Abstract

Insulin-producing β-cells are destroyed in type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), a chronic autoimmune disease that results in complete insulin insufficiency and metabolic dysfunction. According to a survival study that used p values, some hub genes are important for predicting and diagnosing illness. Scientists have inferred medicines to identify possible therapies that interact with the identified hub genes. The GSE10586 gene expression dataset from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) was used for this investigation, which included 27 samples from 15 healthy controls and 12 diabetic patients. Normalization methods such as variance stabilization normalization (VSN) were used as part of the data pretreatment. A protein‒protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed, heatmaps were created, and the Limma algorithm was used to analyze differential gene expression. Using DAVID v6.8 and KEGG pathway annotations, the functional enrichment of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was evaluated. Furthermore, a computational study revealed CERS6 to be one of the potential hub genes. Four drugs, methotrexate, eliglustat, myriocin and statin, were the focus of further studies on the basis of predictions made via ChemSpider and PubChem database analysis. To determine the optimal binding positions of these drugs with CERS6, we used molecular docking techniques. The binding affinity of methotrexate was 8.48 kcal/mol, that of myriocin was 7.85 kcal/mol, that of eliglustat was − 6.62 kcal/mol, and that of serine was − 4.90 kcal/mol against the binding pocket’s active residues. To determine how consistently each drug interacted with the CERS6 protein over time, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were run. Throughout the simulation intervals, both medications were confirmed to be stable, with minor alterations in the CERS6 protein loop region. Therefore, the investigation of structure-based drug design has potential for identifying specific therapeutic targets. Ten hub genes were identified via network analysis of differentially expressed genes. These hub genes could serve as novel targets for T1DM detection, prognosis, and targeting. CERS6 exhibited the highest degree of interaction. Methotrexate, eliglustat, myriocin and statins were identified as potential drugs for CERS6. Overall, these findings provide valuable insights that could pave the way for new experimental strategies in T1DM therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is a persistent autoimmune condition characterized by the selective destruction of insulin-producing pancreatic β-cells, leading to a total loss of insulin and disruption in glucose metabolism1. The global incidence of T1DM is increasing consistently, with an annual increase of 3–5%, and a marked impact on children and adolescents2. In low- and middle-income countries such as Pakistan, the disease burden has been intensified by the limited healthcare access and delayed diagnosis, leading to a surge in complications and disease related deaths3. Despite posing a substantial burden on public health infrastructure, the precise molecular mechanisms driving T1DM onset are not fully delineated, and current treatment modalities remain palliative rather than curative4. A variety of factors play a role in the development of T1DM including genetic susceptibility, environmental exposures, and immune system dysregulation2,5,6. While insulin therapy continues to be the primary approach for treatment, it fails to stop the progressive deterioration of β-cells. Therapeutic interventions such as Immunotherapies and experimental antigen-specific vaccines may temporarily slow down the disease progression, yet their efficacy tends to diminish over time. Furthermore, by the time clinical diagnosis is established, an extensive β-cell depletion has occurred already, limiting the scope for early intervention. This underscores the critical need for identifying robust molecular biomarkers and viable therapeutic targets for early detection and disease-modifying interventions7,8. Emerging evidence implicated dysregulated lipid metabolism, particularly the biosynthesis of ceramides, a key driver of T1DM pathogenesis. Ceramides are bioactive sphingolipids that regulate apoptosis, inflammation, and immune function. Abnormal ceramide levels have been linked to -cell apoptosis and inflammatory milieu of type 1 diabetes9. Ceramide synthases (CERS), particularly CERS2, CERS4, CERS5, and CERS6 isoforms are key enzymes that catalyze the production of distinct ceramide species thereby modulate lipid homeostasis10. Among these, CERS6 has emerged a skey isoform implicated in immune regulation and β-cell viability, suggesting its potential as a molecular target for investigation in the context of T1DM4,5,11. Conventional single-gene analysis has yielded only limited insights into the multifactorial nature of T1DM. In contrast, systems biology frameworks incorporating network-based analyses facilitate a comprehensive exploration of disease mechanisms, revealing differentially expressed genes (DEGs), PPI mapping and regulatory or drug–target network construction. These integrative approaches facilitate the identification of hub genes, _that occupy key roles within molecular networks_offering insights into the regulatory pathways that drive the disease onset and progression12,13. In this study, we employed a systems-level framework to investigate the GSE10586 microarray dataset, comprising transcriptomics dataset from 12 T1DM patients and 15 non-diabetic controls. Following rigorous data preprocessing, Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) were identified to construct a PPI network for key hub genes detection. Functional enrichment analyses revealed genes associated with lipid metabolism and immune regulatory processes, notably implicating the ceramide biosynthesis pathways. Among the hub genes CERS6 was prioritized for its high centrality and functional implication. Integrating drug-gene network mapping with molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, we assessed the interaction profiles and conformational stability of four candidate compounds including methotrexate, myriocin, eliglustat, and statins, with the CERS6 protein. This integrative system level strategy encompasses transcriptomic analysis, network biology, and molecular modeling and provides invaluable insights into the regulatory architecture underlying the T1DM pathophysiology and highlights CERS6 as a promising therapeutic target. Moreover, these findings establish a conceptual and methodological framework for future experimental dissection of CERS6 driven pathways and rational intervention strategies, targeting precision interventions for the improvement of disease outcomes and patient care in T1DM.

Materials and methods

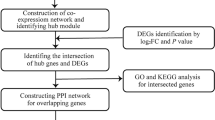

The stepwise process of a network and systems biology approach for finding therapeutic targets and pathways that are linked to them in T1DM patients is shown in Fig. 1.

Retrieval of the T1DM dataset

The Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database of NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), a freely accessible repository offering a comprehensive collection of microarrays, high-throughput hybridization data, and other resources, was utilized to retrieve the gene expression dataset for Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM)14. For this study, the dataset GSE10586 was selected, with a total of 27 samples, comprising both normal and diabetic individuals. GSM266963, GSM266964, GSM266965, GSM266966, GSM266967, GSM266968, GSM266969, GSM266970, GSM266971, GSM266972, GSM266973, GSM266974, GSM266975, GSM266976 and GSM266977 are healthy controls, whereas GSM266978, GSM266979, GSM266980, GSM266981, GSM266982, GSM266983, GSM266984, GSM266985, GSM266986, GSM266987, GSM266988 and GSM266989 are diabetic individuals. These data were based on the GPL570 [HG-U133_Plus_2] Affymetrix U133 Plus 2.0 Array. We used analytical techniques, including differential gene expression analysis, to identify significant changes in gene expression between groups, followed by principal component analysis (PCA) for the organization of the data based on shared properties. Heatmaps were generated to visualize the differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Additionally, a protein‒protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed to target the identified DEGs, with subnetwork analysis performed to highlight the hub genes9. We also developed drug-hub gene interaction networks and performed molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation analyses to validate the findings.

Data preprocessing and identification of DEGs

The Network Analyst web server tool (https://www.networkanalyst.ca/) was used to analyze the dataset to identify genes exhibiting differential expression. This analysis focused on pinpointing genes with statistically significant variations in expression10. The dataset’s structure included rows representing specific gene entries and columns corresponding to the various samples. To ensure balanced representation, the experimental data included 15 healthy samples and 12 diabetic samples. Gene‒probe IDs were uniformly converted into Entrez IDs to maintain consistency and clarity throughout the dataset. A meta-analysis of the microarray data was performed via Network Analyst, an integrated web application for meta-analysis15. The dataset was normalized via techniques such as log2 transformation, quantile normalization, and variance stabilization normalization (VSN). The normality of the processed data was confirmed by inspecting principal component analysis (PCA) plots and box plots16. Differential expression analysis was conducted for each dataset using a significance threshold of p < 0.05, and the Benjamini–Hochberg approach was applied to determine an FDR cutoff of ≤ 2. In addition, the Limma algorithm (LAT) was used to perform a t test as part of this analysis17. Furthermore, to address various sources of technical variability in the microarray data, numerous normalizing techniques were purposefully applied. In particular, the dataset’s heteroscedasticity was decreased by using variance stabilization normalization (VSN) to stabilize the variance among genes with different expression levels. To reduce data skewness and put expression values on a same scale, log2 transformation was then used, enabling more precise statistical comparisons. Lastly, quantile normalization was used to improve the comparability of gene expression measurements by ensuring that the distribution of probe intensities was consistent across all samples. Given the comparatively small sample size, this layered approach—which adheres to suggested best practices for microarray data preprocessing—was especially crucial because it reduces technical noise, improves data quality, and strengthens the robustness of subsequent differential expression and network analyses.

Analysis of the functional characteristics of the gene set

The functional characterization of the identified DEGs was carried out via an online bioinformatics tools SRplot (https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/en), DAVID v6.8 tool (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) and KEGG pathway data base (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html)18. This analysis was performed by annotating DEGs with KEGG pathway information and Gene Ontology (GO) terms, considering annotations with a significance level of p < 0.0519,20. Both differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and hub genes were included in the uploaded modules. Next, we specified several characteristics, such as species (Homo sapiens), mode functions, molecular functions, cellular components, and biological process ontologies/pathways. Data from the Gene Ontology and KEGG databases supported the functional role and pathway enrichment analysis21,22. The Benjamini–Hochberg method was utilized for enrichment analysis via a two-sided hypergeometric test. The analysis applied a kappa score of 0.95, and enrichment was calculated with a threshold value greater than 0.005.

Generation of the PPI network

To construct a protein‒protein interaction (PPI) network for type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), we utilized the STRING database (https://string-db.org/)23, which comprises 59’309’604 human proteins and 12,535 documented organisms. The interactions were imported into Cytoscape v3.10.1 for visualization and analysis, with subsequent evaluation of various essential parameters24. A combined confidence score of at least 0.45 (medium confidence) was used to ensure significance25. Direct interplay between each DEG and its first-level interactors was identified, and the network design was refined to focus solely on primary DEGs. Zero-order interactions were specifically selected to enable precise PPI visualization and for the minimization of the crowded and complex “hairball effect” often observed in dense networks26. The generated network was analyzed via Cityscape’s “Network Analyzer” tool to evaluate key topological properties such as the clustering coefficient, power-law-conforming node distribution, node degree distribution, network centralization, and density. These evaluations were performed to separate the features of the three constructed networks27.

Selection of central hub proteins from the PPI network

For the visualization and analysis of the generated PPI networks for type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), Cytoscape version 3.10.1 (https://cytoscape.org/) was employed28. The degree of nodes within the PPI network, defined by the number of edges connected to each node, was calculated to identify hub genes. Nodes with high degree values were designated hub genes29. These hub genes were then mapped to examine their PPI details in greater depth. Furthermore, CytoHubba is a well-established and robust tool within Cytoscape that we utilized for the analysis of network attributes and rank nodes on the basis of their centrality30. This tool incorporates 11 different methods for assessing network functionality, including identifying hub genes and key nodes. Using CytoHubba, we identified hub genes that could serve as potential novel therapeutic targets for managing T1DM.

Correlations between transcription factors and regulatory networks

The interplay between transcription factors (TFs) and their associated target genes was established via the eXpression2Kinases (X2K) web application, available at (https://maayanlab.cloud/X2K/). The complete set of DEGs, along with their respective gene notations, was provided as input to the server31. Fisher test p values were utilized to identify the 10 most significant transcription factors and kinases, along with their corresponding enrichment scores. This analysis was based on the TF and kinase modules, which were constructed using data from the ChEA69 database to generate the ChIP-X regulatory network. A regulatory network was then constructed, and Cytoscape was used to visualize the resulting “graphml” file32. During the network development process, it is ensured that the regulatory network has sufficient interconnected nodes. If gaps were detected in the pathway between kinases and TFs, the system automatically expanded the network to include enough intermediary proteins to facilitate TF binding and maintain network integrity.

Hub gene survival and expression profile analysis

The Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA2) platform (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/)33, an extensive and adaptable online tool, was utilized for the analysis of hub genes in type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). GEPIA2 integrates data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) projects to provide various analytical features. For differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in T1DM patients, GEPIA2 was used to evaluate both their expression patterns and their potential impact on disease-related pathways. Additionally, survival analysis of the hub genes was conducted via the single-gene analysis feature GEPIA2, which calculates the log-rank p value, hazard ratio (HR), and 95% confidence interval34. On the other hand, hub genes were selected based on their relative expression levels, applying a log2FC cutoff value of less than 1 and a q value threshold of less than 0.01. This analysis provided insights into the expression profiles and potential regulatory roles of these hub genes in T1DM.

Generation of the protein and drug interaction network

To investigate the gene‒drug interactions for type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), the top 10 hub genes were investigated. The ChemSpider (https://www.chemspider.com/), and PubChem databases (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), integrated with the Network Analyzer tool, were used to retrieve detailed information about drugs and their respective targets. This database contains many medication entries, drugs, and approved biologics (such as proteins, peptides, vaccines, and allergens). Moreover, it provides data on investigational drugs currently in the discovery phase. The data entry of each drug in these databases includes extensive details, covering topics such as chemical composition, pharmacological properties, and specific target information. This rich dataset was utilized to generate a protein and drug interaction network, providing insights into potential therapeutic options for T1DM35,36.

Molecular docking

To explore the potential binding affinity and interaction patterns of candidate compounds with the Ceramide Synthase 6 (CerS6) protein, a comprehensive molecular docking study was conducted. The 3D crystal structure of the CerS6 protein (PDB ID: 8QZ7) was retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/) and served as the receptor model for the docking analysis37. Before performing the molecular docking, we validated the docking protocol by redocking approach. Using the same parameters used for the docking of candidate compounds, the natural ligand was removed and subsequently redocked into the same binding site. The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between the crystallographic and redocked ligand poses was used to assess the docking protocol’s accuracy. To ensure accurate binding predictions, we employed the AutoDockFR tool, which supports Induced-Fit Docking (IFD) protocols38. Unlike rigid docking methods, IFD accounts for conformational changes in the receptor binding site upon ligand binding, allowing side-chain flexibility and providing a more biologically relevant model of ligand-protein interactions. AutoDockFR integrates force field-based energy evaluations (e.g., AMBER and CHARMM) and is capable of supporting covalent docking scenarios and partial receptor flexibility, enhancing the predictive accuracy of binding poses, particularly for targets with dynamic active sites like CerS6. Prior to docking, ligands were energy-minimized, and Gasteiger charges were assigned. The receptor structure was prepared by removing water molecules, adding polar hydrogens, and assigning Kollman charges. A grid box encompassing the active site of CerS6 was defined based on the co-crystal ligand of the CerS6 protein (PDB ID: 8QZ7), ensuring complete coverage of potential interaction sites. The docking simulations generated multiple binding conformations for each ligand, which were ranked according to binding affinity (ΔG) and interaction energies. Post-docking, the binding poses were visually inspected and analyzed using PyMOL and Schrödinger Maestro (academic version) to identify hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, π-π stacking, and other relevant molecular contacts that contribute to binding stability. To further assess the dynamic stability and binding persistency of the top docked complexes under physiological conditions, we subjected the most promising complexes to Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations using the AMBER20 platform39. This additional step provided insight into the temporal behavior of ligand binding and the robustness of interactions within a dynamic cellular environment.

MD simulation analysis and binding free energies calculation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted using the AMBER20 software package to evaluate the structural stability and conformational behavior of the drug–CerS6 complexes over time40. The CerS6 protein was parameterized using the FF19SB force field, which provides accurate treatment of protein dynamics by including improved backbone torsion potentials. The small drug-like ligands were assigned parameters using the General AMBER Force Field (GAFF), which is well-suited for organic molecules and compatible with biomolecular force fields41,42. To ensure charge neutrality and mimic physiological conditions, sodium (Na⁺) and chloride (Cl⁻) counterions were added to the simulation box. The system underwent a two-step energy minimization process using the steepest descent and conjugate gradient algorithms. This step was crucial for removing any unfavorable steric contacts or bad geometry prior to dynamic simulations43,44. Following minimization, the system was gradually heated to 300 K in the NVT ensemble while applying weak positional restraints on heavy atoms to prevent sudden displacements. This was followed by equilibration under constant pressure (1 atm) using the NPT ensemble to ensure the system achieved a stable density and pressure profile. The production phase of the MD simulation was carried out for 200 ns for each ligand-bound complex to allow sufficient time for the observation of stable conformational states and potential deviations. The Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method was employed to accurately treat long-range electrostatic interactions, using a cutoff distance of 10.0 Å for non-bonded interactions. To maintain bond constraints involving hydrogen atoms and permit an integration timestep of 2 fs, the SHAKE algorithm was utilized. PMEMD.cuda, the GPU-accelerated module of AMBER, was used to perform the simulations efficiently, providing significant computational speed-up45,46. Post-simulation, the CPPTRAJ module was used to analyze trajectory data. Parameters such as Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), radius of gyration (Rg), and solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) were calculated to assess the structural stability, flexibility, and compactness of the complexes throughout the simulation period. Furthermore, the MMPBSA.py module26 was employed to calculate the binding free energy of complexes formed between drugs and CerS6 based on stable frames obtained from simulation trajectories.

ADMET properties evaluations

The pharmacokinetic and toxicity-related characteristics of the top-ranked natural compounds were predicted using the pkCSM web-based platform (https://biosig.lab.uq.edu.au/pkcsm/)47. This computational tool enabled the evaluation of multiple ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) parameters, including aqueous solubility, Caco-2 cell permeability, intestinal absorption efficiency, blood–brain barrier permeability, cytochrome P450 enzyme interactions (as inhibitors or substrates), as well as potential mutagenicity (AMES test), skin sensitization, and hepatotoxicity.

Results

Data normalization and principal component analysis

Biological systems are composed primarily of genes and their products, which interact in complicated ways to generate sophisticated networks. By examining both gene and protein expression, one can further comprehend immunity, protective mechanisms, signaling networks, transport routes, and disease initiation. Quantile normalization was used after the VSN method to uniformly organize microarray expression data in situations where variance is prone to fluctuations. Figure 2 displays the mean values before and after normalization, box plots, density plots and expression data. As seen in this image, the normalization technique removes any potential noise and equalizes the means across all samples. By correctly classifying controlled and mutant samples according to gene expression levels, PCA was able to differentiate distinct groups.

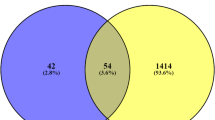

Investigation of DEGs and network analysis of PPIs

The datasets for both healthy and diabetic individuals were subjected to several statistical tests, such as Pearson’s correlation test, Benjamini‒Hochberg correction, and Student’s t test. Sixty-nine differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified because of these studies. Eighteen DEGs were upregulated, and 51 were downregulated. The modified p value and log2FC were used to rank the DEGs (Table 1) Supplementary S1. Studying the network of protein‒protein interactions (PPIs) is essential for understanding their biological functions. Analyzing how the protein network varies between healthy individuals and diabetic individuals yields important information. The nodes in this study are genes and proteins, whereas the edges are their connections. The detected DEGs were mapped, and the findings were visualized via Cytoscape to form an interaction network. A moderate confidence level of 0.70 was used to retrieve all DEG-related interactions from the STRING database. Figure 3 shows the final network based on all of the DEGs that were identified. A network consisting of 525 edges connecting 48 nodes was built. The topological metrics of the network showed significant interactions, with a mean localized cluster coefficient of 0.414 and a mean node degree of 10.7. In Fig. 4, the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) are shown as a heatmap and a volcano plot.

A The intensity distribution of each gene is depicted in the volcano plot. Based on the FDR threshold ≤ 0.05, genes shown in red are significantly elevated, genes highlighted in blue are downregulated, and genes in the samples that are not significant are indicated in gray. B The genes in each sample are shown in a heatmap, with a legend that shows the distribution of expression values, from low (green) to high (red).

Identification of target hub genes

To rank the nodes according to their level of connection, the interactions of the hub genes with the red nodes were examined. Using CytoHubba, which computes the node degrees, degree Centrality, Betweenness Centrality, Closeness Centrality and nodes with degrees greater than 10 were designated as hub nodes (Table 2). Ceramide synthase 6 (CERS6) had a degree score of 37, whereas ceramide synthase 5 (CERS5), ceramide synthase 2 (CERS2), and ceramide synthase 4 (CERS4) each had degree scores of 36. Delta (4)-desaturase, sphingolipid 1 (DEGS1) score 35. These genes also presented relatively low degree values, including N-acylsphingosine amidohydrolase 2 (ASAH2), ceramide synthase 3 (CERS3), delta (4)-desaturase, sphingolipid 2 (DEGS2), N-acylsphingosine amidohydrolase 1 (ASAH1), and alkaline ceramidase 1 (ACER1). Figure 5 displays the shortest path network of these hub gene interactions, which demonstrates robust connections based on color, degree scores, degree Centrality, Betweenness Centrality and Closeness Centrality.

Identified hub gene survival and expression analysis

Based on p value evaluations, survival analysis of the major core genes revealed the importance of each of these genes in the course and evolution of the illness. These important genes can be experimentally sequenced to help characterize diseases and find possible cures. Ten important hub genes, chosen from both upregulated and downregulated DEGs, were subjected to a survival study via the GEPIA tool to evaluate their overall effect on survival. Among the ten genes associated with decreased overall survival in the group with relatively high expression, ASAH2 and CERS6 had hazard ratios (HRs) of 1.4 and 1.3, respectively. Figure 6 displays the conclusions of the present study. Moreover, gene expressions were also evaluated via the same tool via the TNMplot web application. According to the results, only 8 hub genes were downregulated in normal cells: CERS6, CERS5, CERS2, DEGS1, ASAH2, DEGS2, ASAH1 and ACER1. However, as shown in Fig. 7, only 2 hub genes, CERS4 and CERS3, were elevated in tumor cells.

Hub genes are expressed at different levels in T1DM patients, and the relative expression levels of these genes are shown in black boxes for normal samples and green boxes for tumor samples. The y-axis displays the relative gene expression levels in terms of log2(TPM + 1) (transcripts per million, TPM) for 179 tumor samples and 171 normal samples from GEPIA, with a significance threshold of p ≤ 0.01.

Analysis of transcription factors and protein kinases

On the basis of their function in generating regulatory network activities, the most important transcription factors (TFs) and protein kinases linked to the top 10 identified target genes were determined in this investigation. The transitory proteins, kinases, and TFs that are involved in this process are joined to create a network that serves as a regulatory complex. The target genes of the transcription factors were first identified via ChIP-seq (ChEA) studies, and the main TFs were subsequently predicted from these genes. As shown in Fig. 8A and B, these TFs were then mapped onto protein‒protein interaction (PPI) networks. CHD1, GATA2, GATA1, TCF3, KLF4, HDAC2, STAT3 and FOXA1 were the primary TFs identified on the basis of the hypergeometric p value. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 8C and D, kinases that are likely to function as regulators of the enlarged PPI network were identified and added to the network. Furthermore, according to the hypergeometric p value, the main kinases linked to these top 10 identified target genes were CDK1, MAPK14, MAPK1, MAPK3, ERK1 and GSK3B. Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 list the scores for each identified TF and kinase.

A A bar chart showing the anticipated transcription factors found in the list of the top 10 identified target genes. The hypergeometric p value is used to compute the score of each bar. B The transcription factors and the interacting proteins to which they are linked are highlighted in a subnetwork diagram. Proteins that interact with transcription factors are depicted as gray nodes, whereas the transcription factors themselves are pink nodes. Each node’s size indicates how connected it is to the rest of the network. C The top predicted kinases are ranked in a bar graph, and their scores are shown via hypergeometric p values. D The functions of transcription factors and kinases in the upstream signaling cascade can be better understood by examining known protein‒protein interactions between the top 10 identified overlapping target genes.

Analysis of the KEGG pathways and GO function enrichment

GO analysis was performed via the DAVID database and SRplot tools to identify the top 10 genes from the enrichment analysis of both the upregulated and downregulated top 10 target hub genes. These GO findings encompassed categories such as biological processes, molecular activities, cellular components, and KEGG pathways. One particularly relevant criterion used in the analysis was the false discovery rate (FDR). The top 10 target hub genes associated with the cellular component (CC) category included (GO:1904724-tertiary granule lumen), (GO:0005901-caveolar), (GO:0035579-specific granule membrane), (GO:0043202-lysosomal lumen), (GO:0044853-plasma membrane raft), (GO:0101002-ficolin-1-rich granule), (GO:1904813-ficolin-1-rich granule lumen), (GO:0042581-specific granule), (GO:0070820-tertiary granule), (GO:0005775-vacuolar lumen), (GO:0030667-secretory granule membrane), (GO:0045121-membrane raft), (GO:0098857-membrane microdomain) and (GO:0098589-membrane region). The GO analysis of the CCs of the DEGs revealed a clear and noteworthy distribution pattern for the hub genes, as shown in Fig. 9B. Furthermore, 11 important molecular function (MF)-related functional categories were found in which proteins actively function. (GO:0016410-N-acyltransferase activity), (GO:0016747-transferase activity; the ability to transfer acyl groups other than aminoacyl groups), (GO:0016746-transferase activity; the ability to transfer acyl groups), (GO:0016811-hydrolase activity; the ability to act on carbon‒nitrogen (but not peptide) bonds; linear amides), (GO:0016810-hydrolase activity; the ability to act on carbon‒nitrogen but not peptide bonds), (GO:0004553-hydrolase activity; the ability to hydrolyze O‒glycosyl compounds), (GO:0016798-hydrolase activity; the ability to act on glycosyl bonds), (GO:0016705-oxidoreductase activity; the ability to act on paired donors; the incorporation or reduction of molecular oxygen), (GO:0016859-cis‒trans isomerase activity), (GO:0009055-electron transfer activity) and (GO:0016853-isomerase activity) are among these functions, as shown in Fig. 9C. In addition, the majority of the key Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways that have been identified are linked to processes connected to T1DM, which include (hsa00600-sphingolipid metabolism), (hsa04071-sphingolipid signaling pathway) and the (hsa04142-lysosome). The target hub genes presented a number of enriched biological processes (BPs), including (GO:0006672-ceramide metabolic processes), (GO:0030148-sphingolipid biosynthetic processes), (GO:0046513-ceramide biosynthetic processes), (GO:0046467-membrane lipid biosynthetic processes), (GO:0006665-sphingolipid metabolic processes), (GO:0006643-membrane lipid metabolic processes), (GO:0046519-sphingoid metabolic processes), (GO:0034311-diol metabolic processes), (GO:0019751-polyol metabolic processes) and (GO:0006066-alcohol metabolic processes), as shown in Fig. 9A. The cellular components, molecular activities, KEGG pathways, and biological events are shown in Table 3 for more in-depth details. Furthermore, Fig. 10. the Dot and Cnet plots are used to display the functional enrichment analysis of the top ten hub genes. Critical biochemical processes like N-acyltransferase activity and important cellular components like the tertiary granule lumen were also significantly impacted by these genes. The pathway analysis demonstrated their connection to the metabolism of ceramides and sphingolipids. In the dot plots, huge red dots represent statistically significant terms, emphasizing the hub genes’ biological significance within the context of the T1DM study.

The findings demonstrate the critical functions of the discovered target hub genes in.

A The Cnet map depicts the relationship of the top ten hub genes with the tertiary granule lumen, indicating their involvement in cellular components. The corresponding dot plot depicts important cellular components as large red dots (indicating low p-values), while non-significant terms are represented by blue or purple dots. B The Cnet figure shows the N-acyltransferase activity associated with the top ten hub genes, illustrating their functional linkage to molecular processes. Large red dots on the dot plot represent statistically significant molecular functions, while blue or purple dots signal less significant results. C The Cnet map depicts the participation of the top 10 hub genes in sphingolipid metabolism pathways, with large red dots representing major routes and blue/purple dots representing non-significant keywords. D Finally, the Cnet plot further emphasizes the importance of the top hub genes in the ceramide metabolism pathway. The dot plot depicts importance, with red dots indicating important routes based on p-values and blue/purple dots corresponding to pathways with lower statistical relevance.

CerS6 protein and drug interactions

After the identification of the most important hub genes, a search for possible treatment options was carried out in the ChemSpider and PubChem databases. Every target was examined in this investigation, and medications linked to these targets were found via hand searches. The search encompassed drugs from a number of categories, including FDA-approved drugs and investigational drugs. Drugs that interact with the proteins identified by each hub gene were manually identified. A total of 9 medications were found: 4 for ceramide synthase 6 (CERS6), 1 for ceramide synthase 5 (CERS5), and 2 for ceramide synthase 2 (CERS2), and each for 1 drug each for ceramide synthase 3 (CERS3) and N-acylsphingosine amidohydrolase 1 (ASAH1). The remaining targets did not have any medications. Table 4 provides a list of medications that have been identified for each target.

Molecular docking of drugs with the CerS6 protein

Therefore, to explore the bonding network of methotrexate, myriocin, eliglustat, and statin compounds with the CerS6 target protein, we carried out molecular docking, a powerful computational technique that is vital for comprehending drug‒protein interactions and assisting in drug discovery and development. To validate the docking protocol, we performed the redocking analysis. The redocking procedure produced an RMSD value of 1.12 Å, indicating a good degree of posture prediction accuracy. The redocked conformation is represented by the cyan structure in the superimposed model, while the electron microscopy (EM) structure obtained by experiment is represented by the green structure (Supplementary Fig. 1). The two are closely aligned, which suggests that the docking parameters were optimized. These findings demonstrate that the docking setup is stable and appropriate for virtual screening of new CERS6 inhibitors, even though there are currently no experimentally confirmed ligands for CERS6. This validation gives assurance that, even in the absence of benchmark reference ligands, the docking used can reliably anticipate ligand binding orientations and interactions. To perform molecular docking, we defined the active site residues of CerS6, such as Arg131, Tyr189, Asp242 and Lys328, as previously identified. The docking analysis revealed robust interactions, with docking scores of -8.48 kcal/mol, -7.85 kcal/mol, -6.62 kcal/mol and − 4.90 kcal/mol for methotrexate, myriocin, eliglustat, and statin, respectively (Table 5). The bonding network analysis of methotrexate-CerS6 revealed the formation of three hydrogen bonds between key amino acid residues, such as Thr142, Asp239 and Asp242 (Fig. 11a). Methotrexate showed strong binding affinity with the CerS6 protein by targeting the active site residue Asp242. Furthermore, analysis of the myriocin-CerS6 complex revealed the formation of four hydrogen bonds with the amino acids Arg131, Glu134, Lys249 and Tyr253 (Fig. 11b). The myriocin also targets the previously identified active site residue Arg131. Moreover, in the case of the Eliglustat-CerS6 complex, docking analysis revealed two hydrogen bonds targeting the Lys203 and Lys249 amino acid residues (Fig. 11c). Additionally, docking analysis revealed the formation of two hydrogen bonds between the Statin and CerS6 proteins, which target the key amino acid residues Asp242 and Arg275 (Fig. 11d).

Molecular dynamic simulation

The RMSD (root mean square deviation) analysis over a 200-nanosecond molecular dynamics simulation reveals distinct structural dynamics for four different molecular systems (Methotrexate-CerS6, Myriocin-CerS6, Eliglustat-CerS6, and Statine-CerS6). In the case of the methotrexate-CerS6 complex, the RMSD starts at a low value near 0 Å, indicating an initial conformation close to the reference structure. However, the RMSD increases steadily within the first 50 ns, peaking at approximately 8–9 Å, reflecting significant structural deviations from the starting configuration. Beyond 50 ns, the RMSD fluctuates around this high value, suggesting dynamic rearrangements. Toward the end of the simulation (after ~ 180 ns), the RMSD decreases, possibly indicating a structural transition to a more stable conformation. These trends suggest that the methotrexate-CerS6 complex undergoes substantial structural rearrangements before stabilizing (Fig. 12a). Similarly, the myriocin-CerS6 system shows the lowest RMSD values across the simulation, fluctuating between 3 and 6 Å. The minimal deviations indicate high stability, with the structure remaining close to its reference conformation. The small variations at different time points suggest transient, localized adjustments, but overall, the system maintains structural integrity and does not undergo significant conformational shifts. This makes the myriocin-CerS6 complex the most stable among the four systems (Fig. 12b). Furthermore, the Eliglustat-CerS6 system exhibited a relatively consistent increase in RMSD, reaching a plateau of ~ 4–6 Å after the first 50 ns. The plateau indicates that the system finds a stable conformation after early adjustments. The smaller RMSD compared with Methotrexate-CerS6 implies that the Eliglustat-CerS6 complex maintains closer similarity to the reference structure, reflecting moderate conformational changes and relative stability throughout the simulation (Fig. 12c). Finally, in the case of the Statine-CerS6 complex, the RMSD starts low but increases steadily over time, reaching approximately 10 Å at 150 ns and then remaining stable until the end of the simulation. The continuous increase suggests that ongoing conformational changes occurred during the simulation until stable confirmation was reached after 150 ns (Fig. 12d). The higher final RMSD values than those of the other systems imply that the statin-CerS6 complex is the least stable of the four complexes and is undergoing significant structural rearrangements. In summary, the RMSD analysis revealed that the stability of the drug-target complexes with the myriocin-CerS6 complex was the highest, and eliglustat-CerS6 maintained moderate stability among the studied drugs.

Dynamic stability analysis of lead compounds and target proteins. a Complex stability of the methotrexate-CerS6 complex as a function of the RMSD. b Complex stability of the myriocin-CerS6 complex as a function of the RMSD. c Complex stability of the Eliglustat-CerS6 complex as measured by the RMSD. d Complex stability of the statin-CerS6 complex as measured by the RMSD.

Furthermore, the radius of gyration (Rg) plots illustrates the compactness and conformational dynamics of the four molecular systems over a 200-nanosecond simulation. The Rg values, measured in angstroms (Å), reflect the system’s overall spatial distribution and folding behavior. In the case of the methotrexate-CerS6 complex, the Rg starts at approximately 22 Å, increases steadily during the first 40–60 ns, and then remains stable at approximately 24–25 Å before slightly decreasing toward the simulation end. This trend suggests initial unfolding or expansion of the molecular system, followed by partial compaction. The decrease in Rg near 200 ns aligns with potential structural stabilization, similar to the RMSD analysis (Fig. 13a). Similarly, in the case of the myriocin-CerS6 complex, the Rg remains highly stable at approximately 23–24 Å throughout the simulation, with minor fluctuations. This stability indicates that the molecular system maintains its compactness, with minimal structural rearrangement. In addition to its RMSD profile, this further supports the classification of the myriocin-CerS6 complex as the most stable system in terms of both compactness and conformation (Fig. 13b). Additionally, in the case of the Eliglustat-CerS6 complex, the Rg shows minimal fluctuations throughout the simulation, ranging between 23 and 25 Å. The system appears relatively compact, with gradual structural adjustments over time. The consistent Rg trend reflects stable conformational behavior, suggesting moderate changes in the overall structure of the Eliglustat-CerS6 complex (Fig. 13c). Moreover, in the case of Statine-CerS6, the Rg starts at approximately 22 Å and increases significantly, peaking at ~ 27 Å at approximately 100 ns. It then oscillates between 25 and 26 Å for the remainder of the simulation (Fig. 13d). This pattern indicates substantial expansion and structural rearrangement, reflecting lower stability and higher conformational variability than those of the other complexes. In summary, the Rg analysis complements the RMSD findings, with the myriocin-CerS6 complex showing the most stable and compact structure.

The Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) plot compares the residue wise flexibility for the Methotrexate-CerS6, Myriocin-CerS6, Eliglustat-CerS6, and Statin-CerS6 complexes across the simulation. The RMSF values (in angstroms) indicate the average positional fluctuation of each residue, revealing regions of structural rigidity and flexibility in the molecular systems. As shown in Fig. 14, the methotrexate-CerS6, myriocin-CerS6, and eliglustat-CerS6 complexes exhibited similar patterns of fluctuations, peaking around residues 75 and 125 but with minor fluctuations in different regions (Fig. 14). However, the statin-CerS6 complexes demonstrated the greatest fluctuations, with particularly significant peaks at approximately residues 75 and 125, which reached RMSF values above 14 Å, and a minor peak at approximately 200 cm-1 (Fig. 14). This finding indicates considerable mobility and structural instability in these regions, which is consistent with its higher RMSD and Rg variability. In summary, the RMSF results further validated the RMSD and Rg data, revealing the stable behavior of the drug‒protein complexes.

Figure 14 shows the hydrogen bond (H-bond) analysis of the four drug‒protein complexes over 200 ns, with the number of H-bonds tracked on the y-axis. The stability and consistency of H-bonds over time reflect the robustness of molecular interactions. In the cases of the methotrexate-CerS6, myriocin-CerS6, eliglustat-CerS6, and statin-CerS6 complexes, the number of H-bonds is relatively high, fluctuating between approximately 140 and 180, suggesting a stable yet dynamic interaction network (Fig. 15a-c). In the case of the Methotrexate-CerS6 and Eliglustat-CerS6 systems, the number of hydrogen bonds was initially high; however, a minor decrease was observed after 20 ns. In contrast, the statin-CerS6 complex results in lower H-bond counts, ranging from approximately 70–90, indicating a reduced interaction network or weaker binding affinity (Fig. 15d). The fluctuations in all the plots highlight the transient nature of hydrogen bonds in molecular systems, which form and break dynamically. The results provide insights into the relative stability and binding properties of each configuration, with myriocin-CerS6 potentially demonstrating stronger and more consistent hydrogen-bond interactions than the other configurations, which further validated the RMSD, RMSF and Rg data.

Calculation of the post simulation hydrogen bonding network. a Average number of hydrogen bonds of the methotrexate-CerS6 complex. b Average number of hydrogen bonds in the myriocin-CerS6 complex. c Average number of hydrogen bonds of the Eliglustat-CerS6 complex. d Average number of hydrogen bonds of the statin-CerS6 complex.

Binding free energies calculation

The MM/GBSA analysis presented in Table 6 provides insight into the binding free energies of four drug candidates Methotrexate, Myriocin, Eliglustat, and Statin interacting with the CerS6 protein. The binding free energy (∆G total) is a key indicator of binding affinity, where more negative values suggest stronger and more favorable interactions. Among the four drugs, Myriocin (− 50.83 kcal/mol) exhibited the most favorable binding, closely followed by Eliglustat (− 49.46 kcal/mol) and Methotrexate (− 44.39 kcal/mol), while Statin (− 20.55 kcal/mol) showed the weakest interaction. The van der Waals (ΔEvdw) and electrostatic (ΔEele) contributions were major favorable components for binding, particularly ΔEele, which was highly negative for all ligands especially Eliglustat and Methotrexate. However, these favorable gas-phase interactions were partially offset by solvation energies (Delta G Solv), indicating that desolvation penalties affect overall binding affinity. Nonetheless, the combined gas-phase and solvation contributions resulted in net negative binding energies for all complexes, confirming spontaneous binding, with Myriocin and Eliglustat emerging as the most promising inhibitors of CerS6. However, The MM/PBSA calculations give the same gas-phase (ΔE_vdw + ΔE_ele) contributions but different solvation terms (EPB instead of EGB), producing smaller-magnitude total ΔG values: Eliglustat is the best binder here (ΔG ≈ − 23.88 kcal/mol), followed by Myriocin (− 17.47 kcal/mol), Methotrexate (− 14.67 kcal/mol) and Statin (− 11.84 kcal/mol). The PB solvation (EPB) numbers are large and positive (e.g., ~+608 for Eliglustat), and the additional ENPOLAR/EDISPER terms alter the net solvation contribution relative to GB results overall the PB model imposes a larger desolvation penalty that reduces the final binding free energies. Because PB solves the Poisson–Boltzmann equation numerically, MM/PBSA is often considered more physically rigorous for polar/charged ligands and so may produce more realistic absolute solvation penalties; consequently its smaller (less negative) ΔG values likely reflect a stricter accounting of solvation effects. However, PB is more sensitive to parameter choices (dielectric constants, grid settings) and, like GB, omits conformational entropy unless explicitly added, so rankings should be cross-validated (Table 6).

Pharmacokinetics analysis

The pharmacokinetic evaluation of Methotrexate, Myriocin, Eliglustat, and Statin reveals distinct absorption, distribution, metabolism, and toxicity profiles. Methotrexate and Myriocin exhibit moderate water solubility but poor Caco-2 permeability and low intestinal absorption, suggesting limited oral bioavailability, whereas Eliglustat and Statin demonstrate higher permeability and absorption potential. Eliglustat shows the highest volume of distribution, indicating extensive tissue penetration, while all compounds display poor blood-brain barrier and CNS permeability, minimizing central effects. Among the tested drugs, only Eliglustat is metabolized by CYP3A4, implying possible drug-drug interactions, while the others show minimal CYP involvement and hence low metabolic interference. Eliglustat and Myriocin exhibit higher total clearance, suggesting faster elimination, whereas Methotrexate and Statin show slower clearance, indicating prolonged systemic presence. Toxicity predictions reveal no mutagenic, carcinogenic, or skin-sensitizing potential for any compound; however, Methotrexate and Eliglustat display hepatotoxic tendencies, unlike Myriocin and Statin. Overall, Eliglustat and Statin demonstrate superior pharmacokinetic properties in terms of absorption and safety balance, while Methotrexate and Myriocin show limited absorption and potential hepatic risk, reflecting diverse pharmacological and safety profiles among the tested compounds (Table 7).

Discussion

Diverse genomic data can be analyzed via a variety of computer methods, such as microarray gene expression profiling and single-nucleotide polymorphism analysis. These techniques offer vital information on illnesses, from diagnosis to therapy48. To evaluate mRNA and gene expression, profiling normal and malignant cell activity is essential, as is the use of Illumina systems. These techniques provide adaptable benefits for different study configurations49,50. These methods are useful for obtaining a variety of data from several phases, including metabolomics, transcriptomics and epigenetics. They are frequently employed in prediction and development to support prognostic and predictive biomarkers. Furthermore, protein–protein interaction (PPI) network analysis is frequently used to understand metabolic processes, find therapeutic targets, and explain disease mechanisms51. Targeting particular nodes in the creation of novel drugs is made possible by analyzing microarray gene expression data and finding genes that are expressed differently in diseased situations than in normal states. Molecular network connections make it easier to find disease-related biomarkers more precisely and consistently52. Previous research has demonstrated the usefulness of this type of study in forecasting hub nodes and their important involvement in a variety of diseases53,54.

Although the exact cause of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) pathological consequences is unknown, hyperglycemia is thought to be a major contributing factor55. Despite being less prevalent than type 2 diabetes is, type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) can affect the heart, kidneys, autonomic nervous system, and other regions of the body56. Identifying particular molecular biomarkers for early diagnosis and therapy is essential for improving survival outcomes because type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) has a dismal prognosis. The risk of hypoglycemia, which is still a significant obstacle to strict glycemic control with insulin alone, is the fundamental reason why insulin therapy is limited in its ability to achieve ideal glucose control. However, therapeutic approaches have changed dramatically because of recent technological developments and a better understanding of glucose metabolism, β-cell growth, and the immunological systems underlying the illness. Current approved treatments focus on improving glucose regulation to manage hyperglycemia, whereas immunotherapies attempt to address immune system abnormalities that lead to β-cell death57. To investigate the molecular causes of T1DM and find putative biomarkers, we examined the gene expression dataset GSE10586, which comprises both healthy and diabetic individuals. The application of network and systems biology approach analysis to these biological parameters is used to investigate treatment-friendly genes. Among the 69 DEGs, 18 genes were upregulated, and 51 were downregulated. The modified p value was used to prioritize the final DEGs. One essential technique for emphasizing the structure of the cell networking process is the PPI network. The relationships between the hub genes and nodes were evaluated and ranked. The interconnectedness of red nodes is extensive. Nodes with a degree value greater than 10 were designated as hub nodes by Cytohubba, which also identified some of the major transcription factors (TFs) and protein kinases linked to DEGs. Furthermore, 10 hub genes that might be used as therapeutic targets were identified via enrichment analysis, with CERS6 ranking highest. Numerous investigations on the function of CERS6 in T1DM patients have shown that disease progression is associated with its expression, which is markedly increased in highly type 1 diabetes mellitus patients. Insulin resistance, a defining feature of metabolic disorders, has been connected to an imbalance in ceramide metabolism, which is largely impacted by CERS6. While β-cell breakdown causes insulin insufficiency, which is the major characteristic of T1DM, ceramide signaling may affect the function of remaining β-cells or worsen problems in T1DM patients9,58.

Additionally, the development of T1DM depends on the various targets that have been discovered. Enrichment analysis, subnetwork building, and the inclusion of all hub genes within these subnetworks were used to highlight their importance. By examining KEGG pathways, molecular activities, cellular components, and biological processes, the roles of these genes in numerous interrelated networks were further elucidated. Determining the regulatory functions of transcription factors has also been made possible by their identification and comprehension of their roles within the enlarged network. In previous studies, the significance of sphingolipid metabolism, the sphingolipid signaling pathway and lysosomes in T1DM has also been acknowledged. These particular pathways were also included in our KEGG pathway analysis. Furthermore, our research indicates that T1DM patients have significant alterations in the sphingolipid signaling pathway59.

This study also includes medications from a number of categories, such as FDA-approved medications and investigational medications. Pharmaceuticals were carefully examined to determine whether drugs interact with each protein that was identified as a hub gene. For every protein, 9 medications were found. The next step was ChemSpider and PubChem database analysis to create therapeutic compounds as expected against the protein target. Furthermore, to investigate FDA-approved medication compounds that target the CERS6 hub gene, a sophisticated computational method has been devised. For the therapeutic target, the ligand structure was optimized during the computer-aided drug design process. Furthermore, the docked complexes were validated via molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which offered important insights into the dynamic behavior of receptor‒ligand interactions. Structural differences resulting from constrained ligand conformation and limited receptor flexibility cannot be explained by molecular docking alone. By examining the dynamic function of CERS6, the simulation method provided valuable information about the potential of this protein as a therapeutic target in T1DM.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study combined network analysis, functional enrichment, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to identify potential biomarkers and therapeutic candidates for type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). Ten hub genes were identified, with CerS6 showing the highest level of interaction, suggesting its possible role as a key molecular target. Functional enrichment analyses linked these genes to critical biological pathways involved in immune regulation and metabolic processes associated with T1DM. Molecular docking and 200 ns MD simulations revealed strong and stable interactions between CerS6 and the candidate compounds Methotrexate, Eliglustat, Myriocin, and Statins with Myriocin and Eliglustat demonstrating particularly high stability and consistent binding behavior. Minor conformational fluctuations did not significantly affect complex stability, supporting their potential as promising inhibitors. However, we recognize that the 200 ns simulation period may not fully capture all relevant molecular motions, and the absence of experimental validation limits the strength of therapeutic conclusions. Therefore, these findings should be considered preliminary yet indicative, providing a foundation for future in vitro and in vivo studies to validate CerS6 as a therapeutic target and assess the efficacy of the identified compounds in T1DM treatment.

Data availability

The data can be provided on suitable request to the corresponding author.

References

Herold, K. C. et al. The immunology of type 1 diabetes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 24(6), 435-451.

Kandemir, N. et al. Epidemiology of type 1 diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents: a 50-year, single‐center experience. J. Diabetes. 16 (5), e13562 (2024).

Azeem, S., Khan, U. & Liaquat, A. The increasing rate of diabetes in Pakistan: a silent killer. Ann. Med. Surg. 79 (2022).

Franciscus, M. et al. Recruitment and retention of participants for an international type 1 diabetes prevention trial: a coordinators’ perspective. Clin. Trails 11 (2), 150–158 (2014).

Zorena, K. et al. Environmental factors and the risk of developing type 1 diabetes—old disease and new data. Biology 11 (4), 608 (2022).

Bronner, M. B. et al. The impact of type 1 diabetes on young adults’ health-related quality of life. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 18, 1–7 (2020).

Traversi, D. et al. Risk factors for type 1 diabetes, including environmental, behavioural and gut microbial factors: a case–control study. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 17566 (2020).

Yahaya, T. & Salisu, T. Genes predisposing to type 1 diabetes mellitus and pathophysiology: a narrative review. arXiv:2101.06680 (2021).

Ayaz, H. et al. Network-base approaches to identify therapeutic biomarkers in hepatocellular carcinoma and search for drug hunting utilizing molecular dynamics simulations. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 43(13):6910-6926. (2025).

Clough, E. & Barrett, T. The gene expression omnibus database. Stat. Genom. Methods Protoc. 418: 93–110 (2016).

Subramanian, S., Khan, F. & Hirsch, I. B. New advances in type 1 diabetes. Bmj 384: e075681 (2024).

Alcazar, O. et al. Parallel multi-omics in high-risk subjects for the identification of integrated biomarker signatures of type 1 diabetes. Biomolecules 11 (3), 383 (2021).

Sun, Y., Lei, J. & Kosmas, P. Exploring biomarker relationships in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus through a bayesian network analysis approach. In: 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) (IEEE, 2024).

Clark, A. J. & Lillard, J. W. Jr A comprehensive review of bioinformatics tools for genomic biomarker discovery driving precision oncology. Genes 15 (8), 1036 (2024).

Xia, J., Benner, M. J. & Hancock, R. E. NetworkAnalyst-integrative approaches for protein–protein interaction network analysis and visual exploration. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 (W1), W167–W174 (2014).

Khan, A. et al. An integrated systems biology and network-based approaches to identify novel biomarkers in breast cancer cell lines using gene expression data. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 12, 155–168 (2020).

Davis, J. W. Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Solutions Using R and Bioconductor (Taylor & Francis, 2007).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53 (D1), D672–D677 (2025).

Arjmand, M. P. et al. New insights on the regulatory network of drought-responsive key genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetica 151 (1), 29–45 (2023).

Jiao, X. et al. DAVID-WS: a stateful web service to facilitate gene/protein list analysis. Bioinformatics 28 (13), 1805–1806 (2012).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 25 (1), 25–29 (2000).

Hulsegge, I., Kommadath, A. & Smits, M. A. Globaltest and GOEAST: two different approaches for Gene Ontology analysis. In: BMC proceedings (Springer, 2009).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. STRING v10: protein–protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (D1), D447–D452 (2015).

Chen, E. Y. et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinform. 14, 1–14 (2013).

Oany, A. R. et al. Integrative systems biology approaches to identify potential biomarkers and pathways of cervical cancer. J. Pers. Med. 11 (5), 363 (2021).

Xia, J., Gill, E. E. & Hancock, R. E. NetworkAnalyst for statistical, visual and network-based meta-analysis of gene expression data. Nat. Protoc. 10 (6), 823–844 (2015).

Ma, L. et al. An integrated analysis of MiRNA and mRNA expressions in non-small cell lung cancers. PLoS One 6 (10), e26502 (2011).

Shannon, P. et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13 (11), 2498–2504 (2003).

Ghafouri-Fard, S. et al. Identification of diagnostic biomarkers via weighted correlation network analysis in colorectal cancer using a system biology approach. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 13637 (2023).

Pan, J., Liu, B. & Dai, Z. The role of a lung vascular endothelium enriched gene TMEM100. Biomedicines 11 (3), 937 (2023).

Chen, Y. C. et al. Peripheral immune cell gene expression changes in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with first line combination chemotherapy. PLoS One 8 (2), e57053 (2013).

Brandes, U. et al. GraphML progress report structural layer proposal: structural layer proposal. In: Graph Drawing: 9th International Symposium, GD 2001 Vienna, Austria, September 23–26, Revised Papers 9 (Springer, 2001).

Tang, Z. et al. GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 (W1), W98–W102 (2017).

Schröder, M. S. et al. Survcomp: an R/bioconductor package for performance assessment and comparison of survival models. Bioinformatics 27 (22), 3206–3208 (2011).

Pence, H. E. & Williams, A. ChemSpider: an Online Chemical Information Resource (ACS, 2010).

Kim, S. et al. PubChem substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (D1), D1202–D1213 (2016).

Koliopoulos, M. G. et al. Molecular mechanism of influenza A NS1-mediated TRIM25 recognition and Inhibition. Nat. Commun. 9 (1), 1820 (2018).

Ravindranath, P. A. et al. AutoDockFR: advances in protein-ligand docking with explicitly specified binding site flexibility. PLoS Comput. Biol. 11 (12), e1004586 (2015).

Khan, A. et al. Blocking key mutated hotspot residues in the RBD of the Omicron variant (B. 1.1. 529) with medicinal compounds to disrupt the RBD-hACE2 complex using molecular screening and simulation approaches. RSC Adv. 12 (12), 7318–7327 (2022).

Shams ul Hassan, S. et al. Computational exploration of anti-cancer potential of Guaiane dimers from Xylopia Vielana by targeting B-RAF kinase using chemo-informatics, molecular docking, and MD simulation studies. Anti Cancer Agents Med. Chem. (Formerly Curr. Med. Chemistry-Anti-Cancer Agents). 22 (4), 731–746 (2022).

Case, D. A. et al. The amber biomolecular simulation programs. J. Comput. Chem. 26 (16), 1668–1688 (2005).

Wang, J. et al. Antechamber: an accessory software package for molecular mechanical calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 222 (1), p2001 (2001).

Price, D. J. & Brooks, C. L. A modified TIP3P water potential for simulation with Ewald summation. J. Chem. Phys. 121 (20), 10096–10103 (2004).

Watowich, S. J. et al. A stable, rapidly converging conjugate gradient method for energy minimization. J. Comput. Chem. 9 (6), 650–661 (1988).

Salomon-Ferrer, R. et al. Routine microsecond molecular dynamics simulations with AMBER on GPUs. 2. Explicit solvent particle mesh Ewald. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 9 (9), 3878–3888 (2013).

Khan, K. et al. Integrated bioinformatics-based subtractive genomics approach to Decipher the therapeutic drug target and its possible intervention against brucellosis. Bioengineering 9 (11), 633 (2022).

Pires, D., Blundell, T. & Ascher, D. pkCSM, Predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. 58, 4066–4072. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104 (2015).

Arora, D., Chaudhary, R. & Singh, A. System biology approach to identify potential receptor for targeting cancer and biomolecular interaction studies of Indole [2, 1-a] isoquinoline derivative as anticancerous drug candidate against it. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 11 (1), 125–134 (2019).

Wang, Y., Cai, Y. & Miao, Y. Evolving-pattern analysis of transient and long-term biomarkers for cancers: hepatocellular carcinoma as a case. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 7, 414–422 (2015).

Li, G. G. & Wang, Z. Z. Evaluation of similarity measures for gene expression data and their correspondent combined measures. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 1, 72–80 (2009).

Hu, B., Chang, X. & Liu, X. Predicting functional modules of liver cancer based on differential network analysis. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 11 (4), 636–644 (2019).

Ma, R. et al. miRNA–mRNA interaction network in non-small cell lung cancer. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 8, 209–219 (2016).

Nayarisseri, A., Yadav, M. & Wishard, R. Computational evaluation of new homologous down regulators of translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) targeted for tumor reversion. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 5 (4), 274–279 (2013).

Hameed, A. R. et al. Exploring the hub genes and potential drugs involved in Fanconi anemia using microarray datasets and bioinformatics analysis. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 43(7), 3297-3310. (2025).

Salvi, G. E. et al. Experimental gingivitis in type 1 diabetics: a controlled clinical and microbiological study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 32 (3), 310–316 (2005).

Twetman, S., Petersson, G. & Bratthall, D. Caries risk assessment as a predictor of metabolic control in young type 1 diabetics. Diabet. Med. 22 (3), 312–315 (2005).

Warshauer, J. T., Bluestone, J. A. & Anderson, M. S. New frontiers in the treatment of type 1 diabetes. Cell Metabol. 31 (1), 46–61 (2020).

Turpin, S. M. et al. Obesity-induced CerS6-dependent C16: 0 ceramide production promotes weight gain and glucose intolerance. Cell Metabol. 20 (4), 678–686 (2014).

Alqahtani, S. M. et al. System biology approach to identify the novel biomarkers in glioblastoma multiforme tumors by using computational analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1364138 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Ongoing Research Funding program-Research Chairs (ORF-RC-2025-2600), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. KM’s research work is funded by UAE University grants (UPAR grant G-4960 and UAEU-ZU joint research grant G-5310).

Funding

Ongoing Research Funding program-Research Chairs (ORF-RC-2025-2600), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: H.A., T.H., K.M. Y.W. Data analysis: H.A., T.H., A.N., M.S., S.A., D.U.O., K.M., Y.W. Software: H.A., T.H., A.N., M.S., S.A., D.U.O., K.M., Y.W. Manuscript writing: H.A., T.H., A.N., M.S., S.A., D.U.O., K.M., Y.W. Manuscript editing: H.A., T.H., A.N., M.S., S.A., D.U.O., K.M., Y.W. Supervision: Y.W. Final approval: H.A., T.H., A.N., M.S., S.A., D.U.O., K.M., Y.W.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This is computational work that does not require ethical approval.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ayaz, H., Hussain, T., Nawaz, A. et al. Exploring the hub gene CERS6 as a therapeutic target in type 1 diabetes through a bioinformatics and network analyst approach. Sci Rep 16, 428 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30045-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-30045-x