Abstract

In this paper, we designed, built, characterized and demonstrated a cost-effective diffuse optical tomographic (DOT) system for imaging absorbing and fluorescent targets and fluorescence alteration induced by temperature change in a scattering medium. DOT based imaging in a scattering media (such as biological tissue) is highly desired because of its high sensitivity and non-invasive nature. Unfortunately, conventional methods require expensive devices, such as lasers, optical switches, scientific cameras or photon detectors and advanced electronic controlling systems and data acquisition tools. To lower the cost and provide a simple system that can be used by researchers, teachers, and students who have a limited budget, we investigated and tested a method that uses light-emitting diodes (LEDs), a mobile phone-based camera, and a low-cost microcontroller (an Uno R3 board) to achieve the goal with reasonable accuracy. This method includes a hardware system, a software system for hardware controlling, data acquisition and processing, and an imaging reconstruction algorithm. By combining these subsystems, we demonstrated the feasibility of 3-dimensional imaging of absorbing and fluorescence targets and temperature change-induced fluorescence in a scattering medium using a temperature-sensitive fluorophore.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Light-based imaging has revolutionized biomedical research and clinical diagnostics due to its non-invasive nature, high sensitivity, and ability to provide both structural and functional information about biological tissues1,2,3,4. Techniques that measure optical properties—such as absorption, scattering, and fluorescence—are especially valuable in life sciences and medicine for observing physiological changes, detecting abnormalities, and monitoring therapeutic responses in real time1,2,3,4,5. Among them, fluorescence imaging is particularly powerful because it enables molecular-level specificity when paired with appropriate contrast agents or fluorophores4,6,7,8,9.

Diffuse optical tomography (DOT) and its fluorescence-enhanced variant, fluorescence diffuse optical tomography (FDOT), are prominent examples of light-based imaging systems used for visualizing tissue structures and molecular activity in scattering media such as biological tissue1,3,10,11,12,13. These modalities can produce three-dimensional reconstructions of optical properties within tissue volumes and have potential to map dynamic changes such as temperature distributions using temperature-sensitive fluorophores5,9. DOT and FDOT are especially well suited for imaging deep tissues in small animals or superficial layers in humans, making it highly relevant for applications in oncology, neurology, and thermal therapy monitoring14.

Despite these potentials, widespread adoption of DOT and FDOT in an educational or training environment or even a research lab with a low budget remains limited due to the cost and complexity of conventional setups. These typically rely on expensive and monochromatic laser sources, optical switches for light multiplexing, scientific-grade cameras or photon detectors with optical fibers, specialized data acquisition hardware and complicated electronic control systems11,12,13. Such requirements create a significant barrier for students, educators, and researchers in low-resource settings who wish to explore or teach optical imaging techniques. The lack of accessible and affordable platforms also hinders innovation and learning in resource-constrained environments.

To address these challenges, we present a cost-effective DOT and FDOT system capable of performing 3D imaging of both absorption and fluorescence targets, as well as fluorescence alteration mapping induced by temperature change in scattering media. Our system replaces expensive components with accessible alternatives, including light-emitting diodes (LEDs) as illumination sources, a consumer-grade phone camera for image acquisition, and an Arduino Uno microcontroller for control and data synchronization. The complete system integrates hardware, software for acquisition and control, and an image reconstruction algorithm, demonstrating that reasonably accurate diffuse optical imaging can be achieved at a low cost. This approach aligns with the growing movement toward low-cost and open-source scientific tools of advanced imaging technologies2,3,12. By enabling broader participation and reducing economic barriers, our method paves the way for increased hands-on learning, prototyping, and research in biomedical imaging and biophotonics.

Systems and methods

Hardware system

Figure 1 shows the hardware system. The white light photos of the system and the boards of LEDs, amplifier and Uno controller are shown in Figure 1a and b, respectively. The schematic diagrams of the system and the boards are displayed in Figure 1c and d. The LED spatial distribution and numbers, the circuits for controlling LEDs via the Uno R3 board, and the amplifier for the temperature signal are shown in Figure 1e-g, respectively. Table 1 lists the major components of the system and their manufacturer, model, parameters and rough cost information. A 3-gallon tank was filled with an aqueous solution of milk (4.85% v/v, i.e., 400 ml 2% reduced-fat Oak Farms milk purchased from a local grocery store was mixed with 7,850 ml tap water) as a scattering medium. A cuvette (LAB4US, 1Q010) was used as a target to be imaged, which was filled with absorbing material (soy sauce purchased from a local grocery store without further dilution) for absorption imaging or fluorophore aqueous solution (fluorescein, ~ 20 µM) for fluorescence imaging. The volume of the absorbing material or fluorophore solution is ~ 10⋅30⋅10 mm3 (width (X) ⋅ height(Y) ⋅ depth (Z)). The distance from the front surface of the cuvette to the glass wall is the depth along Z direction. A total of 12 LEDs (Thorlabs, LED465E, central wavelength at 465 nm) were positioned on a breadboard. The LED breadboard, an Uno R3 microcontroller and an inverting amplifier are mounted on a piece of black board (Thorlabs, TB4), which was clamped by a holder (Thorlabs, FP01) and positioned vertically against the glass wall of the tank. The LEDs were sequentially switched on via the digital pins (D2-D13) of the Uno R3 microcontroller. When a digital pin was setup high for a short period (such as 0.3–3.3 seconds depending on different cases, see Sect. 3.1), a 5 volts square wave was applied to turn on the LED (Figure 1f). The resistor (60 Ω) was used for limiting the current to protect the LED and the microcontroller. Note that the typical and maximum total output currents from the digital pins are 20 and 40 mA, respectively, and the typical and maximum operating currents for each LED are 20 and 50 mA, respectively. According to the manufacturer’s datasheet, each LED delivers ~ 20 mW of optical power at 20 mA. In our study, we operated the LEDs at ~ 30 mA, corresponding to ~ 30 mW per source, which falls within the typical DOT range (10–30 mW)15. The total cost of the experimental setup, as summarized in Table 1, is approximately $1,700. Several components listed—such as the aluminum breadboard (Thorlabs MB1824)—could be substituted with lower-cost alternatives, and the power supply (Digikey KD3005 D) is not required. Although direct cost comparisons with standard DOT/FDOT systems are challenging due to variations in methodology and hardware, systems incorporating lasers, optical switches, scientific-grade cameras (or multiple PMTs), and high-end data acquisition cards typically run an order of magnitude—or even two—higher in total cost.

White light photos of the system (a) and the boards of LEDs, amplifier and Uno controller (b); schematic diagrams of the system (c) and boards (d); a LED spatial distribution diagram and numbers (their X and Y distance coordinates are in Table 2) (e); circuits for controlling LEDs via the Uno R3 board (f) and the inverting amplifier for the temperature signal (g); a schematic diagram for measuring sample absorption coefficient using a microcuvette.

To monitor the temperature of the sample, a temperature sensor was attached on the cuvette and connected to an inverting amplifier (BOJACK, LM358P, Fig. 1g in which Ri=1 kΩ and Rf=1 MΩ, which gives a gain of −1000). Because it is an inverting amplifier, to get a positive output voltage from the amplifier for the Uno board to acquire, the positive input of the temperature sensor is connected to the ground and the negative output of the sensor was connected to the input resistor of the amplifier (Fig. 1g). The output of the amplifier was acquired by an analog input pin of the Uno R3 board controlled by a laptop and a MATLAB code (see the supplementary information (SI)). The temperature sensor combined with the amplifier was calibrated using a commercial Proster digital thermometer (Proster, 4333090752).

The back scattered LED light or fluorescence from the milk aqueous solution was acquired by a phone camera (iPhone 7 Pro, Apple, CA, US). For fluorescence imaging, two long pass emission filters (FELH0500, FELH0550, Thorlabs) were positioned in front of the camera lens to block the excitation light from the LEDs. To spatially co-register the LEDs with the camera imaging pixels, a small and double-sided paper ruler (RLVNT) was attached on the outside of the glass wall and placed in the field of view of the camera (Fig. 2a-b). Before any experiments, two images were taken for co-registration between sources and detectors. One image was taken by positioning the camera inside the tank and facing the instrument side (Fig. 2a). This image shows the paper ruler and the 12 LED locations (assuming the LED and the paper ruler are on the same XY plane by positioning the LEDs’ tops touching to the glass wall). Thus, the LEDs were co-registered with the one side of the paper ruler. By selecting two pixels on the paper ruler (i.e., the two red circles on the paper ruler in Fig. 2a), the millimeters per pixel can be calculated. Using one of the two pixels (e.g., the corner one in this study) as the origin (X = 0 and Y = 0), the LED’s distance coordinates (X and Y) can be quantified by multiplying their pixel coordinates with the value of millimeters per pixel. The second image was taken after the camera was positioned on its holder outside the tank and the tank was filled with milk solution (Fig. 2b). This image showed the opposite side of the paper ruler. Note that the two sides of the ruler are physically and symmetrically mirrored (see the two red circles on the ruler in Fig. 2a and the two blue circles on the ruler in Fig. 2b). Thus, the ruler was co-registered with the pixels of the camera via the back side of the paper ruler by using the same method. The detector’s distance coordinates (X and Y) can be calculated. In this study, we selected a total of 14 × 23 = 322 locations in the camera field of view as the detectors for DOT (see the blue circles in Fig. 2b). After co-registration, the LEDs and detectors can be plotted in the same XY coordinate system (Fig. 2c). As one example, the specific X and Y coordinates of the 12 LEDs were listed in Table 2. The selected detector coordinates in this study can be found via the following rules: (1) The first detector (i.e., D1 in Fig. 2(c)) was found located at X = 5.18 and Y = 7.73 mm; (2) along both X and Y directions, each detector has a step size of 5 mm; (3) all detectors were distributed on a total of 14 columns and 23 rows. The linear serial number of the detector is arranged along the Y direction (see Fig. 2c).

Note that if the position of the camera on the holder or the LED board is changed, the above co-registration steps must be repeated. During experiments, a video was taken to acquire the light distribution on the surface of the tank when different LEDs were sequentially turned on. The selected detectors were used to sense the light intensity. The average light intensity in a small area (5 × 5 pixels) surrounding each detector location was calculated as the signal strength for imaging reconstruction, which is called spatial averaging (relative to the temporal averaging discussed later). As long as the positions of the LEDs, the ruler (i.e. the tank), and the camera remain unchanged, the coordinate system remains the same for different experiments. Thus, integrating DOT and FDOT enables access to tissue optical properties and fluorescence contrast within a single platform. Our design maintains a fully open optical space between the sample and detector, allowing the emission filter to be inserted or removed directly while still achieving reliable imaging performance without requiring lens-based collimation of the emission light. This approach preserves a low-cost and low-complexity hardware configuration and ensures stable geometry and convenient mode switching, which is particularly advantageous for routine experiments, multi-condition measurements, and longitudinal studies.

The entire system was encapsulated into a dark space (18“x24”x15”) via black boards (Thorlabs, TB4) and structural rails (Thorlabs, XE25L15) to avoid environmental light noise. To characterize the absorption coefficient of the absorbing sample, a micro-cuvette (Thorlabs, CV10Q7F) with an optical path length of 2 mm was adopted (Fig. 1h). Water was used as the benchmark. The intensities from the water and the sample were measured via the phone camera (see the data extraction code in the SI). The effective attenuation coefficient was calculated via Beer-Lambert law.

System controlling, data acquisition, and processing methods

MATLAB can work with Arduino using the MATLAB Support Package, which creates a serial connection over USB and allows users to control the Arduino board through simple MATLAB commands. After setting up the package, users can read data from sensors, write to actuators, and access digital or analog pins without needing to write Arduino IDE code. This method is convenient because it makes use of MATLAB’s strong data analysis and visualization tools while keeping the hardware interaction straightforward. However, since the communication goes through an extra software layer, it may not be suitable for fast or complex tasks that require precise timing or access to custom Arduino libraries. For this project, the support package was chosen because it offers a good balance of ease of use and functionality, more than enough for controlling LEDs and collecting temperature data efficiently from within MATLAB.

Controlling leds and acquiring temperature signal

The goal is to use MATLAB and Uno R3 board to sequentially and accurately turn on and off the 12 LEDs, measure the temperature sensor voltage readings and plot the data (see the code in SI). The function of “arduino” in the code creates a connection between MATLAB and an Arduino board, and an object that can be used with other MATLAB functions to interact with the hardware. By creating an Arduino object using this function, we can perform tasks such as turning on and off LEDs and reading sensor data in the MATLAB environment. After that, the code defines important time settings: how long the LED will stay on (T_LED_on = 0.3 s) and how long to wait after turning off an LED before turning on a new one (T_LED_off = 0.05 s). Next a total of 12 digital pins from D2 to D13 is defined. Before starting any measurements, the code makes sure that all LEDs are turned off. The main measurements are carried out through two “for” loops. The outer loop controls how many times to repeat the LED on/off sequences. The inner loop goes through each LED one by one. The inner loop reads the voltage from analog pin A0, which is connected to the temperature sensor, and saves the reading and time. Then, it turns the LED on for 0.3 s (via a pause function) and waits 0.05 s (via a pause function) before turning on the next one. This process repeats until all LEDS have gone through this process. After all the loops finish, the code turns off all the LEDs and plots the voltage change over time on a graph. Using MATLAB’s pause function to control the LED on/off timing is simple but inefficient—during each pause period, no data is acquired, resulting in only one temperature reading per LED cycle. That limits the total number of temperature data points is the same as the number of LEDs (i.e., 12 in this study). If temperature is stable or slowly changes, this is not an issue. When temperature changes quickly, a faster acquisition is needed. To overcome this limitation and increase the data acquisition rate without disrupting the LED control, the two “pause” functions can be replaced with two “while” loops. These “while” loops continuously collect temperature data during the LED on and off periods until the elapsed time reaches the predefined LED on/off durations. This method allows for multiple data points to be gathered during each lighting event (see Matlab codes in SI).

Extracting the light intensity from phone camera recorded videos for quantifying the absorption coefficient (µa) of the absorbing material via the Beer–Lambert equation

Phone camera recorded videos need to be converted into light intensity. Like our previous studies5, we extracted the pixel intensity changes in selected locations as a function of time. As one example, the attached MATLAB code in the SI analyzes two video recordings—one of a water sample (used as the background) and the other of an absorbing material (e.g., soy sauce)—to estimate the absorption coefficient of the absorber using the Beer–Lambert law. It begins by loading the two videos and defining a region of interest (ROI) centered at a specific pixel location. For both videos, the code extracts a portion of the total frames to compute reliable average intensities. Note that the gamma correction was implemented by raising pixel values to the 2.2 power (see more discussion in the section of “system limitations”). Each frame was converted to grayscale, the pixel values were extracted from the ROI around the specified coordinates, and the average intensity was stored over time. After data acquisition, the intensity was plotted over time for both background and absorbing samples, and the analyzed location was marked on a sample frame. The spatially averaged intensities from all the selected frames were further averaged temporally (so-called temporal averaging). The final intensity was then used in the Beer–Lambert equation to calculate the absorption coefficient (µa), assuming a 2-mm light path (Thorlabs microcuvette).

Quantifying the effective Attenuation coefficient (µeff) of the milk solution

The light diffusion model has been well developed in the literature and is adopted in this study by assuming each LED represents a point source. Based on the photon diffusion model, the measured signal (so-called diffuse reflectance) from the surface of the milk sample can be fitted to the following equation to find the effective attenuation coefficient (µeff) that is needed for image reconstruction later10,

Here, the \(\:R\left(\rho\:\right)\) is the measured signal (i.e., the diffuse reflectance) as a function of \(\:\rho\:=\sqrt{{X}^{2}+{Y}^{2}}\), the distance between a source and a detector on the XY plane. \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}=\sqrt{3{\mu\:}_{a}({\mu\:}_{a}+{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}})}\) is the effective attenuation coefficient in the light diffusion model when the light source is operated at a continuous wave mode (CW) in which \(\:{\mu\:}_{a}\) and \(\:{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}\) are the absorption coefficient and reduced scattering coefficient, respectively. \(\:A\) is a constant and can be found via data fitting or by assigning a known or desired value. The value of \(\:m\) is related to the value of \(\:\rho\:\). It has been found that when \(\:\rho\:\) is significantly larger than 1 transport scattering mean free path (mfp=1/\(\:{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}\)), the light diffusion model can accurately describe the photon distribution in a highly scattering medium so that \(\:m\) is equal to 2. For example, if mfp=1 mm, m=2 when \(\:\rho\:\) >10 mm. In contrast, \(\:m\) =1 when 6<\(\:\rho\:\)<10 mm or ½ when 0.3<\(\:\rho\:\)<1 mm 10. Although the Eq. (1) and the above conclusions are empirical, they are simple and useful to find the value of \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}\) with acceptable accuracy and are used in this study because the value of \(\:\rho\:\) in our system is significantly larger than mfp to allow \(\:m=2\). A MATLAB function, “fminsearch”, was used to find the value of \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}\) by fitting the experimental data to the Eq. (1) (see Sect. 3 in SI).

Quantifying the reduced scattering coefficient (\(\:{\varvec{\upmu}}_{\varvec{s}}^{{\prime\:}}\)) and the absorption coefficient (µa) of the milk solution

Once \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}\) is extracted from the data of \(\:R\left(\rho\:\right)\) and the Eq. (1), the next step is to find \(\:{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}\) (and µa if possible). Unfortunately, \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}\) cannot provide information about \(\:{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}\) and µa because the two are mixed in the expression of \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}\). Normally, either a frequency-domain (FD) or time-domain (TD) DOT system is needed for measuring \(\:{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}\) and µa via both amplitude and phase (for FD) or photon time-of-flight information (for TD)10,13. In addition, spatial frequency domain imaging is another method to extract both \(\:{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}\) and µa by adopting a spatially modulated illumination method16,17,18,19. However, these methods will significantly increase the complexity and cost of the system. Fortunately, it has been reported that \(\:{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}\) and µa can be found even using a CW system by finding \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}\) and the total interaction coefficient \(\:\mu \:_{t} ( = \mu \:_{a} + \mu \:_{s}^{{\prime \:}} \:)\) after incorporating data of \(\:R\left(\rho\:\right)\) at short distances of \(\:\rho\:\) in the measurements10. These measured data can be fitted to the following equation to find \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}\) and \(\:{\mu\:}_{t}\) and further \(\:{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}\) and µa, which is derived based on the photon diffusion equation and an extrapolated boundary condition for a semi-infinite scattering medium (see Fig.S1 in SI)10.

Here, \(\:a\prime \: = \frac{{\mu \:_{s}^{{\prime \:}} }}{{\mu \:_{a} + \mu \:_{s}^{{\prime \:}} }} = \frac{{\mu \:_{t} - \mu \:_{a} }}{{\mu \:_{t} }}\) = \(\:\frac{{\mu\:}_{t}-{{\mu\:}_{eff}}^{2}/\left(3{\mu\:}_{t}\right)}{{\mu\:}_{t}}\) is called transport albedo and describes the fraction of photons that are scattered, rather than absorbed in tissue, which can be represented in terms of \(\:{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}\) and µa or \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}\) and \(\:{\mu\:}_{t}\) if the photon diffusion model is valid. \(\:{r}_{1}=\sqrt{{z}_{0}^{2}+{\rho\:}^{2}}\) and \(\:{r}_{2}=\sqrt{{({z}_{0}+2{z}_{b})}^{2}+{\rho\:}^{2}}\), in which \(\:{z}_{0}=\frac{1}{{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}}=\frac{1}{{\mu\:}_{t}-{{(\mu\:}_{eff})}^{2}/\left(3{\mu\:}_{t}\right)}\approx\:\frac{1}{{\mu\:}_{t}}\) (if \(\:{\mu\:}_{a}\ll\:{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}})\) is the depth at which the light source can be approximated as an isotropic point, and \(\:{z}_{b}=\frac{2}{3{{\upmu\:}}_{\text{t}}}\frac{1+{R}_{eff}}{1-{R}_{eff}}\) is the extrapolated distance from the physical boundary (i.e., Z=0) at Z=-\(\:{z}_{b}\)the photon fluence rate is assumed to be zero. Note that \(\:{R}_{eff}=-1.440{n}_{rel}^{-2}\)+\(\:0.710{n}_{rel}^{-1}+0.668+0.0636{n}_{rel}\) (here \(\:{n}_{rel}=\frac{{n}_{in}}{{n}_{out}})\) is called effective reflection coefficient that considers the refractive index mismatch between the glass (\(\:{n}_{in}\) or the scattering medium if no glass wall exists) and air (\(\:{n}_{out}\)), which may lead to total internal reflection to allow photons reflected back into the glass and the milk solution10. In this study, we simply used \(\:{n}_{in}\)=1.46 and \(\:{n}_{out}\)=1 to avoid considering multiple reflections between the glass of the tank and the milk solution. Thus, only two parameters involved in the Eq. (2) are \(\:{\mu\:}_{t}\) and \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}\). By fitting the measured diffuse reflectance of \(\:R\left(\rho\:\right)\) (a function of \(\:\rho\:\)) to the Eq. (2), both \(\:{\mu\:}_{t}\) and \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}\) can be found, and then \(\:{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}\) and µa can be calculated based on the definitions of \(\:{\mu\:}_{t}\) and \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}\). In addition, if the \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}\) has been extracted using the Eq. (1) via the \(\:R\left(\rho\:\right)\) at large values of \(\:\rho\:\), it can be used in the Eq. (2) to reduce the fitting parameter only \(\:{\mu\:}_{t}\), which was adopted in this study.

In this study, \(\:\rho\:\) (> 20 mm) is much larger than one mfp. Therefore, these data are suitable for extracting \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}\) using the Eq. (1) but may not be useful to effectively extract \(\:{\mu\:}_{t}\) using the Eq. (2) because no data are acquired with small \(\:\rho\:\). To catch the diffuse reflectance \(\:R\left(\rho\:\right)\) at short distances of \(\:\rho\:\), additional experiments were conducted by driving individual LEDs with a much smaller current (such as replacing the 60 Ω resistor by a 10 kΩ resistor) to avoid camera saturation, which allows to acquire \(\:R\left(\rho\:\right)\) at \(\:\rho\:\) as short as 5–15 mm and extract \(\:{\mu\:}_{t}\) when fixing \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}\), and further \(\:{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}\) and µa. Once the background parameters (\(\:{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}\) and µa) are measured, other optical properties can be quantified, such as absorbing heterogeneities15, fluorophore concentration1, quantum yield16, lifetime20, lipid21 and so on.

Forward models

Photon fluence rate of the excitation light in the homogeneous milk solution can be expressed via the standard photon diffusion models, which can be considered as background signal10,22,23.

When a highly absorbing material is embedded in the milk solution (so-called an absorbing target), the distribution of the photons in the milk will be distorted because a small portion of photons will be absorbed by this material23. Thus, the received photons by the detectors will be less compared with the situation when no target exists. This distortion is also called perturbation induced by the absorbing target and can be expressed via the Rytov approximation23,24.

\(\:{\varphi\:}_{ex}({r}_{s}\:,\:{r}_{d})\) and \(\:{\varphi\:}_{e{x}_{BG}}({r}_{s\:},\:{r}_{d})\) are the fluences with and without the absorbing target, respectively. \(\:r\) is the position vector of each voxel in the imaging space; \(\:{\varDelta\:\mu\:}_{a}\left(r\right)={\mu\:}_{a}\left(r\right)-{\mu\:}_{a\_BG}\left(r\right)\), which is the absorption coefficient difference between the absorbing target and the background milk solution. The specific expression of the Green’s function \(\:{G}_{ex}\) is given in the Equation S2 in SI after considering the semi-infinite boundary condition.

For fluorescence imaging, the fluorescence fluence can be expressed as following Eq. 22

\(\varepsilon\) and \(\:Q\) are the molar extinction coefficient at the excitation wavelength (~ 7900 mm− 1/M at 465 nm in ethanol25, M = mol/liter) and the quantum yield of the fluorophore (~ 0.97 for fluorescein in ethanol26, respectively. When treated as constants, they can be canceled if a relative concentration image is reconstructed (which will be adopted in this study), or a forward model with a ratio format can be adopted in the image reconstruction. \(\:C\left(r\right)\) is the fluorophore concentration at the location \(\:r\) and its relative value will be imaged in this study. Its absolute value may be able to be quantified if a known concentration sample can be measured and used to normalize the data. \(\:{D}_{fl}\:\left(=1/{{3{\upmu\:}}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}}^{fl}\right)\:\) is the photon diffusion coefficient and \(\:{G}_{fl}\) the Green’s function at the emission wavelength, respectively, in which the \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}^{fl}\) and \(\:{{{\upmu\:}}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}}^{fl}\) extracted from previous steps will be used. The specific representation of \(\:{G}_{fl}\) is given in the Equation S3 in SI after considering the semi-infinite boundary condition.

Because the adopted fluorescein is temperature sensitive. Its emission strength increases when its temperature rises5. Based on this fact, the temperature-induced fluorescence change can be imaged via FDOT, which should represent the temperature change. If two measurements can be conducted at different temperature, their fluorescence difference can be used as the data for FDOT imaging. If assuming the temperature-induced fluorescence change is caused by the quantum yield change, based on the Eq. (5a), the difference can be expressed as

Thus, the reconstructed image should represent \(\:C\left(r\right)\varDelta\:Q(r,T)\). When the concentration in the target can be considered a constant, the image will be directly related to the temperature-induced quantum yield change, \(\:\varDelta\:Q\).

Image reconstruction

The Eqs. (3, 4, 5, S1-S3) are linearized equations relative to the unknown vector \(\:x\) (i.e., \(\:{\varDelta\:\mu\:}_{a}\left(r\right)\) or \(\:C\left(r\right)\)). Thus, for each specific measurement between a source \(\:{s}_{i}\) and a detector \(\:{d}_{j}\) can be generally expressed as23

The left side of the equation \(\:{M}_{{s}_{i}{d}_{j}}\) represents a specific measurement between the source-detector pair (i.e., the left sides of the Eqs. (4–5b, S2-S3). The right side of the equation indicates the model prediction, in which \(\:\left({W}_{{s}_{i}{d}_{j}{r}_{k}}\right)\) is a weight (or sensitivity) vector induced by the source \(\:{s}_{i}\) and the detector \(\:{d}_{j}\), and \(\:\left({x}_{{r}_{k}}\right)\) is the unknown vector at all the image voxels \(\:{r}_{k}\). The symbol \(\:*\) denotes a matrix product. When S sources and D detectors are adopted, the total measurement number is N (= S\(\:\times\:\)D). Thus, \(\:M\) has a dimension of N\(\:\times\:\)1. If R denotes the total voxel number, \(\:W\) becomes a N\(\:\times\:\)R matrix (so-called a weight or sensitivity matrix) and \(\:x\) has a dimension of R\(\:\times\:\)1. Thus, the unknown \(\:x\) can be found by solving the Eq. (7) via different ways.

Tikhonov regularization is a commonly used method to solve the Eq. (7) for image reconstruction and can be expressed as27

The optimization seeks the \(\:x\) (i.e. \(\:{\varDelta\:\mu\:}_{a}\) in DOT or \(\:C\left(r\right)\) in FDOT) that best fits the measured data \(\:M\) while remaining physically plausible (i.e., not unnaturally large or noisy). \(\left\| \right\|\) represents squared Euclidean (L2) norm. The objective function has two parts: (1) data-misfit term \(\left\| {Wx - M} \right\|^{2}\), which enforces agreement between model predictions (via the weight matrix \(\:W\)) and the observed data \(\:M\); (2) regularization term \(\:\lambda \:\left\| x \right\|^{2}\), which penalizes large or unstable solutions, and the scalar \(\:\lambda\:\) tunes the trade-off between fidelity and stability. Minimizing this Tikhonov-regularized least-squares cost yields a stable estimate of \(\:x\) even when the inverse problem is ill-posed or the data are noisy.

Two options are available to achieve goal the expression (7): closed-form solutions and iterative methods. In image reconstruction, such as DOT and FDOT, the choice between closed-form solutions and iterative methods depends on model complexity and system size. Closed-form solutions are fast, easy to implement, and suitable when the forward model is linear or approximately linear—such as under the Born or Rytov approximation—with a homogeneous background, and simple regularization like L2 (Tikhonov). These solutions work well for prototyping and educational purposes, where interpretability and computational efficiency are important. However, closed-form approaches become impractical in large-scale problems due to memory demands and numerical instability from explicit matrix inversion. They also fail when the system is nonlinear, significantly ill-posed, or requires constraints. In contrast, iterative methods offer scalability and flexibility, making them preferable for high-dimensional, constrained, or real-time reconstruction. Given that our system is relatively simple, with a modest number of voxels (~ 103 voxels) and a measurable, uniform background, the assumption for a closed-form solution is valid and educationally effective for our application, providing clear insight into the relationship between measurement data, sensitivity, and absorption or fluorescence changes. The following equation provides the closed-form solution of the Eq. (7)28

\(\:T\) represents matrix transpose and \(\:I\) is an identity matrix, which has a dimension R\(\:\times\:\)R, the same as the dimension of \(\:{W}^{T}W\). The parameter \(\:\lambda\:\) controls the strength of regularization in image reconstruction. It balances data fidelity and solution stability by penalizing large or unstable values in the reconstructed image. A larger lambda suppresses noise and smooths the result but may over smooth true features, while a smaller \(\:\lambda\:\) fits the data more closely but risks amplifying noise and artifacts. Choosing an appropriate lambda is crucial for achieving accurate and reliable reconstructions, especially in ill-posed problems like DOT. Setting λ = α·mean(diag(WᵀW)) automatically scales regularization to match data units, making α a dimensionless tuning knob. It damps ill-conditioned directions, improves numerical stability, and provides a practical, problem-size-independent starting value that often lands near the optimal ridge penalty, reducing iterative α searches across varied datasets.

Results and discussion

LED illumination and temperature calibration

To test how accurately we can control the LEDs on and off, Fig. 3a shows the measured time sequence of turning on and off the LEDs. To save space, we only showed the results for LEDs 1, 2 and 12. In the controlling code, we required each LED to be turned on for 0.3 s and waited for 0.05 s before turning on the next LED. Note that fast switching between LEDs is needed for imaging temperature change via FDOT, although a longer LED exposure time (3 s) is adopted for imaging the absorbing target. The results in Fig. 3a showed that each LED was turned on for ~ 0.333 s, which is ~ 0.0333 s (i.e. ~11%) longer than the design. This is mainly due to the relatively low sampling rate of the phone camera in this experiment (30 Hz, 0.0333 s/frame) and the slow serial data transmission between the Uno R3 and MATLAB code. An > 0.033 s gap exists between the LED 1 and LED 2 pulses, which ensures no temporal overlapping in optical signals from any two LEDs. Once all 12 LEDs finish the illumination, one can repeat the above steps when multiple repeated measurements are needed.

Figure 3b and c show the temperature calibration results. Figure 3b displays the measured voltage signal from the temperature sensor that was placed inside the fluorophore-solution-filled cuvette. The cuvette with the fluorophore solution was heated up via a hot water bath before being submerged into a water (not milk) bath at room temperature. The same temperature sensor data were also read by the commercial Proster thermometer for calibrating the voltage signal. The dynamic change of the fluorescence emission from the cuvette sample was also simultaneously recorded by the phone camera. Figure 3b indicates that the voltage signal (blue) and its filtered result (green) match the temperature data (red) well. The temperature sensitivity of the voltage signal can be calculated as 0.041 v/oC (i.e., (1.68–0.68) v/(47.7–23) oC). To further validate this result, we used the Proster thermometer to measure the temperature of ice water (0 °C) and fingertips (35.8 °C). Then, the same sensor combined with the amplifier was used to measure the voltage signal from the above two samples. A sensitivity of 0.042 v/oC was found, which is very close to the result in Fig. 3b. Thus, Fig. 3b can be used to convert a voltage signal into temperature. Figure 3c displays the dynamic fluorescence change (blue), its filtered data (green), and the temperature data (red) vs. time (note that the temperature data in Fig. 3c and b are the same). The temperature sensitivity of the fluorescence signal can be calculated as 0.24%/oC (i.e., (0.463 − 0.438)/0.438/(47.7–23 °C)*100%). This result is larger than the one (0.059%/oC) reported in our previous studies5. Two major reasons may contribute to the underestimation in our previous study. (1) Gamma correction was not considered previously, which led to a factor of ~ 2.2 times underestimation of the intensity and therefore the temperature sensitivity. However, the estimated temperature value in the previous study is not affected because this 2.2 factor is canceled when calculating the ratio between the percentage of the intensity change to the temperature sensitivity. (2) In current measurement, the thermal sensor was inserted in the cuvette and directly measure the solution temperature via the thermometer, while the previous measurement used an infrared camera to measure the cuvette surface temperature, which is not as accurate as current one.

Absorption coefficient of the absorbing material

The measured absorption coefficient of the raw soy sauce was 1.67 ± 0.012 mm⁻¹. This result indicates that soy sauce exhibited very strong absorption at the adopted blue LED wavelengths (465±10 nm, FWHM 25 nm), making it a promising low-cost absorbing material for reducing the cost. In the experiment, water was used as the control sample. Since water transmits most of the blue light, the intensity recorded after passing through the water was high and could easily saturate the camera, leading to potential underestimation of the absorption coefficient. To address this, the LED power supply was set to a low level (2.3 v), ensuring that the signal through the soy sauce was still detectable while the control (water) remained within the dynamic range of the camera and did not cause saturation.

Light signal as a function of the source-detector distance rsd (i.e., r) (blue) and the fitted curves (green) via the Equation 1 for all the 12 LED sources. Note that the saturated data at short rsd and the low signal at long rsd have been manually removed. AE/AF were not locked but the data were spatially and temporally averaged. The full data sets are shown in Fig.S2(a).

Effective Attenuation coefficient (\(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}^{ex}\), \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}^{fl}\)), reduced scattering coefficient (\(\:{{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}}^{ex}\), \(\:{{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}}^{fl}\)) and absorption coefficient of the milk solution (\(\:{{\mu\:}_{a}}^{ex}\), \(\:{{\mu\:}_{a}}^{fl}\))

Figure 4 shows the measured light intensity (i.e. \(\:R\left(\rho\:\right)\)) as a function of the source-detector distance rsd (i.e., ρ) for the 12 LEDs (S) and different detectors (D). The blue circles are the raw data after removing the saturated data at short rsd and the low signal at long rsd (see Fig.S2(a) for all the raw data without removing any). The green circles are the fitted data via the Eq. (1) by setting \(\:m\)=2 and \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}^{ex}\) a specific value. The \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}^{ex}\) for each LED was extracted based on the fitting method described in the Sect. (3) in 2.2 and showed in Fig. 5. The LEDs 1, 5, 8 and 11 exhibit slightly larger \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}^{ex}\) (0.0431, 0.0397, 0.0419, and 0.0490, with a mean 0.0434 ±0.0035 mm− 1) compared with LEDs 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10 and 12 (0.0269, 0.0240, 0.0248, 0.0278, 0.0378, 0.0365, 0.0217, and 0.0314, with a mean 0.0289 ±0.0055 mm− 1). The mean of the \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}^{ex}\) for all the 12 LEDs is 0.0337 ±0.0084 mm− 1. These results agree with a fact that we found in experiments that LED 1, 5, 8 and 11 showed slightly darker blue than other LEDs, which made their intensity decay faster than other LEDs (although we are not clear how much the wavelengths are different between them). Once the \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}^{ex}\) were extracted, \(\:{{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}}^{ex}\) and \(\:{{\mu\:}_{a}}^{ex}\) were quantified using the method described in Sect. (4) in 2.2, which were \(\:{{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}}^{ex}\)=0.34 and \(\:{{\mu\:}_{a}}^{ex}\)=0.0018 mm− 1 for the dark blue LEDs and \(\:{{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}}^{ex}\)=0.326 and \(\:{{\mu\:}_{a}}^{ex}\)=0.0009 mm− 1 for the light blue LEDs (we only tested one LED in each category). If combining these data, the mean values for all the 12 LEDs are \(\:{{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}}^{ex}\)=0.333 and \(\:{{\mu\:}_{a}}^{ex}\)=0.0014 mm− 1. For convenience, we only used the \(\:{{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}}^{ex}\)=0.333 to calculate \(\:{z}_{0}\) and \(\:{z}_{b}\), and also ignored \(\:{{\mu\:}_{a}}^{ex}\)=0.0014 mm− 1 in the image reconstruction. To find the \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}^{fl}\), \(\:{{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}}^{fl}\) and \(\:{{\mu\:}_{a}}^{fl}\)for fluorescence emission light (> 550 nm), we adopted a green LED that matches the emission light color of the fluorophore to repeat the experiments. The results are found as \(\:{\mu\:}_{eff}^{fl}\)=0.0112, \(\:{{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}}^{fl}\)=0.3010 and \(\:{{\mu\:}_{a}}^{fl}\)=0.00014 mm− 1, respectively. Similarly, we only used the \(\:{{\mu\:}_{s}^{{\prime\:}}}^{fl}\)to calculate \(\:{z}_{0}\) and \(\:{z}_{b}\), and also ignored \(\:{{\mu\:}_{a}}^{fl}\) in the image reconstruction. The above results are in agreement with those in the literature4,29,30.

Weight (or sensitivity) matrix

As an example, Fig. 6 shows the weight (or sensitivity) distribution in the XYZ 3D imaging volume induced by a source and a detector (i.e. S = 5 and D = 174). The source and detector locations are indicated on the figures by a red and a blue square, respectively. The distance between the source and detector is 56.69 mm. The areas along the source and detector (blue areas) show the sensitive areas, and the negative value means that the absorbing target reduces the signal, which is the opposite of the fluorescence. The most sensitive areas are the areas at a shallow depth (i.e., close to the boundary). This is because in our study, a reflective (rather than an absorbing) boundary was adopted due to the refractive index mismatch between the milk solution (or glass) and air. At a shallow depth, the most sensitive area is close to the source and the detector, which is meaningful because an absorbing target can significantly block photons to be emitted into the medium from the source or be received by the detector. When the absorbing target is in the middle area, photons have more pathways to propagate from the source to the detector, which can decrease the sensitivity of the middle area. When increasing the depth, the most sensitive areas are gradually shifting to the middle areas. This is because the middle areas have relatively shorter distances from the source to the detector and can block diffused photons more efficiently compared with those areas vertically right below the source or the detector. Lastly, one should keep in mind that the photon diffuse model becomes inaccurate at the areas that are close to a source, a detector, or a boundary. Therefore, it is wise to image areas that are far away from these areas if the diffuse model is used.

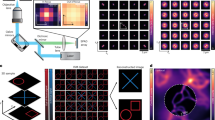

Reconstructed images

The absorbing target

Figure 7 shows the 2D slices of the 3D reconstruction of the \(\:{\varDelta\:\mu\:}_{a}\left(r\right)\) of the absorbing target that is marked as the three white rectangles. Each LED was exposed for 3 s. The reconstructed images correctly and accurately mapped the XY locations of the target at the three depths (15, 20, and 25 mm) with some artifacts surrounding the target. However, the image showed stronger absorption at the depth = 15 mm than that at other depths while the target should have the same absorption coefficient at the three depths. This may be caused by the fact that the shallow area is more sensitive to the target than the deep area, which can be seen from the weight matrix discussed in 3.4. Another observation is that the maximum of the reconstructed value of \(\:{\varDelta\:\mu\:}_{a}\left(r\right)\) is 0.0142 mm− 1, which is about 10 times higher than that of the milk solution (0.0014 mm− 1) but significantly lower than the measured absorption coefficient of the soy sauce (1.67 mm − 1). This indicates that the soy sauce generates an over strong perturbation in \(\:{\varDelta\:\mu\:}_{a}\) so that the diffuse model and reconstruction algorithm become less effective because they are linear systems.

(a) Reconstructed 3D images of the absorbing target (white rectangles) with an optimized α = 2.41 (AE/AF unlocked mode). (b) The L-curve to show the relationship between the regularization term (\(\left\| {\Delta \mu _{a} ^{2} } \right\|\)) and the data misfit term (\(\left\| {W\Delta \mu _{a} - M} \right\|\)). (c) The curvature of the L-curve vs α, which shows that when α=2.41 the curvature reaches the maximum (note that the red star on (b) represents to the maximum curvature). (d) The maximum of the reconstructed as a function of α (the inset is the same data in a log-log format)

In our reconstruction, we optimized the regularization factor α by scanning its value from 0.1 to 10 with a step size 0.1 and repeated the reconstruction for each α. Figure 7b plots the reconstructed regularization term (\(\left\| {\:\Delta \:\mu \:_{a} } \right\|^{2}\)) vs. the data misfit term (\(\left\| {W\Delta \:\mu \:_{a} - M} \right\|\)), which is called the L-curve in the field of image reconstruction27. This curve indicates that when α is increased (i.e. stronger regularization) the strength of the reconstructed value \(\left\| {\:\Delta \:\mu \:_{a} ^{2} } \right\|\) becomes weaker and the fitting less effective (i.e. fitting error \(\left\| {W\Delta \:\mu \:_{a} - M} \right\|\) increases). This is typical in image reconstruction and means the algorithm sacrifices more data fitting performance to reduce the high frequency variation in the reconstructed \(\:{\Delta\:}{\mu\:}_{a}\), so that the image is smoother, less noisy, and more stable. However, this may sacrifice some information about the target. Therefore, selecting an optimized α is important to balance the target information and image quality and artifacts. The optimized α value is usually selected based on the point of maximum curvature on the L-curve27. Figure 7c plots the curvature of the L-curve vs. α, which shows that when α = 2.41 the curvature reaches the maximum (note that the red star on Fig. 7b represents the maximum curvature). We eventually selected this α value and showed the reconstructed the images in Fig. 7a. In Fig. 7d, the maximum of the reconstructed \(\:{\Delta\:}{\mu\:}_{a}\) is plotted as a function of α (the inset is the same data in a log-log format). This result clearly shows that the reconstructed value quickly decays as the increase of α. The result when α = 2.41 is also plotted in this figure that is in the middle of the curve. For comparison, we also showed the reconstructed images when α = 30 in Fig. 8. Compared with Fig. 7a, the images are smoother, having larger sizes, and less noisy, but the reconstructed \(\:{\Delta\:}{\mu\:}_{a}\) is significantly reduced with a maximum 0.0057 mm− 1. The locations on XY plane are correct and accurate; however, the shallow slice (15 mm) shows larger reconstructed values than deep slices (20 and 25 mm).

Note that the data showed in this section were acquired when the camera’s auto exposure and focus (AE/AF) locked function was not activated but the data must be carefully processed, including removing the initial intensity spikes observed immediately after LED activation, which was attributed to AE/AF adjustments by the camera and processing the raw data using the spatial and temporal averaging methods. A study with AE/AF locked mode was also conducted, and the results are given in Fig.S2(b-c). The conclusion is that if a phone camera can activate the AE/AF locked function, it is wise to do so. If this is not the case for some user’s phone camera, the raw data must be carefully processed to ensure the removal of those artifacts or noises. Thus, it is still capable of achieving meaningful images by following the guidance in this work.

The fluorescent target at constant room temperature

To image the fluorescent targe at the room temperature (~ 20 °C), two measurements were conducted: (1) without a target and (2) with the fluorescent target (but both have the emission filters installed). We found that background images showed some signals, which may be due to milk autofluorescence plus a small portion of the LED excitation light leakage (if any). Therefore, subtracting the background signals from the target signals is critical. Figure 9 displays the 2D slices of the 3D reconstructed concentration of the fluorophore \(\:C\left(r\right)\) (note that AE/AF was locked, each LED was exposed for 0.3 s and turned off for 0.2 s; Fig.S3 shows the source and detector distribution on the XY plane; Fig. S4 the fluorescence signal difference between the two measurements; and Fig.S5 one example of the sensitivity distribution from S5 and D111). The image was normalized by its maximum value so that the constants in front of the integration in the Eq. (5a) that are related to the target and background solution (such as \(\:\varepsilon,Q\), \(\:{4\pi\:D}_{ex}\), \(\:{4\pi\:D}_{fl}\), but not \(\:M\)) can be canceled so that their accuracy is not important. To minimize the effect of the different excitation intensities from the 12 LEDs, we quantified their intensities individually (Fig.S6). These normalized intensities were used as compensation factors to divide the measurement data before image reconstruction. Again, the reconstructed XY locations are correct and accurate; however, the higher concentration is shown in the shallow slice (30 and 35 mm) than in the deep slices (40 mm). Compared with the image of the absorbing target in Fig. 7a and Fig. 8, stronger artifacts can be found on all the slices. The artifacts are mainly located at the lower right corner from Z = 25 to 40 mm. In addition, the last two slices (45 and 50 mm) also show strong artifacts where no target is located. This can be explained in terms of the following possible reasons. First, the fluorescence emission signal in FDOT is usually much weaker than the scattered light signal directly from the LEDs in DOT. Therefore, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) may be lower. Second, although the light strengths of the 12 LEDs (i.e., \(\:M\) in the Eq. 6b) have been compensated via experimentally measured data, this can still induce some noise. However, it is not an issue in DOT because \(\:M\) is canceled out in the Eq. (5) due to the ratio format. Third, the error between the forward model and the experimental data (see Sect. 4 in SI for more details) may be more significant in a low SNR environment.

Fluorescent target with varying temperature

To avoid significant temperature variation during an FDOT scanning, we limited each LED exposure to only 0.2 s and turned it off for another 0.2 s. Thus, it only took < 5 s to finish one FDOT scanning. The fluorescein-filled cuvette was heated up to ~ 47 °C via a hot water bath before submerging it into the milk solution. Two measurements were conducted: (1) right after submerging the heated target into the milk solution and (2) about four minutes later when the temperature decayed to the room temperature ~ 23 °C. The data from the 2nd measurement were subtracted from the 1 st one and the difference was used as the fluorescence change. Based on the Eq. 5(b), the reconstructed image represents multiplication between the fluorophore concentration and the quantum yield change, \(\:C\left(r\right)\varDelta\:Q(r,T)\). Figure 10 shows the 2D slices of the 3D reconstruction, which represents the temperature-induced quantum yield change. The white rectangles indicate the target locations. Similarly, the image was normalized by its maximum so that the value is relative and dimensionless. The target XY locations are correct and accurate. The target was located at the depth of 25, 30 and 35 mm and the images correctly show the depth. Some strong artifacts can be observed at the lower right corner. This result shows that the temperature-induced fluorescence change can be imaged by the FDOT system while the reconstructed images only show noises or artifacts when temperature change is ignorable (~ 0 °C, see Fig.S7).

However, we failed to achieve a confident conclusion of quantifying the temperature change based on the reconstructed FDOT images. The major reason is the variation of the reconstructed results, which may be due to the following major reasons: (1) the temperature is difficult to be well controlled due to our limited resources and budget, so we adopted the simple way to let the sample naturally cool down, which usually is fast and nonlinear; (2) intrinsically FDOT (also DOT) is an ill-posed inverse problem, which leads to the reconstructed results highly depends on the selected reconstruction parameters (such as α in our study)23; (3) the fluorescence change induced by temperature change is limited (depending on the temperature sensitivity of the fluorophores)5, which makes the quantitative studies become difficult. However, it may be possible to do so if significant efforts can be applied to address these challenges, which may be explored in future.

System limitations

While the Uno R3 is widely accessible and easy to program, it is based on the ATmega328P microcontroller and has a single 10-bit ADC with a relatively low sampling rate (< ~ 10 kHz). When interfacing with MATLAB via the arduino support package, the sampling rate can be even slower because of the communication via a serial link and MATLAB’s high-level interpreted commands. These constraints make the Uno R3 suitable for low-speed control tasks (such as LED controlling and temperature acquisition in this study).

The phone camera is a consumer-grade device, not designed for scientific imaging31,32,33. Several factors could affect the linearity and fidelity of intensity measurements when using an iPhone 7 Plus camera for DOT or FDOT. First, although our results showed a reproducible way to obtain stable brightness signals, rgb2gray operates on gamma-encoded RGB and compresses the dynamic range of the image using a nonlinear transformation (approximately \(\:{signal\:}^{1/2.2}\)). It can distort the true linear relationship between photon intensity and pixel value and introduce small numeric differences (although usually ignorable compared with other factors induced artifacts in DOT and FDOT). Another way that may be adopted in future is to use a third-party software (such as FFmpeg) to directly acquire the brightness of a video to achieve a more precise result, which may involve directly extracting the Y (luma) channel from the original YCbCr video format. This bypasses color blending and gamma corrections inherent in RGB conversion, providing a truer measure of scene luminance as recorded by the camera’s encoding pipeline. Of course, it will increase the complexity of the procedures. Second, AE/AF adjustments may introduce instability or artifacts. To mitigate these distortions, we implemented gamma correction by inverting the encoding function (i.e., raising pixel values to the 2.2 power after normalization), thereby approximating the linear intensity. We also removed initial intensity spikes to improve the temporal consistency in the recorded intensity profiles. It is wise to use AE/AF locked mode when possible. Third, the camera gain (which can be controlled by focusing the camera at different locations that have different light intensities) can significantly affect the linear dynamic range of the measurable intensity range (Fig.S8). Usually, when system is operated at a low gain, it can response linearly in a large range while a high gain leads to a narrow linear range. In our DOT experiments, we observed the saturated signals (Fig.S2(a)), which may imply that lowering the camera gain may be helpful to reduce artifacts and noises by improving the linear dynamic range.

For spectral selection, we chose to use gray scale. This decision was based on practical considerations. Our system used both 465-nm excitation and > 550 nm emission light, which may not map cleanly to the iPhone’s fixed RGB sensor filters (unknown spectra). Relying on any single-color channel could lead to spectral misrepresentation and saturation (observed in experiments). Using the grayscale output provided a simplified and balanced approximation of total intensity while avoiding complications related to color channel spectral overlap or nonlinearity. MATLAB provides a function, rgb2gray, to simply convert a RGB image to grayscale via a weighted sum, gray = 0.2989R + 0.5870G + 0.1140B. Although this conversion may also induce some spectral distortion and is not physically exact, this approach reduced complexity and enabled more robust data processing under the limitations of consumer-grade hardware.

When recording in its default video mode, a phone camera usually captures and stores video using 8 bits per color channel, providing 256 (i.e., 28) intensity levels per channel. This 8-bit format is standard for consumer-grade video and is primarily optimized for visual presentation rather than quantitative analysis. Although the internal camera sensor may operate at higher precision, the final recorded video remains limited to 8-bit output. Similarly, MATLAB’s rgb2gray function operates on standard 8-bit RGB input and produces a grayscale image with the same 8-bit depth. Therefore, the use of rgb2gray on video frames is consistent with the video’s original encoding and does not introduce a mismatch in precision. However, the 8-bit limitation results in a restricted dynamic range, which can be a drawback. While gamma correction can help restore the approximate linearity of the signal, it cannot recover the finer intensity gradations that would be available in higher bit-depth formats. Other minor factors, such as white balance correction and automatic color enhancement (when not disabled by the manufacturer), may also introduce intensity distortions. However, compared to the previously discussed factors, these effects were not found to significantly impact the results in the current study. While the iPhone 7 Plus we used records 8-bit video, for improved accuracy and dynamic range in future studies, a higher bit-depth recording options—such as high dynamic range (HDR, 10-bit), ProRes for videos (10-bit) and ProRAW for photos (12-bit)—may be options. They are available on advanced iPhones (e.g., iPhone 13 Pro or newer), combined with software (such as Final Cut Camera, ProShot, ProCam, Halide, Filmic Pro) capable of preserving and processing the higher bit-depth data, enabling/disabling auto exposure (gain, time, or color) adjustment, and so on (although extra cost may be applied for a more advanced phone, a significantly large storage space, or a third-party software). In addition, the dark noise of the phone camera can be easily reduced by the adopted spatial and temporal averaging (Fig.S9). Therefore, adopting these data averaging methods is useful to achieve high quality data.

The errors between the forward model and the experimental data (especially for those source-detector pairs that are close to ignored boundaries) can generate non-ignorable noises and should be addressed in the future. Semi-infinite geometry model is limited when multiple boundaries exist in experiments. Deep learning and artificial intelligence can provide alternative solutions to address this issue when a significant amount of data is available to train the model without relying on the specific boundary conditions.

Lastly, a perturbed homogeneous tissue model was used in this study to establish and validate the multimodal DOT/FDOT imaging workflow under controlled optical conditions. Real biological tissues exhibit heterogeneity, which may influence reconstruction performance and may require incorporating spatial priors or more advanced reconstruction strategies. Future work will extend the system to heterogeneous phantoms and biological tissues, where such improvements will be implemented as needed.

Conclusions

This study successfully developed, tested, and characterized a low-cost system for diffuse optical tomography (DOT) and fluorescence DOT (FDOT). By integrating an Uno R3 microcontroller with MATLAB, multiple light sources were precisely controlled to sequentially illuminate a scattering medium with sub-millisecond accuracy. A standard smartphone camera was used as a high-density detector array—capturing signals from 322 positions in DOT and 240 in FDOT—far exceeding the capabilities of traditional fiber-and-photodetector systems. Spatial co-registration between light sources and detectors was accurately achieved using a paper ruler method. The recorded videos were processed using custom methods developed in this study, converting them into scientific signals for characterizing the optical properties of the medium and performing DOT and FDOT imaging. These techniques enabled successful 3D imaging of absorbing and fluorescent targets, as well as temperature variations, within a scattering medium. Owing to its low cost and robust functionality, this system holds significant potential for researchers, educators, and students—from high school to medical school—working with limited resources for research, education, or training.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary material.

References

Corlu, A. et al. Three-dimensional in vivo fluorescence diffuse optical tomography of breast cancer in humans. Opt. Express. 15, 6696–6716 (2007).

Aharoni, D. & Hoogland, T. M. Circuit Investigations With Open-Source Miniaturized Microscopes: Past, Present and Future. Front. Cell. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2019.00141 (2019).

Dehghani, H. et al. Near infrared optical tomography using NIRFAST: algorithm for numerical model and image reconstruction. Commun. Numer. Methods Eng. 25, 711–732. https://doi.org/10.1002/cnm.1162 (2009).

Tuchin, V. V. Handbook of Optical Biomedical Diagnostics, Page 324 (Society of Photo Optical, 2002).

Cai, M. et al. A cost-effective approach to measurements of fluorophore temperature sensitivity and temperature change with reasonable accuracy. Sci. Rep-Uk. 14, 6823. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57387-2 (2024).

Okabe, K., Sakaguchi, R., Shi, B. & Kiyonaka, S. Intracellular thermometry with fluorescent sensors for thermal biology. Pflügers Archiv - Eur. J. Physiol. 470, 717–731. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-018-2113-4 (2018).

Terai, T. & Nagano, T. Small-molecule fluorophores and fluorescent probes for bioimaging. Pflügers Archiv - Eur. J. Physiol. 465, 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-013-1234-z (2013).

Ranjit, S., Lanzanò, L., Libby, A. E., Gratton, E. & Levi, M. Advances in fluorescence microscopy techniques to study kidney function. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 17, 128–144. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-020-00337-8 (2021).

Feng, G., Zhang, H., Zhu, X., Zhang, J. & Fang, J. Fluorescence thermometers: intermediation of fundamental temperature and light. Biomaterials Sci. 10, 1855–1882. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1BM01912K (2022).

Farrell, T. J., Patterson, M. S. & Wilson, B. A diffusion theory model of spatially resolved, steady-state diffuse reflectance for the noninvasive determination of tissue optical properties in vivo. Med. Phys. 19, 879–888. https://doi.org/10.1118/1.596777 (1992).

Pouriayevali, M. et al. Advancing Near-Infrared probes for enhanced breast cancer assessment. Sensors-Basel 25, 983 (2025).

Markow, Z. E. et al. Ultra high density imaging arrays in diffuse optical tomography for human brain mapping improve image quality and decoding performance. Sci. Rep-Uk. 15, 3175. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85858-7 (2025).

Chekin, Y. et al. A compact time-domain diffuse optical tomography system for cortical neuroimaging. Imaging Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1162/imag_a_00475 (2025).

Stuker, F., Ripoll, J. & Rudin, M. Fluorescence molecular tomography: principles and potential for pharmaceutical research. Pharmaceutics 3, 229–274 (2011).

Yuan, G., Alqasemi, U., Chen, A. Z., Yang, Y. & Zhu, Q. Light-emitting diode-based multiwavelength diffuse optical tomography system guided by ultrasound. J. Biomed. Opt. 19, 126003–126003. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.jbo.19.12.126003 (2014).

Zhao, Y. & Roblyer, D. Spatial mapping of fluorophore quantum yield in diffusive media. J. Biomed. Opt. 20, 086013–086013. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.jbo.20.8.086013 (2015).

Alec, B. W. & Jansen, E. D. Development and characterization of a combined fluorescence and spatial frequency domain imaging system for real-time dosimetry of photodynamic therapy. J. Biomed. Opt. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.30.S3.S34103 (2025).

David, J. C., Frédéric, P. B., Joseph, A. & Frederick, D. Bruce Jason, T. Quantitation and mapping of tissue optical properties using modulated imaging. J. Biomed. Opt. 14, 024012. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.3088140 (2009).

Yan, B. et al. Deep ensemble model for quantitative optical property and chromophore concentration images of biological tissues. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 34, 4999–5008. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2025.3593071 (2025).

Nothdurft, R. E. et al. In vivo fluorescence lifetime tomography. J. Biomed. Opt. 14, 024004. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.3086607 (2009).

Zhao, Y. et al. Shortwave-infrared meso-patterned imaging enables label-free mapping of tissue water and lipid content. Nat. Commun. 11, 5355. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19128-7 (2020).

Li, X., Chance, B. & Yodh, A. G. Fluorescent heterogeneities in turbid media: limits for detection, characterization, and comparison with absorption. Appl. Opt. 37, 6833–6844. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.37.006833 (1998).

O’Leary, M. A., Boas, D. A., Chance, B. & Yodh, A. G. Experimental images of heterogeneous turbid media by frequency-domain diffusing-photon tomography. Opt. Lett. 20, 426–428. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.20.000426 (1995).

Boas, D. A. A fundamental limitation of linearized algorithms for diffuse optical tomography. Opt. Express. 1, 404–413. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.1.000404 (1997).

https://www.photochemcad.com/databases/common-compounds/xanthenes/fluorescein

Yu, D., Hwang, C., Zhu, H. & Ge, S. The Tikhonov-L-curve regularization method for determining the best geoid gradients from SWOT altimetry. J. Geodesy. 97, 93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-023-01783-5 (2023).

Šušnjar, S. et al. Two-stage diffuse fluorescence tomography for monitoring of drug distribution in photodynamic therapy of tumors. J. Biomed. Opt. 30, 015003. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.jbo.30.1.015003 (2025).

Stocker, S. et al. Broadband optical properties of milk. Appl. Spectrosc. 71, 951–962. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003702816666289 (2017).

Aernouts, B. et al. Visible and near-infrared bulk optical properties of Raw milk. J. Dairy Sci. 98, 6727–6738. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2015-9630 (2015).

Burrow, J., Jakachira, R., Lemaster, G. & Toussaint, K. Smartphone tristimulus colorimetry for skin-tone analysis at common pulse oximetry anatomical sites. Biophotonics Discovery. 2, 032504 (2025).

Skandarajah, A., Reber, C. D., Switz, N. A. & Fletcher, D. A. Quantitative imaging with a mobile phone microscope. Plos One. 9, e96906. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096906 (2014).

Cai, F., Wang, T., Lu, W. & Zhang, X. High-resolution mobile bio-microscope with smartphone Telephoto camera lens. Optik 207, 164449 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.Y. conceived the idea and the design. Z.D, M.C, and Z.M. built and tested the hardware systems, conducted related experiments, and prepared the manuscripts and figures. S.A, J.S., M.J., A.Y. tested the codes and processed data, conducted related experiments, and prepared the manuscripts and figures. B.Y. wrote the codes and processed the data with assistance from others and prepared the manuscripts and figures. All authors wrote and reviewed the manuscripts.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

B.Y. has a potential research conflict of interest with the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA), which, however, did not support this work. A management plan has been created to preserve objectivity in research in accordance with UTA policy. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, Z., Cai, M., Ali, S. et al. A cost-effective diffuse optical tomographic system for imaging absorbing and fluorescent targets in a scattering medium. Sci Rep 15, 45615 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30037-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30037-x