, and Young-Joo Won; supervision, Young-Joo Won; project administration, Young-Joo Won; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, J., Kang, E., Kim, S. et al. Associations of sleep duration and sleep quality with lifestyle inflammation score in a nationwide Korean survey. Sci Rep 15, 45562 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29891-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-29891-6